Abstract

Macrophage phagocytosis is critical for the immune response, homeostasis regulation, and tissue repair. This intricate process involves complex changes in cell morphology, cytoskeletal reorganization, and various receptor-ligand interactions controlled by mechanical constraints. However, there is a lack of comprehensive theoretical and computational models that investigate the mechanical process of phagocytosis in the context of cytoskeletal rearrangement. To address this issue, we propose a novel coarse-grained mesoscopic model that integrates a fluid-like cell membrane and a cytoskeletal network to study the dynamic phagocytosis process. The growth of actin filaments results in the formation of long and thin pseudopods, and the initial cytoskeleton can be disassembled upon target entry and reconstructed after phagocytosis. Through dynamic changes in the cytoskeleton, our macrophage model achieves active phagocytosis by forming a phagocytic cup utilizing pseudopods in two distinct ways. We have developed a new algorithm for modifying membrane area to prevent membrane rupture and ensure sufficient surface area during phagocytosis. In addition, the bending modulus, shear stiffness, and cortical tension of the macrophage model are investigated through computation of the axial force for the tubular structure and micropipette aspiration. With this model, we simulate active phagocytosis at the cytoskeletal level and investigate the mechanical process during the dynamic interplay between macrophage and target particles.

Significance

In this study, we investigate the process of active phagocytosis using a novel coarse-grained macrophage model consisting of a fluid-like cell membrane and an underlying cytoskeletal network. We observed that phagocytic cups are generated via pseudopod growth from the cytoskeleton in two distinct ways, which aligns with experimental findings. Furthermore, we developed an innovative membrane area algorithm that maintains membrane integrity and provides additional area for phagocytosis. The mechanical properties of the macrophage model are also investigated and can be predicted and regulated. Overall, the coarse-grained macrophage model permits an integrative and mechanistic characterization of the dynamic phagocytosis process, which is a crucial aspect of an in silico macrophage modeling platform that allows researchers to study macrophage phagocytic activity and assess therapeutic strategies in regenerative medicine.

Introduction

Macrophages are large phagocytic cells distributed in all tissues with diverse functions (1,2,3). As phagocytes, macrophages engulf and degrade threatening pathogens, cellular debris, and damaged extracellular matrix material, called phagocytosis. The phagocytosis process involves complex signaling and cytoskeletal changes, as shown in Fig. 1 (4,5,6,7). During the probing stage, pseudopods and ruffles on the macrophage surface flap around to sense the surrounding environment (8,9,10). Upon contact with a target, receptor-ligand binding occurs and the pseudopod pulls the target onto the macrophage surface. Simultaneously, a signaling cascade is triggered, leading to further receptor recruitment and cytoskeletal rearrangement. A phagocytic cup, driven by the pseudopods, forms and engulfs the target. As the pseudopods extend, the engagement between receptors in the macrophage membrane and ligands on the target increases continuously, while membrane folds and intracellular vesicles provide additional membrane area. Finally, the tips of the pseudopods meet and close the cup, and the phagosome seals and exits the surface membrane. This process involves significant cell shape changes with cytoskeletal remodeling and macrophage-target interactions, which are complex dynamic phenomena that have not been fully elucidated or quantified in previous experimental work.

Figure 1.

Schematics (top, i–iv) and simulations (bottom, a-d) of key steps in phagocytosis. (a) A macrophage extends pseudopods to probe the phagocytic target and pull it toward the membrane surface. (b) An increased number of pseudopods near the target begin to contact the target, forming a phagocytic cup. (c) Pseudopods continue to grow, leading to partial engulfment of the target. (d) The target is fully engulfed and internalized into the macrophage. The phagosome is rendered in red. The schematics of the top row are reproduced with permission from (4). To see this figure in color, go online.

There have been numerous theoretical and computational studies attempting to model the endocytosis process and demonstrate the effect of various factors, such as the mechanical properties of the cell membrane and target particles, the shape and size of the particles, and the adhesion or binding strength (11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19). However, the number of previous models that implement active phagocytosis is limited. Three main ways for generating active phagocytosis are recognized: application of protrusive force/stress, recruitment of actin to the phagocytic edge, and utilization of stochastic fluctuation. Herant et al. conducted a study on neutrophil engulfment of an antibody-coated particle and compared experimental data with finite element results to evaluate several models (20,21). They found that two key mechanical interactions drive phagocytosis: a repulsion between the cytoskeleton and the membrane to form a protrusion and an attraction between the cytoskeleton and the membrane adhering to the target. Based on this work, subsequent research endeavors have developed computational models incorporating both the repulsive and attractive forces. Some of these models also account for actin recruitment to the phagocytic cup and the dynamic adhesion between the target and the cell (22,23,24,25). Francis and Heinrich employed a computational model to simulate cell spreading via adhesion-dominant or protrusion-dominant mechanisms (24). Their comparison with an experiment involving human neutrophils spreading on the substrate coated with different densities of IgG revealed the consistency between the protrusive zipper model and experimental observations. Richard and Endres incorporated a signaling molecule to recruit actin for edge pushing in one- and two-dimensional models, illustrating the shape effect of target particles during phagocytosis (26). In contrast to direct application models of protrusive force or stress, Tollis et al. proposed a stochastic phagocytosis model in which random membrane fluctuations in contact with targets are deemed irreversible, while those not in contact quickly disappear, demonstrating the zipper mechanism of phagocytosis (27).

Most previous models have directly applied a protrusive force to the cell or altered the membrane properties via actin or receptors at the phagocytic cup to realize active phagocytosis. In contrast, changes in the cytoskeletal structure have rarely been considered. Therefore, we develop a two-component macrophage model consisting of a fluid-like membrane and a cytoskeletal network in this work. The outer membrane layer provides the lipid bilayer’s fluidity and the cell’s bending stiffness, while the cytoskeletal network provides the elastic property. We achieve pseudopod formation with actin filament growth from the original cytoskeletal network, as shown in the lower parts of Fig. 1. With multiple pseudopods growing from the macrophage surface, a phagocytic cup can be formed and actively engulf the target particle. At the same time, cytoskeleton disassembly and reconstruction algorithm and fluid-like membrane fusion can help complete the internalization of the target and closure of a phagosome. In addition, a local membrane area modification algorithm is developed to maintain membrane integrity and provide sufficient surface area for phagocytosis, which shows good stability and feasibility in our model. Using this model, we simulate passive and active phagocytosis with cytoskeleton reconstruction to study the mechanical process during phagocytosis.

Materials and methods

Macrophages have a complex structure to perform diverse functions and high plasticity, including a lipid bilayer with an extensive repertoire of receptors, a cytoskeletal network consisting of microfilaments and microtubules, a cell nucleus, intracellular lysosomes and phagosomes, etc. To minimize the computational power cost and fulfill the complex phagocytosis function, we model the inactivated macrophage as a spherical cell with a cell membrane represented by a two-component coarse-grained model consisting of the fluid-like membrane and the cytoskeletal network. This type of membrane structure has been widely employed to simulate the membrane of RBCs under normal (28,29,30,31,32) and diseased conditions (33,34,35,36) (see reviews (37,38,39)). We adopt a combination of the dissipative particle dynamics (DPD) method and the Nosé-Hoover thermostat with an NVT ensemble (maintaining a constant number of beads, volume, and temperature) to serve as the thermostat to control the temperature of the system as used in many mesoscopic studies of blood cells and soft matter (40,41,42,43). Details of the DPD method and the parameters adopted in this work are shown in the supporting material. The code we developed on the basis of LAMMPS are available online, together with the examples of the passive and active phagocytosis simulations (44). In the following subsections, we present the details of our two-component model, the mechanism of pseudopod growth, the membrane area modification algorithm, and the method of cytoskeleton disassembly and reconstruction.

