Abstract

Short amphipathic peptides are capable of binding to transcriptional coactivators, often targeting the same binding surfaces as native transcriptional activation domains. However, they do so with modest affinity and generally poor selectivity, limiting their utility as synthetic modulators. Here we show that incorporation of a medium-chain, branched fatty acid to the N-terminus of one such heptameric lipopeptidomimetic (LPPM-8) increases the affinity for the coactivator Med25 > 20-fold (Ki > 100 μM to 4 μM), rendering it an effective inhibitor of Med25 protein–protein interactions (PPIs). The lipid structure, the peptide sequence, and the C-terminal functionalization of the lipopeptidomimetic each influence the structural propensity of LPPM-8 and its effectiveness as an inhibitor. LPPM-8 engages Med25 through interaction with the H2 face of its activator interaction domain and in doing so stabilizes full-length protein in the cellular proteome. Further, genes regulated by Med25-activator PPIs are inhibited in a cell model of triple-negative breast cancer. Thus, LPPM-8 is a useful tool for studying Med25 and mediator complex biology and the results indicate that lipopeptidomimetics may be a robust source of inhibitors for activator-coactivator complexes.

Keywords: Coactivator, Lipopeptide, Med25, Protein–protein interaction inhibitor, Transcription factor

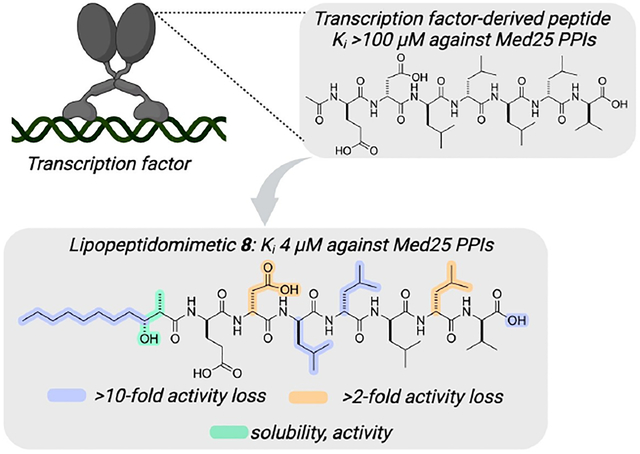

Graphical Abstract

A short, amphipathic peptide derived from transcriptional activators is transformed from a weak inhibitor of transcriptional protein–protein interactions (PPIs) to an effective inhibitor through the addition of a chiral, medium-length lipid. The resulting lipopeptidomimetic (8) selectively blocks Med25 PPIs in vitro, stabilizes full-length protein, and down-regulates a key Med25-dependent gene.

