Abstract

Background & Aims

The intestinal rehabilitation program (IRP) is a specialized approach to managing patients with intestinal failure (IF). The goal of IRP is to reduce the patient’s dependence on parenteral nutrition by optimizing nutrition intake while minimizing the risk of complications and providing individualized medical and surgical treatment. We aimed to provide a thorough overview of our extensive history in adult IRP.

Methods

We reviewed the medical records of adults with IF treated at our center’s IRP over the past two decades. We collected data on demographic and clinical results, such as the causes of IF, the current status of the remaining bowel, nutritional support, and complications or mortality related to IF or prolonged parenteral nutrition.

Results

We analyzed a total of 47 adult patients with a median follow-up of 6.7 years. The most common cause of IF was massive bowel resection due to mesenteric vessel thrombosis (38.3%). Twenty-eight patients underwent rehabilitative surgery, including 12 intestinal transplants. The 5-year survival rate was 81.9% with 13 patients who expired due to sepsis, liver failure, or complication after transplantation. Of the remaining 34 patients, 18 were successfully weaned off from parenteral nutrition.

Conclusion

Our results of IRP over two decades suggest that the individualized and multidisciplinary program for adult IF is a promising approach for improving patient outcomes and achieving nutritional autonomy.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10620-024-08285-0.

Keywords: Intestinal failure, Intestinal rehabilitation program, Nutrition therapy, Nutrition support, Short bowel syndrome

Introduction

Intestinal failure (IF) is a condition where the gut function is reduced below the minimum amount necessary for adequate digestion and absorption of food and/or requires the use of parenteral support to maintain water and electrolyte balance [1, 2]. The most common causes are short bowel syndrome, accounting for about 75% of adults in Europe [1, 3]. Other significant pathophysiological causes include intestinal fistula, intestinal dysmotility, mechanical obstruction, and extensive small bowel mucosal disease [4].

IF is a rare, potentially life-threatening, and debilitating condition requiring both acute and chronic medical management with appropriate surgical intervention [5, 6]. Moreover, patients have heterogeneous characteristics such as variable causes of disease, differences in length of remaining bowel, anatomic montage, and health of the remnant intestine. For these reasons, individual differences in disease treatment vary, making it difficult to standardize treatment methods and posing a challenge for both patients and healthcare providers [7].

In recent years, hospitals with expertise in complex surgical procedures, nutritional support, and solid organ transplantation programs have been developing individualized treatment plans and multidisciplinary approaches to address the challenges of managing IF [2, 8–10]. These programs, known as intestinal rehabilitation programs (IRP), have been established at multiple sites across North America, Europe, and only a few in Asia [2, 5, 7, 9, 11]. However, most rehabilitation programs and studies are mainly focused on pediatric patients and the literature supporting multidisciplinary management for patients who develop IF as an adults are limited [12].

In this study, we analyze the clinical and rehabilitation results of IRP for adult onset IF, the current state-of-the-art care. We aim to present comprehensive summary of our center’s long-term experience of IRP for the adults IF.

Materials and Methods

Patient Enrollment

A retrospective study of medical chart reviews was conducted from January 2000 to December 2021 at a tertiary hospital specializing in intestinal rehabilitation and solid organ transplantation. Data were obtained from the electronic medical records, operative reports, and nursing charts. Patients who participated in IRP for at least two months were eligible for enrollment. Patients were excluded if they (1) were under 18 years of age, (2) participated for less than two months, (3) were lost during follow-up, or (4) had insufficient data for clinical analysis.

Data Collection

The collected data included patient demographics and nutritional support statuses, such as the cause of IF, body weight, body mass index, duration of PN, and biochemical markers of liver function during follow-up. Additionally, data on all surgical procedures and any complication or mortality related to intestinal failure and long-term PN were recorded. Gastrointestinal anatomy, including the length of the remaining small bowel and colon, was measured using information from surgical records or radiological studies. If the large intestine remained, the length of the colon was described according to the method of Cummings et al. [13].

