Abstract

Different stress models are employed to enhance our understanding of the underlying mechanisms and explore potential interventions. However, the utility of these models remains a critical concern, as their validities may be limited by the complexity of stress processes. Literature review revealed that both mental and physical stress models possess reasonable construct and criterion validities, respectively reflected in psychometrically assessed stress ratings and in activation of the sympathoadrenal system and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. The findings are less robust, though, in the pharmacological perturbations’ domain, including such agents as adenosine or dobutamine. Likewise, stress models’ convergent- and discriminant validity vary depending on the stressors’ nature. Stress models share similarities, but also have important differences regarding their validities. Specific traits defined by the nature of the stressor stimulus should be taken into consideration when selecting stress models. Doing so can personalize prevention and treatment of stress-related antecedents, its acute processing, and chronic sequelae. Further work is warranted to refine stress models’ validity and customize them so they commensurate diverse populations and circumstances.

Keywords: allostasis, arginine-vasopressin, cortisol, homeostasis, immune, norepinephrine, psychodiagnostic, psychometric, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone

1. Introduction

If You Canť Measure It, You Canť Improve It.

Peter Ferdinand Drucker

The impact of disastrously stressful experiences on well-being is overwhelming and is evident in the atrocities at the southern border of Israel (Rees and Moussa, 2023), the war in Ukraine (Mottola et al., 2023), mass shootings (Lowe and Galea, 2017), the coronavirus pandemic (Whiteman et al., 2023), and economic inflation and downturns (Louie et al., 2023). Maladaptive responses to stress are associated with serious illnesses, including, addictions, allergies, anxiety disorders, autoimmune disorders, chronic fatigue syndrome, hypertension, major depression, metabolic syndrome, pain syndromes, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), psychosis, and infections (Chrousos and Gold, 1992; Elman et al., 1998; Elman and Borsook, 2019; Elman et al., 2006; Gold and Chrousos, 2002; Swaab et al., 2005; Tsigos and Chrousos, 1994). To compound the affront, stress is also an inevitable aspect of day-to-day life in the form of aggravating or unpleasant experiences (Elman et al., 2010).

Acute stress is essential for successful coping and survival by improving performance and avoidance of harm via the "fight-or-flight" type of coping style (Cannon 1915). Normally, the well-orchestrated homeostatic machinery is infallible in the maintenance of equilibrium across body systems and for the stabilization of emotional states and motivational drives during routine stressors (Elman and Borsook, 2016). However, enormous, recurrent, or continuous stresses induce robust and sustained systems' strain that override homeostatic feedback control to generate allostatic adaptations (Elman and Borsook, 2019; Elman et al., 2011). Being unchecked by physiological negative feedback mechanisms, these adaptations lead to an autonomous, self-sustaining feedforward loop, whereby prior exposure to one type of stress increases the subsequent response to itself and to a different type of stress (Elman et al., 2013; Juruena, 2014; Rao and Androulakis, 2019). And so, understanding the mechanisms by which stress affects the mind and body is essential for the development of effective interventions to mitigate stress’ negative impacts.

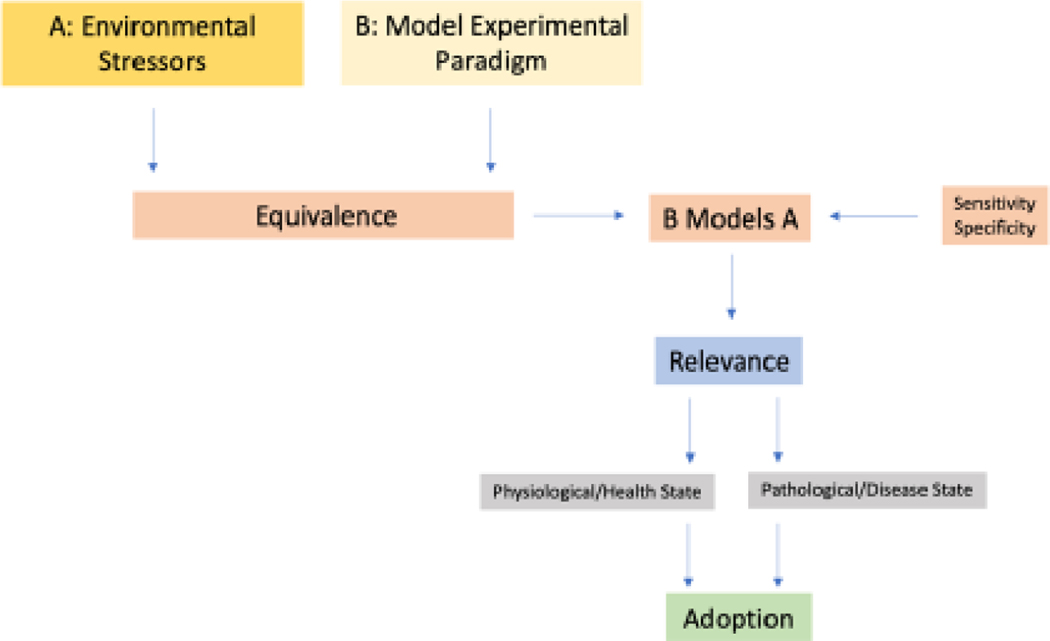

The present review addresses stress with its pathophysiological sequalae by considering the validity of the prevailing stress models i.e., systematic frameworks incorporating stressors, measurable variables, and test paradigms to simulate and understand stress responses (Crosswell and Lockwood, 2020). To that end, we emphasize dimensional and interactive conceptualization of stress, using conventional challenges perturbing the regulatory systems. Instead of strictly adhering to a single model, our approach offers an optimal means of comprehensively understanding the biopsychosocial aspects of stress. Figure 1 depicts a schematic flowchart that outlines the process of identifying and establishing potential evaluation models. This process is akin to the one employed in adopting biomarkers for drug discovery, as described by Borsook et al., 2011. The idea is that specific experimental stress models should adhere to specific criteria concerning their validity, reproducibility, and biological significance.

Figure 1:

What do we measure in Experimental Models of Stress? Stressors are ubiquitous across environmental, social, individual, and societal processes. Models of stress conducted in the laboratory need to capture acute and chronic stressors across health and disease and to understand the implications of such stressors on disease initiation, progression, and resistance to treatment.

At the outset, we delve into the challenges of defining and evaluating stress, discuss various stress conceptualizations and differentiate between non-specific bodily responses and specific organ reactions to stress considering individual and environmental influences on stress symptoms. The interaction between mental and physical aspects of stress is also detailed, exemplifying how stress outcomes are unique for each person. Then various validity types of stress models (Table 1) are addressed including the value of objective assessments alongside self-reports for validity assessments. The body's response to stress involves several regulatory systems, including the sympathoadrenal-, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA)-, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone- (RAAS), arginine-vasopressin- (AVP), and cytokine immune systems (Bali and Jaggi, 2013; Jezova et al., 1995; Tian et al., 2014). Because the ‘fight or flight’ hormones and neurochemicals (Goldstein, 2010) released by the sympathoadrenal system and HPA axis may be construed as a gold standard stress criterion (Schlotz, 2013), an a priori emphasis is placed on the discussion of their role in regulating emotional adaptation, blood pressure, water balance, immune defense, and inflammation in response to internal and external challenges. Next, we discuss how the sympathoadrenal system and HPA axis work together with other systems to restore and maintain homeostasis (Chrousos, 2009) and how various stress models’ validity converge and discriminate, depending on the nature of the stressor stimulus, including its duration (acute vs. chronic) and type (natural vs. man-made). Finally, we provide a summary and conclusions.

Table 1:

Stress-related types of validity

| Validity | Definition | Applicability to Stress |

|---|---|---|

| Construct | Measure of compatibility between the employed model and the concept per se. | Complementary psycho-diagnostic and -metric tools as measures of the stress construct. |

| Criterion | Compatibility of the employed model with the gold standard characteristic of construct it purports to represent. |

Activation of the sympathoadrenal system and HPA axis are commonly accepted characteristics of stress responses. |

| Convergent | Compatibility with other measures of the same construct. | Stress commonly co-occurs with depression, anxiety, tension, confusion, tiredness, anger, disappointment, etc. (Elman et al., 2010; Williamson et al., 2021) |

| Discriminatory | Unique aspects of the applied model. | Assessment whether different stress models, which might be designed to measure various aspects or types of stress, are indeed distinct from one another and not overlapping in terms of the psychological constructs they aim to measure. |

The intentional limitation of the background information and literature review to issues directly relevant to validity of stress models has resulted in some degree of oversimplification. While we recognize the importance of a comprehensive review of stress physiology engaging many other hormones e.g., neuropeptide Y (Reichmann and Holzer, 2016), cholecystokinin (Siegel et al., 1987), or substance P (Iftikhar et al., 2020), the discussion of which would go well beyond the scope of this review. Moreover, as this review draws heavily upon animal models (e.g., social defeat) that are valuable tools for understanding specific aspects of stress biology their findings should be interpreted cautiously (Bracken, 2009). It is important to highlight many uncertainties inherent in extrapolating from animal data to human conditions (Elman et al., 2006) such as a higher level of cognitive, motivational, and emotional complexity compared to animals e.g., intricate social and interpersonal interactions, wide ranging behavioral outcomes’ repertoire, cultural nuances, and societal expectations. That said, the animal models provide a platform for testing the efficacy of behavioral and pharmacological interventions with positive outcomes suggesting potential avenues for human therapeutic development (Ferreira et al., 2019; Singh and Seed, 2021).

