Abstract

Background

Tubulointerstitial fibrosis (TIF) is a critical pathological feature of chronic renal failure (CRF), with oxidative stress (OS) and hypoxic responses in renal proximal tubular epithelial cells playing pivotal roles in disease progression. This study explores the effects of Modified Zhenwu Tang (MZWT) on these processes, aiming to uncover its potential mechanisms in slowing CRF progression.

Methods

We used adenine (Ade) to induce CRF in rats, which were then treated with benazepril hydrochloride (Lotensin) and MZWT for 8 weeks. Assessments included liver and renal function, electrolytes, blood lipids, renal tissue pathology, OS levels, the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) pathway, inflammatory markers, and other relevant indicators. In vitro, human renal cortical proximal tubular epithelial cells were subjected to hypoxia and lipopolysaccharide for 72 h, with concurrent treatment using MZWT, FM19G11, and N-acetyl-l-cysteine. Measurements taken included reactive oxygen species (ROS), HIF pathway activity, inflammatory markers, and other relevant indicators.

Results

Ade treatment induced significant disruptions in renal function, blood lipids, electrolytes, and tubulointerstitial architecture, alongside heightened OS, HIF pathway activation, and inflammatory responses in rats. In vivo, MZWT effectively ameliorated proteinuria, renal dysfunction, lipid and electrolyte imbalances, and renal tissue damage; it also suppressed OS, HIF pathway activation, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in proximal tubular epithelial cells, and reduced the production of inflammatory cytokines and collagen fibers. In vitro findings demonstrated that MZWT decreased apoptosis, reduced ROS production, curbed OS, HIF pathway activation, and EMT in proximal tubular epithelial cells, and diminished the output of inflammatory cytokines and collagen.

Conclusion

OS and hypoxic responses significantly contribute to TIF development. MZWT mitigates these responses in renal proximal tubular epithelial cells, thereby delaying the progression of CRF.

Keywords: Chronic renal failure, Renal proximal tubular epithelial cells, Oxidative stress, Hypoxic response, Traditional Chinese medicine

1. Introduction

Chronic renal failure (CRF) is a clinical syndrome characterized by various clinical symptoms and metabolic disturbances due to the slow progressive dysfunction of the kidneys caused by various diseases, eventually leading to uremia and complete renal failure [1]. This condition is associated with numerous complications, a poor prognosis, high medical costs, and severely impacts patients' quality of life. Therefore, delaying the progression of CRF and improving patients' quality of life holds significant academic and social value. Increasing evidence suggests that the correlation between renal dysfunction and the extent of tubulointerstitial damage is stronger than that with glomerular damage. The severity of tubulointerstitial fibrosis (TIF) is directly related to the decline in renal function and correlates with long-term prognosis [[2], [3], [4]], highlighting the critical role of TIF in the progression of CRF [[5], [6], [7]].

Oxidative stress (OS) is defined as an imbalance between oxidation and antioxidation [8], with reactive oxygen species (ROS) as the primary participants. While ROS generation is a physiological process essential for many cellular signaling pathways and immune defenses, excessive ROS production can cause severe oxidative damage to biomolecules like lipids, proteins, and DNA. OS is present in the early stages of chronic kidney disease (CKD), contributing to disease progression as it worsens [[9], [10], [11]]. The damage might stem from OS products that promote renal ischemia by stimulating glomerular injury, cell death, and apoptosis, eventually triggering severe inflammatory processes and leading to progressive renal damage [12,13].

During the progression of CKD, activation of the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System leads to tubular atrophy, alterations in tubular sodium ion concentration, and changes in filtrate flow rate. Angiotensin II (Ang II) induces afferent arteriolar contractions, reducing peritubular capillary perfusion and causing tubulointerstitial hypoxia [14]. Additionally, Ang II directly harms endothelial cells by inducing OS through NADPH oxidase activation, leading to peritubular capillary loss and subsequent cellular hypoxia due to inefficient respiration in tubular epithelial cells. Therefore, Ang II can induce renal hypoxia via both hemodynamic and non-hemodynamic mechanisms. As TIF progresses, the distance between peritubular capillaries and renal tubules increases, extending the oxygen diffusion distance and exacerbating hypoxia in tubular epithelial cells. This hypoxia activates the HIF-1 pathway, leading to phenotypic transformation and the release of inflammatory mediators such as interleukin (IL) 1β and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α [[15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24]], which further exacerbate TIF. This creates a vicious cycle of chronic hypoxia, continuous disease progression, and loss of peritubular capillaries.

Currently, there is a lack of ideal drugs in clinical practice that can simultaneously address OS and hypoxic responses while alleviating TIF. This study aimed to determine whether OS and hypoxic responses in renal proximal tubular epithelial cells are involved in TIF, and to investigate if Modified Zhenwu Tang (MZWT) can delay the progression of CRF by alleviating these conditions in renal proximal tubular epithelial cells.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

Animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Ethics Committee of Hebei Yiling Pharmaceutical Research Institute (Approval No. N2022070). Specific pathogen-free male SD rats (260 ± 20 g, 8 weeks old) were procured from Beijing Weitong Lihua Experimental Animal Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). The animals were housed under standardized conditions at the Hebei Yiling Medical Research Institute Co., Ltd. Feeding conditions included relative humidity of 50–70 %, temperature of 23–25 °C, a 12 h light/dark cycle, animal drinking water, and mouse maintenance feed (Beijing Huafukang Biotechnology Co., Ltd., License No. Beijing Feed Certificate (2019–06076)), with corncob bedding (Beijing Keao Xieli Feed Co., Ltd., Batch No.: 22049811).

2.2. Experimental design

A total of 42 male SD rats were randomly assigned to a normal group (n = 12) and a model group (n = 30). Adenine (Ade) was dissolved in 0.5 % sodium carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC-Na) to prepare a suspension. The model group rats received Ade at 150 mg/(kg·d) via oral gavage, while the normal group received an equivalent volume of CMC-Na. After 4 weeks of gavage, 24 h urine samples were collected from both groups. Three rats from each group were randomly selected for histological examinations using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Masson's trichrome, and biochemical staining, revealing renal function abnormalities, renal tubule dilation, and increased collagen fibers in the glomerular and renal tubule basement membranes in the model group. The remaining model group rats were divided into three groups: a model group (M), a MZWT group (MZWT), and a benazepril hydrochloride group (Lotensin), with nine rats each. The model group continued to receive Ade at 150 mg/(kg·d); the MZWT group was administered 150 mg/(kg·d) Ade alongside MZWT at 7.2 g/(kg·d); the Lotensin group was given 150 mg/(kg·d) Ade and benazepril hydrochloride at 10 mg/(kg·d); the normal group received an equivalent volume of CMC-Na, with all treatments lasting for an additional 8 weeks. Besides collecting essential data through pathological autopsy, animals that required euthanasia were humanely euthanized under deep anesthesia (intraperitoneal injection of 2 % pentobarbital sodium, 100–200 mg/kg).

