Abstract

Background:

Poly(L-lactic acid) (PLLA) is a biodegradable polymer (BP) that replaces conventional petroleum-based polymers. The hydrophobicity of biodegradable PLLA periodontal barrier membrane in wet state can be solved by alloying it with natural polymers. Alloying PLLA with gelatin imparts wet mechanical properties, hydrophilicity, shrinkage, degradability and biocompatibility to the polymeric matrix.

Methods:

To investigate membrane performance in the wet state, PLLA/gelatin membranes were synthesized by varying the gelatin concentration from 0 to 80 wt%. The membrane was prepared by electrospinning.

Results:

At the macroscopic scale, PLLA containing gelatin can tune the wet mechanical properties, hydrophilicity, water uptake capacity (WUC), degradability and biocompatibility of PLLA/gelatin membranes. As the gelatin content increased from 0 to 80 wt%, the dry tensile strength of the membranes increased from 6.4 to 38.9 MPa and the dry strain at break decreased from 1.7 to 0.19. PLLA/gelatin membranes with a gelatin content exceeding 40% showed excellent biocompatibility and hydrophilicity. However, dimensional change (37.5% after 7 days of soaking), poor tensile stress in wet state (3.48 MPa) and rapid degradation rate (73.7%) were observed. The highest WUC, hydrophilicity, porosity, suitable mechanical properties and biocompatibility were observed for the PLLA/40% gelatin membrane.

Conclusion:

PLLA/gelatin membranes with gelatin content less than 40% are suitable as barrier membranes for absorbable periodontal tissue regeneration due to their tunable wet mechanical properties, degradability, biocompatibility and lack of dimensional changes.

Keywords: Poly(L-lactic acid), Gelatin, Electrospinning, Absorbable periodontal tissue Regeneration, Degradation, Shrinkage

Introduction

Conventional plastic production based on fossil fuel resources contributes to oil consumption, CO2 emissions and nondegradable plastic waste [1–3]. Air and earth pollution caused by conventional petroleum-based polymers can be dramatically improved using biodegradable polymers (BPs) [2–5]. A BP is defined as a substance that can be decomposed into carbon dioxide and water through the action of microorganisms under normal environmental conditions [2, 3]. BPs have emerged as potential candidates for environmental and biomedical applications due to their excellent mechanical properties and biodegradability [2, 3]. Nanofibrous scaffolds of aliphatic biodegradable polyesters have many merits, including morphological similarity to the extracellular matrix of native tissues and excellent cell adhesion. However, the hydrophobicity nature of these materials limits their widespread use [5–16]. Polymer blending [5, 14, 15], an alternative to plasma technology [9–12], double layer process [13] and hydrothermal treatments [14], is an effective method for modifying BPs by tuning their hydrophilic and mechanical properties to achieve desirable physical properties. Electrospun membranes had the potential to be surface modified by pulsed DC magnetron sputtering of biodegradable metal and calcium phosphate targets [9–13]. Although the formation of as-sputtered metal and metal oxide thin films can improve wettability and cell adhesion, surface modification by sputtering occurs near the surface and hydrophobic fibers located deep in the membrane remain intact [9–12]. Also, plasma etching can control wettability by changing the topography of membrane. Unlike grooved surfaces, rough surfaces promote proliferation and directional migration of osteoblasts into the defect site [12]. A bi-layered poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA)/calcium phosphate membrane was constructed with the outer layer being PLGA. External PLGA can disrupt the migration of epithelial cells. And the calcium phosphate in the inner layer absorbs blood clots and enhances osteoblast activity [13]. The wettability and mechanical properties of BP were enhanced through the hydrothermal process (polylactic acid (PLA) membrane coated with polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)) [14]. However, studies on in vivo biocompatibility and biodegradability are needed.

Poly(L-lactic acid) (PLLA) is widely used as a scaffold material in tissue engineering because of its mechanical properties and biodegradability [15–20]. The hydrophobicity of PLLA can be improved by alloying it with natural polymers [15, 16]. The specific ratio of PLLA to gelatin in a hybrid membrane results in tunable mechanical properties and biological functions [15–20]. Fluorine-based alcohols (1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP, C3H2F6O)) have strong functionality; therefore, they can undergo a fast reaction and improve the mechanical properties of the hybrid membranes [15, 16, 21]. PLLA/gelatin blends with specific PLLA to gelatin ratios were electrospun using HFIP as the solvent. When using PLLA/gelatin barriers for periodontal regeneration, successful repair of periodontal tissue generally requires maintenance of a specific barrier function, typically requiring 4–6 weeks for periodontal tissue regeneration and 16–24 weeks for bone growth [6]. The optimum composition of PLLA for periodontal tissue regeneration was determined to be 3 wt% [15, 16]. To meet the regeneration period for use as a periodontal barrier, the degradation behavior of PLLA/gelatin membranes containing 0–80% gelatin by weight was evaluated. To demonstrate the feasibility of using PLLA/gelatin membranes as barriers for periodontal tissue regeneration, the effects of gelatin concentration on the degradation behavior of PLLA/gelatin membranes were investigated. The mechanical properties, water uptake capacity (WUC), degradability, water contact angle (WCA), shrinkage and biocompatibility of the membranes were studied experimentally.

Materials and methods

Materials

PLLA_1 (Resomer® L210S, inherent viscosity 3.3–4.3 dL/g, St. Louis, MO, USA), PLLA_2 (average Mn 10,000, St. Louis, MO, USA) and gelatin from porcine skin (gel strength 300, Type A, St. Louis, MO, USA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, USA. HFIP (Daejung Chemicals & Metals Co., Ltd., Cheongju, Korea) was used as the PLLA/gelatin membrane solvent. PLLA was prepared by mixing 80 wt% PLLA_1 and 20 wt% PLLA_2 to increase its degradability [5]. All chemicals were used as received.

