Abstract

Objective:

To examine the construct validity of Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data (RAPID3) and Psoriatic Arthritis Impact of Disease (PSAID) in patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA). In examining construct validity, we also addressed scores among subgroups with severe psoriasis, polyarticular disease, enthesitis and dactylitis and evaluated influences of sociodemographic factors and comorbidities (contextual factors) on these patient-reported outcomes (PROs).

Methods:

Patients with PsA were enrolled in the Psoriatic Arthritis Research Consortium (PARC) between 2014-2016. PARC is a longitudinal observational cohort study conducted at four United States institutions. In this cross-sectional study, construct validity was assessed by examining Spearman’s correlation coefficients for RAPID3 and PSAID with physician-reported disease activity measures and other PROs (e.g., Short Form 12 (SF12-PCS/-MCS), Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT)-Fatigue). Contextual factors and disease subgroups were assessed in multivariable linear regression models with RAPID3 or PSAID12 as outcomes of interest and the hypothesized contextual factors as covariates.

Results:

Among 401 patients enrolled in PARC, 347 completed RAPID3 or PSAID12. Of these, most were Caucasian females with a mean age of 51.74 (SD 14.02). RAPID3 and PSAID were highly correlated (r=0.90). These measures were also correlated with the SF12-PCS (r=−0.67) and FACIT-Fatigue (r=−0.77). Important contextual factors and disease subgroups included enthesitis, joint counts, education, insurance type, and depression.

Conclusion:

RAPID3 and PSAID12 have excellent construct validity in PsA and are strongly correlated despite differing items. Contextual factors (i.e., the presence of depression and obesity) should be considered when interpreting raw scores of the RAPID3 and PSAID12.

Keywords: Patient Reported Outcomes, Psoriatic arthritis

Introduction

Understanding patient perceptions of health and function are necessary for optimizing clinical decision-making. Patient reported outcomes (PROs) provide valuable insights into patients’ perceptions of their disease and individual priorities for improvements. PROs also communicate information that may be difficult to ascertain with standard provider assessments, particularly with heterogeneous diseases such as psoriatic arthritis (PsA). Since patient perceptions of health are important targets for intervention, it is necessary to select and understand appropriate PROs for assessments of PsA.(1, 2) Selection of PROs for PsA is challenging. There are a large number of available PROs measuring overlapping, but distinct aspects of disease. Time and resources for both patients and clinicians limit the number of PROs that can be included in studies and daily clinical practice. Furthermore, when too many PROs are required from patients, questionnaire fatigue erodes the quality of data.(3)

For the purposes of clinical practice and longitudinal cohort studies, several PROs are attractive for various reasons. The Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data (RAPID3) is appealing because it is widely recognized and feasible and is largely considered to be the most commonly used PRO in the US across inflammatory diseases.(4-6) Furthermore, RAPID3 has been validated as a measure of disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis (RA), ankylosing spondylitis (AS), and more recently PsA.(7-11) This means RAPID3 can be useful when comparing between inflammatory arthritis subsets, studying multiple types of inflammatory arthritis in aggregate, and seeing patients with varied diagnoses in a single clinic session. Unlike the RAPID3, initially designed for patients with RA, the Psoriatic Arthritis Impact of Disease (PSAID) questionnaire was specifically developed for PsA by patients with PsA and each question is specifically attributed to PsA (i.e., each item, such as fatigue is followed by the words “due to your PsA”)(12-14). It was designed to broadly measure the impact of disease on diverse aspects of patients’ lives and has also been shown to correlate strongly with disease activity measures, such as Disease Activity in PSoriatic Arthritis (DAPSA)(15), and disease activity cut-off scores have been established including a Patient Acceptable Symptom State (PASS).(12) Furthermore, a principal component analysis identified a subset of questions within the PSAID12 that represented the impact of cutaneous psoriasis. Both RAPID3 and PSAID12 are amongst the most feasible PROs and are widely used and accepted by patients and researchers.(16, 17) Many other PROs also exist; most of these more narrowly measure concepts such as fatigue or work productivity, or broadly measure health-related quality of life (HRQoL).(4)

While RAPID3 and PSAID performed well in PsA overall, there are several common demographic and comorbid factors that influence PROs. In general, women with PsA report higher self-assessed disease activity scores compared to men.(18-22) Additionally, obesity has also been associated with less favorable PROs in axial spondyloarthritis patients.(23-26) The influence of contextual factors, such as sociodemographics and comorbidities, on PROs is not well understood in PsA.(22, 27-29) To inform PRO selection and interpretation, the objectives of this study were to: a) characterize the construct validity of RAPID3 and PSAID in the general PsA population and in subsets with, polyarticular disease (4 or more active joints), enthesitis and dactylitis; and 2) evaluate influences of common sociodemographic factors and comorbidities on these two PROs.

Patients and Methods

Study Design: Cross-sectional observational study

Patients and Study Population:

Psoriatic Arthritis Research Consortium (PARC) is a longitudinal observational cohort study that includes four institutions in the United States: University of Pennsylvania (Penn Psoriatic Arthritis Program), Cleveland Clinic (Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Center), New York University (Psoriatic Arthritis Center), and University of Utah (Utah Spondyloarthritis Program). The four centers in PARC standardized data collection and developed a REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) database with a common data model. The study period was 2014 to 2016. Patients were 18 years or older and met CASPAR criteria.(30) Only baseline data is included in this analysis.