2.3. Drug preparation

MZWT free decoction granules consisted of the following components: Astragalus 15 g, Salvia miltiorrhiza 15 g, raw rhubarb 6 g, Poria 9 g, white peony 9 g, ginger 9 g, processed Radix Aconiti 9 g, and Atractylodes 6 g (supplied by Sichuan Neo-Green Pharmaceutical Technology Development Co., Ltd., batch numbers: 20080124, 21080024, 20120030, 21100051, 20070087, 21040160, 21040091, and 21090123, respectively). The granules were dissolved in 0.5 % CMC-Na solution for gavage administration. Additionally, male SD rats were administered MZWT at 14.4 g/kg twice daily for 7 consecutive days to prepare drug-containing serum. Appropriate intervention concentrations of drug-containing serum for in vitro experiments were determined using the CCK8 method. Benazepril hydrochloride (Shanghai Xinya Pharmaceutical Minhang Co., Ltd., approval number: H20044840, 10 mg/tablet), FM19G11 (Glpbio, GC50537), N-acetyl-l-cysteine (NAC) (Sigma, C8460), and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Sigma, L8880) were also used.

2.4. Twenty-four-hour UTP and urinary creatinine level detection

On the 13th weekend, experimental rats fasted but had access to water, and 24 h urine samples were collected using metabolic cages. Urinary total protein (TP) (24 h-UTP) and creatinine (Cr) levels were quantified using a urine TP reagent (Shijiazhuang Changjiang Bio-Experimental Technology Development Co., Ltd., 220526) and a Cr reagent kit (Beckman Coulter Experimental Systems Co., Ltd., AUZ3562) with a urine analyzer (CLINITEK50, USA).

2.5. Renal function, blood lipids, and electrolyte level analyses

Levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), Cr, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), serum total triglyceride (TG), and total cholesterol (TC) were assessed using commercial kits (Beckman Coulter Experimental Systems Co., Ltd., AUZ3689, AUZ3645, AUZ3562, AUZ3611, AUZ3592, and AUZ3625). Serum TP and albumin (Alb) levels were measured using kits from Zhongsheng Beikong Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (200941, 200923), and blood P, K, and Ca levels were determined using kits from Changchun Huili Biotech Co., Ltd. (B008, K060, K063). These analyses were performed using an automatic biochemical analyzer (Sysmex HEMIX-180, Japan).

2.6. HE and Masson staining

Renal tissues were fixed in 4 % polyformaldehyde for 48 h, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned (4 μm thick). Paraffin sections were de-waxed to water, stained with H&E (Servicebio, G1003) and Masson's trichrome (Servicebio, G1006), then dehydrated, cleared, and mounted. Pathological changes in renal tissues were examined under a microscope. Following Masson staining, images from three different fields of view were captured and analyzed using ImageJ software.

2.7. Immunohistochemistry detection of superoxide dismutase 1, malondialdehyde, HIF-1α, prolyl hydroxylase domain 2, IL-1β, TNF-α, α-smooth muscle actin, and COL1A1 expression levels in rat renal tissue

Renal tissue paraffin sections underwent de-waxing to water, antigen retrieval, blocking of endogenous peroxidase activity, and sealing with serum. The sections were then incubated with primary antibodies against superoxide dismutase (SOD) 1, malondialdehyde (MDA), IL-1β, TNF-α, prolyl hydroxylase domain (PHD) 2, HIF-1α, α-smooth muscle actin (SMA), and COL1A1, all diluted in PBS. This was followed by application of biotin-labeled secondary antibodies and incubation at room temperature. The sections were then rinsed with tap water, counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and sealed. Images were captured under a bright-field microscope. Three non-overlapping fields were analyzed for each section using ImageJ software. Details of the reagents used are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Antibody information.

| Antibody name | Production company | Batch number | Dilution rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| SOD1 | Proteintech | 10269-1-AP | 1∶500 |

| MDA | Beijing Biosynthesis Biotechnology Co., Ltd | bs-23343R | 1∶500 |

| IL-1β | Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd | PB0981 | 1∶500 |

| TNF-α | Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd | GB11188 | 1∶500 |

| PHD2 | Proteintech Group, Inc | 19886-1-AP | 1∶200 |

| HIF-1α | Beijing Biosynthesis Biotechnology Co., Ltd | bs-20399R | 1∶200 |

| α-SMA | Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd | GB11347 | 1∶2000 |

| COL1A1 | Wuhan Boster Biological Technology., Ltd | PB0981 | 1∶200 |

2.8. Real-time polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was extracted from kidney tissue using trichloromethane (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., 10006818) and reverse transcribed using the Servicebio® RT First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Servicebio, G3330). Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed in triplicate using a fluorescence quantitative PCR machine (Bio-Rad, CFX). All primers were synthesized by ServiceBio Biotechnology Co., Ltd. GAPDH was used as an internal control, and the primer sequences are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Primer sequences.

| Primer name | Primer sequence (5′-3′) | Fragment length (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| R-GAPDH-S | CTGGAGAAACCTGCCAAGTATG | 138 |

| R-GAPDH-A | GGTGGAAGAATGGGAGTTGCT | |

| R-IL1b(5)-S | TGACCTGTTCTTTGAGGCTGAC | 272 |

| R-IL1b(5)-A | CATCATCCCACGAGTCACAGAG | |

| R-TNF-α-S | AGAACTCCAGGCGGTGTCTGT | 123 |

| R-TNF-α-A | TTGGGAACTTCTCCTCCTTGTT |

2.9. Cell culture

Human renal cortical proximal tubular epithelial cells (HK-2 cells) were obtained from Wuhan Procell Life Science and Technology Co., Ltd. (CL-0109). The HK-2 cell culture medium consisted of MEM supplemented with 10 % FBS and 1 % penicillin-streptomycin solution. The cells were cultured under conditions of 37 °C and 5 % CO2 at saturated humidity.

2.10. Cell treatment

HK-2 cells were divided into six groups: Normal group (A): HK-2 cells cultured under standard conditions; Model group (B): Treated with 1 % O2 and 2 μg/mL LPS (Sigma, L8880); Blank serum group (C): Treated with 15 % blank serum in addition to the model group conditions; Drug serum group (D): Treated with 15 % MZWT drug serum in addition to the model group conditions; FM19G11 group (E): Treated with 300 nM FM19G11 in addition to the model group conditions (FM19G11 is a hypoxia-inducible factor-1-alpha (HIF-1α) inhibitor used to inhibit the activation of the HIF pathway and reduce the hypoxia response); NAC group (F) Treated with 100 μM NAC in addition to the model group conditions (NAC is a thiol-containing antioxidant and a precursor of glutathione (GSH). It is used to scavenge oxygen ions and free radicals, reducing OS). All groups were cultured at 37 °C and 5 % CO2 for 72 h.

2.11. TUNEL method for detecting cell apoptosis

Cells adhered to the slides were fixed at room temperature, washed with PBS, and processed according to the cell apoptosis detection kit instructions (Vazyme, 037E2251HA). Nuclei were counterstained and sealed with a mounting medium containing an anti-fluorescence quencher. Images were captured under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, BX53). Three non-overlapping fields were randomly selected, apoptotic cells were counted, and the results were analyzed.

