Abstract

An examination by electron microscopy of the viral assembly sites in Vero cells infected with African swine fever virus showed the presence of large clusters of mitochondria located in their proximity. These clusters surround viral factories that contain assembling particles but not factories where only precursor membranes are seen. Immunofluorescence microscopy revealed that these accumulations of mitochondria are originated by a massive migration of the organelle to the virus assembly sites. Virus infection also promoted the induction of the mitochondrial stress-responsive proteins p74 and cpn 60 together with a dramatic shift in the ultrastructural morphology of the mitochondria toward that characteristic of actively respiring organelles. The clustering of mitochondria around the viral factory was blocked in the presence of the microtubule-disassembling drug nocodazole, indicating that these filaments are implicated in the transport of the mitochondria to the virus assembly sites. The results presented are consistent with a role for the mitochondria in supplying the energy that the virus morphogenetic processes may require and make of the African swine fever virus-infected cell a paradigm to investigate the mechanisms involved in the sorting of mitochondria within the cell.

African swine fever virus (ASFV), the causative agent of a severe disease of domestic pigs, is a large enveloped DNA virus with an icosahedral morphology (6, 40). Its genome is a double-stranded DNA molecule of about 170 kbp that contains hairpin loops and terminal inverted repetitions (13, 35). ASFV is one of the most complex animal viruses, containing about 150 potential genes (43). Although ASFV had been thought to multiply exclusively in the cytoplasm of the infected cell, results from our laboratory suggest that the replication of the viral DNA is initiated in the nucleus (12). This nuclear stage is followed by a second phase of replication in the cytoplasm.

ASFV morphogenesis occurs in discrete cytoplasmic areas close to the nucleus designated viral factories (5, 26). The virions assemble from membranous structures which become polyhedral immature virions after capsid formation on their convex surface. Beneath this envelope, two distinct domains assemble consecutively: first, a thick protein layer and, then, an electron-dense nucleoid that contains the virus DNA (2). The mature particle has about 50 proteins (8), some of which are produced by posttranslational proteolytic processing of virus polyproteins pp220 and pp62 (33, 34). Extracellular virions possess an additional lipid envelope acquired by budding through the plasma membrane (5).

Conceivably, the complex morphogenetic process of ASFV may require a considerable amount of the cellular energy provided by mitochondria. We have examined by electron microscopy the cytoplasmic assembly sites in ASFV-infected Vero cells and have observed the presence of large clusters of mitochondria located in proximity to the viral factories. We show that these clusters are not the result of the biogenesis of mitochondria in the infected cell but are due to a massive migration of preexisting organelles to the periphery of the viral assembly areas. Remarkably, ASFV infection also promoted the induction of the mitochondrial stress-responsive proteins p74 and cpn 60 concurrently with a pronounced change in the ultrastructural morphology of the organelle toward that characteristic of actively respiring mitochondria.

