Abstract

Background:

This randomized controlled trial aimed to evaluate the efficacy of preoperative inhaled budesonide combined with intravenous dexamethasone on postoperative sore throat (POST) after general anesthesia in patients who underwent thyroidectomy.

Methods:

Patients who underwent elective thyroidectomy were randomly divided into the intravenous dexamethasone group (group A) and budesonide inhalation combined with intravenous dexamethasone group (group B). All patients underwent general anesthesia. The incidence and severity of POST, hoarseness, and cough at 1, 6, 12, and 24 hours after surgery were evaluated and compared between the 2 groups.

Results:

There were 48 and 49 patients in groups A and B, respectively. The incidence of POST was significantly lower at 6, 12, and 24 hours in group B than that in group A (P < .05). In addition, group B had a significantly lower incidence of coughing at 24 hours (P = .047). Compared with group A, the severity of POST was significantly lower at 6 (P = .027), 12 (P = .004), and 24 (P = .005) hours at rest, and at 6 (P = .002), 12 (P = .038), and 24 (P = .015) hours during swallowing in group B. The incidence and severity of hoarseness were comparable at each time-point between the 2 groups (P > .05).

Conclusion:

Preoperative inhaled budesonide combined with intravenous dexamethasone reduced the incidence and severity of POST at 6, 12, and 24 hours after extubation compared with intravenous dexamethasone alone in patients who underwent thyroidectomy. Additionally, this combination decreased the incidence of postoperative coughing at 24 hours.

Keywords: budesonide, dexamethasone, general anesthesia, sore throat, thyroidectomy

1. Introduction

Postoperative sore throat (POST) is a common complication of general anesthesia (GA). Although POST is a minor complication, it reduces patient satisfaction and extends the hospital stay.[1,2] The incidence of POST ranges between 12.1% and 70%, depending on the study.[3] The etiology of POST involves damage to the airway mucosa due to endotracheal intubation under GA.[4] The symptoms of POST include pain, discomfort, hoarseness, and coughing.

Some studies have shown that medications, such as dexamethasone, lidocaine, ketamine, and magnesium, are effective in preventing POST.[5–9] In addition, non-pharmacological methods for preventing POST have been introduced[2,10,11]; however, POST cannot be completely avoided. Furthermore, the incidence of POST after thyroid surgery is higher than that after other surgeries, and is also significantly higher in females.[12] Therefore, an optimal approach for preventing POST during thyroidectomy is worth investigating.

To the best of our knowledge, few studies have focused on a combined approach to prevent POST.[13,14] In the present study, we investigated the effects of the preoperative administration of inhaled budesonide combined with intravenous dexamethasone to reduce POST in patients who underwent thyroidectomy.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and eligibility

This prospective randomized clinical trial was approved by the institutional review board (no. 2023100). Patients who underwent thyroidectomies at the Department of Thyroid and Breast Surgery of the Affiliated People’s Hospital of Ningbo University between October 2023 and January 2024 were enrolled in this study. All patients provided written informed consent to participate in the study after being sufficiently informed. This clinical study was registered at Chictr. org. cn (ChiCTR2300076821). The inclusion criteria were as follows: patients who underwent thyroidectomy under GA, aged 18 to 70 years, and class I to II according to the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification. The exclusion criteria were preoperative sore throat, preoperative hoarseness or cough, recent or recurrent respiratory tract infection, contraindications to budesonide or dexamethasone, pregnant patients, patients receiving corticosteroid medication before admission, and more than one intubation attempt in GA.

Using a computer-generated random number table, the patients were randomly allocated to 2 groups, intravenous dexamethasone (group A) and budesonide inhalation combined with intravenous dexamethasone (group B), at a ratio of 1:1. Patients in group A received an intravenous injection of 0.1 mg/kg dexamethasone mixed with normal saline (5 ml) 30 minutes before anesthetic induction. Patients in group B received an intravenous injection of 0.1 mg/kg dexamethasone mixed with normal saline (5 mL) 30 minutes before anesthetic induction, in addition to budesonide aerosol inhalation for 30 minutes before anesthetic induction. The budesonide suspension (Pulmicort, produced by Astra-Zeneca, Wilmington, DE) specifications were 0.5 mg/2 mL each, which was administered in 10 mL normal saline with an adjusted oxygen flow 3 to 5 L/min for an aerosol inhalation time of 15 to 20 minutes.

