Abstract

Trimethylamine N-Oxide (TMAO) is an important metabolite, which is derived from choline, betaine, and carnitine in various organisms. In humans, it is synthesized through gut microbiota and is abundantly found in serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Although TMAO is a stress protectant especially in urea-rich organisms, it is an atherogenic agent in humans and is associated with various diseases. Studies have also unveiled its exceptional role in protein folding and restoration of mutant protein functions. However, most of these data were obtained from studies carried on fast-folding proteins. In the present study, we have investigated the effect of TMAO on the folding behavior of a well-characterized protein with slow folding kinetics, carbonic anhydrase (CA). We discovered that TMAO inhibits the folding of this protein via its effect on proline cis–trans isomerization. Furthermore, TMAO is capable of inducing cell cycle arrest. This study highlights the potential role of TMAO in developing proteopathies and associated diseases.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00018-021-04087-z.

Keywords: TMAO, Protein misfolding, Proline, Cis–trans isomerization

Introduction

Folding of proteins into their unique 3D structure is crucial for gaining biological functions [1]. Loss or gain in biological function due to the defects in protein folding is a common hallmark of a large number of human diseases, including neurodegeneration [2–8], cardiovascular diseases [9, 10], and metabolic disorders [3, 11, 12], etc. Several small molecule metabolites (trehalose, proline, taurine, betaine, ectoine, etc.) have been known to influence protein folding pathways or alter their energy landscapes, and therefore, are considered promising therapeutic molecules for such diseases. Among such molecules, trimethylamine N-Oxide (TMAO) has been given remarkable attention by researchers as it is considered to be an exceptional protein folding enhancing agent [13, 14].

TMAO is generally obtained from choline, carnitine, and betaine in various organisms. In humans, carnitine, choline, and phosphatidylcholine are first metabolized to trimethylamine (TMA) by the action of gut microbiota. TMA is further converted to TMAO by the hepatic flavin-containing monooxygenase 3 (FMO3) and released into the blood [15]. It is not only present in the blood but could cross the blood–brain barrier and accumulate at high levels in the cerebrospinal fluid [16]. Elevated plasma TMAO levels are associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and major adverse cardiac events in patients with stable coronary artery disease (CAD) [17, 18], acute coronary syndrome [19, 20], plaque rupture in patients with CAD [21], and ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) [22]. Furthermore, close associations are also seen in neurodegeneration [23, 24], chronic kidney disease [25], and cancer [26], etc.

The role of TMAO on protein folding has been studied for various proteins in vitro and in vivo. It has been known that it is an exceptional protein stabilizer and could restore the function of various mutant proteins [13, 14]. However, a systematic literature search revealed that almost all such studies are confined to proteins having fast-folding kinetics. Its effect on proteins with the slow folding kinetics has been largely unexplored. Keeping in mind that slow folding proteins are prone to misfolding or being confined in the kinetic traps, an important question is how does TMAO affect the folding of such proteins. In the present communication, we have investigated the effect of TMAO on a well-characterized slow folding protein, carbonic anhydrase (CA). In fact, it was shown that two slow stages in refolding of this protein (the slow with the relaxation time t1/2 of ~ 120 s and the super-slow with the t1/2of ~ 600 s) are due to cis–trans isomerization of proline residues [27]. Our major discovery is that TMAO affects the step of the proline cis–trans isomerization and induces inhibition of the CA folding. The study highlights the possible involvement of TMAO in altering proteostasis and associated biological processes including endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress signaling.

Results

TMAO fails to induce folding of CA

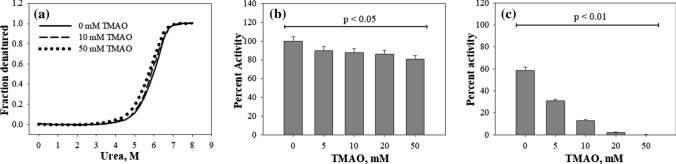

We have, first of all, investigated the effect that TMAO has on the native state of CA by measuring the thermodynamic stability and functional activity of CA in the absence or presence of different TMAO concentrations (Fig. 1). Figure 1a shows that TMAO does not alter the Cm of the protein while having small decrease in ΔGDo (see Table S1). Similarly, we also observed only 10–20% decrease in the CA activity in the presence of TMAO (Fig. 1b). However, upon refolding in presence of TMAO, we observed no gain in CA activity at 20–50 mM and large reduction at 5–10 mM (Fig. 1c). Such a loss of functional recovery of refolded CA indicates that TMAO might be acting on the folding pathway.

Fig. 1.

Effect of TMAO on stability and folding behavior of CA. Urea denaturation profiles (a) obtained in the absence of TMAO and in the presence of TMAO. For clarity we have not shown denaturation profiles in the presence of 10 mM and 20 mM TMAO; Percent activity of native CA (b) and refolded CA (c) in the absence and presence of TMAO. Error bars represent error from mean

The inhibition of CA refolding is unique to TMAO

There are also other protein folding enhancing molecules in the cellular environment. These include free amino acids (e.g., glycine and proline), polyols, sugars (e.g., glycerol, sorbitol, trehalose, and sucrose), and methylamines (e.g., TMAO, betaine, and sarcosine). Therefore, we have further investigated if the effect on CA is confined to TMAO by performing enzyme activity measurement of native and refolded CA obtained in the presence of several such molecules (Fig. S1 and S2). We observed that all these agents either increased CA activity or does not exhibit an effect (Fig. S1). In the case of refolded CA, there was an overall increase in the measured CA activities as compared to the refolded control (Fig. S2). Although the activity measurement of CA has not been performed previously with these agents, the results are in agreement with the observations made for other enzymes [28].

TMAO does not affect the native state structure of CA

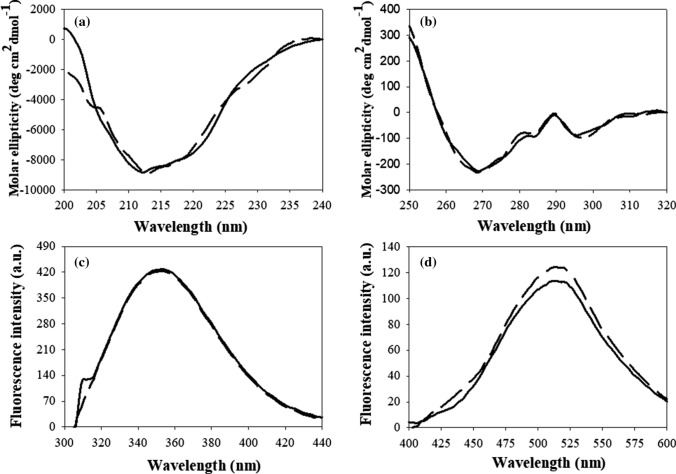

We analyzed the effect of TMAO on structural properties of the native CA using multiple spectroscopic probes. Far-UV CD measurements revealed that protein secondary structure was not significantly altered by TMAO treatment (Fig. 2a). We also found no significant change in the CA tertiary structure as revealed by the near-UV CD measurements (Fig. 2b), since the spectral properties of this protein in the absence and presence of TMAO were identical. We have further performed intrinsic fluorescence analysis to verify the near-UV CD observations. As seen in Fig. 2c, there is no change in the environment of tryptophan/tyrosine residues upon the addition of TMAO. Therefore, results on the intrinsic tryptophan/tyrosine fluorescence agree well with that of the near-UV CD data. Since CA contains 7 tryptophan and 8 tyrosine residues, which are spread over the entire CA sequence, these measurements report on the overall structural organization of this protein. Lack of alteration in the secondary or tertiary structure might mean that hydrophobic clusters should not be exposed to the solvent. To examine this possibility, we have measured 1-anilino-naphthalene-8-sulfonate (ANS) binding propensity of the native CA in the absence and presence of TMAO. ANS is a hydrophobic fluorescent dye that specifically binds to the solvent-exposed hydrophobic clusters [29] and therefore, is commonly used for the analysis of partially folded species since this interaction is accompanied by the dramatic increase in the ANS fluorescence intensity and the characteristic blue shift of maximal ANS fluorescence [30]. Figure 2d shows that there is no significant difference in binding propensity of ANS to the TMAO-treated or untreated CA, further corroborating the premise that the native structure of CA is mostly unperturbed by TMAO.