2. Search Terms and Methodology

English language literature search of normal stress mechanisms and their potential impairments in patients with chronic stress conditions was undertaken using PubMed, Google Scholar, and Westlaw from inception until October 2023. The search terms included “allostasis,” “adenosine,” “AVP,” “cytokine,” “dobutamine,” “glucoprivation,” “heat,” “homeostasis,” “HPA axis,” “hypovolemia,” immune,” “infection,” “interleukin,” “Maastricht acute stress test (MAST),” “(neuro)chemical,” “(neuro)endocrine,” “pain,” “post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD),” “RAAS,” “sleep deprivation,” “social defeat,” “stress,” “Stroop test,” “sympathoadrenal,” “Trier social stress test (TSST),” and “yohimbine.” Data on stress mechanisms and stress-related morbidity were also drawn from seminal reviews of these topics (Charney, 2004; de Filippi, 1991; de Kloet et al., 2019; de Kloet et al., 2005; Goldstein, 2021; Koob and Schulkin, 2019; McEwen, 2000, 2020; O'Connor et al., 2021; Rodrigues et al., 2009; Tsigos et al., 2000). Additional strategies included manual searches for relevant articles from the selected papers’ reference lists as well as utilization of PubMed’s related articles’ function.

3. Neuroanatomical and Neuroendocrine Stress Determinants

The investigation of stress is often hindered by a fundamental question: How to define, evaluate, or operationalize "stress"? This concept has been given multiple definitions across various disciplines and standpoints e.g., cognitive, emotional, neurobiological, pathophysiological, and molecular. Yet, even among these conceptualizations, widely accepted definitions exhibit circularity, like the concept of “forced exposure to events or conditions that are typically avoided,” which essentially defines stress as stressful experiences (Epstein et al., 2006; Piazza and Le Moal, 1998). Nonetheless, the neuroanatomical and neuroendocrine stress determinants appear to be rigorously established and generally agreed-upon, which could shed more light on the mental and physical stress’ dimensions, its diverse presentations, and potential interventions.

Neural stress domain comprises the sensory apparatus (Gregoric, 2007), viz., organs such as the skin, eyes, ears, nose and tongue (Marzvanyan and Alhawaj, 2023), as well as the associated neural networks that process sensory information and transmit it via afferent neurons to the thalamus. The thalamus relays the sensory input to dedicated visual-, auditory-, and somatosensory primary sensory cortical areas for further processing (Thau et al., 2023; Torrico and Munakomi, 2023). Association prefrontal areas integrate signals from various sensory modalities to ascertain comprehensive perception driving proper responses (Romanski, 2012) that are informed by higher level cognitive analysis, formulating the potential significance of a given stimulus as juxtaposed to potential positive or adverse outcomes (Lerner et al., 2015). The limbic system structures such as the hypothalamus, amygdala and hippocampus are crucial mediators involved in stress responses by adding an emotional context to sensory experiences, as they are receiving input from sensory and cognitive pathways (Godoy et al., 2018; Herman, 2012).

The hypothalamus directs and synchronizes the neuroendocrine aspects e.g. the sympathoadrenal system and the HPA axis (Elman and Borsook, 2016; Smith and Vale, 2006). The amygdala, a key component in emotional processing, coordinates stress-related anxiety and fear (Borsook et al., 2007; Daviu et al., 2019; Elman and Borsook, 2018). Beyond the classical amygdalar circuitry (Janak and Tye, 2015), the extended amygdala e.g., the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis refines the emotional experiences (Elman and Borsook, 2018). The nucleus accumbens, a central hub in the brain's reward and reinforcement circuitry (Scofield et al., 2016), likewise substantially contributes to the affective and motivational dimension of chronic stress (Campioni et al., 2009); insula is responsible for interoception (Haruki and Ogawa, 2021), while reticular formation nuclei mediate arousal and vigilance (Arguinchona and Tadi, 2023). Simultaneously, the medial prefrontal cortex restrains stress systems in concert with the hippocampus, the brain region that is involved in memory and learning (Godoy et al., 2018; McEwen and Gianaros, 2010). Neurochemically, stress influences pivotal systems modulating mood and cognition like norepinephrine, dopamine, serotonin, glutamate and gamma-aminobutyric acid (Fuchs and Flugge, 2004; Kumar et al., 2013). Neurotransmitters’ imbalances introduced by chronic stress may become harbingers of mental disorders such as anxiety (McLaughlin and Hatzenbuehler, 2009), depression (Fuchs and Flugge, 2004) and psychosis (van Winkel et al., 2008).

4. Non-specific vs. Specific Stress Definitions

Stress definitions range from non-specific bodily responses to any type of challenge (Selye, 1950a) to a relatively specific pattern of an effector organ/cell outflow resulting from an actual-, perceived- or anticipated input discrepancy with a homeostatically-defined set point (Elman and Borsook, 2016; Goldstein, 2021). The non-specific nature of stress may be suggested by overlapping brain changes in the aforesaid corticolimbic structures (Daviu et al., 2019) that are observed in response to general categories of adverse experiences, such as emotional trauma (Elman and Borsook, 2019; Elman et al., 2018), anxiety (Chavanne and Robinson, 2021), social isolation (Lam et al., 2021; Bowirrat et al., 2023), pain (Elman et al., 2013; Elman et al., 2011) and pharmacological stimuli (Elman et al., 2012). The non-specific interpretation may be consistent with Hans Selye's stress theory, which postulates a stereotyped response to any type of challenge (Goldstein, 2021) and thus renders stress readily amenable to scientific inquiry when any laboratory-based challenge is deemed externally valid (Andrade, 2018; Selye, 1998) i.e., generalizable across various populations, stimuli, and times as well as pertinent (Holleman et al., 2020) to real-life situations (ecologic validity).

Modern scientists, however, find the non-specific perspective unnecessary reductionistic (Goldstein, 1995). The current prevailing view is that stress affects specific brain networks and systems (e.g., sensory or limbic) and other organs (e.g., heart, gut, kidneys, lungs, skin, etc.) in distinct ways, leading to a variety of stress-related conditions (Elman and Borsook, 2016). For example, mental- as opposed to physical stressors tend to activate distinct brain areas with varying magnitudes (Emmert and Herman, 1999). Furthermore, stimulation of the prelimbic cortex may play a differentiating role in the neuroendocrine responses to mental- vs. physical stressors (Jones et al., 2011). Within this theoretical framework, stress response is non-specific in terms of activating diverse responses (Selye, 1950b, 1976, 1998), whereas it is specific in the sense that a particular type of stress consistently triggers a distinct set of processes (Saab et al., 1992; Saab et al., 1993). Chronic stress can be then viewed as an intervening variable that links diverse allostatic changes with mental and physical symptoms (Goldstein, 1995; McEwen, 2007; Ulrich-Lai and Herman, 2009). Yet, the above symptoms are not solely determined by allostatic changes (McEwen, 2007) but are also influenced by various host- and environment-related factors. In other words, although stress symptoms are determined to some extent by the nature and intensity of stressors, their clinical presentation is also shaped by an individual constitution, genetic makeup, lifestyle, coping resources, state of preparedness, prior exposure to stress, and preexisting conditions (Elman and Borsook, 2019, 2022).

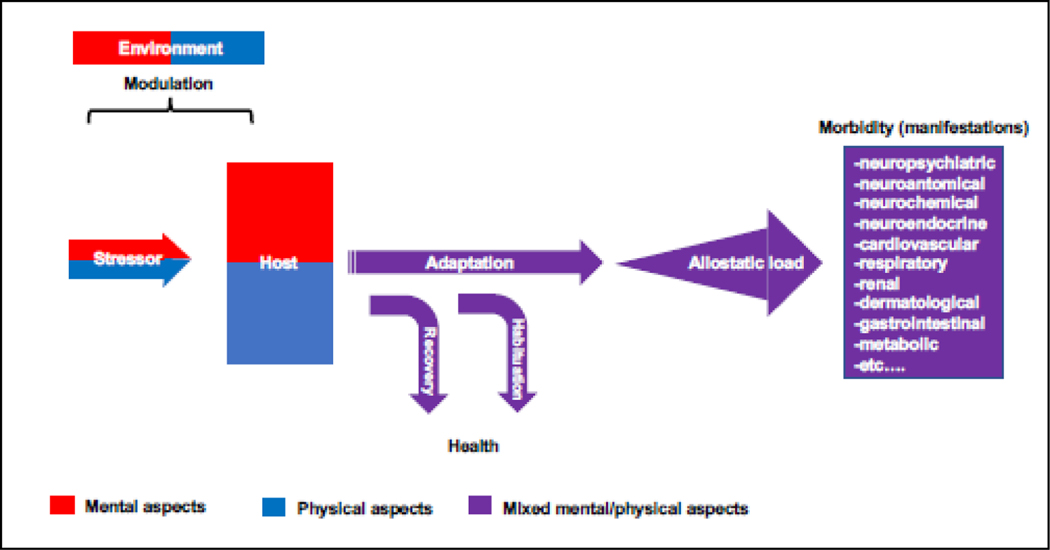

Stress thus encompasses both mental and physical components (Joseph et al., 2021) giving rise to an amalgamation of whole-organism processes that are unique for every person (Figure 2). Pain is an example of the intricate relationship between mental and physical experiences as it may originate exclusively from emotional or social sources, completely devoid of any nociceptive input (Elman and Borsook, 2018; Elman et al., 2013; Elman et al., 2011). Similarly, a slur by a co-worker (social) may elicit an emotion of rage (mental) accompanied by chest pain (physical); both are modulated by environmental factors (e.g., social support, nutrition, or toxic exposure) leading to a possible adaptation (Kalisch et al., 2017). What is more, multiple medical conditions may masquerade as a stress-related psychiatric syndromes (Welch and Carson, 2018) e.g., Cushing disease, where the overproduction of cortisol is presenting as depression and anxiety (Hinotsu et al., 2022). All other things being the same, stress may also interchange pleasant, aversive, or neutral valuation based upon the memorized or perceived contextual factors (Elman et al., 2023). Accordingly, successful coping with a stressful situation may be perceived as pleasant, rewarding, and educational echoing the commonly accepted psychological notion that active avoidance of punishment is reinforcing (Gross, 2006) and evidenced in a variety of stress-seeking behaviors such as roller coasters, automobile racing, skydiving and horror movies (Elman and Borsook, 2019). In essence, stress is a highly individualized experience that everybody understands its meaning but experiences it in a unique way. Establishment of ecological validity or even external validity is complicated because in real life it may be difficult if not impossible to specifically isolate unpredictable contributions of personal meaning from putative mental and physical components (Holleman et al., 2020).