2.2. GA procedure

A senior anesthesiologist blinded to the preoperative treatment performed the GA. The patient was placed in a supine neck extension position. Anesthesia was induced using propofol (1.5 mg/kg) and fentanyl (1.5–2.0 μg/kg), and rocuronium (0.6 mg/kg) was administered to achieve neuromuscular blockade. Under the guidance of a laryngoscope (Tuoren Medical Devices Co., Ltd., Henan, China), tracheal intubation was performed using a wire-reinforced tracheal tube with an internal diameter of 7.0 mm (Lily Medical Technology Co., Ltd., Guangdong, China) for all patients. The cuff was manually inflated with air to the clinical endpoint of the loss of an audible leak through a stethoscope placed next to the thyroid cartilage. Anesthesia was maintained with a sevoflurane 2% to 4% end-tidal concentration in an air and oxygen mixture, with intermittent fentanyl and rocuronium administered as required. At the end of the operation, residual neuromuscular block was reversed by pyridostigmine and glycopyrrolate. When the patient was fully awake and able to follow instructions, the endotracheal tube was carefully removed and the oral secretions were gently suctioned.

2.3. Data collection

The demographic characteristics of the patients were collected, including age, sex, body mass index, approach to thyroidectomy, smoking history, ASA status, duration of surgery, duration of anesthesia, and duration of intubation, in the 2 groups. The primary objective was to observe the incidence of POST, hoarseness, and coughing in both groups. The patients were examined for the development of POST after extubation by a senior nurse who was unaware of the group assigned to the patient. A direct questionnaire was provided to the patients to assess their POST.[15] Assessment was performed 1, 6, 12, and 24 hours after extubation in the ward. The secondary objective was to compare the incidence of hoarseness and cough, and the intensity of POST, hoarseness, and cough between the 2 groups. The sore throat was checked at rest and during swallowing. The intensity of POST was assessed using a four-point scale (0–3)[16]: 0, no sore throat; 1, mild sore throat (complaints of sore throat only when asked); 2, moderate sore throat (complaints of sore throat even without asking); and 3, severe sore throat (complaints of sore throat with hoarseness or coughing). Hoarseness was graded on a four-point scale (0–3): 0, no complaint of hoarseness; 1, minimal hoarseness (minimal change in quality of speech, which the patient answered affirmatively only when asked); 2, moderate hoarseness (moderate change in quality of speech, which the patient complained of on his/her own); and 3, severe hoarseness (gross change in the quality of voice perceived by the observer). Cough was evaluated using the same method: 0, no cough at any time since the operation; 1, minimal cough or scratchy throat; 2, moderate cough; and 3, severe cough.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviations and were compared using independent t-tests or the Mann–Whitney U test between the 2 groups. Categorical data were analyzed using the chi-squared test or Fisher exact test. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY), with statistical significance set at P < .05.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline characteristics