Fig. 2.

Conformational properties of native CA in the presence of TMAO. Far-UV CD spectra (a), near-UV CD spectra (b), intrinsic Trp/Tyr fluorescence spectra (c), and ANS fluorescence spectra (d) of native CA incubated at 25 ˚C overnight in the presence of TMAO. Solid line and dashed line represent CA in the absence and presence of 50 mM TMAO, respectively

Refolded CA does not form aggregate

TMAO treatment might induce the formation of high-order oligomers leading to the functional impairment of CA. To check this possibility, we analyzed if the refolded CA generated in the presence of TMAO forms aggregate by measuring light scattering intensity (Fig. 3a). It is seen in this figure that in the presence and absence of TMAO, there was no increase in the light scattering intensity indicating the absence of detectable high-order oligomers. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Fig. 3b) further confirmed the absence of aggregates.

Fig. 3.

Oligomeric state of CA in the presence of TMAO. Light scattering intensity at 400 nm (a) and Transmission Electron micrographs (b) of CA incubated overnight with 50 mM TMAO at 25 ˚C

TMAO inhibits CA refolding by disrupting Uf state

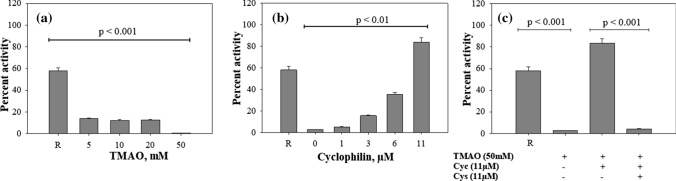

CA is known to fold from its unfolded, Us state to native state via Uf intermediate (as shown in Eq. 1). Indeed, Us and Uf can also be generated with the help of different methods of GdmCl-induced denaturation. Short-term (10 s) incubation and long-term incubation (more than 2 h) with GdmCl result in the formation of Uf and Us species, respectively [31]. To investigate the effect of TMAO on the Uf state of CA, we analyzed the catalytic activity of the refolded CA obtained after the short-term incubation with GdmCl (for 10 s) (Fig. 4a). Comparison of these results with the corresponding data obtained for Us (incubated overnight with GdmCl) (Fig. 1c) revealed a similar pattern of activity loss (although the magnitudes are slightly different). It is also further observed in Fig. 4a that the activity of the refolded CA decreased by ~ 80% at lower concentrations of TMAO (5 to 20 mM), and at the highest concentration, there was barely any activity. The results indicated that TMAO affected the structural integrity of the Uf state.

Fig. 4.

Effect of TMAO on the cis–trans prolyl isomerization of CA. Enzyme activity of refolded CA upon short-term denaturation (10 s, at 2 °C) in the presence and absence of TMAO (a) and upon refolding in presence of TMAO–Cyclophilin (b). To confirm the effect of cyclophilin, refolding of CA was performed in the presence of TMAO (50 mM), Cyclophilin D (11 µM), and Cyclosporin (11 µM) (c). R represents refolded control. Cyc and Cyp represents cyclophilin and cyclosporin, respectively

Structural characteristics of the TMAO-induced refolded state

We have further examined the conformation of the TMAO-induced refolded state using multiple spectroscopic probes (Fig. 5). Figure 5a, b show the far-UV and near-UV CD spectra of CA refolded in presence of TMAO. It is seen in this figure that the refolded state in the presence of TMAO is characterized by rather specific spectral characteristics as compared to the refolded control (in absence of TMAO). This is evident from the presence of characteristic spectral features of CD spectra (in the far- and near-UV regions) being somewhat closer to the spectra of the GdmCl-unfolded state (Us). On the other hand, intrinsic fluorescence (Fig. 5c) analysis revealed the presence of the noticeable blue shift in the case of the TMAO-induced refolded state as compared to the Us, suggesting a significant difference between these two states in terms of the micro-environments of their chromophoric groups. The pronounced blue shift of the intrinsic fluorescence indicated that in case of CA refolded in presence of TMAO, the chromophores were buried in a hydrophobic core, whereas in the Us state they were predominantly solvent exposed. Furthermore, compared to the refolded control, the TMAO-induced state apparently had chromophores that were more toward the polar environment as evident from the observed hypochromicity (Fig. 5c). Differences in the micro-environment of the chromophores among the different states might mean that the exposure pattern of the hydrophobic groups to the solvent might be different. Figure 5d shows that there is no significant difference in the binding behavior of ANS between the TMAO-induced folded state as compared to the Us. However, there are large differences between the refolded control and TMAO-induced state (exemplified by the significant red-shift and hyperchromicity).

Fig. 5.

Conformational properties of CA in the TMAO-induced state. Far-UV CD spectra (a) Near-UV CD spectra (b), intrinsic Trp/Tyr fluorescence spectra (c), and ANS fluorescence spectra (d) of CA upon refolding in the presence of 50 mM TMAO (incubated overnight at 25 °C). Solid line, dashed line, and dotted line represents refolded native control, TMAO-induced state, and Us, respectively

TMAO-induced state is not kinetically dependent

We have further measured activity of TMAO-induced state after incubation at 3 different time intervals, 48, 72, and 96 h (Fig. 6a), and aggregation was checked by measuring light scattering intensity (Fig. 6b) and TEM analysis (Fig. 6c). It was observed that there was no activity at 16 h and even at longer incubation periods indicating that the TMAO-induced state is devoid of enzyme activity and kinetically independent. We also could not detect any high-order oligomers in TMAO-induced state incubated for 96 h, confirming that the loss of activity is not due to the formation of high-order oligomers.

Fig. 6.

Refolding behavior of CA in presence of TMAO incubated for longer time period. Percentage activity (a), Light scattering intensity at 400 nm at the indicated time frames (b), and Transmission electron micrographs of refolded CA incubated for 96 h in presence at 25 ˚C (c). R represents refolded control upon overnight incubation. The TMAO concentration used for all the experiments was 50 mM

TMAO affects the cis–trans isomerization of CA

We again performed refolding experiments of CA in the presence of the peptidyl-prolyl cis–trans isomerase (PPIase), cyclophilin (Fig. 4). Figure 4b shows a significant increase in CA activity upon addition of cyclophilin in a concentration-dependent manner. Interestingly at 11 µM, there was a gain in activity similar to the refolded control (in absence of TMAO). However, there was no further increase in the folded CA activity in presence of cyclophilin at different time intervals (Fig. S3). It is also seen in Fig. 4c that inhibition of cyclophilin activity by cyclosporin failed to produce active CA. These results supported the notion that TMAO affects the cis–trans proline isomerization of CA.

