Summary

Background

The after-care treatment project KTx360° aimed to reduce graft failure and mortality after kidney transplantation (KTx).

Methods

The study was conducted in the study centers Hannover, Erlangen and Hannoversch Muenden from May 2017 to October 2020 under the trial registration ISRCTN29416382. The program provided a multimodal aftercare program including specialized case management, telemedicine support, psychological and exercise assessments, and interventions. For the analysis of graft failure, which was defined as death, re-transplantation or start of long-term dialysis, we used longitudinal claims data from participating statutory health insurances (SHI) which enabled us to compare participants with controls. To balance covariate distributions between these nonrandomized groups we used propensity score methodology, in particular the inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) approach.

Findings

In total, 930 adult participants were recruited at three different transplant centres in Germany, of whom 320 were incident (enrolled within the first year after KTx) and 610 prevalent (enrolled >1 year after KTx) patients. Due to differences in the availability of the claims data, the claims data of 411 participants and 418 controls could be used for the analyses. In the prevalent group we detected a significantly lower risk for graft failure in the study participants compared to the matched controls (HR = 0.13, 95% CI = 0.04–0.39, p = 0.005, n = 389 observations), whereas this difference could not be detected in the incident group (HR = 0.92, 95% CI = 0.54–1.56, p = 0.837, n = 440 observations).

Interpretation

Our findings suggest that a multimodal and multidisciplinary aftercare intervention can significantly improve outcome after KTx, specifically in patients later after KTx. For evaluation of effects on these outcome parameters in patients enrolled within the first year after transplantation longer observation times are necessary.

Funding

The study was funded by the Global Innovation fund of the Joint Federal Committee of the Federal Republic of Germany, grant number 01NVF16009.

Keywords: Kidney transplantation, Case-management, Physical activity, Adherence, Cardiovascular risk, Graft survival

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

A PubMed search limited to published evidence before the study was initiated in 2016, with no restriction to language or article type, using the terms “kidney” AND “transplantation” AND “multimodal” AND “aftercare” which yielded 0 articles and the same search conducted on March 12, 2024 retrieved 5 publications: One with our published study design, one with results from one of our substudies describing physical activity and quality of life during the Covid pandemic,1 as well as three studies unrelated to kidney transplant aftercare. If “multimodal” is specifically replaced by “medication adherence” the search yields 7 results, if replaced by “exercise” the search yields 38 results: all articles see benefits either for adherence screenings/coachings or exercise and recommend larger studies.

Added value of this study

The claims data analysis suggests that a multimodal aftercare program, including specialized case management, telemedicine support, psychosocial and exercise assessments, and interventions can improve graft and patient survival in prevalent transplant patients.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our study was the first prospectively conducted study that established a multimodal aftercare program after kidney transplantation. In longitudinal claims data analysis from prevalent patients we could demonstrate significantly improved patient and transplant survival. In the first year after transplantation the event rate was too low and follow-up time was too short to discover any beneficial effect on patient and transplant survival.

Introduction

For the majority of patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD), the best form of therapy is a kidney transplantation (KTx), since it is associated with significantly reduced morbidity and mortality compared to dialysis.1,2 However, about 8% of patients lose their graft within the first three years after KTx, with a steady increase in subsequent years.3 Two major reasons for this progressive graft failure are chronic rejections, frequently triggered by suboptimal adherence, and death with a functioning graft due to cardiovascular events.4, 5, 6, 7 Against the background of a constant shortage of donor organs it would be very valuable to develop strategies for detecting and controlling modifiable risk factors such as cardiovascular disease (CVD) and non-adherence in KTx recipients.8 Increasing physical activity in patients has been shown to reduce their cardiovascular morbidity. Also, graft survival is better in physically active patients compared to patients less involved in physical activity.9 Several cohort studies confirmed that about 36% of graft failures per year result from non-adherence to immunosuppressants (IS)10,11 or missed aftercare appointments.12 There are no generally accepted aftercare programs that address these two factors systematically and jointly, since this would require a multimodal approach which cannot be offered in most post-KTx aftercare programs in Germany.

Even though we are in the era of digitalization, post-transplant care in Germany is not systematically digitalized and most health data are still exchanged via mail and fax with significant delays. In the German system, post-KTx aftercare has been traditionally split between the outpatient services of the transplant hospital and nephrologists in private practices, usually located close to the patient's place of residence, where the patient previously received dialysis. This system is an additional impediment to quality of care.

This program was designed as a prospective, longitudinal, multicentre, multisectorial, multimodal, and multidisciplinary program for patients of all ages with the primary goal of increasing graft survival and reducing mortality. To evaluate whether these interventions result in an improved graft survival and if there is a differential benefit for patients early (incident) and later (prevalent) after kidney transplantation, we used claims data from the participating statutory health insurances (SHI). These data provided us with longitudinal information on participating transplanted patients and from non-participating transplanted patients from both the three participating centres and those which were non-participating. Using this approach, it was possible to analyze the data in a “quasi-experimental design” and perform propensity score adjustments to reach the best possible level of comparability between participants and controls. Claims data are now frequently used in medical research as they provide valuable insights into healthcare utilization and trends.13, 14, 15 One of the major advantages of claims data is that they reflect real-world healthcare, allow tracking patients over time, and the study of disease progression and treatment outcomes. A disadvantage is that claims data often lack clinical detail and claims data on their own have only limited ability to establish causality. However, since it was possible to identify the patients participating in KTx360° in the claims data provided by the respective SHI, we were able to perform an unbiased analysis to compare the effect of our specific study interventions with propensity adjusted control cases.

Methods

Study design

A detailed description of the methodology is available in the published study protocol.16

KTx360° was planned as a quasi-experimental, prospective, observational study comparing incident and prevalent study participants with controls using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) as the propensity score method with longitudinal claims data from the SHI.

Ethics statement

Ethics approval was obtained from Hannover Medical School and the University of Erlangen ethics committees. Patients with cognitive impairment could participate if written consent by their legal guardians was provided. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before study entry.

Patient and public involvement

The German Federal Association of Renal Patients (‘Bundesverband Niere’) was actively involved in the planning of the study.

