Abstract

Purpose of Review

This review evaluates the current understanding of the role of ultrasound in the diagnosis and treatment of meniscal disorders.

Recent Findings

Ultrasound (US) demonstrates similar sensitivity and specificity when compared to magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of meniscal injuries when compared to arthroscopy. Meniscal extrusion (ME) under US can be a reliable metric to evaluate for meniscal root tears in knees with and without osteoarthritis (OA). Sonographic ME is associated with development of OA in knees without OA. US following allograft meniscal transplant may be useful in predicting graft failure. US findings can be used to screen for discoid menisci and may demonstrate snapping of a type 3 discoid lateral meniscus. Shear wave elastography for meniscal injuries is in its infancy; however, increased meniscal stiffness may be seen with meniscal degeneration. Perimeniscal corticosteroid injections may provide short term relief from meniscal symptoms, and intrameniscal platelet-rich plasma injections appear to be safe and effective up to three years. Ultrasound-assisted meniscal surgery may increase the safety of all inside repairs near the lateral root and may assist in assessing meniscal reduction following root repair.

Summary

Diagnostic US can demonstrate with high accuracy a variety of meniscal pathologies and can be considered a screening tool. Newer technologies such as shear wave elastography may allow us to evaluate characteristics of meniscal tissue that is not possible on conventional imaging. US-guided (USG) treatment of meniscal injuries is possible and may be preferable to surgery for the initial treatment of degenerative meniscal lesions. USG or US-assisted meniscal surgery is in its infancy.

Keywords: Ultrasonography, Meniscus tears, Discoid meniscus, Meniscus treatment

Introduction

The evaluation of meniscal injuries begins with a clinical history and physical examination and is typically followed by radiographs and a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan [1]. As early as 1986, meniscal injuries were diagnosed on ultrasound (US) and compared to arthroscopic findings [2]. With advances in US technology in the last 38 years, US evaluation of meniscal disorders has broadened from evaluation of tears in isolation to the evaluation of meniscal function, as well as less common meniscal disorders such as discoid menisci, meniscus transplants, and meniscal extrusion (ME).

The meniscal bodies and posterior medial horns are easily visualized, but the anterior horns and posterior lateral horns are more difficult to visualize, if at all. Definitive tear characteristics were not originally identified [2]. It was not 2016 that Bouvard et al. first described utilizing US to guide treatment for meniscal pathology [3].

Here, we aim to review the use of US in the diagnosis and treatment of meniscal disorders.

Discussion

Ultrasound in the Diagnosis of Meniscal Injuries

US evaluation of healthy menisci reveals triangular homogenously hyperechoic structures between the bony cortices of the femur and tibia (Fig. 1). The anterior horn, outer rim of the meniscal body, and the posterior horn can be easily visualized. The deep, intra-articular portion of the meniscus, however, cannot be directly visualized [4]. US is considered a suitable alternative to MRI in the diagnosis of meniscal injuries. Despite easier access, lower cost, and dynamic capabilities, US may be underutilized. Experience and knowledge in musculoskeletal US and adequate technology is necessary for appropriate evaluation of meniscal injuries.

Fig. 1.

A and B Coronal US image (transverse meniscal view) of the normal hyperechoic triangular appearance of the medial (A) and lateral (B) menisci. The medial meniscus is visualized at the level of the anterior aspect of the MCL (A) and the lateral at the level of the popliteal hiatus (B). Top, superficial. Prox, proximal

Meniscus Tears

US findings of abnormal menisci include irregular edge, hypoechoic or anechoic areas within or extending to the surface of the meniscus, displaced fragments, and excessive extrusion [5–7] (Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6).

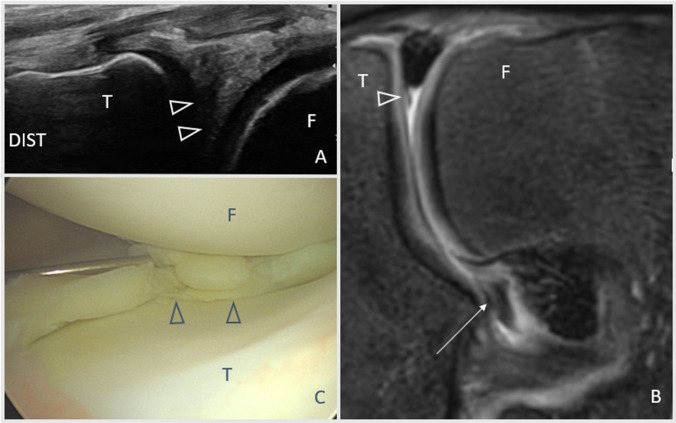

Fig. 2.

Abnormal meniscal ultrasound (US) findings and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)/arthroscopic correlation of a displaced medial meniscus flap tear in a 40-year-old cross fit female athlete. A Axial US image (longitudinal US view of the medial meniscus) in a patient with a displaced flap tear. A hyperechoic line/interface is visualized on the free edge of the medial meniscus indicating the location of the tear and donor site of the displaced fragment of the medial meniscus (open arrowheads). The medial collateral ligament (MCL) is visualized in a transverse view (dotted arrow). B Coronal US image (transverse view of meniscus) of the medial meniscus deep to the MCL (dotted arrow). There is a displaced fragment (dashed arrow) of meniscal tissue in the medial gutter. C Coronal T2 MRI demonstrating similar findings to 2B with a fragment of meniscal tissue (dashed arrow) in the medial meniscal gutter. The blunted medial meniscus free edge noted in (A) is also visualized (open arrow). D and E arthroscopic findings visualized from the anterolateral knee confirming a tear of the free edge medial meniscus (open arrowhead) (D) and after probing the fragment that was displaced beneath the meniscus was brought into the joint and visualized (dashed arrow) (E). T, tibia; F, femur, Dist, distal; Post, posterior; MCL, medial collateral ligament

Fig. 3.

Ultrasound (US), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and arthroscopic findings of a bucket handle medial meniscus tear in a teenage male basketball player. A Coronal US image of the medial joint line (transverse view of meniscus) demonstrating an anechoic region in the undersurface of the medial meniscus (open arrowheads). This was consistent with a meniscus tear and felt to likely be a donor site to a displaced fragment. B Coronal T2 MRI sequence demonstrating a missing meniscal fragment from the medial free edge (open arrowhead) with a displaced fragment of meniscus in the notch (arrow). C Arthroscopic view of the medial meniscus demonstrating the bucket handle fragment reduced along the medial knee (open arrowheads). Dist, distal; T, tibia; F, femur

Fig. 4.