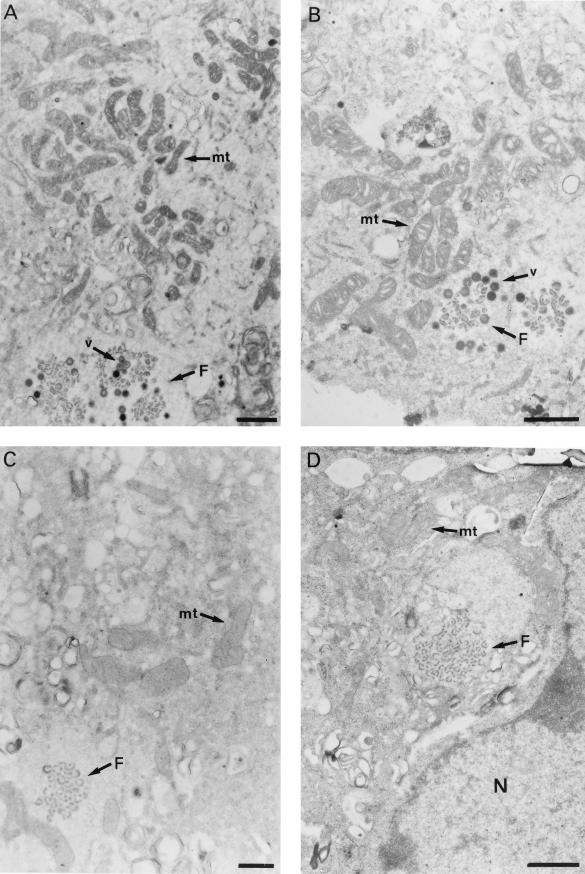

Preconfluent cultures of Vero cells were mock infected or infected with ASFV strain BA71V at a multiplicity of infection of 5 PFU per cell and, at different times postinfection, the cells were fixed, dehydrated in ethanol, and embedded in Epon. Thin-sections of these samples were then examined with an electron microscope. At 12 hours postinfection (hpi) and later, large clusters of mitochondria were seen in proximity to cytoplasmic factories containing assembling virus particles (Fig. 1A and B). By contrast, assembly sites where only virus precursor structures, such as membranes, are present, corresponding to an earlier stage in morphogenesis, were found to be surrounded by a considerably smaller number of mitochondria (Fig. 1C and D). At earlier postinfection times (8 hpi), the region surrounding the cytoplasmic DNA replication sites, identified by electron microscopic in situ hybridization using ASFV-specific DNA probes, was also found to be essentially devoid of mitochondria (29a).

FIG. 1.

Viral assembly sites in ASFV-infected Vero cells. The cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% newborn calf serum and infected with the BA71V isolate as described in the text. At 12 hpi, the cells were fixed with 2% glutaraldehyde and 2% tannic acid, dehydrated in ethanol, and stained with 2% uranyl acetate. After embedding in Epon, thin sections (80 nm) were cut, stained with 2% lead citrate, and examined under a Jeol 1010 electron microscope. (A) The micrograph shows a factory (F) that contains viral membranes and assembling particles (v). A large cluster of mitochondria (mt) is located in proximity to the factory. (B) Viral factory (F) containing membranes and assembling particles (v). The mitochondria (mt) are located very close to the virus particles. (C and D) Viral assembling sites (F) containing only precursor membranes. Few mitochondria (mt) are seen near the factories. Note also the different morphology of mitochondria in cells containing early (C and D) and late (A and B) viral assembly sites. (D) N, nucleus. (A, B, and D) Bar, 1 μm; (C) bar, 0.5 μm.

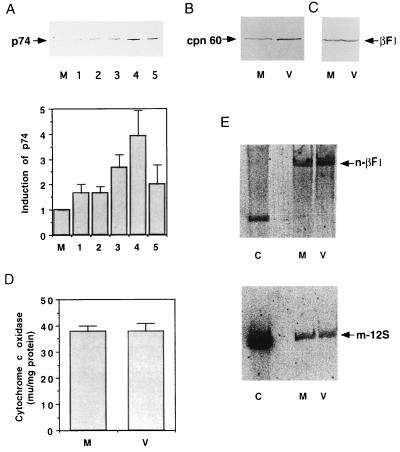

The large number of mitochondria found in the periphery of the assembly areas at the times when virus morphogenesis is under way initially suggested the induction of mitochondrial biogenesis triggered by ASFV infection. In fact, at various times postinfection quantification of the relative cellular representation of the stress-responsive p74 protein, which is located in the mitochondria of mammalian cells (1), revealed a continuous increase in its abundance as infection proceeds (Fig. 2A). At 18 hpi ASFV-infected cells showed a fourfold increase in p74 contents over that of the mock-infected cells. A similar situation, although somewhat less pronounced (a threefold increase), was noted for the relative cellular contents of the mitochondrial chaperonin cpn 60 (30) in the ASFV-infected cells (Fig. 2B). These findings were consistent with the possibility that the clusters of mitochondria in proximity to the viral factories could result from de novo accretion of mitochondrial mass.

FIG. 2.

