Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma is a deadly cancer with growing incidence for which immunotherapy is one of the most promising therapeutic approach. Peptide-based vaccines designed to induce strong, sustained CD8+ T cell responses are effective in animal models and cancer patients. We demonstrated the efficacy of curative peptide-based immunisation against a unique epitope of SV40 tumour antigen, through the induction of a strong CD8+ T cell-specific response, in our liver tumour model. However, as in human clinical trials, most tumour antigen epitopes did not induce a therapeutic effect, despite inducing strong CD8+ T cell responses. We therefore modified the tumour environment to enhance peptide-based vaccine efficacy by delivering mengovirus (MV)-derived RNA autoreplicating sequences (MV-RNA replicons) into the liver. The injection of replication-competent RNA replicons into the liver converted partial tumour regression into tumour eradication, whereas non-replicating RNA had no such effect. Replicating RNA replicon injection induced local recruitment of innate immunity effectors (NK and NKT) to the tumour and did not affect specific CD8+ T cell populations or other myelolymphoid subsets. The local delivery of such RNA replicons into tumour stroma is therefore a promising strategy complementary to the use of peripheral peptide-based vaccines for treating liver tumours.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), Animal model, Cytotoxic T cells, Immunotherapy, RNA-replicons, Tumour stroma

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common fatal cancers affecting humans [21]. Due to its fatal course, several therapeutic approaches, including immunotherapy, must be combined to improve patient survival [3]. We and others have shown that CD8+ T cells mediate the eradication of established tumours, providing a good basis for immunotherapeutic interventions [2, 10, 11, 20, 28, 38]. Various immunotherapeutic approaches based on immunisation with antigenic peptides have been developed and are currently being explored in individuals with cancer [4, 23, 30, 31, 35]. Local innate immunity is important in these vaccines. Various sets of adjuvants, including CpG, have been used to improve the efficacy of specific peptide-based immunotherapy [4, 30]. “Naked” nucleic acid vaccines developed nearly 20 years ago turned out to be poorly immunogenic, especially in large animals and humans [8, 9, 18]. However, these DNA or RNA constructs with “self-replicating” properties considerably improve immunological responses [7, 33, 34, 39]. These vaccines also provided the basis for the development of candidates for the treatment of patients with cancer [5, 9, 13, 14, 16]. Very few animal models are available for studying immunity to liver cancer. We recently developed a liver tumour model in which the tumour grows progressively within non-tumoural liver parenchyma [2]. This model was used to demonstrate the efficacy of curative peptide-based immunisation against specific epitopes of the SV40 T antigen, due to the induction of a strong protective CD8+ T cell specific response. A single injection of a monoepitopic SV40 T MHC class I short peptide (T404–411,H2 Kb restricted) induced a long-lasting CD8+ T cell response, liver tumour destruction and complete remission [2]. These observations are important as most immunotherapeutic methods for treating solid tumours with multiepitopic peptides derived from tumour antigens have given no more than modest clinical benefits [27].

In this study, we aimed to develop a mouse model of incomplete tumour regression based on peptide immunotherapy, closely mimicking the partial efficacy of peptide immunotherapy observed in clinical trials [27]. This model could then be used for the identification and evaluation of new combination treatments, improving clinical approaches. Using our tumour model and various SV40 T immunodominant peptides, we identified an antigenic peptide that induced high levels of CD8+ T cells, but only incomplete tumour regression. We injected MV-derived self-replicating RNA sequences (RNA replicons) into the liver parenchyma of tumour-bearing mice, to improve tumour regression in response to peptide-based immunotherapy by modifying the tumour environment. These injections strongly enhanced tumour regression, resulting in tumour eradication. Our results demonstrate the stimulatory effects of self-replicating RNA sequences on hepatic innate immunity and the contribution of these sequences to defence against liver tumours.

Materials and methods

Mice

Recipient C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Harlan (Gannat, France). The hepatocyte donors were tg C57Bl/6J mice carrying SV40 T oncogene [25]. Experiments were performed in compliance with the French Ministry of Agriculture regulations for animal experimentation.

Hepatocyte transplantation

Transformed hepatic cells were obtained from donor mice. Hepatocytes were isolated by two-step collagenase H perfusion (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) and purified by centrifugation on a 40% Percoll gradient (Amersham Biosciences, Orsay, France) [2]. SV40 T-transgenic hepatocytes (0.7 × 106) were injected into the spleens of 8 to 12-week-old normal male C57BL/6J recipient mice [2].

MV-derived sequences

The pMΔBB plasmid was obtained from pMΔN34 at Institut Pasteur (28). It contains the mengovirus (MV) genome cDNA, from which the sequences encoding polypeptide L, the structural proteins (VP1, VP2, VP3 and VP4) and part of 2A (nucleotides 737–3787) were deleted, downstream from the phage T7 promoter. This plasmid retains the cis-acting replication element (CRE) required for viral RNA replication [17] and the sequences required for optimal autocatalytic cleavage of the mengovirus polyprotein at the 2A/2B cleavage site. pMΔXBB is similar to pMΔBB, but lacks the CRE sequence. The pMΔBB-GFP, pMΔBB-NP and pMΔXBB-GFP constructs were derived from pMΔBB or pMΔXBB by in-frame insertions of cDNA sequences encoding the enhanced green fluorescent protein (GFP) and the nucleoprotein (NP) of influenza virus A/PR/8/34, respectively (Vignuzzi, Gerbaud, van der Werf and Escriou, ms in preparation). Plasmid DNA was purified from transformed E. coli DH5α cultures with the Qiagen Maxi-prep Kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Plasmids were linearised with BamH1 and DNA was transcribed in vitro with the RiboMAX™ Large Scale RNA Production System-T7 (Promega, France). Synthetic transcripts were purified and resuspended in sterile PBS. RNA was analysed qualitatively and quantitatively and stored at −80°C. Following HeLa cell transfection, rMΔBB-GFP and rMΔBB-NP RNAs were shown to be replication-competent and to produce GFP and NP, respectively, whereas rMΔXBB-GFP was not. Therefore, mengovirus-derived RNA replicons turned out to be very efficient expression vectors for recombinant proteins in vivo. Moreover, we used these vectors due to their limited capacity to induce inflammatory response compared to other viral-derived vectors such as adenoviruses. This assumption was verified in our system by assessing directly after RNA replicon injection, the level of transaminase enzymes (alanine aminotransferase, ALAT; aspartate aminotransferase, ASAT) in the sera that remained consistently under the hepatotoxic threshold (unpublished observations).