2.12. Flow cytometry detection of intracellular ROS

Cells were detached using trypsin, suspended in PBS, and washed with PBS. They were then analyzed using a cell ROS detection kit and flow cytometry was performed (BECKMAN, CytoFLEX).

2.13. Biochemical method for detecting oxidative/antioxidant levels in cell supernatant

Cell supernatant was collected, and GSH, SOD, and MDA levels were measured using detection kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Biological Engineering Institute; A006-2-1, A001-3-1, and A003-1) to assess antioxidant capacity and lipid peroxidation.

2.14. IL-1β and TNF-α level analysis

Serum and cell supernatant were collected, and IL-1β and TNF-α expression levels were detected using ELISA kits; IL-1β ELISA kit (Lianke Biotech, EK301B-01; Wuhan Cloud-Clone Technology Co., Ltd., L221207981) and TNF-α ELISA kit (Thermo Fisher, 88–7340; Wuhan Cloud-Clone Technology Co., Ltd., L230131675).

2.15. Immunofluorescence analysis

Immunofluorescence was utilized to detect α-SMA expression in renal tissue and α-SMA and COL1A1 expression in HK-2 cells. Renal tissue sections (4 μm) were washed with PBS, incubated with FITC-labeled α-SMA antibody solution (1:200, Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd., GB11347), rinsed with PBS, and sealed with glycerin. Observation was conducted under a fluorescence microscope (NIKON, ECLIPSE C1) to assess the deposition location and intensity of α-SMA in each group. Images were captured and analyzed using ImageJ software, with positive results appearing bright red. Three different fields of view were selected for each group for analysis.

For adhered cells, following PBS rinse and paraformaldehyde fixation, cells were rinsed again with PBS, sealed at room temperature, and incubated with α-SMA and COL1A1 antibodies (1:100, boster, BM0002, bs-10423). After nuclear counterstaining, the slides were sealed with a sealant containing anti-fluorescence quencher, observed under a microscope (Olympus, BX53), and images were collected. For each group, three different fields of view were selected for analysis using ImageJ software.

2.16. Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was employed to measure the protein expression levels of SOD1, MDA, HIF-1α, PHD2, and α-SMA in renal tissue, as well as HIF-1α and PHD2 (CST, 36169, 4835) in cells of each experimental group. Proteins from rat renal tissue and monolayer adherent cells were extracted, and their concentrations were determined using the BCA method. The proteins were denatured by boiling in a water bath, separated by SDS-PAGE gel (GenScript Biotech Corporation, China), and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (optimized for 30 kDa–150 kDa proteins at 420 s/time 1.5 A). After adding room temperature sealant, membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with diluted primary antibodies: SOD1, MDA, PHD2 (all at 1:1000 dilution), HIF-1α (1:500, 1:1000), α-SMA (1:1000), beta-actin (1:2000), and GAPDH (1:2000, 1:1000) on a shaker. Following incubation, the membranes were washed with TBST and then incubated with secondary antibodies at a 1:5000 dilution at room temperature. After additional washes with TBST, color development and exposure were carried out, and data were analyzed using AIWBwellTM analysis software.

2.17. Statistical analysis

All results are expressed as the mean ± SD and analyzed using SPSS 21.0 software. Comparisons among multiple groups were performed using one-way analysis of variance. A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant, and a p-value <0.01 was considered highly statistically significant. All graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism software (version 8.0).

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Ade gavage and treatments on renal parameters

Ade gavage in SD rats induced abnormal 24 h-UTP, urinary Cr levels, renal function, blood lipids, and electrolytes, which were ameliorated by MZWT treatment. Compared with the N group, the M group exhibited significantly increased 24 h-UTP (P < 0.01) (Fig. 1a) and decreased urinary Cr (P < 0.01) (Fig. 1b). Serum levels of Scr, BUN, TG, TC, K, and P were also higher in the M group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1c, d, i, j, l, m). The MZWT and Lotensin groups showed improvements; urinary Cr levels were higher than in the M group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1b), with no apparent proteinuria (P < 0.01) (Fig. 1a). Serum levels of Scr, TG, K, and P in the MZWT group and Scr, K, and P in the Lotensin group were lower compared to the M group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1c, d, i, l, m).

Fig. 1.

Urine and blood test results of rats in each group: (a) 24 h-UTP, (b) urine Cr, (c) Scr, (d) BUN, (e) TP, (f) Alb, (g) ALT, (h) AST, (i) TG, (j) TC, (k) Ca, (l) K, and (m) P. Group designations: N: normal group, M: model group, MZWT: Modified Zhenwu Tang group, Lotensin: benazepril hydrochloride group. Statistical notations: ##P < 0.01, #P < 0.05 compared with the N group; **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 compared with the M group; NS indicates no statistical significance.

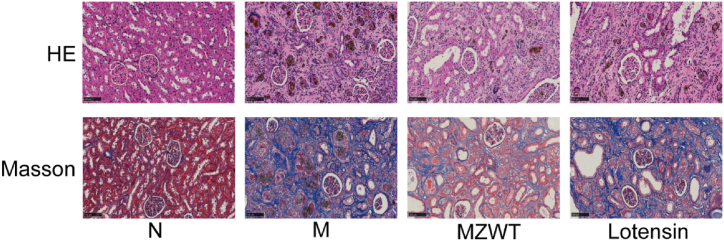

3.2. Ade gavage caused pathological damage to the kidneys of SD rats, which MZWT alleviated

HE staining results demonstrated that the N group had a clear renal cortex and medullary boundary, normal glomerular morphology, a regular arrangement of renal tubules, and no abnormal changes in the renal tubular interstitium. In contrast, M group exhibited significantly widened glomerular capsule spaces, inflammatory cell infiltration in the renal tubular interstitium, dilation of renal tubular lumens, brown crystal deposits, and renal tubular epithelial cell degeneration, necrosis, and focal atrophy. The pathological damage in the renal tissues of the MZWT and Lotensin groups was notably alleviated compared to the M group, with the MZWT group showing more significant improvement than the Lotensin group.

Masson staining results indicated that the N group maintained normal glomerular morphology and a regular arrangement of renal tubules, with no abnormal changes in the renal tubular interstitium and only a few collagen fibers around the renal capsule wall, glomerular basement membrane, and renal tubular basement membrane. The M group displayed a significant increase in the width of the renal tubular interstitium, abundant collagen fibers, and a substantial increase in collagen fibers around the renal capsule wall, glomerular basement membrane, and renal tubular basement membrane. Relative to the M group, the collagen fibers in the renal tubular interstitium, glomerular basement membrane, and renal tubular basement membrane were significantly reduced in both the MZWT and Lotensin groups, with the MZWT group showing superior performance. See Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Pathological changes in rat renal tissues (HE and Masson staining, magnification × 200). Group designations: N: normal group, M: model group, MZWT: Modified Zhenwu Tang group, Lotensin: benazepril hydrochloride group.

