Abstract

Small molecule drugs can be used to target nucleic acids (NA) to regulate biological processes. Computational modeling methods, such as molecular docking or scoring functions, are commonly employed to facilitate drug design. However, the accuracy of the scoring function in predicting the closest-to-native docking pose is often suboptimal. To overcome this problem, a machine learning model, RmsdXNA, was developed to predict the root-mean-square-deviation (RMSD) of ligand docking poses in NA complexes. The versatility of RmsdXNA has been demonstrated by its successful application to various complexes involving different types of NA receptors and ligands, including metal complexes and short peptides. The predicted RMSD by RmsdXNA was strongly correlated with the actual RMSD of the docked poses. RmsdXNA also outperformed the rDock scoring function in ranking and identifying closest-to-native docking poses across different structural groups and on the testing dataset. Using experimental validated results conducted on polyadenylated nuclear element for nuclear expression triplex, RmsdXNA demonstrated better screening power for the RNA-small molecule complex compared to rDock. Molecular dynamics simulations were subsequently employed to validate the binding of top-scoring ligand candidates selected by RmsdXNA and rDock on MALAT1. The results showed that RmsdXNA has a higher success rate in identifying promising ligands that can bind well to the receptor. The development of an accurate docking score for a NA–ligand complex can aid in drug discovery and development advancements. The code to use RmsdXNA is available at the GitHub repository https://github.com/laiheng001/RmsdXNA.

Keywords: nucleic acid, machine learning, RMSD prediction, molecular docking

INTRODUCTION

Therapeutic treatments have typically focused on modifying protein targets [1, 2], but there is a growing acknowledgment of the critical role of ribonucleic acid (RNA) and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) molecules in numerous biological processes and disease pathways [3–6]. Dysfunctions in RNA and DNA that can cause diseases [7–9], such as cancer, neurological problems and viral infections [10, 11], can be treated using small chemicals. As our understanding of NA increases, especially with developments in computational methodologies [12, 13] and structure-solving technologies [14], targeting NA for drug development shows promise in the field of molecular medicine.

Currently, however, solving the structure of NA complexes using experimental methods remains a challenge. As an alternative, computational methods, including molecular docking, can enhance the understanding of NA complexes and expedite the development of robust drug discovery models [15–17]. Recent development of such docking tools for NA–ligand complexes includes rDock [18], NLDock [19] and RLDOCK [20]. Molecular docking involves predicting the binding orientation and affinity between a small molecule (ligand) and a target protein or NA (receptor). Its precision depends on the reliability of the scoring functions [21, 22], which is crucial for saving time and cost for drug discovery [23, 24]. However, accurate modelling of NA structures remains challenging because of its complexity and flexibility [25]. While the MM-PBSA [26] and free-energy perturbation methods [27] can accurately select stronger ligand binders compared to docking scoring functions, they are time-consuming and not suitable for high-throughput docking or virtual screening (VS) applications.

Integrating machine learning (ML) into docking algorithms can improve the accuracy and efficiency of computational tools [28–30]. Numerous ML algorithms that outperform a broad range of classical scoring functions have been successfully utilized in protein systems [31]. However, these scoring functions often cannot be applied directly to NA complexes [32, 33]. The limited availability of high-quality training datasets for NA complex structures poses a significant obstacle to the generation of accurate and robust models [34]. Hence, the exploration of alternative feature extraction and ML algorithms methods is essential for addressing these challenges.

Although not as common as protein–ligand systems, two recent ML-based scoring functions have been developed to improve scoring functions for RNA–ligand interactions. RNAPosers [35] is trained on 80 RNA–ligand complexes to classify if the ligand pose is native-like. On the other hand, AnnapuRNA [36] is trained on 131 RNA–ligand complexes to develop a scoring function for predicting binding poses. Both methods demonstrated improved performance compared to existing tools for pose identification. However, the small dataset used for training the models can lead to overfitting and hinder the model’s performance for unseen docking scenarios. In addition, both methods use interaction features involving unmodified RNA residues only, neglecting crucial interactions involving modified atoms, which can alter the chemical properties of NA [37]. A diversified model should also be applicable to some important NA–ligand complexes, such as metal complex [38] or short peptide ligands [39], and RNA–DNA hybrid receptors [40]. Developing a ML-based scoring function suitable for NAs (both DNA and RNA) and structures with modified residues seems feasible due to their structural similarity.

In this work, a new ML-based regression model, RmsdXNA, was developed for accurately predicting the RMSD of the ligand poses for NA–ligand complex, which can also serve as the docking score. Using a larger dataset of 980 PDB structures than previous studies aims to improve generalizability. As the number of NA structures is still relatively small compared to proteins, using similar distance-based fingerprints from Wang et al. [41] with small feature dimension is feasible for RmsdXNA. Further modifications to the atom representation and the machine learning algorithm were performed to better suit NA–ligand datasets. RmsdXNA is applicable to diverse complexes involving different types of NA receptors (RNA, DNA, RNA–DNA hybrid, and NA with modified residues) and ligands, including metal complexes and short peptides. The best performing RmsdXNA model achieved an average Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC) of 0.64531  0.36262 and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (SRCC) of 0.58465

0.36262 and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (SRCC) of 0.58465  0.35195 for each ligand. RmsdXNA outperforms the rDock [18] scoring function in its ability to rank and identify closest-to-native poses across different structural groups and on the testing dataset. This was also validated using the in-vitro experimental results by Swain et al. [42] on PAN ENE triple helix RNA. For MALAT1 virtual screening, MD simulations revealed a higher success rate for RmsdXNA in identifying the most promising ligands. These findings solidify RmsdXNA as a robust and effective scoring tool for pose identification and ligand screening in drug discovery applications.

0.35195 for each ligand. RmsdXNA outperforms the rDock [18] scoring function in its ability to rank and identify closest-to-native poses across different structural groups and on the testing dataset. This was also validated using the in-vitro experimental results by Swain et al. [42] on PAN ENE triple helix RNA. For MALAT1 virtual screening, MD simulations revealed a higher success rate for RmsdXNA in identifying the most promising ligands. These findings solidify RmsdXNA as a robust and effective scoring tool for pose identification and ligand screening in drug discovery applications.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Dataset preparation

The dataset used in the experiments consists of experimentally solved NA structures obtained from the Nucleic Acid Database (NDB) [43, 44], which contains 11 821 NA structures including both DNA and RNA. PyMol [45] was used to process the structural information. Additional data cleaning and refinement procedures are described in Appendix B. In total, 1434 ligands from 980 NA complexes, with some structures having multiple ligands, were used in the experiment. The use of a large and diverse database allows the model to learn a comprehensive representation of the underlying patterns and relationships in the data, leading to better generalization to unseen examples. The list of PDB structures used is found in Appendix A.

Docking tools

Each ligand forms a receptor–ligand pair in each complex. Rigid NA-flexible ligand docking was performed using rDocK [18] at the target search box, with the native ligand as the reference ligand. rDock was chosen because it outperforms other docking tools in pose identification for NA complexes [19, 46]. The docking pose search algorithm of rDock is similar to that of AutoDock [47], which uses the Monte Carlo simulated annealing method to generate random poses with unique configurations in each dock attempt. This data augmentation method can mitigate the limitation of the small NA–ligand dataset by increasing the number of datapoints with generated poses. Using rDock, the rbcavity command was used to generate the docking volume, with the docking radius set to 10 Å. For each redocking run, 100 runs-per-ligand rDock jobs were performed using the rbdock command. Only the docking poses with symmetry-corrected RMSD values  10 Å, measured using sPyRMSD [48], were considered as a successful dock and were included in the training dataset. 100 poses were selected from each ligand that had at least 25% successful docking rate (able to generate at least 100 successful dock poses out of 400 dock attempts) to be included into the dataset.

10 Å, measured using sPyRMSD [48], were considered as a successful dock and were included in the training dataset. 100 poses were selected from each ligand that had at least 25% successful docking rate (able to generate at least 100 successful dock poses out of 400 dock attempts) to be included into the dataset.

Feature generation

The workflow of dataset generation and model training for RmsdXNA to predict the RMSD of the docked poses is shown in Figure 1. For each distinctive interaction between the receptor and docked ligand atoms, the interatomic distance and atom types are used as features. In the context of ML scoring functions for NAs, the quantity of structures within the dataset is notably lower than that of the proteins. Reducing the number of employed features is crucial to prevent overfitting, the curse of dimensionality and data sparsity. Previous studies such as OnionNet [49] and OnionNet2 [50] adopted the count of contact points at each shell as their feature metric, whereas RNAposers [35] employed the receptor’s atom name to generate distance-based features. However, these methodologies create an abundance of features, resulting in an unfavorable high feature-to-instance ratio dataset. On the other hand, the coarse-grain representation of the RNA and ligand structures [51, 52] in AnnapuRNA [36] might sacrifice atomic-level details, especially for non-canonical residues, potentially compromising the model’s ability to capture specific interactions.

Figure 1.

Overall architecture of the RmsdXNA framework. (A) Inter-molecular distance between a NA receptor atom and the ligand atom within a cutoff distance,  is extracted for each generated pose. (B) The distance is used to form the

is extracted for each generated pose. (B) The distance is used to form the  and

and  terms, which will be concatenate with the rDock scoring components to form the features, X. The label, y is the actual RMSD of the docked poses. (C) XGBoostRegressor is used to train on the dataset predict the RMSD of the docked poses.

terms, which will be concatenate with the rDock scoring components to form the features, X. The label, y is the actual RMSD of the docked poses. (C) XGBoostRegressor is used to train on the dataset predict the RMSD of the docked poses.

In RmsdXNA, the receptor and ligand SYBYL atom type representation is used as the interaction label. This generates fewer features in the dataset and allows the retention of important atomic-level interaction information such as pi-stacking and hydrogen bonding interactions. The remaining challenge involves combining each pairwise distance into a structured dataset suitable for training the ML model, while simultaneously retaining interaction proximity and frequency information. The distance is used to model the intermolecular potential energy between the receptor and the ligand molecule, which is represented by the sum of the coulomb and Lennard-Jones interaction terms, as shown in Equation 1. Such physics-inspired distance features were explored by Wang et al. [41] in protein–ligand interactions.