Assay of mitochondrial proteins and DNA in ASFV-infected cells. (A) Vero cells were mock infected or infected with ASFV, and, at different times postinfection, whole-cell extracts were prepared, fractionated in sodium dodecyl sulfate–10% polyacrylamide gels, and transferred to nylon membranes. The membranes were probed as described previously (19, 37) with a 1:200 dilution of a serum which has been shown to specifically recognize the mitochondrial stress-responsive p74 (1, 9). M, mock-infected cells. The infected cells were collected at 2 (lane 1), 6 (lane 2), 12 (lane 3), 18 (lane 4), and 24 (lane 5) hpi. The histogram at the bottom of the panel illustrates the p74 induction after quantification by densitometric scanning. Each bar represents the mean of six experiments (error bar, standard error of the mean). (B and C) Same as panel A, but with antibodies against cpn 60 (StressGene) and β-F1-ATPase protein (37), respectively. Densitometric scanning of the bands shown in panel B indicated a threefold increase in the cpn 60 contents in the infected cells. Lanes M, mock-infected cells; lanes V, ASFV-infected cells at 16 hpi. (D) Cytochrome c oxidase activity in mock-infected (M) and ASFV-infected (V) cells was assayed in whole-cell extracts at 16 hpi as described previously (37). The activity is expressed in milliunits per milligram of protein. Each bar represents the mean of five experiments (error bar, standard error of the mean). (E) Vero cells were mock infected (M) or infected with ASFV (V) and, at 16 hpi, the total cell DNA was extracted, digested with BamHI, and subjected to electrophoresis in an agarose gel. After transfer to nitrocellulose membranes, the amount of nuclear DNA present in the samples was estimated by hybridization to a 32P-labeled DNA probe specific for the rat liver β-F1-ATPase gene (11). The bands corresponding to mock- and virus-infected cells were analyzed by densitometry, and the membrane was then stripped and hybridized to a probe corresponding to the gene coding for the 12S mitochondrial rRNA from rat liver (10). After densitometry was performed on the bands obtained, the amount of mitochondrial DNA in the samples was quantified by calculating the ratio of the densitometric value of the mitochondrial DNA to that of the nuclear DNA. The values for these ratios were the following: mock-infected cells, 0.37; and infected cells, 0.32. Hybridization to BamHI-digested rat liver DNA, used as a control (C) is also shown.

To further examine this, we determined the relative cellular contents of the β-catalytic subunit of the mitochondrial ATP synthase, the bottleneck of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, as well as the mitochondrial DNA contents in both mock-infected and ASFV-infected cells. Both parameters are standard reference markers for monitoring processes of mitochondrial biogenesis (20, 28) that have been shown to develop in parallel under situations of organelle biogenesis (for a recent review, see reference 7). In addition, the specific activity of complex IV of the respiratory chain was determined. The results obtained revealed no significant differences in any of the three parameters between the mock-infected and ASFV-infected cells (Fig. 2C to E), indicating that viral infection is associated not with a concurrent process of mitochondrial biogenesis but rather with the induction of a mitochondrial stress (Fig. 2A and B).

