Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to compare microvascular Doppler sonography (MDS) and laser speckle contrast imaging (LSCI) for assessing vessel patency and aneurysm occlusion during microsurgical clipping of intracranial aneurysms.

Methods

MDS and LSCI were used after clip placement during six neurovascular procedures including six patients, and agreement between the two techniques was assessed. LSCI was performed in parallel or right after MDS evaluation. The Doppler response was assessed through listening while flow in the LSCI videos was evaluated by three blinded neurovascular surgeons after the surgery. Statistical analysis determined the agreement between the techniques in assessing flow in 18 regions of interest (ROIs).

Results

Agreement between MDS and LSCI in assessing vessel patency was observed in 87 % of the ROIs. LSCI accurately identified flow in 93.3 % of assessable ROIs, with no false positive or negative measurements. Three ROIs were not assessable with LSCI due to motion artifacts or poor image quality. No complications were observed.

Conclusions

LSCI demonstrated high agreement with MDS in assessing vessel patency during microsurgical clipping of intracranial aneurysms. It provided continuous, real-time, full-field imaging with high spatial resolution and temporal resolution. While MDS allowed evaluation of deep vascular regions, LSCI complemented it by offering unlimited assessment of surrounding vessels.

Keywords: Aneurysm clipping, Intraoperative blood flow visualization, Laser speckle contrast imaging (LSCI), Microvascular Doppler sonography, Vessel patency

1. Introduction

Intraoperative assessment of blood flow during surgical clipping of aneurysms can be challenging, necessitating the use of adjunctive techniques. Incomplete occlusion or residual neck remnants following clipping may contribute to aneurysm re-growth and rupture.1, 2, 3 The reported incidence of postoperative aneurysm remnants ranges from 3% to 21 %,4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 whereas unexpected vessel occlusion ranges from 2% to 11 %.4, 5, 6, 7,9,10

While digital subtraction angiography (DSA) is still considered the gold standard by many due to its superior resolution and diverse viewing angles, its adoption is limited in some centers due to its cost, invasiveness, and the need for additional trained personnel.11, 12, 13

Fluorescence angiography (FA) allows for robust real-time intraoperative assessment of vessel patency and aneurysm neck remnants after microsurgical clipping intraoperatively.14, 15, 16 The dye's fluorescence allows neurosurgeons to track blood flow within the cerebral vasculature, aiding in the identification of flow direction, patency, and potential complications arising in the surgical field of view. Additionally, microvascular Doppler sonography (MDS) provides a valuable intraoperative adjunct. The technique enables swift and reliable initial assessment of vessel patency immediately after clip placement.17,18 By providing single point measurements of blood flow in the vessels surrounding the aneurysm, MDS can help identify potential complications and improve the accuracy and safety of the clipping procedure.

In recent years, LSCI has emerged as a promising tool for non-invasive, full-field and continuous assessment of blood flow during neurosurgery.19, 20, 21, 22 LSCI offers instantaneous blood flow maps by capturing time-varying laser speckle patterns.23 Its blood flow visualization properties and adaptability to the surgical microscope make it a promising tool for surgical guidance in neurosurgery. The objective of this paper is the comparison of MDS and LSCI after aneurysm occlusion. The study evaluates the presence (flow) or absence (no flow) of blood flow in the vessels surrounding the aneurysms and within the aneurysm sac. The study aims to provide clinicians with a comparative analysis of these two techniques, highlighting their respective strengths and limitations in assessing blood flow during neurosurgery. By elucidating the potential advantages of LSCI over MDS, the study seeks to evaluate whether LSCI could improve surgical decision-making and patient outcomes in neurovascular procedures.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design

In accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines, we conducted a prospective observational cohort study at the Inselspital, University Hospital Bern, Bern, CH between February and March 2022 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT0502840). Local ethics committee in Bern, Switzerland approved the study under the Project-ID: 2021-D0043. Prior to the neurosurgery, we obtained informed consent from all eligible patients who were 18 years or older, non-pregnant, and able to provide informed consent.