Participants

Participants were adult members of 36 different German SHI. All SHIs joined and supported the program but only 27 delivered claims data for the comparative analyses. Two cohorts of patients, incident and prevalent, were included in KTx360° in the study centers Hannover, Erlangen and Hannoversch Münden in Germany. Incident patients had undergone KTx less than one year ago and were asked to participate directly after transplantation. Prevalent patients had received a transplant more than one year ago. Participation was offered to all patients regardless of gender, age, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status.

Interventions

KTx360° consisted of several interventions and treatment modules which are described in more detail in the study protocol16 In brief, in addition to routine nephrological aftercare, KTx360° comprised case management and an internet-based case file (‘CasePlus®’, Symeda GmbH, Germany), that was used for documentation of all relevant data and which could be accessed by all team members, the patients and their nephrologists. KTx360° included regular psychosocial and cardiovascular risk assessments offered four times per year for incident patients and twice a year for prevalent patients. Adherence coaching and individualized sports therapy were offered based on the results of the assessments. Psychosocial risk assessments and adherence coaching were offered as a video chat or as a face-to-face consultation. Each patient was repeatedly evaluated by a mental health expert regarding non-adherence to IS and individual barriers for optimal adherence. Depending on the results of adherence assessments, the mental health team made different recommendations such as referral to an educational group or to individual adherence coaching. Up to eight sessions per year could be offered by a member of the mental health team. If the presence of other untreated mental disorders was detected, patients were referred for more intensive regular mental health care.

Sports therapy was also offered via video chat and as face-to-face consultations. Depending on the physical performance level of the individual, patients’ exercise recommendations included endurance training two to four times per week as well as regular resistance training. Training goals were defined for each patient individually and ranged from increasing physical activity in everyday life and improvement of mobility to participation in sports competitions. During a first cardiovascular risk assessment, participants received a physical examination and incremental exercise testing on a bicycle ergometer (Ergoline 150 P, ergoline GmbH, Bitz, Germany) to measure exercise capacity. The follow-up appointments included a 30 min endurance exercise training session with ECG and lactate.

Exercise training was monitored by an exercise physiologist via a wearable system (Forerunner 35; Garmin, Germany) to measure physical activities, daily activities (steps), and the respective heart rates. A regular feedback based on continuous training data was given up to once a month by video/phone conference to motivate patients and adapt the individual training recommendations when necessary.

Case managers were experienced transplant nurses who coordinated individual post-transplant care and offered continuous support to patients. The case management also included weekly case conferences (nephrologists, paediatric nephrologists, sports medicine specialists, mental health experts, and case managers) within the transplant centres and yearly quality circles of all stakeholders participating in the program to discuss and decide on standard operating procedures for all participating care givers.

In the participating centres, the surgical teams did not change over the study period and numbers of intra- and postoperative complications as well as percentage of living donation were stable.

Procedures

According to the study protocol, prevalent participants were included from May 2017 until October 2018 and incident participants between May 2017 and November 2019. The intervention was conducted until October 2020. Thus, the intervention period could range from 12 to 42 months per participant. Subjects were invited to participate in all modules of the program.

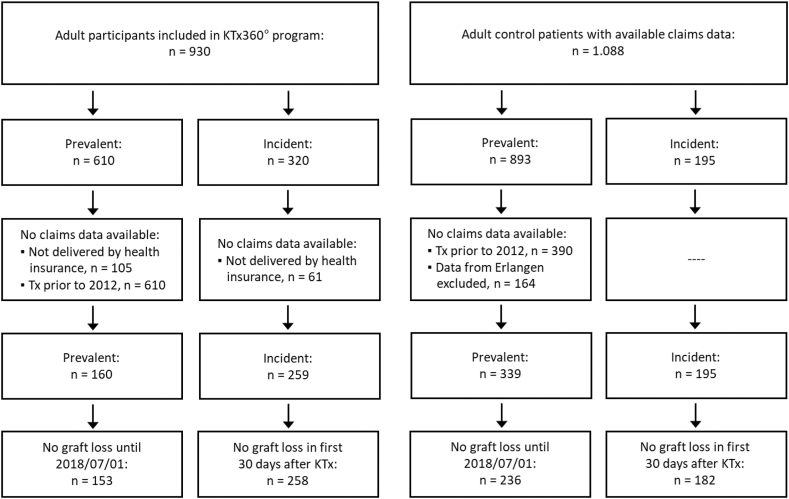

Claims data of controls and participants were available from 2012 to 2019. In Germany, the lengths of follow-back periods are limited for SHI. Thus, patients and controls who had their KTx before 2012 could no longer be tracked and needed to be excluded from further analyses. Additionally, not all participating SHI delivered the requested claims data for the patients who were enrolled in KTx360°.

