Abstract

Background:

Black and Latino communities have been disproportionately impacted by COVID-19 and we sought to understand perceptions and attitudes in four heavily impacted NJ counties to develop and evaluate engagement strategies to enhance access to testing.

Objective:

To establish a successful academic/community partnership team during a public health emergency by building upon longstanding relationships and using principles from community engaged research.

Methods:

We present a case study illustrating multiple levels of engagement, showing how we successfully aligned expectations, developed a commitment of cooperation, and implemented a research study, with community-based and healthcare organizations at the center of community engagement and recruitment.

Lessons Learned:

This paper describes successful approaches to relationship building including information sharing and feedback to foster reciprocity, diverse dissemination strategies to enhance engagement, and intergenerational interaction to ensure sustainability.

Conclusions:

This model demonstrates how academic/community partnerships can work together during public health emergencies to develop sustainable relationships.

Keywords: Community health partnerships, Health promotion, Community-Based Participatory Research, Substance-Related Disorders, Public Health, Urban Population, Vulnerable Populations

BACKGROUND

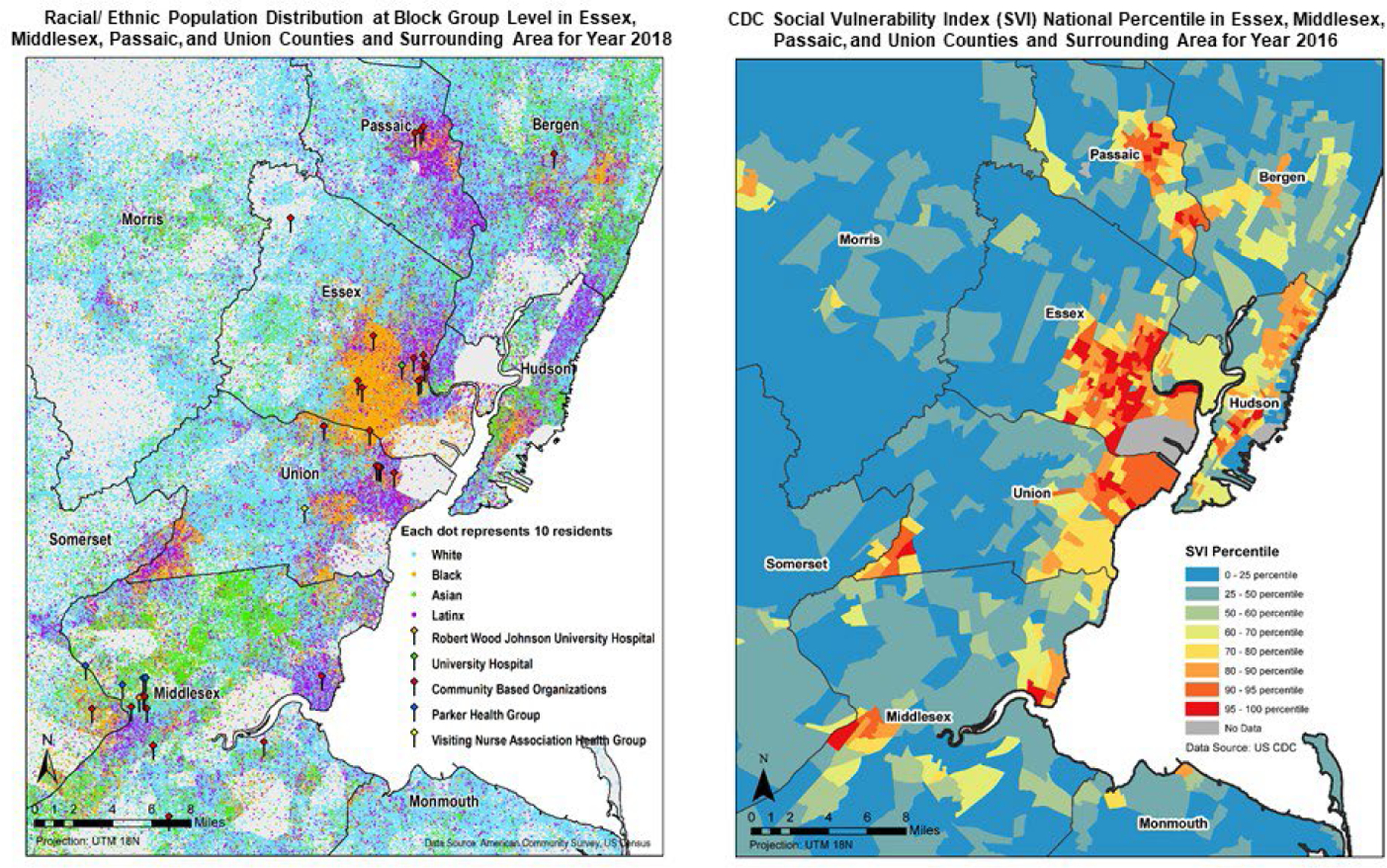

Throughout the U.S., coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has had disproportionate effects on Black and Latino communities.1–3 In 2020, New Jersey had a population of 9.3 million people and the second greatest U.S. population density after the District of Columbia with 1,263 people per square mile.4 New Jersey experienced its first wave of COVID-19 cases early in the pandemic5 and as of November 2021 ranked third in per capita rate of COVID-19 deaths.6 As in other parts of the US, in NJ there was substantial overlap between COVID-19 cases, poverty, and Black and Latino communities (see Figure 1). Although the deaths occurred disproportionately in Black and Latino communities, access to testing was difficult, and vaccine skepticism was growing among these communities. 2, 7–11 Reports of swift development of COVID-19 vaccines, conflicting information and misinformation about COVID-19, social justice unrest, and a volatile political climate reawakened distrust.12

Figure 1.

Maps of NJ HEROES TOO participating counties racial/ethnic density, poverty and coverage of HCO and CBO partners (as of July 2020, the time of grant submission)

The left map shows the racial/ethnic density and location(s) of CBO and HCO partners in the four NJ counties (Essex, Middlesex, Passaic and Union) which had at that time the highest rates of COVID-19 in NJ. This map was generated using 2018 data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey. The data represents population distribution at the Block Group Level.

Each dot on the map represents 10 residents and is color-coded to race/ethnicity.

The blue dots represent people who are white

The orange dots represent people who are black

The green dots represent people who are Asian

The purple dots represent people who are Latinx

Community partner organizations are represented by red pins and the health care organizations are represented by the other colored pins.

The right map shows CDC’s Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) for 2016 in the four NJ counties (Essex, Middlesex, Passaic and Union) which had in July 2020 the highest rates of COVID-19 in NJ. The SVI uses U.S. Census data to determine the social vulnerability of each census tract for which the Census collects data. The CDC SVI ranks each tract on 15 social factors including poverty, lack of access to transportation, and crowded housing. These factors are considered the ones that weaken a community’s ability to prevent human suffering and financial loss during a disaster such as natural disasters (e.g., tornado), human-made events (e.g., chemical spill), or disease outbreaks, such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

The map is color coded for the SVI percentile.