Mesoscopic DPD model of the fluid-like lipid bilayer and cytoskeletal network

We use a meshless fluid-like membrane model (45,46) for the membrane part. As shown in Fig. 2, the coarse-grained membrane beads (light gray) form a monolayer structure. They can diffuse freely on the macrophage surface, achieved by an interparticle interaction consisting of a distance-dependent function and an orientation-dependent function ϕ. A two-branch form is applied for :

| (Equation 1) |

where r is the distance between the membrane beads, and and are the repulsive and attractive branches, respectively. A 4-2 LJ type is adopted for the repulsive potential, instead of the traditional 12-6 type, to ensure the membrane’s fluidity. ε is the energy unit, and is set to 0.23ε in our model to obtain the fluid phase. is the equilibrium distance, set to , where σ is the unit distance. For the attractive branch , we apply a smooth cosine form and the exponent ζ determines the slope and hence the diffusivity of the membrane.

Figure 2.

The macrophage model consists of two components: a fluid-like lipid membrane (light gray) and an elastic cytoskeletal network (blue). A one-particle-thick meshless fluid-like model is employed to represent the membrane, while the cytoskeleton is modeled using a triangular network connected by worm-like chain bonds. Harmonic bonds are applied between the cytoskeleton and transmembrane proteins (rendered in cyan) to connect the two components. The macrophage model in this study assumes a spherical shape with a diameter of 25 ; it consists of 36,102 lipid beads, 3874 transmembrane protein beads embedded in the lipid membrane, and 3874 cytoskeleton beads. To see this figure in color, go online.

With the distance-dependent interaction , we obtain a shallow energy well between the membrane beads and maintain a fluid phase. Nevertheless, an angular constraint is necessary to obtain a stable monolayer structure. Therefore, we apply an ellipsoid style to the membrane beads in our model so that they have particle orientations and add the orientation-dependent function ϕ to the total potential (47,48):

| (Equation 2) |

with taking the form:

| (Equation 3) |

| (Equation 4) |

where and are unit vectors along the orientations of two membrane beads. is the vector between bead i and j, where . determines the bending stiffness of the membrane in association with ε, and we obtain the relationship between ε and the corresponding bending stiffness by measuring the axial force of a tubular membrane structure, as shown in the supporting material (49,50). is the spontaneous angle between the membrane beads, and we set it to 0 in our model. When the orientations of the beads i and j are the same and perpendicular to , a reaches its maximum of one and the total potential U is the lowest. This allows us to obtain a monolayer membrane with the desired bending stiffness and fluidity by applying the distance and orientation-dependent interaction.

The phagocytosis process involves a complex rearrangement of the cytoskeleton. We can simulate the passive phagocytosis process with the fluid-like membrane model, but active phagocytosis involving cytoskeletal rearrangement and pseudopod growth cannot be fully reproduced. Therefore, we incorporate the actin filament cytoskeleton into our model, as shown by the blue beads in Fig. 2. We apply a simple triangular network, which has been widely used in previous cell models. The cytoskeleton beads are connected by the combined bond of a worm-like chain (WLC) spring and a power (POW) function (51,52,53). The potential of the WLC-POW bond takes the form:

| (Equation 5) |

where is the current bond length of the WLC spring i, is the maximum length, and their ratio is . p represent the persistence length, and n is an exponent of the power function. The shear modulus of the cytoskeletal network can be obtained with the virial theorem:

| (Equation 6) |

where is the equilibrium length of the spring and = . In our previous work, we typically combined this WLC-POW bond with area, volume, and angle constraints on the spectrin network to build a cell model for which the shear and bending modulus, area and volume compressive modulus, and viscosity can be well described. For our two-component model in this work, the bending stiffness, area, and volume conservation and viscosity are provided by the outer fluid-like membrane, so the corresponding constraints are not applied to the cytoskeletal network. An exception is when we simulate the micropipette aspiration test as shown in Fig. 7; the constraints on the cell area and volume are applied because the relatively large aspiration pressure is applied to the cytoskeleton. The area and volume constraints provided by the membrane are insufficient to maintain the cytoskeleton’s area and volume.

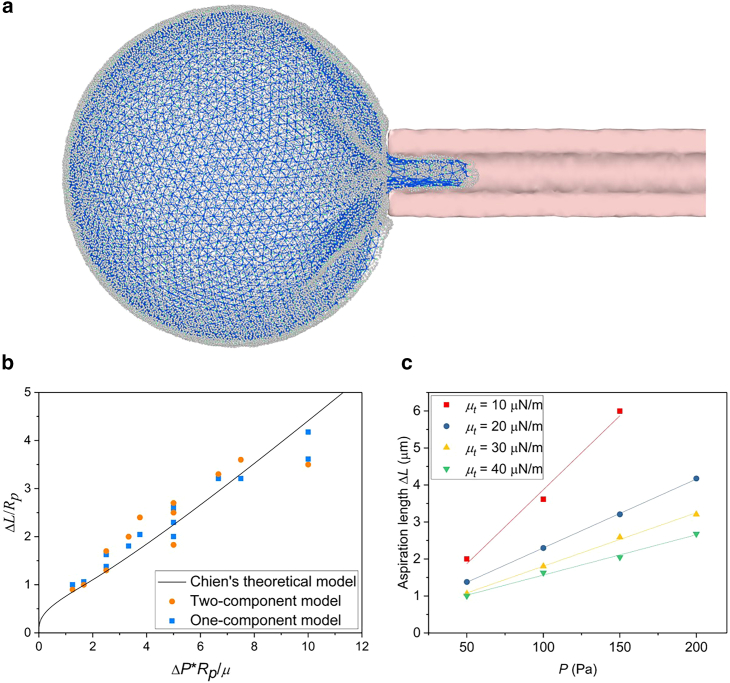

Figure 7.

Micropipette aspiration simulation for evaluating the shear modulus of the macrophage model. (a) Simulations are designed to mimic micropipette aspiration experiments for assessing the shear modulus of the macrophage model. Constant pressure is applied inside the micropipette (rendered in pink) to aspirate a part of the macrophage into the tube. (b) Comparisons among the simulation results of the proposed two-component model, the previous one-component model (52) and Chien’s theoretical model (87). (c) The relationship between the applied pressure and the aspiration length. To see this figure in color, go online.

The actin filaments are anchored underneath the lipid bilayer with CD44 proteins, which connect to the cytoskeletal network via ezrin or directly attach to the membrane with ERM proteins (54,55,56). In our model, some membrane beads are assumed to be transmembrane proteins (cyan beads in Fig. 2) and are connected to the cytoskeleton beads by harmonic bonds:

| (Equation 7) |

where is the bond stiffness and is the equilibrium bond length. In the following sections, we use a macrophage model with a diameter of , which contains 36,102 lipid beads, 3874 protein beads, and 3874 corresponding cytoskeleton beads. The average equilibrium length of the WLC-POW bonds representing cytoskeletons is set to 750 nm. With the combination of the fluid-like membrane and the cytoskeletal network, our model can accurately describe the mechanical properties of macrophages and perform complex functions, as shown in the following sections.

Pseudopod growth modeling

Long and thin pseudopods are actively involved in the whole phagocytosis process and their length can even reach the size of the macrophage (57,58,59). We try to induce protrusions with active protrusive force applied to the macrophage and curved proteins, as in the previous work of Sadhu etal. (25). Still, the length and diameter of the pseudopod are limited. Moreover, pseudopod formation is mediated by actin polymerization and local ruffle formation, not by a pulling force outwards the cell. Therefore, in our two-component model, the pseudopods are propelled by the growth of actin from the original cytoskeletal network, as shown in Fig. 3 and Video S1. Inspired by the formation of long and stable tubes by adhesion in the work of Šarić et al. (60), we apply the Morse potential between the actin filament beads (yellow in Fig. 3 and Video S1) and membrane beads (light gray) (61):

| (Equation 8) |

where and α define the depth and width of the energy well. Alternatively, the dynamic bond formation/dissociation model can also be used to represent a ligand-receptor connection and exhibits a similar effect compared with the Morse potential (62,63,64). With the connection between the membrane and the newly generated filament, we can get pseudopods with a length that can reach the diameter of the macrophage with high stability. Fig. 3 a shows that 23 pseudopods grow out from the surface of the macrophage.

Figure 3.