Figure 2:

Schematic overview of the complex interplay among a stressor, host and environment. Stress is not a unitary phenomenon mediated by an isolated mechanism, (neuro)chemical or a neurotransmitter. On the contrary, this hierarchical, multidimensional entity represents integration of higher-order stressor (e.g., nature, intensity or duration), host (e.g., genes, demographics, prior exposure, personality, health) and environment (social network, nutrition, ecology) components and derived from them, lower-order mental and physical manifestations. Each of these plays a specific role within an extensive biopsychosocial system. The combination of mental and physical components gives rise to a variable mental/physical concoction of outcomes. For instance, a slur by a co-worker (mental) may elicit a sense of rage (mental) accompanied by chest pain (physical); both are modulated by social (mental) and nutritional (physical) environmental factors leading to a possible adaptation. Notwithstanding the initial adaptation, habituation or recovery, stressors by their chronic nature tend to generate a mounting allostatic load manifested in poor sleep, impaired cardiovascular function, and systemic inflammation (to name a few). Contrary to such a schematic overview, in real life, it may be difficult if not impossible to specifically account for contributions of the putative mental and physical components because a seemingly physical phenomenon e.g., pain can be solely derived from emotional or social sources in the absence of nociceptive input (Elman et al., 2013) whereas multiple medical conditions can masquerade as a psychiatric syndrome (Welch and Carson, 2018) e.g., anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis (Hinotsu et al., 2022).

To better understand stress, it may be helpful to examine distinct models based on the specific type of a stressor (e.g., sensory, cognitive, or metabolic), host (e.g., demographics, state of health and personal meaning), and environmental (e.g., support, culture, and nutrition) factors (Figure 2). Examining each model separately can provide a solid foundation for understanding its interactions with the related constituents (host and environment). A critical question, addressed here, is whether commonly used experimental stressor models e.g., public speaking, cognitive tasks, hypovolemia or glucoprivation (Elman et al., 1998; Elman and Borsook, 2019; Elman et al., 2003; Kirschbaum et al., 1993) while potentially limited by ethical considerations (non-maleficence principle) and questionable ecological and external validities, still provide valid information about the objective and subjective characteristics of stress. Despite being only one of numerous legitimate ways that "stress" can be scrutinized, these models offer several advantages. First, their validity can be confirmed through existing theoretical and empirical formulations. Second, emerging models can be compared to them as benchmarks of the validated ones (Amirkhan et al., 2015). Third, integrating selected models is likely to yield a more comprehensive methodology for conceptualizing stress phenomena (Bell et al., 2017).

5. Sifting through Stress: From Stressors to Experimental Models

A cascade of mental and physiological stress responses has been reviewed in detail elsewhere (Akil and Nestler, 2023; Forstenpointner et al., 2022), and some key elements are briefly presented here (Table 2). Stressors are stimuli or events spanning mental challenges to physical perturbations (Anisman and Merali, 1999). Stressor-evoked measurable variables are implemented in psychometrically assessed stress ratings (Frisone et al., 2021) together with indices of the sympathoadrenal system, or orchestrations of the HPA axis (Smith and Vale, 2006) allowing to systematically assess and quantify construct- and criterion-validities in the realm of stress. Test paradigms are structured and methodically designed protocols to induce and measure stress responses as exemplified by specific mental (Caruso et al., 1994; Dedovic et al., 2009) or pharmacological (Elman et al., 2012) perturbations (Brouwer and Hogervorst, 2014; Sallee et al., 2000). Such paradigms offer controlled environments, where the experimental evocation of stress reactions can be studied with precision, shedding light on the variability in validities influenced by diverse stressor stimuli. Paradigms establish sound footing for broader models (e.g., PTSD, social defeat, or the TSST) serving as scaffolding for the controlled exploration of stress (Kahn, 2002). At its core, the cornerstone of stress models’ interpretability and validity is formed by thoughtful consideration given to type of stressors and their corresponding paradigms.

Table 2.

Stressors, parameters and experimental models.

| Element | Definition | Characteristic | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stressors (events/accidents) | Stimuli or events that trigger physiological or psychological responses. | Diverse, encompassing both mental and physical stressors e.g., academic exams, public speaking, heavy traffic or financial challenges. | Elicitation of stress responses enabling exploration of the stressor constructs |

| Evaluation parameters | Measurable variables capturing physiological or psychological changes. | Psychometrically assessed stress ratings; activation of sympathoadrenal system and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis e.g., heart rate variability, cortisol levels, self-reported stress scores. | Systematic assessment and quantification of stress-induced reactions enabling assessment of stress models’ construct- and criterion-validities. |

| Paradigms | Structured protocols designed to systematically induce and measure stress responses. | Mental and pharmacological perturbations (e.g., Stroop, simulated job interview, yohimbine, adenosine or dobutamine). | Controlled environments for studying stress reactions experimentally; highlight variability in validity based on the nature of stressor stimuli. |

| Models | Frameworks or systems used in research to study stress under controlled conditions. | Varying validity based on the nature of stressor stimuli (e.g., PTSD, social defeat, or the TSST); shared similarities and differences in construct-, criterion-, convergent-, and discriminant-validities. | Exploration of similarities and differences in the validities of stress models; emphasis on consideration in model selection based on stressor stimuli. |

6. Integrating Validities

Stress models stretch the entire range of the experienced variable, from unconscious to an escalating degree of discomfort and suffering (Cohen, 1995). The quantitative aspect of the stress construct has been measured in numerous studies (Henn and Vollmayr, 2005; Willner, 1984) using self-ratings and more structured/comprehensive rating scales and interviews. While the validity of data obtained by such methods has been examined in student, community, and workplace populations, there remains potential for underreporting, denial, and cognitive distortions (Elman et al., 2000). Therefore, more objective assessments such as physiological responses or biomarkers criteria complement self-reported measures (Smyth et al., 1998) by quantifying the strength of correlation with self-report data (Cohen et al., 1983). This complementary approach also possesses practical importance for establishing the convergent and discriminant validity (Schuhmann et al., 2022; Westen and Rosenthal, 2003). The former validity refers to the extent to which different measures of the same construct are related (e.g., distress and anxiety); the latter validity refers to the extent to which a specific model reflects a unique construct (Table 1). By combining diverse validities, researchers and clinicians alike can gain a more comprehensive understanding of stress and its effects on mental and physical health.

7. Sympathoadrenal System and HPA Axis

Sympathoadrenal System.

A constituent of the autonomic nervous system (McCorry, 2007), the sympathoadrenal system, encompasses the sympathetic nervous system and the adrenal medulla (Cohen, 1995). The sympathoadrenal system is responsible for the instantaneous (seconds-minutes) "fight or flight"-type confrontation of a stressful situations (Godoy et al., 2018; Goldstein, 2021). Originating in the spinal cord, sympathetic nervous system innervates (via the norepinephrine neurotransmitter) various target tissues and organs to generate physiological adaptations to stress (Goldstein and Kopin, 2007). The adaptations include increased cardiac output, leading to enhanced blood flow and oxygen supply to skeletal muscles and vital organs (Joyner and Casey, 2015). Simultaneously, there is vasoconstriction to reduce blood supply to non-essential organ (Bruno et al., 2012) that can tolerate a temporary hypoperfusion without compromising vital functions or immediate survival (skin, digestive system, kidneys, reproductive system, and extremities). Also, bronchial dilation occurs to improve oxygen intake and mydriasis enhances visual acuity (Goldstein, 1995). The endocrine extension of the sympathetic nervous system, the adrenal medulla, releases mainly epinephrine (80%) and a smaller amount (20%) of norepinephrine (Carroll, 2007) into the systemic circulation. While both catecholamine hormones have similar vasoconstrictive effect, the former has broader systemic impact e.g., enhanced cardiorespiratory performance, glycogenolysis, and lipolysis (Goldstein, 1995). Negative feedback mechanisms within the sympathoadrenal system aimed at preventing overstimulation e.g., paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of hypothalamus receives feedback from the locus coeruleus to modulate the sympathetic response (Samuels and Szabadi, 2008a). Moreover, activation of presynaptic α2- adrenoceptors centrally in the hypothalamus and peripherally on sympathetic nerve terminals inhibits further release of epinephrine and norepinephrine (Bylund et al., 2008; Gothert, 1985). Remarkably, unlike certain hormones that possess inherent mechanisms to suppress their own synthesis through negative feedback loops, epinephrine, norepinephrine and catecholamines at large lack such self-regulatory capacity (Encyclopedia, 2023)