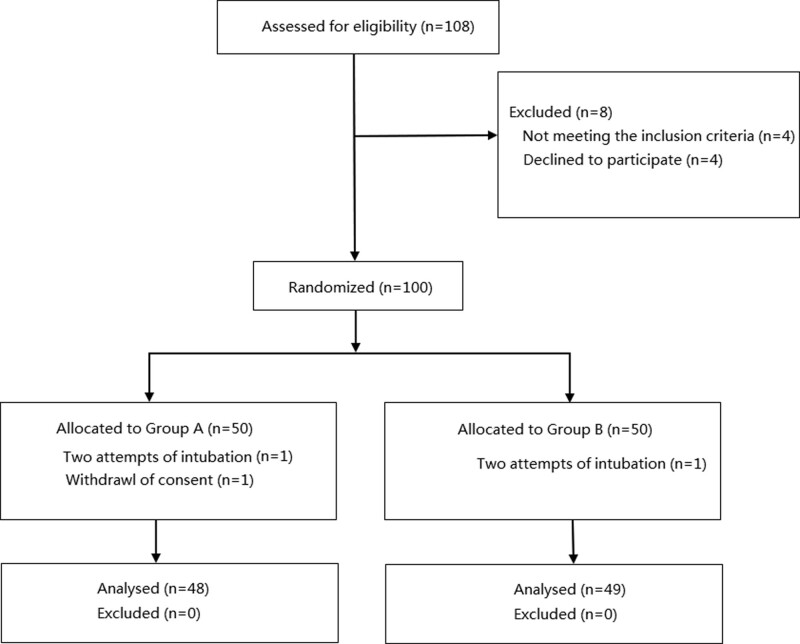

One-hundred-and-eight patients were included in this study. Four patients did not meet the inclusion criteria, and 4 patients declined to participate. The remaining 100 patients were randomized into the 2 groups. Two patients in group A were excluded because of 2 attempts at intubation in 1 patient and withdrawal of consent from the other. One patient in group B was excluded because of 2 attempts at intubation. Thus, 48 and 49 patients in groups A and B, respectively, completed this study (Fig. 1). The 97 patients included 16 males and 81 females, with an average age of 48.5 ± 12.0 years. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients were compared. There were no significant differences between the 2 groups in terms of sex, age, body mass index, type of surgery, surgical approach, postoperative pathology, ASA classification, smoking status, surgical time, anesthesia time, or intubation time (P > .05) (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients compared between the 2 groups.

| Clinical data | Group A (n = 48) | Group B (n = 49) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (n) | .294 | ||

| Male | 6 (12.5%) | 10 (20.4%) | |

| Female | 42 (87.5%) | 39 (79.6%) | |

| Age (years) | 50.0 ± 12.8 | 47.0 ± 11.2 | .232 |

| BMI | 21.8 ± 3.4 | 22.1 ± 3.7 | .691 |

| Type of surgery (n) | .360 | ||

| Lobectomy | 39 (81.3%) | 36 (73.5%) | |

| Total thyroidectomy | 9 (18.8%) | 13 (26.5%) | |

| Approach of surgery (n) | .137 | ||

| Open thyroidectomy | 37 (77.1%) | 31 (63.3%) | |

| Endoscopic thyroidectomy | 11 (22.9%) | 18 (36.7%) | |

| Postoperative pathology (n) | .181 | ||

| Benign | 21 (43.8%) | 15 (30.6%) | |

| Malignant | 27 (56.3%) | 34 (69.4%) | |

| ASA classification (n) | .473 | ||

| I | 40 (83.3%) | 38 (77.6%) | |

| II | 8 (16.7%) | 11 (22.4%) | |

| Smoker (n) | 4 (8.3%) | 10 (20.4%) | .091 |

| Duration (min) | |||

| Surgery | 77.3 ± 20.2 | 74.4 ± 19.8 | .476 |

| Anesthesia | 100.0 ± 18.6 | 94.4 ± 18.9 | .146 |

| Intubation | 94.6 ± 18.3 | 88.4 ± 19.0 | .102 |

ASA = The American Society of Anesthesiologists, BMI = body mass index.

3.2. Incidence of POST, hoarseness, and cough

The incidence of POST at 1 hour was similar between the 2 groups. The incidence of POST at rest was 62.5% and 49.0% at 1 hour in group A and B, respectively (P = .180). The incidence of POST during swallowing was 70.8% and 61.2% at 1 hour in group A and B, respectively (P = .318). In Group B, the incidence of POST notably decreased to 22.4%, 20.4%, and 10.2% at 6, 12, and 24 hours, respectively, which was significantly lower than that at each time-point in group A (P < .05). No significant difference was observed in the incidence of hoarseness between the 2 groups (P > .05). Furthermore, there was no significant difference in the incidence of cough at 1, 6, and 12 hours between the 2 groups (P > .05). However, there was a significantly lower incidence of cough in group B (2.0%) than in group A (12.5%) at 24 hours (P = .047) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Incidence of POST, hoarseness, and cough during the first 24 hours after thyroidectomy.

