Abstract

Many phenomena in nature consist of multiple elementary processes. If we can predict all the rate constants of respective processes quantitatively, we can comprehensively predict and understand various phenomena. Here, we report that it is possible to quantitatively predict all related rate constants and quantum yields without conducting experiments, using multiple-resonance thermally activated delayed fluorescence (MR–TADF) as an example. MR–TADFs are excellent emitters because of its narrow emission, high luminescence efficiency, and chemical stability, but they have one drawback: slow reverse intersystem crossing (RISC), leading to efficiency roll-off and reduced device lifetime. Here, we show a quantum chemical calculation method for quantitatively obtaining all the rate constants and quantum yields. This study reveals a strategy to improve RISC without compromising other important factors: radiative decay rate constants, photoluminescence quantum yields, and emission linewidths. Our method can be applied in a wide range of research fields, providing comprehensive understanding of the mechanism including the time evolution of excitons.

Subject terms: Materials for devices, Materials chemistry

The quantitative prediction of rate constants and quantum yields is crucial to understand various phenomena and their mechanisms in nature. Here, the authors apply quantum chemical calculation to reproduce experimental data of multiple-resonance thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitters.

Introduction

Multiple-resonance thermally activated delayed fluorescence (MR–TADF) has attracted substantial attention in organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) research because it can realise high external quantum efficiency and narrow electroluminescence spectra with high colour purity1–3. Hatakeyama et al. reported the first MR–TADF molecule (DABNA-1) in 20161 by incorporating B and N atoms into a carbon-based molecular structure. In DABNA-1, the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) distributions are spatially separated on different atoms, resulting in a relatively small energy difference ΔE(T1 → S1) of 0.15–0.2 eV between the lowest excited singlet state (S1) and lowest triplet state (T1). The ΔE(T1 → S1) value is sufficiently small to cause TADF but rather large; the rate constant (kRISC) for reverse intersystem crossing (RISC) is small (9.9 × 103 s−1)1. Since the report of DABNA-1, a number of MR–TADF molecules have been developed; however, most of them exhibit kRISC values on the order of 104–105 s−1 1–7. The slow RISC is considered to cause triplet-related annihilation8, resulting in efficiency roll-off in OLEDs. The slow RISC also reduces the device lifetime of OLEDs. Thus, there is an urgent need to develop MR–TADF emitters with large kRISC to solve these problems without sacrificing the rate constant of fluorescence from S1 to the ground state (S0) (kF(S1 → S0) or simply kF), the photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), and the colour purity. Recently, Yasuda’s group developed MR–TADF materials with kRISC of 108 s−1 by utilising the heavy atom effect of selenium (Se) atoms9. However, the kF (~105 s−1) was more than two orders of magnitude smaller than the oxygen (O) type analogue. Yang’s group developed Se-containing MR–TADF materials. The kRISC of 106 s−1 and the kF of ~107 s−1 are more well-balanced10. However, the efficiency roll-off problem has not been well solved; simultaneous realisation of kRISC > 107 s−1 and kF > 107 s−1 is desirable.

Among all the reported MR–TADF molecules, the RISC mechanisms have been analysed in detail for DABNA-1, DABNA-2, and ν-DABNA. Quantum chemical calculations11–14 and time-resolved photoluminescence (PL) measurements15 indicate that the total RISC process of the three materials occurs via higher triplet states (Tn, n ≥ 2), typically T2 (Kim et al.13 carried out an analysis including from T1 to T3), although only the direct T1 → S1 RISC has initially been considered. When RISC occurs via T2 (T1 → T2 → S1), kRISC increases with decreasing T2 → S1 (especially when S1 is higher in energy than T2) and T1 → T2 energy gaps (denoted as ΔE(T2 → S1) and ΔE(T1 → T2), respectively), and increasing S1–T2 spin–orbit coupling (SOC(S1–T2)). A small |ΔE(T2 → S1)| and large SOC(S1–T2) accelerate the T2 → S1 transition, and a small ΔE(T1 → T2) accelerates the T1 → T2 internal up-conversion.

We have reported three methods to enhance RISC: (1) intervening in a locally excited state between charge transfer type singlet (1CT) and triplet (3CT) states16, (2) using the fluctuational effect for 3CT → 1CT RISC17, although it seemingly violates the El-Sayed rule18, and (3) using the heavy atom effect19–21. Regarding the third method, a practical strategy for increasing kRISC is assumed to incorporate third-, fourth-, or lower-row elements to enhance SOC by their heavy atom effect. Various O-, sulfur- (S-), and Se-containing molecules have been developed for conventional TADF emitters composed of donor and acceptor segments10,22–30; kRISC is enhanced by 2–20 times via O → S substitution10,22,23,25, and up to 50 times via O → Se substitution10. The carbonyl (C = O) group can also enhance SOC because of the n–π* orbital; as evidenced by benzophenone, a representative carbonyl compound, having a large rate constant (kISC) for intersystem crossing (ISC) of ~1011 s−1 31. The C = O group is a promising alternative to S and Se for enhancing SOC with only C, H, and O atoms5,6,32–35. A C = O-containing MR–TADF emitter developed by the Zysman–Colman group (DDiKTa6) exhibited a larger kRISC of 6.3 × 105 s−1 than that of ν-DABNA (kRISC = 2.0 × 105 s−1), although DDiKTa had a larger ΔE(T1 → S1) of 0.16 eV than ν-DABNA (0.07 eV), suggesting that the C = O groups in DDiKTa accelerated RISC.

Thus, understanding the excited-state decay mechanisms of MR-TADF emitters is important to design novel materials with enhanced TADF properties. To understand the decay mechanisms of a TADF emitter, it is common to determine the rate constants of electronic transitions from the experimental PLQY and transient photoluminescence decay curve fitted by a linear combination of exponential decay functions. A comprehensive understanding of the emission mechanism is achieved only when the rate constants for all elementary electronic transitions have been determined. However, it is difficult to determine all rate constants when the number of the rate constants is larger than that of experimentally determined fitting parameters (specifically, when singlet and triplet states energetically higher than S1 and T1 are involved). Our theoretical method allows us to quantitatively predict rate constants and quantum yields, including those inaccessible from experiments. Our method also clarifies the quantitative dynamics (time evolutions) of excitons, providing a comprehensive understanding of the TADF mechanism. Therefore, our method proposed in this study offers a guideline for designing TADF emitters with enhanced properties.

Here, we report a quantitative theoretical investigation of the emission mechanism of MR–TADF molecules, focusing on the acceleration of RISC. As with various phenomena, the emission here consists of multiple elementary processes. The quantitative description of the rate constants not only for RISC but also for all relevant elementary processes is of primary importance because such a description enables a comprehensive understanding and prediction of the emission mechanism. We investigate the RISC mechanism of previously synthesised MR–TADF emitters (BNOO, BNSS, and BNSeSe) (Fig. 1), reported by Yang’s group10. Here, we define a total ISC/RISC rate constant (ktoISC/ktoRISC) as the entire ISC/RISC process involving both the S1 → T1/T1 → S1 and S1 → T2 ↔ T1/T1 ↔ T2 → S1 transitions, which correspond to the experimentally obtained values (see the “Methods” section). Electronic states higher than S1 and T2 are not required to be considered because they are energetically well separated. All the calculated ktoISC (8.6 × 107, 2.0 × 108, and 1.0 × 109 s−1 for BNOO, BNSS, and BNSeSe, respectively) and ktoRISC (9.2 × 103, 2.5 × 105, and 1.5 × 106 s−1, respectively) in this study well-reproduce the experimental ktoISC (7.5 × 107, 1.5 × 108, and 4.9 × 108 s−1, respectively) and ktoRISC (4.3 × 104, 1.9 × 105, and 2.0 × 106 s−1, respectively). The calculations also clarify how the S and Se atoms accelerate RISC. All the calculated values of ΔE(T1 → S1), kF(S1 → S0), and PLQY (Φ) as well as the prompt and TADF contributions, also reasonably reproduce the experimental results (Table 1); indicating the validity of our calculation method. The calculated ktoRISC of BNOO slightly deviates from the experimental value because of the overestimation of ΔE(T1 → S1) (when we use the experimental ΔE(T1 → S1) of 0.15 eV instead of the calculated value of 0.21 eV, ktoRISC is calculated to be 8.2 × 104 s−1, close to the experimental value of 4.3 × 104 s−1).

