By virtue of the inherent anharmonic lattice dynamics, the volume of most solids expands upon heating. It is unconventional to find solids with negative thermal expansion (NTE), i.e., solids in which the distances between atoms decrease with increasing temperature.1–3 NTE materials have crucial technological applications in the control of thermal expansion. In 1996, isotropic NTE was discovered in ZrW2O8.1 In the past two decades, NTE has been found in various types of materials, such as oxides,4–7 alloys,8–13 nitrides,14,15 fluorides,16–18 and cyanides.19–22 In essence, the thermal expansion of a solid is affected by a complex interplay between the electrons, phonons, and lattice.2 The NTE phenomenon originates from diverse factors such as an open-framework,17,19 the size effect,23 charge transfer,5,6 magnetism,12–14,24 ferroelectricity,7 and superconductivity.25,26 Obviously, most of the NTE solids are inorganics, which have relatively strong chemical bonds.

It is known that solids with weak bonds exhibit a strong positive thermal expansion (PTE).27 For example, due to their weak metallic bonds, metals based compounds generally have a strong PTE, e.g., Al , Cu , and Fe .28 To meet the requirement for a low coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE), metal matrix composites (MMCs) are often fabricated by adding fillers with low or negative thermal expansion,29 such as Cu/ZrW2O8 composites,30 Al(Si)/Diamond,31 Al/stainless-invar,32 and Al/SiC.33 It is well-known that metals based compounds are normally benefitted by advantages such as high mechanical strength and good electrical and thermal conductivities. Therefore, it is imperative that NTE metals based compounds be found. For example, the Invar alloy Fe0.65Ni0.35, which was found in 1897, has been a popular topic of fundamental studies and practical applications over the last century. Because of this discovery, Swiss scientist C. É. Guillaume won a Nobel Prize in Physics in 1920.34 However, rare NTE metals based compounds have been found, such as Invar alloys,8 R2Fe17 (R = rare earth elements),9 (Hf,Nb)Fe2,10 MnCoGe-based compounds,11 La(Fe,Si,Co)13,12 and Tb-(Co,Fe)2.13 Note that all of these NTE metals based compounds are ferromagnetic.

Here, we report an intriguing NTE in the noncollinear antiferromagnetic intermetallic compounds of Mn3Ge. For a better understanding on the NTE mechanism of Mn3Ge, the isostructural compound of Mn3Sn showing PTE has also been studied for comparison. Their complicated triangular antiferromagnetic (AFM) structure and NTE mechanism are revealed via a combined analysis of the temperature dependence of neutron powder diffraction (NPD), synchrotron X-ray diffraction (SXRD) and macroscopic magnetic measurements. The direct link between the NTE behavior and the magnetic structure, which is correlated to the magnetovolume effect (MVE), is demonstrated. Particularly, the present NTE Mn3Ge exhibits excellent mechanical properties and good thermal and electron conductivity behaviors.