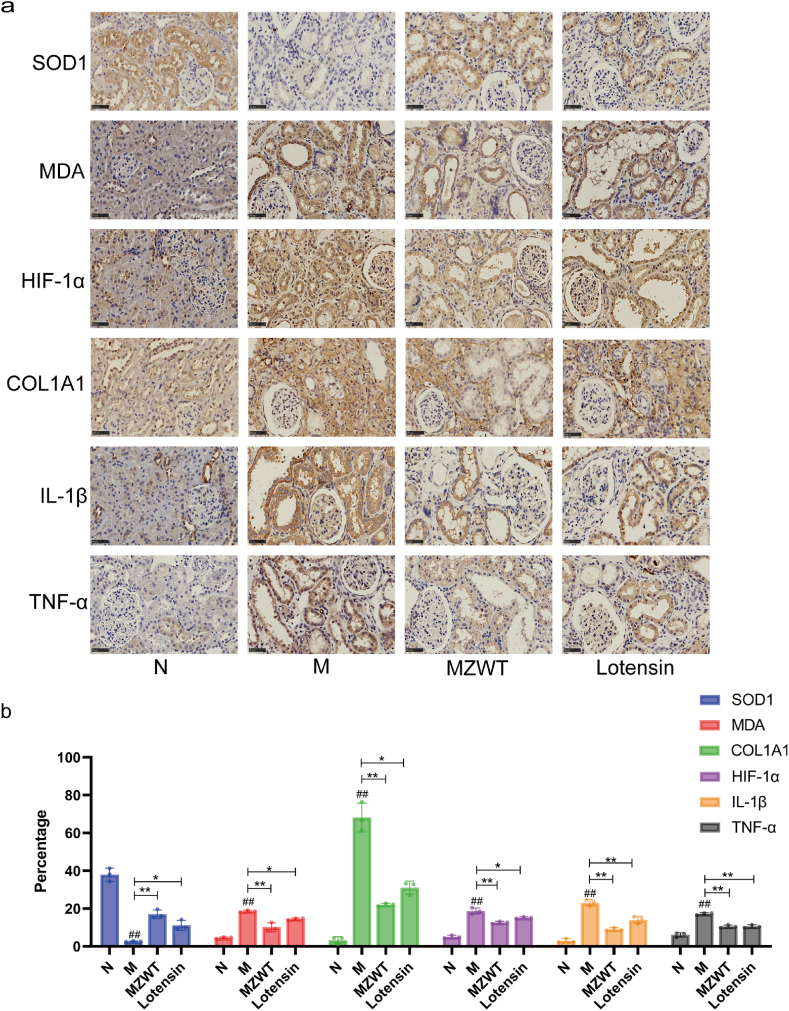

3.3. Ade gavage induced OS and a hypoxic response in rat proximal renal tubules, leading to collagen fiber and inflammatory factor production, while MZWT exhibited a protective effect

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) results revealed that, compared with the N group, the M group rats exhibited significantly increased expression of MDA, HIF-1α, COL1A1, IL-1β, and TNF-α in the proximal renal tubular epithelial cells and tubulointerstitial regions (Fig. 3a and b). Compared with the M group, the expression of these markers was reduced in the proximal renal tubular epithelial cells and tubulointerstitial regions in the MZWT and Lotensin groups. Additionally, SOD1 expression in the proximal renal tubular epithelial cells of the M group was significantly lower compared to the N group, while it was enhanced in the MZWT and Lotensin groups (Fig. 3a and b).

Fig. 3.

Adenine-induced oxidative stress, activation of the HIF pathway, and increased production of inflammatory factors and tubulointerstitial collagen fibers in rat proximal renal tubules, with MZWT mitigating these effects. (a) Immunohistochemical detection of SOD1, MDA, HIF-1α, COL1A1, IL-1β, TNF-α in rat renal tissues (IHC × 400). (b) Quantitative analysis of the positive expression areas for each marker. (N: normal group, M: model group, MZWT: Modified Zhenwu Tang group, Lotensin: benazepril hydrochloride group. ##P < 0.01, #P < 0.05 compared with the N group; **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 compared with the M group; NS indicates no statistical significance).

3.4. Ade gavage led to the production of pro-fibrotic and pro-inflammatory factors in rat kidneys, while MZWT and Lotensin reduced their production

RT-PCR results showed that, compared with the N group rats, the expression of IL-1β and TNF-α mRNA in the M group rats was enhanced (P < 0.01) (Fig. 4a and b). Compared with the M group, the expression of IL-1β and TNF-α mRNA in the rats of the MZWT and Lotensin groups was reduced (P < 0.01) (Fig. 4a and b).

Fig. 4.

RT-PCR analysis of IL-1β and TNF-α mRNA expression in renal tissues: (a) IL-1β, (b) TNF-α across different groups. Group designations: N: normal group, M: model group, MZWT: Modified Zhenwu Tang group, Lotensin: benazepril hydrochloride group. Statistical significance: ##P < 0.01, #P < 0.05 compared with the N group; **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 compared with the M group; NS indicates no statistical significance.

3.5. Hypoxia and LPS caused cell apoptosis in HK-2 cells, and MZWT reduced the number of apoptotic cells

Compared with group A, the number of apoptotic cells in group B was significantly increased, and the difference was statistically significant (P < 0.01) (Fig. 5a and b). Compared with group B, the number of apoptotic cells in groups D, E, and F was decreased (P < 0.01) (Fig. 5a and b), while the number of apoptotic cells in group C showed no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) (Fig. 5a and b).

Fig. 5.

Effects of hypoxia and LPS on apoptosis in HK-2 cells, and the modulating role of MZWT: (a) TUNEL assay detecting apoptosis in HK-2 cells (IF × 400), (b) Quantification of apoptotic cells across different treatment groups. Groups: A: Normal group, B: Model group, C: Blank serum group, D: Drug serum group, E: FM19G11 group, F: NAC group. Statistical significance: ##P < 0.01, #P < 0.05 compared with the A group; **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 compared with the B group; NS indicates no statistical significance.

3.6. Hypoxia and LPS led to a significant increase in ROS in HK-2 cells, and MZWT reduced ROS production

Compared with group A, the ROS content in group B was significantly increased, and the difference was statistically significant (P < 0.01) (Fig. 6, Fig. 7). Compared with group B, the ROS content in groups D, E, and F was decreased, and the difference was statistically significant (P < 0.01) (Fig. 6, Fig. 7). The difference in ROS content in group C compared with group B was not statistically significant (P > 0.05) (Fig. 6, Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

Measurement of ROS levels by flow cytometry across different treatment groups: (A) Normal group, (B) Model group, (C) Blank serum group, (D) Drug serum group, (E) FM19G11 group, (F) NAC group. Statistical significance is indicated as follows: compared with the A group, ##P < 0.01; #P < 0.05; compared with the B group, **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; NS denotes no statistical significance.

Fig. 7.

Response of HK-2 cells to hypoxia and LPS treatment, showing the modulation of ROS production by MZWT. (A: Normal group, B: Model group, C: Blank serum group, D: Drug serum group, E: FM19G11 group, F: NAC group).