Partial thickness posterior root medial meniscus tear in a 34-year-old Red Bull athlete. A Anatomic sagittal ultrasound (US) image of the posterior horn medial meniscus (transverse view of meniscus). Hyperechoic calcifications (filled arrowheads) and an anechoic defect (arrow) delineate a posterior horn medial meniscus tear. B Anatomic axial US image (longitudinal view of meniscus) of the posterior horn medial meniscus. The meniscal horn is visualized in a long axis view. Hyperechoic calcifications (closed arrowheads) and an anechoic defect (arrows) demonstrate the same tear in (A). T, tibia; F, femur; MG, medial gastrocnemius; SM, semimembranosus; ST, semitendinosus; Post, posterior; Med, medial

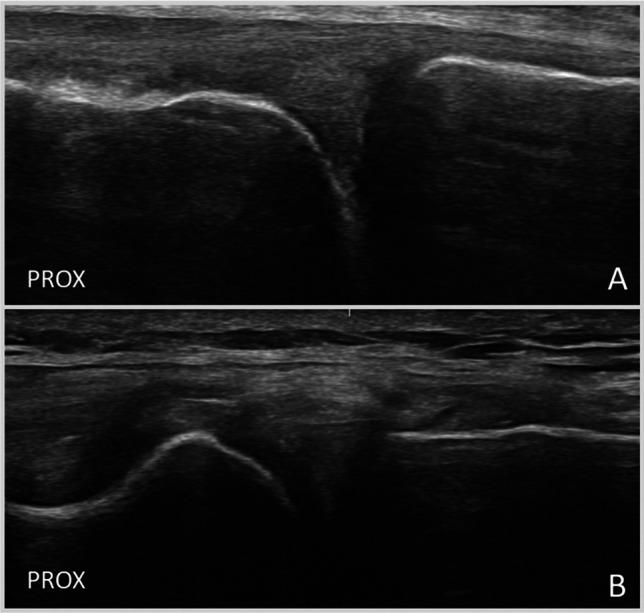

Fig. 5.

Coronal ultrasound image of the lateral meniscus demonstrating a horizontal cleavage tear (arrowheads), which extends from the periphery of the meniscus to the central articular margin. T, tibia; F, femur; Prox, proximal

Fig. 6.

“Dead meniscus sign” in a 45-year-old obese female without osteoarthritis and a posterior root tear. Meniscal extrusion is similar between the supine, NWB position (A) (3.6 mm) and the WB position (B) (3.7 mm). A line is drawn tangental to the bony margins of the tibia (T) and femur (F), and extrusion is measured from that plane to the outer margin of the meniscus. F, femur; T, tibia; NWB, non-weight-bearing; WB, weight-bearing; Med, medial; top, superficial; right, distal

Several studies have evaluated the efficacy of US evaluation in the diagnosis of meniscal injuries. In comparison to MRI or arthroscopy, US demonstrated pooled sensitivities and specificities of 77.5 to 88.8% and 83.8 to 84.6%, respectively [8•, 9•]. Included studies were of high quality with low risk of bias. Moderate to significant heterogeneity among studies existed, likely due to differences in technique and technology. Limited data from two studies demonstrated a moderate inter-observer reliability with the use of US [9•].

Table 1 includes the efficacy of diagnostic US in diagnosing meniscal injuries from individual studies. Several of these studies demonstrate similar or better diagnostic capabilities than MRI when either is compared with arthroscopy [10–13]. Diagnostic capability has been seen to be better for individuals with chronic pain (over 8 weeks) and in those less than 30 years old [7, 12]. Most studies demonstrated greater sensitivity in the US diagnosis of medial meniscal injuries compared to lateral and greater specificity in the diagnosis of lateral meniscal injuries compared to medial [6, 10, 11].

Table 1.

Sensitivity, specificity, positive-predictive value, negative-predictive value, and diagnostic accuracy for US evaluation of meniscal injuries

| Reference | Transducer | Comparison | Sens (%) | Spec (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | Acc (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wasilczyk (2023) [4] | 12 MHz, linear | Arthroscopy | 88 | 86 | NR | NR | 87 |

| Ahmadi (2022) [5] | 12–5 MHz, linear | MRI | MM: 85 | MM:65.7 | MM:58.6 | MM: 88.5 | 72.7 |

| Elshimy (2021) [11] | 9–15 MHz, linear | Arthroscopy |

All: 92.9 MM: 93.8 LM: 90 |

All: 88.9 MM: 96.4 LM: 98 |

All: 95.1 MM: 96.8 LM 98 |

All: 84.2 MM: 93.1 LM: 98 |

All: 91.7 MM: 95 LM: 96.7 |

| Mursean (2017) [10] | 5–13 MHz, linear | Arthroscopy |

MM: 88.8 LM: 70 |

MM: 77.7 LM: 96 |

NR | NR | NR |

| Akatsu (2015) [6] | 6–14 MHz, linear | Arthroscopy |

All: 88 MM: 70 LM: 64 |

All: 85 MM: 95 LM: 79 |

All: 85 MM: 82 LM: 89 |

All: 88 MM: 93 LM: 84 |

NR |

| Cook (2014) [13] | 10–14 MHz linear | Arthroscopy | 91.2 | 84.2 | 94.5 | 76.2 | 89.5% |

|

Timotijevi (2013) [7] |

5 or 7.5 MHz, linear | Arthroscopy |

LM: Acute (< 8 weeks): 71 Chronic: 85 |

LM: Acute: 87 Chronic: 90 |

LM: Acute: 71 Chronic: 85 |

LM: Acute: 87 Chronic: 90 |

NR |

| Alizadeh (2013) [12] | 14 MHz, linear | Arthroscopy |

MM: < 30 yo: 100 > 30 yo: 83.3 |

MM: < 30: 88.9 > 30:71.4 |

MM: < 30: 96.5 > 30:92.6 |

MM: < 30: 100 > 30: 50 |

MM: < 30:97.3 > 30:81.1 |

| Wareluk (2012) | 6–12 MHz, linear | Arthroscopy |

All: 85.4 MM: 93.1 LM: 66.7 |

All: 85.7 MM: 72.5 LM: 95.6 |

All: 67.5 MM: 65.9 LM: 72.7 |

All: 94.4 MM: 94.9 LM: 94.2 |

85.6 |

| Shetty (2008) [14] | 5–13 MHz, linear | Arthroscopy | 86.4 | 69.2 | 82.6 | 75 | 80 |