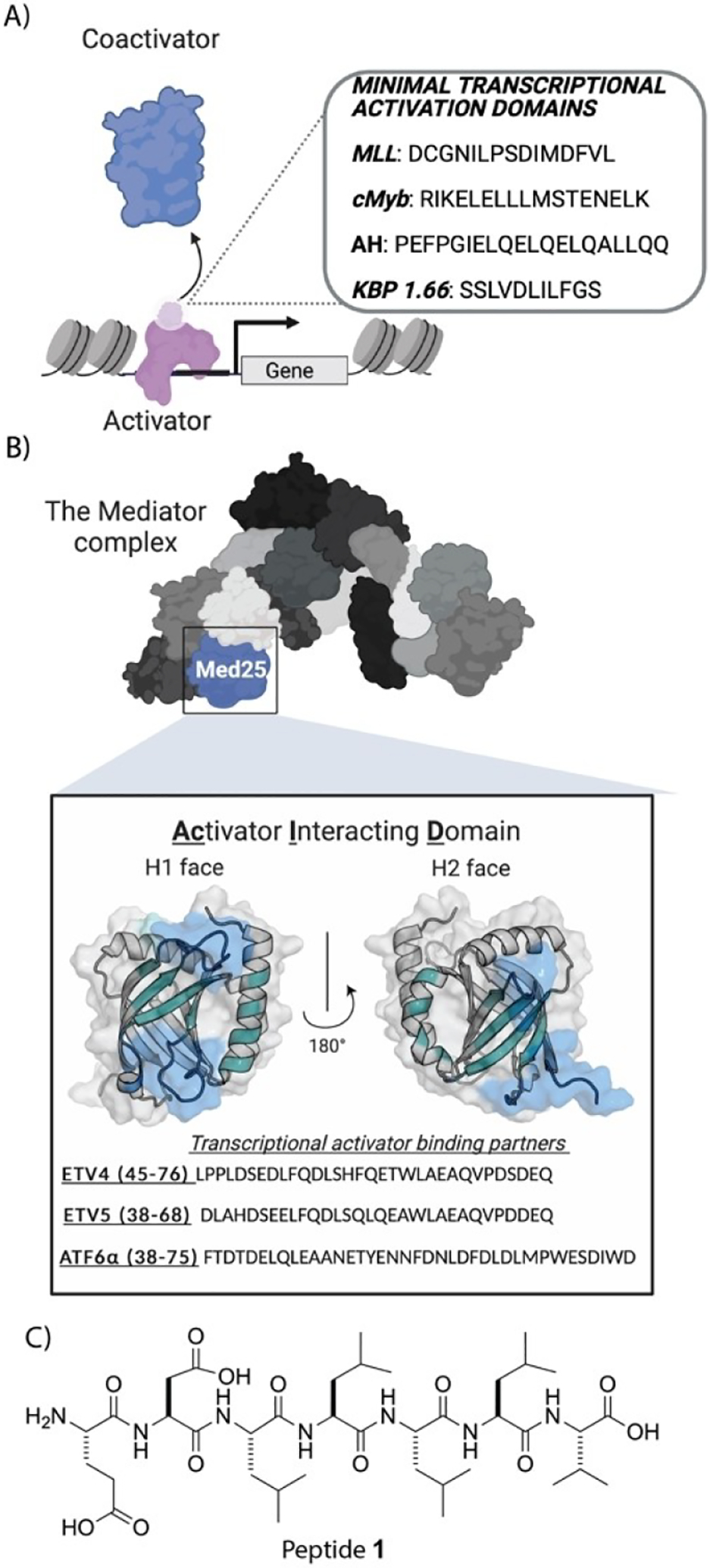

During transcription initiation, the transcriptional activation domains (TADs) of activators form protein-protein interactions (PPIs) with coactivator proteins, facilitating assembly of the transcriptional machinery.[1] The TADs are often composed of amphipathic sequences bearing a preponderance of acidic (D,E) and hydrophobic (L,V,M,F,W) residues.[2] Many lines of evidence indicate that short amphipathic peptides 7–15 amino acids in length and in either D or L configuration are sufficient to replicate the activity of native transcriptional activation domains when tethered to DNA (Figure 1A).[3,4] However, the same short sequences rarely function as effective inhibitors of TAD-coactivator interactions, as on their own they exhibit modest affinity and poor selectivity for coactivators.[3d,5] One successful approach for improving the affinity of short TADs has been to incorporate moieties that induce and/or stabilize helical secondary structures that the peptides are thought to assume upon binding to coactivators.[6] This has led, for example, to peptidomimetic inhibitors of CBP/p300 TAZ2-activator complexes that are effective in vitro and in animal models.[7] Nonetheless, given the limited structural data for many activator–coactivator complexes, a structure-independent approach to convert short amphipathic sequences into effective inhibitors would be an important addition to the field.

Figure 1.

A) Protein–protein interactions (PPIs) between coactivators (light blue) and the transcriptional activation domains (TADs; light purple) of activators (purple) underpin transcription initiation. In the adjacent box are sequences of minimal TADs from native (cMyb, MLL) or synthetic (AH, KBP 1.66) activators. On their own such sequences are poor transcriptional inhibitors. B) Med25 is a component of the Mediator complex. It uses the two binding surfaces (H1 and H2) of its Activator Interaction Domain (AcID) to complex with amphipathic activators, including the ETV/PEA3 family (ETV1, ETV4, ETV5) and ATF6α. The ETV activators complex with the H1 face, while ATF6α interacts with the H2 face of Med25 AcID.[9b–d,13] PDB entry 2XNF was used to generate figure. C) Sequence of TAD-derived amphipathic peptide 1 used in this study.

