Abstract

Purpose:

Radiotherapy (RT) is a widely employed anti-cancer treatment. Emerging evidence suggests that RT can elicit both tumor-inhibiting and tumor-promoting immune effects. This study is to investigate immune suppressive factors of radiotherapy.

Experimental Design:

We used a heterologous two-tumor model in which adaptive concomitant immunity was eliminated.

Results:

Through analysis of PD-L1 expression and MDSC frequencies using patient PBMC and murine two-tumor and metastasis model, we report that local irradiation can induce a systemic increase in MDSCs, as well as PD-L1 expression on DCs and myeloid cells, and thereby increase the potential for metastatic dissemination in distal, non-irradiated tissue. In a mouse model using two distinct tumors, we found that PD-L1 induction by ionizing radiation (IR) was dependent on elevated chemokine CXCL10 signaling. Inhibiting PD-L1 or MDSCs can potentially abrogate RT-induced metastasis and improve clinical outcomes for patients receiving RT.

Conclusions:

Blockade of PD-L1/CXCL10 axis or MDSC infiltration during radiation can enhance abscopal tumor control and reduce metastasis.

Translational Relevance:

Radiotherapy (RT) results in molecular and cellular changes locally and systemically. The rare occurrence of the “abscopal” effect, in which tumors regress outside of the irradiation field, suggests the complexity of the interaction between the anti- and pro-tumor host responses. Consequently, dissecting these responses is critical for improving radiotherapy. We used a heterologous two-tumor model in which adaptive concomitant immunity was eliminated. Irradiating one tumor revealed the pro-tumor suppressive effects including systemic increases in myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and PD-L1 expression on myeloid cells, Type I interferon responsive cytokine CXCL10 serves as a signal to promote distant metastasis. We report that local tumor irradiation increases the potential for metastatic dissemination through systemic induction of PD-L1 and recruitment of MDSCs in distal, non-irradiated tissue. Our results suggest that patients with absent or low PD-L1 levels might benefit from PD-1/PD-L1 blockade and should be tested for PD-L1 induction following initiation of RT.

INTRODUCTION

Radiotherapy (RT) is an important cancer treatment that provides local tumor control as an alternative to surgery or in combination with surgery/chemotherapy to improve or preserve organ function and homeosis. The role of RT in the potentially curative treatment of metastatic disease has assumed increased attention with the identification of an oligometastatic state and the advent of combination of RT and immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) in the clinic with the goal of increasing anti-tumor systemic immunity. The anti-tumor immune effects elicited by RT(1) include increased tumor MHC class I expression, dendritic cell (DC) maturation, antigen presentation and trafficking, T-cell trafficking to the tumor (2,3), cytokine production, such as type I and type II interferons (4), NK cell activation (5), and anti-tumor macrophages(6) among others. The abscopal effect is an anti-tumor response outside of a locally-irradiated field that mediates tumor regression. However, this effect is rare with RT as a sole treatment (7,8). The abscopal effect has been attributed in part to T cells activated by RT which then attack distal tumors, although recent reports implicate macrophages as well (9,10). In recent years, hundreds of clinical trials combining checkpoint inhibition with RT have been initiated and many completed (reviewed in (11,12)). Despite favorable responses of a few individual patients, only two phase 3 randomized trials employing adjuvant PD-1 blockade have shown significantly improved survival (13,14) by inhibiting microscopic metastatic disease.

With the combination of immune checkpoint inhibitors and RT, such as those targeting CTLA-4 or PD-1/PD-L1, a greater number of abscopal remissions have been reported (15). However, the abscopal effect with combination single-site RT and ICB is difficult to separate from the systemic effects of ICB alone, and it is not consistent enough to be incorporated into clinical practice (11,12). By contrast, the mechanisms by which ionizing radiation (IR) promotes metastasis in experimental systems have been linked to various mechanisms, including IR-induced leukopenia (16), EMT-mediated tumor spread, which enhances tumor invasion and migration(17). Additional IR effects on blood vessel permeability and induction of hypoxia have also been reported to increase metastasis (18).

In clinical practice, the strategy of using RT to a single site to induce an immune response and coupling that with ICBs has yet to translate into clinical benefit. One explanation is that RT simultaneously triggers pro-immune and immune-suppressive events, such as enhanced recruitment of MDSCs and regulatory T cells (Tregs) into irradiated tumors. Pre-clinical and clinical studies suggest that MDSCs may play a major role in suppressing anti-tumor immunity and are associated with adverse clinical outcomes. Tumor-infiltrating and circulating MDSCs may account for preclinical/clinical radio- and immune checkpoint blockade resistance (19,20). In pre-clinical and clinical studies, both fractionated and hypo-fractionated treatment regimens resulted in MDSC expansion (16,21,22), which led to tumor radioresistance (22–24).

IR has been demonstrated to upregulate PD-L1 expression in tumor cells (25) and antigen presenting cells (APCs) (26), as well as other myeloid cells (27). Experimental data in autoimmune disease and viral infections (28) suggest that PD-L1, which is induced by type I and type II interferons (29), mediates its effects through expression of PD-1 on T cells as a mechanism to downregulate inflammatory responses. In the context of IR, PD-L1 has been shown to activate DNA repair pathways and suppress IR-induced inflammation (30).

Preclinical data indicate that the cGAS/STING/type I interferon (IFN-I) pathway promotes the efficacy of IR (26). In murine tumor models, activation of the STING/IFN-I signaling pathway following IR augments DC maturation and activation, thereby promoting anti-tumor effects. Many studies have demonstrated that the IFN-responsive protein CXCL10, originally identified as a T-cell chemoattractant, is involved in anti-tumor immunity(31). By contrast, recent studies suggest that CXCL10 expressed by myeloid cells could be involved in the development of metastasis and associated with adverse patient outcomes (32).

We sought to study the balance of pro-tumor and anti-tumor factors contributing to distal effects. Here we demonstrate that local IR induces systemic PD-L1 expression in the myeloid compartment and increases MDSC recruitment, while also augmenting tumor-specific T-cell function. To dissect these factors, we employ a heterologous two-tumor model in which a distinct contralateral unirradiated tumor spontaneously metastasizes to the lung. When T cell-dependent concomitant immunity is eliminated, radiation leads to progression of distal tumor growth and enhanced metastasis. PD-L1 induction in distal tissues relies on STING/IFN-I signaling and is mediated by CXCL10. Neutralization of IR-induced PD-L1 and MDSC blockade reverse IR-induced metastasis. We propose a novel personalized treatment strategy wherein the administration of anti-PD-L1 antibodies is guided by measurement of PD-L1 upregulation post-RT, irrespective of pre-treatment PD-L1 status.