| Group A (n = 48) | Group B (n = 49) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| POST | |||

| Rest (n) | |||

| 1 hour | 30 (62.5%) | 24 (49.0%) | .180 |

| 6 hours | 26 (54.2%) | 11 (22.4%) | .001 |

| 12 hours | 20 (41.7%) | 10 (20.4%) | .024 |

| 24 hours | 14 (29.2%) | 5 (10.2%) | .019 |

| Swallowing (n) | |||

| 1 hour | 34 (70.8%) | 30 (61.2%) | .318 |

| 6 hours | 28 (58.3%) | 13 (26.5%) | .002 |

| 12 hours | 22 (45.8%) | 13 (26.5%) | .048 |

| 24 hours | 19 (39.6%) | 7 (14.3%) | .005 |

| Hoarseness (n) | |||

| 1 hour | 8 (16.7%) | 7 (14.3%) | .746 |

| 6 hours | 5 (10.4%) | 4 (8.2%) | .702 |

| 12 hours | 4 (8.3%) | 3 (6.1%) | .674 |

| 24 hours | 2 (4.2%) | 1 (2.0%) | .545 |

| Cough (n) | |||

| 1 hour | 10 (20.8%) | 6 (12.2%) | .254 |

| 6 hours | 8 (16.7%) | 4 (8.2%) | .203 |

| 12 hours | 7 (14.6%) | 3 (6.1%) | .171 |

| 24 hours | 6 (12.5%) | 1 (2.0%) | .047 |

POST = postoperative sore throat.

3.3. Severity of POST, hoarseness, and cough

At rest, POST severity was similar at 1 hour (P = .098), but significantly different at 6 hours (P = .027), 12 hours (P = .004), and 24 hours (P = .005). During swallowing, POST severity was similar at 1 hour (P = .599) but significantly different at 6 hours (P = .002), 12 hours (P = .038), and 24 hours (P = .015). There were no significant differences in the severity of hoarseness and coughing at 1, 6, 12, and 24 hours (P > .05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Severity of POST, hoarseness, and cough during the first 24 hours after thyroidectomy.

| Group A (n = 48) | Group B (n = 49) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| POST (0/1/2/3) | |||

| Rest | |||

| 1 hour | 18/3/11/16 | 25/7/10/7 | .098 |

| 6 hours | 22/1/14/11 | 32/5/6/6 | .027 |

| 12 hours | 28/5/7/8 | 39/8/2/0 | .004 |

| 24 hours | 34/3/8/3 | 44/5/0/0 | .005 |

| Swallowing | |||

| 1 hour | 14/6/12/16 | 19/4/14/12 | .599 |

| 6 hours | 20/9/12/7 | 36/3/10/0 | .002 |

| 12 hours | 26/7/9/6 | 36/9/3/1 | .038 |

| 24 hours | 29/4/9/6 | 42/4/2/1 | .015 |

| Hoarseness (0/1/2/3) | |||

| 1 hour | 40/5/2/1 | 42/3/3/1 | .864 |

| 6 hours | 43/3/1/1 | 45/3/1/0 | .793 |

| 12 hours | 44/3/1/0 | 46/2/1/0 | .890 |

| 24 hours | 46/1/1/0 | 48/1/0/0 | .597 |

| Cough (0/1/2/3) | |||

| 1 hour | 38/3/4/3 | 43/3/3/0 | .328 |

| 6 hours | 40/5/1/2 | 45/3/1/0 | .426 |

| 12 hours | 41/4/2/1 | 46/2/1/0 | .517 |

| 24 hours | 42/4/1/1 | 48/1/0/0 | .242 |

Data are presented as number of patients. Severity of sore throat was assessed using 4 graded scale: 0, no sore throat; 1, mild sore throat; 2, moderate sore throat; 3, severe sore throat.

POST = postoperative sore throat.