N-Terminal fatty acid acylation of short peptides has been shown to increase their efficacy, stability, and cell permeability in a variety of applications.[8] Kim and coworkers, for example, reported that the palmitoylation of a heptamer discovered in a screen for proliferation PPI modulators produced inhibitors with excellent activity in vitro and in cells.[8d] We hypothesized that such a strategy could produce more potent peptide inhibitors of activator–coactivator PPIs. To test this hypothesis, we chose the coactivator Med25 and its activator PPI network as the target (Figure 1B). Med25 is a substoichiometric component of the megadalton Mediator complex and serves to bridge Mediator and transcriptional activators during transcription initiation through PPIs with the amphipathic ETV/PEA3 family (cell migration, motility), ATF6α (stress response), and VP16 (viral infection).[9] Several lines of evidence suggest that dysregulation of Med25-activator PPIs plays a role in a number of cancers, making Med25 a potentially attractive therapeutic target.[9a,10] Med25 has also emerged as a potential lipid-binding protein, although the underlying biological role is not yet known.[11] It is, however, a highly challenging target with only a single inhibitor reported thus far.[12] With its role in disease, open questions regarding its PPI network, and lack of useful probe compounds, Med25 is an apt representative of coactivators. Here we demonstrate that lipidation of a short amphipathic peptide (peptide 1, Figure 1C) transforms a weak binder of Med25 to an effective inhibitor of Med25 protein–protein interactions (4 μM), suggesting that this may be a general strategy for converting transcription factor-derived peptides into inhibitors.

We chose as a starting point the peptide sequence EDLLLLV (peptide 1, Figure 1C), a sequence that contains a balance of hydrophobic and polar/acidic amino acids frequently observed in transcriptional activation domains, including those that interact with Med25 (Figure 1B; Figure 2A). Previous studies of TAD-coactivator interactions have shown the interchangeability of D- and L-TAD peptides, and given the more favorable stability profile of D-sequences in cellular contexts, we included enantiomeric peptides in the first set of analogs, acetylated LPPM-2, −3, −4, −5.[3d,f,4b] We also incorporated carboxy-terminal and carboxamide-terminal sequences (LPPM-2 versus −4; LPPM-3 versus −5); although native TAD sequences bear a carboxy-terminus, synthetic peptides more frequently have carboxamide moieties. The lipopeptidomimetics were assessed in a biochemical assay that measures inhibition of a pre-formed complex of Med25 AcID and the fluorescently labeled transcriptional activation domain of ATF6α, a ligand for the H2 face of AcID. Additionally, ligands were evaluated in differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) experiments with Med25 AcID alone. As shown in Figure 2A, acetylated versions of peptide 1 (LPPM-2 & LPPM-3) are poor inhibitors of the Med25-ATF6α complex (Kis: 90 and 100 μM, respectively). Results from the DSF experiments indicate modest engagement with Med25 for both analogs and the difference in ΔTm for LPPM-2 and LPPM-3 suggests that the D- and L- peptides likely use distinct binding modes to interact with the AcID motif. The C-terminal carboxamide versions, LPPM-4 and LPPM-5, showed ~2-fold better activity in the biochemical assay, although results from DSF were similar to those obtained with LPPM-2 and −3. Taken together, these data confirmed two of the starting assumptions of the work, both of which were supported by previous studies of amphipathic peptide binding and function in transcription. First, the acetylated heptamers interact with Med25, but their interaction is weak and leads to limited inhibition of the Med25-ATF6α PPI. Second, the D- and L- versions of the lipopeptidomimetics function interchangeably in the biochemical inhibition assay and given the greater stability of D-peptides in cellular environments, the D-peptide sequences were used for further studies.

Figure 2.

A & B Inhibition of Med25 AcID·ATF6α (residues 38–75) by lipopeptidomimetics 2–5 as determined by competitive fluorescence polarization assays. IC50 values were measured by titrating the lipopeptidomimetics with 20 nM FITC-ATF6α in complex with Med25 AcID (50 % bound). The IC50 values were converted to Ki values using the apparent Kd from direct binding measurements of Med25 AcID·ATF6α and using a published Ki calculator.[14] Data shown is the average of three independent experiments performed in technical triplicate with the indicated error (SD). Change in the melting temperature (ΔTm) of 8 μM Med25 AcID in the presence of 5 eq of the indicated lipopeptidomimetic as determined by differential scanning fluorimetry. Temperature-dependent unfolding was monitored using Sypro Orange fluorescence. Values represent the change in melting temperature relative to unbound Med25 AcID control. The ΔTm values are the average of two independent experiments performed in technical triplicate with the indicated error (SD).