Physician-assessed variables collected:

Baseline demographics and social histories were reported by participants included age, sex, race, ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), smoking status (ever vs. never), and current alcohol use (yes/no), highest level of education, insurance type, work status, income level. Additional information obtained by physicians via a history and record review included location of study center, duration of PsA (since diagnosis), and duration of psoriasis (since diagnosis), fulfilment of ASAS criteria for axial spondyloarthritis, inflammatory back pain as defined by ASAS criteria or sacroiliitis as defined by joint imaging ,(31) and comorbidities including presence of obesity (BMI>30 kg/m2), fibromyalgia, concurrent osteoarthritis, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes. Physician examination measures included tender and swollen joint counts (66/68 at three centers and 76/78 at the fourth center), enthesitis count >0 [measured by Leeds Enthesitis Index(32) plus bilateral plantar fascia insertions], dactylitis count > 0, and typical psoriatic nail dystrophy (onycholysis, pitting, hyperkeratosis)(30). Physicians also reported their global assessments for cutaneous psoriasis, arthritis, and overall health. Data were collected at a single timepoint at enrollment in this cross-sectional study. If more than one follow up was available, only the enrollment visit was included.

Patient Reported Outcomes:

All sites collected the RAPID3 (one site collected HAQ-DI, patient pain, and patient global (range 0-10) (33) and these scores were transformed to RAPID3 scores per a previously described algorithm).(34) In addition, three sites collected the short form 12 physical component score (SF-12 PCS); the physical component score on the SF12 is highly correlated with the Short Form 36 PCS used in PsA clinical trials)(35) and two sites additionally collected the PSAID12, the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI), Functional Assessment Of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F), Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), Work Limitations Questionnaire (WLQ), and Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI). Permission from the FACIT owners was obtained for the FACIT-F. Licenses have been obtained for the use of the Short Form (SF)-12 and the WLQ from Optum and Tufts University, respectively. Patients also reported insurance status, work status, education level, smoking, alcohol, and a basic set of comorbidities depression (defined as patient-reported depression or PHQ9>10).

Construct validity - a priori hypotheses:

Construct validity is the ability of an instrument to measure the concepts it attempts to measure.(36) Convergent validity, one aspect of construct validity, is the concept that two measures that should be related to each other are, in fact, related. We believe that both RAPID3 and PSAID are addressing the construct of “disease impact” or how much the disease is affecting the patient’s life at this time. A priori we hypothesized that RAPID3 and PSAID9 and 12 would be strongly correlated (rho 0.8-1.0).(37) Furthermore, we hypothesized that these outcomes would have strong correlations with physical function measures (i.e., SF12-PCS) and other disease impact measures (BASDAI), moderate correlation (rho 0.6-0.8) with fatigue, health related quality of life assessments and work limitations, and moderate correlation with swollen and tender joint counts. While we hypothesized that depression would impact the total score (as a contextual factor), we felt that there would be a low correlation between RAPID3 and SF12-MCS. Additionally, we hypothesized that RAPID3 and PSAID would differentiate well between those with low and high disease activity when stratified by swollen and tender joint counts, enthesitis, and dactylitis (PsA subgroups). Finally, we hypothesized that there would be associations between the RAPID3 and PSAID scores with contextual factors (including obesity, older age, female sex, comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, and depression, and socioeconomic status).(38)

Statistical Analysis:

We first descriptively reported the study population characteristics. We assessed convergent validity by examining the Spearman’s correlation (given a skewed distribution of data) for RAPID3 and PSAID12 with the other PROs and physician reported disease activity measures (as described above). Another form of construct validity is the ability to differentiate between known groups or differing disease states.(39-41) We used swollen joints as a reference standard. We plotted each PRO and the number of swollen joints. We compared the mean score for RAPID3 and PSAID12 among patients with four or more swollen joints vs. three or fewer swollen joints (this cut off was chosen as it is typically used for eligibility into PsA randomized controlled trials).

Contextual factors were explored as confounders. These factors (e.g., demographic or clinical characteristics) result in differential scoring of the questionnaire of interest. A list of hypothesized or potential contextual factors was developed prior to statistical testing which included gender, age (<50 or >=50, according to median split), race, education level, insurance type, work status, depression, obesity, diabetes, or cardiovascular disease. We examined the association between potential contextual factors and RAPID3 and PSAID12 scores by plotting the median RAPID3 and PSAID12 scores by subgroup of the potential contextual factor. We then used univariable linear regression models to identify the statistical association of potential contextual factors with the RAPID3 and subsequently formed multivariable linear regression models in a purposeful selection method (testing only biologically relevant variables and including only those variables significant at the univariable stage in a full model, defined as p<0.05) to determine which factors continued to have an independent relationship with the RAPID3 score when accounting for the other factors in the model. This modeling process was repeated for PSAID12. We used a complete case design in this cross-sectional study.

Ethics Approval:

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained at all four sites: NYU(14-00487), Utah (IRB_00074499), UPenn (PARC-819801; PARC-B- 828357), CCF (IRB 07-623). Patients signed a written consent form prior to enrollment in the study.

Results

Four hundred and one patients were enrolled among the four centers. After excluding patients who did not complete the RAPID3 or PSAID12, 347 patients remained; the cohort is representative of patients with PsA in the United States: 53% female, mean age 51.7 (SD 14.02), and mostly Caucasian (Table 1). The prevalence of obesity and depression in the cohort were 42% and 19% respectively. Other common comorbidities in the cohort were diabetes (10%) and cardiovascular disease (18%). Using RAPID3 categories for disease activity designed for RA, the mean disease activity was “moderate.”(33) The mean PSAID12 score was 3.24 (SD 2.38) and 130 (63%) patients were below the published patient acceptable symptom state of 4.(12)