Computational algorithms for regulating the growth and retraction of pseudopods. (a) Twenty-three pseudopods are generated on an activated macrophage surface; the length of the pseudopods can reach a maximum of without rupturing the lipid membrane. (b–e) The growth process of pseudopods from the macrophage surface: (b) the initial stage; (c) new pseudopod beads (rendered in blue) are inserted between the transmembrane proteins and the cytoskeleton beads, and the bonds connected to the transmembrane beads are removed. (d) From the fourth pseudopod bead, Morse potential is applied between the newly added beads (rendered in yellow) and the lipid membrane beads to ensure their connection and form a long tubular structure. (e) More beads are inserted to support the growing pseudopods. Retraction of a pseudopod is realized by reversing the process of (b–e). The growth and retraction process of a pseudopod is shown in Video S1. To see this figure in color, go online.

The generated pseudopod flaps around and captures a target particle. Newly inserted filament beads adhering to the membrane are rendered in yellow.

Pseudopod growth is accomplished by inserting new pseudopod beads into the original structure, as shown in the detailed process in Fig. 3, b–e. As a pseudopod grows from a site on the membrane surface, a new bead is added between the transmembrane bead (cyan) and the connecting cytoskeleton bead (blue). New bonds are generated between the inserted beads and the cytoskeleton beads, while the original harmonic bonds connecting to the transmembrane beads are removed. With the removal of the bonds, the generation of pseudopods is driven by the repulsive forces in the DPD conservative interactions between the extending actins and the membrane. To control the bending stiffness and maintain the stability of the pseudopod, two types of angle constraints are implemented: the first type is applied between the two new bonds with an equilibrium angle of while the second type is imposed between the new bond and the original cytoskeleton bond with an equilibrium angle of . In addition, the angle constraints are enforced on the transmembrane beads to ensure their positioning at the apex of the pseudopods and prevent membrane rupture. As the pseudopod grows, more beads are gradually inserted into the filament, as shown in Fig. 3, d and e. Starting with the fourth new bead, a Morse potential is applied between the filament and the membrane beads. We do not connect the first three filament beads to the membrane because this would cause the membrane beads to be attracted to the root of the pseudopod and lead to rupture. A long and stable pseudopod is generated as the filament beads and angle constraints are gradually added to the model.

In our model, pseudopods do not only grow out but also retract and return to the initial state. The retraction process is just the reverse order of the growth process, which means that the filament beads and angle constraints are gradually removed from the model, and the length of the pseudopod continues to decrease. The angle constraints applied to the transmembrane beads are removed during this process because it is no longer essential for the transmembrane beads to be at the top of the pseudopods. When the last filament bead is removed, the macrophage will reach the initial state, as shown in Fig. 3, b–e. With the growth and retraction of pseudopods, our macrophage model can realize the function of probing, grabbing, and phagocytosis of the macrophage.

Cytoskeleton disassembly and reconstruction

In addition to the pseudopod formation, the disassembly and reconstruction of the cytoskeleton are also vital in the phagocytosis process. During passive and active phagocytosis, F-actins at the base of the phagocytic cup disassemble to facilitate target entry and exocytic endomembrane delivery (65,66,67,68,69). After the phagocytosis, experimental observations demonstrate the intact cytoskeletal network, indicating actin reconstruction (70,71). To facilitate target entry into the macrophage and restore the integrity of the cytoskeleton, we design a break-reconnect algorithm as illustrated in Fig. 4. Initially, the triangular cytoskeletal network is intact, as shown in Fig. 4 d1. A number of free cytoskeleton beads with their concomitant transmembrane protein beads are distributed on the macrophage surface, serving as a reservoir for cytoskeleton reconnection. Before conducting the simulation, we recorded the number of WLC-POW bonds for each cytoskeleton bead (with most having six bonds, while others have five or seven) for later reconstruction. As the target (depicted by the brown circle) moves closer to the macrophage, the connected cytoskeleton bead will break all of its WLC-POW bonds if a transmembrane bead is within the cutoff distance (indicated by the red dashed circle in Fig. 4 a). This is illustrated in Fig. 4, a2 and d2. As the target’s wrapping degree increases, its surrounding cytoskeletons disassemble, allowing for complete phagocytosis.

Figure 4.

Schematics (a–c) and simulations (d) of cytoskeleton disassembly and reconstruction. (a) Algorithm for controlling the cytoskeleton disassembly and reconstruction. When the distance between a transmembrane protein and the target is shorter than the cutoff distance (indicated by the red dashed circle in a1 and a2), the WLC-POW bonds pertaining to the cytoskeleton bead that connects to the transmembrane protein will be deleted, enabling the target to penetrate through the cytoskeleton. After the target is fully internalized, the cytoskeletal network will reconnect, and the void will be repaired. The green bonds represent the newly generated WLC-POW bonds during the network reconstruction. (b–c) Two ways to reconnect WLC-POW bonds in the cytoskeleton reconstruction algorithm. We loop over the cytoskeleton beads to find a bead i whose WLC-POW bond count is equal to its initial value, and the bond counts of two adjacent beads m and n to which bead i are connected are less than their initial values. If there is no cytoskeleton bond between beads m and n, a new WLC-POW bond will connect them, as illustrated in (b). Otherwise, a free cytoskeleton bead j will be located and connected to beads m and n, as illustrated in (c). (d) Cytoskeleton changes during the phagocytosis process. Initially, the cytoskeletal network (d1) is intact, and some free cytoskeleton beads (connected to transmembrane beads that are not presented here for clarity) are randomly distributed on the macrophage surface. The cytoskeletal network disassembles upon the target’s approach (from d1 to d2), followed by gradual reconnection and reversion to the complete state (from d2 to d6). To see this figure in color, go online.

After the target is internalized, the reconstruction stage commences and new cytoskeleton bonds (green bonds in Fig. 4, a3, b, and c) are created to repair the void in the network. First, we loop over the cytoskeleton beads to identify a specific condition: the number of WLC-POW bonds on a bead i equals its initial recorded bond count, while the bond counts of two adjacent beads m and n connected to bead i are less than their initial counts, as shown in Fig. 4 b and c. If there are no cytoskeleton bonds between bead m and n, then a new bond (green bond in Fig. 4 b) is created between them. Otherwise, we locate a free cytoskeleton bead, denoted as j, in the vicinity of the position , wherein denotes the position of bead i, and are the vectors from bead i to beads m and n, respectively, and is the equilibrium length for new bonds, which is set to the average bond length of all the WLC-POW bonds in the initial configuration. If a free cytoskeleton bead j is found within the distance of from the expected position , new cytoskeletons will be created between j and m, n (green bonds in Fig. 4 c). In a simulation step, only one reconnecting action is performed to prevent the error of selecting a free bead multiple times simultaneously. By following these two ways to reconnect cytoskeleton beads, the void induced by the entry of the target will be gradually reduced and eventually disappear, restoring the integrity of the cytoskeletal network, as shown by Fig. 4, d2–d6. Guided by this algorithm for disassembling and reconstructing the cytoskeletal network, a passageway can be opened for the internalization of the phagocytic target, followed by the reassembling of the network back to its intact state once the internalization is completed.

Membrane area modification

During the phagocytosis process, macrophages will experience large local deformations, especially at the sites of pseudopod growth. However, since we use a flat and smooth energy function to ensure the fluidity of the membrane beads, the membrane is very likely to rupture under large loads. In addition, the local membrane area of the macrophage continues to increase due to the formation of pseudopods and the envelope of the target. Since the plasma membrane is nearly inextensible (72), additional membrane area supplements are gained by the flattening of the folds in the plasma membrane and the exocytosis of intracellular vesicles (73,74,75,76,77,78). To maintain the integrity of the membrane and provide sufficient surface area for the phagocytosis process, we develop a membrane modification algorithm as shown in Fig. 5. This local area-increasing algorithm aims to insert new membrane beads (green) at the rupture sites when the strains are too large. During the ongoing simulation, each pair of nearby membrane beads is checked to see if a new bead k should be added between them. We call the tested pair of membrane beads i and j “parent beads”, and several critical conditions must be satisfied for them:

-

1

) First, we should make sure that the local strain is too large and a rupture occurs, i.e., the distance between the beads i and j should be long enough:

| (Equation 9) |

where is the cutoff of the neighbor list and is the critical distance for a rupture, which we set to 3.6 and 2.0 in our model, respectively. Also, a rupture means no other membrane beads exist in the space between beads i and j. We assume that this space is an ellipsoid with its center at the position of the potential new bead k, which is also the midpoint between beads i and j. The long axis of the ellipsoid is along the direction of the vector from i to j, and the length is , while the length of the short axis is set to . Thus, all nearby membrane beads m should satisfy the following:

| (Equation 10) |

where is the projection length of along , and is the length of vector .