Census tracts in the 0–25 percentile are blue

Census tracts in the 25–50 percentile are dark green

Census tracts in the 50–60 percentile are light green

Census tracts in the 60–70 percentile are greenish yellow

Census tracts in the 70–80 percentile are light orange

Census tracts in the 80–90 percentile are orange

Census tracts in the 90–95 percentile are red orange

Census tracts in the 95–100 percentile are red

Census tracts without data are grey

COVID-19 presents a complex population health challenge that is complicated by social justice issues such as health inequities and disparities, and distrust of research.13–15 Academic institutions have been challenged to employ community-engaged approaches to help address these issues. For example, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics - Underserved Populations (RADx-UP) promoted collaborative research and interventions as optimal strategies to engage communities in alleviating barriers to COVID-19 testing.16 Over the past few decades, multiple models have been developed and used to promote health equity,17 including community-based participatory research (CBPR),18 participatory action research,19 research practice partnerships,20 community partnered participatory research,21 community-academic partnerships,22 participatory team science,23 and community-engaged research promoted by the NIH.24 Each of these models has made a substantial contribution to the science of community-engaged research and intervention development.

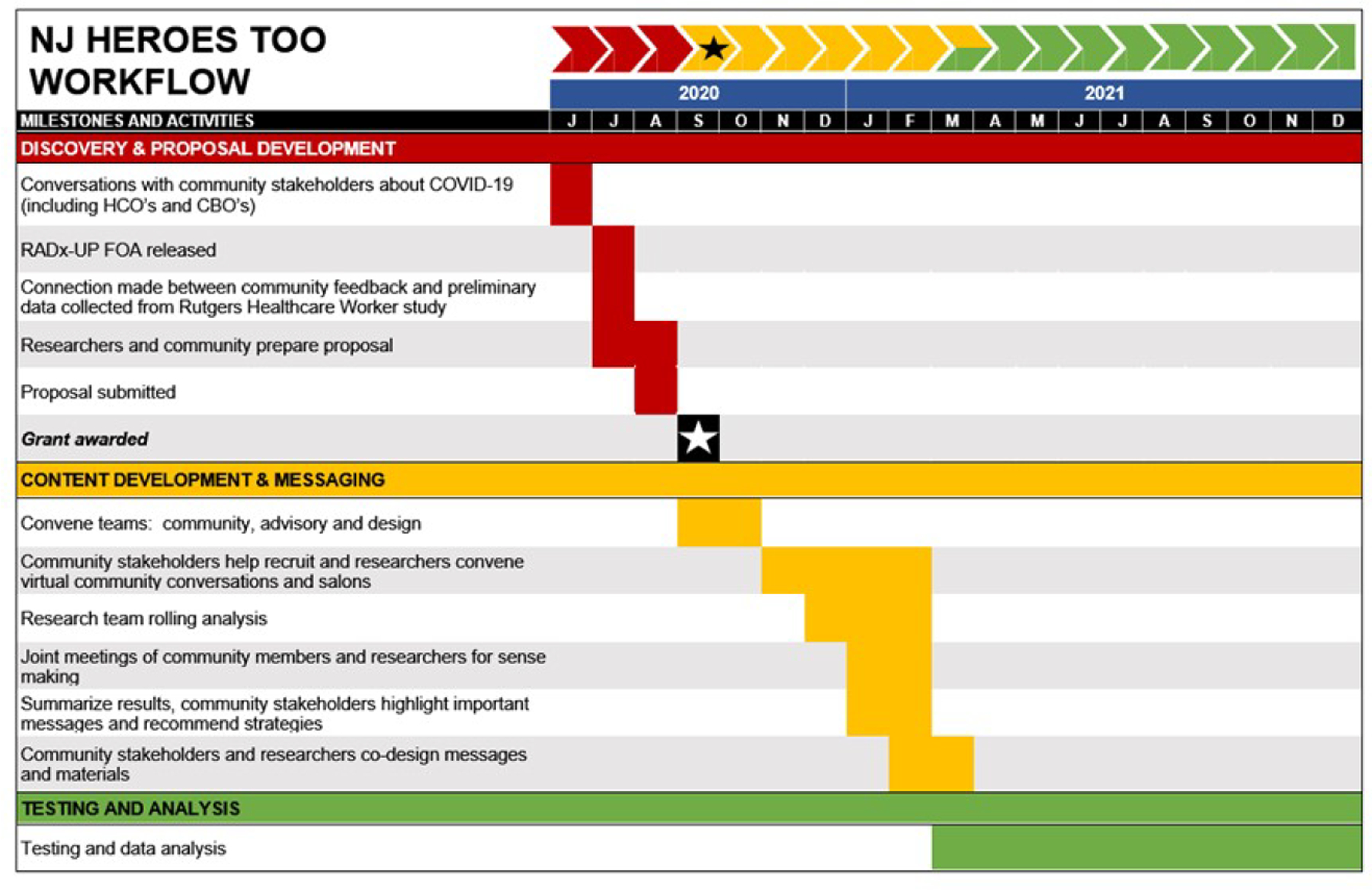

In June 2020, the NIH issued a funding opportunity for “Community Engaged Research on COVID-19 Testing among Underserved and/or Vulnerable Populations.”25 This opportunity addressed many of the issues that Rutgers researchers had heard about testing hesitancy from community partners representing Black and Latino communities and essential healthcare workers (HCW) in support roles. (e.g., certified nursing assistants, and environmental and dietary services staff). A transdisciplinary group of Rutgers researchers together with community-based and healthcare organizations (CBOs and HCOs) co-developed the NJ HEROES TOO project in response to the NIH solicitation. The project’s title, “New Jersey Healthcare Essential WoRker Outreach and Education Study-Testing Overlooked Occupations (NJ HEROES TOO)” resulted from community partners’ concerns that HCWs in essential worker support roles, many who are Black and Latino, were being overlooked as heroes. See Figure 2 for NJ HEROES TOO Workflow including the project’s milestones and activities.

Figure 2.

NJ HEROES TOO workflow including milestones and activities for June 2020 to December 2021

This workflow diagram is shown as a fragmented arrow illustrating three phases of the project representing milestones and activities.