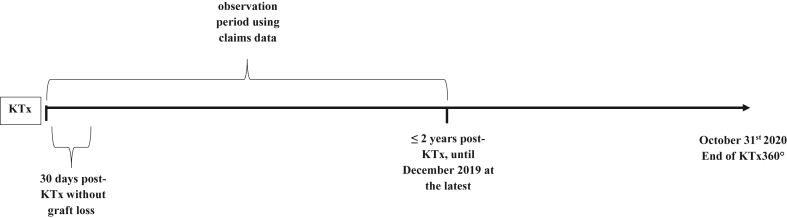

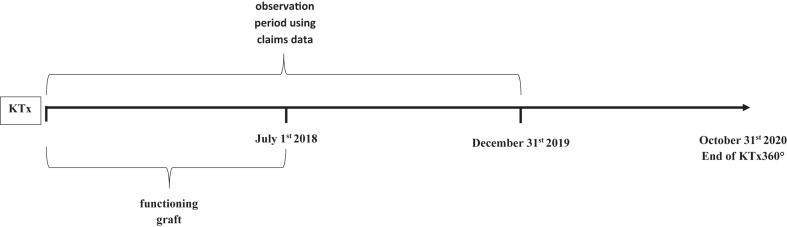

Incident controls were selected in parallel with incident participants. In the incident group, study participants and controls with early graft failure within 30 days after discharge from the hospital after KTx (Fig. 1) were excluded from further analyses. In the prevalent group, study participants and controls with a graft failure before July 1st 2018 were excluded (Fig. 2). This date was chosen since 98% of the prevalent participants were included into KTx360° by that date. Using the end of the recruitment period as the cutoff for graft failure instead of the start of the recruitment period was considered the more conservative approach since it minimized the problem of selective survival. Using this strategy, only two participants without prior graft failure recruited between August and October 2018 were omitted from the analysis. Their inclusion would have shortened the observation period at risk for graft failure by two months. Thus, in exchange for losing these two participants from the sample, we gained an additional two months of observation time. The median time between KTx and the start of the observation period was 3.4 years in prevalent controls and 2.9 years in prevalent participants (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Observation periods using claims data relative to the timepoint of kidney transplantation (KTx) for incident participants and controls.

Fig. 2.

Observation periods using claims data relative to the timepoint of kidney transplantation (KTx) for prevalent participants and controls.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants and controls of the analysis samples using claims data at the time of KTx.

| a) Incident participants and controls | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Controls (N = 182) | Participants (N = 258) | p-value | |

| Age, years | 0.726 | ||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 51 (42, 63) | 52.5 (43, 61.8) | |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.234 | ||

| Male | 114 (62.6%) | 147 (57.0%) | |

| Female | 68 (37.4%) | 111 (43.0%) | |

| Donation type, n (%) | 0.057 | ||

| Living | 24 (13.2%) | 52 (20.2%) | |

| Deceased | 158 (86.8%) | 206 (79.8%) | |

| Previous KTx, n (%) | 0.934 | ||

| Yes | 20 (11.0%) | 29 (11.2%) | |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 0.009 | ||

| Yes | 49 (26.9%) | 43 (16.7%) | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 0.013 | ||

| Yes | 103 (56.6%) | 176 (68.2%) | |

| CVD, n (%) | 0.384 | ||

| Yes | 40 (22.0%) | 48 (18.6%) | |

| Mental comorbidity, n (%) | 0.510 | ||

| Yes | 25 (13.7%) | 30 (11.6%) | |

| Duration of observation period, years | 0.004 | ||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 1.0 (0.6, 2.0) | 1.6 (0.8, 2.0) | |

| b) Prevalent participants and controls | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Controls (N = 236) | Participants (N = 153) | p-value | |

| Age, years | 0.083 | ||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 53 (41, 62) | 50 (39, 60) | |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.946 | ||

| Male | 138 (58.5%) | 90 (58.8%) | |

| Female | 98 (41.5%) | 63 (41.2%) | |

| Donation type, n (%) | 0.022 | ||

| Living | 47 (19.9%) | 46 (30.1%) | |

| Deceased | 189 (80.1%) | 107 (69.9%) | |

| Previous KTx, n (%) | 0.106 | ||

| Yes | 24 (10.2%) | 24 (15.7%) | |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 0.340 | ||

| Yes | 51 (21.6%) | 27 (17.6%) | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 0.861 | ||

| Yes | 146 (61.9%) | 96 (62.7%) | |

| CVD, n (%) | 0.174 | ||

| Yes | 36 (15.3%) | 16 (10.5%) | |

| Mental comorbidity, n (%) | 0.153 | ||

| Yes | 33 (14.0%) | 14 (9.2%) | |

| Start of observation period after KTx, years | 0.008 | ||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 3.4 (2.4, 4.4) | 2.9 (2.0, 3.9) | |

| Study participation start after KTx, years | – | ||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | – | 2.3 (1.3, 3.3) | |

| Duration of observation periods, years | 0.005a | ||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 1.5 (1.5, 1.5) | 1.5 (1.5, 1.5) | |

Q1, Q3, quartile 1 and 3, KTx, kidney transplantation, CVD, cardiovascular disease.

There were more patients with shorter observation periods in the control group.

In summary, the observation time for time-to-event analyses started 30 days after discharge from the hospital after KTx for the incident and on July 1st 2018 for the prevalent group and ended with one of the events defining graft failure or with right censoring when claims data ended or maximum observation time was reached. In incident participants and controls the maximum observation time was set at two years after KTx. The median observation times were 1 and 1.6 years for incident controls and participants, respectively, and 1.5 years for both prevalent controls and participants (Table 1a + b).

Outcomes

All data were extracted from the claims data of the SHI. Our primary outcome was graft failure. Graft failure was defined as death, re-transplantation, or start of long-term dialysis (≥10 dialysis treatments within 40 days). The claims data enabled us to identify the statutory health insurance of the individual patient. In the control participants, unfortunately, we were unable to identify the transplant centre where the transplantation was performed. Since claims data are primarily recorded for accounting purposes and not for research, detailed clinical data are unavailable. However, we were mainly interested in the hard endpoint “graft failure” which is also reliably coded in claims data. The data on comorbidity used for adjustment were taken from the codes recorded at the time of the hospital stay when the transplantation was performed.

One major advantage of our data is that we have information from 27 different German SHI, which increases the generalizability of our results since for historical reasons in Germany, each SHI differs in terms of the group of insured individuals.17

Statistical analyses

The distributions of continuous variables in the study sample were characterized descriptively using medians and quartiles, while relative frequencies were reported for categorical variables, and the absolute number of missing values was indicated for each variable. Between group differences were calculated using chi square tests, Fisher exact tests, t-tests, and Mann-Whitney-U-tests as appropriate. When comparing KTx360° participants and non-participants whose information was retrieved from claims data, potential imbalances in prognostic variables that may lead to biased conclusions needed to be taken into account. We used propensity score weighting with inverse probability of treatment weights (IPTW) to adjust for confounding, separately for the prevalent and the incident participants. The propensity score, formally defined as the predicted probability of being in the intervention group given the confounding variables, has been modelled using a logistic regression model that included sex, age, hypertension, CVD, diabetes mellitus, mental comorbidity, previous KTx, and donor type, as well as time since KTx for the analysis of prevalent participants and controls only. Due to the large overlap of the distributions of the propensity score in KTx360° participants and non-participants, we could efficiently use IPTW weighting in the Cox proportional hazards model for graft failure to estimate the hazard ratio (HR) of the KTx360° intervention controlled for the confounding effect of all variables that are the building blocks of the propensity score. More details about the IPTW propensity score method are given in the Supplementary File. For a comparison of the occurrence of graft failure over time between groups we provide Kaplan–Meier estimates using unweighted and weighted data.