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

The values of the interaction constants are unknown and are factorized to form constants a, b and c. Equation 1 can be simplified to form Equation 2 by factorizing the constants. For a given receptor–ligand structure, the intermolecular distance between 2 atoms,  , can be easily obtained from the structural coordinates. ML is then used to determine the arbitrary constants. Assuming that there is a correlation between the RMSD and intermolecular forces, the RMSD can be predicted using the above equations. The intuition behind this assumption is that the closer-to-native ligand pose (smaller RMSD) should have stronger intermolecular interaction with NA than other poses. For each docked ligand pose, the interaction feature values between receptor atom

, can be easily obtained from the structural coordinates. ML is then used to determine the arbitrary constants. Assuming that there is a correlation between the RMSD and intermolecular forces, the RMSD can be predicted using the above equations. The intuition behind this assumption is that the closer-to-native ligand pose (smaller RMSD) should have stronger intermolecular interaction with NA than other poses. For each docked ligand pose, the interaction feature values between receptor atom  and ligand atom

and ligand atom  similar to Equation 2 are represented by

similar to Equation 2 are represented by  , such that:

, such that:

|

where:

= fingerprint function, for

= fingerprint function, for  {

{ ,

,  ,

,

}

} = distance between the receptor atom

= distance between the receptor atom  and ligand atom

and ligand atom

= receptor residue-atom type, represented by

= receptor residue-atom type, represented by

= receptor residue type, for

= receptor residue type, for  {A, C, G, U/T, N, OTH, Metal}

{A, C, G, U/T, N, OTH, Metal}

= receptor SYBYL atom type

= receptor SYBYL atom type

= ligand SYBYL atom type

= ligand SYBYL atom type

=cutoff distance (Å), for

=cutoff distance (Å), for  {7, 8, 9, 10}

{7, 8, 9, 10}

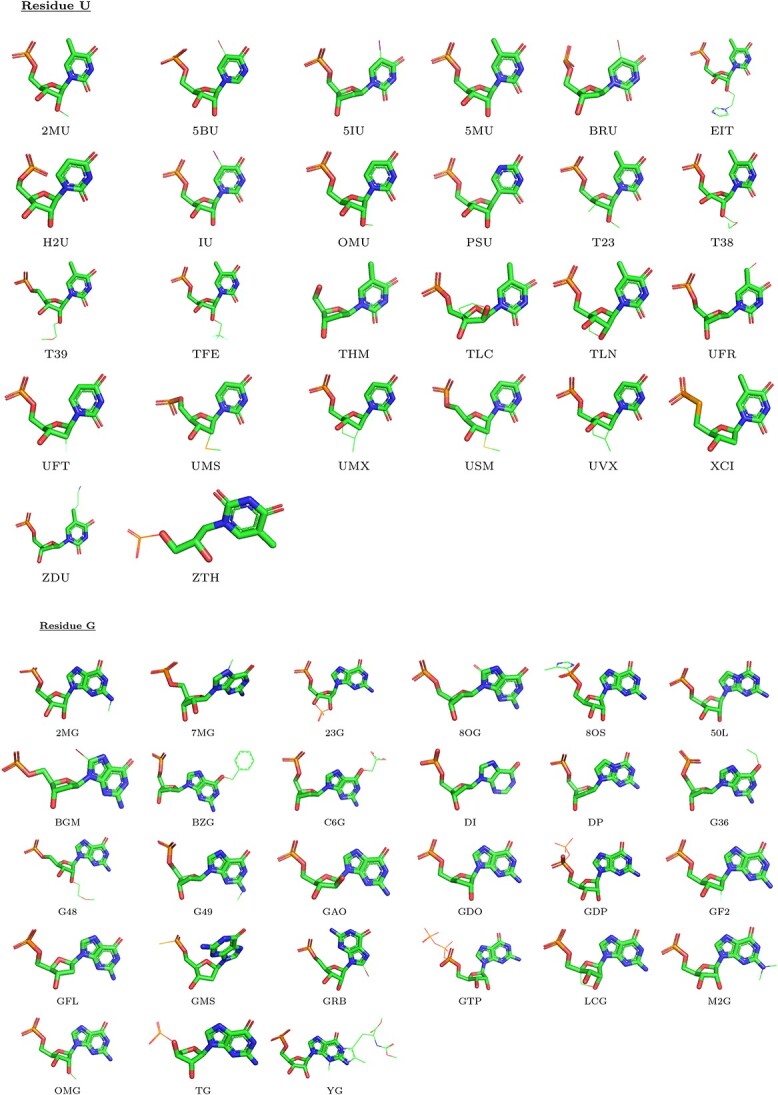

The NA residues can be classified into five generalized types, namely adenine (A), uracil (U) or thymine (T), cytosine (C), guanine (G), and ribose and phosphate backbone (N). The nucleobases of DNA and modified residue nucleobases are grouped into 4 main RNA nucleobases (A, U, G, C), depending on which nucleobases the residues are mutated from or have the closest structural similarity with (Appendix D), with thymine being in the same group as uracil. The NA SYBYL atom types are determined based on their position on these residues, and atoms in the backbone have residue type ’N’ (Appendix E). The atoms in the modified region of the residues have residue type ’OTH’. These NA atoms and some ligand atoms with low occurrence are grouped by their chemical similarity, as described in Appendix C. The grouping of the residues and atom types reduces the sparsity of the dataset and the number of features in the dataset by binning the columns with a high number of 0-values, hence improving the generalizability of the model and making it applicable to datasets with modified residues. In total, 24 ligand atom types and 26 NA atom types (unique combinations of the residues and its corresponding atom types) were used, resulting in 624 pairs of interactions. Subsequently, columns with all 0 values were removed from the dataset, thus a final 529 pairs of interactions were included.

In the ablation studies performed in Section 3.2, the dataset that yielded the best result used a cutoff distance,  , of 8 Å, along with the combination of the 1088

, of 8 Å, along with the combination of the 1088  and

and  terms with the 30 rDock scoring function component terms for the features. It is noted that the model can be used to predict the RMSD of poses generated by other docking tools as the rDock scoring function components can also be obtained from the initial poses.

terms with the 30 rDock scoring function component terms for the features. It is noted that the model can be used to predict the RMSD of poses generated by other docking tools as the rDock scoring function components can also be obtained from the initial poses.

Machine learning models

A supervised learning algorithm is used to train the ML model to predict the RMSD of docked poses, which can also be utilized as the docking score. For this regression prediction task, the XGBoost algorithm was chosen because of its fast training speed and strong predictive capabilities in comparison with other ML models such as Support Vector Regression, Multi-layer Perceptron, and Random Forest algorithms as shown in Table A4. The superior performance of XGBoost over other algorithms may be due to the sparsity of the dataset. To ensure that datasets with the same PDB ID are not present in both the training and validation datasets simultaneously, systematic sampling is employed on the sorted PDB IDs to select the validating PDB ID at regular intervals. The data points are then split into training and validation datasets by their PDB ID. For each dataset, 100 models with randomized hyperparameter values are trained using five-fold cross-validation to assess the models’ performance across different data subsets, which provides a reliable assessment of the model’s generalization capabilities.  values (Equation 3) are calculated for each fold. The model with the highest average validating

values (Equation 3) are calculated for each fold. The model with the highest average validating  across all folds,

across all folds,  , which indicates a strong correlation between predicted and actual RMSD, was selected as the best model. The model is trained with the learning objective of minimizing the regression squared loss and the hyperparameters of the best model are shown in Appendix F.

, which indicates a strong correlation between predicted and actual RMSD, was selected as the best model. The model is trained with the learning objective of minimizing the regression squared loss and the hyperparameters of the best model are shown in Appendix F.

|

(3) |

where:  = Actual RMSD of pose

= Actual RMSD of pose

= Predicted RMSD of pose

= Predicted RMSD of pose

= Average actual RMSD of all poses

= Average actual RMSD of all poses

Validation using experimental result and MD simulations

Unlike protein–ligand complexes, there is no CASF-2016 [53] equivalent dataset for evaluating NA complex docking tools. Instead, the comparison of the scoring power of RmsdXNA and rDock is validated on experimental results and using MD simulation.

In the microscale thermophoresis (MST) experiment by Swain et al. [42] on  PAN triplex, Compound 15 exhibited the strongest interaction among seven hit compounds (Compounds 8, 13, 15, 18, 19, 20 and 25) identified by small-molecule microarray (SMM) screening. Weak interactions were observed for the 3 Compound 15 modifications (Compounds 15-A1, 15-A2, 15-A3) compared to Compound 15, with Compounds 15-A2 and 15-A3 failing to bind to the RNA. The structures of the compounds are shown in Figure A2. Using the MST results, an ideal docking score that can distinguish strong and weak binders should be able to accurately rank the compounds by their binding affinity and give the best ranking to Compound 15. Rigid receptor-flexible ligand docking of the compounds was performed using rDock on the dinucleotide bulge position of

PAN triplex, Compound 15 exhibited the strongest interaction among seven hit compounds (Compounds 8, 13, 15, 18, 19, 20 and 25) identified by small-molecule microarray (SMM) screening. Weak interactions were observed for the 3 Compound 15 modifications (Compounds 15-A1, 15-A2, 15-A3) compared to Compound 15, with Compounds 15-A2 and 15-A3 failing to bind to the RNA. The structures of the compounds are shown in Figure A2. Using the MST results, an ideal docking score that can distinguish strong and weak binders should be able to accurately rank the compounds by their binding affinity and give the best ranking to Compound 15. Rigid receptor-flexible ligand docking of the compounds was performed using rDock on the dinucleotide bulge position of  PAN triplex (PDB ID: 6X5N), generating 100 poses for each compound. Then, RmsdXNA and rDock scores were used to rank the compounds.

PAN triplex (PDB ID: 6X5N), generating 100 poses for each compound. Then, RmsdXNA and rDock scores were used to rank the compounds.