Manufacturing of PLLA/gelatin membranes

The custom-made electrospinning apparatus is composed of a syringe pump (KDS-200, Stoelting Co., Wood Dale, IL, USA), BD luer-lock syringe, metal needle, drum collector and high-voltage power supply (ES30P-5W, Gamma High Voltage Research Inc., Ormond Beach, FL, USA) [15, 16]. Detailed electrospinning procedures are described elsewhere [16]. 3 wt% PLLA was dissolved in HFIP using a magnetic stirrer for 6 h at room temperature (RT). Gelatin (0–80 wt%) was then added to the PLLA solution. The electrospun membranes were dried at RT for 48 h and then placed in a vacuum oven at 37 °C for 48 h to remove any remaining solvents [14–16].

The viscosity of the solution was measured at RT using a viscometer (DV 1 M, Brookfield, Middleboro, MA, USA). Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, Spectrum Two, PerkinElmer, Beaconsfield, UK) was used to examine the chemical structure of the membranes [16, 22]. The microstructure of the membrane was studied using scanning electron microscopy (SEM, S-3000H, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) and optical stereomicroscopy (SV-55, Sometech, Seoul, Korea). Fiber diameters and histograms were then determined [15, 16, 22, 23]. The mechanical properties of the membranes were tested using an Instron 5564 instrument [16]. The specimens were prepared in the form of dumbbells according to ASTM D-638 (Type V). All experiments were performed at least five times. The WUC of a membrane was also measured [16, 24]. Liquid displacement techniques have been used to examine membrane porosity [16, 24].

Lyophilized samples were cut into 10 × 10 mm pieces, weighed and soaked in 0.01 M PBS containing 0.1 mg/mL of lysozyme (muramidase from hen egg white, Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) [25, 26]. The samples were then incubated to simulate the body’s environment. Samples were collected every 7 days and lyophilized. Experimental procedures for determining degradation rates have been reported elsewhere [16, 24]. WCA was measured to determine the hydrophilicity of the membranes. It was examined using a droplet analyzer (SmarDrop Standard, FEMTOFAB, Seongnam, Gyeonggi-do, Korea). Two microliters of distilled water were added to each sample. After 5 s, the static contact angle was measured and analyzed [9, 16]. The values in the text are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant [15, 16].

Cytotoxicity, cell proliferation and attachment

An extract test was performed on the PLLA/gelatin membranes to evaluate their cytotoxic potential according to the International Organization for Standardization (ISO 10993-5) [16]. Membranes were aseptically extracted with serum in single-strength Minimum Essential Medium. The membrane-to-extraction vehicle ratio was prepared according to ISO 10993-12. After incubation for 24 h, the test extracts were positioned on separate confluent monolayers of L-929 (NCTC Clone 929, ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). The detailed experimental procedures have been described elsewhere [15, 16, 22].

Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8, Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc., Japan) was used to examine cell proliferation. The nonradiative CCK-8 assay allows sensitive colorimetric assays for cell proliferation analysis [16, 22]. Water-soluble tetrazolium salt is reduced by cellular dehydrogenases to produce an orange-colored product (formazan), which is soluble in tissue culture medium. The amount of formazan dye produced by dehydrogenases in the cells is directly proportional to the number of living cells. A 96-well plate containing 100 μL of cell suspension (5 × 103 cells/well) was incubated for 24 h at a temperature of 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Test extracts (10 μL) were added to the plate and maintained for an appropriate length of time (6, 12, 24, 48 h) in a CO2 incubator. After adding 10 μL of CCK-8 solution to each well of the plate, the plate was incubated for 2 h. The absorbance of the colored solution was measured at a wavelength of 450 nm using an iMark microplate absorbance spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) [15, 16].

L-929 cells (1×104 cells/well) seeded on the PLLA/gelatin membranes were incubated at 37 °C for 48 h with 5% CO2. The cells attached to the membrane surfaces were fixed at RT for 20 min with a 4% formaldehyde solution in PBS and then for 5 min in methanol at – 20 °C [9]. To evaluate cell attachment, the cell morphology on the polymer membranes was measured using SEM.

Results

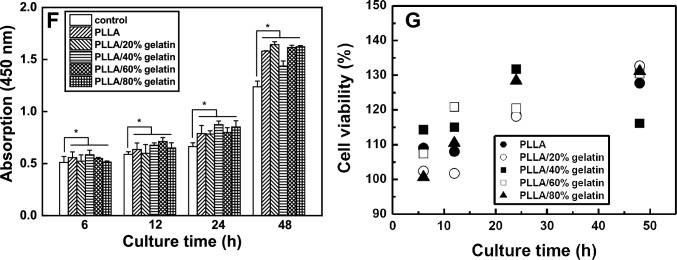

The absorbable commercial membrane (NeoDura), manufactured by Medprin Biotech GmbH (Frankfurt, Germany), is widely used as a synthetic graft membrane [15]. The strength, strain at break and WUC of NeoDura composed of PLLA and collagen, were reported to be 3.7 ± 0.5 MPa, 0.55, and 455%, respectively [15]. As the gelatin concentration increased from 0 to 40 wt%, the tensile strength, WUC and porosity of PLLA increased from 6.4 ± 0.8 MPa to 8.9 ± 1.7 MPa, from 162 to 1440% and from 86.7% to 98.2%, respectively, as summarized in Table 1. For the PLLA membrane containing 60% gelatin, the highest tensile stress was observed at 39.3 ± 3.7 MPa, but as shown in Figs. 1 and 2, the strain at break, WUC and porosity decreased to 0.28, 858% and 86.0%, respectively. Macroscopic modification of PLLA using natural polymers can increase WUC and porosity while reducing failure strain until PLLA acts as a matrix in the hybrid polymer [5, 15–18, 27, 28]. As depicted in Fig. 2, the WUC and porosity of the PLLA/gelatin membrane with a gelatin content exceeding 40 wt% decreased dramatically. Gelatin is produced by the partial hydrolysis of collagen and consists of a liquid phase dispersed in a solid network [29, 30]. Gelatin hydrogels can retain large amounts of water within their networks without dissolving. Gelatin maintains the overall structural integrity but prevents the water phase from solidifying into a rigid solid, allowing the formation of a fine gelatinous network [29, 30]. However, crosslinked gelatin rapidly loses its mechanical properties as the temperature increases above the sol-gel transition temperature (~35oC), which is equivalent to the oral state. The matrix of the PLLA/gelatin membrane with a gelatin content exceeding 50wt% was changed from PLLA to gelatin. The gelatin hydrogel matrix containing PLLA was responsible for low mechanical properties and enhanced degradability.