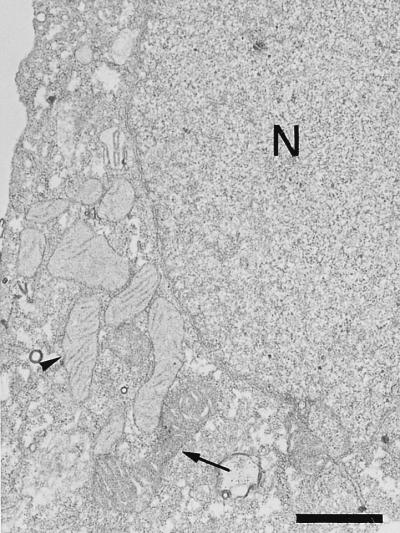

An examination by electron microscopy of the mitochondria present in mock-infected Vero cells showed that most of them presented the characteristic orthodox ultrastructure corresponding to that of the resting state of respiration (14, 15, 31, 37, 42) (Fig. 3). A statistical analysis, based on the observation of 350 mitochondria which were contained in 20 cell sections, indicated that 75% of them presented this morphology. In contrast, 95% of the mitochondria that surround factories that contain assembling virus particles in infected cells showed the condensed ultrastructure, with a marked condensation of the cristae, which is the characteristic state of actively respiring mitochondria (14, 15, 31, 37, 42) (Fig. 1A and B). It is remarkable that most of the mitochondria in cells where the viral factories contain only precursor membranes, i.e., at an earlier stage in morphogenesis (Fig. 1C and D), presented the orthodox morphology as observed in mock-infected cells. The dramatic shift in mitochondrial morphology observed in ASFV-infected cells when the assembly of virus particles is under way is compatible with an increase in the respiratory function and ATP production by their mitochondria. Presumably, an increase in mitochondrial function could lead to an increased production of reactive oxygen species (29), with subsequent damage to mitochondrial DNA and proteins. In this situation, the increase in the relative cellular contents of the stress-responsive p74 and cpn 60 mitochondrial chaperones might represent a cellular safeguard mechanism to preserve the functional integrity of the organelle from the deleterious effects of reactive oxygen species.

FIG. 3.

Mitochondrial ultrastructure in mock-infected Vero cells. Mitochondria with the orthodox ultrastructure corresponding to a resting state (arrowhead) predominate over mitochondria with the condensed morphology of actively respiring organelles (arrow). N, nucleus. Bar, 1 μm.

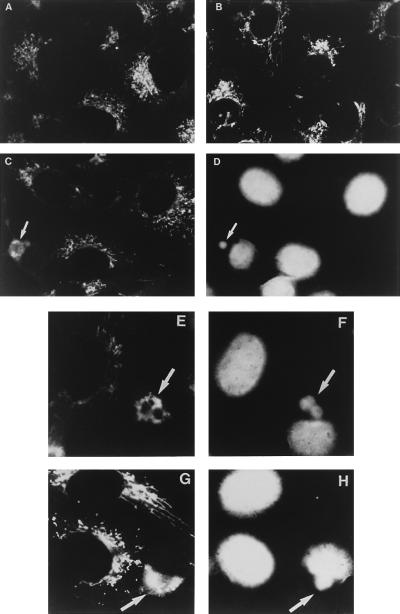

Since mitochondrial biogenesis does not occur in ASFV-infected cells, an alternative explanation for the accumulation of mitochondria near the virus assembly sites would be the transport of preexisting mitochondria to these sites. This possibility was explored by means of indirect immunofluorescence microscopy labeling the mitochondria with an antiserum against the mitochondrial F1-ATPase complex from rat liver (37). In Vero cells, this antiserum was found to recognize specifically the β-subunit of the enzyme (Fig. 2C). Mock-infected or ASFV-infected cells were fixed with methanol at different times postinfection and then incubated with the anti-F1-ATPase antibody, which was detected through secondary labeling with a fluorescein-conjugated antibody. The cells were finally stained with Hoechst in order to identify the DNA of the viral factories. Figure 4A shows the pattern of mitochondria in mock-infected Vero cells. As can be seen, the antibody revealed an intracellular distribution and morphology of the immunoreactive material resembling that previously reported for other mitochondrial proteins (1, 25) and the specific mitochondrial fluorescent marker rhodamine (2-[6-amino-3-imino 3H-xanthen-9-yl]benzoic acid methyl ester) (21) in mammalian cells. In infected cells at 8 hpi, the pattern obtained is essentially the same as that of mock-infected cells (Fig. 4B). At 14 hpi, however, a dramatic change in the mitochondrial pattern can be observed in cells that contain viral factories (Fig. 4C to F). The signal is at that time seen as a fluorescent ring that encircles the virus assembly sites, a pattern that is maintained at 16 hpi in cells with viral factories (Fig. 4G and H). No mitochondrial fluorescent signal is observed in other regions of the virus-infected cells, indicating that a massive migration of mitochondria towards the virus assembly sites has occurred.

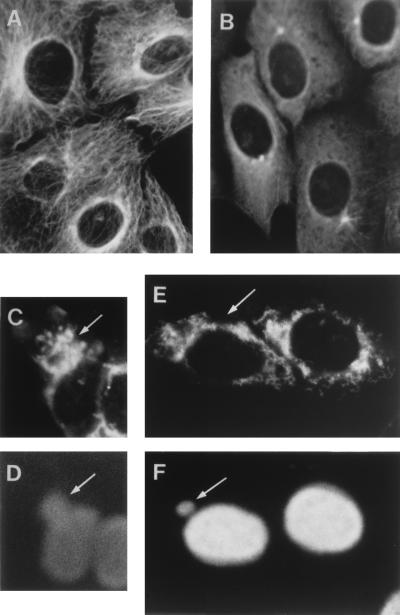

FIG. 4.