| Park (2008) [15] | 7.5 to 15 MHz, linear | MRI | 86.2 | 84.9 | 75.8 | 91.8 | 85.4 |

| Sandhu (2007) [16] | 7.5 MHz, linear | Arthroscopy |

Acute (< 8 weeks): 100 Chronic: 100 |

Acute: 33.3 Chronic: 66.6 |

NR | NR | NR |

| Najafi (2006) [17] | 6.5 MHz microconvex | Arthroscopy | All: 100 | All: 95 |

MM: 95 LM: 93 |

MM: 100 LM: 100 |

MM: 98 LM: 97 |

Sens sensitivity, spec specificity, PPV positive-predictive value, NPV negative-predictive value; Acc accuracy, MM medial meniscus, LM lateral meniscus, yo years old

Specific Tear Patterns

Compared to arthroscopy, US demonstrated 100% sensitivity in the diagnosis of horizontal (Fig. 5), radial, flap (Fig. 2), and complex tears with lower sensitivities for vertical and bucket handle (Fig. 3) tears. The greatest specificities were demonstrated in the diagnosis of horizontal (83%) and complex (90%) tears [6]. Direct visualization of root tears is difficult, and surrogate findings of ME are frequently utilized and discussed below (Figs. 4 and 6).

Ramp Lesions

Nakase et al. [18•] described a technique to evaluate for the presence of meniscal ramp lesions, which can be seen with anterior cruciate ligament tears. The patient is placed prone with a sagittal US image of the medial meniscus deep to the semimembranosus tendon. In the presence of a ramp lesion, a hypo- or anechoic space appears between the semimembranosus tendon and medial meniscus with isometric knee flexion. This was termed the “meniscus left behind sign,” because of the lack of an expected posterior shift in conjunction with the semimembranosus tendon with knee flexion [18•].

Meniscal Extrusion

ME is measured with the transducer perpendicular to the joint line, as the distance from the tibial cortex or the tibiofemoral joint line to the peripheral border of the meniscus (Figs. 6 and 7). It is commonly described on MRI (where the patient is static, NWB, and in full extension) but can also be measured with US, which allows for evaluation in different positions [19••, 20, 21]. US measurement of extrusion has been shown to have good interrater and excellent intrarater reliability [22]. After a short training session, ultrasonographers of different levels of experience can measure medial meniscal extrusion (MME) in both healthy and OA knees with good intrarater reliability and interclass reliability [21]. US assessment of extrusion is also reliable when compared to MRI [23].

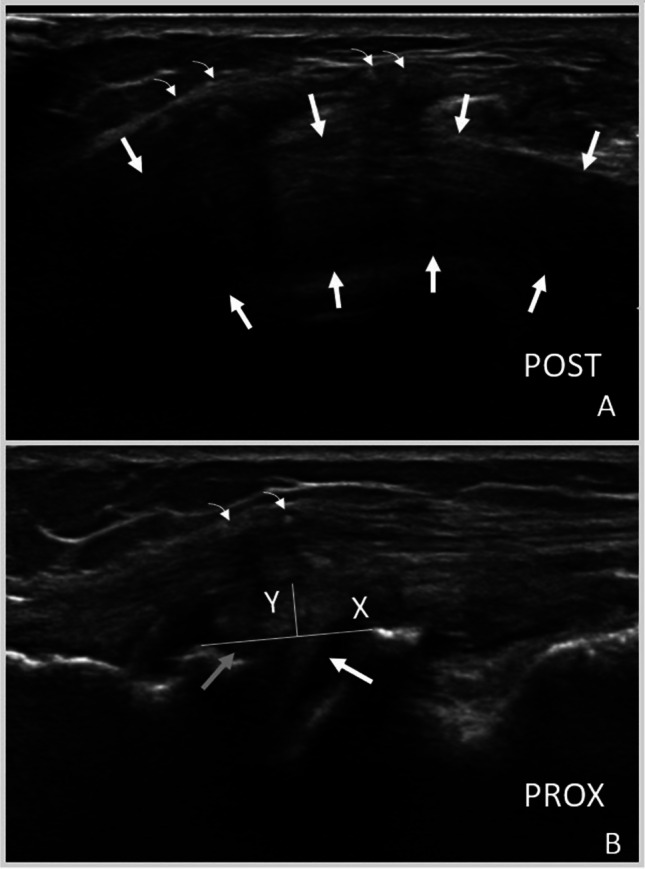

Fig. 7.

Ultrasound (US) images of a lateral meniscus allograft transplant. A Anatomic axial US image (longitudinal view of meniscus) demonstrating uniform echogenicity of meniscus transplant (outlined by arrows). Sutures (curved arrows) are present and result in posterior acoustic shadowing. B Anatomic coronal US image (transverse view of meniscus) demonstrating meniscus (arrows) extrusion (measured by a line joining bony cortices (X) and a perpendicular line to the periphery of the meniscus (Y). Curved arrows indicate sutures superficial which result in posterior acoustic shadowing. Post, posterior; Prox, proximal

ME has been seen in healthy menisci with studies ranging from 0.8 to 2.6 mm in the unloaded and fully extended position and from 1.6 to 2.2 mm in a loaded and fully extended position [20, 22, 24, 25]. Most studies showed an increase in ME with WB, except Winkler et al., which may be due to lower sampling size or technical factors [22]. In healthy individuals, medial menisci extrude more than lateral menisci, and varying degrees of knee flexion can differentially impact anterior and posterior extrusion in the medial and lateral meniscus [25].

Increased ME is non-specific and can be seen with meniscal degeneration and OA, large or complex meniscal tears, or posterior root tears. Greater extrusion in degenerative menisci compared to healthy menisci has been seen in multiple studies [20, 22]. Chiba et al. also demonstrated that extrusion can help predict the risk of OA and the risk of progressive OA due to the increased peak contact pressure [26•]. Individuals without OA and MME over 4 mm had 6.8 times higher 5-year odds ratio of developing OA, and individuals with OA and MME over 4 mm had 6 times higher 5-year odds ratio of developing progressive OA [26•].