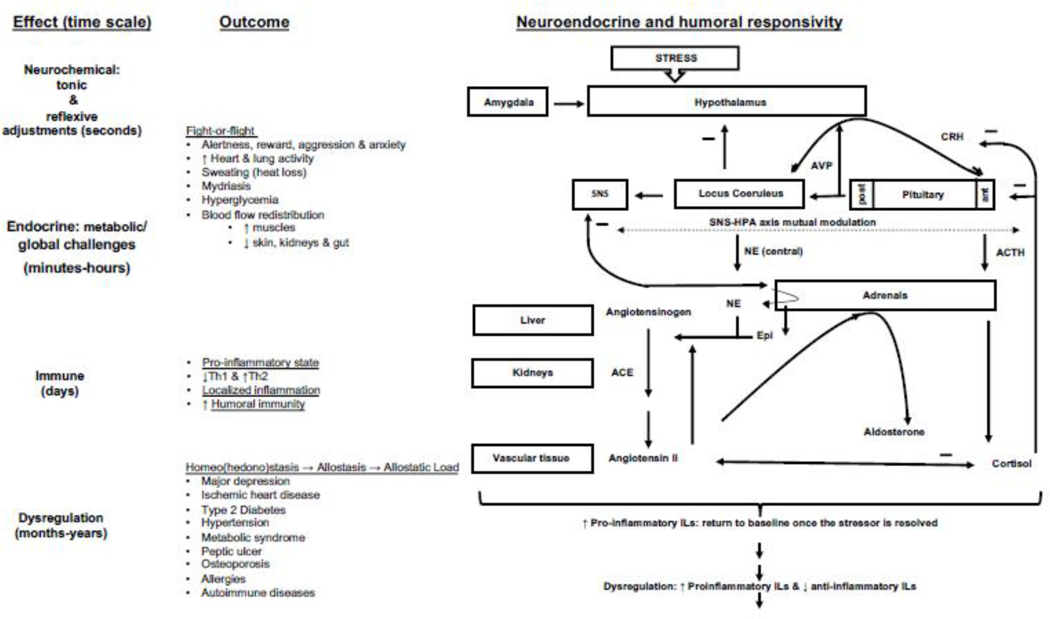

It is therefore essential to underscore the role played by complementary systems e.g., the HPA axis and other regulatory pathways, in the fine-tuning of the neurochemicals’ release and activity and maintaining their equilibrium while orchestrating the comprehensive stress response. Understanding the interactions among major stress systems helps to identify potential confounding factors that may affect the validity of experimental stress models. For example, if a stress model activates the sympathoadrenal system but not the HPA axis, it may not reliably reflect the entire range of physiological stress responses (Figure 3).

Figure 3:

Key physiological stress systems namely, the Sympathoadrenal System, HPA Axis, Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System, Arginine Vasopressin and Immune System. Originating in the spinal cord, sympathetic nervous system (SNS) innervates (via the norepinephrine neurotransmitter) various target tissues and organs to generate physiological adaptations to stress (Goldstein and Kopin, 2007). The adrenal medulla, releases mainly epinephrine (80%) and a smaller amount of norepinephrine (20%) graphically displayed in the thickness of the arrow. The Sympathoadrenal System, comprising the sympathetic nervous system and adrenal medulla, initiates instantaneous "fight or flight" responses, including increased heart rate, blood flow redistribution, bronchial dilation, and heightened alertness. The HPA Axis involves helps mobilize energy reserves and suppress immune function in response to stress. These systems’ interactions range from additive to synergistic, depending on stress duration and nature. The RAAS’ hormones, aldosterone and angiotensin II regulate blood pressure and fluid balance. The Arginine Vasopressin (AVP) system plays a role in maintaining blood pressure, fluid equilibrium, and osmolarity. Both RAAS and AVP systems interact with the sympathetic and HPA systems to optimize stress responses. Stress profoundly affects immune system., immune cell activity, pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokine release, and immune function modulation. Stress responses, while adaptive in the short term, can lead to immune dysregulation, impacting susceptibility to infections and the development of inflammatory and autoimmune conditions over time. For the clarity of presentation, the scheme was drawn out-of-scale and simplified to reduce the numbers of the displayed links and structures to those of direct relevance to the theme of this review.

Abbreviations: ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; ant, anterior; CRH, corticotropin-releasing hormone; epi, epinephrine; interleukin, IL; NE, norepinephrine; post, posterior; Th1, T helper type 1; and Th2, T helper type 2

The HPA Axis is made of three components connected via reciprocal interactions namely, 1) the PVN secreting corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) into the hypothalamic-pituitary portal system during stress exposure; 2) the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland reacting to CRH by releasing adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) into the bloodstream sensed by 3) the adrenal glands’ cortex middle fasciculata zone consequently releasing a glucocorticoid, cortisol (Chrousos, 2009; Herman et al., 2016; Smith and Vale, 2006). Cortisol facilitates stress coping by mobilizing energy reserves (via gluconeogenesis and diminished insulin’s secretion and signaling), increasing blood pressure and suppressing the immune system (Sapolsky et al., 2000; Tsigos and Chrousos, 2002). Rising plasma cortisol concentration exerts negative feedback on the hypothalamus and pituitary via the medial prefrontal cortex and hippocampus (Kinlein et al., 2015) inhibiting the release of CRH (Papadimitriou and Priftis, 2009) and ACTH (Allen and Sharma, 2023), respectively (Herman et al., 2003; Ziegler and Herman, 2002).

The integration of the sympathoadrenal system and HPA axis involves intricate feedback mechanisms synchronizing diverse brain nuclei (Forstenpointner et al., 2022; Ulrich-Lai and Herman, 2009). The amygdala and related limbic regions (Herman et al., 2016) such as prefrontal cortex and hippocampus serve as a key interface between the perceptual and cognitive appraisal of a stressor with the ensuing physiological responses (McEwen and Gianaros, 2010; Pessoa, 2010) by providing emotional (Pego et al., 2010) and contextual (Herman et al., 2016; Stanton et al., 2023) information to the PVN (Coote, 2005), which, in turn, regulates sympathetic activity and coordinates the release of HPA axis’ hormones (Ferguson et al., 2008; Herman et al., 2016; Swanson and Sawchenko, 1980). When the PVN detects a stressful or threatening stimulus, it initiates the sympathoadrenal response to stress by triggering norepinephrine release from the locus coeruleus (Berridge and Waterhouse, 2003; Valentino and Van Bockstaele, 2008) responsible for augmented body's sympathetic activity (Samuels and Szabadi, 2008b), arousal as well as attention prioritization across stressful challenges. The locus coeruleus neurons’ activity is tightly regulated by the convergence of several inputs, particularly the CRH, AVP (Berecek et al., 1984; Olpe and Steinmann, 1991), excitatory amino acids, and opioids (Berridge and Waterhouse, 2003). The interchange between the systems helps harmonize the body's overall coping means, allowing for the appropriate resources allocation and homeostasis restoration after stress adjustment (Ulrich-Lai and Herman, 2009).

The combined output of the sympathoadrenal and HPA systems culminates in a comprehensive and integrated stress response involving rapid physiological changes and sustained adjustments over time (Herman et al., 2016). Even though the specific nature of the interactions between the sympathoadrenal system and the HPA axis can vary in different stress-related circumstances (Herman and Cullinan, 1997; McEwen, 2007), cortisol modulates the release of epinephrine and norepinephrine (Wurtman, 2002) whereas catecholamines can stimulate the HPA axis (Lee et al., 2011; Lundberg, 2007) to release more cortisol (Goldstein and Kopin, 2008; Tsigos et al., 2000). Acute stress (seconds-minutes) primarily engages the sympathoadrenal system, while prolonged- (minutes-hours) or chronic stress is characterized in more complex interactions (Carrasco and Van de Kar, 2003; Godoy et al., 2018; Ulrich-Lai and Herman, 2009). By and large, three classes of interaction (co)exist between sympathoadrenal system and HPA axis, including addition, competition, and synergism (Ehrhart-Bornstein et al., 1998; Fukuhara et al., 1996).

Additive interactions involve independent but combined effects e.g., blood pressure elevation due to vasoconstriction (Goldstein, 1981) or reabsorption of sodium by the kidneys that diminishes the excretion of water (Armando et al., 2011). In a competitive interaction, epinephrine and norepinephrine suppress the activation of the HPA axis to avoid overstimulation. Synergistic interactions occur when the sympathoadrenal system and the HPA axis work together to enhance the overall stress response (Dunn and Berridge, 1990; Hirotsu et al., 2015; Ulrich-Lai and Herman, 2009). Both norepinephrine and epinephrine can amplify the activation of the HPA axis (Elman et al., 2001a; Jasper and Engeland, 1997; Ulrich-Lai et al., 2006) and increase the sensitivity of target tissues to cortisol (Herman et al., 2016; Mokuda et al., 1992; Ulrich-Lai and Engeland, 2002) whereas cortisol influences the release (Seki et al., 2018) and effects (Xiao et al., 2003) of norepinephrine and regulate the activity of enzymes involved in catecholamine metabolism (Wurtman and Axelrod, 1966). Such interaction potentiates the effects of both the sympathoadrenal system and the HPA axis, leading to an intensified physiological response to stress.

