Abstract

Background:

Effective and safe treatment options for MS are still needed. Montelukast, a leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA) currently indicated for asthma or allergic rhinitis, may provide an additional therapeutic approach.

Objective:

Evaluate the effects of montelukast on the relapses of people with MS (pwMS).

Methods:

In this retrospective case-control study, two independent longitudinal claims datasets were utilized to emulate randomized clinical trials (RCTs). We identified pwMS aged 18 to 65, on MS disease-modifying therapies concomitantly, in de-identified claims from Optum’s Clinformatics® DataMart (CDM) and IQVIA PharMetrics® Plus for Academics. Cases included 483 pwMS on montelukast and with medication adherence in CDM and 208 in PharMetrics Plus for Academics. We randomly sampled controls from 35,330 pwMS without montelukast prescriptions in CDM and 10,128 in PharMetrics Plus for Academics. Relapses were measured over a two-year period through inpatient hospitalization and corticosteroid claims. A doubly robust causal inference model estimated the effects of montelukast, adjusting for confounders and censored patients.

Results:

pwMS treated with montelukast demonstrated a statistically significant 23.6% reduction in relapses compared to non-users in 67.3% of emulated RCTs.

Conclusions:

Real-world evidence suggested that montelukast reduces MS relapses, warranting future clinical trials and further research on LTRAs’ potential mechanism in MS.

Keywords: multiple sclerosis (MS), drug repurposing, montelukast, leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA), administrative health claims, doubly robust, clinical informatics

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a complex inflammatory and neurodegenerative disorder, exhibiting immune-mediated demyelination of the central nervous system (CNS). It affects millions of individuals worldwide and is a leading cause of disability.1 Most people with MS (pwMS) will experience relapses during their lifetime. These periods of neurological exacerbation contribute to worsening disability.2 Relapse rate is currently the most frequently used primary endpoint in MS phase 3 trials to assess the efficacy of disease-modifying therapies (DMTs). Despite recent advancements in MS treatment, aimed at decreasing relapse incidence and disease progression, there is still an urgent need for more treatment options.3 Most medications currently available for MS modulate or suppress the immune system, which may lead to an increased risk of infection among other complications. Safer treatment options may reduce the morbidity associated with MS DMTs.

Drug repurposing strategies that explore new indications for existing drugs have the potential to discover novel treatments for MS. Previously, we have conducted bioinformatics analysis of MS multi-omics data to investigate drug targets and repurposable drug candidates for MS treatment.4,5 In our analysis, we integrated MS genomics data with brain tissue expression through network-based methods, using the human protein interactome as the reference network to pinpoint actionable drug target genes. A prominent drug candidate emerging from the bioinformatic analysis was zafirlukast, a leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA).4 The features driving the prediction of this LTRA for MS treatment involved enrichment of the drug signature genes KAT2A, MAPK1 and MAPK3 in a MS-associated gene network.5 LTRAs are drugs commonly indicated for asthma or allergic rhinitis that block the action of leukotrienes, which are strong mediators of inflammation.6 Other studies have also suggested LTRAs as potential treatment for MS, as leukotrienes have been found in the cerebrospinal fluid of MS patients.7–9 LTRAs were shown to have an immunopharmacological role in decreasing inflammatory reactions in CNS of MS patients.10 Thus, we hypothesized that inhibition of leukotriene might reduce relapses in MS patients. Due to the recent discontinuation of zafirlukast, we focused in the current study on a more widely used LTRA, montelukast.11 In support of testing montelukast, recent studies have demonstrated that it decreases inflammation in a mouse model of MS, autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE).12, 13 Moreover, recent investigations have shown that montelukast may have neuroprotective effects in neurodegenerative disorders, as it can reduce inflammation and oxidative stress in the brain, thereby protecting neurons from damage and degeneration.14–16

Emulating randomized clinical trials (RCTs) using observational clinical data allows researchers to estimate treatment effects and evaluate the impact of interventions on patient outcomes in a cost-effective way while utilizing sample sizes that are hard to reach in prospective studies.17, 18 In this study, we aimed to investigate the effect of montelukast on MS relapses by using real-world clinical data. We implemented validated algorithms for the identification of pwMS and the measurement of relapse rates. Medical chart validation was essential to ensure accurate, reliable patient data, supporting research and clinical decision-making. Specifically, we used retrospective de-identified administrative health claims data from the Optum’s Clinformatics® Data Mart (CDM) and the IQVIA PharMetrics® Plus for Academics databases to evaluate montelukast effect on MS outcomes.

Methods

Data

We evaluated the effect of montelukast on MS relapses using two large de-identified claims datasets from members of large commercial and Medicare health plans across the United States. Optum’s de-identified Clinformatics® Data Mart Database (CDM) includes 68 million patients, spanning the years 2007 to 2020, and the IQVIA PharMetrics® Plus for Academics includes 28 million patients spanning the years 2014 to 2022.