-

2

) Although in Eqs. 9 and 10 there are no membrane beads between beads i and j, the membrane may not be along the direction of . During our testing, we found that new beads may be erroneously added inside the tube when there is a skinny membrane tube with a large curvature (e.g., the pseudopod in Fig. 3). Therefore, we should also ensure no beads between beads i and j in the membrane. We determine the membrane surface with the Bézier curve, widely used in computer-aided geometric design and computer graphics (79). We apply a Bézier curve with two control points p and q, whose positions and are taken as:

| (Equation 11) |

| (Equation 12) |

where and are the positions of the parent beads i and j, respectively, and is the orientation of the potential new bead k, which is set to . and are the unit vectors from beads i to j and from j to i. With these two control points, we can obtain a Bézier curve that is perpendicular to and at both ends and approaches the membrane surface:

| (Equation 13) |

With the estimated membrane surface, we can set a condition that no other membrane beads should be near the midpoint of the Bézier curve, as shown in Fig. 5 c:

| (Equation 14) |

where is the critical distance. We set it to 1.1 in our model.

-

3

) If the nearby parent beads are on the same membrane surface, the angle between the parent beads cannot be too large, as shown in Fig. 5 d. We take the function a in Eq. 4 to evaluate the orientations and set to 0:

| (Equation 15) |

where is the critical value for a. We set it to 0.4.

-

4

) Condition 3 can ensure that the orientations of i and j are sufficiently small, but the parent beads must also be on the membrane surface. During the simulation, some membrane beads may leave the surface and a new bead may be inadvertently added between two wandering beads. Therefore, we must ensure that the parent beads i and j, along with the new bead k, should all be on the surface. The judgment for bead n (n is one of i, j, and k) is made in two steps, as shown in Fig. 5 e. First, there should be at least two beads other than i, j, and k within the cutoff distance for bead n; second, the average orientation-dependent function a weighted with between n and nearby beads should be sufficiently small:

| (Equation 16) |

where l is the nearby beads within the cutoff distance from bead n, and is the critical value for the average a to determine if a bead is in the membrane surface.

Figure 5.

Computational algorithms for regulating local membrane area to prevent lipid membrane rupture. (a) Once a rupture occurs on the membrane surface, new membrane beads (green) are inserted into the rupture sites if the following prerequisites are satisfied, including (b) the distance between the two parent beads i and j is sufficiently long (); (c) no beads are present between the two parent beads; (d) the angle between the orientations of the two parent beads is sufficiently small (); (e) the parent beads i and j and the newly added bead k must be on the membrane surface. The dashed line denotes the cutoff distance used to calculate the counts of the surrounding beads and the average orientation-dependent function a. To see this figure in color, go online.

If all the above conditions are satisfied, a new membrane bead k will be added at the midpoint of i and j, and the orientation is also set along the direction of . To evaluate the stability of the method and determine the optimal parameters mentioned above, we analyze the number of free membrane beads generated during the phagocytosis process across different parameter sets. This evaluation is detailed in the “evaluation of membrane modification parameters” section of the supporting material. Under the optimal parameter set, the number of membrane beads detached from the surface of the macrophage is negligible and has little impact on phagocytosis. With the membrane area modification algorithm, we can avoid ruptures under large deformation and provide sufficient local membrane area to complete the phagocytosis process. The simulation results obtained through this method are shown in the results and discussion. We also quantify the changes in the macrophage surface area during the passive and active phagocytosis processes and compare them with relevant experimental data (80,81,82,83,84), which can be found in the supporting material.

Results and discussion

Probing and trapping functions

First, we investigate the probing and trapping functions of the macrophage and examine the effect of the membrane area modification algorithm, as shown in Fig. 6. A pseudopod grows from the surface of the membrane, forming a long protrusion outwards the cell. We can see from Fig. 6 a that, without the local area modification, there would be a rupture at the root of the pseudopod shortly after the growth. As the pseudopod gets longer, the rupture expands and breaks up at the top. As the pseudopod begins to retract, the rupture remains on the membrane surface even after the pseudopod has wholly disappeared. On the contrary, when we apply the area modification algorithm to the macrophage model, the membrane remains intact during the protrusive process, as shown in Fig. 6 b and Video S1. The actin filament rises from the original cytoskeletal network. The connection between filament beads (yellow) and membrane beads (light gray) induces a long, thin tube to probe the surrounding environment. We apply the Morse potential between the membrane beads and the target particle (brown) so that, when the swinging pseudopod contacts the target, an adhesion will be generated between them. As the pseudopod gradually retracts, the target particle will be returned to the membrane surface and prepared for the incoming phagocytosis. By comparing these two cases, we can see that the membrane area modification algorithm successfully avoids the occurrence of ruptures during the pseudopod formation and helps to complete the whole grabbing process. Therefore, applying this algorithm to our model is essential, and the results presented in the following sections are all obtained using this algorithm. With the pseudopod growth and retraction process and the area modification algorithm, our macrophage model fulfills the probing and grabbing function, which is important in phagocytosis.

Figure 6.

The role of the local membrane area modification algorithm in modeling the extension and retraction of the pseudopods. (a) Pseudopod growth without applying the area modification algorithm leads to rupture of the fluid-like membrane. After the pseudopod is retracted, the rupture remains on the surface. (b) With the application of the area modification algorithm, the lipid membrane remains intact in the extension, interaction with the target, and subsequent retraction, pulling the target particle toward the macrophage. A video clip can be found in Video S1. To see this figure in color, go online.

Micropipette aspiration

In addition, the bending stiffness can be estimated with the axial force of a tubular membrane, and the shear modulus and cortical tension, which are also important factors in the mechanical process of phagocytosis, can also be obtained with the micropipette aspiration with the computational model, as shown in Figs. 7 and S2 (85,86). A micropipette (pink) with a radius of is placed near the macrophage and a constant pressure P is applied in the tube. The pressure in our simulation is achieved by applying a constant force to all cytoskeletal beads aspirated into the tube as a sum force. Membrane beads are not included because they assemble to a meshless fluid structure, and applying force to them may result in membrane rupture. Due to the high coarse-grained level and relatively large length scale in our DPD model, it requires weak interaction between the meshless membrane beads to ensure fluidity, which leads to the fragility and lack of incompressibility in the membrane layer. Moreover, in our model, the shear modulus and the cortical tension are mainly provided by the cytoskeleton. Neglecting membrane beads has little influence on the results of micropipette aspiration (e.g., the comparison between the two-component model and one-component model in Fig. 7 b). A bounce-back boundary condition is adopted between the micropipette and the cytoskeleton to avoid possible superposition. We can see from Fig. 7 a that part of the macrophage enters the micropipette and exhibits a combination of a cylinder and a hemisphere, with shrinkage produced outside the micropipette. We can obtain the shear modulus μ of the macrophage from the micropipette radius , aspiration length and pressure P using the theoretical model developed by Chien et al. (87):

| (Equation 17) |

We set different theoretical shear modulus in Eq. 6 for macrophages and applied various pressure values to obtain different deformations and aspiration lengths. Then we compare our simulation results with the two-component model (blue points) and previous one-component spectrin model results (orange points) with the theory of Chien et al. (black line) and find that they fit quite well, as shown in Fig. 7 b (52,87). The relationship between aspiration length and pressure is shown in Fig. 7 c, from which we can obtain the estimated shear moduli μ = 10.60, 21.92, 28.83, and with Eq. (17) when the theoretical moduli are set to = 10, 20, 30, and , which are in good agreement with experimental values (88,89,90). Furthermore, the cortical tension can also be estimated by obtaining the required pressure under which the cell forms a hemispherical projection into the micropipette (80,84,86,88). The details of the estimation and the relationship between the cortical tension and the shear stress of the cytoskeleton network are shown in the supporting material. With micropipette aspiration, we accurately compute the macrophage shear modulus as in experiments, and our macrophage model shows good mechanical stability.