Type of IF was classified according to the Pironi et al. [1]: type I is an acute, short-term, and self-limiting condition; type II is a prolonged acute condition, typically metabolically unstable and lasting for weeks or months; and type III is for metabolically stable patients with need for long-term PN. Patients who remained off PN for 12 months were considered to have achieved nutritional autonomy.

For the complication related to long-term PN, intestinal failure-associated liver disease (IFALD) was diagnosed when direct bilirubin measured at intervals of at least one week was higher than 2.0 mg/dL on two or more consecutive occasions. The definition of catheter-related bloodstream infection (CRBSI) was diagnosed when individuals with a central venous catheter were placed for a minimum of 48 h and laboratory confirmation of bloodstream infection, following the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s guidelines.

Intestinal Rehabilitation Program

To provide comprehensive care, we established a multidisciplinary team comprising surgeons, gastroenterologists, psychologists, financial counselors, pharmacists, nurses, and nutritionists. Upon admission of a patient with intestinal failure (IF), our multidisciplinary evaluation process begins with the nutrition team conducting a thorough assessment of the patient’s nutritional status. We evaluates the patient’s nutritional status by determining the required calorie intake, fluids needs, available feeding route, and amounts. Additionally, each patient undergoes a thorough evaluation of their disease status, physical condition, and psychological assessment as well.

The surgical team reviews the patient’s surgical history, identifies the remaining bowel length through medical records, and performs an imaging test if necessary. We secure a central venous catheter for intravenous nutrition after investigating the patient’s line history, and if needed, a central venous catheter or peripherally inserted central catheter is inserted. While gastroenterologist performs a follow-up endoscopy to observe the condition of the remaining intestine more closely. The pharmacist establishes an intravenous feeding plan for caloric deficits that cannot be met by enteral feeding. Based on the initial evaluation, we developed an individualized PN plan. This process is done through hospitalization, during which the nursing department provides education on line management and stoma management if patients have a stoma. All education is provided to both patients and their guardians.

After the patient’s condition is stabilized, follow-up management is conducted at the outpatient clinic every 2 to 4 weeks. Specifically, we run a specialized outpatient clinic exclusively dedicated to IF patients, allowing us to provide sufficient time for counseling and examinations to each patient. During outpatient visits, blood tests, weight measurements, physical observations, and prescription modifications are performed. We prescribed glutamine to patients as needed, but growth hormone or GLP-2 analog was not included in our standard protocol. Additionally, through the home nursing care, the nursing department periodically visits patients’ homes to check health condition, identify side effects, and provide necessary medical care.

Separately, the IRP team holds a regular meetings once a week to discuss patient management and address any difficulties. In advance of these meetings, the nutrition team conducts phone interviews with patients to identify changes in weight, dietary patterns, and any complications related to intravenous nutrition treatment. Through these meetings, we develop individually tailored cyclic PN adaptation and treatment plan for any complications or psychosocial issues.

If patients remained stable, we initiated the weaning process until cessation of PN. Achieving autonomy was defined as remaining off PN for 12 months. Surgical treatment was performed if necessary, including the restoration of bowel continuity, autologous intestinal reconstruction, reconstruction such as serial transverse enteroplasty (STEP), or intestinal transplantation. The decision to undergo surgery was made by the multidisciplinary team meeting, taking into account the patient’s pre-existing health conditions, surgical risks, and the patient’s decision.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS statistical package software (version 24.0 for Windows; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). Categorical variables were calculated using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), and the overall differences were assessed by Student’s t test. Variables were tested for normal distribution using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, and in the case of variables that were not normally distributed, the Mann–Whitney test was used. Factors associated with survival were analyzed using the Cox proportional hazards regression method with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Kaplan–Meier method was used to assess survival rates. Additionally, the relative risk of IFALD and CRBSI was calculated by Poisson regression. A p-value of 0.05 or lower was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