4. Discussion

POST is defined as discomfort or pain in the patient’s throat during the postoperative recovery period after undergoing GA, and has been reported to cause swallowing difficulty, hoarse voice, and cough.[12] POST is caused by mucosal trauma-induced inflammation; damage occurs in the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, and lower respiratory tract. The risk factors include tracheal intubation, direct laryngoscopy, and excessive endotracheal tube cuff pressure.[17]

Compared to other surgeries, the incidence of POST is higher in patients receiving thyroidectomy after GA, which can be as high as 61.0% to 90.3%; it is a common and undesirable condition.[12,18,19] The potential cause may be the endotracheal tube sliding in the trachea due to a hyperextended neck position, and the manipulation of tissues surrounding the airway intensifies mucosal irritation and inflammation in the trachea.

Prophylactic medications for POST have been suggested to increase the quality of life after GA. Several studies have focused on various pharmacological methods to prevent POST. The anti-inflammatory activity of different medications forms the basis of POST treatment. A combination of drugs with different mechanisms is more effective than the use of a single drug for the prevention of POST.[20] Therefore, an optimal approach is worthy of further investigation.

Dexamethasone is a potent corticosteroid with analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and antiemetic properties. It suppresses the transport of leukocytes to inflammatory sites, inhibits the release of cytokines by maintaining cellular integrity, and induces an anti-inflammatory response by inhibiting fibroblast growth of fibroblasts.[20] The administration of a single dose of intravenous dexamethasone to decrease the incidence of POST has been widely studied.[21–24]

Budesonide is an inhaled topical anti-allergic and anti-inflammatory glucocorticoid used for the maintenance treatment of asthma; it reduces inflammation caused by cytokines, chemokines, enzymes, and cell adhesion molecules.[25] Aerosol inhalation inhibits the activation of macrophages, eosinophils, and neutrophils in the respiratory tract, reduces inflammatory damage in lesions, and facilitates the absorption of mucosal edema.[26]

In patients who underwent thyroidectomy, POST first appeared 1 to 2 hours postoperatively, peaked at 6 to 20 hours, and faded after 24 hours.[18] In our study, the incidence and severity of POST were comparable between the 2 groups 1 hour postoperatively; however, over time, the combined medication group showed an overall reduced incidence and severity of POST than the dexamethasone alone group after 6 hours postoperatively. Intravenous dexamethasone has a rapid onset of action, with effects maintained for 36 to 54 hours. Budesonide has an onset of action within 10 minutes, and peak drug action is reached in approximately 3 hours, with a single dose lasting up to 12 hours. Budesonide did not reach its maximum effect in the early postoperative period, especially within 1 hour after thyroidectomy. Therefore, the combined medication was not superior to single-use dexamethasone. Our study revealed a lower occurrence and severity of POST in the middle and late postoperative periods (6–24 hours) than in the early postoperative period (1 hour). Both the incidence and severity decreased more rapidly than in previous studies.[18,19]

Our study did not show that this combination was more effective than dexamethasone alone in preventing postoperative hoarseness; however, it was useful in reducing the incidence of cough at 24 hours postoperatively, although it did not reduce the overall severity of postoperative cough compared with the single-drug method. Cough frequently causes post-thyroidectomy bleeding because it lifts the thyroid cartilage, loosens the ligation, and increases venous pressure.[27,28] Therefore, reducing coughing decreased the occurrence of postoperative bleeding in patients after thyroidectomy.[29]

Prolonged intubation can cause serious POST. Other factors can also affect the occurrence of POST, such as the size of the endotracheal tube and cuff pressure, intubation attempts, and surgical sites.[30,31] Movement of the head or neck during surgery may cause POST because it causes movement of the endotracheal tube, which aggravates the acute inflammatory response. Kim et al[11] suggested that the smaller the diameter of the tube, the lower the incidence of sore throat. In this study, some of the aforementioned contributing factors were controlled. All patients were placed in the supine neck extension position with head-positioning cushions before GA was administered to decrease head or neck movement during anesthesia and surgery. Second, we used a 7.0 mm endotracheal tube instead of a 6.5 mm one because the smaller the endotracheal tube, the higher the cuff pressure needed to position the endotracheal tube, which increases the incidence of tracheal epithelial damage. Third, patients who underwent more than one intubation attempt were excluded from the study.

In our study, hyperglycemia was observed with the preoperative use of a single dose of dexamethasone; however, it was not associated with any risk of delayed wound healing or infection, and the side effects seemed to be negligible. Furthermore, the combination therapy group did not show an increased incidence of adverse effects.

