Abstract

Purpose

We have previously shown that low-dose interleukin-2 (IL-2) and 13-cis-retinoic acid (13-cis-RA) improved lymphocyte and natural killer (NK) cell count of patients with advanced tumors showing a clinical benefit from chemotherapy. The primary endpoint of this study was to ask whether IL-2 and 13-cis-RA improved (-0%) lymphocyte and NK cell count in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (MCRC) that had a clinical benefit from induction chemotherapy. Secondary endpoint was the evaluation of toxicity, progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS).

Patients and methods

Forty patients with MCRC, showing a clinical benefit from chemotherapy, were treated with subcutaneous low-dose IL-2 (1.8 × 106 IU) and oral 13-cis-RA (0.5 mg/kg) in order to maintain responses and improve survival through the increase of lymphocyte and NK cells. The biological parameters and the clinical outcome of these patients were compared with those of a control group of patients (80) with a similar disease status, including clinical benefit from chemotherapy.

Results

The most common adverse events were mild cutaneous skin rash and fever. After 4 months and 2 years of biotherapy, a statistically significant improvement was observed in lymphocyte and number of NK cells with respect to baseline values and to controls. After a median follow-up of 36 months, median PFS was 27.8 months, while median OS was 52.9 months.

Conclusion

These data show that maintenance immunotherapy with low-dose IL-2 and oral 13-cis-RA in patients with MCRC showing a clinical benefit from chemotherapy is feasible, has a low toxicity profile, improves lymphocyte and NK cell count. An improvement in the expected PFS and OS was also observed. A randomized trial is warranted.

Keywords: Maintenance therapy, Metastatic colorectal cancer, Interleukin-2, 13-cis-retinoic acid, Lymphocyte, Natural killer cells

Introduction

Colorectal carcinoma is the second most common cancer in the western world; in Europe more than 200,000 patients die each year due to metastatic colorectal cancer (MCRC) [3]. In recent years we have witnessed a continuous improvement in the treatment of all stages of colorectal cancer. In the adjuvant setting, the introduction of oxaliplatin combined with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and leucovorin (FOLFOX) has improved the clinical outcome of patients with early colorectal cancer [2]. Further progress has been made in the treatment of metastatic disease by adding biological agents such as bevacizumab or cetuximab to irinotecan-5-FU-based combination chemotherapy [8, 18]. However, when colorectal cancer becomes metastatic, it has a severe prognosis, and while surgery of metastases may prolong survival in selected cases, chemotherapy has only a palliative role. Patients with MCRC experience relapse due to cancer stem cells that are generally resistant to chemotherapy and that form minimal residual disease (MRD). Minimal residual disease, which may be present even in patients with a complete response, is often made of tumor cells with a low proliferation rate. These stem cells may leave their state of dormancy and begin to proliferate [25].

The host immune response plays a key role in controlling metastatic spread, MRD, and survival in patients with colorectal cancers [26]. Failure of T cells from tumor-bearing host to effectively recognize and eliminate tumor cells is one of the major factors of tumor escape from immune system control. This is attributed to inhibition of signal transduction in these cells [12]. Another possible mechanism is an effect induced by accumulation of immature myeloid cells (Gr-1+CD115 cells) in tumor bearing hosts that inhibit T cells function in cancer patients [12]. The T-cell growth factor, interleukin-2 (IL-2) increases T-cell proliferation and the generation of cytotoxic T-lymphocytes. IL-2 also induces activation of T- and B-cells and enhances the tumoricidal activity of natural killer cells (NK) [36]. Another important function of IL-2 is the termination of T-cell response and maintenance of self-tolerance [9, 38]. In fact, as most tumor antigens are self-proteins, the immune system inhibits the generation of a robust immunity via toleragenic mechanisms, such as the elaboration of T-regulatory cells (Treg), which function to prevent autoimmunity and limit inflammation [34]. Gr-1+CD115+ immature myeloid suppressor cells, that inhibit T-cell function, mediate the development of tumor-induced Treg and T-cell anergy in tumor-bearing host [17].

Retinoids, which are powerful inhibitors of angiogenesis, have shown synergistic effects with IL-2 in increasing γ-interferon production, which in turn has antiangiogenic properties [10]. Recently it has been also demonstrated that retinoids may help in the differentiation of immature myeloid suppressor cells, improving the immune response [14, 21].

Tumor angiogenesis also plays an important role in tumor growth and invasion [25]. Elevated serum vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a marker of increased angiogenesis, correlates with tumor volume, higher relapse risk, and poorer survival in patients with operable colorectal cancer [5].

We previously found that the optimal biological dose of IL-2 in combination with 0.5 mg/kg of oral 13-cis-retinoic acid (13-cis-RA) was as low as 1.8 × 106 IU [27]; this dose, given as maintenance therapy, was free of the severe toxicity described for high-dose IL-2 [33]. Treatment with low doses of 13-cis-RA improved some of the prognostically relevant immunological parameters, such as lymphocyte and NK cell counts, as well as improving the CD4+/CD8+ ratio in patients that had a clinical benefit after induction chemotherapy [28]. Moreover, the combination of IL-2 and 13-cis-RA produced a sustained decrease in serum VEGF, and 12% of patients beginning the therapy as partial responders (PRs) were converted to complete responders [31].

The primary endpoint of the present study was to determine whether IL-2 with 13-cis-RA improved the lymphocyte and NK count in a group of 40 patients with MCRC, who had obtained a clinical benefit from chemotherapy with respect to baseline values. Additionally, lymphocyte and NK count were compared with the same parameters of 80 MCRC historical control patients well matched for all characteristics. The secondary endpoints were the assessments of progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in order to determine whether additional prospective randomized studies of this combination therapy were warranted, in consideration of the results obtained with the same drugs in our patients with MCRC [30].