Fig. 1. Molecular structures and HOMO−1, HOMO, and LUMO distributions.

a BNOO, b BNSS, c BNSeSe, d BNTeTe, e BNPoPo, and f BNCOCO. HOMO and LUMO are the highest occupied molecular orbital and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital, respectively.

Table 1.

Calculated energies, energy gaps, rate constants, quantum yields, spin-orbit couplings, and emission linewidths of BNOO, BNSS, BNSeSe, BNTeTe, BNPoPo, and BNCOCO

| BNOO | BNSS | BNSeSe | BNTeTe | BNPoPo | BNCOCO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E(S1) (eV) |

2.51 (2.54) |

2.44 (2.55) |

2.51 (2.58) |

2.52 | 2.41 | 2.55 |

| E(T1) (eV) |

2.30 (2.39) |

2.30 (2.42) |

2.37 (2.44) |

2.38 | 2.26 | 2.41 |

| ΔE(T1 → S1) (eV) |

0.21 (0.15) |

0.14 (0.13) |

0.14 (0.14) |

0.14 | 0.14 | 0.14 |

| ΔE(T2 → S1) (eV) | 0.08 | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.06 | −0.12 | 0.03 |

| ΔE(T1 → T2) (eV) | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.26 | 0.11 |

| ktoISC (s−1) |

8.6 × 107 (7.5 × 107) |

2.0 × 108 (1.5 × 108) |

1.0 × 109 (0.5 × 109) |

6.6 × 109 | 4.3 × 1010 | 6.5 × 108 |

| ktoRISC(T1) (s−1) | 8.4 | 2.0 × 103 | 1.2 × 105 | 3.0 × 106 | 4.9 × 107 | 39 |

| ktoRISC(T2) (s−1) | 9.2 × 103 | 2.5 × 105 | 1.4 × 106 | 7.2 × 106 | 6.9 × 106 | 9.9 × 105 |

| ktoRISC (s−1) |

9.2 × 103 (4.3 × 104) |

2.5 × 105 (1.9 × 105) |

1.5 × 106 (2.0 × 106) |

1.0 × 107 | 5.6 × 107 | 9.9 × 105 |

| ktoRISC′ (s−1) | 9.3 × 103 | 2.5 × 105 | 1.5 × 106 | 1.0 × 107 | n. d. | 9.9 × 105 |

| kF(S1 → S0) (s−1) |

2.7 × 108 (8.2 × 107) |

2.2 × 108 (4.5 × 107) |

2.5 × 108 (2.6 × 107) |

2.4 × 108 | 1.5 × 108 | 4.7 × 108 |

| kNR(S1 → S0) (s−1) | 2.0 × 107 | 2.1 × 107 | 1.8 × 107 | 1.8 × 107 | 2.0 × 107 | 1.2 × 107 |

| kISC(S1 → T1) (s−1) | 7.9 × 104 | 1.6 × 106 | 8.7 × 107 | 1.9 × 109 | 3.7 × 1010 | 2.6 × 104 |

| kISC(S1 → T2) (s−1) | 8.6 × 107 | 2.0 × 108 | 9.4 × 108 | 4.7 × 109 | 5.3 × 109 | 6.5 × 108 |

| kIC(T2 → T1) (s−1) | 9.9 × 1012 | 2.4 × 1012 | 2.2 × 1012 | 1.4 × 1012 | 4.2 × 1011 | 4.7 × 1012 |

| kRISC(T2 → S1) (s−1) | 1.3 × 106 | 2.6 × 108 | 1.8 × 109 | 1.5 × 1010 | 1.8 × 1011 | 7.8 × 107 |

| kNR(T2 → S0) (s−1) | 0.68 | 2.7 | 1.9 × 102 | 2.1 × 103 | 2.9 × 104 | 0.66 |

| kPhos(T2 → S0) (s−1) | 92 | 1.5 × 103 | 9.6 × 103 | 5.7 × 104 | 3.4 × 105 | 3.4 × 103 |

| kIC(T1 → T2) (s−1) | 7.1 × 1010 | 2.4 × 109 | 1.7 × 109 | 6.5 × 108 | 1.6 × 107 | 6.1 × 1010 |

| kRISC(T1 → S1) (s−1) | 8.5 | 2.0 × 103 | 1.2 × 105 | 3.0 × 106 | 4.9 × 107 | 40 |

| kNR(T1 → S0) (s−1) | 3.8 | 14 | 1.4 × 102 | 1.1 × 103 | 3.5 × 104 | 0.44 |

| kPhos(T1 → S0) (s−1) | 1.6 | 10 | 4.9 × 102 | 6.6 × 103 | 9.7 × 104 | 0.25 |

| kPrompt (s−1) |

3.7 × 108 (1.9 × 108) |

4.4 × 108 (2.0 × 108) |

1.3 × 109 (0.5 × 109) |

6.8 × 109 | 4.1 × 1010 | 1.1 × 109 |

| kDelayed (s−1) |

7.1 × 103 (26 × 103) |

1.4 × 105 (0.5 × 105) |

3.1 × 105 (1.0 × 105) |

3.9 × 105 | 3.5 × 105 | 4.2 × 105 |

| kTADF = ktoR(S1) (s−1) | 6.6 × 103 | 1.3 × 105 | 2.9 × 105 | 3.6 × 105 | 1.9 × 105 | 4.1 × 105 |

| ktoR(T1) (s−1) | 1.6 | 10 | 4.9 × 102 | 6.6 × 103 | 9.7 × 104 | 0.25 |

| ktoR(T2) (s−1) | 0.65 | 1.4 | 7.1 | 28 | 13 | 43 |

| ktoR (s−1) | 6.6 × 103 | 1.3 × 105 | 2.9 × 105 | 3.7 × 105 | 2.9 × 105 | 4.1 × 105 |

| Φ |

0.93 (0.71) |

0.91 (0.91) |

0.93 (1.0) |

0.93 | 0.83 | 0.97 |

| ΦNR(S1) | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.03 |

| ΦNR(T1) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.00 |

| ΦNR(T2) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| ΦPrompt |

0.71 (0.43) |

0.50 (0.23) |

0.19 (0.05) |

0.04 | 0.003 | 0.41 |

| ΦTADF |

0.22 (0.28) |

0.41 (0.68) |

0.74 (0.95) |

0.87 | 0.55 | 0.56 |

| ΦPhos(T1) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.28 | 0.00 |

| ΦPhos(T2) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| S0-T1 SOC (cm−1) | 2.12 | 4.07 | 13.5 | 37.7 | 202 | 0.76 |

| S0-T2 SOC (cm−1) | 0.96 | 1.92 | 16.9 | 56.5 | 204 | 0.97 |

| S1-T1 SOC (cm−1) | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.84 | 3.92 | 17.7 | 0.01 |

| S1-T2 SOC (cm−1) | 0.55 | 1.17 | 3.32 | 10.6 | 59.1 | 1.01 |

| FWHM (nm) |

50–53 (51) |

50–53 (53) |

47–50 (47) |

47–50 | 52–56 | 43–46 |

Some values are time-dependent; the values here are those at the equilibrium states, which correspond to the experimentally observable ones. The values in the parentheses are experimental data reported by Hu et al.10. kTADF for BNOO/BNSS/BNSeSe/BNTeTe/BNPoPo/BNCOCO is defined in the time domain longer than 100/100/10/ 10/1/10 ns. ktoRISC for BNOO/BNSS/BNSeSe/BNTeTe/BNPoPo/BNCOCO is defined in the time domain longer than 1/10/10/10/1/10 ns (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3). ktoRISC′ is the total RISC rate constant calculated by our previously proposed method20. n.d. means not determined. ktoR(S1), ktoR(T1), and ktoR(T2) are the contributions from S1 → S0 fluorescence, T1 → S0 phosphorescence, and T2 → S0 phosphorescence to ktoR, respectively: ktoR = ktoR(S1) + ktoR(T1) + ktoR(T2); ktoR(S1) = kF(S1 → S0) × [S1]/([S1] + [T1] + [T2]); ktoR(T1) = kPhos(T1 → S0) × [T1]/([S1] + [T1] +[T2]); ktoR(T2) = kPhos(T2 → S0) × [T2]/([S1] + [T1] + [T2]). ktoRISC(T1) and ktoRISC(T2) are the contributions from T1 → S1 and T2 → S1 ISCs to ktoRISC, respectively. ktoRISC = ktoRISC(T1) + ktoRISC(T2); ktoRISC(T1) = kRISC(T1 → S1) × [T1]/([T1] + [T2]); ktoRISC(T2) = kRISC(T2 → S1) × [T2]/([T1] + [T2]).

