Abstract

Emergence of novel treatment modalities provides effective therapeutic options, apart from conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy, to fight against colorectal cancer. Unfortunately, drug resistance remains a huge challenge in clinics, leading to invariable occurrence of disease progression after treatment initiation. While novel drug development is unfavorable in terms of time frame and costs, drug repurposing is one of the promising strategies to combat resistance. This approach refers to the application of clinically available drugs to treat a different disease. With the well-established safety profile and optimal dosing of these approved drugs, their combination with current cancer therapy is suggested to provide an economical, safe and efficacious approach to overcome drug resistance and prolong patient survival. Here, we review both preclinical and clinical efficacy, as well as cellular mechanisms, of some extensively studied repurposed drugs, including non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, statins, metformin, chloroquine, disulfiram, niclosamide, zoledronic acid and angiotensin receptor blockers. The three major treatment modalities in the management of colorectal cancer, namely classical cytotoxic chemotherapy, molecular targeted therapy and immunotherapy, are covered in this review.

Keywords: Cetuximab, 5-Fluorouracil, Immunotherapy, Irinotecan, Molecular targeted chemotherapy, Pembrolizumab

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer, estimated as 1.8 million new cases and 881,000 deaths in 2018 worldwide [1]. In recent years, the incidence and mortality rate of CRC has declined in some highly developed countries [2], which is largely attributed to the implementation of population screening, surgical advances, more well-established treatment guidelines and emerging new therapies [3].

Treatment and management of CRC vary with tumor stage, location and patient characteristics. For early-stage CRC lesions, surgical approaches are used, from local treatment such as polypectomy, to more invasive procedures such as transabdominal resection and anastomosis, depending on tumor location and disease invasion [4, 5]. However, for advanced or metastatic cancer, surgical resection alone fails to offer curative treatment. Chemotherapy is thus introduced to patients as neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy, to shrink the tumor before surgery and to prevent tumor recurrence after surgery, respectively, [5–7]. Fluoropyrimidine, for example 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and capecitabine, is a first-line chemotherapeutic agent for metastatic CRC (mCRC) and is usually given in combination with other cytotoxic agents (such as irinotecan, oxaliplatin) due to the evidence of improved response rate (RRs) and progression-free survival (PFS) [4]. The common chemotherapy regimens used in clinics include FOLFOX (5-FU/leucovorin/oxaliplatin), FOLFIRI (5-FU/leucovorin/irinotecan), CAPOX (capecitabine/oxaliplatin) and FOLFOXIRI (5-FU/leucovorin/oxaliplatin/irinotecan) [6]. The precise mechanisms contributing to the cytotoxic effect are distinct for different chemotherapeutic agents. Generally, they act to impair DNA replication, transcription and repair, thus promoting cell death [8].

Apart from cytotoxic chemotherapy, molecular targeted therapy has become increasingly important for mCRC treatment since the early 2000s. The commonly used targeted therapies are monoclonal antibodies targeting epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) or vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). EGFR overexpression is observed in 65–70% CRC tumors and is associated with disease progression, poor prognosis and shorter survival [9]. Cetuximab and panitumumab, the two United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved EGFR monoclonal antibodies, direct against the extracellular domain of EGFR and inhibit the downstream Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway, thus retarding tumorigenesis and cancer proliferation [10, 11]. Both drugs may be given as monotherapy or in combination with other chemotherapy regimens. Importantly, they give rise to survival, PFS and RR benefits when compared to chemotherapy alone [12]. Another therapeutic option is monoclonal antibody against VEGF. Currently, clinically approved VEGF monoclonal antibodies for mCRC include bevacizumab, ramucirumab and aflibercept. Ligand binding to VEGFR promotes tumor angiogenesis and is associated with cancer progression and metastasis [13]. VEGF monoclonal antibodies reduce vessel density, patency and vascular permeability, inhibit ascites formation, tumor growth and angiogenesis, and have been shown to bring survival benefits to mCRC patients in a number of clinical trials [14].

Immunotherapy is an emerging treatment modality in recent years, which has demonstrated remarkable clinical activity in several cancer types and brought an immense breakthrough in medical oncology. The use of immune checkpoint inhibitors has shown promising efficacy in CRC patients with microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H)/mismatch repair deficient (dMMR) tumors [15]. This has led to the recent FDA approval of PD-1 inhibitor (pembrolizumab and nivolumab) and CLTA-4 inhibitor (ipilimumab) for MSI-H or dMMR mCRC. Both PD-1 and CLTA-4 are coinhibitory molecules in the regulation of immune response. The corresponding signaling blockade restores T cell activation and stimulates antitumor immune response, which ultimately kills tumor cells carrying tumor-associated antigen [16, 17].

Despite the various treatment options available, drug resistance problem remains an obstacle to successful therapy. A large portion of patients either do not respond to a treatment strategy, or initially respond but experience relapse and disease progression after a period of time, owing to primary and acquired resistance, respectively, [8]. This eventually leads to treatment failure, necessitating a regimen switch.

There is an urgent need for therapeutic strategies to overcome drug resistance in CRC. Table 1 summarizes the major mechanisms of resistance to different treatment modalities for CRC and the current strategies for their circumvention. Development of novel anticancer agents is one of the possible solutions [11, 15, 18, 19]. Some novel EGFR inhibitors, Sym004 and MM-151, can bind to a mutated extracellular domain of EGFR and inhibit the downstream EGFR signaling pathways, which are demonstrated to overcome resistance to cetuximab and panitumumab [11, 18]. On the other hand, several new immunological agents have been investigated, including cancer vaccination, oncolytic virus therapy, IDO1 inhibitors and anti-OX40 agonists [15]. A combination of these novel agents with cancer immunotherapy is being studied to circumvent drug resistance [20]. Besides, there is also increasing interest toward gene therapy (which involves inactivation of resistance genes using microRNA or siRNA) and formulation of nanoparticle drug delivery systems to combat resistance [21].

Table 1.

Major mechanisms of resistance to different treatment modalities and current strategies for their circumvention

| Treatment | Mechanisms of resistance | Current combating strategies | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Novel agent development | Combination of multiple anticancer agents | Drug repurposing | ||

| Classical cytotoxic chemotherapy | Genetic or epigenetic alterations (e.g., p53 mutation, Bcl-2 overexpression), ABC transporter overexpression | Not an attractive target due to the low specificity and high toxicity of chemotherapeutic agents |

5-FU and choline kinase α (ChoKα) inhibitors (e.g., MN58b and TCD-717) Irinotecan and tyrosine kinase inhibitors (e.g., sorafenib) |

NSAIDs Metformin Statin Chloroquine Disulfiram |

| Molecular targeted therapy | Constitutive activation of EGFR signaling or other bypass pathways due to aberrant genetic alterations (e.g., KRAS mutation) |

Novel EGFR mAb: Sym004 and MM-151 Novel VEGF mAb: VGX-100, tanibirumab, vanucizumab |

EGFR mAb and VEGF inhibitor EGFR mAb and BRAF inhibitor (e.g., dabrafenib) EGFR mAb and MEK inhibitor (e.g., PD98059) |

Statin Niclosamide NSAIDs Chloroquine Zoledronic acid |

| Immunotherapy |

Tumor-intrinsic factors: loss of antigen protein or antigen presentation, T cell exhaustion Tumor-extrinsic factors: absence of T cells, immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment |

Cancer vaccination Oncolytic virus therapy IDO1 inhibitors Anti-OX40 agonists |

PD-1 blockade and CTLA-4 blockade PD-1 blockade and EGFR inhibitor (e.g., gefitinib) PD-1 blockade and TGFβ inhibitors (e.g., LY2157299) |

NSAIDs Metformin RAS inhibitors |

EGFR epidermal growth factor receptor, mAb monoclonal antibody, NSAIDS non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, RAS renin–angiotensin system, VEGF vascular endothelial growth factor

An alternative strategy is drug combination [20, 22–24], which aims to achieve dual blockade in both vertical and parallel signaling pathways. Various preclinical studies and clinical trials have evaluated the safety and efficacy of different combination regimens, such as EGFR inhibitor plus VEGF inhibitor/MEK inhibitor/BRAF inhibitor [22], PD-1 blockade plus CTLA-4 blockade and PD-1 blockade plus EGFR inhibitor [20].

While the most common approach is to target oncogenic proteins or signaling, some studies have advocated a completely different perspective and attempted to combat resistance using a specific dosing schedule of existing anticancer drugs. The use of an intermittent or alternate dosing schedule is suggested to utilize the effect of “drug holidays” and collateral sensitivity, respectively, to overcome drug resistance [25].

Drug repurposing is another novel approach that diverts from the classical pathway of drug development pipeline. While novel drug discovery is usually accompanied by tremendous cost, long development time and high attrition rates, drug repurposing has gained a lot of attention in recent years. By assigning a clinically approved drug with new indications, drug repurposing reduces time frame and cost for development and allows quick translation from bench to bedside, as preclinical efficacy testing and formulation development have already been completed. Since the optimal dosing and the safety/toxicity profile of an existing drug are already well established, this approach arouses less safety concern and is usually approved sooner and at a higher success rate [26].