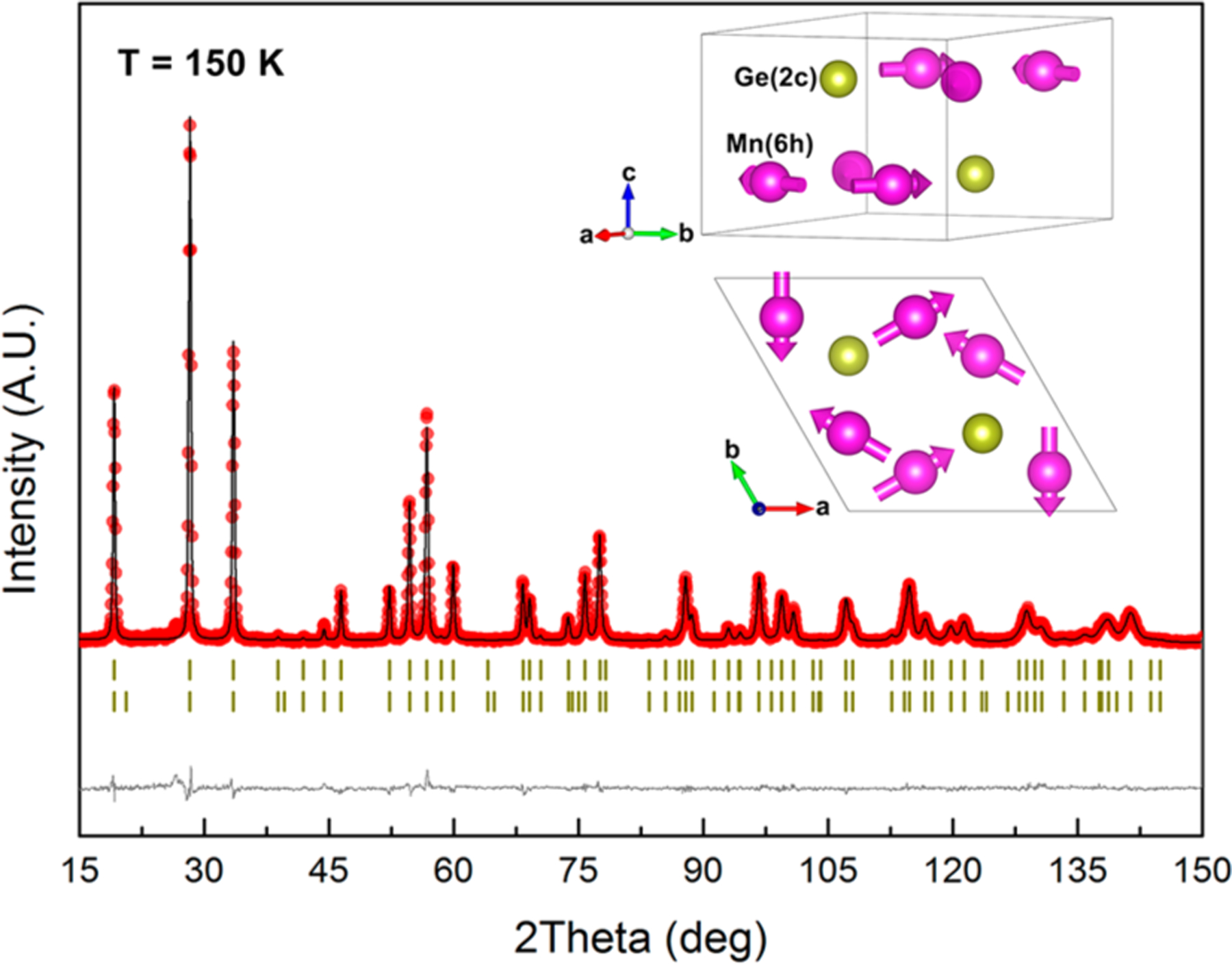

A series of single-phase samples were prepared via arc melting. The crystal structure was identified via high-intensity SXRD (Figure S1a). To determine the precise magnetic and crystal structure of both Mn3Ge and Mn3Sn, the temperature dependence of NPD has been carried. Mn3Ge remains in a single phase with a hexagonal structure (space group: P63/mmc) over the whole temperature range. Mn and Ge atoms occupy Wyckoff sites 6h and , respectively (inset of Figure 1). By comparing the NPD patterns at typical low and high temperatures (150 and 500 K, respectively), the magnetic structure makes only an additional intensity contribution to the nuclear peaks, and no additional peaks can be observed. Therefore, the propagation vector of the Mn3Ge magnetic structure is (Figure S2). Its crystal structure consists of alternating layers of manganese triangles, stacked parallel to the c axis. Because of the geometrical frustration, three neighboring spins cannot be pairwise antialigned on a triangular lattice.35 Therefore, only the triangular antiferromagnetic structures are compatible. Some of the possible magnetic structural models allowed by the symmetry of the P63/mmc structure and its subgroups are listed in Figure S3. Among these AFM spin configurations, the structural model of Figure S 3f gives the best refinement. Figure 1 presents the magnetic structure refinements of the NPD pattern for Mn3Ge. The Mn moments of inverse triangular antiferromagnetic order are along the [110] direction, and the spins rotate 120° counterclockwise in the plane (the inset of Figure 1). It needs to note that the magnetic structure of Mn3Ge is similar to the previous studies.36,37

Figure 1.

Magnetic structure of NTE Mn3Ge, determined via neutron powder diffraction. The space group is P63/mmc. The observed (red circles), calculated (black line), and differential (gray line at bottom of figure) patterns are shown for the full-profile refinement of Mn3Ge at . The vertical ticks mark the calculated positions of nuclear and magnetic reflections. The inset shows the magnetic and crystal structures of Mn3Ge.