The inhibitory effect of TMAO is generally true for slow folding proteins

To further examine if the behavior of TMAO is confined to CA (a protein with the proline content of 7.3%), we investigated the effect of TMAO on two additional proteins with slow folding kinetics (HRP and α-CHT with 13 and 9 proline residues, respectively). First of all, we performed heat-induced denaturation of HRP (Fig. 7a) in the presence of two different TMAO concentrations. Although we could not induce complete thermal unfolding of this protein in the measurable temperature range, results revealed that there was a subtle shift of the transition curves in presence of TMAO toward the lower Tm values relative to control. We also observed a decrease in the functional activity of HRP in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 7b). In a similar manner to CA, refolded HRP also exhibits more reduction in the functional activity as compared to the native HRP. However, there was no complete loss of enzyme activity at the highest TMAO concentration (Fig. 7c). Further conformational studies revealed that the secondary structure (as indicated by far-UV CD measurement) and the tertiary structure (as indicated by near-UV and tryptophan fluorescence measurement) of native HRP were not altered due to TMAO (Fig. S4a–c). Therefore, these results on the TMAO’s effect on HRP were in agreement with those described for CA.

Fig. 7.

Effect of TMAO on the stability and folding behavior of HRP and α-CHT. Thermal melting curves (a HRP; d α-CHT), percent native enzyme activity (b HRP; e α-CHT) in presence of TMAO, and the magnitude of refolding (c HRP; f α-CHT) in the presence of the indicated TMAO concentrations. The transition curves in the case of HRP are incomplete at the measurable temperature range. R represents refolded control. Solid line and dashed line in Fig. 7a and d represent melting curves of the enzymes (HRP and α-CHT) in the absence and presence of 50 mM TMAO, respectively

We have further examined the effect of TMAO on α-CHT. Heat-induced denaturation studies (Fig. 7d) suggested that there was no significant difference in the Tm for the protein in the absence or presence of TMAO. Similar to CA, the α-CHT enzyme activity was not significantly affected by TMAO (Fig. 7e). However, TMAO-induced refolded α-CHT exhibited a reduction in its activity (although complete inhibition has not been observed) indicating that TMAO also affects the refolding step of α-CHT (Fig. 7f). TMAO has also been observed to have no significant change in the secondary (as revealed from the near-UV CD spectrum) and tertiary structure (as revealed from tryptophan fluorescence and near-UV CD spectra) of native α-CHT (Fig. S4d–f). Therefore, data obtained for the HRP and α-CHT provided further support to the premise that TMAO inhibits the folding of proline-rich proteins.

TMAO enhances level of unfolded/misfolded proteins in HeLa cells

To examine if the TMAO could induce protein unfolding in the cells, we treated HeLa cells with 3 different concentrations of TMAO and analyze the extent of protein unfolding by using ANS-binding assay. Percent increase in ANS fluorescence intensity has been calculated as shown in Fig. 8. It is seen in Fig. 8a, that TMAO treatment increases the binding of ANS dye by 7–22% (at 100–500 µM concentration) compared to the untreated extract. We also performed another experiment in which we added TMAO directly to the untreated protein extract and analyzed the level of unfolding using similar protocols (Fig. 8b). We observed similar pattern of percent increase in ANS fluorescence intensity. The results indicate that TMAO induces protein unfolding/misfolding at the cellular level.

Fig. 8.

Extent of protein misfolding in presence of TMAO in HeLa cells. Percentage increase in ANS binding to (a) the total protein extract obtained from TMAO-treated HeLa cells and (b) to total protein extract from untreated HeLa cells that was further treated with TMAO. The TMAO concentrations used were 100, 250 and 500 µM

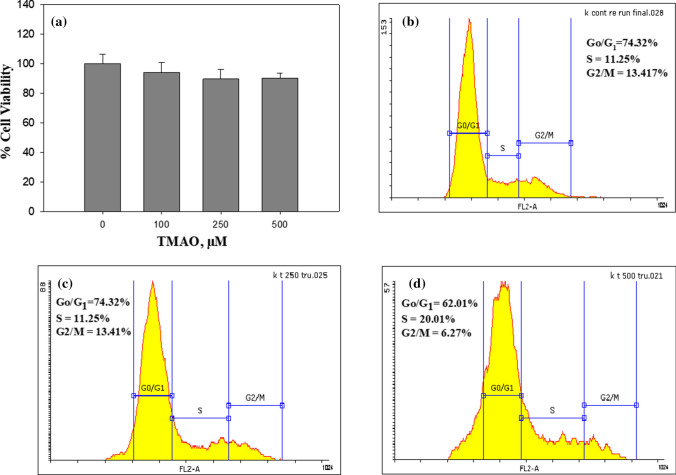

TMAO causes cell cycle arrest in HeLa cells

To investigate the effect of TMAO on HeLa cells, we first of all treated cells with different concentrations of TMAO and measured cell viability using MTT assay. It was observed that addition of TMAO results in 2–7% decrease in the viable cells (Fig. 9a). We have further analyzed the TMAO-treated cells for cell cycle phase distribution (Fig. 9b). It is seen that TMAO treatment resulted in the arrest of the cell cycle at the S phase as evident from the increased population of cells (from 11.25% to 20.01%) in this phase. The results indicate that TMAO affected the synthesis phase of the cell cycle progression.

Fig. 9.

Effects of TMAO on HeLa cells. Effect of TMAO on viability of HeLa cells (a); cell cycle phase distribution of untreated cells (b, upper right panel) and cells treated with 250 µM (c, lower left panel) and 500 µM (d, lower right panel) TMAO

Discussion

TMAO has been known to affect protein thermodynamic stability (ΔGDo) by their effects on the thermodynamic equilibrium, Native state ⇌ Denatured state, or by modulating the folding landscape via their effect on folding intermediates [32, 33]. Therefore, to investigate the effect of TMAO on CA, we carried out unfolding and refolding studies in presence of TMAO. Our results (Fig. 1a) indicated that TMAO did not largely affect the stability of the native CA, because of the absence of significant effect on the Cm and very small effect on ΔGDo of the protein (Table S1). In agreement, there was no significant effect on the functional activity of CA, except at 50 mM wherein there was around 10–20% loss in the enzyme function (see Fig. 1b). Interestingly, we observed a complete loss of enzyme activity upon refolding in presence of 50 mM TMAO, indicating that TMAO inhibits refolding of this protein (Fig. 1c). To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first report showing effect of TMAO on protein folding at sub-millimolar concentrations. Previously, it has been reported that TMAO under certain conditions exhibit preferential binding [34] or binds directly [35] to the native state of proteins leading to their destabilization or inactivation. Therefore, we investigated if TMAO binds to the native state of CA leading to the inhibition of its activity by conducting the Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) studies. Results shown in Fig. 10 confirmed that TMAO does not bind to CA. No change in the native state structure (Fig. 2) also supported this premise. Site-specific docking analysis further revealed that TMAO does not bind to the active site of CA (data not shown). No significant effect of TMAO on the native state, but a significant loss of the enzyme function upon refolding indicates that TMAO inhibits CA activity by affecting the folding pathway or folding landscape of this protein. We also observed that the effect was confined to TMAO, as no other molecules used in the study either inhibited refolding or alters native state of CA (Fig. S1 and S2).

Fig. 10.

Isothermal calorimetry analysis of TMAO binding to CA. Titration of CA showing response as successive injection of TMAO to reaction cell containing CA. The isothermal calorimetric enthalpy changes (upper panel) and resulting binding isotherms (lower panel)

We were further interested to investigate the mechanism of inhibition of CA folding by TMAO. In general, TMAO induces protein folding via its osmophobic effect (because of overwhelming unfavorable interactions with the peptide backbone) [36, 37] or due to the preferential hydration effect (because of the exclusive potential from the protein surface) [38]. The unusual effects of TMAO on CA folding indicated the minimal contribution of such forces to the folding behavior of this protein. To validate this argument, we calculated the free energy of CA required upon transfer of this protein from water to 50 mM TMAO solution (see Fig. 11). Since the total positive free energy (originated from the peptide backbone and amino-acid side chains) outweighs the negative contribution, the destabilization of CA by TMAO is not due to the osmophobic force. Furthermore, TMAO has also been reported to induce protein aggregation or oligomer formation resulting in loss of protein function upon folding/refolding [39–41]. Our results on TEM and light scattering measurements, however, revealed that there is no evidence for the presence of any aggregates (Fig. 3) under the same experimental conditions. Thus, osmophobic force or oligomerization is not the cause of the inhibition of CA refolding by TMAO.

