Keywords: somatosensory thalamus, synaptic transmission, thalamocortical neuron, ventral posterolateral nucleus, ventral posteromedial nucleus

Abstract

Somatosensory information is propagated from the periphery to the cerebral cortex by two parallel pathways through the ventral posterolateral (VPL) and ventral posteromedial (VPM) thalamus. VPL and VPM neurons receive somatosensory signals from the body and head, respectively. VPL and VPM neurons may also receive cell type-specific GABAergic input from the reticular nucleus of the thalamus. Although VPL and VPM neurons have distinct connectivity and physiological roles, differences in their functional properties remain unclear as they are often studied as one ventrobasal thalamus neuron population. Here, we directly compared synaptic and intrinsic properties of VPL and VPM neurons in C57Bl/6J mice of both sexes aged P25–P32. VPL neurons showed greater depolarization-induced spike firing and spike frequency adaptation than VPM neurons. VPL and VPM neurons fired similar numbers of spikes during hyperpolarization rebound bursts, but VPM neurons exhibited shorter burst latency compared with VPL neurons, which correlated with larger sag potential. VPM neurons had larger membrane capacitance and more complex dendritic arbors. Recordings of spontaneous and evoked synaptic transmission suggested that VPL neurons receive stronger excitatory synaptic input, whereas inhibitory synapse strength was stronger in VPM neurons. This work indicates that VPL and VPM thalamocortical neurons have distinct intrinsic and synaptic properties. The observed functional differences could have important implications for their specific physiological and pathophysiological roles within the somatosensory thalamocortical network.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY This study revealed that somatosensory thalamocortical neurons in the VPL and VPM have substantial differences in excitatory synaptic input and intrinsic firing properties. The distinct properties suggest that VPL and VPM neurons could process somatosensory information differently and have selective vulnerability to disease. This work improves our understanding of nucleus-specific neuron function in the thalamus and demonstrates the critical importance of studying these parallel somatosensory pathways separately.

INTRODUCTION

The corticothalamic (CT) network comprises a series of reciprocal loops between the cerebral cortex and thalamus that play essential roles in sensory, motor, emotional, and cognitive processing. The somatosensory CT circuit propagates somatic information from the periphery to the cortex through the ventrobasal (VB) thalamus and mediates oscillatory activity that regulates attention and sleep-wake cycles (1–4). Notably, somatic information from the body and the head is processed via two parallel pathways involving the ventral posterolateral (VPL) and ventral posteromedial (VPM) regions of the VB thalamus. These two somatosensory pathways make distinct contributions to sensory processing and oscillatory activity; however, the synaptic and cellular mechanisms underlying pathway-specific physiology and pathophysiology are not fully understood.

VPL neurons receive ascending somatosensory information from the body via the spinothalamic tract, whereas somatosensory information from the head is propagated to VPM neurons via the trigeminothalamic tract. Thalamocortical neurons in the VPL and VPM relay somatosensory information to the primary somatosensory cortex and layer 6 CT neurons return glutamatergic feedback to the VPL and VPM (5, 6). CT neurons, as well as VPL and VPM thalamocortical neurons, send collaterals to the reticular nucleus of the thalamus (nRT), a sheet of GABAergic neurons that provide the primary inhibitory input to VPL and VPM neurons (Fig. 1A). Both VPL and VPM neurons exhibit tonic and burst firing modes important for processing somatosensory information and generating intrathalamic oscillations through reciprocal connections with the nRT (7–9). However, the nRT-VPM loop might be more rhythmogenic than the nRT-VPL loop; this difference could be due to more robust connections between VPM neurons and parvalbumin (PV)-expressing nRT neurons (10) or distinct intrinsic properties of VPL and VPM neurons. Although numerous studies have investigated the physiological properties of the VB thalamus as a whole (11–20), it remains unclear if VPL and VPM neurons have differences in synaptic and cellular function that contribute to their distinct physiological roles.

Figure 1.

VPL neurons have a larger AHP period than VPM neurons. A: a somatosensory CT circuit diagram shows glutamatergic (+) and GABAergic (−) neuron connectivity as well as somatosensory inputs via the trigeminothalamic tract (TT) and spinothalamic tract (ST). B: cell locations for each current clamp recording in Figs. 1, 2, and 3 as well as Tables 1 and 2 were mapped on an image from a horizontal rat brain atlas (DV −3.1 mm relative to bregma). C: representative traces show AP trains elicited by depolarizing current injections. D: the recording periods above black lines in C were expanded and overlaid. E: recording periods above solid and dashed lines in D were expanded to show AP shape (solid box) and AHP period (dashed box). F–I: sample sizes are: VPL, n = 23 cells from 14 mice (7 females, 7 males); VPM: n = 23 cells from 13 mice (7 females, 6 males). Error bars are 95% CI. Estimation plots show data points for all cells with the group mean (black circle) plotted on the left axis, and the MD (open circle) plotted on the right axis. Welch’s t test statistics for AP amplitude (F), AP half-width (G), AHP amplitude (H), and AHP duration (I) are in Table 1. AHP, afterhyperpolarization; AP, action potential; CT, corticothalamic; VPL, ventral posterolateral; VPM, ventral posteromedial.

VB thalamus dysfunction, including pathological oscillatory activity, has been implicated in many diseases (21–28). However, the distinct connectivity and oscillatory activity of VPL and VPM neurons suggest the two neuron populations may differentially contribute to circuit dysfunction in disease. Indeed, rhythmic activity between nRT and VPM neurons has been proposed to make larger contributions to pathological oscillations during seizures (10). Furthermore, the tonic and burst firing properties of VPL and VPM neurons were differentially affected in a mouse model of Dravet syndrome (29). Disease states could impact VPL and VPM neuron function differently due to their distinct connectivity or unique intrinsic regulatory mechanisms.

Intrinsic and synaptic properties of VPL and VPM neurons have been studied individually, but there has been no direct systematic comparison (30, 31). Because these two populations receive unique inputs and respond differentially in some disease states, we hypothesized that VPL and VPM neurons have a unique physiology that contributes to their distinct roles in somatosensory CT circuit function. A thorough understanding of the synaptic and cellular properties of VPL and VPM neurons is essential to elucidate how they may uniquely process information and contribute to circuit function or dysfunction. Here, we report that VPL and VPM neurons have differences in excitatory and inhibitory synaptic input as well as tonic and burst firing properties. These findings broaden our understanding of nucleus-specific functional properties within the thalamus and suggest that distinct synaptic and cellular functions of VPL and VPM neurons might contribute to their specific physiological or pathophysiological roles.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of Mouse Brain Slices

Mouse studies were performed according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University and in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines. C57Bl/6J mice of both sexes aged P25–P32 were used for all experiments. Mice were housed in a 12-h light/dark cycle with ad libitum access to food and water. Mice were deeply anesthetized with an overdose of inhaled isoflurane and transcardially perfused with ice-cold sucrose-based artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) containing (in mM) 230 sucrose, 24 NaHCO3, 10 glucose, 3 KCl, 10 MgSO4, 1.25 NaH2PO4, and 0.5 CaCl2 saturated with 95% O2-5% CO2. The brain was removed and glued to a vibratome stage (Leica VT1200S). Horizontal 300-μm slices were cut in an ice-cold sucrose aCSF bath. Slices were hemisected and then incubated at 32°C for 30 min in a NaCl-based aCSF containing (in mM) 130 NaCl, 24 NaHCO3, 10 glucose, 3 KCl, 4 MgSO4, 1.25 NaH2PO4, and 1 CaCl2 saturated with 95% O2-5% CO2. The slices were then equilibrated to room temperature (RT) for 30 min and maintained at RT until used for recordings.

Electrophysiology

Recordings were made using a Multiclamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices), sampled at 20 kHz (Digidata 1550B, Molecular Devices), and low-pass filtered at 10 kHz using pClamp (RRID:SCR_011323). The extracellular recording solution contained (in mM) 130 NaCl, 24 NaHCO3, 10 glucose, 3 KCl, 1 MgSO4, 1.25 NaH2PO4, and 2 CaCl2 saturated with 95% O2-5% CO2 and was maintained at 32°C for all recordings. Slices were selected randomly for VPL or VPM recordings, and one cell was recorded per slice. Up to eight hemisected slices were recorded per mouse. No more than two cells from the same mouse were recorded for a single dataset to limit bias from any one animal.