Defining Cohorts

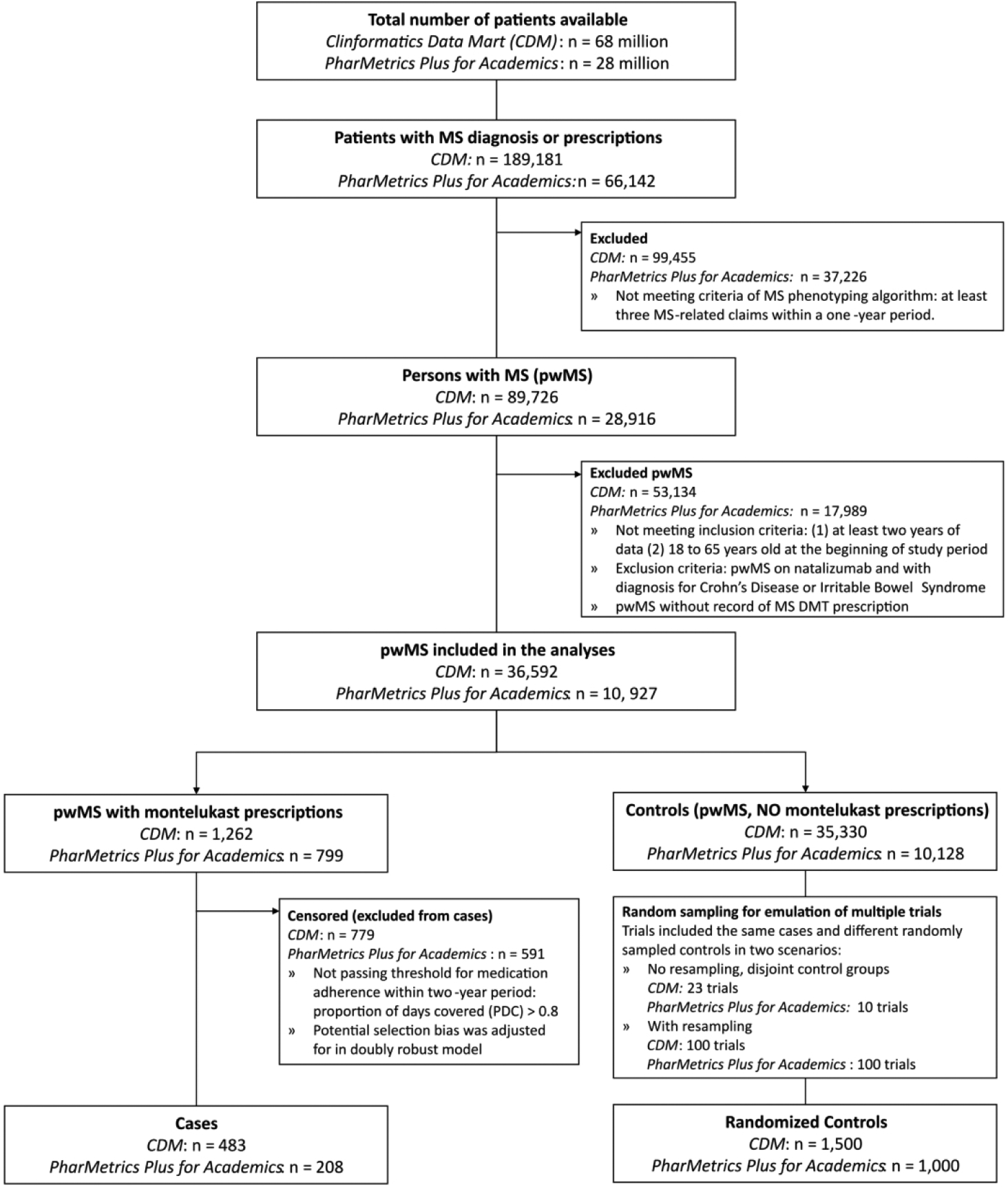

To identify pwMS, we adopted a validated MS phenotyping algorithm in Culpepper et al. as the standard administrative health claims case definition for MS.19 This algorithm has a positive predictive value (PPV) of approximately 99% and a negative predictive value (NPV) of approximately 96%.20 Figure 1 presents an overview of our pipeline.

Figure 1.

Overview of study design. The administrative health claims data was filtered by a validated MS phenotyping algorithm to identify MS patients. The patients were further filtered by requiring at least two years of clinical data, age at baseline (within 18 and 65 years old), and estimations of Proportion of Days Covered (PDC) greater than 0.8. Outcomes were measured by detecting MS relapses with a validated algorithm. The causal inference model adjusted for confounding factors and selection bias.