The main strength of this study is that it is the first to observe the efficacy of preoperative inhaled budesonide combined with intravenous dexamethasone for POST in patients who underwent thyroidectomy. The potential role of inhaled topical steroids in the inflammation of the postoperative airway sequelae caused by GA has been recognized.

However, this study has several limitations. First, there was no control group. Based on the previous literature, we assume that preoperative intravenous dexamethasone reduces POST; thus, in our view, it is unethical to establish a control group knowing that the incidence of POST increases without any intervention. Second, the effect of inhaled budesonide on POST prevention without intravenous dexamethasone was not investigated. Third, objective assessments of sore throat, hoarseness, and coughing were lacking. Fourth, the cuff pressure in the endotracheal tube could not be measured.

5. Conclusions

Preoperative inhaled budesonide combined with intravenous dexamethasone resulted in the reduced occurrence and severity of POST at 6, 12, and 24 hours after extubation compared to intravenous dexamethasone alone in patients who underwent thyroidectomy. This combination significantly reduced the incidence of postoperative coughing at 24 hours.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients and employees of the Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, Thyroid and Breast Surgery, and Anesthesiology, the Affiliated People’s Hospital of Ningbo University, Ningbo, Zhejiang, China.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Ping-Ping Chen.

Data curation: Ping-Ping Chen, Xing Zhang, Dan Chen.

Formal analysis: Hui Ye.

Investigation: Ping-Ping Chen, Hui Ye, Dan Chen.

Methodology: Hui Ye.

Project administration: Ping-Ping Chen.

Software: Ping-Ping Chen.

Supervision: Xing Zhang.

Writing – original draft: Xing Zhang

Writing – review & editing: Xing Zhang.

Abbreviations:

- ASA

- American Society of Anesthesiologists

- GA

- general anesthesia

- POST

- postoperative sore throat

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

How to cite this article: Chen P-P, Zhang X, Ye H, Chen D. Effects of preoperative inhaled budesonide combined with intravenous dexamethasone on postoperative sore throat in patients who underwent thyroidectomy: A randomized controlled trial. Medicine 2024;103:20(e38235).

Contributor Information

Ping-Ping Chen, Email: chendan4848@126.com.

Hui Ye, Email: yehui0831@126.com.

Dan Chen, Email: chendan4848@126.com.