Material and Methods

Cells and reagents

The MC38 tumor cell line was kindly provided by Dr. Yang-xin Fu of The University of Chicago and grown in DMEM medium containing 10% FBS, at 37°C and 5% CO2. LLC cells were obtained from ATCC (CRL-1642) and passaged through C57BL/6 once by culturing lung metastatic nodules. B16-F10 cell line was purchased from ATCC (CRL-6475). KPC cell line was a kind gift from Dr. Hidayatullah G Munshi at Northwestern University. Cell lines were authenticated and tested for mouse pathogens by IDEXX (Westbrook, Maine). Anti-CCR2 was produced according to previously described methods (33). Depleting/blocking antibody against PD-L1 (BE0101) was purchased from BioXcell. Flow antibodies: PB-anti-CD11b (101224), BV711-anti-CD11b (101242), PB-anti-CD45 (103126), BV510-anti-CD45 (103138), PE/CY7-anti-CD11C (117318), PerCP/Cyanine5.5-anti-F4/80 (123128), APC-anti-F4/80 (123116), FITC anti-Ly6C (128006), PerCP/Cyanine5.5 anti-Ly6C (128012), BV605-anti-Ly6G (127639), PE-anti-PD-L1 (124308), PE-anti-CD4 (116005), APC/CY7-anti-CD8 (100714), recombinant mouse CXCL10 (573604), and recombinant mouse GM-CSF (576306) were purchased from Biolegend. Anti-mouse CXCL10 antibody (134013, MA523774) and the mouse CXCL10 ELISA kit (BMS6018) were purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific. The human CXCL10/IP10 ELISA kit was purchased from R&D (DIP 100). The CD8 T-cell selection kit (18953) was purchased from Stemcell. For human PBMC flow, Alexa Fluor 532-anti-CD3 Monoclonal antibody (UCHT1) (58–0038–42), Super Bright 436-anti-CD19 (SJ25C1, 62–0198–42), Super Bright 436-anti-CD20 (62–0209–42), PerCp-efluor710-anti-CD8a (46–0087–42), and eFluor 450-anti-CD16 (48–0168–42) were purchased from ThermoFisher. Brilliant Violet 480™ anti-human CD141 (746604) was purchased from Fisher scientific. PerCP/Cyanine5.5-anti-CD45 (304028), Alexa Fluor® 647 anti-human CD25 (356128), APC/Fire™ 750-anti-human HLA-DR (3076580), Brilliant Violet 510™ anti-human CD14 (301842), Brilliant Violet 711™ anti-human CD56 (318336), Zombie NIR™ Fixable Viability (423105), PE/Dazzle™ 594 anti-human CD71 (334120), APC anti-human CD235a (349114), Brilliant Violet 605™ anti-human CD192 (357214), Brilliant Violet 785™anti-CD1C (331544), Alexa Fluor® 488 anti-human CD45RA (304114), Brilliant Violet 421™ anti-human CD197 (CCR7) (353208), Brilliant Violet 650™ anti-human CD279 (PD-1) (329950), Brilliant Violet 750™ anti-human CD4 (344643), PE/Cy5 anti-human CD33(303406), PE-anti-PD-L1 (329706), and human Trustain FcX™ Fc Blocker (422302) were purchased from Biolegend.

Mice

C57BL/6J wild type (WT), Ifnar1 knockout (IFNAR KO), Rag1 knockout (Rag KO), CXCR3 knockout (CXCR3 KO), and STING knockout (STING KO) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. All experimental groups included randomly chosen female littermates approximately 8 weeks old and of the same strain. All mice were maintained and used in accordance with guidelines established by the Institute of Animal Care and Use Committee of The University of Chicago.

Patient samples and study approval.

Patient samples (PBMCs) and sera were obtained from patients treated at The University of Chicago enrolled in clinical trial NCT03223155 (34). Written informed consent from all patients was obtained for all the information used. The study was conducted in accordance with Declaration of Helsinki, and the study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Chicago. Patient samples were stored and curated at the Human Immunologic Monitoring facility of The University of Chicago.

The animal studies were approved by the Institute of Animal Care and Use Committee of The University of Chicago.

Tumor growth and treatment.

1×106 MC38 or MC38-OTI-Zsgreen (MC38OZ) (GFP) and/or Lewis lung cell 0.5×106 LLC or LLC-RFP tumor cells were subcutaneously (s.c.) injected in the flanks of mice. 1 million of Pancreatic cancer cell line KPC and LLC were injected in the contralateral flanks of C57BL/6 mice. Mice were pooled and randomly divided into different groups when tumors reached a volume of approximately 100 mm3 (L × W × H×0.5). Mice were treated with 20 Gy of tumor-localized ionizing radiation (one dose) or sham treatment. Lungs of the animals were harvested at the end point of the study (30 days post tumor implantation). For anti–PD-L1 treatment experiments, mice received 200 μg of anti–PD-L1 antibody injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) twice/ each week for a total of four times, starting on the day of irradiation. For anti-CCR2 treatment experiments, 45 μg/mouse was given in 4 doses (i.p.) every other day, starting on the day of irradiation. 50 μg/mouse of anti-CXCL10 was given via retro-orbital injection (i.v.) every other day, starting on the day of irradiation. Tumors were measured twice a week for 3–4 weeks. Animals were euthanized according to the endpoints approved by IACUC.

Flow cytometry

Tumor and lung tissues were cut into small pieces and digested by 1 mg/ml collagenase IV (Worthington) and 0.2 mg/ml DNase I (Sigma) for 1 hr at 37 °C. Single-cell suspensions were blocked with anti-FcR (2.4G2, BioXcell) and then stained with fluorescence-labeled antibodies. Flow cytometry was performed on BD LSR Fortessa or Cytek® Aurora at the Cytometry and Antibody Technology Core Facility of The University of Chicago and data were analyzed with FlowJo™ v10.8 Software (BD Life Sciences).

ELISA

Tumor tissues were homogenized in PBS with protease inhibitor at 1g/ml tissue to buffer ratio. Mouse serum was collected on day 20 post-tumor inoculation or at indicated times. The concentration of CXCL10 was measured with the IP-10 (CXCL10) Mouse ELISA Kit (BMS6018, Thermofisher). Patient sera was analyzed using the Human CXCL10/IP10 ELISA kit (R&D, DIP100). (26).

ELISPOT assay.

MC38 or LLC tumor cells were irradiated (40 Gy) and cultured overnight. CD8+T cells were isolated from DLNs of tumor-bearing mice on day 8 after treatment, using EasySep mouse CD8+ positive selection kit (18953, STEMCELL Technologies). Isolated CD8+ T cells (2 × 105) and 2 × 104 irradiated MC38 cells plus 2 × 105 splenocytes of naïve mice were plated onto 96-well polyvinylidene difluoride–backed microplates coated with monoclonal antibody specific for mouse IFN-γ, and cultured for 72 hours. Spots were developed by following the manufacturer’s protocol (BD Biosciences) and counted using CTL ImmunoSpot Analyzer at the core facility at The University of Chicago.

Cytokine/chemokine assay.

Whole tumors and lungs were excised, and serum was collected at the indicated time points after treatment. Tumors were weighed and homogenized in PBS with the presence of protease inhibitor cocktails at a ratio of 1 ml/g of tissue. Twenty-five microliters of supernatants or serum were subjected to bead-based cytokine and chemokine assays (LEGENDplex mouse inflammation panel and chemokine panel). The assays were analyzed using a LSRII flow cytometer and LEGENDplex software.

Real-time PCR assay.

mRNA from sorted immune cells from treated tumors was isolated using RNeasy Plus Kit (74136, Qiagen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthesized from pd(N)6-primed mRNA reverse transcription using M-MLV superscript reverse transcriptase. Real-time PCR kits (SYBR Premix Ex TaqTM, DRR041A) were purchased from Takara Bio Inc. PCR was performed using a CFX96 (Bio-Rad). mRNA specific for the housekeeping gene GAPDH was measured and used as an internal control. The primers used were:

-

CXCL10: 5’ CCAAGTGCTGCCGTCATTTTC (forward)

5’GGCTCGCAGGGATGATTTCAA (reverse);

-

GAPDH: 5`- AGA CCA GCC TGA GCA AAA GA −3` (forward)

5`- CTA GGC TGG AGT GCA GTG GT −3` (reverse).

-

FLT3: 5’- GAGCGACTCCAGCTACGTC −3’(forward)

5’- ACCCAGTGAAAATATCTCCCAGA −3’(reverse).

-

RAC1: 5’- GAGCGACTCCAGCTACGTC – 3’(forward),

5’- ACCCAGTGAAAATATCTCCCAGA −3’ (reverse).

Bone marrow cell induction and treatments.

Bone marrow cells were harvested from femur and tibia bones of mice and cultured in RPMI with the presence of 20 ng/ml of GM-CSF for 5 days before co-culture with recombinant CXCL10 at indicated concentrations. Three days later, the cultures were stained with antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Imaging of lung metastasis.

At the end of the animal studies involving LLC tumors, animals were euthanized and lungs were perfused and harvested. The lungs were fixed in 10% formaline, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned. All tissues were placed in a consistent position and sections were made from the surface and middle of the tissue, and then stained with Hemoxylin/eosin. The stained slides were scanned using an Olympus VS200 Slideview at the Integrated Light Microscopy facility of The University of Chicago, and then viewed and quantified using Qupath software (35).

RNAseq and analysis.