For whole cell current-clamp recordings, borosilicate glass recording electrodes (4–5 MΩ) were filled with (in mM) 130 K-gluconate, 4 KCl, 2 NaCl, 10 HEPES, 0.2 EGTA, 4 ATP-Mg, 0.3 GTP-Tris, 14 phosphocreatine-K, and 0.1% biocytin, pH 7.3. Pipette capacitance neutralization and bridge balance were enabled. Membrane potential values were corrected for the liquid junction potential after the recording (15 mV). The resting membrane potential (RMP) was determined 2 min after breakthrough. All subsequent current-clamp experiments were conducted from an RMP of −75 ± 2 mV, which was maintained with a bias current (0–30 pA). To measure intrinsic membrane properties, voltage responses were elicited by 200-ms hyperpolarizing current injections between 20 and 100 pA (20 pA steps). Synaptic blockers APV (100 µM), NBQX (10 µM), and gabazine (10 µM) were washed into extracellular solution and applied for at least 5 min before current injection experiments. Depolarization-induced spike firing was elicited by 500-ms depolarizing current injections between 20 and 400 pA (20 pA steps). The goal of this experiment was to analyze depolarization-induced tonic firing properties; therefore, cells that fired high-frequency bursts of spikes at rheobase were excluded. Based on these criteria, three VPL cells and one VPM cell were excluded. Hyperpolarization-induced rebound bursting was elicited by 500-ms hyperpolarizing current injections between 50 and 400 pA (50 pA steps). Three trials were completed for each current injection experiment.

For whole cell voltage-clamp recordings, borosilicate glass recording electrodes (4–5 MΩ) were filled with (in mM) 120 CsMeSO3, 15 CsCl, 8 NaCl, 10 tetraethylammonium chloride, 10 HEPES, 1 EGTA, 3 Mg-ATP, 0.3 Na-GTP, 1.5 MgCl2, 1 QX-314, and 0.1% biocytin, pH 7.3. After a 10-min equilibration period, spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (sEPSCs) and spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents (sIPSCs) were recorded in 2-min epochs at a holding potential of −70 mV and 0 mV, respectively. Miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) and miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSCs) were recorded similarly in the presence of 1 µM tetrodotoxin (TTX). Evoked EPSCs were recorded at a holding potential of −70 mV in the presence of 10 µM gabazine. EPSCs were evoked with a 100-µs current pulse (10–100 µA) using a concentric bipolar electrode (FHC). The electrode was placed in the medial lemniscus fiber bundle (sensory input) or the internal capsule (CT input). The stimulus was delivered at 30-s intervals. Paired EPSCs were elicited by two electrical stimulations separated by 20–1,000 ms. EPSCs were confirmed as sensory input by an all-or-none response and short-term depression, whereas CT EPSCs were confirmed by a graded response to increasing stimulus intensity and short-term facilitation (32–34). One input (either sensory or CT) was stimulated per slice. Sensory and CT EPSCs were recorded from different cells. Holding commands were adjusted for a 10-mV liquid junction potential during the recordings. Series resistance and cell capacitance were monitored but were not compensated. Cells were excluded if either parameter changed >20% during the experiment.

Electrophysiology Data Analysis

Recordings were assigned numerical identifiers and analysis was performed blind to cell location. Current-clamp recordings were analyzed in Clampfit 11 (Molecular Devices) without additional filtering. Input resistance (Rin) was determined from the amplitude of voltage responses to 200-ms hyperpolarizing current injections, the time constant (τm) was determined by a mono-exponential fit of the voltage response, and cell capacitance was calculated by: Cm = τm/Rin. The Clampfit 11 threshold detection module was used to quantify the number of spikes, spike frequency, and latency to the first spike in response to depolarizing current injections or upon removal of hyperpolarizing current injections. Rheobase was defined as the smallest depolarizing current injection that elicited an action potential (AP). Values were averaged across three runs for all current injection experiments. The shape of single APs or low-frequency trains of APs were analyzed using the AP Search module in ClampFit 11. The baseline was manually set, and AP amplitude, half width, rise and decay time, afterhyperpolarization (AHP) amplitude and duration, and threshold were measured. Spike frequency adaptation was evaluated by measuring spike frequency across depolarizing current injections. Some VPM neurons had a prolonged interevent interval between the first two spikes following depolarization; therefore, the frequency of the first three spikes following current injection (fstart) was measured and compared with the frequency of the last two spikes (fend). The ratio of these frequencies (fstart/fend) is reported as the adaptation ratio. Two or three runs in the same cell were averaged.

For sEPSC/IPSC and mEPSC/IPSC analysis, recordings of 4–6 min were analyzed to determine interevent interval and amplitude using MiniAnalysis software (Synaptosoft). Data were digitally filtered at 1 kHz for analysis. Automated detection identified events with amplitude equal to or greater than 5 × RMS noise level, which was 8–12 pA. Automated detection accuracy was assessed and additional events ≥5 pA were detected manually. Amplitude and frequency values for each recording were averaged in 30-s bins. The reported values for each cell are the average across bins. Decay times were determined from ensemble averages of all sEPSC/IPSCs or mEPSC/IPSCs recorded from each cell. The 80–20% peak to baseline decay times of the ensemble averages were fitted using a double-exponential function:

| (1) |

where τFAST is the fast decay time constant, SLOW is the slow decay time constant, AmpFAST is the current amplitude of the fast decay component, and AmpSLOW is the current amplitude of the slow decay component. The weighted decay time constant (τW) was calculated by:

| (2) |

Evoked EPSC data were digitally filtered at 2 kHz for analysis. EPSC amplitude and decay time constants, determined using Eqs. 1 and 2, were measured from 3–5 sweeps in Clampfit and then averaged for each cell. The paired-pulse ratio was calculated by dividing the peak amplitude of the second EPSC by the peak amplitude of the first EPSC (EPSC2/EPSC1).

Biocytin Labeling and Dendrite Morphology

The cell location in the VPL or VPM was confirmed after electrophysiology recordings by biocytin labeling as previously described (29) or by images of the electrode location during the recording and then mapped onto a rodent brain atlas image (35). For biocytin labeling, brain slices were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in 1× PBS, pH 7.4, overnight at 4°C, washed in 1× PBS, and then stored at −20°C in cryoprotectant solution containing 0.87 M sucrose, 5.37 M ethylene glycol, and 10 g/L polyvinyl-pyrrolidone-40 in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. Slices were blocked with 10% normal donkey serum in 1× PBS with 0.25% Triton X-100 and then incubated with 1.0 μg/mL DyLight 594-conjugated streptavidin (Jackson Immunoresearch) in a blocking solution overnight at RT. Slices were mounted on a glass slide with a coverslip and DABCO mounting media. To assess cell location, ×10 images were acquired on an Olympus IX83 microscope with a Hamamatsu Orca Flash 4.0 camera, X-Cite Xylis LED, and TRITC filter sets using CellSens software.

Images for dendrite morphology were acquired as z-stacks with a 0.36-µm step size starting at the surface of the slice. Images were acquired using a Leica STELLARIS confocal microscope equipped with a Plan Apo ×40/1.25 NA glycerol immersion objective. Images were exported from Leica Application Suite software as 16-bit TIFF files with numerical identifiers. Image acquisition and analysis were performed by different experimenters ensuring analysis was blind to cell location. Dendrite reconstructions were generated using Vaa3D 3.2 automated tracing (36, 37) followed by manual corrections using NeuTube software (38). Dendrite morphology was analyzed using the SNT 4.2.1 plugin in ImageJ (RRID:SCR_003070) to quantify branch order analysis, Sholl intersections (8-µm interval), and total dendrite length (39). Z-stacks were also used to quantify the depth of the cell body from the slice surface to ensure there was no systematic difference between groups. The mean depth was similar between VPM neurons (29.3 µm, SD 16.5, n = 18) and VPL neurons (25.7 µm, SD 6.5, n = 18; Welch’s t test, mean difference = 3.5 µm, 95% CI [−5, 12], P = 0.405, t = 0.850, df = 22.10).

Statistical Analysis

A priori power analyses were performed in GPower 3.1 to estimate required sample sizes given appropriate statistical tests with α = 0.05, power (1 – β) = 0.8, and a moderate effect size or effect size based on pilot data. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (RRID:SCR_002798). All datasets were tested for normality by the Shapiro–Wilk test (P > 0.05). Equal variances between groups were not assumed as previous data showed unequal variances between VPL and VPM neuron populations for several metrics (29). Pairwise comparisons were performed with Welch’s t tests for normal datasets or Mann–Whitney U tests for non-normal datasets (40). Data for pairwise comparisons were graphed as estimation plots including the data points for each cell and the group mean (M) for normal datasets or median (Mdn) for non-normal datasets with the 95% confidence interval (CI) of the mean or median, respectively, on the left y-axis (41). The mean difference (MD) or Hodges-Lehmann median difference estimate (MDE) with 95% CI of the difference was plotted on the right y-axis (42). MD and MDE were calculated as MVPM − MVPL or MdnVPM – MdnVPL. A mixed-effects model was used to analyze the main effects for repeated-measures data, and two-factor grouped data without repeated measures were analyzed by two-way ANOVA for main and interaction effects. Multiple comparisons were performed with Šídák tests as appropriate. Correlations were analyzed by computing Pearson correlation coefficients, and the data are reported in the text as r with 95% CI and R2. The data were plotted and fit with a straight line using the least squares regression method. All data were reported in the text as the mean with standard deviation (SD) or median with 95% CI of the median as well as the MD or MDE with 95% CI of the difference (43). Negative MD or MDE values reflect a smaller value for VPM relative to VPL, and positive values reflect a larger value for VPM relative to VPL. All statistical inferences with exact P values are reported in the text or tables as well as the figures. The specific statistical tests with critical values and sample sizes are reported in the figure legends, tables, or table captions.