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics in patients with RAPID3 or PSAID12 data (N=347)*

| Age | Mean (SD) | 51.7 (14.0) |

| Sex | Female (N/%) | 186 (53.6%) |

| Race | White/Caucasian | 300 (86.5%) |

| Black | 6 (1.7%) | |

| Native American | 2 (0.6%) | |

| Asian | 12 (3.5%) | |

| Other | 13 (3.8%) | |

| Unknown | 7 (2.0%) | |

| BMI | Mean (SD) | 29.2 (6.7) |

| Ethnicity | Hispanic | 7 (2.0%) |

| Center | Cleveland Clinic | 91 (26.2%) |

| New York University | 47 (13.5%) | |

| University of Utah | 148 (42.7%) | |

| University of Pennsylvania | 61 (17.6%) | |

| Current Therapies *** | Methotrexate | 114 (32.9%) |

| Leflunomide | 17 (4.9%) | |

| Sulfasalazine | 19 (5.5%) | |

| Apremilast | 14 (4.0%) | |

| Adalimumab | 61 (17.6%) | |

| Etanercept | 67 (19.3%) | |

| Certolizumab | 3 (0.9%) | |

| Golimumab | 9 (2.6%) | |

| Infliximab | 20 (5.8%) | |

| Ustekinumab | 16 (4.6%) | |

| Secukinumab | 2 (0.6%) | |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 6 (1.7%) | |

| Any nbDMARD or bDMARD | 231 (66.6%) | |

| Joint Counts **** | 66 Swollen (Mean (SD)) | 2.2 (3.8) |

| 68 Tender (Mean (SD)) | 4.3 (7.2) | |

| 76 Swollen (Mean (SD)) | 4.5 (11.2) | |

| 78 Tender (Mean (SD)) | 7.3 (12.5) | |

| Physician Global Assessments | Overall | 3.4 (2.2) |

| Arthritis | 3.0 (2.2) | |

| Skin | 2.0 (2.2) | |

| Patient Global ** | Mean (SD) | 3.7 (2.7) |

| Pain Assessment | Mean (SD) | 4.0 (2.8) |

| HAQ score | Mean (SD) | 1.6 (1.7) |

| RAPID3 | Mean (SD) | 8.6 (6.1) |

| PSAID-9 * | Mean (SD) | 3.4 (2.4) |

| PSAID-12 * | Mean (SD) | 3.2 (2.4) |

PSAID was completed by 208 patients; RAPID3 was completed by 341 patients

The global assessments use the 0-10 range and were taken from the RAPID3.

Some patients on concomitant therapy; percentages do not sum up to 100%.

One center only collected the 76/78 joint count

Abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; HAQ = health assessment questionnaire; nbDMARD = non-biologic disease modifying antirheumatic drug; bDMARD = biologic disease modifying antirheumatic drug; RAPID3=Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data, range 0-30; PSAID = PSoriatic Arthritis Impact of Disease questionnaire

RAPID3 and PSAID12 Construct Validity

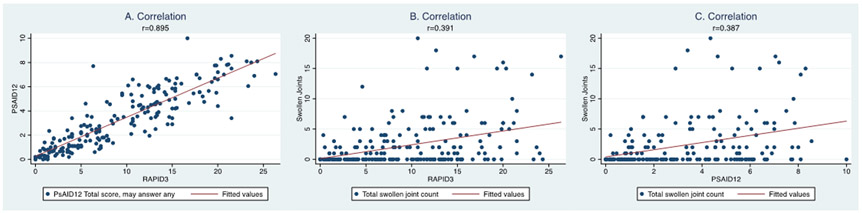

We assessed the correlation among the PROs and with provider assessments (Figure 1, Table 2). The RAPID3 was strongly correlated with the PSAID12 (r=0.90, p<0.001; this was identical for PSAID9; Figure 1). The magnitude of correlation between RAPID3 and the other PROs was similar to the magnitude of correlation between PSAID12 and the other PROs. Specifically, BASDAI strongly correlated with both RAPID3 (R= 0.88) and PSAID12 (R= 0.87). Correlations were also moderate to strong with FACIT-F for RAPID3 (R= − 0.77) and PSAID12 (R= −0.84). Correlations were modest to moderate between RAPID3 and SF-12 PCS, SF-12 MCS, WLQ, Physician Global Assessment, Physician Assessment of Arthritis, Swollen Joint Count, and Tender Joint Count (Range: R= 0.39- 0.67). Similarly, correlations were modest to moderate between PSAID12 and SF-12 PCS, SF-12 MCS, WLQ, Physician Global Assessment, Physician Assessment of Arthritis, Swollen Joint Count, and Tender Joint Count (Range: R= 0.33- 0.73).

Figure 1: Construct Validity: Correlation of RAPID, PSAID, and swollen joint counts.

Correlation among a) RAPID3 and PSAID12, b) RAPID3 and swollen joint count (0-66), and c) between PSAID12 and swollen joint counts (0-66). RAPID3 and PSAID are strongly correlated whereas either measure has only moderate correlation with the swollen joint counts.

Table 2.

Correlation among instruments in a cross-sectional setting.

| N of RAPID3 / instrument |

RAPID3 | PSAID12 | SF-12 PCS | SF-12 MCS | BASDAI | FACIT-F | WLQ | Phys Global | Phys Arth | Swollen Joints | Tender Joints | Pain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSAID12 | 207 | 0.90* | |||||||||||

| PSAID9 | 207 | 0.90* | 1.00* | ||||||||||

| SF-12 PCS | 270 | −0.67* | −0.73* | ||||||||||

| SF-12 MCS | 270 | −0.41* | −0.48* | 0.11 | |||||||||

| BASDAI | 205 | 0.88* | 0.87* | −0.68* | −0.42* | ||||||||

| FACIT-F | 188 | −0.77* | −0.84* | 0.71* | 0.54* | −0.78* | |||||||

| WLQ** | 141 | 0.67* | 0.72* | −0.63* | −0.50* | 0.68* | −0.76* | ||||||

| Phys Global | 304 | 0.63* | 0.63* | −0.50* | −0.26* | 0.56* | −0.48* | 0.45* | |||||

| Phys Arth | 306 | 0.60* | 0.56* | −0.45* | −0.22* | 0.49* | −0.42* | 0.38* | 0.84* | ||||

| SwollenJoints | 231 | 0.39* | 0.39* | −0.28* | −0.17* | 0.34* | −0.26* | 0.25* | 0.54* | 0.68* | |||

| TenderJoints | 231 | 0.42* | 0.37* | −0.33* | −0.15* | 0.35* | −0.28* | 0.29* | 0.55* | 0.63* | 0.77* | ||

| Pain | 344 | 0.94 * | 0.89* | −0.63* | −0.34* | 0.85 | −0.72 | 0.62 | 0.64 | 0.61 | 0.39 | 0.41 | |

| Global | 343 | 0.93 * | 0.83* | −0.62* | −0.42* | 0.81 | −0.72 | 0.64 | 0.56 | 0.55 | 0.35 | 0.38 | 0.83* |