Root Tears

Several studies have demonstrated significantly greater ME in the presence of root tears due to the loss of normal circumferential hoop tension [27] (Fig. 6). In patients with early knee OA, medial meniscus posterior root tears (MMPRT) had greater ME in positions of extension, flexion, and full weight-bearing (WB) compared to those without MMPRT [27]. Using extrusion criteria of over 2.55 mm at full extension, over 2 mm at 90° flexion, and over 3.55 mm in WB resulted in sensitivities and specificities of 72–88% and 66–85%, respectively, when compared to MRI [27]. Chiba et al. [28] found slightly greater extrusion measurements to be reliable indicators of MMPRT, with criteria of over 5 mm extrusion in individuals without knee OA and over 7 mm extrusion in individuals with OA. The differences in these studies may be due to lack of standardized protocols of measurement.

In individuals with MMPRT, the change in ME from supine to standing has shown to be significantly less (3.6 to 3.7 mm) compared to normal menisci (1.3 to 2.3 mm) [19••]. This lack of dynamic excursion from non-weight-bearing (NWB) to WB was termed the “dead meniscus sign” and can be seen with MMPRT [19••] (Fig. 6). Another study demonstrated increased ME from supine knee extension to supine figure-four position in those with MMPRT and reduced ME in those with normal or degenerative menisci [29].

Meniscus Allograft

Few studies have investigated the efficacy of US to evaluate meniscal allograft tissue. Meniscal allograft extrusion in individuals fully rehabilitated after surgery was shown to be significantly greater than the contralateral native meniscus, and thus increased ME in these individuals should be expected [30] (Fig. 7). US findings at 6 and 12 months including localized meniscal fluid, WB extrusion of 2 mm or greater compared to the contralateral side, and abnormal echogenicity have been associated with higher likelihood of allograft failure at 20 months [31].

Discoid Lateral Meniscus

Individuals with discoid lateral menisci (DLM) can be asymptomatic or present with symptoms including pain, snapping, and/or instability [32]. Since most patients present in youth, dynamic US in the diagnosis of DLM is growing in interest because of the greater comfortability of US compared to MRI or arthroscopy for children [32].

US findings of a DLM include a non-triangular shape and the presence of heterogeneous central pattern [32, 33]. Yang, S et al. determined three reliable quantitative ultrasonic parameters for the diagnosis of DLM [34]. These parameters include anterior meniscal angle, meniscal body angle, and posterior meniscus angle and, in combination, had a sensitivity of 76.7%, specificity of 98.9%, and accuracy of 87.8% for the diagnosis of DLM when compared to MRI. Interestingly, all discoid menisci in this study were triangular, which contrasts with previously described qualitative criteria [34]. DLM in this study was slender triangles compared to the shorter and stouter triangles of normal menisci [34].

DLM type 3 is a variant that lacks the posterior meniscotibial ligament attachment and thus has increased mobility. Some individuals can experience a snapping sensation, and this dyskinetic motion can be demonstrated on dynamic US evaluation. The type 3 DLM has been visualized extruding into the lateral gutter in knee extension or figure-four positions [35, 36].

Meniscus Ossicle

In the posterior knee, intrameniscal ossicles may prove difficult to assess compared to loose bodies. In one case study, US demonstrated two hyperechoic fragments within the posterior horn of the medial meniscus that did not displace during dynamic knee flexion, unlike loose bodies which tend to displace with knee flexion. Subsequent CT and MRI confirmed the fragments to be meniscal ossicles [37].

Shear Wave Elastography

Shear wave elastography is an emerging US modality that generates shear waves to help determine tissue elasticity or stiffness and may aid in the diagnosis of unhealthy tissues or those at risk of injury [38, 39]. In asymptomatic males and females, elasticity of the lateral meniscus was 30.12 kPa and 28.26 kPa, respectively, and elasticity of the medial meniscus was 37.66 kPa and 34.86 kPa, respectively. Stiffness (greater elasticity) was shown to be greater in medial menisci than lateral menisci and greater in males compared to females [40]. Others found greater stiffness with increased meniscal degeneration as graded on MRI and in menisci with greater histologic degeneration at time of total knee arthroplasty [41, 42]. Gurun et al. demonstrated good to excellent inter- and intraobserver agreement of the two shear wave observers [41]. These results suggest that shear wave elastography can aid in the assessment of meniscal degeneration. More studies, however, are needed to determine its diagnostic utility for meniscal injuries in general.

Ultrasound in the Treatment of Meniscus Injuries

Ultrasound-Guided Procedures

As US has become more prevalent in sports medicine and orthopedic clinics, an increased interest in utilizing US guidance for the treatment of meniscal disorders has followed suit.

A 2018 randomized controlled trial (RCT) compared US-guided (USG) meniscal wall corticosteroid infiltration (CSI) to arthroscopic partial meniscectomy (APM) [3, 43]. USG CSI was demonstrated to be similar in pain and function to APM at 1 year. Wilderman et al. demonstrated that USG perimeniscal CSI on average produced a 70% reduction in pain for 5.68 weeks; however, no comparison group limits this conclusion [44]. Coll et al. demonstrated a similar 67% decrease in VAS at 6 weeks following a parameniscal CSI [45]. Nakase instead injected the MCL bursa with corticosteroid which resulted in a 76% response rate with average VAS decrease of 6.8 ± 1.2 to 1.5 ± 1.7 at 4 weeks post injection [46].

As opposed to meniscal wall, parameniscal and MCL bursa CSI’s, which target predominantly extraarticular structures, USG intrameniscal injections have become popular in the last 7 years (Table 2). Baria et al. described a technique for intrameniscal injections in 2017, which was quickly followed by several clinical studies of intrameniscal injections with PRP or micro fragmented adipose tissue (MFAT) injections [47••] (Fig. 8B). Ricci et al. described a technique for intrameniscal and parameniscal injections of corticosteroid, but no clinical study has followed up this technical report [48]. Significant heterogeneity is noted in these studies; however, a generally positive trend is noted in a variety of patient reported outcomes.

Table 2.

