Abstract

Consumption of ergot alkaloids from endophyte-infected tall fescue results in losses to the livestock industry in many countries and a means to mitigate these losses is needed. The objective of this study was to evaluate intra-abomasal infusion of the dopamine precursor, levodopa (L-DOPA), on dopamine metabolism, feed intake, and serum metabolites of steers exposed to ergot alkaloids. Twelve Holstein steers (344.9 ± 9.48 kg) fitted with ruminal cannula were housed with a cycle of heat challenge during the daytime (32 °C) and thermoneutral at night (25 °C). The steers received a basal diet of alfalfa cubes containing equal amounts of tall fescue seed composed of a mixture of endophyte-free (E−) or endophyte-infected tall fescue seeds (E+) equivalent to 15 µg ergovaline/kg body weight (BW) for 9 d followed by intra-abomasal infusion of water (L-DOPA−) or levodopa (L-DOPA+; 2 mg/kg BW) for an additional 9 d. Afterward, the steers were pair-fed for 5 d to conduct a glucose tolerance test. The E+ treatment decreased (P = 0.005) prolactin by approximately 50%. However, prolactin increased (P = 0.050) with L-DOPA+. Steers receiving E+ decreased (P < 0.001) dry matter intake (DMI); however, when supplemented with L-DOPA+ the decrease in DMI was less severe (L-DOPA × E, P = 0.003). Also, L-DOPA+ infusion increased eating duration (L-DOPA × E, P = 0.012) when steers were receiving E+. The number of meals, meal duration, and intake rate were not affected (P > 0.05) by E+ or L-DOPA+. The L-DOPA+ infusion increased (P < 0.05) free L-DOPA, free dopamine, total L-DOPA, and total dopamine. Conversely, free epinephrine and free norepinephrine decreased (P < 0.05) with L-DOPA+. Total epinephrine and total norepinephrine were not affected (P > 0.05) by L-DOPA+. Ergot alkaloids did not affect (P > 0.05) circulating free or total L-DOPA, dopamine, or epinephrine. However, free and total norepinephrine decreased (P = 0.046) with E+. Glucose clearance rates at 15 to 30 min after glucose infusion increased with L-DOPA+ (P < 0.001), but not with E+ (P = 0.280). Administration of L-DOPA as an agonist therapy to treat fescue toxicosis provided a moderate increase in DMI and eating time and increased plasma glucose clearance for cattle dosed with E+ seed.

Keywords: agonist therapy, bovine, ergovaline, levodopa

This research investigated for the first time the use of Levodopa in an agonist therapy to treat fescue toxicosis.

Introduction

Consumption of tall fescue pastures that are infected with an endophyte (Epichlöe coenophialia) producing toxic ergot alkaloids can result in significant annual economic losses to the livestock industry. Ergot alkaloid consumption can have several negative effects in cattle including decreased blood flow to peripheral parts of the body, increased sensibility to heat stress, dry gangrene in the extremities during cold weather, reduced conception rates, reduced dry matter intake (DMI), and reduced growth rates (Strickland et al., 2011; Liebe and White, 2018; Rahimabadi et al., 2022). Although several ergot derivates can cause physiological changes, ergovaline is the most prevalent and most toxic ergot alkaloid in fungal endophyte-infected grasses (Caradus et al., 2022).

It is well established that ergot alkaloids can compete for receptor-binding sites of the monoamine neurotransmitters such as the D2 dopamine receptors (Aldrich et al., 1993; Larson et al., 1995, 1999; Aslanoglou et al., 2021). The alkaloids have a low dissociation rate from receptor-binding sites (Sibley and Creese, 1983; Larson et al., 1999) causing a prolonged excitation of neurons which decreases receptor density, inhibits cyclic adenosine monophosphate release (Larson et al., 1994, 1999), and reduces dopamine synthesis (Filipov et al., 1999). Activation of D2 dopamine receptors by ergot alkaloids decreases circulating prolactin and decreases feed intake with effects alleviated by dopamine antagonist administration (Aldrich et al., 1993). However, the administration of a receptor antagonist is not a practical treatment for fescue toxicosis because it would block normal physiological functions mediated by dopamine receptors including motor control, motivation, reward, cognitive function, maternal, and reproductive behaviors (Klein et al., 2019).

Agonist therapy is the use of a stimulant-like compound to treat stimulant addictions and has proven an effective treatment option for nicotine and opioid dependence (Jordan et al., 2019). This strategy involves the administration of medications that share the neurobiological mechanisms of the undesirable drug (Rothman and Baumann, 2006). Therefore, we hypothesize that the administration of L-DOPA as an agonist increases serum dopamine and will aid in the mitigation of fescue toxicosis. Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate intra-abomasal infusion of the dopamine precursor, levodopa (L-DOPA), on dopamine metabolism, feed intake, and serum metabolites of steers exposed to ergot alkaloids.

Material and Methods

The experiment was performed under approval by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Kentucky (Protocol 2023-4296).

Animals and experimental design

Twelve Holstein steers (body weight [BW] = 345 ± 9.48 kg) fitted with ruminal cannulas were used in a completely randomized design experiment. The experiment was carried out for a total of 30 days. After initial acclimation (7 d), the steers were fed ad libitum and were dosed with tall fescue seed through the ruminal cannula for the 23-d experimental period (Figure 1). Beginning on day 10 the steers received an intra-abomasal infusion of L-DOPA using an infusion line inserted through the reticulo-omasal orifice for an additional 9 d. Afterward, the steers were pair-fed for 5 d and subjected to glucose tolerance tests (GTTs) in the presence or absence of L-DOPA.

Figure 1.

Time events during the experiment.

All steers were housed indoors in individual pens (3 m × 3 m). To simulate a heat challenge, the room temperature was cycled from 32 °C during the day (0600 to 2000 hours) to 25 °C during the night (2000 to 0600 hours) with a light:dark cycle of 14:10 h (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Daily cycle of air temperature. Black line is the average temperature and gray bars are standard errors.

Treatments and diet

The treatments were arranged as a 2 × 2 factorial with the factors being the combination of ergot alkaloids via seed and L-DOPA administration. The steers were fed a basal diet of alfalfa cubes and 50 g of mineral premix (Table 1), once per day, at 0830 hours allowing 5% orts. The steers received equal amounts of tall fescue seed composed of a mixture of ground endophyte-free (E−) or endophyte-infected seed (E+) dosed directly into the rumen throughout the experiment. The seed dose provided 15 µg ergovaline/kg BW (Table 2). The ergovaline dose was chosen according to Ahn et al. (2020) as a feed intake suppressor. Tall fescue seed (0.612 ± 0.018 kg) was dosed into the rumen at 0730 hours via rumen cannula.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of the diet fed to steers dosed abomasally with L-DOPA

| Item1 | Alfalfa cubes | Mineral supplement |

|---|---|---|

| Crude protein | 159 | — |

| aNDF | 418 | — |

| NFC | 231 | — |

| TDN | 570 | — |

| Calcium | 23.1 | — |

| Potassium | 20.2 | — |

| Phosphorus | 3 | — |

| Sodium | 1.3 | 470 |

| Magnesium | 3.8 | 4.8 |

| Iron | — | 9.3 |

| Zinc | — | 5.5 |

| Copper | — | 1.8 |

| Iodine | — | 0.11 |

| Cobalt | — | 0.065 |

| Selenium | — | 0.018 |

1g/kg dry matter; aNDF, neutral detergent fiber corrected for ash; NFC, nonfibrous carbohydrate; TDN, total digestible nutrients.

Table 2.