Next, we discuss the impacts of further heavy atom effects on RISC and the possibility of further increasing ktoRISC by using tellurium (Te), polonium (Po), and C = O substitutions (Fig. 1). Our calculations predict that a Te-containing emitter (BNTeTe) exhibits one order of magnitude larger ktoRISC of 107 s−1 than BNSeSe (ktoRISC ~ 106 s−1). Although Po is highly radioactive, we theoretically investigate a Po-containing emitter (BNPoPo) to understand the heavy atom effect. Our calculations indicate that BNPoPo exhibits both TADF and phosphorescence. We calculate the ktoRISC of a C = O-containing molecule (BNCOCO) to be 106 s−1. Compared with Se, the C = O group has a smaller SOC-enhancement ability but provides a sufficient T1 → T2 internal up-conversion, resulting in ktoRISC that is comparable to that of BNSeSe. The calculated kF(S1 → S0)s are the same order of magnitude (108 s−1) for all the compounds investigated in this study. Their calculated PLQYs remain high, indicating that we can enhance RISC without sacrificing radiative decays nor PLQYs, which is otherwise a trade-off in TADF emitters. Finally, we theoretically predict the linewidths (full width at half maximum (FWHM)) of the PL spectra for these molecules. The calculated FWHM values are almost identical for BNOO, BNSS, and BNSeSe; agreeing well with the experimental values. Those for designed BNTeTe, BNPoPo, and BNCOCO are comparable to those for BNOO, BNSS, and BNSeSe; indicating that the acceleration of kRISC in this study also does not sacrifice the FWHM values.

Results

Computational results for BNOO, BNSS, and BNSeSe

Our theoretical analysis is based on rate constant calculations. Details of the method of calculating the rate constants for fluorescence from S1 to S0 (kF(S1 → S0)), Tn → S0 phosphorescence (kPhos(Tn → S0)), S1 → S0 nonradiative decay (kNR(S1 → S0)), Tn → S0 nonradiative decay (kNR(Tn → S0)), Tm → Tn internal conversion (kIC(Tm → Tn)), S1 → Tn ISC (kISC(S1 → Tn)), and Tn → S1 RISC (kRISC(Tn → S1)) (m, n = 1, 2, m ≠ n) are described in the “Methods” section. As is well known, conventional time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) methods substantially overestimate ΔE(T1 → S1) of MR–TADF emitters, which can be solved by calculations including double-excitation configurations36. Several wave-function-based methods (including the second-order algebraic-diagrammatic construction ADC(2) and the spin-component-scaling second-order approximate coupled-cluster (SCS–CC2)) give more reliable ΔE(T1 → S1) than TD–DFT methods36. Recently, it has become common to use different theoretical methods for different molecular properties13,37,38. For example, Lin et al. calculated excitation energies with the TD-B3LYP/6-31G(d) method, and then, the T1 energy was corrected using ΔE(T1 → S1) obtained from the SCS–CC2/def2-TZVP calculation38. Tamm–Dancoff approximation (TDA)–DFT methods with double hybrid density functionals such as TDA–B2-PLYP are emerging alternative approaches for considering double-excitation configurations39. TDA–DFT methods have the advantage of low computational cost compared with ADC(2) and SCS–CC2. Here, we compared the ΔE(T1 → S1) values calculated with the three methods as well as that by the conventional TD–DFT (B3LYP) method (blue texts in Supplementary Tables 13 and 14). Supplementary Table 13 also shows the experimental values. The TDA–B2-PLYP method provided the ΔE(T1 → S1) values closest to the experimental results for BNSS and BNSeSe. Therefore, we used the TDA–B2-PLYP method (TDA–DFT with the B2-PLYP double-hybrid functional and def2-TZVP basis set) for calculating ΔE(T1 → S1), which we combined with the energy levels of S1 and T2 calculated by the TD–DFT with the B3LYP functional and 6-31 G(d)+SDD basis set (TD–B3LYP method). All the other calculations (SOCs, vibronic coupling constants, transition dipole moments, and permanent dipole moments) were carried out by the TD–B3LYP method (see Methods section and Supplementary Method 2 for the details). We performed the TDA–B2-PLYP calculations with the ORCA 5.0.3 program package (FACCTs, Cologne, Germany)40–42 and the ADC(2) and SCS–CC2 calculations with the TURBOMOLE program package43. Table 1 shows the calculated and experimental data. Figure 2a–f shows the calculated excited-state energy diagrams, energy gaps, SOCs, and rate constants for BNOO, BNSS, and BNSeSe. Figure 2g–l shows the time evolutions of respective rate constants. The calculated ΔE(T1 → S1) for BNSS and BNSeSe agree with the experimental values (calculated and experimental ΔE(T1 → S1) are 0.14 and 0.13 eV, respectively, for BNSS and they are both 0.14 eV for BNSeSe), although we found a slight deviation by 0.06 eV for BNOO (the ΔE(T2 → S1) and ΔE(T2 → T1) values have not been determined experimentally). We can reasonably neglect the contributions of Sn (n ≥ 2) and Tm (m ≥ 3) as described above.

Fig. 2. Excited-state decay mechanism.

a–c Calculated excited-state energy diagram, energy differences (eV), and spin–orbit couplings (cm−1) and d–f rate constants (s−1) for BNOO, BNSS, and BNSeSe. g–i Calculated ktoR, ktoR(S1), ktoR(T1), and ktoR(T2) for BNOO, BNSS, and BNSeSe. j–l Calculated ktoRISC, ktoRISC(T1), and ktoRISC(T2) for BNOO, BNSS, and BNSeSe. In d–f, the solid orange arrows depict the dominant S1 → T1 pathway, the solid green arrows depict the dominant T1 → S1 pathway, the solid black arrows depict the minor S1 → T1 and T1 → S1 pathways, the solid blue arrows depict the S1 → S0 fluorescence, the solid red arrows depict the T1 → S0 phosphorescence, and the dashed arrows depict S1 → S0 and T1 → S0 nonradiative decays. In g–i, the solid grey curves depict ktoR, the blue curves depict ktoR(S1), the solid red curves depict ktoR(T1), and the dashed red curves depict ktoR(T2). In j–l, the solid grey curves depict ktoRISC, the solid red curves depict ktoRISC(T1), and the dashed red curves depict ktoRISC(T2). Source data for figure g-l are provided as a Source Data file.

For BNOO, BNSS, and BNSeSe, S1 and T2 are energetically close (|ΔE(T2 → S1)| <0.1 eV), and the S1–T2 SOCs are stronger than the S1–T1 SOCs (Table 1 and Fig. 2a–c). As a result, kISC(S1 → T2) is larger than kISC(S1 → T1) by 1000 times for BNOO, 100 times for BNSS, and 10 times for BNSeSe. S1 and T1 of BNOO, BNSS, and BNSeSe are predominantly described as the HOMO–LUMO transitions, whilst their T2s are predominantly described as the HOMO−1-LUMO transitions (Fig. 1). The S1–T2 SOCs are more substantial than the S1–T1 SOCs because S1–T2 transitions are between different molecular orbital (MO) characters, whilst S1–T1 transitions are between similar MOs.