Distribution of mitochondria in mock-infected and ASFV-infected Vero cells. The cells were grown in chamber slides (Lab-Tek; Nunc), mock infected or infected as described in this work and, at different times postinfection, fixed with methanol at −20°C for 5 min. The samples were then incubated for 1 h at 37°C with a 1:10 dilution of a rabbit antiserum against the mitochondrial F1-ATPase (37). After being washed with 0.1% bovine serum albumin in phosphate-buffered saline, the cells were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with a 1:100 dilution of a donkey anti-rabbit antibody conjugated to fluorescein (Amersham). The samples were finally stained with 5 μg of bisbenzimide (Hoechst 33258; Sigma) per ml of phosphate-buffered saline for 5 min at 37°C to visualize the nuclear and viral DNA and examined with an Axiovert fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, Inc., Oberkochen, Germany). (A) Mitochondrial pattern in mock-infected cells. (B) Pattern in infected cells at 8 hpi. (C) Infected cells at 14 hpi. The arrow points to a ring-shaped mitochondrial fluorescent signal in a cell. (D) DNA staining pattern of the field shown in panel C. The arrow indicates the area of a cytoplasmic viral factory as defined by DNA staining. Notice that the fluorescent signal in panel C encircles the area of the factory. (E) Mitochondrial pattern in infected cells at 14 hpi. Two closely located mitochondrial rings are indicated by an arrow. The rings encircle the viral factories shown in panel F (arrow). (G) Infected cells at 16 hpi. The mitochondrial fluorescent signal indicated by an arrow surrounds the factory shown in panel H (H) DNA staining of the field shown in panel G. The arrow indicates the viral factory.

The microtubules have been implicated in the movement of mitochondria within the cell (4, 16, 17, 23, 24, 39). Since it was possible that these filaments act as tracks for the transport of the mitochondria to the ASFV assembly sites, we used the drug nocodazole to disassemble the tubulin network of the cell (41). Control experiments using an antitubulin antibody showed that 10 μM nocodazole effectively disassembles the microtubules of Vero cells after 1 h of incubation (Fig. 5A and B). The drug was then added or not to ASFV-infected cultures at 6 hpi, and the mitochondrial pattern was examined at 14 hpi. As described above, nontreated cells showed the characteristic mitochondrial clusters around the virus assembly sites (Fig. 5C and D). In contrast, in nocodazole-treated cells containing viral factories the mitochondrial signal remained distributed throughout the cytoplasm, with a pattern very similar to that found in infected cells that did not contain factories (Fig. 5E and F). It should be noted that the pattern of mitochondria in nocodazole-treated cells (Fig. 5E) is somewhat disorganized with respect to that of nontreated cells (compare Fig. 4), probably as a consequence of the disassembly of the microtubules. The finding that the clustering of mitochondria around the viral assembly sites is prevented in the presence of nocodazole strongly suggests that the microtubules are involved in the transport of the organelles to the proximity of the viral factories.

FIG. 5.

Effect of nocodazole on the microtubule and mitochondrial patterns in Vero cells. (A) Microtubule pattern in uninfected Vero cells. The cells were fixed with methanol at −20°C for 5 min and then incubated for 1 h at 37°C with a 1:500 dilution of a mouse antiserum against tubulin (Sigma). After being washed with 0.1% bovine serum albumin in phosphate-buffered saline the cells were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with a 1:100 dilution of a Texas Red-coupled anti-mouse antibody (Amersham). (B) Tubulin pattern in uninfected Vero cells treated with nocodazole. The cells were incubated with 10 μM nocodazole for 1 h and then processed as described for panel A. (C) Mitochondrial pattern in infected Vero cells in the absence of nocodazole. The cells were infected as indicated in the legend to Fig. 4, and, at 14 hpi, they were fixed and incubated with the antiserum against the mitochondrial F1-ATPase as described in this work. The arrow indicates the mitochondrial clustering around a viral factory. (D) DNA staining pattern of the field shown in panel C. The arrow points to the viral factory. (E) The cells were infected as described for panel C, and, at 6 hpi, 10 μM nocodazole was added to the cultures. The cells were fixed at 14 hpi and incubated with the anti-F1-ATPase serum. The arrow points to a cell containing a viral factory. (F) DNA staining pattern of the field shown in panel E. The arrow points to the factory of the cell indicated in panel E.

