Abstract

An in-silico approach was implemented to develop a multi-epitope subunit vaccine construct against the recent outbreak of the Monkeypox virus. The contribution of 10 different antigenic proteins based on their antigenicity led to the selection of 10 HTL, 9 CTL, and 6 BCL epitopes. The construct was further investigated for its allergenicity, antigenicity, and physio-chemical properties using servers such as AllerTOP and Allergen FP, VaxiJen and ANTIGENPro, and ProtParam respectively. The secondary structure of the vaccine was predicted using the SOPMA server followed by I-TASSER for the 3D structure. After refinement and validation of structural stability of the modelled vaccine, a molecular docking assay was implemented to study the interaction of the known TLR4 receptor with that of the constructed vaccine using the ClusPro server. The docked vaccine and TLR4 receptor were studied using the molecular dynamics (MD) simulation to validate the stability of the complex. After codon optimization the cDNA was constructed and in-silico cloning of the vaccine construct was carried out. The vaccine was also subjected to computational immune assay which predicted a powerful immune response against the Monkeypox virus validating that the developed multi-epitope vaccine construct can be a potent vaccine candidate.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40203-024-00220-5.

Keywords: Monkeypox, In-silico, Multi-epitope, Molecular dynamics, Immune assay

Introduction

The recent global emergence of monkeypox infection has gathered significant attention because of its zoonotic ability and capacity for interspecies transmission, thereby impacting the human race globally. Monkeypox virus, an Orthopoxvirus of the Poxviridae family caused an alarming rate of infection among humans in the year 2022. The total number of cases reported so far is more than 50,000 and 16 deaths have been reported to the United Nations organization. Monkeypox was first detected among captive monkeys transported to Denmark from Africa. A larger pool of viruses is reserved in rodents such as squirrels and rats hunted down for food (Petersen et al. 2019). This disease has achieved global health importance after its outbreak in the USA in the year 2003 associated with infected pet prairie dogs. The dogs housed with rodents from Ghana, Africa became the primary source of infection and led to the infection in humans when they came in contact with the infected prairie dog. A cluster of infected individuals was reported in the summer of 2003 in the US Midwest and a larger outbreak of monkeypox was reported in Nigeria in 2017 (Kaler et al. 2022). After the first report of Monkeypox in May 2022, 92 laboratory-confirmed cases and 28 suspected cases were reported in non-endemic countries including Canada, Belgium, Australia, the Netherlands, Spain, Germany, France, Portugal, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America (Lai et al. 2022).

The variola virus (VARV) of the orthopox genus was historically renowned as a formidable pathogen responsible for significant mortality and was eradicated using live vaccinia virus (VACV) (Babkin et al. 2022). Monkeypox also belongs to this notorious group and is characterized by the formation of maculopapular lesions of about 2–5 mm in diameter and spread in a centrifugal manner on a human body and rarely in a centripetal fashion. The lesions progress through various stage of formation namely, papular, vesicular, and pustular which finally falls off the body leaving a dyspigmented scar. The disease is also known to affect the lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy) and is experienced with fever, chill, and body aches (Petersen et al. 2019) (Lai et al. 2022) (Shchelkunova and Shchelkunov 2022).

The mode of transmission of this disease from animals to humans is still elusive. Transmission through aerosols was demonstrated to prove the nosocomial outbreak in the Central African Republic. Indirect or direct contact with either dead or live animals is also considered a conduit of infection among humans. Exposure to bodily fluids such as saliva, respiratory exhalant, or exudates of lesions/scars is also a mode of transmission of the virus. The fecal matter of infected animals also harbors the virus and is responsible for infecting populations of an underdeveloped nation where people still sleep on the ground. The human-to-human transmission occurs through close contact, sharing contaminated objects, direct contact with lesions, and respiratory droplets. The degree of transmissibility of this disease i.e., the average number of people who can contract a contagious illness from a diseased individual, R0 value lies between 1.0 and 2.4 suggesting that an infected individual can transmit this disease to one or two more individuals, and in such a case it is advisable to follow quarantine protocols and maintain social distancing. The transmissibility also depends on factors like population, contact patterns, and public health care intervention. Individuals with immunodeficiency especially those infected with HIV are at a higher risk of attaining the infection if not taken care of.

The diagnosis of this disease is done either by nucleic acid amplification technique for the estimation of DNA of the orthopoxvirus or specifically monkeypox virus. The quantification can also be assessed using real-time PCR assay and also by serological testing of IgG which becomes detectable post 8 days of the onset of symptoms. Despite its advantage in learning about the immunity of a recovered individual or in detecting past infection, antibody testing is not a reliable method to detect infection in the initial onset of symptoms because the body takes time to produce IgG antibodies against the infection, which might give a false negative result even when the individual has contracted the disease. However, it is advisable not to use antibody testing alone for the diagnosis of monkeypox (Lai et al. 2022).

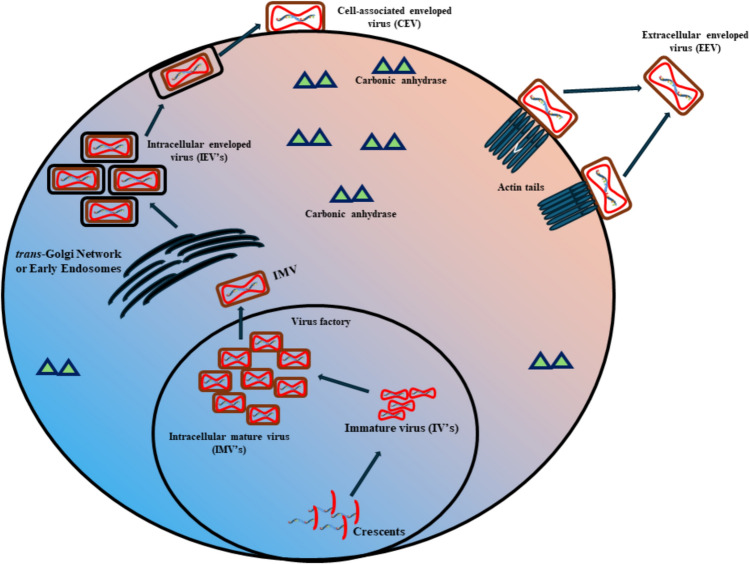

The transmission of monkeypox can be controlled by following certain precautionary measures such as isolating infected individuals from the healthy ones and following quarantine procedures to control the spread. The human-to-human transmission can be reduced by avoiding close contact, physical touch, and sharing of things. The health co-workers taking care of patients should self-isolate them and cover any visible lesions to avoid transmission. A medical mask and usage of gloves are recommended while in close contact with an infected person sanitization and following hygienic practices can also bring down the risk of transmission. Besides following sanitary and quarantine practices antiviral drugs used for the treatment of smallpox such as cidofovir, brincidofovir, and tecovirimat, and is used for the treatment of immunocompromised individuals infected with monkeypox. The usage of cidofovir a potential viral DNA polymerase inhibitor is a broad-spectrum antiviral agent and has proven to show effect against monkeypox virus. The administration of cidofovir is only considered in severe cases of viral infection because of its toxic effects affecting blood and kidney and showed significant drawback because of its poor solubility and need for intravenous administration. Therefore, to overcome this challenge a lipid conjugate of the same, brincidofovir was synthesised in tablet form and showed potent inhibitory activity against the virus. Tecovirimat, another oral intracellular viral release inhibitor also showed specific efficacy on several orthopox viruses including monkeypox. In addition to these, a vaccinia immune globulin approved by the US FDA can also be recruited for the treatment of severe cases. People vaccinated against smallpox may have some protection against monkeypox. The usage of US FDA-approved IMAVUNE is used for adults above 18 years at high risk of smallpox or monkeypox. The use of ACAM2000 licensed by the FDA, a smallpox vaccine is recommended for usage in Europe (Lai et al. 2022). The non-availability of vaccines against monkeypox brings in a lot of opportunities for drug companies to design and synthesize vaccines specific to monkeypox. Vaccines provide protection not just to the virus but also prevent the spread of vector-borne illnesses. The development of a vaccine can be done using the conventional method which would involve the usage of protein, peptides, or inactivated/attenuated pathogens in combination with adjuvants. Unlike the conventional method, the immunoinformatic approach to developing a vaccine is considered to be cost-effective and takes lesser time frame than the traditional approach (Pandey et al. 2018; Pandya and Kumar 2023). According to the analysis, the monkeypox virus translates several proteins many of which are involved in its pathogenicity, replication, and structural integrity (Fig. 1) (Naveed et al. 2016).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of proteins associated with the monkeypox multiplication and pathogenicity

The preliminary goal of our study is to consider such proteins, adapt the immunoinformatic approach of vaccine development, and analyze and use the results obtained in silico to develop a multiepitope vaccine for the treatment of monkeypox. The antigenicity and allergenicity of the vaccine developed via this method are taken into consideration for further studies. This approach also involves minimal risk to the individual because no live pathogen is used for the development of the vaccine. A 3D model of the vaccine is obtained by employing the fusion of B-cells and T-cells epitopes to build a new subunit of vaccine to activate and build innate, humoral, and cell-mediated immunity against the infection. The obtained multiepitope vaccine is also docked with the TLR4 receptor by MD simulation to verify the complex structure of the 3D-modelled vaccine obtained (Pandya and Kumar 2023). This study can employ advanced PCR and sequencing techniques to uncover novel insights into Monkeypox virulent proteins, providing valuable information for vaccine design by identifying specific genetic markers crucial for targeted immunization strategies (Naveed et al. 2014a, b).