MC38/LLC tumors were established and MC38 tumors were irradiated. Lung tissue was collected 3 days post-IR, and CD45+ cells were sorted from single-cell suspension. mRNA cDNA libraries were made using SMARTer Stranded Total RNA-Seq Kit v2 - Pico Input Mammalian kit and sequenced using Illumina HiSEQ4000 at the Genomics Facility of The University of Chicago.(36) Raw sequence reads (75bp, single end) of each sample were in the range of ~30M to 40M. The raw reads were filtered with average quality score greater than 30, and mapped to mouse reference genome (mm10) using STAR with --chimSegmentMin 20--outFilterMultimapNmax 20 --outFilterMismatchNmax 2 options. The gene expression matrix was generated by htseq. Differentially-expressed genes were identified by the Bioconductor package edgeR (with FDR < 0.05 and absolute fold change > 1.5). PCA plot and heatmaps were generated by the Genomics Suite of Partek software package version 7.19. Enriched pathways were generated by enrichKEGG function of the clusterProfiler package. GO biological process analysis was performed using the enrichGO function of the clusterProfiler package.

Statistical analysis.

Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software 9. Data were analyzed by 2-way ANOVA with Multiple Comparison Test (tumor growth curves and other group analysis) or Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test (patient matched samples), or Mann-Whitney test. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data are presented as means ± SEM.

Data and materials availability.

All data associated with this study are present in the paper or the Supplementary Materials. RNAseq data generated in this study are publicly available in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE230368

RESULTS

Radiation fails to control distal tumor growth or primary tumor metastasis despite enhanced T-cell response.

To investigate whether IR mediates an anti-tumor effect outside of the irradiated field, we employed a contralateral flank tumor model using MC38 syngeneic colon cancer cells in C57BL/6 mice (MC38/MC38). The irradiated tumors are designated as local tumors, and the unirradiated contralateral tumors are designated as distal tumors. A single dose of 20 Gy effectively controlled local tumor growth (Fig. 1A); however, IR failed to mediate distal tumor regression (Fig. 1B). Because T-cell (CD8+) response is critical to the anti-tumor effects of IR (10,37), we examined T-cell response in the local and distal tumor draining lymph nodes (DLN) and observed augmented priming of tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in both sides of hosts that received local tumor IR, compared with non-irradiated controls (Fig. 1C). In addition, frequencies of IFNγ- and granzyme-B-expressing CD8+ T cells were increased in distal tumors following local tumor IR, compared with those of non-irradiated controls (Fig. 1D). Since flank MC38 tumors never metastasize, to study abscopal effect in metastasis, we implanted LLC tumors in the flanks of mice; LLC tumors spontaneously metastasize to the lung within 30 days of primary tumor inoculation. Local irradiation of local LLC tumors inhibited local tumor progression (fig. S1A). At 30 days post-tumor inoculation, lungs were processed by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, and metastases were quantified. The number of spontaneous metastases in lung (distal) was not reduced in irradiated mice compared with non-irradiated control (Fig. 1E). These results suggested that despite significant augmentation of the anti-tumor CD8+ T-cell response in distal tumors following local IR, the potential abscopal effect of IR is possibly masked by other suppressive factor(s). We hypothesized that local IR unleashes both positive (i.e., anti-tumor adaptive T-cell responses) and suppressive factors, and the balance of these factors determines the outcome of systemic effects of IR.

Figure 1.

Abscopal effect of ionizing radiation. A-D. Phenotype of MC38/MC38 tumors. Growth of irradiated local tumors (A) and untreated distal tumors (B). C. IFNγ producing CD8+ T cells from local and distal draining lymph nodes in ELISPOT assays. D. Frequencies of IFNγ and granzyme B expressing CD8+ T cells in tumors. E. Number of spontaneous lung metastasis nodules when primary LLC tumors received indicated treatments. F. Tumor grwth curve of MC38 (received treatments). G. Tumor growth curve of distal tumors (LLC). H. Spontaneous metastasis in lung of LLC mice. I. Quantification of area of metastasis in lungs 30 days after cancer cell transplantation. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001, ****, p<0.0001. A, B, F, G, N=5, 2-way ANOVA; C-D, N=3–4, t-test assuming unequal variance. E, N=11–13; I, N=5–10, t-test assuming unequal variance; Experiments were repeated 3 times.

Heterologous two-tumor model reveals that RT-induced immunosuppressive factors promote distal progression.

To validate the hypothesis that IR may trigger tumor- and metastasis-promoting mechanisms that are obscured by adaptive T cell response or concomitant immunity (in the 2-tumor model in which same tumors were implanted on both flanks), we established a heterologous two-tumor model featuring two different tumors implanted on contralateral flanks of a single mouse (MC38/LLC model) in which the positive anti-tumor T-cell response (concomitant immunity) is likely absent/reduced. The MC38 tumor received IR or non-IR treatment, and tumor progression of the contralateral tumor (LLC) as well as spontaneous lung metastasis of LLC were evaluated. Since two heterologous tumors were implanted, we verified the origin of lung metastasis. By flow cytometry of lungs of hosts with MC38-GFP/LLC-RFP tumors (Fig. S1B) and q-PCR analysis to determine the expression of genes that are differentially expressed in MC38 and LLC cell lines (Fig. S1C), we determined that the metastatic tumor cells in lung are most likely LLC cells. IR controlled the MC38 tumor growth (Fig. 1F) but promoted progression of distal flank LLC tumors (Fig. 1G). Thirty days (30 d) following tumor implantation, LLC lung metastases were evaluated. We found that IR delivered to MC38 tumors promoted the development of lung metastasis of the distal LLC tumors (Fig. 1H), in both number of metastatic nodules (Fig. 1I) and percentage of metastasis area in total lung (fig. S1D). The significant promotion of outgrowth of the contralateral distal tumor by irradiating primary local tumors was observed in an MC38/B16F10 heterologous two-tumor model as well (fig. S1E). In addition, we setup another heterologous two-tumor model using pancreatic KPC (derived from PDAC GEMM) tumor as primary local tumor and LLC as distal tumor. KPC tumor (irradiated) growth was inhibited by radiation (Fig. S1F), whereas distal LLC (unirradiated) growth was increased by radiation (Fig. S1G), The spontaneous LLC lung metastasis in terms of number of nodules or metastasis area were also increased in the mice received radiation to KPC tumors (Fig. S1H–J). These results demonstrated that local IR can promote tumor growth and metastasis of distal unirradiated tumors in a model in which the impact of concomitant immunity (antigen-specific) has been absent.

Radiation induces PD-L1 expression and MDSC infiltration in distal tumors and lung.

To detect changes in patterns of gene expression in distal tissue post-IR, we performed bulk RNA-Seq of CD45+ cells isolated from the lungs of mice in which local tumors were treated with irradiation or sham-IR. Sequencing analysis showed that 3 days following IR, 307 genes were differentially expressed in cells from mice that received irradiation compared with those from sham-treated mice. These genes include 208 upregulated genes and 99 down-regulated genes (fig. S2A and S2B). Gene Set Enrichment analysis (GSEA) revealed increases in pathways involved in interferon/TNF signaling, reactive oxygen species, and JAK-STAT3 signaling, which are involved in PD-L1 induction in cancer (38) (Fig. 2A and fig. S2C). These findings supported the hypothesis that IR induces both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory immune responses in distal tissue. House-keeping pathways involved in MYC targets, EMT, and cell proliferation, which are crucial in metabolic programs, migration, and cell cycle, respectively, were decreased in CD45+ cells following IR (fig. S2D). Further analysis demonstrated that IR increased the expression of an MDSC signature (39) in CD45+ cells within the lungs (Fig. 2B), suggesting enhanced immune suppression in the lungs following local IR. Gene Ontology (GO) analysis demonstrated that the top increased pathways post-IR were cell chemotaxis, migration, inflammation regulation, and cytokine-mediated pathways (fig. S2E). Taken together, these results suggested that local IR promoted systemic immune suppression partly by increasing PD-L1 expression and MDSC recruitment.

Figure 2.