The migration of the cell mitochondria to the viral assembly sites that occurs in ASFV-infected cells when virus morphogenesis is under way, together with the observation that these mitochondria have the ultrastructure of actively respiring organelles, is consistent with a role for the mitochondria that surround the factories in providing the energy that might be necessary for the virus morphogenetic processes. In the ASFV assembly pathway, the virus particles are formed from precursor membranes, which accumulate in the factories (2). It is possible that the morphogenetic event that may require larger amounts of energy is the formation of the virus particle itself, as large clusters of mitochondria are not seen near factories that contain only precursor membranes.

The presence of mitochondria surrounding the cytoplasmic viroplasm has also been described in cells infected with the iridovirus frog virus 3, which has a morphology very similar to that of ASFV (22). These mitochondria, however, appear to be degenerate, and it is thus doubtful that they play a role similar to that proposed here for the mitochondria that surround the ASFV factories. On the other hand, an increase in mitochondrial activity has been observed in cells infected with adenovirus (36). Although adenovirus replicates in the nucleus of the infected cell, this finding, like ours, suggests a relevant role for mitochondrial function in certain virus infections.

An interesting question raised by these studies is the mechanism by which the mitochondria are transported to the ASFV assembly sites. The results obtained with ASFV-infected cells treated with nocodazole strongly support the argument that microtubules are the filaments used for the transport of the mitochondria to the viral factories. Certain microtubule-associated proteins, such as the ATPase kinesin (3, 18, 32, 38) and a recently described member of the kinesin superfamily, KIF1B (27), may act as motors for the movement of mitochondria. The interaction between mitochondria and microtubules may occur via these motor proteins. Activation of motor proteins by ASFV infection could cause the transport of the mitochondria along the microtubules towards the virus assembly sites. An alternative possibility to this active transport of mitochondria is suggested by unpublished data from our laboratory which indicate that, at late times postinfection, the microtubules accumulate to some extent around the virus factories (2a). The microtubule-bound mitochondria could therefore be passively transported to the periphery of the factories in this way. Whatever the mechanism involved, the ASFV-infected cell may be a suitable system in which to study mitochondrial transport within the mammalian cell.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Salas and J. Satrústegui for critical reading of the manuscript, and M. Rejas for technical assistance in electron microscopic procedures.

This work was supported by grants from the Dirección General de Investigación Científica y Técnica (PB93-0160-C02-01 and PB94-0159) and the European Community (AIR-CT93-1332) and an institutional grant from the Fundación Ramón Areces to the Centro de Biología Molecular “Severo Ochoa.”

REFERENCES

- 1.Alconada A, Flores A I, Blanco L, Cuezva J M. Antibodies against F1-ATPase α-subunit recognize mitochondrial chaperones. Evidence for an evolutionary relationship between chaperonin and ATPase protein families. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:13670–13679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrés G, Simón-Mateo C, Viñuela E. Assembly of African swine fever virus: role of polyprotein pp220. J Virol. 1997;71:2331–2341. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2331-2341.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2a.Andrés, G. Personal communication.