Ergot alkaloid concentrations in tall fescue seed

| Concentration, ppm | Tall fescue seeds | |

|---|---|---|

| E−1 | E+2 | |

| Ergovaline | ND | 4.69 |

| Ergovalinine | ND | 3.51 |

| Total | ND | 8.20 |

| Ergotamine | ND | ND |

| Ergotaminine | ND | ND |

| Total | ND | ND |

1Bull Lot: L67-19-1;.

2Falcon IV Lot: GBS-LH-FALH.

On day 9, in addition to the E− and E+ treatments, the steers received an intra-abomasal infusion of water (L-DOPA−) or levodopa (L-DOPA+; 2 mg/kg BW). Pure L-DOPA (Nutrivita, Lake Forest, CA, USA) from a plant extract (Mucuna pruriens) was pulse-dosed immediately after seed administration into the abomasum. The dose and method of infusion of the L-DOPA were chosen based on our previous study evaluating L-DOPA dose response (Valente et al., 2023). The intra-abomasal infusion was carried out to avoid the potential microbial metabolism of L-DOPA.

The dosage of seed and L-DOPA was adjusted based on individual BWs measured in the morning before feeding, one day before beginning seed administration (day −1), and again one day before beginning the L-DOPA infusion (day 9). The L-DOPA was mixed in 40 mL of ultrapure water immediately before the infusion and abomasally administered using a syringe for 1 to 2 min, followed by purging the infusion line with 30 mL of ultrapure water. Abomasal infusions were accomplished by placing an infusion line constructed of flexible 6.3 mm o.d. tubing and a plastisol washer (60 mm o.d.) through the reticulo-omasal orifice into the abomasum. The omasal pillar was used as a landmark and the washer was manipulated until it was distal to the pillar. The infusion line was inserted into the abomasum at the beginning of the acclimation period and left until the end of the experiment.

Feed and water Intake

The feed intake was recorded and feed samples were taken daily. The feed and orts samples were dried (55 °C for 72 h), ground at 1 mm, and analyzed for dry matter (index 920.39; AOAC, 1990).

The DMI and feeding behavior from days 3 to 7 and days 12 to 16 were used as treatment responses because the steers had been acclimated to the treatments and they were not disturbed by additional sampling. The feed intake distribution throughout the day was monitored every minute by an electronic scale with a data logger attached to each animal’s feed bunk (Campbell Scientific, Logan, UT, USA). Feeding behaviors including frequency of meals (meals/d), average meal size, and duration were calculated for each animal on each day as described previously (Egert-McLean et al., 2019). Additionally, the eating duration was the total time (min) the steers spent eating. Water intake was recorded using an analog water flow meter (DLJ Multi-Jet Water Meter, Daniel L. Jerman Co., Hackensack, NJ, USA) daily before feeding (0630 hours).

Blood sampling

Temporary i.v. catheters (14 Ga × 13 cm, Mila International, Inc., Florence, KY, USA) were inserted into the jugular vein one day before blood sampling. Before blood sample collection, 10 mL of blood and lock solution were aspirated from the catheter and discarded. Blood (approximately 20 mL) was collected from the catheter of each steer on days 9 and 18 at 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, and 12 h relative to treatment administration. After blood collection, a lock solution of heparin (20 U/mL of saline) was infused (5 mL) into the catheter to flush blood and maintain patency. An aliquot of 12 mL whole blood was transferred to a 15-mL tube with 20 µL of HCl (6 M), 400 µL EDTA disodium salt (0.1 M), and 80 µL Na2S205 (0.5 M) for plasma catecholamines analysis. An aliquot (4 mL) of blood was transferred to a tube with a clot activator for serum prolactin analysis. An aliquot (4 mL) was transferred to a tube with sodium fluoride for plasma glucose analysis. Blood samples in the tubes containing the clot activator were kept at room temperature in the dark for 45 to 60 min for clotting before centrifugation. Blood samples for plasma were immediately centrifuged. Both samples for plasma and serum were centrifugated at 3,600 × g for 15 min at 10 °C. Plasma for catecholamine analysis was deproteinized immediately after blood centrifugation using HClO4 (4 M) added at the plasma:HClO4 ratio of 5:1 and centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 30 min at 10 °C. One milliliter of whole blood containing disodium EDTA was deproteinized by adding 0.2 mL of HClO4 (4 M) and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 min for serotonin metabolite analysis. All samples were kept at −80 °C until analysis.

Glucose tolerance test

From day 19 to 23, the steers were pair-fed by adjusting to the lowest feed intake relative to BW (26 g/kg BW) to eliminate the confounding effects of dissimilar nutrient intake on glucose metabolism. GTTs were performed on day 21 for the treatments L-DOPA+ and on day 23 for the treatments L-DOPA−. The administration of L-DOPA was terminated on day 21.

The day before the GTT (day 20), sterile indwelling catheters were inserted into jugular veins as previously described. The steers did not receive feed until the blood sampling was finished. Glucose was infused (50% dextrose solution wt/vol) at a rate of 0.45 g/kg of BW0.75 over a course of 1 to 2 min (Spears et al., 2012) at 0800 hours. Before glucose infusion and blood sample collection, 10 mL of blood and lock solution were aspirated from the catheter and discarded. Following glucose infusion, the catheter was immediately flushed with 20 mL of saline. Blood samples were collected at −10, 0, 5, 10, 15, 30, 60, 90, 120, and 180 min relative to glucose dosing. After blood collection, 5 mL of lock solution with heparin (20 U/mL of saline) was infused. An aliquot of blood (4 mL) was placed in an evacuated tube containing sodium fluoride for plasma glucose analysis. Blood was kept on ice (about 30 min) until centrifuged at 3,600 × g for 10 min at 10 °C. Plasma was stored at −20 °C until analyzed.

Glucose clearance rates (k, % per min) were calculated according to the following equation (González-Grajales et al., 2018):

where G1 and G2 represent the glucose concentration at the initial and final time of an evaluated interval after glucose administration, respectively; t1 and t2 are the initial and final time evaluated.

Clearance rate values were calculated for the intervals of 5 to 15, 15 to 30, and 30 to 60 min. The area under curve (AUC) was calculated using GraphPad Prism 9.4 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) with the linear trapezoidal method at an interval of 0 to 180 min.

Physiological responses

Respiration rates (RRs) and rectal temperature were monitored on day 19 every 2 h from 0600 to 1800 hours. RRs were recorded by visual observation and reported as average breaths per minute from three 30-s evaluations in sequence. Rectal temperatures were recorded using a stainless-steel thermistor probe attached to a digital recorder (Electro-Therm TM99A; Cooper Instrument Corp., Middlefield, CT, USA).

Biochemical analysis

Plasma dopamine, L-DOPA, norepinephrine, and epinephrine were extracted as described previously (Boomsma et al., 1992) with modifications. For free dopamine, 2 mL of plasma was deproteinized with 0.4 mL of 4 M HClO4 and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was transferred to a 2-mL tube and combined with 2 mg of acid-activated alumina, 1 mL of 2 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.6), and 5 ng of dihydroxybenzylamine as an internal standard. To complete the extraction of the catecholamines, the alumina-treated samples were vigorously agitated in a vortex for 15 min followed by a 1-min centrifugation (5,000 × g), and the supernatant was discarded. Afterward, the alumina was washed 2 times with 1 mL of ultrapure water, shaken for 15 s, centrifuged for 1 min, and the supernatant was discarded. Catecholamines were subsequently eluted from the alumina by sonicating for 10 min with 50 μL of 0.5 M formic acid. For total dopamine, deproteinized samples were heated at 100 °C for 45 min and then cooled in an ice bath. Afterward, the samples were centrifuged, and the extraction of dopamine was carried out as described above for free catecholamines.