Materials and methods

The Neural networks that mimic the mechanism of nervous system are encompassed by natural computing models and these models embrace the solution of complex problems of classification, clustering, signal processing, data visualization, data mining, and information fusion (Masulli and Mitra 2009). The designing of the multi-epitope vaccine requires information about proteins that show antigenicity and the prediction of epitopes (B-cells and T-cells) when arranged linearly can help design rapid vaccination against pathogens. To obtain all this information about proteins and epitopes in-silico tools based on deep learning or neural networks such as NetMHC, NetCTL, VaxiJen, etc. were utilized and subjected for the development of multi-epitope vaccine (Joshi et al. 2021).

Retrieval of antigenic proteins from the Monkeypox virus genome

The entire protein sequences of the Monkeypox virus were retrieved from the NCBI protein database in FASTA format (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/). These proteins were subjected to a web-based tool VaxiJen for analyzing their antigenicity (Doytchinova and Flower 2007). The server classifies antigens based on the auto cross-covariance transformation of protein sequences into uniform vectors of principle amino acid properties. The antigenic scores were obtained using the default parameters, and proteins showing an antigenic score > 0.4 were carried forward for further investigation.

Prediction of MHC-I specific cytotoxic T-lymphocytes epitopes

The prediction of CTL epitopes was analyzed using the NetCTL-1.2 server. The epitopes predicted by NetCTL-1.2 is a collective prediction of TAP transporter efficiency associated with antigen processing, proteasomal C-terminal cleavage, and MHC class-I binding resulting in the prediction of epitopes that are top-scoring and highly sensitive(Doytchinova and Flower 2007). The selected proteins were subjected to an analysis against all the 14 available alleles (HLA-A0l:01, HLA- A02:0l, HLA-A02:03, HLA-A02:06, HLA-A03:0l, HLA-All:0l, HLA-A24:02, HLA- A31:0l, HLA-A33:0l, HLA-B07:02, HLA-B35:0l, HLA-B51:01, HLA-B54:01, HLA-B58:01) using default parameters and the epitopes showing the highest binding score and probable non-allergen were selected for the construction of a vaccine.

Prediction of MHC-II specific helper T-lymphocyte epitopes

The NetMHCII Pan Server exploit tailored machine learning strategies trained on both binding affinity and mass spectrometry-eluted ligands (Reynisson et al. 2021). The NetMHCII Pan server was utilised to predict the 15-mer HTL epitopes showing higher binding affinity against the twenty MHCII alleles DRBl_0l0l, DRB1_0301, DRB1_0401, DRB1_0405, DRB1_0701, DRB1_0802, DRB1_0901, DRB1_1101, DRB1_1201, DRB1_1302, DRB1_1501, HLA-DPA10103-DPB10101, HLA-DPA10201- DPB10201, HLA-DPA10301-DPB10301, HLA-DQA10401-DQB10401, HLA-DQA10501-DQB10501, HLA-DQA10102-DQB10202, HLA-DQA10402-DQB10402. The epitope showing highest binding score and probable non-allergen was chosen for vaccine construction.

B-cell epitope prediction

To produce antibodies against a pathogen, the B-cells need to be activated by the specific antigens/epitopes. Therefore, the selected antigenic proteome of the Monkeypox virus was examined for the promiscuous linear B-cell epitopes by using the BCPRED server(El-Manzalawy et al. 2008). The BCPRED server takes the FASTA sequence as input and generates 20mer epitopes with the default specificity of 75% towards the B-cell receptors. The epitope with the highest score was selected for further multi-epitope vaccine construction.

Population coverage of the vaccine construct

The world population coverage of the vaccine construct was determined on the basis of the frequency of occurrence for the respective HLA alleles. The population coverage tool of IEDB (http://tools.iedb.org/population/) that uses the allelfrequencies.net database was utilized to check the population coverage of the HLAs used in the analysis.

Designing of multi-epitope subunit vaccine sequence

The Immunoinformatic approach is taken to predict BCL, CTL & HTL epitopes which are antigenic, non-toxic & non-allergenic and were put to use for vaccine construction. To create a multivalent vaccination design for MPXV, the epitopes were combined with various linkers and adjuvants. Antigenic nature is required in vaccines for the elicitation of elongated immune responses in the body. Linkers are required to make protein more stable as it helps in protein folding and in getting flexible conformation (Nezafat et al. 2014). The role of adjuvants in vaccines is to boost immunogenicity and stimulate both innate and Adaptive. Two adjuvants were used, the first adjuvant was an agonist for TLR-4 Heparin-binding hemagglutinin (hbhA) which is a peptide of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and another one is TpD, the derivative of tetanus and diphtheria toxoid which elicit a humoral immune response on interaction with MHC class II alleles.

Evaluation of allergenicity, antigenicity, and physiochemical properties of multi-epitope vaccine construct

We use three servers to analyze the allergenicity of the designed vaccine AllerTOP v.2.0 (https://www.ddg-pharmfac.net/AllerTOP/), Allergen FP v.1.0 (https://www.ddg-pharmfac.net/AllergenFP/) and AlgPred (https://webs.iiitd.edu.in/raghava/algpred/submission.html). AllerTOP and Allergen FP use the data of known 2427 allergens and non-allergen of different species based on the K-nearest algorithm to predict allergenicity and AlgPred online server use a combination of tools (such as SVM, ARPs Blast, and MAST) to predict the allergenicity. For the prediction of antigenicity, we used two servers, the Vaxijen v.2.0 server, with a threshold value of 04 another server was ANTIGENpro which can be accessed through (https://scratch.proteomics.ics.uci.edu/). The Epaxy ProtParam server (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/), is used to estimate the various physiochemical properties of designed vaccines such as Molecular weight, Isoelectric point (pI), Instability index, aliphatic index, in-vivo and in-vitro half-life and Grand average hydrophobicity value (GRAVY). The toxicity of the designed vaccine was analyzed through the ToxinPred server (http://crdd.osdd.net/raghava/toxinpred/). The solubility of the protein sequence was also checked using the SOLpro server which is based on SVM based technique to predict with an average of 75% accuracy(Gasteiger et al. 2003).

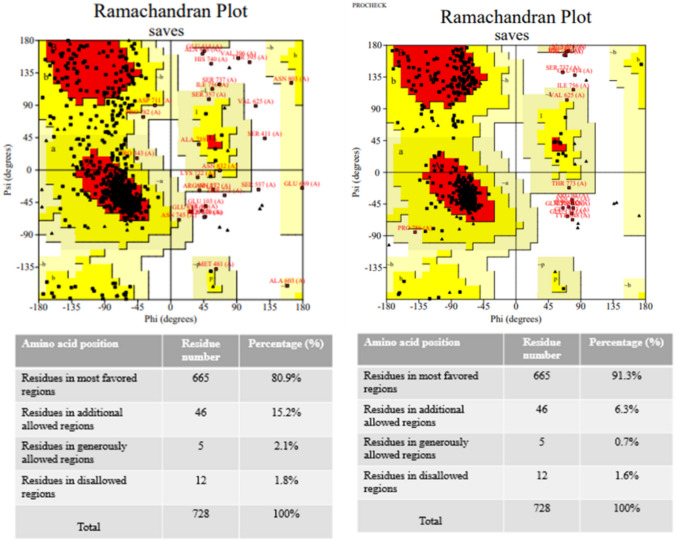

Prediction of secondary and tertiary structure of the vaccine construct and refinement

The SOPMA server tool was used in the prediction of the secondary structure of the (https://npsa-prabi.ibcp.fr/cgi-bin/npsa_automat.pl?page=/NPSA/npsa_sopma.html) vaccine construct. SOPMA stands for (Self Optimized Prediction Method with Alignment) and it uses a method based on a homology model. The I-Tasser server (https://zhanggroup.org/I-TASSER/) was used to predict the tertiary structure of the multi-epitope vaccine construct. I-Tasser is based on confidence score (C-Score). A higher C-Score indicates that the developed model is more accurate. Top-5 models get selected based on C-Score, and the Ramachandran plot of these 5 models gets constructed for a further selection of a model having a higher percent residue in the favorable region. Further, the modeled 3-D structure was refined by using the Galaxy Refine server (https://galaxy.seoklab.org/cgi-bin/submit.cgi?type=REFINE). This server is based on the ab initio modeling method which corrects loop or terminal regions of the predicted 3-D model. ERRAT server was used for quality validation of the predicted tertiary structure. PROCHECK server (https://saves.mbi.ucla.edu/) further analyzed the result of the galaxy refine server by providing specific data on the stereochemistry of a protein structure and also by constructing the Ramachandran plot, which was further used for model validation(Laskowski et al. 1993).

Molecular dynamics simulation of the vaccine construct

We evaluated the stability of the vaccine construct by performing molecular dynamics simulations utilizing the AMBER18 software suite (Case et al. 2018). The ff14SB (Maier et al. 2015) force field was implemented for protein parameters, while the LEaP module was utilized to add missing hydrogens and solvate the system. The solvation was done in a TIP3P (Price and Brooks 2004) octahedron periodic box with 10 Å distance from the protein’s surface. Additional and ions were introduced for charge neutralization and to make the system consistent with the standard physiological salt concentration of 150 mM. To put restraints on the bond lengths that included hydrogen atoms, the SHAKE (Kräutler et al. 2001) algorithm was used. For calculations of long-range electrostatic interactions, Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) (Darden et al. 1993) with a non-bonded cut-off of 10 Å was applied. Following system preparation, the subsequent minimization included two different stages. A restrained minimization of 5000 steepest descent and 5000 conjugant gradient steps was conducted with an applied force constraint of 2 . In the second minimization stage, 100 steepest descents followed by 900 conjugant gradient steps were performed without putting any restraint on the system. In multiple stages, the system’s temperature was increased from 0 to 300 K and subsequently retained using the Langevin thermostat (Pastor et al. 1988). Following a 1 ns NVT equilibrium, a 200 ns production run in the NPT ensemble was performed. The Berendsen Barostat (Berendsen et al. 1984) was used for the maintenance of a constant pressure of 1.0 bar. During the production simulation, a 2.0 fs time-step was used, and the Cartesian coordinates were saved at 10 ps intervals throughout the simulation. In total, 20,000 snapshots were collected during the production run. The root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) analysis was conducted using the Cpptraj (Roe and Cheatham 2013) module of AMBER18. A stable structure corresponding to the snapshot at 199.52 ns was considered for the subsequent studies. Structure validation was done using the SAVES 6.0 tool, and the Ramachandran plot was observed.

