Abstract

The properties of colloidal quantum-confined semiconductor nanocrystals (NCs), including zero-dimensional (0D) quantum dots, 1D nanorods, 2D nanoplatelets, and their heterostructures, can be tuned through their size, dimensionality, and material composition. In their photovoltaic and photocatalytic applications, a key step is to generate spatially separated and long-lived electrons and holes by interfacial charge transfer. These charge transfer properties have been extensively studied recently, which is the subject of this Review. The Review starts with a summary of the electronic structure and optical properties of 0D–2D nanocrystals, followed by the advances in wave function engineering, a novel way to control the spatial distribution of electrons and holes, through their size, dimension, and composition. It discusses the dependence of NC charge transfer on various parameters and the development of the Auger-assisted charge transfer model. Recent advances in understanding multiple exciton generation, decay, and dissociation are also discussed, with an emphasis on multiple carrier transfer. Finally, the applications of nanocrystal-based systems for photocatalysis are reviewed, focusing on the photodriven charge separation and recombination processes that dictate the function and performance of these materials. The Review ends with a summary and outlook of key remaining challenges and promising future directions in the field.

1. Introduction

The intrinsic electronic properties of bulk semiconductor crystals are determined by their chemical composition and lattice structure. When the crystal is small enough, its energy levels can also be tuned by its size through the quantum confinement effect.1−4 The effect occurs when the crystal dimension is smaller than the exciton Bohr radius, which is usually in the scale of a few to tens of nanometers.5−7 These quantum-confined nanocrystals (NCs) can be classified as zero-dimensional (0D) quantum dots (QDs), one-dimensional (1D) nanorods (NRs), and two-dimensional (2D) nanoplatelets (NPLs), with their exciton motions confined in three, two, and one dimensions, respectively (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

0D, 1D, and 2D nanocrystals. (A) Representative transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of colloidal 0D, 1D, and 2D CdSe nanocrystals (NCs), which are also termed quantum dots (QDs), nanorods (NRs), and nanoplatelets (NPLs), respectively. (B) Schematic plots of density of states (DOS) as a function of energy for 3D (bulk), 2D, 1D, and 0D systems. (C–E) Static absorption spectra of (C) a series of CdSe QDs with various diameters from 1.2 to 11.5 nm, (D) CdSe NRs with three different diameters, and (E) CdSe NPLs with three different thicknesses. The thickness-dependent photoluminescence (PL) spectra of NPLs are also plotted in (E). (B) Adapted from ref (75). Copyright 1996 American Association for the Advancement of Science. (C) Adapted from ref (8). Copyright 1993 American Chemical Society.

Different from the bulk materials, the band gap absorption and emission energy of quantum-confined NCs can be tuned over a wide range by changing the size of the quantum-confined dimensions. Taking CdSe QDs as an example, their size-tunable band gap range from 1.8 to 3.0 eV.8 Semiconductor NCs also have a high surface area and a much larger absorption coefficient (typically in the range of ∼105–107 cm–1 M–1) than molecules.9−13 The spatial locations of the conduction band electron and valence band hole can also be controlled by forming NC heterostructures composed of two or more components to enable novel exciton and charge separation properties.14 Finally, quantum-confined NCs have also been shown to facilitate multiple exciton generation, in which one high-energy absorbed photon can lead to the generation of two or more lower energy excitons. These features combined to make quantum-confined NCs a unique class of emerging materials for solar energy conversion.15−21 Both the solar-to-current conversion efficiency of QD solar cells22 and the solar-to-hydrogen conversion efficiency of QD-based photoelectrochemical cells23 have been reported to exceed 100%.

Since the initial discovery, various properties of quantum-confined nanocrystals and their applications have been extensively studied in the last 40 years, and the increasing recognition of the importance of these materials has led to the 2023 Nobel Prize in Chemistry to Moungi Bawendi, Louis Brus, and Alexei Ekimov for their pioneering contributions to the discovery and synthesis of quantum dots.1−4,8 This Review focuses on the applications of quantum-confined nanocrystals in solar energy conversion and the key process essential to these applications, i.e., charge transfer to and from NCs. Optical excitation of NCs generates bound electron–hole pairs (or excitons) in semiconductor NCs, which can be dissociated to form separated electrons and holes to generate photocurrent and conduct redox reactions in photovoltaic and photosynthetic cells, respectively.24 The studies of charge transfer from NCs trace back to the 1980s when Brus and co-workers measured electron transfer from CdS QDs to methyl viologen via transient Raman spectroscopy25,26 and Kamat and co-workers studied electron transfer from CdS QDs to methylene blue using nanosecond laser flash photolysis and microwave absorption techniques.27 Although much of the research in this field in the late 1980s and 1990s focused on synthesis, emission properties, spectroscopic characterization, and photophysics of quantum dots,8,28−33 charge transfer from QDs was studied in the pioneering works by El-Sayed and co-workers34 and Zhang and co-workers35 using sub-picosecond transient absorption (TA) spectroscopy. Interest in the time-resolved study of charge transfer processes from QDs has grown considerably since then; Kamat and co-workers reported charge transfer from QDs to TiO2 nanoparticles in QD solar cells,36−40 Nozik and co-workers studied electron and hole transfer from InP QDs and their heterostructures,41−43 Klimov and co-workers demonstrated a new approach to the sensitization of Ru complexes via charge transfer from CdSe QDs,44 Lian and co-workers reported ultrafast interfacial electron and hole transfer from QDs to molecular acceptors by TA and single-particle photoluminescence (PL) decay,45−48 and Alivisatos reported electron transfer from CdSe/CdS NRs to Pt tips and how it affects the light-driven H2 generation performance of this semiconductor–metal heterostructure.49 These early works are followed by an explosion of detailed studies of charge transfer from quantum-confined QDs, NRs, and NPLs and their applications of photocatalysis and solar energy conversion.

Advances of charge transfer to and from NCs have been covered in some review articles. Early reviews focus on photochemistry and redox reactions on the surface of non-quantum-confined colloidal nanocrystals and nanocrystalline thin films.50,51 Interfacial charge transfer in donor–bridge–acceptor systems on nanoparticles and bulk metals52 and in solar energy conversion systems, including QD-sensitized solar cells,16,53,54 has also been reviewed. Charge transfer dynamics from quantum-confined NCs to molecular acceptors,55−57 redox enzymes,58 and 2D transition metal dichalcogenides59 have been subjects of more recent review articles, including a comprehensive Review published in this journal.55 Advances in the use of quantum-confined nanocrystals in photocatalytic reactions, including QDs,60,61 NRs,62,63 and NPLs,64 have also been reviewed. Most of these review articles focus on charge transfer from one nanocrystal morphology or type of electron acceptors. In this Review, we aim to provide a comprehensive review of charge transfer processes from 0D, 1D, and 2D quantum-confined nanocrystals, focusing on their dependence on the nanocrystal dimensionality. This Review will not cover triplet energy transfer from QDs to molecules,65,66 and charge transfer from perovskite NCs,67−70 which have received intense interest in recent years. Significant advances have also been made in the field of using microcrystals for photocatalysis,71−73 which is not covered in this article.

In this Review, we first introduce the electronic structure and optical properties of 0D-2D NCs in section 2, which is followed by a discussion of the recent progresses in understanding wave function engineering and carrier dynamics of 0D–2D NC heterostructures in section 3, single carrier (electron and hole) transfer from NCs in section 4, and multiple exciton generation and dissociation in section 5. In section 6, we discuss the design and performance of NC-based photocatalytic systems, with a focus on charge transfer kinetics. At last, we conclude with a summary of key advances and an outlook for future directions.

2. Electronic and Optical Properties of 0D, 1D, and 2D Nanocrystals

2.1. Dimensionality and Size Effects in 0D, 1D, and 2D Nanocrystals

The electronic structure and associated optical spectra of low-dimensional nanocrystals (NCs) can be qualitatively understood by considering two important effects in nanoscience: the dimensionality effect74 and the size effect.2 Dimensionality affects the density of states (DOS) of semiconductors, as qualitatively illustrated in Figure 1B. For a 3D (i.e., bulk) semiconductor, the DOS increases as a function of the square root of excessive energy above the band edge.75 In 2D materials, the DOS increases with energy in a step-like function form. In 1D materials, the DOS exhibits unique Van Hove singularities at the band edges and decreases as a function of the square root of excessive energy above the band edge. Finally, for 0D QDs, the DOS evolves into atomic-like discrete lines. The size effect is more specifically termed the quantum confinement effect. When the size of the NC is smaller than the characteristic length scale of excitons (the so-called exciton Bohr radius), the exciton energy is determined by the physical size of the nanocrystal.28,76 This effect can be approximated by a quantum mechanical “particle-in-a-box” model, which predicts that the transition energy (or the bandgap) of the nanocrystal scales with 1/L2, with L being the length of quantum-confined dimensions (diameter of the 0D QDs and 1D NRs and the thickness of 2D quantum wells).77