A total of 51 adult patients were enrolled in IRP from January 2000 to December 2021. We analyzed the treatment results of a total of 47 patients, excluding 4 patients who were lost during follow-up. The median follow-up time was 6.7 years, and the total observation time was 342.2 patient-years. Of the 47 patients, 25 (53.2%) were male and the average age at the time of referral for the IRP was 47.4 ± 19.7 years. The average length of the remaining small bowel was 47.1 ± 35.6 cm. The most common cause of IF was mesenteric vessel thrombosis (18 cases, 38%), followed by adhesive ileus (9 cases, 19%) and tumor (6 cases, 13%). (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients who enrolled to the intestinal rehabilitation program at the time of initiation

| Characteristics | Total (n = 47) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 47.4 ± 19.7 |

| Gender (male, %) | 25 (53.2) |

| Body mass index (kg/m−2) | 18.9 ± 3.2 |

| Presence of comorbidity (%) | 26 (55.3) |

| Presence of enterostomy (%) | 27 (57.4) |

| Presence of ileocolic valve (%) | 14 (29.8) |

| Remaining small bowel (cm) | 47.1 ± 35.6 |

| Remaining large bowel (%) | 60.5 ± 34.0 |

| Total calories need (kcal) | 1805.7 ± 267.3 |

| Parenteral nutrition/total calorie needs (%) | 69.0 ± 22.0 |

| Preceding disease of intestinal failure (%) | |

| Mesenteric vessel thrombosis | 18 (38.3) |

| Adhesive ileus | 9 (19.1) |

| Malignancy | 6 (12.8) |

| Volvulus or Strangulation | 5 (10.6) |

| Abdominal trauma | 5 (10.6) |

| Othersa | 4 (8.5) |

aOthers: abdominal tuberculosis, lymphangiectasis, pseudo-obstruction, ulcerative colitis

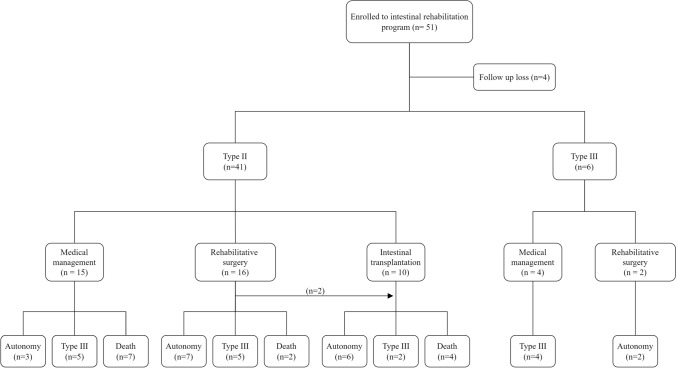

Figure 1 shows a diagram of the patient’s state at the initiation of IRP and subsequent management outcome. At the time of referral, 41 patients were classified as Type II IF, while six patients were classified as Type III. At the time of the last follow-up, 18 patients (38.3%) weaned off from PN and achieved nutritional autonomy.

Fig. 1.

Diagram of patients and management outcomes of intestinal rehabilitation program

During the rehabilitation, 28 patients underwent a total of 39 surgical treatments, including small intestine transplantation (12 cases), STEP (9 cases), and/or ostomy repair (18 cases). The average duration of PN was 39.7 ± 46.6 months. As a complication of prolonged PN, central line sepsis occurred in 25 (53.2%) patients, with a frequency of occurrence of 1.8 times per person. (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of the intestinal rehabilitation program

| Variables | Total (n = 47) |

|---|---|

| Alive | |

| Weaned off PN (%) | 18 (38.3) |

| Home PN or PN on hospitals (%) | 16 (34.0) |

| Dead (%) | 13 (27.7) |

| Restoration of continuity (cases) | |

| Gastrostomy repair | 1 |

| Duodenostomy repair | 2 |

| Jejunostomy repair | 14 |

| Ileostomy repair | 1 |

| Lengthening procedures (cases) | |

| STEP | 9 |

| Intestinal transplantation (cases) | 12 |

| Duration of parenteral nutrition (months) | 39.8 ± 46.6 |

| CRBSI (%) | 25 (53.2) |

| Frequency of CRBSI (cases per person) | 1.8 ± 2.7 |

| IFALD (%) | 5 (10.9) |

One patient may have undergone multiple surgeries

IFALD intestinal failure-associated liver disease, CRBSI catheter-related bloodstream infection, PN parenteral nutrition, STEP serial transverse enteroplasty procedure