Molecular docking of multi-epitope vaccine construct with TLR4 and binding affinity prediction

The vaccine construct had a TLR4 adjuvant at its N terminal end. Protein–protein docking was carried in the ClusPro webserver (https://cluspro.bu.edu/home.php) to check the vaccine’s interaction with TLR4. We used the PDB ID 3FXI as the initial structure of TLR4 for our studies. During submission in the ClusPro server, TLR4 was considered as the receptor while the vaccine construct was considered as the ligand. The docking calculation in ClusPro is done with the following steps: a rigid body-based docking by FTT based global sampling on a grid using PIPER, followed by a RMSD based clustering to find highly populated clusters of low energy conformations, and further refinement by CHARMM minimization to remove steric clashes. A total of 30 docked complexes were generated in ClusPro based on the weighted score for the energy of the complex between the receptor and ligand. The ClusPro weighted scores are calculated as:

“where Erep and Eattr denote the repulsive and attractive contributions to the van der Waals interaction energy, and Eelec is an electrostatic energy term. EDARS is a pairwise structure-based potential constructed by the Decoys as the Reference State (DARS) approach, and it primarily represents desolvation contributions, i.e., the free energy change due to the removal of the water molecules from the interface.” (Kozakov et al. 2013).

Further, we predicted the binding affinity and dissociation constant of the docked complexes using the prodigy haddock webserver (https://wenmr.science.uu.nl/prodigy/). The binding affinity ΔG is calculated as:

where “Csxxx/yyy is the number of Interfacial Contacts found at the interface between Interactor1 and Interactor2 classified according to the polar/apolar/charged nature of the interacting residues (i.e. ICscharged/apolar is the number of ICs between charged and apolar residues). Two residues are defined in contact if any of their heavy atom is within a distance of 5.5 Å” (Xue et al. 2016).

Based on the predicted ΔG the dissociation constant is further calculated by the formula:

where R, T, and ΔG respectively denote the ideal gas constant (in kcal K-1 mol-1), temperature (in K) and the predicted free energy (in kcal/mol). The temperature for this experiment was set at 300 K.

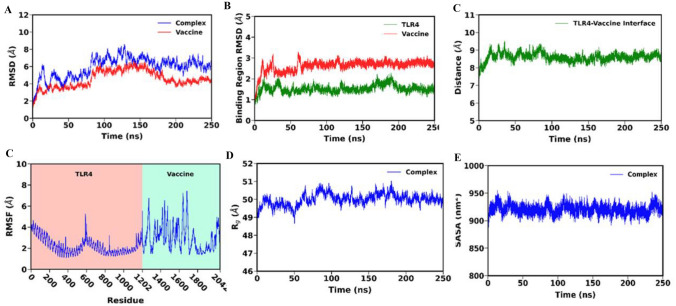

Molecular dynamics simulation of the multi-epitope vaccine construct in complex with TLR4

To assess the structural stability of the TLR4-bound vaccine construct, a 250 ns molecular dynamics simulation was carried out implementing the same protocol as previously described. The aim was to analyze the complex system’s overall stability throughout an extended period. The trajectory analyses including root-mean-suqare deviation (RMSD), root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF), solvent accessible surface area (SASA), radius of gyration (), hydrogen bond formation among others, were performed using the Cpptraj module of AMBER18. The most stable complex structure corresponding to the most probable RMSD value obtained from the production simulation was used as input for the PDBSum webserver (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/thornton-srv/databases/pdbsum/Generate.html), which identified the crucial residues responsible for a stable interaction between the two molecules.

Calculation of the binding free energy of TLR4-vaccine complex formation using MM-PBSA

To calculate the binding free energy and its components associated with the TLR4-vaccine complexation, the molecular mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann surface area (MM-PBSA)(Gohlke et al. 2003; Gohlke and Case 2004; Jonniya et al. 2022; Kollman et al. 2000; Miller et al. 2012; Sk and Kar 2022; Sk et al. 2021, 2022) method was exercised. The binding free energy () is calculated from the following equations -

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

Here the binding free energy () is calculated with contributions from the change in internal energy (), solvation free energy (), and the conformational entropy (). The and together constitute the enthalpy component () of the binding free energy. The can be further subdivided into the terms for covalent interactions including bond, angle, and dihedral (), electrostatic interaction (), and the van der Waals interaction term (). The solvation free energy comprises of the polar () and non-polar () components. Altogether, 2000 snapshots obtained from the last 60 ns trajectory at a frequency of 30 ps were used to calculate the . The calculation of the conformational entropy was avoided because of its high computational cost. The MM-PBSA per residue decomposition was exerted to identify the key residues contributing to stable binding in the complex.

cDNA construct, codon optimization, and in silico cloning of designed vaccine

The constructed vaccine cDNA was generated by importing their amino acid sequence in the Reverse translation tool of the EXPASY server. The main sequence of the vaccine constructs was evaluated for expression rate in a suitable expression vector (host Escherichia coli strain K12) by using the Java Codon Adaptation Tool (JCAT) (http://www.jcat.de/). The protein expression potency is checked through the JCAT result which consists of the Codon Adaptation Index (CAI) whose ideal value is 1.0 and GC content percent whose ideal range is between 30 and 70% of the total GC amount. The NEB Cutter V 2.0 (https://www.labtools.us/nebcutter-v2-0/) was used to search for restriction sites in the optimized cDNA and these sites were identified to be appended. For in-silico, cloning, the SnapGene software was used where the final gene construct was cloned in the pET28a ( +) expression vector.

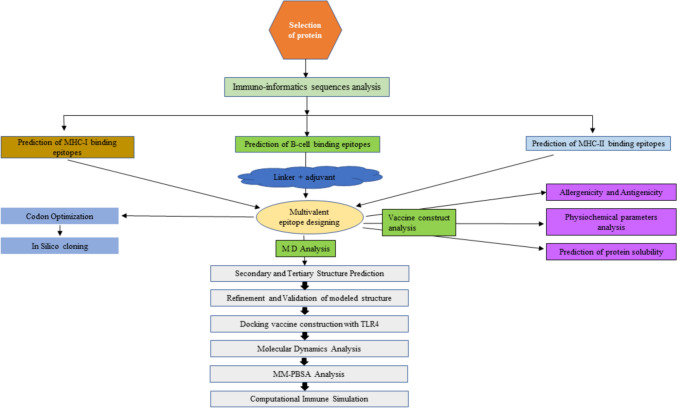

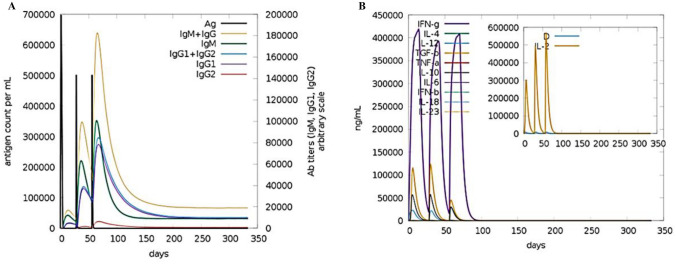

Immune simulation

We adopted the C-IMMSIM v10.1 tool to submit the developed vaccine for an assessment of its potential immunological effectiveness (C-IMMSIM Online server available at http://kraken.iac.rm.cnr.it/C-IMMSIM) (Rapin et al. 2010). The C-IMMSIM server uses position specific scoring matrix (PSSM) method to identify epitopes and stimulate the immunological response. The injection of the vaccine did not contain LPS, and the simulation's volume was set to 10 with a 12,345 random seed. There were 1000 simulation steps in all, with injection time steps of 1, 84, and 168. The other simulation parameters were left at their default values. The gap between each dose was 28 days as suggested in different literature (Sami et al. 2021) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of the procedure involved in vaccine construction

Results

Selection of proteins for the epitope designing and antigenicity analysis for the construction of the vaccine

The essential proteins were retrieved from the NCBI database in FASTA format and were analyzed for antigenicity using the web-based tool VaxiJen. An effective vaccine can only be constructed using proteins showing adequate immunogenic response. For viruses, the threshold was set to 0.4, proteins showing an antigenicity score > 0.4 were selected for the construction of a vaccine, and those reflecting antigenicity score < 0.4 were considered non-antigenic. The list of proteins showing antigenic scores more than the threshold is mentioned (Table 1).

Table 1.

