Identifying particular advances in public health is difficult because, in the final analysis, success can be judged only by improvement in the health of a population. Progress is rarely, if ever, a matter of developing a technical intervention and applying it. Population health is determined by a complex mixture of genetic, environmental, and social factors, as well as individual behaviour. Achieving progress not only relies on altering a complex situation but is often something that can be judged only over a period of years (or decades) rather than months. Clearer understanding of the determinants of health and ill health, better control of hazards to health, and earlier detection or improved treatment of established disease are the building blocks of gains in public health. In keeping with the broadening scope of public health practice, the skill base of the workforce is developing beyond medicine, particularly in the applied social sciences.

Methods

This paper was based on personal experience in public health, the contemporary public health literature, and the comments of respected colleagues. The literature search had been undertaken during the preparation of a recent book.1

Life course epidemiology

The prime targets for preventive action in recent decades have been the chronic diseases that are the major causes of mortality in developed countries. The approach adopted has largely been based on the understanding of risk factors for these diseases and has focused on changing the behaviour of adults, particularly in the areas of smoking, exercise, and nutrition. A major challenge to this approach has come from the work of David Barker and colleagues who have postulated that the development of chronic disease in adulthood is programmed before or shortly after birth.2 As supporting evidence has emerged, the initially sceptical response to this thesis has given way to an acceptance of the importance of fetal and early life influences. Interest in long term cohort studies has been reawakened in the public health research community, resulting in the disinterring of long neglected maternal and child health records and in the recognition of the importance of contemporary cohort studies.

Recent advances

Large sample size and the relatively high response rate have made the annual health survey for England an important development in public health intelligence

The European Commission is establishing a Public Health Observatory for disease surveillance across the European Union

In England, the National Screening Committee will provide advice on possible screening programmes

The recent European Union decision to support a ban on tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship is a major breakthrough

Development of a research and development programme for the NHS is the foundation of a strategy to increase efficiency and effectiveness at a time of constrained resources

Emphasis on the quality of clinical services and clinical governance is growing

The results emerging from this epidemiological endeavour may well have profound implications for public health policy. The current concentration on reducing risk factors in adults is likely to be tempered by a growing emphasis on the antenatal and early life period.3 This life course approach will not be without its difficulties. Concern has already been expressed that promoting lifestyle change among adults can turn into “nannying.” At a time when women are increasingly seeking to have a greater degree of control of the health care they receive during pregnancy, medical concentration on antenatal interventions of various kinds aimed at the long term prevention of adult chronic disease is now possible. However, it is also possible that attention will be diverted from important problems, such as smoking and obesity in adults, where much remains to be done.

Information

Information on the incidence and prevalence of disease in the community is crucial to the practice of public health professionals. The importance of quantitative study of population health was recognised by William Petty and John Graunt in the 17th century,4 and, if anything, this importance is increasing as we grapple with the major non-communicable diseases such as coronary heart disease and stroke. The backbone of public health information is the registration of life events, particularly births and deaths, and these data continue to underpin much of our contemporary understanding of population health. However, we have a strong tradition of population surveys, of which the most important recent addition (1991) is the annual health survey for England. This survey collects both questionnaire and clinical data from those over 2 years of age in a random sample of households in England. The large size of the sample (11 766 households in 1996) and the relatively high response rate (79% in 1996), together with expert analysis, have made this survey an outstanding innovation in public health intelligence.5 Despite the coverage of important health problems such as the prevalence and control of hypertension and diabetes, as well as the collection of valuable data on the use of health services, the health survey for England remains an under utilised resource.

The European dimension to public health activity is being increasingly recognised as one of the major future influences on public health policy and practice.6 Welcome signs exist that the issue of the surveillance of non-communicable disease is being taken seriously within the European Union. The Commission has identified the sum of 13.8 million ECU to establish a Public Health Observatory, which will undertake disease surveillance across the European Union. This has enormous potential for supporting the growing level of European involvement in public health issues.

Screening

The origins of population screening have been attributed to events at the beginning of this century when, in the aftermath of the Boer War, steps were taken to improve the health of British children and therefore, in due course, of recruits to the British army. It was not until the 1960s that a satisfactory framework was developed for the consideration of the ever growing number of propositions for screening tests and programmes. The Wilson and Junger criteria, which cover key requirements—for example, that the condition should be an important health problem with an accepted treatment—have stood the test of time, although it has been suggested that they need to be supplemented to deal with issues of resource use and opportunity cost.7,8 The practical difficulties of applying the criteria, however, have highlighted the necessity of developing a consistent and scientifically based approach to decision making in relation to screening programmes. The formation in England of a National Screening Committee to provide advice across the whole gamut of possible screening programmes is an important advance. One of the first substantial products of that initiative has been a recommendation that screening for prostatic carcinoma should not be introduced.9 Recent revelations in England of serious deficiencies in the local provision of screening for both breast and cervical cancer have re-emphasised the fact that the quality of these public health activities cannot be taken for granted and must remain a key concern of public health doctors.

Tobacco control

The decision of the European Union Council of Ministers in December 1997 to support a proposed directive banning tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship has been acclaimed as a major and long awaited breakthrough. Smoking remains the single greatest cause of illness and death in the developed world, and tobacco control should therefore be at the forefront of public heath endeavour. In recent years, not only has progress in reducing tobacco consumption in the developed world been disappointingly slow but the growth of consumption in the developing world has been alarming.