The larger S1–T2 SOCs compared with S1–T1 SOCs, as well as closer energy levels of S1–T2 compared with those of S1–T1, suggest faster transitions for T2-mediated ISC and RISC compared with those for direct S1–T1 ISC and RISC. The calculated ktoISC agrees well with the experimental values for BNOO, BNSS, and BNSeSe (Table 1). Regarding BNOO and BNSS, the stepwise S1 → T2 → T1 transition contributed to the entire ISC process and the direct S1 → T1 ISC was negligible (ktoISC ≈ kISC(S1 → T2) ≫ kISC(S1 → T1); kIC(T2 → T1) is very large). Regarding BNSeSe, although the contribution from the direct S1 → T1 ISC was not negligible, the stepwise S1 → T2 → T1 transition was still dominant (ktoISC ≈ kISC(S1 → T2) and kISC(S1 → T1) was one order smaller than kISC(S1 → T2)). ktoISC increased with increasing atomic number for the chalcogen atoms (8.6 × 107 s−1 < 2.0 × 108 s−1 < 1.0 × 109 s−1 for BNOO, BNSS, and BNSeSe, respectively), indicating that the O → S → Se substitution enhanced the S1–T2 SOC and accelerated the S1 → T2 ISC.

Next, we investigated RISC for BNOO, BNSS, and BNSeSe. Table 1 shows the calculated and experimental ktoRISC as well as Φ, ΦPrompt, ΦTADF, ΦPhos(T1), ΦPhos(T2), and kTADF for BNOO, BNSS, and BNSeSe. Here, ΦPrompt, ΦTADF, ΦPhos(T1), and ΦPhos(T2) are the PLQYs of the prompt fluorescence, TADF, phosphorescence from T1, and phosphorescence from T2, respectively. kTADF is the rate constant of TADF (delayed fluorescence). Because ΦPhos(T1) ≈ 0 for the three compounds, we attributed the delayed luminescence to TADF (ΦPhos(T2) ≈ 0 for all six compounds). Most importantly, the calculated ktoRISC increased with increasing atomic number for the chalcogen atoms, and the ktoRISC quantitatively agrees with the experimental values, which confirms the validity of our method of predicting ktoRISC. The calculations here enabled us to separate the contributions of direct RISC (T1 → S1) and RISC via T2 (T1 → T2 → S1). We denote them as ktoRISC(T1) (=kRISC(T1 → S1)) and ktoRISC(T2), respectively. Regarding BNOO, BNSS, and BNSeSe, the rate constants for ktoRISC(T2) are almost identical to ktoRISC (=ktoRISC(T1) + ktoRISC(T2)) (Table 1 and Fig. 2j–l), indicating that the T1 → T2 → S1 transition is the dominant RISC pathway. It should also be noted that ktoRISC is much smaller than kRISC(T2 → S1). This is because the downhill T2 → T1 IC is rapid compared with the uphill T1 → T2 IC and T2 → S1 RISC. Thus, in addition to increasing kRISC(T2 → S1), decreasing ΔE(T1 → T2) is also crucial for accelerating T2-mediated RISC.

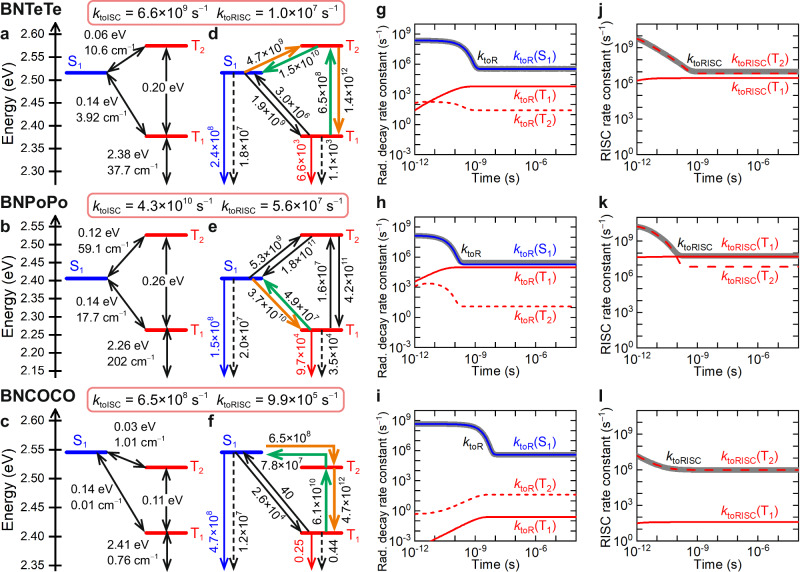

Computational results for BNTeTe and BNPoPo

From the above discussion, we expected further enhanced RISC by further increasing the atomic number of the included atoms. Hence, we next replaced Se with Te or Po (Fig. 1d and e) to further increase the SOCs and accelerate RISC. HOMO − 1, HOMO, and LUMO of BNTeTe and BNPoPo are similar to those of BNOO, BNSS, and BNSeSe (Fig. 1). Regarding BNTeTe (Fig. 3a), the energy level alignment of S1, T1, and T2 is almost identical to those of BNSS and BNSeSe (Fig. 2b, c). Hence, the S/Se→Te replacement affected ktoRISC by enhancing the S1–T1 and S1–T2 SOCs. We calculated the S0–T1, S1–T1, and S1–T2 SOCs of BNTeTe to be 37.7, 3.92, and 10.6 cm−1, respectively, which are 3 to 4 times those of BNSeSe (13.5, 0.84, and 3.32 cm−1, respectively). As a result, all SOC-related rate constants (kISC(S1 → T1), kISC(S1 → T2), kRISC(T2 → S1), kRISC(T1 → S1), kNR(T1 → S0), and kPhos(T1 → S0)) of BNTeTe were larger than those of BNSeSe. In contrast, kF(S1 → S0) and kNR(S1 → S0) of BNTeTe were comparable to those of BNSS and BNSeSe. Thus, acceleration of RISC is possible without sacrificing radiative decay and PLQY (Fig. 3d, g, j). The contributions of direct ISC and direct RISC to total ISC and total RISC processes, respectively, were more substantial for BNTeTe than for BNSeSe. However, the stepwise T2-mediated process was still dominant (70% of the total process; Fig. 3j). The calculated ktoRISC of BNTeTe was on the order of 107 s−1. kPhos also increased but on the order of 103 s−1; therefore, phosphorescence was still negligible (ΦPhos(T1) = 0.02), and T1 excitons were preferentially converted into light as TADF (Fig. 3g). Thus, BNTeTe is a promising MR–TADF emitter with fast RISC.

Fig. 3. Excited-state decay mechanism.

a–c Calculated excited-state energy diagram, energy differences (eV), and spin–orbit couplings (cm−1) and d–f rate constants (s−1) for BNTeTe, BNPoPo, and BNCOCO. g–i Calculated ktoR, ktoR(S1), ktoR(T1), and ktoR(T2) for BNTeTe, BNPoPo, and BNCOCO. j–l Calculated ktoRISC, ktoRISC(T1), and ktoRISC(T2) for BNTeTe, BNPoPo, and BNCOCO. In d–f, the solid orange arrows depict the dominant S1 → T1 pathway, the solid green arrows depict the dominant T1 → S1 pathway, the solid black arrows depict the minor S1 → T1 and T1 → S1 pathways, the solid blue arrows depict the S1 → S0 fluorescence, the solid red arrows depict the T1 → S0 phosphorescence, and the dashed arrows show S1 → S0 and T1 → S0 nonradiative decays. In g–i, the solid grey curves depict ktoR, the blue curves depict ktoR(S1), the solid red curves depict ktoR(T1), and the dashed red curves depict ktoR(T2). In j–l, the solid grey curves depict ktoRISC, the solid red curves depict ktoRISC(T1), and the dashed red curves depict ktoRISC(T2). Source data for g–l are provided as a Source Data file.