Role of the funding source

The Innovation Fund of the Joint Federal Committee of the Federal Republic of Germany funded the study, grant number 01NVF16009. The Committee did not have any role in design and conduct of the study, analysis and interpretation of the data, preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and accept responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Participants

The study sample comprised 930 adult participants, 320 (34.4%) incident and 610 (65.6%) prevalent participants. The control sample consisted of 1088 kidney transplant patients, of which 195 were incident and 893 were prevalent cases. The flow of the participants and controls is depicted in Fig. 3. Baseline data for covariates that were treated as confounding variables in the propensity weighting are presented in Tables 1a and 1b For sample characteristics of prevalent and incident study participants at the time of enrolment into the study and at the time of KTx see Table 2, Table 3. Overall, the incident study participants (N = 320) had more documented comorbidities compared to the prevalent study participants (N = 610), with more previous smokers, higher BMI, higher cholesterol and creatinine values, a longer time on dialysis before transplantation and a higher rate of diabetes and CVD at the time of the KTx. However, the prevalence of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and CVD at the time of enrolment into our study did not differ between prevalent and incident participants.

Fig. 3.

Flow chart of participants and controls for claims data analyses.

Table 2.

Sample characteristics at enrolment into KTx360°.

| Prevalent (N = 610) | Incident (N = 320) | p-value | Total (N = 930) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at enrolment, years | 0.004 | |||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 56.0 (45.0, 64.0) | 52.0 (41.8, 61.0) | 55.0 (44.0, 63.0) | |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.760 | |||

| Missing | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Male | 362 (59.3%) | 186 (58.3%) | 548 (59.0%) | |

| Female | 248 (40.7%) | 133 (41.7%) | 381 (41.0%) | |

| Caucasian | 0.637 | |||

| Yes | 606 (99.3%) | 317 (99.1%) | 923 (99.2%) | |

| KTx centre, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Hannover | 423 (69.3%) | 228 (71.2%) | 651 (70.0%) | |

| Hann.-Münden | 187 (30.7%) | 45 (14.1%) | 232 (24.9%) | |

| Erlangen | – | 47 (14.7%) | 47 (5.1%) | |

| Time since KTx, years | <0.001 | |||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 6.5 (4.0, 10.0) | 1.0 (1.0, 1.0) | 3.0 (1.0, 8.0) | |

| Donation type, n (%) | 0.004 | |||

| Missing | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| Living | 188 (30.8%) | 70 (22.0%) | 258 (27.8%) | |

| Deceased | 422 (69.2%) | 248 (78.0%) | 670 (72.2%) | |

| Previous KTx, n (%) | 0.790 | |||

| Missing | 1 | 3 | 4 | |

| Yes | 92 (15.1%) | 50 (15.8%) | 142 (15.3%) | |

| Number of KTx, n (%) | 0.615 | |||

| 1 | 520 (85.2%) | 274 (85.6%) | 794 (85.4%) | |

| 2 | 69 (11.3%) | 38 (11.9%) | 107 (11.5%) | |

| 3 | 17 (2.8%) | 6 (1.9%) | 23 (2.5%) | |

| 4 | 4 (0.7%) | 1 (0.3%) | 5 (0.5%) | |

| 5 | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.3%) | 1 (0.1%) | |

| Previous smoker, n (%) | 0.026 | |||

| Missing | 75 | 22 | 97 | |

| Yes | 98 (18.3%) | 74 (24.8%) | 172 (20.6%) | |

| Active smoker, n (%) | 0.177 | |||

| Missing | 51 | 19 | 70 | |

| Yes | 49 (8.8%) | 35 (11.6%) | 84 (9.8%) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | <0.001 | |||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 24.6 (22.0, 27.3) | 25.7 (23.0, 28.6) | 24.8 (22.3, 27.7) | |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 0.422 | |||

| Yes | 106 (17.4%) | 49 (15.3%) | 155 (16.7%) | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 0.937 | |||

| Missing | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| Yes | 548 (90.1%) | 287 (90.0%) | 835 (90.1%) | |

| CVD, n (%) | 0.698 | |||

| Missing | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Yes | 69 (11.3%) | 39 (12.2%) | 108 (11.6%) | |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 0.003 | |||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 115.4 (94.1, 140.0) | 122.8 (96.5, 152.6) | 118.9 (95.0, 142.0) | |

| Serum creatinine (μmol/l) | 0.008 | |||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 137.0 (111.0, 180.0) | 148.7 (120.8, 190.5) | 140.0 (115.0, 183.0) |

Data taken from study data.

Q1, Q3, quartile 1 and 3, KTx, kidney transplantation, BMI, Body Mass Index, CVD, cardiovascular disease.

Table 3.

Sample characteristics at time of KTx.