RESULTS

VPL Neurons Have Higher Depolarization-Induced Firing than VPM Neurons

VPL and VPM neurons have distinct roles in thalamic function, but whether differences in intrinsic physiology contribute to these distinct roles is unknown. To determine if cell physiology differed between VPL and VPM neurons, we first compared AP shape parameters measured from single APs or low-frequency spike trains elicited at or near the rheobase current (Fig. 1, B and C). There were no substantial differences for AP threshold, rise slope, decay slope, half-width, and amplitude between VPL and VPM neurons (Table 1; Fig. 1, D–G). Interestingly, VPM neurons had smaller AHP amplitude and shorter AHP duration than VPL neurons (Table 1; Fig. 1, E, H, and I). These data suggest that the rising and recovery phases of the AP are similar, but distinct mechanisms may regulate the AHP period in VPL and VPM neurons.

Table 1.

Action potential shape analysis of VPL and VPM neurons

| VPL | VPM | Mean Difference (VPM − VPL) [95% CI] | P Value | t Statistic, df | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Threshold, mV | −47.3, SD 4.1 | −47.4, SD 3.6 | −0.1 [−2.4, 2.2] | 0.943 | 0.071, 43.47 |

| Amplitude, mV | 59.2, SD 8.2 | 58.8, SD 10.1 | −0.3 [−5.8, 5.1] | 0.899 | 0.127, 42.13 |

| Half-width, ms | 0.83, SD 0.17 | 0.81, SD 0.17 | −0.02 [−0.12, 0.08] | 0.727 | 0.351, 43.99 |

| Rise slope, mV/ms | 136, SD 29 | 137, SD 43 | 1 [−20, 23] | 0.894 | 0.134, 38.86 |

| Decay slope, mV/ms | −70, SD 14 | −68, SD 21 | 2 [−9, 13] | 0.696 | 0.393, 37.50 |

| AHP amplitude, mV | 6.8, SD 1.9 | 4.0, SD 1.3 | −2.7 [−3.8, −1.8] | <0.001 | 5.706, 37.94 |

| AHP duration, ms | 28, SD 7 | 20, SD 4 | −8 [−11, −5] | <0.001 | 4.897, 37.04 |

Values are means with SD. Groups were compared by Welch’s t tests. VPL: n = 23 cells from 14 mice (7 females, 7 males). VPM: n = 23 cells from 13 mice (7 females, 6 males). AHP, afterhyperpolarization; VPL, ventral posterolateral; VPM, ventral posteromedial.

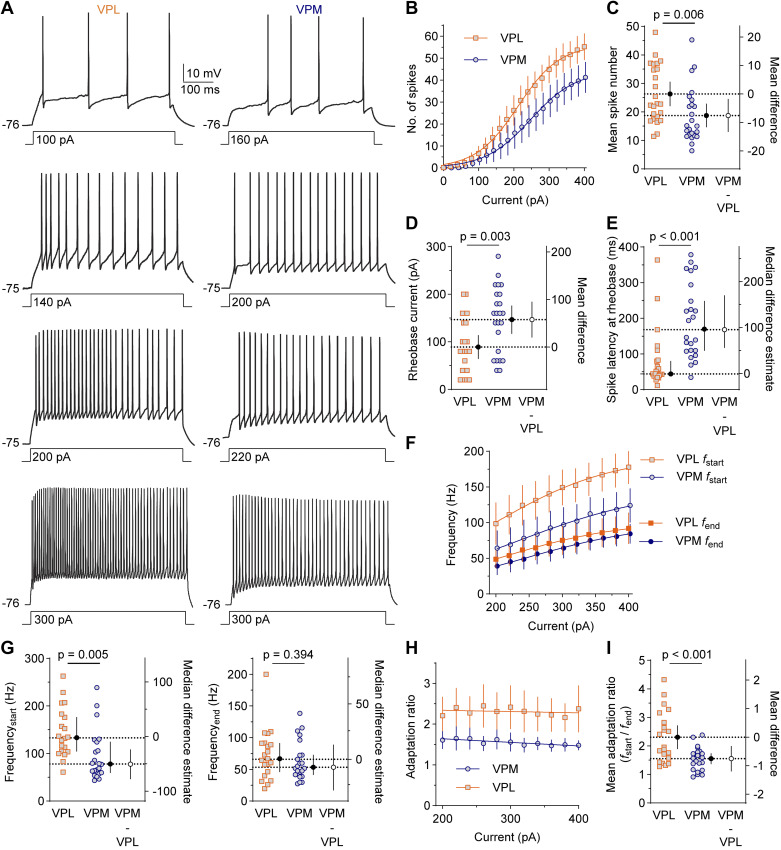

We next compared VPL and VPM neuron excitability by evaluating AP firing in response to a series of 500-ms depolarizing current injections (Fig. 2A). The number of spikes fired at each current injection was quantified, and a mixed-effects model was used to analyze the main effect of cell-type on the mean spike number across all current injections (Fig. 2B). VPM neurons fired an average of 18 spikes (SD 15), whereas VPL neurons fired an average of 26 spikes (SD 20; MD: −8 spikes, 95% CI [−15, −3], P = 0.006; Fig. 2C). The mean rheobase current for VPM neurons (147 pA, SD 69) was higher than VPL neurons (89 pA, SD 58; MD = 58 pA [20, 95], P = 0.003; Fig. 2D), indicating that more current was needed to elicit spikes in VPM neurons. The median spike latency at the rheobase current for VPM neurons was 170 ms (95% CI [110, 248]) and 44 ms (95% CI [42, 80]) in VPL neurons (MDE = 96 ms [57, 169], P < 0.001; Fig. 2E). These data suggest that VPM neurons exhibit lower excitability than VPL neurons.

Figure 2.

VPL neurons exhibit greater spike output and spike adaptation during depolarization. A: traces show four representative spike trains elicited by 500-ms depolarizing current injections. B–I: sample sizes are: VPL, n = 24 cells from 15 mice (8 females, 7 males); VPM, n = 24 cells from 15 mice (8 females, 7 males). Error bars are 95% CI. Estimation plots show data points for individual cells with group mean or median (black circle) plotted on the left axis and the mean or median difference (open circle) plotted on the right axis. B: mean spike number was plotted vs. current injection amplitude. The main effect of cell type across current injections was analyzed by a mixed-effects model [F(1, 46) = 8.446]. C: an estimation plot shows mean spike number averaged across current injections. D and E: estimation plots show mean rheobase current (Welch’s t test, t = 3.962, df = 31.90) and median spike latency at rheobase (Mann–Whitney U test, U = 87). F and G: mean spike frequency at the start (fstart) and end (fend) of the spike train and the mean spike adaptation ratio (H and I) were plotted and analyzed as described for B and C. Main effects: fstart, F(1, 41) = 8.835; fend, F(1, 41) = 0.741; adaptation ratio, F(1, 41) = 12.90. CI, confidence interval; VPL, ventral posterolateral; VPM, ventral posteromedial.

Spike adaptation is a reduction in AP frequency over a sustained period of depolarization. To test for differences in spike adaptation, we quantified the frequency of the initial three spikes (fstart) and the last two spikes (fend) across current injections between 200 and 400 pA (Fig. 2F), and then computed an adaptation ratio (fstart/fend). At the start of the spike train, the median frequency across current injections was 78 Hz (95% CI [60, 125]) in VPM neurons and 133 Hz (95% CI [105, 176]) in VPL neurons (MDE = −50 Hz [−77, −24], P = 0.005); whereas, the median frequency at the end of the spike train was 54 Hz (95% CI [42, 72]) in VPM neurons and 66 Hz (95% CI [46, 91]) in VPL neurons (MDE = −9 Hz [−30, 12], P = 0.394; Fig. 2G). The mean adaptation ratio across all current injections in VPM neurons (1.6, SD 0.5) was lower than VPL neurons (2.3, SD 0.9; MD = −0.7 [−1.1, −0.3], P < 0.001; Fig. 2, H and I). Together, these results are consistent with lower spiking upon depolarization in VPM neurons and greater spike adaptation in VPL neurons during sustained depolarization.