Extracted dopamine, L-DOPA, norepinephrine, and epinephrine were quantified using a Waters Acquity H-Plus ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) system equipped with a Waters Xevo TQ-S Cronos triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). Hydrophilic interaction chromatography was utilized for separation using a Waters Acquity UPLC BEH amide column (2.1mm × 150mm × 1.7 um) operated at 45 °C with a 10 µL injection volume (Waters, Ireland). The mobile phase consisted of a mixture of 0.1% formic acid in water (A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (B) with a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min. Initial conditions of 15% A and 85% B were held from 0 to 0.6 min, followed by a linear gradient to 35% A and 65% B over 8 min, with a return to initial conditions and held until 12 min. Dopamine-d4 was used as an internal standard. The mass spectrometer was operated in positive electrospray ionization mode (ESI+) with detection and quantitation of the ions performed by multiple reaction monitoring of the ion transitions 154 to 137 m/z for dopamine, 198 to 152 m/z for L-DOPA, 152 to 107 m/z for norepinephrine, 184 to 166 m/z for epinephrine, and 158 to 141 m/z for dopamine-d4 internal standard. Ergot alkaloid content in tall fescue seeds was analyzed using UPLC-tandem mass spectrometry as described by Foote et al. (2014).

Using the procedures of Bernard et al. (1993), serum prolactin analysis was conducted by the laboratory of J. L. Edwards (University of Tennessee, Knoxville) utilizing radioimmunoassay (sensitivity = 0.12 ng/mL) with average intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variation of 4.14% and 8.36%, respectively.

Whole blood tyrosine, tryptophan, 5-hydroxytryptophan, and serotonin were analyzed using the modified method by Sa et al. (2012). Briefly, blood with heparin was deproteinized by mixing with an equal volume of HClO4 (4 M) followed by vortexing and centrifuging at 20,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was diluted fourfold with ultrapure water and centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. Ultimately, 10 μL of the supernatant was injected for analysis. An HPLC (model 2695; Waters, Milford, MA, USA) with a fluorescence detector (model 2475; Waters) was used. The fluorescence detector was set with an excitation wavelength of 278 nm and an emission wavelength of 338 nm. The chromatographic separation was carried out using an ACE C18-PFP column (4.6 × 150 mm, 3 μm; Advanced Chromatography Technologies, Aberdeen, Scotland) at 40 °C. The mobile phase consisted of 0.05 M KH2PO4 and methanol (85:15, v/v; pH 4.3), at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/ min.

Glucose and nonesterified fatty acids (NEFA) concentrations were analyzed using an automatic analyzer (Konelab 20XTI; Thermo Electron Corporation) using commercial kits. Glucose was analyzed using the Glucose Hexokinase Infinity Reagent (Infinity TM, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and NEFA was analyzed using the Wako HR series NEFA-HR kit (Fujifilm, Lexington, MA).

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed as completely randomized designs using the MIXED model of SAS OnDemand for Academics (SAS Inst. Inc. Cary, NC). Variables were analyzed as repeated measurements over time. The model included the fixed effects of ergot alkaloids, L-DOPA, the hour or day of sampling/measuring and their interactions, and the random effect of steers. Various covariance structures of errors were fitted; the best structure for each variable was selected based on the lowest Bayesian information criterion. The following model was used:

where Yijkl is the dependent variables, µ is the overall mean, Ei is the fixed effect of the ergot alkaloids, DOPAj is the fixed effect of the L-DOPA, E*DOPAij is the interaction between E and DOPA, Tk is the effect of sampling time, E*Timeik is the interaction between E and sampling time, DOPA*Timejk is the interaction between DOPA and sampling time, E*DOPA*Timeijk is the interaction between E, DOPA, and sampling time, Si is the random effect of steer, and eijkl is the random error.

DMI during acclimation was used as a covariate for the evaluation of the effect of treatment on DMI. Shapiro and Wilk's (1965) test for normality was performed using the procedure Univariate of SAS. Data were transformed according to Box and Cox (1964) when there was a lack of normality as follows:

The lambda for each variable was calculated using SAS Transreg with model boxcox ranging from -2 to 2. After statistical analysis, the data were back-transformed to concentration for presentation. The SE of the back-transformed data was calculated from the confidence limits (CLs) of the transformed data as follows:

where the upper CL is back-transformed upper confidence limit and lower CL is back-transformed lower confidence limit.

Glucose clearance and AUC were analyzed without time effect. Pairwise comparisons were conducted using the LSD test. Statistical significance was considered at P ≤ 0.05 and tendency was considered at 0.05 < P ≤ 0.10.

Results

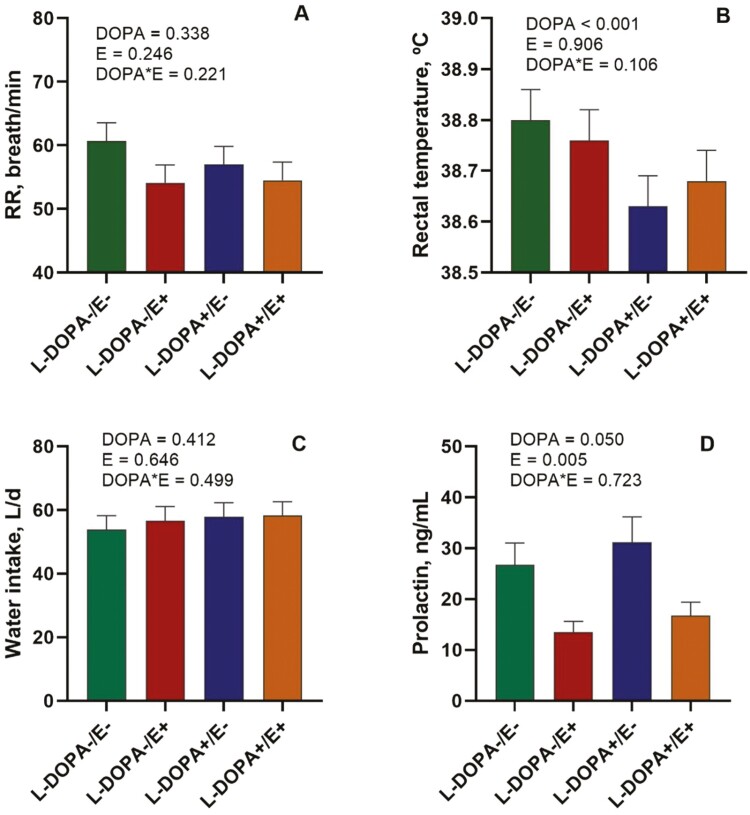

The RR was not affected (P > 0.05) during the heat challenge (daytime) by E or L-DOPA treatments (Figure 3A). Rectal temperature was lower (P < 0.001) in steers receiving L-DOPA+ (Figure 3B). However, E+ did not affect (P = 0.906) rectal temperature. Water intake was similar between all treatments (Figure 3C). The E+ treatment decreased (P = 0.005) prolactin by approximately 50% (Figure 3D). However, prolactin increased (P = 0.050) with L-DOPA+.

Figure 3.

RR (A) and rectal temperature (B), water intake (C), and serum prolactin (D) of steers receiving tall fescue seeds without (E−) or with (E+) ergot alkaloids without (L-DOPA−) and with (L-DOPA+) intra-abomasal infusion of L-DOPA. DOPA is the effect of L-DOPA infusion, E is the effect of ergot alkaloids, and DOPA*E is the interaction between L-DOPA and ergot alkaloids. Each value is expressed as the mean ± SE (n = 6).

There was an interaction (P = 0.003) between E and L-DOPA on DMI (Table 3). Steers receiving E+ decreased DMI; however, when supplemented with L-DOPA+ the decrease in DMI was less severe. There was also an interaction (P = 0.012) between E and L-DOPA on eating duration. Eating duration decreased with E+ without L-DOPA but increased with L-DOPA. The number of meals, meal duration, and intake rate were not affected (P > 0.05) by E or L-DOPA treatment. Meal size tended to decrease (P = 0.079) with E+ and was not affected by L-DOPA (P = 0.576).