Immunisation procedures

Mice harbouring liver tumours were injected subcutaneously with SV40-T peptides (SV40-T205–215 (VSAINNYAQKL)–T205–215 or SV40-T404–411 (VVYDFLKC)–T404–411) 1 month after transplantation. We used 50 μg of SV40 T peptides combined with 50 μg of hepatitis B virus core protein HBVc128–140 T-helper epitope (TPPAYRPPNAPIL) [29] emulsified in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant for immunisation. This procedure induced long-lasting CD8+ T cell responses [constant over 1–8 weeks (data not shown)].

Intrahepatic injection of MV-derived RNA sequences

MV-derived RNAs were administered 7 days after immunisation (35 days after transplantation), as peptide-induced CD8+ T cell responses are maximal, in terms of effector cell numbers, about 10 days after immunisation. Mice were anaesthetised and 10 μg MV-derived RNA (rMΔBB-NP, rMΔBB-GFP or rMΔBB-X-GFP) in PBS was injected into the liver parenchyma. As reported in Table 1, mice were killed 16 h or 3 weeks later and the liver and spleen collected.

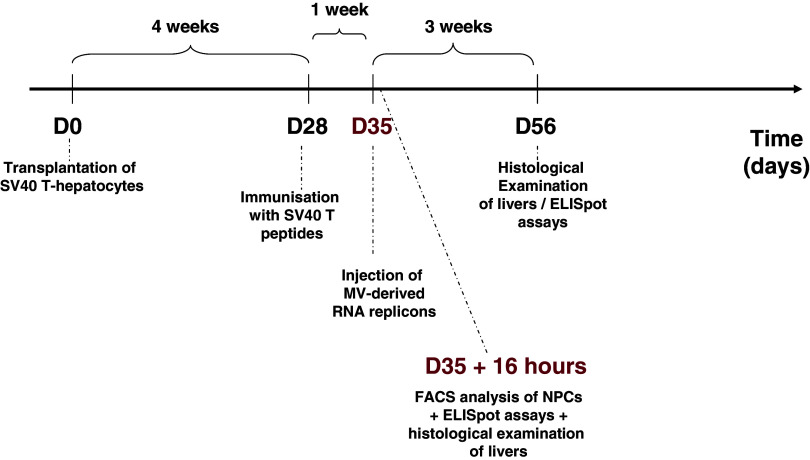

Table 1.

Diagram of experimental treatment of mice

Non-parenchymal liver cell preparation

Liver blood cells were removed by washing with HEPES buffer. The liver was homogenised in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 2% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS, JRH Biosciences), 5 mM HEPES, 2 mM glutamax (Invitrogen, Life Technologies), antibiotics and 10−5 M β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma Aldrich), and passed through a stainless steel mesh. Non-parenchymal cells (NPCs) were collected by centrifugation through two Percoll gradients and counted.

ELISpot assay

ELISpot assays were performed as previously described [2]. RMA-S cells were incubated with 10 μg mL−1 CTL epitope peptide (T205–215 or T404–411). We tested 1–5 × 105 spleen cells or NPCs in a 5:2 ratio with RMA-S cells. Capture and biotinylated anti-mouse IFN-γ rat mAbs were used as previously described (clone R4-6A2; BD Biosciences, Pharmingen). Chromogenic alkaline phosphatase substrate was added and IFN-γ spot-forming cells (SFC) were counted (expressed as number of spots per million cells).

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed on a FACScalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Cells were incubated with anti-CD16/CD32 blocker antibodies (Fcγ III/II receptor), followed by labelled antibodies or isotype-matched control immunoglobulin. Monoclonal antibodies and streptavidin (FITC-, PE- or APC-labelled) were purchased from BD Biosciences, Pharmingen: anti-CD3-FITC/CD3-PE, anti-CD4-APC, anti-CD8-APC, anti-NK1.1-PE, anti-F4/80-APC, anti-Gr1-PE, anti-CD45-FITC. CELLQuest software (BD, Biosciences) was used for data analysis.

Histological studies

Liver biopsies were immersed in fixative and embedded in paraffin. Two to six consecutive 4-μm sections were stained with haematoxylin–eosin (HE) and tumour nodules were then counted under a microscope.

Results

Immunisation with MHC class I peptide SV40-T205–215 leads to incomplete liver tumour regression

When evaluating the efficacy of tumour peptide-based immunotherapy, we screened several immunodominant SV40 T MHC class I peptides and found that immunisation with the unique SV40 T peptide, T404–411, led to complete tumour regression [2]. The partial tumour regression obtained with other peptides resembles that observed in clinical trials. Among the four epitopes of SV40 T, three of them are codominant such as T205–215 and T223–231 which are H2 Db restricted whereas T404–411 is H2 Kb restricted. Moreover, a recessive H2 Db-restricted epitope T489–497 has also been described. In our previous study, we documented the hierarchy of SV40 T peptide specific IFNγ-producing CD8+ T cell responses [2]. Thus, the responses obtained with T223–231 and T488–497 were far below the responses obtained with the codominants T205–215 and T404–411 inducing partial and complete tumour regression, respectively. These low responses were related to a specific tolerance against the dominant T223–231 and a recessive response towards T488–497 peptide [2, 26].