The simple dimensionality and size effect considerations can capture some essences of the optical spectra of colloidal NCs. Figure 1C presents the size-dependent absorption spectra of colloidal CdSe QDs synthesized using a hot-injection method.8 The optical gap of the QDs, as determined from the energy of the first transition peak, increases by ∼1.1 eV when the diameter is reduced from 11.5 to 1.2 nm, which is a direct demonstration of the quantum confinement effect. For NRs and NPLs, quantum confinement only exists in two and one dimensions, respectively, along the diameter and thickness directions. As such, tuning the rod diameter and platelet thickness can change the optical gaps of NRs (Figure 1D)20,78,79 and NPLs (Figure 1E),80,81 respectively. However, the absorption spectra of QDs, NRs, and NPLs all deviate significantly from their respective DOS spectra. The deviation results from the effects of nonidealized shapes and heterogeneous distribution of sizes, as well as the oversimplification of the realistic band structure of semiconductors and, for NR and NPLs, the neglect of electron–hole Coulomb interactions and their self-interactions (image charge effect).74,82,83 In the following, we review a higher-level theory that includes these factors and hence can almost quantitatively reproduce the optical spectra of low-dimensional NCs. Specifically, for QDs, because the confinement energy is much higher than electron–hole binding energy, the latter can be treated as a first-order perturbation;4,77 additionally, because the charge distributions of electron and hole virtually compensate each other within the QD, the image charge effect can be ignored.82 For NRs and NPLs, however, the electron and hole are at a distance larger than the diameter of the NR or the thickness of the NPL and interact predominantly through the surrounding medium, which usually has a smaller dielectric constant than the semiconductor itself. This strongly enhances the electron–hole interaction as well as their self-interactions, leading to sizable bandgap renormalization and the formation of strongly bound excitons whose optical features dominate the absorption and PL spectra of NRs and NPLs (see the sharp features on Figure 1D and E).81−83

2.2. Multiband Effective Mass Approximation

For quantum-confined NCs, multiband effective mass approximation (EMA) is often employed to obtain a quantitative picture of the electronic states,77,84 although plane-wave semiempirical pseudopotential methods have also been used.85−87 Within the EMA framework, the wave functions of carriers comprise the envelope wave function part and the Bloch part, which describe carrier motions in the quantum confinement potential and in the rapidly oscillating lattice potential, respectively.88 The applicability of various EMA models is determined by the complexity of band structures in various semiconductors.77 One of the typical band structures for semiconductors having zinc blende lattice symmetry (such as CdS, CdSe, CdTe, GaAs, InAs, etc.) is shown in Figure 2A.77 The conduction band (CB) shows a near-parabolic band at the band edge, whereas the valence band (VB) is much more complicated with a heavy-hole band, a light-hole band, and a spin–orbit split-off band.

Figure 2.

Multiband effective mass approximation (EMA) models. (A) A typical band structure for bulk semiconductors with a zinc blende lattice structure near the Γ-point of the Brillouin zone. The boxes indicate the applicability of various EMA models used for the calculation of electron and hole energy levels and wave functions. (B) Absorption spectrum of CdSe NCs with a mean radius of 4.1 nm. Some of the well-resolved optical transitions are marked by arrows. (C) Energy of the first excited state (1S3/21Se) absorption (black crosses) plotted as a function of 1/radius2 for CdSe QDs and its comparison with EMA calculation results (black solid line). (D) Energy of higher-lying excited states (2S3/21Se and 1P3/21Pe; black squares) with respect to that of the first excited state (1S3/21Se) plotted as a function of the first excited state transition energy. The black solid lines are EMA calculation results. (A) Adapted from ref (77). Copyright 2000 Annual Reviews. (B) Adapted from ref (92). Copyright 2007 Annual Review. (C and D) Adapted from ref (89). Copyright 1996 American Physical Society.

Efros and co-workers have shown that, for large band gap semiconductors such as CdSe, the CB is sufficiently separated from the VB in energy such that the calculation of electron levels and wave functions near the band edge can be approximated by a single parabolic band EMA model and the calculation for holes near the band edge can be performed under the so-called Luttinger–Kohn (LK) model, which accounts for the light- and heavy-hole bands only (Figure 2A). For holes of higher excitation energy, however, the spin–orbit split-off band must also be included using the so-called six-band model.63,89 For narrow band gap semiconductors such as InAs, the mixture between CB and VB needs to be included, which is described by the eight-band Pidgeon–Brown (PB) model.90,91 In the following, we briefly introduce the EMA models for CdSe NCs that treat electrons within the single parabolic band approximation and holes within the six-band approximation, as CdSe is arguably the most prototypical material for quantum-confined NCs. For the calculation of narrow band gap semiconductor nanocrystals such as InAs and PbSe, the readers are referred to other references.71,72

2.2.1. EMA for QDs

Using the simple single parabolic band EMA approximation for electrons in CdSe QDs, the solved envelope wave function is the product of a spherical harmonic and a spherical Bessel function. The energy levels are labeled by their angular momentum Le (with Le = 0, 1, 2, 3... called S, P, D, F... respectively) and radial quantum number ne.89 The first excited state for the electron is the 1Se level. Because the valence band of CdSe primarily arises from p atomic orbitals, it has an inherent sixfold degeneracy near the band edge (k = 0). The spin–orbit coupling splits this degeneracy into a fourfold degenerate J = 3/2 band and a twofold degenerate J = 1/2 band. J is the total unit-cell angular momentum J = l + s, with l and s being the orbit and spin angular momentums, respectively. The J = 3/2 band is further split into the Jm = ± 3/2 heavy-hole band and the Jm = ± 1/2 light-hole band at k > 0. Taking into consideration this complex band structure (Figure 2A) in the six-band EMA model, the solution to a spherical confinement potential shows significant mixing between the bulk valence band levels. As a result, neither the total unit-cell angular momentum J nor the envelop angular momentum Lh is a good quantum number. Rather, one needs to introduce the total angular momentum F, where F = J + Lh. QD hole states are commonly labeled as nhLF. Note that because of the mixing QD hole states nominally labeled as Lh have contributions from both Lh and Lh + 2 spherical harmonics (the so-called “S-D mixing”).88,89 For example, the first excited hole state 1S3/2 contains three hole components: (F = 3/2, J = 3/2, Lh= 0), (F = 3/2, J = 3/2, Lh= 2), and (F = 3/2, J = 1/2, Lh= 2). The total QD wave function is the product of the individual electron and hole components. The optical selection rules are calculated from the overlap integral between electron and hole envelop functions, which should be Δn = 0 and ΔL = 0 in the simplest case. In reality, however, this selection rule does not apply due to the hole state mixing; for example, transitions from both S and D hole states into S electron states are allowed.

This six-band EMA model captures almost all the important features in the electronic structure of QDs. The absorption spectrum of a R = 4.1 nm CdSe QD sample in Figure 2B clearly shows the features of optically allowed electron–hole pair states, with the three lowest energy states being 1Se1S3/2, 1Se2S3/2, and 1Pe1P3/2, consistent with theoretical calculations.92Figure 2C compares the experimentally measured and theoretically calculated size-dependent energy for the band edge 1Se1S3/2 transition, showing good agreement except for very small and large size QDs.89 Note that in order to calculate optical transition energies the electron–hole Coulomb interaction needs to be accounted for. For QDs with strong quantum confinement, this binding energy can be treated as a first-order perturbation, and for spherical QDs it is calculated to Eb = −1.8e2/(εr), with ε and r being the high-frequency QD dielectric constant and radius, respectively. In addition to the band edge transition, the experimentally measured size-dependent energy difference between 1Se2S3/2 (or 1Pe1P3/2) and 1Se1S3/2 transitions (Figure 2D) can also be reproduced from the theory.89 Overall, results show that the six-band EMA model allows for a quantitative description of the electronic and optical properties of CdSe QDs.

2.2.2. EMA for NRs and NPLs

EMA models have also been applied to calculate the electronic structures of 1D NRs and 2D NPLs.81,82,93,94 Here we briefly review the results on CdSe NRs and NPLs. The basic idea is to treat the dimensions with and without quantum confinement separately using the adiabatic approximation, as the carrier motions along the quantum-confined direction(s) are much faster than those along the unconfined direction(s).82 For the calculation of CdSe NRs, Efros and co-workers treat them as ellipsoids with major semiaxis length b (the NR axis) much larger than the minor semiaxis length a (the NR radius).82 The quantum-confined fast motion in the radial direction is first solved using the EMA models and then the axial motion is treated by averaging the position over the fast radial motion.82 Similar to QDs,29,77,84,95 the excited states of electrons and holes in the radial direction are calculated using the single-band and six-band EMA models, respectively. A distinction from QDs is that, because of symmetry of NRs, electron states are characterized by the angular momentum projection (m) on the NR axis and labeled as nΣe, nΠe... for |m| = 0, 1... and n is the number of the level for the given symmetry. Due to the mixing effect in the valence band, hole states are characterized by the total angular momentum projection (jz) on the NR axis: jz = m + Jz, where Jz is the projection of the hole spin on the NR axis (Jz = ±1/2, ±3/2...). These states are labeled as nΣ|jz|, nΠ|jz|..., respectively.

