Abstract

Epidermal resident γδ T cells, or dendritic epidermal T cells (DETCs) in mice, are a unique and conserved population of γδ T cells enriched in the epidermis, where they serve as the regulators of immune responses and sense skin injury. Despite the great advances in the understanding of the development, homeostasis, and function of DETCs in the past decades, the origin and the underlying molecular mechanisms remain elusive. Here, we reviewed the recent research progress on DETCs, including their origin and homeostasis in the skin, especially at transcriptional and epigenetic levels, and discuss the involvement of DETCs in skin diseases.

Keywords: Dendritic epidermal T cells (DETCs), γδ T cells, Development, Function, Skin diseases

Introduction

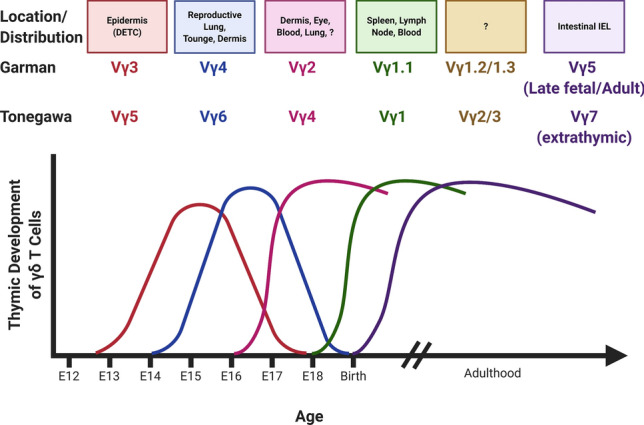

γδ T cells are a unique and conserved population of T cells bearing the γ and δ chains of T cell receptor (TCR) [1–3]. They recognize stress-induced self-antigen in an MHC-independent manner and have restricted antigenic specificity. The conventional αβ T cells primarily reside in secondary lymphoid organs, whereas γδ T cells preferentially reside in epithelial tissues, such as the skin, reproductive tract, respiratory tract, and intestines, where they function as the first line of defense. The distinct γδ T cell populations that associate with variable Vγ segment usage appear in successive waves [4]. The subsets that emerge earlier are restricted to develop in the embryonic thymus and exported to the periphery where they self-renew in epithelial tissue, while the majority of subsets that develop later are replenished from the thymus throughout life and circulate in the blood and secondary lymphoid organs [5–7]. It is important to note the two different murine γδ nomenclatures [8, 9], Garman and Tonegawa, as shown in Fig. 1. Going forward, we will use the Garman nomenclature.

Fig. 1.

Successive waves of γδ T cell production occur over development. Two nomenclatures exist for describing these cells—Garman and Tonegawa. Made with Biorender

Thymic Vγ3+ γδ T cells, the precursor of dendritic epidermal T cells (DETCs), are ontogenetically the first T cells generated during mouse development. DETCs are intraepithelial γδ T cells that express invariant TCR with the Vγ3Vδ1 rearrangement, a restricted antigen repertoire and act exclusively as resident T cells in the murine epidermis. Whereas an exact homolog to murine DETCs has not been identified in humans, Vδ1 T cells reside in both the epidermis and dermis of human skin [10–13]. DETCs produce a wide range of cytokines that orchestrate immune responses and are implicated in infection, cancer, wound healing, and autoimmune diseases in skin. Despite recent advances in the understanding of DETC development and function, the detailed molecular mechanisms remain unknown. This review highlights transcription factors and regulators of DETC embryonic development and function. In addition, we review their function in murine models of contact allergy, atopic dermatitis (AD), wound healing, cutaneous cancer and microbial infection.