In the next set of lipopeptidomimetics the impact of a medium-chain fatty acid on both Med25-ATF6α inhibition and Med25 engagement was assessed (Figure 2B). LPPM-6 and LPPM-7 bear an undecanoic acid (C11) tail and differ only in their C-terminus. Both analogs exhibited significantly increased activity relative to the acetylated versions (low micromolar Kis) and LPPM-6 produced a 6-fold change in Med25 Tm relative to LPPM-2, consistent with the undecanoic acid moiety contributing to a tighter binding to the protein. However, LPPM-6 and LPPM-7 displayed limited aqueous solubility and the Ki of LPPM-7 was sensitive to detergent identity and concentration, suggesting that it may function in part as an aggregate (SI Figure S5, S6, S7).[15] A common feature of bacterial lipopeptides is a β-hydroxyl group and, less frequently, α-branching.[16] Reasoning that incorporation of such functional groups would increase solubility and reduce aggregation, we incorporated (2S, 3R)-2-methyl-3-hydroxyundecanoate and (2R,3S)- 2-methyl-3-hydroxyundecanoate into analogs LPPM-8, −9, and −10. The analogs exhibited nearly identical activity in the biochemical assay, with the stereochemistry of the lipid tail having no measurable impact (Figure 2B). Further, the Kis were unaffected in a detergent screen (Supporting Information Figures S6A, S7 A). Notably, incubation of Med25 AcID with LPPM-8, or −10 induced a significant change in Tm in the DSF assay (Figure 2B). This was not the case with LPPM-9, as only a minor change in Med25 Tm (1.7°C) was observed. Taken together, the data indicate that the seemingly minor perturbation of a C-terminal carboxylate versus C-terminal carboxamide has a measurable effect on engagement of Med25.

Data from 1H,15N- and 1H,13C-heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) experiments with Med25 and either LPPM-8 or LPPM-9 indicate that LPPM-8 is a bona fide ligand of Med25 while LPPM-9 is not, consistent with the results of the DSF experiments above (Figure 3). Med25 AcID contains two binding surfaces for amphipathic activators that are allosterically connected, with activators such as ATF6α interacting with the H2 binding face and the ETV/PEA3 activators engaging the H1 surface.[9b–d,13,17] Addition of 1.1 eq of LPPM-8 resulted in several 1H,15N- and 1H,13C-HSQC chemical shift perturbations (CSPs) of residues located predominantly on the H2 binding surface of Med25 AcID (Figure 3A, 3B). The majority of residues perturbed in the 1H,13C-HSQC spectra are solvent-exposed and located on the H2 face β-barrel and flanking α-helices (α1 and α2), (Figure 3A).[13] Notable are the linear, concentration-dependent shifts of both methyl groups of L525 and of L514, suggesting that LPPM-8 interacts with more than one substructure within the binding surface. Super-stoichiometric concentrations of LPPM-8 show increased CSPs at both binding faces, though the H1 face lacked notable perturbations of solvent-exposed residues (SI Figure S12). Taken together, these data suggest that LPPM-8 directly binds to the H2 face of Med25 AcID through engagement with the β-barrel and dynamic framing helices and in doing so induces conformational changes in the protein domain. Thus, LPPM-8 is an orthosteric inhibitor of H2-binding transcriptional activators such as ATF6α and is predicted to allosterically inhibit those that bind the H1 face of Med25. Consistent with the NMR data, LPPM-8 allosterically inhibits the Med25 H1-binding ETV/PEA3 family of transcription activators (ETV1, ETV4, and ETV5) with higher Kis (Supporting Information Figure S27A).

Figure 3.