Fig. 11.

Apparent transfer free energies of CA upon transfer from water to 50 mM TMAO solutions. Free energy contributions of the various amino-acid side change and backbone (DKP/2) exposed in the native CA upon transfer from water to 50 mM TMAO. The total (positive and negative) free energy has been calculated using the transfer free energy of the individual amino acids reported in Wang et al. (1997) [61]

Alternatively, TMAO could also influence the cis–trans isomerization steps thereby influencing the fast and slow folding species. CA contains 15 trans and 2 cis prolyl bonds and folds in a two-step process consisting of a slow, Us ⇌ Uf, and a fast, N ← Uf as shown in Eq. 1.

| 1 |

where Uf is the unfolded form with correct prolyl isomers as in the native state [31]. Us represents the denatured state containing incorrect (or randomly isomerized) prolyl isomers. As aforementioned, the two stages in refolding of this protein (the fast with the relaxation time t1/2 of ~ 120 s and the slow with the t1/2 of ~ 600 s) were attributed to the trans–cis isomerization of proline residues [27]. Here, the refolding stage with the half-time tl/2 of 120 s was attributed to a simultaneous transition of ten or more essential proline residues in trans isomer state, whereas the slow phase was explained by a simultaneous transition of two essential proline residues in cis isomer state [27]. Therefore, to examine for the possible effect of TMAO on the proline cis–trans isomerization, one can find conditions (that can populate Uf), at which the protein folding rate is much greater than the rate of spontaneous proline isomerization as the isomerization is a relatively slow process. As a result, immediately after fast unfolding under such conditions, all the essential proline residues will remain in their native isomeric states, and the protein will refold very quickly. On the other hand, as a result of prolonged incubation of the protein in its unfolded state (as seen in the case of Us), some of the proline residues may essentially remain in the incorrect isomeric state leading to the decrease in the number of protein molecules that can refold fast paralleled by the increase in the number of slow refolding protein molecules [27, 42–44].

Indeed, earlier studies have shown that two different collections of unfolded molecules (Uf and Us) could be produced in the presence of GdmCl upon varying the duration of unfolding. Uf is formed by a short 10-s unfolding pulse at 2 °C in the presence of GdmCl, whereas Us is generated upon a longer incubation of CA in presence of GdmCl at 20 °C [31]. Following a similar protocol, we generated Uf and investigated its behavior in presence of TMAO by measuring CA activity. Interestingly, we observed a nearly complete loss of CA activity at all TMAO concentrations (Fig. 4a) suggesting that TMAO inhibits CA folding by affecting the Uf state. We also confirmed that the loss of CA activity is not kinetically dependent, as no activity was restored after the prolonged incubation of the refolded CA in the presence of TMAO (Fig. 6). We have further characterized the conformation of the TMAO-induced folded state. It is evident from Fig. 5 that there is a significant difference in the secondary and tertiary structure of the refolded CA in presence of TMAO (Fig. 5a, b). It seems that there is retainment of some secondary structural components (Fig. 5a) and micro-environments of tyrosine/tryptophan residues are towards the more nonpolar side (Fig. 5c) in the TMAO-induced state (as λmax is blue-shifted as compared to Us). These conformational resemblances led us to believe that the disruption of Uf state by TMAO results in the formation of a structurally Us-like conformation (UTMAO). Perhaps TMAO binds to the Uf making the equilibrium, Uf ⇌ UTMAO shifts toward the right. We argue that the UTMAO may essentially contain few incorrect prolyl isomers. If this is the case, the addition of cyclophilin, an enzyme that catalyzes the incorrect prolyl isomers should offset the effect of TMAO. It is evident in Fig. 4b, that with an increase in cyclophilin concentration, there is a concomitant increase in the percent activity upon the refolding in presence of TMAO. Alternatively, when we inhibit the cyclophilin using cyclosporin, CA could not fold to its active functional state (Fig. 4c). Taken together, the results confirm that TMAO affects the Uf state by affecting prolyl cis–trans isomerization of CA making it a folding incompetent state.

To further investigate the generality of the effect of TMAO, we have further examined on two other slow folding proteins. It is evident in Fig. 7 that TMAO inhibits or hampers the proper folding of these proteins as well. Furthermore, there is also existence of reports on the functional or folding inhibition by TMAO on some proteins as shown in Table 1. It has been known that the number of proline residues in a polypeptide chain determines the nature of folding kinetics. In general proteins with low proline residues are of fast-folding types (as compared to proteins with slow folding kinetics) as there is a low probability of the proline residues to exist in the incorrect prolyl isomers. Therefore, we have intentionally examined the proline content of the TMAO-inhibited proteins. Interestingly, we observed that almost all proteins (shown in Table 1) are rich in proline content and therefore should represent slow folding types. Previously, solvent-dependent destabilization effect of TMAO has been reported on 3 fast-folding proteins [45]. It was also demonstrated that TMAO exhibits a stabilizing effect at physiological pH but becomes a folding inhibitor at pH below the pKa of TMAO (5.0). It is possible that in a similar manner (observed in this study) the acid-denatured state of these proteins contains structured micro-environments wherein incorrect cis–trans species endures but not in the denatured state at physiological pH. Taken together, the results let us to believe that TMAO inhibits folding of proline-rich (slow folding) proteins.

Table 1.

List of proteins inhibited by TMAO and their proline contents

| S. No | Protein | Proline content | Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Xanthine oxidase | 73 | Activity inhibitor | [60] |

| 2 | Catalase | 38 | Activity inhibitor | [60] |

| 3 | Pyruvate kinase | 22 | No change in enzyme activity | [61] |

| 4 | Α-casein | 17 | Activity inhibitor | [62] |

| 5 | Prions | 17 | Denaturant | [14] |

| 6 | CA | 17 | Folding inhibitor | This study |

| 7 | Aldose reductase | 16 | Activity inhibitor | [63] |

| 8 | Lactate dehydrogenase | 14 | Folding inhibitor | [64] |

| 9 | HRP | 13 | Activity inhibitor | This study |

| 10 | Argininosuccinate lyase | 12 | Activity enhancer | [60] |

| 11 | Stem bromelain | 11 | Destabilizer and activity inhibitor | [65] |

| 12 | Trypsin | 11 | Stabilizer | [66] |

| 13 | α-CHT | 9 | No change in enzyme activity | [67] |

| 14 | α-CHT | 9 | Activity inhibitor | This study |

In human, TMAO is derived from choline, carnitine, or betaine (rich in animal sources including eggs, pork, red meats, fishes etc.) by the action of gut microbiota and accumulate in the blood [46, 47]. It is further taken up by the cells and tissues with the help of organic cation transporter 2 (OCT2) [48]. If we have to translate our results in vivo or in cells, the presence of TMAO would cause protein misfolding (specifically in proteins having slow folding kinetics), which might eventually lead to the formation of toxic protein inclusions. A large accumulation of such unfolded or misfolded proteins in the ER may initiate unfolded protein response (UPR: a cellular response to recover from ER stress) [49]. Interestingly, our results on HeLa cells shown in Fig. 8, indicate that there is presence of more unfolded or misfolded protein species in presence of TMAO. We also observed that there is a decrease in the viability of cells (Fig. 9a) due to cell cycle arrest (with TMAO treatment) at S phase (Fig. 9b) indicating that TMAO might have induced aberrant protein misfolding. Most recently, it has also been demonstrated that TMAO activates the PERK arm of the UPR signaling pathway by directly binding to it (in hepatocytes) [50]. Indeed, PERK is also a proline-rich protein consisting of 67 proline residues. It might be possible that TMAO impaired folding of PERK and consequently, binding of this protein to GRP78.