Based on the optically allowed transitions between these quantum-confined electron and hole levels, Efros and co-workers first calculated the diameter-dependent “bare” gaps of CdSe NRs (Figure 3A), which are defined as the energy difference between the band edge electron and hole states (without the electron–hole binding energy) and should match the gap measured by STM tunneling current experiments. However, Figure 3A shows that the calculated diameter-dependent “bare” gaps for NRs deviate significantly from the tunneling data (by ∼100–200 meV). This is a consequence of bandgap renormalization due to the dielectric confinement effect that strongly enhances charge self-interactions in 1D NRs. As mentioned above, the dielectric confinement effect also strongly enhances the electron–hole binding energy. It is interesting to note that the increases in the charge self-interaction energy and the electron–hole binding energy almost exactly compensate each other. As a result, the exciton transition energy or the optical gap remains largely unaffected by the dielectric confinement effect. For example, Efros and co-workers calculated the electronic structure of 2D CdSe NPLs using an eight-band EMA model.81 The eight-band EMA model was used for improved accuracy, although six-band EMA should, in principle, be sufficient for CdSe NPLs. In their calculation, they ignored the contribution of the self-interaction terms as well as the increase of the binding energy and simply used a 2D limit for binding energy: Eb = 4Eex, where Eex is the exciton binding energy in bulk semiconductors. As shown in Figure 3B, this calculation reproduces the thickness-dependent optical gaps of CdSe NPLs. However, if one needs information on the bandgap renormalization effect and electron–hole binding energy in 1D and 2D nanocrystals, the dielectric confinement effect should be calculated, as we review below.

Figure 3.

Dielectric confinement effect in NRs and NPLs. (A) Diameter-dependence of the tunneling and optical energy gap in CdSe NRs. Dotted and dashed lines show bare and self-interaction-corrected energy gaps between the 1Σ1/2 hole and the 1Σe electron sub-band. Two solid lines show the optical transition energy for the first two optically active 1D excitons. Experimental data for the tunneling and optical gap measured in CdSe NRs from ref (96) are shown by empty circles and filled squares. (B) Thickness-dependent energies of the electron/light-hole (green circles) and electron/heavy-hole (black circles) optical transitions and their comparison with EMA calculations (solid lines). (C) Schematic illustration of the “bare”, tunneling, and optical gaps and dielectric-confinement-induced electron (hole)–image charge-repulsive self-interaction and enhanced electron–hole attraction. (D) Single-particle self-interaction energies as a function of an external medium dielectric constant (εext), with the CdSe dielectric constant fixed at 6, for CdSe NPLs with thicknesses of 3 (black squares), 5 (red circles), and 7 (blue triangles) monolayers calculated using an advanced tight-binding model. (E) Electron/heavy-hole transitions energies calculated for 1S (red circles), 2S (green triangles), 1P (blue triangles), and ∞S (approaching optical gap; black squares) as a function of the NPL thickness using εext = 2. (A) Adapted with permission from ref (82). Copyright 2004 American Chemical Society. (B) Adapted with permission from ref (81). Copyright 2011 Springer Nature. (C) Adapted with permission from ref (20). Copyright 2016 Royal Society of Chemistry. (D and E) Adapted with permission from ref (83). Copyright 2014 American Physical Society.

2.3. Dielectric Confinement Effect in 1D NRs and 2D NPLs

The dielectric confinement effect arises from the difference between the dielectric constants of 1D and 2D semiconductors (εs) and their external medium (εext).97 First, it enhances the (repulsive) self-interactions of electrons and holes with their image charges, thus leading to a sizable increase in the quasi-particle gap (bandgap renormalization),98 as illustrated in Figure 3C. On the other hand, it also strongly enhances the electron–hole attractive interactions, resulting in a large exciton binding energy that lowers the optical gap considerably from the quasi-particle gap. In their calculation for CdSe NRs, Efros and co-workers calculated Coulomb interactions enhanced by the dielectric contrast effect using U(re, rh) = −e2/(εs|re – rh |) – eV(re, rh) + eV(re, re) + eV(rh, rh), where the first and second terms are electron–hole interaction potentials through inside and outside the NR, respectively, and the last two terms are electron and hole self-interaction potentials.82 By averaging U(re,rh) over the electron and hole wave functions in the radial direction, they obtained a 1D potential profile of electron–hole (e-h) Coulomb interaction and electron (hole) self-interaction corrections to their quantum-confined energy levels. As shown in Figure 3A, after adding the self-interaction corrections to the energy difference between the band edge electron and hole states, the “bare” gaps increase by ∼100–200 meV and become consistent with the experimentally measured tunneling gaps. The two lowest optically allowed excitonic transitions obtained by solving the 1D e-h potential are shown in Figure 3A. The diameter-dependent energies for the ground excitonic states match the experimental optical gaps well. Also, it can be seen that the energy of the ground excitonic state is lower than the tunneling gap by ∼150 meV, which reflects the large exciton binding energy in CdSe NRs.

Similar calculations have been performed on 2D CdSe NPLs.83,99Figure 3D shows the calculated electron and hole self-interaction energies as a function of the dielectric constant of the external medium εext for NPLs with different thicknesses.83 The self-interaction energies increase considerably as εext decreases, and this effect is more obvious for thinner CdSe NPLs, indicating that the dielectric confinement effect is stronger for thinner NPLs and for the situation with a smaller εext. For the 3 monolayer (ML) CdSe NPLs, when εext is 1 (i.e., in the air), electron and hole self-interaction energies reach ∼300 meV and the total bandgap renormalization reaches ∼600 meV. Figure 3E shows the calculated thickness-dependent electron and hole binding energies for εext = 2, which decrease from ∼100 meV for 3 ML NPLs to ∼50 meV for 7 ML NPLs.83 Similar dielectric-contrast-enhanced strongly bound excitons have been observed in many other 1D and 2D material, such as carbon nanotubes, graphene, and monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides.74,98,100−104

2.4. Exciton Fine Structure and Lifetime in 0D, 1D, and 2D Nanocrystals

Besides the spectral properties, it is also important to understand the dynamic properties of quantum-confined NCs, as they dictate the time window available for charge extractions from these NCs. The electron–hole recombination dynamics in NCs are determined by the trap states and the fine-structures. The trapping process is usually much faster than the radiative recombination process; for example, the hole trapping in CdSe QDs can be as fast as ∼10 fs.105 Therefore, in QD ensembles, QDs with traps are dominated by the nonradiative recombination between the CB edge electron and trapped hole, while QDs without traps undergo radiative recombination between band edge carriers with their dynamic properties controlled by the fine structure of their band edge excitons. In 1D NRs and 2D NPLs, other factors such as giant oscillator strength transition effect further modify the band edge exciton radiative lifetime in addition to the fine structure.

The fine structure of the band edge 1Se–1S3/2 excitons of CdSe QDs, as developed by Efros, Bawendi, and co-workers,28,29 is schematically shown in Figure 4A. The splitting of the fine structure is mainly induced by the combined effect of short- and long-range electron–hole exchange interactions and anisotropies associated with the crystal field and nanocrystal shape asymmetry.106 The exchange interaction is typically weak (at most a few meVs) for bulk inorganic semiconductors and thus is often ignored, unlike the strong interaction that leads to large singlet–triplet splitting in organic materials. In NCs, however, the quantum-confinement-induced strong electron–hole wave function overlap enhances the exchange interaction energy up to tens of meVs. As a result, one should consider a correlated band edge exciton, rather than independent electron and hole, with a total angular momentum of N (N = 1 or 2). N = 1 corresponds to a high-energy optically active exciton (so-called “bright” exciton), whereas N = 2 is a lower-energy optically passive exciton (so-called “dark” exciton), as a photon can only carry a momentum of 1. Due to the asymmetric crystal field and NC shape, the good quantum number is the projection of the total angular momentum along the unique crystal axis (Nm) and hence the N = 1 and 2 states are further split into two manifolds of states (Figure 4A). The new lowest-energy state is still a “dark” exciton characterized by Nm = ±2, and the next higher-energy state is a “bright” exciton with Nm = ±1.

Figure 4.

Exciton fine structure and lifetime. (A) Scheme of the fine structure of the band edge 1Se–1S3/2 excitons of CdSe QDs. The fine structure splitting is mainly introduced by anisotropic effects and e-h exchange interactions. (B) Time-resolved PL decay curves measured for typical CdSe QDs at indicated temperatures. (C) Scheme of the fine structure of the band edge excitons of perovskite NCs. Here the fine structure splitting is mainly introduced by e-h exchange interactions and the Rashba effect under orthorhombic symmetry. (D) Time-resolved PL decay curves measured for single CsPbI3, CsPbBr3, and CsPbBr2Cl perovskite NCs at cryogenic temperatures. (E) Bright–dark splitting of CdSe NPLs (ΔEAF) as a function of the reciprocal of NPL thickness (1/L). Crosses and circles represent results measured by PL line narrowing and temperature-dependent time-resolved PL, respectively. (F) Time-dependent PL decay curves measured for typical CdSe NPLs at indicated temperatures. (A and B) Adapted with permission from ref (88). Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society. (C and D) Adapted with permission from ref (107). Copyright 2018 Springer Nature. (E) Adapted with permission from ref (108). Copyright 2018 Royal Society of Chemistry. (F) Adapted with permission from ref (81). Copyright 2011 Springer Nature.