Lipopeptidomimetic LPPM-8 is a mixed allosteric/orthosteric inhibitor that engages the H2 face of Med25 AcID. A) 1H, 13C-HSQC CSPs induced by binding of 1.1 eq of LPPM-8 mapped onto Med25 AcID (PDB ID 2XNF). Yellow=0.02 ppm–0.0249 ppm, orange=0.025 ppm–0.049 ppm, red ≥ 0.0491. Overlay of 1H, 13C-HSQC CSPs of free Med25 (dark grey), 0.5 eq LPPM-8 (light blue) and 1.1 eq of LPPM-8 (green) for Med25 residues L406, L514, and L525. B) 1H, 15N-HSQC CSPs induced by binding of 1.1 eq of LPPM-8 mapped onto Med25 AcID (PDB ID 2XNF). Only residues with CSPs > 0.0851 ppm are labeled. Orange=0.0851 ppm–0.14 ppm, red ≥ 0. 141.All perturbed residues above signal to noise ratio (≥ 0.02 ppm) found in Supporting Information Figures S18–S20. C) 1H, 13C-HSQC CSPs induced by binding of 3 eq of LPPM-9 mapped onto Med25 AcID (PDB ID 2XNF). Yellow=0.02 ppm–0.0249 ppm. D)) 1H, 15N-HSQC CSPs induced by binding of 1.1 eq of LPPM-9 mapped onto Med25 AcID (PDB ID 2XNF) Yellow=0.02 ppm–0.085 ppm. All perturbed residues above signal to noise ratio (≥ 0.02 ppm) found in Supporting Information Figure S22). E) Circular dichroism spectra for N-branched LPPMs. The molar ellipticity of each sample was determined from the mean residue CD corrected for the number of amino acids and the concentration of sample using the Jasco Spectra Manager Software v.2.5.[18] CD spectra were obtained in 40 % TFE/potassium phosphate buffer. Data is representative of experiments performed in duplicate. See Supporting Information for full experimental details.

In contrast to LPPM-8, even super-stoichiometric LPPM-9 in 1H,13C-HSQC experiments leads to minimal chemical shift perturbations of Med25 residues, indicating little to no specific binding to Med25 (Figure 3C, 3D). Subsequent circular dichroism studies of LPPM-8 and LPPM-9 reveal that the identity of the C-terminal moiety correlates with a significant change in structural propensity that is likely the origin of the difference in Med25 engagement for the two structures (Figure 3E; Supporting Information Figures S23, S24). LPPM-9 has measurable α-helix character (207, 221 nm) while LPPM-8 and LPPM-10 show strong absorbance at 204 nm, suggestive of polyproline helical character. Taken together the data indicate that LPPM-9 may interfere with the amphipathic helical tracer used in the biochemical assays of Figure 2B.

The studies of Figure 2 and 3 revealed the key contributions of the lipid tail and the C-terminal functionality to engagement with Med25. To identify the amino acid residues that contribute to most to inhibition of Med25, an alanine scan of LPPM-8 was carried out (Figure 4A), using the biochemical inhibition assay of the Med25-ATF6α complex as the assessment; DSF was also completed for each of the analogs (Supporting Information Figure S10), as were circular dichroism measurements (Figure S26). Mutation at V7 had the least impact on inhibition, and both the CD spectra and ΔTm of this analog were nearly identical to that of parent LPPM-8. In contrast, two of the leucine residues, L3 and L4, clearly play an important role in inhibition and structure, as mutation to alanine leads to significant loss in activity and a change in the CD spectra (Supporting Information Figure S26). However, mutation of L5 or L6 has a minimal effect on inhibition. Of the two polar residues, E1 appears to be more important for Med25 binding than D2 (~4-fold change in Ki). Taken together, these data support a model in which individual amino acids within the sequence specifically contribute to binding to Med25 and to peptide conformation.

Figure 4.