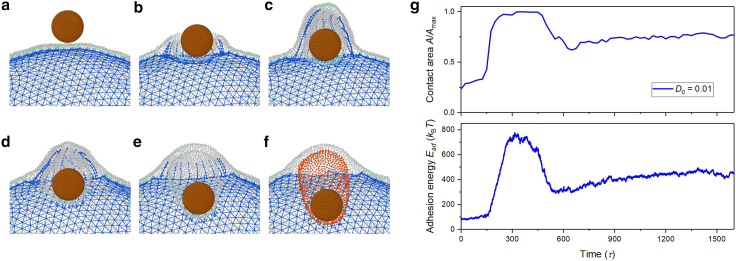

Passive phagocytosis

After validating the pseudopod growth function, the membrane area modification algorithm, and the mechanical properties, we apply the macrophage model to simulate the phagocytosis process. We start with a passive phagocytosis process with no active protrusion, as shown in Fig. 8 and Video S2. Initially, the particle lies on the membrane of the macrophage. Then, we apply an adhesion between them through the Morse potential mentioned in Eq. 8, and the membrane wraps around the particle. To allow the entry of the target, cytoskeletons near the target start to disassemble, as illustrated in Fig. 5 a. With this change in cytoskeletal structure, the target can gradually sink into the macrophage, and the degree of entrapment continues to increase. Eventually, when the target is fully engulfed, membrane fusion will occur, enveloping the target and leading to the formation of the phagosome (colored red in Fig. 8 d). Fig. 8 e shows the changes of the contact area (upper figure) and the adhesion energy (lower figure) between the target and the membrane during the phagocytosis, where is the strength of the applied Morse potential. When (red lines) and the adhesion is too weak, the contact area cannot reach the surface area of the target and the adhesion energy stabilizes at a relatively low level correspondingly. The passive phagocytosis process is incomplete and remains in the stages shown in Fig. 8, b or c. When the adhesion becomes stronger (dark blue and yellow lines), the contact areas increase faster. They can reach a maximum of 1.0, which means that full wrapping is achieved and the phagocytosis is completed. The adhesion energies increase synchronously with the contact areas and stabilize at their maximum. Through the area modification algorithm, the membrane can effectively withstand considerable deformation during engulfment without significant increases in membrane tension when the additional area is introduced. It prevents a substantial increase in adhesion energy demand during phagocytosis, which could otherwise hinder the wrapping process (84,91). Note that, despite the process being a passive evolution without active protrusions, it still incurs energy cost for the cell due to the changes in the cytoskeletal network. With the area modification algorithm and the disassembly of the cytoskeleton, our model can achieve passive phagocytosis and shows the effect of adhesion strength on contact areas, adhesion energies, and internalization speed.

Figure 8.

Passive engulfment of a target particle by a macrophage. (a) Initially, the target particle is on the membrane surface. (b) The macrophage starts to engulf the target under adhesion, while the cytoskeleton near the target disassembles to allow the internalization of the target. (c) The lipid membrane continues to wrap around the target particle as it moves into the macrophage. (d) The target is fully internalized into the macrophage as a phagosome (colored red). (e) Changes in contact area (upper figure) and adhesion energy (lower figure) as a function of simulation time during the passive engulfment. A is the contact area and is the surface area of the target particle. The yellow, blue, and red lines represent the contact areas and the adhesion energies between the macrophage membrane and the target with different adhesion strengths during the passive phagocytosis without protrusion, while the green lines refer to the passive phagocytosis assisted by the active protrusion. A video clip can be found in Video S2. To see this figure in color, go online.

Active phagocytosis

We achieve passive phagocytosis through adhesion between the target and macrophage surface; however, the energy required is higher than the experimental observations (24,92). The minimum adhesion energy required for our passive phagocytosis is around 12,000 , and the surface area of the target is . Assuming that the adhesion is provided by the binding between IgG ligands and Fcγ receptors, with an energy strength of around 14 per bond, the minimum IgG density is around 43.65 molecules per . This density is higher than the requirement for phagocytosis as found in the study conducted by Francis et al. (92). Furthermore, their findings indicate that active protrusion plays a dominant factor that drives the spreading process. Therefore, we introduce active forces into our macrophage model to simulate the active phagocytosis driven by protrusive forces (20,21,22,23,24,25,93,94). Once the target approaches the macrophage and the surrounding cytoskeletons disassemble, we apply active protrusive forces on the cytoskeleton beads located at the edge of the disassembled area, as illustrated in Fig. 9 a. The bonds between the transmembrane proteins and the cytoskeleton beads at the edge will be removed, allowing the protrusive cytoskeleton to push the membrane. To prevent the separation between the cytoskeleton and membrane, protrusive forces are also applied to the membrane beads m near the cytoskeleton beads based on the distances between them. Specifically, the forces of are applied, where is the distance between them, and is the cutoff distance of the fluid membrane interactions. To prevent the macrophage from translating, opposite forces are applied to the entire macrophage to counterbalance the protrusive forces. As a result of the protrusive forces, the macrophage actively deforms and extends toward the target, as shown in Fig. 9 b and Video S3. As the protrusive forces gradually increase, the protrusion length and the wrapping degree increase. After reaching the maximum protrusive force, the macrophage undergoes significant deformation, leading to the complete phagocytosis of the target. Once the target is internalized, the protrusive forces are removed, and the macrophage returns to its initial shape. Before the removal of the protrusive forces, the phagosome will detach from the macrophage surface and accelerate into the cell propelled by the opposite forces acting on the membrane beads on the target surface. The changes in contact area and adhesion energy are shown in the green lines in Fig. 8 e. It is evident that, through the application of active protrusive force, we can use a weaker Morse potential strength to achieve a lower adhesion energy of around 10,000 . As a result, the ligand density estimates at around 36.38 molecules per , which is in proximity to experimental data.

Figure 9.

Active phagocytosis of a target particle is achieved by protrusive force. (a) Schematics of applying protrusive force on the cytoskeleton beads. After the breakage of cytoskeleton bonds, the protrusion forces will be applied at the edge of the void of the cytoskeletal network and the bonds between the transmembrane proteins and the cytoskeleton beads at the edge will break. The protrusion forces will gradually increase and reach their maximum, leading to a progressive deformation. To avoid the separation of the membrane and the cytoskeleton, membrane beads at the protrusive sites are also exerted with associative forces based on the distances between the membrane beads and the cytoskeleton beads. Opposite forces are applied to the entire macrophage to prevent cell translation. (b) Simulations of active phagocytosis process with protrusive forces. The macrophage deforms and reaches out for the target. A phagocytic cup then forms and gradually covers the surface of the target. With the increase of the protrusion forces, the wrapping degree increases and, finally, the target is fully engulfed and internalized. With the withdrawal of the protrusion forces, the macrophage will recover the initial shape. A video clip can be found in Video S3. To see this figure in color, go online.

We then apply the pseudopod growth function to realize active phagocytosis. Two ways of generating pseudopods are adopted: one way is to make a circle of pseudopods around the target particle to grow out and retract, as shown in Fig. 10 and Video S4. The pseudopods around the target rise from the macrophage surface and form a well-shaped phagocytic cup. Due to the membrane fluidity, the pseudopods fuse with surrounding ones, and a lamellar structure forms and covers the target surface gradually. As the pseudopods extend, the cup gradually covers the target and the wrapping degree increases, with the rapid increase of the contact area and adhesion energy between the target and the membrane as shown in Fig. 10 g. Meanwhile, the cytoskeletons around the target disassemble, allowing it to enter. When the pseudopods are long enough, they aggregate and seal the cup opening, and the contact area and adhesion energy reach their maximum. The pseudopods then begin to retract, pushing the target into the cell. During this stage, the gradual detachment of some membrane beads adhered to the target results in a decrease in the contact area and adhesion energy. This phenomenon occurs because the sealed phagocytic cup and the subsequent phagosome typically offer more space than the target volume. To minimize the bending energy of the membrane, the membrane beads detach from the target surface and contribute to the formation of the phagosome, which exhibits a smaller curvature. When the pseudopods are short enough and disappear, the particle is fully internalized and encapsulated by the phagosome (colored red in Fig. 10 f). The contact area and adhesion energy stabilize at values lower than the maximum as the target makes contact with part of the phagosome. Note that the adhesion energy in the active phagocytosis with surrounding pseudopods is over 10-fold smaller compared with passive phagocytosis or active phagocytosis with protrusive forces or random pseudopods. In this process, the adhesion is not the primary factor that facilitates the contact between the target and macrophage; instead, it plays a crucial role in the generation of pseudopods and the formation of the phagocytic cup. The significantly low adhesion energy required for this process indicates that active phagocytosis can be accomplished with very low ligand density on the target surface. Therefore, we apply an adhesion between the transmembrane proteins and the target to make the target remain at the macrophage surface, and a relatively small adhesion between the membrane and the target so the phagocytic cup will not push the target away.