MS inclusion criteria:

Patients aged between 18 and 65 years old at the beginning of the study period (censored or control patients) or the index date (cases) with at least two years of available clinical data and at least three MS-related health claims within a one-year period. MS-related claims were defined based on MS diagnosis [the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes: ICD-9 code ‘340’ and ICD-10 code ‘G35’], or prescription claims of MS drugs (alemtuzumab, cladribine, dimethyl fumarate, diroximel fumarate, fingolimod, glatiramer acetate, interferon beta-1a, interferon beta-1b, natalizumab, ocrelizumab, peginterferon beta-1a, siponimod fumarate, and teriflunomide). All extracted MS-related claims were surveyed accordingly for the classification of MS patients based on the Culpepper definition. Due to differences in data representation between the two data sources, we used generic drug names in the CDM, and National Drug Codes (NDCs) in the PharMetrics Plus for Academics dataset (Table S1 in Supplementary Materials). Furthermore, we only included pwMS with a record of MS diagnosis and an MS DMT prescription. Therefore, all pwMS included in our analysis were taking an MS DMT concomitantly.

Exclusion criteria:

As natalizumab has other indications besides MS, patients with natalizumab prescriptions and ICD code for Crohn’s disease or inflammatory bowel disease were excluded. Patients without a record of MS diagnosis or MS DMT prescription were also excluded.

Identification of cases:

We extracted all claims involving prescription of montelukast. Generic names were used to query the CDM dataset, and montelukast NDCs were used to query the PharMetrics Plus for Academics dataset (Table S1 in Supplementary Materials). We utilized a common metric for measuring medication adherence, the Proportion of Days Covered (PDC), by considering the dates filled and supplied in montelukast prescription claims.20 Specifically, PDC is a ratio calculated with the number of days covered by pharmacy prescriptions as the numerator, with adjustments for days supplied, and a predefined period of interest (POI) as the denominator.20 Here, the predefined POI was a two-year period (730 or 731 days, depending on the event of a leap year). Individual POI dates of each patient in the cases group were selected by a sliding window algorithm for identification of a particular two-year period with PDC greater than 0.8, as suggested by the Pharmacy Quality Alliance21, between the first and last day of all filled montelukast prescriptions (Figure S1 in Supplementary Materials). Therefore, the dates of POI varied for each patient in the case group based on PDC measures. By limiting cases to the individuals adherent to montelukast, we assume the dosage used for asthma/allergic rhinitis is similar to the necessary dose for MS.

Censored cohort:

Patients who did not pass the threshold of montelukast medication adherence (PDC > 0.8) in any two-year window were classified as the censored group and were used to adjust for potential selection bias. The study period for individuals in censored group began at the first date of montelukast period and ended after a two-year follow-up.

Control subjects:

MS patients without any montelukast prescriptions were classified as controls if they fit the inclusion criteria. For these patients, we defined the study period as the last two years of prescription claims.

Measuring Outcomes as MS Relapses

We defined the outcomes of montelukast treatment as the number of MS relapses within the defined two-year study period following the index date (cases) or study start date (censored and controls). To identify MS relapses in healthcare claims data, we implemented two previously validated algorithms.22,23 The first algorithm, developed by Marriott et al., has demonstrated a PPV of 1.0 and an NPV of 96%.22 Relapse markers for this algorithm included outpatient prednisone prescriptions exceeding 50 mg/day for a duration of 3 to 60 days, or the occurrence of inpatient encounters with MS as the primary diagnosis.22

The second algorithm was developed by Chastek et al. with a reported PPV of 67.3% and NPV of 70%.23 According to this algorithm, relapses may be identified by either: (1) a confinement (inpatient) claim with MS diagnosis as the primary diagnosis, or (2) an outpatient claim with an MS diagnosis code in the primary or secondary position and a pharmacy claim of a corticosteroid within 7 days. We identified prescription claims for corticosteroids dexamethasone, methylprednisolone, prednisolone, prednisone and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH).

RCT Emulations

We constructed a causal inference model based on the aforementioned cohorts and outcomes. Our causal inference model consisted of a doubly robust estimator, which corrected for selection bias of censored patients and confounders that affected both montelukast exposure and patient outcomes.19, 24 Doubly robust estimators combine both standardization model and inverse probability weighting (IPW) modelling and consistently estimate the causal effect if at least one of the two models is correct.19, 24 In this approach, it is not necessary to identify which of the two models is correct. The model adjusted for a comprehensive set of confounders, including demographics (age, gender, and race), the indication of montelukast (asthma or allergic rhinitis), and MS DMT administered during the study period (alemtuzumab, cladribine, fumarates, fingolimod, natalizumab, ocrelizumab, teriflunomide, interferon and glatiramer acetate). Vitamin D deficiency was included as a common comorbidity associated with MS, and the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index was incorporated to systematically account for a broader spectrum of conditions.25 The association test used in this analysis to determine statistically significant differences in the estimated outcomes was the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. We compared the Annualized Relapse Rate (ARR) between a counterfactual estimate of the entire cohort as cases relative to the counterfactual estimate of the cohort as controls. The ARR is a common outcome measure in MS clinical trials, defined as the ratio of total relapses to person years.26 Furthermore, we performed bootstrap sampling to estimate 95% confidence intervals by 100 runs that randomly sampled from the same population in each respective dataset, with replacements. To verify the quality of the confounder adjustments, we examined the imbalance of confounders before and after confounder correction, as described by Austin.19, 27 Lastly, we evaluated the E-value according to the guidelines of VanderWeele et al. to assess the strength of evidence for an observed association and to quantify the potential impact of unmeasured confounding.28 The detailed calculation of imbalance scores and E-value analysis were provided in the Methods in Supplementary Materials. Since the number of cases was much smaller than that of controls in both datasets, we performed several trials including the same cases and censored groups but each trial included a randomly sampled group of controls. We performed 100 trials with replacement for each dataset and each algorithm to generate a larger number of trials to assess the robustness of the results. Altogether, we carried out 400 emulated RCTs for estimating the effect of montelukast on MS relapses.