The splitting between the “dark” and “bright” excitonic states is in the range of a few to 10 meV, with smaller QDs having larger splitting due to stronger electron–hole exchange interactions. This splitting controls the temperature-dependent radiative recombination dynamics of band edge excitons. As shown in Figure 4B, at very low temperatures excitons primarily occupy the “dark” state and thus recombine on a μs time scale. With increasing temperatures, excitons more and more occupy the “bright state”, resulting in faster radiative recombination. At room temperature, the thermal energy (∼26 meV) is sufficiently high as compared to the dark–bright splitting energy of a few meV. As a result, excitons are approximately distributed equally between the “dark” and “bright” states, leading to a lifetime of ∼20 ns for typical CdSe QDs. This intrinsic exciton lifetime is longer than the time constants for many interfacial charge transfer from QDs and hence is often not a limiting factor for efficient charge extraction from QDs.

The band edge exciton structures of most QDs can be explained by the picture depicted above. The recently introduced lead halide perovskite nanocrystals (NCs), however, likely feature a different type of fine structure. These NCs have large extinction coefficients and exceptional light-emitting properties; as-synthesized NCs can attain emission quantum yields in the range of 50–90% without any postsynthetic treatments.109 To account for these properties, Efros and co-workers theoretically examined the fine structure of perovskite NCs and proposed a structure with a “bright” triplet state as the lowest-energy band edge state.107,110 Specifically, because the top of the valence band is contributed by Pb 6s and Br 4p atomic orbitals with an overall s-like symmetry, the band edge hole state has Jh = 1/2, which is different from that of CdSe QDs. The electron–hole exchange interaction mixes the angular momentum of the electron and hole states to form a J = 0 singlet state and a threefold degenerate J = 1 triplet state, with the former being “dark” and the latter “bright” (Figure 4C). The singlet state would lie below the triplet state if only considering the electron–hole exchange interaction. These perovskite NCs, however, exhibit a strong Rashba effect due to strong spin–orbital coupling and breaking of inversion symmetry. The reasons for the inversion asymmetry remain unclear but are likely related to cation positional instabilities or surface effects. The Rashba effect inverts the energetic order between the singlet and triplet states, leading to a unique fine structure featuring a lowest-energy “bright” triplet state (Figure 4C). Because of the large oscillator strength of the “bright” triplet state, radiative recombination of band edge excitons in perovskite NCs is very fast (a few ns at room temperature) and accelerates with decreasing temperatures. As shown in Figure 4D, at cryogenic temperatures, the recombination time of band edge excitons can be as fast as 0.18 ns. The fast radiative recombination in perovskite NCs, along with the unique “defect-tolerance” in these materials, is responsible for their exceptional light-emitting performances, which, on the other hand, could also limit the efficiency of charge extraction from these NCs. Nonetheless, ultrafast measurements revealed that interfacial charge transfer from these NCs could be engineered to occur on a ps time scale, thus competing effectively with exciton recombination.111

For fine-structures of CdSe NRs, Efros and co-workers found that the optically dark Fz = 0 state (the projection of the total angular momentum along the rod axis) is situated a few meV below the optically bright Fz = ±1 state, which is partially responsible for the linearly polarized emission from NRs in addition to the dielectric polarization effect, similar to QDs.82 On the other hand, different from the QDs, the order of fine structure states can depend on both the length and radius of the NR.112,113 For fine-structures of CdSe NPLs, Biadala and co-workers measured the PL lifetime of CdSe NPLs as a function of temperatures and applied magnetic fields.114 They found that the PL lifetime increases with decreasing temperatures and that at a constant temperature of 4.2 K the PL lifetime decreases with increasing applied magnetic fields. Using similar PL measurements, Shornikova and co-workers reported the splitting between the bright and dark exciton states as ∼3–6 meV for 3–5 ML CdSe NPLs (Figure 4E).108 All these observations are qualitatively consistent with those of 0D QDs, suggesting similar band edge fine structures. Moreover, due to the large exciton binding energy, Rydberg series of the band edge excitons in CdSe NPLs can be observed under optical measurements,115 similar to transition metal dichalcogenide.100,116 In particular, Achtstein and co-workers observed the emission from the p-state of the band edge exciton in 4 ML CdSe NPLs at low temperature (4 K) with an s- and p-state splitting of ∼30 meV and found that the relaxation rate between p- and s-state of band edge exciton strongly depends on the lateral dimension of the NPL and shows a LO-phonon bottleneck.115 Unlike 0D QDs, the band edge exciton recombination dynamics 2D NPLs are strongly modified by a so-called giant oscillator strength transition effect, which is induced by a coherent extension of the exciton center-of-mass motion along the unconfined dimensions at low temperature due to the suppressed exciton–phonon scattering.81,117−119 This effect leads to a fast radiative recombination of excitons; hence, intrinsic exciton half-lifetimes decrease to sub-ns at low temperatures (<150 K) (Figure 4F).81,119 Because of the fast diffusion of excitons/carriers in NRs and NPLs and the fast interfacial charge transfer from them, this lifetime window is also sufficient to enable efficient exciton dissociation.

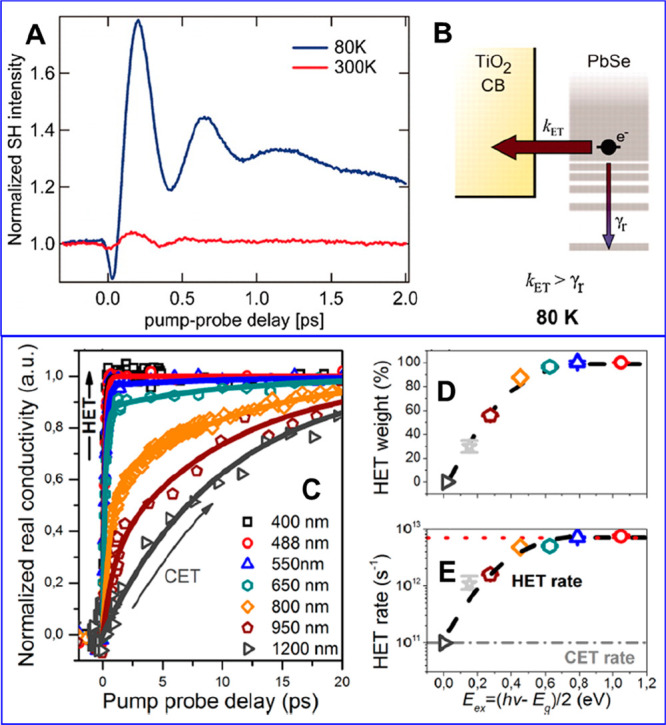

2.5. Effect of Exciton Fine Structure on Transient Absorption Spectral Signatures

Ultrafast pump–probe transient absorption (TA) spectroscopy has been widely used to study the excited charge carrier dynamics in quantum-confined nanocrystals.120,121 The photogenerated exciton, or electron and hole, blocks the ground state excitonic transitions due to the state filling in the conduction band (CB) and valence band (VB), causing an exciton bleach (XB) signal in the TA spectrum. The bleach amplitude can be related to the exciton or electron and hole population according to the band edge exciton fine structures29,122−125 and can be used as a convenient probe of exciton and carrier dynamics in QDs, such as hot carrier cooling,126,127 electron–hole recombination,128,129 Auger processes,130−132 and charge transfer and recombination.121,133,134 It has been reported that both CB electron and VB hole contribute to the band edge XB signal in PbS,135−137 PbSe,121,138,139 and CsPbX3 (X = Cl, Br, I) QDs or nanocrystals140−142 due to the band edge state filling effect. However, in cadmium chalcogenide QDs, such as CdSe,123,124,133,143−145 CdS,146 and CdTe,134,147 the XB is dominated by CB electron state filling effect with negligible VB hole contribution. For example, selectively removing electron from the CdSe or CdS QDs leads to complete XB recovery.148,149 Same XB signal assignment was applied to their nanorods (NRs)150−153 and nanoplatelets (NPLs)154−156 counterparts, as well as InP157,158 and Cd3P2 QDs.159 The lack of a VB hole state filling effect was assumed to result from the high degeneracy of the hole states at VB top and/or the ultrafast hole trapping in these materials.160,161 It is worth noting that, however, the XB decay corresponding to ultrafast hole trapping in CdSe QDs has not been observed even in transient measurements with 10 fs time resolution.105