Table 1.

Experimental results for PLLA and different PLLA/gelatin membranes

| Sample | Fiber diameter (nm) | Viscosity (cP) | Porosity (%) | WUC (%) | Stress (MPa) | Strain at break | Cell viability (%) | Degradation rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLLA | 488 ± 49 | 443 ± 6.9 | 93.8 ± 0.8 | 482 ± 96 | 6.4 ± 0.8 | 1.70 ± 0.1 | 137 ± 0.12 | 0.8 |

| PLLA/20%gelatin | 289 ± 32 | 273 ± 1.2 | 95.6 ± 0.5 | 1154 ± 256 | 6.7 ± 1.3 | 0.44 ± 0.07 | 143 ± 0.12 | 8.6 |

| PLLA/40%gelatin | 275 ± 44 | 164 ± 1.2 | 98.2 ± 0.9 | 1440 ± 98 | 8.9 ± 1.7 | 0.23 ± 0.02 | 133 ± 0.14 | 31.5 |

| PLLA/60%gelatin | 396 ± 82 | 96 ± 0.7 | 86.0 ± 0.7 | 858 ± 242 | 39.3 ± 3.7 | 0.28 ± 0.06 | 150 ± 0.08 | 51.8 |

| PLLA/80%gelatin | N/A | 59 ± 1.7 | 84.5 ± 6.4 | 687 ± 34 | 38.9 ± 3.2 | 0.19 ± 0.04 | 154 ± 0.02 | 73.7 |

Fig. 1.

A Tensile stress and B strain at break of PLLA/gelatin membranes

Fig. 2.

Changes in porosity and water uptake capacity of PLLA/gelatin membranes depending on gelatin concentration

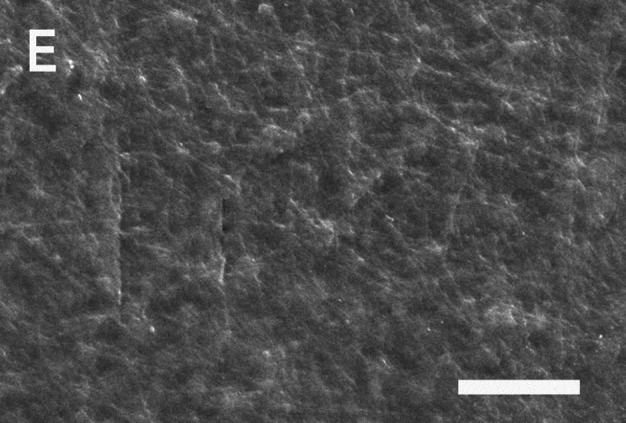

The dependence of the morphology of the PLLA/gelatin membranes on gelatin concentration was examined. Figure 3 shows the typical SEM morphology of a uniform and continuous fiber without beads. As the gelatin concentration increased from 0 to 80 wt%, the viscosity decreased gradually from 443 to 59 cP. Initially, when the gelatin content increased from 0 to 40%, the fiber diameter decreased from 489 to 275 nm and porosity increased from 93.8 to 98.2%. Gelatin molecules with high dielectric constants were more likely to be charged during electrospinning [16, 18]. Therefore, electrospun jets with higher gelatin content are likely to have more excess charges, resulting in thinner fibers and higher porosity. As the gelatin content increased from 40 to 80%, the morphology changed dramatically from a fibrous to a gelatinous structure [29, 30]. A gelatinous matrix that retains water molecules within the network without dissolving them results in a semi-rigid material. Gelatin-immobilized matrices containing PLLA fibers were observed (Fig. 3E). The decrease in WUC, porosity and strain at break of PLLA/gelatin membranes containing a higher gelatin content (above 40%) was due to microstructural changes in the PLLA/gelatin membranes. A dramatic decrease in the WUC (687%), porosity (84.5%) and strain at break (0.19) was observed at an 80 wt% gelatin concentration because of the contribution of gelatin to the PLLA/gelatin membrane [29, 30]. The incorporation of gelatin dramatically reduced the strain to less than 1.0. The membrane should be fixed to the tissue to prevent bleeding and close the wound after implant surgery [31, 32]. Reduced ductility of the PLLA/gelatin barrier membrane between the gingiva and alveolar bone may increase the risk of failure during suturing, laser tissue welding, or nanoparticle-based wound adhesives [6, 7, 31, 32]. However, it can be used to transport and deliver drugs to target locations in the body. Drug molecules can be loaded into the pores of the gelatin matrix and then released in response to environmental stimuli such as temperature and pH, enabling rapid healing [12, 29, 30].

Fig. 3.