All patients underwent standard craniotomy procedure under anesthesia. During the study period, 9 patients underwent surgical clipping procedures for unruptured intracranial aneurysms. During six aneurysm clipping procedures (78 %) involving 5 female and 1 male subjects with an average age of 51.7 years at the time of surgery (Table 1), LSCI videos were recorded while MDS was used to assess flow on surgically visible regions. Due to the optical nature of LSCI, only surgically visible regions of interest (ROIs) were included in the LSCI vs MDS comparative rating. For all six cases, we included a total of 18 ROIs in the rating process, which were defined based on the placement of the doppler probe on the structure of interest (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics included in the study.

| No. of patients | 6 (100 %) |

|---|---|

| Female | 5 (83 %) |

| Mean age (years, SD) | 51.7, 7 |

| Range (years) | 41–62 |

| Indication for surgery | 6 (100 %) |

| Unruptured intracranial aneurysm | 6 (100 %) |

| ⁃ MCA | 4 (66 %) |

| ⁃ ACOM | 1 (17 %) |

| ⁃ AChoA | 1 (17 %) |

| Simultaneous MDS and LSCI flow assessment | 18 (100 %) |

*Age in years on day of surgery. SD= Standard deviation, MCA = Middle cerebral artery, ACOM = Anterior communicating artery, AChoA = Anterior choroidal artery.

2.2. Microvascular Doppler sonography

MDS is a valuable tool for rapidly assessing blood flow patterns and ensuring that the surgical clip does not obstruct major structures. Hence, MDS was employed following clip ligation to quickly assess vessel patency and confirm successful aneurysm occlusion before performing a more detailed assessment with FA. To conduct MDS, the study utilized a microprobe (VTI 20 MHz Disposable Doppler Probe, Vascular Technology Incorporated, Noshua, NH) which was delicately placed in contact with the ROI. The amplitude response was assessed through listening, rather than visual observation, to determine blood flow in both the affected vessels and the aneurysm sac. All 18 (100 %) Doppler evaluations were conducted right before FA and all MDS findings agreed with FA findings. No surgical changes were made in between the MDS evaluation and FA. The ROIs defined in the rating process were based on the location of the probe during MDS patency evaluation.

2.3. Laser speckle contrast imaging

The image acquisition device used for LSCI was described previously.19,20 In brief, the surgical field of view was illuminated with a non-visible, low-power continuous laser diode (λ = 785 nm). The technique requires the surgical field of interest to be visibly exposed, aligning with the inherently limited penetration depth (<1 mm) of optical modalities such as LSCI.24 The reflected light was collected by the surgical microscope (OPMI Pentero 900, Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) and imaged onto a camera attached to the side observer port. The LSCI instrumentation was integrated onto the operating microscope, allowing the use of both techniques during critical moments of the surgery. Speckle contrast images were displayed in real-time on operating room monitors.25 We used different pseudo colors to display the speckle contrast values, depending on the case and time point of the surgery. These values were either shown next to the white light image or overlaid onto the surgical microscope white light images using a median filter and pseudo color, as explained in a previous study.20 During the surgery, LSCI was performed in parallel or right after MDS evaluation. We made sure that there were no surgical changes in clip placement or physiological changes between MDS and LSCI recordings used in the rating. LSCI was employed in this study solely to assess its robustness; the surgeon did not utilize LSCI data to alter the surgical approach or clip placement.

2.4. Rating process and statistical analysis

The assessment of vessel flow in LSCI videos was conducted by three neurovascular surgeons affiliated with the Department of Neurosurgery, Inselspital, University Hospital in Bern. To carry out the rating process, the raters were provided with both white light and LSCI videos without knowing the true flow status in the ROIs prior to rating the LSCI images. The raters categorized the vessel flow as flow, no flow, not assessable due to poor image quality, or not assessable due to pulsatile motion artifact. LSCI is sensitive to various types of motion, including the pulsatile motion of blood and the mechanical pulsation of the brain at each heartbeat. This sensitivity means that even in regions where there is no actual blood flow, the movement of the ROI due to brain motion can lead to false positives, challenging the accuracy of blood flow assessment.19 The white light and LSCI video recordings were stored and rated after the surgery. To establish the combined rating, the most frequently selected rating for each region of interest (at least two identical answers with three reviewers) was chosen, with no instances of three different ratings. The results of the combined rating can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Regions of interest (ROI) type and laser speckle contrast imaging agreement with microvascular Doppler sonography (MDS).