Figure 10.

Active phagocytosis of a target particle is achieved by selected pseudopods from the macrophage membrane. (a) Initially, the target particle is on the membrane surface. (b) Pseudopods around the target begin to grow and form a phagocytic cup while the cytoskeleton around the target starts to disassemble; the pseudopods fuse with surrounding ones, forming a lamellar structure and covering the target surface. (c) The target is wrapped in the phagocytic cup. (d) The pseudopods begin to retract and the target is pushed toward the macrophage. (e) The length of the pseudopods continues to decrease and a phagosome is formed. (f) The pseudopods disappear and the target contained by the phagosome (colored red) is completely phagocytosed. (g) Changes in contact area and adhesion energy as a function of simulation time during the active phagocytosis. The blue lines represent the contact area (upper figure) and adhesion energy (lower figure) between the macrophage membrane and the target, respectively. A video clip can be found in Video S4. To see this figure in color, go online.

Another way to achieve active phagocytosis with our model is by randomly generating pseudopods on the macrophage surface. We set the probability that a pseudopod will grow from the transmembrane protein m in a simple distance-dependent manner to mimic the signaling during phagocytosis:

| (Equation 18) |

where n is each transmembrane bead on the macrophage surface, and and are the distances of the beads m and n from the target, respectively. It is worth noting that the growing sites within the minimum distance are not considered because the pseudopods growing from a site too close to the target will not contribute to forming the phagocytic cup but will push the target away. In our simulation, is set to the cutoff distance. With this probability distribution, pseudopods are most likely to grow from the surrounding sites and adhere to the target surface, as shown in Fig. 11, a–f and Video S5. With pseudopods’ continuous formation and recovery, the contact area between the membrane and the target increases until the fluid-like membrane completely covers the target. The disruption of the cytoskeleton allows the target to be fully phagocytosed. Finally, the target is sealed up in a phagosome (colored red in Fig. 11 f) and internalized into the macrophage. From Fig. 11 g, we can see that the contact area and adhesion energy increase rapidly and stabilize at their maximum during phagocytosis. The required adhesion strength of active phagocytosis is much weaker than that of passive phagocytosis. The internalization speed is faster, demonstrating the effect of active pseudopod and phagocytic cup formation. Compared with the case of selected pseudopods, the adhesion energy is significantly higher when randomly generated pseudopods are involved. This elevated energy level stems from the inability of randomly generated pseudopods to form a well-shaped phagocytic cup. Instead, these pseudopods enhance the phagocytic process by enlarging the contact area between the target and the membrane. Consequently, a comparatively strong adhesion strength remains essential to facilitate the wrapping of the target. Stochastic factors are also investigated by changing the random numbers in the DPD interactions and random pseudopod generation, and the results are similar, as shown in Fig. S6 in the supporting material. With these two ways of generating phagocytic cups, we can further investigate the mechanical process and the effect of various factors during active phagocytosis.

Figure 11.

Active phagocytosis is achieved by randomly generated pseudopods from the macrophage membrane. (a–f) Pseudopods grow and retract on the membrane surface, forming a phagocytic cup and tending to engulf the target. The cytoskeleton around the target disassembles to allow the internalization of the target. With the continuous generation of pseudopods, wrapping keeps increasing, eventually reaching 100. The target is encapsulated in a phagosome (colored red) and completely phagocytosed into the macrophage. The generation of pseudopods is based on the assumption that the probability of forming a pseudopod is greater when the sites are closer to the target. (g) Changes in contact area and adhesion energy as a function of simulation time during the active phagocytosis. The blue lines represent the contact area (upper figure) and adhesion energy (lower figure) between the macrophage membrane and the target, respectively. A video clip can be found in Video S5. To see this figure in color, go online.

There are still several limits and inadequacies in our current phagocytic model that can be further addressed in our future work: 1) the internalization mechanism of our active phagocytosis process involving pseudopods does not align well with experimental observations. In the scenario where the pseudopods extend and the wrapping level around the target reaches a maximum, the cell is expected to round up under the cortical tension, and the newly generated actins would integrate into the cortex. However, our current model exhibits a discrepancy as the cell fails to round up due to the actins’ inability to generate sufficient tension to overcome their bending energy as they are not connected to each other. To address this limitation in our study, we have introduced a retraction function for the pseudopods to initiate target internalization and induce cell surface flattening. In our future work, we will focus on developing a connection function for the pseudopods to establish cortical formation and eliminate the retraction feature. 2) The cytoskeleton reconnection process is not implemented in the phagocytosis simulations due to the hindrance posed by the phagosome’s presence at the phagocytic site. The recovering cytoskeleton may connect to the phagosome and result in disorder. This challenge can be overcome by revising the internalization mechanism, as suggested in the previous discussion. 3) It is historically suggested that phagocytosis is categorized into two types based on the pathway: one is “sinking phagocytosis,” where the target directly sinks into the cell body, similar to passive phagocytosis in our simulations; meanwhile, the other type is the “phagocytic cup formation,” where a phagocytic cup develops with protrusive pseudopods, similar to our active phagocytosis process. It was assumed that complement-mediated phagocytosis corresponds to the “sink-mode,” and antibody-mediated phagocytosis involves the formation of phagocytic cups (91,95,96,97). However, the supporting evidence is lacking, and the precise mechanism remains unclear. Several studies have documented instances where complement-opsonized targets were phagocytosed with the formation of phagocytic cups (10,98,99). In our future study, we intend to integrate different types of ligands into our macrophage model and explore the mechanisms and efficacy of these two types of phagocytosis. 4) When the adhesion energy density required for phagocytosis reaches a significantly low level, as depicted in Fig. 10 g), the discrete nature of adhesion sites will play an important role in the phagocytic process, as highlighted in previous studies (24,100). Currently, our model applies adhesion uniformly to both the target and membrane beads. In our forthcoming research, we plan to introduce adhesion to a subset of the target beads (considered discrete ligands) and the membrane beads (considered discrete receptors).

Conclusion

In this study, we have developed a two-component macrophage model to investigate the phagocytosis process at the subcellular level in silico. We use the orientation-dependent interparticle potential to attain fluidity and bending stiffness. We integrate it with a cytoskeletal network connected by WLC-POW links to accurately characterize the cell membrane’s shear modulus. We estimate shear stiffness, cortical tension, and bending modulus using micropipette aspiration and axial force on the tubular membrane. Subsequently, after determining the mechanical properties of our model, we developed the pseudopod growth function essential for phagocytosis. With the generation of actin filaments from the cytoskeletal network, long and thin pseudopods are formed from the cell membrane surface. The algorithm for cytoskeleton disassembly and reconstruction has also been designed to facilitate target entry and maintain the completeness of the cytoskeletal network after phagocytosis. In our model’s development, we found that the fluid-like membrane is susceptible to rupture under high strain and that target internalization and phagosome formation require additional surface membrane area. As a result, we propose an algorithm for local membrane area modification that can insert new membrane beads when a rupture is imminent. This approach allows the membrane to remain intact even when subjected to substantial deformations, such as long protrusions, thereby providing an adequate membrane reservoir for phagocytosis. An optimal set of modification parameters was obtained by assessing the number of free membrane beads during the simulations.