Sag Potential and Rebound Burst Latency Differ in VPL and VPM Neurons

Hyperpolarization-induced rebound bursting in VPL and VPM neurons contributes to thalamic oscillations and impacts sensory signal propagation to the cortex. Distinct nRT connectivity with VPL and VPM neurons indicates that the two thalamic regions might contribute distinctly to circuit-wide oscillations (10). Here, we directly compared how VPL and VPM neurons respond to hyperpolarizing current injections (Fig. 3A). Across all current injections, the overall mean spike number per burst was four spikes (SD 1) for VPM neurons and five spikes (SD 1) for VPL neurons (MD = −1 [−3, 1], P = 0.337; Fig. 3B). The mean sag potential amplitude during hyperpolarization was larger in VPM neurons (11.8 mV, SD 3.6) than VPL neurons (8.0 mV, SD 2.9, MD = 3.8 mV [1.8, 5.8], P < 0.001; Fig. 3, C and D). In addition, burst latency, the time between removal of the hyperpolarizing current and rebound burst firing, was shorter in VPM neurons (45 ms, SD 18) than in VPL neurons (70 ms, SD 27, MD = −25 ms [−39, −11], P < 0.001; Fig. 3, C and E). Greater sag potential could indicate that VPM neurons have larger hyperpolarization-activated depolarizing currents (Ih), which is consistent with a shorter burst latency. Indeed, sag potential amplitude was negatively correlated with burst latency for VPL neurons (r = −0.73, 95% CI [−0.88, −0.44], R2 = 0.53, P < 0.001) and VPM neurons (r = −0.76, 95% CI [−0.985, −0.48], R2 = 0.57, P < 0.001; Fig. 3F). To determine if sag potential was larger in VPM neurons as a result of greater membrane hyperpolarization, we compared the mean membrane hyperpolarization across all hyperpolarizing current injections and found no significant difference between VPM neurons (−35 mV, SD 13) and VPL neurons (−29 mV, SD 10; MD = −5.4 mV [−12, 0.9], P = 0.091; Fig. 3G). In addition, we compared sag potential amplitude across responses with similar membrane hyperpolarization (−30 ± 2 mV). The mean sag potential was significantly greater in VPM neurons (11.5 mV, SD 2.8) than in VPL neurons (8.6 mV, SD 2.6) even when controlling for membrane hyperpolarization (MD = 2.9 mV [1.3, 4.6], P < 0.001; Fig. 3H). Together, these results suggest VPL and VPM neurons have minimal differences in spiking within rebound bursts, but might respond differently to hyperpolarizing stimuli leading to faster recovery and burst generation following hyperpolarization in VPM neurons.

Figure 3.

VPM neurons have shorter burst latency and greater sag potential. A: traces show two representative bursts elicited by 500-ms hyperpolarizing current injections. Boxed insets are the recording periods above the gray lines. B–H: samples sizes are: VPL, n = 22 cells from 15 mice (7 females, 8 males); VPM, n = 22 cells from 15 mice (8 females, 7 males). Error bars are 95% CI. Estimation plots show data points for each cell with group mean (black circle) plotted on the left axis and the mean difference (open circle) plotted on the right axis. B: mean spike number per burst was plotted vs. current injection. The main effect of cell type across all current injections was analyzed by a mixed-effects model [F(1, 42) = 0.943] and illustrated as an estimation plot of the mean spike number averaged across current injections. C: recording periods above solid and dashed lines were expanded to illustrate burst latency (solid box) and sag potential (dashed box). D: sag potential was plotted and analyzed as described for B, main effect: F(1, 41) =14.59. E: an estimation plot shows burst latency for the minimal current injection to elicit a burst (Welch’s t test, t = 3.605, df = 37.24). F: sag potential was plotted vs. burst latency for each cell and fit by linear regression (Pearson’s coefficients: VPL, r = −0.73; VPM, r = −0.75). G: the mean change in membrane potential across all current injections was analyzed as in B [main effect: F(1, 43) = 2.994] and is shown in an estimation plot. H: an estimation plot shows sag potential of −30 mV responses (Welch’s t test, t = 3.586, df = 40.98). CI, confidence interval; VPL, ventral posterolateral; VPM, ventral posteromedial.

VPM Neurons Have Greater Membrane Capacitance and Dendritic Arborization

We next investigated if distinct resting membrane conductance or cell capacitance could potentially contribute to the observed differences in firing properties of VPM and VPL neurons. Intrinsic membrane properties were measured from voltage responses to small hyperpolarizing current injections. The mean RMP and input resistance (Rin) were similar for VPL and VPM neurons, whereas VPM neurons had larger cell capacitance (Cm) and a prolonged membrane time constant (τm) compared with VPL neurons (Table 2). These data suggest that membrane conductance at rest is similar, but that VPM neurons may have larger membrane surface area than VPL neurons.

Table 2.

Intrinsic membrane properties of VPL and VPM neurons

| VPL | VPM | Mean Difference (VPM − VPL) [95% CI] | P Value | t Statistic, df | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMP, mV | −74.7, SD 4.4 | −74.7, SD 4.5 | 0 [−2.5, 2.6] | 0.987 | 0.017, 47.2 |

| Rin, MΩ | 168, SD 57 | 173, SD 66 | 5.5 [−29, 40] | 0.752 | 0.318, 48.91 |

| Cm, pF | 148, SD 43 | 193, SD 55 | 46 [18, 73] | 0.002 | 3.294, 48.27 |

| τm, ms | 23.2, SD 7.3 | 30.9, SD 8.1 | 7.7 [3.4, 12] | <0.001 | 3.562, 48.98 |

Values are means with SD. Groups were compared by Welch’s t tests. VPL: n = 24 cells from 14 mice (7 females, 7 males). VPM: n = 27 cells from 16 mice (7 females, 9 males). Cm, cell capacitance; Rin, input resistance; RMP, resting membrane potential; VPL, ventral posterolateral; VPM, ventral posteromedial; τm, membrane time constant.

We further examined cell size by analyzing dendrite morphology of biocytin-filled VPL and VPM neurons (Fig. 4A). Sholl analysis indicated that VPM neurons had more complex dendritic arbors as the maximum number of Sholl intersections was significantly greater in VPM neurons (47, SD 14) than in VPL neurons (32, SD 16; MD = 15 [5, 25], P = 0.005, Fig. 4, B and C). The total dendrite length of VPM neurons (5.8 × 103 µm, SD 1.6 × 103) was also greater than VPL neurons (3.8 × 103 µm, SD 1.5 × 103; MD = 1.9 × 103 µm [0.9 × 103, 3.0 × 103], P < 0.001; Fig. 4D). Branch order analysis demonstrated that VPM neurons had greater overall mean dendrite number and dendrite length than VPL neurons across branch orders (Fig. 4, E and F). Specifically, VPM neurons had greater dendrite number at branch order five (VPM: 19, SD 10; VPL: 11, SD 7; MD = 8 [1, 17], P = 0.041) and dendrite length at branch order four (1.5 × 103 µm, SD 0.5 × 103) compared with VPL neurons (1.0 × 103 µm, SD 0.4 × 103; MD = 0.5 × 103 µm [1.0 × 103, 0.1 × 103], P = 0.047). Together, these data suggest that VPM neuron dendritic arbors have greater complexity and total size than VPL neurons, which could lead to slowed time course and propagation of dendritic potentials in VPM neurons.

Figure 4.

VPM neurons have larger dendritic arbors. A: dendrite reconstructions are shown for three representative biocytin-labeled VPL and VPM neurons. Scale bar: 100 µm. B–F: samples sizes are: VPL, n = 18 cells from 12 mice (5 males, 7 females); VPM, n = 18 cells, 12 mice (6 males, 6 females). Error bars are 95% CI. Estimation plots show data points for individual cells with group mean (black circle) plotted on the left axis and the mean difference (open circle) plotted on the right axis. B: the mean number of Sholl intersections was plotted vs. distance from the soma. Mixed-effects analysis determined the main effect of cell type, P = 0.049, F(1, 34) = 4.163, and interaction effect, P < 0.001, F(26, 883) = 5.436. Estimation plots show the maximum Sholl intersections (C) at shell radius 59 µm (Bonferroni t test, t = 3.012, df = 33.34) and total dendrite length (D; Welch’s t test, t = 3.703, df = 33.99). Dendrite number (E) and dendrite length (F) were plotted for each branch order and analyzed by two-way ANOVA. Main effects: E: P = 0.010, F(1, 34) = 7.401; F: P = 0.026, F(1, 34) = 5.446. Interaction: E: P = 0.001, F(7, 238) = 3.527; F: P = 0.017, F(7, 238) = 2.509. Šídák tests: E: *P = 0.041, t = 2.958, df = 29.78; F: *P = 0.043, t = 2.917, df = 32.68. CI, confidence interval; VPL, ventral posterolateral; VPM, ventral posteromedial.