Patients and methods

Patient selection

Patients were included in the study if they met the following criteria: (1) a histologically confirmed diagnosis of MCRC; (2) were either a PR or had stable disease (SD) with measurable lesions or a complete response (CR) after chemotherapy, as defined by the response evaluation criteria in solid tumors (RECIST) [37]; (3) an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0-; (4) a life expectancy of more than 3 months; (5) normal renal and hepatic function; (6) a white blood cell (WBC) count of more than 2,500 mm3, hemoglobin more than 9 g/dl, a platelet cell count of more than 100,000 mm-; (7) normal cardiac function. The exclusion criteria included major organ failure, CNS metastases, second tumors, active infections, autoimmune diseases, or significant primary or secondary immunodeficiency. Forty patients were enrolled that met the above criteria.

Eighty patients, with MCRC, were selected as historical control, from a large pool of patients treated by members of the “Istituto Oncologico Regione Abruzzo e Molise-(IORAM) with the FOLFOX regimen in the same period of time [30]. The biological characteristic (lymphocyte and NK cell count, and CD4+/CD8+ ratio) of these patients was compared with the same characteristics of the study patients. Unfortunately VEGF was not routinely done and; therefore, is not available.

This phase II study was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki and the EU guidelines on good clinical practice and was approved by the local ethics committee. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Treatment

The induction chemotherapy, consisting of oxaliplatin 50 mg/m2 fractionated over two consecutive days, followed by leucovorin bolus and 5-FU continuous infusion, has been described in full elsewhere [30]. One month after the last course of chemotherapy, having ascertained that a CR, PR or SD had been achieved, and after an analysis of the immunological parameters, patients underwent treatment with self-administered subcutaneous IL-2 (Aldesleukin; Chiron Corp, Emeryville, CA) at the dose of 1.8 × 106 IU daily at bedtime, 5 days/week, plus oral 13-cis-RA (Roaccutan; Roche, Nutley, NJ) at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg body weight, given with meals for 5 days/week for 3 weeks each month [27, 28, 31]. Sites of injection were rotated daily. After 1 week of rest, patients started a new 3-week course of therapy. Two months (two 3-week courses plus two 1-week rest periods) were considered as one cycle of therapy. After completion of 1 year of treatment, responding patients continued to receive the same therapy for 2 weeks each month for the second year. In the third year, patients received the same therapy for 1 week each month. Patients exhibiting evidence of disease progression were removed from the study and treated with salvage chemotherapy, and were included in the analysis on an intention-to-treat principle. The 80 control patients were uniformly treated with 12 courses of chemotherapy with the FOLFOX regimen. The rates of use of second- or third-line therapies that might have affected survival were well balanced between the two groups.

Study evaluations

Pretreatment evaluations included a complete medical history, physical, and radiological (CT and X-ray) examination in conjunction with ultrasound, vital signs, and performance status according to ECOG. Clinical laboratory tests were also conducted, including hematology, biochemistry, carcinoembryonic antigen, and immunological testing (lymphocyte and NK cell count, and CD4+/CD8+ ratio). X-rays of abnormal areas of bone-scan uptake were performed, and CT scanning was used to evaluate hepatic lesions. Before each subsequent course of treatment, all patients had a further blood cell count and measurement of plasma urea, electrolytes, serum creatinine, AST, ALT, alkaline phosphatase, and bilirubin. Patients were also tested for thyroid function, triglycerides, and VEGF by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), as previously described [31]. In addition, a WBC count was repeated weekly, with follow-up visits performed monthly during treatment. Patients were assessed for disease progression during the study by physical examination and CT scanning for measurable or assessable disease every 4 months until recurrence, or sooner if the patient appeared to have disease progression. Peripheral blood samples for immunologic study were drawn from all of the patients at baseline and before each cycle of immunotherapy. Counts of NK cells, B-lymphocytes, and CD4+/CD8+ cells and their ratios were obtained from whole blood by means of flow cytometry.

Statistical considerations

The study was designed to test the hypothesis that a maintenance immunotherapy regimen could improve lymphocyte and NK counts in MCRC patients showing a clinical benefit from chemotherapy. A positive response was defined as an increase of -0% from baseline values of lymphocyte and NK cell counts, in the absence of any clinical or radiological evidence of disease progression, for at least 4 months. Simon’s optimal two-stage design was used [35]. The first stage required that three or more patients out of 17 had a confirmed response, to rule out a undesiderably low response probability of 0.20 (P 0), in favor of a desirable response probability of 0.40 (P 1), with a 10% probability of accepting a poor agent (α = 0.1) and a 10% probability of rejecting a good agent (β = 0.1) before proceeding to the second stage. In the second stage, 37 assessable patients could be added and if a total of 10 or more patients achieved a confirmed response, then the primary endpoint would have been met. The results were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of determinations made in three different experiments. Post hoc comparisons were performed by Tukey’s honestly significant difference test. For variables not normally distributed (CD4+/CD8+), the Friedman repeated measures ANOVA by ranks was used. Post hoc comparisons were performed by Wilcoxon rank sign test with a downward adjustment of a level, to compensate for multiple comparisons. The time to relapse was defined as the time between the start of immunotherapy and any relapse, or any appearance of a second primary cancer or death, whichever occurred first. OS was measured from study entry to death, or study entry to 28 February 2006, for censored patients. Statistical analysis was performed with SAS statistical software (version 8.12, 2000, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC), while PFS and OS were determined using the Kaplan–Meier method [19]. All comparisons of patients-characteristics, response rates, and toxicity profiles were performed using Pearson’s χ2 contingency table analysis. The log-rank test was used to compare PFS and OS of both groups.

