Abstract

Teacher innovation is crucial for the education system to adapt to contemporary society's evolving demands. However, the underlying mechanism of how inclusive leadership positively impacts employees’ innovative behavior remains incomplete. Therefore, drawing upon the social cognitive theory, this study aims to comprehensively examine the mediating effects of teachers’ psychological empowerment and school innovation climate on the relationship between inclusive leadership and innovative behavior among primary and junior teachers. A total of 358 valid questionnaires were administered to primary and junior teachers in mainland China using a convenience sampling approach. The data were analyzed using hierarchical linear modeling and bootstrap testing, revealing a positive relationship between principal inclusive leadership and teacher innovative behavior. Additionally, teachers’ psychological empowerment and school innovation climate were found to mediate this relationship, with the former playing a crucial role. The findings can enhance existing research on the impact of inclusive leadership in basic education. They also offer a new perspective for analyzing how inclusive leadership affects employees’ innovative behavior and provide valuable insights into stimulating innovation among primary and junior teachers.

Keywords: Inclusive leadership, School innovation climate, Teacher psychological empowerment, Teacher innovative behavior, Cross-level analysis

Subject terms: Human behaviour, Environmental social sciences, Psychology and behaviour

Introduction

The cultivation of innovative behavior is crucial for enhancing organizational efficiency and effectiveness in today’s rapidly evolving technological landscape and interconnected global communication1. In education, teacher innovative behavior is paramount as teachers serve as the backbone of the system and are indispensable in addressing challenges posed by rapid technological advancements and globalization2,3. Their ability to exhibit innovative behavior is vital in ensuring the system remains adaptable, dynamic, and responsive to current developments4–6. Therefore, fostering teacher innovative behavior becomes imperative for continuous progress in education.

Principal leadership is a crucial environmental factor that influences teacher innovative behavior7. Previous studies have investigated the impact of transformational leadership8, distributed leadership9, and empowering leadership10,11 on teacher innovative behavior. With the emergence of a new generation of teachers in mainland China, there is an increasing differentiation and diversification in their ideas, personalities, habits, and behaviors. Consequently, they expect schools to acknowledge and foster their uniqueness. This necessitates school leaders who can accommodate and support these diverse ideas and behaviors. However, more research is needed in the current literature regarding the influence of principal inclusive leadership on teacher innovative behavior, despite evidence demonstrating that inclusive leadership stimulates employee innovative behavior within the business sector12,13.

Previous studies have primarily examined the influence of inclusive leadership on employee innovation behavior through external organizational factors and internal psychological factors. From an external perspective, research has shown that inclusive leadership can stimulate innovative behavior by influencing the organization to support employees14, promoting knowledge sharing within the organization15,16, and fostering a climate of innovation15. From an internal perspective, studies have explored how inclusive leadership can enhance employee motivation12,17, psychological safety18–21, psychological empowermentt22, psychological capital23,24, and self-efficacy24 to promote innovative behavior. The two perspectives play a significant role in elucidating employee innovative behavior, yet they possess certain limitations: the external organizational culture perspective primarily emphasizes interpersonal interaction while overlooking individual factors; conversely, the inner individual psychological perspective tends to isolate individuals from groups and neglects the significance of group connection and support25. Therefore, it may be challenging to systematically understand the impact of inclusive leadership on employee innovative behaviors from a singular perspective, such as external organizational culture or internal individual psychology.

The Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) provides a comprehensive framework for understanding how behavior is influenced by personal, behavioral, and environmental factors26. In the educational context, SCT is particularly relevant for studying the relationship between leadership and teacher behavior. As an environmental factor, principal inclusive leadership indirectly influences teacher innovative behavior by shaping both the external school culture and the internal psychological states of teachers, aligning with SCT’s perspective on the dynamic interaction between environmental determinants and cognitive processes. Psychological empowerment, a pivotal cognitive mediator within SCT, is characterized by an individual belief in their capabilities to perform a task effectively. When school leaders exhibit inclusive behaviors, they can bolster teacher self-efficacy, thereby encouraging a greater propensity for innovation. Additionally, the school innovation climate, which is about the collective beliefs regarding the value and support for innovation within a school, directly affects teachers’ innovation motivation and behavior. At the same time, because of its inclusive characteristics, inclusive principals can easily form an innovative school climate.

Our research aims to comprehensively examine the intricate relationship between principal inclusive leadership and teacher innovative behavior, specifically investigating the mediating roles of teachers’ psychological empowerment and the school innovation climate. These mediating variables are fundamental components of Social Cognitive Theory (SCT), representing cognitive and environmental mechanisms through which leadership exerts influence. By integrating these concepts, our study provides a comprehensive understanding of how inclusive leadership can foster an environment conducive to teacher innovation, thereby contributing to the existing literature in this field. Furthermore, this study offers practical insights for educational administrators seeking to nurture innovative behaviors among teachers.

Literature review and hypothesis development

Principal inclusive leadership and teacher innovative behavior among primary and junior teachers

The impact of inclusive leadership on employees’ innovative behavior has been confirmed, and this leadership style can promote the entire process of employees' innovative behavior. Inclusive leadership engages employees in the decision-making process and encourages employees to speak openly27, which promotes the generation of new ideas28. Support from inclusive leaders in organizational resources facilitates the implementation of innovative ideas by employees29. Furthermore, inclusive leaders take responsibility for the ultimate outcomes of employee work, particularly when new ideas fail, thus encouraging employees to take more risks30,31. Literatures have also indicated that inclusive leadership can promote employee innovative behavior across different contexts18,32,33.

Although the impact of inclusive leadership on employee innovation in primary and junior education remains unexplored, we propose that inclusive principals enhance the social cognitive environment within schools by treating teachers equitably and valuing their opinions and ideas. This equitable treatment and value placement serve as vicarious experiences and verbal persuasions that can boost teacher self-efficacy, a crucial cognitive factor for fostering innovation. Inclusive principals cultivate a culture that aligns with Social Cognitive Theory's emphasis on creating a supportive environment to nurture innovation, encouraging teachers to engage in bold exploration and take responsibility for innovative endeavors. Inclusive leaders' tolerance for failure and psychological support creates a secure environment that motivates teachers to embrace innovative behaviors. Based on the aforementioned theories and empirical evidence, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1

Principal inclusive leadership positively impacts teacher innovative behavior.