Spearman’s correlation coefficients are shown in this table. Yellow indicates a strong correlation (rho 0.8-1.0) and blue a moderate correlation (0.6-0.79).

p-value <0.05

The productivity score of the Work Limitations Questionnaire is shown here. The WLQ index had nearly identical coefficients.

In Italics: Note that pain and global assessment are part of the RAPID3 so the correlation is expected to be high.

Note that the additional columns with the other outcomes were not part of the original hypotheses.

Additional Abbreviations: RAPID3=Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data 3 ;PSAID12=Psoriatic Arthritis Impact of Disease 12-question version; PSAID9=Psoriatic Arthritis Impact of Disease 9-question version; SF-12 PCS = Short Form 12 Physical Component Score; SF-12 MCS = Short Form 12 Mental Component Score; BASDAI = Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; Phys global and Phys arth refer to the physician global assessments for overall health and arthritis respectively.

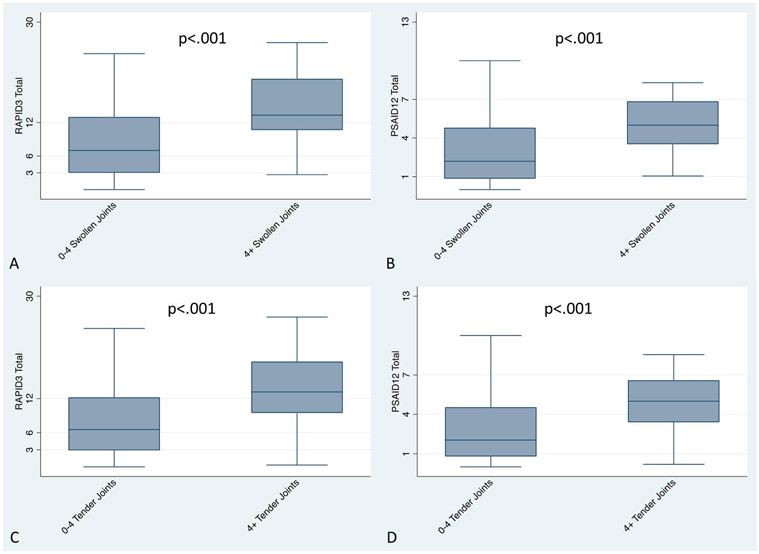

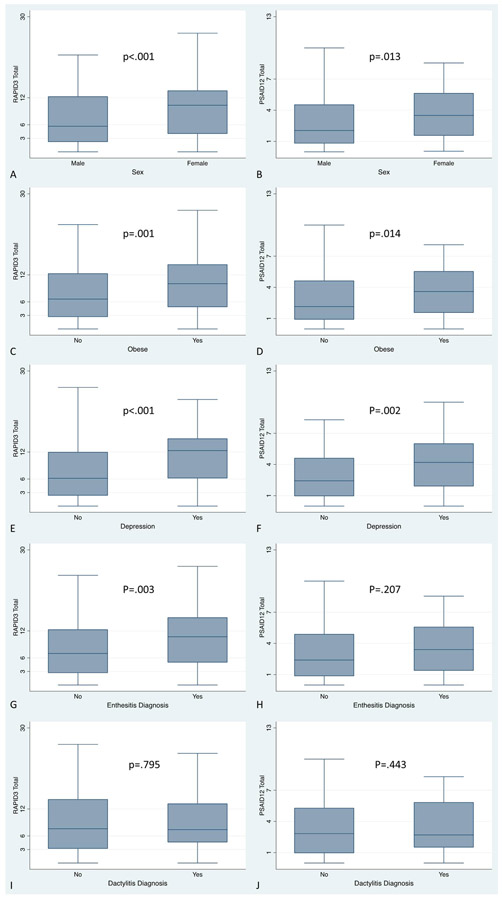

To assess the ability of these measures to distinguish between known groups, we examined a series of different cut points in the swollen joint count. There was a significant difference among those with four or more swollen joints compared to those with three or fewer swollen joints (PSAID12 n=183; RAPID3=231; p-values <0.001) (Figure 2) and similarly a significant difference (p-value <0.001) when we examined 0-1 swollen joints compared to 2 or more. Similarly, RAPID3 was able to differentiate among patients with and without enthesitis on examination (p<0.01, Figure 3); however, PSAID was not significantly different betweenpatients with and without enthesitis.

Figure 2: Known Groups: RAPID3 and PSAID by swollen joint count and by tender joint count.

RAPID3 (a) and PSAID12 (b) scores are significantly different among patients with low disease activity (defined by a swollen joint count <4) compared to those with 4 or more swollen joints, suggesting that these measures differentiate between low and higher disease activity states. RAPID3 (c) and PSAID12 (d) scores are significantly different among patients with low disease activity (defined by a tender joint count <4) compared to those with 4 or more tender joints, suggesting that these measures differentiate between low and higher disease activity states.

Figure 3: RAPID3 and PSAID by known subgroups: Mean RAPID3 and PSAID12 scores, by sex (A, B), obesity (C, D), depression (E, F), enthesitis (G, H), and dactylitis (I, J).