Treatment and outcomes of ultrasound-guided (USG) intrameniscal injections. PRP platelet-rich plasma, OA osteoarthritis, KL Kellgren-Lawrence, MFAT microfragmented adipose tissue, mL, milliliters, PLT, platelet, CaCL2 calcium chloride, KOOS knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score, MRI magnetic resonance imaging, VAS, visual analog scale, NPS numerical pain scale, IKDC international knee documentation committee; MCID minimum clinically important difference, QOL quality of life

| Treatment and tear type | Author | Subjects | Procedure details | PRP characteristics | Outcome measures | Responders (%) | Change in outcome | Follow-up | p value (reported) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Intervention: USG PRP + trephination Control: USG trephination Tear type: Horizontal cleavage tear |

Kaminski 2019 [49] |

72 (42 PRP, 30 control) |

5–10 passes with continuous injection |

120 mL blood draw → 6–8 mL PRP Activation: CaCL2 and thrombin PLT and leukocyte calculated but not reported |

VAS |

MCID: 65 PRP vs 39 control |

3.62 ± 0.07 (2.82–4.43) PRP vs 2.36 ± 0.0.09 (3.86–5.20) control | Median 92 weeks (range 54–157 weeks) | p = 0.027 for mean change, p = 0.046 for MCID responders |

| KOOS symptom subscale |

MCID: 76 PRP vs 48 control |

27.93 ± 0.42 (22.89–32.96) for PRP vs 18.38 ± 0.82 (10.81–25.95) for control | p = 0.016 for mean change p = 0.028 for MCID responders | ||||||

| Arthroscopy free survival | 8% PRP vs 28% control | p = 0.032 | |||||||

|

Intervention: PRP Control: None Tear type: Grade 2 Reicher Posterior horn medial meniscus Ahlback 0–1 |

Özyalvaç 2019 [50] |

23 (8 lost to follow-up) |

18-gauge spinal |

20 mL blood draw to → 4 mL PRP No activation “4.75 × baseline” |

Lysholm score | 71.1 ± 6.9 to 91.9 ± 6.6 | 31.9 months + / − 5.6 (range 19–45) | p < 0.001 | |

| MRI meniscal healing, graded on Reicher scale | 67 |

10: Grade 2 → grade 1 4: Grade 2 → grade 2 1: Grade 2 → grade 3 |

|||||||

|

Intervention: PRP Control: None Tear type: Stoller grade 1 (2), Grade 2 (4) or grade 3(4) without OA |

Guenoun 2020 [51] | 10 |

21- or 25-gauge needle 0.5 mL into meniscus, 1.5 mL into meniscal wall and 2 mL perimeniscal space |

18 mL draw → 4 mL PRP No activation 1.999 billion ± 616 million platelets |

VAS | 57 ± 11.6 → 36.3 ± 31.1 | 6 months | p = 0.18 | |

| KOOS total | 56.6 ± 15.7 → 72.7 ± 18.5 | p = 0.0007 | |||||||

| Return to sport | 100 | ||||||||

| MRI | Stable meniscal tears at 6 months in 7/7 | ||||||||

|

Intervention: PRP Control: None Tear type: Degenerative medial body or posterior horn KL: 0–1 |

DiMatteo 2021 [52] | 12 |

22-gauge needle 3–4 deposits of 0.5–0.8 mL of PRP in meniscus and menisco-capsular junction |

2 mL “ACP” Injection repeated 3 × at 2-week intervals No activation No reported dose |

VAS | 92 | 6.5 ± 2 to 2.5 ± 2.5 | 18 months |

Baseline to 6 months p = 0.003 6 to 12 months p = 0.004 12 to 18 months stable |

| IKDC | 50.1 ± 18 to 81.6 ± 13.9 |

Baseline to 6 months p < 0.001 6 to 12 months p = 0.03 12 to 18 months stable |

|||||||

|

Intervention: MFAT Control: None Tear type: Multiple locations and types OA present in 21/23 knees |

Malanga 2021 [53] |

20 patients (23 knees) |

18-gauge needle or 22-gauge needle Trephination performed as described by Baria et al |

1–2 mL of MFAT in to tear, “the rest” in the joint | NPS | 78.9 met MCID | 5.45 ± 2.2 to 2.21 ± 2.5 | 12 months | p < 0.01 |

| KOOS |

MCID met by: 57.9 for KOOS pain and ADL’s 63.2 for KOOS symptoms 73.7 for KOOS sports/rec and QOL |

All KOOS subscales saw statistically significant benefit | p < 0.01 | ||||||

|

Intervention: PRP Control: None Tear type: Multiple locations Horizontal, radial, or complex |

Sanchez 2023 [54] |

Three injections, every 2 weeks Injection #1 48 mL blood draw → 10–12 mL (dose 2.1 billion-5.2 billion platelets) intrameniscal + intra-articular Injection #2 32 mL blood draw → 8mL PRP (dose 1.7 billion–3.5 billion platelets) intra-articular Injection #3 identical to #1 Activation: CaCl2 |

KOOS |

MCID met by: 69.9 at 6 months 65.2 at 18 months |

All KOOS subscales saw statistically significant benefit | 18 months | p < 0.0001 | ||

| Survival without arthroscopy | 90.3 | Mean survival 54.3 months |

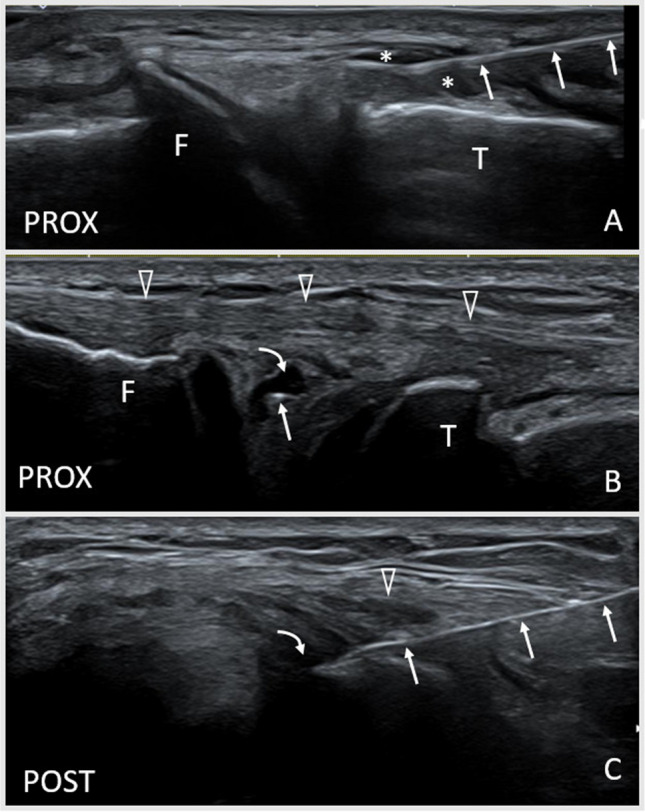

Fig. 8.