MD simulations can offer insights into the dynamic behavior of receptor–ligand complexes, thus providing a more accurate assessment of ligand trajectories stability compared to docking alone [54, 55]. In this VS example, rDock is utilized to generate 20 poses within a 20 Å target search box on the 3’ end of MALAT1 [56, 57] (PDB ID: 4PLX) against two screening compound libraries, Hit2Lead (provided by Chembridge Corp. in San Diego, CA, USA, http://www.hit2lead.com) and Life Chemicals RNA screening library (https://www.lifechemicals.com). From each library, the top 20 ligands with the best rDock and RmsdXNA scores were chosen as the top-scored ligands for each method. Then, MD simulation (described in Appendix H) was conducted on the MALAT1-top ligand complexes to assess the reliability of the docking scoring methods through visual inspection the ligands’ stability in the receptor during the 100 ns trajectory [58].

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Model performance

The best model obtained from the hyperparameter tuning procedure had a  of 0.68301

of 0.68301  0.02330. The predicted RMSD values of each docked ligand pose in the validation dataset were combined across all folds to obtain the overall predicted RMSD for the entire dataset. Since the validation data remain unseen by the model in each fold, the obtained predictions accurately represent the model’s generalizability. Figure 2(a) shows the comparison of the predicted RMSD with the actual RMSD of the docked poses, which has a strong correlation coefficient (R) of 0.83051

0.02330. The predicted RMSD values of each docked ligand pose in the validation dataset were combined across all folds to obtain the overall predicted RMSD for the entire dataset. Since the validation data remain unseen by the model in each fold, the obtained predictions accurately represent the model’s generalizability. Figure 2(a) shows the comparison of the predicted RMSD with the actual RMSD of the docked poses, which has a strong correlation coefficient (R) of 0.83051  0.00115. This finding underscores the RmsdXNA’s ability to accurately predict RMSD values.

0.00115. This finding underscores the RmsdXNA’s ability to accurately predict RMSD values.

Figure 2.

Performance of RmsdXNA and its comparison with rDock on the full validation dataset.

An effective score function should assign lower scores (better ranking) to the closest-to-native pose, which has a lower actual RMSD than the decoy poses. Therefore, the PCC (Equation 4) and SRCC (Equation 5) between the actual RMSD and scoring functions for each NA–ligand pair, which measure the correlations and ranking capabilities, respectively, are key metrics for evaluating their performance. Figure 2(b) and 2(c) illustrates each ligand’s distribution of the PCC and SRCC values respectively for both scoring methods. RmsdXNA has a higher average PCC and SRCC than rDock. In addition, RmsdXNA outperforms rDock for 1271/1434 (88.6%) and 1254/1434 (87.4%) ligands in terms of PCC and SRCC respectively. This comparison revealed that RmsdXNA has a stronger correlation and ranking capabilities than rDock for most of the ligand structures.

|

(4) |

where:

= Actual RMSD of pose

= Actual RMSD of pose

= Average actual RMSD of all poses

= Average actual RMSD of all poses

= Score of pose

= Score of pose

= Average score of all poses

= Average score of all poses

|

(5) |

where:

= ranking of pose based on RMSD (x)

= ranking of pose based on RMSD (x)

= ranking of pose based on score (s)

= ranking of pose based on score (s)

= number of poses

= number of poses

The ability of RmsdXNA and rDock to select close-to-native poses, defined by poses with RMSD  2.0, was also analyzed. Figure 2(d) shows that the fraction of ligands that contained close-to-native poses in the top-n-scored poses was greater for RmsdXNA. Additionally, out of all the ligands that are able to generate at least 1 close-to-native pose, 69.1%, 81.9% and 86.9% of the ligands for RmsdXNA and 45.9%, 62.0% and 70.8% of the ligands for rDock contained close-to-native poses in the top 1, 5, and 10 selected poses respectively. These results showed that RmsdXNA outperforms the rDock scoring function in pose identification.

2.0, was also analyzed. Figure 2(d) shows that the fraction of ligands that contained close-to-native poses in the top-n-scored poses was greater for RmsdXNA. Additionally, out of all the ligands that are able to generate at least 1 close-to-native pose, 69.1%, 81.9% and 86.9% of the ligands for RmsdXNA and 45.9%, 62.0% and 70.8% of the ligands for rDock contained close-to-native poses in the top 1, 5, and 10 selected poses respectively. These results showed that RmsdXNA outperforms the rDock scoring function in pose identification.

Ablation studies

Ablation experiments were conducted to investigate the impact of various modifications to dataset generation on the performance of the model. The modified dataset was used to train the model using the steps described in Section 2.4. The model with the highest  for each modified dataset was subsequently selected and compared across the different modifications.

for each modified dataset was subsequently selected and compared across the different modifications.

First, the effect of  on dataset generation was examined and the results are summarized in Table A5. As

on dataset generation was examined and the results are summarized in Table A5. As  varies from 4 to 10 Å, more interaction features are extracted and added to the dataset. New features with non-0 values may also be introduced into the dataset, increasing the number of columns of the dataset slightly. Previous studies by Szulc et al. [59] employed cutoff distances of 3.9 and 4.0 Å to detect hydrogen bonding and lipophilic interactions respectively in RNA complexes. However,

varies from 4 to 10 Å, more interaction features are extracted and added to the dataset. New features with non-0 values may also be introduced into the dataset, increasing the number of columns of the dataset slightly. Previous studies by Szulc et al. [59] employed cutoff distances of 3.9 and 4.0 Å to detect hydrogen bonding and lipophilic interactions respectively in RNA complexes. However,  = 8 Å gave the highest

= 8 Å gave the highest  of 0.68301

of 0.68301  0.02330. The improvement in the results from

0.02330. The improvement in the results from  = 4 to 8 Å may be due to the increase in the number of non-0 values in the dataset and the addition of new information for the model. Beyond certain distances, such as

= 4 to 8 Å may be due to the increase in the number of non-0 values in the dataset and the addition of new information for the model. Beyond certain distances, such as  = 9 and 10 Å, the added long-range and weak interaction may introduce noise to the data and additional information has insignificant contributions to the specific interaction between NA and ligand. Therefore, finding the optimal cutoff distance is vital for striking the right balance between capturing relevant interactions and avoiding unnecessary complexity in the dataset.

= 9 and 10 Å, the added long-range and weak interaction may introduce noise to the data and additional information has insignificant contributions to the specific interaction between NA and ligand. Therefore, finding the optimal cutoff distance is vital for striking the right balance between capturing relevant interactions and avoiding unnecessary complexity in the dataset.

Next, the effect of adding the rDock scoring components,  ,

,  and

and  features into the dataset was investigated. By generating datasets that combine these specific features, their contribution to the overall model performance can be evaluated and the best performing combinations can be determined. The results of the model with different combinations of features are shown in Table A6. The best result of

features into the dataset was investigated. By generating datasets that combine these specific features, their contribution to the overall model performance can be evaluated and the best performing combinations can be determined. The results of the model with different combinations of features are shown in Table A6. The best result of  = 0.68301

= 0.68301  0.02330 was achieved when the rDock scoring function components were added to the

0.02330 was achieved when the rDock scoring function components were added to the  and

and  features. The improved prediction accuracy suggests that the rDock components and the generated features complement each other effectively. Additionally, the analysis revealed that the

features. The improved prediction accuracy suggests that the rDock components and the generated features complement each other effectively. Additionally, the analysis revealed that the  component is less important than the

component is less important than the  and

and  components, as the

components, as the  of the model decreased to 0.67910

of the model decreased to 0.67910  0.01763 when the

0.01763 when the  component was added to the dataset. Wang et al. [41] explained that the short-range repulsive term,

component was added to the dataset. Wang et al. [41] explained that the short-range repulsive term,  , is not relevant because of the low occurrence of small-distance interactions in the NA–ligand complex. Although similar distance data are used to generate the feature values of

, is not relevant because of the low occurrence of small-distance interactions in the NA–ligand complex. Although similar distance data are used to generate the feature values of  ,

,  and

and  , the difference in the results suggests that proper data augmentation of the feature is needed to achieve high accuracy of the model.

, the difference in the results suggests that proper data augmentation of the feature is needed to achieve high accuracy of the model.

Finally, the impact of different atom representation methods when generating the dataset on  is summarized in Table A7. The use of the SYBYL atom type to represent receptor and ligand atoms, element type to represent receptor atoms with the ’OTH’ residue type, and other grouping methods mentioned in Appendix C, achieved the highest

is summarized in Table A7. The use of the SYBYL atom type to represent receptor and ligand atoms, element type to represent receptor atoms with the ’OTH’ residue type, and other grouping methods mentioned in Appendix C, achieved the highest  of 0.68301

of 0.68301  0.02330. This outperformed models that used a full element or SYBYL atom representation with

0.02330. This outperformed models that used a full element or SYBYL atom representation with  values of 0.66726

values of 0.66726  0.02244 and 0.67945

0.02244 and 0.67945  0.01654 respectively. Compared to DeepRMSD, which uses element atom representation, using the SYBYL atom type can distinguish aromatic and non-aromatic atoms. This allows the model to capture pi-stacking interactions between the NA receptor and ligand which are abundant in NA complexes [60]. Additionally, to handle sparse features involving NA modified residues atoms, binning them with other meaningful features can offer more instances for the model to learn from, while reducing the introduction of biased information.

0.01654 respectively. Compared to DeepRMSD, which uses element atom representation, using the SYBYL atom type can distinguish aromatic and non-aromatic atoms. This allows the model to capture pi-stacking interactions between the NA receptor and ligand which are abundant in NA complexes [60]. Additionally, to handle sparse features involving NA modified residues atoms, binning them with other meaningful features can offer more instances for the model to learn from, while reducing the introduction of biased information.