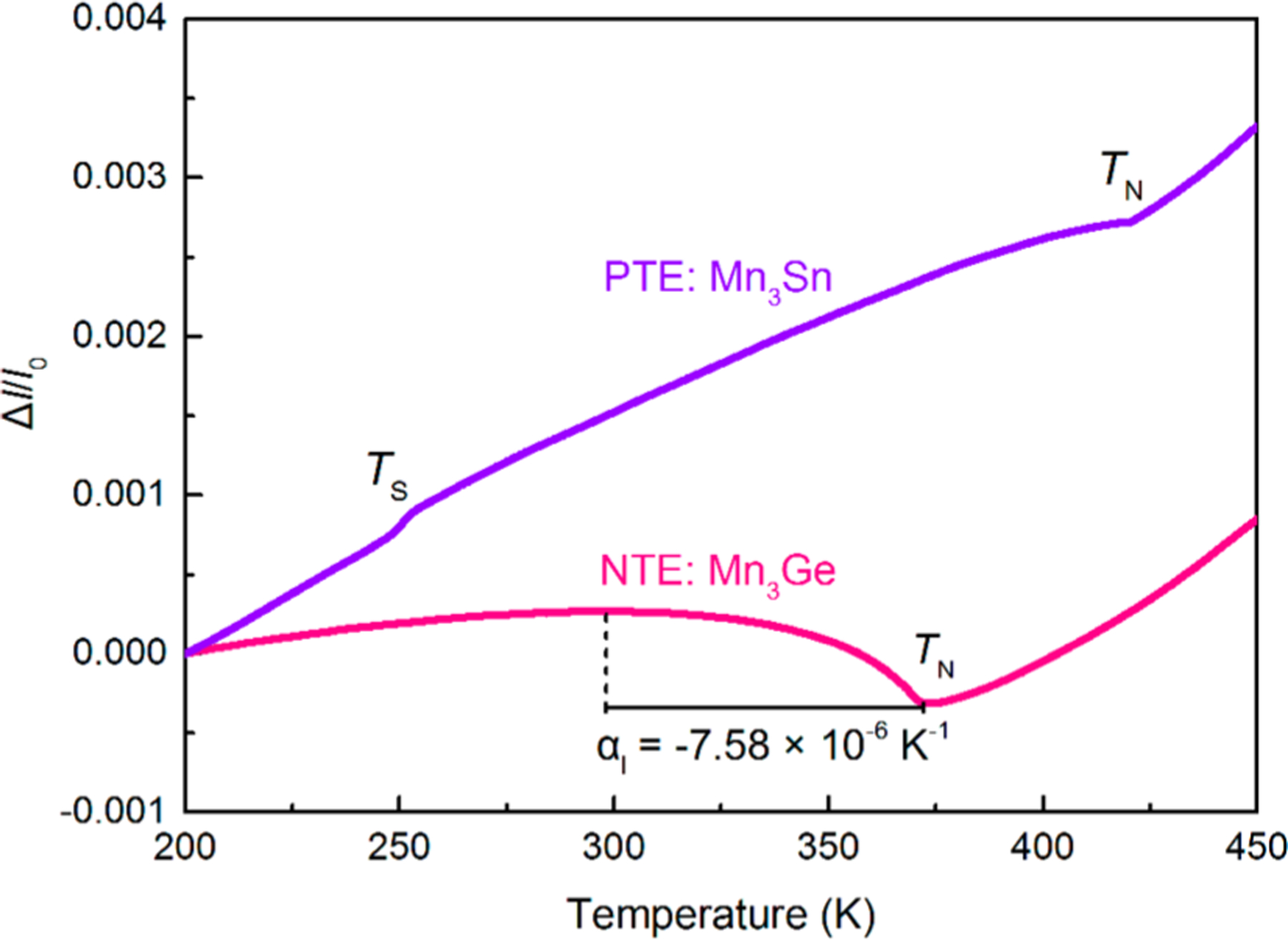

Intriguingly, Mn3Ge exhibit a strong NTE property. No structure phase transition occurs in the NTE temperature range. The average linear CTE of Mn3Ge is , which was determined via a macroscopic thermo-dilatometer measurement (Figure 2). However, the isostructural compound of Mn3Sn shows an opposite PTE at the whole temperature range. Two inflection points are associated with the magnetic transitions. The temperature dependence of the unit cell volume, which was determined via NPD, can also confirm the reliability of NTE (Figure 4b). As a comparison, the present Mn3Ge exhibits an NTE magnitude similar to that of other typical NTE inorganics, such as ScF3 (, )16,38 and ZrW2O8 (, ).1 Note that most available NTE alloys are ferromagnetic (FM), whereas the present Mn3Ge exhibits an antiferromagnetic structure. Furthermore, even a high Neel temperature is found in the present Mn3Ge when compared with other antiferromagnetic intermetallic compounds, such as YMn2 ,39 Gd5Ge4 ,40 and CeFe2 .41 Because of the magnetostriction effect, the dimensions of FM alloys can be influenced by the external magnetic field. However, AFM compounds can avoid the negative effect of the external magnetic field on the precise dimension.

Figure 2.

Opposite thermal expansion in the isostructural antiferromagnetic intermetallics of Mn3Ge and Mn3Sn determined by a dilatometer . NTE is observed in Mn3Ge, whereas PTE in the isostructural Mn3Sn. and are the tempratures of magnetic transition.

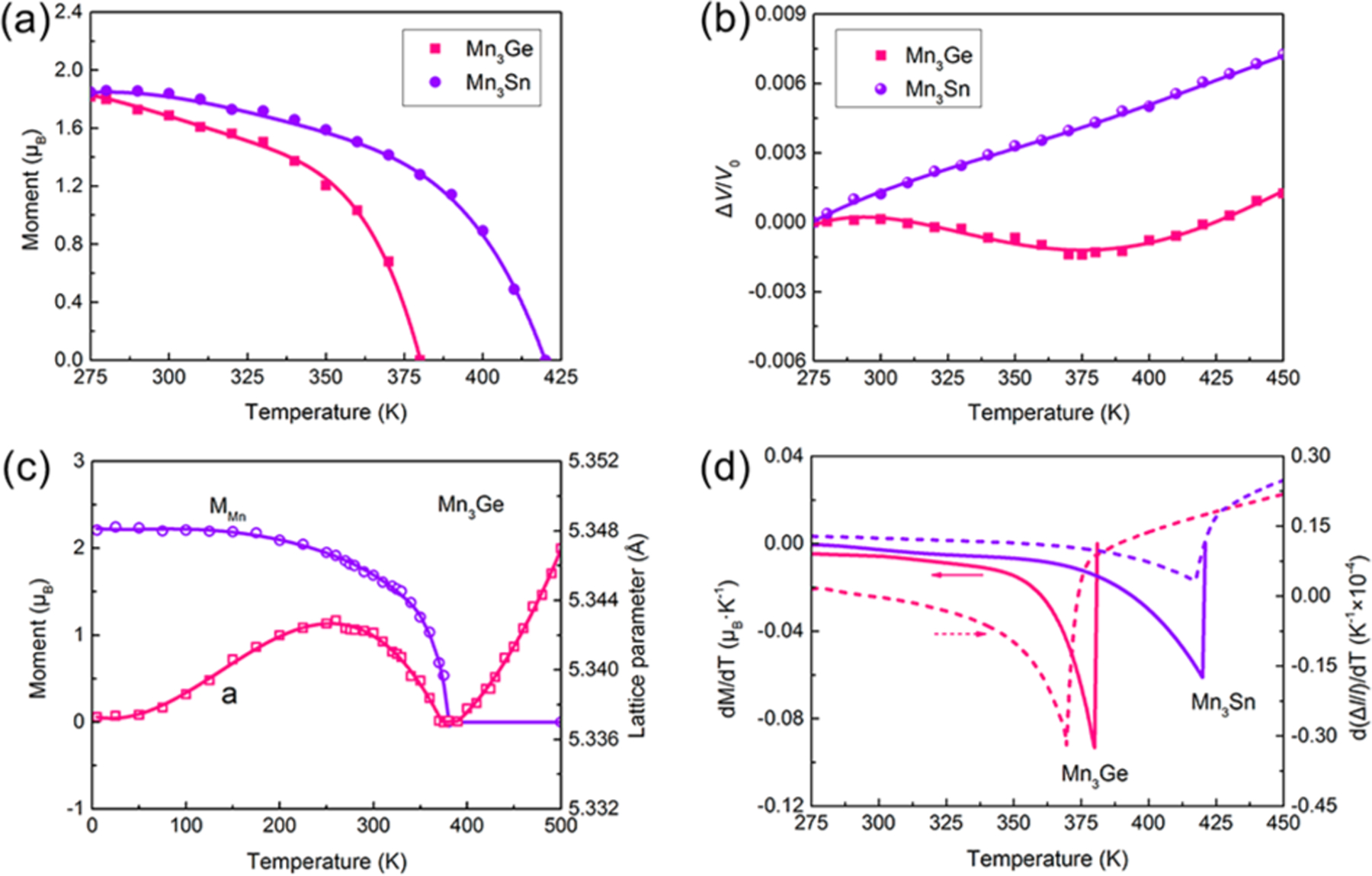

Figure 4.