MDSC frequencies in myeloid cells and PD-L1 expression in irradiated local tumors, unirradiated distal tumors, and lungs compared with unirradiated local control. A, B. RNAseq analysis of CD45+ cells isolated from lungs of animals treated as indicated 3 days after irradiation of local tumors (MC38). A. Representative enriched pathways in CD45+ cells of lungs of irradiated animals. B. Differential expression of genes (DEG) of MSDC scores in different treatments. X-axis: Log2 of fold change (FC) between each DEG. Y-axis: DEGs. Gene (Y-axis): DEGs among MDSC signature genes. C, D. MDSC population of local and distal tumors. E. MDSC population in lung 7 days post-IR in homologous 2-tumor models. F-H. PD-L1 expression of CD11C+DC, macrophage, M-MDSCs in irradiated (local) tumors, untreated (distal) tumors, and lungs in homologous 2-tumor models. I. PD-L1 expression in MDSCs and DCs of patients’ PBMC pre- and post- SBRT in clinical trial NCT03223155. C, D, N=4; E, N=6–8; F-H, N=3. Experiments were repeated 3 times. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ****, P<0.0001. Statistics: C-H, Mann-Whitney test. I, N=27, paired t-test.

We and others have previously demonstrated that Monocytic-MDSCs (M-MDSCs, CD11b+Ly6C+) are recruited into the tumor microenvironment by local IR (23) (20). Here, we found that local IR also led to an increase of MDSC infiltration in the distal tumors and host lungs (Fig. 2C–E). We and others have reported that IR induced PD-L1 expression in tumor-associated myeloid cells such as DCs in irradiated tumors (26,40). We investigated PD-L1 expression in unirradiated distal sites. As shown in Fig. 2 F–H, 3 days following IR to the local tumors, we observed increased expression of PD-L1 on the surface of CD11c+(DCs), CD11b+F4/80+(macrophages), and CD11b+Ly6C+(M-MDSC) cells in irradiated local tumors, unirradiated distal tumors, and lungs when compared with untreated controls (hosts received sham-IR). This increase was consistent in both the MC38/MC38 and MC38/LLC two-tumor models (Fig. 2 and fig S2F). In addition to tumors and lungs, we analyzed the PBMCs of the MC38/LLC two-tumor hosts at 3 days post IR. PD-L1 expression on cDCs increased in irradiated hosts compared to that of unirradiated hosts (Fig. S2G, left). Similarly, circulating MDSCs were also increased 3 days post IR in PBMCs (Fig. S2G, right).

Radiotherapy induces systemic changes of PD-L1 expression and MDSC mobilization.

We conducted a phase I clinical trial NCT03223155 at our institution (34) that indicated that pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1) significantly improved overall survival and progression-free survival of patients who also received SBRT. We analyzed PBMCs from patients in the trial with metastatic solid tumors treated with multi-site SBRT followed by immunotherapy. Blood samples were collected prior to and following SBRT (median interval between blood draws = 26 days). There are 34 patients initially enrolled(34,41), among them match-paired blood samples were available for 30 patients. We used ROUT analysis to identify outliers (Q=10%) and the patients with any outlier value were removed from analysis. As reported in Wang, et al. (42), we stratified the patients by their differential responses to treatments in terms of progression of distal unirradiated lesions: responder = lack of progression or time to progression > 8 months; non-responder = time to progression < 8 months. We found that the MDSC proportion of PBMCs increased significantly in non-responders following SBRT as compared with pre-SBRT levels. Similar increase was not found in PBMC of responders. The PD-L1/PD-1 checkpoint represents the most studied immune parameter in immunotherapy. We further analyzed PD-L1 expression in myeloid and DCs responding to RT in all available patient samples according to the time to progression of distal lesions (as above). We observed that PD-L1 expression on MDSCs and DCs was significantly induced by RT in the PBMCs of all patients analyzed (27 patients for MDSCs, 30 for DCs) regardless of their outcome (Fig. 2I, fig. S3A, and S3B). These results indicate that RT mobilizes systemic immunosuppressive myeloid cells, and this is associated with metastatic disease progression. In addition, RT also induces a systemic increase in PD-L1 expression on myeloid cells, which could be a target to improve abscopal effects.

Taken together, these results suggested that IR indeed initiates systemic PD-L1 induction and MDSC mobilization in both pre-clinical and clinical settings.

STING/IFN-I signaling is required for radiation-induced PD-L1 in distal sites.