Table 3.

Feed intake and feeding behavior in steers receiving tall fescue seed without (E−) or with (E+) ergot alkaloids without (L-DOPA−) and with (L-DOPA+) intra-abomasal infusion of L-DOPA

| L-DOPA− | L-DOPA+ | SEM1 | P-value2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E− | E+ | E− | E+ | DOPA | E | DOPA × E | ||

| DMI, g/kg BW3 | 31.5 | 27.1 | 31.3 | 28.3 | 0.75 | 0.085 | <0.001 | 0.003 |

| Eating duration, min | 336 | 307 | 328 | 345 | 16.3 | 0.723 | 0.380 | 0.012 |

| Meals number | 8.4 | 8.8 | 8.7 | 9.1 | 0.46 | 0.490 | 0.380 | 0.810 |

| Meal duration, min/meal | 41.1 | 36.0 | 39.2 | 38.6 | 3.20 | 0.924 | 0.426 | 0.113 |

| Meal size, kg/meal | 1.42 | 1.17 | 1.44 | 1.21 | 0.09 | 0.576 | 0.079 | 0.564 |

| Intake rate, g/min | 35.0 | 33.6 | 37.6 | 32.5 | 1.95 | 0.671 | 0.179 | 0.060 |

1SE of the mean, n = 6.

2DOPA is the effect of L-DOPA infusion; E is the effect of ergot alkaloids and DOPA*E is the interaction between L-DOPA and ergot alkaloids.

3DMI is dry matter intake.

No interaction (P > 0.05) was observed between E and L-DOPA for metabolites related to catecholamines and serotonin metabolism. The L-DOPA+ infusion increased (P < 0.05) free L-DOPA, free dopamine, total L-DOPA, and total dopamine (Figures 4 and 5). Conversely, free epinephrine and free norepinephrine decreased (P < 0.05) with L-DOPA+ treatment. Total epinephrine and total norepinephrine were not affected (P > 0.05) by L-DOPA+. Ergot alkaloids did not affect (P > 0.05) circulating free or total L-DOPA, dopamine, or epinephrine. However, free and total norepinephrine decreased (P < 0.05) with E+.

Figure 4.

Changes in plasma free L-DOPA over time (A), free dopamine (B), free norepinephrine (C), and free epinephrine (D) in steers receiving tall fescue seeds without (E−) or with (E+) ergot alkaloids without (L-DOPA−) and with (L-DOPA+) intra-abomasal infusion of L-DOPA. Each value is expressed as the mean ± SE (n = 6).

Figure 5.

Changes in plasma total L-DOPA over time (A), total dopamine (B), total norepinephrine (C), and total epinephrine (D) in steers receiving tall fescue seeds without (E−) or with (E+) ergot alkaloids without (L-DOPA−) and with (L-DOPA+) intra-abomasal infusion of L-DOPA. Each value is expressed as the mean ± SE (n = 6).

Free L-DOPA, dopamine, and epinephrine had a peak at 1 h after L-DOPA dosing with a steady concentration after 2 h (Figure 4A, B, and D). The free norepinephrine did not have a clear peak (Figure 4C). Both total L-DOPA and dopamine had a peak at 1 h after L-DOPA infusion (Figure 5A and B). However, the post-peak reductions were slower for the total than free fraction of L-DOPA and dopamine. The free and total norepinephrine and epinephrine did not show a clear peak in any treatment (Figures 4C, 4D, 5C, and 5D).

Whole blood tryptophan and 5-hydroxytryptophan increased (P > 0.05; Table 4), and serotonin tended to increase (P = 0.088) with infusion of L-DOPA. Conversely, tyrosine decreased (P = 0.002) with L-DOPA treatment. The E+ did not change (P > 0.05) whole blood tyrosine, tryptophan, 5-hydroxytryptophan, or serotonin.

Table 4.

Whole blood metabolites in steers receiving tall fescue seeds without (E−) or with (E+) ergot alkaloids without (L-DOPA−) and with (L-DOPA+) intra-abomasal infusion of L-DOPA

| Item1 | L-DOPA− | L-DOPA+ | SEM1 | P-value2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E− | E+ | E− | E+ | DOPA | E | DOPA × E | ||

| Tyrosine, µg/mL | 15.8 | 15.2 | 14.8 | 14.4 | 0.6 | 0.020 | 0.387 | 0.757 |

| Tryptophan, µg/mL | 5.8 | 5.6 | 6.2 | 6.3 | 0.2 | <0.001 | 0.844 | 0.517 |

| 5-HTP, ng/mL3 | 16.1 | 15.4 | 19.6 | 20.4 | 0.9 | <0.001 | 0.980 | 0.075 |

| Serotonin, ng/mL | 57.4 | 58.7 | 61.6 | 61.2 | 5.0 | 0.088 | 0.950 | 0.670 |

1SE of the mean, n = 6.

2DOPA is the effect of L-DOPA infusion, E is the effect of ergot alkaloids, and DOPA*E is the interaction between L-DOPA and ergot alkaloids.

35-HTP is 5-hydroxytryptophan.

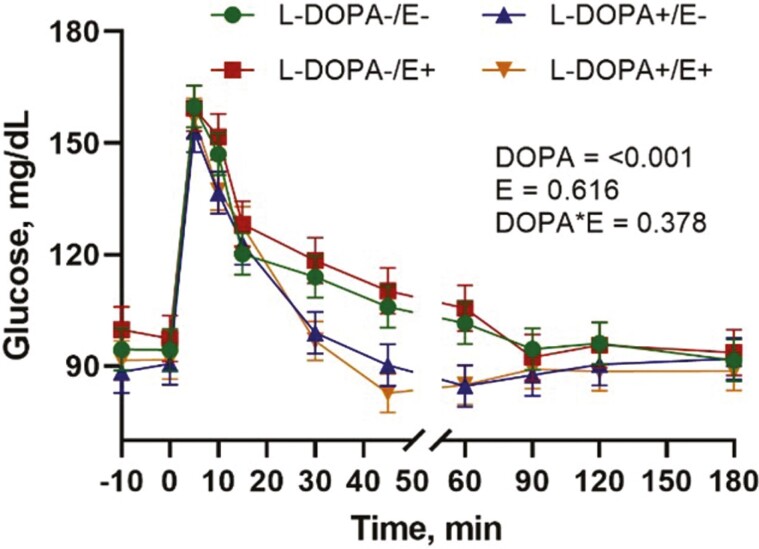

Glucose clearance rates at 5 to 15 and 30 to 60 min after the glucose dosing were not affected by L-DOPA or E+ administration (Table 5). However, the clearance rate at 15 to 30 min was higher with the infusion of L-DOPA (P < 0.001), but not with E+ (P = 0.280). Glucose AUC was lower (P = 0.006) in steers receiving L-DOPA with no differences (P = 0.897) between E+ and E−. Circulating glucose returned to baseline at 45 min after glucose infusion in steers receiving L-DOPA and at 90 min for steers without L-DOPA (Figure 6). There was no difference (P > 0.05) in glucose kinetics with E+.

Table 5.