NTE mechanism of Mn3Ge. Temperature dependence of (a) the Mn moments of Mn3Ge and Mn3Sn, (b) the relative change in unit cell volume of Mn3Ge and Mn3Sn, (c) the Mn moment and lattice parameter of Mn3Ge, and (d) and of Mn3Ge and Mn3Sn.

The macroscopic magnetic behavior of Mn3Ge was studied by measuring the temperature dependence of magnetization (zero-field-cooling (ZFC) and field-cooling (FC) modes) (Figure S5a). An obvious peak of the ZFC curve (100 Oe) can be seen, which reveals the feature of the AFM transition. The Neel temperature is determined to be 370 K. With increasing external magnetic field, the magnetization of the residual FM component is increased, which overwhelms the signal of the AFM structure. Note that the very small residual FM component is caused by a small distortion of the hexagonal structure.42 Furthermore, the magnetic transition temperature is hardly changed by the external magnetic field, which verifies the stability of the triangular antiferromagnetic structure. Isothermal magnetization curves of Mn3Ge measured at various temperatures are shown in Figure S6. The dominating AFM nature is clearly indicated by the linear and unsaturated magnetization behavior at higher fields. In Figure S5b, there are two obvious magnetic transitions at 255 K and above 400 K for Mn3Sn, which are consistent with the dilatometer result. In addition, the magnetic transition temperature of Mn3Ge is close to the disappearing temperatures of NTE (Figure 2 and Figure S5), indicating that the anomalous thermal expansion phenomenon of Mn3A (A = Ge, Sn) is entangled with the magnetic behavior.

In the purpose of explaining opposite thermal expansion in the isostructural noncollinear antiferromagnetic intermetallics of Mn3A (A = Ge and Sn), the microscopic thermal expansion information was extracted from the results of magnetic structure refinement of high-intensity NPD (Figure S4). The temperature dependence of the lattice parameters extracted from the NPD data is shown in Figure S7. Obviously, the NTE of Mn3Ge is dominated by the shrinking of the axis; nevertheless, the axis linearly expands. However, in Mn3Sn both and axes linearly expand. It means that such opposite thermal expansion is correlated to the plane.

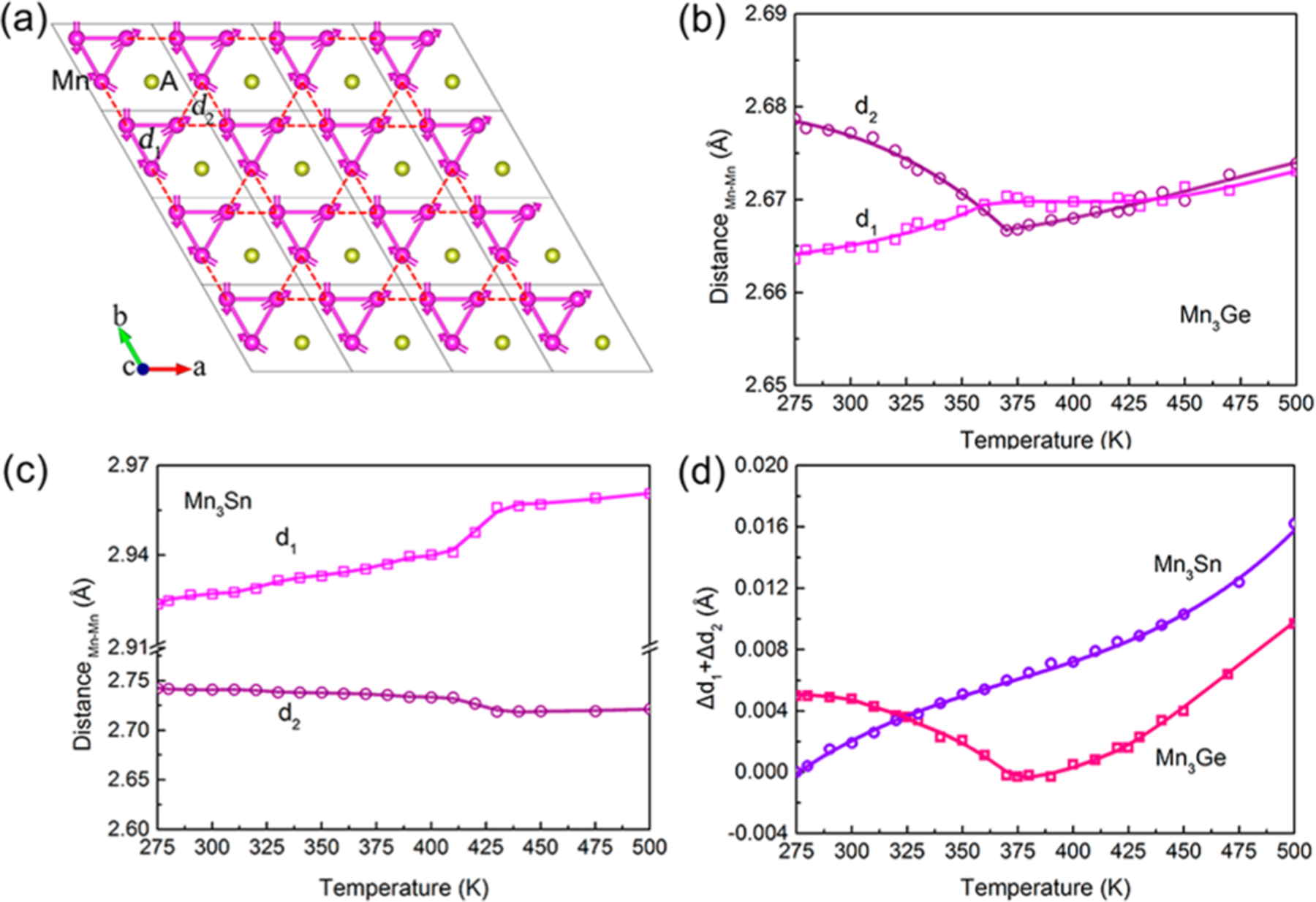

To study the detailed behavior for the shrinkage of the plane, the bond distances between different magnetic atoms (Mn) were extracted from variable temperature NPD data. Figure 3a shows a supercell of the plane for Mn3A (A = Ge and Sn), and sign the bond distances of Mn–Mn (I) and Mn–Mn (II), respectively. As shown in Figure 3b,c, always increases in the whole temperature range for both Mn3Ge and Mn3Sn. However, takes place to shrink at different level below magnetic transition temperature. The total change of and shows the same behavior with that of the axis, which exhibits NTE for Mn3Ge but PTE for Mn3Sn below magnetic transition temperatures (Figure 3d). Therefore, the NTE of Mn3Ge is due to the decrease in the bond distance , which is caused by MVE.