Po has a more substantial heavy atom effect than Te (Fig. 3b); hence, one can expect that BNPoPo would also be an excellent TADF emitter with much faster RISC (although Po compounds are radioactive, we performed calculations to understand the heavy atom effect). In contrast to our expectation, BNPoPo exhibited substantial phosphorescence as well as TADF (ΦPhos = 0.28 and ΦTADF = 0.55; Table 1 and Fig. 3e show rate constants). Therefore, BNPoPo would not be a pure TADF emitter (Fig. 3h), although it exhibited the fastest ktoRISC of 5.6 × 107 s−1 because of the substantial heavy atom effect of Po. This is different from all the other compounds in this study (they are pure TADF emitters). Interestingly, the dominant RISC processes are found to change from T1 → T2 → S1 to direct T1 → S1 process at 10-10 s for BNPoPo (Fig. 3k). Our proposed method also provides such detailed exciton dynamics.

Computational results for BNCOCO

We investigated another approach to accelerating RISC: C = O substitution. Figure 1f shows the designed molecule (BNCOCO). We calculated ΔE(T1 → S1) of BNCOCO to be 0.14 eV (Fig. 3c); which is comparable to those of BNSS, BNSeSe, BNTeTe, and BNPoPo. S1–T2 SOC of BNCOCO (1.01 cm−1, Fig. 3c) is only slightly smaller than that of BNSS (1.17 cm−1, Fig. 2b). Although T2 → S1 RISC is downhill for BNSS and uphill for BNCOCO, the energy gaps for T2 → S1 were small in both cases. Consequently, the kRISC(T2 → S1) of BNCOCO is only slightly smaller than that of BNSS. In contrast, the reduced ΔE(T1 → T2) induced a faster T1 → T2 transition than in BNSS, resulting in a larger ktoRISC (9.9 × 105 s−1) than BNSS (2.5 × 105 s−1). ktoISC and ktoRISC of BNCOCO are close to those of BNSeSe. The large spatial overlap between HOMO and LUMO + 1 around the C = O groups (Fig. 1f) lowers the T2 energy level, minimising ΔE(T1 → T2) and leading to the large ktoRISC even without chalcogen atoms.

A method for minimising ΔE(T1 → T2)

Here, we would like to discuss another approach to minimise ΔE(T1 → T2), which is effective in increasing ktoRISC. Supplementary Fig. 8a shows a case when T1 and T2 consist of HOMO → LUMO and HOMO−1 → LUMO transitions, respectively. ΔE(T1 → T2) can be written as ΔE(T1 → T2) = (hHH−hH−1H−1) + (JHH−JH−1H−1) + (JHL−JH−1L), where h denotes the core integral (kinetic and potential energies), J denotes the Coulomb integral, and K denotes the exchange integral44 (see Supplementary Method 6 for the detail). A simple approach of minimising ΔE(T1 → T2) is to decrease the first term hHH−hH−1H−1, which is possible by expanding the HOMO and HOMO−1 distributions (the second and third terms of ΔE(T1 → T2), expressed in terms of the Coulomb integrals, are not easy to control). Supplementary Fig. 8b shows a case where T1 and T2 consist of the HOMO → LUMO and HOMO → LUMO + 1 transitions, respectively. In this case, ΔE(T1 → T2) can be written as ΔE(T1 → T2) = (hL+1L+1−hLL) + (JHH+1−JHL) + (KHL+1 − KHL). For the same reason, expanding the LUMO + 1 and LUMO distributions results in an effective approach to minimise ΔE(T1 → T2) by decreasing hL+1L+1−hLL. Regardless of whether T2 is described as the HOMO−1 → LUMO or HOMO → LUMO + 1 transition, expanding molecular orbitals relevant for T1 and T2 is a simple way to decrease ΔE(T1 → T2) and accelerate the T2-mediated RISC process. Comparison of ν-DABNA-core and V-DABNA-core is a good example45. V-DABNA has a larger π-conjugation than ν-DABNA and hence, V-DABNA shows a smaller ΔE(T1 → T2) of 98 meV than ν-DABNA-core (147 meV). This trend can be also seen in several other examples46–50 (Supplementary Table 15).

Exciton dynamics

The above discussion indicates that the rate constants, including those of ISC and RISC, and quantum yields can be predicted quantitatively. This method also provides quantitative details on the exciton dynamics. Figures 2g–l and 3g–l show the time evolutions of respective rate constants. Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3 also show the time evolutions of respective exciton concentrations. These analyses enable complete elucidation of the emission mechanism. As shown in Figs. 2g–l and 3g–l, the total radiative, ISC, and RISC rate constants, corresponding to experimentally observed ones, are not constant and time-dependent because they are composed of multiple processes. Initially, ktoR is very large (108−109 s−1) but decreases to 104−105 s−1. These time evolutions, corresponding to prompt and delayed emissions, respectively, are automatically calculated by our method, including the transition states. Figures 2j–l and 3j–l show that ktoRISC’s are also time-dependent; initially, they are very large and stay constant after ~10−10−10−9 s. Figure 3k shows that the RISC mechanism of BNPoPo changed from the T2-mediated RISC to direct T1 → S1 RISC at ~0.1 ns as described above.

Theoretically prediction of linewidths of PL spectra

Finally, we theoretically calculated and predicted the FWHM values of the emission spectra by the vertical gradient method implemented in the ORCA 5.0.3 program package40–42. The calculated FWHM values of BNOO, BNSS, and BNSeSe agree well with the experimental values (Table 1 and Supplementary Figs. 4–6), confirming the validity of the calculations. Regarding BNTeTe, BNPoPo, and BNCOCO, the predicted FWHM values were 47–50, 52–56, and 43–46 nm, respectively (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 7); which are comparable to those for BNOO, BNSS, and BNSeSe. Thus, acceleration of RISC is possible without sacrificing the FWHM of the emission spectra.

Discussion

We comprehensively investigated the RISC mechanism of MR–TADF emitters, BNOO, BNSS, and BNSeSe by calculating all the relevant rate constants and quantum yields. The calculated values are in quantitative agreement with the experimental results. The ISC and RISC in BNOO, BNSS, and BNSeSe were found to occur predominantly via T2. We also found that incorporating S and Se into the molecules was effective in accelerating RISC. Therefore, BNTeTe and BNPoPo were designed to further increase kRISC. The strong heavy atom effect of Te enabled BNTeTe to exhibit kRISC of 107 s−1, which is larger than those of BNOO (104 s−1), BNSS (105 s−1), and BNSeSe (106 s−1). Meanwhile, although BNPoPo had the largest kRISC of 5.6 × 107 s−1, it exhibited a substantial contribution of phosphorescence because of the excessive heavy atom effect of Po. Our findings suggest that a moderately strong SOC that does not cause phosphorescence and suitable energy alignments are the keys to accelerating RISC in pure TADF. We also investigated BNCOCO to attain large kRISC without heavy atoms. BNCOCO had an S1–T2 SOC comparable to BNSS but a smaller T1–T2 energy difference, resulting in a larger kRISC of 106 s−1.

Distinct from conventional TADF, RISC has been rate-limiting in MR-TADF, and addressing this problem is currently the most important issue in further improving its characteristics. The calculated kF(S1 → S0), Φ, and FWHM values of the emission spectra are nearly identical for all the compounds in this study. This study reveals the solution that the rate constants of RISC can be substantially improved without sacrificing the PLQY, rate constant of radiative decay, and emission linewidth.