Therefore, we looked for a non-tolerated peptide-specific response in tumour-bearing mice, and assessed tumour regression.

We compared specific IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cell responses and tumour regression in tumour-bearing mice immunised with T205–215 or T404–411 peptides. We carried out ELISpot assays and histological examination 2 months after the transplantation of transformed SV40 T tg hepatocytes.

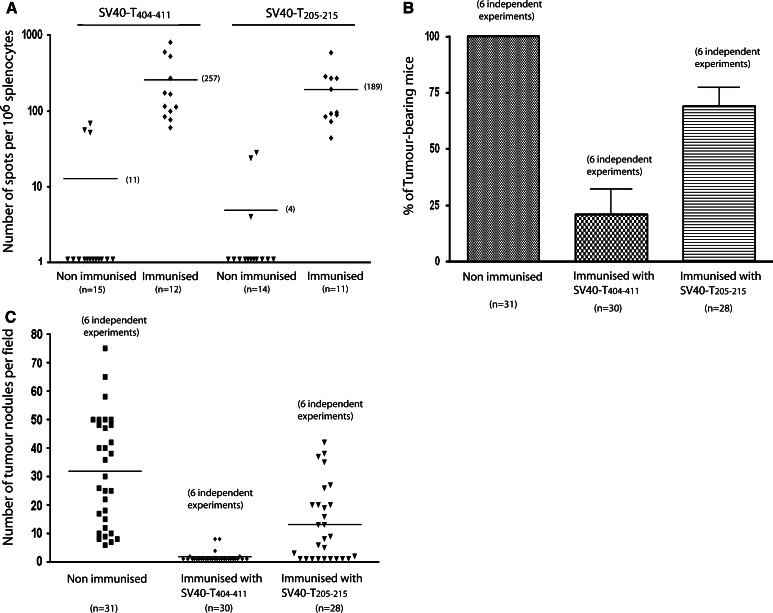

Similar numbers of activated specific CD8+ splenic T cells were obtained with the T404–411 and T205–215 peptides (257 and 189 SFCs per 1 × 106 splenocytes, respectively; Fig. 1A) 1 and 2 months after immunisation. The CD8+ T cell response was extremely weak in non-immunised tumour-bearing mice (11 and 4 SFCs per 1 × 106 splenocytes for both peptides), as previously observed [2]. SFC numbers were distributed heterogeneously, despite the large numbers of mice in each group (11–15 mice).

Fig. 1.

Immunisation of SV40-T liver tumour-bearing mice with SV40-T205–215 peptide induces a specific CD8+ T cell response but is consistently associated with partial tumour regression. C57BL/6J mice were immunised with T404–411 (n = 12) or T205–215 (n = 11) 1 month after the transplantation of 0.7 × 106 SV40-T transgenic hepatocytes, and analysed 2 months after transplantation. A Evaluation of SV40-T-specific CD8+ T cell responses by ELISpot assays of splenocytes from transplanted mice after immunisation with T404–411 or T205–215. B Percentage of liver tumour-bearing mice evaluated by histology for mice immunised with T404–411 (n = 30) versus non-immunised mice (control group, n = 31) (Mann and Whitney U test P < 0.01), and of mice immunised with T205–215 (n = 28) versus non-immunized mice (Mann and Whitney U test P < 0.01). C Number of tumour nodules per field, observed at a final magnification of ×125. Comparison of mice immunised with T404–411 (n = 30) and control mice (n = 31) (Mann and Whitney U test P < 0.01), and of mice immunised with T205–215 (n = 28) and control mice (Mann and Whitney U test P < 0.01). The data shown in panels B and C are representative of six independent experiments

Immunisation with T404–411 eradicated tumours in 25 of 30 immunised mice, within 4 weeks after immunisation (Fig. 1B, C). The remaining five mice had fewer than ten persisting tumour nodules. The nodules were small (less than 15 cells) and associated with leukocyte infiltrates, indicative of ongoing tumour regression. In sharp contrast, the immunisation of mice (n = 28) with T205–215 led to only partial tumour regression (32% of mice were tumour-free after treatment). Tumours persisted in 19 mice, 68% of which had large numbers (>13) of large tumour nodules. Similar observations were obtained 10 weeks after immunisation (data not shown).

We conclude that the immunisation of liver tumour-bearing mice with T205–215 consistently led to partial tumour regression. The suboptimal conditions of tumour regression induced by peptide-based vaccination are similar to those observed in cancer patients and may be relevant for evaluating the effects of combined therapeutic approaches [27].

Intrahepatic administration of MV-derived RNA replicons substantially improves the liver tumour regression induced by peptide-based immunotherapy

We investigated the effect on peptide-mediated tumour regression of modifying the tumour environment by injecting MV-derived RNAs locally into the liver parenchyma of tumour-bearing mice (T205–215-immunised mice). We used self-replicating RNA sequences, which have been reported to improve vaccine potency [36], to share with mengovirus from which they are derived, a broad host range and tissue tropism [24], and finally to bypass hazardous DNA integration.