The mediating role of teachers’ psychological empowerment

Psychological empowerment reflects an individual response to the behavior of empowering parties and leaders, encompassing work meaning, self-efficacy, self-determination, and influence34. Previous studies have confirmed that psychological empowerment mediates between inclusive leadership and employee innovative behavior. According to Javed et al.35, employees perceive inclusive leadership as a supportive factor that enhances their psychological empowerment and stimulates innovative behavior.

From an educational perspective, inclusive leadership is a style that encourages principals to embrace teachers' diverse educational values, create empowering policies for both teachers and students, and prioritize educational justice and democracy36. This definition suggests that principal inclusive leadership involves authorization behaviors that foster psychological empowerment among teachers37. By fostering a work environment where teachers freely express their opinions, principals enable them to make value judgments about the purpose of their work based on their own beliefs and standards, thereby enhancing the meaning in their work. Furthermore, when principals reward teachers for successes and provide supportive encouragement during failures, they contribute to the development of teacher self-efficacy. The willingness of principals to support teachers in terms of resources, policies, and other aspects promotes their ability to control or make autonomous decisions regarding their work.

A substantial body of research has consistently demonstrated that when employees feel empowered, they exhibit higher proactivity and innovation38. Teachers within a school organization possess a rich cultural background and a strong desire for spiritual fulfillment. When the school provides them a sense of purpose, competence, autonomy, and influence in their work, they are more likely to reciprocate the support by implementing educational innovations.

According to social cognitive theory, self-concept serves as a mediating factor in the relationship between external social environmental factors and individual psychology and behavior. Self-concept encompasses an individual subjective perception of their physical state, personality traits, attitudes, social roles, and past experiences, as well as their attitudes, beliefs, and values39. In the context of education, teachers' psychological empowerment is a significant aspect of their work-related self-concept, highlighting their perceived capabilities, autonomy, and influence in their professional field. Leadership style is a crucial external factor that influences employees' psychological empowerment and subsequent behavioral manifestations, as established by prior research40–42. Building on this foundation, our study hypothesizes that principal inclusive leadership—characterized by openness, inclusiveness, and supportiveness—positively impacts teachers' psychological empowerment. By fostering empowerment, inclusive leaders initiate a chain of effects that ultimately stimulate and enhance teacher innovative behavior within the educational setting. Consequently, this study posits that principal inclusive leadership positively influences teachers' psychological empowerment and subsequently impacts their innovative behavior. In summary, the following hypotheses are formulated:

Hypothesis2

Teachers’ psychological empowerment mediates the relationship between principal inclusive leadership and teacher innovative behavior.

The mediating role of school innovation climate

Ekvall believes that leadership behavior in the external environment significantly influences employees perception of organizational innovation climate43. Inclusive principals demonstrate openness by encouraging free discussions on educational matters and actively listening to teacher innovative ideas and solutions44,45, fostering a school environment that nurtures critical thinking and innovation. They also tolerate employee failures and mistakes14, creating a safe space for teachers to innovate and persist until they succeed46,47, inspiring other educators to participate in educational innovation through sharing diverse ideas and opinions, thus fostering a culture of courage and innovation within the school. Inclusive principals cultivate approachable relationships with teachers based on trust and respect, prioritizing the understanding of individual needs48 while providing essential resources for professional development. As a result, educators feel supported in cultivating an innovative climate.

Many studies have indicated that the school climate is crucial in shaping teacher innovative behavior. Such a climate can motivate teachers to learn new ideas and methods, leading them to change traditional teaching methods actively49. Schools that provide satisfaction, autonomy, and cooperation are more likely to have innovative teachers50. Additionally, Xia et al. has confirmed the relationship between innovation climate and teacher innovative behavior in mainland China higher education institutions. They concluded that a stronger school innovation climate encourages teachers to apply acquired knowledge and skills creatively in their work while solving tasks and problems with innovative approaches51. Similarly, Hou52 argues that the organizational climate of schools significantly influences the teaching innovation of primary and junior teachers.

Bandura's SCT emphasizes the role of observational learning, where individuals acquire new behaviors by observing others, particularly those in positions of authority or influence. In the context of educational institutions, principal inclusive leadership emerges as a critical environmental determinant shaping teacher behaviors and attitudes towards innovation. Specifically, the concept of reciprocal determinism within SCT underscores how individuals and their environments mutually influence each other. In this vein, principal inclusive leadership, characterized by active engagement, empowerment, and openness to diverse perspectives, constitutes a formidable environmental force that can foster a school culture conducive to innovation. As posited by Amabile et al.53, leaders play a pivotal role in either nurturing or suppressing subordinate innovative behaviors through the strategic construction of their organizational environment. Furthermore, the notion of vicarious experiences and self-efficacy embedded in SCT is pertinent to understanding how inclusive leadership can stimulate teacher innovation. As Yao54 illustrates, inclusive leadership fosters a team-level innovative climate by promoting a sense of belonging, encouraging idea sharing, and validating contributions from all team members. This climate acts as a catalyst for enhancing employees' belief in their ability to innovate—their self-efficacy—thereby stimulating innovative behavior. Accordingly, the following hypotheses are proposed in this paper:

Hypothesis H3

School innovation climate has a cross-level mediating effect between principal inclusive leadership and teacher innovative behavior.

Comparison of double mediations

Drawing from the tenets of Social Cognitive Theory (SCT), which underscores the reciprocal interplay among personal factors, behaviors, and environmental influences, our study posits that teacher psychological empowerment and the school innovative climate function as critical mediators in translating inclusive leadership into teacher innovative behavior. However, the depth of this integration necessitates a closer examination through the lens of SCT's core principles, particularly the concepts of self-efficacy, observational learning, and reciprocal determinism.

In SCT, self-efficacy, a central component of psychological empowerment, is pivotal for innovation, as it refers to an individual belief in their ability to succeed in specific tasks. When principals empower teachers by granting autonomy over educational strategies, they nurture a sense of self-efficacy, personal meaning, and professional influence among teachers55. This aligns with SCT’s emphasis on vicarious experiences, where observing successful models (inclusive leaders) inspires similar behaviors. In this context, teachers perceive their role in school improvement as integral to their self-worth, fostering intrinsic motivation and a proactive stance towards innovation, even amidst challenges.