VPL Neurons Have Greater Excitatory Synaptic Input than VPM Neurons

VPL and VPM neurons receive glutamatergic input from layer 6 CT neurons as well as anatomically distinct ascending sensory pathways, which could exhibit differences in synaptic transmission (see circuit diagram in Fig. 1A). We first compared overall excitatory synaptic input to VPL and VPM neurons by recording sEPSCs (Fig. 5, A–D). The mean sEPSC frequency in VPM neurons (3.3 Hz, SD 1.6) was lower than VPL neurons (6.6 Hz, SD 3.0; MD = −3.3 Hz [−5.0, −1.6], P < 0.001; Fig. 5E). The mean sEPSC amplitude in VPM neurons (11.9 pA, SD 2.2) was smaller than VPL neurons (19.3 pA, SD 5.2; MD = −7.4 pA [−10.2, −4.6], P < 0.001; Fig. 5F). Furthermore, the sEPSC decay time was prolonged in VPM neurons (6.6 ms, SD 1.8) compared with VPL neurons (5.1 ms, SD 1.2; MD = 1.5 ms [0.5, 2.7], P = 0.005; Fig. 5G). These findings suggest that VPM neurons have weaker excitatory synaptic input compared with VPL neurons, which could be due to differences in synapse function and number or differences in spontaneous activity of presynaptic neurons.

Figure 5.

The frequency and amplitude of sEPSCs and mEPSCs were lower in VPM neurons. A: cell locations for each sEPSC recording were mapped on a horizontal rat brain atlas image. Representative traces show sEPSC voltage-clamp recordings (B), ensemble averages of all sEPSCs from a single neuron (C), and traces from C normalized to the sEPSC peak (D). For all plots, error bars are 95% CI, data points for each cell with group mean or median (black circle) are plotted on the left axis, and mean or median difference (open circle) is plotted on the right axis. E–G: sample sizes are: VPL, n = 17 cells from 11 mice (5 females, 6 males); VPM, n = 19 cells from 12 mice (7 females, 5 males). Data were compared by Welch’s t tests: frequency (E; t = 4.043, df = 23.87), amplitude (F; t = 5.443, df = 21.24), and decay time (G; t = 3.033, df = 31.63). H: cell locations for each mEPSC recording were mapped on a horizontal rat brain atlas image. Representative traces show mEPSC voltage-clamp recordings (I), ensemble averages of all mEPSCs from a single neuron (J), and traces from C normalized to mEPSC peak (K). L–N: sample sizes are: VPL, n = 20 cells from 13 mice (7 females, 6 males); VPM, n = 20 cells from 12 mice (6 females, 6 males). Estimation plots show mESPC frequency (L; Mann–Whitney U test, U = 87), amplitude (M; Welch’s t test, t = 3.246, df = 34.25), and decay time (N; Welch’s t tests, t = 3.953, df = 30.43). CI, confidence interval; mEPSCs, miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents; sEPSCs, spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents; VPL, ventral posterolateral; VPM, ventral posteromedial.

We analyzed mEPSCs in the presence of TTX to eliminate spontaneous neuronal activity that may have contributed to observed differences in sEPSCs (Fig. 5, H–K). The frequency of mEPSCs was lower in VPM neurons (Mdn 1.9 Hz, 95% CI [1.5, 2.7]) compared with VPL neurons (Mdn 3.3 Hz, 95% CI [2.8, 4.0]), indicating that glutamatergic inputs to VPM neurons are fewer in number or have lower release probability than VPL neurons (MDE = −1.3 Hz [−2.0, −0.6], P = 0.002, Fig. 5L). The mean mEPSC amplitude was also smaller in VPM neurons (7.2 pA, SD 0.9) than in VPL neurons (8.3 pA, SD 1.2) suggesting that receptor expression or synaptic vesicle quantal content may differ between VPL and VPM synapses (MD = −1.1 pA [−1.7, −0.4], P = 0.003; Fig. 5M). The mean mEPSC decay time was prolonged in VPM neurons (8.0 ms, SD 2.2) compared with VPL neurons (6.0 ms, SD 1.4; MD = 2.0 ms [0.9, 3.1], P < 0.001; Fig. 5N), which could be due to differences in synapse function or dendritic filtering in the two cell populations.

VPM Neurons Have Weaker Ascending Sensory Input than VPL Neurons

The observed differences in mEPSCs and sEPSCs could result from differences in glutamatergic input at ascending sensory synapses or CT synapses. We investigated input-specific synapse function by comparing EPSCs evoked with electrical stimulation of sensory or CT axons (Fig. 6, A and B). We performed an input-output relationship with increasing stimulus intensity (Fig. 6, C and D) and compared the amplitude and decay time for EPSCs evoked at the lowest stimulus intensity in each cell. Sensory EPSC amplitude was smaller in VPM neurons (0.96 nA, SD 0.22) compared with VPL neurons (1.23 nA, SD 0.16; MD = −0.27 nA [−0.39, −0.16], P < 0.001), whereas CT EPSC amplitude was similar between VPM neurons (57 pA, SD 21) and VPL neurons (65 pA, SD 21; MD = −7 pA [−121, 107], P = 0.987; Fig. 6E). The sensory EPSC decay time constant was not significantly different in VPM neurons (6.1 ms, SD 1.0) and VPL neurons (5.0 ms, SD 1.0; MD = 1.0 ms [−0.3, 2.4], P = 0.144; Fig. 6F). However, the decay time constant for CT EPSCs was prolonged for VPM neurons (12.3 ms, SD 2.3) compared with VPL neurons (9.8 ms, SD 1.9; MD = 2.5 ms [1.2, 3.9], P < 0.001). These data suggest that VPM neurons have weaker sensory synapses and prolonged decay kinetics for CT EPSCs. To evaluate differences in release probability, we evoked pairs of EPSCs across a range of intervals. The mean paired-pulse ratio (EPSC2/EPSC1) across all intervals was similar for both sensory EPSCs (VPM: 0.69, SD 0.23; VPL: 0.65, SD 0.21; MD = 0.04 [−0.01, 0.10], P = 0.139; Fig. 6G) and CT EPSCs (VPM: 1.59, SD 0.77; VPL: 1.64, SD 0.68; MD = −0.05 [−0.20, 0.10], P = 0.512; Fig. 6H). These data indicate that glutamate release probability is similar between VPL and VPM neurons, which suggests that the lower mEPSC frequency observed in VPM neurons might be due to fewer excitatory synapses on VPM neurons relative to VPL neurons.

Figure 6.

Evoked EPSCs in VPM neurons have lower amplitude and prolonged decay time. Cell locations and representative traces are shown for recordings of electrically stimulated sensory (A) and CT EPSCs (B). Sample sizes for sensory EPSCs are: VPL, n = 16 cells from 10 mice (5 females, 5 males); VPM: n = 16 cells from 12 mice (7 females, 5 males). Sample sizes for CT EPSCs are: VPL, n = 16 cells from 10 mice (5 females, 5 males); VPM, n = 16 cells from 10 mice (5 females, 5 males). All error bars are 95% CI. C: sensory EPSC amplitude for each cell (gray) and the group medians were plotted vs. stimulus intensity. D: the mean CT EPSC amplitude was plotted vs. stimulus intensity. E: the amplitude of EPSCs evoked at the lowest stimulation level for each cell was plotted with group mean (black line) for sensory (left axis) and CT (right axis) inputs. Two-way ANOVA: main effect of cell type, F(1, 60) = 16.28, P < 0.001; interaction, F(1, 60) = 14.69, P < 0.001. Šídák tests: sensory, t = 5.563; CT, t = 0.143. F: EPSC decay times for each cell were plotted with group mean (black line). Two-way ANOVA: main effect of cell type, F(1, 60) = 19.32, P < 0.001; interaction, F(1, 60) = 3.344, P = 0.072. Šídák tests: sensory, t = 1.815; CT, t = 4.401. Representative pairs of evoked EPSCs are shown for sensory EPSCs (G; 100-ms interval) and CT EPSCs (H; 50-ms interval). The mean paired-pulse ratios were plotted vs. EPSC interval. Two-way ANOVA: main effect of cell type: sensory, F(1, 30) = 2.310, P = 0.139; CT, F(1, 30) = 0.441, P = 0.512. CI, confidence interval; CT, corticothalamic; EPSCs, excitatory postsynaptic currents; VPL, ventral posterolateral; VPM, ventral posteromedial.