During acute stress sympathoadrenal systems’ activity may predominate against the backdrop of a relatively limited HPA axis’ activation (Rotenberg and McGrath, 2016). Conversely, over time, the HPA axis becomes prominent and the interactions between the two systems gradually shift from competitive to synergistic (de Kloet, 2003). Cortisol plays a role in both stress response modes by interacting with two types of receptors: type 1 (mineralocorticoid receptors - MR) and type 2 (glucocorticoid receptors - GR). These receptors are found in the limbic neural circuitry (Joels, 2017); Koning et al., 2019). MR regulate the baseline sensitivity or threshold of the fast stress system, thereby preventing disruption of homeostasis (Gomez-Sanchez and Gomez-Sanchez, 2014). On the other hand, GR facilitates the recovery process by dampening stress responses in stress circuits and mobilizing energy resources (de Kloet et al., 2019). Maintaining a balance between the two stress response modes is crucial for cellular homeostasis, mental performance, and overall well-being (Daskalakis et al., 2022). An imbalance, whether caused by (epi)genetic modifications or chronic stressors, can alter specific neural signaling pathways that underlie normal cognitive and emotional processes instigating allostatic load underlying medical and neuropsychiatric (co)morbidity (de Kloet, 2003; Nicolaides et al., 2000).

8. Allostatic Load

Health complications stemming from chronic stress are intricately linked to the concept of allostatic load (McEwen, 1998; McEwen and Wingfield, 2003), which emerges due to the exhaustion of homeostatic abilities to shield the body's myriad systems from cumulative wear and tear (McEwen and Gianaros, 2011). The allostatic load resulting from prolonged sympathoadrenal stimulation is marked by the disruption of negative feedback mechanisms (Goldstein, 2010) manifested in such clinical outcomes as hypertension, disrupted sleep patterns, compromised immune function, abnormalities in gastrointestinal motility, and disturbances in glucoregulatory function (Dunser and Hasibeder, 2009; McEwen, 1998; Reaven et al., 1996). That causality can operate in reverse as well (Figure 3). For instance, congestive heart failure can act as a catalyst for persistent activation of the sympathetic nervous system, adopting a misguided strategy to compensate for diminished cardiac function or to ensure adequate blood supply (Floras, 2009). This sustained release of catecholamines further erodes cardiovascular performance, that is, a detrimental feedforward interaction (Goldstein, 2021).

HPA axis dysregulation (Kinlein et al., 2015), stemming from its protracted activation, disrupts the negative feedback mechanisms governing plasma cortisol concentrations (Charney, 2004; Karatsoreos and McEwen, 2013). Diminished cortisol responses (de Kloet et al., 2006) are linked to such conditions as chronic fatigue syndrome (Powell et al., 2013) and PTSD (Kinney et al., 2023). In susceptible individuals (de Kloet et al., 2005) hypercortisolemia, conversely, heightens the risk of diabetes (Brindley, 1992), hypertension (Whitworth, 1994), osteoporosis (Czapla-Iskrzycka et al., 2022), opportunistic infections (Lionakis and Kontoyiannis, 2003), delayed wound healing (Matsuzaki and Upton, 2013), and a predisposition to autoimmune disorders (Charney, 2004) along with an array of neuropsychiatric symptomatology (Dziurkowska and Wesolowski, 2021), encompassing depression (Sahu et al., 2022; Teo et al., 2023; Varghese and Brown, 2001), anxiety (Fischer, 2021; Zorn et al., 2017), and psychosis (Elman et al., 1998; Elman et al., 2003).

9. Other Stress Systems

RAAS.

Stress systems cannot be viewed in isolation, as they are integrated within a complex network of tightly linked configurations (Figure 3), each serving a distinct purpose in the context of stress-related homeostatic and allostatic adjustments (Elman and Borsook, 2016). The RAAS system is primarily involved in the regulation of blood pressure and fluid balance (Carey, 2018; Fountain et al., 2023). Under stressful conditions, kidneys release the renin enzyme (Persson, 2003), which cleaves angiotensinogen in the liver to produce angiotensin I (Benigni et al., 2010). Angiotensin I, converted to a potent vasoconstrictor, angiotensin II by the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) in the blood vessel tissue (Timmermans et al., 1993), acts on the exterior layer of the adrenal cortex, the zona glomerulosa, to stimulate the release of aldosterone, which promotes the reabsorption of sodium and water in the kidneys to increase blood volume and pressure (Fountain et al., 2023). Reciprocal interactions among the sympathoadrenal system, HPA axis, and the RAAS add further optimization to coordination of stress coping mechanisms (Atlas et al., 1981; Gideon et al., 2020; Murck et al., 2012). Norepinephrine, epinephrine as well as the HPA axis’ components, ACTH (Ganong, 1981; Hu et al., 1992; Kopp and DiBona, 1986) and cortisol (Skov et al., 2014) can enhance the RAAS with consequently elevated levels of angiotensin I and angiotensin II. In a feedforward loop, angiotensin II stimulates the sympathoadrenal system (King et al., 2013) and the release of CRH (Ganong and Murakami, 1987). Thus, the sympathoadrenal system, HPA axis and RAAS work in concert to mobilize energy reserves, increase cardiovascular function, enhance alertness; all support the body's ability to cope with immediate challenges (Figure 3). In contrast, protracted activation of these systems during chronic stress results in systematic disintegration contributing to long-term allostatic effects on blood pressure, fluid balance, cardiovascular and emotional health (Herman et al., 2016; Murck et al., 2003).

The AVP system likewise controls blood pressure, fluid equilibrium and osmolarity via osmotic and non-osmotic (373467) mechanisms e.g., hypovolemia, emotional distress or hypoxia (Cuzzo et al., 2023; Elman et al., 2003; Soto-Rivera, 2017). Osmoreceptors in the hypothalamus detect rises in solutes’ concentration and trigger AVP release from the posterior pituitary gland (Cuzzo et al., 2023); this process is enhanced by catecholamines, cortisol and angiotensin II (Leibowitz et al., 1990). AVP causes water reabsorption in the kidneys, leading to concentrated urine and water retention; AVP also augments CRH release and activity (McCann et al., 2000; Stojiljkovic et al., 2022). In this intricate arrangement, the vasoconstrictive attributes of catecholamines, cortisol and angiotensin II (Kanaide et al., 2003; Riad et al., 2002; Ullian, 1999), work in harmony to complement AVP's actions in not only constricting blood vessels, but also enhancing water retention (Cuzzo et al., 2023) thus contributing to the maintenance of blood volume and pressure during instances of heightened sympathetic activity while adjusting to changing physiological demands (Figure 3). In certain pathological conditions, such as heart failure, kidney dysfunction, or chronic hypertension, the AVP system and the RAAS may become disintegrated reflected in excessive water retention, electrolyte imbalances, and increased blood pressure (Ames et al., 2019; Ma et al., 2022; Ma et al., 2010).

Oxytocin is commonly recognized as a stress-relieving neuropeptide (Takayanagi and Onaka, 2021) via central and peripheral processes (Etgen, 1995; Ho and Blevins, 2013; Reichel, 2021) with extensive ramifications for social affiliations (Baribeau and Anagnostou, 2015; Insel, 2003), reproduction (Ivell et al., 1997; Lippert et al., 2003), anti-inflammation (Friuli et al., 2021; Yuan et al., 2016), analgesia (Nishimura et al., 2022), antioxidation (Alanazi et al., 2020; Buemann et al., 2021), metabolism (Iovino et al., 2023), cognition (Erdozain and Penagarikano, 2019), mental health (Cochran et al., 2013) and overall wellbeing (Carter et al., 2020). It is structurally alike AVP (Baribeau and Anagnostou, 2015) and both hormones are released together from the posterior pituitary (Christ-Crain and Ball, 2000). While AVP and oxytocin exert a degree of functional antagonism regarding the HPA axis (Neumann et al., 2000) and sympathoadrenal activity (Grewen et al., 2005; Uvnas Moberg et al., 2019) moderated by sex (Carter and Perkeybile, 2018; Jirikowski et al., 2018; Love, 2018), action sites (Neumann, 2002), plasma concentrations (Song and Albers, 2018) or contexts (Carter et al., 2020) they can also act as agonists at each other’s receptors yielding potentially additive or synergistic effects (Song and Albers, 2018).

Immune System.

In addition to their pivotal roles in adaption to stress and in the maintenance of blood pressure and fluid balance, neuroendocrine systems also profoundly affect immune function (Chrousos and Gold, 1992; Sekaninova et al., 2020; Tsigos et al., 2000). Acute stress favors humoral immunity by down-regulation of T helper 1 cells and up up-regulation of T helper 2 cells-mediated cytokine activity (Assaf et al., 2017; Rajaei, 2022). The neuroendocrine-immune crosstalk (Tian et al., 2012) is mediated by interleukin type cytokine proteins (Justiz Vaillant and Qurie, 2023; Liu et al., 2021) that are secreted from macrophages, T cells, T regulatory cells, B cells, dendritic cells, as well as non-immune endothelial cells and fibroblasts (Zhang and An, 2007) and can have both pro- and anti-inflammatory properties (Godinho-Silva et al., 2019; Tian et al., 2012). Stress-induced activation of the sympathoadrenal system predominately (Koldzic-Zivanovic et al., 2006) amplifies proinflammatory pathways engaging interleukin (IL) 6 and 8 (Goebel et al., 2000; Steensberg et al., 2001; van der Poll and Lowry, 1997b). Such responses may be adaptive from a phylogenetic standpoint as they are coping with potential injuries or infections during a stressful event. Yet there are also balancing effects including suppression of the tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and IL-1 beta (IL-1β) proinflammatory- (Van der Poll and Lowry, 1997a) and enhancement of anti-inflammatory IL-10 (van der Poll et al., 1996a; Van der Poll and Lowry, 1997a) signals by epinephrine. Proinflammatory ILs released during immune responses stimulate hypothalamus to increase AVP and the HPA axis’ activity (Bethin et al., 2000; Chikanza et al., 2000), leading to cortisol surge that dampens proinflammatory cytokines like IL-6, TNF-α and IL-1β (Dong et al., 2018).