| ROI type n (%) | Agreement with MDS n (%) | Disagreement with MDS n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total n (%) | 18 (100 %) | 15 (83 %) | 3 (17 %) |

| Branching artery | 13 (72 %) | 11 (85 %) | 2 (15 %) |

| Harboring artery | 2 (11 %) | 2 (100 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| Aneurysm | 3 (17 %) | 2 (67 %) | 1 (33 %) |

3. Results

3.1. Accordance of LSCI findings: comparison to MDS

The flow at 18 different time points was assessed using MDS. MDS evaluated 15 ROIs (83 %) as open (flow) and 3 (17 %) ROIs as closed (no flow). LSCI allowed for the assessment of vessel flow in 15 (83 %) ROIs. Out of those, 14 (93.3 %) ROIs showed flow, while only 1 (7.7 %) ROI showed no flow. Vessel flow in 3 (17 %) ROIs was not assessable due to pulsatile motion artifact present in 2 (11.1 %) and poor image quality in 1 (5.5 %) ROIs. Table 2 shows the agreement and disagreement results based on the ROI type, which include 13 branching arteries (72 %), 2 harboring arteries (11 %), and 3 aneurysm sacs (17 %). The branching artery category refers to arteries that branch off from a main artery while the harboring artery category indicates the main artery that directly supplies blood to the aneurysm. Finally, the aneurysm category represents the location of the aneurysm itself.

The disagreement between LSCI and MDS was observed in 3 ROIs that were not assessable with LSCI due to pulsatile motion artifact or poor image quality (n = 3, 17 %). The agreement between the ROIs that were assessable with LSCI was 100 % (Fig. 1). The average agreement between the LSCI ratings and MDS assessments for all three raters was 87 % (Rater 1: 78 % agreement, Rater 2: 94 % agreement, Rater 3: 89 % agreement) (Fig. 1). No complications related to the techniques were observed for MDS or LSCI. Our results indicate that LSCI is a reliable tool for assessing patency after clip placement. However, MDS should remain the preferred modality for assessing deep and covered structures, especially when quantitative flow information is required. Therefore, both techniques should be considered as complementary.

Fig. 1.

Surgeon rating results of the laser speckle contrast imaging (LSCI) vs microvascular doppler sonography comparison based on region of interest (ROI) type. A total of 18 ROIs were rated by each surgeon. The 7 ratings with disagreements were due to poor LSCI image quality: the ROI was judged as not assessable with LSCI.

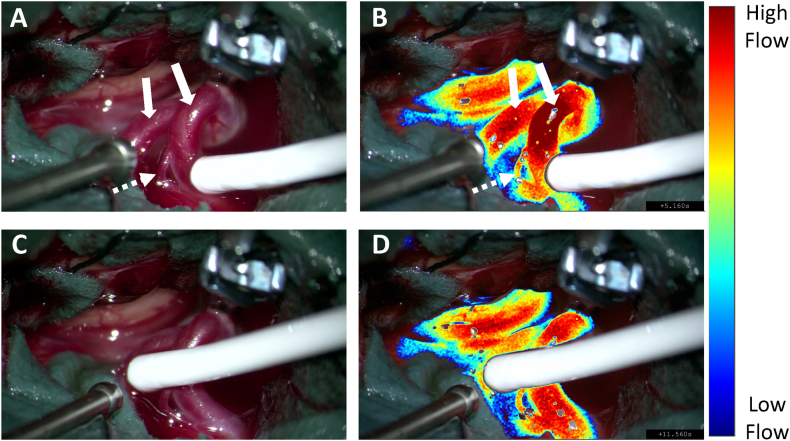

Fig. 2 illustrates LSCI visualization during vessel patency evaluation with MDS following MCA aneurysm clipping, where both M2 branching arteries (arrows) were evaluated as open by MDS. The surgical field of view (Fig. 1 A & C) and corresponding LSCI overlay images (Fig. 1 B & D) demonstrate the agreement between MDS and LSCI in assessing the patency in the M2 branching vessels post aneurysm clipping (Video).