Tumour regression was evaluated 2 months after hepatocyte transplantation and 3 weeks after the intrahepatic injection of 10 μg of self-replicating rMΔBB-NP RNA, by counting tumour nodules within the liver parenchyma. T205–215-immunised mice injected with PBS had liver tumour nodules (mean of 18 nodules per liver section, Fig. 2). In contrast, no persistent tumour foci were detected in mice injected with rMΔBB-NP RNA, with the exception of one mouse in which a single, small tumour nodule was associated with mild leukocyte infiltration. Similar degrees of tumour regression were observed with rMΔBB-NP and rMΔBB-GFP replicons (data not shown). However, injection of RNA-replicons to non-immunised tumor-bearing mice failed to induce tumor regression (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Intrahepatic injection of MV-derived RNA replicons efficiently converts partial tumour regression in response to peptide-based immunotherapy into complete tumour eradication. One month after transplantation with 0.7 × 106 SV40-T transgenic hepatocytes, C57BL/6J mice were immunised with T205–215 or T404–411 or left unimmunised (control). One week after peptide injection, PBS (control) or RNA replicons (rMΔBB-GFP or rMΔBB-NP, 10 μg) were injected into the liver parenchyma of tumour-bearing mice. Three other groups of immunised mice were investigated: mice injected with the non-replicating (r-MΔXBB-GFP) RNA replicon (10 μg), mice injected with CpG ODN 1668 (10 μg), and mice injected with concanavalin A (2 μg). Mice were killed 3 weeks later and histological analyses of the liver were carried out. Panel A: Number of tumour nodules per liver section for the various groups of mice. Panel B: Histological analysis of liver parenchyma at a magnification of ×100. a Non-immunised + PBS, b immunized + PBS, c immunized + rMΔBB-GFP or rMΔBB-NP (10 μg), c′ immunized + rMΔBB-GFP or rMΔBB-NP (10 μg) at ×300 magnification, d immunized + non-replicating (rMΔXBB-GFP) RNA replicon (10 μg), e immunised + CpG 1668 (10 μg), f immunised + concanavalin A (2 μg), g immunised with T404–411 + PBS, g′ immunised with T404–411 + PBS at ×300 magnification

We investigated whether MV-derived RNA replication was required for tumour regression. Local injections of non-replicating rMΔXBB-GFP RNA into liver tumour-bearing mice immunised with T205–215 gave no more substantial tumour regression than observed in PBS controls (15 ± 16 nodules per liver section in immunised mice injected with rMΔXBB-GFP and 19 ± 15 in PBS controls; Fig. 2). Small groups of mice injected with CpG DNA or ConA—known inducers of liver inflammation—had fewer nodules per liver section than PBS-injected mice (Fig. 2) but did not attain the tumour regression score of the group injected with the RNA replicon. Thus, the intrahepatic delivery of MV-derived RNA replicons significantly improved peripheral peptide-based immunotherapy in terms of tumour regression. This was related to the intrinsic properties of the RNA sequences, including the ability to replicate. Moreover, we analysed GFP production in liver cells 6, 12, 16, 24 and 48 h after RNA injection. There was no GFP fluorescence in livers injected with non-replicating rMΔXBB-GFP RNAs, but GFP fluorescence was present in a few liver cells as soon as 12 h after injection of replicating rMΔBB-GFP RNA and lasted up to 48 h after injection. GFP production 16 h after injection was restricted to large cells that may be hepatocytes. GFP was still present in hepatocytes 48 h after injection, but was associated with clusters of fuzzy granulations randomly dispersed within the liver parenchyma. These observations were too scarce so that we could not evaluate quantitatively the number of GFP positive cells (data not shown).

Altogether, these findings suggest that intrahepatic targeting of MV-derived RNA replicons creates a favourable inflammatory environment, leading to liver tumour eradication in mice immunised with tumour antigen.

Intrahepatic delivery of MV-derived RNA replicons did not modify the frequency and function of hepatic CD8+ T cells

We previously showed that tumour regression and the number of peptide-specific CD8+ T cells in the liver are correlated [2]. We therefore investigated the mechanism by which RNA replicons induce their effects on tumour regression by analysing the effects of injecting MV-derived RNA replicons into the liver parenchyma of tumour-bearing mice on the number or function of T205–215 peptide-specific CD8+ T cells.

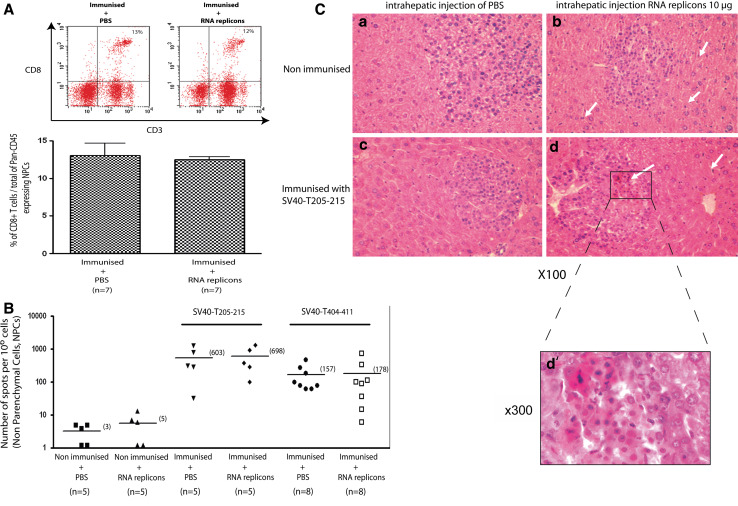

Tumour-bearing mice were injected with 10 μg MV-derived RNA or PBS. Hepatic CD8+ T cells were analysed by FACS analysis 16 h later. Local rMΔBB-NP RNA injection did not affect the proportion of CD8+ T cells in the CD45+ non-parenchymal cell subset (12 ± 0.9 and 13 ± 4.3% for immunised mice injected with replicon and PBS, respectively; Fig. 3A). We therefore used a functional IFN-γ-specific ELISpot assay to assess the frequency of T205–215-specific CD8+ T cells in the liver 16 h after the injection of rMΔBB-NP RNA. The frequencies of IFN-γ-secreting T205–215-specific CD8+ T cells within the liver were similar in immunised mice injected with rMΔBB-NP RNA and PBS (698 and 603 spots per 1 × 106 NPCs respectively; Fig. 3B). Frequencies were also similar between T404–411 peptide-immunised mice injected with rMΔBB-NP RNA and PBS (178 and 157 spots per 1 × 106 NPCs, respectively). The T205–215-specific CD8+ T cell response was unaffected 36 weeks after the injection of MV-derived RNA (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