SEM images and histograms of PLLA/gelatin membranes as a function of gelatin concentration: A 0 wt%, B 20 wt%, C 40 wt%, D 60 wt% and E 80 wt%, respectively. Note that the scale bar represents 25 μm

The FTIR spectra of the gelatin, PLLA and various PLLA/gelatin membranes are displayed in Fig. 4. In the PLLA structure, peaks corresponding to the carbonyl (–C=O, 1750 cm−1), ether (1085 cm−1, 1180 cm−1) and methyl groups (1385 cm−1, 2943 cm−1, 2995 cm−1) were visible. The bands at 1080 and 1185 cm−1 and at 1453 and 1382 cm−1 correspond to the C–O stretching and C–H bending vibrations, respectively [14, 16, 18]. When gelatin was mixed with PLLA, amide peaks (1650 cm−1 and 1543 cm−1) representing gelatin were observed. The intensity of the amide peak representing gelatin increased, and the intensity of the ester peak at 1750 cm−1 decreased rapidly as the gelatin content increased. No new absorption peaks produced by the chemical reaction between PLLA and gelatin were visible, implying that PLLA and gelatin molecular chains interacted only via van der Waals forces [15, 16, 18].

Fig. 4.

FT-IR spectra of gelatin, PLLA and different PLLA/gelatin membranes

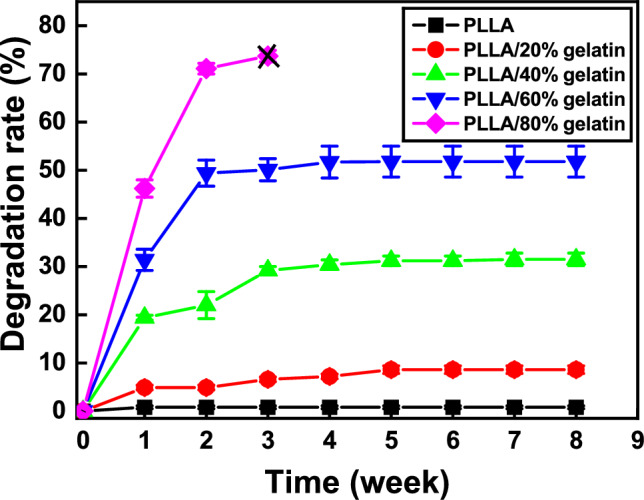

Tissue engineering allows the growth of cells on membranes implanted into organ defects [20, 33]. When implanted in vivo, PLLA/gelatin membranes may degrade over time through the hydrolysis of ester bonds [1–3]. The degradation of PLLA/gelatin was further enhanced by the localization of extracellular degradative enzymes on the PLLA surface. The ester bond cleavage of PLLA, the formation of lactic acid oligomers and monomers, and the fragmentation of PLLA enhance enzymatic degradation and cause the digestion of PLA oligomers and monomers by bacterial cells [3]. For the PLLA/gelatin blends, the degradation rate may be accelerated in PLLA with a higher gelatin content owing to increased hydrolysis, as displayed in Fig. 5. No appreciable degradation of PLLA (0.8%) was observed over time. The morphology of the semicrystalline PLLA/gelatin blend, which contained more PLLA than gelatin, did not change because of homogeneous degradation [2, 3, 16]. The degradation rate of PLLA/gelatin increased rapidly until week 1, then decreased and reached a plateau at week 5. The PLLA/80% gelatin membranes broke into pieces after 3 weeks of degradation, whereas the remaining membranes remained intact. When 20 wt% gelatin was added to PLLA, a 4.9% degradation of the PLLA/gelatin blend occurred immediately after incubation for 1 week at 37 °C. The degradation rate plateaued at 8.6% after 5 weeks. The degradation rate increased significantly from 8.6% to 73.7% (after 3 weeks of soaking) as the gelatin content increased from 20 to 80%. However, the degradation rate of PLLA/80% gelatin membrane could not be measured after 3 weeks owing to membrane breakage [29, 30]. Membranes containing more gelatin than PLLA underwent dimensional changes, membrane fragment breakage and severe degradability.

Fig. 5.

Enzymatic degradation rate of PLLA/gelatin membranes as a function of gelatin concentration. Note that X indicates that the membrane broke into fragments

SEM images of the membrane surface (Fig. 6) show intermittent aggregation of PLLA after 8 weeks of degradation. BP was generally decomposed through two stages. First, water molecules hydrolyze long polymer chains into shorter fragments through ester bond cleavage. Later, the fragments were metabolized to produce carbon dioxide and water [16, 17]. As the gelatin content increased to 20%, the aggregates tended to stick together. As the gelatin content further increased, the membranes began to break down into craters and decompose, and the size of the craters increased, further aggravating the decomposition. As the gelatin content was increased from 0 to 40%, the cross-sectional images of the membranes indicated that the morphology changed from a dense nanofibrous structure to the cleavage and fragmentation of fibers owing to ester bond cleavage [2, 3]. Severe degradation of gelatinous membranes was observed when the gelatin content exceeded 40%. Decomposition was accelerated owing to the structural change from a fibrous structure to a gelatin-immobilized matrix structure, as shown in Fig. 6. The PLLA/80% gelatin membrane (Fig. 6E) was completely fragmented, and cross-sectional images could not be obtained. The hydrophilic gelatin content is believed to be the most influential variable in the degradation of PLLA/gelatin blends.

Fig. 6.