Red sections represent Discovery and Proposal Development

Yellow sections represent Content Development and Messaging

Green sections represent Testing and Analysis

Below the fragmented arrow is a timeline in black with white letters that illustrates each month, represented by its initial letter, from June 2020 to December 2021

The “discovery and proposal development” phase is represented with red blocks in June and July 2020 and includes the following activities:

Conversations with community stakeholders about COVID-19 (June 2020)

RADx-UP FOA released (July 2020)

Connection made between community feedback and preliminary data collected from Rutgers Healthcare Worker study (July 2020)

Researchers and community prepare proposal (July and August 2020)

Proposal submitted (August 2020)

Grant awarded is represented by black block with a white star (September 2020)

The “content development and message” phase is represented with yellow blocks in September 2020 through March 2021 and includes the following activities:

Convene teams: community, advisory, and design

Community stakeholders recruit and researchers convene virtual community conversations and salons

Research team rolling analysis

Joint meetings of community members and researchers for sense making

Summarize results, community stakeholders highlight important messages and recommend strategies

Community stakeholders and researchers co-design messages and materials

The “testing and analysis” phase is represented with green blocks in March 2021 through December 2021 and includes the following activities:

Testing and data analysis

The project, funded by the NIH RADx-UP Initiative (UL1TR003017–02S2), has two primary goals. During the content development and messaging phase, researchers worked with CBOs and HCOs (partners) to identify community residents and HCWs in support roles to participate in online community conversations to better understand attitudes and perceptions of COVID-19, including mitigation strategies, testing, and vaccinations,12,26 and co-designed messages and materials. During the testing and analysis phase, the study team—comprised of CBO, HCO, and researchers—worked together to recruit study participants to increase testing in Black and Latino communities. In this paper, we describe our comprehensive engagement strategy for the content development and messaging phase including laying the groundwork for the testing and analysis phase of the project.

For this project, we utilized a community engaged model that emphasizes collaborations between CBO and HCO partnering organizations with faculty, students, and staff from various disciplines. Since 2006, faculty and staff at the Rutgers University-Newark, Office of University-Community Partnerships (OUCP)/Center for Health Equity and Community Engagement have worked with community partners around several different health and social issues (e.g., brain health27). This work resulted in the development of a Transdisciplinary Intergenerational Community Engagement Model (TICEM)27. The TICEM model was based on early models of community-campus partnerships28, 29 and publicly engaged scholarship and was refined to incorporate elements of team science23 and community-engaged research24. This model is more fully described in the Methods section and in Table 2.

Table 2.

Transdisciplinary Intergenerational Community Engagement Model (TICEM)a

| Number | TICEM Principle | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Involve community representation in all stages of program development and/or research design and implementation | Participating organizations were involved in planning and conducting the study as well as during dissemination efforts. • During planning, much of what was heard from community-based and healthcare organization partners (CBOs and HCOs/partners) about testing challenges was incorporated into the NIH proposal. • The partners provided input into the scheduling of the virtual community conversations (e.g., hosting a weekend conversation). |

| 2 | Build trust between stakeholders | Used materials and early rapid cycle meetings for the partners and researchers to get to know one another. • All partnering organizations had long-term and trusted relationships with at least one researcher and some of the organizations also had long-term relationships with one another. • Prior to the first virtual meeting, detailed information about each of the partners was circulated to all team members. • During early meetings, conducted lengthy introductions where researchers and partners from the various counties introduced themselves and the organization they represented. • Shorter rollcalls were employed once team members knew one another. |

| 3 | Leverage existing resources and opportunities | Brought in researchers to provide information to the community. • Provided access to some of the investigators with expertise in pandemics and public health emergencies. Partners had questions answered and discussions that assisted them in serving their communities (e.g., safety and efficacy of the vaccines). |

| 4 | Foster reciprocity among stakeholders | Partners provided insights into their specific populations and the project team incorporated these into the project. • Some partners used social media to reach their members while others used postcards or flyers. Project materials were customized and specific online toolkits were developed for each organization. |

| 5 | Promote sustainable relationships and partnerships | The researchers approached this project as the beginning of a long-term relationship rather than a solitary projected. Some researchers are already working with the partners on different projects. A few examples, include: • Partnership for Maternal and Child Health of Northern NJ and Program for Parents are working with and the State of NJ on a maternal and child health program. • Jazz4PCA, Program for Parents, Parker and OUCP supported families to attend a local event. • Some partners are currently serving on Rutgers University internal advisory boards. |

| 6 | Harness opportunities for intergenerational interaction to promote sustainability | The various teams included multigenerational members as well as organizations serving populations of different ages. • The team purposefully hired students and trained them to work with the partners. Several became coaches for the partners during the testing and analysis phase. • Organizations such as East Orange Senior Volunteer Corporation and Township of Hillside Senior Recreation Center serve older adults and Central Jersey Family Health Consortium, Program for Parents, and the Partnership for Maternal and Child Health of Northern New Jersey serve young families and children. |

| 7 | Acknowledge and embrace, value and encourage mutual respect among all parties inclusive of age, educational attainment, social status, etc. | All partners were embraced and valued as members of the project team. • Materials were designed collectively with partners to be inclusive of ages, diverse racial/cultural identities, educational attainment, incomes levels, and abilities. |

| 8 | Integrate expertise brought by the various stakeholders | Study approaches were altered based on the expertise brought by each CBO and HCO. • At the advice of the CBO Design Team and community advisory boards, additional community conversations were added to capture more perspectives from Black and Latino men. • The team shifted to interviews instead of community conversations for the health care workers because job demands made it difficult to get health care workers together at one time. |

| 9 | Address context and stimulate transformative change | Co-created materials during the salons where suggestions by the community partners were incorporated into the materials. • Community partners suggested removing some similar and more “traditional” looking images to include mixed-race, same gender parented, and intergenerational families to be more representatives of the people they served. • Content was adjusted to make it easier for people to participate in the study, including changing language to reflect each county or make materials less specific to a single age population or adding QR codes to make it easier to participate. |

| 10 | Align goals and actions to produce usable information for all | The researchers and CBO and HCO partners aligned goals to be beneficial for all the communities. More specifically, NJ HEROES TOO goals included: • Better understand COVID-19 testing patterns among underserved and vulnerable populations, • Strengthen the data on disparities in infection rates, disease progression and outcomes, • Develop strategies to reduce the disparities in COVID-19 testing, and • Launch outreach campaigns and expand access to COVID-19 testing in Black and Latino communities disproportionately affected by COVID-19 in Essex, Middlesex, Passaic and Union counties. |

| 11 | Engage neutral conveners to reduce biases and ensure smooth and effective implementation | Salons were facilitated by experienced staff trained to allow partners to openly discuss areas of agreement and disagreement. • Partners had an open discussion about focus group data particularly around the reasons for and differences seen in the Black and Latino focus groups. An example, in the Latino groups, participants reported logistical problems with testing and in the Black groups, participants indicated their distrust with the health care and research communities. |

These principles were developed with the participation of multiple research/community partners during over a decade of working together. Developed by Rutgers University-Newark, Office of University-Community Partnerships (OUCP)/Center for Health Equity and Community Engagement. Since 2006, OUCP has worked with researchers to integrate community engagement, teaching and training, and research and scholarship as critical elements for supporting community-based research models that build trust and sustain relationships. The community-engaged approach leverages community partnerships to develop a culture of promoting trust between Rutgers researchers and community partners and valuing community input before and during the process.