Summary

We describe here that TMAO is a folding inhibitor for proteins having slow folding kinetics, by virtue of its effect on the cis–trans isomerization step. We also demonstrate that the inhibitory effect is not confined to purified proteins but also exhibits in the cells. Our results, therefore, hint that abnormal accumulation of TMAO could be a bottleneck for causing proteopathy or related diseases. Alternatively, varying TMAO levels, therefore, should be a promising strategy for the management and control of the disease severity. It is clear that further studies are needed to explore a new mode of folding and new folding landscape in the presence of TMAO.

Materials

Commercially available lyophilized preparations of Carbonic anhydrase (CA; Cat. No. C2624), Peroxidase (HRP; Cat. No. 77332), Alpha-Chymotrypsin (α-CHT; Cat no. C4129), and Cyclophilin D (Human-recombinant) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Company. 2,2’-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid), diammonium salt (ABTS), Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2; 30% v/v), 4-Nitrophenyl Acetate, N-Succinyl-Ala-Ala-Pro-Phe p nitroanilide (SAPNA), trimethyl N-oxide (TMAO), glycine, beta-alanine, proline, glycerol, myoinositol, sorbitol, betaine, taurine and 8-anilino-1-naphthalene sulfonic acid (ANS), penicillin, propidium iodide (PI), streptomycin, 3-(4,5- dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT), Dulbecco's minimal essential medium (DMEM), 2′,7′- dichlorofluorescein-diacetate (DCFH-DA), and ribonuclease A (RNase A) were also purchased from the Sigma. Ultra-pure samples of Urea and Guanidium Chloride (GdmCl) were obtained from MP Biomedicals. Cyclosporin A was procured from Cayman Chemicals.

Protein samples of CA, HRP, and α-CHT were dialyzed overnight against 0.1 M KCl (4 °C; pH 7.0) and protein stock solutions were filtered using 0.22 µM syringe filters. The concentration of all protein solutions was calculated using molar absorption coefficient, ε value of 57,000 M−1 cm−1 (at 280 nm) [51], 105,000 M−1 cm−1 (at 405 nm)[52] and 50,000 M−1 cm−1 (at 280 nm) [53] for CA, HRP, and α-CHT, respectively. The stock solution of ANS was also prepared using a molar extinction coefficient of 26,620 M−1 cm−1 at 416 nm. The concentration of Urea and GdmCl was determined from refractive index measurements using Refractometer.

All other chemicals were of analytical grade and hence used without further purification. All solutions for optical measurements were prepared in the degassed 0.05 M Phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) (except for those used for α-CHT studies where Tris HCl buffer was used) containing 0.1 M KCl, using Double-Distilled water as an aqueous phase.

Methods

Activity measurements of native enzyme

CA: To investigate the effect of osmoprotectants on the functional activity of CA, enzyme (0.0084 mg/ml) was titrated with different concentrations of osmoprotectants and incubated overnight at room temperature. Hydrolysis of 4-nitrophenyl acetate (0.1 mM) was monitored at 400 nm after incubation for 1 h at 25 °C using Jasco V-600 UV/ Vis spectrophotometer equipped with a Peltier-type temperature controller [54].

HRP: The enzymatic reaction progress of HRP was determined by the measurement of ABTS peroxidation[55]. HRP was incubated with the TMAO overnight. The HRP catalyzed degradation of H2O2 was measured spectrophotometrically (Jasco V-600 UV/Vis spectrophotometer) at 405 nm after incubation for 10 min (at 25 °C). The reaction mixture consisted of 0.5 μM of enzyme solution, 50 μM of ABTS, and 300 μM H2O2.

α-CHT: Enzyme activity was determined using 0.005 mg/ml SAPNA in 20 mM CaCl2, 50 mM Tris–HCl buffer, pH 7.0 as described previously by Louati et al. (2011) [56]. The formation of p-Nitroaniline was measured at 410 nm (20 °C) after 10 min using Jasco V-600 UV/Vis spectrophotometer.

Enzyme activity results were expressed as percent, considering untreated protein activity as 100%.

Refolding of enzymes

All enzymes were, first of all, denatured using GdmCl and incubated overnight. We use 4.0 M for CA and α-CHT, and 8.0 M in the case of HRP. Refolding of GdmCl-induced denatured enzymes was carried out by diluting denatured enzymes to a ratio of around 1:300 using phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) in the presence and absence of osmoprotectants and kept overnight for equilibration. For the generation of the Uf state, denaturation was carried out for only for 10 s (in ice) as described by Kern et al. (1995)[31] (instead of overnight denaturation). Activities of the refolded enzymes were then measured using the protocols described in the previous section.

Effect of cyclophilin and cyclosporin A on the refolding of CA

Refolding of GdmCl-denatured CA samples were carried out in the presence of a combined mixture of TMAO (1 mM) and varying cyclophilin concentrations (i.e., 1 µM, 3 µM, 6 µM, and 11 µM). The samples were incubated for 1 h and the magnitude of refolding was analyzed by measuring the enzyme activity of CA. To investigate the effect of cyclosporin, we added 5 µM of cyclosporin in the reaction mixture and follow similar protocols of refolding and activity measurements.

Protein stability studies

Urea-induced denaturation measurements

Urea-induced denaturation of carbonic anhydrase in the presence and absence of TMAO was followed by measuring changes in the relative fluorescence (305 nm) as a function of urea concentration at 25 °C. It should be noted that each solution (CA + urea) was kept for adequate time to allow equilibration for denaturation by urea. The optical transition data were converted into ∆GD the Gibbs energy change using the relation,

| 2 |

where y is the observed optical property and yN and yD are, respectively, the properties of the native and denatured protein molecules under the same experimental condition in which y has been determined. ∆GD was plotted against [urea], the molar concentration of the denaturant and a linear least-squares analysis was used to fit the (∆GD [urea]) data to the relation,

| 3 |

where is the value of ∆GD at 0 mM denaturant, and md gives the linear dependence of ∆GD on the [urea].

Thermal-induced denaturation measurements

Thermal denaturation studies of native HRP and α-CHT (concentration used was 0.4 mg/ml) in the absence and presence of TMAO were carried out by measuring changes at [θ]222 as a function of temperature (from 20 to 85 °C) in J-810 (Jasco spectropolarimeter) equipped with a Peltier-type temperature controller (Jasco PTC-424S) at a heating rate of 1 °C/min. This scan rate was found to provide adequate time for equilibration. Reversibility was measured by comparing the optical property of the native protein before denaturation and protein after a round of denaturation (by cooling down the sample) and was found to be identical. Solution blanks showed no significant change in ellipticity upon temperature increase, hence neglected during the data analysis. Each heat-induced transition curve was analyzed for Tm (the midpoint of heat denaturation) and ∆Hm (the enthalpy change of denaturation at Tm) using a non-linear least-squares analysis equation,

| 4 |

where y(T) is the optical property at temperature T (Kelvin); yN(T) and yD(T) are the optical properties of the native and the denatured protein molecules, respectively; and R is the gas constant. In the analysis of the transition curve, it was assumed that a parabolic function describes the dependence of the optical properties of native and denatured protein molecules i.e., yN(T) = aN + bNT + cNT2, and yD(T) = aD + bDT + cDT2, where aN, bN, cN, aD, bD, and cD are temperature-independent coefficients [57].