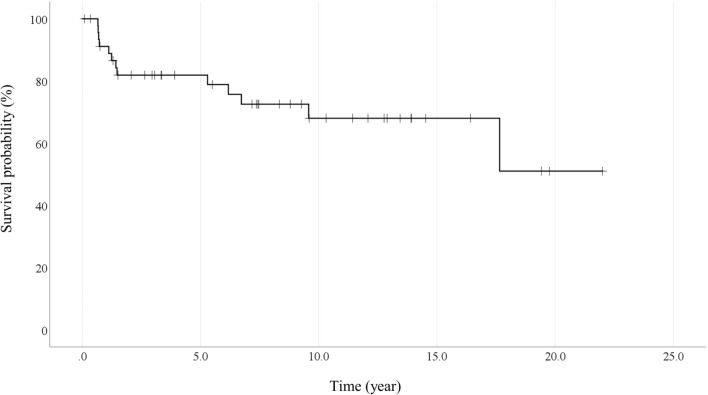

A total of 13 patients expired during the observation period, including two acute rejection after intestinal transplantation. Other causes of death were sepsis (7 cases) and IFALD (4 cases). The estimated overall 5- and 10-year survival rate was 81.9% and 68.0%, respectively. (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Patient survival curve by Kaplan–Meier curve. The probability of 5- and 10-year survival rates are 81.9% and 68.0%, respectively

Weaning off PN was the only factor significantly associated with survival (hazard ratio 0.066, CI 0.008–0.564, p = 0.013) in the regression model. Other factors did not show any significant association on survival in our study. (Table 3) Regarding weaning off PN, the shorter duration of PN showed a significant influence with an odds ratio (OR) of 0.978 (CI 0.957–0.998, p = 0.035) and patients who underwent lengthening surgery showed an OR of 6.731 (CI 1.219–37.155, p = 0.029) (Table S1).

Table 3.

Factors associated with overall survival in intestinal failure patients enrolled in the rehabilitation programs

| Variables | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis of intestinal failure | 1.012 | 0.979–1.046 | 0.484 |

| Comorbidity | 1.422 | 0.386–5.243 | 0.597 |

| Initial presence of ileocolic valve | 1.067 | 0.266–4.281 | 0.927 |

| Initial presence of enterostomy | 0.817 | 0.226–2.957 | 0.758 |

| Lengthening surgery | 1.426 | 0.255–7.969 | 0.686 |

| Intestinal transplantation | 1.444 | 0.349–5.973 | 0.612 |

| PN status (wean off) | 0.066 | 0.008–0.564 | 0.013 |

| Frequency of central line sepsis | 1.086 | 0.863–1.367 | 0.480 |

| IFALD | 1.879 | 0.276–12.775 | 0.519 |

95% CI 95% confidence interval, IFALD intestinal failure-associated liver disease, PN parenteral nutrition

Table 4 presents a comparison of the characteristics between patients who are PN-dependent and those who weaned off from PN (autonomy) at the time of last follow-up. None in the PN-dependent group, while seven (39%) patients in the weaned-off group underwent STEP surgery. Among the observed factors, the number of patients who underwent STEP surgery and the duration of total parenteral nutrition showed differences between the two groups.

Table 4.

Comparison of characteristics of PN-dependent and weaned-off-PN patients at last follow-up

| Characteristics | PN-dependent (n = 16) | Weaned off PN (n = 18) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 47.8 ± 17.7 | 44.7 ± 18.3 | 0.628 |

| Gender (male, %) | 8 (50) | 11 (61.1) | 0.515 |

| Body mass index at initial assessment (kg/m−2) | 18.7 ± 2.8 | 19.4 ± 3.5 | 0.551 |