3.7. Hypoxia and LPS led to oxidative/antioxidative imbalance in HK-2 cells, and MZWT alleviated the imbalance

The oxidative/antioxidative system was evaluated by measuring the activity of GSH, SOD, and MDA. Compared to group A, GSH and SOD activities in group B were significantly reduced (P < 0.01) (Fig. 8a and b), and MDA levels were significantly increased (P < 0.01) (Fig. 8c). Compared with group B, the SOD and GSH contents in the cell supernatants of groups D, E, and F were increased (P < 0.01) (Fig. 8a and b), and the MDA contents were decreased (P < 0.01) (Fig. 8c). The contents of SOD, MDA, and GSH in group C were not significantly different from those in group B (P > 0.05)(Fig. 8a, b, c).

Fig. 8.

Effects of hypoxia and LPS on oxidative and antioxidative balance in HK-2 cells, and the mitigative action of MZWT. Details of the oxidative markers assessed: (a) GSH, (b) SOD, (c) MDA. Group designations are as follows: (A: Normal group, B: Model group, C: Blank serum group, D: Drug serum group, E: FM19G11 group, F: NAC group). Statistical significance is noted as follows: ##P < 0.01, #P < 0.05 compared with the A group; **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 compared with the B group; NS indicates no statistical significance.

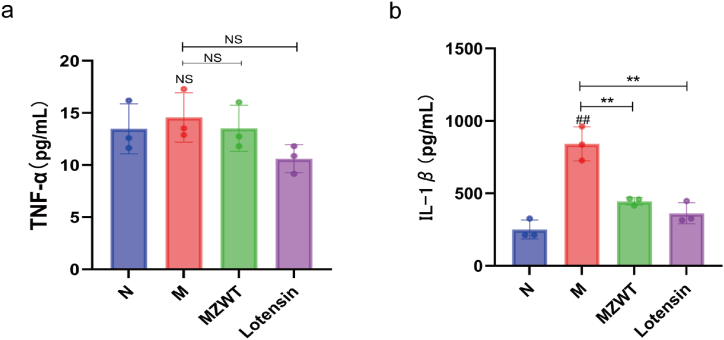

3.8 Ade gavage led to an increase in the expression level of pro-inflammatory factors in rat serum, while MZWT reduced their expression. Hypoxia and LPS increased the release of pro-inflammatory factors in HK-2 cells, and MZWT reduced their production.

Compared with the N group, the content of IL-1β in rat serum of the M group was significantly increased (P < 0.01)(Fig. 9b); compared with the M group, the content of IL-1β in rat serum of the MZWT and Lotensin groups decreased (P < 0.01) (Fig. 9b). Compared with the N group, the content of TNF-α in rat serum of the M group increased, but the difference was not statistically significant (P > 0.05) (Fig. 9a).

Fig. 9.

Impact of adenine on the production of inflammatory markers in rat serum and the modulatory effects of MZWT. Markers measured include: (a) TNF-α, (b) IL-1β. Group designations are: (N: normal group, M: model group, MZWT: Modified Zhenwu Tang group, Lotensin: benazepril hydrochloride group). Statistical comparison results: ##P < 0.01, #P < 0.05 compared with the N group; **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 compared with the M group; NS denotes no statistical significance.

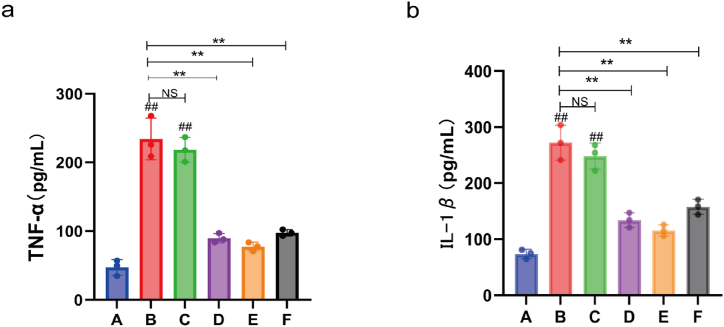

Compared with the A group, the content of IL-1β and TNF-α in cell supernatants of the B group was significantly increased (P < 0.01) (Fig. 10a and b); compared with the B group, the content of IL-1β and TNF-α in cell supernatants of the D group, E group, and F group decreased (P < 0.01) (Fig. 10a and b); compared with the B group, the content of IL-1β and TNF-α in cell supernatants of the C group was not statistically significant (P > 0.05) (Fig. 10a and b).

Fig. 10.

Release of inflammatory factors in HK-2 cell supernatants under hypoxic conditions and LPS exposure, and the effects of MZWT. Analyzed factors: (a) TNF-α, (b) IL-1β. Group designations: (A: Normal group, B: Model group, C: Blank serum group, D: Drug serum group, E: FM19G11 group, F: NAC group). Statistical significance: ##P < 0.01, #P < 0.05 compared with the A group; **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 compared with the B group; NS indicates no statistical significance.

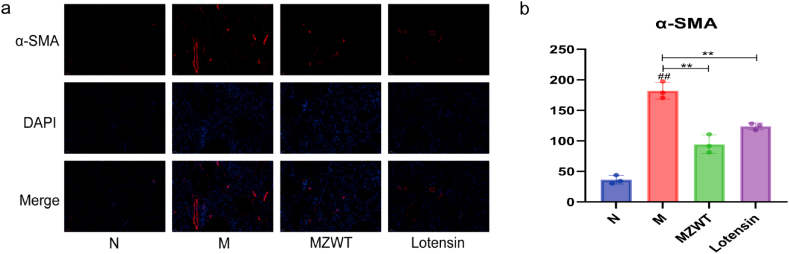

3.8. Ade gavage led to an increase in the expression of the fibroblast marker α-SMA in rat renal tissue, while MZWT could reduce its expression; hypoxia and LPS increased the expression of α-SMA and COL1A1 in HK-2 cells, and MZWT could reduce their production

In the N group, a small amount of α-SMA was expressed in the rat renal vessels (Fig. 11a and b); compared with the N group, a large amount of α-SMA was expressed in the renal vessels and proximal tubules of the M group rats (Fig. 11a and b); compared with the M group, the expression of α-SMA in the MZWT group and Lotensin group rats was significantly reduced (Fig. 11a and b).

Fig. 11.

Immunofluorescence analysis showing the impact of adenine on α-SMA expression in rat renal tissue and the modulatory effects of MZWT (IF × 200). Details of the analysis: (a) Detection of α-SMA, (b) Comparative analysis of fluorescence intensity. Groups include: (N: normal group, M: model group, MZWT: Modified Zhenwu Tang group, Lotensin: benazepril hydrochloride group). Statistical results: ##P < 0.01, #P < 0.05 compared with the N group; **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 compared with the M group; NS denotes no statistical significance.