Results

By applying the MS phenotyping algorithm (see Methods), we identified 89,726 MS patients in the CDM dataset and 28,916 MS patients in the PharMetrics Plus for Academics dataset. We identified 483 MS patients on montelukast and with medication adherence (cases, see Methods) in the CDM and 208 cases in PharMetrics Plus for Academics (Figure S1 in Supplementary Materials). We further identified 779 patients in CDM and 591 in PharMetrics Plus for Academics not adherent to montelukast (PDC< 0.8, see Methods), which were categorized as censored patients to adjust for potential selection bias in our model. Finally, we identified 35,330 MS patients as potential controls in the CDM, and 10,128 MS patients as controls in the PharMetrics Plus for Academics. Figure 2 shows a CONSORT flow diagram including the number of patients included and excluded in the steps of our analyses. Demographic characteristics, comorbidities, and DMT utilization are summarized in Table 1 and Figure S2 of Supplementary Materials.

Figure 2.

CONSORT flow diagram of emulated RCTs with claims data. This CONSORT flow diagram shows the process of cohort identification in our retrospective case-control study, including the number of patients included and excluded at each step of the analyses.

Table 1.

Demographics, comorbidities, and MS DMTs of pwMS*

| CDM | PharMetrics Plus for Academics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (n=486) | Censored (n=779) | Controls (n=35330) | Cases (n=208) | Censored (n=591) | Controls (n=10128) | ||

| Age Group (Years) | 26 to 35 | 51 (10.5%) | 171 (22%) | 3886 (11%) | 18 (8.7%) | 92 (15.6%) | 1317 (13%) |

| 36 to 45 | 158 (32.5%) | 312 (40.1%) | 8656 (24.5%) | 57 (27.4%) | 171 (28.9%) | 2603 (25.7%) | |

| 46 to 55 | 220 (45.3%) | 239 (30.7%) | 11906 (33.7%) | 69 (33.2%) | 188 (31.8%) | 3302 (32.6%) | |

| 56 to 65 | 53 (10.9%) | 25 (3.2%) | 10210 (28.9%) | 63 (30.3%) | 117 (19.8%) | 2643 (26.1%) | |

| Indication of Montelukast | Asthma | 356 (73.2%) | 424 (54.4%) | 5017 (14.2%) | 133 (41.3%) | 167 (28.3%) | 513 (5.1%) |

| Allergic Rhinitis | 368 (75.7%) | 540 (69.3%) | 8861 (25.1%) | 74 (35.6%) | 212 (35.9%) | 775 (7.7%) | |

| Comorbidities | Average Elixhauser Comorbidity Index [95% CIs] | 34.4 [31.4, 37.5] | 26.7 [24.9, 28.5] | 20.4 [20.2, 20.7] | 19.9 [17.5, 22.4] | 18.3 [16.9, 19.6] | 14.5 [14.2, 14.7] |

| Vitamin D Deficiency | 307 (63.2%) | 470 (60.3%) | 16131 (45.7%) | 65 (31.2%) | 164 (27.7%) | 2226 (22%) | |

| Gender | Female | 427 (87.9%) | 667 (85.6%) | 26732 (75.7%) | 177 (85.1%) | 502 (84.9%) | 7494 (74%) |

| Male | 59 (12.1%) | 112 (14.4%) | 8598 (24.3%) | 31 (14.9%) | 89 (15.1%) | 2634 (26%) | |

| MS DMTs* | Fingolimod HCl | 39 (8%) | 39 (5%) | 2855 (8.1%) | 11 (5.3%) | 30 (5.1%) | 792 (7.8%) |

| Fumarates | 71 (14.6%) | 60 (7.7%) | 5117 (14.5%) | 35 (16.8%) | 115 (19.5%) | 1518 (15%) | |

| Teriflunomide | 28 (5.8%) | 33 (4.2%) | 2098 (5.9%) | 12 (5.8%) | 26 (4.4%) | 563 (5.6%) | |

| Interferon or Glatiramer | 268 (55.1%) | 446 (57.3%) | 18010 (51%) | 72 (34.6%) | 203 (34.3%) | 3073 (30.3%) | |

| Race* | Black | 55 (10.4%) | 89 (11.6%) | 3655 (10.2%) | -** | - | - |

| Hispanic | 34 (6.9%) | 77 (9.9%) | 2433 (6.9%) | - | - | - | |

| White | 354 (72.8%) | 535 (68.2%) | 25642 (72.1%) | - | - | - | |

Small number of patients were redacted to follow de-identification guidelines in data use agreements of CDM and PharMetrics Plus for Academics datasets.