| Body mass index at last follow-up (kg/m−2) | 19.8 ± 2.1 | 19.9 ± 3.4 | 0.924 |

| Comorbidities (%) | 11 (68.8) | 7 (38.8) | 0.082 |

| Diagnosis to transfer (mean ± SD, months) | 8.4 ± 20.6 | 20.8 ± 47.6 | 0.341 |

| Initial presence of | |||

| Enterostomy (%) | 9 (56.3) | 11 (61.1) | 0.774 |

| Ileocolic valve (%) | 4 (25.0) | 6 (33.3) | 0.595 |

| Remaining small bowel (mean ± SD, cm) | 42.9 ± 40.9 | 47.1 ± 27.7 | 0.734 |

| Remaining large bowel (mean ± SD, %) | 60.3 ± 28.5 | 69.6 ± 35.0 | 0.403 |

| TCN (kcal) | 1812.5 ± 287.2 | 1861.1 ± 263.8 | 0.610 |

| PN/TCN (%) | 73.5 ± 22.3 | 66.3 ± 21.2 | 0.345 |

| PN/TCN at last follow-up (%) | 45.8 ± 23.1 | 0 | < 0.001 |

| Ostomy repair (%) | 7 (43.8) | 8 (44.4) | 0.968 |

| Lengthening surgery (%) | 0 (0) | 7 (38.8) | 0.005 |

| Duration of TPN (mean ± SD, months) | 53.9 ± 47.7 | 23.7 ± 23.0 | 0.032 |

| Intestinal transplantation (%) | 2 (13.3) | 6 (31.6) | 0.257 |

| Frequency of central line sepsis (mean ± SD) | 2.1 ± 2.3 | 1.2 ± 2.0 | 0.210 |

| IFALD (%) | 1 (6.3) | 2 (11.1) | 0.618 |

IFALD intestinal failure-associated liver disease, PN parenteral nutrition, TCN total calorie needs, TPN total parenteral nutrition

Discussion

The treatment of IF has evolved with advances in parenteral nutrition support, surgical treatments, and a growing understanding of the complex needs of patients with IF [10, 14]. Advances in small intestine transplant surgery and perioperative management along with immunosuppressants have also had a significant impact. Recently, individualized treatment and multidisciplinary approaches have been adopted to improve the quality of life of patients beyond the survival rate and enable them to live as normally as possible [15]. This has led to the creation of intestinal rehabilitation [16–18].

Medical management of IF requires tailoring to each clinical stage. During the early acute phase, stabilization of fluid and electrolytes is carried out by establishing vascular access and individually optimizing parenteral and enteral nutrition support. Gastrointestinal medication, such as proton pump inhibitors, loperamide, codeine, octreotide, and trophic factors, are used as necessary [5, 6, 14, 19]. In terms of surgical management, the objective is to enhance the existing intestine’s absorptive capacity. This can be achieved by restoring digestive continuity for individuals with an enterostomy or performing lengthening procedures to expand absorption in select patients. The most significant increase in length can ultimately be accomplished through intestinal transplantation, which it is the only viable option for individuals with irreversible IF who have developed life-threatening complications of PN or underlying diseases that cannot be managed effectively [10, 14, 20].

As methods to increase the surface area of the intestine, the Bianchi procedure and STEP are common techniques to be considered. Both procedures have been widely accepted in surgical management for IF [6, 10, 21]. In our rehabilitation center, patients were selected for STEP when the diameter of the small intestine was more than 4 cm, based on imaging studies. STEP was used as an essential tool in our center because of the surgeon’s expertise in the procedure and it is thought to be more tolerable to patients and permits some oral intake even in cases of minimal gut length. Moreover, previous studies have shown that LILT and STEP have comparable rates of leakage and stricture [22]. It is also important to note that STEP does not require manipulation and dissection of the mesentery and vasculature, making it applicable to various degrees of bowel dilatation and intricate segments such as the duodenum and adjacent jejunum [23–25].

Our institution is a referred tertiary hospital that has been treating IF patients in various situations. Since the 1990s, our center has been at the forefront of nutrition management in South Korea, pioneering the establishment of numerous societies dedicated to the field of nutrition including the Korean Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. In 2004, our center created history by successfully performing the first small intestine transplantation in the country to a 57-year-old female with short bowel syndrome due to mesenteric vessel thrombosis [26]. She has been weaned off from PN after the surgery and is still alive up to the last follow-up. Subsequently, the hospital initiated a nationwide program for the rehabilitation of patients with IF, catering to both children and adults [27].