- 3.Brady S T. A novel brain ATPase with properties expected for the fast axonal transport motor. Nature. 1985;317:73–75. doi: 10.1038/317073a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brady S T, Lasek R J, Allen R D. Fast axonal transport in extruded axoplasm from squid giant axon. Science. 1982;218:1129–1131. doi: 10.1126/science.6183745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breese S S, Jr, DeBoer C J. Electron microscope observation of African swine fever virus in tissue culture cells. Virology. 1966;28:420–428. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(66)90054-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costa J. African swine fever virus. In: Darai G, editor. Molecular biology of iridoviruses. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic; 1990. pp. 247–270. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cuezva J M, Ostronoff L K, Ricart J, Lopez de Heredia M, Di Liegro C M, Izquierdo J M. Mitochondrial biogenesis in the liver during development and oncogenesis. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1997;29:365–377. doi: 10.1023/a:1022450831360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Esteves A, Marques M I, Costa J V. Two-dimensional analysis of African swine fever virus proteins and proteins induced in infected cells. Virology. 1986;152:192–206. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(86)90384-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flores A I, Cuezva J M. Identification of sequence similarity between 60 kDa and 70 kDa molecular chaperones: evidence for a common evolutionary background? Biochem J. 1997;322:641–647. doi: 10.1042/bj3220641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gadaleta M N, Petruzzella V, Renis M, Fracasso F, Cantatore P. Reduced transcription of mitochondrial DNA in the senescent rat. Tissue dependence and effect of L-carnitine. Eur J Biochem. 1990;187:501–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garboczi D N, Fox A H, Gerring S L, Pedersen P L. β subunit of rat liver mitochondrial ATP synthase: cDNA cloning, amino acid sequence, expression in Escherichia coli, and structural relationship to adenylate kinase. Biochemistry. 1988;27:553–560. doi: 10.1021/bi00402a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.García-Beato R, Salas M L, Viñuela E, Salas J. Role of the host cell nucleus in the replication of African swine fever virus. Virology. 1992;188:637–649. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90518-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.González A, Talavera A, Almendral J M, Viñuela E. Hairpin loop structure of African swine fever virus DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:6835–6844. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.17.6835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hackenbrock C. Ultrastructural basis for metabolically linked mechanical activity of mitochondria. I. Reversible ultrastructural changes with change in metabolic steady state in isolated liver mitochondria. J Cell Biol. 1966;30:269–297. doi: 10.1083/jcb.30.2.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hackenbrock C. Ultrastructural basis for metabolically linked mechanical activity in mitochondria. II. Electron transport-linked ultrastructural transformations in mitochondria. J Cell Biol. 1968;37:345–369. doi: 10.1083/jcb.37.2.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heggeness M H, Simon M, Singer S J. Association of mitochondria with microtubules in cultured cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:3863–3866. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.8.3863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirokawa N. Cross-linker system between neurofilaments, microtubules, and membranous organelles in frog axons revealed by the quick-freeze, deep-etching method. J Cell Biol. 1982;94:129–142. doi: 10.1083/jcb.94.1.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirokawa N, Sato-Yoshitake R, Kobayashi N, Pfister K K, Bloom G S, Brady S T. Kinesin associated with anterogradely transported membranous organelles in vivo. J Cell Biol. 1991;114:295–302. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.2.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Izquierdo J M, Luis A M, Cuezva J M. Postnatal mitochondrial differentiation in rat liver. Regulation by thyroid hormones of the β-subunit of the mitochondrial F1-ATPase complex. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:9090–9097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Izquierdo J M, Ricart J, Ostronoff L K, Egea G, Cuezva J M. Changing patterns of transcriptional and post-transcriptional control of β-F1-ATPase gene expression during mitochondrial biogenesis in liver. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:10342–10350. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.17.10342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson L V, Walsh M L, Chen L B. Localization of mitochondria in living cells with rhodamine 123. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:990–994. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.2.990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelly D C. Frog virus 3 replication: electron microscope observations on the sequence of infection in chick embryo fibroblasts. J Gen Virol. 1975;26:71–86. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-26-1-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martz D, Lasek R J, Brady S T, Allen R D. Mitochondrial motility in axons: membranous organelles may interact with the force generating system through multiple surface binding sites. Cell Motil. 1984;4:89–101. doi: 10.1002/cm.970040203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller R H, Lasek R J. Cross-bridges mediate anterograde and retrograde vesicle transport along microtubules in squid axoplasm. J Cell Biol. 1985;101:2181–2193. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.6.2181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mizzen L A, Chang C, Garrels J I, Welch W J. Identification, characterization and purification of two mammalian stress proteins present in mitochondria, grp75, a member of the hsp 70 family and hsp 58, a homolog of the bacterial GroEL protein. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:20664–20675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moura Nunes J F, Vigario J D, Terrinha A M. Ultrastructural study of African swine fever virus replication in cultures of swine bone marrow cells. Arch Virol. 1975;49:59–66. doi: 10.1007/BF02175596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nangaku M, Sato-Yoshitake R, Okada Y, Noda Y, Takemura R, Yamazaki H, Hirokawa N. KIF1B, a novel microtubule plus end-directed monomeric motor protein for transport of mitochondria. Cell. 1994;79:1209–1220. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ostronoff L K, Izquierdo J M, Enriquez J A, Montoya J, Cuezva J M. Transient activation of mitochondrial translation regulates the expression of the mitochondrial genome during mammalian mitochondrial differentiation. Biochem J. 1996;316:183–191. doi: 10.1042/bj3160183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richter C, Park J-W, Ames B N. Normal oxidative damage to mitochondrial and nuclear DNA is extensive. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:6465–6467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.17.6465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29a.Rojo, G., R. García-Beato, M. L. Salas, E. Viñuela, and J. Salas. Unpublished results.

