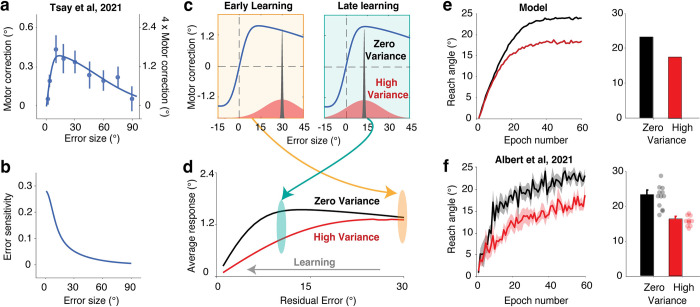

Fig 1. A non-linear motor correction function is sufficient to explain the effect of perturbation variability.

| a) Changes in reach angle from trial n to n + 1 as a function of the error size on trial n in Tsay et al. (2021) [20]. Dots represent group median values for each error size and bars represent the standard error of the means. We used these data to estimate the motor correction function given the relatively high sampling density. Solid line denotes the best-fitting model. The y-axis is double labeled: The left side uses the original scale from [20] whereas the scale is increased by 4-fold on the right side. We use the right-side scale in our simulations of published data to provide a match with the baseline learning rate reported in Albert et al. (2021) [11]. We note that the learning function in [20] was likely attenuated due to the methods employed in that study (see Method: Model Simulations). b) Error sensitivity, defined as the motor correction divided by error size, reduces monotonically as error size increases. c) Perturbation variability impacts the distribution of experienced errors (red, high variability; black, low variability). This in turn will dictate the distribution of motor corrections. d) When the error is large at the start of learning (e.g., ~30°), the average response is similar between the low- and high-variance conditions. However, as learning unfolds, the error distribution for the high-variance condition will span the concave region of the motor correction function (e.g., ~10°), resulting in attenuation of the average motor correction. e-f) The learning function of implicit adaptation predicted by the non-linear motor correction (NLMC) model (e) provides a good approximation of the empirical results from Experiment 6 of Albert et al. (2021) [11]. (f). The right panels for each row show the reach angle late in learning. For Albert et al. (2021) [11], shaded areas (left) and error bars (right) indicate standard error, and dots indicate data for each individual.