List of proteins showing antigenic nature

| S. No. | Gene name | Protein name | NCBI protein ID | VaxiJen score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A35R | EEV glycoprotein (1) | NP_536572.1 | 0.5449 |

| 2 | A36R | EEV glycoprotein (2) | NP_536573.1 | 0.4438 |

| 3 | A38R | IEV transmembrane phosphoprotein | NP_536575.1 | 0.4038 |

| 4 | B6R | EEV type-I membrane glycoprotein | NP_536594.1 | 0.5773 |

| 5 | M1R | IMV membrane protein L1R | NP_536507.1 | 0.6112 |

| 6 | E8L | Carbonic anhydrase | NP_536532.1 | 0.5076 |

| 7 | A5L | A5L protein-like | NP_536542.1 | 0.4150 |

| 8 | H3L | IMV heparin binding surface protein | NP_536520.1 | 0.4481 |

| 9 | A21L | IMV membrane protein A2 | NP_536558.1 | 0.4196 |

| 10 | A32L | IMV membrane protein A30 | NP_536569.1 | 0.7336 |

Intracellular mature virus (IMV) particles are formed in the cytoplasmic virus factories from precursors called crescents and immature viruses. These IMV particles exit from the factory on microtubules and are wrapped by a double layer of intracellular membrane derived from early endosomes or trans-Golgi network and give rise to intracellular enveloped virus (IEV) particles. These then fuse to the plasma membrane and form a cell-associated enveloped virus (CEV) and when these detach from the cell surface, they give rise to an extracellular enveloped virus (EEV) Fig. 1.

The EEV glycoproteins affect plaque formation, EEV release, EEV infectivity, and virus virulence. IEV-specific proteins are responsible for IEV assembly and are also critical for actin tail formation. IMV membrane proteins play a regulatory role in enhancing viral growth. The IMV-associated proteins are also seen to be associated with nucleic acid packaging. The chronic anhydrase enzyme is responsible for maintaining the pH and osmolarity to allow conducive immediate environment for virus growth and multiplication.

Bioinformatics-based protein characterization

The proteins taken into consideration for the development of the multi-epitope vaccine were analyzed using the ProtParam tool. The analysis revealed that all the proteins have negative GRAVY values suggesting that these proteins are hydrophilic and are exposed to the surface implying their antigenic nature (Naveed et al. 2014a, b). The GRAVY value along with other physicochemical properties is mentioned in Table S1.

Prediction of MHC-1 specific CTL epitopes

CTLS are responsible for directly killing other cells and play a pivotal role in host defense against infections caused by viruses and pathogens that replicate intracellularly in the cytoplasm. NetCTL server was used to predict the CTL epitopes from the selected MPXV proteins. The method amalgamates the prediction of peptide MHC-I binding, Proteasomal C-terminal cleavage, and TAP transport efficiency. This server utilizes artificial neural networks that help in predicting a 9-mer showing a high propensity to proteasomal cleavage at its C-terminal ends and high affinity to MHC-I molecules. In the present study we used 14 different alleles of MHC-I namely: HLA-A0l:01, HLA- A02:0l, HLA-A02:03, HLA-A02:06, HLA-A03:0l, HLA-All:0l, HLA-A24:02, HLA- A31:0l, HLA-A33:0l, HLA-B07:02, HLA-B35:0l, HLA-B51:01, HLA-B54:01, HLA-B58:01. To obtain high epitope-HLA interaction specificity of more than 97%, the NetCTLs server's score was set as 0.4. The selected epitopes were further analyzed as one epitope per allele was selected having higher binding affinity and non-allergen (Table 2).

Table 2.

List of CTL epitopes

| Sl. No. | Cytotoxic T cell epitope | Start (aa) | End (aa) | Binding affinity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | VSDYVSELY | 78 | 86 | 0.996 |

| 2 | SLSAYIIRV | 184 | 192 | 0.965736 |

| 3 | TLKDLMSSV | 229 | 237 | 0.984114 |

| 4 | STLDYFTYL | 162 | 170 | 0.902861 |

| 5 | KIKSPNSSK | 53 | 61 | 0.971561 |

| 6 | RVLFSIFYK | 91 | 99 | 0.939823 |

| 7 | RYPGVMYTF | 267 | 275 | 0.997417 |

| 8 | KSQESYYQR | 42 | 50 | 0.966961 |

| 9 | ESYYQRQLR | 45 | 53 | 0.810342 |

| 10 | VPAMFTAAL | 87 | 95 | 0.935135 |

| 11 | QPVKEKYSF | 141 | 148 | 0.942536 |

| 12 | VPLITVTVV | 12 | 20 | 0.951341 |

| 13 | TPLQPPIVA | 187 | 195 | 0.976295 |

| 14 | LANKENVHW | 220 | 228 | 0.995694 |

Prediction of MHC-II specific helper T-lymphocyte (HTL) epitopes

HTL epitopes are crucial to both humoral and cellular immune response owing to their participation in Class II MHC activation. MHC-II specific HTL epitope (15-mers) were predicted by the IEDB tool. To cover the maximum population throughout the world, a set of 1 MHC-II molecules namely: DRBl_0l0l, DRB1_0301, DRB1_0401, DRB1_0405, DRB1_0701, DRB1_0802, DRB1_0901, DRB1_1101, DRB1_1201, DRB1_1302, DRB1_1501, HLA-DPA10103-DPB10101, HLA-DPA10201- DPB10201, HLA-DPA10301-DPB10301, HLA-DQA10401-DQB10401, HLA-DQA10501-DQB10501, HLA-DQA10102-DQB10202, HLA-DQA10402-DQB10402. To obtain high epitope-HLA interaction specificity of more than 97%, the NetCTLs server's score was set as 0.4. the selected epitopes were further analyzed as one epitope per allele was selected having higher binding affinity and non-allergen (Table 3).

Table 3.

List of HTL epitopes

| Sl. No. | T Helper cell epitope | Start (aa) | End (aa) | Binding affinity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DSGYHSLDPNAVCET | 49 | 63 | 0.972513 |

| 2 | AKYVEHDPRLVAEHR | 234 | 248 | 0.969403 |

| 3 | PNFWSRIGTVAAKRY | 19 | 33 | 0.850371 |

| 4 | LTNFKQLNSTTDSEA | 126 | 140 | 0.964813 |

| 5 | DIDVQYTSTLSVVHE | 21 | 35 | 0.912427 |

| 6 | YKDYWVSLKKTNDKW | 98 | 113 | 0.838941 |

| 7 | GEIIRAATTSPVREN | 235 | 249 | 0.945093 |

| 8 | LTAILFLMSQRYSRE | 287 | 301 | 0.751698 |

| 9 | FKIFNINKKSKKNSK | 42 | 56 | 0.805494 |

| 10 | RNELTIYQNTTVVIN | 134 | 148 | 0.970336 |

| 11 | WNKKKYSSYEEAKKH | 96 | 110 | 0.515812 |

| 12 | QEKRDVVIVNDDPDH | 44 | 58 | 0.7849 |

Prediction of B-cell epitopes

B-lymphocytes are a critical component of mammals' adaptive immune response responsible for humoral immunity. These are responsible for generating diversified but pathogen-specific antibodies resulting in antigen neutralization and viral load clearance. To include the epitopes having the propensity of activating the B-cells in the vaccine construct, the antigenic proteome was analyzed by using the ABCpred server. The best epitope from each antigenic protein with the highest score was used for the vaccine construction (Table 4).

Table 4.

List of B-cell epitopes

| Sl. No. | B cell epitope | Start (aa) | End (aa) | Antigenic score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | VIRSMMTPENDEEQTS | 23 | 39 | 0.92 |

| 2 | NGWIQYDKHCYLDTNI | 75 | 91 | 0.91 |

| 3 | TSICSKSNPFIAELNN | 216 | 232 | 0.94 |

| 4 | CDSGYHSLDPNAVCET | 86 | 102 | 0.94 |

| 5 | MVMEMRANEPRTEINL | 4 | 20 | 0.9 |

| 6 | GEIIRAATTSPVRENY | 263 | 279 | 0.92 |

| 7 | QPTIHITPQPVPTPTP | 98 | 114 | 0.91 |

| 8 | HEHINDQKFDDVKDNE | 67 | 83 | 0.97 |

| 9 | AISEKMRRERAAYVNY | 51 | 67 | 0.93 |

| 10 | MVMEMRANEPRTEINA | 4 | 20 | 0.91 |

Population coverage analysis

The population coverage worldwide was predicted using the IEDB server which is based on the interaction of selected epitopes with a number of HLA alleles as the expression of HLA alleles varies in different countries which are affected by the illness or diseases like the monkeypox virus. The worldwide population coverage of the MHC-I epitope was 91.22% while MHC-II coverage was 99.67%. Combinely, the MHC-I and MHC-II show 99.97% coverage of the worldwide population (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Predicted epitope population coverage analysis (A) MHC-I allele (B) MHC-II allele (C) combined MHC-I and MHC-II allele

