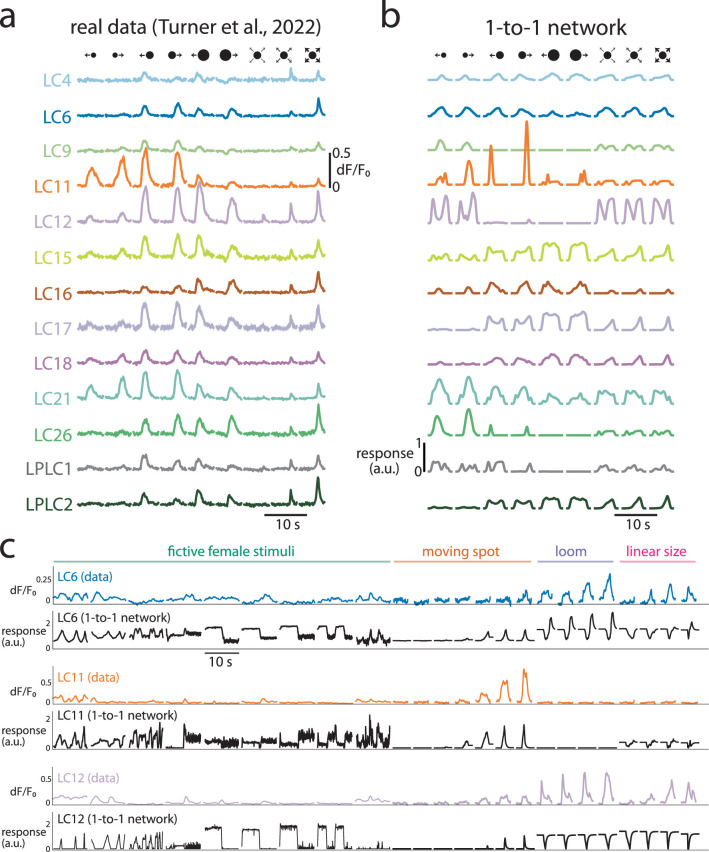

Extended Data Fig. 7. Predicting real LC responses to artificial stimuli and predicting response magnitude.

a. In addition to our own recordings, we further tested the 1-to-1 network’s neural predictions on a large number of LC neuron types whose responses were recorded in another study31. One caveat was that these responses were recorded from females, not males. We considered responses to artificial stimuli of laterally moving spots with different diameters and different movement directions as well as looming spots with different loom accelerations (top row). Traces denote responses averaged over repeats and flies, shaded regions denote 1 s.e.m. (some regions are small enough to be hidden by the mean traces). Data same as in Fig. 3a of ref. 31. b. Model LC responses from the 1-to-1 network. We fed as input the same stimuli but changed the spot to a fictive female facing forward (to better match these artificial stimuli to the fictive female stimuli on which the 1-to-1 network was trained). For visual comparison, we matched the mean and standard deviation (taken across all stimuli) of each LC type’s model responses to those of the real LC responses; we also flipped the sign of a model LC unit’s responses to ensure a positive correlation with the real LC type (flipping was only performed for LC6 and LC21). To account for adaptation effects, model LC unit’s responses decayed to their initial baseline after no change in the original responses occurred (see Methods). Overall, it appeared that almost all the real LC neurons and model LC units respond to these artificial stimuli. Some of the best qualitative matches were LC11—where the 1-to-1 network correctly identified the object size selectivity of LC11 neurons27—LC15, LC17, and LC21. A failure of the model was predicting LC12 responses; this was true of our LC recordings as well (c and Extended Data Fig. 8). This failure may be due to an unlucky random initialization, as networks trained with knockout over 10 training runs were not in strong agreement of LC12’s responses (Extended Data Fig. 6). Another explanation is that LC12 only weakly contributes to behavior for these simplified stimuli. If this were the case, then KO training would not be able to identify LC12’s contributions to behavior nor its neural activity. One piece of evidence that this might be the explanation is that solely inactivating LC12 for simple, dynamic stimulus sequences did not lead to any change in the model’s behavioral output (Fig. 4f). For natural stimulus sequences, LC12 does appear to play a role (Fig. 4c), motivating the use of more naturalistic stimuli when recording from LC types (Fig. 2). c. We continued to test the 1-to-1 network’s neural predictions by comparing the model’s response magnitudes for different types of stimuli. We wondered whether the relative magnitudes of model LC responses across all stimulus sequences qualitatively matched that of real LC responses. If so, it indicates that the model’s selectivity for certain stimuli matches real LC selectivity. This is different from our quantitative comparisons that normalized model LC responses for each stimulus separately (Fig. 2d,e and Extended Data Fig. 8). We note that a priori, we would not expect the 1-to-1 network to predict response magnitude, as downstream weights could re-scale any activity of the model LC units. However, as found when comparing the internal representations of deep neural networks to one another60, the relative magnitudes of internal units may be an important part of encoding informative representations. Same format as in Fig. 2f for the three remaining recorded LC types (LC6, LC11, and LC12). For LC6, the 1-to-1 network correctly predicts a larger response to loom than responses to a moving spot and a spot varying its size linearly (‘linear size’); however, it overestimates the responses to fictive female stimuli. For LC11, the model accurately identifies LC11’s object selectivity (‘moving spot’) and suppression to loom and linear size. Similar to LC6, the 1-to-1 network overestimates LC11’s response magnitudes to the fictive female stimuli. We again found that for LC12, the 1-to-1 network has overly large responses to the fictive female stimuli but does predict magnitudes for moving spot, loom, and linear size. The model LC12 responses to loom and linear size appear to be inverted (i.e., flipping model LC12 responses to loom and linear size would better match the real LC12 responses)—this is likely a consequence of the fact that the sign of an LC’s response is unidentifiable for the 1-to-1 network, as one could simply flip the sign of the model LC unit’s response and the readout weights of downstream units. Other possible reasons are mentioned in b.