- 30.San Martin C, Flores A I, Cuezva J M. Cpn 60 is exclusively localized into mitochondria of rat liver and embryonic Drosophila cells. J Cell Biochem. 1995;59:235–245. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240590212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scherser B, Klingenberg M. Demonstration of the relationship between the adenine nucleotide carrier and the structural changes of mitochondria as induced by adenosine 5′-diphosphate. Biochemistry. 1974;13:161–170. doi: 10.1021/bi00698a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scholey J M, Porter M E, Grissom P M, McIntosh J R. Identification of kinesin in sea urchin eggs, and evidence for its localization in the mitotic spindle. Nature. 1985;318:483–486. doi: 10.1038/318483a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simón-Mateo C, Andrés G, Almazán F, Viñuela E. Polyprotein processing in African swine fever virus: evidence for a new structural polyprotein, pp62. J Virol. 1997;71:5799–5804. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.5799-5804.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simón-Mateo C, Andrés G, Viñuela E. Polyprotein processing in African swine fever virus: a novel gene expression strategy for a DNA virus. EMBO J. 1993;12:2977–2987. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05960.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sogo J M, Almendral J M, Talavera A, Viñuela E. Terminal and internal inverted repetitions in African swine fever virus DNA. Virology. 1984;133:271–275. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(84)90394-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tollefson A E, Ryerse J S, Scaria A, Hermiston T W, Wold W S M. The E3-11.6-kDa adenovirus death protein (ADP) is required for efficient cell death: characterization of cells infected with adp mutants. Virology. 1996;220:152–162. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Valcarce C, Navarrete R M, Encabo P, Loeches E, Satrústegui J, Cuezva J M. Postnatal development of rat liver mitochondrial functions. The roles of protein synthesis and of adenine nucleotides. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:7767–7775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vale R D, Reese T S, Sheetz M S. Identification of a novel force-generating protein, kinesin, involved in microtubule-based motility. Cell. 1985;42:39–50. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80099-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Van Blerkom J. Microtubule mediation of cytoplasmic and nuclear maturation during the early stages of resumed meiosis in cultured mouse oocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:5031–5035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.11.5031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Viñuela E. African swine fever virus. In: Becker Y, editor. African swine fever. Boston, Mass: Martinus Nijhoff Publishing; 1987. pp. 31–49. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wadsworth P, McGrail M. Interphase microtubule dynamics are cell type-specific. J Cell Sci. 1990;95:23–32. doi: 10.1242/jcs.95.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weber N E, Blair P V. Ultrastructural studies of beef mitochondria. II. Adenine nucleotide induced modifications of mitochondrial morphology. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1970;41:821–829. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(70)90156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yáñez R J, Rodríguez J M, Nogal M L, Yuste L, Enríquez C, Rodríguez J F, Viñuela E. Analysis of the complete sequence of African swine fever virus. Virology. 1995;208:249–278. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]