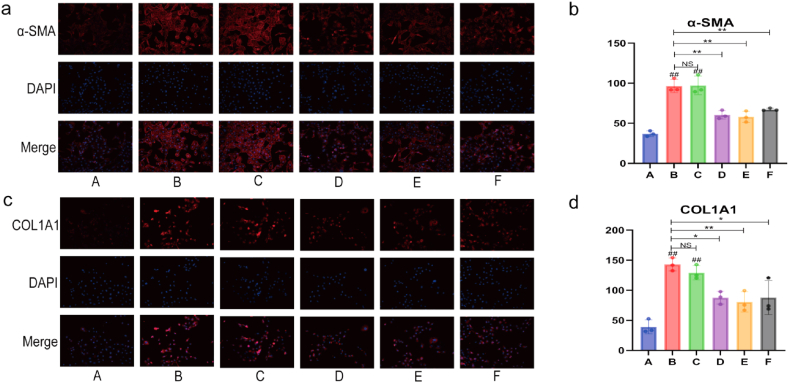

Compared with the A group, the expression of α-SMA and COL1A1 in B group cells was significantly increased (P < 0.01) (Fig. 12a–d); compared with the B group, the expression of α-SMA and COL1A1 in D group, E group, and F group cells was significantly reduced (P < 0.01, P < 0.05) (Fig. 12a–d); compared with the B group, the expression of α-SMA and COL1A1 in C group cells was not statistically significant (P > 0.05) (Fig. 12a–d).

Fig. 12.

Expression of fibrotic markers α-SMA and COL1A1 in HK-2 cells under hypoxic conditions and LPS treatment, showing reduction by MZWT (IF × 200). Details of expression: (a) α-SMA, (b) Relative intensity of α-SMA, (c) COL1A1, (d) Relative intensity of COL1A1. Groups: (A: Normal group, B: Model group, C: Blank serum group, D: Drug serum group, E: FM19G11 group, F: NAC group). Statistical significance: ##P < 0.01, #P < 0.05 compared with the A group; **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 compared with the B group; NS indicates no statistical significance.

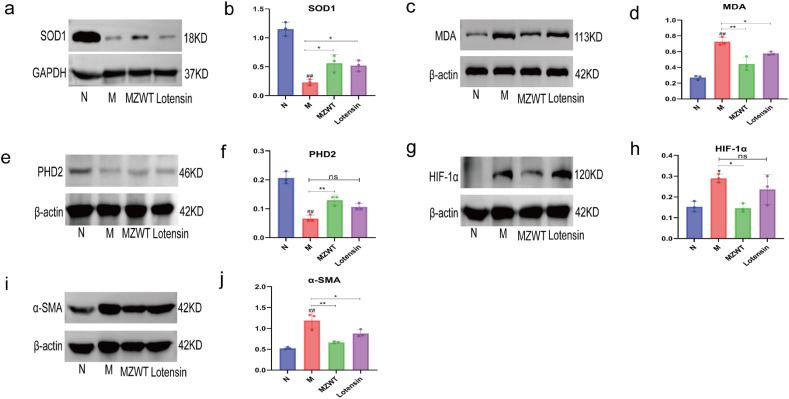

3.9. Ade gavage led to an oxidative/antioxidative imbalance and activation of the HIF signaling pathway in rat renal tissue, leading to fibrosis, while MZWT alleviated these changes; hypoxia and LPS activated the HIF signaling pathway in HK-2 cells, and MZWT inhibited it

Compared with N group rats, the expression of MDA, HIF-1α, and α-SMA proteins in M group rats was significantly increased (P < 0.01) (Fig. 13c, d, g, h, i, j), while the expression of SOD1 and PHD2 proteins was significantly reduced (P < 0.01) (Fig. 13a, b, e, f). Compared with M group rats, the expression of MDA, HIF-1α, and α-SMA proteins in the MZWT group and Lotensin group rats decreased (P < 0.05) (Fig. 13c, d, g, h, i, j), while the expression of SOD1 and PHD2 proteins increased (P < 0.05) (Fig. 13a, b, e, f).

Fig. 13.

Effects of adenine on oxidative stress markers and the HIF pathway in rat proximal renal tubules, with improvement shown by MZWT. Measured indices: (a, c, e, g, i) Expression of SOD1, MDA, PHD2, HIF-1α, and α-SMA. (b, d, f, h, j) Relative expression levels of each index. Groups are as follows: (N: normal group, M: model group, MZWT: Modified Zhenwu Tang group, Lotensin: benazepril hydrochloride group). Statistical significance is noted as: ##P < 0.01, #P < 0.05 compared with the N group; **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 compared with the M group; NS denotes no statistical significance.

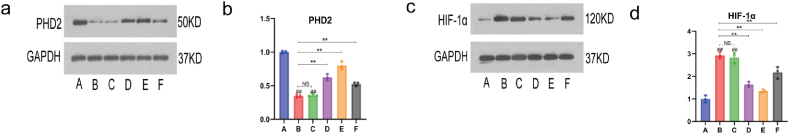

Compared with the A group, the expression of PHD2 protein in B group cells was significantly reduced (P < 0.01) (Fig. 14a and b), while the expression of HIF-1α protein was significantly increased (P < 0.01) (Fig. 14c and d); compared with the B group, the expression of PHD2 protein in D group, E group, and F group cells increased (P < 0.01) (Fig. 14a and b), while the expression of HIF-1α protein decreased (P < 0.01) (Fig. 14c and d). Compared with the B group, the expression of HIF-1α and PHD2 proteins in C group cells was not statistically significant (P > 0.05) (Fig. 14a, b, c, d).

Fig. 14.

Inhibition of the HIF pathway by MZWT in HK-2 cells exposed to hypoxia and LPS. Analyzed proteins: (a, c) Expression of PHD2 and HIF-1α, (b, d) Relative expression levels. Groups include: (A: Normal group, B: Model group, C: Blank serum group, D: Drug serum group, E: FM19G11 group, F: NAC group). Statistical results: ##P < 0.01, #P < 0.05 compared with the A group; **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 compared with the B group; NS means no statistical significance.

4. Discussion

MZWT is a traditional Chinese medicine formula that protects renal function and delays the progression of kidney disease, and is commonly used in the treatment of kidney-related diseases. In previous studies, we demonstrated that a low-dose Ade gavage for 12 weeks could induce abnormal renal function, proteinuria formation, lipid metabolism disorder, electrolyte disorder, TIF, and cardiovascular lesions in rats, and these lesions were alleviated by MZWT. MZWT has significant advantages in improving renal function, alleviating renal injury, and improving the survival status of rats. However, there is no uniform cell model for CRF research, and many in vitro studies have been based on in vivo experiments to verify the underlying mechanism. Thus, in vivo experiments confirmed that proximal tubular epithelial cells were in a state of OS and hypoxia, and HK-2 cells were co-treated in vitro with hypoxia and LPS to simulate the state of proximal tubular epithelial cells in vivo.

The primary function of proximal tubules is reabsorption. Given their high energy demands, primarily met by mitochondria, renal proximal tubular epithelial cells are rich in mitochondria [[25], [26], [27]]. Changes in mitochondrial morphology and function can lead to the production of mitochondrial ROS, resulting in OS. This triggers the activation of NF-κB, transforming growth factor (TGF) β, and other signaling pathways, releasing inflammatory and fibrogenic factors that contribute to TIF [[28], [29], [30], [31]].

ROS can activate NF-κB, upregulating inflammatory factors in renal tissue. This promotes leukocyte recruitment and activation, triggering a cascade of inflammatory responses and potentially causing long-term pro-inflammatory cytokine expression, leading to chronic inflammation. Activated leukocytes and macrophages can further enhance OS [32].SOD is a crucial enzymatic antioxidant that neutralizes harmful ROS by catalyzing the dismutation of superoxide anion radicals (O2−) into hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and oxygen (O2), thereby maintaining metabolic balance. GSH serves as a vital nonenzymatic antioxidant in the body, removing free radicals and other noxious substances to protect cells and tissues from OS. MDA is a byproduct of polyunsaturated fatty acid peroxidation; its overproduction can alter cell membrane structure and function. COL1A1, a key component of the extracellular matrix (ECM), contributes to the matrix's structural integrity.