Finally, we would like to discuss further acceleration of RISC. The kRISC(T2 → S1) of BNTeTe was large (1.5 × 1010 s−1) because of the large SOC and downhill transition. However, the ktoRISC was three orders of magnitude smaller (1.0 × 107 s−1). This is because in the dominant process of RISC (T1 → T2 → S1), kIC(T2 → T1) (1.4 × 1012 s−1) is much larger than kIC(T1 → T2) (6.5 × 108 s−1) and kRISC(T2 → S1). The small kIC(T1 → T2) results in a slow pump-up of excitons from T1 to T2. Even if excitons are up-converted from T1 to T2, they quickly return to T1 ([T2] ≪ [T1]). This problem can be solved by minimising the energy difference between T1 and T2 (eventually to zero) yet preserving the T2 → S1 transition downhill. This situation corresponds to a system in which S1 is energetically lower than T1. Recently, it has been revealed that molecules with an S1 that is lower in energy than T1 can be realised despite violating Hund’s rule51–56. Such inverted S1–T1 (iST) systems have an ideal energy level diagram that enables the aforementioned downhill direct RISC process without the T1 → Tn IC process. iST molecules have frontier orbital distributions that are similar to MR-TADF; HOMO and LUMO are localised on different atoms, having short-range CT characters. Our calculation method for MR–TADF can be directly applied to designing iST molecules, enabling further enhanced RISC and a comprehensive understanding of their emission mechanisms.

In this study, we proposed a theoretical method of predicting the energy level alignments, including higher lying states as well as S1 and T1, by combining conventional B3LYP and B2-PLYP double-hybrid functionals. Second, we devised a method of calculating RISC (and ISC) rate constants considering RISC (and ISC) mechanisms consisting of multiple pathways. Although only S1, T1, and T2 are involved in the emission mechanism of molecules in this study, the method proposed here is robust enough to be applied to the case where many higher-lying states are involved. The theoretical advances enable us to quantitatively predict all the relevant rate constants and quantum yields. It is demonstrated that it is important to consider the entire system for quantitative understanding of the actual emission mechanism. To quantitatively understand RISC for all the compounds here, it is not sufficient to consider only the T1→S1 process; IC plays an important role, albeit indirect.

Our method of calculating rate constants and quantum yields is not limited to such MR-TADFs and iSTs. The range of applications is vast, including electronic transitions in, e.g. biochemical, biomedical, pharmaceutical systems, chemical reactions, and surface science. We have also confirmed the applicability of this method to a wide range of TADF emitters other than MR-type molecules and to catalytic photooxygenation to inhibit aggregation of amyloid-β peptide as a therapeutic strategy for Alzheimer’s disease57.

One phenomenon often consists of combinations of several elementary processes. Of these processes, only a key process has so far been focused on. However, as in the present example, all processes are often closely related. Our physics-based method is therefore important for obtaining a comprehensive understanding of phenomena and for quantitative predictions, including the time evolutions, which enable discovery of superior systems.

Methods

Calculations of rate constants for TADF, phosphorescence, total ISC, total RISC, and radiative decay based on excited-state populations

We calculated the rate constants for fluorescence from S1 to S0 (kF(S1 → S0)), Tn → S0 phosphorescence (kPhos(Tn → S0)), S1 → S0 nonradiative decay (kNR(S1 → S0)), Tn → S0 nonradiative decay (kNR(Tn → S0)), Tm → Tn internal conversion (kIC(Tm → Tn)), S1 → Tn ISC (kISC(S1→Tn)), and Tn → S1 RISC (kRISC(Tn → S1)) (m, n = 1, 2, m ≠ n) with Supplementary Eqs. (A1)–(A18) (Supplementary Method 1). Sn (n ≥ 2) and Tm (m ≥ 3) were located 0.3 eV higher in energy than S1, resulting in very small contributions for all compounds in this study; therefore, we neglected their contributions to the TADF mechanism. We performed geometric optimisation and frequency analysis of S1 for BNOO, BNSS, BNSeSe, BNTeTe, BNPoPo, and BNCOCO by the TD-TPSSh method (Supplementary Tables 1−6 and Supplementary Fig. 1 shows the optimised geometries). Then, we performed the excited-state calculations with the TD–B3LYP method using the optimised S1 geometries (Supplementary Tables 7−12). For H, B, C, N, O, and S atoms, we used the 6–31G(d) basis set. For Se, Te, and Po atoms, we used the Stuttgart/Dresden pseudopotentials and basis set (SDD)58. The geometrical optimisations, frequency analyses, and excited-state calculations were performed with the Gaussian 16 program package (Wallingford, CT, USA)59.

Calculations of SOCs, vibronic coupling constants, transition dipole moments, and permanent dipole moments were carried out by the TD–B3LYP method (TD–DFT with the B3LYP functional and 6–31G(d)+SDD basis set), in which the SOCs, vibronic coupling constants, and T1–T2 transition dipole moments were calculated with the method proposed by McMurchie and Davidson60 (Supplementary Method 2 and Code availability below), whereas the permanent dipole moments and S0–S1 transition dipole moment were calculated with the Gaussian 16 program package. We performed the TDA–B2-PLYP calculations with the ORCA 5.0.3 program package (FACCTs, Cologne, Germany)40–42 and the ADC(2) and SCS–CC2 calculations with the TURBOMOLE program package43.

The derivations of rate constants of individual elementary processes are shown in Supplementary Method 3. Here, we show the derivations of rate constants composed of multiple processes. Previously, rate constants for prompt and delayed fluorescence and RISC have been determined from transient photoluminescence (trPL) decay curves (number of photons counted vs. time plot)20, which are difficult to use for separately analysing delayed fluorescence and phosphorescence, especially when their time scales are close. In this study, we propose a method of calculating these rate constants from the excited-state populations, [Sn] and [Tn] (n = 1, 2, 3, ...). Our method distinguishes delayed fluorescence and phosphorescence, which does not require calculating a trPL decay curve.

The rate for the total ISC from the excited singlet states (Sn (n = 1, 2, 3, ...)) to the triplet states (Tm (m = 1, 2, 3, ...)) can be expressed as

| 1 |

which can be written in terms of the total population of the excited singlet states as

| 2 |

Therefore, the rate constant for the total ISC ktoISC can be defined as

| 3 |

Here, the effect of kIC(Sn’→Sn”) on ktoISC are included in the [Sn] populations because [Sn] are calculated by solving the kinetic equations that include all the elementary transitions (see Supplementary Method 3).

Furthermore, the rate for the total RISC from the triplet states to the excited singlet states can be expressed as

| 4 |

which can be written in terms of the total population of the triplet states as

| 5 |

Therefore, the rate constant for the total RISC ktoRISC can be defined as

| 6 |

Note that ktoISC and ktoRISC are functions of time (t) through the time dependence of [Sn] and [Tm], respectively. As in the case of kIC(Sn’→Sn”), the effect of kIC(Tm’→Tm”) on ktoRISC are included in the [Tm] populations (see Supplementary Method 3). The values of ktoISC and ktoRISC depend on the time domain in which they are calculated. The rate for the total radiative decay from the excited singlet and triplet states is

| 7 |

which can be written in terms of the total population of the excited states as

| 8 |

Hence, the rate constant for the total radiative decay (ktoR) can be defined as

| 9 |

As in ktoISC and ktoRISC, ktoR is a function of t.

