Abstract

Background:

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Alberta was on track to meet national HCV elimination targets by 2030. However, it is unclear how the pandemic has affected progress. Here, we aim to assess the impact of first-wave COVID-19 restrictions on Alberta HCV testing trends.

Methods:

HCV testing information was extracted from the provincial public health laboratory from 2019 to 2022. HCV antibody and RNA testing were categorized into (1) number ordered, (2) number positive, and (3) percent positivity, and stratified by HCV history status. Testing trends were evaluated across locations engaging high-risk individuals and priority demographics. An interrupted time-series analysis was used to identify average monthly testing rates before, during, and after first-wave COVID-19 restrictions.

Results:

Overall, HCV testing trends were significantly affected by COVID-19 restrictions in April 2020. Average monthly rates decreased by 98.39 antibody tests ordered per 100,000 among individuals without an HCV history and by 1.78 RNA tests ordered per 100,000 among those with an HCV history. While antibody and RNA testing trends started to rebound in the follow-up period relative to pre-restriction period, testing levels in the follow-up period remained below pre-restriction levels for all groups, except for addiction/recovery centres and emergency room/acute care facilities, which increased.

Conclusions:

If rates are to return to pre-restriction levels and elimination goals are to be met, more work is needed to engage individuals in HCV testing. As antibody testing rates are rebounding, reengaging those with a history of HCV for viral load monitoring and treatment should be prioritized.

Keywords: COVID-19, hepatitis C virus, interrupted time-series, priority populations, rates, testing, trends

Lay summary: Before the emergence of COVID-19, Alberta was on track to meet national HCV elimination targets by the year 2029. However, the COVID-19 pandemic caused the shifting of public health resources away from HCV, likely disrupting HCV elimination progress. In this paper, we graphed monthly HCV testing levels in Alberta from 2019 to 2022 and used statistical analyses to identify how first-wave COVID-19 restrictions affected HCV diagnosis among individuals who have never had HCV (IWHAB) and viral load monitoring among those who have previously been diagnosed with HCV (IHAB). We found that rates of HCV antibody screening among IWHAB were stable in 2019 but decreased significantly in April 2020 when first-wave restrictions were implemented. Following first-wave restrictions, monthly HCV antibody testing levels started slowly rebounding but remained below pre-restriction levels at the end of 2022. Levels of HCV RNA testing among IHAB were already decreasing in the pre-restriction period and decreased even more with first-wave restrictions, also remaining below pre-restriction levels at the end of 2022. Furthermore, we evaluated HCV testing trends among priority demographic groups (health zone, birth cohort, individuals residing in rural areas, and those residing in low-income neighbourhoods) and locations engaging priority populations for HCV elimination efforts (provincial correctional facilities, addiction/recovery centres, sexually transmitted infection (STI) clinics, and urgent care facilities/emergency rooms). We found similar HCV antibody and RNA testing trends among all populations as we did for IWHAB and IHAB, except for individuals tested through addiction/recovery centres and urgent care facilities/emergency rooms, where HCV antibody and RNA testing increased in the follow-up compared to pre-restriction period. As HCV elimination efforts rely on testing for diagnosis and monitoring, more work is needed to increase HCV antibody testing among IWHAB and RNA testing among IHAB if HCV elimination targets are to be met in Alberta.

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a bloodborne pathogen and a leading etiology of chronic liver disease (1). The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates there are 58 million chronic HCV infections worldwide and approximately 290,000 individuals died from HCV-related causes in 2019 (2). Due to its asymptomatic nature, HCV can remain subclinical for long periods of time (3), making diagnosis difficult. Advances in HCV testing coupled with models of decentralized care have improved testing availability, and public health strategies engaging priority populations have improved early detection rates among high-risk individuals (4–7).

In 2016, the WHO aimed to eliminate viral hepatitis as a global public health threat by the year 2030 (8). HCV elimination targets include treating 80% of eligible individuals, reducing incidence by 90%, and decreasing HCV-associated liver mortality by 65%. Achievement of these goals requires scale-up of HCV testing and diagnosis among priority populations. In 2019 the Canadian Network on Hepatitis C published the Blueprint to Inform Hepatitis C Elimination Efforts in Canada, which identified six priority populations in Canada to focus elimination efforts: Indigenous populations, gay or bisexual men who have sex with men (gbMSM), people who inject drugs (PWID), people who are incarcerated (PWAI), newcomers to Canada, and the birth cohort (those born between 1945 and 1975) (9).

In a recent report, Feld et al showed Alberta was on track to meet elimination targets by 2029 (10). However, the study analyzed progress up until 2019, before the emergence of COVID-19. It is therefore unclear how the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted progress towards HCV elimination, and whether progress has been disproportionally affected across priority population demographics. Here, we aimed to characterize the effect of first-wave COVID-19 restrictions on HCV testing trends across Alberta and evaluate trends across priority populations and locations engaging them. We further stratified analyses by individuals without a history of HCV antibody positivity (IWHAB) and individuals with a history of HCV antibody positivity (IHAB) to identify how trends differed for diagnostic testing among IWHAB versus viral load monitoring among IHAB.