The intrahepatic injection of MV-derived RNA replicons did not affect the percentage of CD8 (+) T cells among Pan-CD45-expressing liver NPCs or the number of T205–215-specific CD8 (+) T cells producing IFN-γ. Tumour-bearing mice were immunised with T205–215 and PBS or rMΔBB-NP (10 μg) was injected into their liver parenchyma 7 days later. Mice were killed 16 h later and NPCs were extracted from the liver. A The percentage of CD8+ T cells among pan-CD45+ NPCs was evaluated by flow cytometry, using specific antibodies from immunised mice injected with PBS (13%) or 10 μg of rMΔBB-NP (12%). B Local T205–215- and T404–411-specific CD8+ T cell responses were assessed by IFN-γ-specific ELISpot assays in tumour-bearing non-immunised mice, and immunised mice (T205–215 or T404–411) injected with PBS or 10 μg of rMΔBB-NP. These data are representative of four independent experiments. C Histological evaluation of liver sections from non-immunised mice and mice immunised with T205–215 after injection of PBS or rMΔBB-NP into liver parenchyma. a: Non-immunised mice injected with PBS, b: Non-immunised mice injected with 10 μg of rMΔBB-NP, c: Mice immunised with T205–215 and injected with PBS, d: Mice immunised with T205–215 and injected with 10 μg of rMΔBB-NP. White arrows show leukocytes within tumour nodules or liver sinusoids. Magnification ×100. The data shown in C are representative of three independent experiments (n = 6 mice)

Thus, the intrahepatic injection of an MV-derived replicon did not affect the size of the hepatic total or epitope-specific CD8+ T cell populations.

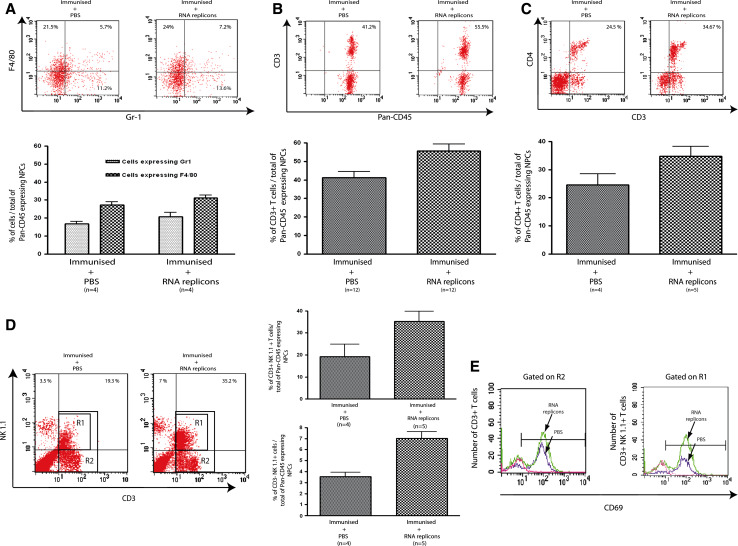

Intrahepatic delivery of MV-derived RNA replicons resulted in larger populations of hepatic activated NK and NKT innate immune cells

We extended our analysis to other non-parenchymal cells. Histological examination of livers injected with MV-derived RNA replicons (10 μg rMΔBB-NP) suggested a slight increase in the number of immune cells patrolling hepatic sinusoids and low levels of cell infiltration in most tumour nodules in immunised mice (Fig. 3C). This infiltration was supposedly associated to hepatocyte cell death, as indicated by the pinkish colour of hepatocytes (Fig. 3C). However, it was not possible to quantify accurately the number of tumour nodules infiltrated with liver leukocytes. Therefore, we decided to evaluate any modifications in the number of NPCs sub-populations. We characterised these non-parenchymal cell populations by FACS analysis 16 h after intrahepatic injection. The percentages of non-parenchymal cells that were Gr1+ (granulocytes) and F4/80+ (macrophages/Kupffer cells) were not significantly different in mice receiving rMΔBB-NP RNA (20.8 ± 5% Gr1+ and 31.2 ± 3% F4/80+) and PBS (16.8 ± 3.5% Gr1+ and 27.2 ± 3.5% F4/80+; Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Intrahepatic injection of MV-derived RNA replicons rapidly increases the size of innate CD3 (−) NK hepatic cell and NK1.1 (+) CD3 (+) NKT populations. Tumour-bearing mice were immunised with T205–215 and PBS or rMΔBB-NP (10 μg) was injected into liver parenchyma 7 days later. Mice were killed 16 h later and NPCs were extracted from the liver. A Percentage of pan-CD45+ NPCs expressing Gr1 (mostly granulocytes) and F4/80 (mono/macrophages/Kupffer cells) in the two groups of mice. B Percentage of CD45+ NPCs that were CD3+ in the two groups. C Percentage of CD45+ NPCs corresponding to CD4+ T cells in the two groups. D Percentage of CD45+ NPCs corresponding to CD3+ NK1.1+ T cells (mostly NKT) and CD3− NK1.1+ cells (NK) in the two groups. E Evaluation of CD69 cell surface expression on total CD3+ T cells (gated on R2, see d) and CD3+ NK1.1+ T cells (gated on R1, see D). Mann and Whitney U test P < 0.01. These data are representative of four independent experiments