The PharMetrics Plus for Academics dataset does not include race information.

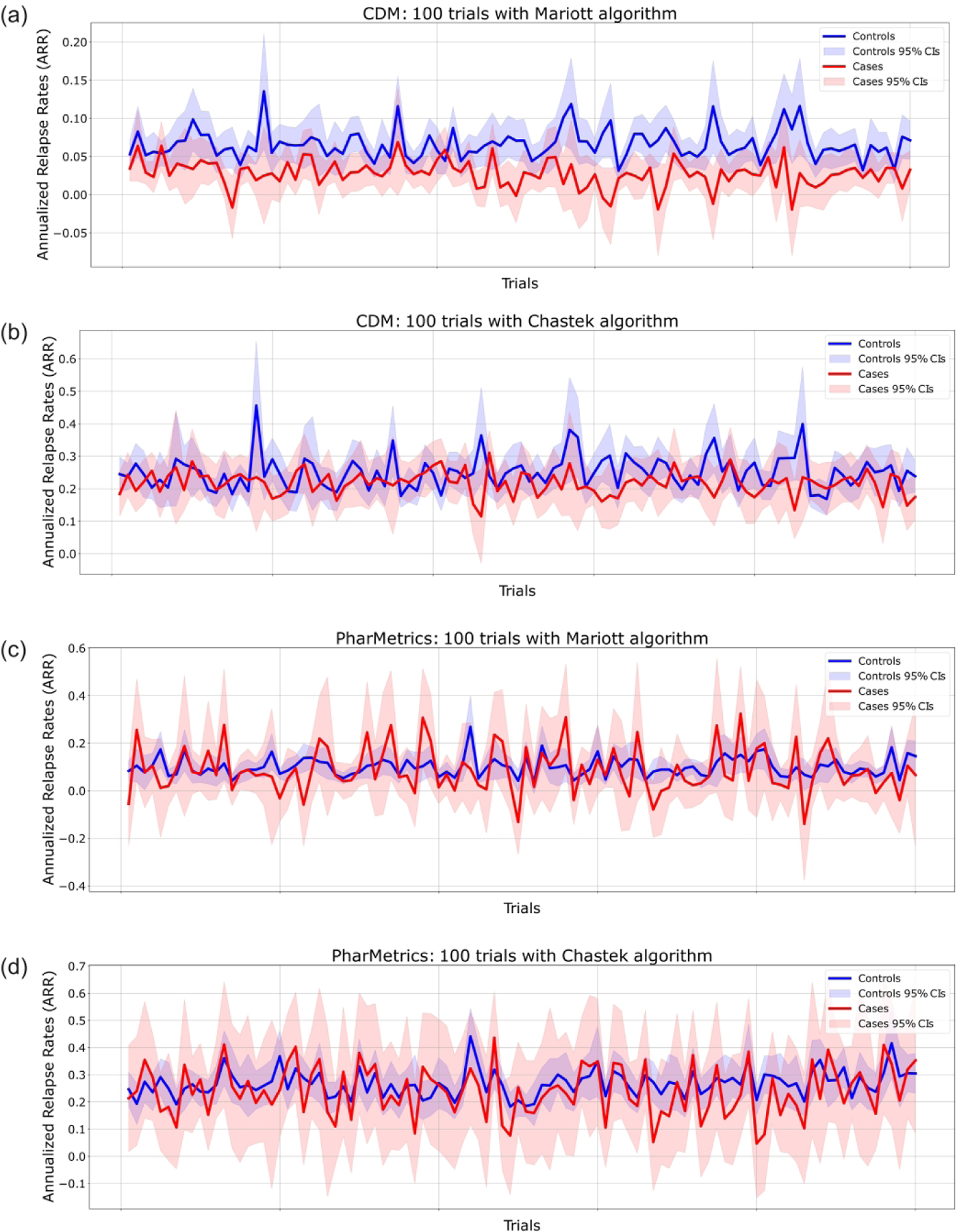

Figure 3 shows the average number of MS relapses if all the patients were on montelukast and the counterfactual (if none of the patients were on montelukast) across the two datasets and with two algorithms for relapse identification (Marriott and Chastek). The 95% confidence intervals from bootstrapping data are also shown in Figure 3. Overall, 78.5% of the CDM emulated trials and 56% of PharMetrics Plus for Academics emulated trials resulted in a significantly (p-value < 0.05) smaller number of average relapses in the counterfactual cases when compared to the counterfactual controls. Tables S4 and S5 in Supplementary Materials show the individual association p-values for each emulated trial with CDM dataset, while Tables S6 and S7 in Supplementary Materials display the association p-values for the trials emulated with PharMetrics Plus for Academics.