Feature importance analysis

Feature importance analysis was conducted to determine the relative importance of individual features in predicting RMSD in the model. The following training process uses the hyperparameter obtained from the best model. For each fold, the model is used to predict the RMSD of the ligands from the modified validating dataset where a specific ij pair feature ( and

and  ), or the rDock score component is artificially removed by setting all its values to 0. The change in the performance of the model was evaluated using

), or the rDock score component is artificially removed by setting all its values to 0. The change in the performance of the model was evaluated using  , which represents the difference in

, which represents the difference in  between the original validation dataset and the dataset with the removed columns. This process is repeated for all columns, and the features that result in a decrease in

between the original validation dataset and the dataset with the removed columns. This process is repeated for all columns, and the features that result in a decrease in  are identified as important, whereas those resulting in an increase in

are identified as important, whereas those resulting in an increase in  are considered less important. This analysis is performed for each fold, allowing the observation of feature importance across different iterations.

are considered less important. This analysis is performed for each fold, allowing the observation of feature importance across different iterations.

The analysis showed that certain features, such as aromatic interactions represented by the  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  features, have a significant impact on the model’s predictive capabilities as shown in Figure 3(a). On the other hand, some features yielded positive

features, have a significant impact on the model’s predictive capabilities as shown in Figure 3(a). On the other hand, some features yielded positive  values as shown in Figure 3(b), indicating that these features negatively affect the accuracy of the model. Despite the recognized importance of polar interactions in NA–ligand systems, the SCORE.INTER.POLAR term, which represents the intermolecular polar interaction score from rDock, showed the lowest importance. This may be due to its redundancy with the more effective capture of similar polar interactions by

values as shown in Figure 3(b), indicating that these features negatively affect the accuracy of the model. Despite the recognized importance of polar interactions in NA–ligand systems, the SCORE.INTER.POLAR term, which represents the intermolecular polar interaction score from rDock, showed the lowest importance. This may be due to its redundancy with the more effective capture of similar polar interactions by  and

and  terms, potentially rendering the SCORE.INTER.POLAR term obsolete. The other low importance features are typically sparse in the dataset. For example, all the features involving highly sparse selenium (Se) atom interactions, with an average of 0.0494% non-0 instances in the dataset, did not reduce the accuracy of the model when they were removed.

terms, potentially rendering the SCORE.INTER.POLAR term obsolete. The other low importance features are typically sparse in the dataset. For example, all the features involving highly sparse selenium (Se) atom interactions, with an average of 0.0494% non-0 instances in the dataset, did not reduce the accuracy of the model when they were removed.

Figure 3.

Change in  between the original validating dataset and the dataset with the removed column,

between the original validating dataset and the dataset with the removed column,  . Features with

. Features with  < 0 in Figure 2(a) represents a poorer performance of the model after removing the feature, while features with

< 0 in Figure 2(a) represents a poorer performance of the model after removing the feature, while features with  > 0 in Figure 3(b) represents an improvement in performance of the model after removing the feature.

> 0 in Figure 3(b) represents an improvement in performance of the model after removing the feature.

The RmsdXNA model incorporates additional interaction terms that are not typically included in other ML models for NA–ligand systems, such as interactions involving metal and modified residue atoms. According to our feature analysis, the average  of features containing receptor metals, ligand metals and modified residue atom (atoms with ’OTH’ residues) interactions are

of features containing receptor metals, ligand metals and modified residue atom (atoms with ’OTH’ residues) interactions are  ,

,  and

and  respectively. The negative average

respectively. The negative average  values indicate the importance of including these interactions for improved model accuracy. Although these values are minor compared to the

values indicate the importance of including these interactions for improved model accuracy. Although these values are minor compared to the  achieved by the model, keeping these features allows for the incorporation of datasets with rare features in the future, contributing to the model’s ability to learn from diverse information.

achieved by the model, keeping these features allows for the incorporation of datasets with rare features in the future, contributing to the model’s ability to learn from diverse information.

Model performance across data points

The performance of RmsdXNA was assessed by examining its PCC values with respect to different ligand structures. This study aims to understand whether ligands with similar PCC values share common structural features that contribute to their performance variation. The structures of the ligands with the highest and lowest PCC values were selected for analysis.

Generally, RmsdXNA tends to give lower scores (better rankings) to poses that have more interaction contact with the receptor, such as poses that are deeper in the receptor surface pocket or intercalate between receptor surfaces. Therefore, scoring accuracy decreases for those in which the docking pocket deviates from the native ligand position, such as 2HO6 and 1M69 (Figure 4(a) and 4(b)). In the case of 2HO6, the docked poses from the 2 nearby ligands are generated within the same pocket. However, the results show significant disparity, with one achieving a PCC of 0.958, and the other achieving a PCC of -0.918. This poor performance may be caused by the model using the wrong native ligand pose as a reference when predicting the RMSD of the docked pose. Therefore, removing nearby ligands from the dataset is important for preventing such situations.

Figure 4.

Ligands with high PCC values of the actual vs. predicted RMSD shown in red. For structures that contain multiple ligands, the ligands with high PCC values are shown in green.

In addition, ligands with fused aromatic ring systems that are between the receptor residues tend to have low PCCs, such as 7N7D and 7MSV (Figure 4(c) and Figure 4(d) respectively). From the structure of 7N7D, the ligands that are on the outer surface of the receptor demonstrated better performance than those that are between the receptor surface. This observation suggests that it is difficult for the model to accurately predict the RMSD of docking poses for ligands with extended aromatic rings. One possible explanation is the excessive number of interactions surrounding the ligand, which could introduce noise into the model.

Conversely, ligands with hypoxanthine-like and ruthenium polypyridyl-like complex structures tend to give better results (Table A8). This could be due to the high frequency of such ligands in the dataset, which allows the model to gain better prediction capabilities and understanding of the interactions for this ligand class. Therefore, the performance of the model can be improved by providing a more diverse training dataset.

The ranking capability of RmsdXNA was analyzed for different groups of structures, such as structures solved using NMR vs. X-ray diffraction, and complexes involving DNA, RNA or RNA–DNA hybrid receptors. The average PCC of the ligands for each different group is shown in Table 1. For all the different groups of structures, the PCC and SRCC of RmsdXNA outperformed that of rDock. These findings reinforce the reliability and robustness of RmsdXNA across the different groups.

Table 1.

The average PCC and SRCC of the actual RMSD vs. RmsdXNA and rDock’s scoring functions of the poses of each ligands are summarized in this table. The PCC and SRCC are categorized by their structure solving method using NMR and X-ray diffraction, and by their receptor types of DNA, RNA and RNA–DNA hybrid, with bold values representing better performance among the scoring functions.

| Structure solving | No. of | Average PCC of ligand | Average SRCC of ligand | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| method | structures | RmsdXNA | rDock | RmsdXNA | rDock |

| NMR | 178 |

0.43016  0.35800 0.35800

|

0.25019  0.32280 0.32280 |

0.35788  0.3453 0.3453

|

0.21064  0.31150 0.31150 |

| X-ray diffraction | 1256 |

0.67580  0.35295 0.35295

|

0.24267  0.32234 0.32234 |

0.61679  0.34101 0.34101

|

0.24267  0.32234 0.32234 |

| No. of | Average PCC of ligand | Average SRCC of ligand | |||

| Receptor type | structures | RmsdXNA | rDock | RmsdXNA | rDock |

| DNA | 575 |

0.56084  0.39992 0.39992

|

0.26301  0.34507 0.34507 |

0.51012  0.39238 0.39238

|

0.23920  0.33165 0.33165 |

| RNA | 841 |

0.71087  0.31031 0.31031

|

0.23422  0.30581 0.30581 |

0.64222 0.30092 0.30092

|

0.20328  0.29235 0.29235 |

| DNA-RNA hybrid | 16 |

0.38890  0.51146 0.51146

|

0.05664  0.26279 0.26279 |

0.37680  0.50930 0.50930

|

0.074360  0.25892 0.25892 |

Evaluation on the test dataset

The model is evaluated using a testing dataset consisting of 125 out of 140 PDB structures (Appendix N) from various sources, Yan [46], Ruiz [18], Chen [61] and Philips [62], similar to the test dataset used in Feng et al. [19]. These datasets primarily comprise complexes of DNA and RNA receptors with small molecules and peptide ligands. The remaining 15 PDB structures in the testing dataset were not used because of the selection criteria, as described in Appendix B. In addition, the remaining 1309 PDB structures from the full dataset were used for training the model using the best model’s hyperparameter values.

The results of the evaluation of RmsdXNA’s prediction on the testing datasets are shown in Figure 5. For all the testing datasets, a strong correlation between the predicted RMSD and the actual RMSD of the docked poses of 0.67228 to 0.85120 was obtained. Based on the PCC and SRCC values of each ligand and the fraction of ligands for which the top-n-pose had an RMSD  2.0 Å, RmsdXNA outperformed rDock in terms of ranking capability and pose selection. The ability of each docking tool in selecting close-to-native poses in the top scoring poses was also compared. For PDB structures that were not found in our dataset, it is assumed that RmsdXNA is unable to predict the close-to-native pose for that ligand. For PDB structures containing multiple ligands, the pose that gave the lowest RMSD was used for evaluation. RmsdXNA achieved the highest success rate compared to the other tools for all the testing datasets as shown in Table 2. Overall, RmsdXNA’s scoring accuracy outperforms that of existing docking tools for various unseen datasets and it is more capable of identifying the correct docking pose for NA–ligand complexes.

2.0 Å, RmsdXNA outperformed rDock in terms of ranking capability and pose selection. The ability of each docking tool in selecting close-to-native poses in the top scoring poses was also compared. For PDB structures that were not found in our dataset, it is assumed that RmsdXNA is unable to predict the close-to-native pose for that ligand. For PDB structures containing multiple ligands, the pose that gave the lowest RMSD was used for evaluation. RmsdXNA achieved the highest success rate compared to the other tools for all the testing datasets as shown in Table 2. Overall, RmsdXNA’s scoring accuracy outperforms that of existing docking tools for various unseen datasets and it is more capable of identifying the correct docking pose for NA–ligand complexes.

Figure 5.