References

- [1].Jiang J, Wang Z, Xu Q, Chen Q, Lu W. Development of a nomogram for prediction of postoperative sore throat in patients under general anaesthesia: a single-centre, prospective, observational study. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e059084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Jau PY, Chang SC. The effectiveness of acupuncture point stimulation for the prevention of postoperative sore throat: a meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e29653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Mitobe Y, Yamaguchi Y, Baba Y, et al. A literature review of factors related to postoperative sore throat. J Clin Med Res. 2022;14:88–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Zheng ZP, Tang SL, Fu SL, et al. Identifying the risk factors for postoperative sore throat after endotracheal intubation for oral and maxillofacial surgery. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2023;19:163–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kuriyama A, Maeda H, Sun R. Aerosolized corticosteroids to prevent postoperative sore throat in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2019;63:282–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Subedi A, Tripathi M, Pokharel K, Khatiwada S. Effect of intravenous lidocaine, dexamethasone, and their combination on postoperative sore throat: a randomized controlled trial. Anesth Analg. 2019;129:220–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kuriyama A, Nakanishi M, Kamei J, Sun R, Ninomiya K, Hino M. Topical application of ketamine to prevent postoperative sore throat in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2020;64:579–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kuriyama A, Maeda H, Sun R. Topical application of magnesium to prevent intubation-related sore throat in adult surgical patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Anaesth. 2019;66:1082–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Dhahri AA, Ahmad R, Rao A, et al. Use of prophylactic steroids to prevent hypocalcemia and voice dysfunction in patients undergoing thyroidectomy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;147:866–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kim H, Kim JE, Kim Y, Hong SW, Jung H. Slow advancement of the endotracheal tube during fiberoptic-guided tracheal intubation reduces the severity of postoperative sore throat. Sci Rep. 2023;13:7709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kim H, Kim JE, Yang WS, Hong SW, Jung H. Effects of bevel direction of endotracheal tube on the postoperative sore throat when performing fiberoptic-guided tracheal intubation: a randomized controlled trial. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e30372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Jung TH, Rho JH, Hwang JH, Lee J-H, Cha S-C, Woo SC. The effect of the humidifier on sore throat and cough after thyroidectomy. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2011;61:470–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lee J, Park HP, Jeong MH, Kim H-C. Combined intraoperative paracetamol and preoperative dexamethasone reduces postoperative sore throat: a prospective randomized study. J Anesth. 2017;31:869–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Niu J, Hu R, Yang N, et al. Effect of intratracheal dexmedetomidine combined with ropivacaine on postoperative sore throat: a prospective randomised double-blinded controlled trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2022;22:144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Harding CJ, McVey FK. Interview method affects incidence of postoperative sore throat. Anaesthesia. 1987;42:1104–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Thomas D, Chacko L, Raphael PO. Dexmedetomidine nebulisation attenuates post-operative sore throat in patients undergoing thyroidectomy: a randomised, double-blind, comparative study with nebulised ketamine. Indian J Anaesth. 2020;64:863–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].El-Boghdadly K, Bailey CR, Wiles MD. Postoperative sore throat: a systematic review. Anaesthesia. 2016;71:706–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Yang C, Jung SM, Bae YK, Park S-J. The effect of ketorolac and dexamethasone on the incidence of sore throat in women after thyroidectomy: a prospective double-blinded randomized trial. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2017;70:64–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ryu JH, Yom CK, Park DJ, et al. Prospective randomized controlled trial on the use of flexible reinforced laryngeal mask airway (LMA) during total thyroidectomy: effects on postoperative laryngopharyngeal symptoms. World J Surg. 2014;38:378–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ki S, Myoung I, Cheong S, et al. Effect of dexamethasone gargle, intravenous dexamethasone, and their combination on postoperative sore throat: a randomized controlled trial. Anesth Pain Med (Seoul). 2020;15:441–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Jiang Y, Chen R, Xu S, et al. The impact of prophylactic dexamethasone on postoperative sore throat: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain Res. 2018;11:2463–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kuriyama A, Maeda H. Preoperative intravenous dexamethasone prevents tracheal intubation-related sore throat in adult surgical patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Anaesth. 2019;66:562–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Zhao X, Cao X, Li Q. Dexamethasone for the prevention of postoperative sore throat: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Anesth. 2015;27:45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Bagchi D, Mandal MC, Das S, Sahoo T, Basu SR, Sarkar S. Efficacy of intravenous dexamethasone to reduce incidence of postoperative sore throat: a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2012;28:477–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hübner M, Hochhaus G, Derendorf H. Comparative pharmacology, bioavailability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of inhaled glucocorticosteroids. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2005;25:469–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Zhao Y, Jiang C, Wu Q, Shi R. Effects of endoscopic sinus surgery combined with budesonide treatment on nasal cavity function and serum inflammatory factors in patients with chronic sinusitis. J Healthc Eng. 2022;2022:4140682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- [27].Chen E, Cai Y, Li Q, et al. Risk factors target in patients with post-thyroidectomy bleeding. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7:1837–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Rosenbaum MA, Haridas M, McHenry CR. Life-threatening neck hematoma complicating thyroid and parathyroid surgery. Am J Surg. 2008;195:339–43; discussion 343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kim SH, Kim YS, Kim S, Jung KT. Dexmedetomidine decreased the post-thyroidectomy bleeding by reducing cough and emergence agitation - a randomized, double-blind, controlled study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2021;21:113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Fayyaz A, Furqan A, Ammar A, Akhtar R. Comparing the effectiveness of Betamethasone Gel with Lidocaine Gel local application on endotracheal tube in preventing post-operative sore throat (POST). J Pak Med Assoc. 2017;67:873–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].McHardy FE, Chung F. Postoperative sore throat: cause, prevention and treatment. Anaesthesia. 1999;54:444–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]