Figure 3.

Estimated annual relapse rate (ARR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) in all trials. Each of the emulated clinical trials included the same respective cases and censored groups and different randomly sampled controls from the respective potential control groups. In red, cases represent the estimated ARR for MS patients with montelukast treatment. In blue, controls represent the estimated counterfactual ARR for MS patients without montelukast treatment. Bootstrap sampling was performed to calculate the 95% CIs of each trial. (A, B) CDM results are shown. (C, D) PharMetrics Plus for Academics results are shown. (A, C) Each trial represents relapses identified by the Marriott algorithm. (B, D) Each trial represents relapses identified by the Chastek algorithm.

In the CDM dataset, montelukast users demonstrated a substantial 58.3% reduction in Annualized Relapse Rate (ARR) when assessed with the Marriott algorithm, compared to nonusers. Conversely, the reduction was notably lower at 12.9% when employing the Chastek algorithm. Similarly, in the PharMetrics Plus for Academics dataset, montelukast users exhibited a 13.4% reduction in ARR with the Marriott algorithm, and a 9.89% reduction with the Chastek algorithm. Table 2 presents the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of average relapses identified, along with E-value summary statistics.

Table 2.

Average number of relapses and percent reductions in emulated clinical trials.

| Claims Dataset | Clinformatics® Data Mart (CDM) | PharMetrics® Plus for Academics | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Cases | 483 | 301 | ||

| Number of Controls | 1500 | 1000 | ||

| Relapse Identification Algorithm | Marriott et al. | Chastek et al. | Marriott et al. | Chastek et al. |

| Average relapses in cases [95% CI] | 0.055 [0.048, 0.062] | 0.436 [0.422, 0.450] | 0.175 [0.137, 0.213] | 0.483 [0.466, 0.519] |

| Average relapses in controls [95% CI] | 0.132 [0.125, 0.140] | 0.501 [0.480, 0.521] | 0.202 [0.186, 0.217] | 0.536 [0.517, 0.555] |

| Annualized relapse rate (ARR) in cases | 0.028 | 0.218 | 0.087 | 0.242 |

| Annualized relapse rate (ARR) in controls | 0.066 | 0.251 | 0.101 | 0.268 |

| Percent Reduction | 58.3% | 12.9% | 13.4% | 9.89% |

| Average E-Value [95% CI] | 5.24 [3.52, 8.97] | 1.86 [1.73, 1.99] | 4.49 [2.58, 6.41] | 2.19 [1.93, 2.46] |

Discussion

Despite recent advances in MS treatment, there remains a need to discover new therapeutic options that can provide better efficacy, safety, and tolerability.4,5 Drug repurposing strategies are a promising approach to discovering new treatment options for complex diseases like MS, as they seek to pinpoint new therapeutic applications for medications already approved by the FDA, with existing safety profiles.29,30 We previously utilized translational bioinformatics methods, which translate genomic and other omics data into clinically useful information, to identify repurposable drug candidates for MS.31,32 The current study evaluates a drug candidate stemming from our previous work, montelukast, which is a widely used LTRA indicated for asthma and allergic rhinitis, for MS treatment using real-world administrative health claims data.

Previous investigations have shown that the use of real-world data, such as administrative health claims data, can aid in the investigation of specific treatments and indications in more representative populations, even when clinical trial evidence is limited.20,33 Using de-identified administrative health claims data, we compared the outcomes of MS patients with montelukast claims to those without montelukast claims. We emulated a total of 400 clinical trials (200 with CDM and 200 with PharMetrics Plus for Academics) with randomized control groups. The multiple trials were designed to include the same cases groups, but differing randomly sampled control groups, due to the small number of cases and large number of controls identified in both datasets. The sex ratio of the identified cohorts aligned with established patterns of MS prevalence, but the racial and ethnic representation in these cohort may indicate an over-representation of non-Hispanic whites. To ensure the robustness and selectivity of our study, the cases group in our study only included individuals with good adherence to montelukast medication. Our study design involved a two-year follow-up period for each patient, which is consistent with the follow-up duration of Phase 2 or Phase 3 clinical trials of the U.S. FDA.34 We utilized the ARR as our primary outcome measures, which is a well-established measure in clinical trials for multiple sclerosis.27

The results showed significant reduction of MS relapses in counterfactual analysis of montelukast treatment in 67.3% of emulated trials. Notably, in the CDM dataset with a larger sample size, the 95% CIs of average relapses identified do not overlap in both algorithms, underscoring the robustness of our findings. This demonstrated substantial evidence for the potential of montelukast to improve outcomes for MS patients, as an add-on therapy. The insignificant trials may be attributed to a number of factors, including limited statistical power due to sample size of cases and large variation in randomly sampled MS control groups. We observed similar overall trends in reduction of relapses for pwMS on montelukast. Notably, our robust average E-values (Table 2) suggested resilience to unmeasured confounding, requiring a confounder to be associated with both montelukast prescription and MS-related admission by a risk ratio between two and five-fold of the ones considered in our study.