Figure 3.

Temperature dependence of bond distances between different sites of magnetic Mn atoms for NTE Mn3Ge and PTE Mn3Sn. (a) A layer of atoms in ab plane of supercell for Mn3A (A = Ge and Sn), and mean the bond distances of Mn–Mn (I) and Mn–Mn (II) in the ab plane, respectively. Temperature dependence of and for (b) Mn3Ge, and (c) Mn3Sn. (d) Temperature dependence of relative change of Δd1+Δd2 for Mn3A (A = Ge and Sn).

The more detailed magnetic and crystal structure information was extracted from NPD data to reveal the detailed MVE of Mn3Ge and Mn3Sn. As shown in Figure 4a, it is interesting to note that the Mn moments of Mn3Ge and Mn3Sn are nearly identical at 275 K, but nonlinearly decrease and vanish at for Mn3Ge and for Mn3Sn. It seems that the AFM order can be more easily disturbed in Mn3Ge than Mn3Sn. Figure 4c shows the strong coupling role between magnetism and lattice in the NTE Mn3Ge. As the Mn magnetic moment drops slowly at low temperatures (below 275 K), the lattice parameter expands, i.e., PTE occurs; however, when the magnetic moment drops quickly (275–375 K), begins to shrinks, i.e., NTE happens. To further study the relation between magnetism and thermal expansion, the trends of and are calculated for both Mn3Ge and Mn3Sn (Figure 4d). Clearly, a similar tendency can be observed in both magnetic moment and macroscopical thermal expansion of Mn3A (A = Ge and Sn) as a function of temperature. With increasing temperature, the magnetic moment decreases rapidly or slowly, the property of thermal expansion changes accordingly. The rate of magnetic transition dominates the thermal expansion of Mn3A (A = Ge and Sn), which is directly associated with the Mn moments lying the plane. The rate of magnetic transition in NTE Mn3Ge is stronger than that of PTE Mn3Sn, which means a stronger contribution of spontaneous magnetostriction to thermal contraction. Therefore, the bonds of Mn–Mn in Mn3Ge shrink more obviously than Mn3Sn, which exceeds the expansion of the bond distance . The NTE occurs in Mn3Ge (Figure 3).

In other words, the Wigner–Seitz volume of Mn3Sn is expanded due to the existence of bigger Sn atoms, resulting in the increase of Mn–Mn bond length (Figure S1). The longer of Mn–Mn distance makes the antiferromagnetic exchange interaction stronger in Mn3Sn, which is also evidenced by the higher in Mn3Sn compared with in Mn3Ge. Theoretically, when the exchange interaction is enhanced, the compound needs more energy to break magnetic ordering. Therefore, the spins of Mn3Sn depart from parallel alignment more difficultly than Mn3Ge with increasing temperature, i.e., the rate of magnetic transition in Mn3Sn is slower than that of Mn3Ge (Figure 4d). It is known that magnetic configuration with aligned spins has a larger volume than that with disordered spins,24 which means the magnetic transition brings a negative contribution to thermal expansion. Because of the faster magnetic transition, the contribution to lattice change from magnetic order overwhelms that from lattice thermal vibration. As a result, the overall thermal expansion of Mn3Ge becomes negative (Figure 4b). However, the spontaneous magnetostriction of Mn3Sn is relatively weak, which cannot overcome positive contribution to thermal expansion from lattice vibration. PTE happens at the whole temperature range. The change of magnetic moment control the NTE property should be the common feature for most magnetic NTE compounds, such as Mn3AN.43–45