OBJECTIVES

This paper presents a case study and describes how researchers and community-based organization (CBO)/healthcare organization (HCO) stakeholders rapidly assembled a study team during the COVID-19 public health emergency using a community-engaged approach. Building upon longstanding relationships, community partners (inclusive of CBOs and HCOs in this paper) and research partners sought to identify strategies that could enhance access to COVID-19 testing among Black and Latino communities. This paper also describes how strong relationships between researchers and CBO and HCO representatives were developed and sustained throughout the process. We developed a commitment of cooperation by valuing CBO and HCO partners, aligning expectations among all stakeholders. Our partnership integrated partners’ expertise about the communities they serve and technical knowledge from the researchers during a time of great uncertainty. Thus, this partnership leveraged the strengths of all constituents, illustrating how to cultivate a research/community partnership to address communities’ complex needs during public health crises.

METHODS

The study design including CBO and HCO participation was approved by the Rutgers Biomedical Health Sciences Institutional Review Board. Virtual meetings were recorded using the secure Rutgers Zoom platform, and detailed notes/minutes were taken and distributed to all study team members.

Partnership Model

NJ HEROES TOO utilized the Transdisciplinary Intergenerational Community Engagement Model (TICEM) that engages a community respectfully through a process so that solution building can be inclusive, and ultimately more readily accepted by communities. Our goal was to partner community members with faculty, students, and staff from various disciplines to promote sustainable community engagement. This transdisciplinary and intergenerational partnership was incorporated into all levels including the families and populations served by the partners. For example, researchers came from many different disciplines (e.g., social sciences, healthcare, microbiology, public health, public policy, and translational science) and partners focused on different services (e.g., educational achievement, poverty, food housing, aging, and health and wellness). TICEM embraces key elements of other community engaged models including building trust, cultivating mutual respect, ensuring reciprocity, and building programs in a mutually understood context. TICEM principles incorporate interaction and feedback from community-based stakeholders, which helps mitigate negative perceptions and fears that hinder productive and sustainable relationships. Instances of the TICEM principles are noted in the methods section and Table 2 lists each principle with examples from this project.

In this section, we describe how researchers and community partners worked together to plan and conduct the study and disseminate the study results.

Planning the Study – NJ HEROES TOO

When NIH issued its funding opportunity in June 2020,25 a transdisciplinary group of researchers30 could quickly respond because in Newark and New Brunswick researchers were participating in regular discussions with community partners who described challenges with COVID-19 testing sites including poor access (e.g., no public transit available), logistical issues (e.g., lack of preferred language speakers), and concerns about what to do in case of a positive test (e.g., job loss and inability to isolate at home). Concurrently, Rutgers researchers from this team were engaged in a prospective cohort study to characterize factors related to SARS-CoV-2 viral transmission and disease severity in HCW and non-HCW. These studies found that Black and Latino HCWs were more likely to test positive for COVID-19 compared to white workers31 as were HCWs in support roles compared to physicians and nurses.32

Researchers previous partnerships with various CBOs27,33 facilitated rapid mobilization during this public health emergency. Team members from OUCP and the New Jersey Alliance for Clinical and Translational Science’s (NJ ACTS) Community Engagement Core at Rutgers approached CBO and HCO partners for the project. To better facilitate proposal development with the partners, the researchers distilled the RFP and created a plain language factsheet introducing COVID-19 and COVID-testing in Black and Latino communities. This factsheet sketched out the grant deliverables, described how partnering organizations could participate in the project, resources available, benefits to participating individuals/families, and use of project data. This document allowed partners to form opinions on how the NIH priorities lined up with their needs and served to facilitate in-depth conversations with partners, which helped shape the proposal. We focused on four NJ counties (Essex, Middlesex, Passaic, Union), which had high percentages of Black and Latino populations, and representatives from eighteen CBOs and four HCOs agreed to participate. See Table 1 for details about the CBO and HCO including counties served, partner types, and populations served.

Table 1.

Community-based and healthcare organizations participating in the NJ HEROES TOO study

| Community-Based Organizations | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Primary Location | Counties Served | Types of Partners | Populations Served/Study Recruitment Foci | ||||||||||||||||||

| Essex | Middlesex | Passaic | Union | Residents | Leaders | Advocates | Black | Latino | Men | Women | Youth | Families | Seniors | Low-Income | Disabled | Maternal & Child Health | Mental Health | Chronic Disease | Faith Based | Prison Re-Entry | ||

| ASPIRA, Inc. of New Jersey | Newark | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| Central Jersey Family Health Consortium | North Brunswick | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Communities in Cooperation / Interfaith Action Movement | Newark | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| East Orange Senior Volunteer Corporation | East Orange | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Health Coalition of Passaic County | Paterson | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Jazz for Prostate Cancer Awareness (Jazz4PCA) | Parlin | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Mobile Family Success Center | Perth Amboy | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| New Brunswick Area NAACP | New Brunswick | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| New Brunswick Tomorrow | New Brunswick | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| New Hope Now Community Development Corporation | Newark | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Partnership for Maternal & Child Health of Northern New Jersey | Newark | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| Programs for Parents | Newark | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Puerto Rican Action Board (PRAB) | New Brunswick | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Sister2Sister | Somerset | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| The Bridge | Irvington | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Township of Hillside Senior Recreation Center | Hillside | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| United Way of Greater Union County | Elizabeth | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| Urban League of Union County | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| Health Care Organizations | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Name | Primary Location | Counties Served | Types of Partners | Population Served/Study Recruitment Foci | ||||||||||||||||||

| Essex | Middlesex | Passaic | Union | Residents | Leaders | Advocates | Black | Latino | Men | Women | Youth | Families | Seniors | Low-Income | Disabled | Maternal & Child Health | Mental Health | Chronic Disease | Faith Based | Prison Re-Entry | ||

| Parker Health Group | Piscataway | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital | New Brunswick | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

| University Hospital | Newark | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| Visiting Nurse Association Health Group (VNAHG) | Holmdel (Statewide network) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

Conducting the Study

Partnership during planning, project implementation, and decision making

CBO and HCO partners engaged in project, planning, implementation, and decision-making as members of the NJ HEROES TOO CBO and HCO Design Teams and a Community and Healthcare Worker Advisory Board. Researchers and CBO and HCO partners reflected NJ’s demographically diverse population and included individuals of different races, ethnicities, and generations (TICEM 6). The NJ HEROES TOO team was organized with the researchers providing project management and staffing and community partners participating in NJ HEROES TOO as members of the design teams (which provided input into the study) and as members of the advisory team. All partners were compensated for their efforts in the study; approximately $400,000 was distributed to the partners at the beginning of the grant.