Results

Patient characteristics

The 40 patients, with a median age of 63 years, were enrolled in the study between April 1999 and December 2004. All patients received at least two courses of immunotherapy and are evaluable for efficacy and safety analysis. The patients, who had previously received a total of 560 courses of chemotherapy (mean 14 per patient), were treated with a total of 265 courses of immunotherapy, with a mean of 6.6 courses per patient. Median PFS from surgery to disease recurrence had been 10 months (range 2.5-8) for 6 patients, while 34 patients (85%) were staged as stage IV at the diagnosis. Characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. Liver and pelvic metastasectomy had been performed in five and two patients, respectively. Second- or third-line therapies, administered to seven patients, were as follows: 5-FU/leucovorin/irinotecan [32], and/or gemcitabine with 5-FU/leucovorin modulation. Baseline immunological characteristics of the patients and controls, including lymphocyte and NK counts, and the CD4+/CD8+ ratio are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients

| Characteristics | IL-2 | Controls | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | |

| No. of patients | 40 | 100 | 80 | 100 |

| Age, years | ||||

| Median, range | 63 (41-0) | 64 (31-4) | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Males | 26 | 65 | 50 | 63 |

| Females | 14 | 35 | 30 | 37 |

| Performance status (ECOG) | ||||

| 0- | 37 | 92 | 71 | 88 |

| 2 | 3 | 8 | 9 | 12 |

| Stage at diagnosis (UICC) | ||||

| II–III | 6 | 15 | 29 | 36 |

| Disease-free interval | 10 months | 12 months | ||

| IV | 34 | 85 | 51 | 64 |

| Localization | ||||

| Right | 10 | 25 | 23 | 29 |

| Left | 19 | 47 | 37 | 46 |

| Rectal | 11 | 28 | 20 | 25 |

| Tumor grade | ||||

| Mucinous | 3 | 8 | 6 | 8 |

| II | 23 | 57 | 45 | 56 |

| III | 14 | 35 | 29 | 36 |

| Metastatic sites | ||||

| Peritoneum | 11 | 28 | 8 | 12 |

| Liver | 18 | 45 | 34 | 42 |

| Bones | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Locoregional | 3 | 7 | 6 | 7 |

| Nodes | 2 | 5 | 5 | 6 |

| - metastatic sites | 5 | 13 | 26 | 32 |

| Metastasectomy | ||||

| Liver | 5 | 7 | ||

| Other sites | 2 | 4 | ||

| Response to chemotherapy | ||||

| CR | 10 | 25 | 18 | 23 |

| PR | 11 | 27 | 21 | 26 |

| SD | 19 | 48 | 41 | 51 |

| Immunological parameters | ||||

| Lymphocyte/mm3 | 1,776 ± 119 | 1,838 ± 124 | P = 0.9 | |

| NK/mm3 | 344 ± 44 | 275 ± 17 | P = 0.1 | |

| CD4+/CD8+ | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.04 | P = 0.3 | |

CR complete response, PR partial response, SD stable disease

Toxicity

Standard World Health Organization (WHO) criteria for assessing toxicity were used. No treatment-related deaths were observed. The toxicity profile was mild, with no grade 3 or 4 toxicity among the 40 patients entered into the study. Cutaneous toxicity (skin rash) was observed in 29% of patients. Twenty percent of patients treated with IL-2/13-cis-RA also had grade 1 or 2 fever. Mild hypothyroidism occurred in two patients, and grade 1 triglyceride elevation was observed in four patients.

Response and survival

An increase of 44, 45.3, and 49% in the lymphocyte count was observed after 4 months of immunotherapy in the first three patients, while the increase in NK count was 272.4, 48.8, and 110.7%. These results met the criteria established to continue the study.

After 4 month of immunotherapy, the mean increment of lymphocytes of all 40 evaluable patients was 37.8% (95% CI, 28-7%) (P < 0.001), while the mean increment of NK was 81% (95% CI, 54-08%) (P < 0.05). Indeed, immunotherapy improved not only lymphocyte and NK count, but also the CD4+/CD8+ ratio and decreased plasma VEGF levels. In fact, the CD4+/CD8+ ratio mean increment was 49% (95% CI, 27-0%); the baseline value of CD4+/CD8+ ratio of 1.4 ± 0.1 increased to 1.7 ± 0.1 (P < 0.005).