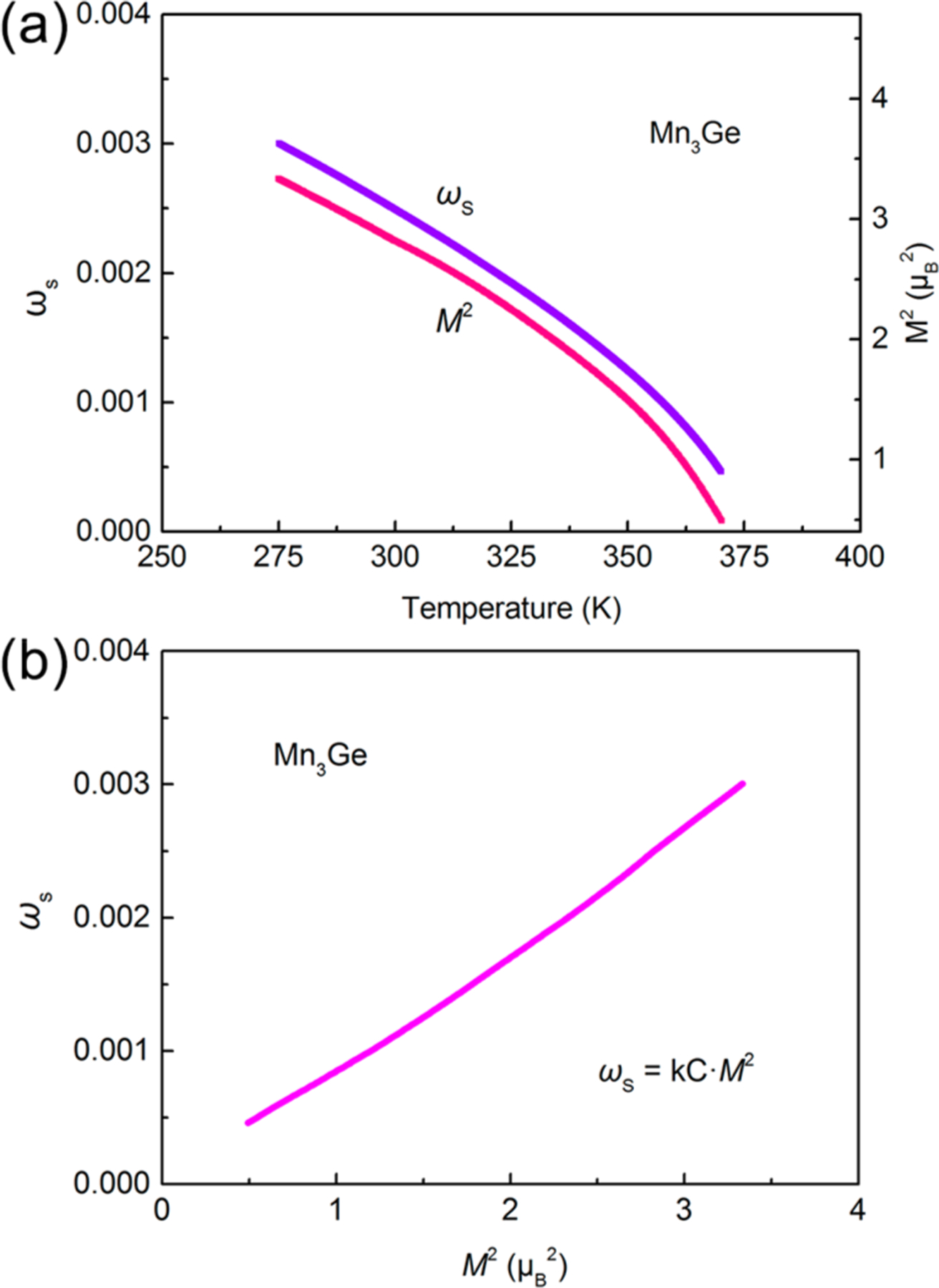

To quantify the relationship between magnetic contribution and thermal expansion, spontaneous magnetostriction is used to quantitatively describe the contribution of MVE to anomalous thermal expansion.46,47 The value of is calculated by , in which is the experimental linear thermal expansion measured by thermos-dilatometer, and is the linear thermal expansion of a nonmagnetic reference.48 As shown in Figure S8, the NTE property of Mn3Ge can be regarded as a combined result of and lattice vibration . Here, temperature dependence of both the square of Mn moment and is performed for the detailed analysis of NTE mechanism of Mn3Ge. As depicted in Figure 5a,b, it is obvious to reveal a strong linear correlation between and , which can be quantitatively ascribed by the equation of

| (1) |

Figure 5.

(a) Temperature dependence of the square of Mn moment and spontaneous magnetostriction in Mn3Ge. (b) Quantitative relationship between and .

where and are the compressibility and the magnetovolume coupling constant, and is the amplitudes of Mn magnetic moment.49,50 It means that the magnetic contribution and the thermal expansion have a quantitative relationship, and thus thermal expansion can be tuned by changing the magnetic ordering.

From the practical application viewpoint, better performances in terms of high mechanical strength and good thermal and electron conductivity properties are demanded for NTE materials. The engineering stress–strain curves of Mn3Ge ingots are shown in Figure S9. The maximum compressive strength can be as large as 204 MPa, together with a total elongation of 5.4%. As a comparison, the compressive strength of the Nd–Fe–B-based permanent magnets and that of the La(Fe,Si)13-based magnetic refrigeration materials are 112 MPa, and 120 MPa, respectively.51,52 It is well-known that intermetallic compounds are generally very fragile, and are thus unsuitable for compressive or tensile tests. In general, to improve the mechanical property of NTE intermetallic compounds, binder is often introduced to bond powders of alloys. For example, the as-prepared MnCoGe-based alloys are brittle and spontaneously fragment into powders. Their compressive strength increases to 70.4 MPa after using epoxy-binder as a bonder.11 The temperature dependence of the metallic property of Mn3Ge is also depicted in Figure S10. At room temperature, the thermal conductivity is , which is much larger than that of most NTE inorganic compounds, such as the prototype NTE oxide of ZrW2O8 Furthermore, the electrical conductivity of the present NTE Mn3Ge is . As a comparison, most NTE inorganic solids are insulating. Their electrical conductivity is linearly reduced upon heating, which reveals the characteristic of metallic conductivity.

The present Mn3Ge exhibit a new and simple structure type for the NTE property, which yields a new class of antiferromagnetic NTE compounds. The control of thermal expansion can be achieved in Mn3Ge-based compounds via chemical modification similar to that often utilized for NTE materials, such as ScF316,17,38 and antiperovskites.3,14,15 For example, the solid solutions of have been investigated (Figure S1). Thermal expansion of gradually transforms from NTE to PTE with increasing Sn concentration.

In summary, a new and simple NTE structure type has been found in antiferromagnetic compounds of Mn3Ge. The unusual inverse triangular antiferromagnetic structure of Mn3Ge was confirmed via variable temperature NPD and macroscopic magnetic measurements. The direct experimental evidence reveals the contribution of the magnetovolume effect to the anomalous thermal expansion of Mn3Ge, compared with the isostructural PTE Mn3Sn. The NTE property of Mn3Ge originates from the quick decrease of Mn moments which causes the shrink of the bond distances of Mn–Mn . The present NTE Mn3Ge exhibits the antiferromagnetic property which can thus avoid the influence of the external magnetic field on the dimensions. Furthermore, the high mechanical properties and good metallic property of the present NTE Mn3Ge provide a greater possibility for better industrial applications in the future.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 21731001 and 21590793), the Changjiang Young Scholars Award, and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, China (FRF-TP-17-001B). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. The NPD data was collected at the high-intensity diffractometer Wombat of the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANSTO) and the BT-1 neutron powder diffractometer at the NIST Center for Neutron Research.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.8b03283.