A) Inhibition of Med25 AcID·ATF6α by alanine derivatives of LPPM-8 as determined by competitive fluorescence polarization assays. Apparent IC50 values were determined through titration of compound for Med25 AcID·ATF6α in experimental triplicate with the indicated error (SD). The IC50 values were converted to Ki values using the apparent Kd value based on the direct binding of Med25 AcID·ATF6α.[14] Data shown is the average of three independent experiments with the indicated error (SD). B) Selectivity of LPPM-8 for Med25 AcID as determined by the inhibition of related PPI networks using competitive fluorescence polarization assays. IC50 values using a suite of coactivators bound to FITC-activators at 20 nM (CBP KIX·MLL/Myb/pKID, CBP IBiD·ACTR). The IC50 values were converted to Ki values using a published Ki calculator[14] and the corresponding Kd value of each coactivator·activator direct binding measurement. Med25 AcID·ATF6α, CBP KIX·MLL/Myb, CBP KIX·pKID, CBP TAZ1·HIF1α data shown is the average of three independent experiments performed in technical triplicate with the indicated error (SD). ARC105·SREBP1a and CBP IBiD·ACTR data shown is the average of two independent experiments performed in technical triplicate with the indicated error (SD). No error bars are shown for the IC50 against CBP KIX·Myb because the IC50 was greater than the highest concentration of LPPM-8 tested (300 μM), and thus, we can accurately report the IC50 only as > 300 μM. D) LPPM-8 stabilizes full length Med25 in VARI068 cell extracts. Cellular thermal shift assays (CETSA) were performed by dosing VARI068 nuclear extracts with 25 μM LPPM-8 or equivalent DMSO and subjecting the samples to increasing temperatures. western blots using a Med25 antibody show an increased band intensity in LPPM-8-dosed samples compared to the DMSO treatment, indicating thermal shift stabilization and target engagement. Data in the bar graph is normalized to the DMSO control (grey) that is equal to 1. Data shown is representative of experiments performed in biological duplicates. Replicates and full, uncropped blots are shown in Supporting Information Figure S30. D) LPPM-8 inhibits a Med25-dependent gene in VARIO68 cells. Analysis and quantification of the transcript levels of the Med25·ETV5-dependent gene MMP2 in the triple-negative breast cancer cell line VARI068 was performed using qPCR. Results indicate that treatment with LPPM-8 results in the decrease of MMP2 transcript levels. By comparison, increasing concentrations of LPPM-9 do not yield changes in MMP2 transcript levels. Values are normalized to the reference gene RPL19. Data shown is the average of three independent experiments each performed in technical triplicate with the indicated error (SD).

Selective engagement of a particular coactivator is often a significant challenge even for transcriptional activation domains from native transcription factors. For example, p53-derived transcriptional activation domains interact with CBP/p300 TAZ1, TAZ2, KIX, and IBiD as well as Med25 AcID.[19] We have previously shown that engagement of dynamic substructures within coactivators such as Med25 produces inhibitors selective for their cognate coactivator and the NMR data of Figure 3 indicates that LPPM-8 engages with several such substructures in Med25 AcID.[12] The selectivity of LPPM-8 for Med25 relative to a broader range of coactivator–activator complexes was thus evaluated in a series of competitive inhibition assays previously used for assessing coactivator inhibitor selectivity (Figure 4B).[12,20] LPPM-8 showed very good selectivity, with > 6-fold preference for Med25 across the range of coactivator-activator complexes tested.

As noted earlier, Med25 is a multi-domain protein and we next tested if LPPM-8 could engage the full-length protein. For this we utilized the triple negative breast cancer cell line VARI068 that, as previously described, exhibits upregulated Med25 and its cognate ETV/PEA3 activator binding partners.[12] Incubation of freshly prepared VARI068 nuclear extracts with LPPM-8 led to stabilization of endogenous Med25 relative to DMSO-treated samples, consistent with LPPM-8 engagement of AcID in the context of endogenous, full-length Med25 (Figure 4C, Supporting Information Supporting Information Figure S30). In contrast, the addition of LPPM-9 has little effect on endogenous Med25 stability (Supporting Information Figure S31). We further probed LPPM-8 engagement of Med25 by the testing its effect on a key Med25-dependent gene, MMP2, in VARI068 cells.[12] Treatment with LPPM-8 downregulated MMP2 gene expression, while treatment with negative control LPPM-9 did not (Figure 4D). Given these collective data, future efforts with LPPM-8 will include a broader examination of its specific effects on the Med25 PPI network in cells and the concomitant transcriptional changes.

Med25 is a canonical coactivator in that it serves as an interaction hub for a variety of amphipathic transcription factors; yet, like other coactivators, the amphipathic sequences within the transcription factors are not effective inhibitors. Here we have demonstrated that incorporation of a branched fatty acid at the N-terminus of a short (7-residue) amphipathic peptide leads to > 20-fold increase in potency against Med25-activator PPIs in vitro and very good selectivity. Further, the lead inhibitor, LPPM-8, engages full-length Med25 in the cellular proteome and preliminary results indicate that LPPM-8 down-regulates a key Med25-dependent gene. Given the role that lipid structure and amino acid sequence play in the function of the lipopeptidomimetics examined here, future work includes assessing lipopeptidomimetics differing in both amino acid sequence and lipid architectures for increased potency, selectivity, and for targeting a broader range of coactivators. Taken together, our data suggest that lipopeptidomimetics can be a valuable and thus far unexplored tool for the molecular intervention on coactivators and their PPI networks.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate colleagues Prof. D.H. Sherman, Dr. A. Tripathi, and P. Schulz, who inspired this work by sharing the unpublished structure of a novel bacterial lipopeptide similar in architecture. Thank you to F. Gu for synthesis assistance. The authors acknowledge financial support from the National Institutes of Health (GM136356 to A.K.M.; NIH-P30CA046592 to the Rogel Cancer Center Core) and the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (to SDM). Figure 1 and the Table of Contents Figure were created with Biorender.com.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Olivia N. Pattelli, Life Sciences Institute, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109 USA; Program in Chemical Biology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109 USA.