The VB hole-induced bleach signal in TA spectrum in cadmium chalcogenide QDs was not observed until recently when the hole traps were eliminated in core/shell heterostructures or surface passivation.162−165 Grimaldi et al. showed that the VB hole contributes to 32 ± 2% of the 1S exciton [1S3/2(h)–1S(e)] bleach in CdSe/CdS/ZnS core/shell/shell QDs with a photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) of 82%.162 This hole contribution was measured from the growth kinetics of the 1S XB when the hole relaxes from the 2S3/2 state to the 1S3/2 state. A fourfold degeneracy of the 1S3/2 hole state at the top of the VB was assumed to account for the one-third hole contribution to the exciton bleach, while the band edge exciton fine structure was not considered. In similar CdSe/CdS core/shell QDs with a PLQY of 81%, He at al. reported a hole contribution of 22 ± 1% by fitting the TA spectrum of the single hole state in QDs after selective removal of the CB electron.163 The authors proposed that, in the absence of hole traps, the low hole contribution to the XB signal is mainly due to the exciton fine structure, i.e., the thermal distribution of hole populations in bright and dark exciton states. The hole bleach signal was later reported by Huang et al.166 in TA spectra of Cd-based core/shell QDs and by Brosseau et al.167 in two-dimensional electronic spectroscopy with high energy and time resolutions. Identification of hole-induced absorption bleach implies possible optical gain in Cd-based QDs and helps to rationalize the design of QD lasers.162,166 Moreover, hole-state-filling-induced TA spectra of Cd-based QDs may enable direct probing of the hole transfer process by TA spectroscopy.

3. Wave Function Engineering and Carrier Dynamics in 0D, 1D, and 2D Heteronanocrystals

3.1. Wave Function Engineering in Heteronanocrystals

The spectral and dynamic properties of NCs can be further engineered by building heterostructured NCs such as core/shell QDs. In these heterostructures, the spatial distribution of the wave functions of electrons and holes can be tailored by the sizes and compositions of the constituent materials.168 This is the concept of “wavefunction engineering”. On the basis of the energy offsets of bulk conduction band (CB) and valence band (VB) edges of the constituent materials, the band alignment in semiconductor heterostructures can be classified as type I, quasi-type II, and type II, as depicted in Figure 5A. In a type I structure, both the CB and VB edges of one component are situated within the band gap of the other component, a typical example for which is CdSe/ZnS. As a result, both the lowest-energy electron and hole wave functions are primarily confined in the low band gap material. In contrast, a type II structure features a staggered band alignment with the lower energy CB and VB edges situated on different components, as exhibited in, e.g., CdSe/CdTe. This type of band alignment should lead to spatial separation of electron and hole wave functions into different domains. A quasi-type II structure is the intermediate case between type I and type II structures, with the two components share the same (or similar) CB or VB edge. For example, the VB edges are similar for CdSe and ZnSe, while their CB edges have an offset of ∼0.9 eV.169

Figure 5.

Wave function engineering in heterostructured nanocrystals. (A) Schematic depictions of the band alignments (black lines) and electron (red) and hole (blue) wave function distributions in type I, quasi-type II, and type II core/shell QDs. (B) Schematic of the “giant” NC structure where R is the CdSe core radius and H is the CdS shell thickness (left). Spatial probability distribution of the hole (dark gray area) and electron (light gray area) for an R = 1.5 nm and H = 5.0 nm core/shell QD (right). The inset shows a contour plot of the calculated electron–hole overlap integral. White and black lines are boundaries between regions of (R, H)-space that correspond to different localization regimes. (A) Adapted with permission from ref (168). Copyright 2012 Royal Society of Chemistry. (B) Adapted with permission from ref (179). Copyright 2009 American Chemical Society.

However, because of the quantum confinement effect strongly modifying the band edges of semiconductor NCs, it is important to note that the electronic structure of a heterostructured NC can be different from that of its bulk counterpart. To avoid this confusion, we shall use the term “band alignment” only for bulk materials and the term “electronic structure” for NCs. For example, the VB offset between bulk wurtzite CdSe and CdS is large (≥0.45 V) and the CB offset is relatively smaller (≤0.3 V),170,171 which is a type I band alignment. However, the electronic structure of CdSe@CdS NRs is tunable from type I (with both the electron and hole confined in CdSe) to quasi-type II (with the hole confined CdSe and the electron delocalized among CdSe and CdS) depending on the sizes of the CdSe and CdS domains.171−178

Figure 5B (right) shows the spatial probability distributions (proportional to the square of wave function) of the lowest-energy CB electron and VB hole in CdSe/CdS core/shell QDs with a core radius (R) of 1.5 nm and a shell thickness (H) of 5.0 nm, as calculated using EMA methods.179 The hole wave function is mostly confined in the core, while the electron wave function is delocalized over the whole core/shell, which is a typical signature of quasi-type II electronic structure. Calculations also show that the electron and hole wave function distributions indeed depend sensitively on the R and H parameters, as illustrated by the calculated electron–hole wave function overlap integral in Figure 5B (right inset). When the shell is very thin (small H), both the electron and hole can effectively tunnel into the shell regardless of the core size. As a result, the electron–hole overlap is large, corresponding to the type I regime. Alternatively, in the case of a diminishingly small core, both the electron and hole effectively spill into the shell regardless of the shell thickness, which is also a type I structure; however, this is not a practical case, as it would be very difficult to coat a shell on a diminishingly small core. For a normal core size (R > 1 nm), when the shell becomes thicker, a small core with strong electron confinement energy leads to a delocalized electron and a core-confined hole, which is a quasi-type II structure featuring a smaller electron–hole overlap, whereas a larger core with weaker electron confinement energy results in a core-confined electron and hole in the type I regime.

The concept of wave function engineering has also been extended to 1D hetero-NRs and 2D hetero-NPLs.170,180−184 For example, ZnSe@ZnS dot-in-rod hetero-NRs185 have a type I electronic structure (Figure 6A), whereas ZnSe@CdS hetero-NRs186 have a type II electronic structure (Figure 6B). Particularly interesting are the CdSe@CdS dot-in-rod hetero-NRs (Figure 6C), which can attain the same type of wave function engineering from type I to quasi-type II as CdSe@CdS core/shell QDs by simply tuning the core sizes and rod diameters (refs (49, 170−176, 181, 182, 187−206)). The absorption spectrum of CdSe@CdS NRs mainly consists of two features, B1 and B2, that are associated with the lowest-energy exciton states of the rod and the core, respectively (Figure 6C). For NRs with relatively small-size cores, the electron wave function is delocalized from the core to the rod, whereas the hole wave function is still confined in the core (i.e., B1 and B2 share the same electronic level but have different hole levels), forming a quasi-type II structure. For samples with larger cores, both the lowest electron and hole levels are located in the core, forming a type I structure. Experimentally, these electronic structures can be readily probed using TA measurements.173,196,207 Specifically, one can selectively excite the B2 band of the core and monitor its influence on B1 band of the rod.177Figure 6D shows the TA spectra averaged between 1 and 2 ps following B2 excitation for NRs of various lengths with both 2.7 and 3.8 nm diameter seeds. For NRs with a 2.7 nm seed (Figure 6D, top), excitation at B2 leads to instantaneous and simultaneous formation of strong bleaches of both B2 and B1 bands. Since these bleaches are dominated by the CB electron state filling contribution,207 this result indicates that B1 and B2 bands share the same CB electronic level, consistent with a quasi-type II electronic structure.174,207 In contrast, for 3.8 nm seeded NRs (Figure 6D, bottom), excitation at B2 only generates a strong B2 bleach with negligible B1 bleach. The derivative-like feature near B1 bleach is also observed in CdSe core only QDs and can be attributed to a biexciton-interaction-induced shift of higher energy transitions in the core.208 Therefore, these 3.8 nm seeded NRs have a type I electronic structure.

Figure 6.

Wave function engineering in 1D hetero-NRs and 2D hetero-NPLs. (A–C) The absorption spectra (shaded regions) and PL spectra (colored lines) of (A) ZnSe@ZnS, (B) ZnSe@CdS, and (C) CdSe@CdS dot-in-rod hetero-NRs. B1 and B2 transition features on CdSe@CdS NRs are labeled. (D) Averaged transient absorption (TA) spectra of CdSe@CdS hetero-NRs with 2.7 nm (top) and 3.8 nm (bottom) diameter CdSe cores and varying rod lengths at 1–2 ps after ∼580 nm excitation. For comparison, TA spectra of corresponding CdSe QDs with similar confinement energies are also shown. (E) Absorption, PL, and PL-excitation (PLE) spectra of type II CdSe@CdTe core/crown hetero-NPLs. The inset shows the scheme of the hetero-NPL. (F) Absorption and PL spectra of type I CdSe@CdS core/crown hetero-NPLs. Inset shows the scheme of the htero-NPL. (A–C) are reproduced with permission from ref (180). Copyright 2013 Elsevier Ltd. (D) Adapted with permission from ref (177). Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society. (E) is reproduced with permission from ref (209). Copyright 2014 American Chemical Society. (F) is reproduced with permission from ref (210). Copyright 2014 American Chemical Society.