As stated previously, regarding BNOO, BNSS, BNSeSe, BNTeTe, BNPoPo, and BNCOCO, it is sufficient to consider only S1, T1, and T2. Hence, ktoISC, ktoRISC, and ktoR can be written as

| 10 |

| 11 |

| 12 |

The contributions from T1 → S1 and T2 → S1 RISCs to ktoRISC are defined as

| 13 |

| 14 |

The contributions from S1 → S0 fluorescence ktoR(S1), T1 → S0 phosphorescence ktoR(T1), and T2 → S0 phosphorescence ktoR(T2) to ktoR, are defined as

| 15 |

| 16 |

| 17 |

Regarding fluorescent molecules with negligibly small kPhos(T1 → S0) and kPhos(T2 → S0), such as BNOO/BNSS/BNSeSe/BNTeTe/BNCOCO, ktoR ~ kF(S1 → S0) when [T1] ≪ [S1] and [T2] ≪ [S1] (this condition holds in the time domain immediately after the S0 → S1 photoexcitation). After sufficient time has passed following the excitation, S1, T1, and T2 are thermally equilibrated, and [S1]/([S1] + [T1] +[T2]) becomes constant (Figs. 2 and 3, and Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3). In such a time domain, ktoR ~ kF(S1 → S0) × [S1]/([S1] + [T1] +[T2]), which can be viewed as the rate constant for TADF (ktoR ~ kTADF). For molecules that emit both fluorescence and phosphorescence, such as BNPoPo, ktoR is intrinsically the population-weighted average of kF(S1 → S0), kPhos(T1 → S0), and kPhos(T2 → S0) (Eq. (12)). The lifetimes for the total radiative decay (τtoR) and TADF (τTADF) can be calculated as τtoR = 1/ktoR and τTADF = 1/kTADF, respectively. Yersin et al. derived τtoR for organometal complexes61. Equations (9) and (12) are corrected from their equations (Supplementary Method 3 shows a detailed comparison).

Calculations of rate constants for prompt fluorescence, TADF, and RISC based on transient photoluminescence decay curves

Experimentally, TADF properties have often been discussed in terms of the RISC rate constant (ktoRISC′) determined from a trPL decay curve. Here, ktoRISC′ denotes the trPL-based rate constant, whilst ktoRISC denotes the excited-state population-based rate constant (Eqs. (6) or (11)). We previously proposed an expression for ktoRISC′ under the assumption that the triplet states do not decay radiatively nor nonradiatively20:

| 18 |

where kPrompt and kDelayed denote the rate constants for prompt and delayed luminescence, respectively, determined by exponential fitting of a trPL decay curve. KtoRISC′ cannot be applied to emitters having phosphorescent contributions such as BNPoPo. Although ktoRISC is almost identical to ktoRISC′ for BNOO, BNSS, BNSeSe, BNTeTe, and BNCOCO (in which kPhos(T1 → S0) and kNR(T1 → S0) are negligibly small (Table 1)), ktoRISC is applicable to molecules that exhibit prompt fluorescence, delayed fluorescence, and phosphorescence simultaneously; which is more universal than ktoRISC′.

Supplementary information

Source data

Acknowledgements

The quantum chemical calculations were performed on the SuperComputer System, Institute for Chemical Research, Kyoto University. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI grant numbers: JP20H05840 (Grant-in-Aid for Transformative Research Areas, “Dynamic Exciton”, H.K.), JP22K05252 (K.S.), and JSPS Core-to-Core Programme: JPJSCCA20220004 (H.K.). We thank Michael Scott Long, PhD, at Edanz (https://jp.edanz.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Author contributions

K.S. performed the theoretical calculations. H.K. planned and supervised the project. All authors contributed to the writing of this manuscript and have approved the final version.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

The Gaussian 16 and ORCA input and output files are deposited in the figshare data repository [10.6084/m9.figshare]. The source data underlying Figs. 2g–l and 3g–l are provided as a Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code used to generate Table 1 and Figs. 2 and 3 is available on GitHub [https://github.com/KatsuyukiShizu/d77) and Zenodo [10.5281/zenodo.11124543].

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-024-49069-4.

References

- 1.Hatakeyama T, et al. Ultrapure blue thermally activated delayed fluorescence molecules: efficient HOMO–LUMO separation by the multiple resonance effect. Adv. Mater. 2016;28:2777–2781. doi: 10.1002/adma.201505491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kondo Y, et al. Narrowband deep-blue organic light-emitting diode featuring an organoboron-based emitter. Nat. Photon. 2019;13:678–682. doi: 10.1038/s41566-019-0476-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naveen KR, Yang HI, Kwon JH. Double boron-embedded multiresonant thermally activated delayed fluorescent materials for organic light-emitting diodes. Commun. Chem. 2022;5:149. doi: 10.1038/s42004-022-00766-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsui K, et al. One-shot multiple borylation toward BN-doped nanographenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:1195–1198. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b10578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li X, et al. Thermally activated delayed fluorescence carbonyl derivatives for organic light-emitting diodes with extremely narrow full width at half-maximum. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019;11:13472–13480. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b19635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun D, et al. The design of an extended multiple resonance TADF emitter based on a polycyclic amine/carbonyl system. Mater. Chem. Front. 2020;4:2018–2022. doi: 10.1039/D0QM00190B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y, et al. Multi-resonance deep-red emitters with shallow potential-energy surfaces to surpass energy-gap law. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021;60:20498–20503. doi: 10.1002/anie.202107848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bohne C, Abuin EB, Scaiano JC. Characterization of the triplet-triplet annihilation process of pyrene and several derivatives under laser excitation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:4226–4231. doi: 10.1021/ja00167a018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park IS, Min H, Yasuda T. Ultrafast triplet–singlet exciton interconversion in narrowband blue organoboron emitters doped with heavy chalcogens. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022;61:e202205684. doi: 10.1002/anie.202205684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu YX, et al. Efficient selenium-integrated TADF OLEDs with reduced roll-off. Nat. Photon. 2022;16:803–810. doi: 10.1038/s41566-022-01083-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Northey T, Penfold TJ. The intersystem crossing mechanism of an ultrapure blue organoboron emitter. Org. Electron. 2018;59:45–48. doi: 10.1016/j.orgel.2018.04.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin L, Fan J, Cai L, Wang C-K. Excited state dynamics of new-type thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitters: theoretical view of light-emitting mechanism. Mol. Phys. 2018;116:19–28. doi: 10.1080/00268976.2017.1362119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim I, et al. Three states involving vibronic resonance is a key to enhancing reverse intersystem crossing dynamics of an organoboron-based ultrapure blue emitter. JACS Au. 2021;1:987–997. doi: 10.1021/jacsau.1c00179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shizu K, Kaji H. Comprehensive understanding of multiple resonance thermally activated delayed fluorescence through quantum chemistry calculations. Commun. Chem. 2022;5:53. doi: 10.1038/s42004-022-00668-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stavrou K, Danos A, Hama T, Hatakeyama T, Monkman A. Hot vibrational states in a high-performance multiple resonance emitter and the effect of excimer quenching on organic light-emitting diodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2021;13:8643–8655. doi: 10.1021/acsami.0c20619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wada Y, Nakagawa H, Matsumoto S, Wakisaka Y, Kaji H. Organic light emitters exhibiting very fast reverse intersystem crossing. Nat. Photon. 2020;14:643–649. doi: 10.1038/s41566-020-0667-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wada Y, Wakisaka Y, Kaji H. Efficient direct reverse intersystem crossing between charge transfer-type singlet and triplet states in a purely organic molecule. ChemPhysChem. 2021;22:625–632. doi: 10.1002/cphc.202001013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El-Sayed M. Spin–orbit coupling and the radiationless processes in nitrogen heterocyclics. J. Chem. Phys. 1963;38:2834. doi: 10.1063/1.1733610. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ren Y, et al. Efficient blue thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitters showing very fast reverse intersystem crossing. Appl. Phys. Expr. 2021;14:071003. doi: 10.35848/1882-0786/ac06df. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shizu K, Ren Y, Kaji H. Promoting reverse intersystem crossing in thermally activated delayed fluorescence via the heavy-atom effect. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2023;127:439–449. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpca.2c06287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pratik SM, Coropceanu V, Brédas J-L. Enhancement of thermally activated delayed fluorescence (TADF) in multi-resonant emitters via control of chalcogen atom embedding. Chem. Mater. 2022;34:8022–8030. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.2c01952. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hua T, et al. Heavy-atom effect promotes multi-resonance thermally activated delayed fluorescence. Chem. Eng. J. 2021;426:131169. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2021.131169. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park IS, Yang M, Shibata H, Amanokura N, Yasuda T. Achieving ultimate narrowband and ultrapure blue organic light-emitting diodes based on polycyclo-heteraborin multi-resonance delayed-fluorescence emitters. Adv. Mater. 2022;34:2107951. doi: 10.1002/adma.202107951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagata M, et al. Fused-nonacyclic multi-resonance delayed fluorescence emitter based on ladder-thiaborin exhibiting narrowband sky-blue emission with accelerated reverse intersystem crossing. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021;60:20280–20285. doi: 10.1002/anie.202108283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luo, X.-F. et al. High-efficiency and narrowband OLEDs from blue to yellow with ternary boron/nitrogen-based polycyclic heteroaromatic emitters. Adv. Opt. Mater. 10, 2200504 (2022).