SEM images of the surfaces and cross-sections of PLLA/gelatin membranes after 8 weeks of degradation in the medium at gelatin concentrations: of A 0%, B 20%, C 40%, D 60% and E 80%. The scale bar represents 50 μm and the PLLA/80% gelatin membrane was examined after 3 weeks of degradation

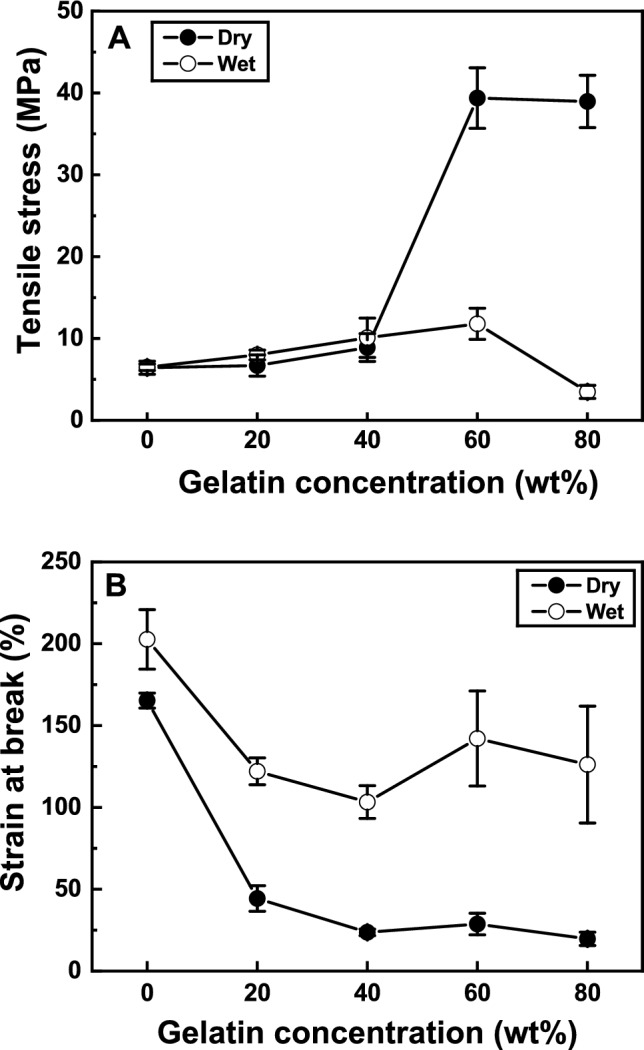

SEM images of L-929 cells on the surface of PLLA and PLLA/gelatin membranes after 48 h of culture and photographs of the cell morphology of EZ-cytox cells after exposure to the membrane suspensions for 48 h are shown in Fig. 7 [34–36]. The L-929 fibroblast cells adhered and spread extensively, forming extensions on the membrane surface regardless of the gelatin content. The cytotoxicity of PLLA/gelatin membranes with gelatin concentrations ranging from 0 to 80% determines their toxicity [15, 16, 34–36]. The L-929 cell viabilities of PLLA/gelatin membranes containing 0%, 20%, 40%, 60% and 80% gelatin were 137%, 143%, 133%, 150% and 154%, respectively, compared with that of the negative control. PLLA membranes with a gelatin content greater than 50% exhibited cell viability greater than 150%. None of the membranes exhibited cytotoxicity under the conditions used in this study. The proliferation results of L-929 cells on the PLLA/gelatin membranes are displayed in Fig. 7F, which shows that the L-929 cells adhered well to the membranes regardless of the gelatin ratio of the PLLA/gelatin membrane. They proliferated continuously over time and exhibits excellent cell viability. After adding 10 μL of CCk-8 solution to each well of the plate, the absorbance of the colored solution was measured at a wavelength of 450 nm using iMark microplate absorbance spectrophotometer. Cell viability was quaintified using the equation, cell viability (%) = (At/Ac) x 100, where At and Ac represent the absorbance values of the tested extract and negative control (untreated cells), respectively [37]. Cell viability on PLLA/gelatin membranes always exceeded 100% regardless of gelatin content, as depicted in Fig. 7G. For membranes with gelatin content less than 40wt%, it was in the range of 101 to 132%.

Fig. 7.

SEM images of L-929 cell attachment (scale bar: 20 μm) and optical photographs of cell morphologies (scale bar: 100 μm) of A PLLA, B PLLA/20% gelatin, C PLLA/40% gelatin, D PLLA/60% gelatin and E PLLA/80% gelatin membranes. F Proliferation of L-929 cells on the negative control and G cell viability of PLLA/gelatin membranes over culture time. Results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (*p < 0.05)

Discussion

To improve the biodegradability of the hydrophobic PLLA membrane, hydrophilic gelatin natural polymer was added. This alloying process is expected to enhance the biodegradability, mechanical properties and biocompatibility of PLLA/gelatin membrane under a certain amount of gelatin. Higher WUC, porosity and lower strain to failure were observed for PLLA/gelatin membranes until PLLA served as the matrix for the hybrid polymer, as depicted in Figs. 1 and 2. Lower WUC, porosity and higher strain at break were found with gelatin acting as the matrix in the hybrid polymer. However, due to the hydrophilicity nature of gelatin, severe decomposition, shrinkage and poor stress were inevitable due to the morphological change from fibrous to hydrophilic gelatinous structure. In periodontal therapy, low ductility and high shrinkage of the barrier membrane can be serious problems during dental surgery.