Ultrasound (US)-guided interventions involving the menisci. A Coronal US image (transverse to the medial meniscus) demonstrating an in-plane USG injection of the meniscal wall. Anechoic fluid (*) separates the peripheral margin from the overlying fibers of the edge of the medial collateral ligament. The needle (hyperechoic linear structure, arrows) approaches the meniscal wall from caudal (right of image). B Coronal US image (transverse to the lateral meniscus) demonstrating an out-of-plane US-guided intrameniscal injection of platelet-rich plasma in the lateral meniscus. The needle (hyperechoic dot, arrow) approaches from the anterior direction in line with the longitudinal orientation of the meniscus and sits with an anechoic defect in a complex degenerative meniscus tear. The fibular collateral ligament (open arrowheads) lies superficial. C Axial US image (longitudinal to the lateral meniscus) demonstrating an in-plane USG intrameniscal injection of platelet-rich plasma in the lateral meniscus. The needle approaches the anechoic defect in (B) from the anterior. The needle is visualized as a linear hyperechoic structure (arrows) entering from the anterior (right of image) deep to the transverse plane of the fibular collateral ligament (open arrowhead). T, tibia; F, femur; Prox, proximal; Post, posterior

Ultrasound-Assisted Arthroscopic Surgery

In the future, incorporating US into surgical treatment of meniscal pathology may improve the treatment of meniscal pathology.

Ozeki et al. were the first to report a technical note for US assisted all inside meniscal repair surgery [55•]. Using US during an all-inside meniscal repair, the suture may be directed away from the popliteal artery. Direct visualization of the sutures and needle allows confirmation that the suture lies posterior to the lateral meniscus posterior wall to ensure adequate fixation.

Intraoperative US for meniscal surgery, including parameniscal cysts and meniscal root repair, has been reported [56•]. For meniscal root repairs, US was used intraoperatively to establish whether ME was reduced. The repair construct can be tightened or loosened depending on the findings. In the case of parameniscal cysts, US can confirm arthroscopic decompression of the cyst.

Surgeons or their assistants will need to become proficient in identifying these landmarks sonographically if implementing US-assisted surgery. Alternatively, a non-surgeon physician proficient in US may be required to assist with these cases.

Conclusion

US should be considered as a screening tool for meniscal injuries; however, a knowledge of limitations (some regions of limited visualization) and pitfalls (knowledge of US artifacts) are required for responsible and accurate use of US to diagnose meniscal tears. Given the accurate diagnostic performance and accessibility, we feel an appropriate migration towards US being a first line tool to evaluate for some meniscal injuries in the hands of experienced operators. It is our experience, however, that surgeons often request an MRI to better visualize the deeper structures and the cartilage before consideration of arthroscopic meniscal repair.

With recent focus on avoiding APM for degenerative meniscal tears, USG treatment of degenerative meniscal tears appears to be a relatively safe and efficacious treatment option, but further high-quality studies are needed [57–59]. As APM falls out of favor for degenerative meniscal injuries, we hypothesize that intrameniscal injections of orthobiologic agents will have an expanding role in the coming years.

USG or US-assisted meniscal surgery is in its infancy, and further studies are necessary to determine the value it adds to current surgical procedures.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jacob Sellon, MD, for providing US images of an allograft meniscus transplant.

Author Contribution

S.J. and B.B. wrote the main manuscript text. S.J. prepared Table 1, and B.B. prepared Table 2. B.B. prepared the figures. R.K. provided critical appraisal of the work and provided content advice and content editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript, tables, and figures.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Shelby Johnson and Brennan Boettcher declare that they have no conflicts of interest. Ryan Kruse is a consultant for Lipogems SPO, LLC.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

- 1.AAOS. [Available from: https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/diseases--conditions/meniscus-tears/. Accessed 29 Jan 2024.