To repurpose a drug, the algorithm includes (1) identification of potential drug candidates, (2) mechanistic investigation in preclinical models and (3) safety and efficacy assessment in clinical trials. The first step is the most critical part and is usually accomplished by different systematic approaches to identify the candidate molecules and construct hypothesis. The experimental approaches usually involve performing high-throughput phenotypic screening or binding assays to identify target interactions. Computational approaches, in which scientists conduct large-scale data analysis, are also on the rise, including genetic association, signature matching and retrospective clinical analysis. Details of each repurposing approach are reviewed elsewhere [27].

In view of the dire needs of novel anticancer therapies, drug repurposing has drawn increasing interest in the field of oncology. In this review, we focus on the efficacy and the underlying cellular mechanisms of different repurposed drugs to overcome drug resistance in CRC, which are observed in three major treatment modalities: classical cytotoxic chemotherapy, molecular targeted therapy and immunotherapy, respectively.

Classical cytotoxic chemotherapy

Chemotherapy resistance comprises two representative cellular mechanisms: (1) genetic and epigenetic alterations, such as p53 mutation and overexpression of antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL; and (2) overexpression of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters, leading to drug efflux and decreased intracellular drug accumulation [28]. Thus, drugs repurposed to overcome CRC chemoresistance target, but are not limited to, these resistance mechanisms, and some of the attempts are reviewed below.

Drugs repurposed to overcome multidrug resistance to cytotoxic chemotherapeutic drugs by inhibiting ABC transporters

Multidrug resistance (MDR) is one of the suggested mechanisms accounting for chemotherapy resistance. It is predominantly caused by the overexpression of ABC transporters, which mediate drug efflux and protect tumor cells against classical cytotoxic agents [21]—though the role of these transporters in clinical drug resistance is still under debate. Three major ABC transporters, including P-glycoprotein (P-gp/ABCB1), multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 (MRP1/ABCC1) and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP/ABCG2), have been extensively studied. Enormous research efforts have been invested in the field to develop MDR transporter inhibitors to reverse MDR.

First-generation MDR inhibitors were developed by the drug repurposing approach. Examples include verapamil (calcium channel blocker used to treat cardiovascular disorders), cyclosporin A (immunosuppressant), quinidine (antimalarial drug) and trifluoperazine (antipsychotics used to treat schizophrenia) [21]. Despite the good efficacy in preclinical data, these agents have shown low therapeutic response or unacceptable toxicity at MDR-reversing concentration in clinical trials [29–32]. Nevertheless, they are the cornerstone for the development of second- and third-generation MDR transporter inhibitors, some of which are analogs or derivatives of these repurposed drugs [33], yet toxicity remains the major cause accounting for failure of later trials [34, 35].

In recent decades, other repurposed drugs are also proposed to inhibit MDR transporters. Sildenafil and vardenafil [36, 37], phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors that are commonly used to treat erectile dysfunction, as well as statin [38], a lipid-lowering drug, are reported to directly inhibit ABC transporters. Celecoxib [39, 40], an anti-inflammatory agent, is also suggested to downregulate MDR1 expression (which encodes P-gp) and reverse MDR. Further clinical trials are warranted to examine its therapeutic efficacy and safety profile.

Although there may not be direct evidence between these agents and chemotherapy resistance in CRC, it is important for us to acknowledge the significance of MDR and the well-known MDR-reversing agents derived from drug repurposing strategies. Table 2 summarizes representative clinical trials that evaluated the efficacy of combining repurposed drug and cytotoxic chemotherapeutic drugs.

Table 2.

Clinical trials that evaluate the efficacy of combining an anticancer drug with a repurposed drug

| Anticancer drug | Repurposed drug | Phase | Target population | n | Dosing schedule | ORR | DCR | PFS | OS | Major toxicity | Remarks | Clinical trial registry number | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Cytotoxic chemotherapy | |||||||||||||

| Vincristine and doxorubicina | Verapamil | III | Resistant or relapsing myeloma patients | 127 | Verapamil PO 120 mg BD on days 1–3, then increase to 120 mg QID on day 4–12, IV vincristine 0.4 mg/day and doxorubicin 9 mg/m2 on days 8–11, dexamethasone PO 40 mg/day on days 1–4 and 9–12 | 36% vs 41% (p = n.a.) | – | – | 13 months vs 10 months (p = 0.022) | Similar toxicity profile in two treatment arms, including myelosuppression, Grade 3 or 4 leukopenia, thrombocytopenia | No beneficial effects of adding verapamil, probably because of the insufficient verapamil level to reverse MDR | Not available | [29] |

| Daunorubicin and etoposide | PSC-833 (valspodar; cyclosporin A analog) | III | Untreated acute myeloid leukemia patients over age 60 | 120 | IV PSC-833 2.8 mg/kg over 2 h, then 10 mg/kg/day for 3 days, IV cytarabine 100 mg/m2 daily for 7 days, daunorubicin 40 mg/m2 and etoposide 60 mg/m2 for 3 days (ADEP arm), or IV cytarabine 100 mg/m2 daily for 7 days, daunorubicin 60 mg/m2 and etoposide 100 mg/m2 daily for 3 days (ADE arm) | – | – | – | Around 33% for both arms (p = 0.48) | More frequent hyperbilirubinemia (53% vs 25%), stomatitis (25% vs 7%), anorexia (24% vs 7%), esophagitis (17% vs 3%), diarrhea (24% vs 8%) and Grade 5 toxicities (7 infections and 1 hepatic toxicity vs 3 infections) in ADEP arm | ADEP arm was closed after randomization due to excessive early mortality (44% vs 20%, p = 0.008) | NCT00003190 | [34] |

| 5-FU and irinotecan | Rofecoxib | II | mCRC patients, progressive after FOLFOX4 regimen | 48 | Rofecoxib PO 50 mg daily, IV irinotecan on days 1,8,15,22, infusional 5-FU at 200 mg/m2 for 5 weeks, followed by 3 weeks of rofecoxib alone | 48.5% | 78.8% | – | 18 months | Diarrhea (75.8%), alopecia (36.4%), vomiting (30.3%), asthenia (12.1%), moderate hematological toxicity. No cardiac or thromboembolic toxicity | Feasible, well-tolerated and effective second-line treatment | Not available | [45] |

| Irinotecan and capecitabine | Celecoxib | II | mCRC patients | 51 | Celecoxib PO 800 mg daily, IV irinotecan 70 mg/m2 over 30 min on day 1 and 8, oral capecitabine 1000 mg/m2 BD on day 1 to 14 | 41% | – | – | 21.2 months | Major toxicity: Grade 3 or 4 diarrhea (24 and 10% of patients, respectively) | Addition of celecoxib did not significantly improve activity of irinotecan/capecitabine treatment | NCT00258232 | [47] |

| 5-FU and irinotecan | Celecoxib | II | Previous untreated metastatic or advanced CRC patients | 47 | Celecoxib PO 400 mg BD, weekly irinotecan 125 mg/m2, 5-FU 500 mg/m2, and leucovorin 20 mg/m2 for 4 weeks Q6 W | 31.9% | – | 8.7 months | 19.7 months | Neutropenia (31.9%), diarrhea (21.3%), nausea/vomiting (21.8%), infection (8.5%) | Overall tolerable, but celecoxib does not increase efficacy of chemotherapy | Not available | [48] |

| Irinotecan | Metformin | II | ECOG 0-1 patients with heavily pretreated, refractory mCRC | 38 | Metformin PO daily (up to 2500 mg/day), IV irinotecan 125 mg/m2 on day 1 and 8 Q3W | / | 57% | 12.6 weeks | 39 weeks | Grade 3 diarrhea (21%), 1 event of grade 4 neutropenic fever | Safe and effective treatment for heavily pretreated mCRC population | NCT01930864 | [54] |

| 5-FU | Metformin | II | Previously treated, refractory mCRC patients | 50 | Metformin PO 850 mg BD, IV 5-FU 425 mg/m2 and leucovorin 50 mg weekly | / | 22% | 1.8 months | 7.9 months | Grade 1 or 2 diarrhea (64%), nausea (50%), emesis (30%), Grade 3 or higher asthenia (6%), myelotoxicity (4%) | Tolerable, overall modest activity. Prolonged survival for obese patients and those who are longer off 5-FU | NCT01941953 | [55] |

| FOLFIRI/XELIRI | Simvastatin | III | Previous treated mCRC patients | 269 | Simvastatin PO 40 mg QD, IV irinotecan 180 mg/m2, leucovorin 200 mg/m2, 5-FU bolus 400 mg/m2 then infusion at 2400 mg/m2 (FOLFIRI regimen), or IV irinotecan 250 mg/m2, capecitabine 1000 mg/m2 BD (XELIRI regimen) | 11.9% vs 11.8% (p = 1.00) | 67.2% vs 71.1% (p = 0.511) | 5.9 months vs 7.0 months (p = 0.937) | 15.3 months vs 19.2 months (p = 0.826) | Grade 3 or higher nausea and anorexia is slightly more often in simvastatin arm | No significant difference in terms of efficacy and toxicity between simvastatin and placebo arms | NCT01238094 | [63] |