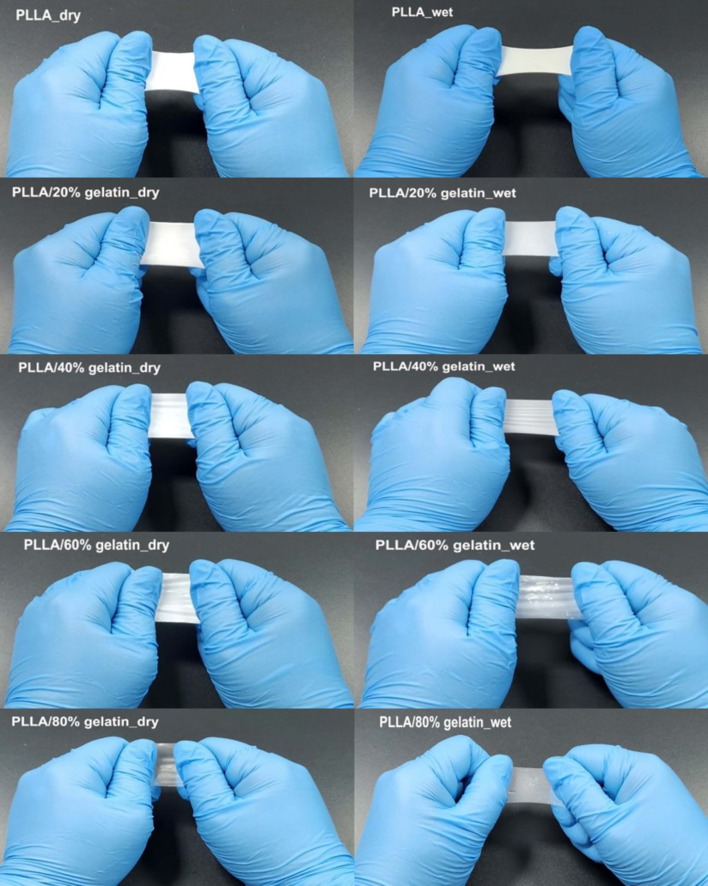

To verify the feasibility of the PLLA/gelatin membrane, two experiments were performed: finger stretching and shrinkage tests. Commercially available periodontal barriers and sutures were soaked in appropriate saline solution before use. The disadvantage of this step is that the robustness of the barrier often deteriorates in wet conditions, resulting in loss of space between the barrier and tooth, which can be detrimental to clinical outcomes [38, 39]. Because the periodontal regeneration barrier is used within the oral cavity, wet conditions are more important than dry conditions [15, 16]. If the membranes were not wetted, the saline solution was absorbed by pressing it with a gloved finger for 3 min. The water-soaked PLLA membrane could not be wetted without finger pressure because of its hydrophobicity, whereas the gelatin-blended PLLA membranes were easily wetted. The addition of gelatin to PLLA dramatically reduced the WCA from 126° to 0°, resulting in excellent hydrophilicity. Optical photographs of finger stretching of PLLA/gelatin membranes under dry and wet conditions are shown in Fig. 8. The extension properties of the PLLA/gelatin membrane in the dry state decreased significantly from 1.65 and 0.19 with increasing gelatin concentration from 0 to 80%, as verified in Fig. 1B. Because the PLLA membrane is hydrophobic, it was force-wetted with water using a gloved finger. Figure 8 shows that a slightly greater extension (from 2.02 to 1.26) was observed for the wet membranes than for the dry membranes.

Fig. 8.

Optical photographs of finger stretching of PLLA/gelatin membranes under dry and wet conditions

When 20 wt% gelatin was added to PLLA, the wet strain of the PLLA/gelatin membrane increased from 0.44 to 1.22. Gelatin can hold large amounts of water within its network without disrupting its structural integrity, as long as PLLA serves as the matrix [29, 30]. In addition, fragmented PLLA oligomers and monomers tend to crystallize in the PLLA matrix. This is because the polymer chains have sufficient mobility to rearrange into more stable configurations [1–3, 16, 38, 39]. However, the tensile stress exhibited the opposite phenomenon when the PLLA/gelatin membranes were wetted (Fig. 1A). During hydrolysis, water molecules are preferentially introduced into the amorphous regions, which increases polymer crystallinity because chain scission reactions are favored within the amorphous regions [2, 3]. Although the increased fracture strain of PLLA/gelatin membranes can be ascribed to the structural integrity of the gelatin and the PLLA crystallinity, the onset of ester cleavage due to hydrolysis is likely due to stress reduction [1–3, 38, 39]. However, the wet stress of the PLLA/gelatin membranes was similar when the gelatin content increased up to 40 wt%. This is because the disintegration time is insufficient due to the short immersion time [16]. However, when the gelatin content increased to 80wt%, the wet stress decreased rapidly from 38.87 MPa to 3.48 MPa owing to the microstructural change from a fibrous to a hydrophilic gelatinous structure, as shown in Fig. 3. Fragmentation, which is associated with a decrease in molecular weight due to cleavage of ester bonds, results in loss of mechanical properties [40, 41].

Samples were soaked in PBS and shrinkage tests were performed for 7 days at 37 °C. No shrinkage was observed in the PLLA/gelatin membranes with gelatin contents of up to 40 wt%, as shown in Fig. 9. However, the PLLA/gelatin membranes with gelatin contents exceeding 50% shrank. The linear shrinkages of the PLLA/50% gelatin, PLLA/60% gelatin and PLLA/80% gelatin membranes increased from 10 to 12.5%, 15 to 17.5% and 30 to 37.5%, respectively, as the soaking time increased from 1 to 7 days. Hydrolytically unstable PLLA/gelatin membranes, which have a higher gelatin content than PLLA, can be used as controlled drug delivery devices that experience severe shrinkage but continuously release their content in a controlled manner over some time [40–42]. During the degradation, a rapid decrease in molecular weight occurs as susceptible ester bonds in the polymer chains are cleaved. Smaller polymer fragments were generated and then dissolved in the aqueous medium, resulting in mass loss [40]. Microencapsulation can be achieved by coating the antigenic material with BP, which can protect and control antigen delivery. Peptides, native and synthetic proteins and nucleic acids can be delivered through BP-prepared microspheres [41, 42].

Fig. 9.