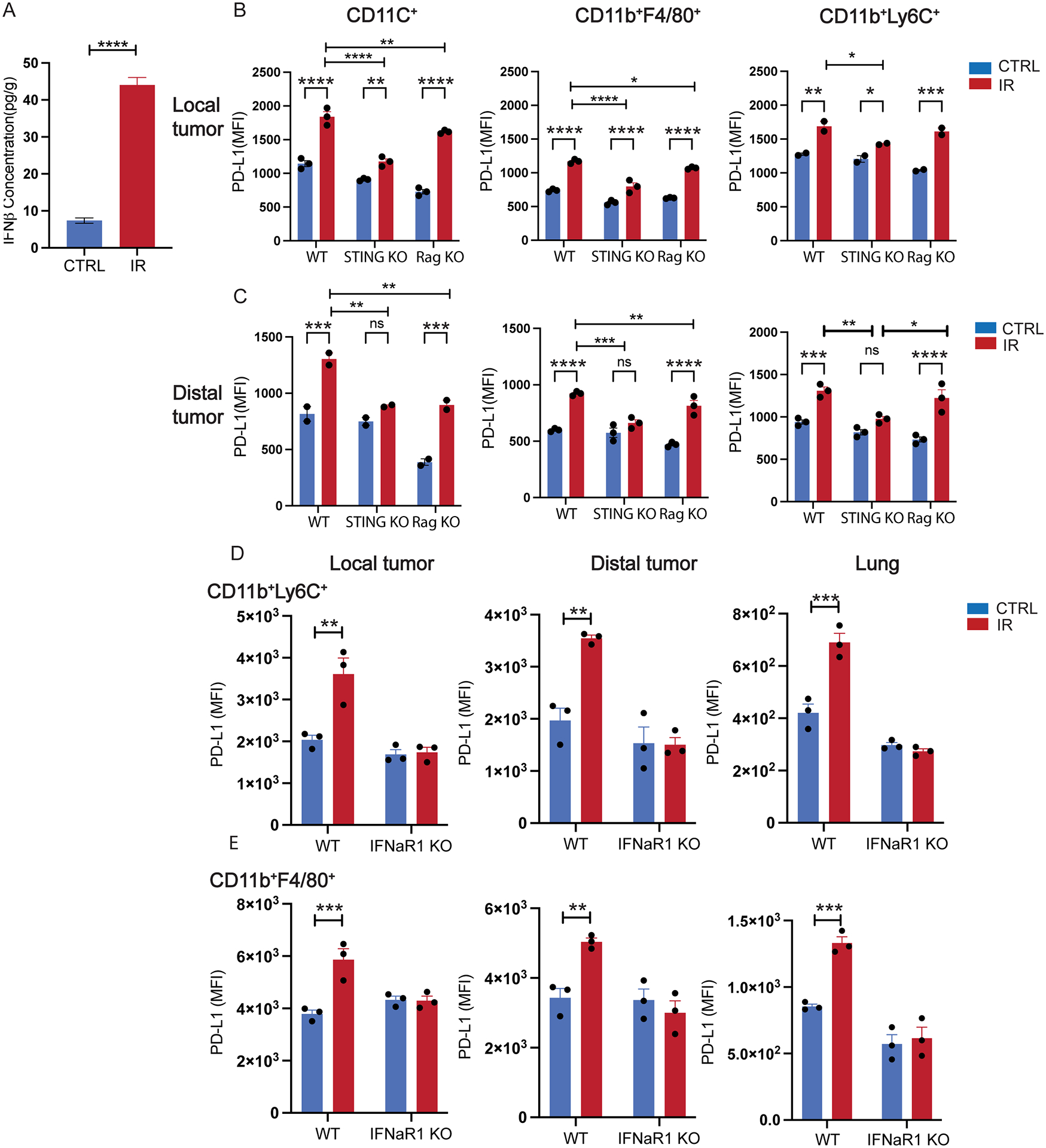

Next, we sought to investigate the mechanism by which PD-L1 was systemically induced. By utilizing a multiplexed assay, we observed changes in cytokine and chemokine concentrations in local and distal tumors as well as the lung and serum, three days following IR (fig. S4A and S4B). Among these, protein levels of IFN-I in irradiated tumors were significantly increased in local tumors (Fig. 3A and fig. S5A). It has been reported that activation of the STING and IFN-I signaling pathway promote PD-L1 expression in myeloid cells (40,43). We hypothesize that STING and IFN-I signaling are required for PD-L1 induction by IR in distal tissues. Using STING−/− mice (STING KO), we observed a significant albeit attenuated PD-L1 induction in myeloid cells in locally irradiated tumors, including CD11c+ DCs, CD11b+Ly6C+ M-MDSCs, and F4/80+ macrophages (Fig. 3B). However, in distal tumors, induction of PD-L1 expression in these STING KO cells by IR was diminished (Fig. 3C). To determine whether T cells or B cells are required for PD-L1 induction by IR, local tumors of 2-tumor model implanted in Rag1−/− mice were irradiated. The results demonstrated that the induction of PD-L1 was not T-cell- or B-cell-dependent, given the significant increases of PD-L1 expression in subsets of myeloid cells were observed in distal tumors in Rag1−/− mice following local IR (Fig. 3B, C). Similar to the observation in STING KO, the increase of PD-L1 expression of myeloid subsets in IFN-I receptor-deficient mice (IFNαR1−/−, IFNαR1 KO) was completely abolished following IR in local, distal tumors and lungs (Fig. 3D, 3E, and fig. S5B), compared with those of WT mice. These results demonstrated that the IR induction of PD-L1 expression in distal sites requires STING/IFN-I signaling.

Figure 3.

RT-induced systemic PD-L1 expression in myeloid cells depends on STING and type I IFN signaling but not T cells. A. IFNβ concentration in irradiated (local) tumors post 20 Gy of local irradiation. B. PD-L1 expression on various myeloid cells in irradiated local tumor in WT, STING KO, and RAG KO mice. C. PD-L1 expression on various myeloid cells in un-irradiated distal tumor in WT, STING KO, and RAG KO mice. PD-L1 expression of Ly6C+ cells (D) and macrophages (E) of local tumors, distal tumors, and lung tissue in WT and IFNαR KO mice. N=3–4; *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001; ****, P<0.0001. A, B, C, analyzed by 2-way ANOVA. B, D, E were analyzed by t-test assuming unequal variance. Experiments were repeated 3 times.

CXCL10 mediates PD-L1 expression in irradiated local tumors and distal lung.

Given that local irradiation leads to distal changes (outside of the irradiated field), next we sought to identify the signal (molecule) that may be responsible for mediating the effect of local irradiation of the distal tissue/tumor. First, we measured changes in IFNβ expression, which is one of the key components in activation of STING/IFN-I pathway. Despite a significant increase of IFNβ concentration in irradiated local tumors (Fig. 3A), we observed no increase in distal tumors, lung, or especially serum (fig. S5B). By contrast, we observed a significant increase of CXCL10 in the primary tumors and serum of mice in which the primary tumor was irradiated (Fig. 4A, fig. S4B, fig. S6A). In addition, in sera collected from patients enrolled in the clinical trial of SBRT+ICB at our institution (34), CXCL10 concentration was significantly increased following SBRT (post-SBRT) compared with that of pre-SBRT (34) (Fig. 4B). Known as an interferon-responsive chemokine (44), expression of CXCL10 is activated by innate immunity. Since STING/IFN-I signaling plays a central role in innate immunity, we examined CXCL10 concentration in serum of STING- or IFNαR1 KO mice. CXCL10 was not induced in either KO mice following local tumor irradiation, compared with levels in WT mice (Fig. 4C). To determine whether CXCL10 signaling was required for the induction of PD-L1 by IR, we utilized CXCL10 receptor CXCR3 knockout (CXCR3 KO) mice. We implanted MC38 tumors in each flanks of mice and examined PD-L1 expression on the surface of myeloid cells in distal tumors and the lungs 3 days following local tumor irradiation. Compared with the significant increase of PD-L1 expression in DCs from WT lung, PD-L1 expression did not change in the lungs of DCs deficient of CXCR3 (Fig. 4D). These results demonstrated that CXCL10 could be a signal mediating PD-L1 induction by IR in distal tissue, via STING/IFN-I activation. The results also showed that CXCR3 signaling is required for IR-induced PD-L1 expression in DCs.

Figure 4.

CXCL10 is the key regulator of PD-L1 expression in myeloid cells in distal tissue. A. CXCL10 concentration in mouse serum 3 days post-IR. B. Serum CXCL10 concentration pre- vs. post-radiotherapy in lung cancer patients. C. Serum CXCL10 concentration in mice 3 days post local tumor irradiation. D. DC PD-L1 expression in lungs of WT and CXCR3 KO mice 3 days after primary tumor irradiation. E. PD-L1 expression in WT or CXCR3 KO BMDC co-cultured with 0 and 5ng/ml concentration of rCXCL10. F. qPCR quantification of mRNA level of CXCL10 in tumor-associated immune cells 2 days post-IR. G. PD-L1 expression post-IR on CD11C+MHCII+ DC cells of lungs as fold over un-treated control. A, N=6–7; Mann-Whitney test. C-F, N=3–6; 2-way ANOVA. B, N=13; Wilcoxon test. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001; ***, P<0.0001. Mouse experiments were repeated 3 times.

CXCL10 is not an exclusive ligand for CXCR3; other ligands of CXCR3 could also be contributing to PD-L1 induction. Therefore, we tested whether CXCL10 is sufficient to induce PD-L1 expression. In bone marrow-derived DCs, we observed that exogenous CXCL10 induces PD-L1 expression in WT bone marrow-derived myeloid cells (BMDMs), but not in CXCR3 KO BMDMs (Fig. 4E). To determine whether CXCL10 mediates STING/IFN-I-dependent PD-L1 expression, we examined PD-L1 expression in STING KO and IFNαR KO BMDM cells co-cultured with CXCL10 (fig. S6B). The results indicate that exogeneous CXCL10 partially rescued the PD-L1 induction in STING KO and IFNαR KO (BMDM). Neutralizing CXCL10 using anti-CXCL10 antibody diminished the IR-induced PD-L1 expression in DCs of distal lung tissue (fig. S6C). Analysis of expression data derived from the TCGA-LUAD (Lung adenocarcinoma) cohort indicated that the expressions of CXCL10 and PD-L1 (CD274) were highly correlative (p=0; R=0.48; fig. S6D). These results suggested that IR-induced CXCL10 production mediates systemic increases of PD-L1 expression on myeloid cells. To determine the subpopulation of immune cells in which IR-induced CXCL10 occurs, we analyzed CXCL10 mRNA levels in major subsets of tumor-associated myeloid cells and found the induction was predominantly in CD11b+Ly6C+ MDSCs following IR (Fig. 4F). Depletion of CD11b+Ly6C+CCR2+ MDSCs using anti-CCR2 antibody (23) abolished the PD-L1 induction in lung-associated DCs following IR (Fig. 4G). Taken together with our earlier observation of IR-induced MDSC infiltration in local tumors and lungs of irradiated hosts, these findings suggested that, by producing CXCL10, MDSCs could be one of the main contributors of IR-induced PD-L1 expression in distal tissues.

To determine whether CXCL10 contributes to IR-induced immunosuppression that results in increased metastasis in vivo, we neutralized CXCL10 by using anti-CXCL10 antibody in the heterologous two-tumor model. Anti-CXCL10 further inhibited growth of irradiated MC38 tumors (Fig. 5A). CXCL10 neutralization inhibited the growth of distal tumors (LLC) and slowed tumor growth to a level similar to untreated controls (Fig. 5B). More importantly, CXCL10 neutralization significantly reduced the number and area of lung metastasis of distal LLC (Fig. 5C and 5D; fig. S6E). These results demonstrated that CXCL10 plays a central role in promoting metastasis by augmenting the suppressive effect of IR, likely through inducing PD-L1 expression in myeloid cells, such as DCs.