Result of the testing dataset. Figures in column a) shows the predicted vs. actual RMSD of the ligand pose; b) shows the PCC distribution of the ligands; c) shows the SRCC distribution of the ligands; d) shows the fraction of ligands in the top-scored n poses that contains the pose with the lowest RMSD. Row 1, 2, 3 and 4 represents results from the Yan, Ruiz, Chen and Philips dataset respectively.

Table 2.

Number of PDB structures where the top 1 or top 5 poses selected by the different docking programs in flexible–ligand docking, contain poses with RMSD  2 Å on the 4 test sets of diverse NA–ligand complexes. The results from NLDock, AutoDock, rDock (NLDock) and DOCK 6 are obtained from Feng et al. [19]. For RmsdXNA and rDock, only ligands that are selected as described in Section 2.1 are used in this evaluation.AU: Please provide suitable wording for the table footnote to give the meaning of the bold values given in Table 2 directly in the text.

2 Å on the 4 test sets of diverse NA–ligand complexes. The results from NLDock, AutoDock, rDock (NLDock) and DOCK 6 are obtained from Feng et al. [19]. For RmsdXNA and rDock, only ligands that are selected as described in Section 2.1 are used in this evaluation.AU: Please provide suitable wording for the table footnote to give the meaning of the bold values given in Table 2 directly in the text.

Top1 pose with rmsd  2.0 Å 2.0 Å |

Top5 pose with rmsd  2.0 Å 2.0 Å |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method | Yan | Ruiz | Chen | Philips | Yan | Ruiz | Chen | Philips |

| RmsdXNA | 37 | 21 | 28 | 14 | 43 | 25 | 32 | 16 |

| rDock | 33 | 10 | 15 | 9 | 36 | 21 | 26 | 16 |

| NLDock | 28 | 9 | 14 | 11 | 36 | 15 | 22 | 15 |

| AutoDock | 10 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 14 | 2 | 5 | 2 |

| rDock (NLDock) | 24 | 8 | 10 | 8 | 29 | 9 | 14 | 10 |

| DOCK 6 | 24 | 6 | 8 | 5 | 30 | 6 | 9 | 5 |

Scoring power comparison validated by MST experiment

The comparison between rDock and RmsdXNA scores was validated using the in-vitro results of MST on  PAN triplex by Swain et al. [42]. The scores of the best poses selected by each scoring function are summarized in Table A10 and A11. For the hit compounds, RmsdXNA achieved SRCC = 0.39286 and ranks Compound 15 at 4/7, slightly outperforming rDock’s result of SRCC = 0.21429 and ranking Compound 15 at 5/7. Comparing the scores of Compound 15 and its modification counterparts, RmsdXNA ranks Compound 15 at a better rank of 2/4, whereas rDock rank Compound 15 at 4/4. These results validate that RmsdXNA’s ability to distinguish strong from weak binders and its ligand screening capability is better than that of rDock.

PAN triplex by Swain et al. [42]. The scores of the best poses selected by each scoring function are summarized in Table A10 and A11. For the hit compounds, RmsdXNA achieved SRCC = 0.39286 and ranks Compound 15 at 4/7, slightly outperforming rDock’s result of SRCC = 0.21429 and ranking Compound 15 at 5/7. Comparing the scores of Compound 15 and its modification counterparts, RmsdXNA ranks Compound 15 at a better rank of 2/4, whereas rDock rank Compound 15 at 4/4. These results validate that RmsdXNA’s ability to distinguish strong from weak binders and its ligand screening capability is better than that of rDock.

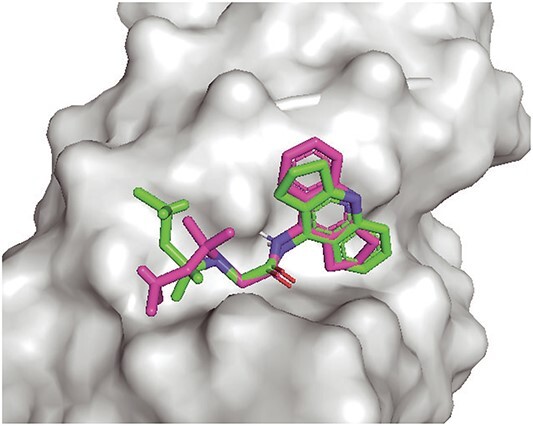

The best poses of Compound 15 selected by RmsdXNA and rDock are shown in Figure 6, differentiated by the direction that the extended five carbon ring is pointing: it is pointing away from the receptor for RmsdXNA, but pointing towards the receptor for rDock’s best pose. The MD trajectory of Compound 15 is more stable when using the initial pose selected by RmsdXNA, indicating a closer resemblance between the actual binding mode of Compound 15 and the best pose selected by RmsdXNA. The difference in the stability of the ligand trajectories highlights the importance of selecting initial structures using the docking score to enhance the reliability of MD simulations.

Figure 6.

Best pose selected by RmsdXNA (green) and rDock (pink) on  PAN triplex RNA.

PAN triplex RNA.

Screening application validated with MD simulations

The screening power of RmsdXNA and rDock for VS application on MALAT1 was compared by evaluating the MD trajectories of the top ligands selected by each scoring function. RmsdXNA was able to identify about 6 times more stable ligands out of 20 top-scored ligands compared to rDock as shown in Table 3. This finding suggests that RmsdXNA has a higher success rate in identifying potential ligands that binds strongly to the receptor, making it more accurate and reliable for screening. Interestingly, no common top candidate ligands were identified by RmsdXNA and rDock. From the top poses selected by RmsdXNA and rDock as illustrated in Figure 7, it is observed that RmsdXNA tends to give better scores to poses that intercalate between the RNA residues, but no such poses are selected by rDock. This indicates that a change in the score function can result in different outputs. The ability to accurately identify stable ligands is crucial for selecting reliable docking tools and refining computational docking protocols. By improving the efficiency and success rate of VS-related efforts in drug discovery, RmsdXNA can greatly impact the field.

Table 3.

Number of stable ligands from the 20 top-scored ligands selected by RmsdXNA and rDock during the MD simulation of 100 ns. The Chembridge and Life Chemicals screening compound libraries were used for the VS.

| Dataset | Number of stable ligands based on MD simulations | |

|---|---|---|

| RmsdXNA | rDock | |

| Chembridge | 13 | 2 |

| Life chemicals | 12 | 2 |

Figure 7.

Poses of the top 20 ligand selected by RmsdXNA and rDock from Chembridge and Life Chemicals screening libraries docked on 4PLX using rDock. Top-scored ligand poses selected by RmsdXNA tend to intercalate between the RNA residues. This is not observed for the top-scored ligands selected by rDock.

Limitations

In this study, RmsdXNA was evaluated and trained on ligand poses generated by local docking, excluding poses with RMSD  10 Åfrom the native pose. This exclusion may limit the functionality of RmsdXNA when the docking pocket is unknown, but it is necessary to reduce noise in the dataset during training and evaluation [63]. RmsdXNA is expected to perform well if docking tools can accurately generate close-to-native ligand poses or address the flexibility issue of the receptor as discussed in Stefaniak and Bujnicki [36]. Furthermore, tools that identify RNA-ligand binding sites [64], can be used in conjunction with RmsdXNA to accurately identify the docking pocket.

10 Åfrom the native pose. This exclusion may limit the functionality of RmsdXNA when the docking pocket is unknown, but it is necessary to reduce noise in the dataset during training and evaluation [63]. RmsdXNA is expected to perform well if docking tools can accurately generate close-to-native ligand poses or address the flexibility issue of the receptor as discussed in Stefaniak and Bujnicki [36]. Furthermore, tools that identify RNA-ligand binding sites [64], can be used in conjunction with RmsdXNA to accurately identify the docking pocket.

The small number of experimentally determined NA–ligand complexes presents a challenge for improving the ML model for NA docking tools. Infrequent feature interaction also hinder the model from learning this information effectively. However, the advantages of easy feature extraction and adaptability to different datasets presented in RmsdXNA simplify the addition of new data points to enhance the accuracy of the model. While RmsdXNA demonstrated overall better results than rDock in validation against  PAN triplex MST experiment and MD simulations validation of MALAT1 VS, a wider variety of experimental dataset involving diverse receptors is required to comprehensively evaluate the reliability of the scoring functions for virtual screening and pose identification.

PAN triplex MST experiment and MD simulations validation of MALAT1 VS, a wider variety of experimental dataset involving diverse receptors is required to comprehensively evaluate the reliability of the scoring functions for virtual screening and pose identification.

CONCLUSION

RmsdXNA, a ML regression model, was successfully developed and demonstrated to be an effective tool for predicting the RMSD of docked ligand poses in NA complexes. The model incorporates distance-based features that capture atom-atom interactions in NA complexes, including those containing metal ions, modified residues, and peptide ligands. The experiments showed that there is a correlation between the binding affinity and the predicted RMSD of a ligand pose, which can be used for pose identification and screening. RmsdXNA outperformed the other docking tools when evaluated on the testing dataset. It also achieved high prediction accuracy with an average validation  of 0.68301

of 0.68301  0.02330 and an average PCC of 0.64531

0.02330 and an average PCC of 0.64531  0.36262 and SRCC of 0.58465

0.36262 and SRCC of 0.58465  0.3519 across the different ligands. The alignment of the scoring ranking with the result of the MST experiments conducted on

0.3519 across the different ligands. The alignment of the scoring ranking with the result of the MST experiments conducted on  PAN triplex validated RmsdXNA’s better capability than rDock in distinguishing strong binders from weaker binders. RmsdXNA also has a higher success rate in identifying good ligand candidates for VS, supported by the MD simulations of MALAT1. Overall, this study demonstrated that ML can be utilized to improve the accuracy of molecular docking methodologies in the field of computational drug design.

PAN triplex validated RmsdXNA’s better capability than rDock in distinguishing strong binders from weaker binders. RmsdXNA also has a higher success rate in identifying good ligand candidates for VS, supported by the MD simulations of MALAT1. Overall, this study demonstrated that ML can be utilized to improve the accuracy of molecular docking methodologies in the field of computational drug design.