We have successfully implemented passive phagocytosis and active phagocytosis processes using the pseudopod growth function and the area modification algoritham. In passive phagocytosis without protrusion, the membrane gradually surrounds the target through adhesion and can be completely engulfed with adequate adhesion. The model also incorporated active protrusive force to simulate passive phagocytosis driven by protrusions. Furthermore, we have developed two different methods to generate pseudopods for the formation of phagocytic cups in active phagocytosis. These methods involve actively enveloping the target particle with growing pseudopods, resulting in a rapid increase in the contact area and adhesion energy to the maximum levels. Following the retraction of the pseudopods, the target particle can be internalized to form an intracellular phagosome. With this model, we can examine changes to the cytoskeleton, increases in membrane area, and morphological alterations in cells and targets, as well as the impact of multiple factors and mechanical responses during active phagocytosis. These findings could potentially enhance our understanding of immune-related diseases and aid in the development of drug platforms.

Author contributions

S.W., X.L., and G.E.K. designed the research. S.W. carried out all simulations, S.W., S.M., H.L., M.D., X.L., and G.E.K. analyzed the data. X.L. supervised the project. All authors contributed to editing the manuscript and providing fruitful discussions and feedback.

Acknowledgments

S.W., S.M., and X.L. acknowledge support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 12372265). H.L, M.D., and G.E.K. acknowledge partial support from the National Institutes of Health (grant no. R01HL154150). S.W. and S.M. thank Dr. Guansheng Li for discussing the macrophage model. Simulations were carried out at the Beijing Super Cloud Computing Center.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Editor: Padmini Rangamani.

Footnotes

Supporting material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2024.03.026.