Methods

HCV testing in Alberta

All HCV testing in Alberta is centralized to the provincial public health laboratory (Alberta Precision Laboratories; Public Health Laboratory; ProvLab). Although HCV antibody point-of-care screening (OraQuick® HCV Test, OraSure Technologies, Pennsylvania, USA) is available in community-based settings, all positive tests are centrally confirmed at the Public Health Laboratory via venepuncture samples. Prior to December 12, 2019, HCV testing was performed using a two-sample method: (1) one blood sample was screened for HCV antibodies on the Abbott ARCHITECT i2000SR (Architect Anti-HCV, Abbott Laboratories, Illinois, USA), and if positive (2) a second sample was requested to determine infection status via molecular testing on the Abbott m2000 RealTime System (Abbott RealTime HCV Assay, Abbott Laboratories, Illinois, USA). Starting December 12, 2019, HCV reflex testing was implemented (11), where samples screening positive for HCV antibodies on the Abbott ARCHITECT i2000SR are automatically transferred to the Roche cobas6800 (cobas HCV, Roche Diagnostics, Indiana, USA) for molecular confirmation (using a single sample). Concurrently, utilization rules were implemented in the Public Health Laboratory for HCV testing on IHAB, where an individual with a previously confirmed positive antibody test would have subsequent antibody requests cancelled with a note to the ordering physician to use nucleic acid testing (NAT) for monitoring infection status or therapy response. Previously positive individuals are identified using a continuous computational lookback (CCL) code of personal health numbers in the Public Health Laboratory Information System (LIS). Additionally, universal prenatal HCV screening was implemented on February 27, 2020 in Alberta (12), where HCV antibody screening is performed for all pregnant individuals, regardless of HCV history, and molecular reflex testing is used to diagnose active infections.

First-wave COVID-19 restrictions and public health measures in Alberta

The first case of COVID-19 was detected in Alberta on March 5, 2020 (13) and the Government of Alberta declared a public health state of emergency on March 17, 2020. Restrictions were quickly implemented across the province and included physical distancing, mandatory self-isolation for travellers, suspension of in-person education, wearing of medical face coverings, work from home orders, limitations on the number of individuals in public venues, and restrictions on visitors in health care facilities. During this time, all COVID-19 testing in the province was performed at the Public Health Laboratory (14), with testing volumes increasing substantially every week. On March 25, 2020, daily HCV RNA testing was decreased to two runs per week to prioritize the shifting of resources to COVID-19 testing (15), and on April 3, 2020, all routine laboratory testing, including HCV, was suspended for non-emergent cases (16). The first public health state of emergency was officially declared over on June 15 (13), and by June 22 patient service centres, collection locations, and provincial public health laboratory testing had resumed routine operations back to 70% of pre-pandemic capacity (17).

Cohort definitions and trend analyses

The impact of first-wave COVID-19 restrictions on HCV testing was determined by evaluating monthly HCV antibody and RNA testing trends between January 1, 2019 and December 31, 2022. HCV antibody and RNA outcomes were evaluated in three categories: (1) number of tests ordered, (2) number of tests positive, and (3) percent positivity of tests ordered. Testing trends were assessed for the entire population, prenatal patients, IWHAB/IHAB, by locations engaging large numbers of high-risk individuals (provincial correctional facilities, addiction/recovery centres, sexually transmitted infection [STI] clinics, urgent care facilities/emergency rooms) and by priority demographics (health zone, birth cohort, individuals residing in rural areas, and those residing in low-income neighbourhoods). Prior to February 2020, prenatal HCV testing was defined as any HCV test performed 100 days before to 300 days after an individual's prenatal communicable disease screening panel. After February 2020, universal prenatal HCV screening was identified directly through the LIS. IHAB were defined as those with a recorded positive antibody or RNA result in the LIS. Locations engaging high-risk individuals were identified by submitter location name from HCV testing requisitions. Specimens submitted from adult correctional facilities, remand centres, and young offender centres were universally referred to as being submitted by ‘provincial correctional facilities.’ Individuals residing in rural geographic locations and neighbourhoods of the lowest income quintile were determined using postal code-associated 2016 Alberta census estimates. The number of tests ordered and positive were assessed for significant changes in trends over the study period using Mann–Kendall statistical tests and trend changes in percent positivity were assessed for statistical significance using Cochrane–Armitage tests (Supplementary Table 1). Outcomes are displayed in counts and percentages.

Interrupted time-series analyses

To evaluate the effect size of monthly HCV testing changes, an interrupted time-series analysis was conducted. Briefly, an interrupted time-series analysis is used to evaluate changes in a given outcome when an intervention is introduced at a specified time point. It uses segmented regression analyses to determine effect sizes in trends before, during, and after an intervention is introduced, as previously described (18). Here, the intervention was defined as the introduction of first-wave COVID-19 restrictions, the pre-restriction period was defined as January 2019–March 2020, the restriction (intervention) period as April 2020, and the follow-up period as May 2020–December 2022. Number and percent positivity of HCV antibody and RNA tests were converted to monthly rates using Alberta population estimates from 2019 to 2022. Population estimates for IHAB were calculated using a provincial seroprevalence of 0.7% (19), and estimates for IWHAB were calculated by subtracting the estimated number of seropositive individuals from total population numbers in a given year. The itsa command in Stata v15.1 was used to conduct the interrupted time-series analysis following the Newey-West OLS regression-based model. The general model equation was: Yt = β0 + β1Tt + β2Xt + β3XtTt + €t, where Yt = average monthly test rate; β0 = baseline average monthly test rate before restrictions; β1 = average change in monthly test rates before restrictions; β2 = average change in monthly test rates when restrictions were first implemented; β3 = average change in monthly tests rates in the follow-up period after restrictions were implemented, relative to the pre-restriction period; Tt = time in months; Xt = internally coded variable representing time period before (coded as 0) or after (coded as 1) restrictions were implemented; and €t represents the random variability in the model. The average change in monthly test rates during the follow-up period was determined using the posttrend command, representative of the difference between β3 and β1. The actest command was used to assess for serial autocorrelation with the Cumby-Huizinga test. Outcomes are displayed using population-standardized monthly rate estimates (per 100,000), and the interrupted time series analysis was also performed on monthly HCV antibody and RNA test counts among IWHAB and IHAB (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3).

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses and trend visuals were conducted in Stata v15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA). Statistical significance was set at α = 0.05.

Ethics statement

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the University of Alberta Research Ethics Board (Pro00080186). Patient consent for accessing personally identifiable information was waived under the Health Information Act section 50(1)(a).