| Prevalent (N = 610) | Incident (N = 320) | p-value | Total (N = 930) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of kidney insufficiency, months | <0.001 | |||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 63.7 (25.1, 97.8) | 93.1 (40.2, 127.4) | 72.5 (29.3, 110.7) | |

| Duration of dialysis, months | <0.001 | |||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 48.5 (18.0, 90.0) | 84.0 (30.5, 121.0) | 61.0 (21.0, 102.0) | |

| Type of dialysis, n (%) | 0.065 | |||

| Missing | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Hemodialysis | 465 (76.4%) | 264 (82.8%) | 729 (78.6%) | |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 87 (14.2%) | 36 (11.3%) | 123 (13.2%) | |

| Preemptive transplantation | 57 (9.4%) | 19 (6.0%) | 76 (8.2%) | |

| Dialysis after KTx, n (%) | 0.150 | |||

| Missing | 12 | 1 | 13 | |

| Yes | 90 (15.1%) | 37 (11.6%) | 127 (13.8%) | |

| Diabetes mellitus at KTx, n (%) | 0.017 | |||

| Yes | 64 (10.5%) | 51 (15.9%) | 115 (12.4%) | |

| CVD at KTx, n (%) | 0.032 | |||

| Yes | 48 (7.9%) | 39 (12.2%) | 87 (9.4%) | |

| HLA mismatches (A. B. DR) | 0.013 | |||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 3.0 (1.0, 4.0) | 3.0 (2.0, 4.0) | 3.0 (1.0, 4.0) | |

| Induction extracorporeal procedure, n (%) | 0.112 | |||

| Missing | 15 | 0 | 15 | |

| Immunoadsorption | 6 (1.0%) | 3 (0.9%) | 9 (1.0%) | |

| Plasmapheresis | 49 (8.2%) | 40 (12.5%) | 89 (9.7%) | |

| None | 540 (90.8%) | 277 (86.6%) | 817 (89.3%) | |

| Antibody induction, n (%) | 0.179 | |||

| Missing | 156 | 6 | 162 | |

| ATG | 91 (20.0%) | 67 (21.3%) | 158 (20.6%) | |

| ATG + Basiliximab | 5 (1.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (0.7%) | |

| Basiliximab | 358 (79.0%) | 247 (78.7%) | 605 (78.8%) |

Data taken from study data.

KTx, kidney transplantation, Q1, Q3, quartile 1 and 3, CVD, cardiovascular disease, HLA, human leukocyte antigen, ATG, Anti-Thymocyte Globulin.

Selectivity of KTx360° study participants and of the participants included in the analyses

Overall, 1526 patients were asked to participate. KTx patients, who chose not to participate in the KTx360° study, were significantly older, had a longer time since KTx, had more often received an organ from a deceased donor, had a higher rate of diabetes, and a lower rate of anaemia compared to the participants. There were no significant differences regarding sex, renal function, and hypertension.18

Only a proportion of the prevalent participants could be included in the propensity score analysis. We lost participants because the collaborating statutory health insurance did not deliver data for all participants but mainly because claims data are kept for only 5 years and for patients who were transplanted before 2012 claims data were no longer available. These two circumstances led to the loss of 450 participants in the prevalent intervention group. We therefore compared the subgroup of KTx360° participants who were included in the analyses (N = 411) with the entire KTx360° sample (N = 930) (Table 4, Supplementary Tables S7 and S8). Cardiovascular risk factors were common in the entire KTx360° sample and in the subsample included in the analyses. Despite significant differences (more diabetes mellitus and CVD but less hypertension in the analysis sample) the analysis sample appears to be a representative sample of the entire cohort.

Table 4.

Baseline characteristics of all KTx360° participants (variables from study data) and of the analysis sample (corresponding variables from claims data).

| All KTx360° Participants (N = 930) | Analysis sample (N = 411) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at KTx, years | 0.002 | ||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 49.0 (38.0, 58.0) | 52.0 (42.0, 61.0) | |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.650 | ||

| Missing | 1 | 0 | |

| Male | 548 (59.0%) | 237 (57.7%) | |

| Female | 381 (41.0%) | 174 (42.3%) | |

| KTx centre, n (%) | 0.001 | ||

| Hannover | 651 (7..0%) | 323 (78.6%) | |

| Hann.-Münden | 232 (24.9%) | 66 (16.1%) | |

| Erlangen | 47 (5.1%) | 22 (5.4%) | |

| Donation type, n (%) | 0.131 | ||

| Missing | 2 | 0 | |

| Living | 258 (27.8%) | 98 (23.8%) | |

| Deceased | 670 (72.2%) | 313 (76.2%) | |

| Previous KTx, n (%) | 0.244 | ||

| Missing | 4 | 0 | |

| Yes | 142 (15.3%) | 53 (12.9%) | |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 0.022 | ||

| Yes | 115 (12.4%) | 70 (17.0%) | |

| CVD, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 87 (9.4%) | 64 (15.6%) | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Missing | 3 | 0 | |

| Yes | 835 (90.1%) | 272 (66.2%) |

KTx, kidney transplantation, CVD, cardiovascular disease.

Comparison of baseline covariates between participants and controls

Data including standard means differences (SMDs) for all baseline covariates before and after IPTW propensity score weighting are presented separately for incident and prevalent participants and controls in Supplementary Tables S1–S4. The results demonstrate that IPTW was successful as SMDs were <0.1 for all covariates in both the prevalent and incident group. The largest SMDs were 0.019 and 0.022, respectively.

Participation in the program

Overall, 90.0% of the participants (89.7% of incident and 90.9% of prevalent participants) received one or more adherence assessments (M = 2.84; SD = 1.78; range: 0–10). Overall, 9.3% attended one or more individual coaching sessions in person (M = 0.26; SD = 1.25; range: 0–17), and 8.2% attended one or more digital coaching sessions (M = 0.23; SD = 0.99, range: 0–12) with no difference between incident and prevalent patients.

Overall, 87.7% of the participants received one or more cardiovascular risk assessments (84.7% of incident and 89.3% of prevalent participants) (M = 1.03; SD = 0.51; range: 0–3), 62.1% (49.4 incident and 64.6% prevalent participants) received one or more sports therapy session in person (M = 3.18; SD = 3.45; range 0–13), and 52.3% (73.1 incident and 69.7% prevalent participants) attended one or more digital sessions (M = 1.09; SD = 1.41; range: 0–8).

Almost all participants had at least one contact to the KTx360° case management (99.4%, 98.8 of incident and 99.7% of prevalent participants). On average, participants had 11.0 contacts (SD = 8.51, range = 0–78). More than 90% of the participating patients were discussed in the case conferences.