Fig. 2.

LSCI flow assessment of the vessels (solid white arrows) adjacent to the clipped middle cerebral artery aneurysm during microvascular doppler sonography. (A & C) White light image of the surgical field of view during M2 patency assessment. (B & D) Respective LSCI images overlayed onto the white light images with a threshold applied to visualize high flow vessels. High speckle contrast values in blue represent “low flow” and low speckle contrast values in white represent “high flow.” The dotted white arrow shows a small perforator stemming from the M2 artery. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Supplementary video related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wnsx.2024.100377

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

1

4. Discussion

The success of microsurgical clipping in treating intracranial aneurysms heavily relies on preserving blood flow in the vessels surrounding the aneurysm. However, these vessels are fragile, and the complex surgical procedures needed to perform the clipping put them at high risk of occlusion or injury. This may cause ischemic or hemorrhagic complications, highlighting the critical importance of monitoring blood flow during and after the clipping procedure. Intraoperative vascular imaging and monitoring have been shown to improve the quality and ease the of surgical treatment.16, 17, 18,26,27 This study compared the effectiveness of LSCI to MDS.

MDS is a real-time, non-invasive technique that has been shown to be highly effective in evaluating blood flow during microsurgical clipping in neurosurgery. This technique requires the introduction of a probe in the surgical field of view to contact the structure of interest, such as a vessel or an aneurysm, allowing for a point measurement of the blood flow. Unlike intraoperative DSA, MDS is a low-cost technique that can be used repeatedly during the surgical procedure to assess the success of the clipping and ensure the preservation of blood flow in surrounding vessels.

LSCI is an emerging blood flow imaging modality, which provides full-field, real-time and continuous blood flow imaging. The technique does not require the injection of a dye or the introduction of an additional instrument in the surgical field of view. Hence, it can provide continuous blood flow monitoring throughout microsurgical clip placement of aneurysms.

The goal of the present study was to evaluate LSCI to the gold standard MDS as a tool for patency assessment of microsurgical clipping in intracranial aneurysm surgeries. The comparative study also aims to compare the potential advantages and pitfalls of these two intraoperative evaluation techniques in comparison with each other. The study demonstrated that, on average, LSCI provided accurate patency evaluation in 87 % of the vessels surrounding the aneurysm and the aneurysm sac which were evaluated with MDS after microsurgical clip placement. The 3 ROIs where the LSCI flow rating disagreed with MDS had low image quality and were rated as not assessable. The absence of false positive or false negative measurements demonstrates that LSCI did not erroneously evaluate any ROIs.

LSCI has proved to be a reliable tool in monitoring blood flow and perfusion in neurosurgery.20,21,28, 29, 30 As opposed to MDS, LSCI offers unrestricted and continuous blood flow and patency evaluation over the entire surgical field of view (Video, Fig. 2). The high spatial resolution of LSCI supports the assessment of small perforators with submillimeter diameter as shown in Fig. 2.

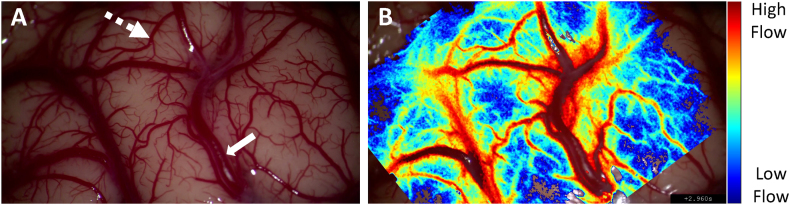

Fig. 3 further demonstrates LSCI's full-field imaging capabilities. The LSCI overlay image of the cortical surface (Fig. 3B) showcases its ability to assess flow in vessels of various sizes. Small pial arteries (dotted arrow, Fig. 3A) and larger surface arteries (solid arrow, Fig. 3A) are clearly characterized. LSCI is also sensitive to microcirculation in the cortex, offering real-time perfusion information in the spaces between defined vessels. The resolution of LSCI aligns with the surgical microscope magnification, as the integrated LSCI system utilizes the collection optics of the operating microscope. This allows for the evaluation of flow dynamics in very small vessels, provided they are resolved by the surgical microscope. In contrast, MDS only provides patency information for a single vessel at a time and lacks a “one probe fits all” characteristic, requiring careful selection of frequency and footprint of the probe to match the size of the structure of interest. Consequently, MDS has limitations in evaluating the patency of small vessels, such as perforators.18

Fig. 3.