RAPID3 scores are significantly different among sex, obesity, depression, and enthesitis status. PSAID scores are significantly different among sex, obesity, and depression status.

Contextual Factors and PsA subgroups

In Table 3, we present univariable and multivariable associations with the RAPID3 score. Sex, alcohol use, center, BMI, education level, insurance type, swollen joint count, tender joint count, enthesitis count, depression and obesity were significantly associated with the RAPID3 score in univariable models. In a multivariable model, post-graduate education, insurance type, enthesitis, and tender joint count were significantly associated with RAPID3. Sex was no longer significant after accounting for these other factors. Removing it from the model did not change the point estimates nor confidence intervals of the other elements and did not significantly affect the R2-value or Akaike’s information criteria. We also examined univariable and multivariable associations with the PSAID12 in supplemental table 1. In a multivariable model, insurance type, enthesitis, swollen joint count and depression were significantly associated with PSAID12.

Table 3.

Univariable and Multivariable Associations with RAPID3 scores

| Univariable | Multivariable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | n | Beta-coefficient (95%CI) | p-value | Beta-coefficient (95%CI) | p-value |

| Age | 345 | −0.01 (−0.07-0.04) | NS | ||

| Sex | 345 | 2.49 (1.07-3.91) | 0.001 | 1.20 (−0.53-2.93) | 0.17 |

| Race | 339 | REF | |||

| Caucasian | |||||

| Black/African American | 4.69 (−0.76-10.15) | NS | |||

| Native American | 2.16 (−7/23-11.55) | NS | |||

| Asian | −0.03 (−3.92-3.87) | NS | |||

| Hispanic/Latino | 5.94 (0.99-11.00) | 0.02 | |||

| Other | 3.18 (−0.57-6.93) | NS | |||

| Body Mass Index | 343 | 0.19 (0.08-0.29) | <0.001 | ||

| Smokers (ever vs. never) | 274 | 1.22 (−0.42-2.86) | NS | ||

| Alcohol (current use) | 273 | −2.12 (−3.66−-0.58) | 0.007 | ||

| Center | 345 | 0.83 (0.27-1.40) | 0.004 | ||

| Education | 203 | REF | |||

| No college degree | |||||

| College | −2.5 (−4.88−-0.13) | 0.04 | −1.66 (−3.83-0.49) | 0.13 | |

| Post-graduate | −5.24 (−7.92−-2.56) | <0.001 | −3.16 (−5.61—0.72) | 0.01 | |

| Insurance | 179 | REF | |||

| Uninsured | |||||

| Medicare/medicaid | −11.63 (−20.94−-2.32) | 0.02 | −10.47 (−18.16—2.78) | 0.008 | |

| Private | −15.88 (−25.03−-6.72) | 0.001 | −13.42 (−20.98—5.85) | 0.001 | |

| Both | −15.28 (−24.94−-5.61) | 0.002 | −15.59 (−23.69—7.49) | <0.001 | |

| Work | 180 | REF | |||

| Looking for work | |||||

| Full Time | 2.20 (−5.43-9.82) | NS | |||

| Part time | 4.92 (−3.26-13.11) | NS | |||

| Disabled/sick leave | 9.46 (1.48-17.44) | 0.02 | |||

| Student | 6.03 (−3.17-15.22) | NS | |||

| Homemaker | 2.38 (−5.88-10.56) | NS | |||

| Retired | 4.08 (−3.86-12.03) | NS | |||

| Income | 169 | REF | |||

| <$30k | |||||

| $30k-60k | −3.19 (−6.42-0.03) | 0.05 | |||

| $60k-$100k | −5.99 (−9.21—2.77) | <0.001 | |||

| $100k-$250k | −5.13 (−8.37—1.89) | 0.002 | |||

| >$250k | −10.54 (−14.81−-6.26) | <0.001 | |||

| PsA duration (years) | 292 | −0.04 (−0.11-0.03) | NS | ||

| PsO duration (years) | 288 | −0.02 (−0.07-0.03) | NS | ||

| ASAS classification | 149 | 0.68 (−2.05-3.41) | NS | ||

| Inflammatory Back Pain | 180 | −0.04 (−2.49-2.41) | NS | ||

| Osteoarthritis | 209 | 0.65 (−1.32-2.62) | NS | ||

| Fibromyalgia | 209 | 6.10 (2.611-9.56) | 0.001 | 4.51 (1.13-7.88) | 0.009 |

| History of Diabetes | 345 | 0.37 (−1.85-2.60) | NS | ||

| History of Cardiovascular disease | 344 | 2.12 (0.31-3.93) | 0.02 | ||

| Depression | 298 | 4.15 (2.42-5.89) | <0.001 | ||

| Total swollen joint count | 230 | 0.67 (0.44-0.90) | <0.001 | ||

| Total tender joints | 230 | 0.38 (0.26-0.50) | <0.001 | 0.25 (0.14-0.36) | <0.001 |

| Enthesitis Count | 178 | 2.13 (1.09-3.17) | <0.001 | 1.20 (0.30-2.01) | 0.009 |

| Dactylitis Count | 181 | 1.13 (−0.30-2.5) | 0.12 | ||

| Nail dystrophy | 143 | −1.06 (−3.53-1.41) | NS | ||

The β-coefficients can be interpreted as the difference in the mean PRO score between the two groups. The 95% confidence intervals do not include 0 (no difference). CIs that do not cross 0 indicate statistical difference. Every increase in year of age results in an inverse relationships with the RAPID3 score.