Contrasting this with the school innovative climate, an environmental factor under SCT, while essential for setting the stage for innovative behaviors, may not independently evoke the same level of engagement without the complementary subjective empowerment. The school objective environment, representing a facilitative condition for innovation, interacts with teacher subjective states in a reciprocal manner as per SCT’s reciprocal determinism. Yet, in instances where subjective empowerment prevails, it assumes a dominant role in shaping behavior, as personal beliefs and capabilities often dictate the threshold for action, especially in the face of adversity. The study suggests that the subjective "teacher psychological empowerment" pathway exerts a stronger impact on teacher innovation behavior than the objective "school innovation climate" pathway.

Hypothesis H4

The mediating effect of teachers' psychological empowerment is more vital than that of school innovation climate.

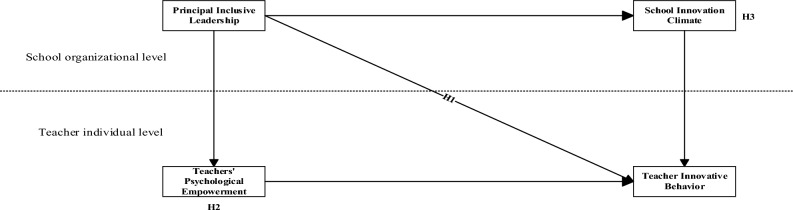

The research framework of this paper, based on the four research hypotheses, is shown in Fig. 1 below.

Figure 1.

Research framework.

Methodology

Participants and procedure

In this study, we initially imported the prepared questionnaire into the Questionnaire Star platform to generate an electronic survey instrument. The electronic questionnaires were distributed to teachers currently employed in primary and junior schools in Guangdong Province, China, utilizing convenience sampling and snowball sampling methods through social platforms such as WeChat or QQ groups. Data collection took place from June 2023 to July 2023. 369 teachers from 42 primary and junior schools voluntarily and anonymously participated in this survey. After excluding invalid questionnaires containing missing or contradictory information, a final count of 358 valid questionnaires was obtained, resulting in an effective recovery rate of 97%. The demographic information of the valid sample is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Respondent demographic data (N = 358).

| Item | Category | Percentage | Item | Category | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 56.1 | Academic title | Junior | 40.3 |

| Female | 43.9 | Medium-grade | 39.8 | ||

| Age | ≤ 25 | 19.0 | Senior | 19.9 | |

| 26–35 | 34.1 | School location | Urban | 52.9 | |

| 36–45 | 29.3 | Rural | 47.1 | ||

| ≥ 46 | 17.6 | Teaching experience (in years) | ≤ 3 | 21.8 | |

| Level of education | College and below | 31.6 | 4–10 | 37.1 | |

| Undergraduate | 57.5 | 11–20 | 28.1 | ||

| postgraduate | 10.9 | ≥ 21 | 13.0 |

Measures

To ensure our study's validity and cultural relevance, we employed established scales from western literature and meticulously translated them into Chinese through a rigorous two-step adaptation process. Firstly, bilingual experts proficient in both English and Chinese accurately captured each item original intent and meaning during translation. Subsequently, local education experts and practitioners reviewed the translated scales to ensure their suitability for our research context and participants. The content was assessed for its cultural appropriateness, relevance to the Chinese educational setting, as well as the target population comprehension level. Adjustments were made when necessary to reflect the unique nuances of the Chinese educational context while preserving the original theoretical foundations. All scale items were rated on a five-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 for strongly disagree to 5 for strongly agree), with higher scores indicating stronger agreement.

Principal inclusive leadership (PIL) is measured using a 9-item scale proposed by Carmelia et al.48, which mainly measures the three dimensions of openness, usability, and accessibility of principals. Examples of the items include: “My principal is willing to consider new ideas or suggestions from teachers” (openness), “I can always ask principal for advice if I have questions” (accessibility), and “I can find the principal to discuss new problems that arise in my job” (availability). The CFA indicated the good structural validity of the scale (X2/DF = 1.901, RMR = 0.018, RMSEA = 0.008, GFI = 0.990, IFI = 0.989, NFI = 0.991, TLI = 0.997, CFI = 0.989). The Cronbach’s α coefficient of this scale in this study was 0.871.

Teacher psychological empowerment (TPE) is measured using a 12-item scale proposed by Spreitzer34, which includes the four dimensions of competence, meaning, self-determination, and impact. Examples of the items include: "I feel that the work I do is very meaningful" (meaning), "I am confident that I have the basic ability to do a good job" (competence), "I can decide how to conduct my work" (self-determination),"I feel that I have a greater impact in my department" (impact). The CFA indicated the good structural validity of the scale (X2/DF = 2.153, RMR = 0.015, RMSEA = 0.019, GFI = 0.898, IFI = 0.974, NFI = 0.962, TLI = 0.886, CFI = 0.907). The Cronbach’s α coefficient of this scale in this study was 0.857.

Teacher innovative behavior (TIB) is measured using a 6-item scale proposed by Scott et al.56. Examples of the items include: “I search out new processes, techniques, and/or new ideas for my classes”, “I generate creative ideas”, “I promote and champions ideas to other teachers”, “I try to implement new ideas in the school”, “I develop adequate plans and schedules for the implementation of new ideas”. The CFA indicated the good structural validity of the scale (X2/DF = 1.796, RMR = 0.016, RMSEA = 0.015, GFI = 0.991, IFI = 0.977, NFI = 0.893, TLI = 0.978, CFI = 0.889). The Cronbach’s α coefficient of this scale in this study was 0.882.

The school innovation climate (SIC) is measured at the team level using the scale developed by Anderson et al.57, which includes four dimensions of vision, participation safety, task orientation, and innovation support. Examples of the items include: "Our teaching/grade subject group readily provides assistance for developing new ideas", and "Our teaching/grade subject group is dedicated to implementing innovative practices in their work." The CFA indicated the good structural validity of the scale (X2/DF = 1.792, RMR = 0.017, RMSEA = 0.016, GFI = 0.909, IFI = 0.987, NFI = 0.899, TLI = 0.974, CFI = 0.969). The Cronbach’s α coefficient of this scale in this study was 0.886.