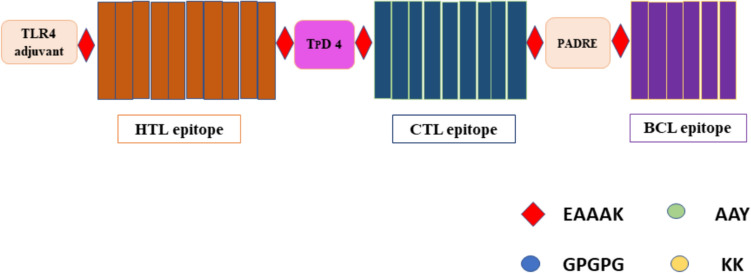

Vaccine construction

The construction of a multi-epitope vaccine was done by merging CTL (14), HTL (13), and BCL (9) epitopes with different adjuvants and linkers. MHC-I binding epitopes were joined by an AAY linker which helps in binding of antigen epitopes to the TAP transporter that leads to enhancement in epitope expression. KK linkers were used in joining the B-cell epitope. HTL epitopes get stimulated by GPGPG linkers to increase immunogenicity. To further increase the immunogenicity and antigenicity of the constructed vaccine two adjuvants were added, first one was added to the N-terminal side of constructed vaccine via EAAAK linker. The first adjuvant was similar to TLRs, as they upon encounter with antigen trigger the signaling cascade for an adaptive immune response within the host by increasing the production of Interferon-Beta. Heparin-binding Hemagglutinin (hbhA) has a similar response and activity as TLR4, when added to the constructed vaccine it increases the interferon beta-mediated immune response and reported in cancer vaccines (10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3487) (Jung et al. 2011). Another adjuvant TpD was added between CTL and HTL epitopes for enhancement of adaptive humoral immune response. The pan-HLA DR binding epitope (PADRE) can attach to a variety of mouse and human MHC-II alleles to produce CD4 + helper cell response which further increases vaccine immunogenicity. The CTL, HTL, and B cell epitopes, along with hbhA-TLR4, TpD adjuvant, and all linkers, form 736 amino acids long multi-epitope vaccine construct (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Linear representation of the construct multiepitope vaccine of MPXV

Multiepitope subunit vaccine construct allergenicity, immunogenicity, and physiochemical analysis

A constructed vaccine to be successful and safe must have the highest level of immunogenicity and which does not cause any allergies. Therefore, we verify the allergenicity on three different servers for authenticity. The AllerTOP and Allergen FP servers predicted the allergenicity of the constructed vaccine as non-allergen based on K-nearest algorithm. AlgPred also predicted it as a non-allergen based on a score = − 0.21 which signifies non-allergenicity. The immunogenicity of the vaccine was checked by Vaxijen and ANTIGENpro server. For the virus model, the Vaxijen server has a threshold value of 0.4, and any value above 0.4 is counted as antigenic, the predicted score was 0.4889 for a constructed vaccine. ANTIGENpro server gives the score on the basis of microarray data, where > 0.5 score is taken as good antigen and score of vaccine construct was 0.9322. The web-based tool ProtParam was implemented to derive the physiochemical properties of the constructed vaccine. The chemical formula of the constructed vaccine is C4093H6502N1134O1231S20 with a molecular weight of 91.9 kDa. The molecular weight of constructed vaccine is higher than the ideal mol. wt of vaccines. As reported higher mol. Wt higher the chances to come in contact with humoral antibodies to elicit the immune response. The isoelectric point of the construct is 9.4 reflecting that it is basic. The total number of amino acids in the construct is 840, which is soluble, and non-toxic. The stability of the vaccine is predicted by instability index where the score should be < 40. The instability index is 35.35 owing to the stability of the construct. The half-life of the vaccine construct is observed to be > 30 h in mammalian reticulocytes, > 20 h in yeast, and > 10 h in Escherichia coli. The predicted result signifies that if a host is subjected to a prolonged period, then it might strengthen the immune system. The GRAVY (grand average of hydropathy) scores signify the hydrophilic in nature if positive or hydrophobic if negative. The GRAVY score of the vaccine construct was – 0.548 which indicates the hydrophobic or non-polar nature of the vaccine. The SolPro data depicts that the construct is soluble with a probability of 93%. While toxicity analysis on the ToxinPred server indicates the non-toxic behavior of the construct (Table 5).

Table 5.

Physiochemical properties of the vaccine construct

| S. No. | Features | Assessment | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Antigenicity |

VaxiJen server 0.4889 AntigenPro server predicted probability of antigenicity: 0.930220 |

Probable antigen |

| 2 | Allergenicity |

Confirmed by -: AllerTop v.2.0 Tool AllergenFP v.1.0 Tool AlgPred v.2.0 Tool |

Probable non-allergen Non allergen Score = − 0.21 Probable non-allergen |

| 3 | Solubility | SolPro Tool: soluble with probability = 0.976850 | Soluble |

| 4 | Toxicity | ToxinPred 2.0 Tool | Non-toxin |

| 5 | Number of amino acids | 840 | Suitable |

| 6 | Molecular weight | 91.9 kDa | Average |

| 7 | Theoretical isoelectric point (pI) | 9.40 | Basic |

| 9 | Chemical formula | C4093H6502N1134O1231S20 | – |

| 11 | Estimated half-life |

30 h (mammalian reticulocytes, in vitro). > 20 h (yeast, in vivo) > 10 h (Escherichia coli, in vivo) |

– |

| 12 | Instability index | 35.35 | Stable |

| 13 | Aliphatic index | 72.63 | Thermostable |

| 14 | Grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY) | – 0.548 | Hydrophilic |

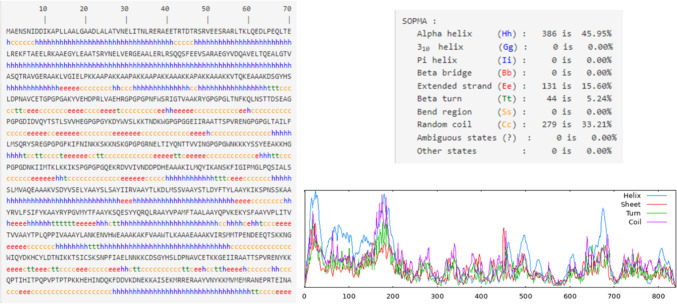

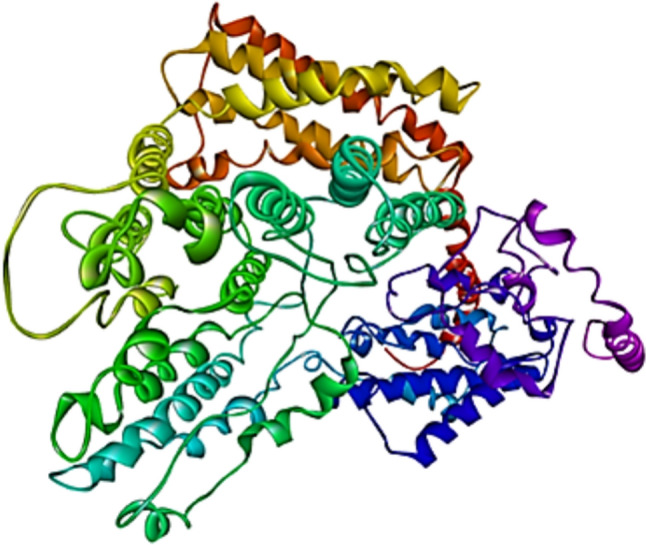

Structure prediction and validation of the multi-epitope subunit vaccine construct

The secondary structure prediction of the vaccine construct was analyzed by using the SOPMA server which helps in estimating the interaction of the vaccine construct with immunological receptors like TLRs. Its analysis depicts the result as ~ 46% alpha helix, ~ 16% beta-sheet, ~ 33% random coil and ~ 5% beta turn are present in the vaccine construct (Fig. 5). The structure was further validated using PsiPRED server (Figure S1). I-TASSER predicts the complete 3D structure of the given peptide sequence based on the multi-template-based threading method and provides several models with a rank of C-Score. C-Score ranges between − 5 and 2 and a higher C-Score of the model depicts the higher confidence of a model. The first model having a higher C-Score of − 1.32 among all the constructed models gets selected. And, further Validation of the selected model is done through Ramachandran plot analysis by using the PROCHECK server which deduced that 80.9% of residues of the predicted structure lay in the most favorable region and 15.2% of residues lie in the additionally allowed region. The modeled structure is further refined by using the GalaxyRefine server. It generates five structure models; Ramachandran plot was constructed of all the models and the model having higher percent residues in the allowed region is selected. The best model having 91.3% residues in the most favorable region along with 6.3% in the additionally allowed region and only 0.7% in the generously allowed region generated by GalaxyRefine with GDT-HA of 0.93, RMSD 0.468, MolProbity 2.018 and clash score of 12.4 was selected as the best vaccine construct and used for further molecular dynamics simulation analysis (Figs. 5, 6).

Fig. 5.

Secondary structure of the vaccine construct

Fig. 6.

Ramachandran plots of before and after refinement

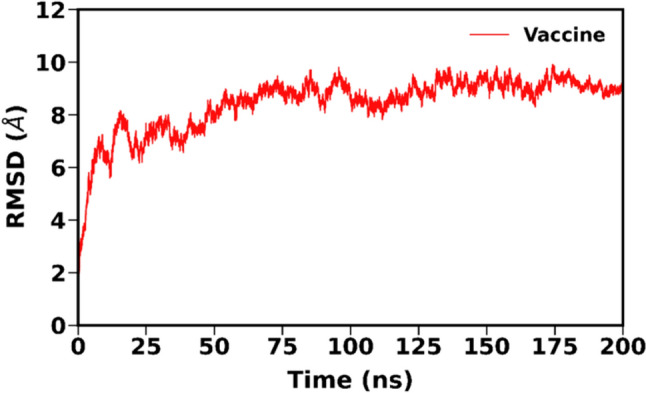

Structural stability of the modelled vaccine construct

The stability of the vaccine construct was evaluated by analyzing the trajectory obtained from the 200 ns molecular dynamics simulation. As observed in Fig. 7, the RMSD of the vaccine construct displayed an initial increase followed by minor fluctuations but eventually reached a stable state that persisted for the final ~ 100 ns of the simulation. This suggests that the vaccine construct maintained its structural stability throughout the latter half of the simulation course. A stable snapshot at ~ 199.52 ns was taken as our initial structure for the subsequent analyses (Fig. 8).

Fig. 7.

RMSD plot of vaccine construct MD simulation

Fig. 8.