| 2. Molecular targeted drugs | |||||||||||||

| Cetuximab | Simvastatin | II | Previously treated KRAS-mutated mCRC patients | 18 | Simvastatin PO 80 mg QD, IV cetuximab 400 mg/m2 at least one week after start of simvastatin therapy, followed by infusion at 250 mg/m2 | 6% | – | 9 weeks | 31.5 weeks | Fatigue (61%), acne (56%), rash (33%), 3 events of elevated creatinine kinase level | Simvastatin is unable to overcome cetuximab resistance in KRAS-mutated CRC patients | NCT01190462 | [82] |

| Panitumumab | Simvastatin | II | Previously treated KRAS-mutated mCRC patients | 17 | Simvastatin PO 80 mg QD, IV panitumumab 6 mg/kg Q2W, at least one week after the start of simvastatin therapy | 0% | – | 8.4 weeks | 19.6 weeks | Grade 3 or higher fatigue (21%), nausea (14%), 3 events of elevated creatinine kinase level and myopathy | Simvastatin is unable to overcome panitumumab resistance in KRAS-mutated CRC patients | NCT01110785 | [83] |

| Cetuximab and irinotecan | Simvastatin | II | Previously treated KRAS-mutated mCRC patients | 52 | Simvastatin 80 mg QD, IV cetuximab 500 mg/m2 and irinotecan 150-180 mg/m2 Q2W | 1.9% | 65.4% | 7.6 months | 12.8 months | Grade 3 or higher anemia (28.8%), neutropenia (13.5%), diarrhea (7.7%) | KRAS-mutated CRC with low Ras signature score is more likely to benefit from the combination therapy | NCT01281761 | [85] |

| Cetuximab | Celecoxib | II | Cetuximab-naïve patients with refractory CRC | 17 | Celecoxib PO 200 mg BD, cetuximab 400 mg/m2 loading dose, then 250 mg/m2 weekly | – | – | 55 days | – | Grade 3 or higher hypersensitivity (18%), dermatological toxicities (12%), anemia (12%) | Terminated early owing to the lack of sufficient clinical efficacy | NCT00466505 | [108] |

Observational studies are not included in this table

BD twice daily, DCR disease control rate, ECOG Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, IV intravenous, ORR objective response rate, OS overall survival, PFS progression-free survival, PO by mouth, QD once daily, Q3W every 3 weeks, Q6W every 6 weeks; vs, versus

# Representative trials about other MDR-reversing repurposed drugs (e.g., cyclosporin A, trifluoperazine) may be found in reference 128–130

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

NSAIDs are widely prescribed as anti-inflammatory drugs. They function as cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitor and suppress conversion of arachidonic acid to prostaglandins and thromboxanes. COX enzymes consist of two subtypes: COX-1 and COX-2. COX-1 is the housekeeping enzyme that maintains homeostasis in various sites such as stomach and kidneys, whereas COX-2 promotes inflammation, pain and fever. Meanwhile, CRC development is often promoted by chronic inflammation and COX-2 overexpression is associated with elevated Bcl-2 and P-gp expression [40, 41], leading to chemotherapy resistance. The evidence suggests that NSAIDs/COX-2 inhibitors might play a pivotal role in restoring chemosensitivity in CRC via inhibiting the COX-2 pathway.

A combination of celecoxib and chemotherapy induces significant therapeutic responses in chemorefractory CRC cells and overcomes CRC resistance to 5-FU and irinotecan both in vivo and in vitro. By downregulating COX-2 expression, celecoxib augments caspase-dependent apoptosis and suppresses MDR1 expression [42]. Diclofenac has also been reported to suppress Bcl-2 and enhance Bim and Bax expression, leading to upregulation of caspase family and mitochondrial intrinsic apoptosis [43]. On the other hand, NSAIDs may target apoptosis evasion, which is one of the hallmarks of chemoresistant CRC cells [41].

NSAIDs are also suggested to overcome chemoresistance by suppressing cancer stem cells (CSCs). A combination of indomethacin and 5-FU suppresses CSC populations and significantly inhibits tumor growth in 5-FU-resistant SW620 cells by inhibiting the COX-2 and Notch pathway and activating PPARγ [44].

In views of anticancer activities of NSAIDs, a few clinical trials have attempted to introduce NSAIDs to a CRC chemotherapy regimen. While some trials demonstrated a survival benefit [45, 46], many of them have failed to improve patient outcomes [47, 48]. Further clinical studies and improved trial design are warranted.

Metformin

Metformin is the first-line agent to treat type 2 diabetes mellitus. It lowers plasma glucose by suppressing hepatic gluconeogenesis, improving insulin sensitivity and enhancing peripheral glucose uptake and utilization. In recent years, metformin was also reported to demonstrate anticancer activities. Hence, a combination of metformin and chemotherapy has been extensively investigated to overcome chemoresistance.

Antineoplastic effect of metformin is mainly mediated by activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and inhibition of the NF-κB signaling pathways. A combination of metformin and cytotoxic chemotherapy (5-FU, oxaliplatin) shows a synergistic effect on (1) reducing the proportion of the CSC population and inhibiting colonospheres formation by downregulating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway [49, 50]; and (2) inducing cell cycle arrest and cell death by activating the AMPK/mTOR axis [50, 51]. Metformin was also reported to downregulate the DNA replication machinery proteins (MCM2 and PCNA) selectively in 5-FU-resistant colon cell lines and lead to a synergistic effect with chemotherapy [51].

Some clinical trials have evaluated the benefits of combined metformin and chemotherapy regimen. Variable efficacy was reported [52–55], which is probably due to the different design of trials. A phase II clinical trial has reported a good safety and efficacy profile of the combination of metformin and irinotecan in a group of refractory CRC patients [54]. Another phase II trial evaluating the combination therapy of metformin and 5-FU also produced similar favorable result. Interestingly, despite the overall modest activity, patients that are obese or are rechallenged after longer off from 5-FU were found to benefit more with prolonged DFS [55]. This suggested that a subgroup of refractory mCRC patients may receive additional benefits from such combination regimen.

Statin

Statins are widely used to treat hypercholesteremia by inhibiting HMG-CoA reductase, the rate-limiting enzyme of the endogenous cholesterol synthetic pathway. A number of statins are approved and commonly prescribed in clinics, namely simvastatin, lovastatin and atorvastatin.

Statins are suggested to overcome chemotherapy resistance in various preclinical studies. For instance, addition of simvastatin [56], lovastatin [57] or cerivastatin [58] to chemotherapy, respectively, resulted in synergistic anticancer proliferation effect in resistant CRC cell lines. One of the proposed mechanisms involves the inhibition of cancer stemness. Statin is suggested to activate a tumor-suppressive bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling pathway. Acting as DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) inhibitor, statin demethylates BMP, TIMP3 and HIC1 promoter region and reactivates BMP expression. Activated BMP signaling inhibits stemness and promotes cell differentiation, which resensitizes CRC cells to 5-FU treatment [57]. Statin could also be a potential drug candidate via epigenetic reprogramming in treating CRC tumor with CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP), which shows aberrant DNA methylation thus conferring chemotherapy resistance [59].

Statin also interferes with the insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF-1R) signaling. The IGF-1R pathway promotes cell survival and proliferation, and its overexpression promotes inhibition of apoptosis and upregulation of ABC transporter proteins, thereby contributing to chemotherapy resistance [60]. Simvastatin was shown to downregulate the IGF-1R pathway and inhibit IGF-1R-induced antiapoptotic ERK/Akt activation in HT 29 cell line, which subsequently induces apoptosis via activation of caspase-3, downregulation of Bcl-2 and upregulation of Bax [61] to restore sensitivity to chemotherapy.

In light of the successful preclinical data, several clinical trials have evaluated the benefits of adding statin to chemotherapeutic treatment in CRC patients. However, most of them are unable to improve PFS and OS [62, 63], which is suggested to be due to the poor trial design [64].

Chloroquine

Discovered in the 1930s, chloroquine has long been used to treat malarial infections. It also demonstrates anticancer properties, and is widely studied as antitumor agent or adjuvant agent to overcome drug resistance. Chloroquine exerts dual activities on CRC cells by acting as autophagy inhibitor and lysosomal membrane permeabilization (LMP) inducer, which accounts for its anticancer activity [65]. Autophagy, a physiological process that regulates lysosome-mediated degradation of excessive or damaged components, is induced to protect against cellular stress and confer resistance in response to chemotherapy [49]. The addition of chloroquine to chemotherapy regimen, namely 5-FU and oxaliplatin, produces synergistic antiproliferative effect [66–68] and overcomes resistance [69] by inhibiting autophagy and inducing apoptosis. Apart from autophagy inhibition, chloroquine was also proposed to inhibit TLR9/NFκB signaling and activate the p53 pathway [70]. These two mechanisms might be complementary to each other for the reversal of chemoresistance in CRC patients.

A number of clinical trials have been initiated to investigate the anticancer effect of chloroquine [70]. Nevertheless, few of them were designed for CRC patients. Limited evidence is available to demonstrate the efficacy of chloroquine in overcoming chemoresistance in CRC patients.