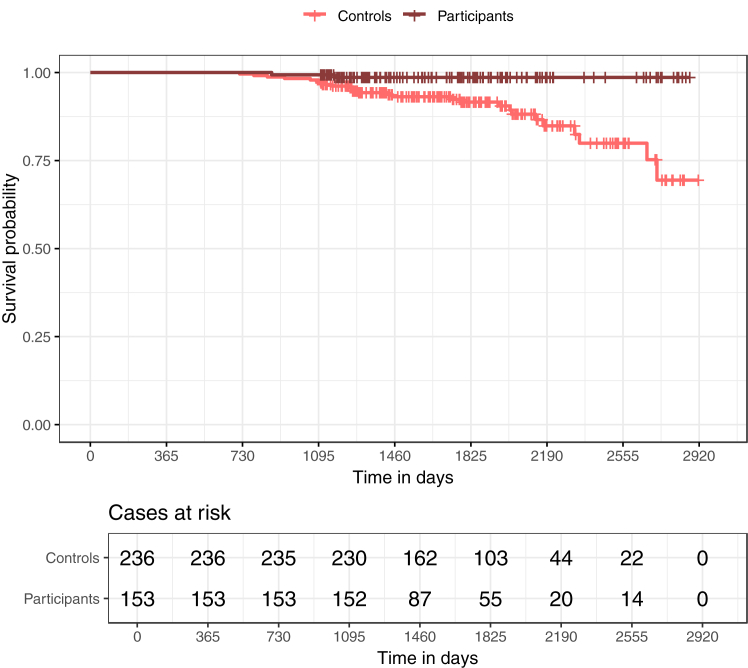

Graft failure

In the prevalent group the median observation period started in participants 2.9 years and in controls 3.4 years after KTx. The median duration of the observation period was 1.5 years in both groups. Graft loss was observed in 2 (1.3%) prevalent participants and in 26 (11.0%) prevalent controls over the full observation period. The adjusted HR was 0.13 (95% CI 0.04–0.39; p = 0.005) (Table 5), indicating a better graft survival in prevalent study participants for the full observation period after KTx.

Table 5.

Cox regression for graft failure for the full observation period after kidney transplantation (KTx) for prevalent patients adjusting for nine confounders using inverse probability of treatment weights (IPTW) in a propensity score analysis Full observation period.

| HR | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants vs Controls | 0.13 | 0.04–0.39 | 0.005 |

| Observations | 389 | ||

HR, Hazard Ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Confounding variables in the analysis are sex, age, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, mental comorbidity, previous KTx, donor type, time since KTx. The entire propensity score model is depicted in Supplementary Table S6.

In the incident group the duration of the median observation period was 1.6 years for participants and 1.0 year for the controls. Graft loss was observed in 15 (5.8%) incident participants and in 11 (6.0%) incident controls in the two-year observation period. The adjusted HR for the intervention effect was 0.92 (95% CI 0.54–1.56; p = 0.837) (Table 6). Therefore, there is no evidence of better graft survival in the incident study subjects.

Table 6.

Cox regression for graft failure in the first two years after kidney transplantation (KTx) for incident patients adjusting for eight confounders using inverse probability of treatment weights (IPTW) in a propensity score analysis.

| HR | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants vs Controls | 0.92 | 0.54–1.6 | 0.837 |

| Observations | 440 | ||

Observation period of 2 years.

HR, Hazard Ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Confounding variables in the analysis are sex, age, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, mental comorbidity, previous KTx, donor type. The entire propensity score model is depicted Supplementary Table S5.

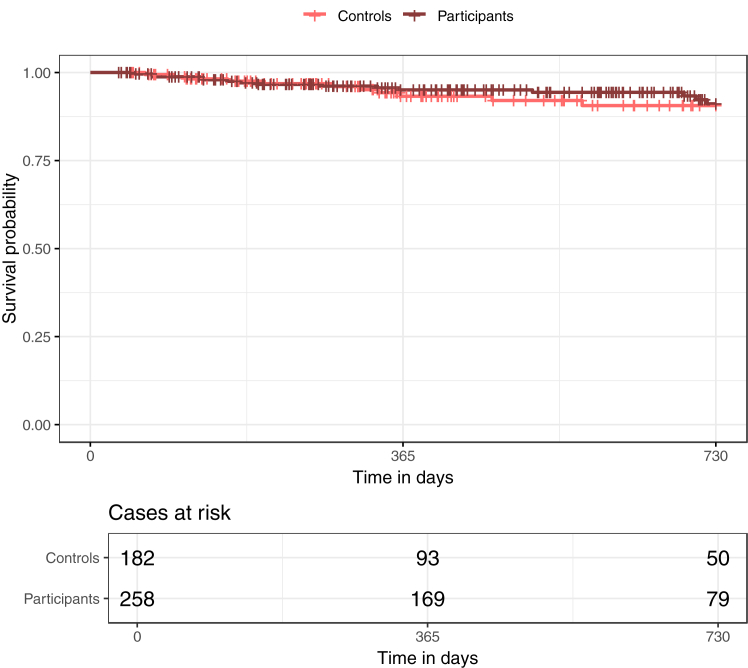

Kaplan Meier curves for graft failure using unweighted data are shown in Fig. 4, Fig. 5, and Kaplan Meier curves using weighted data are shown in Supplementary Figures S1 and S2.

Fig. 4.

Kaplan Meier curves for graft failure in prevalent patients over the full observation period after kidney transplantation (KTx). The figure shows the Kaplan–Meier curves in prevalent patients for participants and controls for the full observation period after KTx. There is a clear difference in graft failure between the two groups, with fewer graft failures in participants compared to controls.

Fig. 5.

Kaplan Meier curves for graft failure in incident patients in the first two years after kidney transplantation (KTx). The figure shows the Kaplan–Meier curves in incident patients for participants and controls for the first two years after KTx. There is no difference in graft failure between the two groups.

Discussion

To our knowledge the KTx360°-study is the first prospective study program to provide systematic assessments followed by individualized interventions in kidney transplant recipients. The combined interventions of our multimodal and multidisciplinary aftercare program KTx360° suggests that they are effective in reducing graft failure in patients in the longer term after KTx.