Community-Based Organization Design Team and Healthcare Organization Design Team

The organizations on the CBO and HCO Design Teams provided input or participated in the study by co-creating and co-designing messages and materials, conducting outreach, and providing recommendations (see specific examples in Table 2). The work of both design teams was guided by the eleven TICEM Principles. Researchers worked with CBO and HCO partners to design and implement the study (TICEM 1). This design process included biweekly virtual meetings and a series of four rapid-cycle Community Engagement Virtual Salons adapted from engagement studios created by the Meharry-Vanderbilt Community Engaged Research Core of the Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research.34 The Design Teams each held four meetings and four salons with an average of 35 partners representing 18 CBOs, 4 HCOs, and 15 researchers. Table 3 provides a detailed summary including participation at each meeting/salon.

Table 3.

Summary of NJ HEROES TOO meetings and salons

| Community-Based Organization Design Team Meetings (CBO) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meeting | Date | Purpose | Discussion description and CBO input | Participation (n) | |

| CBO Participants / Organizations | Researchers | ||||

| CBO 1 | October 28, 2020 | General Overview of Project | Held long introductions of each organization, their CBO representatives, and the researchers. Researchers presented an overview of NJACTS and NJ HEROES TOO including partnership, shared vision, study team, timeline, and meeting schedule. CBOs made suggestions on information sources, timeline, and resource provision for those testing positive for COVID-19. | 21 / 15 | 9 |

| CBO 2 | November 18, 2020 | Planning Project Start | Discussed recruitment for community conversations including reviewing recruitment flyer, fielding questions, and recording suggestions. Reviewed administrative matters. CBOs made recommendations for recruitment process and materials, so they were more representative of all subpopulations. | 21 / 14 | 12 |

| CBO 3 | December 2, 2020 | Recruitment Progress | Researchers provided overview of recruitment and the two phases of the project and answered questions about recruitment and aspects of COVID that might affect the project. CBOs recommended developing frequently asked questions for potential study participants. | 21 / 13 | 11 |

| CBO 4 | December 16, 2020 | Preliminary Findings from Community Conversations | Researchers presented on and answered questions about preliminary findings from the community conversations and the informed consent document to be utilized for the testing intervention. CBOs noted concerns about community conversation participant demographics (e.g., Black/Latino men). | 26 / 15 | 13 |

| CBO Salons (S) | |||||

| Meeting | Date | Purpose | Discussion description and CBO feedback | Participation | |

| CBO Participants / Organizations | Researchers | ||||

| CBO S1 | January 13, 2021 | Common Data Element Feedback | Researchers presented the plan for salons and information about RadxUP and the survey data elements called common data elements (CDEs). Three breakout groups discussed CDEs and the large group heard and discussed reports from each small group. CBOs made recommendations about the CDEs including edits and deletions for clarity and greater study participation. | 30 / 18 | 15 |

| CBO S2 | January 27, 2021 | Focus Group Feedback | Researchers presented the demographics of and summarized data from the focus groups. Data described included trusted information sources, barriers and facilitators to COVID-19 testing, and vaccine concerns. CBOs helped provide interpretation of the preliminary findings particularly related to materials and processes for the testing intervention. | 30 / 18 | 15 |

| CBO S3 | February 10, 2021 | Marketing Materials for Testing Recruitment | Marketing consultant presented marketing strategies and materials for testing recruitment. CBO Design team had a facilitated discussion about the toolkit being created for and provided to CBOs. CBOs suggested changes on the design and content of marketing materials. | 37 / 18 | 15 |

| CBO S4 | March 10, 2021 | Variants & Testing Protocol | A NJ HEROES TOO investigator presented information and answered questions about NJ’s COVID-19 status at that time, COVID variants, and the three vaccines. A representative from the study’s testing company provided information about the process that participants would go through during the testing intervention. CBOs asked questions about and provided suggestions about the testing intervention process. | 30 / 18 | 15 |

|

Healthcare Organization Design Team Meetings (HCO) | |||||

| Meeting | Date | Purpose | Discussion description and HCO feedback | Participation | |

| HCO Participants / Organizations | Researchers | ||||

| HCO 1 | October 26, 2020 | General Overview of Project | Introductions of healthcare organization partners and researchers. Researchers presented about NJACTS and NJ HEROES TOO including partnership, shared vision, study team, timeline, and meeting schedule; purpose of HCO Design Team; and recruitment for focus groups and testing phases. | 5 / 4 | 4 |

| HCO 2 | November 9, 2020 | Planning Project Start | Design team prepared for recruitment for healthcare worker (HCW) conversations including reviewing recruitment flyer, current strategies to communicate with the HCOs’ workforce, and potential barriers to recruitment and testing. Reviewed administrative matters. HCOs made suggestions about the flyers, particularly customizing for each organization and using images that better reflect HCWs. | 4 / 3 | 4 |

| HCO 3 | December 7, 2020 | Recruitment planning | Researchers presented initial data from the first community conversation with Black participants. HCOs reviewed and made suggestions regarding the recruitment flyer for HCWs and asked questions related to the testing intervention for HCWs and their families. | 4 / 4 | 3 |

| HCO 4 | December 21, 2020 | Preliminary Findings from Community Conversations | Researchers presented preliminary findings from the community conversations. HCO Design team discussed the testing intervention process. HCOs made suggestions to improve the testing process. | 5 / 4 | 4 |

| HCO Salons (S) | |||||

| Meeting | Date | Purpose | Discussion description and HCO feedback | Participation | |

| HCO Participants / Organizations | Researchers | ||||

| HCO S1 | January 11, 2021 | Common Data Element Feedback | Healthcare organizations gave updates on recruitment for HCW conversations. Researchers presented RadxUP survey data elements called common data elements (CDEs). HCO Design team discussed CDEs and informed consent documents with HCOs providing recommendations regarding confusing language and questions that might alienate some HCWs. | 5 / 4 | 5 |

| HCO S2 | January 25, 2021 | Community conversations Feedback | Researchers presented demographics of and summarized data from community conversations. Data included trusted information sources, barriers and facilitators to COVID-19 testing, and vaccine concerns. HCO Design team discussed questions about messaging from marketing consultant and HCOs made recommendations regarding missing relevant messages for HCWs and reasons HCWs and family members are hesitant to be tested. | 3 / 3 | 6 |

| HCO S3 | February 8, 2021 | Marketing Materials for Testing Recruitment | Marketing consultant presented marketing strategies and materials for the testing intervention. Facilitated discussion about the toolkit being created for and provided to HCOs and design and content of marketing materials. HCOs provided feedback on the design and content of marketing materials. | 2 / 2 | 6 |

| HCO S4 | March 22, 2021 | Testing intervention preparation | Researchers provided information about the participant process for the testing intervention and about meetings and outreach strategies going forward. | 5 / 4 | 6 |

| Community and HCW Advisory Board Meetings (CAB) | |||||

| Meeting | Date | Purpose | Discussion description | Participation | |

| CAB Participants | Researchers | ||||

| CAB 1 | December 16, 2020 | Findings from community conversations | Researchers provides overview of findings from community conversations and engages in discussion about what might help the next phase of the project. CAB recommends adding organizations to better reflect important subpopulations. | 2 | 4 |

| CAB 2 | February 25, 2021 | Project direction and feedback for improvement | Researchers solicited input on the design of phase 2 particularly what can be done better. CAB provided an understanding of some of the challenges that are facing the community regarding testing and made recommendations about overcoming these challenges. | 4 | 3 |

The first four team meetings, conducted separately with the CBO and HCO Design Teams, built trust and trustworthiness, aligned expectations and goals, developed opportunities for reciprocity, and created a commitment to cooperation/collaboration while strengthening the project’s valued partnerships (TICEM 2, 4, 5, 10). The researchers recognized the importance and value of each partner because they were experts about the people and communities served with many partners living within the impacted communities (TICEM 7, 8). To align goals and actions throughout the study, the team agreed on goals and objectives, regularly provided detailed updates about the study, and obtained input from partners about research methods and materials. The team members showed commitment to one another and the project by participating in all meetings and completing deliverables according to the study’s rapid timeline as the pandemic evolved.