It was as long ago as 1992 that an authoritative report from the Department of Health concluded that advertising has the effect of increasing consumption and that the introduction of advertising bans produced reductions in smoking.10 The previous lack of concerted effort at intergovernmental level in western Europe on the important issue of tobacco advertising has been disheartening for many health professionals and has been an obstacle to those activists seeking to build concerted action.

While it is important to develop a comprehensive international strategy for tobacco control, the next big battleground for anti-tobacco campaigners is likely to be in the area of non-smokers’ rights. The publication in late 1997 of conclusive research evidence highlighting the powerful causal relation between environmental tobacco smoke and ischaemic heart disease and lung cancer indicates that the further restriction of smoking in indoor environments should be a major public health priority.11,12 The achievement of the right of individuals to work and enjoy leisure without having to breath tobacco smoke is likely to be the most important advance in coming years.

Management of clinical innovation

An important strand of public health activity has always been involvement in the organisation and planning of personal health services. In his famous monograph, Effectiveness and Efficiency, Archie Cochrane recounts being told by a very contented crematorium worker that he was fascinated by the way in which so much went in and so little came out.13 Cochrane considered advising him to get a job in the NHS, where this was even more true. The task of getting more improvement in health out of the health service at a time of apparently ever more constrained resources has, however, been the subject of a well constructed and impressive strategy aimed at producing just the increase in effectiveness that Cochrane desired. The development of a research and development programme for the NHS has been the foundation of this strategy. As as a result, increased priority and substantially increased resources have been devoted to health services research in the United Kingdom. This effort has engaged not just public health practitioners but many in the wider clinical community. The “products” of this research effort are beginning to appear and have the potential to change practice in important ways. The growing field of health technology assessment has become recognised as an important skill area and has, for example, helped marshal the evidence base to inform decisions on screening. The days of new drugs, techniques, or equipment being sprung on an unsuspecting and ill prepared NHS are now numbered, if not yet completely over.

Three important elements have underpinned the development of the move towards more effective health care in the United Kingdom. Firstly, the growth of institutes or centres with the academic skills to review systematically research evidence in order to increase its accessibility and relevance to those making clinical and managerial decisions. These have often been based on academic departments of epidemiology and public health and undertake commissioned work for the NHS. The second element is the various “effectiveness products” that flow from the different centres and constitute the major source of information to the NHS on clinical innovation. These products are usually based on careful synthesis of research evidence. Typically, they cover not only clinical effectiveness but cost effectiveness, and inform directly public health practitioners in health authorities and boards faced with difficult and often politically sensitive commissioning decisions. The development of critical appraisal skills among those considering research evidence has been the third important advance in this area. While elements of these skills have always been included in the training of public health professionals, skill reinforcement and diffusion into the wider clinical community has been a central element of developmental approaches in this area. The continuing growth in the emphasis on quality of clinical services, along with the newly developing concept of clinical governance, will ensure that public health practitioners continue to have an engagement with personal health services as well as the broader social and environmental agenda.14

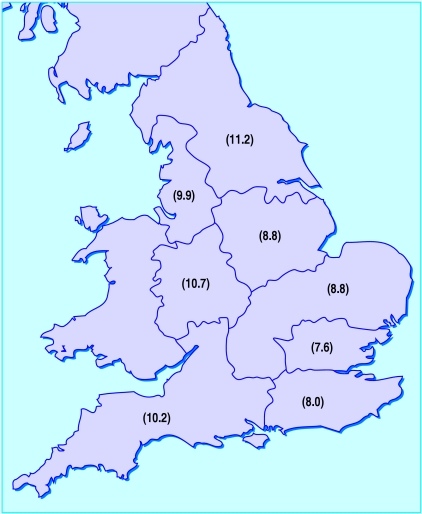

Figure.

Untreated high blood pressure in adults, England, 1996: prevalence (%) by region

Editorials byAlderslade, PalmerEducation and debate pp 587, 592, 596

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Conflict of interest: None.

References

- 1.Scally G, editor. Progress in public health. London: Royal Society of Medicine Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barker DJP. Mothers, babies, and disease in later life. London: BMJ Publishing Group; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuh D, Ben-Shlomo Y. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prescott-Clarke P, Primatesta P. Health survey for England. London: Stationery Office; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKee M, Mossialos E. Public health and European integration. In: Scally G, editor. Progress in public health. London: Royal Society of Medicine Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graunt J. Natural and political observations mentioned in a following index, and made upon the bills of mortality. London: Roycroft; 1662. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson JMQ, Junger G. Principles and practice of screening for disease. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gray JM. Screening: challenge to rational thought and action. In: Scally G, editor. Progress in public health. London: Royal Society of Medicine Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 9.NHS Executive. Population screening for prostate cancer. Leeds: NHS Executive; 1997. (EL(97)12.) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smee C. Effect of tobacco advertising on tobacco consumption. London: Department of Health; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Law MR, Morris JK, Wald NJ. Environmental tobacco smoke exposure and ischaemic heart disease: an evaluation of the evidence. BMJ. 1997;315:973–980. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7114.973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hackshaw AK, Law MR, Wald NJ. The accumulated evidence on lung cancer and environmental tobacco smoke. BMJ. 1997;315:980–988. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7114.980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cochrane A. Effectiveness and efficiency. London: Nuffield Provincial Hospitals Trust; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donaldson L. Clinical governance: a statutory duty for quality improvement. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52:73–74. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.2.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]