Shrinkage results of PLLA and PLLA/gelatin membranes soaked in PBS for up to 7 days

Immersion of the PLLA/40% gelatin membrane in water increased the stress and strain from 8.9 ± 1.7 MPa to 10.1 ± 2.4 MPa and from 0.23 to 1.0, respectively. Excellent hydrophilicity, WUC, tunable degradation rate, mechanical properties, cell attachment, cell viability and proliferation were achieved by blending PLLA with gelatin. These experimental results suggest that tunable PLLA/gelatin hybrid membranes with a gelatin content less than 40% are suitable for periodontal tissue regeneration due to the absence of shrinkage. The synergistic combination of structural integrity and enhanced hydrophilicity may be effective for periodontal barrier biomaterials requiring rapid regeneration. Additionally, highly biodegradable PLLA/gelatin hybrid polymers can be used as drug-delivery microspheres. However, for comprehensive clinical trials, additional studies are necessary to examine PLLA/gelatin barriers in vivo. Preclinical study results, including skin sensitization test, acute systematic toxicity, subchronic toxicity, genotoxicity, intradermal reactivity and transplant test, will be presented later.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Technology Development Program (Project No. S3301367) funded by the Ministry of SMEs and Startups (MSS, Republic of Korea). We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.co.kr) for English language editing.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Yunyoung Jang, Juwoong Jang, Bae-Yeon Kim, Yo-Seung Song and Deuk Yong Lee declare they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical statement

There are no animal experiments carried out for this article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yo-Seung Song, Email: yssong@kau.ac.kr.

Deuk Yong Lee, Email: duke1208@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Castro-Aguirre E, Auras R, Selke S, Rubino M, Marsh T. Insights on the aerobic biodegradation of polymers by analysis of evolved carbon dioxide in simulated composting conditions. Polym Degrad Stab. 2017;137:251–271. doi: 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2017.01.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Husarova L, Pekarova S, Stloukal P, Kucharzcyk P, Verney V, Commereuc S, et al. Identification of important abiotic and biotic factors in the biodegradation of poly(L-lactic acid) Intl J Biol Macromol. 2014;71:155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zaaba NF, Jaafar M. A review on degradation mechanisms of polylactic acid: hydrolytic, photodegradative, microbial, and enzymatic degradation. Polym Eng Sci. 2020;60:2061–2075. doi: 10.1002/pen.25511. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spasova M, Stoilova O, Manolova N, Rashkov I. Preparation of PLLA/PEG nanofibers by electrospinning and potential applications. J Bioact Comp Polym. 2007;22:62–76. doi: 10.1177/0883911506073570. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sitompul JP, Insyani R, Prasetyo D, Prajitno H, Lee HW. Improvement of properties of poly(L-lactic acid) through solution blending of biodegradable polymers. J Eng Technol Sci. 2016;48:430–441. doi: 10.5614/j.eng.technol.sci.2016.48.4.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Solomon S, Sufaru I, Teslaru S, Ghiciuc CM, Stafie CS. Finding the perfect membrane: current knowledge on barrier membranes in regenerative procedures: a descriptive review. Appl Sci. 2022;12:1042. doi: 10.3390/app12031042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sculean A, Nikolidakis D, Schwarz F. Regeneration of periodontal tissues: combinations of barrier membranes and grafting materials–biological foundation and preclinical evidence. J Clin Periodon. 2008;36:106–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin O, Averous L. Poly(lactic acid): plasticization and properties of biodegradable multiphase systems. Polymer. 2001;42:6209–6219. doi: 10.1016/S0032-3861(01)00086-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Badaraev AD, Sidelev DV, Kozelskaya AI, Bolbasov EN, Tran T, Nashchekin AV, et al. Surface modification of electrospun bioresorbable and biostable scaffolds by pulsed DC magnetron sputtering of titanium for gingival tissue regeneration. Polymers (Basel) 2022;14:4922. doi: 10.3390/polym14224922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sidelev, DV, Bleykher GA, Bestetti M, Krivobokov VP, Vicenzo, A, Fraz S, et al. A comparative study on the properties of chromium coatings deposited by magnetron sputtering with hot and cooled target. Vacuum. 2017;143;479.

- 11.Badaraev AD, Sidelev DV, Yurjev YN, Bukal VR, Tverdokhlebov SI. Modes development of PLGA scaffolds modification by magnetron co-sputtering of Cu and Ti targets. J Phys Conf Ser. 2021;1799;012001.