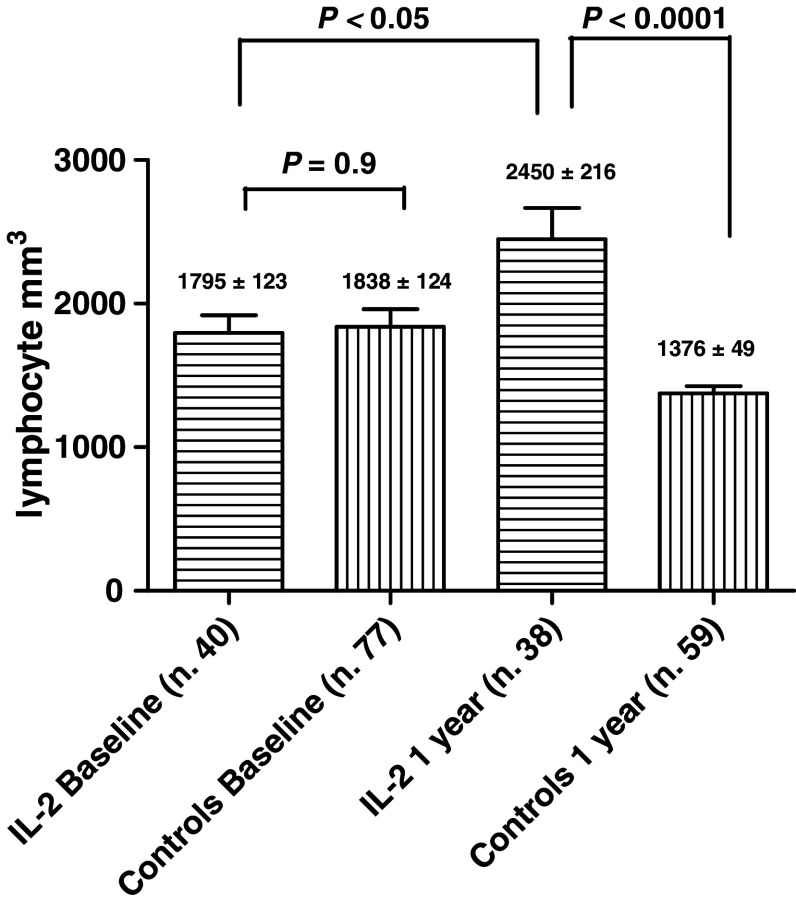

After 1 year, the lymphocyte counts of treated patients increased sharply, not only with respect to controls (P < 0.0001), but also with respect to baseline values (P < 0.05; Fig. 1). After 2 years the difference became more evident, with a mean number of lymphocytes of 2,607 ± 257 (P < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Lymphocyte counts of the two treatment groups, at baseline and after 1 year. Baseline values were not statistically different (P = 0.9). After 1 year, the difference became statistically significant (P < 0.0001)

The baseline NK count did not differ between the two arms (P = 0.1). After 1 year of maintenance therapy, the number of NK cells increased with respect to baseline values (P < 0.05) and with respect to controls (P < 0.0001; Fig. 2). After 2 years, the differences with respect to baseline values and to controls remained evident (P < 0.05).

Fig. 2.

NK counts of the two treatment groups, at baseline and after 1 year. Baseline values were not statistically different (P = 0.1). After 1 year, the difference became statistically significant (P < 0.0001)

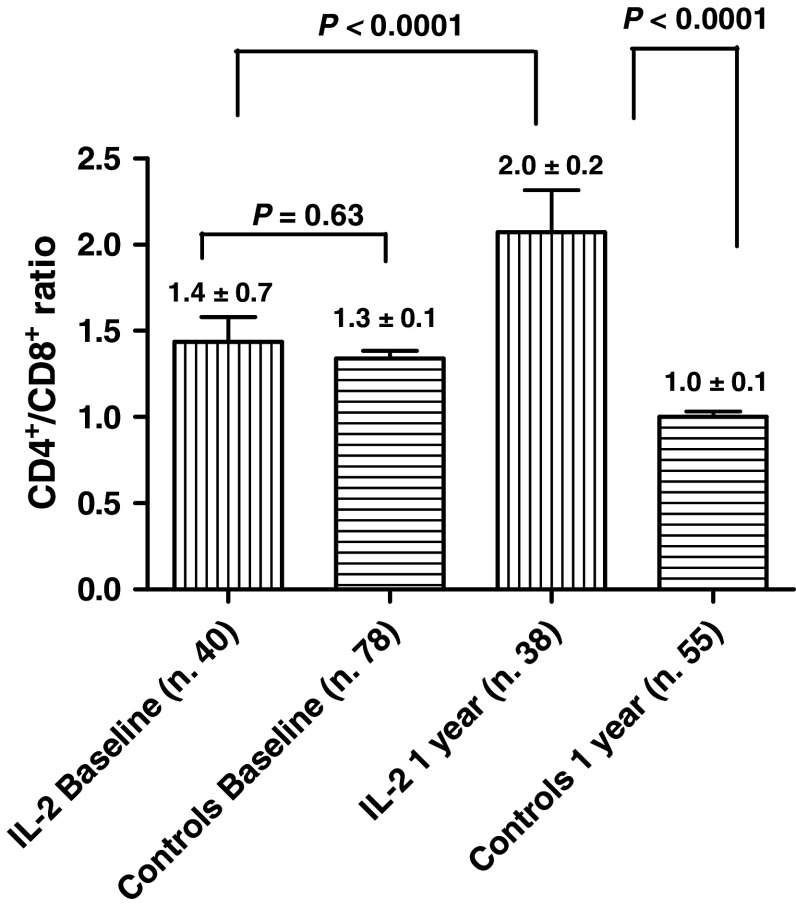

The baseline CD4+/CD8+ ratios of IL-2/RA-treated patients and of controls were not statistically different (P = 0.3). After 1 year, in the treatment arm, the CD4+/CD8+ ratio increased from the baseline value of 1.4 ± 0.7 to a value of 2.0 ± 0.2 (P < 0.0001; Fig. 3). In the second year, while in the control arm, the CD4+/CD8+ ratio decreased from the baseline value of 1.43 ± 0.15 to 0.92 ± 0.08 (P < 0.05), in the treated group the CD4+/CD8+ ratio was 2.46 ± 0.2 (P < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

CD4+/CD8+ ratios of the two treatment groups, at baseline and after 1 year. Baseline values were not statistically different (P = 0.3). After 1 year, the difference became statistically significant (P < 0.0001)