Clearance rates and AUC of glucose in steers during a tolerance test while receiving tall fescue seeds without (E−) or with (E+) ergot alkaloids without (L-DOPA−) and with intra-abomasal infusion of L-DOPA+

| Item1 | L-DOPA− | L-DOPA+ | SEM2 | P-value3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E− | E+ | E− | E+ | DOPA | E | DOPA × E | ||

| k 5-15 | 2.77 | 2.07 | 2.21 | 2.16 | 0.437 | 0.49 | 0.484 | 0.346 |

| k 15-30 | 0.433 | 0.733 | 1.490 | 1.990 | 0.278 | <0.001 | 0.280 | 0.620 |

| k 30-60 | 0.375 | 0.447 | 0.520 | 0.390 | 0.206 | 0.753 | 0.852 | 0.461 |

| AUC | 19,401 | 19,672 | 17,991 | 17,564 | 548 | 0.006 | 0.897 | 0.508 |

1 k 5-15, k15-30, and k30-60 are glucose clearance rates (% per min) at 5 to 15, 15 to 30, and 30 to 60 min after glucose was infusion; AUC is area under curve of glucose from 0 to 180 min after glucose was infusion.

2SEM, n = 6.

3DOPA is the effect of L-DOPA infusion, E is the effect of ergot alkaloids, and DOPA*E is the interaction between L-DOPA and ergot alkaloids.

Figure 6.

Glucose tolerance test in steers receiving tall fescue seeds without (E−) or with (E+) ergot alkaloids without (L-DOPA−) and with (L-DOPA+) intra-abomasal infusion of L-DOPA. DOPA is the effect of L-DOPA infusion, E is the effect of ergot alkaloids, and DOPA*E is the interaction between L-DOPA and ergot alkaloids. Each value is expressed as the mean ± SE (n = 6).

Discussion

For the first time, the dopamine precursor L-DOPA was evaluated as a potential agonist to alleviate symptoms of fescue toxicosis. Fungal endophytes (Epichloë/Neotyphodium spp.) associated with grasses such as tall fescue (Schedonorus arundinaceus) and perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) are endemic in the United States, New Zealand, and Australia (Young et al., 2013; Caradus et al., 2022). Ergot alkaloids produced by those fungal endophytes can excite biogenic amine neurons causing physiological changes resulting in productive losses in cattle and other livestock species (Klotz, 2015; Sarich et al., 2023).

In the present study, the ergot alkaloids did not negatively affect the thermoregulation of the steers which was evidenced by unchanged rectal temperatures, RRs, and water intake. Fescue toxicosis can impair the animal’s ability to regulate core body temperature in a dose-dependent manner (Eisemann et al., 2014). According to Hume et al. (2016), toxic thresholds for alkaloid consumption were 0.40–0.75 μg/g DM for cattle. The ergot alkaloid concentration consumed (0.55 μg ergovaline/g DM) by steers in the current study was greater than the minimum threshold required to observe clinical symptoms of ergot alkaloid toxicosis in cattle. In addition, ergot alkaloid toxicosis was confirmed by decreased serum prolactin concentration. Serum prolactin is commonly utilized as an indicator of fescue toxicosis (Wilbanks et al., 2021; Hardin et al., 2022; Harlow et al., 2022; Cowan et al., 2023). The reduction of serum prolactin is caused by ergot alkaloids acting as an agonist on dopamine receptors which has inhibitory effects on prolactin synthesis (Kirsch et al., 2022).

The increase of serum prolactin in steers with fescue toxicosis and receiving L-DOPA might help to reestablish some physiological functions. Prolactin has many roles and affects metabolic homeostasis by regulating key enzymes and transporters that are associated with glucose and lipid metabolism in several target organs (Ben-Jonathan et al., 2006). The maintenance of normal physiological prolactin is critical for many functions and dopamine is the most important hypothalamic prolactin-inhibiting factor (Fitzgerald and Dinan, 2008). Thus, when ergot alkaloids bind to dopamine receptors, prolactin metabolism is unregulated. The reduction in feed intake, a classic symptom of fescue toxicosis, when E+ was administered could be caused by ergot alkaloids acting as an agonist for neurotransmitter receptors. It is well established that ergot alkaloid consumption is associated with a decrease in DMI (Baldwin et al., 2016; Ahn et al., 2020). The inhibitory effect of ergot alkaloids on feed intake depends on the dose and time of exposure being exacerbated by heat stress conditions (Gadberry et al., 2003; Craig et al., 2015). However, symptoms of heat stress did not occur indicating the receptor activity as the most likely cause of the reduced intake.

Ergot alkaloids have molecular similarities with the biogenic amine neurotransmitters (norepinephrine, epinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin) allowing them to bind to these receptors and interfere with the many associated functions (Bigal and Tepper, 2003; Klotz, 2015). However, ergot derivatives have slower dissociation rates that potentiate their action on receptor-binding sites (Unett et al., 2013). Overstimulation of dopamine receptors by ergot alkaloids could potentially explain the decreased DMI causing energy dysregulation. Dopamine signaling may function as a central caloric sensor that mediates adjustments in intake (Araujo et al., 2012).

The infusion of L-DOPA improved the DMI probably by reducing ergot alkaloid binding to the dopamine receptor. Agonist therapy, where the administration of medications that share neurobiological mechanisms of an undesirable drug cause a neurochemical normalization has been successfully used to treat neuromodulator drug dependence (Rothman and Baumann, 2006; Jordan et al., 2019). Although L-DOPA+ was not able to return the DMI to control levels, L-DOPA provided a small increase in DMI in steers experiencing fescue toxicosis. The partial recovery in DMI may provide evidence that ergot alkaloids reduce DMI intake by pathways besides dopamine receptors.

The increase in time spent eating with L-DOPA when the steers were receiving E+ can be associated with stimuli in the central nervous system (CNS) related to feed intake control. Dopamine neurons can trigger reward mechanisms and stimulate food seeking (Joshi et al., 2021). The actions of the dopaminergic system on feed intake are very complex with the majority of roles happening in the CNS and it is not completely understood, especially in farm animals. The mesolimbic dopamine system plays a key role in reward-related feeding behaviors in the nucleus accumbens (Cox and Witten, 2019; Wise and Robble, 2020; Joshi et al., 2021). The study of brain dopamine action is difficult in cattle. However, evaluation of circulating dopamine is more feasible, and it can provide important indications of dopamine metabolism (Tavares et al., 2021). In addition to being an indicator of dopamine concentrations in CNS, peripheral dopamine derived from the synaptic terminals regulates several processes such as hormone secretion, vascular tone, renal function, and gastrointestinal motility (Bucolo et al., 2019).

It is not clear if ergot alkaloids affect circulating dopamine in the bovine. In the current study, the toxicity was moderate with no changes in thermoregulation-related variables (rectal temperature, respiratory rates, and water intake), and it did not influence free or total dopamine concentrations in plasma. There is a lack of information on ruminants, but it has been reported that ergot alkaloid derivatives reduce dopamine synthesis (Tissari and Lillgäls, 1993; Filipov et al., 1999) through autoreceptor-mediated action in rodents (Tissari et al., 1983; Tissari and Lillgäls, 1993).

In the present study, the infusion of L-DOPA increased both circulating L-DOPA and dopamine severalfold without any adverse effects. Dopamine synthesis from L-DOPA is rapid because it bypasses tyrosine hydroxylase, the rate-limiting enzyme of dopamine synthesis (González-Sepúlveda et al., 2022). Dopamine does not cross the blood–brain barrier and it is functionally distinct from brain and peripheral metabolisms (Rubí and Maechler, 2010). However, L-DOPA can cross the blood–brain barrier and be used for dopamine synthesis in both central and peripheral nervous systems (Dayan and Finberg, 2003). Although the dopamine pools are independent between those systems, they also have interconnected responses that can occur by vagus-mediated dopamine neuron activity (Fernandes et al., 2020; Müller et al., 2022).