In the last 20–30 years short-term graft survival has improved very little, and long-term patient and graft survival have improved only gradually despite many advances in immunodiagnostics and immunosuppression.4 During the observation period of this study, graft failure rates of incident participants (5.8%) and controls (6%) were in a comparable range to rates reported in the literature.19, 20, 21, 22 However, since our main aim was to examine the effectiveness of the KTX360° intervention, we had to match participants with controls and to focus on a defined observation period in order to avoid selection biases and selective survival. This procedure impedes the comparability of our graft and patient survival rates with cohort studies.

Overall, improvement of kidney graft survival in the last decades occurred primarily in the short term after transplantation and to a lesser extent in the long term despite many advances in immunodiagnostics and immunosuppression.23 During the first year after transplantation, most graft losses are due to technical issues and vascular complications, followed by acute rejection and glomerulonephritis. Additionally, during the first year patients are generally followed closely at a transplant centre. It can be assumed that during this time the effect of an intervention such as KTx360° has less immediate impact on graft survival.

Beyond the first year after transplantation, most graft losses are due to chronic rejection, often based on non-adherence. Prevention, early detection and treatment of chronic rejection, infection and other complications are important goals of post-transplant care. The frequency of visits to the transplant centre beyond the first year after transplantation is much less frequent compared to the early phases after transplantation. The significantly lower graft failure rate in the prevalent study participants compared to the controls may thus have been the result of the early detection and treatment of incipient complications and the reduction of maladaptive patient behaviours. It is known that patient adherence to IS decreases over time which may render an intervention such as KTx360° more effective.

It can be assumed that the multimodality of our program, allowing for a more individualized and targeted treatment, led to the observed positive results. KTx360° offered a large variety of interventions from training courses regarding immunosuppressive medication, to personal interventions based on the detection of cognitive impairment, psychosocial distress, concerns regarding medication intake, underlying mental disorders, and individualized sports therapy. In addition, factors specific to the KTx360° program, such as regular and reliable contact with a case manager and blended care using video conferences, might also have accounted for the favourable effects. In a single-centre proof-of-concept trial, case management with telemedicine support, and case management alone, improved adherence and reduced hospitalizations after KTx.24 Others have shown that remotely monitored interventions on their own can increase physical activity after transplantation.25

It is therefore valid to speculate that our combined approach might also lead to even more sustainable achievements for incident participants in the long run that could not be shown here because of the short observation period in the study. An analysis of 5-year data in both cohorts is planned.

Additionally, it is reasonable to hypothesize that the package of multicomponent interventions of KTx360° will reduce long-term healthcare costs, especially by reducing the need for dialysis. Eliminating one year of haemodialysis for one patient (approx. 43.000 € in Germany) could finance the KTx360° program for 33 patients over one year (1.300€ per pt./year).

When planning KTx360°, an open study design with the use of claims data to assess study endpoints and with the use of propensity score weighted control groups was chosen. Due to specifications of the funding agency, a randomized controlled design, which is considered the gold standard for therapeutic clinical trials,26 could not be used and a cluster-randomized design was not feasible due to the low number of participating centres in our study. However, claims data are increasingly used to support clinical trials. Claims data have the advantage that they reflect the performance of a trial in the real-world setting.

The quasi-experimental design does not allow for causal attributions of effects, in particular, regarding longitudinal changes without control conditions. However, we could show very low graft loss rates as compared to other published studies. Our selectivity analyses showed some differences between study participants and non-participants as well as the entire group of participants and the subgroup of subjects who were included in the analyses. Thus, we cannot exclude the introduction of a selection bias. However, the clinical relevance of these differences appears small without a strong positive or negative selection bias of subjects in the analysis samples. Furthermore, analyses of claims data provided the opportunity to build a control group via propensity score adjustment, with relevant covariates resulting in a comparison of similar patients in the intervention and the control groups. However, other potentially important covariates might be missing because they are not included in the claims data, i.e. socio-economic status, education, or immunosuppression regimen. In these analyses, survival selectivity due to study participations was also minimized as participants and controls were only analyzed if there was no graft failure in the first 30 days after KTx in the incident group and no graft failure until July 1st 2018 (end of recruitment period) in the prevalent group.

We could also demonstrate that the implementation of the intervention is easy and feasible in different transplant centres and locations, while for interventions in randomized controlled trials the translation to real-world settings is often unsuccessful.27

With the multicomponent aftercare treatment KTx360°, graft survival in prevalent study participants was significantly improved compared to propensity score matched controls. In incident study participants the event rate in the observation period was too small to draw any conclusions. It seems legitimate to hypothesize that the positive effects shown in the prevalent group would also lead to improvement in long-term patient and graft survival in the incident group.

Contributors

MS, LP, MDZ and UT developed the concept of the study and were responsible for funding acquisition. JW and HDN were responsible for the methodology. RG, JW and HDN were responsible for project administration, data curation, and validation. MDZ, MN, FK, EKTT, ML, JP YE, UT, AA, HB and HK were involved in clinical investigation. HDN, JW, JT, IK, OG and PL conducted the formal analysis and visualization. MS, LP and MDZ wrote the original draft with support from JW and OG.

All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and accept responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. LP takes responsibility for the overall content as guarantor. He accepts full responsibility for the finished work and the conduct of the study. JW, HDN and JT have verified the underlying data.

Data sharing statement

Qualifying researchers who wish to access our data should submit a proposal with a valid research question to the corresponding author. Proposals will be assessed by a committee formed from the trial management group, including senior epidemiological and clinical representatives. Available data collected for the study include de-identified individual participant data and a data dictionary.

Declaration of interests

All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Acknowledgements

We thank the other members of the KTx360° Study group10 (Petra Anders, Maximilian Bauer-Hohmann, Johanna Boyen, Andrea Dehn-Hindenberg, Jan Falkenstern, Judith Kleemann, Dieter Haffner, Melanie Hartleib-Otto, Hermann Haller, Nils Hellrung, Nele K Kanzelmeyer, Christian Lerch, Anna–Lena Mazhari, Martina Meiβmer, Regine Pfeiffer, Sandra Reber, Stefanie Schelper, Marit Wenzel) for their continuous support. Finally, we greatly appreciate the willingness of patients to participate in our study. Without them KTx360° would not have been possible.