Supporting material

References

- 1.Wynn T.A., Chawla A., Pollard J.W. Macrophage biology in development, homeostasis and disease. Nature. 2013;496:445–455. doi: 10.1038/nature12034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mosser D.M., Edwards J.P. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:958–969. doi: 10.1038/nri2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Italiani P., Boraschi D. From monocytes to M1/M2 macrophages: phenotypical vs. functional differentiation. Front. Immunol. 2014;5:514. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Botelho R.J., Grinstein S. Phagocytosis. Curr. Biol. 2011;21:R533–R538. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freeman S.A., Grinstein S. Phagocytosis: receptors, signal integration, and the cytoskeleton. Immunol. Rev. 2014;262:193–215. doi: 10.1111/imr.12212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaumouillé V., Waterman C.M. Physical constraints and forces involved in phagocytosis. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:1097. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jain N., Moeller J., Vogel V. Mechanobiology of macrophages: how physical factors coregulate macrophage plasticity and phagocytosis. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2019;21:267–297. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-062117-121224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kress H., Stelzer E.H.K., et al. Rohrbach A. Filopodia act as phagocytic tentacles and pull with discrete steps and a load-dependent velocity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:11633–11638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702449104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vonna L., Wiedemann A., et al. Sackmann E. Micromechanics of filopodia mediated capture of pathogens by macrophages. Eur. Biophys. J. 2007;36:145–151. doi: 10.1007/s00249-006-0118-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel P.C., Harrison R.E. Membrane ruffles capture C3bi-opsonized particles in activated macrophages. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2008;19:4628–4639. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-02-0223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao H., Shi W., Freund L.B. Mechanics of receptor-mediated endocytosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:9469–9474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503879102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun S.X., Wirtz D. Mechanics of enveloped virus entry into host cells. Biophys. J. 2006;90:L10–L12. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.074203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tzlil S., Deserno M., et al. Ben-Shaul A. A statistical-thermodynamic model of viral budding. Biophys. J. 2004;86:2037–2048. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74265-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Effenterre D.v., Roux D. Adhesion of colloids on a cell surface in competition for mobile receptors. Europhys. Lett. 2003;64:543–549. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yi X., Shi X., Gao H. Cellular uptake of elastic nanoparticles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011;107 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.098101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang T., Sknepnek R., et al. Schwarz J.M. On the modeling of endocytosis in yeast. Biophys. J. 2015;108:508–519. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.11.3481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dasgupta S., Auth T., Gompper G. Wrapping of ellipsoidal nano-particles by fluid membranes. Soft Matter. 2013;9:5473–5482. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dasgupta S., Auth T., Gompper G. Shape and orientation matter for the cellular uptake of nonspherical particles. Nano Lett. 2014;14:687–693. doi: 10.1021/nl403949h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang S., Gao H., Bao G. Physical principles of nanoparticle cellular endocytosis. ACS Nano. 2015;9:8655–8671. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b03184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herant M., Heinrich V., Dembo M. Mechanics of neutrophil phagocytosis: experiments and quantitative models. J. Cell Sci. 2006;119:1903–1913. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herant M., Lee C.-Y., et al. Heinrich V. Protrusive push versus enveloping embrace: computational model of phagocytosis predicts key regulatory role of cytoskeletal membrane anchors. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2011;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1001068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Zon J.S., Tzircotis G., et al. Howard M. A mechanical bottleneck explains the variation in cup growth during FcγR phagocytosis. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2009;5:298. doi: 10.1038/msb.2009.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DiNapoli K.T., Robinson D.N., Iglesias P.A. A mesoscale mechanical model of cellular interactions. Biophys. J. 2021;120:4905–4917. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2021.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Francis E.A., Heinrich V. Integrative experimental/computational approach establishes active cellular protrusion as the primary driving force of phagocytic spreading by immune cells. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2022;18 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sadhu R.K., Barger S.R., et al. Gov N.S. A theoretical model of efficient phagocytosis driven by curved membrane proteins and active cytoskeleton forces. Soft Matter. 2022;19:31–43. doi: 10.1039/d2sm01152b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richards D.M., Endres R.G. Target shape dependence in a simple model of receptor-mediated endocytosis and phagocytosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:6113–6118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521974113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tollis S., Dart A.E., Endres R.G., et al. The zipper mechanism in phagocytosis: energetic requirements and variability in phagocytic cup shape. BMC Syst. Biol. 2010;4:149. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-4-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li H., Lykotrafitis G. Two-component coarse-grained molecular-dynamics model for the human erythrocyte membrane. Biophys. J. 2012;102:75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.11.4012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li H., Lykotrafitis G. Erythrocyte membrane model with explicit description of the lipid bilayer and the spectrin network. Biophys. J. 2014;107:642–653. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang Y.-H., Lu L., et al. Karniadakis G.E. OpenRBC: A fast simulator of red blood cells at protein resolution. Biophys. J. 2017;112:2030–2037. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li H., Yang J., et al. Karniadakis G.E. Cytoskeleton remodeling induces membrane stiffness and stability changes of maturing reticulocytes. Biophys. J. 2018;114:2014–2023. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma S., Wang S., et al. Li X. Multiscale computational framework for predicting viscoelasticity of red blood cells in aging and mechanical fatigue. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2022;391 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li H., Zhang Y., et al. Lykotrafitis G. Modeling of band-3 protein diffusion in the normal and defective red blood cell membrane. Soft Matter. 2016;12:3643–3653. doi: 10.1039/c4sm02201g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang H.-Y., Li X., et al. Karniadakis G.E. MD/DPD multiscale framework for predicting morphology and stresses of red blood cells in health and disease. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2016;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li H., Lu L., et al. Suresh S. Mechanics of diseased red blood cells in human spleen and consequences for hereditary blood disorders. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:9574–9579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1806501115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu L., Li Z., et al. Karniadakis G.E. Quantitative prediction of erythrocyte sickling for the development of advanced sickle cell therapies. Sci. Adv. 2019;5 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aax3905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li H., Papageorgiou D.P., et al. Deng Y. Synergistic integration of laboratory and numerical approaches in studies of the biomechanics of diseased red blood cells. Biosensors. 2018;8:76. doi: 10.3390/bios8030076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li X., Li H., et al. Em Karniadakis G. Computational biomechanics of human red blood cells in hematological disorders. J. Biomech. Eng. 2017;139 doi: 10.1115/1.4035120. 0210081–02100813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Deng Y.-X., Chang H.-Y., Li H. Recent advances in computational modeling of biomechanics and biorheology of red blood cells in diabetes. Biomimetics. 2022;7:15. doi: 10.3390/biomimetics7010015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li G., Ye T., Li X. Parallel modeling of cell suspension flow in complex micro-networks with inflow/outflow boundary conditions. J. Comput. Phys. 2020;401 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yazdani A., Deng Y., et al. Em Karniadakis G. Integrating blood cell mechanics, platelet adhesive dynamics and coagulation cascade for modelling thrombus formation in normal and diabetic blood. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2021;18 doi: 10.1098/rsif.2020.0834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li H., Deng Y., et al. Karniadakis G.E. Computational investigation of blood cell transport in retinal microaneurysms. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2022;18 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li G., Qiang Y., et al. Karniadakis G.E. In silico and in vitro study of the adhesion dynamics of erythrophagocytosis in sickle cell disease. Biophys. J. 2023;122:P2590–P2604. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2023.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang S., Ma S., et al. Karniadakis G.E. Two-component macrophage model. 2024. https://github.com/ShuoWangZJU/Two-Componet-Macrophage-Model [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Yuan H., Huang C., et al. Zhang S. One-particle-thick, solvent-free, coarse-grained model for biological and biomimetic fluid membranes. Phys. Rev. 2010;82 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.82.011905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fu S.-P., Peng Z., et al. Young Y.-N. Lennard-Jones type pair-potential method for coarse-grained lipid bilayer membrane simulations in LAMMPS. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2017;210:193–203. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gay J.G., Berne B.J. Modification of the overlap potential to mimic a linear site–site potential. J. Chem. Phys. 1981;74:3316–3319. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Everaers R., Ejtehadi M.R. Interaction potentials for soft and hard ellipsoids. Phys. Rev. 2003;67 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.67.041710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harmandaris V.A., Deserno M. A novel method for measuring the bending rigidity of model lipid membranes by simulating tethers. J. Chem. Phys. 2006;125 doi: 10.1063/1.2372761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shiba H., Noguchi H. Estimation of the bending rigidity and spontaneous curvature of fluid membranes in simulations. Phys. Rev. 2011;84 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.84.031926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pivkin I.V., Karniadakis G.E. Accurate coarse-grained modeling of red blood cells. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008;101 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.118105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fedosov D.A., Caswell B., Karniadakis G.E. A multiscale red blood cell model with accurate mechanics, rheology, and dynamics. Biophys. J. 2010;98:2215–2225. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peng Z., Li X., et al. Suresh S. Lipid bilayer and cytoskeletal interactions in a red blood cell. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:13356–13361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311827110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Freeman S.A., Vega A., et al. Grinstein S. Transmembrane pickets connect cyto-and pericellular skeletons forming barriers to receptor engagement. Cell. 2018;172:305–317.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roberts R.E., Martin M., et al. Hallett M.B. Ca2+-activated cleavage of ezrin visualised dynamically in living myeloid cells during cell surface area expansion. J. Cell Sci. 2020;133 doi: 10.1242/jcs.236968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fehon R.G., McClatchey A.I., Bretscher A. Organizing the cell cortex: the role of ERM proteins. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010;11:276–287. doi: 10.1038/nrm2866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Diakonova M., Bokoch G., Swanson J.A. Dynamics of cytoskeletal proteins during Fcγ receptor-mediated phagocytosis in macrophages. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2002;13:402–411. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-05-0273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dart A.E., Tollis S., et al. Endres R.G. The motor protein myosin 1G functions in FcγR-mediated phagocytosis. J. Cell Sci. 2012;125:6020–6029. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Qiang Y., Sissoko A., et al. Dao M. Microfluidic study of retention and elimination of abnormal red blood cells by human spleen with implications for sickle cell disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2023;120 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2217607120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Šarić A., Cacciuto A. Mechanism of membrane tube formation induced by adhesive nanocomponents. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012;109 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.188101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Morse P.M. Diatomic molecules according to the wave mechanics. II. Vibrational levels. Phys. Rev. 1929;34:57–64. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hammer D.A., Apte S.M. Simulation of cell rolling and adhesion on surfaces in shear flow: general results and analysis of selectin-mediated neutrophil adhesion. Biophys. J. 1992;63:35–57. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81577-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.King M.R., Hammer D.A. Multiparticle adhesive dynamics: hydrodynamic recruitment of rolling leukocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:14919–14924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261272498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fedosov D.A., Caswell B., Karniadakis G.E. Wall shear stress-based model for adhesive dynamics of red blood cells in malaria. Biophys. J. 2011;100:2084–2093. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kaksonen M., Sun Y., Drubin D.G. A pathway for association of receptors, adaptors, and actin during endocytic internalization. Cell. 2003;115:475–487. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00883-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lacy M.M., Baddeley D., Berro J. Single-molecule turnover dynamics of actin and membrane coat proteins in clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Elife. 2019;8 doi: 10.7554/eLife.52355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lappalainen P., Kotila T., et al. Romet-Lemonne G. Biochemical and mechanical regulation of actin dynamics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022;23:836–852. doi: 10.1038/s41580-022-00508-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Scott C.C., Dobson W., et al. Grinstein S. Phosphatidylinositol-4, 5-bis phosphate hydrolysis directs actin remodeling during phagocytosis. J. Cell Biol. 2005;169:139–149. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200412162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schlam D., Bagshaw R.D., et al. Grinstein S. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase enables phagocytosis of large particles by terminating actin assembly through Rac/Cdc42 GTPase-activating proteins. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8623. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Marie-Anaïs F., Mazzolini J., et al. Niedergang F. Dynamin-actin cross talk contributes to phagosome formation and closure. Traffic. 2016;17:487–499. doi: 10.1111/tra.12386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vorselen D., Barger S.R., et al. Krendel M. Phagocytic ‘teeth’ and myosin-II ‘jaw’ power target constriction during phagocytosis. Elife. 2021;10 doi: 10.7554/eLife.68627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Evans E.A., Waugh R., Melnik L. Elastic area compressibility modulus of red cell membrane. Biophys. J. 1976;16:585–595. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(76)85713-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Petty H.R., Hafeman D.G., McConnell H.M. Disappearance of macrophage surface folds after antibody-dependent phagocytosis. J. Cell Biol. 1981;89:223–229. doi: 10.1083/jcb.89.2.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hirsch J.G., Cohn Z.A. Degranulation of polymorphonuclear leucocytes following phagocytosis of microorganisms. J. Exp. Med. 1960;112:1005–1014. doi: 10.1084/jem.112.6.1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hackam D.J., Rotstein O.D., et al. Grinstein S. v-SNARE-dependent secretion is required for phagocytosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:11691–11696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Braun V., Fraisier V., et al. Niedergang F. TI-VAMP/VAMP7 is required for optimal phagocytosis of opsonised particles in macrophages. EMBO J. 2004;23:4166–4176. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hallett M.B., Dewitt S. Ironing out the wrinkles of neutrophil phagocytosis. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Masters T.A., Pontes B., et al. Gauthier N.C. Plasma membrane tension orchestrates membrane trafficking, cytoskeletal remodeling, and biochemical signaling during phagocytosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:11875–11880. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301766110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bézier P. System Butterworths; London: 1986. The Mathematical Basis of the UNISURF CAD. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Herant M., Heinrich V., Dembo M. Mechanics of neutrophil phagocytosis: behavior of the cortical tension. J. Cell Sci. 2005;118:1789–1797. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lee C.-Y., Thompson G.R., III, et al. Heinrich V. Coccidioides endospores and spherules draw strong chemotactic, adhesive, and phagocytic responses by individual human neutrophils. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Simon S.I., Schmid-Schönbein G.W. Biophysical aspects of microsphere engulfment by human neutrophils. Biophys. J. 1988;53:163–173. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(88)83078-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cannon G.J., Swanson J.A. The macrophage capacity for phagocytosis. J. Cell Sci. 1992;101:907–913. doi: 10.1242/jcs.101.4.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lam J., Herant M., et al. Heinrich V. Baseline mechanical characterization of J774 macrophages. Biophys. J. 2009;96:248–254. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.139154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hochmuth R.M. Micropipette aspiration of living cells. J. Biomech. 2000;33:15–22. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(99)00175-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]