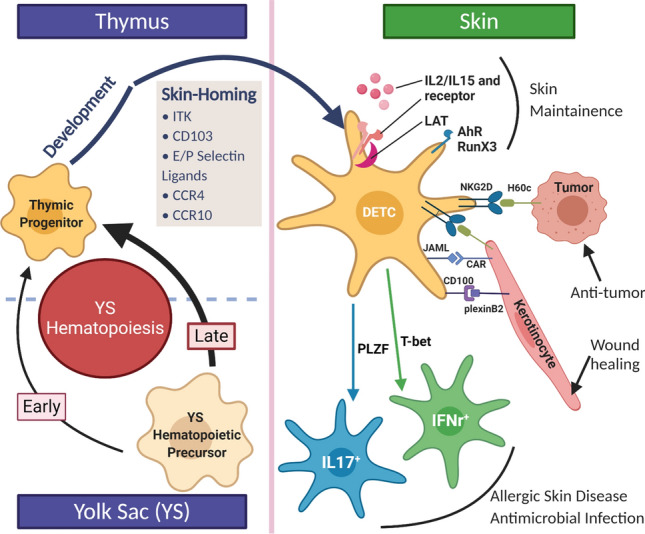

Origin of DETCs from the yolk sac

It was originally hypothesized that DETCs, like other lymphoid progenitors, develop from fetal liver precursors, which then seed the thymus and subsequently migrate to the epidermis [14, 15]. While the exact DETC precursor has not yet been identified, recent studies have shown that DETCs are derived from early and late yolk sac (YS) hematopoietic precursors. Specifically, using tamoxifen-inducible CDh5CreERT2+/wtRosatdt/wt and Runx1CreERT2/wtRosayfp/wt mice, DETC progenitors appear to rise mostly from late YS hematopoiesis (E8.5) and partly from early YS hematopoiesis (E7.5), but no contribution from definitive hematopoiesis (E10.5) was found in this study [16]. Thus, pre-thymic development of DETCs is more akin to Langerhans cells than conventional αβ-T cells. These YS progenitors then populate the thymus, where they mature. Mature DETCs subsequently migrate to the fetal epidermis between E16 and E18 [13]. DETCs are identified in the epidermis by their dendritic morphology and expression of invariant Vγ3Vδ1+TCR without junctional diversity. As stated earlier, cells with these characteristics have not been identified in human skin. These cells develop exclusively from progenitors in the fetal thymus and self-renew in the skin throughout the lifetime in mice [17–20] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Schematic of origin and function of DETCs highlighting key genes, in skin migration, development and maintenance in the epidermis. Made with Biorender

Thymic development of DETCs

A characteristic of γδ T cells is that subset-specific recombination of Vγ/Vδ TCRs is required for distribution in distinct epithelial sites. DETCs normally express the Vγ3/Vδ1 TCR. In TCR-δ−/− mice expressing a Vδ6.3–Dδ1–Dδ2–Jδ1–Cδ transgene, DETCs did not colonize the skin. Yet, DETCs were found in the skin of wildtype mice expressing the same transgene, suggesting endogenous TCR-δ expression was required for skin migration of putative DETCs. Interestingly, a high proportion of these DETCs in wildtype mice expressed Vγ3/Vδ6.3 and PCR identified concomitant expression of Vδ1 suggesting that both TCRs were expressed, and the expression of Vδ1 is necessary for skin migration [21]. Other studies showed targeted disruption of the Vδ gene results in a markedly impaired development of Vγ3+ fetal thymocytes [22]. Interestingly, DETC development was intact in Vγ3-knockout mice [23], whereas DETC development is absolutely dependent on TCRγ genes within the Cγ1 cluster [24, 25]. These findings demonstrate that TCR specificity is critical for the embryonic development of DETCs.

In addition to ordered rearrangement of TCR-γ and δ genes contributing to DETC development in the thymus, it has long been thought that TCR signaling also plays a role. Previous studies showed that knocking-out components of the TCR signaling complex, such as Lck, Syk, ZAP-70, as well as ERK–Egr–Id3 axis, impaired DETC development [26–30]. However, the role of the TCR–ligand interaction in this selection remains poorly studied. Others have suggested that NF-κB signaling is indirectly required for Vγ3+ thymocytes and DETC differentiation and maturation. RankL and RelB, components of the NF-κB signaling pathway, promote the development and maturation of Aire+ medullary thymic epithelial cells (mTECs) leading to Skint-1 expression—the latter of which is required for DETC development by binding to Vγ3TCR [31–33]. Additionally, expression of NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK) and downstream molecules of the NF-κB family members are required in mTECs during the development of Vγ3+ γδ T cell precursors in the embryonic thymus and DETCs in the epidermis, which are lost in Map3k14−/− (encoding gene of NIK) mice and NIK-deficient adult mice [34].

Evidenced by Janus Kinase(JAK)-3/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)-5-deficient mice, Vγ3+ thymocytes depend on IL-7R signaling for fetal thymic precursor and adult DETC development [35–38]. RunX3, one of three proteins comprising the RUNT domain family of transcription factors RUNX, is highly expressed in the thymus and plays an important role in cellular differentiation and proliferation. RunX3 is essential for DETC development and migration as RunX3−/− mice completely lack DETCs in the epidermis. Notably, RunX3−/− mice also lack epidermal LCs, highlighting another similarity in the development of these resident epidermal cell types. Studies have shown RunX3 regulates the expression of CD103 and CD122 [39]. CD103 (discussed below) is necessary for skin-homing, whereas CD122 (also called IL-2Rβ) is required for IL-2- and IL-15-mediated Vγ3+ thymocyte proliferation, development and survival. Thus, RunX3 is a critical transcription factor in multiple steps of DETC development, including thymic development.

Moreover, we have recently shown miRNAs are necessary for thymic development of Vγ3+ γδ T cells. DETCs accumulate in the thymus of Csf1rCre+Dicer−/− mice and have impaired survival and maturation, through downregulated CD122 and CD45RB expression. This accumulation occurred despite marked upregulation of skin-homing markers, CCR10 and S1P1, suggesting the defect was in maturation [40]. Taken together, these studies highlight the complexity of DETC thymic development, which includes successful TCR recombination and TCR signaling; sufficient support from thymic stroma; the ability to respond to growth factors; and expression of transcription factors that orchestrate a number of cellular processes important in γδ T cells and DETC development in the thymus.