Data analysis

The cross-level dual-mediation model in this study was analyzed using SPSS22.0, Amos 21.0, and HLM6.0 software. The data analysis and processing steps were as follows: Firstly, the reliability and validity of four latent variables were examined using SPSS and AMOS software. Secondly, the aggregation effect of potential dimensions at the team level was assessed to determine if principal inclusive leadership and school innovation climate could be elevated to the team level based on meeting the standard of internal raters' reliability and within-group correlation coefficient. Then, inter-plane relationships (e.g. TPE to TIB, PIL to SIC) were tested with AMOS, while HLM was used for cross-layer inter-variable relationships (e.g. PIL to TIB, PIL to TPE, SIC to TIB). Finally, the mediation effect of hypotheses 2 and 3 was tested using the built-in Bootstrap program in AMOS. Additionally, to compare the influence of various mediators in this study involving dual mediation (hypotheses 4), we employed the program MacKinnon’s PRODCLIN258.

Ethics statement

This study adheres to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee of Longgang Institute of Education Sciences, Shenzhen. All participants provided voluntary informed consent upon survey completion and withdraw from the study at any time. Furthermore, our data underwent anonymization procedures to ensure participant privacy.

Results

Reliability and validity test

The exploratory factor analysis was conducted for each potential variable, as presented in Table 2. The C.R. value exceeding 0.60 indicates good internal consistency of the variable. The AVE values for each latent variable in this model range from 0.458 to 0.785, demonstrating strong convergence validity for all four variables.

Table 2.

Test table of mean value, standard deviation, correlation coefficient, reliability, and validity of each latent variable (N = 358).

| Variable | M | SD | C.R | AVE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Principal inclusive leadership | 3.432 | 0.801 | 0.912 | 0.689 | 0.830 | |||

| 2. School innovation climate | 4.001 | 0.526 | 0.854 | 0.458 | 0.385** | 0.677 | ||

| 3. Teachers’ psychological empowerment | 4.208 | 0.638 | 0.802 | 0.626 | 0.419** | 0.518** | 0.791 | |

| 4. Teacher innovative behavior | 3.789 | 0.512 | 0.925 | 0.785 | 0.588** | 0.571** | 0.468** | 0.886 |

The diagonal bold data in the correlation matrix is the square root value of each variable AVE, and the lower triangle of the matrix is the Pearson correlation coefficient.

M is the mean value of the variable, SD is the standard deviation of the variable, C.R. is the constituent reliability, AVE is the average variance extracted amount.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

Correlation analysis was conducted on four variables: principal inclusive leadership, school innovation climate, teachers’ psychological empowerment, and teacher innovative behavior. The results are presented in Table 2. Principal inclusive leadership and teacher innovative behavior (r = 0.385, p < 0.01) showed a positive and significant correlation. Principal inclusive leadership positively and significantly correlated with school innovation climate (r = 0.419, p < 0.01). A positive and significant correlation existed between principal inclusive leadership and teacher psychological empowerment (r = 0.588, p < 0.01). Teacher innovative behavior exhibited a positive correlation with school innovation climate (r = 0.518, p < 0.01). Teacher psychological empowerment demonstrated a positive and significant correlation with teacher innovative behavior (r = 0.571, p < 0.01). School innovation climate displayed a positive correlation with teachers’ psychological empowerment (r = 0.468, p < 0.01). These results of the correlation analysis align with the expected correlations in the hypothesis model, providing foundational support for hypothesis testing.

If two variables have good discriminative validity, then the square root of the AVE of both variables should be higher than their correlation coefficients59. Table 2 shows the test of each variable differential validity. As can be seen from Table 2, the AVE square values of the four factors of the scale are all greater than their corresponding correlation coefficients, which proves that the scale has discriminative validity.

Data aggregation check

The variables of principal inclusive leadership and school innovation climate are measured at the team level, requiring calculation of the reliability of rater Rwg within the group and the correlation coefficient ICC within the group. Rwg compares low-level variable variance with random distribution variance to determine if adding low-level variables to high-level ones is reasonable. ICC compares member variance within a group with mean between-group variance, including individual score confidence ICC (1) and average group score confidence ICC (2). In this study, the average Rwg for principal inclusive leadership is 0.918 (> 0.7), ICC (1) value is 0.685(> 0.12), and ICC (2) value is 0.939 (> 0.6). For school innovation climate, the average Rwg is 0.879 (> 0.7), ICC (1) value is 0.607 (> 0.12), and ICC (2) value is 0.818 (> 0 0.6). Both dimensions meet the criteria. Thus, the two variables of principal inclusive leadership and school innovation climate can be extended from individual measurement scores to the group level.

Model fit test

The model fitting indexes in this study (X2/DF = 2.701, RMSEA = 0.063, GFI = 0.908, AGFI = 0.910, CFI = 0.901) indicate a strong fit for the proposed model according to Schreiber et al.60 criteria, suggesting its suitability for path coefficient analysis and hypothesis testing.

Direct effect hypothesis testing

The primary hypothesis of this study is limited to hypothesis 1, which examines the direct impact of PTL on TIB. This study also investigates the effects of other variables to comprehensively comprehend the relationship between each variable and adequately prepare for subsequent mediation hypothesis testing. The analysis results pertaining to the influence relationship between pairs of variables are presented in Table 3. The findings indicate that principal inclusive leadership significantly impacts school innovation climate, and teachers’ psychological empowerment significantly influences teacher innovation behavior (p < 0.01). Because the impact of PIL on TIB (H1), SIA on TIB, and PIL on TPE are cross-level effects, these tests were analyzed using HLM software. Here are the specific steps: Firstly, the group mean value of layer 1 is centralized, and then the zero model is tested. The intra-group correlation coefficients ICC (1) for calculating teacher innovation behavior and teachers’ psychological empowerment are 0.279 and 0.248, respectively, greater than 0.06. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct a multi-level analysis and establish a multi-level regression model for hypothesis testing. Through the results, it can be found that the influence relationship between H1 and other variables has passed the test.

Table 3.