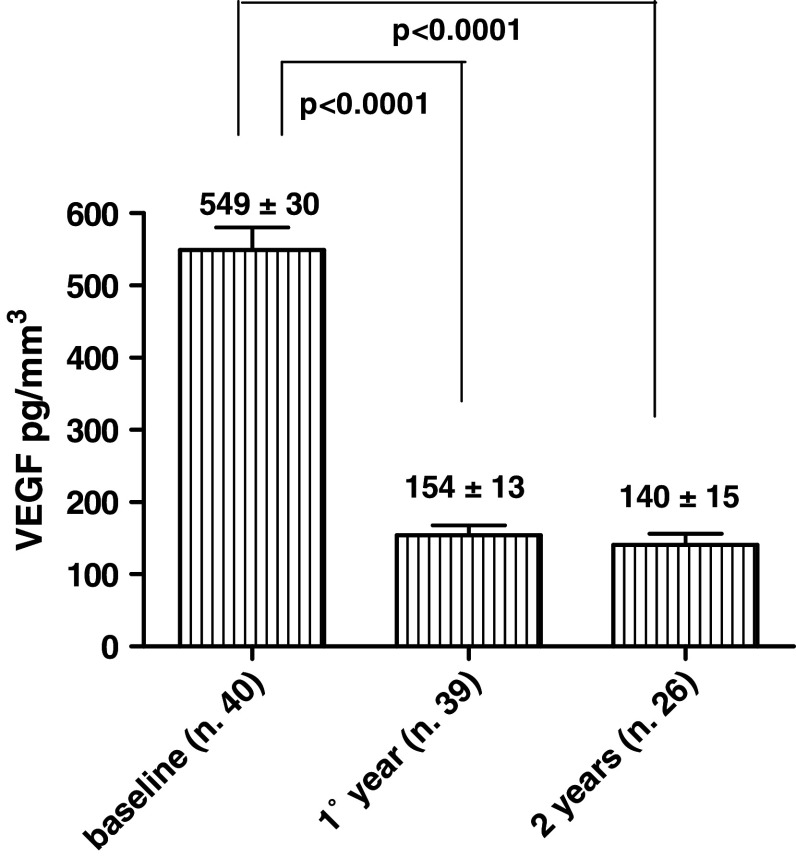

A substantial reduction in VEGF was observed. In fact, after 1 year the baseline value of 549 ± 30 ng/ml decreased to a mean value of 154 ± 13 ng/ml (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 4); after 2 years, the value remained low (140 ± 15 ng/ml). In the 17 patients who were progression-free beyond 13 months, all immunological parameters (lymphocyte, NK, and CD4+/CD8+ ratio) continued to be improved, compared with baseline values.

Fig. 4.

The baseline value of VEGF was 549 ± 30 pg/mm3. After 1 year it decreased to a mean value of 154 ± 13 pg/mm3 (P < 0.0001). After 2 years, the value remained low 140.6 ± 15 pg/mm3 (P < 0.0001)

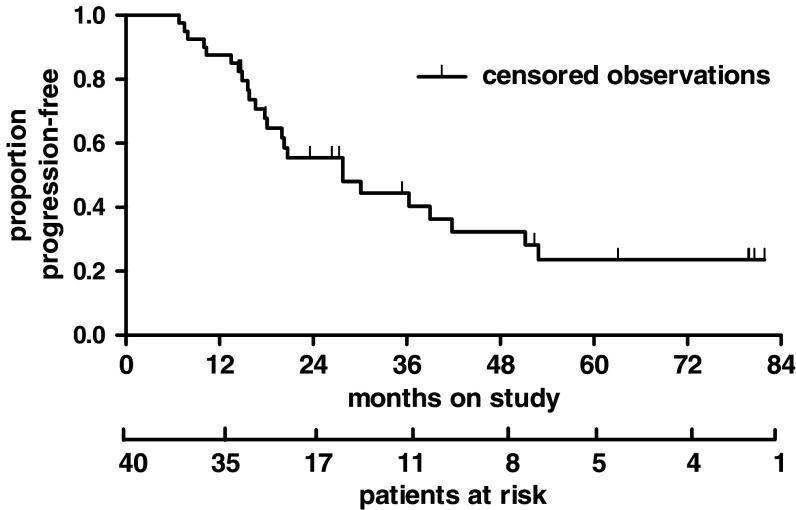

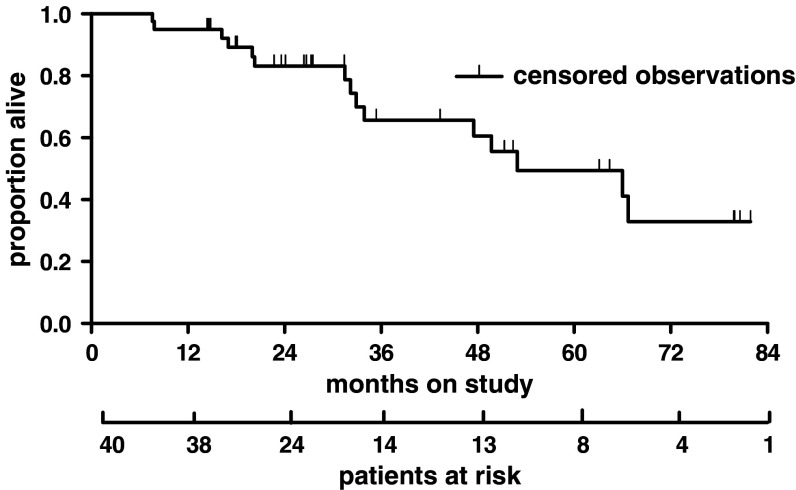

After a median follow-up of 36 months, the median PFS was 27.8 months (range 6.8-1.9 months) (Fig. 5) in the treatment group and 12.5 months in the control group (P < 0.0001, log-rank test). Patients treated with maintenance therapy had a median OS of 52.9 months (range 7.6-1.9 months) (Fig. 6), while controls survived for a median time of 20.2 months (P < 0.0001, log-rank test).

Fig. 5.

Progression-free survival (PFS): events 24 (60%), censored 16 (40%), median PFS: 27.8 months

Fig. 6.

Overall survival (OS): events 15 (37.5%), censored 25 (62.5%), median OS 52.9 months

Discussion

This phase II study was designed to ask whether IL-2 and 13-cis-RA improved the immunological profile of patients with MCRC who had had a clinical benefit from chemotherapy. The secondary endpoint was the determination of progression-free and OS in order to establish whether an additional randomized study of this therapy was justified, in consideration of the results obtained with the same drugs in patients with MCRC previously treated by us [30] and by members of the IORAM.

Several strategies have been adopted to improve the clinical outcomes of MCRC. One of the strategies has been maintenance chemotherapy. This approach was tested in a large randomized trial that compared the best available chemotherapy regimens for the treatment of 905 patients with MCRC [23]. Participants with a CR, PR, or SD after 24 weeks of chemotherapy were randomized to receive continuous or intermittent chemotherapy. The study suggested that there was no clear benefit from continuing maintenance chemotherapy until disease progression; in fact, OS was similar in the three groups (9.8, 10.2, and 8.9 months, respectively).