Results

Overall trends in HCV testing levels from 2019 to 2022

When examining all HCV antibody tests ordered across the province, the number of tests remained stable in the pre-restriction period, with a large drop in number of tests ordered once restrictions were first implemented (Supplementary Figure 1, top left, blue & red). The number of antibody tests ordered increased to pre-restriction levels in the follow-up period, with numbers slightly above pre-restriction levels by the end of 2022 (Supplementary Figure 1, top left, yellow). However, a universal prenatal HCV antibody screening program was implemented in Alberta at the end of February 2020 and remained stable over the rest of the study period (Supplementary Figure 2, top left, second dotted line), creating bias in overall HCV testing numbers. All prenatal HCV tests were therefore excluded from the dataset and trends were re-examined (Supplementary Figure 3). Excluding prenatal testing, the number of HCV antibody tests ordered remained stable in the pre-restriction period, dropped significantly with the implementation of restrictions, and remained below pre-restriction levels in the follow-up period, with a slowly increasing trend that remained below pre-restriction levels at the end of 2022 (Supplementary Figure 3, top left, blue, red, yellow, respectively). Similar trends were observed with HCV RNA testing when prenatal tests were excluded (Supplementary Figure 3, top, middle, and bottom right), where ordered, positive, and percent positivity dropped in the month of restriction implementation (red); however, trends in HCV RNA tests continued to decrease in the follow-up period (yellow). Although the overall number of antibody tests ordered were below pre-restriction levels in the follow-up period (Supplementary Figure 3, top left, yellow versus blue), the total number of tests positive for HCV antibodies rebounded back to pre-restriction levels (Supplementary Figure 3, middle left, yellow versus blue).

Trends in HCV testing levels and interrupted time-series for IWHAB

Before first-wave COVID-19 restrictions were implemented in Alberta, ordering of HCV antibody tests among IWHAB remained stable (Figure 1, top left, blue), with no significant change in average monthly rates of HCV antibody tests ordered (Table 1, −5.12 tests per 100,000, p = 0.081). Once first-wave COVID-19 restrictions were implemented, the average monthly rate of HCV antibody tests ordered fell across the province by 98.39 tests per 100,000 (Table 1, p = 0.040 and Figure 1; top left, red), but rebounded in the follow-up period, with an increasing average monthly rate of 3.30 tests per 100,000 population until the end of 2022 (Table 1, p = 0.008 and Figure 1, top left, yellow). Compared to the rate of HCV antibody tests ordered before restrictions, the average monthly rate of HCV antibody tests ordered was higher (Table 1, 8.42 per 100,000 population, p = 0.016), although remained below pre-restriction testing levels at the end of 2022 (Figure 1, top left, yellow versus blue). Monthly rates of positive HCV antibody tests also declined with the introduction of restrictions (Figure 1, middle left, red), decreasing by 1.14 positive tests per 100,000 (Table 1, p = 0.040). Although there was an increasing trend in the pre-restriction period for antibody percent positivity (Figure 1, bottom left, blue), the rate of percent positivity decreased in the follow-up period (Figure 1, bottom left, yellow and Table 1, −14.26 per 100,000, p < 0.001), and was lower than the pre-restriction period (Table 1, −29.19 per 100,000, p = 0.001). HCV RNA tests ordered remained consistent in the pre-restriction period up until December 2019, when HCV reflex testing was implemented (Figure 1, top right, first dotted line), corresponding to a large spike in the number of positive tests and percent positivity (Figure 1, middle and bottom right, first dotted line). No significant differences were seen in the rates of HCV RNA tests ordered or positive among IWHAB, nor were there any differences in rates of percent positivity (Table 1), although overall levels of all three were higher in the follow-up period (Figure 1, right panels, yellow).

Figure 1:

Trends in monthly HCV testing levels for individuals without a history of antibody positivity (IWHAB) across Alberta from Jan 1, 2019 to Dec 31, 2022, prenatal HCV tests excluded. Blue: period before COVID-19 restrictions (January 2019–March 2020); red: implementation of first-wave COVID-19 restrictions (April 2020); yellow: follow-up period after first-wave COVID-19 restrictions were introduced (May 2020–December 2022). --···--···-- denotes month of HCV reflex testing implementation (December 2019); -------- denotes universal prenatal HCV screening implementation (March 2020)

Table 1:

Interrupted time-series analysis for monthly HCV testing rates among IWHAB in Alberta from Jan 1, 2019 to Dec 31, 2022, prenatal HCV tests excluded

| Test measure | Baseline average monthly rates† before first-wave restrictions (Jan 2019–Mar 2020) | Change in average monthly rates before first-wave restrictions (Jan 2019–Mar 2020) | Change in average monthly rates when restrictions were first introduced (Apr 2020) | Change in average monthly rates in follow-up period after first-wave restrictions were first implemented (May 2020–Dec 2022) | Change in average monthly rates after first-wave restrictions were implemented (May 2020–Dec 2022), relative to before restrictions (Jan 2019–Mar 2020) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β estimate (per 100,000) | β estimate (per 100,000) | p | β estimate (per 100,000) | p | β estimate (per 100,000) | p | β estimate (per 100,000) | p | |

| AB Ordered | 452.41 | −5.12 | 0.081 | −98.39 | 0.004* | 3.30 | 0.008* | 8.42 | 0.016* |

| AB Positive | 5.60 | −0.01 | 0.848 | −1.14 | 0.040* | 0.04 | 0.839 | 0.01 | 0.813 |

| AB Percent Positivity | 1,231.15 | 14.93 | 0.052 | 119.18 | 0.240 | −14.26 | <0.001* | −29.19 | 0.001* |

| RNA Ordered | 6.28 | 0.17 | 0.104 | −1.18 | 0.304 | −0.03 | 0.154 | −0.20 | 0.065 |

| RNA Positive | 1.50 | 0.06 | 0.326 | −0.36 | 0.558 | −0.01 | 0.095 | −0.07 | 0.238 |

| RNA Percent Positivity | 24,312.32 | 78.05 | 0.845 | 880.73 | 0.827 | −91.87 | 0.124 | −169.91 | 0.678 |

p < 0.05 is significant

Rates calculated using annual Alberta population estimates from 2019 to 2022

AB = Antibody; HCV = Hepatitis C virus; IWHAB = Individuals without a history of antibody positivity; RNA = Ribonucleic acid