Full-field flow assessment of the cortical surface with laser speckle contrast imaging (LSCI). A) Surgical microscope white light image of the surgical field of view. B) Corresponding LSCI overlay image showcasing the technique's ability to assess flow in vessels of various sizes including large arteries (solid arrow) and small pial arteries (dotted arrow).

However, MDS overcomes many of the inherent limitations of LSCI. One major technical constraint of the LSCI is that it can solely evaluate blood flow in superficial vascular regions that are surgically exposed. MDS enabled evaluation of vessels deep in the surgical field that were located below the aneurysm sac or not surgically visible. In such cases, LSCI faced difficulty due to the limited light throughput, which resulted in poor image quality and low contrast. In addition, one of the most significant benefits of MDS is its accessibility, as it does not necessitate the use of a surgical microscope or magnification. LSCI has additional limitations, including sensitivity to static scatters, which can lead to misinterpretation of flow in calcified aneurysms, and limited penetration depth, restricting robust flow measurements in thick arteries like the carotid artery.31 Goldberg et al30 highlighted a current challenge for LSCI in detecting aneurysm neck remnants. The slow filling of the aneurysm, combined with the pulsatile motion artifact in the LSCI signal, complicated the assessment of flow profiles in that region. While software and hardware improvements to reduce pulsatile motion artifacts may aid in identifying aneurysm neck remnants, both LSCI and MDS currently face this limitation.18

The purpose of this study was to evaluate and compare the strengths and weaknesses of both LSCI and MDS as intraoperative assessment techniques. While MDS offers advantages in terms of its ability to evaluate deep vascular regions, LSCI provides continuous and unrestricted assessment of the vessels surrounding the aneurysm, which can provide increased certainty during the surgical procedure. Although further research is needed to fully understand the potential of LSCI, the results of this study suggest that it may complement MDS in assessing patency during microsurgical clipping improving surgical decision-making and patient outcomes in neurosurgical procedures.

4.1. Limitations

One of the primary limitations of our study is the absence of quantitative MDS data providing additional information on blood flow dynamics. Including blood flow velocity, flow direction and the pulsatility index into our analysis would enhance the comparison of two techniques. Secondly, our study has a small sample size of only 16 comparisons. This may have limited the statistical power of our analysis and may have resulted in an increase in false negative values. We acknowledge that a larger sample size would have allowed for a more comprehensive analysis and potentially more definitive results. Furthermore, our study is limited to only comparing both techniques during intracranial aneurysm surgery. This may limit the generalizability of our results to other surgical procedures or types of vascular pathology. Other factors, such as variations in surgical technique, patient characteristics, and types of aneurysms, may also impact the results.

5. Conclusion

To conclude, our study highlights the agreement (87 %) between LSCI and MDS in evaluating vessel patency after microsurgical clipping of intracranial aneurysms. The valuable information provided by both techniques can assist surgeons in making more informed decisions, ultimately improving patient outcomes and reducing intraoperative complications. LSCI offers unlimited and continuous full-field imaging with high spatial resolution and should be regarded as a promising adjunctive tool to MDS in neurosurgical procedures.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Alexis Dimanche: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Johannes Goldberg: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Data curation, Conceptualization. David R. Miller: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Data curation. David Bervini: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Investigation. Andreas Raabe: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Andrew K. Dunn: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Andrew Dunn and David Miller report financial support was provided by Dynamic Light. Andrew Dunn and David Miller report a relationship with Dynamic Light that includes: board membership, consulting or advisory, and equity or stocks. Andrew Dunn has patent issued to University of Texas at Austin.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the entire neurosurgical team and staff at the Inselspital in Bern, CH for their help throughout the clinical study. Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [NS108484] and Carl Zeiss Meditec AG, Oberkochen.