Genes involved in DETC skin-homing

ITK

The Tec family nonreceptor tyrosine kinase IL-2-inducible T cell kinase (ITK) is a key signaling mediator downstream of the TCR [41], and is involved in regulating the homeostasis of T cell populations including DETCs. Interestingly, ITK deficiency does not affect Vγ3+ γδ T cell precursor development or their positive selection and maturation processes in the fetal thymus. However, it interrupts thymic egress and skin-homing of Vγ3+ γδ T cell precursors by abrogating CCR10 and S1PR1 expression, resulting in impaired seeding in the fetal skin [24, 42]. Therefore, TCR-ITK signaling is important for skin-homing of DETCs in the epidermis.

CD103

Intergrin αE(CD103) β7 is a glycoprotein expressed on most Vγ3+ thymocytes around E16 and CD103 deficiency can impair these cells’ ability to immigrate and remain in the epidermis [43]. Studies have shown that RunX3, which induces the expression of CD103 during development of CD8 single-positive (SP) T cells, is also required for DETC development [39, 44]. Whether it induces CD103 expression in DETCs is not clear. Interestingly, CD103 deficiency leads to spontaneous inflammatory skin lesions, whereas complete RunX3-KO does not [45]. RunX3 plays an important role in the development and function of other cutaneous immune cells, thus future studies are needed to explain these differences in the phenotype between CD103- and RunX3-deficient mice. Other downstream target genes, normally repressed by RunX3, may prevent the development of cutaneous lesions in these mice but not CD103-deficient mice.

E- and P-selectin ligands

Endothelial cells express a family of cell adhesion molecules called selectins [46]. Specifically, endothelial cells express E- and P-selectins. During leukocyte extravasation, E- and P-selectins on endothelial cells permit rolling-adhesion of leukocytes by binding to selectin ligands (e.g. Sialyl-Lewsx). DETCs in adult skin and the DETC precursors in the fetal thymus express ligands for E- and P-selectins, which contribute to the embryonic trafficking of DETCs from thymus to epidermis. In fucosyltransferase IV and VII (FTIV/VII) double-deficient mice, selectin ligands do not undergo proper post-translational modification, which interrupts selectin-ligand binding. FTIV/VII double-deficient mice have reduced DETCs in the epidermis despite having a normal number of DETC progenitors. This study highlights the importance of functional E- and P-selectin ligands on DETC progenitors in permitting migration and colonization of the skin, but not thymic development [47].

Chemokines and chemokine receptors

Chemokines and chemokine receptors regulate tissue-specific migration, maintenance, development, and function of γδ T cells and DETCs. DETCs and their thymic precursors express CCR4 and CCR10. Early studies identified a clear role for CCR4 in skin-homing of DETC precursors, whereas CCR10-null mice had normal levels of DETCs in the skin of adult mice, suggesting that CCR4 was enough to carry out proper epidermal migration [47]. However, another study had found that in CCR10−/− mice had dramatically reduced levels of DETCs at the fetal stage, which reached normal levels as the mouse aged. CCL27 is predominantly expressed by epidermal basal keratinocytes, but also is secreted and anchored to the extracellular matrix and dermal endothelial cells. This may setup a chemokine gradient, which allows migrating DETCs to localize to the basal epidermis, once in the skin. In CCR10−/− mice, Vγ3+ γδ T cells had lost their dendritic morphology in the skin and had increased localization in the dermis, suggesting that the interaction between CCR10 and CCL27/28 is important for functional development and localization of DETCs within the skin [48]. While proper CCR10–CCL27 signaling convincingly localizes DETCs to the epidermis, it may be that other factors or cell–cell interactions in the basal epidermis drive DETC maturation. Taken together, these studies showed that CCR4 and CCR10 are important in regulating migration of Vγ3+ γδ T cell precursors and maintenance of proper distribution of skin-resident Vγ3+ γδ T cells.

Genes involved in DETC maintenance of skin homeostasis AhR

Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), cytosolic receptor for 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzodioxin (TCDD) and a ligand-activated transcription factor, belongs to the basic helix–loop–helix family and is expressed by various cells in the skin such as keratinocytes, fibroblasts, Langerhans cells (LCs), melanocytes, and DETCs [49, 50]. In DETCs, AhR plays a critical role in skin maintenance and communication with LCs. AhR−/− mice had impaired DETC proliferation by abrogating downstream c-kit expression. Granulocyte–monocyte colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) is upregulated as a result of AhR signaling. LC maturation is impaired in AhR−/− mice, which was shown to be a result of diminished DETC derived GM-CSF [51–53]. AhR is also involved in intestinal epithelial cell proliferation through an AhR–E2F1–KGFR signaling pathway [49], whether this pathway is also involved in AhR-mediated DETC homeostasis after birth requires further investigation.

LAT

Linker for activation of T cells (LAT) is a transmembrane adapter protein and is an essential signaling molecule downstream of TCR signaling [54]. LAT-deficient mice exhibit a block in thymocyte development and lack peripheral T cells [55]. A recent study demonstrated that LAT is required for proliferative expansion of DETCs during neonatal growth and self-renewal in adult life, suggesting a crucial role of LAT in TCR signaling during clonal expansion of DETCs [56].