Trends in HCV testing levels were also evaluated for IWHAB across locations that engage high-risk priority populations (provincial correctional facilities, addiction/recovery centres, STI clinics, and urgent care facilities/emergency rooms) and across priority demographic groups (health zones, birth cohort, individuals residing in rural regions, and those from the lowest income quintile). Similar to Figure 1 (top left), the number of HCV antibody tests ordered across all groups evaluated dropped with restriction implementation and remained below pre-restriction levels in the follow-up period (data not shown), with the exception of addiction/recovery centres and urgent care facilities/emergency rooms, which increased above pre-restriction levels in the follow-up period (Supplementary Figures 4 and 5, top left, yellow versus blue). Trends in positive antibody tests and percent positivity were also stable or increased in the follow-up period across addiction/recovery centres and urgent care facilities/emergency rooms (Supplementary Figures 4 and 5, middle and bottom left, yellow). HCV RNA trends across addiction/recovery centres and urgent care facilities/emergency rooms (Supplementary Figures 4 and 5, right panels) reflected similar overall trends described for all IWHAB (Figure 1, right panels), with no significant differences seen in rates of HCV RNA tests ordered, positive, or percent positivity, but where overall levels of all three were stable or slightly higher in the follow-up period.

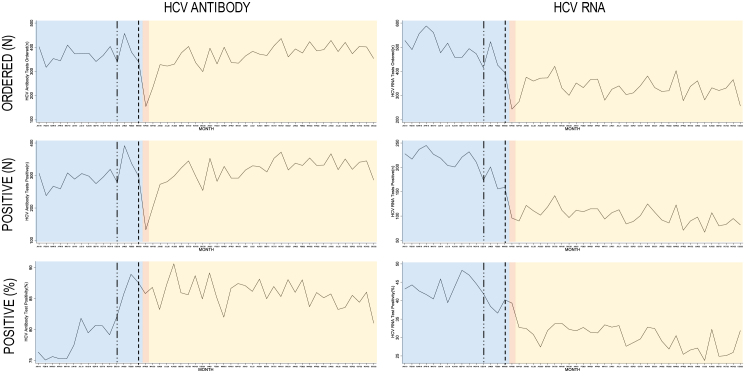

Trends in HCV testing levels and interrupted time-series for IHAB

Among IHAB, the number of antibody tests ordered remained stable in the pre-restriction period (Figure 2, top left, blue and Table 2, 0.02 per 100,000, p = 0.632), fell with the introduction of restrictions (Figure 2, top left, red and Table 2, −1.71 per 100,000, p = 0.016), rebounded in the following months (Figure 2, top left, yellow and Table 2; 0.07 per 100,000, p = 0.017), and then returned to pre-pandemic levels (Figure 2, top left, yellow versus blue and Table 2, 0.05 per 100,000, p = 0.421). A similar trend occurred for antibody positive tests, where rates increased in the pre-restriction period (Figure 2, middle left, blue and Table 2; 0.10 per 100,000, p = 0.027), decreased with first-wave restrictions (Figure 2, middle left, red and Table 2, −1.49 per 100,000, p = 0.021), and then increased in the follow-up period until the end of 2022 (Figure 2, middle left, yellow and Table 2, 0.06 per 100,000, p = 0.040). Compared to the pre-restriction period, rates of positive antibody tests in the follow-up period were not significantly different (Table 2, middle left, yellow versus blue and Table 2, −0.04 per 100,000, p = 0.450). Rates of percent positivity showed an increasing trend in the pre-restriction period (Figure 2, bottom left, blue and Table 2, 913.97 per 100,000, p < 0.001), corresponding to when a CCL lookback code was implemented in the provincial laboratory concurrently with reflex testing to identify IHAB (first dotted line). A non-significant decrease in percent positivity rates was observed after implementing restrictions (Figure 2, bottom left, red and Table 2, −246.11 per 100,000, p = 0.882), followed by a decreasing rate in the follow-up period (Figure 2, bottom left, yellow and Table 2, −78.29 per 100,000, p = 0.028). Percent positivity rates fell in the follow-up compared to pre-restriction period (Table 2, −992.27 per 100,000, p < 0.001), but overall levels were higher (Figure 2, bottom left, yellow versus blue). All HCV RNA trends decreased in the pre-restriction period (Figure 2, top, middle, and bottom right, blue and Table 2, ordered: −0.21 per 100,000, p = 0.001; positive: −0.11 per 100,000, p < 0.001; percent positivity: −225.31 per 100,000, p = 0.199), fell with restriction implementation (Figure 2, top, middle, and bottom right, red and Table 2, ordered: −1.78 per 100,000, p = 0.005; positive: −1.28 per 100,000, p < 0.001; percent positivity: −6763.02 per 100,000, p = 0.007), and continued to decrease in the follow-up period (Figure 2, top, middle, and bottom right, yellow and Table 2, ordered: −0.02 per 100,000, p = 0.372; positive: −0.02 per 100,000, p = 0.001; percent positivity: −227.89 per 100,000, p < 0.001). All levels in the follow-up period remained below those in the pre-restriction period (Figure 2, right panels, yellow versus blue), although rates of RNA tests ordered and positive RNA tests increased in the follow-up period relative to the pre-restriction period (Table 2, 0.19 per 100,000, p = 0.005 and 0.09 per 100,000, p = 0.003, respectively), while percent positivity rates did not significantly change (Table 2; −2.59 per 100,000, p = 0.989).