Results of hypothesis testing.

| Level | Model | Estimation of parameters | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized estimates | S. E | C.R.(T) | p | ||

| Same level | PIL → SIA | 0.449 | 0.027 | 10.918 | *** |

| TPE → TIB | 0.508 | 0.059 | 10.239 | *** | |

| Level | Model | Estimation of parameters | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| γ00 | γ01 | σ2 | τ00 | ||

| Cross-level | Null model | 5.128*** | 0.679 | 0.269*** | |

| PIL → TIB (H1) | 4.268*** | 0.419*** | 0.501 | 0.109*** | |

| SIA → TIB | 4.368*** | 0.323*** | 0.571 | 0.068*** | |

| Null model | 5.338*** | 0.719 | 0.239*** | ||

| PIL → TPE | 4.489*** | 0.489*** | 0.558 | 0.061*** | |

***means p < 0.001, γ00 means the intercept term, γ01 means the path regression coefficient, σ2 means the residual of layer 1, and τ00 means the residual of the intercept, S. E means standard error.

Mediating effect hypothesis testing

As for the mediating effect test, the first method is the causal step method proposed by Kenny and Berron, which tends to underestimate the statistical error I rate. Sobel then developed the product of the coefficient’s method. This simple Z-value test applies only to a single intermediate variable and requires a normal distribution of data for coefficient products. In recent years, Mackinnon proposed the Bootstrap confidence interval method, which does not require normality assumption in sampling distribution and can test multiple intermediary variables applicable to small and medium-sized samples. Since this study aims to test double cross-level mediation effects, we adopt this method. In order to make the results more reliable, the coefficient product Z is used for auxiliary verification. The specific steps are as follows:

The AMOS21.0 Bootstrap function was applied, the sample number of Bootstrap was selected as 5000, the confidence interval was selected as 95%, and the maximum likelihood method was applied to perform the calculation. The Bootstrap confidence interval method is divided into two interval estimation methods: the "Bias-Corrected" method and the "Percentile" method. The total effect, indirect effect, and direct effect confidence interval estimation results obtained by the two methods on principal inclusive leadership on teacher innovative behavior are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Confidence interval estimation (N = 358).

| Model | Estimated value | Product of coefficients | Bootstrapping (5000 times) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S.E | Z | Lower (Bias) | Upper (Bias) | Lower (Percentile) | Upper (Percentile) | ||

| Total effect | |||||||

| PIL → TIB | 0.309 | 0.026 | 11.298 | 0.259 | 0.369 | 0.261 | 0.373 |

| Indirect effect | |||||||

| PIL → TIB | 0.351 | 0.031 | 10.139 | 0.289 | 0.428 | 0.279 | 0.419 |

| Direct effect | |||||||

| PIL → TIB | 0.079 | 0.073 | 2.398 | 0.012 | 0.142 | 0.007 | 0.141 |

The Bias-Corrected and Percentile 95% confidence interval of the total impact of principal inclusive leadership on teacher innovative behavior are 0.259–0.369 and 0.261–0.373, both excluding 0, and the Z-value of 11.298 is greater than 1.96. Therefore, the mediation effect may exist and can be tested in the next step. The Bias-Corrected and Percentile 95% confidence intervals of the indirect impact of principal inclusive leadership on teacher innovative behavior are 0. 289–0. 428 and 0. 279–0. 419, both excluding 0, and the Z-value of 10.139 is greater than 1.96. So mediation effect exists. Moreover, the bias-corrected and Percentile 95% confidence intervals of principal inclusive leadership on teacher innovative behavior are 0.012–0.142 and 0.007–0.141, both of which exclude 0. In addition, the Z-value of 2.398 is higher than 1.96, so it is believed that the direct influence of principal inclusive leadership on teacher innovative behavior exists. Therefore, the mediating effect of principal inclusive leadership on teacher innovative behavior belongs to a partial mediating effect.

Although indirect effects have been verified, this is only the total indirect effect between the two variables, which can only indicate that at least one mediated influence path exists. However, further research is needed to determine which specific mediating effect exists and the relative importance of these two mediating effects in the overall indirect effect. Confidence intervals were calculated using PRODCLIN2 software developed by Mackinnon to assess the strength of different mediation paths. Table 5 shows that both mediation paths have 95% confidence intervals that do not contain zero, indicating that they exist and that the tests for hypothesis 2 and 3 pass. Furthermore, the "principal inclusive leadership → teachers' psychological empowerment → teacher innovative behavior" path has most significant influence (accounting for 54.20% of the total indirect effect), highlighting psychological empowerment as a critical mediator between principal inclusive leadership and teacher innovative behavior.

Table 5.

Effect test of mediation path (N = 358).

| Mediation path | Mackinnon PRODLIN2 95% CI | Indirect standard | Impact strength (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| PIL → TPE → TIB | 0.123 | 0.226 | 0.411 | 54.20 |

| PIL → SIA → TIB | 0.062 | 0.140 | 30.30 | |

Discussion

The effect of principal inclusive leadership on teacher innovative behavior

The study found that principal inclusive leadership independently predicted teacher innovative behavior; the stronger the principal inclusive leadership is, the more teacher innovative behaviors can be stimulated. This observation is consistent with previously published literature, which demonstrated associations between inclusive leadership and innovative behaviors in Western22 and Asian societies61. Using snowball sampling, Zhong et al.62 surveyed 523 individuals and 74 leaders from 55 organizations in Shanghai and Shandong Province, China, finding a positive correlation between inclusive leadership of supervisors/managers and innovative behavior among frontline employees. This study further validates and expands research on the influence of inclusive leadership on employee innovation within the context of primary and junior education in China. The principal inclusive leadership significantly predicts teacher innovative behavior, but the specific underlying mechanisms linking this meaningful relationship remain unclear.

The mediating effects of teachers' psychological empowerment and school innovation climate

Our findings demonstrate that the relationship between principal inclusive leadership and teacher innovative behavior is mediated by two pathways, namely teachers’ psychological empowerment and school innovation climate. This is the first study to disentangle the complex interrelationships among principal inclusive leadership, teacher innovative behavior, teachers’ psychological empowerment, and school innovation climate, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. Our research advances our understanding of the underlying mechanisms linking inclusive leadership with innovative behavior.

This study has demonstrated that teachers' psychological empowerment mediated the relationship between principal inclusive leadership and teacher innovative behavior, explaining 54.2% of the overall indirect effect. This observation fortified our fourth hypothesis that principal inclusive leadership was more likely to stimulate teacher innovative behavior via teachers' psychological empowerment. This finding is consistent with previous research63 and can be explained by self-determination theory64. Javed et al.30 found that inclusive leadership, as a supportive external context, has been found to meet individual basic psychological needs for competence, autonomy, and relatedness, thereby enhancing their motivation to engage in innovative behavior. In high-power distance contexts such as China, leadership behaviors and attitudes significantly impact subordinate affective states, cognitive processes, and work-related behaviors. Specifically, primary and junior principals who are open, available, and accessible can positively influence teachers' perceptions of their competence, autonomy, and the meaningfulness of their work. As a result, this approach can enhance teacher perceived psychological empowerment, leading to increased autonomy, efficacy, and meaning in their work. This enables them to identify problems promptly and offer innovative suggestions.