However, the CD3− NK1.1+ cell population (natural killer cells) was significantly larger in mice injected with RNA replicon (7 ± 1.2%) than in mice injected with PBS (3.5 ± 0.8%, Mann and Whitney U test P < 0.05; Fig. 4D). Similarly, the CD45+ NPC population contained larger proportions of CD3+ and CD4+ T cells in the rMΔBB-NP RNA group (55.5 ± 13.4% CD3+ and 34.7 ± 7.9% CD4+) than in the PBS group (41.2 ± 10.95% CD3+ and 24.5 ± 7.9% CD4+; Fig. 4B, C). Although small, this difference in the size of the CD3+ T cell population was significant (Mann and Whitney U test P < 0.05). Most liver CD4+ T cells are NKT cells. We therefore compared the percentage of CD3+NK1.1+ NKTs within the CD45+ NPC population in livers injected with RNA replicon and PBS. This percentage was significantly higher in the livers of rMΔBB-NP RNA-injected mice (35.2 ± 9.1%) than in PBS-injected mice (19.3 ± 9.75%) (Mann and Whitney U test P < 0.05; Fig. 4D). Most CD3+NK1.1+ NKT cells displayed the CD69 activation marker and the activated population was larger in mice receiving rMΔBB-NP RNA (Fig. 4E).

Thus, the intrahepatic delivery of rMΔBB-NP RNA did not affect the peptide-induced recruitment of specific and non-specific CD8+ T cells in the liver, but increased the size of the innate immune cell population, including activated NK and NKT cells, patrolling liver sinusoids.

Discussion

In this study, we immunised mice with the codominant SV40 T205–215 peptide, resulting in partial tumour regression. Immunisation with the dominant T404–411 peptide has been shown to lead to full tumour regression that correlated with the number of peptide-specific IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells in liver [2]. Partial responses are more frequently observed in clinical trials [27]. These differences in tumour regression were not attributed to differences in CD8+ T cell responses in the spleen or liver. Manipulation of the stromal microenvironment of established tumours has been shown to improve immune recognition and tumour regression [12, 15, 22, 37]. We aimed to improve tumour regression in mice immunised with the SV40 tumour antigen, using “danger signals” delivered by local injection of a non-hepatotoxic amount of MV-derived RNA replicons to modify the tumour environment. We used self-replicating RNA sequences, which have been reported to increase vaccine potency [36] from mengovirus, which has a broad host range and tissue tropism [24]. We deleted viral structural genes from the constructs, to ensure that no infectious virus was produced, thereby limiting host immune responses to the vector. The mengovirus replicon replicated within the liver after the delivery of naked RNA, as GFP was produced from rMΔBB-GFP RNA in a few large liver cells. These cells were hepatocytes (data not shown), but other non-parenchymal cell subsets probably also harbour these RNA replicons.

The injection of replication-competent rMΔBB-GFP or rMΔBB-NP RNA replicons into the livers of T205–215-immunised mice converted partial tumour regression into tumour eradication. The intrinsic properties of the RNA sequences, including their ability to replicate, were responsible for this effect. Tumour nodule counts in the non-injected lobe of tumoural livers showed that the effects of RNA replicons were not restricted to the site of injection, but extended to the whole liver. Moreover, we consistently found tumour eradication after the injection of RNA replicons to immunised tumor-bearing animals whereas non-immunised RNA replicons injected mice did not regress their tumours (data not shown). These findings suggest that RNA replicons are promising tools for improving peptide-based immunotherapy.

We investigated the mechanisms by which RNA replicons provoked tumour eradication, by studying the local tumour-specific CD8+ T cell response after intrahepatic RNA replicons injection. We studied tumour-specific CD8+ T cell response since in this tumour model, we previously found that tumour regression correlated with the number of epitope-specific CD8+ T cells that functionally produced IFN-γ [2]. Moreover, we showed that targeted expression of IFN-γ, using adenoviral vector, into the liver induced a potent tumour regression [1].

Surprisingly, we found no significant changes in specific CD8+ T cell number or function in the spleen and liver 16 h or 3 weeks after local injection of RNA replicons.

Based on our previous observations, we knew that tolerogenic pathways were not involved in this tumour model since antibody treatments either with CD25 depletion or TGFβ neutralisation did not lead to any modification of either IFNγ-producing CD8+ T cells response or tumour progression [2].

However, we cannot exclude the possibility that other changes—in patrolling rate within the liver parenchyma and tumour nodules or cytokine and adhesion molecule profile, for example—occurred.

Intrahepatic injection of MV-derived RNA replicons induced intrahepatic immune cell recruitment, with a doubling of the NK cell population (from 3.5 to 7%) associated with a modest increase in the size of the total CD3+ T cell population. The hepatic NKT cell population also doubled in size (from 19 to 35%). This major liver lymphocyte population of the liver is known to be involved in anti-tumoural processes [6, 32]. Most of these cells expressed the CD69 activation marker, suggesting that activated NKT cells were recruited upon intrahepatic replication of the MV-derived RNA. Intrahepatic RNA replicon injection rapidly affected immune cell-mediated hepatic cytotoxicity, as cell infiltrates were observed in most tumour nodules within 16 h of injection. The intrahepatic injection of non-hepatotoxic doses of ConA into immunised mice also gave significantly higher levels of tumour destruction than PBS injection. Our results confirm that a low, non-hepatotoxic dose of ConA stimulates innate immune cells (NK/NKT), inducing an anti-tumour effect against metastatic liver tumours [19].