Furthermore, proinflammatory ILs such as IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-1 stimulate the RAAS system (Bataillard et al., 1992), leading to increased angiotensin II production (Andreis et al., 1992; Flesch et al., 2003; Gurantz et al., 1999; Senchenkova et al., 2019). Angiotensin II, in turn, contributes to the release of additional proinflammatory ILs (OĽeary et al., 2016; Pacurari et al., 2014), promoting inflammation and immune activation, which is conspicuous in conditions like hypertension and ischemic heart disease (Amin et al., 2020; Satou et al., 2018). IL-producing immune cells express AVP receptors (Baker et al., 2003) that might decrease proinflammatory cytokines (Russell et al., 2013) e.g., IL-6, TNF-α and IL-1β (Boyd et al., 2008; Park, 2015; Zhao and Brinton, 2004) and affect the migration of immune cells to specific sites in the body (Wiedermann et al., 2018).

Ultimately, the types of ILs released, and the type of immune cells involved, and their function determine the nature of the response, whether acute enhancement, diminution, or dysregulation, depending on the balance of the intricate interactions (Justiz Vaillant and Qurie, 2023). All in all, acute neuroendocrine effects on the immune response involve mobilizing immune system to fight infections, and aid tissue repair whereas prolonged stress may dysregulate immune function including an overproduction of proinflammatory ILs and an underproduction of anti-inflammatory ILs (Figure 3) manifested in susceptibility to infections, and the development of inflammatory and autoimmune conditions (Dhabhar, 2009; Segerstrom and Miller, 2004).

10. Construct and Criterion Validity

Construct validity: Validated psycho-diagnostic and psychometric tools.

Due to their standardized, objective, and comprehensive measurements of psychological stress (Blevins et al., 2015; Weathers et al., 2018) many psycho-diagnostic/metric tools (Osorio et al., 2019; Shankman et al., 2018) offer suitable means for evaluating the construct validity of stress models (Crosswell and Lockwood, 2020). Among others, tools like the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5) Disorders (Shabani et al., 2021), Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) for DSM-5 (Back et al., 2022; Elman and Borsook, 2022), PTSD Checklist (PCL) for DSM-5 (Kramer et al., 2023) and even self-ratings (Masood et al., 2012; Thornorarinsdottir et al., 2019) have undergone rigorous testing to enable the inquiry into emotional, cognitive, and behavioral dimensions of stress providing a nuanced understanding of their construct validity (Aguilo Mir et al., 2021; Amirkhan, 2018). The yielded quantitative data allows statistical testing to determine the association between stress models and psychological constructs and to compare stress outcomes with available norms or benchmarks for the specific psychological constructs being assessed (Elman et al., 2009; Elman et al., 2018). Standardization of the assessments facilitates their meaningful comparisons and conclusions as they are applied consistently across different individuals and settings. Psycho- diagnostic/metric tools likewise provide objective measurements of psychological constructs related to stress, such as anxiety and depression (Elman et al., 2010; Green et al., 2017). Importantly, many psychodiagnostic tools have clinical relevance and are used in diagnosing and treating stress-related mental health conditions (Weathers et al., 2018). By evaluating the construct validity of stress models with tools commonly employed in clinical practice, researchers can connect theoretical stress concepts with real-world applications rendering these tools a crucial element in both clinical settings and research environments.

Criterion validity: The sympathoadrenal system and HPA axis.

Criterion validity refers to the extent to which a model is capable of accurately and consistently predicting or correlating with a particular criterion or outcome of interest (Piedmont, 2014). As alluded above, the suitability of the sympathoadrenal system and HPA axis activations as criteria, albeit not the exclusive ones (Levy et al., 2021), for assessing the validity of stress models stems from their central role in the physiological and psychological response to acute and chronic stress (Kvetnansky et al., 1995; Smith and Vale, 2006). There are many additional reasons as to why the sympathoadrenal system and HPA axis are regarded as key criterion validity characteristics for stress models.

These systems are widely recognized in the scientific and clinical communities as biomarkers of stress (Piazza et al., 2010). In terms of practicality, catecholamines and cortisol are readily quantifiable in blood, saliva, or urine (Beerda et al., 1996; El-Farhan et al., 2017). In the realm of physiology, sympathoadrenal system mediates immediate, ‘fight-or-flight’ responses (Carter and Goldstein, 2015) while the HPA axis regulates the sustained response to stress (Herman et al., 2016). Stress models that incorporate both systems can account for the temporal dynamics of the stress response, making them more comprehensive and physiologically relevant. On the clinical level, the sympathoadrenal system and HPA axis are key neuroendocrine pathways determining stress resilience or vulnerability (Charney, 2004). Valid stress models could be instrumental for stress vulnerability screening with primary and secondary prevention implications (Elman and Borsook, 2019). From pathophysiological perspective, since the sympathoadrenal system and HPA axis are associated with a range of stress-related psychiatric and medical disorders (Bjorntorp et al., 2000; Maes et al., 1991), valid stress models may capture specific dysregulations to provide mechanistic and therapeutic insights. Notwithstanding the sympathoadrenal system and HPA axis frequent use as primary criteria for stress model validation, a comprehensive approach to stress modeling ought to consider multiple criteria to ensure understanding of the complex biopsychosocial dimensions of stress. Thus, the choice of criterion validity characteristics needs to align with the aims of research and the aspects of stress being investigated.

Due to the complexity of the stress mechanisms and the interactions among its various facets, it would be possible to generate countless volumes of scientific and clinical work depicting stress-related biopsychosocial effects and alterations. Similarly, when considering the organ systems affected by stress in comparison to non-stressed subjects, the list seems exhaustive, encompassing every part of the body from head to toe. For the present discussion, we address frequently employed diverse and representative stress models exemplifying their commonalities, disparities, and diverse validities namely, the PTSD, social defeat, TSST, MAST, Stroop test, infection, hypovolemia, glucoprivation, heat, sleep deprivation, pain, adenosine, dobutamine and yohimbine (Table 3).

Table 3:

Abridgment of representative stress models

| Origin | Duration | Cause | Validity | Comments | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute | Chronic | Natural | Man-made | Construct (measure) | Convergent | Discriminant | Criterion | ||||

| HPA axis | Sympat hoadrenal | ||||||||||

| Mental | — | PTSD (e.g., torture motor vehicle accident) | X | X | Reliving traumatic event(s) measured via Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale, the PTSD Checklist (Mueser et al., 2001), Civilian (Green et al., 2017) and Combat (Beresford et al., 2021) Mississippi Scale etc... | Horror, anger guilt, or shame; diminished value of natural reinforcers and unhappiness (American Psychiatric, 2022) | Pathophysiological model of chronic stress (Elman and Borsook, 2019) | ↓ (Fischer et al., 2021; Gola et al., 2012) | ↑ (Fu, 2022; Pervanidou et al. 2007), but see (Videlock et al., 2008); sympat hetic hyperarousal is the key feature (American Psychiatric, 2022) | Laboratory animals’ models may not properly capture the complexity of the syndrome (Videlock et al., 2008) | |

| — | Social defeat | — | X | The Social Defeat Scale, (Gilbert and Allan, 1998) | Bullying, subordin ation (Bjorkqvist, 2001), burnout, work-related stress (van der Molen et al., 2020), aggression and humiliation (Bjorkqvist, 2001; Rohde, 2001); debating with a member of the opposite gender (Bjorkqvist, 2001; Rejeski et al., 1989)“ residentintruder“ procedure in animals (Koolhaas et al., 2013) | Neuropsyc hiatric disorders e.g., major depression, generalized anxiety disorder and schizophre nia (Bjorkqvist, 2001; Laviola et al., 2004; Rohde, 2001) | ↑ (Cannizzaro et al., 2020; Iob et al., 2021; Laceulle et al., 2017) | ↑ (Ghaddar et al., 2014; Nakatake et al., 2020; Rajalingam et al., 2021) | More studies on concordance between human and animal research are needed (Bjorkqvist, 2001) as human studies are usually retrospective or cross-sectional | ||

| Trier social stress test | — | — | X | Self-reported acute stress (Hellham mer and Schubert, 2012; Mohiyeddini et al., 2013) | interview preparation, public speech and mental arithmetic task (Frisch et al., 2015); ↑ anxiety and insecurity (Hellhammer and Schubert, 2012) | Robust and reliable neurobiological effects notwithstanding the psychosocial nature of the task (Allen et al., 2017) | ↑ (Gabrys et al., 2019; Hellhammer and Schubert, 2012) | ↑ (Bremner et al., 1996) | Ecological validity is good for Western cultures, external validity for non-Western remains to be examined | ||

| Maastricht acute stress test | — | — | X | Self-reported acute stress (Smeets et al., 2012; van Ruitenbeek et al., 2021); the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Shilton et al., 2017) | Elements of the Trier Social Stress Test, the Cold Pressor Test, stress of social evaluation (Smeets et al., 2012) | Combination of the Trier social stress test and the Cold Pressor Test is unique | ↑ (Bali and Jaggi, 2015) | ↑ (Bali and Jaggi, 2015; van Ruitenbeek et al., 2021) | Limited ecological validity of the Cold Pressor Test | ||

| Stroop test | — | — | X | Self-reported acute stress (Renaud and Blondin, 1997) | Self-reported anxiety (Tulen et al., 1989); working memory (Tulen et al., 1989); information processing e.g., attention (Parris et al., 2022), speed (Perianez et al., 2021) and parallel disturbance (Herd et al., 2006) | Consistent engagement of the anterior cingulate- and dorsolateral prefrontal cortices (Milham et al., 2003) | ↑ (Compton et al., 2013; Young Kuchenbecker et al., 2021) | ↑ (Huang et al., 2021; Renaud and Blondin, 1997; Vazan et al., 2017) | Multiple trials are required in order to elicit stress responses (Renaud and Blondin, 1997) | ||