Limitations

There are limitations that should be considered when interpreting our findings. The Marriott algorithm achieved good PPV and NPV and also resulted in more substantial difference in outcome between patients using montelukast than those who are not. However, the Chastek algorithm has a PPV of 67.3% and NPV of 70%, which could lead to misclassifications.24 Second, there might exist overlap between the independent datasets, which we were not able to test due to the de-identification guidelines of data use agreements. Moreover, CDM and PharMetrics Plus for Academics claims were heterogeneous, as we observed differences between datasets in the number of relapses estimated in pwMS. Thirdly, while claims data offer valuable insights into medication utilization patterns, it does not offer a definitive measure of patient compliance. The nature of the race variable was uncertain, potentially determined algorithmically. Furthermore, the limited sample sizes hindered a comprehensive assessment of the diverse mechanisms of DMTs. Notably, higher efficacy DMTs, such as rituximab and biosimilars, were underrepresented in our study. Larger samples and specific subgroup analyses will be needed to understand montelukast’s benefits and interactions with DMTs fully. Further research will also be required to establish the most effective dosage regimen in MS. Last, unmeasured or unknown confounders may still contribute to residual confounding, despite efforts to adjust for differences.35 For instance, the inability to measure specific MS phenotypes and the challenge of isolating the standalone effects of montelukast due to concurrent MS DMTs pose methodological limitations. While adjustments enhanced confounder balance, certain factors exhibited imbalance scores above the recommended threshold. Figure S2 and Table S7 show which confounders may still be imbalanced. These imbalances, particularly when substantial, have the potential to significantly affect our results. Future work will involve a comparative analysis of medications used to manage allergic rhinitis or asthma.

Conclusions

Our results provided real-world evidence to drive a drug repurposing strategy for MS, as we observed reduction of MS relapses in pwMS on montelukast. The findings of this study can inform the conduction of clinical trials for the use of montelukast in MS, as they warrant the need for further investigation. This study also showcased the role of innovative biomedical informatics methods in generating data-driven hypotheses, as it contributes to the growing body of evidence supporting the use of real-world data and multi-disciplinary approaches facilitating the discovery of new treatment options.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank members of the Data Service Team at the McWilliams School of Biomedical Informatics, especially Ms. Yujia Zhou and Dr. Judy E Young for technical assistance in the extraction and acquisition of data. We would also like to thank members of the Bioinformatics and Systems Medicine Laboratory (BSML) for valuable discussions.

Funding

Astrid M. Manuel was supported by a training fellowship from the Gulf Coast Consortia, on the NLM Training Program in Biomedical Informatics & Data Science (T15LM007093). Assaf Gottlieb was partially supported by the Alzheimer’s Association award (AARG-NTF-21-847409) and National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants (U01AG070112-01A1 and R01AG066749-01). Zhongming Zhao was partially supported by the NIH grants (R01LM012806 and U01AG079847), and the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas Cancer Genomics Core (CPRIT RP180734). No funders had any role in the design or conduction of this study.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

L.F. has received fees for consultancy and/or advisory board participation from Genentech, Roche, Novartis, Bristol Myers Squibb, EMD Serono, Sanofi, Horizon Therapeutics, and TG Therapeutics; has received honorarium for participation in educational programs from Medscape, Inc, the MS Association of America and Impact Education; has received program sponsorship from EMD Serono and grant support from NIH/NINDS, PCORI, Genentech, and EMD Serono through her institution; currently serves on the Healthcare Advisory Committee of the MS Association of America. Z.Z. received speaker fee from a recent User Group meeting of Illumina, Inc.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed in the current study are not publicly available, as they are subject to the terms of the data use agreement (DUA) that governs the use of the administrative health claims.