Image of the final vaccine construct

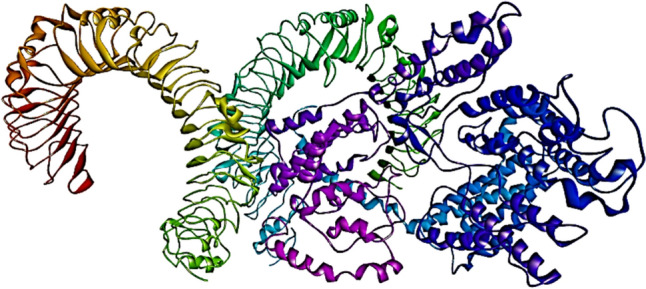

Multi-epitope subunit vaccine constructs interaction with TLR4

A total of 30 docked structures were generated in ClusPro. Based on the weighted score for the energy, the top 10 models were further analyzed in Prodigy to predict the binding affinity(ΔG) and the dissociation constant (Kd). The model with highest predicted binding affinity of − 18.9 kcal/mol and lowest ClusPro weighted score of − 1316.7 was used for further analysis (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Image of TLR4—vaccine docked complex

Stability of the TLR4-vaccine complex

Following a 250 ns long molecular dynamics simulation, the trajectory was examined to evaluate the stability of the TLR4-Vaccine complex. It is evident from Fig. 10A that, following a initial phase of higher fluctuation, the overall structure of the TLR4-Vaccine complex attained stability at ~ 100 ns, with the vaccine construct also exhibiting lesser structural deviation following that time point. The RMSD plot shows very minor fluctuations at the last 10 ns which suggests a good stable structure. Similar RMSD patterns were also observed during the development of multi-epitope subunit vaccines against the MERS virus (Joshi et al. 2023), dengue viral disease (Krishnan et al. 2021), Orthohantavirus (Joshi et al. 2022), and also against the ongoing infection of Monkeypox virus targeting the cell surface binding protein i.e., E8L (Shantier et al. 2022). Further analysis of the binding region RMSD confirmed the stability of TLR4 and the vaccine’s interacting regions Fig. 10B. The RMSF calculation performed accounting for only the atoms revealed larger fluctuations in the loop regions, observed more prominently in the vaccine construct Fig. 10D. Further, the RMSF analysis indicates that the interacting region of the TLR4 and the vaccine demonstrated relatively lower fluctuation suggesting the overall stability of the region, which also agrees with our earlier binding region stability analysis Fig. 10D. We further calculated the center of mass distance between the interacting region of TLR4 and the vaccine construct to examine their interaction stability. As observed in Fig. 10C, the low fluctuation of the distance indicates that the vaccine maintained a stable interaction with the receptor throughout the entire simulation course. Further the solvent accessible surface area (SASA) Fig. 10F and radius of gyration () Fig. 10E analysis demonstrated an overall stable time evolution. This low fluctuation in SASA further confirms the stablility of the TL4-Vaccine interaction, which is necessary for the relatively unchanging accessibility of complex structure’s interacting regions to the solvent. The complex also maintained a relatively stable compactness, as depicted in the analysis in Fig. 10E. The mean value of the various parameters calculated from the last 200 ns trajectory are listed in Table 6. These results collectively suggest that our developed multi-epitope vaccine construct has a high potential for a stable interaction with TLR4 leading to the trigger of a robust immune response against the monkeypox virus.

Fig. 10.

A RMSD plot of vaccine and docked complex B RMSD plot of binding region of TLR4-Vaccine construct, C distance plot of TLR4-vaccine binding interface, D RMSF plot of TLR4 and vaccine, E Rg plot of docked complex, and F SASA plot of docked complex

Table 6.

A list of parameters and their mean value calculated from the last 200 ns trajectory

| Parameter | Mean |

|---|---|

| Complex RMSD (Å) | 6.34 (0.0057) |

| TLR4 RMSD (Å) | 4.58 (0.0040) |

| Vaccine RMSD (Å) | 4.85 (0.0058) |

| TLR4 binding region RMSD (Å) | 1.54 (0.0012) |

| Vaccine binding region RMSD (Å) | 2.71 (0.0010) |

| SASA () | 919.75 (0.0564) |

| Radius of gyration (Å) | 50.09 (0.0019) |

The standard error of the mean is provided in parentheses

Binding free energy calculations using MM-PBSA

We used the molecular mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann surface area (MM-PBSA) to uncover the underlying energetics of the TLR4-Vacine interaction. As listed in Table 7, the binding free energy of the TLR4-Vaccine complex formation was computed to be − 241.84 kcal/mol. A previous study from our group demonstrated that a multi-epitope vaccine construct designed for the treatment of ebola virus infection exhibited a binding free energy of − 194.2 kcal/mol upon binding with TLR4. Our currently designed vaccine construct has a higher calculated binding affinity against TLR4, highlighting its potential to elicit a strong immune response against the monkeypox virus. From Table 7, it is clear that the intermolecular electrostatic ( = − 6171.46 kcal/mol) and van der Waals interactions ( = − 286.00 kcal/mol), as well as the non-polar component of the solvation free energy ( = − 31.59 kcal/mol) were the crucial drivers for the binding of TLR4 with the vaccine. Due to the high binding opposition of the polar solvation free energy ( = 6247.21 kcal/mol), the net polar component (+ = 75.75 kcal/mol) overall disfavoured the binding but was overcompensated by the prominent contribution from the van der Waals interactions.

Table 7.

Energetics components of the TLR4-Vaccine complex formation

| System | ΔEvdW | ΔEelec | ΔGpol | ΔGnp | ΔGbind |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TLR-vaccine complex | − 286.00 (0.24) | − 6171.46 (2.08) | 6247.21 (2.02) | − 31.59 (0.02) | − 241.84 (0.43) |

The values are in kcal/mol and the standard error of the mean are listed in parentheses

Further, the MM-PBSA per residue decomposition was utilized to identify the key residues that took part in the stabilization of the interaction between the two molecules. Residues with energy contribution ≤ − 2.0 kcal/mol are listed in Table 8. The most prominent contribution from the vaccine towards the binding was demonstrated by the residues Thr1783, Ser1939, Ile1721, Lys1820, Met1781, Leu1227, Tyr1720, Arg1723, Lys1935, Pro1804, Tyr1615, Lys1854, Tyr1782, Asn1206, among others (see Table 8).

Table 8.

Per-residue decomposition of binding free energy listing the residues with energy contribution − 2.0 kcal/mol

| Vaccine | Energy (kcal/mol) | TLR4 | Energy (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thr1783 | – 4.58 | Arg434 | – 6.98 |

| Ser1939 | – 4.52 | Gln458 | – 5.47 |

| Ile1721 | – 4.49 | Asn712 | – 5.13 |

| Lys1820 | – 4.30 | Lys534 | – 4.84 |

| Met1781 | – 4.23 | Phe983 | – 3.04 |

| Leu1227 | – 3.78 | Val605 | – 2.78 |

| Tyr1720 | – 3.77 | Pro688 | – 2.70 |

| Arg1723 | – 3.60 | Arg957 | – 2.65 |

| Lys1935 | – 3.47 | Pro487 | – 2.44 |

| Pro1804 | – 3.36 | Hid1104 | – 2.40 |

| Tyr1615 | – 3.30 | Leu618 | – 2.33 |

| Lys1854 | – 3.24 | Gln666 | – 2.19 |

| Tyr1782 | – 3.10 | Phe461 | – 2.10 |

| Asn1206 | – 3.06 | Glu413 | – 2.08 |

Intermolecular hydrogen bond formation between TLR4 and the vaccine construct

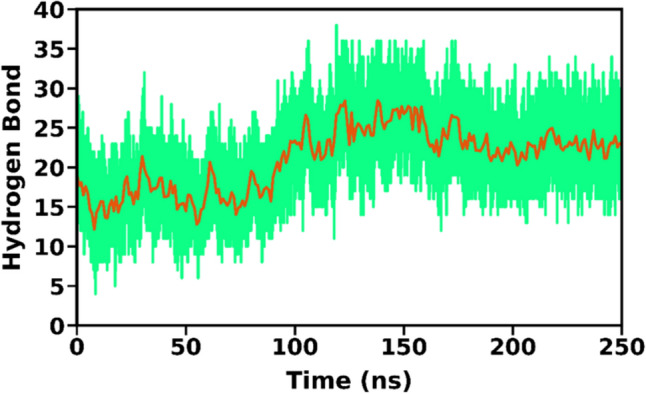

Hydrogen bonds are essential for the overall structural stability of a protein–protein complex. From the simulation trajectory, the time evolution of the number of hydrogen bonds formed between the vaccine and TLR4 was analyzed. With a cut-off of < 3.5 Å for the acceptor–donor distance and a 120∘ angle cut off; the H-bond occupancy was calculated for the entire simulation trajectory. The H-bond analysis showed that an average of around 15–25 H-bonds formed between the vaccine construct and TLR4 (Fig. 10). It was also observed that the no. of hydrogen bonds increased after around 100 ns and was stable for the rest of the simulations The pair of H-bond forming atoms with more than 20% occupancy and the corresponding parameters are listed in Table 9.

Table 9.