In vivo experiments showed rats exhibiting abnormal renal function, electrolyte imbalance, dyslipidemia, and proteinuria. There was a decrease in SOD1 expression, an increase in MDA levels, and elevated COL1A1 expression in the tubulointerstitial space of proximal renal tubular epithelial cells. Renal tissues displayed heightened MDA protein expression, reduced SOD1 protein expression, and increased collagen fibers in the renal interstitium.

In vitro, hypoxia and LPS treatment significantly raised ROS levels in HK-2 cells, decreased SOD and GSH content in cell supernatants, and increased MDA and COL1A1 expressions. However, MZWT ameliorated these abnormalities both in vivo and in vitro. These findings highlight the critical role of OS in the progression of TIF and demonstrate that MZWT can mitigate the progression of CRF by reducing damage to renal proximal tubular epithelial cells and alleviating TIF.

In a continuous hypoxic environment, epithelial cells activate inflammatory responses and fibroblasts, leading to apoptosis, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and increased production of the ECM [33]. The HIF pathway is significantly activated by hypoxia. Increasing evidence suggests that HIF-1 not only mediates hypoxia adaptation during renal injury but also is associated with inflammation, EMT [34], and ECM deposition, contributing to pre-fibrotic changes and playing a crucial role in the onset and development of renal diseases [[35], [36], [37], [38]]. Under stress conditions such as hypoxia or inflammation, increased ROS can inhibit PHD activity, further inhibiting the hydroxylation and degradation of HIF-α [39,40]. This stabilization of HIF-α allows it to form a dimer with HIF-β and translocate to the cell nucleus, activating target genes. HIF-1 accumulation can significantly enhance TGF-β expression, promoting TIF [41]. TGF-β can also upregulate the gene expression of Nox4-NADPH oxidase or directly activate NADPH oxidase to produce ROS, forming a vicious cycle leading to renal fibrosis [[42], [43], [44]]. Moreover, HIF-1 can regulate the expression of various microRNAs, such as miR217, miR23a, and miR-21, affecting ROS generation and promoting the development of fibrosis through activation of the PI-3K signaling pathway [[45], [46], [47]]. Studies have demonstrated that HIF-1α alters the local microenvironment of the kidney by releasing inflammatory mediators, such as IL-1β and TNF-α, leading to inflammation and fibrosis [48]. TNF-α and IL-1β can influence the expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) and tissue inhibitor of MMPs 1 in proximal renal tubules through extracellular regulated protein kinases1/2 and MAPK signaling pathways, causing TIF [49]. As a biomarker of myofibroblast activation, α-SMA is relatively low in normal kidneys, but significantly increases in fibrotic kidneys, particularly within the fibrotic area. In vivo experiments showed elevated IL-1β and TNF-α expression in proximal renal tubular epithelial cells and serum; increased α-SMA protein expression in renal vascular endothelial cells and proximal renal tubular epithelial cells; increased IL-1β and TNF-α mRNA expression in renal tissue, elevated HIF-1α and α-SMA protein expression, and reduced PHD2 protein expression. In vitro experiments revealed increased IL-1β and TNF-α expression in the supernatant of HK-2 cells treated with hypoxia and LPS; elevated HIF-1α and α-SMA protein expression in cells; and decreased PHD2 protein expression, with an associated increase in the number of apoptotic cells. However, MZWT reversed these abnormalities both in vitro and in vivo. These findings indicate that hypoxic reactions, such as HIF pathway activation, increased release of inflammatory factors, EMT, and apoptosis in renal proximal tubular epithelial cells, play a significant role in the progression of renal TIF. MZWT can alleviate renal TIF and delay the progression of CRF by mitigating the hypoxic response in renal proximal tubular epithelial cells.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that OS, activation of the HIF pathway, increased release of inflammatory factors, EMT, apoptosis, and other hypoxic reactions in renal proximal tubular epithelial cells significantly contribute to the progression of CRF. MZWT mitigated TIF and delayed the progression of CRF by influencing OS and hypoxic responses in these cells. This study provides a new strategy for the clinical treatment of CRF.

Data availability statement

The data of this study is available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Ethics declarations

This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hebei Yiling Pharmaceutical Research Institute (approval number no. N2022070). Informed consent was not required for this study as it involved basic animal and cell experiments, and no clinical trials were conducted.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yuan-yuan Zhang: Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Conceptualization. Pei-pei Jin: Data curation. Deng-zhou Guo: Writing – review & editing. Dong Bian: Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Scientific Research Project of the Hebei Provincial Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2023021), the Innovation Funding Project for Doctoral Students of Hebei University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (XCXZZBS2023009).

Contributor Information

Deng-zhou Guo, Email: guodengzhou@sohu.com.

Dong Bian, Email: doctorbian@126.com.