Disulfiram

Disulfiram is used to treat chronic alcoholism. It causes an acute sensitivity reaction to alcohol and produces hangover-like symptoms to deter people from drinking. Disulfiram can also act as an NF-κB inhibitor. In human CRC cell lines, high NF-κB activity is induced by 5-FU [71], leading to resistance to apoptosis and chemotherapy resistance. By combining disulfiram and 5-FU, a synergistic apoptotic effect was observed in 5-FU-resistant cell lines. Besides, recent studies suggest that a disulfiram/copper complex can further potentiate the cytotoxic effect. The complex has also been reported to overcome resistance to oxaliplatin, SN-38 (active metabolite of irinotecan) [72] and gemcitabine [73] by NF-κB inhibition. Disulfiram was also suggested to inhibit the survival of CSC. By inhibiting the NF-κB-mediated stemness gene pathway, disulfiram targets CSCs and enhances cytotoxicity of paclitaxel, cisplatin and chemoradiation in breast [74] and pancreatic cancer [75]. The CSC-suppressing effect in CRC cells is yet to be demonstrated.

Of note, there is currently no clinical trial evaluating the use of disulfiram or its copper complex on CRC patients. It is still not sure whether the circumvention of chemoresistance by disulfiram observed in preclinical studies can be successfully translated to the bedside.

Molecular targeted therapy

Primary and acquired resistance to EGFR inhibitors arises from the aberrant genetic alterations of members in EGFR signaling pathways or other bypass pathways, leading to failure in blocking EGFR and its downstream signaling. The most notable aberration includes secondary EGFR mutations; KRAS/NRAS, BRAF or PI3KCA mutations; and activation of the JAK/STAT, IGF-1R and/or MET signaling pathways. Detailed mechanisms of resistance have been discussed elsewhere [22, 76].

To date, drug repurposing attempts to overcome resistance to VEGF inhibitors in CRC are highly limited. Therefore, the following review sections mainly focus on EGFR inhibitors for CRC treatment, namely cetuximab and panitumumab. Findings from representative clinical trials evaluating the combination of cetuximab/panitumumab and repurposed drugs are summarized in Table 2.

Statins

Statin inhibits the conversion of HMG-CoA to mevalonate. Mevalonate is a substrate of farnesyl and geranylgeranyl moieties, which facilitate Ras/Rho tethering to cell membrane. Hence, depletion of mevalonate inhibits KRAS prenylation and prevents membrane localization and activation of signal transduction pathways. It was first hypothesized that statin may help overcome drug resistance to EGFR inhibitor in KRAS-mutated cancer [77, 78]. Indeed, statin was reported to overcome anti-EGFR therapy resistance in preclinical studies, however, not by inhibiting Ras prenylation. Simvastatin reverses cetuximab resistance in KRAS-mutated CRC cell lines by inhibiting BRAF enzymatic activity [79]. As BRAF/MEK signaling plays a crucial role in regulating the proapoptotic proteins including Bad and Bim [80], statin induces apoptosis via modulating BRAF activity. This proposed mechanism was further supported by the fact that statin-mediated resistance circumvention was not observed in BRAF-mutated cells [79]. Another recent research has also shown that fluvastatin-induced antiproliferation is independent of Ras prenylation, but is closely associated with epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT). EMT is known to confer anti-EGFR therapy resistance. Interestingly, induced EMT has been shown to increase cancer cell sensitivity to fluvastatin [81]. Thus, statins may be used to target the increased EMT found in anti-EGFR-resistant cancer cells.

Several clinical trials have tried to introduce simvastatin to current therapy for KRAS-mutated CRC patients. Unfortunately, most of them have failed to provide significant survival benefits [82–84]. This suggests that KRAS mutation status is unlikely the only predictive biomarker for statin treatment response. Another clinical trial has demonstrated that the addition of simvastatin to cetuximab/irinotecan regimen can overcome cetuximab resistance [85]. However, therapeutic benefit was only observed in patients bearing tumors with KRAS mutation and low Ras signature [85]. Ras signature score is derived from expression of Ras pathway-related genes across multiple databases and reflects other possible aberrations such as BRAF and PI3KCA mutation [86]. Therefore, factors other than KRAS mutation have to be considered to predict the usefulness of statin in overcoming resistance to anti-EGFR therapy.

Niclosamide

Niclosamide is an old anthelmintic drug that has been widely used to treat tapeworm infestations for more than 50 years. In recent years, there has been increasing interest in its novel role in anticancer therapy. Niclosamide may reverse CRC resistance to molecular targeted therapy by inhibiting the STAT3 pathway. Constitutive activation of the STAT3 pathway, which inhibits apoptosis and induces cell proliferation and invasion, promotes acquired resistance to anti-EGFR therapies in CRC. Thus, the STAT3 pathway represents an attractive therapeutic target for circumvention of resistance. Importantly, STAT3 inhibitor has been reported to reverse resistance to anti-EGFR therapies [87]. To this end, niclosamide is known to be a STAT3 inhibitor. A combination of niclosamide and erlotinib was found to give rise to synergistic apoptotic and antiproliferative effect and to overcome erlotinib resistance by inhibiting STAT3 [88]. Niclosamide-mediated reversal of resistance was also reported in other cancer types, including non-small cell lung cancer [89], head and neck squamous cell carcinoma [90, 91] and bladder cancer [91].

Another proposed mechanism is the inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling is associated with cetuximab resistance. Thus, inhibition of this pathway can restore CRC sensitiveness to cetuximab treatment [92]. Niclosamide was also shown to inhibit Wnt signaling and retard cell proliferation in CRC, which represents another possible mechanism to overcome resistance to EGFR inhibitors [93, 94]. By inhibiting GSK-3, a key kinase in Wnt signaling, the cross talk between Wnt and Ras signaling also enables niclosamide to inhibit the Ras-driven resistance-related pathway [95]. Although currently there is still no direct clinical evidence showing the beneficial use of niclosamide to potentiate therapeutic response to anti-EGFR therapies, niclosamide may represent a potential drug candidate to be repositioned for CRC treatment.

Clinical trials on niclosamide as anticancer agents are limited. The most recent attempt is to introduce niclosamide monotherapy to CRC patients (NCT02519582 [96] and NCT02687009), which is still at the recruitment stage.

NSAIDs

COX-2 upregulation is closely associated with acquired resistance to anti-EGFR therapies in CRC cell lines [97]. COX-2 knockdown inhibits prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) synthesis and resensitizes resistant cell lines [95]. PGE2 activates various pathways, such as PI3K/Akt, Ras/MAPK and Wnt signaling, thus contributing to cell invasion, growth and evasion of apoptosis [41, 98]. These downstream pathways also enhance COX-2 expression, forming a feedback loop [98]. NSAIDs may thus reverse resistance to molecular targeted therapy by targeting the COX-2 pathway.

NSAIDs suppress FOXM1 expression by interfering with EGFR/Ras signaling. FOXM1 transcription factor triggers stem cell renewal, cell survival and DNA repair. Overexpression of FOXM1 has been shown to confer resistance to molecular targeted therapies [99]. To this end, a combination of celecoxib and cetuximab inhibits cell proliferation and induces G1 cell cycle arrest in cetuximab-resistant HT29 cells, via suppressing EGFR/Ras/FOXM1 signaling. Notably, proliferation of KRAS-mutated CRC tumors is not affected by the addition of celecoxib [100]. This is consistent with a large-scale clinical study, in which NSAIDs use after diagnosis of CRC only improves OS in KRAS-wild-type CRC patients but not KRAS-mutated patients [101], though the exact interaction site of NSAIDs with EGFR/Ras axis remains unclear.

NSAIDs may be particularly useful in treating PI3KCA-mutated CRC tumors. PI3KCA mutation confers acquired resistance to cetuximab and reduces PFS in metastatic CRC patients [102], by inducing PI3K/Akt pathway activation and resistance to apoptosis [103]. Aspirin was reported to act as an mTOR inhibitor and AMPK activator, thus inhibiting the PI3K/Akt pathway in CRC [104]. In preclinical studies, aspirin was found to induce apoptosis and G0/G1 cell cycle arrest more profoundly in PI3KCA-mutated than wild-type CRC cell lines. Several clinical studies also reported improvement in survival [105] and reduction of recurrence [106] only in PI3KCA-mutated patients with regular aspirin use. Although there is still limited evidence demonstrating the efficacy of aspirin to reverse resistance to EGFR therapies via PI3K/Akt inhibition, aspirin use is suggested to be a potential therapeutic strategy in treating tumors with PI3KCA mutation or PTEN loss [107].

A phase II clinical trial has been conducted to evaluate the combination of cetuximab and celecoxib in a group of chemorefractory mCRC patients. The study was terminated early due to the lack of significant clinical efficacy [108]. However, this trial does not consider the mutation profiles of patients, namely KRAS, BRAF and PI3KCA mutation, which affect patient response to the combination therapy. In further clinical studies, more careful patient and biomarker selection are warranted.

Chloroquine

Autophagy induction is one of the cellular mechanisms accounting for resistance to molecular targeted therapy. In several cancer cell lines with aberrant EGFR expression, such as squamous cell vulvar cancer (A431), NSCLC (HCC827) and colorectal cancer (DiFi), the induction of autophagy by cetuximab was reported to counteract the anticancer effect from the anti-EGFR therapy. Mechanistically, cetuximab downregulates HIF-α and Bcl-2, and activates beclin-1/hVps34 complex to induce autophagy, which subsequently protects cancer cells from apoptotic cell death [109].