The present study further reveals that the school innovation climate serves as a mediator in the association between principal inclusive leadership and teacher innovative behavior, accounting for 30.3% of the overall indirect impact. Although no literature directly proves the link between principal inclusive leadership mediated by school innovation climate and teacher innovative behavior, existing similar research consistently shows that the innovation climate acts as a mediator between various leadership styles and employees' innovative behavior. For instance, Hou (2018) found that the school innovation climate mediates the influence of transformational and transactional leadership on teacher innovative behavior52, while Sagnak (2012) confirmed that empowering leadership impact on teacher innovative behavior is mediated by the school innovation climate65.

Differential mediation effects: innovation climate versus psychological empowerment

The finding of this study, that teachers' psychological empowerment has a greater impact on their innovative behavior than the school innovation climate, aligns perfectly with SCT. SCT emphasizes the reciprocal interaction of personal factors, environmental influences, and behavior, highlighting the importance of cognitive processes and self-efficacy in shaping actions. In this context, teachers' psychological empowerment acts as a strong internal motivator, reflecting their subjective evaluation of the significance, ability, autonomy, and influence of their work34. The school climate of innovation, which is influenced by the inclusive leadership of the principal and fosters a supportive context for innovation, plays a secondary role compared to internal empowerment. This finding emphasizes SCT's proposition that although environmental conditions, such as a positive innovation climate, provide opportunities and reinforcement, it is the internalization of these external cues through personal beliefs and efficacy expectations that activate and sustain innovative behaviors26. Teachers who experience heightened psychological empowerment, demonstrate a stronger emotional attachment to their organization66, and are motivated to reciprocate support from inclusive leaders through citizenship behaviors67.

By reframing the discourse within the framework of SCT, our research highlights the significance of fostering individual belief systems and personal empowerment strategies in conjunction with cultivating supportive organizational environments. This amplifies SCT's explanatory capacity and practical implications for educational leadership and policy.

Practical implications

First, our research has shown that principal inclusive leadership positively impacts teacher innovative behavior. To foster such behavior, educational administration could appoint principals who possess qualities like openness, availability, and accessibility. Moreover, training programs for primary and junior school principals could incorporate relevant theories on inclusive leadership to help them comprehend the significance of embracing diverse educational perspectives from teachers, tolerating mistakes and failures during educational reforms, and actively supporting teachers' exploration of teaching methods.

Second, the study underscores the pivotal role of psychological empowerment in stimulating teacher innovative behavior, a role that is more substantial than the influence of the school innovation climate. This suggests that internal motivational factors, such as teacher self-efficacy, autonomy, and perceived influence, are paramount in driving innovation. Therefore, it is crucial for school leaders to prioritize strategies that amplify teachers' psychological empowerment to cultivate innovation. Principals can actively engage teachers in meaningful organizational decisions, ensuring their perspectives are valued and integrated into school policies and practices. By doing so, leaders can create an environment that recognizes teachers' contributions and instills a sense of ownership and self-determination. Providing targeted support, professional development opportunities, and a culture of respect can significantly bolster teachers' psychological well-being and their belief in their capacity to innovate.

Finally, the present study found that a positive school innovation climate promotes teacher innovative behavior, effectively fostering creative teaching. Hence, it is imperative for school administrators to strategically cultivate a shared perception among teachers regarding the supportive climate for educational and pedagogical innovation within their institutions. This will enable all educators to acknowledge and appreciate the paramount importance placed on innovation by school leaders. Moreover, administrators could offer timely assistance and support to teachers encountering challenges during the implementation of innovative approaches. Furthermore, they could exhibit utmost tolerance towards setbacks or struggles encountered while innovating, while simultaneously recognizing and rewarding those who achieve success through educational innovations.

Limitations

Although this study reveals certain insights, some limitations should also be taken into consideration. First, although various means have been used to avoid subjectivity and social expectation effects, the objectivity of the results will still be questioned to some extent. In the future, behavioral experiment method can be used as the aid to design special situations, select appropriate subjects, and combine questionnaire surveys to obtain more objective research results. Second, sample data are mainly analyzed using cross-sectional data, which cannot explain the causal relationship between variables well. In future studies, longitudinal investigation method of interval time is considered to further verify the causal relationship between variables. In addition, it is important to note that our samples are exclusively from Guangdong Province, Chin, which raises concerns about the generalizability of our findings. While the surveyed city currently represents other similar cities in China, it is crucial to acknowledge potential cultural, institutional, or societal variations when attempting to generalize these results internationally. To address this concern in future studies, expanding the survey scope and increasing the sample size should be considered for the robustness and applicability of research conclusions.

Conclusions

Based on the social cognitive theory, this study investigates the impact of principal inclusive leadership on innovative behavior among primary and junior teachers, as well as the underlying mechanisms. An analysis of 358 questionnaires collected from primary and junior teachers reveals a positive association between principal inclusive leadership and the innovative behavior of primary and junior teachers. The mediating effects of teachers' psychological empowerment and school innovation climate play a crucial role in explaining the relationship between inclusive leadership and teacher innovative behavior. Specifically, it is observed that the mediating effect of teachers' psychological empowerment is stronger than that of school innovation climate in linking principal inclusive leadership with teacher innovative behavior.