Figure 2:

Trends in monthly HCV testing levels for individuals with a history of antibody positivity (IHAB) across Alberta from Jan 1, 2019 to Dec 31, 2022, prenatal HCV tests excluded. Blue: period before COVID-19 restrictions (January 2019–March 2020); red: implementation of first-wave COVID-19 restrictions (April 2020); yellow: follow-up period after first-wave COVID-19 restrictions were introduced (May 2020–December 2022). --···--···-- denotes month of HCV reflex testing implementation (December 2019); -------- denotes universal prenatal HCV screening implementation (March 2020)

Table 2:

Interrupted time-series analysis for monthly HCV testing rates among IHAB in Alberta, Jan 1, 2019–Dec 31, 2022, prenatal HCV tests excluded

| Test measure | Baseline average monthly rates† before first-wave restrictions (Jan 2019–Mar 2020) | Change in average monthly rates before first-wave restrictions (Jan 2019–Mar 2020) | Change in average monthly rates when restrictions were first introduced (Apr 2020) | Change in average monthly rates in follow-up period after first-wave restrictions were first implemented (May 2020–Dec 2022) | Change in average monthly rates after first-wave restrictions were implemented (May 2020–Dec 2022), relative to before restrictions (Jan 2019–Mar 2020) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β estimate (per 100,000) | β estimate (per 100,000) | p | β estimate (per 100,000) | p | β estimate (per 100,000) | p | β estimate (per 100,000) | p | |

| AB Ordered | 8.39 | 0.02 | 0.632 | −1.71 | 0.016* | 0.07 | 0.017* | 0.05 | 0.421 |

| AB Positive | 6.18 | 0.10 | 0.027* | −1.49 | 0.021* | 0.06 | 0.040* | −0.04 | 0.450 |

| AB Percent Positivity | 73,679.49 | 913.97 | <0.001* | −246.11 | 0.882 | −78.29 | 0.028* | −992.27 | <0.001* |

| RNA Ordered | 12.78 | −0.21 | 0.001* | −1.78 | 0.005* | −0.02 | 0.372 | 0.19 | 0.005* |

| RNA Positive | 5.59 | −0.11 | <0.001* | −1.28 | <0.001* | −0.02 | 0.001* | 0.09 | 0.003* |

| RNA Percent Positivity | 44,146.43 | −225.31 | 0.199 | −6,763.02 | 0.007* | −227.89 | <0.001* | −2.59 | 0.989 |

p < 0.05 is significant

Rates calculated using annual Alberta population estimates from 2019 to 2022

AB = Antibody; HCV = Hepatitis C virus; IHAB = Individuals with a history of antibody positivity; RNA = Ribonucleic acid

HCV testing trends were also examined among IHAB across locations engaging high-risk populations and priority demographic groups, with a focus on RNA outcomes based on the decreasing trends seen in Figure 2. Like RNA results across all IHAB in Figure 2, there was a decreasing trend in all RNA outcomes across provincial correctional facilities, STI clinics, the birth cohort, all health zones, people residing in rural regions, and those from the lowest income quintile over the entire study period (data not shown). Conversely, there was a large increase in number of HCV RNA tests ordered from addiction/recovery centres and urgent care facilities/emergency rooms in the follow-up period (Supplementary Figures 6 and 7, top right, yellow), but no observable change in number of HCV RNA tests positive or percent positivity (Supplementary Figures 6 and 7, middle and bottom right, yellow).

Discussion

As 2030 draws closer, it is becoming increasingly important to monitor progress towards HCV elimination and identify gaps in testing, linkage to care, and treatment. In this paper, we evaluated the impact of first-wave COVID-19 restrictions on HCV testing rates in Alberta and analyzed effects among priority demographic populations and locations engaging them. With the implementation of first-wave restrictions, we observed significant decreases in HCV testing rates across the province in April 2020, consistent with findings from two other Canadian provinces (20,21) and studies outside of Canada (22). Although trends from Ontario showed decreased testing with second- and third-wave COVID-19 restrictions in October 2020 and April 2021 (20), Alberta HCV testing trends were mostly unaffected outside of the first wave, consistent with findings from British Columbia (21). One reason for these differences could be the utilization of HCV reflex testing methods in Alberta and British Columbia provincial laboratories (11,23), while Ontario employed a two-sample method (24). Our data showed a spike in HCV antibody tests ordered the month after reflex testing was implemented, suggesting health care providers may be more encouraged to order testing when reflex methods are in place. This is consistent with the Coalition for Global Hepatitis Elimination, which found reflex testing simplifies the testing process and makes ordering tests less confusing for providers (25), likely helping to maintain HCV testing rates during the second and third waves of COVID-19 in Alberta. Nonetheless, overall numbers of HCV testing remained below pre-pandemic levels in follow-up periods across all three provinces, highlighting the difficulties of re-establishing HCV health care services after the emergence of COVID-19. Interestingly, Alberta prenatal HCV testing rates were entirely unaffected by COVID-19 restrictions, consistent with Ontario findings (20), suggesting screening was continuously prioritized for pregnant individuals throughout the pandemic.