Our data suggest that the intrahepatic injection of MV-derived RNA replicons modifies the distribution of liver NK/NKT cells. Interestingly, the increase of NKT cells was maintained during the all course of remission in the groups of treated mice i.e., T404–411 and T205–215 plus MV-derived replicons, as assessed 3 weeks after injection of MV-derived replicons (data not shown). Whereas, we did not find any persistence of NK cell increase at that time, the proportion of liver NKTs assessed 3 weeks after the injection of MV-derived replicons was lower than the one at 16 h (Fig. 4D). However, the proportion of liver NKTs in these animals was found consistently higher (30% increase) than non treated-, T205–215 immunised-, replicon-injected tumour-bearing mice (data not shown).

The presence of these effectors might contribute in association with specific CD8+ T cells, to modify tumour microenvironment and thus implementing tumour eradication established under our immunisation protocol.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate that the introduction of MV-derived RNA replicons into tumoural liver parenchyma can create an environment favouring tumour eradication rather than partial tumour regression in mice. They suggest that the partial efficacy of peptide immunotherapy in clinical trials could also be improved by new combination therapies modifying the liver tumour microenvironment. RNA replicons engineered to favour immune cell activation or recruitment by tumour antigen, cytokine or chemokine expression may therefore be a useful tool for improving liver cancer immunotherapy meriting further evaluation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from Comité de Paris de La Ligue Contre le Cancer (75/2-LA/11) and from Axe 3 du Cancéropole Ile De France.

Abbreviations

- rMΔBB-GFP

Mengovirus-derived RNA replicons expressing GFP or NP (rMΔBB-NP)