Genes and molecules involved in DETC function

T-bet

T-bet, the transcription factor encoded by Tbx21, largely determines the functional differentiation of IFN-γ-producing cytolytic T cells, such as CD8+ T cells and natural killer (NK) cells, as well as directing classical Th1 differentiation [30, 57–59]. Interestingly, T-bet is found to be overexpressed by E15 and E16 thymocytes and is associated with the function of mature DETCs. It has been shown that T-bet expression was necessary for IFN-γ release after stimulation with pro-inflammatory cytokines in CD27+ γδ T cells but suppressed IL-17 production in CD27+ γδ T cells [57]. However, the detailed mechanism of how T-bet expression regulates the maturation and function of DETC remains an open question.

PLZF

Promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger protein (PLZF, also known as “zinc finger and BTB domain containing 16”, ZBTB16) has restricted expression to early-developing γδ thymocytes and NKT cell populations [60]. It has been shown that 100% of the Vγ3+ γδ T cells in adult mouse skin have been derived from PLZF-expressing precursors, whereas PLZF is not essential for DETC development. Skint-1, expressing on TECs, is a thymic stromal determinant that binds Vγ3 TCR to mediate positive selection of DETCs in the embryonic thymus, which helps to promote maturation and subsequently maintenance in the skin [61, 62]. Interestingly, in Skint-1 mutant mice, Vγ3+ cells switch from producing IFN-γ to IL-17, which depends on PLZF [63]. This study suggests PLZF maintains proper function of certain DETC functional programs, specifically production of IL-17, and points to a mechanism by which DETCs can produce a wide diversity of cytokines from different functional arms of the immune system. How DETCs regulate the expression of transcription factors with different functional outcomes in wild-type mice requires further study.

NKG2D

Natural killer group 2, member D (NKG2D) is a homodimeric C-type lectin-like receptor and acts as an activating receptor present on the surface of immune cells such as NK cells and γδ T cells [64]. Usually in mice, NKG2D can associate with both DAP10 and DAP12 to induce murine NK cell activation [65], whereas NKG2D expression in DETCs are involved in DETC responses against tumors, in wound healing, and contact dermatitis [66–68]. The ligands for NKG2D (NKG2DL) are stress-induced proteins including mouse UL16-binding protein-like transcript-1 (Mult-1), histocompatibility 60c (H60c), retinoic acid early inducible-1 (Rae-1) in mice [66, 69]. It has been shown that keratinocyte-specific up-regulation of Rae-1, H60c and Mult-1 has the ability to directly activate DETCs [70], and these interactions play a critical role in wound repair and contact hypersensitivity [66]. Additionally, under certain conditions, NKG2D-mediated recognition of stress ligands is sufficient to trigger DETC cytotoxicity via PI3K-signaling [71]. These data suggest that different NKG2D-ligands are involved in the regulation of DETC activation and function by different mechanisms, which depend on the types of stimulation received by the skin. Thus, NKG2D expressed on DETCs might act as a coreceptor to guide appropriate response to stimuli. Conversely, inhibitory receptors CD94/NKG2 are found on DETCs, which might serve to counterbalance NKG2D [72, 73]. How DETCs integrate NKG2D signals remains controversial. A better understanding of how NKG2D integration with other signaling pathways may help to elucidate the mechanisms behind DETCs’ pleiotropic function.

JAML

The junctional adhesion molecule-like protein (JAML) is a costimulatory receptor specific for epithelial γδ T cells. The interaction of JAML with its ligand Coxsackie and adenovirus receptor (CAR) induces PI3K activation leading to potent costimulation of epithelial γδ T cells. In DETCs, costimulation through JAML leads to a stronger activation signal than TCR stimulation alone, and the costimulatory role is crucial for effective DETC-mediated wound healing in mouse skin [36, 74] Therefore, JAML acts as a costimulatory protein and is involved in regulating DETC function.

CD100

CD100, known as Semaphorin 4D, is highly expressed on T cells and lowly expressed on B cells and APCs. CD100 is upregulated upon activation and binds with high affinity to plexin B1 in the central nervous system and with lower affinity to CD72 on B cells in the immune system. Interestingly, CD100 is also a costimulatory molecule and interacts with CD72 to enhance B-cell responses by turning off the negative signals of CD72’s two immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs (ITIMs) [75]. CD100 is expressed by DETCs and interacts with plexin B2 expressed on damaged keratinocytes to activate DETCs and promote wound healing [36, 76].

The functions of DETCs in murine models of skin disease

DETC function in contact allergy

Contact hypersensitivity (CHS), an experimental animal model for contact allergy, is a T cell-mediated inflammatory disease induced by exposure of the skin to contact allergens. A previous study showed that DETCs were required for αβ T cell-mediated CHS responses in which the increased number of DETCs activated by anti-Vγ3 antibodies augmented CHS responses, whereas TCRβ−/− alleviated CHS responses in mice [77]. Furthermore, IL-17 is an important cytokine in the pathogenesis of allergic diseases [78], and an increased number of IL-17 producing DETCs appear in the skin following exposure to 2,4-dinitrofluorobenzene in mice. DETCs become activated and produce IL-17 in an IL-1β-dependent manner during CHS [10]. These results suggested that DETCs play a key role in CHS.