Due to differences in guidance for diagnostic testing versus viral load monitoring, we found antibody test trends were more affected among IWHAB while RNA testing rates were more affected among IHAB. Although rates of antibody tests ordered among IWHAB remained below pre-pandemic levels in the follow-up period, rates of percent positivity were higher, suggesting a higher proportion of at-risk IWHAB were being engaged in care even though overall testing levels were lower. Indeed, we observed that the lowest antibody testing levels among IWHAB correlated with the highest percent positivity during restriction implementation. This is surprising given that other publications have shown decreased HCV services among priority groups after COVID-19 emerged (26). However, the peak in antibody percent positivity during restriction implementation in 2020 likely reflects recommendations from the provincial public health laboratory to suspend routine HCV testing except for management of immediate cases (16), leading to a higher number of suspected HCV cases being tested at that time. Our data also showed both antibody and RNA percent positivity was increased among IWHAB in the follow-up period. Although these increases were not statistically significant, the overall increase in percent positivity can likely be explained by a combination of an increased number of high-risk IWHABs being engaged in care and utilization of reflex testing. This is further supported by the increase in HCV testing we saw during the follow-up period among IWHAB across addiction/recovery centres and urgent care facilities/emergency rooms. Although overall levels of antibody tests ordered remained below pre-pandemic levels at the end of 2022, levels were starting to increase back to those pre-restrictions, demonstrating HCV testing trends among IWHAB are becoming restabilized.

Among IHAB, rates of RNA testing were already decreasing in the pre-restriction period, which was further exacerbated by the emergence of COVID-19. This may have been caused by a true decrease in RNA testing or could reflect increased treatment and cure rates, leading to lower prevalence in the population and fewer people who would be monitored by RNA testing. Considering HCV treatment rates were shown to be decreased during the pandemic (27), our observed trends are likely a reflection of IHAB being lost to follow-up. The only population where these results differed were IHAB tested within addiction/recovery centres and urgent care facilities/emergency rooms, where we observed an increase in RNA tests ordered in the follow-up period. However, RNA percent positivity among these groups did not significantly increase. As IHAB have a history of HCV positivity, it is possible the lack of increase in RNA positivity may be from individuals that have already engaged in treatment and were being tested across these facilities for different reasons, such as to monitor for a sustained viral response during treatment or to monitor for reinfection among those already cured. Corroborating this idea, research has shown people who inject drugs and attend addictions programs or recovery centres are more likely to be treated for HCV and be monitored for reinfection (28). Interestingly, antibody testing trends among IHAB (reflecting repeat antibody testing) rebounded back to pre-restriction levels by the end of 2022. This is concerning given research has shown repeat antibody tests are more common among high-risk populations and are missed opportunities for proper viral load monitoring (29). Moving forward, efforts should therefore focus on reengaging IHAB back into care for viral load monitoring, linkage to care, and treatment.

As aforementioned, we observed an increase in antibody and RNA tests ordered among IWHAB and IHAB across addiction/recovery centres and emergency room/urgent care facilities during the follow-up period. The increase in emergency room/urgent care facilities is surprising given there were decreased hospital admittance numbers directly after first-wave COVID-19 restriction implementation (30). However, the surge of increases occurred in late 2021/early 2022, when admittance numbers were nearly back to pre-restriction levels. It is therefore possible the observed increases are from opportunistic HCV testing across Alberta facilities, as previously described in 2018 (31). Similarly, increased testing numbers across addiction/recovery centres in the follow-up period were likely due to a combination of the opioid crisis exacerbation during the pandemic (leading to increased admittance), and high screening rates across facilities (32,33).

Although we also examined HCV testing trends across provincial correctional facilities, STI clinics, health zones, the birth cohort, those residing in rural regions, and individuals from the lowest income quintile (data not shown), results reflected the same overall trends seen in Figures 1 and 2 for IWHAB and IHAB across the entire provincial population. However, the decreased rates of antibody and RNA testing across these groups during the follow-up period is especially concerning given they represent priority populations or proxy variables for priority populations that have been outlined for HCV elimination efforts (9). Existing HCV testing programs within provincial facilities may help rebound testing rates among some of these populations, such as opt-out HCV screening at admission across correctional facilities or co-localized HCV and STI testing across STI clinics (34,35). However, the birth cohort remains at higher risk for liver fibrosis and hepatocellular carcinoma and individuals residing in rural regions and those from the lowest income quintile remain disproportionately affected by HCV in Alberta (36). This highlights the need to find a balance in restoring HCV services that benefit the general population but that also address the social and behaviour-specific needs of priority populations if testing rates are to be restabilized in the future.

Data from this paper shed light on the difficulties of maintaining high quality HCV care during global pandemics and other health care crises. We showed a decrease in HCV testing across Alberta during the COVID-19 pandemic and a previous study has shown a decrease in HCV treatment across the province (27), highlighting disruptions to the HCV cascade of care. To mitigate the effects of future crises on HCV outcomes, novel service deliveries can be implemented to allow the continuation of care through alternative methods, such as telehealth. One study showed higher retention rates in fibrosis scoring, treatment initiation, and achievement of a sustained virological response for HCV positive individuals through telemedicine compared to in-person delivery models during the COVID-19 pandemic (37). While a study by Yeo et al. showed similar outcomes (38), they demonstrated positive telemedicine outcomes are dependent on socio-economic status and access to technology. Studies also suggest blood test-based fibrosis scoring, self-collection tests, and medication delivery by mail may be beneficial in maintaining HCV care when in-person delivery is limited (37,39).

Our retrospective study is limited by the availability of data for priority populations. While we were able to use proxy variables for four of six priority groups, our dataset lacked information on Indigenous populations and newcomers to Canada, as minimal data were available at the individualized level. HCV testing rates may therefore differ among these groups; however, overall trends seen for IWHAB and IHAB were consistent among most priority groups evaluated. Additionally, locations engaging priority groups were based on submitter location name, and therefore samples submitted under a different name but from the same location may have been misclassified. As separate dedicated molecular tests are used to evaluate viral load, guide treatment, and monitor for a sustained viral response, some patients in the IHAB dataset were represented multiple times. While this had the potential to bias outcomes by overinflating RNA testing numbers, our data showed overall decreased rates of RNA testing among IHAB. Lastly, interrupted time-series analyses could not be performed for testing trends across addiction/recovery centres and urgent care facilities/emergency rooms due to low monthly sample size numbers that would have underpowered the analysis at such a stratified level. Our research does however represent one of the first studies to investigate changes in testing trends across priority groups after COVID-19 emergence. HCV elimination efforts would benefit from future research investigating these outcomes across different jurisdictions and from extrapolating analyses to other steps in the HCV cascade of care.