We thank Felicity Kay for proofreading.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102652.

Contributor Information

Lars Pape, Email: Lars.Pape@uk-essen.de.

KTx360°-Study Group:

Petra Anders, Maximilian Bauer-Hohmann, Johanna Boyen, Andrea Dehn-Hindenberg, Michaela Frömel, Jan Falkenstern, Judith Kleemann, Dieter Haffner, Melanie Hartleib-Otto, Hermann Haller, Nils Hellrung, Nele Kanzelmeyer, Christian Lerch, Anna-Lena Mazhari, Martina Meißmer, Regine Pfeiffer, Sandra Reber, Stefanie Schelper, and Marit Wenzel

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Wolfe R.A., Ashby V.B., Milford E.L., et al. Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(23):1725–1730. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912023412303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hariharan S., Johnson C.P., Bresnahan B.A., Taranto S.E., McIntosh M.J., Stablein D. Improved graft survival after renal transplantation in the United States, 1988 to 1996. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(9):605–612. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003023420901. MJBA-420901 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kasiske B.L. Cardiovascular disease after renal transplantation. Semin Nephrol. 2000;20(2):176–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hariharan S., Israni A.K., Danovitch G. Long-term survival after kidney transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(8):729–743. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra2014530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ying T., Shi B., Kelly P.J., Pilmore H., Clayton P.A., Chadban S.J. Death after kidney transplantation: an analysis by era and time post-transplant. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31(12):2887–2899. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020050566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stoumpos S., Jardine A.G., Mark P.B. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality after kidney transplantation. Transpl Int. 2015;28(1):10–21. doi: 10.1111/tri.12413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marcum Z.A., Handler S.M. Medication nonadherence: a diagnosable and treatable medical condition. JAMA. 2013;309(20):2105–2106. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.4638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pita-Fernandez S., Pertega-Diaz S., Valdes-Canedo F., et al. Incidence of cardiovascular events after kidney transplantation and cardiovascular risk scores: study protocol. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2011;11:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-11-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masiero L., Puoti F., Bellis L., et al. Physical activity and renal function in the Italian kidney transplant population. Ren Fail. 2020;42(1):1192–1204. doi: 10.1080/0886022X.2020.1847723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cherukuri A., Mehta R., Sharma A., et al. Post-transplant donor specific antibody is associated with poor kidney transplant outcomes only when combined with both T-cell-mediated rejection and non-adherence. Kidney Int. 2019;96(1):202–213. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2019.01.033. [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dew M.A., DiMartini A.F., De Vito Dabbs A., et al. Rates and risk factors for nonadherence to the medical regimen after adult solid organ transplantation. Transplantation. 2007;83(7):858–873. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000258599.65257.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohamed M., Soliman K., Pullalarevu R., et al. Non-adherence to appointments is a strong predictor of medication non-adherence and outcomes in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Med Sci. 2021;362(4):381–386. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2021.05.011. S0002-9629(21)00181-6 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bryan Burton B., Jesilov P. How healthcare studies use claims data. Open Health Serv Pol J. 2011;4:26–29. doi: 10.2174/1874924001104010026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neubauer S., Kreis K., Klora M., Zeidler J. Access, use, and challenges of claims data analyses in Germany. Eur J Health Econ. 2017;18(5):533–536. doi: 10.1007/s10198-016-0849-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gulmez R., Ozbey D., Agbas A., et al. Humoral and cellular immune response to SARS-CoV-2 mRNA BNT162b2 vaccine in pediatric kidney transplant recipients compared with dialysis patients and healthy children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2022:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00467-022-05813-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pape L., de Zwaan M., Tegtbur U., et al. The KTx360-study: a multicenter, multisectoral, multimodal, telemedicine-based follow-up care model to improve care and reduce health-care costs after kidney transplantation in children and adults. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:587. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2545-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kreis K., Neubauer S., Klora M., Lange A., Zeidler J. Status and perspectives of claims data analyses in Germany-A systematic review. Health Pol. 2016;120(2):213–226. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nohre M., Bauer-Hohmann M., Klewitz F., et al. Prevalence and correlates of cognitive impairment in kidney transplant patients using the DemTect-results of a KTx360 substudy. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:791. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vincenti F., Rostaing L., Grinyo J., et al. Belatacept and long-term outcomes in kidney transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):333–343. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vincenti F., Charpentier B., Vanrenterghem Y., et al. A phase III study of belatacept-based immunosuppression regimens versus cyclosporine in renal transplant recipients (BENEFIT study) Am J Transplant. 2010;10(3):535–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.03005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ekberg H., Bernasconi C., Tedesco-Silva H., et al. Calcineurin inhibitor minimization in the Symphony study: observational results 3 years after transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(8):1876–1885. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ekberg H., Tedesco-Silva H., Demirbas A., et al. Reduced exposure to calcineurin inhibitors in renal transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(25):2562–2575. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coemans M., Süsal C., Döhler B., et al. Analyses of the short- and long-term graft survival after kidney transplantation in Europe between 1986 and 2015. Kidney Int. 2018;94(5):964–973. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2018.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmid A., Hils S., Kramer-Zucker A., et al. Telemedically supported case management of living-donor renal transplant recipients to optimize routine evidence-based aftercare: a single-center randomized controlled trial. Am J Transplant. 2017;17(6):1594–1605. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Serper M., Barankay I., Chadha S., et al. A randomized, controlled, behavioral intervention to promote walking after abdominal organ transplantation: results from the LIFT study. Transpl Int. 2020;33(6):632–643. doi: 10.1111/tri.13570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bothwell L.E., Greene J.A., Podolsky S.H., Jones D.S. Assessing the gold standard--lessons from the history of RCTs. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(22):2175–2181. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms1604593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kostalova B., Ribaut J., Dobbels F., et al. Medication adherence interventions in transplantation lack information on how to implement findings from randomized controlled trials in real-world settings: a systematic review. Transplant Rev. 2021;36(1) doi: 10.1016/j.trre.2021.100671. S0955-470X(21)00077-X [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.