| Physical | Infection | X | X | X | “Post-COVID Stress Disorder” ≅ PTSD (Tucker, 2021); Holeboard open field apparatus for anxiety-like behavior (Lyte et al., 2006) | Generalizable across various types of pathogens (Gareau et al., 2011) | Memory dysfunction (Gareau et al., 2011) | ↑ (Dunn, 1993a, b) | ↑ (Dunn, 1993a, b; Dunn et al., 1989) | Paucity of human studies; the construct validity of the COVID-induced stress is questiona ble given potential environmental impacts | |

| Hypovolemia (e.g., dehydration or blood loss) | — | X | X | Anxiety (self-reported or observed) ((Medline Plus, 2021) | Agitation, confusion and fatigue (Medline Plus, 2021) | Initially specific stress response (activation of the sympathon eural system), which becomes generalized following deterioratio n (Goldstein, 1995) | ↑ (Gann, 1979; Lilly et al., 1983) | ↑ (Bond and Johnson, 1985) | Poor construct validity | ||

| Glucoprivation (hypoglycemia) | — | — | X | Self-reported distress (Breier, 1989; Elman et al., 2004) | Whole body level hormonal response (Kerr et al., 1989; Schwartz et al., 1987) | Hunger, counterreg ulatory hormones (Breier, 1989; Muneer, 2021) | ↑ (Breier, 1989; Elman et al., 1998) | ↑ (Breier, 1989; Elman et al., 2004) | Acccomp anied by hunger and tiredness | ||

| Heat | X | X | X | Subjective heat stress question naire (Beckmann, 2021 #738; 26411664}. Objective quantification of the environmental stress-, personal stress- and heat strain indices factoring in ambient and core temperature, relative humidity, solar radiation and heart rate (Garzon-Villalba et al., 2017; Ramphal-Naley, 2012). | Heat-induced pain (Elman et al., 2018) | Heat exhaustion (Gauer and Meyers, 2019), hyperventilation (Tsuji et al., 2016), syncope, edema, rash (Howe and Boden, 2007), (Wilson et al., 2014) and stroke (Morris and Patel, 2023) | ↑ (Brenner et al., 1998; Follenius et al., 1982; Wang et al., 2015) | ↑ (Boonruksa et al., 2020; Cheshire, 2016; Cramer and Jay, 2016) | Good ecologic validity as heat is part of everyday life (Kunz-Plapp, 2018) external validity is questionable given cross-cultural temperature preference variability (Havenith, 2020) | ||

| Sleep deprivation | X | X | X | Various stress questionnaires (Gardani et al., 2022) e.g., a global measure of perceived stress (Cohen et al., 1983); Depressi on Anxiety Stress Subscale (Lovibond and Lovibond, 1995) and Undergra duate Stress Question naire (Schlarb et al., 2017), the stress component of the Patient Health Questionnaire (Schlarb et al., 2017) | Hypertension, glucoregulatory abnormalities, cardiovascular events, depression and anxiety (Hanson and Huecker, 2023) | Diminished alertness, excessive sleepiness, accidents (Colten et al., 2006) | ↑ (Nollet et al., 2020; Tsai et al., 1989) | Inconsistent findings; both ↑ (Lusardi et al., 1999; Tochikubo et al., 1996) and no change reported (Kato et al., 2000) | Good ecologic and external validity in the face of questionable criterion validity | ||

| Pain | ≅ PTSD due to persistent relieving of stress (26748087) | X | X | Various stress questionnaires e.g., Cohen’s Perceived Stress Scale (Vinstrup et al., 2020) | Neurobiological and clinical overlap with emotional pain e.g., depression, anxiety and PTSD (Borsook et al., 2016; Elman et al., 2013; Elman et al., 2011) | The involvement of the neural sensory apparatus (Elman and Borsook, 2016); pain-induced pleasure or algophilia (Elman and Borsook, 2016) | Initially analgesic (Hannibal and Bishop, 2014); chronically enhances pain (Griep et al., 1998; Tennant and Hermann, 2002) | Initially analgesic; later evolves to enhance pain (Taylor and Westlund, 2017; Tsigos et al., 1993) | Limited criterion validity; limited external validity e.g., cross cultural variability in perceived childbirth pain; offset of pain from daggers and hooks deeply penetrating the body from being a participant in a sacred ceremony (Elman and Borsook, 2016) | ||

| Pharmacological agents | Adenosine | — | — | X | Indirect evidence cardiac effects are similar to those of mental stress (Gottlieb et al., 2014) | — | An alternative for cardiac stress test (O’Keefe et al., 1992); causes transient AV block; reduces blood flow to ischemic areas i.e., coronary steal (Aetesam-Ur-Rahman et al., 2021) in the face of increased cardiac perfusion (Yimcharoen et al., 2020) | ↓ (Chamey et al., 1985) | ↓ (Richardt et al., 1989) | Poor validity as a stress model | |

| Dobutamine | — | — | X | Has not been methodically assessed for self-reported physical and mental stress (Wagner et al., 1996) | — | Utility for treatment of heart failure (Pickworth, 1992); may be used as cardiac stress test (Elhendy et al., 2002) | ↑ (Taylor, 1998) | ↓ (Velez-Roa et al., 2003) | Question able validity as a stress model | ||

| Yohimbine | — | — | X | Self-reported stress (Elman et al., 2012) and psychom etric ratings (Umhau et al., 2011) | Anxiety (Tam et al., 2001; Vasa et al., 2009), fear (Kausche et al., 2021) and pain (Ji et al., 2022) | FDA approved for the treatment of the Erectile Dysfunction (Tam et al., 2001) | ↑ (Fricke et al., 2023; Grunhaus et al., 1989; Price et al., 1986) | ↑ (Biaggioni et al., 1994; Petrie et al., 2000; Swann et al., 2013; Tanaka et al., 2000) | Requires safety monitoring for potential hypertension, tachycardia, tachypnea, arrhythmia, bronchos pasm and nausea (Landis and Shore, 1989; Lefton, 2023; Linden et al., 1985; WebMD, 2023) | ||

11. Evaluating the Validity of Stress Models

As displayed in Table 3, stress models can be classified into categories (MedlinePlus, 2021; SAMHSA, 2023) baased on the disposition (mental vs. physical), duration (acute vs. chronic), and causes (natural vs. man-made). Mental stress models target cognitive and emotional faculties (Elman et al., 2018) via tasks eliciting potential psychological discomfort (e.g., public speaking, cognitive challenge, or emotionally upsetting images or sounds). Physical stress models likewise encompass potentially uncomfortable exposures primarily in the somatic domain e.g., hot or cold temperatures (Elman et al., 2018), glucoprivation, hypovolemia (Elman et al., 2012; Elman and Breier, 1997; Elman et al., 2004; Triedman et al., 1993) and other types of homeostatic perturbations. Another critical dimension of stress modeling relates to the duration of the stress exposure. Acute stress models replicate brief, intense stressors, akin to sudden life-threatening situations vs. chronic stress models mimicking the protracted, enduring stressors experienced over an extended period (Elman and Borsook, 2019; Elman et al., 2013; Elman et al., 2009) and resembling the stressors encountered in prolonged adversity or chronic illness (Borsook et al., 2016).

Natural stress models pertain to stressors that occur spontaneously in the environment, such as natural disasters, climate-related stressors, or biological strains whereas man-made stress models involve stressors like social conflicts, job-related stress, or exposure to pharmacological stress-inducing agents (Elman et al., 2012). Man-made stress is obviously more predictable and controllable while natural disasters may arise spontaneously from the environment and can be challenging to replicate in a laboratory setting. The intentional creation of stressors in man-made models can lead to intense and potentially harmful emotional impact, as some researchers tend to push boundaries to study extreme reactions (Bocchiaro and Zimbardo, 2017). Such deliberate infliction of stress raises poignant ethical questions about the potential harm to participants and the boundaries of research practices (Zimbardo, 1973). In contrast, natural stressors can be highly unpredictable and uncontrollable (Anisman and Merali, 1999), making them difficult to study in controlled research settings. This unpredictability can likewise lead to heightened anxiety and distress (Bromet, 2018).

11.1. Clinical Conditions

PTSD.

Due to its essential diagnostic criteria, i.e., experience of an extreme traumatic stressor and persistent reliving of the traumatic event for months or years, PTSD may serve as a naturalistic model of chronic stress (Elman et al., 2005; Elman et al., 2011; Hopper et al., 2008). Here, the use of the term "model" was extended to encompass the reverse translational strategy (Venniro et al., 2020) applying clinical findings to preclinical or basic research settings (Dudek et al., 2021). As a corollary, the PTSD reverse translational model helps to bridge the gap between PTSD clinical observations and experimental studies by integrating clinical findings into experimental designs (Sial et al., 2016) to facilitate a more comprehensive and multidisciplinary approach to studying the impact of environmental factors, neurobiological mechanisms of chronic stress and related disorders, and therapeutic approaches (DePierro et al., 2019).