Funding Statement

LAT is supported by a CIHR Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship, Killams Trust Scholarship, Women and Children's Health Research Institute (WCHRI) Graduate Studentship, University of Alberta Doctoral Recruitment Scholarship, and a CIHR Canada Graduate Scholarship-Master's Competition Award. This research otherwise received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors

Acknowledgements:

The authors gratefully acknowledge all the amazing staff at Alberta Precision Laboratories for dedicating their time and energy to communicable disease testing, especially during peak periods of the COVID-19 pandemic. They especially want to thank the ProvLab Surveillance Team for extracting and providing them with the HCV testing data over the study period. Lastly, they acknowledge the patients represented in their dataset for contributing to the advancement of public health and for whom their research would not be possible without.

Contributions:

Conceptualization, LA Thompson, SS Plitt, R Zhuo, CL Charlton; Methodology, LA Thompson, SS Plitt, R Zhuo, CL Charlton; Software, LA Thompson; Validation, LA Thompson, SS Plitt, R Zhuo, CL Charlton; Formal Analysis, LA Thompson; Investigation, LA Thompson, CL Charlton; Resources, CL Charlton; Data Curation, LA Thompson; Writing—Original Draft, LA Thompson; Writing—Review & Editing, LA Thompson, SS Plitt, R Zhuo, CL Charlton; Visualization, LA Thompson; Supervision, SS Plitt, CL Charlton; Project Administration, CL Charlton; Funding, CL Charlton.

Ethics Approval:

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the University of Alberta Research Ethics Board (Pro00080186).

Informed Consent:

Patient consent for accessing personally identifiable information was waived under the Health Information Act section 50(1)(a).

Registry and the Registration No. of the Study/Trial:

N/A

Data Accessibility Statement:

The data will not be made publicly available. Researchers interested in accessing the study data can contact the corresponding author for further information.

Funding:

LAT is supported by a CIHR Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship, Killams Trust Scholarship, Women and Children's Health Research Institute (WCHRI) Graduate Studentship, University of Alberta Doctoral Recruitment Scholarship, and a CIHR Canada Graduate Scholarship-Master's Competition Award. This research otherwise received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclosures:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Peer Review:

This manuscript has been peer reviewed.

Animal Studies:

N/A

Supplemental Material

References

- 1.Cheemerla S, Balakrishnan M. Global epidemiology of chronic liver disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2021;17(5):365–70. 10.1002/CLD.1061. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Hepatitis C; 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-c (Accessed July 29, 2022).

- 3.Modi AA, Liang TJ. Hepatitis C: a clinical review. Oral Dis. 2008;14(1):10. 10.1111/J.1601-0825.2007.01419.X. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel AA, Bui A, Prohl E, et al. Innovations in Hepatitis C screening and treatment. Hepatol Commun. 2021;5(3):371–86. 10.1002/HEP4.1646. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seña AC, Willis SJ, Hilton A, et al. Efforts at the frontlines: implementing a Hepatitis C testing and linkage-to-care program at the local public health level. Public Health Rep. 2016;131(Suppl 2):57–64. 10.1177/00333549161310S210. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ford MM, Jordan AE, Johnson N, et al. Check Hep C: a community-based approach to hepatitis c diagnosis and linkage to care in high-risk populations. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2018;24(1):41–8. 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000519. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morano JP, Zelenev A, Lombard A, Marcus R, Gibson BA, Altice FL. Strategies for Hepatitis C testing and linkage to care for vulnerable populations: point-of-care and standard HCV testing in a mobile medical clinic. J Community Health. 2014;39(5):922. 10.1007/S10900-014-9932-9. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. Global health sector strategy on viral hepatitis 2016-2021. Glob Hepat Program Dep HIV/AIDS. 2016;(June):56. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/246177. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canadian Network on Hepatitis C. Blueprint to inform Hepatitis C elimination efforts in Canada; 2019. www.canhepc.ca/en/blueprint/publication (Accessed January 28, 2020).

- 10.Feld JJ, Klein MB, Rahal Y, et al. Timing of elimination of hepatitis C virus in Canada's provinces. Can Liver J. 2022;5(4):493–506. 10.3138/canlivj-2022-0003. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson LA, Fenton J, Charlton CL. HCV reflex testing: a single-sample, low-contamination method to improve the efficiency of HCV diagnosis in patients from Alberta, Canada. J Assoc Med Microbiol Infect Dis Can. 2022;7(2):97–107. 10.3138/jammi-2021-0028. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charlton CL, Tipples G. Alberta precision laboratories: changes to the prenatal testing requisition. Edmonton; 2019. www.albertaprecisionlabs.ca (Accessed January 5, 2022).

- 13.Alberta Health. COVID-19 public health actions; 2020. https://www.alberta.ca/covid-19-public-health-actions.aspx (Accessed March 3, 2023).

- 14.Zelyas N, Tipples G. COVID-19 laboratory bulletin. Edmonton; 2020. https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/wf/lab/wf-lab-bulletin-novel-coronavirus-causing-covid-19-laboratory-update.pdf (Accessed March 3, 2023).

- 15.Charlton C, Tipples G. Changes to routine HBV, HCV and HIV viral load testing. Edmonton; 2020. https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/info/ppih/if-ppih-apl-bulletin-changes-routine-hbv-hcv-hiv-testing.pdf (Accessed March 3, 2023).