DETC function in atopic dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common inflammatory skin disease associated with dysregulation of the skin barrier, frequently recognized as the first manifestation of allergic disease, and affects 20% of children and 3% of adults worldwide [79]. During AD-like chronic dermatitis in mice, DETCs (which rapidly respond to various insults) accumulate in the epidermis before the development of histological abnormalities, and their number and activation further increase as the phenotype progresses due to increased expression of IL-2 and IL-7. These results suggest that DETCs might play an important role in the pathogenesis of AD. Depletion of γδ T cells in K5-FGFR1/R2 mice (mice lacking FGFR1/R2 in keratinocytes develop an AD-like chronic dermatitis) did not, or only marginally, affect the development or maintenance of chronic inflammation [80]. The same idea is identified in filaggrin (FLG) mutant mice and Il17ra−/−mice which developed spontaneous AD and progressive skin inflammation. Il17ra−/−mice have a defective skin barrier with altered FLG expression as well as increased levels of thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) and IL-5 in the skin. However, the associated skin inflammation mediated by IL-5-expressing pathogenic effector Th2 cells was independent of γδ T cells. These results demonstrate that DETCs are dispensable in this chronic dermatitis despite their observed increase and activation in the skin, the underlying mechanisms that explain this remain unknown.

DETC function in wound healing

Would healing is a complex and dynamic process that progresses through the distinct phases of hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and tissue-remodeling. DETCs are activated by wounded keratinocytes and secrete epidermal cell growth factors, such as IGF-1 and KGF-1/2, to promote re-epithelialization [81]. Studies showed that DETC-derived IL-17A induced the expression of multiple host-defense molecules in epidermal keratinocytes that promote wound healing following skin injury [82, 83]. Moreover, epidermal IL-15 and IGF-1 constitute a regulatory feedback loop to promote repair [84]. In normal wounds, the interaction of the DETC-mediated IL-15-IGF-1 loop with epidermis-infiltrating Vγ4 T cell-mediated IL-17A-IL-1β/IL-23 loop delays skin wound closure. However, in diabetic wounds, the interplay can improve the defects of diabetic wound healing [85, 86]. DETC expression of three accessory molecules: JAML, CD100 and NKG2D receptor has been identified to show great importance to DETC activation and wound healing [20].

DETC’s anti-tumor function

DETCs can kill skin-derived tumor cells in vitro and protect against different types of experimental skin tumors in vivo, including DMBA/TPA-induced papilloma and squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) [68, 87]. Further studies showed that activin could inhibit proliferation of DETCs to promote tumor formation and their malignant progression [88].

DETC-derived cytokines induce antimicrobial skin functions

DETC-derived IL-17A is critical to induce epidermal β-defensin 3 and S100A8 as well as keratinocyte production of several antimicrobial peptides, such as the regenerating islet-derived (Reg) protein RegIIIγ, suggesting that DETC-derived IL-17A functions to promote the antimicrobial properties of skin [82]. In addition, DETCs can recruit neutrophils to the skin upon infection with Staphylococcus aureus, and also directly respond to Gram-negative bacteria through LPS stimuli to promote cytokine production [89, 90].

Conclusions and perspective

DETCs express a canonical γδ T cell receptor composed of Vγ3 and Vδ1 chains (alternative nomenclature Vγ5+Vδ1+ T cell) and are the first line of defense in maintaining homeostasis in the skin. Studies over the past few years have provided valuable insight into the molecular regulation of the development, activation, and function of these unique T cells. As shown in Fig. 2, the genes involved in DETC development and maintenance in the thymus and epidermis are summarized and depicted with a plausible regulatory network. The multiple regulators including the cell-intrinsic and external environmental factors contribute to DETC embryonic development, skin-homing, skin maintenance, and function. Our recent study showed that Csf1rCre mice were a useful tool for fate mapping of embryonic development of DETCs [40], which may help to further elucidate the cellular, genetic and epigenetic mechanisms influencing early development of DETCs. Some key questions about the DETC development and function still need to be further answered, including (1) given that DETCs express an invariant γδ TCR, what are their endogenous antigen(s)? (2) Since DETCs appear to be a rich source for a variety of cytokines and chemokines, do DETCs fit into a clear T cell-based scheme of restricted cytokine production as observed for Th1, Th2, Th17, or are they functionally unique? (3) What genes are critical during early DETC precursor commitment from yolk sac hematopoiesis? The precise answers of these questions might provide promising insight of DETC biology and new therapeutic strategies for skin diseases including allergies, inflammation, and autoimmune diseases.