Chloroquine was also shown to overcome autophagy-mediated resistance by inhibiting the lysosomal degradation pathway. A combination of chloroquine and cetuximab was reported to inhibit autophagic flux and synergistically enhance apoptosis in DiFi cells. The effect was found to be even more profound in the cetuximab-resistant subline, which has high basal autophagy [110].

Besides, chloroquine was also reported to overcome bevacizumab resistance in glioblastoma. Bevacizumab monotherapy induces hypoxia and activates autophagy, thus confers resistance to anti-angiogenic therapy [111]. A combination of chloroquine and bevacizumab effectively abolishes drug tolerance and augments cell apoptosis [112]. However, it is still uncertain whether chloroquine acts in a tumor-specific manner and is effective in CRC cells as well.

Zoledronic acid

Zoledronic acid is the third generation of bisphosphonates. It is clinically used to treat osteoporosis and cancer-related hypercalcemia and prevent skeletal complications owing to bone metastases. Zoledronic acid has been reported to inhibit both Ras/MAPK and Akt/mTOR pathway and lead to a synergistic antiproliferative effect with cetuximab in CRC cells. More importantly, this growth suppression was also observed in CRC cells with KRAS mutation [113], where the constitutive activation of the Ras pathway confers resistance to anti-EGFR therapy. By inhibiting Ras prenylation and thus the downstream signaling pathways, zoledronic acid overcomes cetuximab resistance in KRAS-mutated CRC and induces apoptosis.

Recent research also shows that zoledronic acid inhibits autophagy in colon cancer cells (CT26). Zoledronic acid effectively upregulates p62 and downregulates beclin-1, thus suppresses autophagy [114]. As autophagy is induced upon anti-EGFR therapy treatment and confers resistance in CRC cells [109], zoledronic acid may help to restore CRC cell sensitivity to anti-EGFR therapy by inhibition of autophagy.

Immunotherapy

The use of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) has achieved enormous clinical success and revolutionized the practice of cancer management. Nevertheless, both primary and acquired resistance remain a challenge that prevents patients from responding to the therapies or having a durable disease control. Resistance mechanisms to ICI are divided into tumor-intrinsic and -extrinsic factors. Tumor-intrinsic factors include oncogenic signaling (such as MAPK, Wnt) that promotes T cell exhaustion, loss of antigen protein expression and absence of antigen presentation. Tumor-extrinsic factors include absence of T cells with tumor antigen-specific T cell receptors (TCRs) and presence of immunosuppressive cells such as regulatory T cells (Tregs), myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs). A few comprehensive reviews on resistance mechanisms of immunotherapy can be found in recent publications [17, 20, 115].

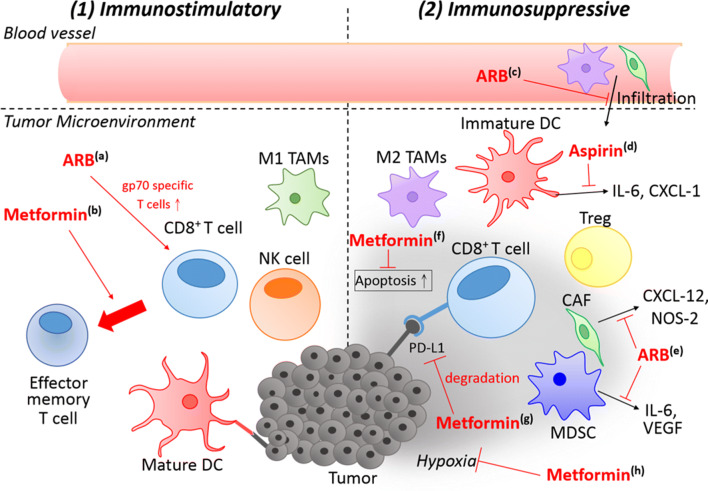

It should be noted that immunotherapy use in CRC is still a highly unexplored area. Not until 2017 and 2018, respectively, were anti-PD1 and anti-CTLA4 therapy granted with FDA approval to treat MSI-H/dMMR CRC. Limited preclinical studies are present to study resistance circumvention in a context specified for CRC, or tumors with proficient mismatch repair (pMMR). Some drug repurposing attempts in other cancer types, namely melanoma and NSCLC, are also reviewed below. Although these studies do not confirm the efficacy of such attempts on CRC populations, they do shed lights on the possible directions to combat immunotherapy resistance in CRC patients. The mechanism of action of the various repurposed drugs in overcoming resistance to immunotherapy is summarized in Table 3 and Fig. 1.

Table 3.

Preclinical animal studies that evaluate efficacy of introducing repurposed drug to immunotherapy

| Repurposed drug | Animal model | Findings | Putative mechanism(s) | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin | Mice bearing colorectal CT26 tumor cells | Combination of anti-PD1 and aspirin caused rapid and complete tumor shrinkage in 30% of mice, while anti-PD1 shows little efficacy | Abolished cancer-promoting inflammatory microenvironment and elicited anticancer immune response by: inhibiting production of pro-inflammatory mediators such as IL-6, CXCL-1 and G-CSF; enhancing Type 1 IFN signaling | [118] |

| Celecoxib | Apc(Min/+) mice | Celecoxib reduced the size and number of polyps | Enhanced T cells and natural killer cells to produce IFN-γ, changing TAMs from M2 to M1 phenotype | [123] |

| Metformin | Mice bearing B16 and M38 tumor cells | Combination of anti-PD1 and metformin enhanced T cell function and tumor regression, while metformin monotherapy has little efficacy | Remodeled the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment by inhibiting mitochondrial complex I, oxygen consumption of tumor cells and reducing intramural hypoxia | [127] |

| Metformin | Mice bearing leukemia RLmale1/intestinal carcinoma Colon 26/renal carcinoma Renca/breast cancer 4T1 and B6 mice bearing B16 melanoma MO5/non-small cell lung cancer 3LL tumor cells | Metformin prevented immune exhaustion, restored multifunctionality CD8+ TILs and induced memory immune response of tumor rejection | Increased number of CD8+ TILs and protects CD8+ TILs from apoptosis induced multifunctional CD8 + TEM phenotype in PD-1− Tim-3+ subset | 128 |

| Metformin | Mice bearing breast cancer 4T1 cells/melanoma B16F10 cells/colorectal cancer CT26 cells | Combination of metformin and anti-CTLA4 synergistically increased number and enhanced activity of CD8+ TILs, thus suppressing tumor growth | Glycosylated PD-L1 and promoted PD-L1 degradation by endoplasmic reticulum via AMPK activation | [129] |

| Candesartan | Breast cancer 4T1 and colorectal cancer CT26 syngeneic tumor mouse models | Angiotensin II signal blockade using candesartan sensitized tumor to immune checkpoint inhibitors (anti-PD1 and anti-CTLA4) | Destroyed the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment by inhibiting infiltration of CAF and M2 TAMs | [133] |

| Valsartan | Mice bearing colon cancer MC38/CT26 tumor cells | Combination of valsartan and anti-PD1 induced a CD8+ T cell-mediated antitumor immune response, while ARB and anti-PD1 monotherapy showed little efficacy | Enhanced tumor antigen gp70 specific T cells while the number of infiltrating T cells is unchanged decreased production of immunosuppressive factors in CD11b+ cells (e.g., IL-6, VEGF) and in CAF (e.g., CXCL12, NOS-2) | [134] |

Anti-CTLA4 anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4, APC(Min/+) adenomatous polyposis coli gene (multiple intestinal neoplasia-positive), ARB angiotensin II receptor blocker, CAF caner-associated fibroblasts, CXCL chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand, G-CSF granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, gp70 an envelope protein of an endogenous ecotropic murine leukemia virus, IFN interferon, IL-6 interleukin 6, NOS-2 nitric oxide synthase-2, PD1 programmed cell death protein 1, TAM tumor-associated macrophage, TEM effector memory T cells, TIL tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes, Tim-3 T cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3

Fig. 1.

Overview of the mechanisms of repurposed drugs to combat resistance to immunotherapy. Repurposed drugs act by either (1) exerting immunostimulatory activities or (2) abolishing immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. (1) a Valsartan (ARB) increases the population of gp70-specific T cells, but does not increase the total number of T cells. b Metformin induces TEM phenotype, which is responsible for the memory response of tumor injection. These actions stimulate the immune attack against tumor cells and eradicate them. (2) c ARB inhibits infiltration of immunosuppressive CAF and M2 TAMs. d Aspirin inhibits the production of immunosuppressive factors such as IL-6 and CXCL-1 from dendritic cells and macrophages. e ARB inhibits the production of immunosuppressive factors in MDSC (e.g., IL-6 and VEGF) and CAF (e.g., CXCL-12 and NOS-2). Metformin exerts multiple actions to remodel the tumor microenvironment, including f protection of CD8+ T cells from apoptosis, g degradation of PD-L1 and h reduction of intratumoral hypoxia, and, which collectively preserve functionality of antitumor immune cells and reverse the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment

NSAIDs

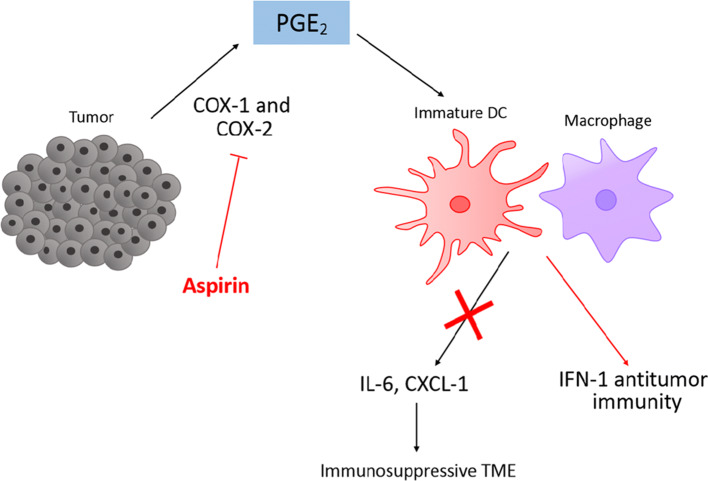

PGE2, one of the COX-catalyzing products, subverts the generation of T helper 1 (Th1) to a T helper 2 (Th2) profile, thereby inhibiting cytotoxic T cell formation and promoting cancer proliferation. PGE2 also suppresses tumor antigen-presenting dendritic cells and inhibits T cell activation [116]. Furthermore, PGE2 promotes propagation of immunosuppressive Tregs, MDSC and M2 macrophage populations [117]. Given the significance of PG or COX in conferring immunotherapy resistance, COX inhibitors/NSAIDs have been proposed to sensitize cancer cells to immunotherapy (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Mechanisms of aspirin to combat immunotherapy resistance. Aspirin inhibits cyclooxygenase (COX) enzyme and synthesis of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). This inhibits the release of immunosuppressive factors, e.g., IL-6, CXCL-1, from immune infiltrates such as macrophages and dendritic cells, thus reversing the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME). IFN-1 antitumor immunity is also enhanced

Downregulated COX-2 expression in human tumor biopsies is associated with decreased level of tumor-promoting inflammatory mediators IL-6, G-CSF and CXCL1, increased level of CXCL9 and CXCL10 (which promotes CD8+ T cell infiltration) and enhanced interferon signaling [118]. Alterations of these inflammatory mediators and signaling are all implicated in overcoming immune checkpoint blockade resistance [119–122].

A combination of aspirin and anti-PD1 monoclonal antibody was found to give rise to synergistic antitumor immune response and induce a more rapid tumor eradication than anti-PD1 monotherapy in mice bearing a CT26 colorectal tumor [118]. Celecoxib, a COX-2 inhibitor, was also showed to promote the conversion of TAM phenotype from immunosuppressive M2 to tumoricidal M1, which is another potential mechanism to combat immunotherapy resistance [123]. Another preclinical study has demonstrated that inhibition of COX and reduction of PGE2 level shrank MDSC population and resensitized tumor cells to both anti-PD1 and oncolytic viral therapy, thus further confirming the key role of the COX/PGE2 pathway in immunosuppression and development of immunotherapy resistance. However, in this study, the reduction in PGE2 levels capable of reducing MDSC was only achievable by forced expression of hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase (15-PGDH), but not by the clinically used NSAID (celecoxib) [124].

Of note, adjuvant use of NSAIDs in CRC patients may only benefit a subset of patient population and identification of a predictive biomarker for patient selection would be critical. A large prospective cohort study has investigated the association of aspirin use with survival in CRC patients. Interestingly, aspirin use is reported to have a stronger association with improved survival in tumor with low PD-L1 expression [125]. This observation suggested that PD-L1 may be used as a potential biomarker to select patients for adjuvant aspirin therapy. It also advocated the combination therapy of aspirin/NSAIDs and ICI therapy to improve clinical outcomes.

Recent clinical trials are also attempting to combine aspirin with anti-CTLA4 or anti-PD1 therapy in several cancer types and they are still at the recruiting stage (NCT03245489 and NCT03396952). Although currently there is no similar trial design for MSI-H/dMMR CRC patients, these ongoing trials will shed lights on CRC treatment approaches, given the common feature of COX-2 and PGE2 overexpression in colorectal carcinoma [40].

Metformin

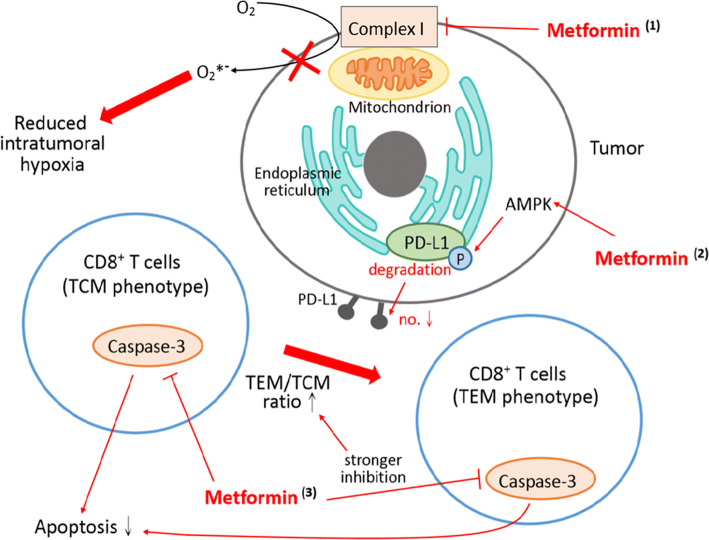

Metformin is another potential agent to be combined with immunotherapy to enhance antitumor immune response via regulating the hypoxic tumor microenvironment (Fig. 3). Intratumoral hypoxia allows infiltration of immunosuppressive cells (including MDSC, TAMs, and Tregs), decreases proliferation and differentiation of cytotoxic T cells, promotes stem cell-like phenotype that is resistant CD8+ T cell-mediated lysis and induces EMT. These factors are all responsible to the dampening of cell-mediated immune response and resistance to immunotherapy [126]. Acting as a mitochondrial complex I inhibitor, metformin inhibits tumor cell oxygen consumption and reduces intramural hypoxia. Although metformin alone shows little effect in reducing tumor burden in aggressive tumors, a combination of metformin and anti-PD1 blockade results in enhanced T cell function, hence promoting tumor clearance and regression [127].

Fig. 3.

Mechanisms of metformin in combating immunotherapy resistance. (1) Metformin inhibits mitochondrial complex I and reduces oxygen consumption, thus reversing intratumoral hypoxia. (2) Metformin inhibits caspase-3 in CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) and protects them from apoptosis (probably mediated through the AMPK/mTOR pathway). The inhibitory effect is stronger in effective memory T cells (TEM) phenotype, leading to a shift of central memory T cells (TCM) to TEM phenotype in PD-1− Tim-3+ subset. (3) Metformin activates AMP-activated protein kinases (AMPK). AMPK phosphorylates PD-L1 and induces glycosylation of PD-L1, leading to endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD) of PD-L1 and reduced PD-L1 level

Metformin also enhances immunity by restoring immune exhaustion. Upon continuous TCR stimulation, CD8+ T cells gradually lose the capability of secreting cytokines such as IL-2 and TNFα and start to die by apoptosis. This process is known as immune exhaustion and it downregulates antitumor immune response. Metformin has been reported to suppress apoptosis of CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) and increase the population of CD8+ TILs, rescuing them from exhaustion. Interestingly, metformin also induces effector memory T cell (TEM) phenotype in CD8+ TILs expressing exhaustion marker Tim-3, thus restoring the multifunctionality of TEM and resulting in immunological memory response of tumor rejection [128].

Recent research has also reported metformin’s direct interaction with the PD-L1/PD-1 axis and interference with CTL immunity. By activating AMPK, metformin directly phosphorylates S195 of PD-L1, leading to aberrant glycosylation and subsequent degradation in endoplasmic reticulum. This suggests that the metformin/CTLA-4 combination may achieve dual blockade and prevent immune escape [129]. This might provide an economical, tolerable and efficacious option other than the current approach of anti-PD1/anti-CTLA4 combination.

The successful preclinical data has triggered several clinical trials to investigate the efficacy of a combination of metformin and immunotherapy treatment. In metastatic malignant melanoma patients, a combination of metformin with ICI showed an improved objective response rate, disease control rate, median PFS and OS, though without statistical significance [130]. Other ongoing clinical trials include nivolumab–metformin combination in NSCLC patients (UMIN registration number: 000028405 [131] and ClinicalTrial.gov registration number: NCT03048500), and pembrolizumab–metformin combination in advanced melanoma patients (NCT03311308). Further studies are needed to explore the use of metformin in CRC patients.

Renin–angiotensin system inhibitors

Renin–angiotensin system is a hormone system regulating blood pressure and fluid balance. When the kidney senses a reduced renal blood flow, renin is released into the circulation and eventually leads to the production of angiotensin II, which induces vasoconstriction and fluid retention. Drugs that target the system, namely angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB), are used to treat cardiovascular disorders such as hypertension and congestive heart failure.