Author contributions

L.H. was responsible for carrying out all the experimental work, data collection and analysis. Y.G. provided valuable guidance and advice on the methods used in this project, contributing to the overall design and approach. C.K. contributed expertise in data analysis and machine learning modeling, offering insightful advice throughout the analysis phase. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Key Points

The intermolecular atom-atom pairwise distance of docking poses, r, were used to generate

and

and  features, which were subsequently used to construct the dataset for training the machine learning model. The model, namely RmsdXNA, is trained on 980 nucleic acid (NA)–ligand complex structure dataset using the XGBoostRegressor algorithm to predict the root-mean-square-deviation (RMSD) of a docked pose.

features, which were subsequently used to construct the dataset for training the machine learning model. The model, namely RmsdXNA, is trained on 980 nucleic acid (NA)–ligand complex structure dataset using the XGBoostRegressor algorithm to predict the root-mean-square-deviation (RMSD) of a docked pose.Modification of the features used in Wang et al. [41] allows us apply these features from protein–ligand complexes to NA–ligand complex systems in RmsdXNA. The results show successful application of RmsdXNA to various NA–ligand complexes, including different types of NA receptors and ligands.

The RMSD predicted by RmsdXNA outperforms rDock score in pose identification when evaluated on the testing dataset used in Feng et al. [19].

RmsdXNA demonstrated better scoring power and pose identification than rDock, using the binding affinities of small molecules on polyadenylated nuclear (PAN) triplex RNA obtained by microscale thermophoresis (MST).

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation on MALAT1–ligand complex was performed to validate the binding of the top ligand candidates selected by RmsdXNA and rDock during virtual screening. The results showed that RmsdXNA had a higher success rate in selecting stable ligands by approximately 6 times.

A Appendix

Appendix A. PDB list

The list of PDB structures from NDB used for docking are shown in the list below. The PDB IDs in red are not used in the dataset as the ligands were docked unsuccessfully, where there are fewer than 100 poses out of 400 dock attempts with RMSD  10Å.

10Å.