Figure 5.

Neutralizing CXCL10 inhibits tumor growth and lung metastasis of untreated tumors. A. Growth of treated MC38. B. Growth of distal tumor (LLC). C, D. Number of spontaneous lung metastasis of distal LLC tumor. E. Number of lung metastasis. N=5 for A, B. The experiments were repeated 3 times. N=9–10 for D. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, P<0.001; A, B, 2-way ANOVA; D, Mann-Whitney test.

Blockade of PD-L1 and MDSCs abrogates local IR-induced metastasis.

To determine whether PD-L1 or MDSC blockade can eliminate the immune suppression that leads to tumor progression and metastasis, we blocked the PD-L1/PD-1 axis by using anti-PD-L1 antibody in the heterologous two-tumor model (MC38/LLC) and monitored the growth of untreated tumors and lung metastasis. The enhanced growth rate of distal tumors induced by local IR was reduced to a rate similar to untreated (MC38) control by anti-PD-L1 treatment in IR + anti-PD-L1 combination (Fig. 6A). Lung metastasis of LLC tumor was significantly increased by local MC38 radiation. IR+anti-PD-L1 combination treatment reduced metastasis significantly to the level of untreated control, compared with IR alone treatment (Fig. 6B, 6C and fig. S7A left). In addition, blocking MDSC in the heterologous two-tumor model inhibited distal LLC tumor growth (Fig. 6D) and reduced lung metastasis significantly in mice treated with IR+anti-CCR2 as compared with IR alone, reversing the effect of IR in promoting metastasis in this model (Fig. 6E and 6F, and fig. S7A, right). These results demonstrated that IR-induced PD-L1 expression and MDSC infiltration are key factors of immune suppression affecting distal responses. We hypothesize that when used in the homologous two-tumor or 1-tumor metastasis model, PD-L1 or MDSC blockade will exert similar effects. Therefore, we utilized a homologous two-tumor model (MC38/MC38) and a 1-tumor LLC tumor model; tumors were treated with IR+anti-PD-L1. IR can significantly control local tumor growth and the addition of anti-PD-L1 blockade resulted in enhanced IR effects on tumor control for both irradiated and unirradiated MC38 tumors (fig. S7B and S7C). Radiation also led to higher levels of tumor antigen-specific T-cell priming in draining lymph nodes of both tumors, as evidenced by increased IFNγ production (fig. S7D and S7E). Combining anti-PD-L1 with IR also significantly reduced the metastasis of LLC tumors in the lungs compared with any single treatment alone in which 1-sided LLC flank tumors were treated (Fig. 6G). The combination treatment increased the percentage of metastasis-free mice to 60%, compared with 0%,10% and 0% metastasis-free in ctrl, IR and anti-PD-L1 single treatment groups, respectively (Fig. 6H). Similarly, blockade of MDSCs using anti-CCR2 antibody following IR decreased spontaneous lung metastasis of LLC tumors, compared to ctrl or IR treatment alone (Fig. 6I). Taken together, combining IR with anti-PD-L1 or anti-CCR2 (MDSC depletion) not only reversed the increased lung metastasis of LLC tumor in distinct two-tumor models, but also inhibited the lung metastasis of irradiated LLC flank tumors.

Figure 6.

PD-L1 and CCR2 blockade abrogates local IR-induced systemic pro-tumor responses. A. Growth curve of distal tumor (LLC) in heterogeneous 2-tumor model. B. H&E staining of lungs of which primary MC38 tumors were treated as indicated. C. Number of metastasis in a lung of which primary MC38 tumors were treated with IR and/or anti-PD-L1. D. Growth of LLC distal tumors with indicated treatments. E. H&E staining of lungs of which primary MC38 tumors were treated with IR and/or anti-CCR2. F. Number of metastasis in a lung. G, H, I. LLC primary tumors were treated as indicated and lung nodules were counted via H&E staining. A and D, N=5. A, D, F and I, experiments were repeated 3–4 times. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001. ****, P<0.0001. A, and D by 2-way ANOVA analysis; C, F, G, and I by Mann-Whitney test.

Here, utilizing a heterologous two-tumor model as proof-of-principle, we report that in the absence of concomitant immunity, the effects of IR that are deleterious to anti-tumor immunity can be revealed and studied. We report that IR leads to immunosuppression, which contributes to tumor progression and increased metastasis. Radiation of a single local tumor caused systemically elevated PD-L1 expression in myeloid cells via activated STING/IFN-I pathway; and the increased tumor growth and metastasis in distal sites were mediated by CXCL10 expression. Blocking the PD-L1/PD-1 axis, blocking MDSC migration, or neutralizing CXCL10 can attenuate immunosuppression, improving the efficacy of IR in the treatment of local tumors and metastasis (fig. S8).

DISCUSSION

Through analysis of data from radiotherapy patients treated on a clinical trial and validation in multiple murine model systems treated with IR, we have identified a previously unknown induction of the IR/CXCL10/PD-L1 axis that promotes metastatic spread. The clinical implication of this finding is that patients undergoing RT who are not currently eligible for immune checkpoint blockade due to absent or very low levels of PD-L1 expression should be tested for PD-L1 induction by RT. In addition, this induction is relevant not only in local irradiated tumor, but also systemic PD-L1 expression, such as in peripheral blood, and therefore should be taken into consideration in treatment planning since our data indicate PD-L1 induction by IR may mediate tumor metastasis. PD-L1 blockade under these conditions could prevent the potential enhancement of RT-induced metastatic spread. MDSCs also contribute to radioresistance (reviewed in (20,45)). Based on our preclinical and clinical observations, targeting increased MDSC mobilization would be another viable strategy to augment local and abscopal responses to radiotherapy.

This study focused on the immunosuppressive function of myeloid cells induced by local RT. A recent report supports our hypothesis that RT induced MDSC-mediated lymphopenia in preclinical and clinical GBM cancer (16). Transformations of local and systemic immunity elicited by radiation are multifaceted. Our results cannot rule out the involvement of additional immune-mediated mechanisms dependent on NK or B cells. The nature of MDSC response to various therapies is likely to be complex depending on treatment, cancer type, or animal model (reviewed in (46)). Chemoradiation treatment of cervical cancer patients increased circulating MDSCs (47), whereas in a mouse model of head and neck cancer, chemoradiation resulted in a decrease of MDSCs (48).

CXCL10 is identified as one of the critical chemoattractants for T-cell infiltration. It is suggested that CXCL10 levels are associated with T-cell infiltration, and as such, anti-tumor immunity (31). Our analysis of patient serum showed that the concentration of CXCL10 increased post-RT in almost all patients regardless of their clinical outcome. This result implies that mediating T-cell infiltration is unlikely the sole function of CXCL10. A study analyzing the transcriptome of 182 pancreatic adenocarcinoma patients indicated that CXCL10 expression is negatively correlated with patient outcomes (49). A similar conclusion was drawn in a lung cancer patient study with 144 patients; patients with elevated CXCL10 levels in serum had significantly poorer outcomes than those with lower levels in terms of overall survival and cancer-specific survival (50). Although CXCL10 is expressed in myeloid cells, very little is known about its role in systemic anti-tumor immunity. A recent report indicates that CXCL10 produced by brain resident microglia facilitate metastasis (32). The potential role of CXCL10 in promoting metastasis in response to various cancer treatments warrants further study. We speculate that CXCL10 plays distinct and maybe opposite roles depending on immunogenicity of tumors: enhancing anti-tumor immunity in “hot” tumors such as melanoma; and pro-tumor progression in “cold” tumors such as brain and pancreatic cancers. In this sense, when treating cold tumors, blocking CXCL10 may be beneficial when combined with T cell checkpoint inhibitors.