VPM Neurons Have Higher Amplitude Spontaneous Inhibitory Input than VPL Neurons

VPL and VPM neurons may receive cell type-specific inhibitory input from nRT neurons (10). Therefore, we investigated possible differences in inhibitory synaptic input to VPL and VPM neurons by comparing the frequency, strength, and decay kinetics of sIPSCs (Fig. 7, A–D) and mIPSCs (Fig. 7, H–J). The mean sIPSC frequency was 4.9 Hz (SD 2.3) in VPM neurons and 6.9 Hz (SD 3.7) in VPL neurons (MD = 1.9 Hz [−3.9, 0.1], P = 0.058; Fig. 7E). The mean sIPSC amplitude was greater in VPM neurons (29.5 pA, SD 3.6) compared with VPL neurons (25.9 pA, SD 3.7; MD = 3.6 pA [1.3, 5.9], P = 0.003; Fig. 7F). VPM neuron mean sIPSC decay time (14.2 ms, SD 2.4) was similar to VPL neurons (14.3 ms, SD 2.2; MD = −0.1 ms [−1.6, 1.3], P = 0.852; Fig. 7G). These data suggest that VPM neurons received stronger inhibitory input compared with VPL neurons. A comparison of mIPSCs yielded no significant differences in frequency (VPM: 4.2 Hz, SD 1.9; VPL: 4.5 Hz, SD 1.7; MD = −0.3 [−1.4, 0.9], P = 0.651; Fig. 7K), amplitude (VPM: 23 pA, SD 5; VPL: 24 pA, SD 4; MD = −1.0 [−4, 2], P = 0.609; Fig. 7L), or decay time (VPM: 14.3 ms, SD 3.3; VPL: 13.5 ms, SD 3.4; MD = 0.8 [−1.2, 2.9], P = 0.423; Fig. 7M). These data suggest that the observed increase in sIPSC amplitude may result from higher spontaneous activity of nRT neurons projecting to VPM neurons as opposed to differences in inhibitory synapse function or number.

Figure 7.

VPM neurons have higher sIPSC amplitude than VPL neurons. Cell locations for each sIPSC (A) and mIPSC (H) recording were mapped on a horizontal rat brain atlas image. Representative traces show voltage-clamp recordings of sIPSCs (B) and mIPSCs (I) as well as ensemble averages of all sIPSCs (C) and mIPSCs (J) from one neuron. D: traces from C were normalized to sIPSC peak. For all plots, error bars are 95% CI, data points for each cell with group mean (black circle) are plotted on the left axis, mean difference (open circle) is plotted on the right axis, and data were compared by Welch’s t tests. E–G: sample sizes are: VPL, n = 21 cells from 14 mice (8 females, 6 males); VPM, n = 20 cells from 13 mice (7 females, 6 males). Estimation plots show sIPSC frequency (E; t = 1.970, df = 31.76), amplitude (F; t = 3.155, df = 38.85), and decay time (G; t = 0.188, df = 38.99). K–M: sample sizes are: VPL, n = 22 from 15 mice (7 females, 8 males); VPM, n = 22 cells from 16 mice (7 females, 9 males). Estimation plots show mIPSC frequency (K; t = 0.456, df = 41.42), amplitude (L; t = 0.156, df = 41.55), and decay time (M; t = 0.810, df = 41.95). CI, confidence interval; mIPSCs, miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents; sIPSCs, spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic current; VPL, ventral posterolateral; VPM, ventral posteromedial.

DISCUSSION

VPL and VPM thalamus comprise two neighboring thalamocortical neuron populations that are part of parallel pathways carrying somatosensory information from the body and head, respectively. Here, we revealed physiological and morphological differences between VPL and VPM neurons that could influence how these distinct sensory signals are processed by the thalamus. Specifically, analysis of synaptic transmission suggests that VPM neurons receive weaker excitatory synaptic drive and stronger inhibitory input compared with VPL neurons. Tonic and burst firing properties also differed between VPL and VPM neurons, which could contribute to their distinct physiological roles in sensory processing as well as thalamocortical oscillations. This work indicates that neurons in the ventrobasal (VB) thalamus are more heterogeneous than previously recognized, thus highlighting the importance of applying cell type- or nucleus-specific methodologies when investigating somatosensory thalamus circuitry.

Our observations suggest that VPL neurons are more excitable in response to depolarizing stimuli compared with VPM neurons. VPM neurons had greater cell capacitance and a prolonged membrane time constant, which could slow their response to depolarization contributing to less spike firing and prolonged latency to firing. The rising phase of the AP appeared similar, but voltage-gated channel expression and function have not been compared between these cell populations; therefore, we cannot rule out contributions of distinct voltage-gated sodium or calcium channels to the observed differences in depolarization-induced spiking. Indeed, haploinsufficiency of NaV1.1 in a Dravet syndrome mouse model led to opposing changes in VPL and VPM cellular excitability suggesting that voltage-gated sodium channels might have differential expression or function in the VPL and VPM thalamus (29).

A unique activity-dependent mechanism may regulate VPL firing during sustained depolarization as VPL neurons exhibited greater spike frequency adaptation. Spike frequency adaptation in VB neurons has been proposed as a self-inhibiting mechanism, limiting the propagation of information during excessive activation (11, 12, 31). Differences in spike frequency adaptation suggest that the thalamus may differentially regulate propagation of somatosensory information from the body and head. Consistent with our results, two neuron populations with distinct spike adaptation properties were previously discovered in the VB thalamus (20); however, it is not clear how these two cell populations were distributed within the VB thalamus. Spike frequency adaptation might be mediated by anoctamin-2 (ANO2), a calcium-activated chloride channel (11, 44). However, the expression and function of ANO2, or other channels implicated in spike frequency adaptation such as calcium-activated potassium channels (e.g., SK channels), have not been investigated in VPL and VPM neurons independently. ANO2 and SK channels also contribute to the AHP period in VB neurons (11, 44). Interestingly, we observed a larger AHP in VPL neurons relative to VPM neurons, which further suggests that differences in calcium-activated currents could contribute to the distinct physiology of the two neuron populations.

Upon recovery from robust hyperpolarizing input from the nRT, VPL and VPM neurons fire low-threshold calcium spikes mediated by T-type calcium channels and high-frequency bursts. Recurrent rebound bursts between nRT and VB neurons generate oscillations, which underlie physiological processes such as sleep spindles. The nRT-VPM loop may be more important in intrathalamic oscillation generation and maintenance than the nRT-VPL loop due to stronger coupling between PV-expressing nRT neurons and VPM neurons (10). However, VPM neurons could also have distinct intrinsic burst firing properties as we observed a shorter latency to burst firing upon removal of hyperpolarization and a greater sag potential in VPM neurons. HCN channels mediate a hyperpolarization-activated cation current (Ih) that contributes to burst firing and is responsible for sag potential (9). Consistent with our results, sag potential amplitude has been shown to negatively correlate with burst latency, but has no correlation to the number of spikes per burst (45). Thus, it is possible that differences in Ih contribute to distinct rhythmic activity observed in VPL and VPM neurons. HCN and voltage-gated calcium channel function have been evaluated in nRT and VB neurons (13, 14, 17, 19), but not in VPL and VPM neurons specifically. Elucidating the specific mechanisms creating distinct tonic and burst firing properties will require a direct comparison of ion channel expression and function in the two cell populations.

Distinct synaptic connectivity or function may also contribute to different physiological roles of VPL and VPM neurons. Ascending somatosensory synapses are formed by large axon terminals on proximal dendrites and generate high-amplitude, fast-decaying synaptic potentials, whereas CT synapses are formed by small axon terminals on more distal dendrites and generate low-amplitude, slower-decaying synaptic potentials (32–34, 46–48). We present evidence that VPM neurons receive less excitatory synaptic input due, in part, to weaker sensory synapses. Furthermore, VPM neurons exhibited lower mEPSC frequency, but similar glutamate release probabilities at both sensory and CT synapses, indicating that VPM neurons may receive fewer excitatory synaptic inputs than VPL neurons. We also observed prolonged decay kinetics of VPM EPSCs at CT synapses, which could be due to differences in synapse function or dendritic filtering. Indeed, VPM neurons had larger cell capacitance, a prolonged membrane time constant, and more complex dendritic arbors, which would be expected to reduce the amplitude and prolong decay times of synaptic currents recorded in the soma. However, we detected smaller amplitude sensory EPSCs originating on proximal dendrites, but not CT EPSCs originating on distal dendrites. Thus, greater filtering cannot fully explain the differences in excitatory input. Notably, a previous study found no significant differences in the dendritic arbors of VPL and VPM neurons in P14–P18 Wistar Hans rats (20); these conflicting results could be due to a difference in age and species as our study used P25–P32 C57Bl/6J mice. Future work analyzing dendritic potentials and synapse innervation will be necessary to clarify the mechanisms resulting in weaker excitatory synaptic input to VPM neurons.