| 100D | 101D | 102D | 108D | 109D | 110D | 121D | 127D | 128D | 129D | 130D | 131D | 144D | 151D | 152D | 154D |

| 159D | 166D | 173D | 182D | 185D | 193D | 195D | 198D | 1AGL | 1AJU | 1AKX | 1AL9 | 1AM0 | 1AMD | 1ARJ | 1AW4 |

| 1BYJ | 1C9Z | 1CX3 | 1D10 | 1D11 | 1D14 | 1D17 | 1D21 | 1D22 | 1D30 | 1D32 | 1D36 | 1D37 | 1D38 | 1D43 | 1D44 |

| 1D45 | 1D46 | 1D48 | 1D54 | 1D58 | 1D63 | 1D64 | 1D67 | 1D85 | 1D86 | 1DA0 | 1DA9 | 1DB6 | 1DCR | 1DDY | 1DJ6 |

| 1DL8 | 1DNE | 1DNH | 1DNS | 1DPL | 1DSC | 1DSD | 1DVL | 1EDR | 1EEL | 1EHT | 1EI2 | 1EI4 | 1EM0 | 1ET4 | 1EVV |

| 1F1T | 1F27 | 1F6C | 1FD5 | 1FDG | 1FMN | 1FMQ | 1FMS | 1FN2 | 1FQ2 | 1FTD | 1FUF | 1FYP | 1G3X | 1G4Q | 1G5L |

| 1GJ2 | 1I0T | 1I1P | 1I2X | 1I2Y | 1I3W | 1I5V | 1I7J | 1I9V | 1IMR | 1IMS | 1J7T | 1JO2 | 1JTL | 1JUX | 1K2L |

| 1K2Z | 1K9G | 1KCI | 1KGK | 1KOC | 1KOD | 1KVH | 1L0R | 1L1H | 1L1V | 1LC4 | 1LEX | 1LEY | 1LVJ | 1M69 | 1MP7 |

| 1MTG | 1MWL | 1MXK | 1N37 | 1N7A | 1N7B | 1NAB | 1NBK | 1NEM | 1NJN | 1NTA | 1NTB | 1NZM | 1O15 | 1O9M | 1OE5 |

| 1OFX | 1OLD | 1OVF | 1P96 | 1P9X | 1PBR | 1PIK | 1PQQ | 1PRP | 1PWF | 1Q8N | 1Q9X | 1QCH | 1QD3 | 1QSX | 1QV4 |

| 1QV8 | 1R4E | 1R68 | 1RAW | 1S2R | 1TN2 | 1TOB | 1UNJ | 1UNM | 1UTS | 1UUD | 1UUI | 1VRO | 1VS2 | 1VTG | 1VTH |

| 1VTI | 1VTJ | 1VZK | 1WOE | 1X95 | 1XCS | 1XPF | 1XVR | 1Y0Q | 1Y26 | 1Y27 | 1Y84 | 1Y8L | 1YKV | 1YLS | 1YRJ |

| 1YYO | 1Z3F | 1Z58 | 1Z5T | 1Z8V | 1ZJG | 1ZPH | 1ZPI | 1ZZ5 | 202D | 206D | 209D | 210D | 211D | 215D | 216D |

| 217D | 224D | 227D | 231D | 234D | 236D | 245D | 248D | 258D | 261D | 263D | 264D | 267D | 268D | 269D | 276D |

| 278D | 282D | 288D | 289D | 292D | 293D | 296D | 298D | 2A04 | 2A5R | 2ADW | 2ARG | 2AU4 | 2B0K | 2B2B | 2B3E |

| 2B57 | 2BE0 | 2BEE | 2CKY | 2D47 | 2D55 | 2DA8 | 2DBE | 2DCG | 2DND | 2DYW | 2EES | 2EET | 2EEU | 2EEV | 2EEW |

| 2ELG | 2ESI | 2ESJ | 2ET0 | 2ET3 | 2ET4 | 2ET8 | 2EZF | 2EZG | 2F4S | 2F4T | 2F4U | 2F8W | 2FCX | 2FCY | 2FCZ |

| 2FD0 | 2G5K | 2G9C | 2GB9 | 2GCV | 2GDI | 2GIS | 2GJB | 2GVR | 2GWA | 2GYX | 2H0W | 2H0Z | 2HO6 | 2HO7 | 2HOJ |

| 2HOM | 2HOO | 2HOP | 2HRI | 2I2I | 2I5A | 2IE1 | 2JUK | 2JWQ | 2KD4 | 2KGP | 2KMJ | 2KTZ | 2KU0 | 2KX8 | 2KXM |

| 2L1V | 2L7V | 2L8H | 2L94 | 2LLJ | 2LWH | 2LWK | 2M4Q | 2MB3 | 2MCC | 2MCO | 2MG8 | 2MGN | 2MIY | 2MS6 | 2MXS |

| 2N0J | 2N6C | 2N96 | 2NEO | 2NLM | 2NZ4 | 2O1I | 2O3V | 2O3W | 2O3X | 2O3Y | 2O43 | 2O45 | 2OE5 | 2OE8 | 2OEY |

| 2OYQ | 2PIK | 2PL8 | 2PWT | 2QWY | 2R2U | 2RF3 | 2TOB | 2TRA | 2XNW | 2XNZ | 2XO1 | 2YDH | 2YGH | 2YIE | 2Z74 |

| 2Z75 | 302D | 303D | 304D | 305D | 306D | 308D | 311D | 316D | 319D | 320D | 321D | 323D | 324D | 326D | 328D |

| 336D | 352D | 355D | 358D | 360D | 367D | 375D | 385D | 386D | 3AJK | 3AJL | 3B4A | 3B4B | 3B4C | 3BNQ | 3BNR |

| 3C3Z | 3C44 | 3C5D | 3C7R | 3CCO | 3CDM | 3CE5 | 3D0U | 3D2G | 3D2V | 3D2X | 3DIG | 3DIL | 3DIM | 3DIO | 3DIQ |

| 3DIR | 3DIX | 3DIY | 3DIZ | 3DJ0 | 3DJ2 | 3DS7 | 3DVV | 3E5C | 3E5E | 3E5F | 3EGZ | 3EM2 | 3EQW | 3ERU | 3ES0 |

| 3ET8 | 3EUI | 3EUM | 3EY0 | 3EY2 | 3EY3 | 3F2Q | 3F2T | 3F2W | 3F2X | 3F2Y | 3F30 | 3F4E | 3F4G | 3F4H | 3FO4 |

| 3FO6 | 3FT6 | 3FU2 | 3FWO | 3FX8 | 3G4M | 3G8T | 3G96 | 3G9C | 3GAO | 3GCA | 3GER | 3GES | 3GJH | 3GJJ | 3GOG |

| 3GOT | 3GSJ | 3GSK | 3GX2 | 3GX3 | 3GX5 | 3GX6 | 3GX7 | 3I1D | 3I5L | 3IQN | 3IQR | 3IRW | 3JQ4 | 3K1V | 3L3C |

| 3LA5 | 3MIJ | 3MUM | 3MUR | 3MUT | 3MUV | 3MXH | 3N4O | 3NP6 | 3NPN | 3NPQ | 3NX5 | 3NYP | 3NZ7 | 3OIE | 3OMJ |

| 3OZ3 | 3OZ5 | 3Q3Z | 3Q50 | 3QCR | 3QF8 | 3QRN | 3QSC | 3QSF | 3RKF | 3S4P | 3SC8 | 3SD3 | 3SKI | 3SKL | 3SKR |

| 3SKT | 3SKW | 3SKZ | 3SLM | 3SLQ | 3SUH | 3SUX | 3T5E | 3TD1 | 3TZR | 3U05 | 3U08 | 3U0U | 3U38 | 3U4M | 3UVF |

| 3UXW | 3UYB | 3UYH | 3V7E | 3WRU | 403D | 407D | 410D | 428D | 432D | 442D | 443D | 447D | 448D | 449D | 452D |

| 453D | 454D | 459D | 465D | 473D | 474D | 482D | 4AGZ | 4AH0 | 4AH1 | 4AOB | 4B5R | 4BZT | 4BZU | 4BZV | 4D9X |

| 4D9Y | 4DA3 | 4DAQ | 4E1U | 4E7Y | 4E8K | 4E8M | 4E8N | 4E8P | 4E8Q | 4E8R | 4E8S | 4E8T | 4E8V | 4E8X | 4E95 |

| 4ERJ | 4ERL | 4F8U | 4F8V | 4FAQ | 4FAR | 4FAU | 4FAW | 4FAX | 4FB0 | 4FE5 | 4FEJ | 4FEL | 4FEN | 4FEO | 4FEP |

| 4FRG | 4FRN | 4FXM | 4G0F | 4GPW | 4GPX | 4GPY | 4GQJ | 4GXY | 4HIF | 4HQI | 4I9V | 4IJ0 | 4ITD | 4JD8 | 4JF2 |

| 4JIY | 4K31 | 4K32 | 4KQY | 4KZD | 4L5K | 4L81 | 4LTF | 4LTG | 4LTH | 4LTI | 4LTJ | 4LTK | 4LTL | 4LVV | 4LVW |

| 4LVX | 4LVY | 4LVZ | 4LW0 | 4LX5 | 4LX6 | 4M3I | 4M3V | 4MJ9 | 4MS5 | 4NFO | 4NYA | 4NYB | 4NYC | 4NYD | 4NYG |

| 4O5W | 4O5X | 4OQU | 4P1D | 4P20 | 4P3S | 4P5J | 4P95 | 4PDQ | 4Q9Q | 4Q9R | 4QIO | 4QK8 | 4QK9 | 4QKA | 4QLM |

| 4QLN | 4QVI | 4R4A | 4R8J | 4RE7 | 4RZD | 4TS0 | 4TS2 | 4TZX | 4TZY | 4U8A | 4U8B | 4U8C | 4W90 | 4W92 | 4X18 |

| 4X1A | 4XNR | 4XW7 | 4XWF | 4Y1I | 4Y1J | 4Y1M | 4YAZ | 4YB0 | 4YMC | 4ZC7 | 4ZNP | 5BJO | 5BJP | 5BTP | 5C45 |

| 5C7U | 5C7W | 5CCW | 5CDB | 5D5L | 5DAM | 5DE5 | 5DHB | 5ET2 | 5FK1 | 5FK4 | 5FK5 | 5FK6 | 5FKE | 5FKF | 5FKG |

| 5FKH | 5HBW | 5HIX | 5IP8 | 5IU5 | 5IWJ | 5JEU | 5JEV | 5JLW | 5KPY | 5KRG | 5KVJ | 5KX9 | 5L00 | 5LFS | 5LFW |

| 5LFX | 5LIG | 5LIT | 5LWJ | 5MVB | 5NPM | 5O62 | 5O69 | 5OB3 | 5SWE | 5T4W | 5T83 | 5TPY | 5UED | 5UEE | 5UX3 |

| 5UZA | 5V0H | 5V0O | 5V1L | 5V3F | 5V9Z | 5VCF | 5VCI | 5VJ9 | 5VJB | 5W77 | 5XI1 | 5XJZ | 5XZ1 | 5Z1H | 5Z1I |

| 5Z71 | 5Z80 | 5Z8F | 5ZEI | 5ZEJ | 6AST | 6AZ4 | 6BFB | 6BNA | 6BST | 6C63 | 6C64 | 6C65 | 6C8E | 6C8K | 6C8L |

| 6C8M | 6C8O | 6CB3 | 6CC1 | 6CC3 | 6CCW | 6CHR | 6CIL | 6CK4 | 6CK5 | 6D8A | 6DB8 | 6DLQ | 6DLR | 6DLS | 6DLT |

| 6DMC | 6DMD | 6DME | 6DN1 | 6DN2 | 6DN3 | 6DY5 | 6E1S | 6E1U | 6E1V | 6E1W | 6E84 | 6E8T | 6E8U | 6FC9 | 6FZ0 |

| 6G7Z | 6G8S | 6GIM | 6GYV | 6GZK | 6GZR | 6HAG | 6HBT | 6HBX | 6HC5 | 6HMO | 6HWG | 6IJV | 6IJW | 6J0H | 6J2W |

| 6JBF | 6JBG | 6JJ0 | 6JJH | 6JJI | 6JWD | 6JWE | 6K3Y | 6KFI | 6KFJ | 6KFL | 6KN4 | 6KXZ | 6LNZ | 6M4T | 6M5B |

| 6M5J | 6N5K | 6N5N | 6N5O | 6N5P | 6N5Q | 6N5S | 6N5T | 6O2L | 6OD9 | 6P2H | 6P45 | 6PNK | 6PQ7 | 6Q57 | 6QIV |

| 6QN3 | 6R6D | 6RNL | 6RSO | 6RTI | 6S15 | 6S7D | 6SX3 | 6T3K | 6T3N | 6T3R | 6T3S | 6TB7 | 6TF0 | 6TF1 | 6TF2 |

| 6TF3 | 6TFE | 6TFF | 6TFG | 6TFH | 6U6J | 6U7Y | 6U7Z | 6U89 | 6U8F | 6U8U | 6UBU | 6UC7 | 6UC8 | 6UC9 | 6UP0 |

| 6V0L | 6V9D | 6VA2 | 6VA3 | 6VA4 | 6VMY | 6VUI | 6VWT | 6VWV | 6WTL | 6WTR | 6WZR | 6WZS | 6XB7 | 6XCL | 6XKN |

| 6XKO | 6XRQ | 6XT7 | 6YL5 | 6YLB | 6YMI | 6YMJ | 6YMK | 6YML | 6YMM | 7A3Y | 7ATG | 7CPS | 7CSK | 7D12 | 7D5E |

| 7D7W | 7D7X | 7D7Y | 7D7Z | 7D81 | 7D82 | 7DFY | 7DJU | 7DJV | 7DJW | 7DWH | 7E9E | 7E9I | 7EAF | 7EDL | 7EDM |

| 7EDT | 7EL7 | 7ELP | 7ELQ | 7ELR | 7ELS | 7EOG | 7EOH | 7EOI | 7EOJ | 7EOK | 7EOL | 7EOM | 7EON | 7EOO | 7EOP |

| 7FHI | 7FJ0 | 7JNH | 7KBW | 7KBX | 7KLP | 7KU4 | 7KUK | 7KUL | 7KUM | 7KUN | 7KUO | 7KUP | 7KVT | 7KVU | 7KVV |

| 7KWK | 7L0Z | 7LNE | 7LNF | 7LNG | 7MSV | 7N7D | 7N7E | 7OA3 | 7OAV | 7OAW | 7OAX | 7OTB | 7PNG | 7Q7X | 7Q7Y |

| 7Q7Z | 7Q80 | 7Q81 | 7Q82 | 7RWR | 7SZU | 7TD7 | 7TDA | 7TDB | 7TDC | 7TZR | 7TZS | 7TZT | 7TZU | 7V9E | 7W9N |

| 7WGW | 7X2Z | 7X3A | 7XLV | ||||||||||||

| 1AO1 | 1LEJ | 2RSK | 2RU7 | 4GMA | 5DE8 | 5ODF | 5ODM | 5OE1 | 6E8S | 6GZ7 | 6I4N | 6LEW | 6RIO | 7FGT | 7RIL |

Appendix B. Data refinement for data preparation

All NA molecules selected using bymolecule entity expansion and protein chains with masses greater than 1500 atomic units (au) were labeled as receptors. The protein receptor was removed during docking.

The following data refinements are performed for data preparation:

The remaining molecules that are not labeled as receptors, excluding solvent molecules

or molecules with fewer than 6 heavy atoms, are labeled as ligands.

or molecules with fewer than 6 heavy atoms, are labeled as ligands.A bond is added between an unbonded residue and the NA receptor if the distance between the atoms is

1.65 Å to fix the missing bond in the structure, and these residues are treated as the receptors.

1.65 Å to fix the missing bond in the structure, and these residues are treated as the receptors.Ligands with a mass larger than 1500 au were removed. This process filters away large ligands or proteins that are highly flexible and may act as noise for the model [63].

Ligands that were closer than (radius of gyration of ligand + 10 Å) from a protein receptor removed to exclude ligands with conformations that may be affected by nearby protein receptors.

In cases where the NA-ligand complexes contained multiple ligands, only ligands more than 4.0 Å from each other were used for docking, while the other ligands were removed from the dataset. This is because ligands that are nearby may influence each others’ native pose. The absence of nearby ligands when performing docking may undermine the accuracy of the model in predicting the RMSD of the docked poses. Additionally, identical ligands in close proximity may result in incorrect reference pose being used for predicting the RMSD of the docked pose if the docking pockets are nearby.

For structures with alternative conformations, the first variant is used for receptor atoms, while complexes with alternative conformations in the ligand are removed. This prevents the problem of having multiple references of the ligand’s native poses when measuring the RMSD of the docked poses.

Only the first model is used for structures solved using nuclear magnetic resonance.

Complexes without any valid ligand molecules were excluded from the experiment.

List of residue names of molecules that are labeled as solvent and not used as ligand for docking: 13D, 1PE, ACT, AGU, ARF, BA, BCT, BME, BR, CL, CON, CPT, DMS, EDO, EOH, FMT, GAI, GLY, GOL, GZ6, IPA, IRI, MGX, MOH, NCO, NRU, OHX, PDO, PGE, PO4, PTN, RHD, RUH, SE4, SEY, SO4, TEA, TMO, URE,

List of residue names of molecules that are labeled as solvent and not used as ligand for docking: 13D, 1PE, ACT, AGU, ARF, BA, BCT, BME, BR, CL, CON, CPT, DMS, EDO, EOH, FMT, GAI, GLY, GOL, GZ6, IPA, IRI, MGX, MOH, NCO, NRU, OHX, PDO, PGE, PO4, PTN, RHD, RUH, SE4, SEY, SO4, TEA, TMO, URE,

Appendix C. NA and ligand atom groups

Table A1.