Materials synthesis, experimental methods, data analysis procedures (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Mary TA; Evans JSO; Vogt T; Sleight AW Negative Thermal Expansion from 0.3 to 1050 K in ZrW2O8. Science 1996, 272, 90–92. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Chen J; Hu L; Deng J; Xing XR Negative Thermal Expansion in Functional Materials: Controllable Thermal Expansion by Chemical Modifications. Chem. Soc. Rev 2015, 44, 3522–3567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Takenaka K Negative Thermal Expansion Materials: Technological Key for Control of Thermal Expansion. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater 2012, 13, 013001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Evans JSO; Hanson PA; Ibberson RM; Duan N; Kameswari U; Sleight AW Low-Temperature Oxygen Migration and Negative Thermal Expansion in ZrW2‑xMoxO8. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2000, 122, 8694–8699. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Long YW; Hayashi N; Saito T; Azuma M; Muranaka S; Shimakawa Y Temperature-Induced A–B Intersite Charge Transfer in an A-Site-Ordered Lacu3fe4o12 Perovskite. Nature 2009, 458, 60–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Azuma M; Chen WT; Seki H; Czapski M; Olga S; Oka K; Mizumaki M; Watanuki T; Ishimatsu N; Kawamura N; et al. Colossal Negative Thermal Expansion in BiNiO3 Induced by Intermetallic Charge Transfer. Nat. Commun 2011, 2, 347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Chen J; Nittala K; Forrester JS; Jones JL; Deng J; Yu R; Xing X The Role of Spontaneous Polarization in The Negative Thermal Expansion of Tetragonal PbTiO3-Based Compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 11114–11117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Guillaume CÉ Recherches sur les aciers au nickel. Dilatations Aux Tempeŕatures eĺeveés; Reśistance eĺectrique. CR Acad. Sci 1897, 125, 18. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Álvarez-Alonso P; Gorria P; Blanco JA; Sańchez-Marcos J; Cuello GJ; Puente-Orench I; Llamazares JLS; Rodriguez-Velamazan JA; Garbarino G; de Pedro I; et al. Magnetovolume and Magnetocaloric Effects in Er2Fe17. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys 2012, 86, 184411. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Song YZ; Chen J; Liu X; Wang CC; Gao Q; Li Q; Hu L; Zhang J; Zhang S; Xing X Structure, Magnetism, and Tunable Negative Thermal Expansion in (Hf,Nb)Fe2 Alloys. Chem. Mater 2017, 29, 7078–7082. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Zhao YY; Hu FX; Bao LF; Wang J; Wu H; Huang QZ; Wu R-R; Liu Y; Shen F-R; Kuang H; et al. Giant Negative Thermal Expansion in Bonded MnCoGe-Based Compounds with Ni2In-Type Hexagonal Structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 1746–1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Huang R; Liu Y; Fan W; Tan J; Xiao F; Qian L; Li L Giant Negative Thermal Expansion in NaZn13-Type La(Fe, Si, Co)13 Compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 11469–11472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Song YZ; Chen J; Liu X; Wang C; Zhang J; Liu H; Xing XR; Zhu H; Hu L; Lin K; et al. Zero Thermal Expansion in Magnetic and Metallic Tb(Co,Fe)2 Intermetallic Compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 602–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Takenaka K; Takagi H Giant Negative Thermal Expansion in Ge-Doped Anti-Perovskite Manganese Nitrides. Appl. Phys. Lett 2005, 87, 261902. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Wang C; Chu L; Yao Q; Sun Y; Wu M; Ding L; Yan J; Na Y; Tang W; Li G; et al. Tuning the Range, Magnitude, and Sign of the Thermal Expansion in Intermetallic Mn3(Zn,M)xN (M = Ag, Ge). Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys 2012, 85, 220103. [Google Scholar]