The lack of change in total norepinephrine and epinephrine with L-DOPA+ suggests that these neurotransmitters are more tightly regulated in the peripheral system than dopamine in the bovine. Norepinephrine is synthesized from dopamine by the enzyme dopamine β-hydroxylase and can be converted to epinephrine by the enzyme phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (Meiser et al., 2013). The decrease in free norepinephrine and epinephrine could be caused by the increase of catabolism as a protective action to avoid overstimulation of adrenoreceptors. Although there is a lack of information on cattle, treatment of rats with L-DOPA has shown a decrease in microdialysate levels of norepinephrine and an increase in metabolites from its catabolism (Dayan, 2003).

In contrast with the L-DOPA treatment that only affected free catecholamines, E+ caused a reduction in circulating free and total norepinephrine indicating a stronger feedback response to avoid overstimulation of adrenergic receptors potentially caused by the prolonged receptor binding by ergot alkaloids (Unett et al., 2013). Autoreceptors play a role in controlling excess noradrenaline release (Schlicker and Feuerstein, 2017). It has been reported that bromocriptine, an ergot alkaloid derivative that acts as a dopamine receptor agonist, decreases norepinephrine with no changes in epinephrine in humans (Van Loon and Sole, 1980; Steardo et al., 1986).

The increase of serotonin metabolites with L-DOPA administration provides evidence that dopamine influences serotonin metabolism. Dopamine and serotonin have some reciprocal activities and control. The presence of serotonin receptor proteins localized on neuronal components of the dopaminergic system has been reported (Van Bockstaele et al., 1994). In addition, serotonin neurons express dopamine receptors (Suzuki et al., 1998). Dopamine agonists can stimulate the firing rate of serotonin neurons and the local release of serotonin (Martín‐Ruiz et al., 2001).

The absence of the effect of E+ on glucose clearance could have been the result of moderate toxicosis as the exposure was relatively short. However, ergot alkaloids can increase plasma glucose in cattle by altering the glucose uptake (Browning and Thompson, 2002; Browning Jr, 2003; Eisemann et al., 2014). Bromocriptine, a synthetic ergot alkaloid and partial D2 receptor agonist, reduced insulin and glucose clearance following a glucose challenge in cattle indicating decreased insulin sensitivity and possibly, a disruption of glucose uptake in both cattle (Ferguson et al., 2023) and horses (Loos et al., 2022).

Peripheral dopamine plays a key role in the regulation of glucose metabolism and energy balance (Tavares et al., 2021). The L-DOPA infusion was efficient in improving glucose uptake and increasing the clearance rate in the GTT. Peripheral dopamine stimulates glucose uptake with its receptors being differentially involved in glucose uptake in the liver, pancreas, and skeletal tissues (Shankar et al., 2006; Tavares et al., 2021). Shankar et al. (2006) observed in an in vitro study that dopamine has a dose-dependent stimulatory effect through insulin secretion in rat pancreatic islets, with moderate doses stimulating insulin secretion, and high doses having inhibitory effects. Mice lacking whole-body D2R are glucose intolerant and exhibit abnormal insulin secretion (Garcia-Tornadú et al., 2010).

There is a lack of data about the dopaminergic regulation of glucose and insulin in ruminants. In nonruminant species, dopamine downregulates glucose-stimulated insulin secretion from pancreatic islets (Ustione et al., 2013). In a negative feedback loop, dopamine is synthesized in the β-cells from circulating L-DOPA and operates as an autocrine signal that is secreted with insulin, and causes a tonic inhibition on glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (Ustione et al., 2013). Although circulating L-DOPA and dopamine increased over 10-fold when the steers received L-DOPA, the glucose uptake was improved indicating that no negative feedback was triggered by high circulating dopamine. It is not clear if cattle have greater tolerance to high dopamine concentrations in pancreatic islets, or if there is an independency between circulating and presynaptic dopamine in the pancreas.

Conclusion

Intra-abomasal infusion of L-DOPA in moderate doses is efficient in increasing circulating dopamine without adverse effects for cattle. Administration of L-DOPA as agonist therapy to treat fescue toxicosis provided a moderate restoration of DMI for cattle with E+ seed exposure. Abomasal infusion of L-DOPA increases plasma glucose clearance, which could potentially suggest an improvement in glucose utilization by peripheral tissues. Further research is needed to determine the optimum dose of L-DOPA in animals experiencing fescue toxicosis, to better understand the ruminal metabolism of L-DOPA and if there is a practical role for L-DOPA in alleviating fescue toxicosis.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by Non-Assistance Cooperative Agreement, USDA-ARS Forage-Animal Production Research Unit and University of Kentucky Agricultural Experiment Station, Agreement Number: 5042-32630-004-009-S.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AUC

area under curve

- BW

body weight

- CL

confidence limit

- DMI

dry matter intake

- GTT

glucose tolerance tests

- L-DOPA

levodopa

- NEFA

nonesterified fatty acids

Contributor Information

Eriton E L Valente, Animal Science Department, State University of Western Parana, Marechal Cândido Rondon, PR, Brazil.

James L Klotz, Forage-Animal Production Research Unit, USDA-ARS, Lexington, KY, USA.

Ryana C Markmann, Animal Science Department, State University of Western Parana, Marechal Cândido Rondon, PR, Brazil.

Ronald J Trotta, Department of Animal and Food Science, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, USA.

J Lannett Edwards, Department of Animal Science, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, USA.

John B May, Department of Plant and Soil Sciences, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, USA.

David L Harmon, Department of Animal and Food Science, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, USA.

Conflict of interest statement. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Ahn, G., Ricconi K., Avila S., Klotz J. L., and Harmon D. L... 2020. Ruminal motility, reticuloruminal fill, and eating patterns in steers exposed to ergovaline. J. Anim. Sci. 98:1. doi: 10.1093/jas/skz374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich, C. G., Rhodes M. T., Miner J. L., Kerley M. S., and Paterson J. A... 1993. The effects of endophyte-infected tall fescue consumption and use of a dopamine antagonist on intake, digestibility, body temperature, and blood constituents in sheep. J. Anim. Sci. 71:158–163. doi: 10.2527/1993.711158x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [AOAC] Association of Official Analytical Chemists. 1990. Official Methods of Analysis. 15th ed. Washington (DC): AOAC International. [Google Scholar]