Hydrogen bond parameters for corresponding residues

| Acceptor | Donor | Dist. | Angle | Occupancy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asn1853@O | Gln458@NE2 | 2.84 | 160.91 | 70.94 |

| Ser1718@O | Gln666@NE2 | 2.85 | 160.44 | 69.82 |

| Met1781@O | Ser759@OG | 2.75 | 156.00 | 52.78 |

| Glu1855@OE2 | Arg434@NH2 | 2.82 | 153.15 | 41.99 |

| Glu1855@OE1 | Arg434@NH2 | 2.82 | 151.95 | 41.17 |

| Pro1804@O | Hid1104@ND1 | 2.84 | 159.21 | 40.92 |

| Glu1855@OE1 | Arg434@NH1 | 2.78 | 154.27 | 38.41 |

| Glu1855@OE2 | Glu459@N | 2.84 | 160.57 | 37.54 |

| Glu1855@OE1 | Glu459@N | 2.84 | 161.10 | 36.11 |

| Glu1855@OE2 | Arg434@NH1 | 2.79 | 154.89 | 31.93 |

| Glu1205@OE2 | Arg957@NH2 | 2.79 | 158.48 | 29.01 |

| Glu1205@OE1 | Arg957@NH2 | 2.79 | 158.76 | 25.54 |

| Glu1205@OE1 | Arg957@NH1 | 2.81 | 161.28 | 25.26 |

| Glu1205@OE2 | Arg957@NH1 | 2.81 | 160.99 | 23.90 |

| Gln1797@O | Gln410@NE2 | 2.86 | 156.02 | 21.95 |

| Glu1791@OE2 | Asn914@ND2 | 2.83 | 163.02 | 21.05 |

| Asp980@OD1 | Asn1206@ND2 | 2.80 | 160.03 | 62.84 |

| Leu485@O | Ala2042@N | 2.86 | 158.97 | 56.60 |

| Glu664@OE1 | Tyr1615@OH | 2.68 | 165.26 | 49.57 |

| Glu617@OE1 | Ser1939@OG | 2.67 | 166.19 | 42.16 |

| Asn712@O | Arg1723@NH1 | 2.80 | 155.32 | 35.57 |

| Gln458@OE1 | Asn1856@N | 2.88 | 157.24 | 35.24 |

| Asn712@O | Arg1723@NE | 2.85 | 153.04 | 33.28 |

| Glu459@OE1 | Ser1920@OG | 2.72 | 160.30 | 30.79 |

| Glu410@OE1 | Gln1797@NE2 | 2.85 | 162.12 | 28.28 |

| Glu664@OE2 | Tyr1615@OH | 2.69 | 164.89 | 27.38 |

| Glu459@OE2 | Ser1920@OG | 2.73 | 159.15 | 26.20 |

| Glu617@OE1 | Ser1939@N | 2.87 | 159.01 | 24.82 |

| Glu841@OE2 | Thr1783@OG1 | 2.70 | 164.00 | 23.98 |

| Glu459@OE2 | Val1857@N | 2.85 | 152.68 | 21.44 |

Codon optimization and in-silico cloning

In-silico cloning to work it was necessary to adapt the codon sequence of constructed vaccine to be expressed in the E.coli expression system. Therefore, for the incorporation of the vaccine construct in the plasmid vector, the 840 amino acid sequence of the vaccine construct is reverse translated into the cDNA of 2520 nucleotide. The resultant cDNA was codon optimized to ensure efficient expression of the constructed vaccine epitope in the Escherichia coli K12 host by using the JCAT server. To ensure efficient transcription to occur, exclusion of the rho-independent transcription termination site and restriction enzyme site from the cDNA sequence. Before adaptation, the cDNA sequence CAI value was 0.59 and its GC content was 56.4%. After the codon adaptation, CAI value increases from 0.59 to 0.96 With 50.2% of GC content. The increased CAI value shows that optimized cDNA has majority of codons that are often used in Escherichia coli k12 (Figs. 11, 12).

Fig. 11.

No. of hydrogen bonds throughout the MD simulations

Fig. 12.

Codon adaptation. cDNA sequence A before adaptation B after adaptation

Next, cDNA of the constructed vaccine was reversed then at 5’site XhoI was added, and at 3’end BamHI was incorporated. By using SnapGene, the restriction enzyme BamHI and XhoI cleaved at their respective sites of the pET28a( +) expression vector. So, that cDNA can be inserted in between the cleaved site of the pET28a( +) vector, and for isolation and purification of vaccine construct 6 mer histidine tag was added to the C-terminal end. Vaccine gene depicted in blue color and present in between the sites of XhoI and BamHI (Fig. 13).

Fig. 13.

In silico cloning of construct vaccine in pET28a( +)

Computational immune assay

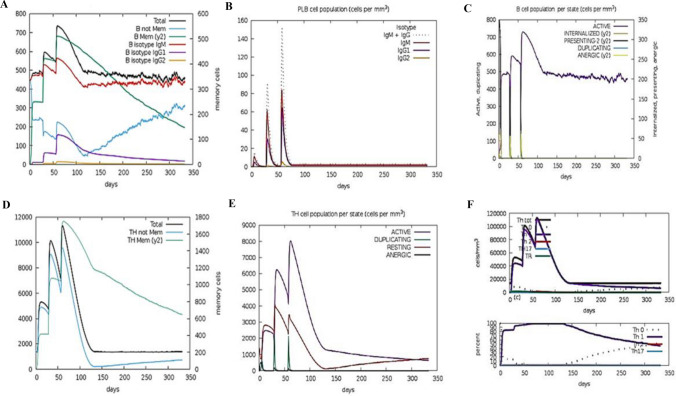

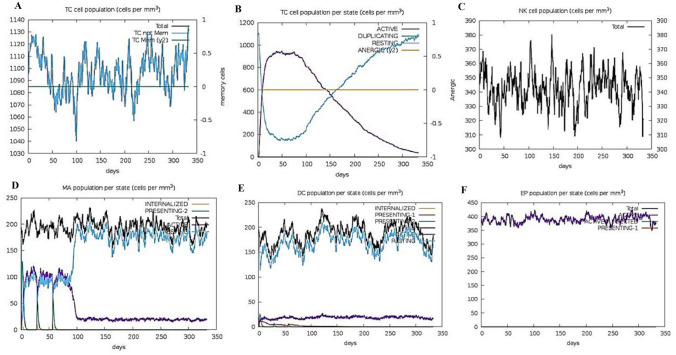

A computer-generated simulation of the immune system was conducted to identify immunological responses to the developed immunization. The findings revealed that it was effective in eliciting immunological responses, as the increase in the production of humoral antibodies was responsible for the drop in antigen count. The rise in the peak of IgG1 + IgG2 indicates elicitation of primary response due to which antigen level decreased after each injection (> 600,000 on the first dose and ~ 500,000 on the second and third doses), and it eventually leveled off on the fifth day after injection and this led to activation of secondary immunological response as the Fig. 14A data depicts the rise of IgM + IgG counts ~ 190,000 per ml in 10–15 days after each vaccination course. In response to injection, various cytokines such as IFN-γ, TGF-β, IL-10, and IFN-β levels have also risen shown in Fig. 14B. These secondary immune responses led to tertiary responses in the body which cause the activation of a large number of B- cells population Fig. 15A–C, similar trend has been shown with the activation of a large number of Helper T-cells Fig. 15D–F and cytotoxic T-cells Fig. 16A, B. These trends indicate that vaccination led to a successful secondary immunological response. It also led to an increase in the level of different types of innate immune responses Fig. 16C–F. These results suggest that the design of multi-epitope vaccines has the capability to trigger a powerful immune response against Monkeypox virus infection.

Fig. 14.

(A) Antibody and (B) cytokine responses to vaccination are predicted by the c-ImmSim service

Fig. 15.

Plots A–F depicting responses of Immune simulation of B-cells and T- helper cells in response to the vaccine construct

Fig. 16.

Plot showing A and B increase in cytotoxic T-cell population, and C–F an increase in the number of additional innate immune cells

Conclusion

The study utilizes the basic immunoinformatics approach for developing a new monkeypox multi-epitope vaccine candidate. The in-silico method is more effective than the traditional approach to creating vaccines, thus offering a dependable alternative in treating any infectious illness. The whole Monkeypox virus proteome was screened, and this led to the selection of appropriate CTLs, HTLs and B cell epitopes which were then combined into a multi-epitope vaccine construct that was found to be antigenic, non-allergenic and showed a sufficient immunogenic response when computationally analyzed. MD simulation showed that the tertiary structure of the vaccine construct and its interaction with TLR4 are stable. Additionally, an in-silico cloning approach was used to design a bacterial expression-based vector expressing the multi-epitope vaccination construct. In conclusion, the immunoinformatic technique creates a vaccine well suited for recent monkeypox virus outbreaks.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Prof. Amit Kumar and Dr. Parimal Kar for the computer server facility at IIT, Indore. AN would like to acknowledge the Council of Scientific & Industrial Research (CSIR), Govt. of India, New Delhi, AC, and NK to Department of Biotechnology, SS and SS to Ministry of Human Resource Development, Govt. of India, New Delhi for their individual fellowship.

Author contributions

All the authors have equal contributions.