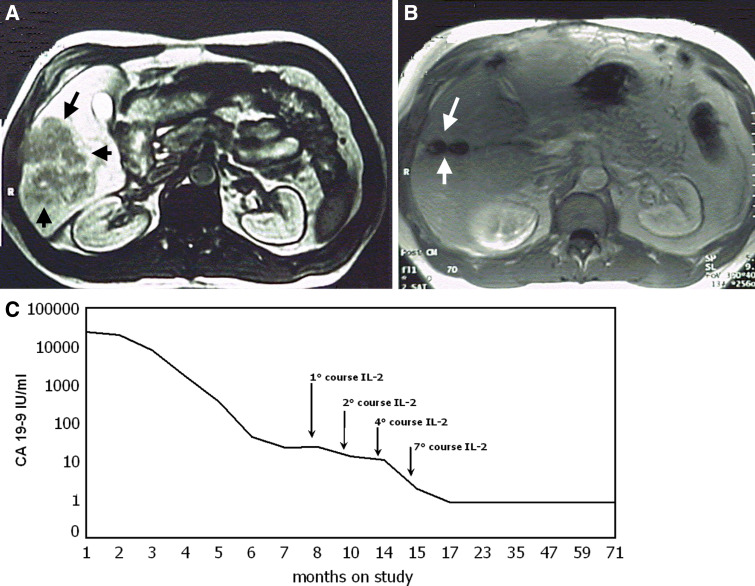

Another strategy has been the addition of α-interferon to chemotherapy (5-FU with or without folinic acid) for the treatment of patients with MCRC. Several randomized trials have shown that patients randomized to chemotherapy plus interferon experienced more toxic effects with no advantage in response rate, PFS or OS, with respect to patients randomized to chemotherapy alone [13, 16, 20, 29]. Various reasons may be identified for such negative results. Toxicity was worse in the interferon arm and induced several patients to abandon the studies. In addition, the interferon treatment was given for a relatively short period of time. Conflicting results have been obtained adding a biological agent (α-interferon) to 13-cis-RA in the treatment of patients with progressive metastatic renal cell carcinoma [1, 24]. Several reasons may be identified for these differing results. Not all patients were nephrectomized; the performance status that has been shown as one of the most important prognostic factors was variable; the dose of 1 mg/kg of 13-cis-RA given all days causes stomatitis, dryness in mouth and nose, and dermatologic toxicity; therefore, a low compliance. Moreover the administration schedule of the drug is important; in the therapies with biological response modifiers, low-doses administered for a long period of time, with intermittent schedules may be better than higher doses given for a short period of time with a better quality of life [15]. In our study we have shown that the treatment with IL-2 and 13-cis-RA was administered and gave a benefit for prolonged period of times (Figs. 7, 8). In the presence of a neoplastic disease, the T-cell dysfunction must be considered as a chronic disease, like diabetes that requires insulin therapy as long as it exists.

Fig. 7.

Computed tomography (CT) scan of a 45-year-old male with large liver metastases. The patient was treated with FOLFOX (oxaliplatin, leucovorin, and 5-FU), followed by low-dose subcutaneous IL-2 and oral 13-cis-RA. Baseline CT scan (a), CT scan after six treatment cycles (b), and CT scan following embolization of the right branch of the vena porta and right liver lobectomy (c)

Fig. 8.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of a 47-year-old male presented with intestinal obstruction from rectal cancer, liver metastases, and large peritoneal nodes. The patient was treated with FOLFOX (oxaliplatin, leucovorin, and 5-FU), followed by low-dose subcutaneous IL-2 and oral 13-cis-RA. Baseline MRI (a), MRI after six treatments cycles (b), and carbohydrate antigen 19.9 (CA-19-9) levels continued to be abnormal after resection of residual disease, but normalized with IL-2 + 13-cis-RA therapy (c)

The introduction of monoclonal antibodies into clinical practice has shed a new light in the treatment of advanced colorectal cancer; bevacizumab, added to 5-FU-based combination chemotherapy has resulted in a statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement of 4.7 months in OS among patients with MCRC [18]. Thus, chemotherapy and biologic therapy may be complementary treatments, as chemotherapy induces apoptosis and antigen remodeling, while IL-2 sustains the immune response by promoting the proliferation and clonal expansion of effector lymphocyte precursors [7].

Recombinant high-dose IL-2 (600,000-20,000 IU/kg) has produced responses, with some long-term remissions in the treatment of patients with chemotherapy-refractory metastatic solid tumors including colorectal carcinoma [33]; however, this treatment showed significant toxicity, often-requiring admission to an intensive care unit [33]. In searching for a less toxic, biologically active dose of IL-2 in a phase 1B study [27] and a phase II randomized study [31], we have demonstrated that a dose of 1.8 × 106 IU of IL-2 with 13-cis-RA, was well tolerated and elicited immunological responses that were not statistically different from those elicited by higher doses; in addition, the combination of low-dose IL-2 with 13-cis-RA was very active in reducing VEGF levels [31]. VEGF, a major regulator of angiogenesis, might be a perfect target for tumor growth inhibition in maintenance therapy, as high expression of VEGF is an unfavorable prognostic factor [5]. In addition, it has been shown that tumor neo-angiogenesis may be initiated and maintained by bone marrow—derived stem endothelial cells [22]. For this reason, an effective antiangiogenic therapy might not only inhibit the growth of MRD but also prevent disease recurrence. There is a data in the literature showing that perioperative IL-2 therapy decreases both VEGF and the recurrence rate of colorectal cancer patients [4]. Our patients receiving IL-2 plus 13-cis-RA displayed both improved lymphocyte and NK cell counts, and a major reduction in serum VEGF that paralleled the clinical course. In fact, disease progression was anticipated by measurements showing deterioration of all measured immunological parameters at least 2 months before clinical progression was observed. Prolonged responses were observed for all histologic grades (G2, G3) and types (e.g., well and poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas and mucinous carcinoma), indicating the efficacy of the IL-2/13-cis-RA combination.