In this study, we analyzed 47 adult IF patients who underwent rehabilitation over the past 20 years at our center. As shown in Table 1, the most common cause of intestinal failure was short bowel syndrome due to mesenteric vessel thrombosis (38.3%). It is worth noting that the causes of IF can vary by age group. In infants and children, common causes include necrotizing enterocolitis, intestinal atresia, postoperative short bowel, and trauma [10]. However, in adults, a common cause of IF includes multiple resections for Crohn’s disease, massive resection due to vascular and obstructive emergencies, and neoplasms [3, 28]. A similar pattern was also observed in our study.

As a result of our IRP shown in Table 2, 18 patients (38.3%) were able to wean off from PN and achieve nutritional autonomy. The adaptation process usually occurred within 3 years, and performing lengthening surgery showed possible association with weaning off. This result is in line with previous studies that adaptation usually occurs during the first two years following intestinal resection in adult. It is important to note that the rate of achieving enteral autonomy is generally lower in adults, with a reported prevalence of 44% [20, 29–31]. Unlike pediatric patients, adult onset IF patients have reached maximal intestinal growth and do not have the capacity for intestinal adaptation through normal growth and increased bowel length [29, 30]. Despite these challenges, patients who were unable to wean off still demonstrated a reduction in PN requirement from 73.5% to 45.8% after the rehabilitation program, accompanied by an increase in their BMI compared to the initial BMI. Our study demonstrates that a comprehensive and multidisciplinary approach with individualized management could improve the quality of life for a significant proportion of adults with IF.

Although weaning off from PN is one of the ultimate goals, home PN remains a key feature of IRP. It is the cornerstone of treatment, offering long-term survival [10, 29]. As a result, survival rates have increased since its introduction in the 1970s. Recently reported survival rates for adults on home PN are 91–97% at 1 year and 62–78% at 5 years [3, 10]. However, complications due to prolonged PN cause 5–20% of the total deaths and factors such as length of remnant intestine, age at the start of home PN, enteral independence, primary disorder, and delayed referral to an intestinal transplantation center may influence the survival rate of patients with IF [3, 10]. Our study found an estimated overall 5-year survival rate of 81.9%. These outcomes can be attributed to two decades of accumulated experience, valuable knowledge, and a systematically implemented approach to IF. Furthermore, our center covers the entire range of treatments from initial surgery that may cause IF and PN optimization to intestinal transplantation. Therefore, we consider the possibility of IF and subsequent management from the time of initial surgery. Moreover, we can offer all treatment options at a single center without delays.

Survival rates have improved through home PN, but at the same time, the occurrence of complications and deterioration in the quality of life due to long-term PN is emerging as a recent problem [20, 28]. In our study, 25 (53.2%) patients developed CRBSI and 5 (10.9%) patients developed IFALD as a complication of long-term PN. In particular, one patient with CRBSI died from line sepsis caused by Candida albicans, and four of the IFALD patients eventually died from liver failure. Close collaboration between healthcare providers, including nutritionists, gastroenterologists, and infectious disease specialists, is essential to prevent and manage these complications effectively [32]. To this end, our IRP conducts prevention education not only for all medical staff but also for patients and their guardians. We also strive to identify catheter infections at an early stage through periodic home nursing and communicate closely with an infectious disease specialist. For the IFALD, a comprehensive approach that includes optimizing PN, lipid minimization, use of omega-3 fatty acids, and regular monitoring of liver function is undertaken throughout IRP.

This study has identified several limitations. Firstly, the results are from a single center in the South Korea, which may limit generalizability to other populations or regions. Secondly, the small sample size represents another significant limitation. The limited sample size might have affected the statistical power and precision of our results and there might be difficulties in drawing strong conclusions and identifying smaller but clinically meaningful differences. However, IF is a rare condition, and recruiting a large number of patients with this condition is inherently challenging. Thirdly, there may be potential sources of bias or confounding factors due to the retrospective nature of this study. In the future, a multicenter study recruiting a larger number of patients is needed to conduct alternative analyzes to complement the results.