- 26.Tanaka H, Shizu K, Nakanotani H, Adachi C. Dual intramolecular charge-transfer fluorescence derived from a phenothiazine-triphenyltriazine derivative. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2014;118:15985–15994. doi: 10.1021/jp501017f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Sa Pereira D, et al. The effect of a heavy atom on the radiative pathways of an emitter with dual conformation, thermally-activated delayed fluorescence and room temperature phosphorescence. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2019;7:10481–10490. doi: 10.1039/C9TC02477H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Drummond BH, et al. Selenium substitution enhances reverse intersystem crossing in a delayed fluorescence emitter. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2020;124:6364–6370. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.0c01499. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu X, et al. Fabrication of circularly polarized MR-TADF emitters with asymmetrical peripheral-lock enhancing helical B/N-doped nanographenes. Adv. Mater. 2022;34:2105080. doi: 10.1002/adma.202105080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Han X, et al. Modulation of triplet-mediated emission from selenoxanthen-9-one-based D–A–D type emitters through tuning the twist angle to realize electroluminescence efficiency over 25% J. Mater. Chem. C. 2022;10:7437–7442. doi: 10.1039/D2TC00899H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aloïse S, et al. The benzophenone S1(n,π*) → T1(n,π*) states intersystem crossing reinvestigated by ultrafast absorption spectroscopy and multivariate curve resolution. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2008;112:224–231. doi: 10.1021/jp075829f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yuan Y, et al. The design of fused amine/carbonyl system for efficient thermally activated delayed fluorescence: novel multiple resonance core and electron acceptor. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2019;7:1801536. doi: 10.1002/adom.201801536. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zou S-N, et al. Fully bridged triphenylamine derivatives as color-tunable thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitters. Org. Lett. 2021;23:958–962. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c04159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hall D, et al. Improving processability and efficiency of resonant TADF emitters: a design strategy. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2020;8:1901627. doi: 10.1002/adom.201901627. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Min H, Park IS, Yasuda T. cis-Quinacridone-based delayed fluorescence emitters: seemingly old but renewed functional luminogens. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021;60:7643–7648. doi: 10.1002/anie.202016914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pershin A, et al. Highly emissive excitons with reduced exchange energy in thermally activated delayed fluorescent molecules. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:597. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08495-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tanaka H, et al. Hypsochromic shift of multiple-resonance-induced thermally activated delayed fluorescence by oxygen atom incorporation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021;60:17910–17914. doi: 10.1002/anie.202105032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin S, Ou Q, Shuai Z. Computational selection of thermally activated delayed fluorescence (TADF) molecules with promising electrically pumped lasing property. ACS Mater. Lett. 2022;4:487–496. doi: 10.1021/acsmaterialslett.1c00794. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sancho-García JC, et al. Violation of Hund’s rule in molecules: predicting the excited-state energy inversion by TD-DFT with double-hybrid methods. J. Chem. Phys. 2021;156:034105. doi: 10.1063/5.0076545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neese F. The ORCA program system. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. 2012;2:73–78. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Neese F. Software update: the ORCA program system, version 4.0. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2017;8:e1327. doi: 10.1002/wcms.1327. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neese F, Wennmohs F, Becker U, Riplinger C. The ORCA quantum chemistry program package. J. Chem. Phys. 2020;152:224108. doi: 10.1063/5.0004608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.TURBOMOLE v7.4.1 2019, a Development of University of Karlsruhe and Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe GmbH, 1989–2007 (TURBOMOLE GmbH, 2007). https://www.turbomole.org/turbomole/turbomole-documentation/

- 44.Szabo, A. & Ostlund, N. S. Modern Quantum Chemistry: Introduction to Advanced Electronic Structure Theory 87–89 (Dover Publications, New York, 1996).

- 45.Oda S, et al. One-shot synthesis of expanded heterohelicene exhibiting narrowband thermally activated delayed fluorescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022;144:106–112. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c11659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dos Santos JM, et al. An s-shaped double helicene showing both multi-resonance thermally activated delayed fluorescence and circularly polarized luminescence. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2022;10:4861–4870. doi: 10.1039/D2TC00198E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hall D, et al. Diindolocarbazole-achieving multiresonant thermally activated delayed fluorescence without the need for acceptor units. Mater. Horiz. 2022;9:1068–1080. doi: 10.1039/D1MH01383A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jin J, et al. Integrating asymmetric O−B−N unit in multi-resonance thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitters towards high-performance deep-blue organic light-emitting diodes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023;62:e202218947. doi: 10.1002/anie.202218947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu S, et al. Merging boron and carbonyl based MR-TADF emitter designs to achieve high performance pure blue OLEDs. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023;62:e202305182. doi: 10.1002/anie.202305182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Keruckiene R, et al. Is a small singlet–triplet energy gap a guarantee of TADF performance in MR-TADF compounds? Impact of the triplet manifold energy splitting. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2024;12:3450–3464. doi: 10.1039/D3TC04397E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leupin W, Wirz J. Low-lying electronically excited states of cycl[3.3.3]azine, a bridged 12π-perimeter. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980;102:6068–6075. doi: 10.1021/ja00539a016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ehrmaier J, et al. Singlet–triplet inversion in heptazine and in polymeric carbon nitrides. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2019;123:8099–8108. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpca.9b06215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.de Silva P. Inverted singlet–triplet gaps and their relevance to thermally activated delayed fluorescence. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2019;10:5674–5679. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.9b02333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ricci G, San-Fabián E, Olivier Y, Sancho-García JC. Singlet–triplet excited-state inversion in heptazine and related molecules: Assessment of TD-DFT and ab initio methods. ChemPhysChem. 2021;22:553–560. doi: 10.1002/cphc.202000926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li J, et al. Down-conversion-induced delayed fluorescence via an inverted singlet-triplet channel. Dyes Pigment. 2022;203:110366. doi: 10.1016/j.dyepig.2022.110366. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aizawa N, et al. Delayed fluorescence from inverted singlet and triplet excited states. Nature. 2022;609:502–506. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05132-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Furuta, M. et al. Leuco ethyl violet as self-activating prodrug photocatalyst for in vivo amyloid-selective oxygenation. Adv. Sci. 2401346 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Wadt WR, Hay PJ. Ab initio effective core potentials for molecular calculations. Potentials for main group elements Na to Bi. J. Chem. Phys. 1985;82:284–298. doi: 10.1063/1.448800. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian 16 rev. C.01. (Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford, CT, 2016).

- 60.McMurchie LE, Davidson ER. One- and two-electron integrals over cartesian Gaussian functions. J. Comput. Phys. 1978;26:218–231. doi: 10.1016/0021-9991(78)90092-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yersin H, Rausch AF, Czerwieniec R, Hofbeck T, Fischer T. The triplet state of organo-transition metal compounds. Triplet harvesting and singlet harvesting for efficient OLEDs. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2011;255:2622–2652. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.01.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The Gaussian 16 and ORCA input and output files are deposited in the figshare data repository [10.6084/m9.figshare]. The source data underlying Figs. 2g–l and 3g–l are provided as a Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

The code used to generate Table 1 and Figs. 2 and 3 is available on GitHub [https://github.com/KatsuyukiShizu/d77) and Zenodo [10.5281/zenodo.11124543].