These findings suggest that continuous administration of low-dose IL-2 can achieve long-term restoration of immune parameters and reduction of VEGF levels [30]. In our study, seven patients obtained a clear benefit from the biotherapy, improving their PR to a CR. Continuous administration of low-dose IL-2 to patients with MRD, who obtain clinical benefit from chemotherapy, might have the same outcome as in vitro experiments in which lymphocytes are incubated with tumor cells; following injection of IL-2 in patients, the host immune effector cells in the presence of MRD, may act as lymphocyte-activated killer cells. Moreover it has been shown that high-dose IL-2 resulted in a significant decrease of Treg in patients achieving an objective clinical response to IL-2 therapy [6], and also, retinoids may help in the differentiation of the Gr-1+CD115+ immature myeloid suppressor cells, improving the immune response [14, 21].

The lymphocyte count is a biomarker of the host response to subcutaneous IL-2 treatment and is useful for multimodal clinical assessment, as it may predict OS in advanced cancer patients independently of tumor response and of main clinical characteristics [11]. In this study, changes in these biological parameters paralleled and predated the clinical improvement. The immunological parameters examined in this study (lymphocyte and NK numbers and the CD4+/CD8+ ratio) and the serum concentration of VEGF can be considered as surrogate markers for clinical outcome. In this study, changes in these biological parameters paralleled the clinical improvement. We have also shown that some of the biological markers (lymphocyte, NK, CD4+/CD8+, and VEGF) can be identified as intermediate endpoints, and that monitoring them may be very useful.

We conclude that the administration of subcutaneous IL-2 at a dose of 1.8 × 106 IU/day together with an oral 13-cis-RA dose of 0.5 mg/kg on an intermittent, long-term schedule is feasible, has low toxicity, and results in a sustained improvement of lymphocyte, NK, and CD4+/CD8+ ratio and a decrease in VEGF levels. This biological therapy may have the potential to delay disease progression in patients with MCRC with CR, PR, or SD following oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy. These results also indicate that an additional randomized study of this therapy is warranted.