Left sex in – biologically relevant.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, we demonstrated the construct validity of RAPID3 and PSAID12 in PsA; they are strongly associated with each other and correlate well with measures of similar constructs, replicating a priori hypotheses. To our knowledge, this is the first study to directly compare RAPID3 and PSAID and we found that despite containing different items on the questionnaire, they are highly correlated and measure the same construct, disease impact. Both RAPID3 and PSAID differentiated well between high and low disease states as demonstrated by swollen and tender joint counts and differed in subsets of patients. The presence of enthesitis also seemed to be captured by the RAPID3 as patients with enthesitis had a higher score than patients without enthesitis and it remained in the multivariable model after adjustment for other factors.

RAPID3 is a “multidimensional” instrument which involves questions not only about functional ability but also pain and includes a “global” assessment which captures the patient’s overall status.(33) Previous studies in RA have shown that RAPID3 correlates well with the DAS28 (a measure of peripheral arthritis disease activity), the patient pain assessment, and inflammatory biomarkers (i.e., ESR or CRP) and thus has construct validity in RA.(42) However, unlike in RA, in our study the RAPID3 was only mildly correlated with disease activity (i.e., swollen and tender joint counts). Our results better support RAPID3 as a disease impact rather than disease activity measure in PsA. In comparison to RA, PsA is a more heterogeneous disease with additional features such as psoriasis, enthesitis, dactylitis, and spondylitis, that may influence the RAPID3 scores beyond peripheral arthritis alone and the degree to which these contributed to the scores was previously unknown.(43) The strong associations of RAPID3 with other PROs in PsA patients suggest that these additional features were adequately captured with RAPID3.(44) The weighting of the global and pain scores may account for the strong association observed with overall disease impact.

Our findings are complementary to earlier work conducted on the RAPID3. Coates et al demonstrated good responsiveness and discrimination in a clinical trial (Tight Control of Psoriatic Arthritis (TICOPA)) and an observational cohort (Long-Term Outcome in Psoriatic Arthritis Study (LOPAS II)) and demonstrated that RAPID3 differentiated between patients in minimal disease activity vs. patients with active disease. RAPID3 also correlated with levels of disease activity, as measured by two validated composite measure of PsA activity, PASDAS and DAPSA.(7, 45) Conversely, our findings differed from the study conducted by Vakil-Gilani et al. in a clinical care population (patients with psoriasis and PsA). Although the patients had similar RAPID3 scores to those in our study, the authors found a non-linear relationship between RAPID3 and Psoriasis Quality of Life 12 item questionnaire (PQoL12). Based on the weak correlation between these instruments, and the inability to transform the scores, the authors concluded that RAPID3 “fails to capture mental and psychological health information.”(46) Our findings, however, suggest RAPID3 was at least moderately correlated with HRQoL instruments (though PQoL12 was not measured) and was strongly correlated with PSAID.

While RAPID3 is widely used and can be used in multiple diseases, PSAID also has advantages over RAPID3: it was developed among patients with PsA for measurement of PsA and been validated in more than one cohort; it includes an item addressing the skin, which RAPID3 does not directly address; and cut-offs for thresholds of meaning (i.e., patient acceptable symptom state and minimal clinically important differences) have been established. Additionally, PSAID12 was recently provisionally endorsed by OMERACT for the measurement of disease-specific HRQoL in clinical trials.(14)(43) Given these advantages, in particular the content validity, it is that much more interesting that the two measures are so strongly correlated.

Examination of contextual factors relevant for RAPID3 and PSAID in PsA is a strength of this study. Contextual factors are the other factors aside from the patient’s disease that may inform the way a patient responds to a questionnaire.(26) This is important as these factors can be confounders that lead to differential study effects and bias.(47) Therefore, we assessed contextual factors to identify items that should be collected in studies to fully understand these scores. Education, insurance type, enthesitis, and total tender joint count were independently associated with RAPID3 scores. These same factors plus the swollen joint count and depression were independently associated with PSAID scores. Although there may be a bidirectional relationship (e.g., reduced physical function leads to more tender joint counts and vice versa), overall these data suggest that at a minimum these factors should be captured in observational studies using the RAPID3 or PSAID as a primary outcome. Of note, insurance type may be a marker of socioeconomic status and our findings may be related to potential undertreatment in the uninsured or underinsured PsO and PsA populations in the US.(48) Longitudinal analyses are needed to better understand the relationship between contextual factors and outcomes and whether these relationships portend poorer response.

Generalizability is a strength of this study as it is multi-center observational cohort study representing four different geographic areas in the US three regions within the US in four cities with varied patient populations and a wide range of disease activity and disease features allowing for analyses in subsets of patients. We have demonstrated that using pooled data from multiple centers is possible when data collection is standardized with this PARC cohort and longitudinal studies in future are planned within this cohort.

This is a cross-sectional, complete case-analysis and therefore has limitations. First, the study was performed in academic medical centers so selection bias may affect the generalizability of the results. On the contrary, the minimal exclusion criteria should limit the impact of selection bias. We did not evaluate the instruments’ reliability. Reliability has been addressed in other studies.(12, 33) While our findings support previous validation studies of RAPID3 and PSAID, longitudinal data on discrimination, responsiveness, and construct validity of these PROs in PsA is still needed. Furthermore, we used a conversion method to transform the scores of HAQDI to MDHAQ from one center that did not collect RAPID3 but instead collected HAQDI, patient global and patient pain assessment. This conversion method has previously been validated in rheumatoid arthritis (not in a PsA population) and therefore could affect the validity of our results. Excluding this center from the analysis did not affect the results. Additionally, studies to determine whether these scores can be transformed from one to another would be helpful.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate that RAPID3 and PSAID12 are strongly correlated and appear to measure similar constructs, broadly assessing the impact of psoriatic arthritis on function and wellness. The main advantages include that RAPID3 and PSAID12 are easy to complete and score and exist in both paper and mobile applications. Moreover, they are non-proprietary for clinical use. Additionally, the RAPID3 is the most commonly used PRO in clinical practice in the United States.(42) RAPID3 and PSAID scores are influenced by enthesitis, joint counts, insurance type and depression, and these contextual factors and active disease domains should be considered when interpreting the scores. Additional longitudinal studies are needed to determine which is most optimal for monitoring long-term outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement:

We would like to thank Kathleen Bush, Christina Burgese, Samantha Jackson, and Brenda Northop for their administrative support. Additionally, we would like to thank the patients who spent time completing these assessments.