References

- 1.Walton C, King R, Rechtman L, et al. Rising prevalence of multiple sclerosis worldwide: Insights from the Atlas of MS, third edition. Mult Scler 2020; 26: 1816–1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lublin FD, Häring DA, Ganjgahi H, et al. How patients with multiple sclerosis acquire disability. Brain 2022; 145: 3147–3161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu Z, Liao Q, Wen H, et al. Disease modifying therapies in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Autoimmun Rev 2021; 20: 102826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manuel AM, Dai Y, Freeman LA, et al. An integrative study of genetic variants with brain tissue expression identifies viral etiology and potential drug targets of multiple sclerosis. Mol Cell Neurosci 2021; 115: 103656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manuel AM, Dai Y, Jia P, et al. A gene regulatory network approach harmonizes genetic and epigenetic signals and reveals repurposable drug candidates for multiple sclerosis. Hum Mol Genet 2023; 32: 998–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dempsey OJ. Leukotriene receptor antagonist therapy. Postgrad Med J 2000; 76: 767–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mallinger J, Wildfeuer A, Mehlber L. Leukotrienes in the cerebrospinal fluid of multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand 1992; 86: 586–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fretland DJ. Potential Role of Prostaglandins and Leukotrienes in Multiple Sclerosis and Experimental Allergic Encephalomyelitis. Prostaglandins Luekot Essent Fatty Acids 1992; 45: 249–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neu IS, Metzger G, Zschocke J, et al. Leukotrienes in patients with clinically active multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand 2002; 105: 63–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mirshafiey A, Jadidi-Niaragh F. Immunopharmacological role of the Leukotriene Receptor Antagonists and inhibitors of leukotrienes generating enzymes in Multiple Sclerosis. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol 2010; 32: 219–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chauhan BF, Ducharme FM. Anti-leukotriene agents compared to inhaled corticosteroids in the management of recurrent and/or chronic asthma in adults and children. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev 2004; 5:CD002314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han B, Zhang YY, Ye ZQ, et al. Montelukast alleviates inflammation in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by altering Th17 differentiation in a mouse model. Immunology 2021; 163: 185–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xiao Y, Zhang Y, Gao YH, et al. A targeted extracellular vesicles loaded with montelukast in the treatment of demyelinating diseases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2022; 594: 31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mansour RM, Ahmed MAE, El-Sahar AE, et al. Montelukast attenuates rotenone-induced microglial activation/p38 MAPK expression in rats: Possible role of its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and antiapoptotic effects. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2018; 358: 76–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gelosa P, Bonfanti E, Castiglioni L, et al. Improvement of fiber connectivity and functional recovery after stroke by montelukast, an available and safe anti-asthmatic drug. Pharmacol Res 2019; 142: 223–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Michael J, Zirknitzer J, Unger MS, et al. The leukotriene receptor antagonist montelukast attenuates neuroinflammation and affects cognition in transgenic 5xfad mice. Int J Mol Sci 2021; 22: 1–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dagenais S, Russo L, Madsen A, et al. Use of Real-World Evidence to Drive Drug Development Strategy and Inform Clinical Trial Design. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2022; 111: 77–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gottlieb A, Yanover C, Cahan A, et al. Estimating the effects of second-line therapy for type 2 diabetes mellitus: Retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 2017; 5: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Culpepper WJ, Marrie RA, Langer-Gould A, et al. Validation of an algorithm for identifying MS cases in administrative health claims datasets. Neurology 2019; 92: E1016–E1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prieto-Merino D, Mulick A, Armstrong C, et al. Estimating proportion of days covered (PDC) using real-world online medicine suppliers’ datasets. J Pharm Policy Pract 2021; 14: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.PQA Adherance Measures, https://www.pqaalliance.org/adherence-measures (2022, accessed 2 June 2023).

- 22.Marriott JJ, Chen H, Fransoo R, Marrie RA. Validation of an algorithm to detect severe MS relapses in administrative health claims. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2018; 19: 134–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chastek BJ, Oleen-Burkey M, Lopez-Bresnahan MV. Medical chart validation of an algorithm for identifying multiple sclerosis relapse in healthcare claims. J Med Econ 2010; 13: 618–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bang H, Robins JM. Doubly robust estimation in missing data and causal inference models. Biometrics 2005; 61: 962–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thompson NR, Fan Y, Dalton JE, Jehi L, Rosenbaum BP, Vadera S, Griffith SD. A new Elixhauser-based comorbidity summary measure to predict in-hospital mortality. Med Care. 2015; 53(4):374–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Inusah S, Sormani MP, Cofield SS, et al. Assessing changes in relapse rates in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2010; 16: 1414–1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res 2011; 46: 399–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.VanderWeele TJ, Ding P. Sensitivity Analysis in Observational Research: Introducing the E-Value. Ann Intern Med. 2017; 167(4):268–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zong N, Wen A, Moon S, et al. Computational drug repurposing based on electronic health records: a scoping review. NPJ Digit Med 2022; 5: 77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parvathaneni V, Kulkarni NS, Muth A, et al. Drug repurposing: a promising tool to accelerate the drug discovery process. Drug Discov Today 2019; 24: 2076–2085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oulas A, Minadakis G, Zachariou M, et al. Systems Bioinformatics: Increasing precision of computational diagnostics and therapeutics through network-based approaches. Brief Bioinform 2019; 20:806–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buchan NS, Rajpal DK, Webster Y, et al. The role of translational bioinformatics in drug discovery. Drug Discov Today 2011; 16:426–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gershman B, Guo DP, Dahabreh IJ. Using observational data for personalized medicine when clinical trial evidence is limited. Fertil Steril 2018; 109: 946–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.The drug development process, Step 3: Clinical Research. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) 2020; 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liang W, Zhao Y, Lee AH. An investigation of the significance of residual confounding effect. Biomed Res Int 2014; 2014:658056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed in the current study are not publicly available, as they are subject to the terms of the data use agreement (DUA) that governs the use of the administrative health claims.