- 16.O’Hara C, Lai R. Clarification of cessation of routine laboratory testing during COVID-19 pandemic. Edmonton; 2020. https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/info/ppih/if-ppih-apl-memo-physicians-cease-non-essential-2020-04-03.pdf (Accessed March 3, 2023).

- 17.Phillips M. Relaunch of laboratory services in Alberta. Edmonton; 2020. https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/wf/lab/wf-lab-memo-collection-service-relaunch.pdf (Accessed March 3, 2023).

- 18.Linden A, Arbor A. Conducting interrupted time-series analysis for single-and multiple-group comparisons. Stata J. 2015;15(2):480–500. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Remis RS. Modelling the incidence and prevalence of hepatitis c infection and its sequelae in Canada, 2007. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2010. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/migration/phac-aspc/sti-its-surv-epi/model/pdf/model07-eng.pdf (Accessed March 3, 2023). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mandel E, Peci A, Cronin K, et al. The impact of the first, second and third waves of COVID-19 on hepatitis B and C testing in Ontario, Canada. J Viral Hepat. 2022;29(3):205–8. 10.1111/JVH.13637. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Binka M, Bartlett S, Velásquez García HA, et al. Impact of COVID-19-related public health measures on HCV testing in British Columbia, Canada: an interrupted time series analysis. Liver Int. 2021;41(12):2849–56. 10.1111/LIV.15074. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaufman HW, Bull-Otterson L, Meyer WA, et al. Decreases in hepatitis C testing and treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Prev Med. 2021;61(3):369–76. 10.1016/j.amepre.2021.03.011. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.BC Hepatitis Network. Hepatitis C testing; 2020. https://bchep.org/learn/hepatitis-testing/hepatitis-c-testing/ (Accessed March 8, 2023).

- 24.Public Health Ontario. Hepatitis C—diagnostic serology. 2022. https://www.publichealthontario.ca/en/laboratory-services/test-information-index/hepatitis-c-diagnostic-serology (Accessed March 8, 2023).

- 25.Coalition for Global Hepatitis Elimination. Optimizing HCV linkage to care: experiences implementing laboratory-based reflex testing. 2022. https://www.globalhep.org/webinars-events/webinars/optimizing-hcv-linkage-care-experiences-implementing-laboratory-based (Accessed April 19, 2024).

- 26.Delaunay CL, Greenwald ZR, Minoyan N, et al. Striving toward hepatitis C elimination in the era of COVID-19. Can Liver J. 2021;4(1):4. 10.3138/CANLIVJ-2020-0027. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee SS, Williams SA, Pinto J, Israelson H, Liu H. Treating hepatitis C during the COVID-19 pandemic in Alberta. Can Liver J. 2021;4(2):79. 10.3138/CANLIVJ-2021-0007. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Assoumou SA, Sian CR, Gebel CM, Linas BP, Samet JH, Bernstein JA. Patients at a drug detoxification center share perspectives on how to increase hepatitis c treatment uptake: a qualitative study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;220(1):108526. 10.1016/J.DRUGALCDEP.2021.108526. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsai V, Bornschlegel K, McGibbon E, Arpadi S. Duplicate hepatitis C antibody testing in New York City, 2006–2010. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(6):491. 10.1177/003335491412900607. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.AHS Planning and Performance. 2021-2022 Alberta health services annual report supplementary information. 2022. https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/about/publications/ahs-pub-pr-2021-22-q4-supplemental-information.pdf (Accessed March 9, 2023).

- 31.Ragan K, Pandya A, Holotnak T, Koger K, Collins N, Swain MG. Hepatitis C virus screening of high-risk patients in a Canadian emergency department. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;2020(1):1–6. 10.1155/2020/5258289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alberta Health. Alberta COVID-19 opioid response surveillance report. Edmonton; 2020. https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/f4b74c38-88cb-41ed-aa6f-32db93c7c391/resource/e8c44bab-900a-4af4-905a-8b3ef84ebe5f/download/health-alberta-covid-19-opioid-response-surveillance-report-2020-q2.pdf (Accessed March 9, 2023).

- 33.Canada's Source for HIV and Hepatitis C Information (CATIE). Hepatitis C treatment in harm reduction programs for people who use drugs. January 22, 2020. https://www.catie.ca/prevention-in-focus/hepatitis-c-treatment-in-harm-reduction-programs-for-people-who-use-drugs (Accessed March 9, 2023).

- 34.Reekie A, Gratrix J, Smyczek P, et al. A cross-sectional, retrospective evaluation of opt-out sexually transmitted infection screening at admission in a short-term correctional facility in Alberta, Canada. J Correct Health Care. 2022;28(6):429–38. 10.1089/JCHC.21.08.0079. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bryan Sluggett. A report on Alberta's community-based sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections programming. 2021. https://turningpoint-ca.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/A-Report-on-Albertas-Community-Based-STBBI-Programming-2021-2022.pdf (Accessed March 9, 2023).

- 36.O’Neil CR, Buss E, Plitt S, et al. Achievement of hepatitis C cascade of care milestones: a population-level analysis in Alberta, Canada. Can J Public Heal. 2019: 714–21. 10.17269/s41997-019-00234-z. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Brien M, Daws R, Amin P, Lee K. Utilizing telemedicine and modified fibrosis staging protocols tomaintain treatment initiation and adherence among hepatitis c patients during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Prim Care Community Health. 2022;13(1):1–7. 10.1177/21501319221108000. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yeo YH, Gao X, Wang J, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on the cascade of care of HCV in the US and China. Ann Hepatol. 2022;27(3):100685. 10.1016/J.AOHEP.2022.100685. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reipold EI, Farahat A, Elbeeh A, et al. Usability and acceptability of self-testing for hepatitis C virus infection among the general population in the Nile Delta region of Egypt. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1188. 10.1186/S12889-021-11169-X. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data will not be made publicly available. Researchers interested in accessing the study data can contact the corresponding author for further information.