Author contributions

B.Y.G wrote the main manuscript text and all figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

For inquiries regarding the data and materials in this paper, please contact the corresponding authors at billbao@126.com.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Messmann G, Mulder RH. Development of a measurement instrument for innovative work behaviour as a dynamic and context-bound construct. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2012;15(1):43–59. doi: 10.1080/13678868.2011.646894. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kristoffersen I. Great expectations: Education and subjective wellbeing. J. Econ. Psychol. 2018;66:64–78. doi: 10.1016/j.joep.2018.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cloete AL. Technology and education: Challenges and opportunities. HTS Teol. Stud. Theol. Stud. 2017 doi: 10.4102/hts.v73i4.4589. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hasanefendic S, Birkholz JM, Horta H, van der Sijde P. Individuals in action: Bringing about innovation in higher education. Eur. J. Higher Educ. 2017;7(2):101–119. doi: 10.1080/21568235.2017.1296367. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lambriex-Schmitz P, van der Klink MR, Beausaert S, Bijker M, Segers M. Towards successful innovations in education: Development and validation of a multi-dimensional Innovative Work Behaviour Instrument. Vocat. Learn. 2020;13(2):313–340. doi: 10.1007/s12186-020-09242-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koeslag-Kreunen MG, van der Klink MR, van den Bossche P, Gijselaers WH. Leadership for team learning: The case of university teacher teams. High Educ. 2018;75(2):191–207. doi: 10.1007/s10734-017-0126-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jung D, Wu A, Chow CW. Towards understanding the direct and indirect effects of CEOs' transformational leadership on firm innovation. Leadersh. Q. 2008;19(5):582–594. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2008.07.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kılınç AÇ, Polatcan M, Savaş G, Er E. How transformational leadership influences teachers’ commitment and innovative practices: Understanding the moderating role of trust in principal. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2022;50:1–20. doi: 10.1177/17411432221082803. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buyukgoze H, Caliskan O, Gümüş S. Linking distributed leadership with collective teacher innovativeness: The mediating roles of job satisfaction and professional collaboration. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2022;50(6):1–22. doi: 10.1177/17411432221130879. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amin S, Mukminin A, Setiawati R, Fitriaty F. Empowering leadership and human resources through stimulating innovative behaviors in higher education. Zb. rad. Ekon. fak. Rij. 2021;39(2):381–399. doi: 10.18045/zbefri.2021.2.381. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gkorezis P. Principal empowering leadership and teacher innovative behavior: A moderated mediation model. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2016;30(6):1030–1044. doi: 10.1108/IJEM-08-2015-0113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zafar S, Raziq MM, Igoe J, Moazzam M, Ozturk I. Inclusive leadership and innovative work behavior: Roles of autonomous motivation and horizontal and vertical trust. Curr. Psychol. 2023 doi: 10.1007/s12144-023-05386-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu G-F, Li M. Impact of inclusive leadership on employees' innovative behavior: A relational silence approach. Front. Psychol. 2023;14:1144791. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1144791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qi L, Liu B, Wei X, Hu Y. Impact of inclusive leadership on employee innovative behavior: Perceived organizational support as a mediator. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(2):e0212091. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0212091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nguyen TV, Nguyen HT, Nong TX, Nguyen TT. Inclusive leadership and creative teaching: The mediating role of knowledge sharing and innovative climate. Creat. Res. J. 2022;34:1–12. doi: 10.1080/10400419.2022.2134543. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asghar M, et al. The influence of inclusive leadership on hospitality employees' green innovative service behavior: A multilevel study. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023;56:347–355. doi: 10.1016/j.jhtm.2023.07.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siyal S, Xin C, Umrani WA, Fatima S, Pal D. How do leaders influence innovation and creativity in employees? The mediating role of intrinsic motivation. Adm. Soc. 2021;53(9):1337–1361. doi: 10.1177/0095399721997427. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carmeli A, Reiter-Palmon R, Ziv E. Inclusive leadership and employee involvement in creative tasks in the workplace: The mediating role of psychological safety. Creat. Res. J. 2010;22(3):250–260. doi: 10.1080/10400419.2010.504654. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Javed B, Naqvi SMMR, Khan AK, Arjoon S, Tayyeb HH. Impact of inclusive leadership on innovative work behavior: The role of psychological safety. J. Manag. Organ. 2019;25(1):117–136. doi: 10.1017/jmo.2017.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mansoor A, Farrukh M, Wu Y, Abdul Wahab S. Does inclusive leadership incite innovative work behavior? HSM. 2021;40(1):93–102. doi: 10.3233/HSM-200972. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li T, Tang N. Inclusive leadership and innovative performance: A multi-level mediation model of psychological safety. Front. Psychol. 2022;13:934831. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.934831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Çetinkaya B, Yeşilada T. Inclusive leadership and employee innovative work behaviours: Testing a psychological empowerment and leader-member exchange moderated-mediation model. J. Psychol. Afr. 2022;32(1):15–20. doi: 10.1080/14330237.2021.2002035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fang Y-C, Chen J-Y, Wang M-J, Chen C-Y. The impact of inclusive leadership on employees' innovative behaviors: The mediation of psychological capital. Front. Psychol. 2019;10:1803. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang H, Chen M, Li X. Moderating multiple mediation model of the impact of inclusive leadership on employee innovative behavior. Front. Psychol. 2021;12:666477. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.666477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jia J, Liu H, Chin T, Hu D. The continuous mediating effects of GHRM on employees’ green passion via transformational leadership and green creativity. Sustainability. 2018;10(9):3237. doi: 10.3390/su10093237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nembhard IM, Edmondson AC. Making it safe: The effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. J. Organ. Behav. 2006;7(27):941–996. doi: 10.1002/job.413. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dorenbosch L, Engen ML, Verhagen M. On-the-job Innovation: The impact of job design and human resource management through production ownership. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2005;14(2):129–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-8691.2005.00333.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Altunoğlu AE, Gürel EB. Effects of leader–member exchange and perceived organizational support on organizational innovation: The case of Denizli Technopark. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015;207:175–181. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.10.170. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Javed B, Abdullah I, Zaffar MA, Haque AU, Rubab U. Inclusive leadership and innovative work behavior: The role of psychological empowerment. J. Manag. Organ. 2019;25(04):554–571. doi: 10.1017/jmo.2018.50. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhutto TA, Farooq R, Talwar S, Awan U, Dhir A. Green inclusive leadership and green creativity in the tourism and hospitality sector: Serial mediation of green psychological climate and work engagement. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021;29(10):1716–1737. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2020.1867864. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amabile TM, Pratt MG. The dynamic componential model of creativity and innovation in organizations: Making progress, making meaning. Res. Organ. Behav. 2016;36(5):157–183. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Choi SB, Tran TBH, Park BI. Inclusive leadership and work engagement: Mediating roles of affective organizational commitment and creativity. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2015;43(6):931–943. doi: 10.2224/sbp.2015.43.6.931. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spreitzer GM. Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Acad. Manag. J. 1995;38(5):1442–1465. doi: 10.2307/256865. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Javed B, Naqvi SMMR, Khan AK, Arjoon S, Tayyeb HH. Impact of inclusive leadership on innovative work behavior: The role of psychological safety. J. Manag. Organ. 2019;25(1):117–136. doi: 10.1017/jmo.2017.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Temple JB, Ylitalo J. Promoting leadership in higher education institution. Tert. Educ. Manag. 2009;15(3):277–289. doi: 10.1080/13583880903073024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Namasivayam K, Guchait P, Lei P. The influence of leader empowering behaviors and employee psychological empowerment on customer satisfaction. Int. J. Contemp. Hospitality Manag. 2014;26(1):69–84. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-11-2012-0218. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Conger JA, Kanungo RN. The empowerment process: Integrating theory and practice. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1988;13(3):471–482. doi: 10.2307/258093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ling H, Xia Y, Zhang J, Tang X. The framework and development of self-concept. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2016;24(2):363–368. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cyfert S, Szumowski W, Dyduch W, Zastempowski M, Chudziński P. The power of moving fast: Responsible leadership, psychological empowerment and workforce agility in energy sector firms. Heliyon. 2022;8(10):e11188. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e11188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Younas A, Wang D, Javed B, Haque AU. Inclusive leadership and voice behavior: The role of psychological empowerment. J. Soc. Psychol. 2023;163(2):174–190. doi: 10.1080/00224545.2022.2026283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khan MM, et al. How servant leadership triggers innovative work behavior: Exploring the sequential mediating role of psychological empowerment and job crafting. EJIM. 2022;25(4):1037–1055. doi: 10.1108/EJIM-09-2020-0367. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ekvall G. Organizational conditions and levels of creativity. Creat. Innov. Manag. 1997;6(4):195–205. doi: 10.1111/1467-8691.00070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meeuwissen SN, Gijselaers WH, van Oorschot TD, Wolfhagen IH, oude Egbrink MG. Enhancing team learning through leader inclusiveness: A one-year ethnographic case study of an interdisciplinary teacher team. Teach. Learn. Med. 2021;33(5):498–508. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2021.1887738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Randel, A. E. et al. Inclusive leadership realizing positive outcomes through belongingness and being valued for uniqueness. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev.7(2) (2017).