Funding:

This work was supported by NIH/NIAMS R01 AR072363.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

Dr. Walsh has received consulting fees or research grants from Novartis, AbbVie, Amgen, Lilly, and Pfizer

Dr. Husni has received consulting fees, speaking fees, and/or honoraria from AbbVie, Janssen, Sanofi Genzyme/Regeneron, UCB, Novartis, and Lilly (less than $10,000 each) and is a coinventor on a patent for a psoriatic arthritis questionnaire (Psoriatic Arthritis Screening Evaluation), for which she receives royalties.

Dr. Reddy has received consulting fees, speaking fees, and/or honoraria from Novartis, AbbVie, Amgen, UCB, and Pfizer (less than $10,000 each).

Dr. Scher has received consulting fees from Janssen, UCB, BMS (less than $10,000 each), consulting fees from Novartis (more than $10,000) and consulting fees or research grants from Novartis to NYU Langone Health.

Dr. Ogdie has received consulting fees, speaking fees, and/or honoraria from AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Corrona, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and Takeda (less than $10,000 each). Grants from Novarits and Pfizer to the trustees of University of Pennsylvania. Royalties to husband from Novartis (greater than $10,000).

Dr. Wan and Ms. Willinger have no relevant financial disclosures with respect to the work presented.

References

- 1.Ader D. Introduction: Developing the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (promis). Medical Care 2007;45:S1–S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deshpande PR, Rajan S, Sudeepthi BL, Abdul Nazir CP. Patient-reported outcomes: A new era in clinical research. Perspect Clin Res 2011;2:137–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Egleston BL, Miller SM, Meropol NJ. The impact of misclassification due to survey response fatigue on estimation and identifiability of treatment effects. Stat Med 2011;30:3560–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orbai AM, Ogdie A. Patient-reported outcomes in psoriatic arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2016;42:265–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pincus T, Yazici Y, Castrejon I. Pragmatic and scientific advantages of mdhaq/ rapid3 completion by all patients at all visits in routine clinical care. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis 2012;70 Suppl 1:30–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pincus T, Swearingen C, Wolfe F. Toward a multidimensional health assessment questionnaire (mdhaq): Assessment of advanced activities of daily living and psychological status in the patient-friendly health assessment questionnaire format. Arthritis Rheum 1999;42:2220–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coates LC, Tillett W, Shaddick G, Pincus T, Kavanaugh A, Helliwell PS. Value of the routine assessment of patient index data 3 in patients with psoriatic arthritis: Results from a tight-control clinical trial and an observational cohort. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2018;70:1198–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park SH, Choe JY, Kim SK, Lee H, Castrejon I, Pincus T. Routine assessment of patient index data (rapid3) and bath ankylosing spondylitis disease activity index (basdai) scores yield similar information in 85 korean patients with ankylosing spondylitis seen in usual clinical care. J Clin Rheumatol 2015;21:300–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Danve A, Reddy A, Vakil-Gilani K, Garg N, Dinno A, Deodhar A. Routine assessment of patient index data 3 score (rapid3) correlates well with bath ankylosing spondylitis disease activity index (basdai) in the assessment of disease activity and monitoring progression of axial spondyloarthritis. Clin Rheumatol 2015;34:117–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castrejon I, Pincus T, Wendling D, Dougados M. Responsiveness of a simple rapid-3-like index compared to disease-specific basdai and asdas indices in patients with axial spondyloarthritis. RMD Open 2016;2:e000235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castrejon I, Bergman MJ, Pincus T. Mdhaq/rapid3 to recognize improvement over 2 months in usual care of patients with osteoarthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, spondyloarthropathy, and gout, as well as rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Rheumatol 2013;19:169–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gossec L, de Wit M, Kiltz U, Braun J, Kalyoncu U, Scrivo R, et al. A patient-derived and patient-reported outcome measure for assessing psoriatic arthritis: Elaboration and preliminary validation of the psoriatic arthritis impact of disease (psaid) questionnaire, a 13-country eular initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1012–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orbai AM, de Wit M, Mease P, Shea JA, Gossec L, Leung YY, et al. International patient and physician consensus on a psoriatic arthritis core outcome set for clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:673–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orbai AM, Holland R, Leung YY, Tillett W, Goel N, Christensen R, et al. Psaid12 provisionally endorsed at omeract 2018 as core outcome measure to assess psoriatic arthritis-specific health-related quality of life in clinical trials. J Rheumatol 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Carlo M, Becciolini A, Lato V, Crotti C, Favalli EG, Salaffi F. The 12-item psoriatic arthritis impact of disease questionnaire: Construct validity, reliability, and interpretability in a clinical setting. J Rheumatol 2017;44:279–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Talli S, Etcheto A, Fautrel B, Balanescu A, Braun J, Canete JD, et al. Patient global assessment in psoriatic arthritis - what does it mean? An analysis of 223 patients from the psoriatic arthritis impact of disease (psaid) study. Joint Bone Spine 2016;83:335–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cauli A, Gladman DD, Mathieu A, Olivieri I, Porru G, Tak PP, et al. Patient global assessment in psoriatic arthritis: A multicenter grappa and omeract study. J Rheumatol 2011;38:898–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Generali E, Scire CA, Cantarini L, Selmi C. Sex differences in the treatment of psoriatic arthritis: A systematic literature review. Isr Med Assoc J 2016;18:203–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nas K, Capkin E, Dagli AZ, Cevik R, Kilic E, Kilic G, et al. Gender specific differences in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Mod Rheumatol 2017;27:345–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lubrano E, Perrotta FM, Manara M, D'Angelo S, Addimanda O, Ramonda R, et al. The sex influence on response to tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors and remission in axial spondyloarthritis. J Rheumatol 2018;45:195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gudu T, Etcheto A, de Wit M, Heiberg T, Maccarone M, Balanescu A, et al. Fatigue in psoriatic arthritis - a cross-sectional study of 246 patients from 13 countries. Joint Bone Spine 2016;83:439–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braaten T, Breviu B, Walsh JA, Presson A, Zhang C, Clegg DO. Gender differences in patient reported outcomes (pros) in psoriatic arthritis [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toy S, Ozbag D, Altay Z. The effects of pre-obesity on quality of life, disease activity, and functional status in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. North Clin Istanb 2017;4:52–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosas J, Llinares-Tello F, Senabre-Gallego JM, Barber-Valles X, Santos-Soler G, Salas-Heredia E, et al. Obesity decreases clinical efficacy and levels of adalimumab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2017;35:145–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Micheroli R, Hebeisen M, Wildi LM, Exer P, Tamborrini G, Bernhard J, et al. Impact of obesity on the response to tumor necrosis factor inhibitors in axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2017;19:164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee YX, Kwan YH, Png WY, Lim KK, Tan CS, Lui NL, et al. Association of obesity with patient-reported outcomes in patients with axial spondyloarthritis: A cross-sectional study in an urban asian population. Clin Rheumatol 2017;36:2365–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gunter T, Walsh JA. Comparison of patient and provider assesssments of response to therapy for psoriatic arthritis [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sethi M, Ren-Fielding C, Caminar AC, Scher JU, Reddy SM. Clinical improvements in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis with surgical weight loss [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reddy SM, Scher JU, Swearingen CJ, Yazici Y. Gender differences in disease activity accounting for inflammatory biomarkers in psoriatic arthritis routine care cohort [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor W, Gladman D, Helliwell P, Marchesoni A, Mease P, Mielants H, et al. Classification criteria for psoriatic arthritis: Development of new criteria from a large international study. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:2665–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sieper J, van der Heijde D, Landewe R, Brandt J, Burgos-Vagas R, Collantes-Estevez E, et al. New criteria for inflammatory back pain in patients with chronic back pain: A real patient exercise by experts from the assessment of spondyloarthritis international society (asas). Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:784–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Healy PJ, Helliwell PS. Measuring clinical enthesitis in psoriatic arthritis: Assessment of existing measures and development of an instrument specific to psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2008;59:686–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pincus T, Swearingen CJ, Bergman M, Yazici Y. Rapid3 (routine assessment of patient index data 3), a rheumatoid arthritis index without formal joint counts for routine care: Proposed severity categories compared to disease activity score and clinical disease activity index categories. J Rheumatol 2008;35:2136–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anderson J, Sayles H, Curtis JR, Wolfe F, Michaud K. Converting modified health assessment questionnaire (haq), multidimensional haq, and haqii scores into original haq scores using models developed with a large cohort of rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62:1481–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Helliwell PS, Waxman R. Modification of the psoriatic arthritis disease activity score (pasdas). Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:467–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Streiner D, Norman G. Validity. Health measurement scales: A practical guide to their development and use. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2008. p. 247–76. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Journal TBM. Correlation and regression. 2019. [updated 2019; cited June 1, 2019]; Available from: https://www.bmj.com/about-bmj/resources-readers/publications/statistics-square-one/11-correlation-and-regression.