Wave function engineered 2D NPLs have also been reported. For example, growing a CdTe NPL laterally on the edge of a CdSe NPL, or vice versa, leads to core/crown hetero-NPLs with a type II electronic structure (Figure 6E).209,211−218 The strongest evidence for the type II heterostructure is the appearance of an absorption tail with lower energy than both CdSe and CdTe band edge absorptions and the emission associated with this tail (Figure 6E),209 which is the so-called charge-transfer (CT) transition from the top of the CdTe VB to the bottom of the CdSe CB formed due to strong electronic coupling between the two epitaxially attached domains.209,211,218 It is also worth noting that Scholes and co-workers attributed the emission of CdSe/CdTe core/crown NPLs to trapped state emission instead of CT exciton emission, as the latter has a very weak transition strength.219 Type I hetero-NPLs with a CdSe core embedded in a CdS crown have also been reported (Figure 6F).210,213,220,221 Due to the type I electronic structure, photoexcitation energy generated in the CdS crowns can be effectively funneled in to the CdSe cores where light can be emitted.210,221 Owing to the exceptional light-harvesting capability of 2D structures, this funneling mechanism can leads to very high excitation densities at the CdSe cores for light-emitting or conversion applications.213,217,222,223

An important difference between 1D hetero-NRs (2D hetero-NPLs) and 0D core/shell QDs is that the band alignment (or electronic structure) is not the only factor that dictates the wave function distributions of the electron and hole. The strong electron–hole binding in 1D and 2D systems also strongly modifies the wave function distributions. As a result, in (quasi-)type II NRs and NPLs, for example, the electron and hole are not completely delocalized over different domains but instead are localized near the charge separation interface.211

Mauser and co-workers reported the effect of electron–hole binding on electron and hole wave functions in quasi-type II CdSe@CdS tetrapods (Figure 7A-D).198 They calculated the wave functions of the CB electron and VB hole using an EMA model that takes into account e-h Coulomb interactions. The Coulomb attraction energy used in the calculations is 75 meV, which is a lower limit but already significantly affects the electron and hole wave functions. The initially photogenerated electron and hole are delocalized along the CdS rod arms (Figure 7C). The hole wave function is then localized to the CdSe core region due to a large VB offset between the CdSe and CdS. As a consequence of the strong e-h interaction, the electron wave function is also localized in and near the CdSe core instead of delocalized over the CdS arms despite the quasi-type II electronic structure of the tetrapods (Figure 7B). Not only the band edge hole but also a trapped hole can bind strongly to the electron. As shown in Figure 7D, when the hole is localized to a defect state on the CdS arm, the electron wave function is also localized in and near the hole trapping site. In a more recent work, Beard and co-workers showed that even an electron transferred to an acceptor bound to the NR surfaces can strongly localize the hole to near the reduced acceptor.224 As schematically shown in Figure 7E, photoexcitation of CdSe NR–methylene blue (MB) complexes leads to electron transfer from the CdS to MB in ∼3.5 ps, as measured by transient absorption spectroscopy. Additional measurements using time-resolved terahertz spectroscopy indicate that the hole remained in the rod, localized around the reduced MB in ∼11.7 ps. Calculations performed by Efros and co-workers show that, because of the strong electron–hole binding energy that acts as a Coulomb potential well for the hole, the wave function of the lowest energy hole in the bound state is localized to a ∼ ±0.8 nm region near the reduced electron acceptor, and the activation energy to detrap the hole from the potential well can be as large as 235 meV.224

Figure 7.

(A–D) Calculated electron and hole wave functions in CdSe@CdS tetrapods. (A) Energy level plotted along the long axis of one of the tetrapod arms. The arrows indicate the real-space dynamics of the electron and hole transfer to the core (red) or to a trapping site (blue). (B) Electron and hole wave functions at the band edge of the structure with the hole confined in the CdSe. (C) Electron and hole at the band edge states of the CdS rod before relaxation of the hole to the CdSe core. (D) The hole wave function is localized in a low-energy trapping site in one of the CdS arms, resulting in the localization of the electron wave function to the same arm. (E) Schematic illustration of the hole localization after ET from a CdSe NR to adsorbed methylene blue. (F) Coulomb potential well (black line) and hole wave function density distribution, in the lowest two states, in charge-separated CdSe NR–MB. (A–D) Adapted with permission from ref (198). Copyright 2010 American Physical Society. (E and F) Adapted with permission from ref (224). Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society.

In some cases, the electron–hole binding energy is stronger than the energy level offset in heterostructures such that it does not simply modify the wave function but rather completely alters the localization behavior of carriers. As demonstrated by Wu and co-workers, the CB level offset in CdSe@CdS dot-in-rod NRs can be probed by doping an electron into the core and observing the localization behavior of the doped electron.225 They find that for NRs with relative small CB level offset the electronic structure of the NR probed by electron-doping is quasi-type II whereas transient absorption measurement reveal they are type I NRs. Thus, these NRs behave as a quasi-type II structure for a single CB electron but as a type I structure in the presence of an electron–hole pair. All these reports suggest that for 1D and 2D hetero-NCs the band alignment (electronic structure) and electron–hole coulomb interaction codictate the spatial distribution of the electron and hole wave functions. Furthermore, the interfacial strain, introduced by external force or additional growth of heterostructures, also provides strong impact on electronic structure and carrier dynamics of NCs.226 With a sub-100 nm dimension, NC heterostructures can withstand significant elastic deformations, with their equilibrium lattice constant differing from their bulk counterpart. It has been reported that strain can convert the band alignments of CdTe/ZnSe QDs from type I to a type II.227 Moreover, strain also strongly affect carrier relaxation and recombination in CdSe/CdTe228−230 and CdSe/CdS NR heterostructures.226

3.2. Charge Transfer and Transport Dynamics Inside Hetero-NCs

From the standpoint of charge transfer from NCs, wave-function-engineered hetero-NCs are attractive because of their internal charge transfer/separation behaviors that can be used to tailor the rate and yield of charge transfer to external acceptors. As such, it is important to understand charge transfer/separation inside hetero-NCs. For hetero-QDs, we illustrate internal charge separation using CdTe/CdSe type II core/shells (Figure 8A–F).147 The absorption spectra of these QDs shows B1, B2, B3, and C features (Figure 8B). According to EMA calculations, B1 and B2 can be assigned to the CT transitions from the CdTe VB to the CdSe CB, and B3 and C can be assigned to the transitions within CdSe and CdTe, respectively (Figure 8A). The TA spectra of core/shell QDs after 400 nm excitation show that the decay of the bleach of the C feature leads to the concomitant growth of the bleach at the B1, B2, and B3 features (Figure 8C), which can be assigned to interdomain electron transfer from the CdTe core to CdSe shell because the bleach of exciton bands is dominated by the contribution of the CB electron. Fitting the kinetics of these features (Figure 8D) reveals that this internal charge separation process occurred with a time constant of ∼0.77 ps. Similar sub-ps processes have been reported in other type II QDs.231−233 After initial charge separation, all the TA features that correspond to the CdSe CB edge electrons are long-lived (Figure 8E). Fitting the TA features reveals an excited-state lifetime of 62 ns (half-life) for the CB electron, which is more than one order of magnitude longer than that in CdTe core QDs (Figure 8F). Thus, the wave function engineering approach not only effectively localizes the electron and the hole to the shell and the core, respectively, which facilitates electron transfer to external acceptors and suppresses ensuing charge recombination (illustrated in the next section), but also leads to a longer-lived excited state for more efficient charge extraction.

Figure 8.

Charge separation dynamics in type II heterostructured nanocrystals. (A) Band alignment diagram of bulk CdTe/CdSe (black solid lines) and calculated quantum-confined energy levels (colored dashed lines) of CdTe/CdSe QDs. B1, B2, B3, and C transitions are indicated by arrows. (B) Absorption (solid) and emission (dashed) spectra of CdTe seeds (black) and type II CdTe/CdSe core/shell QDs (red). Also shown is a TA spectrum of CdTe/CdSe QDs probed at 1 ps after 400 nm excitation, which clearly shows four bleach bands (B1, B2, B3, and C). (C and E) TA spectra of CdTe/CdSe QDs at selected delays in (C) 0–5 ps and (E) 5 ps to 1 μs following 400 nm excitation. (D) Formation and decay kinetics of the bleaches at the B1, B2, B3, and C bands from 0 to 5 ps. These signals have been scaled by factors indicated in the legend for better comparison. (F) Comparison of the bleach recovery kinetics of B1, B2, and B3 bands in CdTe/CdSe QDs with the exciton bleach recovery kinetics of CdTe seeds. (G) Absorption (red) and emission (blue) spectra of CdSe/CdTe NRs. The inset illustrates three absorption bands: lowest-energy exciton states of CdSe (a) and CdTe (b) and charge transfer (CT) transition (c). (H) TA spectra of CdSe/CdTe NRs (top) and mixed CdSe and CdTe NRs (bottom) at indicated time delays following 620 nm excitation (exciting CdTe). (A–F) Adapted with permission from ref234. Copyright 2011 American Chemical Society. (G and H) Adapted with permission from ref (235). Copyright 2008 American Chemical Society.