- (16).Greve BK; Martin KL; Lee PL; Chupas PJ; Chapman KW; Wilkinson AP Pronounced Negative Thermal Expansion from a Simple Structure: Cubic ScF3. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 15496–15498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Hu L; Chen J; Xu J; Wang N; Han F; Ren Y; Pan Z; Rong Y; Huang R; Deng J; et al. Atomic Linkage Flexibility Tuned Isotropic Negative, Zero, and Positive Thermal Expansion in MZrF6 (M= Ca, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, and Zn). J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 14530–14533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Attfield JP Condensed-Matter Physics: A Fresh Twist on Shrinking Materials. Nature 2011, 480, 465–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Goodwin AL; Calleja M; Conterio MJ; Dove MT; Evans JS; Keen DA; Peters L; Tucker MG Colossal Positive and Negative Thermal Expansion in the Framework Material Ag3[Co(CN)6]. Science 2008, 319, 794–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Goodwin AL; Kennedy BJ; Kepert CJ Thermal Expansion Matching via Framework Flexibility in Zinc Dicyanometallates. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 6334–6335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Duyker SG; Peterson VK; Kearley GJ; Ramirez-Cuesta AJ; Kepert CJ Negative Thermal Expansion in LnCo(CN)6 (Ln= La, Pr, Sm, Ho, Lu, Y): Mechanisms and Compositional Trends. Angew. Chem 2013, 125, 5374–5378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Gao Q; Chen J; Sun Q; Chang D; Huang Q; Wu H; Sanson A; Milazzo R; Zhu H; Li Q; et al. Switching between Giant Positive and Negative Thermal Expansions of A YFe(CN)6-based Prussian Blue Analogue Induced by Guest Species. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2017, 56, 9023–9028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Zheng XG; Kubozono H; Yamada H; Kato K; Ishiwata Y; Xu CN Giant Negative Thermal Expansion in Magnetic Nanocrystals. Nat. Nanotechnol 2008, 3, 724–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).van Schilfgaarde M; Abrikosov IA; Johansson B Origin of The Invar Effect in Iron-Nickel Alloys. Nature 1999, 400, 46–49. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Rebello A; Neumeier JJ; Gao Z; Qi Y; Ma Y Giant Negative Thermal Expansion in La-Doped CaFe2As2. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys 2012, 86, 104303. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Fujishita H; Hayashi Y; Saito M; Unno H; Kaneko H; Okamoto H; Ohashi M; Kobayashi Y; Sato M X-Ray Diffraction Study of Spontaneous Strain in Fe-Pnictide Superconductor, NdFeAsO0.89 F0.11. Eur. Phys. J. B 2012, 85, 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- (27).Sleight A Materials Science: Zero-Expansion Plan. Nature 2003, 425, 674–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Nix FC; MacNair D The Thermal Expansion of Pure Metals: Copper, Gold, Aluminum, Nickel, and Iron. Phys. Rev 1941, 60, 597. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Miracle DB Metal Matrix Composites–from Science to Technological Significance. Compos. Sci. Technol 2005, 65, 2526–2540. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Della Gaspera E; Tucker R; Star K; Lan EH; Ju YS; Dunn B Copper-Based Conductive Composites with Tailored Thermal Expansion. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 10966–10974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Ruch PW; Beffort O; Kleiner S; Weber L; Uggowitzer PJ Selective Interfacial Bonding in Al (Si)–Diamond Composites and Its Effect on Thermal Conductivity. Compos. Sci. Technol 2006, 66, 2677–2685. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Ryelandt S; Mertens A; Delannay F Al/Stainless-Invar Composites with Tailored Anisotropy for Thermal Management in Light Weight Electronic Packaging. Mater. Des 2015, 85, 318–323. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Vogelsang M; Arsenault RJ; Fisher RM An in Situ HVEM Study of Dislocation Generation at Al/SiC Interfaces in Metal Matrix Composites. Metall. Trans. A 1986, 17, 379–389. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Mohn P A Century of Zero Expansion. Nature 1999, 400, 18–19. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Moessner R; Ramirez AP Geometrical Frustratio. Phys. Today 2006, 59, 24. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Tomiyoshi S; Yamaguchi Y; Nagamiya T Triangular Spin Configuration and Weak Ferromagnetism of Mn3Ge. J. Magn. Magn. Mater 1983, 31, 629–630. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Cable JW; Wakabayashi N; Radhakrishna P Magnetic Excitations in the Triangular Antiferromagnets Mn3Sn and Mn3Ge. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys 1993, 48, 6159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Chen J; Gao Q; Sanson A; Jiang X; Huang Q; Carnera A; Lin K Tunable Thermal Expansion in Framework Materials through Redox Intercalation. Nature Commun 2017, 8, 14441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Nakamura Y Magnetovolume Effects in Laves Phase Intermetallic Compounds. J. Magn. Magn. Mater 1983, 31, 829–834. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Morellon L; Blasco J; Algarabel PA; Ibarra MR Nature of the First-Order Antiferromagnetic-Ferromagnetic Transition in the Ge-rich Magnetocaloric Compounds Gd5(SixGe1–x)4. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys 2000, 62, 1022. [Google Scholar]

- (41).Roy SB; Perkins GK; Chattopadhyay MK; Nigam AK; Sokhey KJS; Chaddah P; Caplin AD; Cohen LF First Order Magnetic Transition in Doped CeFe2 Alloys: Phase Coexistence and Metastability. Phys. Rev. Lett 2004, 92, 147203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Sandratskii LM; Kübler, J. Role of Orbital Polarization in Weak Ferromagnetism. Phys. Rev. Lett 1996, 76, 4963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Takenaka K; Ichigo M; Hamada T; Ozawa A; Shibayama T; Inagaki T; Asano K Magnetovolume Effects in Manganese Nitrides with Antiperovskite Structure. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater 2014, 15, 015009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Song X; Sun Z; Huang Q; Rettenmayr M; Liu X; Seyring M; Li G; Rao G; Yin F Adjustable Zero Thermal Expansion in Antiperovskite Manganese Nitride. Adv. Mater 2011, 23, 4690–4694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Deng S; Sun Y; Wu H; Huang Q; Yan J; Shi K; Malik MI; Lu H; Wang L; Huang R; et al. Invar-Like Behavior of Antiperovskite Mn3+xNi1–xN Compounds. Chem. Mater 2015, 27, 2495–2501. [Google Scholar]

- (46).Ibarra MR; Algarabel PA; Marquina C; Blasco J; Garcia J Large Magnetovolume Effect in Yttrium Doped La-Ca-Mn-O Perovskite. Phys. Rev. Lett 1995, 75, 3541–3544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Takenaka K; Takagi H Magnetovolume Effect and Negative Thermal Expansion in Mn3(Cu1−xGex)N. Mater. Trans 2006, 47, 471–474. [Google Scholar]

- (48).Sayetat F; Fertey P; Kessler M An Easy Method for the Determination of Debye Temperature from Thermal Expansion Analyses. J. Appl. Crystallogr 1998, 31, 121–127. [Google Scholar]

- (49).Moriya T; Usami K Magneto-volume Effect and Invar Phenomena in Ferromagnetic Metals. Solid State Commun 1980, 34, 95–99. [Google Scholar]

- (50).Fujita A; Fukamichi K; Wang JT; Kawazoe Y Large Magnetovolume Effects and Band Structure of Itinerant-electron Metamagnetic La(FexSi1−x)13 Compounds. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys 2003, 68, 104431. [Google Scholar]

- (51).Drak M; Dobrzanśki, L. A. Hard Magnetic Materials Nd-Fe-B/Fe with Epoxy Resin Matrix. J. Achiev. Mater. Manuf. Eng 2007, 24, 63–66. [Google Scholar]

- (52).Zhang H; Sun Y; Niu E; Hu F; Sun J; Shen B Enhanced Mechanical Properties and Large Magnetocaloric Effects in Bonded La(Fe,Si)13-Based Magnetic Refrigeration Materials. Appl. Phys. Lett 2014, 104, 062407. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.