Limitations:

One limitation of this report is that the irradiated murine and human tumors received a relatively high single dose of radiation (SBRT); no fractionated treatments were utilized. Further, the heterologous two-tumor model is only a proof-of-principle tool. We cannot rule out the effects of other immunosuppressive factors induced by RT on dampening abscopal effects. This study was not designed to address the effect of radiation on promoting cancer stem cell migration which could be additional mechanism of radiation induced tumor metastasis. Different type of resistance may be employed by different cancer types. Finally, for the many patients for whom radiotherapy is by some measure effective, the cytoreductive effects of RT may compensate for the induction of PD-L1 and other immunosuppressive factors.

We have uncovered an initial clue; the connection between RT-induced myeloid changes, MDSC mobilization, and PD-L1 expression is still not fully understood. However, our report suggests that known clinical reagents (immune checkpoint inhibitors) might abrogate the metastasis-promoting effects of RT in some cases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

Funding:

National Institutes of Health grant R21CA226582 (to R. Weichselbaum).

National institutes of Health grant R01CA262508 (to R. Weichselbaum).

National institutes of Health grant U54 CA 274291(R. Weichselbaum)

The Chicago Tumor Institute, an endowment from the Ludwig Cancer Research Foundation (R. Weichselbaum).

National Natural Science Foundation of China 82273194 and 82073176 (Y. Hou)

Clinical Therapeutics Training Grant T32GM007019 and National Cancer Institute K12CA139160 (J. Bugno)

German Research Foundation Walter Benjamin scholarship (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft - DFG- project nr. 455353745)(A. Piffko)

University of Chicago Cancer Research Center fund P30CA014599 (Core facilities at University of Chicago)

We wish to thank Amy K. Huser for editing the manuscript. We thank Rolando Torres for irradiating the mice. We thank the University of Chicago Human Tissue Resource Center (RRID:SCR_019199), Animal Studies Core (P30CA014599), Microscopy Core (P30CA014599), Flow Cytometry Core (RRID:SCR_017760), and Genomics Facility (RRID:SCR_019196).

Abbreviations list:

- PD-L1

Programmed death-ligand 1

- MDSC

Myeloid derived suppressor cell

- CXCL10

C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10

- STING

Stimulator of interferon genes

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement:

RRW has stock and other ownership interests with Boost Therapeutics, Immvira, Reflexion Pharmaceuticals, Coordination Pharmaceuticals, Magi Therapeutics, Oncosenescence. He has served in a consulting or advisory role for Aettis, Astrazeneca, Coordination Pharmaceuticals, Genus, Merck Serono S.A., Nano proteagen, NKMax America, Shuttle Pharmaceuticals, and Persona Dx. He has a patent pending entitled “Methods and Kits for Diagnosis and Triage of Patients with Colorectal Liver Metastases” (PCT/US2019/028071). He has received research grant funding from Varian and Regeneron. He has received compensation including travel, accommodations, or expense reimbursement from Astrazeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Merck Serono S.A. RRW and HLL have a patent pending: PCT/US23/81165 “METHODS FOR TREATING CANCER WITH IMMUNOTHERAPY”.