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by the Henry Ford Immunology Program Grants (T71016, QS Mi; T71017, L Zhou).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

No conflicts of interest for each author.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Li Zhou, Email: lzhou1@hfhs.org.

Qing-Sheng Mi, Email: qmi1@hfhs.org.

References

- 1.Brenner MB, et al. Identification of a putative second T-cell receptor. Nature. 1986;322(6075):145–149. doi: 10.1038/322145a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmolka N, et al. Epigenetic and transcriptional regulation of gammadelta T cell differentiation: programming cells for responses in time and space. Semin Immunol. 2015;27(1):19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raulet DH. The structure, function, and molecular genetics of the gamma/delta T cell receptor. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:175–207. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.001135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vantourout P, Hayday A. Six-of-the-best: unique contributions of gammadelta T cells to immunology. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(2):88–100. doi: 10.1038/nri3384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiest DL. Development of gammadelta T Cells, the special-force soldiers of the immune system. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1323:23–32. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2809-5_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Kaer L, Olivares-Villagomez D. Development, homeostasis, and functions of intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2018;200(7):2235–2244. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1701704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nielsen MM, Witherden DA, Havran WL. Gammadelta T cells in homeostasis and host defence of epithelial barrier tissues. J Immunol. 2017;17(12):733–745. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garman RD, Doherty PJ, Raulet DH. Diversity, rearrangement, and expression of murine T cell gamma genes. Cell. 1986;45(5):733–742. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90787-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heilig JS, Tonegawa S. Diversity of murine gamma genes and expression in fetal and adult T lymphocytes. Nature. 1986;322(6082):836–840. doi: 10.1038/322836a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nielsen MM, et al. IL-1beta-dependent activation of dendritic epidermal T cells in contact hypersensitivity. J Immunol. 2014;192(7):2975–2983. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Floudas A, et al. IL-17 receptor A maintains and protects the skin barrier to prevent allergic skin inflammation. J Immunol. 2017;199(2):707–717. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1602185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Toulon A, et al. A role for human skin-resident T cells in wound healing. J Exp Med. 2009;206(4):743–750. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Havran WL, Allison JP. Origin of Thy-1+ dendritic epidermal cells of adult mice from fetal thymic precursors. Nature. 1990;344(6261):68–70. doi: 10.1038/344068a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McVay LD, Carding SR. Extrathymic origin of human gamma delta T cells during fetal development. J Immunol. 1996;157(7):2873–2882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McVay LD, et al. The generation of human gammadelta T cell repertoires during fetal development. J Immunol. 1998;160(12):5851–5860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gentek R, et al. Epidermal gammadelta T cells originate from yolk sac hematopoiesis and clonally self-renew in the adult. J Exp Med. 2018;215(12):2994–3005. doi: 10.1084/jem.20181206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chodaczek G, et al. Body-barrier surveillance by epidermal gammadelta TCRs. Nat Immunol. 2012;13(3):272–282. doi: 10.1038/ni.2240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng M, Hu S. Lung-resident gammadelta T cells and their roles in lung diseases. Immunology. 2017;151(4):375–384. doi: 10.1111/imm.12764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vantourout P, Hayday A. Six-of-the-best: unique contributions of gammadelta T cells to immunology. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(2):88–100. doi: 10.1038/nri3384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nielsen MM, Witherden DA, Havran WL. Gammadelta T cells in homeostasis and host defence of epithelial barrier tissues. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17(12):733–745. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrero I, et al. T cell receptor specificity is critical for the development of epidermal gammadelta T cells. J Exp Med. 2001;194(10):1473–1483. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.10.1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hara H, et al. Development of dendritic epidermal T cells with a skewed diversity of gamma delta TCRs in V delta 1-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2000;165(7):3695–3705. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.7.3695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mallick-Wood CA, et al. Conservation of T cell receptor conformation in epidermal gammadelta cells with disrupted primary Vgamma gene usage. Science. 1998;279(5357):1729–1733. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5357.1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xiong N, Kang C, Raulet DH. Positive selection of dendritic epidermal gammadelta T cell precursors in the fetal thymus determines expression of skin-homing receptors. Immunity. 2004;21(1):121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Narayan K, et al. Intrathymic programming of effector fates in three molecularly distinct gammadelta T cell subtypes. Nat Immunol. 2012;13(5):511–518. doi: 10.1038/ni.2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kawai K, et al. Impaired development of V gamma 3 dendritic epidermal T cells in p56lck protein tyrosine kinase-deficient and CD45 protein tyrosine phosphatase-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1995;181(1):345–349. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.1.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kadlecek TA, et al. Differential requirements for ZAP-70 in TCR signaling and T cell development. J Immunol. 1998;161(9):4688–4694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mallick-Wood CA, et al. Disruption of epithelial gamma delta T cell repertoires by mutation of the Syk tyrosine kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(18):9704–9709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lauritsen JP, et al. Marked induction of the helix-loop-helix protein Id3 promotes the gammadelta T cell fate and renders their functional maturation Notch independent. Immunity. 2009;31(4):565–575. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turchinovich G, Hayday AC. Skint-1 identifies a common molecular mechanism for the development of interferon-gamma-secreting versus interleukin-17-secreting gammadelta T cells. Immunity. 2011;35(1):59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Briseno CG, et al. Deficiency of transcription factor RelB perturbs myeloid and DC development by hematopoietic-extrinsic mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114(15):3957–3962. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1619863114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Riemann M, et al. Central immune tolerance depends on crosstalk between the classical and alternative NF-kappaB pathways in medullary thymic epithelial cells. J Autoimmun. 2017;81:56–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2017.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roberts NA, et al. Rank signaling links the development of invariant gammadelta T cell progenitors and Aire(+) medullary epithelium. Immunity. 2012;36(3):427–437. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mair F, et al. The NFkappaB-inducing kinase is essential for the developmental programming of skin-resident and IL-17-producing gammadelta T cells. Elife. 2015;4:e10087. doi: 10.7554/eLife.10087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park SY, et al. Developmental defects of lymphoid cells in Jak3 kinase-deficient mice. Immunity. 1995;3(6):771–782. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Witherden DA, Havran WL. Molecular aspects of epithelial gammadelta T cell regulation. Trends Immunol. 2011;32(6):265–271. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moore TA, et al. Inhibition of gamma delta T cell development and early thymocyte maturation in IL-7−/− mice. J Immunol. 1996;157(6):2366–2373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kang J, et al. STAT5 is required for thymopoiesis in a development stage-specific manner. J Immunol. 2004;173(4):2307–2314. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.4.2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Woolf E, et al. Runx3 regulates dendritic epidermal T cell development. Dev Biol. 2007;303(2):703–714. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yao Y, et al. Embryonic fate mapping uncovers the critical role of microRNAs in the development of epidermal gammadelta T cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138(1):236–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Andreotti AH, et al. T-cell signaling regulated by the Tec family kinase, Itk. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2(7):a002287. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a002287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xia M, et al. Differential roles of IL-2-inducible T cell kinase-mediated TCR signals in tissue-specific localization and maintenance of skin intraepithelial T cells. J Immunol. 2010;184(12):6807–6814. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schon MP, et al. Dendritic epidermal T cells (DETC) are diminished in integrin alphaE(CD103)-deficient mice. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;119(1):190–193. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.17973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grueter B, et al. Runx3 regulates integrin alpha E/CD103 and CD4 expression during development of CD4-/CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 2005;175(3):1694–1705. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Girardi M, et al. Resident skin-specific gammadelta T cells provide local, nonredundant regulation of cutaneous inflammation. J Exp Med. 2002;195(7):855–867. doi: 10.1084/jem.20012000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ley K, Kansas GS. Selectins in T-cell recruitment to non-lymphoid tissues and sites of inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4(5):325–335. doi: 10.1038/nri1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jiang X, Campbell JJ, Kupper TS. Embryonic trafficking of gammadelta T cells to skin is dependent on E/P selectin ligands and CCR4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(16):7443–7448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912943107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jin Y, et al. CCR10 is important for the development of skin-specific gammadeltaT cells by regulating their migration and location. J Immunol. 2010;185(10):5723–5731. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li Y, et al. Exogenous stimuli maintain intraepithelial lymphocytes via aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation. Cell. 2011;147(3):629–640. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gu YZ, Hogenesch JB, Bradfield CA. The PAS superfamily: sensors of environmental and developmental signals. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2000;40:519–561. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.40.1.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jux B, Kadow S, Esser C. Langerhans cell maturation and contact hypersensitivity are impaired in aryl hydrocarbon receptor-null mice. J Immunol. 2009;182(11):6709–6717. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0713344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kadow S, et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor is critical for homeostasis of invariant gammadelta T cells in the murine epidermis. J Immunol. 2011;187(6):3104–3110. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Prell RA, Oughton JA, Kerkvliet NI. Effect of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin on anti-CD3-induced changes in T-cell subsets and cytokine production. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1995;17(11):951–961. doi: 10.1016/0192-0561(95)00080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Myers DR, Zikherman J, Roose JP. Tonic signals: why do lymphocytes bother? Trends Immunol. 2017;38(11):844–857. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2017.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang W, et al. Essential role of LAT in T cell development. Immunity. 1999;10(3):323–332. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang B, et al. Differential requirements of TCR signaling in homeostatic maintenance and function of dendritic epidermal T cells. J Immunol. 2015;195(9):4282–4291. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barros-Martins J, et al. Effector gammadelta T cell differentiation relies on master but not auxiliary Th cell transcription factors. J Immunol. 2016;196(9):3642–3652. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Girardi M, et al. Regulation of cutaneous malignancy by gammadelta T cells. Science. 2001;294(5542):605–609. doi: 10.1126/science.1063916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Szabo SJ, et al. A novel transcription factor, T-bet, directs Th1 lineage commitment. Cell. 2000;100(6):655–669. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80702-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Buus TB, et al. Three distinct developmental pathways for adaptive and two IFN-gamma-producing gammadelta T subsets in adult thymus. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):1911. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01963-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Salim M, et al. Characterization of a putative receptor binding surface on Skint-1, a critical determinant of dendritic epidermal T cell selection. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(17):9310–9321. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.722066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lewis JM, et al. Selection of the cutaneous intraepithelial gammadelta+ T cell repertoire by a thymic stromal determinant. Nat Immunol. 2006;7(8):843–850. doi: 10.1038/ni1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lu Y, et al. PLZF controls the development of fetal-derived IL-17+Vgamma6+ gammadelta T Cells. J Immunol. 2015;195(9):4273–4281. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Champsaur M, Lanier LL. Effect of NKG2D ligand expression on host immune responses. Immunol Rev. 2010;235(1):267–285. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2010.00893.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Diefenbach A, et al. Selective associations with signaling proteins determine stimulatory versus costimulatory activity of NKG2D. Nat Immunol. 2002;3(12):1142–1149. doi: 10.1038/ni858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nielsen MM, et al. NKG2D-dependent activation of dendritic epidermal T cells in contact hypersensitivity. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135(5):1311–1319. doi: 10.1038/jid.2015.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Havran WL, Jameson JM. Epidermal T cells and wound healing. J Immunol. 2010;184(10):5423–5428. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Girardi M, et al. The distinct contributions of murine T cell receptor (TCR)gammadelta+ and TCRalphabeta+ T cells to different stages of chemically induced skin cancer. J Exp Med. 2003;198(5):747–755. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yoshida S, et al. Involvement of an NKG2D ligand H60c in epidermal dendritic T cell-mediated wound repair. J Immunol. 2012;188(8):3972–3979. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Strid J, et al. The intraepithelial T cell response to NKG2D-ligands links lymphoid stress surveillance to atopy. Science. 2011;334(6060):1293–1297. doi: 10.1126/science.1211250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ibusuki A, et al. NKG2D triggers cytotoxicity in murine epidermal gammadelta T cells via PI3K-dependent, Syk/ZAP70-independent signaling pathway. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134(2):396–404. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Van Beneden K, et al. Expression of inhibitory receptors Ly49E and CD94/NKG2 on fetal thymic and adult epidermal TCR V gamma 3 lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2002;168(7):3295–3302. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.7.3295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dadi S, et al. Cancer immunosurveillance by tissue-resident innate lymphoid cells and innate-like T cells. Cell. 2016;164(3):365–377. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Witherden DA, et al. The junctional adhesion molecule JAML is a costimulatory receptor for epithelial gammadelta T cell activation. Science. 2010;329(5996):1205–1210. doi: 10.1126/science.1192698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kumanogoh A, Kikutani H. Biological functions and signaling of a transmembrane semaphorin, CD100/Sema4D. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61(3):292–300. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3257-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Witherden DA, et al. The CD100 receptor interacts with its plexin B2 ligand to regulate epidermal gammadelta T cell function. Immunity. 2012;37(2):314–325. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Macleod AS, Havran WL. Functions of skin-resident gammadelta T cells. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68(14):2399–2408. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0702-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gupta RK, Gupta K, Dwivedi PD. Pathophysiology of IL-33 and IL-17 in allergic disorders. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2017;38:22–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2017.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Abuabara K, et al. The prevalence of atopic dermatitis beyond childhood: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Allergy. 2018;73(3):696–704. doi: 10.1111/all.13320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sulcova J, et al. Accumulation and activation of epidermal gammadelta T cells in a mouse model of chronic dermatitis is not required for the inflammatory phenotype. Eur J Immunol. 2015;45(9):2517–2528. doi: 10.1002/eji.201545675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jameson J, et al. A role for skin gammadelta T cells in wound repair. Science. 2002;296(5568):747–749. doi: 10.1126/science.1069639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.MacLeod AS, et al. Dendritic epidermal T cells regulate skin antimicrobial barrier function. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(10):4364–4374. doi: 10.1172/JCI70064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rodrigues M, et al. Wound healing: a cellular perspective. Physiol Rev. 2019;99(1):665–706. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00067.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wang Y, et al. IL-15 enhances activation and IGF-1 production of dendritic epidermal T cells to promote wound healing in diabetic mice. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1557. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Li Y, et al. Functions of Vgamma4 T cells and dendritic epidermal T cells on skin wound healing. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1099. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Li Y, et al. Vgamma4 T cells inhibit the pro-healing functions of dendritic epidermal T cells to delay skin wound closure through IL-17A. Front Immunol. 2018;9:240. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Girardi M. Immunosurveillance and immunoregulation by gammadelta T cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126(1):25–31. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Antsiferova M, et al. Activin enhances skin tumourigenesis and malignant progression by inducing a pro-tumourigenic immune cell response. Nat Commun. 2011;2:576. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cho JS, et al. IL-17 is essential for host defense against cutaneous Staphylococcus aureus infection in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(5):1762–1773. doi: 10.1172/JCI40891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Leclercq G, Plum J. Stimulation of TCR V gamma 3 cells by gram-negative bacteria. J Immunol. 1995;154(10):5313–5319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]