Construct validity of the PTSD model is defined by specific diagnostic criteria (e.g., re-experiencing, avoidance, negative alterations in cognition and mood, and heightened arousal) providing a clear and reliable diagnostic framework (American Psychiatric, 2022) for a SCID-5- or CAPS-driven structured interview. The latter is the gold standard for determining PTSD’s construct validity including psychometric data on the severity ratings of each diagnostic criterion (Elman et al., 2009). Being based on self-reports, the PCL gleans information on subjective aspects of the PTSD construct. The Mississippi Scale’s (Green et al., 2017) value in the differentiation and specification of the PTSD construct’s validity as a chronic stress model lies in its ability to tailor the assessment to the unique stressors faced in combat vs. civilian traumatic events.

PTSD is associated with significant physiological changes that support its criterion validity as a chronic stress model including the sympathoadrenal (Pan et al., 2018), HPA axis (Schindler-Gmelch et al., 2023) RAAS (Khoury et al., 2012; Seligowski et al., 2021), AVP (Difede et al., 2023; Lago et al., 2021) and immune dysregulation (Katrinli et al., 2022). Yet, the data in this regard is not entirely consistent (Fu, 2022; Pervanidou et al., 2007; Videlock et al., 2008) and even a diminution of the HPA axis’ activity being frequently reported (Fischer et al., 2021; Gola et al., 2012; Szeszko et al., 2018). PTSD’s convergent validity is supported by common co-occurrence with other stress-related conditions, such as major depression, anxiety disorders (Flory and Yehuda, 2015; Grinage, 2003), anhedonia, and affective flattening (Blum et al., 2022; Elman and Borsook, 2019). These comorbidities point to the wide-ranging impact of chronic stress on mental health. On the other hand, the unique aspects of PTSD as a pathophysiological model of chronic stress include the specific etiology (traumatic exposure), triggers and some symptoms profile (e.g., flashbacks and distress from trauma cues exposure). In short, by showcasing the interrelation of mental and physiological processes in the context of chronic stress, PTSD possesses strong construct-, convergent-, and discriminant-validities as a chronic stress The criterion validity is somewhat weaker given the inconstancies of the neuroendocrine data.

Social Defeat.

Social defeat entails prolonged exposure to social adversity such as subordination or humiliation (Bjorkqvist, 2001). As a model of chronic stress, it has been rather extensively investigated in both humans (Bjorkqvist, 2001) and laboratory animals (Toyoda, 2017). The Social Defeat Scale is a standardized psychometric tool assessing the construct of social defeat including items related to helplessness, hopelessness, demoralization, and humiliation (Gilbert and Allan, 1998; Lincoln, 2022). Chronic social defeat is associated with enhanced sympathoadrenal (Ghaddar et al., 2014; Nakatake et al., 2020; Rajalingam et al., 2021) and HPA axis’ (Cannizzaro et al., 2020; Iob et al., 2021; Laceulle et al., 2017; Marini et al., 2006; Niraula et al., 2018) activity as well as enhanced RAAS’ (Berton et al., 1999; Brouillard et al., 2019)-, AVP (Litvin et al., 2011; Wotjak et al., 1996) and immune system’s (Ishikawa et al., 2021) responses demonstrating criterion validity. As is the case for other stressors, neuroendocrine alterations initially contribute to adaptive increases in blood pressure and water retention. However, continuous state of defeat leads to various ailments, particularly cardiovascular problems as well as inflammatory states and altered immune cell distribution (Samuels et al., 2023).

Chronic social defeat is often linked to related constructs such as bullying (Bjorkqvist, 2001), burnout, work-related stress (van der Molen et al., 2020), aggression, humiliation (Bjorkqvist, 2001; Rohde, 2001), discrimination (Lincoln, 2022) and specific social situations like debating with a member of the opposite gender (Bjorkqvist, 2001; Rejeski et al., 1989). The presence of associations between social defeat and these related constructs supports convergent validity capturing essential aspects of chronic social stress. Animal models, such as the "resident-intruder" procedure (Koolhaas et al., 2013), are used to model social defeat situations in laboratory settings through aggressive encounters (Munshi et al., 2022). Parallel findings in human and animal studies enhance the convergent validity (Morais-Silva et al., 2019). While major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and schizophrenia (Bjorkqvist, 2001; Laviola et al., 2004; Rohde, 2001; Selten et al., 2013) clinical presentation establishes that they may share some symptoms with social defeat in terms of hopelessness, social withdrawal and emotional numbing, their distinct diagnostic criteria and symptom profiles position social defeat as a distinctive model of chronic social stress pointing to the discriminant validity.

11.2. Laboratory-Based Stress Tests

The TSST.

While challenges introduced by laboratory-based procedures (e.g., TSST) may lack ecological validity in representing daily life or real-world events (Allen et al., 2017), they hold mechanistic significance as their mental and physiological effects are like those produced by authentic stressors (Bamert and Inauen, 2022). The TSST is a popular laboratory-based procedure for induction of acute psychological stress through two structured challenges viz., job interview and math exercise (Frisch et al., 2015). The former component may be extended to other type of challenges within the framework of the Trier Mental Challenge Test e.g., time pressure or loud (75 dB) noise (Kirschbaum, 1991) adapted for use during positron emission tomography or functional magnetic resonance imaging as a part of the Montreal Imaging Stress Task (Dedovic et al., 2005).

After a short (minutes) preparation subjects participate in a simulated job interview striving to appear qualified applicants to an unresponsive panel of “experts.” An unexpected cognitive challenge in the form of math questions is added to the social evaluation and it enhances the overall stress experience (Allen et al., 2017; Bauerly et al., 2019). Individuals subjected to the TSST consistently report increased levels of stress during the task (Hellhammer and Schubert, 2012; Mohiyeddini et al., 2013) i.e., construct validity. Moreover, the TSST reliably triggers physiological responses including the heightened activity of the sympathoadrenal system (Bremner et al., 1996), HPA axis (Gabrys et al., 2019; Hellhammer and Schubert, 2012), RAAS (Gideon et al., 2020; Gunes Ozunal, 2021), AVP (Spanakis et al., 2016; Tabak et al., 2022) and immune (Allen et al., 2014) systems, supporting the criterion validity of neuroendocrine and immune changes characteristic of acute stress. The TSST’s convergent validity is evident in the consistent physiological and psychological responses across the interview preparation, public speaking, and mental arithmetic components (Frisch et al., 2015) in conjunction with the concurrent anxiety and insecurity (Hellhammer and Schubert, 2012). Despite the psychosocial nature of the TSST, its effects extend beyond the psychological realm to robust and reliable neurobiological changes e.g., growth hormone and prolactin (Kirschbaum et al., 1993) showing discriminant validity as the TSST captures unique aspects of acute stress beyond psychological dimensions (Allen et al., 2017).

The TSST faces certain limitations. Extraneous factors, such as the gender composition of the panel evaluating participants and nonverbal cues seem to influence test results, potentially compromising its ecological validity (Allen et al., 2014; Allen et al., 2017; Narvaez Linares et al., 2020). Moreover, the TSST's design combines different types of stressors, making it challenging to isolate which specific aspect of the test drives the physiological response (Allen et al., 2017). Furthermore, the test does not appear to trigger distinct physiological stress responses based on individuals' personality factors (Gaab et al., 2005). Even so, the TSST remains a valuable tool for studying the cumulative effects of acute psychological stressors in a controlled laboratory setting.

The MAST is an experimental acute stress model involving submergence of a hand in ice water for varying controlled durations (not exceeding 90 seconds, in total over ten minutes). Between submergence trials, subjects perform math tasks with negative feedback from an observer in case of a mistake (Shilton et al., 2017; Smeets et al., 2012). The MAST protocol consistently demonstrates construct validity via self-reports of acute stress (Smeets et al., 2012; van Ruitenbeek et al., 2021) and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) measuring psychological stress response (Elman et al., 2010; Karlsgodt et al., 2003) associated with the MAST (Shilton et al., 2017). The MAST effectively triggers activation of the sympathoadrenal system and the HPA axis evident in significant increases in blood pressure, alpha-amylase (Takai et al., 2004) and cortisol levels (Le et al., 2021; Shilton et al., 2017; Smeets et al., 2012) that is to say, criterion validity. The convergent validity of MAST is supported by the common components with other established stress models, such as the TSST and the Cold Pressor Test (Smeets et al., 2012) as well as the exposure to a challenging task in the presence of an observer (Quaedflieg et al., 2013). Yet again, the combination of both components to segregate cognitive and physiological aspects is unique; hence is the discriminant validity.

The Stroop Test.

Because people are accustomed to reading words rather than identifying the colors of the ink they are written in (Prevor and Diamond, 2005), the Stroop test creates cognitive conflict with consequent mental stress by presenting color names written in incongruent ink colors (Jensen and Rohwer, 1966). This stress construct is elicited by psychometric scales as subjects struggle to complete the task (Renaud and Blondin, 1997; Tulen et al., 1989). During the test, subjects consistently increase sympathoadrenal activity evident in the heart rate, heart rate variability and skin conductance findings (Huang et al., 2021; Renaud and Blondin, 1997; Vazan et al., 2017) together with activation of the HPA axis (Compton et al., 2013; Young Kuchenbecker et al., 2021), which is the evidence of criterion validity.

The Stroop test also demonstrates convergent validity by affecting various psychological processes including anxiety, working memory, complex information and attention and speed of processing (Herd et al., 2006; Parris et al., 2022; Perianez et al., 2021; Tulen et al., 1989). Engagement of the anterior cingulate- and dorsolateral prefrontal cortices by Stroop is a consistent finding on neuroimaging studies (Milham et al., 2003; Spaniol et al., 2009). While these areas are associated with cognitive control and conflict resolution, their consistent activation in Stroop performance distinguishes it from other stress models that may involve different neural pathways or regions (discriminant validity).

11.3. Biological Stressors

Infection.