The remaining authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.North RJ. Radiation-induced, immunologically mediated regression of an established tumor as an example of successful therapeutic immunomanipulation. Preferential elimination of suppressor T cells allows sustained production of effector T cells. J Exp Med 1986;164(5):1652–66 doi 10.1084/jem.164.5.1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teitz-Tennenbaum S, Li Q, Okuyama R, Davis MA, Sun R, Whitfield J, et al. Mechanisms involved in radiation enhancement of intratumoral dendritic cell therapy. J Immunother 2008;31(4):345–58 doi 10.1097/CJI.0b013e318163628c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diamond JM, Vanpouille-Box C, Spada S, Rudqvist NP, Chapman JR, Ueberheide BM, et al. Exosomes Shuttle TREX1-Sensitive IFN-Stimulatory dsDNA from Irradiated Cancer Cells to DCs. Cancer Immunol Res 2018;6(8):910–20 doi 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-17-0581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lugade AA, Sorensen EW, Gerber SA, Moran JP, Frelinger JG, Lord EM. Radiation-induced IFN-gamma production within the tumor microenvironment influences antitumor immunity. J Immunol 2008;180(5):3132–9 doi 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.3132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walle T, Kraske JA, Liao B, Lenoir B, Timke C, von Bohlen Und Halbach E, et al. Radiotherapy orchestrates natural killer cell dependent antitumor immune responses through CXCL8. Sci Adv 2022;8(12):eabh4050 doi 10.1126/sciadv.abh4050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stary V, Wolf B, Unterleuthner D, List J, Talic M, Laengle J, et al. Short-course radiotherapy promotes pro-inflammatory macrophages via extracellular vesicles in human rectal cancer. J Immunother Cancer 2020;8(2) doi 10.1136/jitc-2020-000667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reynders K, Illidge T, Siva S, Chang JY, De Ruysscher D. The abscopal effect of local radiotherapy: using immunotherapy to make a rare event clinically relevant. Cancer Treat Rev 2015;41(6):503–10 doi 10.1016/j.ctrv.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hatten SJ Jr., Lehrer EJ, Liao, Sha CM, Trifiletti DM, Siva S, et al. A Patient-Level Data Meta-analysis of the Abscopal Effect. Adv Radiat Oncol 2022;7(3):100909 doi 10.1016/j.adro.2022.100909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nishiga Y, Drainas AP, Baron M, Bhattacharya D, Barkal AA, Ahrari Y, et al. Radiotherapy in combination with CD47 blockade elicits a macrophage-mediated abscopal effect. Nat Cancer 2022;3(11):1351–66 doi 10.1038/s43018-022-00456-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ngwa W, Irabor OC, Schoenfeld JD, Hesser J, Demaria S, Formenti SC. Using immunotherapy to boost the abscopal effect. Nat Rev Cancer 2018;18(5):313–22 doi 10.1038/nrc.2018.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turchan WT, Pitroda SP, Weichselbaum RR. Radiotherapy and Immunotherapy Combinations in the Treatment of Patients with Metastatic Disease: Current Status and Future Focus. Clin Cancer Res 2021;27(19):5188–94 doi 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-0145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pointer KB, Pitroda SP, Weichselbaum RR. Radiotherapy and immunotherapy: open questions and future strategies. Trends Cancer 2022;8(1):9–20 doi 10.1016/j.trecan.2021.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Antonia SJ, Villegas A, Daniel D, Vicente D, Murakami S, Hui R, et al. Durvalumab after Chemoradiotherapy in Stage III Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2017;377(20):1919–29 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa1709937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelly RJ, Ajani JA, Kuzdzal J, Zander T, Van Cutsem E, Piessen G, et al. Adjuvant Nivolumab in Resected Esophageal or Gastroesophageal Junction Cancer. N Engl J Med 2021;384(13):1191–203 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa2032125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodriguez-Ruiz ME, Vanpouille-Box C, Melero I, Formenti SC, Demaria S. Immunological Mechanisms Responsible for Radiation-Induced Abscopal Effect. Trends Immunol 2018;39(8):644–55 doi 10.1016/j.it.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghosh S, Huang J, Inkman M, Zhang J, Thotala S, Tikhonova E, et al. Radiation-induced circulating myeloid-derived suppressor cells induce systemic lymphopenia after chemoradiotherapy in patients with glioblastoma. Sci Transl Med 2023;15(680):eabn6758 doi 10.1126/scitranslmed.abn6758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qiao L, Chen Y, Liang N, Xie J, Deng G, Chen F, et al. Targeting Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Radioresistance: Crosslinked Mechanisms and Strategies. Front Oncol 2022;12:775238 doi 10.3389/fonc.2022.775238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rockwell S, Dobrucki IT, Kim EY, Marrison ST, Vu VT. Hypoxia and radiation therapy: past history, ongoing research, and future promise. Curr Mol Med 2009;9(4):442–58 doi 10.2174/156652409788167087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barker HE, Paget JT, Khan AA, Harrington KJ. The tumour microenvironment after radiotherapy: mechanisms of resistance and recurrence. Nat Rev Cancer 2015;15(7):409–25 doi 10.1038/nrc3958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jimenez-Cortegana C, Galassi C, Klapp V, Gabrilovich DI, Galluzzi L. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells and Radiotherapy. Cancer Immunol Res 2022;10(5):545–57 doi 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-21-1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin L, Kane N, Kobayashi N, Kono EA, Yamashiro JM, Nickols NG, et al. High-dose per Fraction Radiotherapy Induces Both Antitumor Immunity and Immunosuppressive Responses in Prostate Tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2021;27(5):1505–15 doi 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oweida AJ, Mueller AC, Piper M, Milner D, Van Court B, Bhatia S, et al. Response to radiotherapy in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma is enhanced by inhibition of myeloid-derived suppressor cells using STAT3 anti-sense oligonucleotide. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2021;70(4):989–1000 doi 10.1007/s00262-020-02701-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liang H, Deng L, Hou Y, Meng X, Huang X, Rao E, et al. Host STING-dependent MDSC mobilization drives extrinsic radiation resistance. Nat Commun 2017;8(1):1736 doi 10.1038/s41467-017-01566-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fu SY, Chen FH, Wang CC, Yu CF, Chiang CS, Hong JH. Role of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in High-Dose-Irradiated TRAMP-C1 Tumors: A Therapeutic Target and an Index for Assessing Tumor Microenvironment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2021;109(5):1547–58 doi 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu CT, Chen WC, Chang YH, Lin WY, Chen MF. The role of PD-L1 in the radiation response and clinical outcome for bladder cancer. Sci Rep 2016;6:19740 doi 10.1038/srep19740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deng L, Liang H, Xu M, Yang X, Burnette B, Arina A, et al. STING-Dependent Cytosolic DNA Sensing Promotes Radiation-Induced Type I Interferon-Dependent Antitumor Immunity in Immunogenic Tumors. Immunity 2014;41(5):843–52 doi 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rao E, Hou Y, Huang X, Wang L, Wang J, Zheng W, et al. All-trans retinoic acid overcomes solid tumor radioresistance by inducing inflammatory macrophages. Sci Immunol 2021;6(60) doi 10.1126/sciimmunol.aba8426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schonrich G, Raftery MJ. The PD-1/PD-L1 Axis and Virus Infections: A Delicate Balance. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2019;9:207 doi 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weichselbaum RR, Liang H, Deng L, Fu YX. Radiotherapy and immunotherapy: a beneficial liaison? Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2017;14(6):365–79 doi nrclinonc.2016.211 [pii] 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tu X, Qin B, Zhang Y, Zhang C, Kahila M, Nowsheen S, et al. PD-L1 (B7-H1) Competes with the RNA Exosome to Regulate the DNA Damage Response and Can Be Targeted to Sensitize to Radiation or Chemotherapy. Mol Cell 2019;74(6):1215–26 e4 doi 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reschke R, Yu J, Flood B, Higgs EF, Hatogai K, Gajewski TF. Immune cell and tumor cell-derived CXCL10 is indicative of immunotherapy response in metastatic melanoma. J Immunother Cancer 2021;9(9) doi 10.1136/jitc-2021-003521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guldner IH, Wang Q, Yang L, Golomb SM, Zhao Z, Lopez JA, et al. CNS-Native Myeloid Cells Drive Immune Suppression in the Brain Metastatic Niche through Cxcl10. Cell 2020;183(5):1234–48 e25 doi 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mack M, Cihak J, Simonis C, Luckow B, Proudfoot AE, Plachy J, et al. Expression and characterization of the chemokine receptors CCR2 and CCR5 in mice. J Immunol 2001;166(7):4697–704 doi 10.4049/jimmunol.166.7.4697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bestvina CM, Pointer KB, Karrison T, Al-Hallaq H, Hoffman PC, Jelinek MJ, et al. A Phase 1 Trial of Concurrent or Sequential Ipilimumab, Nivolumab, and Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy in Patients With Stage IV NSCLC Study. J Thorac Oncol 2022;17(1):130–40 doi 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bankhead P, Loughrey MB, Fernandez JA, Dombrowski Y, McArt DG, Dunne PD, et al. QuPath: Open source software for digital pathology image analysis. Sci Rep 2017;7(1):16878 doi 10.1038/s41598-017-17204-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang L, Dou X, Chen S, Yu X, Huang X, Zhang L, et al. YTHDF2 inhibition potentiates radiotherapy antitumor efficacy. Cancer Cell 2023;41(7):1294–308 e8 doi 10.1016/j.ccell.2023.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee Y, Auh SL, Wang Y, Burnette B, Wang Y, Meng Y, et al. Therapeutic effects of ablative radiation on local tumor require CD8+ T cells: changing strategies for cancer treatment. Blood 2009;114(3):589–95 doi 10.1182/blood-2009-02-206870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang X, Zeng Y, Qu Q, Zhu J, Liu Z, Ning W, et al. PD-L1 induced by IFN-gamma from tumor-associated macrophages via the JAK/STAT3 and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways promoted progression of lung cancer. Int J Clin Oncol 2017;22(6):1026–33 doi 10.1007/s10147-017-1161-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Veglia F, Sanseviero E, Gabrilovich DI. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the era of increasing myeloid cell diversity. Nat Rev Immunol 2021;21(8):485–98 doi 10.1038/s41577-020-00490-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hou Y, Liang H, Rao E, Zheng W, Huang X, Deng L, et al. Non-canonical NF-kappaB Antagonizes STING Sensor-Mediated DNA Sensing in Radiotherapy. Immunity 2018;49(3):490–503 e4 doi 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spurr LF, Martinez CA, Kang W, Chen M, Zha Y, Hseu R, et al. Highly aneuploid non-small cell lung cancer shows enhanced responsiveness to concurrent radiation and immune checkpoint blockade. Nat Cancer 2022;3(12):1498–512 doi 10.1038/s43018-022-00467-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang L, Dou X, Chen S, Yu X, Huang X, Zhang L, et al. YTHDF2 inhibition potentiates radiotherapy antitumor efficacy. Cancer Cell 2023. doi 10.1016/j.ccell.2023.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cheon H, Holvey-Bates EG, McGrail DJ, Stark GR. PD-L1 sustains chronic, cancer cell-intrinsic responses to type I interferon, enhancing resistance to DNA damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021;118(47) doi 10.1073/pnas.2112258118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buttmann M, Berberich-Siebelt F, Serfling E, Rieckmann P. Interferon-beta is a potent inducer of interferon regulatory factor-1/2-dependent IP-10/CXCL10 expression in primary human endothelial cells. J Vasc Res 2007;44(1):51–60 doi 10.1159/000097977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pitroda SP, Chmura SJ, Weichselbaum RR. Integration of radiotherapy and immunotherapy for treatment of oligometastases. Lancet Oncol 2019;20(8):e434–e42 doi 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Salas-Benito D, Perez-Gracia JL, Ponz-Sarvise M, Rodriguez-Ruiz ME, Martinez-Forero I, Castanon E, et al. Paradigms on Immunotherapy Combinations with Chemotherapy. Cancer Discov 2021;11(6):1353–67 doi 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van Meir H, Nout RA, Welters MJ, Loof NM, de Kam ML, van Ham JJ, et al. Impact of (chemo)radiotherapy on immune cell composition and function in cervical cancer patients. Oncoimmunology 2017;6(2):e1267095 doi 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1267095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hanoteau A, Newton JM, Krupar R, Huang C, Liu HC, Gaspero A, et al. Tumor microenvironment modulation enhances immunologic benefit of chemoradiotherapy. J Immunother Cancer 2019;7(1):10 doi 10.1186/s40425-018-0485-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang H, Zhou W, Chen R, Xiang B, Zhou S, Lan L. CXCL10 is a Tumor Microenvironment and Immune Infiltration Related Prognostic Biomarker in Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Front Mol Biosci 2021;8:611508 doi 10.3389/fmolb.2021.611508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee KS, Chung WY, Park JE, Jung YJ, Park JH, Sheen SS, et al. Interferon-gamma-Inducible Chemokines as Prognostic Markers for Lung Cancer. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18(17) doi 10.3390/ijerph18179345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.