Circular dichroism (CD) measurements

Far- and near-UV (CD) spectra of native, denatured (GdmCl-induced) and refolded enzymes were measured in the presence and absence of different concentrations of TMAO in a J-810 Jasco spectropolarimeter (equipped with a Peltier-type temperature controller)[58]. Each spectrum of the protein was corrected for the contribution of its blank from the entire wavelength range. The concentration of the protein used was 0.3 mg/ml for HRP and 0.4 mg/ml for both CA and α-CHT at pH 7.0, 25 °C). The path length of the cuvette used for far- and near-UV CD measurements was 1.0 mm and 10 mm respectively.

Fluorescence measurements

Fluorescence emission spectra measurements of native, denatured and refolded enzymes in the absence and presence of TMAO were carried out in Perkin Elmer- LS 55 (Fluorescence spectrometer). The final concentration of the proteins used was 2 µM for CA and HRP and 3 µM for α-CHT. The path length of the cuvette used was 3 mm. The excitation wavelength used was 280 nm for Carbonic anhydrase and 295 nm for both HRP and α-CHT. All solution blanks were normalized and corrected for all spectral measurements.

ANS-binding fluorescence measurements of native and refolded enzymes were recorded from 400 to 600 nm using an excitation wavelength of 360 nm. The concentration of ANS taken was 16-fold that of the protein concentration at 360 nm. All necessary background corrections were made.

In the case of total protein extracts obtained from HeLa cells, 14.08 µg/ml of total protein was treated with 16-fold ANS and a similar protocol was followed to measure the extent of unfolding/misfolding.

Light scattering measurements

Dynamic light scattering measurements will be carried out in a Malvern Zetasizer MicroV to obtain hydrodynamic radii of both the native states and modified proteins at 25 ± 0.1 °C. The protein samples will be filtered through a 0.22 µ filter and 50 µl (2 mg/mL) proteins will be used. Measurements will be made at a fixed angle of 90° using an incident laser beam of 689 nm. Ten measurements will be made with an acquisition time of 30 s for each sample at a sensitivity of 10%. The data will be analyzed to get hydrodynamic radii and polydispersity which is a measure of the standard deviation of the size of the particle.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Transmission electron micrographs were recorded on FEI Tecnai G2-200 kV HRTA transmission electron microscopy (Netherland) (equipped with digital imaging) facility available at AIIMS, New Delhi. Protein solution upon treatment with 1 mM TMAO was incubated for different time intervals and a droplet was placed and kept for drying on a copper grid for 5 min (at RT). Negative staining was done by adding 1% uranyl acetate solution onto the copper grid before drying the sample and digital images were visualized and saved.

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) measurements

ITC measurements were performed using VP ITC Calorimeter (MicroCal, Northampton, MA) available at CIRBS, JMI, Delhi. For measurement, the calorimeter cell containing a protein solution at a concentration of 20 µM was titrated with 10 µl of 400 µM TMAO (already loaded into the syringe), which was injected every 260 s into the protein cell. TMAO suspended in the buffer was used as a control. All the measurements were taken at 25 °C at a pH of 7.0. The data were evaluated by MicroCal origin ITC software. The data were normalized using the different sequential models to generate the stoichiometry (N), binding enthalpy (ΔH), and the association constant (Ka). Gibbs free energy changes (ΔG) can be measured using the relation:

| 5 |

where R is the gas constant and T is the absolute temperature.

Docking studies

Docking studies were performed with the help of crystal structures of human carbonic anhydrase (PDB ID: 3D92; obtained from RCSB PDB) and TMAO (drawn with discovery studio) by the CDOCKER protocol under the protein–ligand interaction section in Discovery Studio (DS) 4.0. Protein and Ligand molecules were prepared by the previously described method [59]. Substrate binding site (SBD site) was defined using the natural substrate (CO2) of the protein. Resulted conformers were ranked according to their CDOCKER (A CHARMm-Based MD Docking Algorithm) energy score.

Cell lines and maintenance of cell culture

HeLa cells were grown in cell culture flasks containing DMEM growth media supplemented with 100 units/mL of penicillin, 100 μg/mL of streptomycin, and 10% fetal bovine serum. The cells were maintained in a CO2 incubator (New Brunswick, Galaxy 170R, Eppendorf) at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and relative humidity of about 98%.

Cell viability assay

To evaluate the effect of TMAO on cell proliferation, an MTT assay was performed. HeLa cells (5 × 104cells/ml) were seeded onto a 96 well plate and incubated for 24 h. Seeded cells were treated with different concentrations of TMAO for 24 h and 20 µl of MTT reagent (5 mg/ml) was added. After incubation for 2 h at 37 °C, media were discarded from each well and 50 μl of DMSO was added to dissolve the formazan crystals. After incubation for 10 min, at 37 °C, absorbance was measured at 570 nm using an Elisa Plate reader (Biotech, USA).

Cell cycle phase distribution analysis

HeLa cells (1 × 106 cell/ml) were seeded in a 12-well plate containing DMEM media and incubated for 24 h for attachment. The attached cells were treated with 50 mM TMAO for 24 h. Following treatment, cells were trypsinized and centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 5 min. Thereafter, cells were resuspended in 300 µl of PBS-EDTA and 0.7 ml 70% ethanol was added and incubation was done for 45 min at 4 °C. After this, 20 mg/ml of RNase (1:100 v/v) was added and cells were kept for 30 min at room temperature. 50 µg/ml PI dye was added and allowed to bound for 20 min in dark. Harvested cells were analyzed for cell cycle phase distribution using flow cytometry.

Protein extraction from HeLa cells

HeLa cells (1 × 106 cell/ml) were seeded in a 12-well plate containing DMEM media and incubated for 24 h for attachment. The attached cells were treated with 10 Mm, 20 Mm, and 50 mM TMAO for 24 h. Following treatment, cells were trypsinized and centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 5 min. Cell pellets were washed with PBS buffer at least 2 times and Pellet was redissolved in Rapid cell mammalian buffer for 1 h and centrifuged at 10,000 g for 20 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected and the concentration of total protein was estimated using the Bradford method.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 Effect of various osmoprotectants on the functional activity of CA. Percent enzyme activity of native CA in the presence of multiple osmoprotectants as indicated in the figure (TIF 78 KB)

Supplementary file2 Effect of various osmoprotectants on the refolding behavior of CA. Percent enzyme activity of CA upon refolding in the presence of multiple osmoprotectants as indicated in the figure. R represents refolded control upon overnight incubation (TIF 97 KB)

Supplementary file3 Effect of cyclophilin and TMAO on the refolding of CA at extended time intervals: Percentage enzyme activity of TMAO-induced refolded CA at 3 different time intervals in presence of 11µM Cyclophilin. T represents refolded control in presence of TMAO upon overnight incubation, respectively (TIF 18 KB)

Supplementary file4 Conformational status of native HRP and α-CHT in presence TMAO: Far-UV CD spectra (a, HRP; d, α-CHT), near-UV CD spectra (b, HRP; e, α-CHT), and intrinsic fluorescence spectra (c, HRP; f, α-CHT) in the presence of 50mM TMAO. Solid line and dashed line represent CA in the absence and presence of 50mM TMAO, respectively (TIF 95 KB)

Supplementary file5 Thermodynamic parameters of CA in the presence of TMAO. Values of Cm and ΔGDo of CA in the presence of TMAO obtained at the indicated concentrations (DOCX 13 KB)

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by grants provided by DST PURSE and MG Grant to L.R.S and CSIR (09/045(1619)/2019-EMR-I) and 09/045(1359)/2015-EMR-I to K.K and A.K.B, respectively.