Abbreviation List

- DSA

digital subtraction angiography

- ICGA

indocyanine green angiography

- FA

fluorescence angiography

- LSCI

laser speckle contrast imaging

- MDS

microvascular Doppler sonography

- ROI

region of interest

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wnsx.2024.100377.

Contributor Information

Alexis Dimanche, Email: alexis.dimanche@utexas.edu.

Johannes Goldberg, Email: johannes.goldberg@insel.ch.

David R. Miller, Email: david.r.miller8@gmail.com.

David Bervini, Email: david.bervini@insel.ch.

Andreas Raabe, Email: andreas.raabe@insel.ch.

Andrew K. Dunn, Email: adunn@utexas.edu.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

FigS1.

References

- 1.Hernesniemi J., Vapalahti M., Niskanen M., et al. One-year outcome in early aneurysm surgery: a 14 years experience. Acta Neurochir. 1993;122(1–2):1–10. doi: 10.1007/BF01446980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fogelholm R., Hernesniemi J., Vapalahti M. Impact of early surgery on outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. A population-based study. Stroke. 1993;24(11):1649–1654. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.24.11.1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.David C.A., Vishteh A.G., Spetzler R.F., Lemole M., Lawton M.T., Partovi S. Late angiographic follow-up review of surgically treated aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 1999;91(3):396–401. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.91.3.0396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Payner T.D., Horner T.G., Leipzig T.J., Scott J.A., Gilmor R.L., DeNardo A.J. Role of intraoperative angiography in the surgical treatment of cerebral aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 1998;88(3):441–447. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.88.3.0441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauer B.L. Intraoperative angiography in cerebral aneurysm and AV-malformation. Neurosurg Rev. 1984;7(2–3):209–217. doi: 10.1007/BF01780706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang G., Cawley C.M., Dion J.E., Barrow D.L. Intraoperative angiography during aneurysm surgery: a prospective evaluation of efficacy. J Neurosurg. 2002;96(6):993–999. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.96.6.0993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Origitano T.C., Schwartz K., Anderson D., Azar-Kia B., Reichman O.H. Optimal clip application and intraoperative angiography for intracranial aneurysms. Surg Neurol. 1999;51(2):117–128. doi: 10.1016/S0090-3019(97)00529-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thornton J., Bashir Q., Aletich V.A., Debrun G.M., Ausman J.I., Charbel F.T. What percentage of surgically clipped intracranial aneurysms have residual necks? Neurosurgery. 2000;46(6):1294–1300. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200006000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alexander T.D., Macdonald R.L., Weir B., Kowalczuk A. Intraoperative angiography in cerebral aneurysm surgery: a prospective study of 100 craniotomies. Neurosurgery. 1996;39(1):10–18. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199607000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klopfenstein J.D., Spetzler R.F., Kim L.J., et al. Comparison of routine and selective use of intraoperative angiography during aneurysm surgery: a prospective assessment. J Neurosurg. 2004;100(2):230–235. doi: 10.3171/jns.2004.100.2.0230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kallmes D.F., Kallmes M.H. Cost-effectiveness of angiography performed during surgery for ruptured intracranial aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18(8):1453–1462. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klopfenstein J.D., Spetzler R.F., Kim L.J., et al. Comparison of routine and selective use of intraoperative angiography during aneurysm surgery: a prospective assessment. J Neurosurg. 2004;100(2):230–235. doi: 10.3171/jns.2004.100.2.0230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katz J.M., Gologorsky Y., Tsiouris A.J., et al. Is routine intraoperative angiography in the surgical treatment of cerebral aneurysms justified? A consecutive series of 147 aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 2006;58(4):719–727. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000204316.49796.A3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raabe A., Nakaji P., Beck J., et al. Prospective evaluation of surgical microscope-integrated intraoperative near-infrared indocyanine green videoangiography during aneurysm surgery. J Neurosurg. 2005;103:982–989. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.103.6.0982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao X., Belykh E., Cavallo C., et al. Application of fluorescein fluorescence in vascular neurosurgery. Front Surg. 2019;6 doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2019.00052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raabe A., Beck J., Gerlach R., Zimmermann M., Seifert V. Near-infrared indocyanine green video angiography: a new method for intraoperative assessment of vascular flow. Neurosurgery. 2003;52(1):132–139. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200301000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kapsalaki E.Z., Lee G.P., Robinson J.S., Grigorian A.A., Fountas K.N. The role of intraoperative micro-Doppler ultrasound in verifying proper clip placement in intracranial aneurysm surgery. J Clin Neurosci. 2008;15(2):153–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fischer G., Stadie A., Oertel J.M.K. Near-infrared indocyanine green videoangiography versus microvascular Doppler sonography in aneurysm surgery. Acta Neurochir. 2010;152(9):1519–1525. doi: 10.1007/s00701-010-0723-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richards L.M., Towle E.L., Fox D.J., Dunn A.K. Intraoperative laser speckle contrast imaging with retrospective motion correction for quantitative assessment of cerebral blood flow. Neurophotonics. 2014;1(1) doi: 10.1117/1.nph.1.1.015006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller D.R., Ashour R., Sullender C.T., Dunn A.K. Continuous blood flow visualization with laser speckle contrast imaging during neurovascular surgery. Neurophotonics. 2022;9(2) doi: 10.1117/1.nph.9.2.021908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hecht N., Woitzik J., König S., Horn P., Vajkoczy P. Laser speckle imaging allows real-time intraoperative blood flow assessment during neurosurgical procedures. J Cerebr Blood Flow Metabol. 2013;33(7):1000–1007. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Konovalov A., Gadzhiagaev V., Grebenev F., et al. Laser speckle contrast imaging in neurosurgery: a systematic review. World Neurosurg. 2023;171:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2022.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boas D.A., Dunn A.K. Laser speckle contrast imaging in biomedical optics. J Biomed Opt. 2010;15(1) doi: 10.1117/1.3285504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ayata C., Dunn A.K., Gursoy-Özdemir Y., Huang Z., Boas D.A., Moskowitz M.A. Laser speckle flowmetry for the study of cerebrovascular physiology in normal and ischemic mouse cortex. J Cerebr Blood Flow Metabol. 2004;24(7):744–755. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000122745.72175.D5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tom W.J., Ponticorvo A., Dunn A.K. Efficient processing of laser speckle contrast images. IEEE Trans Med Imag. 2008;27(12):1728–1738. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2008.925081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Oliveira J.G., Beck J., Seifert V., Teixeira M.J., Raabe A. Assessment of flow in perforating arteries during intracranial aneurysm surgery using intraoperative near-infrared indocyanine green videoangiography. Operative Neurosurgery. 2007;61(3):63–73. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000289715.18297.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharma M., Ambekar S., Ahmed O., et al. The utility and limitations of intraoperative near-infrared indocyanine green videoangiography in aneurysm surgery. World Neurosurg. 2014;82(5):e607–e613. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2014.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dimanche A., Miller D.R., Goldberg J., Raabe A., Dunn A.K., Bervini D. Continuous hemodynamics monitoring during arteriovenous malformation microsurgical resection with laser speckle contrast imaging: case report. Front Surg. 2023;10 doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2023.1285758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dimanche A., Bervini D., Miller D.R., et al. Cortical perfusion measurements with laser speckle contrast imaging during adenosine induced cardiac arrest for aneurysm clipping: a case report. Acta Neurochir. 2024;166(1):27. doi: 10.1007/s00701-024-05925-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldberg J., Miller D.R., Dimanche A., et al. Intraoperative laser speckle contrast imaging to assess vessel flow in neurosurgery: a pilot study. Neurosurgery. 2023 doi: 10.1227/neu.0000000000002776. Published online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dimanche A., Miller D.R., Dunn A.K. 2023 IEEE Biomedical Circuits and Systems Conference (BioCAS). IEEE. 2023. Considerations for intraoperative laser speckle contrast imaging for vessel flow visualization; pp. 1–4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

1