The four salons, conducted separately with the CBO and HCO Design Teams, were used to gain input into data elements, review data from the community conversations, and engage in bi-directional crosstalk to co-design intervention methods, materials and messaging needed to increase testing in Black and Latino communities. Each salon was facilitated by a team member and included a short presentation from a researcher affiliated with the project (TICEM 3, 11). Presentations were followed by small group discussions, guided by questions that facilitated discussion between the partners. The reconvened large group heard reports from each small group and participated in discussion. Materials reviewed during these salons included the informed consent document and common survey data elements for all RADx-UP projects,35 perceptions of preliminary data from the community conversations, input on outreach materials, and feedback on the design of the COVID-19 testing intervention.

Community and Healthcare Worker Advisory Board

Members of the Community and Healthcare Worker Advisory Board met with researchers regularly and provided guidance on priority setting, development of the awareness campaign, and decision making in response to the rapidly evolving pandemic. The different levels of involvement promoted relationship building that embraced and acknowledged the expertise of community stakeholders in partnership with researchers (TICEM 7, 8). Board members provided important feedback throughout the project including recommendations to expand CBO partnerships to reflect important subpopulations within Black and Latino communities. This brought three additional CBOs (representing cancer survivors and interfaith communities) into the CBO Design Team (TICEM 1, 3, 5, 8, 9). The Advisory Board held two meetings with an average of 5 partners and 2 researchers.

Evaluating the Partnership

NJ HEROES TOO was designed to continuously seek feedback from the partners at multiple levels including through the design teams and the advisory boards. The team solicited and used feedback to adjust the project with the ever-changing background of COVID-19 unfolding in the communities. Partners co-designed meeting agendas during debriefing discussions and provided input, through surveys, which framed presentations. Each organization regularly met virtually with a research staff person where they raised concerns or made suggestions. In addition, the researchers kept track of the various processes, meetings, and recruitment efforts and collected detailed information about the time/effort that each partner spent on the project. Plans for future evaluation include individual video interviews about the project with community partners, researchers, staff, and students involved with project, an in-person town hall/celebration where community partners and research team members will reflect together on the collaboration, and a survey evaluation for the project.

RESULTS AND LESSONS LEARNED

The COVID-19 pandemic necessitated that NJ HEROES TOO be conducted virtually, which created challenges to relationship building, information sharing, dissemination, and sustainability. Nevertheless, the partnership, working virtually, found many ways to facilitate relationships between researchers and community partners to meet each challenge.

Every Meeting and Encounter is an Opportunity for Relationship Building

The initial meetings and salons strengthened the relationships between the researchers and CBO and HCO partners. While researchers had prior relationships with some community partners, no one on the team knew all the partners. Some partners were not familiar with each other, so time was set aside to build and strengthen relationships which helped build trust between organizations and integrate expertise of community partners. Acknowledging and respecting all voices, time and space were allotted for discussions about distrust of research and discrimination in the healthcare system. At every meeting the team engaged in a lively welcome and rollcall and used breakout rooms for small groups where researchers and partners had more focused conversations.

Reciprocity through Multiple Iterations of Information Sharing, Feedback, and Modifications

Our collaborative approach created numerous opportunities for team members to learn from each other. Reciprocity was achieved through multiple iterations of purposeful information sharing, feedback solicitation, and modification of materials and methods. By hosting meetings and salons over a four-and-a-half-month period, community partners and researchers talked about their challenges, gave each other feedback that strengthened recruitment materials and improved methods for facilitating community conversations and testing interventions, making them more useful for diverse communities. Particularly important was the co-creation of messaging materials for the testing intervention. For example, in our third salon on development of the testing recruitment toolbox, the conversations between partners and researchers resulted in editing language to better appeal to communities as well as selecting different imagery that better reflects the full range of diversity of our populations served. Our partners suggested taking a tailored approach where similar messages were accompanied by different images reflecting diverse populations served by each organization. This resulted in providing each CBO and HCO partner organization with a customized toolbox of materials for their specific communities.

Opportunities for joint learning extended beyond the testing focus of NJ HEROES TOO. Throughout the project, researchers gave updates on current information about COVID-19. They met with partners multiple times to provide context and detailed county-level information about COVID-19 demographics in NJ (prevalence, deaths, etc.), testing and vaccination rates in NJ, and the importance of mitigation strategies. These sessions were informative for researchers who wanted to know what was “top of mind” in our communities and helped partners who had questions about COVID-19, the safety of the vaccines, the variants prevalent at any time, and herd immunity—topics of interest for many of the partners as guidance on vaccination and masking changed throughout the project.

Diverse Dissemination Strategies are an Important to Enhancing Engagement and Acknowledging Partner Contributions

The NJ HEROES TOO team employed diverse dissemination strategies to publicize the study, enhance engagement, and most importantly recognize partner contributions. Strategies included conventional (e.g., researchers reporting on the project at individual organization’s town halls, crediting partners work in publications, and partners co-authoring articles with researchers) and unconventional methods (e.g., encouraging cross partner and researcher participation in partner events, partners posting information on their social media,e.g., 36–37 developing videos in English and Spanish, disseminating press releases to local media, creating a lay publication focused on the collaboration38). Future plans include a video based on interviews with the team members, a panel with partners reflecting on the project, and co-authoring more peer-reviewed and lay publications.

To date, the team’s most impactful dissemination strategy has been the publication of the NJACTS 4 Us! Connect magazine.38 It is named “Connect” because many organizations became disconnected because of COVID-19. By conducting the study virtually, the team was able to “connect” and strengthen and maintain relationships with each other and our communities. The first issue focused on the NJ HEROES TOO project. The magazine depicts an inclusive approach by providing a description of the collaboration, including guiding principles; organizational structure; profiles of the researchers and each CBO and HCO. Community partners are featured with quotations about the importance of the project and in a photo gallery of their organizations. The magazine has been important to partners because it showcases their work; the team has distributed approximately 2500 print copies and electronically viewed over 550 times.