GABAergic neurons in the nRT provide the major inhibitory input to VPL and VPM neurons, but the strength and identity of nRT inputs may differ between the two cell populations. We detected larger amplitude spontaneous IPSCs in VPM neurons, which likely resulted from higher spontaneous activity of VPM-projecting nRT neurons. Consistent with this, PV-expressing nRT neurons have greater excitability and stronger burst-firing properties than SOM-expressing nRT neurons, and VPM neuron connectivity with PV-expressing nRT neurons may be greater than that of VPL neurons (10). In addition, SOM-positive neurons may innervate VPL neurons, but not VPM neurons (10); however, another report suggested that SOM-positive nRT neurons only project to the POm region of the somatosensory thalamus bypassing both VPL and VPM neurons (49). Notably, presynaptic GABAB receptors regulate inhibitory and excitatory synaptic transmission onto VB neurons as well as nRT neuron bursting and thalamic oscillations (15, 50, 51). GABAB receptor function, to our knowledge, has not been compared in VPL and VPM neurons but will be important to consider as a possible mechanism underlying the distinct physiology in VPL and VPM thalamus.

The observed differences in synaptic function, depolarization-induced firing, and rebound bursting indicate that VPL and VPM thalamus may process somatosensory information differently. The frequency of spike trains encodes critical information that is propagated from the VPL and VPM to the somatosensory cortex. Specifically, VPL neurons have been shown to increase their spike frequency in response to increasingly noxious stimuli, but not innocuous sensory input (52, 53). Thus, it is possible that VPL and VPM neurons have different sensitivities to noxious stimuli. Greater spike frequency adaptation may indicate that VPL neurons are more likely to slow their response to repeated incoming sensory signals than their VPM counterparts. VPL and VPM neurons could also receive ascending input with distinct patterns or strengths that shape how they process and relay sensory signals. A limitation of this study is that we cannot interpret how collective changes in excitability and synaptic input impact thalamocortical neuron output.

In conclusion, the data presented here as well as existing knowledge of somatosensory CT circuit connectivity suggest that VPL and VPM thalamus are part of functionally distinct microcircuits within the broader somatosensory CT circuit. Understanding the functional differences between these two parallel pathways is not only important for better understanding of a healthy circuit, but may also have implications for diseases including epilepsy, chronic pain, and sleep disorders. Investigations into pathological function within the somatosensory CT circuit have historically treated the VB thalamus as a uniform nucleus, potentially obscuring cell type-specific effects and therapeutic opportunities in the VPL and VPM thalamus. Further investigation is required to uncover the molecular mechanisms through which these two microcircuits process sensory signals and generate circuit-wide rhythmogenesis as well as how they may be uniquely suited for therapeutic targeting.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health R01NS105804 and R21NS128635 (to S.A.S.), CURE Epilepsy (to S.A.S.), Dravet Syndrome Foundation (to S.A.S.), Brain Research Foundation BRFSG-2021-10 (to S.A.S.), and Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic: Program LT - INTER-EXCELLENCE, LTAUSA19122 (to A.B.).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.S., M.L., and S.A.S. conceived and designed research; C.S., M.L., M.S., R.K., Y.C., G.A.V., M.A.T., E.T., and S.A.S. performed experiments; C.S., M.L., M.S., G.A.V., and S.A.S. analyzed data; C.S., M.L., A.B., and S.A.S. interpreted results of experiments; C.S. and S.A.S. prepared figures; C.S. and S.A.S. drafted manuscript; C.S., M.L., M.S., R.K., Y.C., M.A.T., E.T., A.B., and S.A.S. edited and revised manuscript; C.S., M.L., M.S., R.K., Y.C., G.A.V., M.A.T., E.T., A.B., and S.A.S. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Present addresses: M. Ladislav, Institute of Experimental Medicine of the Czech Academy of Sciences, Prague, Czech Republic; M. A. Topolski, Dept. of Biological Sciences, Lehigh University, Bethlehem, PA, USA.