IF is a complex condition that involves multiple fields, including surgery, internal medicine, pharmaceuticals, nutrition, nursing, mental health, and economic considerations. As such, a comprehensive approach is crucial to effectively manage IF, reducing complications, improving survival rates, and enhancing the quality of life for patients. This underscores the necessity of a multidisciplinary rehabilitation team. However, assembling such a team is feasible only in specialized medical institutions dedicated to IF, as it requires significant commitment and expertise from a diverse range of professionals. Centralization of such centers is essential, and support from institutions is necessary to establish a robust system.

In line with this, our IRP has demonstrated the effectiveness of a comprehensive rehabilitation approach, involving a multidisciplinary team that addresses various aspects of the disease. This includes individualized nutrition management, specialized medical treatments, and surgical capabilities, ranging from lengthening procedures to intestinal transplantation. Our findings highlight how this approach can help adult IF patients achieve nutritional autonomy, thereby improving their overall health and well-being.

Conclusions

Based on our experience with individualized and multidisciplinary approaches, even adult IF patients have been able to achieve a high rate of successful weaning from PN, resulting in improved quality of life. The concept of intestinal rehabilitation represents a significant advancement in the management of IF, offering hope for improved outcomes and a better quality of life for patients with this challenging condition. Nevertheless, further research is needed to validate these findings and optimize the effectiveness of the program in various clinical settings.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express gratitude to Professor Myung-Duk Lee, who laid the foundation of our rehabilitation program. The results achieved by Prof. Lee’s hard work and affection to rehabilitation of IF are very important and meaningful. The authors also acknowledge Sang-Il Kim (infectious medicine), Jae-Myung Park(gastroenterology), Jeong-Kye Hwang, Mi-Hyeong Kim, Ji-Il Kim, In-Sung Moon (vascular surgery), and intestinal rehabilitation team members for their assistance and administrative support.

Author’s contribution

Conceptualization—KMI and JHC; Data curation—JHC; Formal analysis—JHC; Investigation—KMI; Methodology—JHC; Project administration—JHC; Resources—JHC; Software—KMI; Supervision—JHC; Validation—JHC; Visualization—KMI; Writing original draft, KMI; Writing review & editing—KMI and JHC.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Institutional Review Board of the Ethics Committee of our institution approved and carefully monitored the current study. (IRB No. KC23RISI0158).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants or guardians of participants.