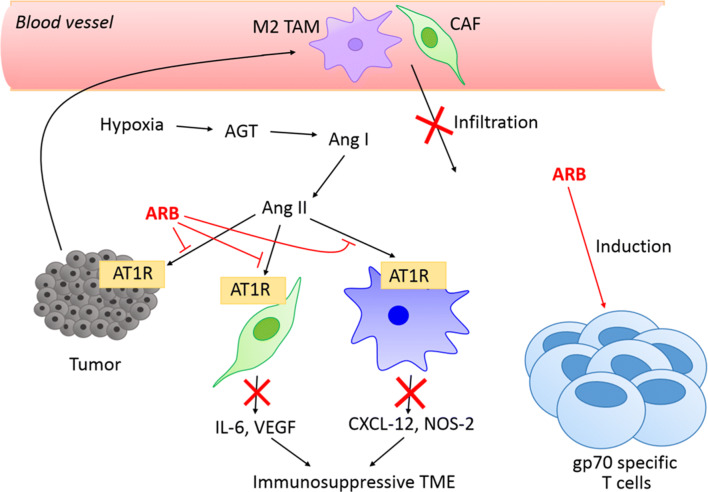

Recent findings suggest that the angiotensin II/AT1 receptor axis produces an immunosuppressive and desmoplastic tumor microenvironment, promotes angiogenesis and induces cancer-related inflammation. The use of the renin–angiotensin system inhibitors is thus hypothesized to reprogram tumor microenvironment and overcome resistance to immunotherapy [132] (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Mechanisms of angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) in combating resistance. The expression of angiotensinogen (AGT) is enhanced in the hypoxic tumor microenvironment. Angiotensinogen is then converted to angiotensin I (Ang I), and further to angiotensin II (Ang II). By inhibiting the binding of angiotensin II to angiotensin type 1 receptors (AT1R), ARB inhibits the infiltration of M2 tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and cancer-associated fibroblast (CAF). ARB also inhibits the production of IL-6 and VEGF in myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC) (CD11b+ cells), as well as CXCL-12 and NOS-2 in CAF. Decreased level of these immunosuppressive factors abolishes the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME)

As shown in a murine CRC model (CT26), angiotensin II is produced locally by hypoxic tumor cells and it creates an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment by inducing infiltration of fibroblasts and other inflammatory cells. This allows immune escape of tumor cells and thus resistance to immunotherapy. A clinically available ARB (candesartan) has been shown to block angiotensin II signaling to destroy such tumor microenvironment and promote infiltration of CD8+ T cells [133], subsequently enhancing antitumor immune response and sensitivity to checkpoint immunotherapy [133]. Consistent results were also observed in another study. Valsartan, another commonly used ARB, was shown to decrease the production of immunosuppressive factors, such as IL-6 and VEGF in CD11b+ cells (namely MDSC and macrophages). It also reduced the expression of CXCL12 and nitric oxide synthase 2 (NOS-2) in cancer-associated fibroblast, thereby augmenting antitumor immune response. In mice bearing murine colon cell line MC38, a combination of valsartan and anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody was found to abrogate the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment and enhance CD8+ T cell-mediated antitumor response [134].

Other considerations in adopting drug repurposing strategy

Drug repurposing approach is a seemingly a promising strategy to combat drug resistance with its good efficacy and safety profile. Nevertheless, a few factors should be considered while adopting this approach. In the era of personalized medicine, the identification of a biomarker is critical for patient selection to receive the therapy. As evidenced by the results of clinical trials discussed above, the efficacy of most drug repurposing approaches may only be demonstrated in a subset of patients. Patients with certain characteristics may also receive additional benefits. In fact, many clinical trials which attempt to combine repurposed drug and anticancer agents have failed, probably owing to lack of a biomarker to identify suitable patients. This would require more extensive and follow-up mechanistic studies, as well as prospective clinical studies, for further exploration.

In addition, researchers should also keep an eye on the potential drug–drug interaction. Even though the repurposed drugs are deemed to be safe, there are still risks of developing serious adverse side effects, for example rhabdomyolysis in statin use. It is possible that pharmacokinetic and/or pharmacodynamic interactions between anticancer agent and repurposed drug may give rise to unexpected toxicity. Although there is no report of any significant unexpected toxicity in current clinical trial attempts, the possibility should not be overlooked in future clinical trials.

Conclusion

The emergence of novel molecular targeted therapy and immunotherapy provides alternative therapeutic options for CRC patients apart from classical cytotoxic therapy. Nevertheless, drug resistance remains a tremendous challenge that limits therapeutic efficacy. Being economical, safe and efficacious, drug repurposing approach is a potential strategy that may be highly cost-effective to combat resistance in clinics. However, some promising preclinical findings are not necessarily translated into an equally successful clinical trial. This would require a more comprehensive understanding on tumor characteristics and oncogenic gene signatures to improve the study design in the future. On the other hand, some novel therapies, especially those in the immunotherapy era, are still left with a relatively blank area and are yet to be investigated. Further preclinical and clinical studies are warranted to enhance our understanding of resistance mechanisms as well as the combating strategies.

Acknowledgements

The authors’ team was supported by the Health and Medical Research Fund [Food and Health Bureau, Hong Kong SAR, grant number 03140276] and a research grant from the Medicine Panel of the Chinese University of Hong Kong [Direct Grant for Research 4054371].