Author contributions

LRS helped in the conceptualization of data. KK, MW, and AKB collected the data. VNU and TAD contributed to data analysis. LRS and KK wrote the manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Anfinsen CB. Principles that govern the folding of protein chains. Science (80-) 1973;181:223–230. doi: 10.1126/science.181.4096.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soto C, Pritzkow S. Protein misfolding, aggregation, and conformational strains in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Neurosci. 2018;21:1332–1340. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0235-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashraf G, Greig N, Khan T, et al. Protein misfolding and aggregation in Alzheimer’s disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus. CNS Neurol Disord-Drug Targets. 2014;13:1280–1293. doi: 10.2174/1871527313666140917095514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: Progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science (80-) 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haass C, Selkoe DJ. Soluble protein oligomers in neurodegeneration: lessons from the Alzheimer’s amyloid β-peptide. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:101–112. doi: 10.1038/nrm2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breydo L, Wu JW, Uversky VN. α-Synuclein misfolding and Parkinson’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta-Mol Basis Dis. 2012;1822:261–285. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mehra S, Sahay S, Maji SK. α-Synuclein misfolding and aggregation: implications in Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta-Proteins Proteomics. 2019;1867:890–908. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2019.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muchowski PJ, Wacker JL. Modulation of neurodegeneration by molecular chaperones. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:11–22. doi: 10.1038/nrn1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hofmann C, Katus HA, Doroudgar S. Protein misfolding in cardiac disease. Circulation. 2019;139:2085–2088. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.037417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henning RH, Brundel BJJM. Proteostasis in cardiac health and disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017 doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2017.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Westermark P, Wernstedt C, Wilander E, et al. Amyloid fibrils in human insulinoma and islets of Langerhans of the diabetic cat are derived from a neuropeptide-like protein also present in normal islet cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:3881–3885. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.11.3881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tomaru U, Takahashi S, Ishizu A, et al. Decreased proteasomal activity causes age-related phenotypes and promotes the development of metabolic abnormalities. Am J Pathol. 2012;180:963–972. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin TY, Timasheff SN. why do some organisms use a urea-methylamine mixture as osmolyte? Thermodynamic compensation of urea and trimethylamine N-oxide interactions with protein. Biochemistry. 1994;33:12695–12701. doi: 10.1021/bi00208a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Granata V, Palladino P, Tizzano B, et al. The effect of the osmolyte trimethylamine N-oxide on the stability of the prion protein at low pH. Biopolymers. 2006;82:234–240. doi: 10.1002/bip.20481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Velasquez MT, Ramezani A, Manal A, Raj DS. Trimethylamine N-oxide: the good, the bad and the unknown. Toxins (Basel) 2016 doi: 10.3390/toxins8110326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Del RD, Zimetti F, Caffarra P, et al. The gut microbial metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide is present in human cerebrospinal fluid. Nutrients. 2017 doi: 10.3390/NU9101053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Z, Klipfell E, Bennett BJ, et al. Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature. 2011;472:57–65. doi: 10.1038/nature09922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang WW, Wang Z, Levison BS, et al. Intestinal microbial metabolism of phosphatidylcholine and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1575–1584. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109400.Intestinal. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li XS, Obeid S, Klingenberg R, Gencer B, Mach F, Räber L, Windecker S, Rodondi N, Nanchen D, Muller O, Miranda MX, Matter CM, Wu Y, Li L, Wang Z, Alamri HS, Gogonea V, Chung Y, Tang WHW, Hazen SL, Lüscher T. Gut microbiota-dependent trimethylamine N-oxide in acute coronary syndromes: a prognostic marker for incident cardiovascular events beyond traditional risk factors. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(814):824. doi: 10.1093/EURHEARTJ/EHW582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suzuki T, Heaney LM, Jones DJL, Ng LL. Trimethylamine N-oxide and risk stratification after acute myocardial infarction. Clin Chem. 2017;63(420):428. doi: 10.1373/CLINCHEM.2016.264853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fu Q, Zhao M, Wang D, et al. Coronary plaque characterization assessed by optical coherence tomography and plasma trimethylamine-N-oxide levels in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2016;118:1311–1315. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tan Y, Sheng Z, Zhou P, Liu C, Zhao H, Song L, Li J, Zhou J, Chen Y, Wang L, Qian H (2019) Plasma trimethylamine N-oxide as a novel biomarker for plaque rupture in patients with ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.118.007281 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Vogt NM, Romano KA, Darst BF, et al. The gut microbiota-derived metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide is elevated in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Res Ther. 2018;10:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s13195-018-0451-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li D, Ke Y, Zhan R, et al. Trimethylamine-N-oxide promotes brain aging and cognitive impairment in mice. Aging Cell. 2018;17:1–13. doi: 10.1111/acel.12768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pelletier CC, Croyal M, Ene L, et al. Elevation of trimethylamine-N-oxide in chronic kidney disease: contribution of decreased glomerular filtration rate. Toxins (Basel) 2019;11:635. doi: 10.3390/TOXINS11110635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bae S, Ulrich CM, Neuhouser ML, et al. Plasma choline metabolites and colorectal cancer risk in the women’s health initiative observational study. Cancer Res. 2014;74:7442–7452. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gv S, Vn U, Iv S, et al. Two slow stages in refolding of bovine carbonic anhydrase B are due to proline isomerization. J Mol Biol. 1990;213:561–568. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80215-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jamal S, Poddar NK, Singh LR, et al. Relationship between functional activity and protein stability in the presence of all classes of stabilizing osmolytes. FEBS J. 2009;276:6024–6032. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stryer L. The interaction of a naphthalene dye with apomyoglobin and apohemoglobin. A fluorescent probe of non-polar binding sites. J Mol Biol. 1965;13:482–495. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(65)80111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Semisotnov GV, Rodionova NA, Razgulyaev OI, Uversky VN, Gripas' AF, Gilmanshin RI. Study of the “molten globule” intermediate state in protein folding by a hydrophobic fluorescent probe. Biopolymers. 1991;31:119–128. doi: 10.1002/BIP.360310111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kern G, Kern D, Schmid FX, Fischer G. A kinetic analysis of the folding of human carbonic anhydrase II and its catalysis by cyclophilin. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:740–745. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.2.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Auton M, Rösgen J, Sinev M, et al. Biophysical chemistry. NIH Public Access; 2011. Osmolyte effects on protein stability and solubility: a balancing act between backbone and side-chains; pp. 90–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sharma GS, Dar TA, Singh LR. Reshaping the protein folding pathway by osmolyte via its effects on the folding intermediates. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2015;16:513–520. doi: 10.2174/1389203716666150623104330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Timasheff SN. Protein hydration, thermodynamic binding, and preferential hydration. Biochemistry. 2002;41:13473–13482. doi: 10.1021/bi020316e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liao Y-TT, Manson AC, DeLyser MR, et al. Trimethylamine N -oxide stabilizes proteins via a distinct mechanism compared with betaine and glycine. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2017;114:2479–2484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1614609114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bolen DW, Baskakov IV. The osmophobic effect: natural selection of a thermodynamic force in protein folding. J Mol Biol. 2001;310:955–963. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Auton M, Bolen DW. Prediction the energetics of osmolyte-induced protein folding/unfolding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15065–15068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507053102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Timasheff SN. Protein-solvent preferential interactions, protein hydration, and the modulation of biochemical reactions by solvent components. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:9721–9726. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122225399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gong B, Zhang L-Y, Pang C-P, Lam DS-C, Yam GS-F. Trimethylamine N-oxide alleviates the severe aggregation and ER stress caused by G98R αA-crystallin. Mol Vis. 2009;15:2829–2840. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang DS, Yip CM, Huang THJ, et al. Manipulating the amyloid-β aggregation pathway with chemical chaperones. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:32970–32974. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.46.32970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Uversky VN, Li J, Fink AL. Trimethylamine-N-oxide-induced folding of α-synuclein. FEBS Lett. 2001;509:31–35. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)03121-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brandts JF, Halvorson HR, Brennan M. Consideration of the possibility that the slow step in protein denaturation reactions is due to cis-trans isomerism of proline residues. Biochemistry. 1975;14(4953):4963. doi: 10.1021/BI00693A026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim PS, Baldwin RL. Specific intermediates in the folding reactions of small proteins and the mechanism of protein folding. Annu Rev Biochem. 1982;51(459):489. doi: 10.1146/ANNUREV.BI.51.070182.002331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McPhie P. Swine pepsinogen folding intermediates are highly structured, motile molecules. Biochemistry. 1982;21(22):5509–5515. doi: 10.1021/BI00265A020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Singh R, Haque I, Ahmad F. Counteracting osmolyte trimethylamine N-oxide destabilizes proteins at pH below its pKa: measurements of thermodynamic parameters of proteins in the presence and absence of trimethylamine N-oxide. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:11035–11042. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410716200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cho CE, Caudill MA. Trimethylamine-N-oxide: friend, foe, or simply caught in the cross-fire? Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2017;28:121–130. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koeth R, Levison B, Culley M, Buffa JA, Wang Z, Gregory JC, Org E, Wu Y, Li L, Smith JD, Tang WHW, DiDonato JA, Lusis AJ, Hazen SL. γ-Butyrobetaine is a proatherogenic intermediate in gut microbial metabolism of L-carnitine to TMAO. Cell Metab. 2014;20(5):799–812. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Teft WA, Morse BL, Leake BF, et al. Identification and characterization of trimethylamine-N-oxide uptake and efflux transporters. Mol Pharm. 2017;14:310–318. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.6b00937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang M, Kaufman RJ. Protein misfolding in the endoplasmic reticulum as a conduit to human disease. Nature. 2016;529:326–335. doi: 10.1038/nature17041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen S, Henderson A, Petriello MC, et al. Trimethylamine N-oxide binds and activates PERK to promote metabolic dysfunction. Cell Metab. 2019;30:1141–1151.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yazdanparast R, Khodarahmi R, Soori E. Comparative studies of the artificial chaperone-assisted refolding of thermally denatured bovine carbonic anhydrase using different capturing ionic detergents and β-cyclodextrin. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005;437:178–185. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Veitch NC, Williams RJP. Two-dimensional 1H-NMR studies of horseradish peroxidase C and its interaction with indole-3-propionic acid. Eur J Biochem. 1990;189:351–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Akram M, Lal H, Shakya S, Kabir-Ud-Din Multispectroscopic and computational analysis insight into the interaction of cationic diester-bonded gemini surfactants with serine protease α-chymotrypsin. ACS Omega. 2020;5:3624–3637. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.9b04142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Uda NR, Seibert V, Stenner-Liewen F, et al. Esterase activity of carbonic anhydrases serves as surrogate for selecting antibodies blocking hydratase activity. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2015;30:955–960. doi: 10.3109/14756366.2014.1001754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Childs RE, Bardsley WG. The steady state kinetics of peroxidase with 2,2’ azino di (3 ethylbenzthiazoline 6 sulphonic acid) as chromogen. Biochem J. 1975;145:93–103. doi: 10.1042/bj1450093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Louati H, Zouari N, Miled N, Gargouri Y. A new chymotrypsin-like serine protease involved in dietary protein digestion in a primitive animal, Scorpio maurus: purification and biochemical characterization. Lipids Health Dis. 2011;10:121. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-10-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sinha A, Yadav S, Ahmad R, Ahmad F. A possible origin of differences between calorimetric and equilibrium estimates of stability parameters of proteins. Biochem J. 2000;345:711–717. doi: 10.1042/bj3450711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang YW, Teng CC. Circular dichroism and fluorescence studies of polyomavirus major capsid protein VP1. J Protein Chem. 1998;17:61–71. doi: 10.1023/A:1022542631609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gugulothu B, Pasham S, Mahankali V, et al. Insights from the molecular docking analysis of phytohormone reveal brassinolide interaction with HSC70 from Pennisetum glaucum. Bioinformation. 2019;15:131–138. doi: 10.6026/97320630015131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mashino T, Fridovich I. Effects of urea and trimethylamine-N-oxide on enzyme activity and stability. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1987;258:356–360. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(87)90355-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grundy JE, Storey KB. Urea and salt effects on enzymes from estivating and non-estivating amphibians. Mol Cell Biochem. 1994;131:9–17. doi: 10.1007/BF01075719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bhat MY, Singh LR, Dar TA, et al. Trimethylamine N-oxide abolishes the chaperone activity of α-casein: an intrinsically disordered protein. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06836-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Burg MB, Peters EM. Urea and methylamines have similar effects on aldose reductase activity. Am J Physiol-Ren Physiol. 1997 doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1997.273.6.f1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chilson OP, Chilson AE. Perturbation of folding and reassociation of lactate dehydrogenase by proline and trimethylamine oxide. Eur J Biochem. 2003;270:4823–4834. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rani A, Jayaraj A, Jayaram B, Pannuru V. Trimethylamine-N-oxide switches from stabilizing nature: a mechanistic outlook through experimental techniques and molecular dynamics simulation. Sci Rep. 2016;6:1–14. doi: 10.1038/srep23656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Levy-Sakin M, Berger O, Feibish N, et al. The influence of chemical chaperones on enzymatic activity under thermal and chemical stresses: common features and variation among diverse chemical families. PLoS One. 2014 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kumar R, Serrette JM, Thompson EB. Osmolyte-induced folding enhances tryptic enzyme activity. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005;436:78–82. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary file1 Effect of various osmoprotectants on the functional activity of CA. Percent enzyme activity of native CA in the presence of multiple osmoprotectants as indicated in the figure (TIF 78 KB)

Supplementary file2 Effect of various osmoprotectants on the refolding behavior of CA. Percent enzyme activity of CA upon refolding in the presence of multiple osmoprotectants as indicated in the figure. R represents refolded control upon overnight incubation (TIF 97 KB)

Supplementary file3 Effect of cyclophilin and TMAO on the refolding of CA at extended time intervals: Percentage enzyme activity of TMAO-induced refolded CA at 3 different time intervals in presence of 11µM Cyclophilin. T represents refolded control in presence of TMAO upon overnight incubation, respectively (TIF 18 KB)

Supplementary file4 Conformational status of native HRP and α-CHT in presence TMAO: Far-UV CD spectra (a, HRP; d, α-CHT), near-UV CD spectra (b, HRP; e, α-CHT), and intrinsic fluorescence spectra (c, HRP; f, α-CHT) in the presence of 50mM TMAO. Solid line and dashed line represent CA in the absence and presence of 50mM TMAO, respectively (TIF 95 KB)

Supplementary file5 Thermodynamic parameters of CA in the presence of TMAO. Values of Cm and ΔGDo of CA in the presence of TMAO obtained at the indicated concentrations (DOCX 13 KB)

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.