Building Relationships and Intergenerational Interaction Helps to Ensure Sustainability

The study team’s intent from the inception of NJ HEROES TOO was for to serve as a foundation for developing durable relationships between Rutgers researchers and multiple community partners. Working together on NJ HEROES TOO has strengthened existing relationships, fostered new relationships across geographic boundaries, and connected diverse community partners. This has helped create an infrastructure to respond to future public health emergencies and future community-engaged research. The NJ HEROES TOO team intentionally created opportunities for intergenerational interaction, which helped promote sustainability. Undergraduate and graduate students were recruited and mentored by faculty to participate in the project, helping them to see the impact of community-engaged research and better understand the issues facing the under-resourced communities where they live. Both researchers and partners had multiple generations working together (i.e., students, trainees, staff, administrators, faculty), which resulted in processes and materials that reflected NJ’s diverse populations. NJ HEROES TOO has facilitated a network of over 20 partnering organizations with 15 researchers across multiple campuses who have built trustworthiness and can now work with other researchers interested in community engaged research.

CONCLUSIONS

This model demonstrates how research/community partnerships can work together virtually to address public health emergencies while building sustainable relationships. Using the TICEM Principles of Engagement our diverse, intergenerational team worked together to solicit community input on the impact of COVID-19 in their communities and co-develop materials for a COVID-19-testing intervention. Our case study demonstrates that a large organizational structure of 15 researchers, 18 CBO, and 4 HCO partners can use virtual meetings and salons to build relationships using steps intended to develop reciprocity among team members. Diverse dissemination strategies helped highlight the contributions of the study’s CBO and HCO partners and has brought attention to the importance of the services that they provide for their local communities. Taking the time to develop strong long-term relationships provided success for the NJ HEROES TOO project and laid the groundwork for future work between research and community partners to address current and future needs of NJ’s densely populated communities. The lessons learned during this project could help others as they approach working in diverse communities with differing needs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank each of the participants without whom this study would not have been possible. The authors are grateful to our community-based and healthcare organization partners and Rutgers colleagues who comprise the NJ HEROES TOO team including this paper’s co-authors and the following individuals and organizations they represent: Carlos Valentine, Dan McNeil (ASPIRA Inc., of New Jersey), Robyn D’Oria, Judith Francis, and Laura Taylor (Central Jersey Family Health Consortium), Dr. Pamela B. Jones (Communities in Cooperation), Barbara Booker, Rita Butts, Wilda Hobbs, and Tania Williams-Cajuste (East Orange Senior Volunteer Corporation), Kimberly M. Birdsall, MPH (Health Coalition of Passaic County), Alfuguan Hardy, Amber Jennings, and Mayor Dahlia O. Vertreese (Hillside Senior Recreation Center), Paul Messer, Jr. and Ralph Stowe (Jazz4PCA), Megan Carduner, Rosela Roman, and Rosmery Suarez (Mobile Family Success Center), Toni Hendrix, Bruce Morgan Sr., and Deborah Morgan (New Brunswick Area Branch NAACP), Jaymie Santiago and Staff (New Brunswick Tomorrow), Pastor Joe A. Carter and Kelvin Roberson (New Hope Baptist Church), Roberto Muñiz (Parker Health Group, Inc.), Mayra Ramirez and Mariekarl Vilceus-Talty (Partnership for Maternal and Child Health of Northern New Jersey), Aitza Elhuni, José Carlos Montes, Carmelo Cintrón Vivas and programs team (PRAB), Kendra Orta (Programs for Parents), Mariam Merced, MA (Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital), Uzo Achebe, Maria Ortiz, and Tress Parker (Sister2Sister), Beverly Canady, Latisha Miller, Lou Schwarcz, and Leanna Waller (The Bridge, Inc.), James Horne and Juanita Vargas (United Way of Greater Union County), Donna L. Alexander and Kathy Waters (Urban League of Union County, Inc.), and Robert J. Rosati and Tami M. Videon (VNA Health Group).

The authors wish to thank researchers who worked on the project including NJ HEROES TOO staff (Sarah Abbas, MS, Tracy Andrews, MS, Judith Argon, MA, MTS, Alicja Bator, MPH, Casandra Burrows, BS, Jonathan Carter, MBS, Andrea Daitz, MA, Betsaida Frausto-Gonzalez, BS, Patricia Greenberg, MS, Sherri Gzemski, Nicole Hernández, MS, CHES, Jenna Howard, PhD, Emmanuel Martinez Alcaraz, MD, Epiphany Munz, BA, Yvette Ortiz-Beaumont, MPA, Veenat Parmar, MPH, Katherine Prioli, MS, Nancy Reilly, RN, MS, and William Russell, RPFT, AE-C); Rutgers students (Brittany Cardona, Maria Guevara Carpio, BS, Bryana Chamba, Assitan Drame, Jefferson Ebube, and Shivani Patel); and Support Staff (Darlene Bondoc, Mila Dunbar, MBA, and Jennifer Zabala).

Funding

Research reported in this Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics – Underserved Populations (RADx-UP) publication was supported by the National Institutes of Health under Award Number [UL1TR003017-02S2]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Ethics Statement

This research was reviewed and approved by the Rutgers Biomedical and Health Sciences IRB.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alcendor DJ. Racial disparities-associated COVID-19 mortality among minority populations in the US. J Clin Med. 2020. Jul 30;9(8):2442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel M, Critchfield-Jain I, Boykin M, Owens A, Nunn T, Muratore R. Actual racial/ethnic disparities in covid-19 mortality for the non-Hispanic Black compared to non-Hispanic White population in 353 US counties and their association with structural racism. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021. Aug 30:1–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Risk for COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death by race/ethnicity. 2021. [cited 2021 Aug 27]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html#print [Google Scholar]

- 4.United States Census Bureau. Historical population density data (1920–2020). 2021. [cited 2021 Nov 15]. Available from: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/dec/density-data-text.html [Google Scholar]

- 5.State of New Jersey, Department of Health (NJDOH). New confirmed cases over time. NJ COVID-19 dashboard. 2021. [cited 2021 Nov 15]. Available from: https://www.nj.gov/health/cd/topics/covid2019_dashboard.shtml

- 6.Statista. Death rates from coronavirus (COVID-19) in the United States as of November 15, 2021 by state. 2021. [cited 2021 Nov 15]. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1109011/coronavirus-covid19-death-rates-us-by-state/

- 7.The COVID Tracking Project at The Atlantic. New Jersey: All race & ethnicity data. 2021. [cited 2021 Dec 16]. Available from https://covidtracking.com/data/state/new-jersey/race-ethnicity

