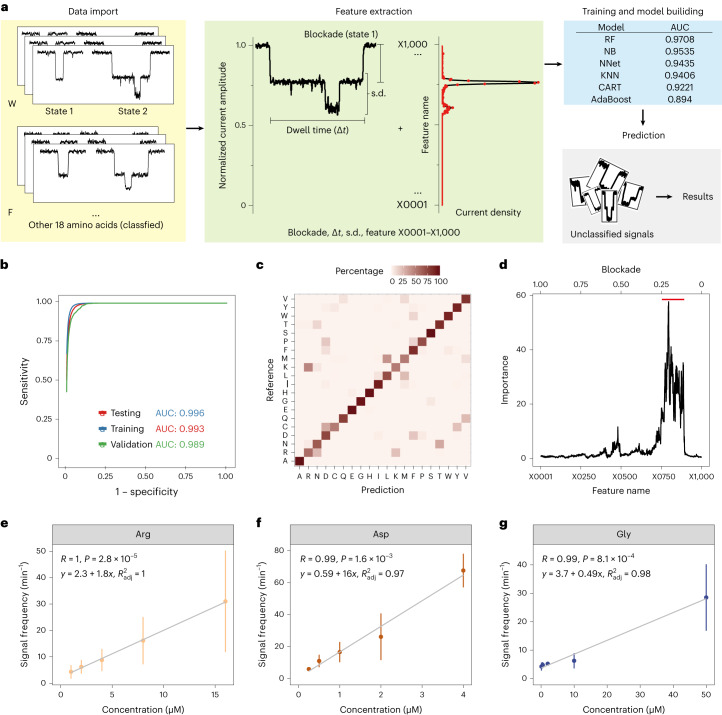

Fig. 3. Amino acid identification assisted by a machine-learning algorithm.

a, Illustration of the training process. First, signals corresponding to classified state 1 (one amino acid bound) and state 2 (two of the same amino acid bound) for each type of amino acid were imported and normalized. Then, the state 1 blockade, dwell time and s.d. were extracted. Additionally, 1,000 data points, named feature X0001–X1000, were extracted from the current density of each signal (from 0 to 1 with an interval of 0.001). Model performance was tested, including RF, NB, NNet, KNN, bagged CART and AdaBoost. RF outperformed the other models, achieving an AUC of 0.990. A tenfold cross-validation was used to prevent overfitting. b, The receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) of the RF model for the training, testing and independent validation data sets of state 1 signals for all 20 amino acids. c, Confusion matrix of amino acid classification generated by the RF model using feature matrix. d, Feature importance generated from training of RF for state 1 signals of all 20 amino acids. The upper x axis represents the corresponding blockade of each feature. Features within the range of state 1 blockade of all amino acids have a higher importance value (marked by the red line). e,f,g, Scatter plot of signal frequency versus concentration of amino acids (Arg (e), Asp (f) and Gly (g)). The data are presented as mean ± s.d. The R and P values were calculated on the basis of Pearson correlation. The formulas and adjusted R2 values were computed on the basis of linear regression. n ≥ 3 independent experiments.