Abbreviations

- ARB

Angiotensin II receptor blockers

- CAF

Cancer-associated fibroblast

- CXCL-12

Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 12

- DC

Dendritic cells

- gp70

An envelope protein of an endogenous ecotropic murine leukemia virus

- IL-6

Interleukin 6

- IFN-γ

Interferon-gamma

- MDSC

Myeloid-derived suppressing cells

- NK cells

Natural killer cells

- NOS-2

Nitric oxide synthase 2

- TAM

Tumor-associated macrophages

- TEM

Effector memory T cells

- Treg

Regulatory T cells

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnold M, Sierra MS, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global patterns and trends in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. Gut. 2016;66:683–691. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cunningham D, Atkin W, Lenz HJ, et al. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2010;375:1030–1047. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60353-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Labianca R, Nordlinger B, Beretta GD, et al. Early colon cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:64–72. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benson AB, 3rd, Venook AP, Al-Hawary MM, et al. Rectal cancer, version 2.2018, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16:874–901. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2018.0061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benson AB, 3rd, Venook AP, Cederquist L, et al. Colon cancer, version 1.2017, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15:370–398. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shinagawa T, Tanaka T, Nozawa H, et al. Comparison of the guidelines for colorectal cancer in Japan, the USA and Europe. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2017;2:6–12. doi: 10.1002/ags3.12047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hammond WA, Swaika A, Mody K. Pharmacologic resistance in colorectal cancer: a review. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2016;8:57–84. doi: 10.1177/1758834015614530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ng K, Zhu AX. Targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor in metastatic colorectal cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;65:8–20. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pabla B, Bissonnette M, Konda VJ. Colon cancer and the epidermal growth factor receptor: current treatment paradigms, the importance of diet, and the role of chemoprevention. World J Clin Oncol. 2015;6:133–141. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v6.i5.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miyamoto Y, Suyama K, Baba H. Recent advances in targeting the EGFR signaling pathway for the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:752. doi: 10.3390/ijms18040752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Cutsem E, Cervantes A, Nordlinger B, Arnold D. ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Metastatic colorectal cancer ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:1–9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu260. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fan F, Wey JS, McCarty MF, et al. Expression and function of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 on human colorectal cancer cells. Oncogene. 2005;24:2647–2653. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun W. Angiogenesis in metastatic colorectal cancer and the benefits of targeted therapy. J Hematol Oncol. 2012;5:63. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-5-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalyan A, Kircher S, Shah H, Mulcahy M, Benson A. Updates on immunotherapy for colorectal cancer. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2018;9:160–169. doi: 10.21037/jgo.2018.01.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Granier C, De Guillebon E, Blanc C, et al. Mechanisms of action and rationale for the use of checkpoint inhibitors in cancer. ESMO Open. 2017;2:e000213. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2017-000213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jenkins RW, Barbie DA, Flaherty KT. Mechanisms of resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Br J Cancer. 2018;118:9–16. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martini G, Troiani T, Cardone C, et al. Present and future of metastatic colorectal cancer treatment: a review of new candidate targets. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:4675–4688. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i26.4675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tampellini M, Sonetto C, Scagliotti GV. Novel anti-angiogenic therapeutic strategies in colorectal cancer. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2016;25:507–520. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2016.1161754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma P, Hu-Lieskovan S, Wargo JA, Ribas A. Primary, adaptive, and acquired resistance to cancer immunotherapy. Cell. 2017;168:707–723. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li W, Zhang H, Assaraf YG, et al. Overcoming ABC transporter-mediated multidrug resistance: molecular mechanisms and novel therapeutic drug strategies. Drug Resist Updat. 2016;27:14–29. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao B, Wang L, Qiu H, et al. Mechanisms of resistance to anti-EGFR therapy in colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:3980–4000. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de la Cueva A, Ramírez de Molina A, Alvarez-Ayerza N, et al. Combined 5-FU and ChoKα inhibitors as a new alternative therapy of colorectal cancer: evidence in human tumor-derived cell lines and mouse xenografts. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64961. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mazard T, Causse A, Simony J, et al. Sorafenib overcomes irinotecan resistance in colorectal cancer by inhibiting the ABCG2 drug-efflux pump. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12:2121–2134. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang L, Bernards R. Taking advantage of drug resistance, a new approach in the war on cancer. Front Med. 2018;12:490–495. doi: 10.1007/s11684-018-0647-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hernandez JJ, Pryszlak M, Smith L, et al. Giving drugs a second chance: overcoming regulatory and financial hurdles in repurposing approved drugs as cancer therapeutics. Front Oncol. 2017;7:273. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2017.00273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pushpakom S, Iorio F, Eyers PA, et al. Drug repurposing: progress, challenges and recommendations. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018;5:10. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2018.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu T, Li Z, Gao CY, Cao CH. Mechanisms of drug resistance in colon cancer and its therapeutic strategies. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:6876–6889. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i30.6876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dalton WS, Crowley JJ, Salmon SS, et al. A phase III randomized study of oral verapamil as a chemosensitizer to reverse drug resistance in patients with refractory myeloma. A Southwest Oncology Group study. Cancer. 1995;75:815–820. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950201)75:3<815::AID-CNCR1>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pennock GD, Dalton WS, Roeske WR, et al. Systemic toxic effects associated with high-dose verapamil infusion and chemotherapy administration. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1991;83(2):105–110. doi: 10.1093/jnci/83.2.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sonneveld P, Schoester M, de Leeuw K. Clinical modulation of multidrug resistance in multiple myeloma: effect of cyclosporine on resistant tumor cells. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:1584–1591. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.8.1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murren JR, Durivage HJ, Buzaid AC, et al. Trifluoperazine as a modulator of multidrug resistance in refractory breast cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1996;38:65–70. doi: 10.1007/s002800050449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kathawala RJ, Gupta P, Ashby CR, Jr, Chen ZS. The modulation of ABC transporter-mediated multidrug resistance in cancer: a review of the past decade. Drug Resist Updat. 2015;18:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baer MR, George SL, Dodge RK, et al. Phase 3 study of the multidrug resistance modulator PSC-833 in previously untreated patients 60 years of age and older with acute myeloid leukemia: cancer and Leukemia Group B Study 9720. Blood. 2002;100:1224–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tamaki A, Ierano C, Szakacs G, Robey RW, Bates SE. The controversial role of ABC transporters in clinical oncology. Essays Biochem. 2011;50:209–232. doi: 10.1042/bse0500209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shi Z, Tiwari AK, Shukla S, et al. Sildenafil reverses ABCB1- and ABCG2-mediated chemotherapeutic drug resistance. Cancer Res. 2011;71:3029–3041. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen JJ, Sun YL, Tiwari AK, et al. PDE5 inhibitors, sildenafil and vardenafil, reverse multidrug resistance by inhibiting the efflux function of multidrug resistance protein 7 (ATP-binding Cassette C10) transporter. Cancer Sci. 2012;103:1531–1537. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2012.02328.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goard CA, Mather RG, Vinepal B, et al. Differential interactions between statins and P-glycoprotein: implications for exploiting statins as anticancer agents. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2936–2948. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang L, Wang C, Zheng W, Liu R, Yang J, Tang C. Effects of celecoxib on the reversal of multidrug resistance in human gastric carcinoma by downregulation of the expression and activity of P-glycoprotein. Anticancer Drugs. 2007;18(9):1075–1080. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e3281c49d7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rahman M, Selvarajan K, Hasan MR, et al. Inhibition of COX-2 in colon cancer modulates tumor growth and MDR-1 expression to enhance tumor regression in therapy-refractory cancers in vivo. Neoplasia. 2012;14:624–633. doi: 10.1593/neo.12486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang D, DuBois RN. The role of COX-2 in intestinal inflammation and colorectal cancer. Oncogene. 2010;29:781–788. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patel VA, Dunn MJ, Sorokin A. Regulation of MDR-1 (P-glycoprotein) by cyclooxygenase-2. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:38915–38920. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206855200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rana C, Piplani H, Vaish V, Nehru B, Sanyal SN. Downregulation of PI3-K/Akt/PTEN pathway and activation of mitochondrial intrinsic apoptosis by Diclofenac and Curcumin in colon cancer. Mol Cell Biochem. 2015;402:225–241. doi: 10.1007/s11010-015-2330-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moon CM, Kwon JH, Kim JS, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs suppress cancer stem cells via inhibiting PTGS2 (cyclooxygenase 2) and NOTCH/HES1 and activating PPARG in colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2014;134:519–529. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gasparini G, Gattuso D, Morabito A, et al. Combined therapy with weekly irinotecan, infusional 5-fluorouracil and the selective COX-2 inhibitor rofecoxib is a safe and effective second-line treatment in metastatic colorectal cancer. Oncologist. 2005;10:710–717. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.10-9-710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ng K, Meyerhardt JA, Chan AT, et al. Aspirin and COX-2 inhibitor use in patients with stage III colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;107:345. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.El-Rayes BF, Zalupski MM, Manza SG, et al. Phase-II study of dose attenuated schedule of irinotecan, capecitabine, and celecoxib in advanced colorectal cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008;61:283–289. doi: 10.1007/s00280-007-0472-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen EY, Blanke CD, Haller DG, et al. A phase II study of celecoxib with irinotecan, 5-fluorouracil, and leucovorin in patients with previously untreated advanced or metastatic colorectal cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2018;41:1193–1198. doi: 10.1097/COC.0000000000000465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang Y, Guan M, Zheng Z, Zhang Q, Gao F, Xue Y. Effects of metformin on CD133 + colorectal cancer cells in diabetic patients. PLoS One. 2013;8:e81264. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nangia-Makker P, Yu Y, Vasudevan A, et al. Metformin: a potential therapeutic agent for recurrent colon cancer. PLoS One. 2014;9:e84369. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim SH, Kim SC, Ku JL. Metformin increases chemo-sensitivity via gene downregulation encoding DNA replication proteins in 5-Fu resistant colorectal cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2017;8:56546–56557. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Skinner HD, Crane CH, Garrett CR, et al. Metformin use and improved response to therapy in rectal cancer. Cancer Med. 2013;2:99–107. doi: 10.1002/cam4.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Singh PP, Shi Q, Foster NR, et al. Relationship between metformin use and recurrence and survival in patients with resected stage III colon cancer receiving adjuvant chemotherapy: results from north central cancer treatment group N0147 (Alliance) Oncologist. 2016;21:1509–1521. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bragagnoli A, Araujo R, Abdalla K, et al. Final results of a phase II of metformin plus irinotecan for refractory colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:e15527–e15528. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.e15527. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miranda VC, Braghiroli MI, Faria LD, et al. Phase 2 trial of metformin combined with 5-fluorouracil in patients with refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2016;15:321–328. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2016.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jang HJ, Hong EM, Jang J, et al. Synergistic effects of simvastatin and irinotecan against colon cancer cells with or without irinotecan resistance. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016;2016:7891374. doi: 10.1155/2016/7891374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kodach LL, Jacobs RJ, Voorneveld PW, et al. Statins augment the chemosensitivity of colorectal cancer cells inducing epigenetic reprogramming and reducing colorectal cancer cell ‘stemness’ via the bone morphogenetic protein pathway. Gut. 2011;60:1544–1553. doi: 10.1136/gut.2011.237495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang W, Collie-Duguid E, Cassidy J. Cerivastatin enhances the cytotoxicity of 5-fluorouracil on chemosensitive and resistant colorectal cancer cell lines. FEBS Lett. 2002;531:415–420. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)03575-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jover R, Nguyen TP, Pérez-Carbonell L, et al. 5-Fluorouracil adjuvant chemotherapy does not increase survival in patients with CpG island methylator phenotype colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1174–1181. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yuan J, Yin Z, Tao K, Wang G, Gao J. Function of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor in cancer resistance to chemotherapy. Oncol Lett. 2018;15:41–47. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.7276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jang HJ, Hong EM, Park SW, et al. Statin induces apoptosis of human colon cancer cells and downregulation of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor via proapoptotic ERK activation. Oncol Lett. 2016;12:250–256. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.4569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ng K, Ogino S, Meyerhardt JA, et al. Relationship between statin use and colon cancer recurrence and survival: results from CALGB 89803. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:1540–1551. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lim SH, Kim TW, Hong YS, et al. A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled multi-centre phase III trial of XELIRI/FOLFIRI plus simvastatin for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2015;113:1421–1426. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Abdullah MI, de Wolf E, Jawad MJ, Richardson A. The poor design of clinical trials of statins in oncology may explain their failure–lessons for drug repurposing. Cancer Treat Rev. 2018;69:84–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2018.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Park D, Lee Y. Biphasic activity of chloroquine in human colorectal cancer cells. Dev Reprod. 2014;18:225–231. doi: 10.12717/devrep.2014.18.4.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sasaki K, Tsuno NH, Sunami E, et al. Chloroquine potentiates the anti-cancer effect of 5-fluorouracil on colon cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:370. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Du B, Guo Y, Jin L, Xiong M, Liu D, Xi X. Targeting autophagy promote the 5-fluorouracil induced apoptosis in human colon cancer cells. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2017;10:6071–6081. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Selvakumaran M, Amaravadi RK, Vasilevskaya IA, O’Dwyer PJ. Autophagy inhibition sensitizes colon cancer cells to antiangiogenic and cytotoxic therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(11):2995–3007. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sasaki K, Tsuno NH, Sunami E, et al. Resistance of colon cancer to 5-fluorouracil may be overcome by combination with chloroquine, an in vivo study. Anticancer Drugs. 2012;23:675–682. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e328353f8c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]