- 8.Holom B Unprecedented and unequal: Racial inequities in the COVID-19 pandemic. New Jersey Policy Perspective. 2020. [cited 2021 Dec 21]. Available from: https://www.njpp.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/NJPP-Report-Unprecedented-and-Unequal-COVID-Racial-Disparities-.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khubchandani J, Sharma S, Price JH, Wiblishauser MJ, Sharma M, Webb FJ. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy in the United States: A rapid national assessment. J Community Health. 2021. Apr;46(2):270–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher KA, Bloomstone SJ, Walder J, Crawford S, Fouayzi H, Mazor KM. Attitudes toward a potential SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: A survey of U.S. adults. Ann Intern Med. 2020. Dec 15;173(12):964–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Momplaisir FM, Kuter BJ, Ghadimi F, Browne S, Nkwihoreze H, Feemster KA, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among health care workers in 2 large academic hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. 2021. Aug 2;4(8):e2121931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jimenez ME, Rivera-Núñez Z, Crabtree BF, Hill D, Pellerano MB, Devance D et al. Black and Latinx community perspectives on COVID-19 mitigation behaviors, testing, and vaccines. JAMA Netw Open. 2021. Jul 1;4(7):e2117074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Institute of Medicine. 2000. Promoting health: Intervention strategies from social and behavioral research. Washington (DC): The National Academies Press; 2000. [cited 2021Oct 7]. Available from: 10.17226/9939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Institute of Medicine. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington (DC): The National Academies Press; 2003. [cited 2021Oct 7]. Available from: 10.17226/12875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Israel BA, Eng E, Schultz AJ, Parker A. Introduction to methods for CBPR for health. In: Israel BA, Eng E, Schultz AJ, Parker A. Methods for community-based participatory research for health. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2013. p. 4–37. [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Institutes of Health. RADx Underserved Populations (RADxUP). Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics (RADx). 2021. [cited 2021 Nov. 17] Available from: https://www.nih.gov/research-training/medical-research-initiatives/radx/radx-programs#radx-up

- 17.Ortiz K, Nash J, Shea L, Oetzel J, Garoutte J, Sanchez-Youngman S, et al. Partnerships, processes, and outcomes: A health equity-focused scoping meta-review of community-engaged scholarship. Annu Rev Public Health. 2020. Apr 2;41:177–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minkler M Using participatory action research to build healthy communities. Public Health Rep. 2000. Mar-Jun:115(2–3):191–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henrick EC, Cobb P, Penuel WR, Jackson K, Clark T. Assessing research-practice partnerships: Five dimensions of effectiveness. New York: William T. Grant Foundation; 2017. [cited 2021 Nov. 17] Available from: https://rpp.wtgrantfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Assessing-Research-Practice-Partnerships.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chung B, Jones L, Dixon EL, Miranda J, Wells K, and Partners in Care Steering Council. Using a community partnered participatory research approach to implement a randomized controlled trial: Planning the design of community partners in care. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010. Aug;21(3):780–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drahota A, Meza RD, Brikho B, Naaf M, Estabillo JA, Gomez ED, et al. Community-academic partnerships: A systematic review of the state of the literature and recommendations for future research. Milbank Q. 2016. Mar:94(1):163–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tebes JK, Thai ND. Interdisciplinary team science and the public: Steps toward a participatory team science. Am Psychol. 2018. May-Jun;73(4):549–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clinical Translational Science Awards Consortium Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force on the Principles of Community Engagement. Principles of community engagement. 2nd ed.; 2011[cited 2021 Nov 8]. Available from: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/pdf/PCE_Report_508_FINAL.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Institutes of Health (NIH). Notice of special interest: limited competition for emergency competitive revisions for community engaged research on covid-19 testing among underserved and/or vulnerable populations. Notice number: NOT-OD-20–121; 2020. [cited 2021 Nov 2]. Available from: https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-20-121.html

- 26.Rivera-Núñez Z, Jimenez ME, Crabtree BF, Hill D, Pellerano MB, Devance D, et al. Experiences of Black and Latinx health care workers in support roles during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. PLoS One. 2022. Jan 18;17(1):e0262606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gluck MA, Shaw A, Hill D. Recruiting older African Americans to brain health and aging research through community engagement: Lessons from the African-American brain health initiative at Rutgers University-Newark. Generations. 2018. Summer;42(2):78–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holland B Reflections on Community-Campus Partnerships: What Has Been Learned? What Are the Next Challenges? In Pasque P P, Smerek RE, Dwyer B, Bowman N, Mallory BL, editors. Higher Education Collaboratives for Community Engagement & Improvement. Anna Arbor, MI: National Forum on Higher Education for the Public Good; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silka L, and Renault-Caragianes P Community−University Research Partnerships: Devising a Model for Ethical Engagement. J High Educ Outreach Engagem. 2006. Jun;11(2):171–183. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kessel F, Rosenfield PL. Toward transdisciplinary research: Historical and contemporary perspectives. Am J Prev Med. 2008. Aug;35(2 Suppl): S225–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barrett E, Horton DB, Roy J, Gennaro ML, Brooks A, Tischfield J, et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in previously undiagnosed health care workers in New Jersey, at the onset of the U.S. COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Infect Dis. 2020. Nov 16;20(1):853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barrett ES, Horton DB, Roy J, Xia W, Greenberg P, Andrews T, et al. Risk Factors for severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 infection in hospital workers: Results from a screening study in New Jersey, United States in spring 2020. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020. Oct 31;7(12):ofaa534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jimenez ME, Hudson SV, Lima D, Crabtree BF. engaging a community leader to enhance preparation for in-depth interviews with community members. Qual Health Res. 2019. Jan; 29(2):270–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Joosten YA, Israel TL, Williams NA, Boone LR, Schlundt DG, Mouton CP, et al. Community engagement studios: A structured approach to obtaining meaningful input from stakeholders to inform research. Acad Med. 2015. Dec;90:1646–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.RADx-UP. NIH RADx-UP common data elements; 2021[cited 2021 Nov 3]. Available from: https://radx-up.org/learning-resources/cdes/

- 36.Muñiz R Why bringing COVID testing to minority groups at a disadvantage is crucial for NJ; 2020 Nov 11 [cited 2022 Apr 8]. In Parker Life Blog [Internet]. Piscataway, NJ: Parker Life. Available from: https://www.parkerlife.org/blog/november-2020/why-bringing-covid-testing-to-minority-groups-at-a-disadvantage-is-crucial-for-nj [Google Scholar]

- 37.Castañeda M New Brunswick Tomorrow partners with Rutgers University to bring COVID-19 testing to disadvantaged communities; 2020 Nov 21 [cited 2022 Apr 8]. In New Brunswick Tomorrow Blog [Internet]. New Brunswick, NJ: New Brunswick Tomorrow. Available from https://www.nbtomorrow.org/blog/new-brunswick-tomorrow-partners-with-rutgers-university-to-bring-covid-19-testing-to-disadvantaged-communities [Google Scholar]

- 38.NJ ACTS. FOCUS: NJ HEROES TOO: A University/community partnership serving Essex, Middlesex, Passaic, and Union Counties. NJ ACTS 4 Us! CONNECT; 2021. Fall [cited 2021 Nov 3]. Available from: https://online.flippingbook.com/view/803544805/