Internal charge separation was also reported for CdSe/CdTe type II hetero-NRs (Figure 8G and H).235 The absorption spectrum of CdSe/CdTe NRs contains a, b, and c bands that can be assigned to the 1Σ excitonic feature of the CdSe, the 1Σ excitonic feature of the CdTe, and the CT transition from the CdTe VB to the CdSe CB, respectively (Figure 8G). The PL spectrum of CdSe/CdTe consists of only the CT band emission (Figure 8G), indicating efficient charge separation between CdSe and CdTe domains. These static spectra features are similar to those of type II QDs. The internal charge separation dynamics was investigated using TA spectroscopy by applying a 620 nm excitation pulse that resonantly excites the CdTe 1Σ band (Figure 8H). The CdTe bleach feature forms instantaneously and then shows significant decay within 2 ps, which is accompanied by the growth of the CdSe and CT band bleach. Analysis of the TA kinetics reveals a CdTe-to-CdSe electron transfer time constant of ∼500 fs. In a related work, Zamkov and co-workers measured carrier dynamics in CdS/ZnSe type II nanobarbells and reported an electron transfer time of ∼0.35 ps from the ZnSe tips into the CdS NR.236 These time constants are similar to those reported in CdSe/CdTe core/shell QDs above (∼770 fs147) and also 2D core/crown nanoplatelets (∼640 fs211).

In principle, the electron transfer time in core/shell QDs only contains interfacial electron transfer and that in hetero-NRs or core/crown nanoplatelets contains both interfacial electron transfer and carrier/exciton transport to the interface. The even faster time constant observed in NRs and nanoplatelets indicates that the carrier/exciton transport in these materials is fast and there likely exists charge transfer barrier in curved core/shell interface in QDs caused by interfacial lattice strain.237 These results show that interdomain electron transfer inside these 1D NRs and 2D NPLs are often fast due to fast carrier/exciton transport along the NRs and NPLs and strong electronic coupling between epitaxially grown semiconductor domains.

For 1D NRs and 2D NPLs, surface/interfacial carrier trapping and strong electron–hole binding also play critical roles in the carrier/exciton transport dynamics. These effects in 1D NRs were illustrated in our previous work by studying the length dependence of rod-to-seed exciton localization efficiency in CdSe@CdS NRs.177 Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) maps can be used to accurately determine the rod-to-seed exciton transport distances (Figure 9A).181,195 In these NRs, photoluminescence is dominated by excitons localized in the CdSe seed. Through photoluminescence excitation (PLE) measurements, the rod-to-seed exciton localization efficiency can be determined by comparing the PLE spectra of these NRs to their absorptance spectra (Figure 9B). Specifically, by normalizing the PLE spectra to corresponding absorptance spectra at the B2 band (Figure 9B, inset), the efficiency of exciton localization from the CdS rod into the CdSe seed can be calculated from the ratio of normalized PLE over absorptance.207 The ratio is 1 at >520 nm, decreases gradually at 480–520 nm, and finally levels off at <480 nm, where the CdS rod absorption dominates, to ∼76%, 56%, and 30% for NRs with lengths of 29, 47, and 117 nm, respectively (Figure 9C).

Figure 9.

Competition between exciton transport and trapping in hetero-NRs and NPLs. (A) TEM images of CdSe@CdS NRs with 2.7 nm CdSe cores and different lengths (top, 29 nm; middle, 47 nm; bottom, 117 nm). Insets show the corresponding EDX elemental maps indicating the location of the CdSe core (green). (B) Absorptance (black solid line), PL (blue solid line), and PLE (red dashed line) spectra of NRs shown in (A). The PLE and absorptance spectra have been normalized at the lowest energy exciton peak in the core, as shown by the insets. (C) Wavelength-dependent relative PL QYs of the NRs shown in (A). The shaded areas show regions of gradual decrease of relative PL QYs. (D) Scheme showing the competition between exciton transport to the core through 1D diffusion and exciton localization on the rod through hole trapping (top). Measured (symbols) and simulated (dashed line) exciton localization efficiencies in CdSe@CdS NRs (middle). The efficiency is independent of core sizes: 2.5 nm (blue triangles), 2.7 nm (red circles), and 3.8 nm (green squares). CdS rod absorption cross-section (black solid line) and effective CdSe seed absorption cross section (red dashed line) as a function of rod length (bottom). (E) Schematics of crown-to-core exciton diffusive transport, EDX image, and band alignment in type I CdSe/CdS core/crown NPLs. (F) Schematics of crown-to-core exciton diffusive transport, EDX image, and band alignment in type II CdSe/CdTe core/crown NPLs. (A–D) Adapted with permission from ref (177). Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society. (E) Adapted with permission from ref (221). Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society. (F) Adapted with permission from ref (212). Copyright 2017 American Chemical Society.

The length-dependent exciton localization efficiencies

are modeled

by a 1D diffusion model that includes exciton surface trapping:207 , where DX is the exciton diffusion constant, N(x, t) is the time- and position-dependent

exciton concentration, and τTrap is the exciton trapping

time (0.78 ps).177 This model implicitly

assumes that charge transfer at the CdSe–CdS interface is much

faster than exciton diffusion along the rod. As shown in Figure 9D (middle), with DX as the only fitting parameter, we can simultaneously

fit the localization efficiency for all NRs. The best fit gives a

diffusion constant DX of 2.3 cm2/s, slightly smaller than the bulk value of 3.2 cm2/s.238−242 According to this diffusion constant, exciton diffusion over 10

nm takes ∼0.5 ps (and further scales quadratically with diffusion

length). Based on the length-dependent exciton localization efficiency

in these CdSe@CdS NRs, we define an effective absorption cross section

as a product of the rod absorption cross section and the localization

efficiency, which represents the cross section for creating excitons

in the seed through absorption at the rod.177 As shown in Figure 9D (bottom), the effective seed absorption cross section first increases

with the rod length and approaches saturation at a rod length of ∼100

nm, with an effective seed absorption cross section saturating at

∼3.5-fold of that of the short rod. This result suggests the

existence of an optimal rod length for light harvesting applications.

In addition to CdSe@CdS hetero-NRs, competition between exciton transport

and interfacial trapping was also reported in CdSe tetrapods, which

are homojunctions with a zinc blende CdSe core with four wurtzite

CdSe rod arms.243 Upon exciting the wurtzite

arms, 86% of the excitons are transported to the zinc blende core

with a time constant of ∼1 ps, driven by the CB offset across

the rod/core quasi-type II interface. The remaining 14% form a charge-separated

state across the interface, with the electron in CdSe core and hole

trapped at the CdSe rod.

, where DX is the exciton diffusion constant, N(x, t) is the time- and position-dependent

exciton concentration, and τTrap is the exciton trapping

time (0.78 ps).177 This model implicitly

assumes that charge transfer at the CdSe–CdS interface is much

faster than exciton diffusion along the rod. As shown in Figure 9D (middle), with DX as the only fitting parameter, we can simultaneously

fit the localization efficiency for all NRs. The best fit gives a

diffusion constant DX of 2.3 cm2/s, slightly smaller than the bulk value of 3.2 cm2/s.238−242 According to this diffusion constant, exciton diffusion over 10

nm takes ∼0.5 ps (and further scales quadratically with diffusion

length). Based on the length-dependent exciton localization efficiency

in these CdSe@CdS NRs, we define an effective absorption cross section

as a product of the rod absorption cross section and the localization

efficiency, which represents the cross section for creating excitons

in the seed through absorption at the rod.177 As shown in Figure 9D (bottom), the effective seed absorption cross section first increases

with the rod length and approaches saturation at a rod length of ∼100

nm, with an effective seed absorption cross section saturating at

∼3.5-fold of that of the short rod. This result suggests the

existence of an optimal rod length for light harvesting applications.

In addition to CdSe@CdS hetero-NRs, competition between exciton transport

and interfacial trapping was also reported in CdSe tetrapods, which

are homojunctions with a zinc blende CdSe core with four wurtzite

CdSe rod arms.243 Upon exciting the wurtzite

arms, 86% of the excitons are transported to the zinc blende core

with a time constant of ∼1 ps, driven by the CB offset across

the rod/core quasi-type II interface. The remaining 14% form a charge-separated

state across the interface, with the electron in CdSe core and hole

trapped at the CdSe rod.