Atom group of the receptor atoms in ’OTH’ residue group based on its SYBYL atom type. The atoms are grouped according to their element, while the halogens are grouped into a ’Hal’ group. For modified residues containing ’O.co2’ and ’P.3’ atoms, since these atoms appear in the backbone and ribose structure (N), ’N’ residue type is assigned to the receptor atoms containing ’O.co2’ and ’P.3’.

| Atom Group | SYBYL atom type |

|---|---|

| O | O.2, O.3 |

| C | C.2, C.3 |

| N | N.2, N.3, N.4, N.pl3 |

| Hal | Br, Cl, F, I |

Table A1 shows the grouping of the receptor atoms in 'OTH' residue group. For ligand atom type, C.cat (carbocation in a guadinium group) and C.2 (carbon sp2) SYBYL atom types are grouped together to form C2 atom group. C.cat in the ligand only appeared in 6 PDB structures, therefore binning the features formed by C.cat ligand can reduce the sparsity of the dataset and improve the result.

Table A2.

Atom types considered in feature generation. The SYBYL atom types of the canonical residues is based on the atom name of the atom as shown in Appendix E. Italicized atom types are grouped by the methods above shown in Appendix C. 24 ligand atom types for ligand and 26 NA atom types (unique combinations of the atom types that appear in each residue type) were used, resulting in 624 pair of interactions.

| Receptor | Ligand | |

|---|---|---|

| Residue | Atom type | Atom type |

| A | N.ar, C.ar, N.pl3 | C2, C.1, C.3, C.ar, Br, Cl, F, I, N.1, N.2, N.3, N.4, N.am, N.ar, N.pl3 O.2, O.3, O.co2, S.2, S.3, S.O2, P.3, Se, Metal |

| G | N.ar, C.ar, N.pl3, O.2 | |

| C | N.ar, C.ar, N.pl3, O.2 | |

| U/T | N.ar, C.ar, O.2, C.3 | |

| N | P.3, C.3, O.3, O.co2 | |

| OTH | O, C, N, Hal, Se, S.3 | |

| Metal | Metal | |

After grouping the receptor and ligand atom types as mentioned above, the atom type representations are shown in Table A2. Columns with all 0 values were removed from the dataset and used to train the model.

Appendix D. Residue type generalization

The generalization of modified NA residues into the unmodified NA residues based on structural similarity. For each modified residue structure, the atoms that are similar to the ”parent” nucleotide in terms of its position are represented in sticks (thicker) and the atoms are represented by SYBYL atom type for feature generation. On the other hand, the other modified atoms are represented in lines (thinner) and the atoms are represented by their element for feature generation. Visualization of the structures was performed using PyMol.

For new residues that are not shown in this section, similar residue generalization and atom representation methods can be applied for feature generation.

Appendix E. Atom name and SYBYL atom type of residues A, C, G, U/T

of receptor atom that are in the canonical nucleobase position is the classified RNA’s nucleobases group;

of receptor atom that are in the canonical nucleobase position is the classified RNA’s nucleobases group;  of receptor atom in the ribose and phosphate backbone is ’N’;

of receptor atom in the ribose and phosphate backbone is ’N’;  of the metal atoms in the receptor is ’Metal’, while

of the metal atoms in the receptor is ’Metal’, while  for the other atoms is ’OTH’.

for the other atoms is ’OTH’.  is represented by the SYBYL atom type based on its position as shown in Figure A1 and Table A3.

is represented by the SYBYL atom type based on its position as shown in Figure A1 and Table A3.

Figure A1.

The atom names of residues A, G, C, U/T.

Table A3.

The SYBYL atom type representation of the atoms in nucleobases A, C, G, U/T and the backbone (N) based on the atom’s position as shown in Figure A1

| Residue | SYBYL atom type | Atom name |

|---|---|---|

| A | N.ar | N1, N3, N7, N9 |

| C.ar | C2, C4, C5, C6, C8 | |

| N.pl3 | N6 | |

| G | N.ar | N1, N3, N7, N9 |

| C.ar | C2, C4, C5, C6, C8 | |

| O.2 | O6 | |

| N.pl3 | N2 | |

| C | N.ar | N1, N3 |

| C.ar | C2, C4, C5, C6 | |

| N.pl3 | N4 | |

| O.2 | O2 | |

| U/T | N.ar | N1, N3 |

| C.ar | C2, C4, C5, C6 | |

| O.2 | O2, O4 | |

| C.3 | C7 | |

| N | P.3 | P |

| C.3 | C5’, C1’, C2’, C3’, C4’ | |

| O.3 | O5’, O3’, O2’, O4’ | |

| O.co2 | OP1, OP2 |

Appendix F. Hyperparameter values for the best performing model

max_depth: 13, n_estimators: 900, min_child_weight: 5, learning_rate: 0.02, subsample: 0.3, colsample_bytree: 0.4, reg_alpha: 1, reg_lambda: 1, gamma:1, rate_drop: 0.3,

Appendix G. Best result of other ML models

Table A4.

The best  obtained for different algorithms. All algorithms perform worse than XGBoost, which has a

obtained for different algorithms. All algorithms perform worse than XGBoost, which has a  = 0.68301.

= 0.68301.

| Algorithm | Best

|

|---|---|

| Multilayer Perceptron | 0.43258 |

| AdaBoost | 0.41016 |

| Random Forest | 0.65553 |

| Support Vector Regression | 0.57900 |

Appendix H. MD simulation protocol

To prepare for the MD simulations, the force fields of the receptor and ligands were generated using AMBER [65]. Then, the AMBER topologies are converted to GROMACS [66] format using ANTECHAMBER [67] and ParmEd software [68] (https://github.com/ParmEd/ParmEd). MD simulations of the MALAT1-ligand complex in water with 0.15 M sodium chloride ions at 300 K and the TIP3P water model [69] were performed using GROMACS simulation software to generate a 100 ns trajectory.

Appendix I. Structure of screening compounds

Figure A2.

The atom names of residues A, G, C, U/T.

Appendix J. Ablation studies results - cutoff distance

Table A5.

Average validating  of actual vs. predicted ligand pose RMSD values,

of actual vs. predicted ligand pose RMSD values,  , trained on datasets generated using cutoff distance of 4 to 10 Å for feature generation. The

, trained on datasets generated using cutoff distance of 4 to 10 Å for feature generation. The  value and its standard deviation (std) is calculated from the validating

value and its standard deviation (std) is calculated from the validating  obtained from each fold in the 5-fold cross-validation training. nfeatures shows the number of features in the dataset, and the % 0 in dataset measures the sparsity of the dataset.

obtained from each fold in the 5-fold cross-validation training. nfeatures shows the number of features in the dataset, and the % 0 in dataset measures the sparsity of the dataset.

cutoff distance,

|

nfeature | % 0 in dataset (%) |

|

std |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 1040 | 92.1 | 0.64660 | 0.02483 |

| 5 | 1062 | 89.2 | 0.66621 | 0.02018 |

| 6 | 1072 | 86.9 | 0.67458 | 0.01980 |

| 7 | 1082 | 84.7 | 0.67742 | 0.01882 |

| 8 | 1088 | 83.1 | 0.68301 | 0.02330 |

| 9 | 1092 | 82.0 | 0.67929 | 0.01941 |

| 10 | 1098 | 81.3 | 0.68176 | 0.02061 |

Appendix K. Ablation studies results - feature combinations

Table A6.

Average validating  of actual vs. predicted ligand pose RMSD values,

of actual vs. predicted ligand pose RMSD values,  , trained using datasets generated using combinations of rDock,

, trained using datasets generated using combinations of rDock,  ,

,  and

and  features. rDock feature represent the components generated from rDock scoring function, while the

features. rDock feature represent the components generated from rDock scoring function, while the  ,

,  and

and  features represents the features used to describe the intermolecular force field energy as shown in Section 2.3.

features represents the features used to describe the intermolecular force field energy as shown in Section 2.3.

| Feature | nfeature |

|

std |

|---|---|---|---|

| rDock | 30 | 0.48328 | 0.03950 |

rDock +

|

559 | 0.66988 | 0.02106 |

rDock +

|

559 | 0.6737 | 0.02028 |

rDock +

|

559 | 0.66803 | 0.0210 |

rDock +  + +  (default) (default)

|

1088 | 0.68301 | 0.02330 |

rDock +  + +

|

1088 | 0.67798 | 0.01998 |

rDock +  + +

|

1088 | 0.67601 | 0.01964 |

rDock +  + +  + +

|

1619 | 0.67910 | 0.01763 |

+

+

|

1060 | 0.65344 | 0.02865 |

+

+  + +

|

1591 | 0.65241 | 0.02956 |

Appendix L. Ablation studies results - feature binning

Table A7.

Average validating  of actual vs. predicted ligand pose RMSD values,

of actual vs. predicted ligand pose RMSD values,  , for the best models from datasets generated by different atom representations. The receptor and ligand atoms are represented in either default (Appendix C), element, or SYBYL MOL2 format. The highest average validating

, for the best models from datasets generated by different atom representations. The receptor and ligand atoms are represented in either default (Appendix C), element, or SYBYL MOL2 format. The highest average validating  of 0.68301 is obtained for the default dataset.

of 0.68301 is obtained for the default dataset.

| Modification name | nfeature |

|

std | Atom representation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Receptor | Ligand | ||||

| atomgroup (default) | 1088 | 0.68301 | 0.02330 | Default | Default |

| ligandelem | 516 | 0.67128 | 0.02350 | Default | Element |

| ligandmol2 | 1126 | 0.68173 | 0.0206 | Default | SYBYL MOL2 |

| recelem | 850 | 0.67447 | 0.02168 | Element | Default |

| recmol2 | 1174 | 0.68209 | 0.0184 | SYBYL MOL2 | Default |

| ligandrecelem | 408 | 0.66726 | 0.02244 | Element | Element |

| ligandrecmol2 | 1256 | 0.67945 | 0.01654 | SYBYL MOL2 | SYBYL MOL2 |

Appendix M. Ligand analysis

Table A8.

List of ligands with similar structures and relatively high PCC between the actual RMSD of the poses and RmsdXNA predicted RMSD.