Footnotes

An invited commentary on this article is available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-024-08286-z.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Pironi L, Arends J, Baxter J, et al. ESPEN endorsed recommendations. Definition and classification of intestinal failure in adults. Clin Nutr. 2015;34:171–180. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2014.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown CR, DiBaise JK. Intestinal rehabilitation: a management program for short-bowel syndrome. Prog Transplant. 2004;14:290–298. doi: 10.1177/152692480401400404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pironi L, Hébuterne X, Van Gossum A, et al. Candidates for intestinal transplantation: a multicenter survey in Europe. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1633–1643. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kopczynska M, Carlson G, Teubner A, et al. Long-term outcomes in patients with intestinal failure due to short bowel syndrome and intestinal fistula. Nutrients. 2022;14:1449. doi: 10.3390/nu14071449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merritt RJ, Cohran V, Raphael BP, et al. Intestinal rehabilitation programs in the management of pediatric intestinal failure and short bowel syndrome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;65:588–596. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Billiauws L, Maggiori L, Joly F, Panis Y. Medical and surgical management of short bowel syndrome. J Visc Surg. 2018;155:283–291. doi: 10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2017.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hyo-Jung P, Sang-Hoon L, Ji-Hye Y, et al. Quality improvement activities for establishment of intestinal rehabilitation in intestinal failure patients. J Clin Nutr. 2014;6:101–107. doi: 10.15747/jcn.2014.6.3.101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tannuri U, Barros F, Tannuri AC. Treatment of short bowel syndrome in children. Value of the intestinal rehabilitation program. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 1992;2016:575–583. doi: 10.1590/1806-9282.62.06.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fishbein TM, Matsumoto CS. Intestinal replacement therapy: timing and indications for referral of patients to an intestinal rehabilitation and transplant program. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:S147–151. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thompson JS, Rochling FA, Weseman RA, Mercer DF. Current management of short bowel syndrome. Curr Probl Surg. 2012;49:52–115. doi: 10.1067/j.cpsurg.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sojeong Y, Sanghoon L, Hyo Jung P, et al. Multidisciplinary intestinal rehabilitation for short bowel syndrome in adults: results in a Korean Intestinal Rehabilitation Team. J Clin Nutr. 2018;10:45–50. doi: 10.15747/jcn.2018.10.2.45. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belza C, Wales PW. Intestinal failure among adults and children: similarities and differences. Nutrition in Clinical Practice. 2023;38:S98–S113. doi: 10.1002/ncp.10987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cummings JH, James WP, Wiggins HS. Role of the colon in ileal-resection diarrhoea. Lancet. 1973;1:344–347. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(73)90131-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moon J, Iyer K. Intestinal rehabilitation and transplantation for intestinal failure. Mt Sinai J Med. 2012;79:256–266. doi: 10.1002/msj.21306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kweon M, Ju DL, Park M, et al. Intensive nutrition management in a patient with short bowel syndrome who underwent bariatric surgery. Clin Nutr Res. 2017;6:221–228. doi: 10.7762/cnr.2017.6.3.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bharadwaj S, Tandon P, Meka K, et al. Intestinal failure: adaptation, rehabilitation, and transplantation. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50:366–372. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Byrne TA, Persinger RL, Young LS, Ziegler TR, Wilmore DW. A new treatment for patients with short-bowel syndrome. Growth hormone, glutamine, and a modified diet. Ann Surg. 1995;222:243–254. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199509000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Torres C, Sudan D, Vanderhoof J, et al. Role of an intestinal rehabilitation program in the treatment of advanced intestinal failure. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;45:204–212. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31805905f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jeppesen PB. Pharmacologic options for intestinal rehabilitation in patients with short bowel syndrome. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2014;38:45s–52s. doi: 10.1177/0148607114526241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hukkinen M, Merras-Salmio L, Sipponen T, et al. Surgical rehabilitation of short and dysmotile intestine in children and adults. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:153–161. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2014.962607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frongia G, Kessler M, Weih S, Nickkholgh A, Mehrabi A, Holland-Cunz S. Comparison of LILT and STEP procedures in children with short bowel syndrome - a systematic review of the literature. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48:1794–1805. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bianchi A. Intestinal lengthening: an experimental and clinical review. J R Soc Med. 1984;77:35–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cowles RA, Lobritto SJ, Stylianos S, Brodlie S, Smith LJ, Jan D. Serial transverse enteroplasty in a newborn patient. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;45:257–260. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31803b9564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim HB, Fauza D, Garza J, Oh JT, Nurko S, Jaksic T. Serial transverse enteroplasty (STEP): a novel bowel lengthening procedure. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:425–429. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2003.50073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim HB, Lee PW, Garza J, Duggan C, Fauza D, Jaksic T. Serial transverse enteroplasty for short bowel syndrome: a case report. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:881–885. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3468(03)00115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee MD, Kim DG, Ahn ST, et al. Isolated small bowel transplantation from a living-related donor at the Catholic University of Korea–a case report of rejection -free course. Yonsei Med J. 2004;45:1198–1202. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2004.45.6.1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang HK, Kim SY, Kim JI, et al. Ten-year experience with bowel transplantation at Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital Transplant Proc. 2016;48:473–478. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2015.12.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gotthardt DN, Gauss A, Zech U, et al. Indications for intestinal transplantation: recognizing the scope and limits of total parenteral nutrition. Clin Transplant. 2013;27:49–55. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quirós-Tejeira RE, Ament ME, Reyen L, et al. Long-term parenteral nutritional support and intestinal adaptation in children with short bowel syndrome: a 25-year experience. J Pediatr. 2004;145:157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khan FA, Squires RH, Litman HJ, et al. Predictors of enteral autonomy in children with intestinal failure: a multicenter cohort study. J Pediatr. 2015;167:29–34.e21. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guarino A, De Marco G. Natural history of intestinal failure, investigated through a national network-based approach. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;37:136–141. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200308000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allan P, Lal S. Intestinal failure: a review. F1000Res. 2018;7:85. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.12493.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.