The exciton transport behaviors in 2D hetero-NPLs are different from those in 1D NRs. In our previous work, we compared the PLE (monitored at core emission) and absorptance spectra of CdSe/CdS type I core/crown NPLs to quantify the crown-to-core exciton transport efficiency (Figure 9E).221 Using CdSe/CdS core/crown NPLs with the same CdSe core and different CdS crown sizes, we found that the crown-to-core exciton localization efficiency does not depend on the crown size but instead depends on the excitation wavelength, which higher efficiency at higher excitation energy.221 Unlike NRs, CdSe/CdS NPLs have negligible surface trap states on the well-passivated basal planes, and their trap states are concentrated at the core/crown interface, independent of the crown size.244 The wavelength-dependent transport efficiency is attributed to more efficient transport of “hot” excitons with excessive energy (the energy difference between excitation energy and CdS crown band gap) bypassing the interfacial trap.221 Interestingly, for CdSe/CdTe type II core/crown NPLs, the PLE (monitored at CT-exciton emission) and absorptance spectra agree very well with each other, indicating a unity CT-exciton formation efficiency (Figure 9F).211,212 The crown-to-core exciton transport efficiency in type II hetero-NPLs is excitation-wavelength-independent, which is likely because the CT-exciton (with the electron in the CdSe core and hole in the CdTe crown) is formed prior to trapping process and does not require the hole to move across the interface.211,245 Recently, Rao and co-workers also observed emissions from the CdSe core and CdTe crown of CdSe/CdTe NPLs, indicating the CT exciton formation efficiency is not unity.218 Although the emission property may change with the sample quality, all these results have shown that interface of hetero-NPLs is important for both exciton transport and emission.

Due to the uniform quantum confinement along the thickness direction and the giant oscillator strength transition effect, it is speculated that the wave function of the exciton center-of-mass can delocalize throughout the whole NPL, resulting in a ballistic exciton in-plane transport property.246,247 Buhro and co-workers studied single CdSe quantum belts and showed that the spatial distribution of the PL intensity is independent of the excitation location.247 They attributed this result to the exciton center-of-mass motion delocalizing to the whole quantum belt at the room temperature. However, Ma and co-workers have shown recently that the exciton center-of-mass wave function extension at room temperature (∼160 nm2) can be smaller than the NPL lateral dimension.248 In our recent works, we showed that the exciton transports diffusively in both CdSe/CdS and CdSe/CdTe core/crown NPLs.212,221 Take CdSe/CdS type I hetero-NPLs as an example, the exciton bleach of the CdS crown decays slower in larger CdS crowns, indicating slower exciton transport from the larger CdS crowns; correspondingly, the formation of exciton bleach of the CdSe core, which represents the exciton arrival at CdSe core, is slower at larger CdS crowns.221 These size-dependent exciton transport kinetics show that the exciton does not transport ballistically and can be well fitted by 2D in-plane classical diffusion model with a diffusion constants as 2.2 cm2/s and 2.5 cm2/s for CdS and CdTe NPLs, respectively, close to the diffusion constant in bulk crystals.212,221

4. Electron and Hole Transfer from Nanocrystals

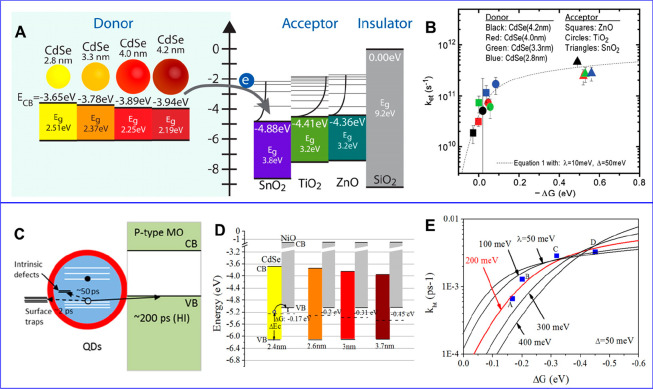

4.1. Nonadiabatic Charge Transfer from QD in a Weak Coupling Regime

In the conventional two-states Marcus model describing electron transfer from a discrete reactant state to a discrete product state, the nonadiabatic electron transfer (ET) rate can be described by eq 4.1.134,249−251

| 4.1 |

Here λ is the reorganization energy of the donor–acceptor system associated with the ET process due to electron–nuclear interaction, |HDA|2 is the electronic coupling strength between initial and final states, and ΔG0 is the free energy difference between the initial state and final state (−ΔG0 is the so-called driving force). Next we will discuss how these factors affect ET rates in QD–acceptor systems and how this model should be modified to count the unique excitonic properties of QDs.134

4.1.1. Reorganization Energy

The total reorganization energy λ contains the inner-sphere contribution (λi) from the nuclear displacement of the donor–acceptor system and the outer-sphere contribution (λo) from the solvent dielectric response (λ = λi + λo). Typically, QD contributes negligibly (<10 meV) to λi because of its weak electron–phonon coupling,252−254 and λi mostly comes from acceptor molecules, which is often in the range of a few hundred meV and can be computed theoretically.251,255,256

The solvent molecules contribute to the charge transfer reorganization energy (λo) mostly through the orientation polarization, and λo can be estimated using dielectric continuum model257

| 4.2 |

where εop and εs are solvent high-frequency optical and static dielectric constants, respectively (therefore, the first bracket reflects the pure solvent orientation contribution); dD and dA are diameters of spherical donor and acceptor cavities, respectively; and rDA is the center to center distance of the spherical donor and acceptor cavities. According to eq 4.2, a nonpolar solvent (such as hexane) contributes negligibly to the reorganization energy because of vanishing orientation contribution. Indeed, Ellis et al. observed similar ET kinetics of QD–methyl viologen (MV2+) complexes dispersed in hexane and under vacuum, consistent with negligible reorganization energy from a nonpolar solvent.250

Various experiments have been attempted to examine the dependence of the ET rate on solvent polarity and thus the effect of reorganization energy.258−260 Cui et al. showed that ET rates between CdSe/ZnS QDs and pyromellitimide did not show a clear correlation with the solvent reorganization energy.258 Similarly, Hyun et al. reported that ET rates from a PbS QD to 10-dodecylanthracene-9-thiol did not correlate with solvent reorganization energy but increased with the static dielectric constant.259 Unfortunately, the acceptor molecules in these studies are soluble in solvents and the ratio between QD donor and molecular acceptors, which affects the apparent ET rate, is poorly controlled, hindering a careful study on solvent reorganization energy.

Charge transfer from QDs to semiconductor films (e.g., TiO2) in principle can circumvent the problem of a poorly defined QD to adsorbed acceptor ratio. Hyun et al. reported that ET rates from a PbS QD to colloidal TiO2 nanoparticles showed weak solvent dependence260 and attributed it to the small solvent contribution as a result of large TiO2 nanoparticles. In principle, the solvent molecules around PbS QD (with much smaller size compared to TiO2) should contribute to the ET reorganization energy. It appears that the solvent-dependent ET rates from QDs as predicted by eq 4.2 have not yet been observed. While better experiment designs may be needed, another possibility could be that the model in eq 4.1 does not adequately describe the ET from QDs,134 as will be discussed later.

4.1.2. Electronic Coupling

Electronic coupling strength dependence can be most conveniently examined in donor–bridge–acceptor (D-B-A) complexes, in which the donor–acceptor coupling strength depends on the donor chemical nature and geometrical factors, acceptor, and bridge.261 If ET occurs by tunneling through the bridge, the electronic coupling strength, and thus the ET rate, depends exponentially on the donor–acceptor distance.261,262

An unique and precise way to tune the QD–acceptor distance and ET electronic coupling strength is through an inorganic barrier layer between the QD and acceptor with controlled thickness, e.g., using core/shell QDs.147,263−267 Using a CdSe/ZnS type I core/shell QD-anthraquinone (AQ) complex and by varying ZnS shell thickness (Figure 10A), Zhu et al. found both the electron transfer (or charge separation, kCS) and back electron transfer (or charge recombination, kR) rates decay exponentially with the shell thickness (d).

| 4.3 |

Here k0 is the CT rate at d = 0 and the exponential decay constants β were reported to be 0.35 ± 0.03 Å–1 and 0.91 ± 0.14 Å–1 for the electron and hole transfers, respectively.263 More interestingly, the ET and HT rate decay constants agree well with the exponential decrease of 1S electron and hole surface density, respectively (Figure 10B). This result confirms that the ZnS shell serves as a tunneling barrier for the electron and hole transfer and slows down their rates by decreasing the electronic coupling with the adsorbate. Besides electron transfer, Ding et al. systematically investigated the hole transfer process from CdSe/CdS core/shell QDs to three different ferrocene hole-accepting molecules (Figure 10C) and found a general exponential dependence of hole transfer rates on the CdS shell thickness (Figure 10D).264,265 Similar shell-thickness-dependent CT behavior has been also observed in ZnTe/CdSe core/shell QDs.267 The specific ET (HT) attenuation factor β varies for different systems and depends on the electron (hole) effective mass in shell materials and the core/shell band offset (potential barrier). This suggests exciting opportunities for independently controlling ET and HT (or BET) rates from QDs and leads to the idea of “wavefunction engineering” for controlling charge separation and recombination process in heterostructures.168 For an in-depth discussion about wave function engineering and its application, reader can refer to the review paper in ref (168).

Figure 10.