- 12.Sun X, Xu C, Wu G, Ye Q, Wang C. Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid): Applications and future prospects for periodontal tissue regeneration. Polymers (Basel). 2017;9;189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Reis ECC, Borges APB, Araujo MVF, Mendes VC, Guan L, Davies JE. Periodontal regeneration using a bilayered PLGA/calcium phosphate construct. Biomaterials. 2011;32;9244. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Abdal-hay A, Hussein KH, Casettari L, Khalil KA, Hamdy AS. Fabrication of novel high performance ductile poly(lactic acid) nanofiber scaffold coated with poly(vinyl alcohol) for tissue engineering applications. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2016;60:143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2015.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho Y, Jeong D, Lee DY. Comparative study on absorbable periodontal tissue regeneration barrier membrane. J Cryst Growth Cryst Technol. 2023;33:71–77. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cho Y, Jeong H, Kim B, Jang J, Song Y, Lee DY. Electrospun poly(L-lactic acid)/gelatin hybrid polymer as a barrier to periodontal tissue regeneration. Polymers. 2023;15:3844. doi: 10.3390/polym15183844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Annunziata M, Nastri L, Cecoro G, Guida L. The use of poly-D,L-lactic acid (PDLLA) devices for bone augmentation techniques: a systematic review. Molecules. 201;22;2214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Yan S, Xiaoqiang L, Shuiping L, Hongsheng W, Chuanglong H. Fabrication and properties of PLLA-gelatin nanofibers by electrospinning. J Appl Polym Sci. 2010;117:542–547. doi: 10.1002/app.30973. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shen R, Xu W, Xue Y, Chen L, Ye H, Zhong E, et al. The use of chitosan/PLA nanofibers by emulsion electrospinning for periodontal tissue engineering. Artif Cell Nanomed Biotechnol. 2018;46:419–430. doi: 10.1080/21691401.2018.1458233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu H, Oh HH, Kawazoe N, Yamgishi K, Chen G. PLLA-collagen and PLLA-gelatin hybrid scaffolds with funnel-like porous structure for skin tissue engineering. Sci Technol Adv Mater. 2012;13:064210. doi: 10.1088/1468-6996/13/6/064210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Casasola R, Thomas NL, Trybala A, Georgiadou S. Electrospun poly lactic acid (PLA) fibres: effect of different solvent systems on fibre morphology and diameter. Polymer. 2014;55:4728–4737. doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2014.06.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeong H, Rho J, Shin J, Lee DY, Hwang T, Kim KJ. Mechanical properties and cytotoxicity of PLA/PCL films. Biomed Eng Lett. 2018;8:267–272. doi: 10.1007/s13534-018-0065-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghasemi-Mobarakeh L, Prabhakaran MP, Morshed M, Nasr-Exfahani M, Ramakrishna S. Electrospun poly(ε-caprloactone)/gelatin nanofibrous scaffolds for nerve tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2008;29:4532–4539. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salehi M, Niyakan M, Ehterami A, Haghi-Daredeh S, Nazarnezhad S, Abbaszadeh-Goudarzi G, et al. Porous electrospun poly(ε-caprloactone)/gelatin nanofibrous mat containing cinnamon for wound healing application, in vitro and in vivo study. Biomed Eng Lett. 2020;10:149–161. doi: 10.1007/s13534-019-00138-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song Y, Kim B, Yang D, Lee DY. Poly(ε-caprolactone)/gelatin nanofibrous scaffolds for wound dressing. Appl Nanosci. 2022;12:3261–3270. doi: 10.1007/s13204-021-02265-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jeong H, Lee DY, Yang D, Song Y. Mechanical and cell-adhesive properties of gelatin/polyvinyl alcohol hydrogels and their application in wound dressing. Macromol Res. 2022;30:223–229. doi: 10.1007/s13233-022-0027-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yusof MR, Shamsudin R, Zakaria S, Hamid MAA, Yalcinkaya F, Abdullah Y, et al. Fabrication and characterization of carboxymethyl starch/poly(L-lactide) acid/β-tricalcium phosphate composite nanofibers via electrospinning. Polymers (Basel) 2019;11:1468. doi: 10.3390/polym11091468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alberti C, Damps N, Meibner RRR, Hofmann M, Rijono D, Enthaler S. Selective degradation of end-of-life poly(lactide) via alkali-metal-halide catalysis. Adv Sustain Syst. 2019;4:1900081. doi: 10.1002/adsu.201900081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mikhailov OV. Gelatin as it is: history and modernity. Intl J Mol Sci. 2023;24:3583. doi: 10.3390/ijms24043583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alipal J, Puad NSASM, Lee TC, Nayan NHM, Sahari N, Basri H, et al. A review of gelatin: properties, sources, process, applications, and commercialization. Mater Today Proc. 2021;42:240–250. doi: 10.1016/j.matpr.2020.12.922. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He W, Fureh J, Shao J, Gai M, Hu N, He Q. Guidable GNR-Fe3O4-PEM@SiO2 composite particles containing near infrared active nanocalorifiers for laser assisted tissue welding. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp. 2016;511:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2016.09.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meddahi-Pelle A, Legrand A, Marcellan A, Louedec L, Letourneur D, Leibler L. Organ repair, hemostasis, and in vivo bonding of medical devices by aqueous solutions of nanoparticles. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2014;53:6369–6373. doi: 10.1002/anie.201401043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wojak-Cwik IM, Hintze V, Schnabelrauch M, Moeller S, Dobrzynski P, Pamula E, et al. Poly(L-lactide-co-glycolide) scaffolds coated with collagen and glycosaminoglycans: impact on proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2013;101:3109–3122. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li W, Zhou J, Xu Y. Study of the in vitro cytotoxicity testing of medical devices (review) Med Rep. 2015;3:617–620. doi: 10.3892/br.2015.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khalili AA, Ahmad MR. A review of cell adhesion studies for biomedical and biological applications. Intl J Mol Sci. 2015;16:18149–18184. doi: 10.3390/ijms160818149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shalumon KT, Deepthi S, Anupama MS, Nair SV, Jayakumar R, Chennazhi KP. Fabrication of poly(L-lactic acid)/gelatin composite tubular scaffolds for vascular tissue engineering. Intl J Biol Macromol. 2015;72:1048–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.09.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tamayo L, Santana P, Forero JC, Leal M, Gonzalez N, Diaz M, et al. Coaxial fibers of poly(styreneco- maleic anhydride)@poly(vinyl alcohol) for wound dressing applications: Dual and sustained delivery of bioactive agents promoting fibroblast proliferation with reduced cell adherence. Intl J Pharm. 2022;611;121292. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Xu L, Crawford K, Gorman CB. Effect of temperature and pH on the degradation of poly(lactic acid) brushes. Macromolecules. 2011;44:4777–4782. doi: 10.1021/ma2000948. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zulkifli FH, Hussain FSJ, Rasad AMSB, Yusoff MM. In vitro degradation study of novel HEC/PVA/collagen nanofibrous scaffold for skin tissue engineering applications. Polym Degrad Stab. 2014;110:473–481. doi: 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2014.10.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hausberger AG, DeLuca PP. Characterization of biodegradable poly(D, L-lactide-co-glycolide) polymers and microspheres. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 1995;13:747–760. doi: 10.1016/0731-7085(95)01276-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lima KM, Rodrigues Junior JM. Poly-DL-lactide-co-glycolide microspheres as a controlled release antigen delivery system. Braz J Med biol Res. 1999;32:171–180. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X1999000200005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Capan Y, Woo BH, Gebrekidan S, Ahmed S, DeLuca PP. Preparation and characterization of poly(D,L-lactide-co-glycolide) microspheres for controlled release of poly(L-lysine) complexed plasmid DNA. Pharm Res. 1999;16;509. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.