Estefanía Martínez Valdivia, Life Sciences Institute, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109 USA; Program in Chemical Biology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109 USA.

Matthew S. Beyersdorf, Life Sciences Institute, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109 USA Program in Chemical Biology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109 USA.

Clint S. Regan, Life Sciences Institute, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109 USA

Mónica Rivas, Life Sciences Institute, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109 USA.

Katherine A. Hebert, Department of Chemistry, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109 USA

Sofia D. Merajver, Department of Internal Medicine, Hematology/Oncology, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI 48109 USA

Tomasz Cierpicki, Program in Chemical Biology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109 USA; Department of Pathology, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI 48109 USA.

Anna K. Mapp, Life Sciences Institute, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109 USA; Program in Chemical Biology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109 USA; Department of Chemistry, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109 USA.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- [1].a) Mapp AK, Ansari AZ, ACS Chem. Biol 2007, 2, 62–75; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ptashne M, Gann A, Nature 1997, 386, 569–577; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Brent R, Ptashne M, Cell 1985, 43, 729–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].a) Gill G, Sadowski I, Ptashne M, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1990, 87, 2127–2131; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hope IA, Mahadevan S, Struhl K, Nature 1988, 333, 635–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].a) Ma J, Ptashne M, Cell 1987, 51, 113–119; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Giniger E, Ptashne M, Nature 1987, 330, 670–672; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Ravarani CN, Erkina TY, De Baets G, Dudman DC, Erkine AM, Babu MM, Mol. Syst. Biol 2018, 14, e8190; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Rowe SP, Mapp AK, Biopolymers 2008, 89, 578–581; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Sanborn AL, Yeh BT, Feigerle JT, Hao CV, Townshend RJ, Lieberman Aiden E, Dror RO, Kornberg RD, eLife 2021, 10; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Nyanguile O, Uesugi M, Austin DJ, Verdine GL, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 13402–13406; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Piskacek M, Vasku A, Hajek R, Knight A, Mol. BioSyst 2015, 11, 844–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].a) Mapp AK, Ansari AZ, Ptashne M, Dervan PB, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 3930–3935; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kuznetsova S, Ait-Si-Ali S, Nagibneva I, Troalen F, Le Villain JP, Harel-Bellan A, Svinarchuk F, Nucleic Acids Res 1999, 27, 3995–4000; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Stanojevic D, Young RA, Biochemistry 2002, 41, 7209–7216; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Piskacek S, Gregor M, Nemethova M, Grabner M, Kovarik P, Piskacek M, Genomics 2007, 89, 756–768; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Frangioni JV, LaRiccia LM, Cantley LC, Montminy MR, Nat. Biotechnol 2000, 18, 1080–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].a) Ramaswamy K, Forbes L, Minuesa G, Gindin T, Brown F, Kharas MG, Krivtsov AV, Armstrong SA, Still E, de Stanchina E, Knoechel B, Koche R, Kentsis A, Nat. Commun 2018, 9, 110; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Henchey LK, Kushal S, Dubey R, Chapman RN, Olenyuk BZ, Arora PS, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 941–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].a) Sawyer N, Watkins AM, Arora PS, Acc. Chem. Res 2017, 50, 1313–1322; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lao BB, Drew K, Guarracino DA, Brewer TF, Heindel DW, Bonneau R, Arora PS, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 7877–7888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kushal S, Lao BB, Henchey LK, Dubey R, Mesallati H, Traaseth NJ, Olenyuk BZ, Arora PS, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 15602–15607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].a) Patra CR, Rupasinghe CN, Dutta SK, Bhattacharya S, Wang E, Spaller MR, Mukhopadhyay D, ACS Chem. Biol 2012, 7, 