References

- 1.Aass N, De Mulder PH, Mickisch GH, Mulders P, van Oosterom AT, van Poppel H, Fossa SD, de Prijck L, Sylvester RJ. Randomized phase II/III trial of interferon alfa-2a with and without 13-cis-retinoic acid in patients with progressive metastatic renal cell carcinoma: the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Genito-Urinary Tract Cancer Group (EORTC 30951) J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4172–4178. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andre T, Boni C, Mounedji-Boudiaf L, Navarro M, Tabernero J, Hickish T, Topham C, Zaninelli M, Clingan P, Bridgewater J, Tabah-Fisch I, de Gramont A. Multicenter international study of oxaliplatin/5-fluorouracil/leucovorin in the adjuvant treatment of colon cancer (MOSAIC) investigators. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2343–2351. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyle P, Ferlay J. Cancer incidence and mortality in Europe. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:481–488. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brivio F, Lissoni P, Rovelli F, Nespoli A, Uggeri F, Fumagalli L, Gardani G. Effects of IL-2 preoperative immunotherapy on surgery-induced changes in angiogenic regulation and its prevention of VEGF increase and IL-12 decline. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49:385–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cascinu S, Graziano F, Valentini M, Catalano V, Giordani P, Staccioli MP, Rossi C, Baldelli AM, Grianti C, Muretto P, Catalano G. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression, S-phase fraction and thymidylate synthase quantitation in node-positive colon cancer: relationships with tumor recurrence and resistance to adjuvant chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2001;12:239–244. doi: 10.1023/A:1008339408300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cesana GC, Gail DeRaffele G, Cohen S, Moroziewicz D, Mitcham J, Stoutenburg J, Cheung K, Hesdorffer C, Kim-Schulze S, Kaufman HL. Characterization of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in patients treated with high-dose interleukin-2 for metastatic melanoma or renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1169–1177. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Correale P, Cusi MG, Tsang KY, Del Vecchio MT, Marsili S, La Placa M, Intrivici C, Equino A, Micheli L, Nencini C, Ferrari F, Giorni G, Bonmassar E, Guido Francini G. Chemo-immunotherapy of metastatic colorectal carcinoma with gemcitabine plus FOLFOX 4 followed by subcutaneous granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukin-2 induces strong immunologic and antitumor activity in metastatic colon cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8950–8958. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.12.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cunningham D, Humblet Y, Siena S, Khayat D, Bleiberg H, Santoro A, Bets D, Mueser M, Harstrick A, Verslype C, Chau I, Van Cutsem E. Cetuximab monotherapy and cetuximab plus irinotecan in irinotecan-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:337–345. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Disis ML, Kim Lyerly K. Global role of the immune system in identifying cancer initiation and limiting disease progression. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8923–8925. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fox FE, Kubin M, Cassin M, Niu Z, Trinchieri G, Cooper KD, Rook AH. Retinoids synergize with interleukin-2 to augment IFN-gamma and interleukin-12 production by human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1999;19:407–415. doi: 10.1089/107999099314117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fumagalli LA, Vinke J, Hoff W, Ypma E, Brivio F, Nespoli A. Lymphocyte independently predict overall survival in advanced cancer patients: a biomarker for IL-2 immunotherapy. J Immunother. 2003;26:394–402. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200309000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gabrilovich DI, Velders MP, Sotomayor EM, Kast WM. Mechanism of immune dysfunction in cancer mediated by immature Gr-1+ myeloid cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:5398–5406. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greco FA, Figlin R, York M, Einhorn L, Schilsky R, Marshall EM, Buys SS, Froimtchuk MJ, Schuller J, Schuchter L, Buyse M, Ritter L, Man A, Yap AK. Phase III randomized study to compare interferon alfa-2a in combination with fluorouracil versus fluorouracil alone in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:2674–2681. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.10.2674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hengesbach L, Hoag K. Physiological concentrations of retinoic acid favor myeloid dendritic cell development over granulocyte development in cultures of bone marrow cells from mice. J Nutr. 2004;134:2653–2659. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.10.2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herberman RB. Design of clinical trials biological response modifiers. Cancer Treat Rep. 1985;69:1161–1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hill M, Norman A, Cunningham D, Findlay M, Nicolson V, Hill A, Iveson A, Evans C, Joffe J, Nicolson M. Royal Marsden phase III trial of fluorouracil with or without interferon alfa-2b in advanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:1287–1290. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.6.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang B, Pan PY, Li Q, Sato AI, Levy DE, Bromberg J, Divino CM, Chen SH. Gr-1+CD115+ immature myeloid suppressor cells mediate the development of tumor-induced T regulatory cells and T-cell anergy in tumor-bearing host. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1123–1131. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, Cartwright T, Hainsworth J, Heim W, Berlin J, Baron A, Griffing S, Holmgren E, Ferrara N, Fyfe G, Rogers B, Ross R, Kabbinavar F. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2335–2342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. doi: 10.2307/2281868. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kosmidis PA, Tsavaris N, Skarlos D, Theocharis D, Samantas E, Pavlidis N, Briassoulis E, Fountzilas G. Fluorouracil and leucovorin with or without interferon alfa-2b in advanced colorectal cancer: analysis of a prospective randomized phase III trial. Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:2682–2687. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.10.2682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kusmartsev S, Cheng F, Yu B, Nefedova Y, Sotomayor E, Lush R, Gabrilovich D. All-trans-retinoic acid eliminates immature myeloid cells from tumor-bearing mice and improves the effect of vaccination. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4441–4449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mancuso P, Burlini A, Pruneri G, Goldhirsch A, Martinelli G, Bertolini F. Resting and activated endothelial cells are increased in the peripheral blood of cancer patients. Blood. 2001;97:3658–3661. doi: 10.1182/blood.V97.11.3658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maughan TS, James RD, Kerr DJ, Ledermann JA, McArdle C, Seymour MT, Cohen D, Hopwood P, Johnston C, Stephens RJ, British MRC Colorectal Cancer Working Party Comparison of survival, palliation, and quality of life with three chemotherapy regimens in metastatic colorectal cancer: a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1555–1563. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08514-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Motzer RJ, Murphy BA, Bacik J, Schwartz LH, Nanus DM, Mariani T, Loehrer P, Wilding G, Fairclough DL, Cella D, Mazumdar M. Phase III trial of interferon alfa-2a with or without 13-cis-retinoic acid for patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2972–2980. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.16.2972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Naumov GN, Bender E, Zurakowski D, Kang SY, Sampson D, Flynn E, Watnick RS, Straume O, Akslen LA, Folkman J, Almog N. A model of human tumor dormancy: an angiogenic switch from the nonangiogenic phenotype. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:316–325. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pages F, Berger A, Camus M, Sanchez-Cabo F, Costes A, Molidor R, Mlecnik B, Kirilovsky A, Nilsson M, Damotte D, Meatchi T, Bruneval P, Cugnenc PH, Trajanoski Z, Fridman WH, Galon J. Effector memory T cells, early metastasis, and survival in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2654–2666. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Recchia F, De Filippis S, Rosselli M, Saggio G, Cesta A, Fumagalli L, Rea S. Phase IB study of subcutaneously administered interleukin-2 in combination with 13-cis retinoic acid as maintenance therapy in advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:1251–1257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Recchia F, De Filippis S, Rosselli M, Saggio G, Fumagalli L, Rea S. Interleukin-2 and 13-cis retinoic acid in the treatment of minimal residual disease: a phase II study. Int J Oncol. 2002;20:1275–1282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Recchia F, Nuzzo A, Lalli A, Lombardo M, Di Lullo L, Fabiani F, Fanini R, Venturoni L, Torchio P, Peretti G. Randomized trial of 5-fluorouracil and high-dose folinic acid with or without alpha-2b interferon in advanced colorectal cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 1996;19:301–304. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199606000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Recchia F, Rea S, Nuzzo A, Lalli A, Di Lullo L, De Filippis S, Saggio G, Biondi E, Massa E, Mantovani G. Oxaliplatin fractionated over two days with bimonthly leucovorin and 5-fluorouracil in metastatic colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2004;24:1935–1940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Recchia F, Saggio G, Cesta A, Alesse E, Gallo R, Necozione S, Rea S. Phase II randomized study of interleukin-2 with or without 13-cis retinoic acid as maintenance therapy in patients with advanced cancer responsive to chemotherapy. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:3149–3157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Recchia F, Saggio G, Nuzzo A, Lalli A, Lullo LD, Cesta A, Rea S. Multicentre phase II study of bifractionated CPT-11 with bimonthly leucovorin and 5-fluorouracil in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer pretreated with FOLFOX. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:1442–1444. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosenberg SA, Lotze MT, Yang JC, Aebersold PM, Linehan WM, Seipp CA, White DE. Experience with the use of high-dose interleukin-2 in the treatment of 652 cancer patients. Ann Surg. 1989;210:474–484. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198910000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakaguchi S. Naturally arising CD4+ regulatory T cells for immunologic self-tolerance and negative control of immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:531–562. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simon R. Optimal two-stage designs for phase II clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1989;10:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(89)90015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith KA. Interleukin-2: inception, impact and implications. Science. 1988;240:1169–1176. doi: 10.1126/science.3131876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, Verweij J, Van Glabbeke M, van Oosterom AT, Christian MC, Gwyther SG. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thomas R, Malek TR, Bayer AL. Tolerance, not immunity, crucially depends on IL-2. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:665–674. doi: 10.1038/nri1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]