- 38.Walsh JA, Willinger C, Husni ME, Reddy SM, Scher JU, Ogdie A. Construct validity of rapid3 for measurement of disease activity in psoriatic arthritis [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mokkink LB, Prinsen CA, Bouter LM, Vet HC, Terwee CB. The consensus-based standards for the selection of health measurement instruments (cosmin) and how to select an outcome measurement instrument. Braz J Phys Ther 2016;20:105–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Knol DL, Stratford PW, Alonso J, Patrick DL, et al. The cosmin checklist for evaluating the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties: A clarification of its content. BMC Med Res Methodol 2010;10:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.The outcome measures in rheumatology (omeract) handbook. 2019. [updated 2019; cited June 1, 2019]; Available from: https://omeracthandbook.org/.

- 42.Pincus T, Furer V, Keystone E, Yazici Y, Bergman MJ, Luijtens K. Rapid3 (routine assessment of patient index data 3) severity categories and response criteria: Similar results to das28 (disease activity score) and cdai (clinical disease activity index) in the rapid 1 (rheumatoid arthritis prevention of structural damage) clinical trial of certolizumab pegol. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63:1142–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Michelsen B, Fiane R, Diamantopoulos AP, Soldal DM, Hansen IJ, Sokka T, et al. A comparison of disease burden in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis and axial spondyloarthritis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0123582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Husted JA, Tom BD, Schentag CT, Farewell VT, Gladman DD. Occurrence and correlates of fatigue in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:1553–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coates LC, Moverley AR, McParland L, Brown S, Navarro-Coy N, O'Dwyer JL, et al. Effect of tight control of inflammation in early psoriatic arthritis (ticopa): A uk multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015;386:2489–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vakil-Gilani KM, Dinno A, Rich-Garg N, Deodhar A. Routine assessment of patient index data 3 score and psoriasis quality of life assess complementary yet different aspects of patient-reported outcomes in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. J Clin Rheumatol 2018;24:319–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sterne JA, Hernan MA, Reeves BC, Savovic J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. Robins-i: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016;355:i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Armstrong AW, Robertson AD, Wu J, Schupp C, Lebwohl MG. Undertreatment, treatment trends, and treatment dissatisfaction among patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in the united states: Findings from the national psoriasis foundation surveys, 2003-2011. JAMA Dermatol 2013;149:1180–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.