References

- 1.Inker L.A., et al. KDOQI US commentary on the 2012 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of CKD. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2014;63(5):713–735. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.01.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mackensen-Haen S., et al. Correlations between renal cortical interstitial fibrosis, atrophy of the proximal tubules and impairment of the glomerular filtration rate. Clin. Nephrol. 1981;15(4):167–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Risdon R.A., Sloper J.C., De Wardener H.E. Relationship between renal function and histological changes found in renal-biopsy specimens from patients with persistent glomerular nephritis. Lancet. 1968;2(7564):363–366. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(68)90589-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dechenne C., et al. [Correlations between the histological, immunological and clinical data obtained in analysis of 354 renal biopsies] Minerva Nefrol. 1973;20(4):252–264. PMID: 4789745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Healy E., Brady H.R. Role of tubule epithelial cells in the pathogenesis of tubulointerstitial fibrosis induced by glomerular disease. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 1998;7(5):525–530. doi: 10.1097/00041552-199809000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nangaku M. Hypoxia and tubulointerstitial injury: a final common pathway to end-stage renal failure. Nephron Exp. Nephrol. 2004;98(1):e8–e12. doi: 10.1159/000079927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hodgkins K.S., Schnaper H.W. Tubulointerstitial injury and the progression of chronic kidney disease. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2012;27(6):901–909. doi: 10.1007/s00467-011-1992-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tirichen H., et al. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and their contribution in chronic kidney disease progression through oxidative stress. Front. Physiol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2021.627837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tomás-Simó P., et al. Oxidative stress in non-dialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2021;18(15) doi: 10.3390/ijerph18157806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vodošek Hojs N., et al. Oxidative stress markers in chronic kidney disease with emphasis on diabetic nephropathy. Antioxidants. 2020;9(10) doi: 10.3390/antiox9100925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tariq A., et al. Systemic redox biomarkers and their relationship to prognostic risk markers in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease and IgA nephropathy. Clin. Biochem. 2018;56:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2018.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang H., et al. Icariin inhibits intestinal inflammation of DSS-induced colitis mice through modulating intestinal flora abundance and modulating p-p65/p65 molecule. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 2021;32(4):382–392. doi: 10.5152/tjg.2021.20282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen M.P., et al. Glycated albumin increases oxidative stress, activates NF-kappa B and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), and stimulates ERK-dependent transforming growth factor-beta 1 production in macrophage RAW cells. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 2003;141(4):242–249. doi: 10.1067/mlc.2003.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Habas E., et al. Anemia and hypoxia impact on chronic kidney disease onset and progression: review and updates. Cureus. 2023;15(10) doi: 10.7759/cureus.46737. Sr. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu J., et al. Hypoxia, HIF, and associated signaling networks in chronic kidney disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18(5) doi: 10.3390/ijms18050950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanaka T. A mechanistic link between renal ischemia and fibrosis. Med. Mol. Morphol. 2017;50(1):1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00795-016-0146-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nangaku M. Chronic hypoxia and tubulointerstitial injury: a final common pathway to end-stage renal failure. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2006;17(1):17–25. doi: 10.1681/asn.2005070757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang M.J., et al. Targeted VEGFA therapy in regulating early acute kidney injury and late fibrosis. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2023;44(9):1815–1825. doi: 10.1038/s41401-023-01070-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sugahara M., Tanaka T., Nangaku M. Hypoxia-inducible factor and oxygen biology in the kidney. Kidney. 2020;1(9):1021–1031. doi: 10.34067/kid.0001302020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsumoto M., et al. Hypoperfusion of peritubular capillaries induces chronic hypoxia before progression of tubulointerstitial injury in a progressive model of rat glomerulonephritis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2004;15(6):1574–1581. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000128047.13396.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chade A.R. Renovascular disease, microcirculation, and the progression of renal injury: role of angiogenesis. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2011;300(4):R783–R790. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00657.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shridhar P., et al. MDM2 regulation of HIF signaling causes microvascular dysfunction in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2023;148(23):1870–1886. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.123.064332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han W.Q., et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl-hydroxylase-2 mediates transforming growth factor beta 1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in renal tubular cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1833(6):1454–1462. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greijer A.E., van der Wall E. The role of hypoxia inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) in hypoxia induced apoptosis. J. Clin. Pathol. 2004;57(10):1009–1014. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2003.015032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu C., et al. A new LKB1 activator, piericidin analogue S14, retards renal fibrosis through promoting autophagy and mitochondrial homeostasis in renal tubular epithelial cells. Theranostics. 2022;12(16):7158–7179. doi: 10.7150/thno.78376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu L., et al. Twist1 downregulation of PGC-1α decreases fatty acid oxidation in tubular epithelial cells, leading to kidney fibrosis. Theranostics. 2022;12(8):3758–3775. doi: 10.7150/thno.71722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qian L., et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 (PGC-1) family in physiological and pathophysiological process and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):50. doi: 10.1038/s41392-024-01756-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zelikson N., et al. Wnt signaling regulates chemokine production and cell migration of circulating human monocytes. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024;22(1):229. doi: 10.1186/s12964-024-01608-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Donate-Correa J., et al. Klotho, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial damage in kidney disease. Antioxidants. 2023;12(2) doi: 10.3390/antiox12020239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou L.L., et al. The receptor of advanced glycation end products plays a central role in advanced oxidation protein products-induced podocyte apoptosis. Kidney Int. 2012;82(7):759–770. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang H., Xu R., Wang Z. Contribution of oxidative stress to HIF-1-Mediated profibrotic changes during the kidney damage. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021;2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/6114132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pu G., et al. mmu-miR-374b-5p modulated inflammatory factors via downregulation of C/EBP β/NF-κB signaling in Kupffer cells during Echinococcus multilocularis infection. Parasit Vectors. 2024;17(1):163. doi: 10.1186/s13071-024-06238-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rahbar Saadat Y., et al. Ischemic tubular injury: oxygen-sensitive signals and metabolic reprogramming. Inflammopharmacology. 2023;31(4):1657–1669. doi: 10.1007/s10787-023-01232-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manotham K., et al. Transdifferentiation of cultured tubular cells induced by hypoxia. Kidney Int. 2004;65(3):871–880. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thévenod F., Schreiber T., Lee W.K. Renal hypoxia-HIF-PHD-EPO signaling in transition metal nephrotoxicity: friend or foe? Arch. Toxicol. 2022;96(6):1573–1607. doi: 10.1007/s00204-022-03285-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ghajar-Rahimi G., et al. Identification of cytoprotective small-molecule inducers of heme-oxygenase-1. Antioxidants. 2022;11(10) doi: 10.3390/antiox11101888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yuan X., et al. Targeting hypoxia-inducible factors: therapeutic opportunities and challenges. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2024;23(3):175–200. doi: 10.1038/s41573-023-00848-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schietke R., et al. The lysyl oxidases LOX and LOXL2 are necessary and sufficient to repress E-cadherin in hypoxia: insights into cellular transformation processes mediated by HIF-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285(9):6658–6669. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.042424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wong B.W., et al. Emerging novel functions of the oxygen-sensing prolyl hydroxylase domain enzymes. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2013;38(1):3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Majmundar A.J., Wong W.J., Simon M.C. Hypoxia-inducible factors and the response to hypoxic stress. Mol Cell. 2010;40(2):294–309. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kushida N., et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α activates the transforming growth factor-β/SMAD3 pathway in kidney tubular epithelial cells. Am. J. Nephrol. 2016;44(4):276–285. doi: 10.1159/000449323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tong J., et al. COL4A3 mutation induced podocyte apoptosis by dysregulation of NADPH oxidase 4 and MMP-2. Kidney Int Rep. 2023;8(9):1864–1874. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2023.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu Z., et al. Sodium butyrate enhances titanium nail osseointegration in ovariectomized rats by inhibiting the PKCα/NOX4/ROS/NF-κB pathways. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2023;18(1):556. doi: 10.1186/s13018-023-04013-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shvedova A.A., et al. Increased accumulation of neutrophils and decreased fibrosis in the lung of NADPH oxidase-deficient C57BL/6 mice exposed to carbon nanotubes. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2008;231(2):235–240. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shao Y., et al. Mir-217 promotes inflammation and fibrosis in high glucose cultured rat glomerular mesangial cells via Sirt1/HIF-1α signaling pathway. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2016;32(6):534–543. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jiang K., et al. miR-155-5p promotes oxalate- and calcium-induced kidney oxidative stress injury by suppressing MGP expression. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/5863617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu J.R., et al. Caloric restriction alleviates aging-related fibrosis of kidney through downregulation of miR-21 in extracellular vesicles. Aging (Albany NY) 2020;12(18):18052–18072. doi: 10.18632/aging.103591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scholz C.C., et al. Regulation of IL-1β-induced NF-κB by hydroxylases links key hypoxic and inflammatory signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(46):18490–18495. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1309718110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nee L.E., et al. TNF-alpha and IL-1beta-mediated regulation of MMP-9 and TIMP-1 in renal proximal tubular cells. Kidney Int. 2004;66(4):1376–1386. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data of this study is available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.