- 2.Selby B, Richardson ML, Montana MA, Teitz CC, Larson RV, Mack LA. High resolution sonography of the menisci of the knee. Invest Radiol. 1986;21(4):332–335. doi: 10.1097/00004424-198604000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouvard M, Marion C, Parier J. Injections for the treatment of meniscus pain: Usefulness, technique and contribution of ultrasonography. J Traumatol Sport. 2016;33(2):114–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jts.2016.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wasilczyk C. The value of ultrasound diagnostic imaging of meniscal knee injuries verified by experimental and arthroscopic investigations. Diagnostics (Basel) 2023;13(20):3264. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics13203264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmadi O, Motififard M, Heydari F, Golshani K, Azimi Meibody A, Hatami S. Role of point-of-care ultrasonography (POCUS) in the diagnosing of acute medial meniscus injury of knee joint. Ultrasound J. 2022;14(1):7. doi: 10.1186/s13089-021-00256-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akatsu Y, Yamaguchi S, Mukoyama S, Morikawa T, Yamaguchi T, Tsuchiya K, et al. Accuracy of high-resolution ultrasound in the detection of meniscal tears and determination of the visible area of menisci. J Bone Joint Surg - Am Vol. 2015;97(10):799–806. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.01055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Timotijevic S, Vukasinovic Z, Bascarevic Z. Correlation of clinical examination, ultrasound sonography, and magnetic resonance imaging findings with arthroscopic findings in relation to acute and chronic lateral meniscus injuries. J Orthop Sci. 2014;19(1):71–76. doi: 10.1007/s00776-013-0480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dong F, Zhang L, Wang S, Dong D, Xu J, Wu H, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of B-mode ultrasound in detecting meniscal tears: a systematic review and pooled meta-analysis. Med Ultrason. 2018;20(2):164–169. doi: 10.11152/mu-1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xia XP, Chen HL, Zhou B. Ultrasonography for meniscal injuries in knee joint: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2016;56(10):1179–1187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muresan S, Muresan M, Voidazan S, Neagoe R. The accuracy of musculoskeletal ultrasound examination for the exploration of meniscus injuries in athletes. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2017;57(5):589–594. doi: 10.23736/S0022-4707.17.06132-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elshimy A, Osman AM, Awad MES, Abdel Aziz MM. Diagnostic accuracy of point-of-care knee ultrasound for evaluation of meniscus and collateral ligaments pathology in comparison with MRI. Acta Radiol. 2023;64(7):2283–2292. doi: 10.1177/02841851211058280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alizadeh A, Babaei Jandaghi A, Keshavarz Zirak A, Karimi A, Mardani-Kivi M, Rajabzadeh A. Knee sonography as a diagnostic test for medial meniscal tears in young patients. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2013;23(8):927–931. doi: 10.1007/s00590-012-1111-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cook JL, Cook CR, Stannard JP, Vaughn G, Wilson N, Roller BL, et al. MRI versus ultrasonography to assess meniscal abnormalities in acute knees. J Knee Surg. 2014;27(4):319–324. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1367731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shetty AA, Tindall AJ, James KD, Relwani J, Fernando KW. Accuracy of hand-held ultrasound scanning in detecting meniscal tears. J Bone Joint Surg - Bri Vol. 2008;90(8):1045–1048. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B8.20189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park G-Y, Kim J-M, Lee S-M, Lee MY. The value of ultrasonography in the detection of meniscal tears diagnosed by magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;87(1):14–20. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e31815e643a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandhu MS, Dhillon MS, Katariya S, Gopal V, Nagi ON. High resolution sonography for analysis of meniscal injuries. J Indian Med Assoc. 2007;105(1):49–50, 2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Najafi J, Bagheri S, Lahiji FA. The value of sonography with micro convex probes in diagnosing meniscal tears compared with arthroscopy. J Ultrasound Med. 2006;25(5):593–597. doi: 10.7863/jum.2006.25.5.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakase J, Asai K, Yoshimizu R, Kimura M, Tsuchiya H. How to detect meniscal ramp lesions using ultrasound. Arthrosc Tech. 2021;10(6):e1539–e42. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2021.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karpinski K, Diermeier T, Willinger L, Imhoff AB, Achtnich A, Petersen W. No dynamic extrusion of the medial meniscus in ultrasound examination in patients with confirmed root tear lesion. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27(10):3311–3317. doi: 10.1007/s00167-018-5341-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Falkowski AL, Jacobson JA, Cresswell M, Bedi A, Kalia V, Zhang B. Medial meniscal extrusion evaluation with weight-bearing ultrasound: correlation with MR imaging findings and reported symptoms: correlation with MR imaging findings and reported symptoms. J Ultrasound Med. 2022;41(11):2867–2875. doi: 10.1002/jum.15975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reisner JH, Franco JM, Hollman JH, Johnson AC, Sellon JL, Finnoff JT. Ultrasound assessment of weight-bearing and non-weight-bearing meniscal extrusion: a reliability study. Pm & R. 2020;12(1):26–35. doi: 10.1002/pmrj.12183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winkler PW, Csapo R, Wierer G, Hepperger C, Heinzle B, Imhoff AB, et al. Sonographic evaluation of lateral meniscal extrusion: implementation and validation. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2021;141(2):271–281. doi: 10.1007/s00402-020-03683-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nogueira-Barbosa MH, Gregio-Junior E, Lorenzato MM, Guermazi A, Roemer FW, Chagas-Neto FA, et al. Ultrasound assessment of medial meniscal extrusion: a validation study using MRI as reference standard. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;204(3):584–588. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.12522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Achtnich A, Petersen W, Willinger L, Sauter A, Rasper M, Wortler K, et al. Medial meniscus extrusion increases with age and BMI and is depending on different loading conditions. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26(8):2282–2288. doi: 10.1007/s00167-018-4885-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharafat Vaziri A, Aghaghazvini L, Jahangiri S, Tahami M, Borazjani R, Tahmasebi MN, et al. Determination of normal reference values for meniscal extrusion using ultrasonography during the different range of motion: a pilot, feasibility study. J Ultrasound Med. 2022;41(11):2715–2723. doi: 10.1002/jum.15955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chiba D, Sasaki E, Ota S, Maeda S, Sugiyama D, Nakaji S, et al. US detection of medial meniscus extrusion can predict the risk of developing radiographic knee osteoarthritis: a 5-year cohort study. Eur Radiol. 2020;30(7):3996–4004. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-06749-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shimozaki K, Nakase J, Kanayama T, Yanatori Y, Oshima T, Asai K, et al. Ultrasonographic diagnosis of medial meniscus posterior root tear in early knee osteoarthritis: a comparative study. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2023;26:26. doi: 10.1007/s00402-023-05068-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chiba D, Sasaki T, Ishibashi Y. Greater medial meniscus extrusion seen on ultrasonography indicates the risk of MRI-detected complete medial meniscus posterior root tear in a Japanese population with knee pain. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):4756. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-08604-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoshikawa A, Nakamura H, Takei R, Matsumoto R, Saita K. Figure-4 patient positioning increases medial meniscus extrusion on ultrasound in patients with posterior medial meniscus root tears of the knee. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil. 2023;5(6):100818. doi: 10.1016/j.asmr.2023.100818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verdonk P, Depaepe Y, Desmyter S, De Muynck M, Almqvist KF, Verstraete K, et al. Normal and transplanted lateral knee menisci: evaluation of extrusion using magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2004;12(5):411–419. doi: 10.1007/s00167-004-0500-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cook JL, Cook CR, Rucinski K, Stannard JP. Serial ultrasonographic imaging can predict failure after meniscus allograft transplantation. Ultrasound. 2023;31(2):139–146. doi: 10.1177/1742271X221131283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tyler PA, Jain V, Ashraf T, Saifuddin A. Update on imaging of the discoid meniscus. Skeletal Radiol. 2022;51(5):935–956. doi: 10.1007/s00256-021-03910-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Achour NTK, Souei MM, Gamaoun W, Jemni H, Dali KM, Dahmen J, Hmida RB. Discoid menisci in children: ultrasonographic features. J Radiol. 2006;87(1):35–40. doi: 10.1016/s0221-0363(06)73967-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang S-J, Zhang M-Z, Li J, Xue Y, Chen G. A reliable, ultrasound-based method for the diagnosis of discoid lateral meniscus. Arthroscopy. 2021;37(3):882–890. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2020.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jose J, Buller LT, Rivera S, Carvajal Alba JA, Baraga M. Wrisberg-variant discoid lateral meniscus: current concepts, treatment options, and imaging features with emphasis on dynamic ultrasonography. Am J Orthop (Chatham, Nj) 2015;44(3):135–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marchand AJ, Proisy M, Ropars M, Cohen M, Duvauferrier R, Guillin R. Snapping knee: imaging findings with an emphasis on dynamic sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199(1):142–150. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martinoli C, Bianchi S, Spadola L, Garcia J. Multimodality imaging assessment of meniscal ossicle. Skelet Radiol. 2000;29(8):481–484. doi: 10.1007/s002560000235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ryu J, Jeong WK. Current status of musculoskeletal application of shear wave elastography. Ultrasonography. 2017;36(3):185–197. doi: 10.14366/usg.16053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seth I, Hackett LM, Bulloch G, Sathe A, Alphonse S, Murrell GAC. The application of shear wave elastography with ultrasound for rotator cuff tears: a systematic review. JSES Rev Rep Tech. 2023;3(3):336–342. doi: 10.1016/j.xrrt.2023.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ye R, Xiong H, Liu X, Yang J, Guo J, Qiu J. Assessment of knee menisci in healthy adults using shear wave elastography. J Ultrasound Med. 2023;42(12):2859–2866. doi: 10.1002/jum.16326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gurun E, Akdulum I, Akyuz M, Tokgoz N, Ozhan OS. Shear wave elastography evaluation of meniscus degeneration with magnetic resonance imaging correlation. Acad Radiol. 2021;28(10):1383–1388. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2020.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park J-Y, Kim J-K, Cheon J-E, Lee MC, Han H-S. Meniscus stiffness measured with shear wave elastography is correlated with meniscus degeneration. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2020;46(2):297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2019.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marion C, Bouvard M, Lippa A, Gardès P, Lavallé F, et al. Meniscal pain: US guided meniscal wall infiltration versus partial meniscectomy, a comparative study. Int J Sports Exerc Med. 2018;4:086. doi: 10.23937/2469-5718/1510086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilderman I, Berkovich R, Meaney C, Kleiner O, Perelman V. Meniscus-targeted injections for chronic knee pain due to meniscal tears or degenerative fraying: a retrospective study. J Ultrasound Med. 2019;38(11):2853–2859. doi: 10.1002/jum.14987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coll C, Coudreuse JM, Guenoun D, Bensoussan L, Viton JM, Champsaur P, et al. Ultrasound-guided perimeniscal injections: anatomical description and feasibility study. J Ultrasound Med. 2022;41(1):217–224. doi: 10.1002/jum.15700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakase J, Yoshimizu R, Kimura M, Kanayama T, Yanatori Y, Tsuchiya H. Anatomical description and short-term follow up clinical results for ultrasound-guided injection of medial collateral ligament bursa: new conservative treatment option for symptomatic degenerative medial meniscus tear. Knee. 2022;38:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2022.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baria MR, Sellon JL, Lueders D, Smith J. Sonographically guided knee meniscus injections: feasibility, techniques, and validation. Pm & R. 2017;9(10):998–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2016.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ricci V, Ozcakar L, Galletti L, Domenico C, Galletti S. Ultrasound-guided treatment of extrusive medial meniscopathy: a 3-step protocol. J Ultrasound Med. 2020;39(4):805–810. doi: 10.1002/jum.15142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaminski R, Maksymowicz-Wleklik M, Kulinski K, Kozar-Kaminska K, Dabrowska-Thing A, Pomianowski S. Short-term outcomes of percutaneous trephination with a platelet rich plasma intrameniscal injection for the repair of degenerative meniscal lesions. A prospective, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled study. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(4):856. doi: 10.3390/ijms20040856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ozyalvac ON, Tuzuner T, Gurpinar T, Obut A, Acar B, Akman YE. Radiological and functional outcomes of ultrasound-guided PRP injections in intrasubstance meniscal degenerations. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2019;27(2):2309499019852779. doi: 10.1177/2309499019852779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guenoun D, Magalon J, de Torquemada I, Vandeville C, Sabatier F, Champsaur P, et al. Treatment of degenerative meniscal tear with intrameniscal injection of platelets rich plasma. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2020;101(3):169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2019.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Di Matteo B, Altomare D, Garibaldi R, La Porta A, Manca A, Kon E. Ultrasound-guided meniscal injection of autologous growth factors: a brief report. Cartilage. 2021;13(1_suppl):387S–91S. doi: 10.1177/19476035211037390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Malanga GA, Chirichella PS, Hogaboom NS, Capella T. Clinical evaluation of micro-fragmented adipose tissue as a treatment option for patients with meniscus tears with osteoarthritis: a prospective pilot study. Int Orthop. 2021;45(2):473–480. doi: 10.1007/s00264-020-04835-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sanchez M, Jorquera C, Bilbao AM, Garcia S, Beitia M, Espregueira-Mendes J, et al. High survival rate after the combination of intrameniscal and intraarticular infiltrations of platelet-rich plasma as conservative treatment for meniscal lesions. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2023;31(10):4246–4256. doi: 10.1007/s00167-023-07470-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ozeki N, Koga H, Nakamura T, Nakagawa Y, Ohara T, An J-S, et al. Ultrasound-assisted arthroscopic all-inside repair technique for posterior lateral meniscus tear. Arthrosc Tech. 2022;11(5):e929–e935. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2022.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mhaskar VA, Agrahari H, Maheshwari J. Ultrasound guided arthroscopic meniscus surgery. J Ultrasound. 2023;26(2):577–581. doi: 10.1007/s40477-022-00680-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Katz JN, Brophy RH, Chaisson CE, de Chaves L, Cole BJ, Dahm DL, et al. Surgery versus physical therapy for a meniscal tear and osteoarthritis. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(18):1675–1684. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Noorduyn JCA, van de Graaf VA, Willigenburg NW, Scholten-Peeters GGM, Kret EJ, van Dijk RA, et al. Effect of physical therapy vs arthroscopic partial meniscectomy in people with degenerative meniscal tears: five-year follow-up of the ESCAPE randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(7):e2220394. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.20394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sihvonen R, Paavola M, Malmivaara A, Itälä A, Joukainen A, Nurmi H, et al. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy versus sham surgery for a degenerative meniscal tear. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(26):2515–2524. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.