- 46.Ye Q, Wang D, Li X. Inclusive leadership and employees’ learning from errors: A moderated mediation model. Aust. J. Manag. 2019;44(3):462–481. doi: 10.1177/0312896218805796. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ye Q, Wang D, Guo W. Inclusive leadership and team innovation: The role of team voice and performance pressure. Eur. Manag. J. 2019;37(4):468–480. doi: 10.1016/j.emj.2019.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carmelia RPR. Inclusive leadership and emplovee involvement increative tasks in the workplace: The mediation role of psychological safety. Creat. Res. J. 2010;22(3):250–260. doi: 10.1080/10400419.2010.504654. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bradley EH. Diversity, inclusive leadership, and health outcomes. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2020;9(7):266–268. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2020.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Johnson B, Stevens JJ. Student achievement and elementary teachers’ perceptions of school climate. Learn. Environ. Res. 2006;9(2):111–122. doi: 10.1007/s10984-006-9007-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haiying XI, Mengting LI, Chaoyang GA. How school creative atmosphere influences innovitive behavior of teachers: A mediated moderating mode. Mod. Educ. Manag. 2019;25(12):81. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hou H. Can principal leadership influence teaching innovation? Educ. Sci. 2018;34(1):26–32. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Amabile TM, Schatzela EA, Monetaa GB, Kramer SJ. Leader behaviors and the work environment for creativity: Perceived leader support. Leadersh. Q. 2006;15(1):5–32. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.10.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yao M, Li Y. Study on mechanism of inclusive leadership and employee innovation behaviors. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy. 2014;31(10):6–9. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Riketta M. Attitudinal organizational commitment and job performance: A meta-analysis. J. Organ. Behavior. 2002;23(3):257–266. doi: 10.1002/job.141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Scott SG, Bruce RA. Determinants of innovative behavior: A path model of individual innovation in the workplace. Acad. Manag. J. 1994;37(3):580–807. doi: 10.2307/256701. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Anderson NR, West MA. Measuring climate for work group innovation: Development and validation of the team climate inventory. J. Organiz. Behav. 1998;19(3):235–258. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(199805)19:3<235::AID-JOB837>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.MacKinnon DP, Fritz MS, Williams J, Lockwood CM. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN. Behav. Res. Methods. 2007;39(3):384–389. doi: 10.3758/BF03193007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fornell C, Larcker DF. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: A comment. J. Mark. Res. 1981;18(1):39–50. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schreiber JB, Nora A, Stage FK, Barlow EA, King J. Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. J. Educ. Res. 2006;99(6):323–338. doi: 10.3200/JOER.99.6.323-338. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.AlMulhim AF, Mohammed SM. The impact of inclusive leadership on innovative work behavior: A mediated moderation model. LODJ. 2023;44(7):907–926. doi: 10.1108/LODJ-05-2023-0224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhong J, Li Y, Luo J. The trickle-down effects of inclusive leadership on employees’ innovative behavior: The joint moderating effects of vicarious learning and organizational inclusion climate. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2021;12(1):154805182110599. doi: 10.1177/15480518211059941. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pieterse AN, Van KD, Schippers M, et al. Transformational and transactional leadership and innovative behavior: The moderating role of psychological empowerment. J. Organ. Behav. 2010;31(4):609–623. doi: 10.1002/job.650. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Deci EL, Olafsen AH, Ryan RM. Self-determination theory in work organizations: The state of a science. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2017;4(1):19–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032516-113108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sagnak M. The empowering leadership and teachers’ innovative behavior: The mediating role of innovation climate. Afr. J. Bus. Manage. 2012;6(4):1635. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Prati G, Zani B. The relationship between psychology empowerment and organizational identification. J. Commun. Psychol. 2013;41(7):851–866. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21578. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bose S, Patnaik B, Mohanty S. The mediating role of psychological empowerment in the relationship between transformational leadership and organizational identification of employees. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2021;57(4):490–510. doi: 10.1177/0021886320920951. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

For inquiries regarding the data and materials in this paper, please contact the corresponding authors at billbao@126.com.