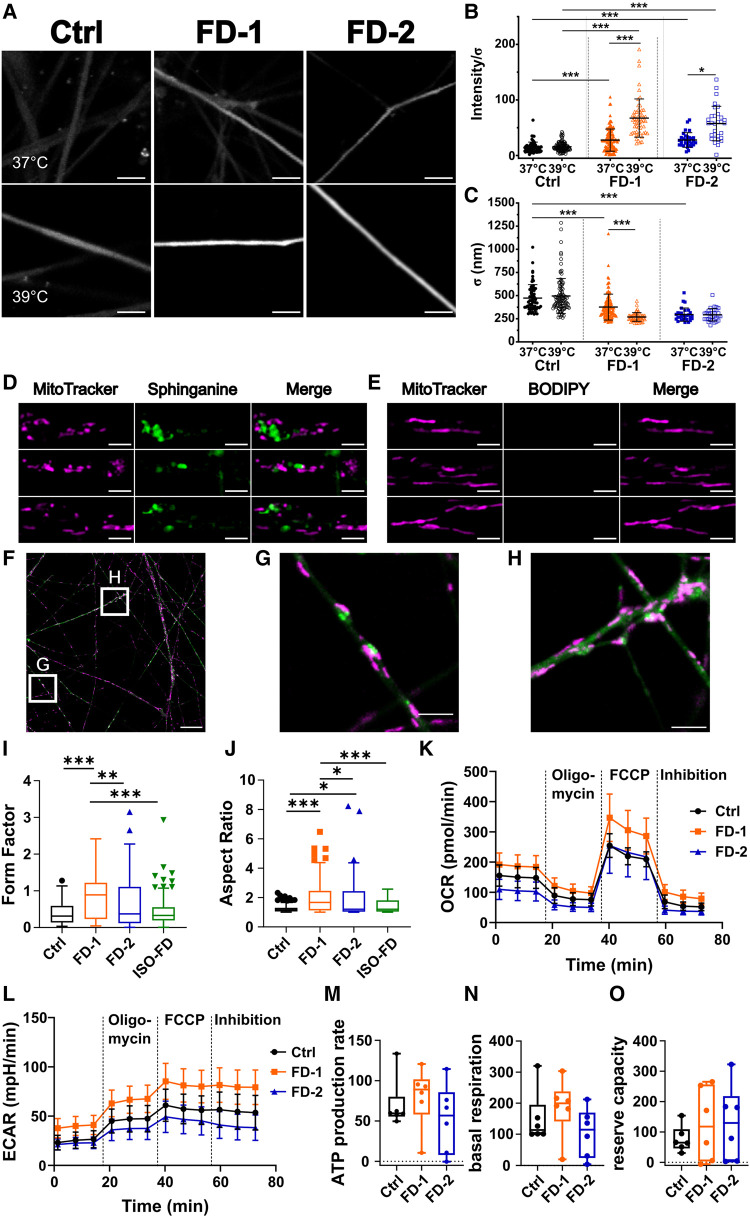

Figure 6.

Sensory neuron heat stimulation and mitochondrial characteristics. (A) Exemplified micrographs from firing neurons at 37°C (upper row) and 39°C (lower row). Scale bars: 5 μm. (B) FD-1 and FD-2 neurons show higher activity at 37°C (FD-1: n = 1 clone, 179 neurites; FD-2: n = 1 clone, 30 neurites) and increased calcium signalling after incubation at 39°C (FD-1: n = 1 clone; 56 neurites; FD-2: n = 1 clone, 31 neurites), whereas the Ctrl did not show an increase upon heat (37°C: n = 1 clone, 63 neurites; 39°C: n = 1 clone, 103 neurites). Each data point shows activity of one neurite, and data are represented as mean ± SD. Kruskal–Wallis (χ2 = 181.1, P < 0.0001) followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test. (C) FD-1 and FD-2 neurons show a generalized decrease in neurite diameter, and FD-1 shows further thinning upon heat stimulation. n = 1 clone (B). Each data point shows diameter of one neurite, and data are represented as mean ± SD. Kruskal–Wallis (χ2 = 173.1, P < 0.0001) followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test. (D) Metabolic labelling with sphinganine in Ctrl neurons reveals mitochondrial fragmentation in the vicinity of accumulations. Scale bars: 2 μm. (E) In contrast, incubation of Ctrl neurons with BODIPY only shows normal mitochondrial morphology. Scale bars: 2 μm. (F) Still image of mitochondria tracking of FD-1 neurons. Scale bar: 25 μm. (G) Still image of mitochondria/sphinganine interaction. Scale bar: 5 μm. (H) Still image of potential mitochondrial block by sphinganine. Scale bar: 5 μm. (G) + (H) Cropped from (F). (I) FD-1 neurons show mitochondria with an increased form factor compared to all other cell lines. Kruskal–Wallis (χ2 = 36.8, P < 0.0001) followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test. (J) FD-1 and FD-2 neuronal mitochondria show an increased aspect ratio compared with Ctrl. Aspect ratio of FD-1 neuronal mitochondria is increased compared with FD-2. Kruskal–Wallis (χ2 = 35.41, P < 0.0001) followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test. For (I) + (J): pooled data from n = 2 clones/line, obtained from three individual differentiations each was used (20 photomicrographs per differentiation = 60 per clone were analysed). Data are represented as Tukey boxplot. (K) Comparison of OCR of Ctrl and FD neurons using Seahorse assay showed no difference in cellular metabolism. Two-way ANOVA [F(22, 165) = 12.43, P = 0.39] followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison correction. (L) ECAR was similar between neurons from Ctrl and neurons from FD patients. Two-way ANOVA [F(22, 165) = 1.52, P = 0.07] followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison correction. For (K–L): each data point represents the mean ± SEM of three individual differentiations of n = 2 clones/line. (M) Seahorse assay showed no difference in ATP production. Kruskal–Wallis (χ2 = 6.75, P = 0.08) followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test. (N) No differences in basal respiration. Kruskal–Wallis (χ2 = 7.4, P = 0.06) followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test. (O) Reserve capacity was comparable between Ctrl and Fabry patients. Kruskal–Wallis (χ22 = 2.09, P = 0.55) followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test. For (M–O): each data point (n = 6) represents measurement of one individual differentiation from one clone. Data are represented as Tukey boxplot. Seahorse assay was performed from three individual differentiations of n = 2 clones/line. Ctrl, control; FD-1, FD-2, patients with Fabry disease; ECAR, extracellular acidification rate; FCCP, carbonyl cyanide-p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone; ISO-FD, isogenic Fabry line; OCR, oxygen consumption rate. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.