Data availability

All the data generated or analyzed is available in the manuscript and in the supplementary file.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Babkin IV, Babkina IN, Tikunova NV. An update of orthopoxvirus molecular evolution. Viruses. 2022;14(2):388. doi: 10.3390/v14020388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berendsen HJC, Postma JPM, van Gunsteren WF, DiNola A, Haak JR. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J Chem Phys. 1984;81(8):3684–3690. doi: 10.1063/1.448118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Case D, Ben-Shalom I, Brozell SR, Cerutti DS, Cheatham T, Cruzeiro V WD, Darden T, Duke R, Ghoreishi D, Gilson M, Gohlke H, Götz A, Greene D, Harris R, Homeyer N, Huang Y, Izadi S, Kovalenko A, Kurtzman T, Kollman PA (2018) Amber 2018. 10.13140/RG.2.2.31525.68321

- Darden T, York D, Pedersen L. Particle mesh Ewald: an N⋅log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J Chem Phys. 1993;98(12):10089–10092. doi: 10.1063/1.464397. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doytchinova IA, Flower DR. VaxiJen : a server for prediction of protective antigens, tumour antigens and subunit vaccines. BMC Bioinform. 2007;8:1–4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Manzalawy Y, Dobbs D, Honavar V. Predicting linear B-cell epitopes using string kernels. J Mol Recognit. 2008;21(4):243–255. doi: 10.1002/jmr.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasteiger E, Gattiker A, Hoogland C, Ivanyi I, Appel RD, Bairoch A. ExPASy: the proteomics server for in-depth protein knowledge and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(13):3784–3788. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohlke H, Case DA. Converging free energy estimates: MM-PB(GB)SA studies on the protein-protein complex Ras-Raf. J Comput Chem. 2004;25(2):238–250. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohlke H, Kiel C, Case DA. Insights into protein-protein binding by binding free energy calculation and free energy decomposition for the Ras-Raf and Ras-RalGDS complexes. J Mol Biol. 2003;330(4):891–913. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00610-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonniya NA, Sk MF, Kar P. A comparative study of structural and conformational properties of WNK kinase isoforms bound to an inhibitor: insights from molecular dynamic simulations. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2022;40(3):1400–1415. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1827035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi A, Sasumana J, Ray NM, Kaushik V. Neural network analysis. In: Singh V, Kumar A, editors. Advances in bioinformatics. Singapore: Springer Singapore; 2021. pp. 351–364. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi A, Ray NM, Singh J, Upadhyay AK, Kaushik V. T-cell epitope-based vaccine designing against Orthohantavirus: a causative agent of deadly cardio-pulmonary disease. Netw Model Anal Health Inform Bioinform. 2022;11(1):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s13721-021-00339-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi A, Akhtar N, Sharma NR, Kaushik V, Borkotoky S. MERS virus spike protein HTL-epitopes selection and multi-epitope vaccine design using computational biology. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2023;41(22):12464–12479. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2023.2191137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung D, Jeong SK, Lee CM, Noh KT, Heo DR, Shin YK, Yun CH, Koh WJ, Akira S, Whang J, Kim HJ, Park WS, Shin SJ, Park YM. Enhanced efficacy of therapeutic cancer vaccines produced by Co-treatment with mycobacterium tuberculosis heparin-binding hemagglutinin, a novel TLR4 agonist. Can Res. 2011;71(8):2858–2870. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaler J, Hussain A, Flores G, Kheiri S, Desrosiers D. Monkeypox: a comprehensive review of transmission, pathogenesis, and manifestation. Cureus. 2022;14(7):1–11. doi: 10.7759/cureus.26531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollman PA, Massova I, Reyes C, Kuhn B, Huo S, Chong L, Lee M, Lee T, Duan Y, Wang W, Donini O, Cieplak P, Srinivasan J, Case DA, Cheatham TE., 3rd Calculating structures and free energies of complex molecules: combining molecular mechanics and continuum models. Acc Chem Res. 2000;33(12):889–897. doi: 10.1021/ar000033j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozakov D, Beglov D, Bohnuud T, Mottarella SE, Xia B, Hall DR, Vajda S. How good is automated protein docking? Proteins. 2013;81(12):2159–2166. doi: 10.1002/prot.24403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kräutler V, Van Gunsteren WF, Hünenberger PH. A fast SHAKE algorithm to solve distance constraint equations for small molecules in molecular dynamics simulations. J Comput Chem. 2001;22(5):501–508. doi: 10.1002/1096-987X(20010415)22:5<501::AID-JCC1021>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan GS, Joshi A, Akhtar N, Kaushik V. Immunoinformatics designed T cell multi epitope dengue peptide vaccine derived from non structural proteome. Microbial Pathog. 2021;150(December 2020):104728. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2020.104728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai C-C, Hsu C-K, Yen M-Y, Lee P-I, Ko W-C, Hsueh P-R. Monkeypox: An emerging global threat during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal ofMicrobiology, Immunology and Infection. 2022;55(5):787–794. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2022.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26(2):283–291. doi: 10.1107/s0021889892009944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maier JA, Martinez C, Kasavajhala K, Wickstrom L, Hauser KE, Simmerling C. ff14SB: improving the accuracy of protein side chain and backbone parameters from ff99SB. J Chem Theory Comput. 2015;11(8):3696–3713. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masulli F, Mitra S. Natural computing methods in bioinformatics: a survey. Inf Fusion. 2009;10(3):211–216. doi: 10.1016/j.inffus.2008.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BR, McGee TDJ, Swails JM, Homeyer N, Gohlke H, Roitberg AE. MMPBSA.py: an efficient program for end-state free energy calculations. J Chem Theory Comput. 2012;8(9):3314–3321. doi: 10.1021/ct300418h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naveed M, Ahmed I, Khalid N, Mumtaz AS. Bioinformatics based structural characterization of glucose dehydrogenase (gdh) gene and growth promoting activity of Leclercia sp. QAU-66. Braz J Microbiol. 2014;45(2):603–611. doi: 10.1590/s1517-83822014000200031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naveed M, Mubeen S, Khan S, Ahmed I, Khalid N, Suleria HAR, Bano A, Mumtaz AS. Identification and characterization of rhizospheric microbial diversity by 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing. Braz J Microbiol. 2014;45(3):985–993. doi: 10.1590/s1517-83822014000300031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naveed M, Tehreem S, Mubeen S, Nadeem F, Zafar F, Irshad M. In-silico analysis of non-synonymous-SNPs of STEAP2: to provoke the progression of prostate cancer. Open Life Sci. 2016;11(1):402–416. doi: 10.1515/biol-2016-0054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nezafat N, Ghasemi Y, Javadi G, Khoshnoud MJ, Omidinia E. A novel multi-epitope peptide vaccine against cancer: an in silico approach. J Theor Biol. 2014;349:121–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2014.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey RK, Bhatt TK, Prajapati VK. Novel immunoinformatics approaches to design multi-epitope subunit vaccine for malaria by investigating anopheles salivary protein. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-19456-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandya N, Kumar A. Immunoinformatics analysis for design of multi-epitope subunit vaccine by using heat shock proteins against Schistosoma mansoni. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2023;41(5):1859–1878. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2021.2025430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastor RW, Brooks BR, Szabo A. An analysis of the accuracy of Langevin and molecular dynamics algorithms. Mol Phys. 1988;65(6):1409–1419. doi: 10.1080/00268978800101881. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen E, Kantele A, Koopmans M, Asogun D, Yinka-Ogunleye A, Ihekweazu C, Zumla A. Human Monkeypox: epidemiologic and clinical characteristics, diagnosis, and prevention. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2019;33(4):1027–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2019.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price DJ, Brooks CL., 3rd A modified TIP3P water potential for simulation with Ewald summation. J Chem Phys. 2004;121(20):10096–10103. doi: 10.1063/1.1808117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapin N, Lund O, Bernaschi M, Castiglione F. Computational immunology meets bioinformatics: the use of prediction tools for molecular binding in the simulation of the immune system. PLoS ONE. 2010 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynisson B, Alvarez B, Paul S, Peters B, Nielsen M. NetMHCpan-4.1 and NetMHCIIpan-4.0: improved predictions of MHC antigen presentation by concurrent motif deconvolution and integration of MS MHC eluted ligand data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;48(W1):449–454. doi: 10.1093/NAR/GKAA379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe DR, Cheatham TE. PTRAJ and CPPTRAJ: software for processing and analysis of molecular dynamics trajectory data. J Chem Theory Comput. 2013;9(7):3084–3095. doi: 10.1021/ct400341p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sami SA, Marma KKS, Mahmud S, Khan MAN, Albogami S, El-Shehawi AM, Rakib A, Chakraborty A, Mohiuddin M, Dhama K, Uddin MMN, Hossain MK, Tallei TE, Emran TB. Designing of a multi-epitope vaccine against the structural proteins of marburg virus exploiting the immunoinformatics approach. ACS Omega. 2021;6(47):32043–32071. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.1c04817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shantier SW, Mustafa MI, Abdelmoneim AH, Fadl HA, Elbager SG, Makhawi AM. Novel multi epitope-based vaccine against monkeypox virus: vaccinomic approach. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):1–17. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-20397-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shchelkunova GA, Shchelkunov SN. Smallpox, Monkeypox and other human orthopoxvirus infections. Viruses. 2022;15(1):103. doi: 10.3390/v15010103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sk MF, Kar P. Finding inhibitors and deciphering inhibitor-induced conformational plasticity in the Janus kinase via multiscale simulations. SAR QSAR Environ Res. 2022;33(11):833–859. doi: 10.1080/1062936X.2022.2145352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sk MF, Roy R, Jonniya NA, Poddar S, Kar P. Elucidating biophysical basis of binding of inhibitors to SARS-CoV-2 main protease by using molecular dynamics simulations and free energy calculations. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2021;39(10):3649–3661. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1768149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sk MF, Jonniya NA, Roy R, Kar P. Unraveling the molecular mechanism of recognition of selected next-generation antirheumatoid arthritis inhibitors by Janus Kinase 1. ACS Omega. 2022;7(7):6195–6209. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.1c06715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue LC, Rodrigues JP, Kastritis PL, Bonvin AM, Vangone A. PRODIGY: a web server for predicting the binding affinity of protein-protein complexes. Bioinformatics (oxford, England) 2016;32(23):3676–3678. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the data generated or analyzed is available in the manuscript and in the supplementary file.