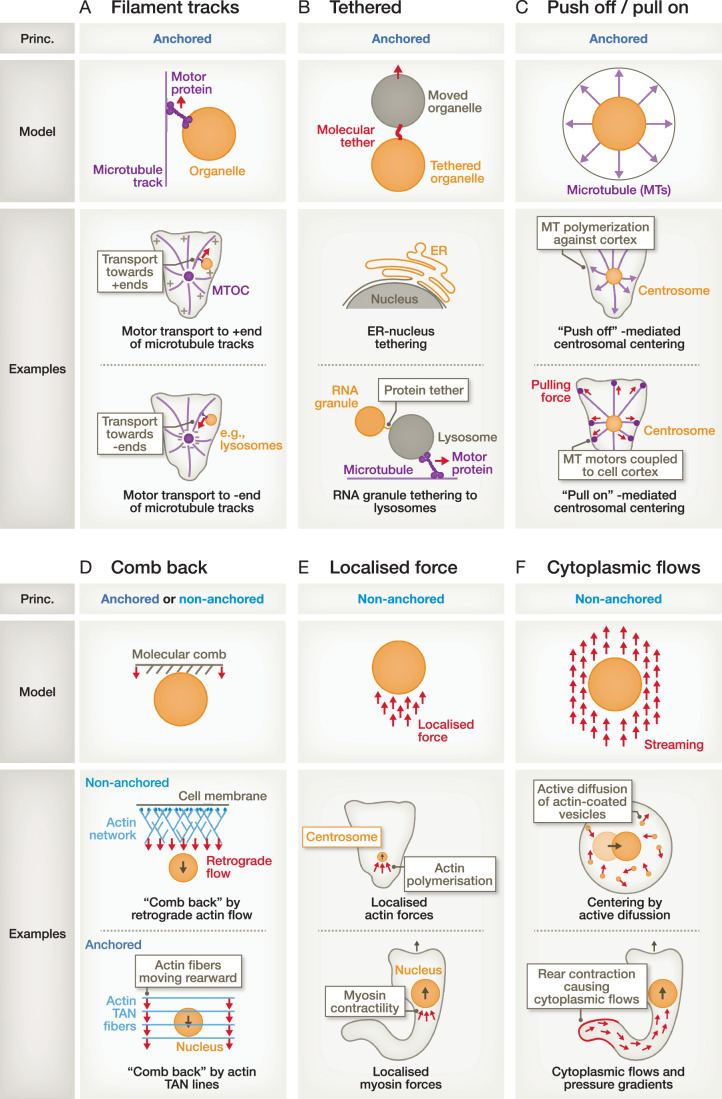

Figure 3. Forces and mechanisms to move and position organelles.

(A) Microtubule filaments provide tracks for motor-based transport of organelles towards the plus- and minus-ends of microtubules. (B) Organelles can be indirectly moved and positioned, when they are directly connected (‘tethered’) to other organelles that move, like in the case of the direct connection between the nucleus and the ER, or by a protein tether connecting RNA granules to the lysosome. (C) Radially growing microtubules (MTs) can serve as a centring structure by pushing their plus ends against the cell cortex and/or by pulling them towards the cell periphery by motors that are coupled to the cell cortex. (D) The actin cytoskeleton can serve as a ‘molecular comb’, combing back intracellular components like organelles. This mechanism is active in fibroblasts that start to migrate in cell-free areas, in which actin fibres (called TAN lines) that are attached to the nucleus via the LINC complex, comb back the nucleus towards the cell rear. Hypothetically, also the rearward-directed retrograde flow of branched actin networks could comb back cellular organelles from the cell front towards the cell body. Notably, such a mechanism would function without directly anchoring the organelles towards the flowing actin network. (E) Similarly, a localised force at the back of an organelle could push the organelle forward without the need for anchoring structures, as it may likely be the case for nuclear positioning by rearward localised myosin activity or centrosome positioning by rearward localised actin polymerisation. (F) Generally, organelles may be moved by advection, using intracellular fluid streaming in an anchorage-independent manner, which may, for example, be caused by the contraction of the cell rear.