REFERENCES

- 1. Beenhakker MP, Huguenard JR. Neurons that fire together also conspire together: is normal sleep circuitry hijacked to generate epilepsy? Neuron 62: 612–632, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wolff M, Vann SD. The cognitive thalamus as a gateway to mental representations. J Neurosci 39: 3–14, 2019. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0479-18.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fanselow EE, Nicolelis MA. Behavioral modulation of tactile responses in the rat somatosensory system. J Neurosci 19: 7603–7616, 1999. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-17-07603.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fernandez LMJ, Luthi A. Sleep spindles: mechanisms and functions. Physiol Rev 100: 805–868, 2020. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00042.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brecht M, Sakmann B. Whisker maps of neuronal subclasses of the rat ventral posterior medial thalamus, identified by whole-cell voltage recording and morphological reconstruction. J Physiol 538: 495–515, 2002. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.012334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhang ZW, Deschenes M. Intracortical axonal projections of lamina VI cells of the primary somatosensory cortex in the rat: a single-cell labeling study. J Neurosci 17: 6365–6379, 1997. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-16-06365.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sherman SM. Tonic and burst firing: dual modes of thalamocortical relay. Trends Neurosci 24: 122–126, 2001. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01714-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Steriade M, Llinas RR. The functional states of the thalamus and the associated neuronal interplay. Physiol Rev 68: 649–742, 1988. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1988.68.3.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Llinas RR, Steriade M. Bursting of thalamic neurons and states of vigilance. J Neurophysiol 95: 3297–3308, 2006. doi: 10.1152/jn.00166.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Clemente Perez A, Ritter-Makinson S, Higashikubo B, Brovarney S, Cho FS, Urry A, Holden SS, Wimer M, Dávid C, Fenno LE, Acsády L, Deisseroth K, Paz JT. Distinct thalamic reticular cell types differentially modulate normal and pathological cortical rhythms. Cell Rep 19: 2130–2142, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ha GE, Lee J, Kwak H, Song K, Kwon J, Jung S-Y, Hong J, Chang G-E, Hwang EM, Shin H-S, Lee CJ, Cheong E. The Ca2+-activated chloride channel anoctamin-2 mediates spike-frequency adaptation and regulates sensory transmission in thalamocortical neurons. Nat Commun 7: 13791, 2016. [Erratum in Nat Commun 12: 6503, 2021]. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cheong E, Kim C, Choi BJ, Sun M, Shin H-S. Thalamic ryanodine receptors are involved in controlling the tonic firing of thalamocortical neurons and inflammatory pain signal processing. J Neurosci 31: 1213–1218, 2011. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3203-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Abbas SY, Ying S-W, Goldstein PA. Compartmental distribution of hyperpoarization-activated cyclic-nucleotide-gated channel 2 and hyperpolarization-activated-activated cyclic-nucleotide-gated channel 4 in thalamic reticular and thalamocortical relay neurons. Neuroscience 141: 1811–1825, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Astori S, Wimmer RD, Prosser HM, Corti C, Corsi M, Liaudet N, Volterra A, Franken P, Adelman JP, Lüthi A. The Cav3.3 calcium channel is the major sleep spindle pacemaker in thalamus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 13823–13828, 2011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105115108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Huguenard J, Prince D. Intrathalamic rhythmicity studied in vitro: nominal T-current modulation causes robust antioscillatory effects. J Neurosci 14: 5485–5502, 1994. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-09-05485.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jacobsen RB, Ulrich D, Huguenard JR. GABA(B) and NMDA receptors contribute to spindle-like oscillations in rat thalamus in vitro. J Neurophysiol 86: 1365–1375, 2001. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.3.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Talley EM, Cribbs LL, Lee JH, Daud A, Perez-Reyes E, Bayliss DA. Differential distribution of three members of a gene family encoding low voltage-activated (T-type) calcium currents. J Neurosci 19: 1895–1911, 1999. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-06-01895.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Warren RA, Agmon A, Jones EG. Oscillatory synaptic interactions between ventroposterior and reticular neurons in mouse thalamus in vitro. J Neurophysiol 72: 1993–2003, 1994. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.4.1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zobeiri M, Chaudhary R, Blaich A, Rottmann M, Herrmann S, Meuth P, Bista P, Kanyshkova T, Lüttjohann A, Narayanan V, Hundehege P, Meuth SG, Romanelli MN, Urbano FJ, Pape H-C, Budde T, Ludwig A. The hyperpolarization-activated HCN4 channel is important for proper maintenance of oscillatory activity in the thalamocortical system. Cereb Cortex 29: 2291–2304, 2019. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhz047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Iavarone E, Yi J, Shi Y, Zandt BJ, O'Reilly C, Van Geit W, Rossert C, Markram H, Hill SL. Experimentally-constrained biophysical models of tonic and burst firing modes in thalamocortical neurons. PLoS Comput Biol 15: e1006753, 2019. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hazra A, Corbett BF, You JC, Aschmies S, Zhao L, Li K, Lepore AC, Marsh ED, Chin J. Corticothalamic network dysfunction and behavioral deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 44: 96–107, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Paz JT, Bryant AS, Peng K, Fenno L, Yizhar O, Frankel WN, Deisseroth K, Huguenard JR. A new mode of corticothalamic transmission revealed in the Gria4−/− model of absence epilepsy. Nat Neurosci 14: 1167–1173, 2011. doi: 10.1038/nn.2896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hedrich UBS, Liautard C, Kirschenbaum D, Pofahl M, Lavigne J, Liu Y, Theiss S, Slotta J, Escayg A, Dihne M, Beck H, Mantegazza M, Lerche H. Impaired action potential initiation in GABAergic interneurons caused hyperexcitable networks in an epileptic mouse model carrying a human Nav1.1 mutation. J Neurosci 34: 14874–14889, 2014. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0721-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ritter-Makinson S, Clemente-Perez A, Higashikubo B, Cho F, Holden S, Bennett E, Chkaidze A, Rooda OE, Cornet MC, Hoebeek F, Yamakawa K, Cilio MR, Delord B, Paz J. Augmented reticular thalamic bursting and seizures in Scn1a-Dravet syndrome. Cell Rep 26: 54–64.e6, 2019. [Erratum in Cell Rep 26: 1071, 2019]. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hall KD, Lifshitz J. Diffuse traumatic brain injury initially attenuates and later expands activation of the rat somatosensory whisker circuit concomitant with neuroplastic responses. Brain Res 1323: 161–173, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.01.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Paz JT, Davidson TJ, Frechette ES, Delord B, Parada I, Peng K, Deisseroth K, Huguenard JR. Closed-loop optogenetic control of thalamus as a new tool to interrupt seizures after cortical injury. Nat Neurosci 16: 64–70, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nn.3269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Princivalle AP, Richards DA, Duncan JS, Spreafico R, Bowery NG. Modification of GABAB1 and GABAB2 receptor subunits in the somatosensory cerebral cortex and thalamus of rats with absence seizures (GAERS). Epilepsy Res 55: 39–51, 2003. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(03)00090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. David F, Carcak N, Furdan S, Onat F, Gould T, Meszaros A, Giovanni GD, Hernandez VM, Chan CS, Lorincz ML, Crunelli V. Suppression of hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated channel function in thalamocortical neurons prevents genetically determined and pharmacologically induced absence seizures. J Neurosci 38: 6615–6627, 2018. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0896-17.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Studtmann C, Ladislav M, Topolski MA, Safari M, Swanger SA. Na(V)1.1 haploinsufficiency impairs glutamatergic and GABAergic neuron function in the thalamus. Neurobiol Dis 167: 105672, 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2022.105672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chiaia NL, Rhoades RW, Fish SE, Killackey HP. Thalamic processing of vibrissal information in the rat: II. Morphological and functional properties of medial ventral posterior nucleus and posterior nucleus neurons. J Comp Neurol 314: 217–236, 1991. doi: 10.1002/cne.903140203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Landisman CE, Connors BW. VPM and PoM nuclei of the rat somatosensory thalamus: intrinsic neuronal properties and corticothalamic feedback. Cereb Cortex 17: 2853–2865, 2007. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Miyata M. Distinct properties of corticothalamic and primary sensory synapses to thalamic neurons. Neurosci Res 59: 377–382, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Castro-Alamancos MA. Properties of primary sensory (lemniscal) synapses in the ventrobasal thalamus and the relay of high-frequency sensory inputs. J Neurophysiol 87: 946–953, 2002. doi: 10.1152/jn.00426.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hsu C-L, Yang H-W, Yen C-T, Min M-Y. Comparison of synaptic transmission and plasticity between sensory and cortical synapses on relay neurons in the ventrobasal nucleus of the rat thalamus. J Physiol 588: 4347–4363, 2010. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.192864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gaidica M. mattgaidica/RatBrainAtlasAPI (Online).https://github.com/mattgaidica/RatBrainAtlasAPI) [2022 Dec 2].

- 36. Peng H, Ruan Z, Long F, Simpson JH, Myers EW. V3D enables real-time 3D visualization and quantitative analysis of large-scale biological image data sets. Nat Biotechnol 28: 348–353, 2010. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Peng H, Bria A, Zhou Z, Iannello G, Long F. Extensible visualization and analysis for multidimensional images using Vaa3D. Nat Protoc 9: 193–208, 2014. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhao T, Olbris DJ, Yu Y, Plaza SM. NeuTu: software for collaborative, large-scale, segmentation-based connectome reconstruction. Front Neural Circuits 12: 101, 2018. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2018.00101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Arshadi C, Gunther U, Eddison M, Harrington KIS, Ferreira TA. SNT: a unifying toolbox for quantification of neuronal anatomy. Nat Methods 18: 374–377, 2021. doi: 10.1038/s41592-021-01105-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ruxton GD. The unequal variance t-test is an underused alternative to Student’s t-test and the Mann–Whitney U test. Behavioral Ecology 17: 688–690, 2006. doi: 10.1093/beheco/ark016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Calin-Jageman RJ, Cumming G. Estimation for better inference in neuroscience. eNeuro 6: ENEURO.0205-19.2019, 2019. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0205-19.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hodges JL, Lehmann EL. Estimates of location based on rank tests. Ann Math Statist 34: 598–611, 1963. doi: 10.1214/aoms/1177704172. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Curran-Everett D, Benos DJ. Guidelines for reporting statistics in journals published by the American Physiological Society. J Neurophysiol 92: 669–671, 2004. doi: 10.1152/jn.00534.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ha GE, Cheong E. Spike frequency adaptation in neurons of the central nervous system. Exp Neurobiol 26: 179–185, 2017. doi: 10.5607/en.2017.26.4.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Desai NV, Varela C. Distinct burst properties contribute to the functional diversity of thalamic nuclei. J Comp Neurol 529: 3726–3750, 2021. [Erratum in J Comp Neurol 530: 1126, 2022]. doi: 10.1002/cne.25141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Spacek J, Lieberman AR. Ultrastructure and three-dimensional organization of synaptic glomeruli in rat somatosensory thalamus. J Anat 117: 487–516, 1974. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Liu XB, Honda CN, Jones EG. Distribution of four types of synapse on physiologically identified relay neurons in the ventral posterior thalamic nucleus of the cat. J Comp Neurol 352: 69–91, 1995. doi: 10.1002/cne.903520106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Williams MN, Zahm DS, Jacquin MF. Differential foci and synaptic organization of the principal and spinal trigeminal projections to the thalamus in the rat. Eur J Neurosci 6: 429–453, 1994. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb00286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Martinez-Garcia RI, Voelcker B, Zaltsman JB, Patrick SL, Stevens TR, Connors BW, Cruikshank SJ. Two dynamically distinct circuits drive inhibition in the sensory thalamus. Nature 583: 813–818, 2020. [Erratum in Nature 585: E13, 2020]. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2512-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ulrich D, Besseyrias V, Bettler B. Functional mapping of GABA(B)-receptor subtypes in the thalamus. J Neurophysiol 98: 3791–3795, 2007. doi: 10.1152/jn.00756.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Huguenard JR, Prince DA. Clonazepam suppresses GABAB-mediated inhibition in thalamic relay neurons through effects in nucleus reticularis. J Neurophysiol 71: 2576–2581, 1994. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.6.2576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kenshalo DR Jr, Giesler GJ Jr, Leonard RB, Willis WD. Responses of neurons in primate ventral posterior lateral nucleus to noxious stimuli. J Neurophysiol 43: 1594–1614, 1980. doi: 10.1152/jn.1980.43.6.1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Martin WJ, Hohmann AG, Walker JM. Suppression of noxious stimulus-evoked activity in the ventral posterolateral nucleus of the thalamus by a cannabinoid agonist: correlation between electrophysiological and antinociceptive effects. J Neurosci 16: 6601–6611, 1996. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-20-06601.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.