Footnotes

Jean-Pierre Couty and Anne-Marie Crain contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Baratin M, Ziol M, Romieu R, Kayibanda M, Gouilleux F, Briand P, Leroy P, Haddada H, Renia L, Viguier M, Guillet JG. Regression of primary hepatocarcinoma in cancer-prone transgenic mice by local interferon-gamma delivery is associated with macrophages recruitment and nitric oxide production. Cancer Gene Ther. 2001;8:193–202. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belnoue E, Guettier C, Kayibanda M, Le Rond S, Crain-Denoyelle AM, Marchiol C, Ziol M, Fradelizi D, Renia L, Viguier M. Regression of established liver tumor induced by monoepitopic peptide-based immunotherapy. J Immunol. 2004;173:4882–4888. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.8.4882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiriva-Internati M, Grizzi F, Jumper CA, Cobos E, Hermonat PL, Frezza EE. Immunological treatment of liver tumors. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:6571–6576. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i42.6571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cornet S, Menez-Jamet J, Lemonnier F, Kosmatopoulos K, Miconnet I. CpG oligodeoxynucleotides activate dendritic cells in vivo and induce a functional and protective vaccine immunity against a TERT derived modified cryptic MHC class I-restricted epitope. Vaccine. 2006;24:1880–1888. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crettaz J, Berraondo P, Mauleon I, Ochoa L, Shankar V, Barajas M, van Rooijen N, Kochanek S, Qian C, Prieto J, et al. Intrahepatic injection of adenovirus reduces inflammation and increases gene transfer and therapeutic effect in mice. Hepatology. 2006;44:623–632. doi: 10.1002/hep.21292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crowe NY, Coquet JM, Berzins SP, Kyparissoudis K, Keating R, Pellicci DG, Hayakawa Y, Godfrey DI, Smyth MJ. Differential antitumor immunity mediated by NKT cell subsets in vivo. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1279–1288. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalemans W, Delers A, Delmelle C, Denamur F, Meykens R, Thiriart C, Veenstra S, Francotte M, Bruck C, Cohen J. Protection against homologous influenza challenge by genetic immunization with SFV-RNA encoding Flu-HA. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995;772:255–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb44752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donnelly JJ, Friedman A, Ulmer JB, Liu MA. Further protection against antigenic drift of influenza virus in a ferret model by DNA vaccination. Vaccine. 1997;15:865–868. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(96)00268-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donnelly JJ, Ulmer JB, Liu MA. DNA vaccines. Dev Biol Stand. 1998;95:43–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dudley ME, Rosenberg SA. Adoptive-cell-transfer therapy for the treatment of patients with cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:666–675. doi: 10.1038/nrc1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Shelton TE, Even J, Rosenberg SA. Generation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte cultures for use in adoptive transfer therapy for melanoma patients. J Immunother. 2003;26:332–342. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200307000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garbi N, Arnold B, Gordon S, Hammerling GJ, Ganss R. CpG motifs as proinflammatory factors render autochthonous tumors permissive for infiltration and destruction. J Immunol. 2004;172:5861–5869. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.5861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gurunathan S, Irvine KR, Wu CY, Cohen JI, Thomas E, Prussin C, Restifo NP, Seder RA. CD40 ligand/trimer DNA enhances both humoral and cellular immune responses and induces protective immunity to infectious and tumor challenge. J Immunol. 1998;161:4563–4571. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Irvine KR, Rao JB, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Cytokine enhancement of DNA immunization leads to effective treatment of established pulmonary metastases. J Immunol. 1996;156:238–245. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawarada Y, Ganss R, Garbi N, Sacher T, Arnold B, Hammerling GJ. NK- and CD8 (+) T cell-mediated eradication of established tumors by peritumoral injection of CpG-containing oligodeoxynucleotides. J Immunol. 2001;167:5247–5253. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.5247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laddy DJ, Weiner DB. From plasmids to protection: a review of DNA vaccines against infectious diseases. Int Rev Immunol. 2006;25:99–123. doi: 10.1080/08830180600785827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lobert PE, Escriou N, Ruelle J, Michiels T. A coding RNA sequence acts as a replication signal in cardioviruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11560–11565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martinon F, Krishnan S, Lenzen G, Magne R, Gomard E, Guillet JG, Levy JP, Meulien P. Induction of virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in vivo by liposome-entrapped mRNA. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:1719–1722. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miyagi T, Takehara T, Tatsumi T, Suzuki T, Jinushi M, Kanazawa Y, Hiramatsu N, Kanto T, Tsuji S, Hori M, Hayashi N. Concanavalin a injection activates intrahepatic innate immune cells to provoke an antitumor effect in murine liver. Hepatology. 2004;40:1190–1196. doi: 10.1002/hep.20447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Monsurro V, Nagorsen D, Wang E, Provenzano M, Dudley ME, Rosenberg SA, Marincola FM. Functional heterogeneity of vaccine-induced CD8 (+) T cells. J Immunol. 2002;168:5933–5942. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Motola-Kuba D, Zamora-Valdes D, Uribe M, Mendez-Sanchez N. Hepatocellular carcinoma. An overview. Ann Hepatol. 2006;5:16–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mueller MM, Fusenig NE. Friends or foes–bipolar effects of the tumour stroma in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:839–849. doi: 10.1038/nrc1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohshita A, Yamaguchi Y, Minami K, Okita R, Toge T. Generation of tumor-reactive effector lymphocytes using tumor RNA-introduced dendritic cells in gastric cancer patients. Int J Oncol. 2006;28:1163–1171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osorio JE, Hubbard GB, Soike KF, Girard M, van der Werf S, Moulin JC, Palmenberg AC. Protection of non-murine mammals against encephalomyocarditis virus using a genetically engineered Mengo virus. Vaccine. 1996;14:155–161. doi: 10.1016/0264-410X(95)00129-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Romieu R, Baratin M, Kayibanda M, Guillet JG, Viguier M. IFN-gamma-secreting Th cells regulate both the frequency and avidity of epitope-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes induced by peptide immunization: an ex vivo analysis. Int Immunol. 1998;10:1273–1279. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.9.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Romieu R, Baratin M, Kayibanda M, Lacabanne V, Ziol M, Guillet JG, Viguier M. Passive but not active CD8+ T cell-based immunotherapy interferes with liver tumor progression in a transgenic mouse model. J Immunol. 1998;161:5133–5137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Restifo NP. Cancer immunotherapy: moving beyond current vaccines. Nat Med. 2004;10:909–915. doi: 10.1038/nm1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schell TD, Tevethia SS. Control of advanced choroid plexus tumors in SV40 T antigen transgenic mice following priming of donor CD8 (+) T lymphocytes by the endogenous tumor antigen. J Immunol. 2001;167:6947–6956. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.12.6947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sette A, Vitiello A, Reherman B, Fowler P, Nayersina R, Kast WM, Melief CJ, Oseroff C, Yuan L, Ruppert J, et al. The relationship between class I binding affinity and immunogenicity of potential cytotoxic T cell epitopes. J Immunol. 1994;153:5586–5592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Speiser DE, Lienard D, Rufer N, Rubio-Godoy V, Rimoldi D, Lejeune F, Krieg AM, Cerottini JC, Romero P. Rapid and strong human CD8+ T cell responses to vaccination with peptide, IFA, and CpG oligodeoxynucleotide 7909. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:739–746. doi: 10.1172/JCI23373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tagawa ST, Cheung E, Banta W, Gee C, Weber JS. Survival analysis after resection of metastatic disease followed by peptide vaccines in patients with stage IV melanoma. Cancer. 2006;106:1353–1357. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Terabe M, Swann J, Ambrosino E, Sinha P, Takaku S, Hayakawa Y, Godfrey DI, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Smyth MJ, Berzofsky JA. A nonclassical non-Valpha14Jalpha18 CD1d-restricted (type II) NKT cell is sufficient for down-regulation of tumor immunosurveillance. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1627–1633. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ulmer JB, Wahren B, Liu MA. Gene-based vaccines: recent technical and clinical advances. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12:216–222. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vignuzzi M, Gerbaud S, van der Werf S, Escriou N. Naked RNA immunization with replicons derived from poliovirus and Semliki Forest virus genomes for the generation of a cytotoxic T cell response against the influenza A virus nucleoprotein. J Gen Virol. 2001;82:1737–1747. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-7-1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu S, Wang SQ, Zhang J, Tan XY, Liu JN. Native anti-tumor responses elicited by immunization with a low dose of unmodified live tumor cells. Int J Oncol. 2006;28:731–736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ying H, Zaks TZ, Wang RF, Irvine KR, Kammula US, Marincola FM, Leitner WW, Restifo NP. Cancer therapy using a self-replicating RNA vaccine. Nat Med. 1999;5:823–827. doi: 10.1038/10548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu P, Lee Y, Liu W, Chin RK, Wang J, Wang Y, Schietinger A, Philip M, Schreiber H, Fu YX. Priming of naive T cells inside tumors leads to eradication of established tumors. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:141–149. doi: 10.1038/ni1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou J, Dudley ME, Rosenberg SA, Robbins PF. Selective growth, in vitro and in vivo, of individual T cell clones from tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes obtained from patients with melanoma. J Immunol. 2004;173:7622–7629. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou X, Berglund P, Rhodes G, Parker SE, Jondal M, Liljestrom P. Self-replicating Semliki Forest virus RNA as recombinant vaccine. Vaccine. 1994;12:1510–1514. doi: 10.1016/0264-410X(94)90074-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]