- Araujo, I. E., Ferreira J. G., Tellez L. A., Ren X., and Yeckel C. W... 2012. The gut–brain dopamine axis: a regulatory system for caloric intake. Physiol. Behav. 106:394–399. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.02.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslanoglou, D., Bertera S., Sánchez-Soto M., Benjamin Free R., Lee J., Zong W., Xue X., Shrestha S., Brissova M., Logan R. W.,. et al. 2021. Dopamine regulates pancreatic glucagon and insulin secretion via adrenergic and dopaminergic receptors. Transl. Psychiatry. 11:59. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-01171-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, R. L., Capuco A. V., Evock-Clover C. M., Grossi P., Choudhary R. K., Vanzant E. S., Elsasser T. H., Bertoni G., Trevisi E., Aiken G. E.,. et al. 2016. Consumption of endophyte-infected fescue seed during the dry period does not decrease milk production in the following lactation. J. Dairy Sci. 99:7574–7589. doi: 10.3168/jds.2016-10993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Jonathan, N., Hugo E. R., Brandebourg T. D., and LaPensee C. R... 2006. Focus on prolactin as a metabolic hormone. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 17:110–116. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2006.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, J. K., Chestnut A. B., Erickson B. H., and Kelly F. M... 1993. Effects of prepartum consumption of endophyte-infested tall fescue on serum prolactin and subsequent milk production of Holstein cows. J. Dairy Sci. 76:1928–1933. doi: 10.3168/jds.s0022-0302(93)77526-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bigal, M. E., and Tepper S. J... 2003. Ergotamine and dihydroergotamine: a review. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 7:55–62. doi: 10.1007/s11916-003-0011-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boomsma, F., Alberts G., van der Hoorn F. A. J., Man in ‘t Veld A. J., and Schalekamp M. A. D. H.. 1992. Simultaneous determination of free catecholamines and epinine and estimation of total epinine and dopamine in plasma and urine by high-performance liquid chromatography with fluorimetric detection. J. Chromatogr. 574:109–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Box, G. E. P., and Cox D. R... 1964. An analysis of transformations. J. R. Stat. Soc. Series B Stat Methodol. 26:211–243. doi: 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1964.tb00553.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Browning, R., Jr. 2003. Effect of ergotamine on plasma metabolite and insulin-like growth factor-1 concentrations in cows. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. 135:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s1532-0456(03)00048-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning, R., and Thompson F. N... 2002. Endocrine and respiratory responses to ergotamine in Brahman and Hereford steers. Vet. Hum. Toxicol. 44:149–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucolo, C., Leggio G. M., Drago F., and Salomone S... 2019. Dopamine outside the brain: the eye, cardiovascular system and endocrine pancreas. Pharmacol. Ther. 203:107392. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2019.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caradus, J. R., Card S. D., Finch S. C., Hume D. E., Johnson L. J., Mace W. J., and Popay A. J... 2022. Ergot alkaloids in New Zealand pastures and their impact. New Zeal. J. Agric. Res. 65:1–41. doi: 10.1080/00288233.2020.1785514 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan, V. E., Chohan M., Blakley B. R., McKinnon J., Anzar M., and Singh J... 2023. Chronic ergot exposure in adult bulls suppresses prolactin but minimally impacts results of typical breeding soundness exams. Theriogenology. 197:71–83. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2022.11.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox, J., and Witten I. B... 2019. Striatal circuits for reward learning and decision-making. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 20:482–494. doi: 10.1038/s41583-019-0189-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig, A. M., Klotz J. L., and Duringer J. M... 2015. Cases of ergotism in livestock and associated ergot alkaloid concentrations in feed. Front. Chem. 3:1–6. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2015.00008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayan, L., and Finberg J. P. M... 2003. L-DOPA increases noradrenaline turnover in central and peripheral nervous systems. Neuropharmacology. 45:524–533. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(03)00190-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egert-McLean, A. M., Sama M. P., Klotz J. L., McLeod K. R., Kristensen N. B., and Harmon D. L.. 2019. Automated system for characterizing short-term feeding behavior and real-time forestomach motility in cattle. Comput. Electron. Agric. 167:105037. doi: 10.1016/j.compag.2019.105037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eisemann, J. H., Huntington G. B., Williamson M., Hanna M., and Poore M... 2014. Physiological responses to known intake of ergot alkaloids by steers at environmental temperatures within or greater than their thermoneutral zone. Front. Chem. 2:96. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2014.00096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, T. D., Loos C. M. M., Vanzant E. S., Urschel K. L., Klotz J. L., and McLeod K. R... 2023. Impact of ergot alkaloid and steroidal implant on whole-body protein turnover and expression of mTOR pathway proteins in muscle of cattle. Front. Vet. Sci. 10:1104361. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2023.1104361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, A. B., Alves da Silva J., Almeida J., Cui G., Gerfen C. R., Costa R. M., and Oliveira-Maia A. J... 2020. Postingestive modulation of food seeking depends on vagus-mediated dopamine neuron activity. Neuron. 106:778–788.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipov, N. M., Thompson F. N., Tsunoda M., and Sharma R. P... 1999. Region-specific decrease of dopamine and its metabolites in brains of mice given ergotamine. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A. 56:47–58. doi: 10.1080/009841099158222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald, P., and Dinan T. G... 2008. Prolactin and dopamine: what is the connection? A review article. J. Psychopharmacol. 22:12–19. doi: 10.1177/0269216307087148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foote, A. P., Penner G. B., Walpole M. E., Klotz J. L., Brown K. R., Bush L. P., and Harmon D. L... 2014. Acute exposure to ergot alkaloids from endophyte-infected tall fescue does not alter absorptive or barrier function of the isolated bovine ruminal epithelium. Animal. 8:1106–1112. doi: 10.1017/S1751731114001141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadberry, M. S., Denard T. M., Spiers D. E., and Piper E. L... 2003. Effects of feeding ergovaline on lamb performance in a heat stress environment. J. Anim. Sci. 81:1538–1545. doi: 10.2527/2003.8161538x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Tornadú, I., Perez-Millan M. I., Recouvreux V., Ramirez M. C., Luque G., Risso G. S., Ornstein A. M., Cristina C., Diaz-Torga G., and Becu-Villalobos D... 2010. New insights into the endocrine and metabolic roles of dopamine D2 receptors gained from the Drd2–/– mouse. Neuroendocrinology. 92:207–214. doi: 10.1159/000321395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Sepúlveda, M., Omar M. Y., Hamdon S., Ma G., Rosell-Vilar S., Raivio N., Abass D., Martínez-Rivas A., Vila M., Giraldo J.,. et al. 2022. Spontaneous changes in brain striatal dopamine synthesis and storage dynamics ex vivo reveal end-product feedback-inhibition of tyrosine hydroxylase. Neuropharmacology. 212:109058. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2022.109058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Grajales, L. A., Pieper L., Mengel S., and Staufenbiel R.. 2018. Evaluation of glucose dose on intravenous glucose tolerance test traits in Holstein-Friesian heifers. J. Dairy Sci. 101:774–782. doi: 10.3168/jds.2017-13215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardin, K. N., dos Reis B. R., Dias N. W., Fiske D. A., Mercadante V. R. G., Rhoads M. L., Wilson T. B., and White R. R... 2022. Growth and reproductive responses of heifers consuming endophyte-infected tall fescue seed with or without sodium bicarbonate supplementation. Appl. Anim. Sci. 38:317–325. doi: 10.15232/aas.2022-02273 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow, B. E., Flythe M. D., Goodman J. P., Ji H., and Aiken G. E... 2022. Isoflavone containing legumes mitigate ergot alkaloid-induced vasoconstriction in goats (Capra hircus). Animals (Basel). 12:750. doi: 10.3390/ani12060750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hume, D. E., Ryan G. D., Gibert A., Helander M., Mirlohi A., and Sabzalian M. R... 2016. Epichloë fungal endophytes for grassland ecosystems. In: Lichtfouse E., editor, Sustainable agriculture reviews, vol. 19. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; p. 233–305. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-26777-7_6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, C. J., Cao J., Newman A. H., and Xi Z. -X... 2019. Progress in agonist therapy for substance use disorders: lessons learned from methadone and buprenorphine. Neuropharmacology. 158:107609. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, A., Kool T., Diepenbroek C., Koekkoek L. L., Eggels L., Kalsbeek A., Mul J. D., Barrot M., and la Fleur S. E... 2021. Dopamine D1 receptor signalling in the lateral shell of the nucleus accumbens controls dietary fat intake in male rats. Appetite. 167:105597. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2021.105597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch, P., Kunadia J., Shah S., and Agrawal N... 2022. Metabolic effects of prolactin and the role of dopamine agonists: a review. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 13:1002320. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.1002320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein, M. O., Battagello D. S., Cardoso A. R., Hauser D. N., Bittencourt J. C., and Correa R. G... 2019. Dopamine: functions, signaling, and association with neurological diseases. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 39:31–59. doi: 10.1007/s10571-018-0632-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klotz, J. L. 2015. Activities and effects of ergot alkaloids on livestock physiology and production. Toxins (Basel). 7:2801–2821. doi: 10.3390/toxins7082801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson, B. T., Sullivan D. M., Samford M. D., Kerley M. S., Paterson J. A., and Turner J. T... 1994. D2 dopamine receptor response to endophyte-infected tall fescue and an antagonist in the rat. J. Anim. Sci. 72:2905–2910. doi: 10.2527/1994.72112905x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson, B. T., Samford M. D., Camden J. M., Piper E. L., Kerley M. S., Paterson J. A., and Turner J. T... 1995. Ergovaline binding and activation of D2 dopamine receptors in GH4ZR7 cells. J. Anim. Sci. 73:1396–1400. doi: 10.2527/1995.7351396x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson, B. T., Harmon D. L., Piper E. L., Griffis L. M., and Bush L. P... 1999. Alkaloid binding and activation of D2 dopamine receptors in cell culture. J. Anim. Sci. 77:942–947. doi: 10.2527/1999.774942x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebe, D. M., and White R. R... 2018. Meta-analysis of endophyte-infected tall fescue effects on cattle growth rates. J. Anim. Sci. 96:1350–1361. doi: 10.1093/jas/sky055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loos, C. M. M., Urschel K. L., Vanzant E. S., Oberhaus E. L., Bohannan A. D., Klotz J. L., and McLeod K. R... 2022. Effects of bromocriptine on glucose and insulin dynamics in normal and insulin dysregulated horses. Front. Vet. Sci. 9:1:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.889888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín‐Ruiz, R., Ugedo L., Honrubia M. A., Mengod G., and Artigas F... 2001. Control of serotonergic neurons in rat brain by dopaminergic receptors outside the dorsal raphe nucleus. J. Neurochem. 77:762–775. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00275.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiser, J., Weindl D., and Hiller K... 2013. Complexity of dopamine metabolism. Cell Commun. Signal. 11:34. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-11-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller, S. J., Teckentrup V., Rebollo I., Hallschmid M., and Kroemer N. B... 2022. Vagus nerve stimulation increases stomach-brain coupling via a vagal afferent pathway. Brain Stimul. 15:1279–1289. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2022.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahimabadi, P. D., Yourdkhani S., Rajabi M., Sedaghat R., Golchin D., and Asgari Rad H... 2022. Ergotism in feedlot cattle: clinical, hematological, and pathological findings. Comp. Clin. Path. 31:281–291. doi: 10.1007/s00580-022-03331-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman, R. B., and Baumann M. H... 2006. Balance between dopamine and serotonin release modulates behavioral effects of amphetamine-type drugs. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1074:245–260. doi: 10.1196/annals.1369.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubí, B., and Maechler P... 2010. Minireview: new roles for peripheral dopamine on metabolic control and tumor growth: let’s seek the balance. Endocrinology. 151:5570–5581. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sa, M., Ying L., Tang A. -G., Xiao L. -D., and Ren Y. -P... 2012. Simultaneous determination of tyrosine, tryptophan and 5-hydroxytryptamine in serum of MDD patients by high performance liquid chromatography with fluorescence detection. Clin. Chim. Acta. 413:973–977. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2012.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarich, J. M., Stanford K., Schwartzkopf-Genswein K. S., McAllister T. A., Blakley B. R., Penner G. B., and Ribeiro G. O... 2023. Effect of increasing concentration of ergot alkaloids in the diet of feedlot cattle: performance, welfare, and health parameters. J. Anim. Sci. 101:skad287. doi: 10.1093/jas/skad287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlicker, E., and Feuerstein T... 2017. Human presynaptic receptors. Pharmacol. Ther. 172:1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar, E., Santhosh K., and Paulose C... 2006. Dopaminergic regulation of glucose-induced insulin secretion through dopamine D2 receptors in the pancreatic islets in vitro. IUBMB Life. 58:157–163. doi: 10.1080/15216540600687993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, S. S., and Wilk. M. B.. 1965. An Analysis of Variance Test for Normality (Complete Samples). Biometrika. 52:591. doi: 10.2307/2333709 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley, D. R., and Creese I.. 1983. Interactions of ergot alkaloids with anterior pituitary D-2 dopamine receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 23:585–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spears, J. W., Whisnant C. S., Huntington G. B., Lloyd K. E., Fry R. S., Krafka K., Lamptey A., and Hyda J... 2012. Chromium propionate enhances insulin sensitivity in growing cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 95:2037–2045. doi: 10.3168/jds.2011-4845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steardo, L., Di Stasio E., Bonuso S., and Maj M... 1986. The effect of bromocriptine on plasma catecholamine concentrations in normal volunteers. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 29:713–715. doi: 10.1007/BF00615964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland, J. R., Looper M. L., Matthews J. C., Rosenkrans C. F., Flythe M. D., and Brown K. R... 2011. Board-invited review: St. Anthony’s Fire in livestock: causes, mechanisms, and potential solutions. J. Anim. Sci. 89:1603–1626. doi: 10.2527/jas.2010-3478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, M., Hurd Y. L., Sokoloff P., Schwartz J. -C., and Sedvall G... 1998. D3 dopamine receptor mRNA is widely expressed in the human brain. Brain Res. 779:58–74. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01078-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavares, G., Martins F. O., Melo B. F., Matafome P., and Conde S. V... 2021. Peripheral dopamine directly acts on insulin-sensitive tissues to regulate insulin signaling and metabolic function. Front. Pharmacol. 12:713418. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.713418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tissari, A. H., and Lillgäls M. S... 1993. Reduction of dopamine synthesis inhibition by dopamine autoreceptor activation in striatal synaptosomes with in vivo reserpine administration. J. Neurochem. 61:231–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03559.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tissari, A. H., Rossetti Z. L., Meloni M., Frau M. I., and Gessa G. L... 1983. Autoreceptors mediate the inhibition of dopamine synthesis by bromocriptine and lisuride in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 91:463–468. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(83)90171-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unett, D. J., Gatlin J., Anthony T. L., Buzard D. J., Chang S., Chen C., Chen X., Dang H. T. M., Frazer J., Le M. K.,. et al. 2013. Kinetics of 5-HT 2B receptor signaling: profound agonist-dependent effects on signaling onset and duration. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 347:645–659. doi: 10.1124/jpet.113.207670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ustione, A., Piston D. W., and Harris P. E... 2013. Minireview: dopaminergic regulation of insulin secretion from the pancreatic islet. Mol. Endocrinol. 27:1198–1207. doi: 10.1210/me.2013-1083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente, E. E. L., Klotz J. L., Egert-McLean A. M., Costa G. W., May J. B., and Harmon D. L... 2023. Influence of intra-abomasal administration of L-DOPA on circulating catecholamines and feed intake in cattle. Front. Anim. Sci. 4:1–11. doi: 10.3389/fanim.2023.1127575 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele, E. J., Cestari D. M., and Pickel V. M... 1994. Synaptic structure and connectivity of serotonin terminals in the ventral tegmental area: potential sites for modulation of mesolimbic dopamine neurons. Brain Res. 647:307–322. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91330-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Loon, G. R., and Sole M. J... 1980. Plasma dopamine: source, regulation, and significance. Metabolism. 29:1119–1123. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(80)90020-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilbanks, S. A., Justice S. M., West T., Klotz J. L., Andrae J. G., and Duckett S. K... 2021. Effects of tall fescue endophyte type and dopamine receptor D2 genotype on cow-calf performance during late gestation and early lactation. Toxins (Basel). 13:195. doi: 10.3390/toxins13030195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise, R. A., and Robble M. A... 2020. Dopamine and Addiction. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 71:79–106. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-103337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young, C. A., Hume D. E., and McCulley R. L... 2013. Forages and pastures symposium: fungal endophytes of tall fescue and perennial ryegrass: pasture friend or foe?. J. Anim. Sci. 91:2379–2394. doi: 10.2527/jas.2012-5951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]