770–779; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Szałaj N, Benediktsdottir A, Rusin D, Karlén A, Mowbray SL, Więckowska A, Eur. J. Med. Chem 2022, 238, 114490; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Mao Y, Yu L, Mao M, Ma C, Qu L, J. Pept. Sci 2018, 24; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Nim S, Jeon J, Corbi-Verge C, Seo MH, Ivarsson Y, Moffat J, Tarasova N, Kim PM, Nat. Chem. Biol 2016, 12, 275–281; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Zhang L, Bulaj G, Curr. Med. Chem 2012, 19, 1602–1618; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Kowalczyk R, Harris PWR, Williams GM, Yang SH, Brimble MA, Adv. Exp. Med. Biol 2017, 1030, 185–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].a) Verger A, Baert J-L, Verreman K, Dewitte F, Ferreira E, Lens Z, de Launoit Y, Villeret V, Monté D, Nucleic Acids Res 2013, 41, 4847–4859; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Vojnic E, Mourão A, Seizl M, Simon B, Wenzeck L, Larivière L, Baumli S, Baumgart K, Meisterernst M, Sattler M, Cramer P, Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 2011, 18, 404–409; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Landrieu I, Verger A, Baert J-L, Rucktooa P, Cantrelle F-X, Dewitte F, Ferreira E, Lens Z, Villeret V, Monté D, Nucleic Acids Res 2015, 43, 7110–7121; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Sela D, Conkright JJ, Chen L, Gilmore J, Washburn MP, Florens L, Conaway RC, Conaway JW, J. Biol. Chem 2013, 288, 26179–26187; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Mittler G, Stühler T, Santolin L, Uhlmann T, Kremmer E, Lottspeich F, Berti L, Meisterernst M, EMBO J 2003, 22, 6494–6504; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) El Khattabi L, Zhao H, Kalchschmidt J, Young N, Jung S, Van Blerkom P, Kieffer-Kwon P, Kieffer-Kwon K-R, Park S, Wang X, Krebs J, Tripathi S, Sakabe N, Sobreira DR, Huang S-C, Rao SSP, Pruett N, Chauss D, Sadler E, Lopez A, Nóbrega MA, Aiden EL, Asturias FJ, Casellas R, Cell 2019, 178, 1145–1158.e1120; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Richter WF, Nayak S, Iwasa J, Taatjes DJ, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 2022, 23, 732–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Pellecchia A, Pescucci C, De Lorenzo E, Luceri C, Passaro N, Sica M, Notaro R, De Angioletti M, Oncogenesis 2012, 1, e20–e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Niphakis MJ, Lum KM, Cognetta AB 3rd, Correia BE, Ichu TA, Olucha J, Brown SJ, Kundu S, Piscitelli F, Rosen H, Cravatt BF, Cell 2015, 161, 1668–1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Garlick JM, Sturlis SM, Bruno PA, Yates JA, Peiffer AL, Liu Y, Goo L, Bao L, De Salle SN, Tamayo-Castillo G, Brooks CL 3rd, Merajver SD, Mapp AK, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2021, 143, 9297–9302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Henley MJ, Linhares BM, Morgan BS, Cierpicki T, Fierke CA, Mapp AK, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 27346–27353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Nikolovska-Coleska Z, Wang R, Fang X, Pan H, Tomita Y, Li P, Roller PP, Krajewski K, Saito NG, Stuckey JA, Wang S, Anal. Biochem 2004, 332, 261–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Feng BY, Shoichet BK, Nature Protocols 2006, 1, 550–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].a) Sukmarini L, Mar. Drugs 2022, 20; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Cronan JE, Thomas J, Methods Enzymol 2009, 459, 395–433; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Tareq FS, Lee MA, Lee HS, Lee JS, Lee YJ, Shin HJ, Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 871–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Henderson AR, Henley MJ, Foster NJ, Peiffer AL, Beyersdorf MS, Stanford KD, Sturlis SM, Linhares BM, Hill ZB, Wells JA, Cierpicki T, Brooks CL 3rd, Fierke CA, Mapp AK, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 8960–8965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Wang D, Chen K, Kulp JL, Arora PS, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 9248–9256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].a) Lee CW, Ferreon JC, Ferreon AC, Arai M, Wright PE, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 19290–19295; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lee MS, Lim K, Lee MK, Chi SW, Molecules 2018, 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Joy ST, Henley MJ, De Salle SN, Beyersdorf MS, Vock IW, Huldin AJL, Mapp AK, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2021, 143, 15056–15062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.