INTRODUCTION

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a major global public health challenge, impacting millions and leading to a spectrum of health outcomes, with alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD) being among the most severe. Recent studies highlight increased advanced fibrosis in alcohol-associated fatty liver disease1 and hospitalizations from acute alcohol-associated hepatitis.2 Addressing AUD in individuals with ALD can both prevent disease progression and reduce the risk of alcohol-associated death.

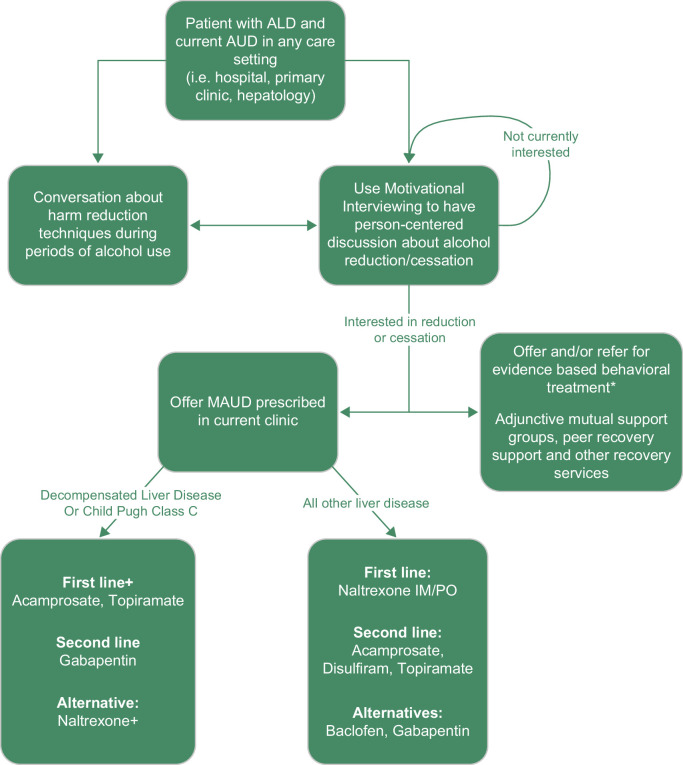

Behavioral interventions and medications for alcohol use disorder (MAUD) are highly effective yet underutilized. There are also large racial and ethnic disparities in the provision of AUD treatment, with minoritized groups less likely to receive evidence-based treatment.3 Both MAUD and behavioral interventions can support individuals’ efforts to reduce or stop alcohol use, which provides significant health benefits. In this review, we summarize behavioral and medication treatments for AUD in individuals with ALD and how to integrate these treatments into clinical practice (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Decision tree for patients with ALD and AUD. *Behavioral Treatment is ideally offered as part of multidisciplinary care within the clinic. + Consider naltrexone as a first-line treatment for individuals with decompensated liver disease if the benefits outweigh the risks. ^Due to the risk of medication-induced hepatitis, including fulminant liver injury, disulfiram can be offered to carefully selected patients with Child-Pugh Class A ALD cirrhosis after a risk-benefit discussion. Abbreviations: ALD, alcohol-associated liver disease; AUD, alcohol use disorder; MAUD, medications for alcohol use disorder.

Individualizing care

After confirming a diagnosis of AUD, the first step is to engage in supportive, nonjudgmental discussion to better understand the individual’s goals regarding their alcohol use and health. Motivational interviewing (MI) is an evidence-based, patient-centered strategy that facilitates relationship building, helps identify each individual’s unique motivations and goals, and fosters the development of a collaborative plan that is self-management and recovery training.4 Key elements of MI include open-ended questions, affirmations, reflective listening, and summarizing. Layering a framework of cultural humility acknowledging the diverse backgrounds, values, and beliefs of each individual can promote open dialog.

While abstinence remains the safest goal in individuals with severe AUD and ALD, any reduction in alcohol use can confer considerable benefit (Table 1). Nonabstinent alcohol reduction is sustainable, improves health and quality of life, and may better align with some individuals’ goals. For all individuals who use alcohol, harm reduction counseling should be offered. Harm reduction includes education to reduce harms from alcohol use, like making plans to avoid intoxicated driving, ensuring nutrition and hydration, defining environmental supports, and providing strategies to minimize withdrawal risk.

TABLE 1.

Myths and misconceptions about AUD and ALD

| Myth | Truth |

|---|---|

| If a person isn’t interested in abstinence, treatment for AUD is not indicated | Data support nonabstinent reductions in alcohol to reduce mortality, improve quality of life, and be sustainable in people with AUD. Data on ALD are currently lacking |

| Naltrexone is not safe in ALD | Evidence shows the safety and effectiveness of naltrexone, including reductions in mortality, even in those with cirrhosis. In decompensated cirrhosis, a risk-benefit discussion should precede starting it understanding the risk of continued alcohol use on the liver |

| Treating AUD, especially in the setting of ALD, requires an addiction specialist | Treatment of AUD and ALD is within the skillset of all clinicians. There are no additional certifications or training needed to prescribe any form of MAUD. All treatments, including behavioral treatment can be integrated into medical care |

| Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) is the most evidence-based form of behavioral treatment for AUD | While mutual support groups such as AA can serve as an accessible and useful adjunct to care, other behavioral treatments have robust evidence in the treatment of AUD. These include cognitive behavioral therapy, motivation enhancement therapy, and twelve-step facilitation |

| Hospitalization is not an appropriate time to address AUD. People need to prove they are motivated to engage in treatment before starting MAUD | Acute illness and hospitalization can serve as a particularly high-impact time to address chronic diseases like AUD and ALD. Evidence-based care such as MAUD should be offered and started in all clinical settings, including the hospital |

Abbreviations: AA, Alcoholics Anonymous; ALD, alcohol-associated liver disease; AUD, alcohol use disorder; MAUD, medications for alcohol use disorder.

Medications for alcohol use disorder

MAUD is an essential component of AUD treatment and should be offered to all individuals with AUD, particularly those with ALD. There are 3 Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved MAUD: acamprosate, disulfiram, and naltrexone.5 Non-FDA–approved medications with evidence of their effectiveness are topiramate, gabapentin, and baclofen.5 MAUD has been shown to reduce alcohol use,5 progression of ALD, and mortality.6 Prescribing and counseling patients about MAUD is within the skillset of all clinicians.

Table 2 provides an overview of MAUD, including FDA approval, dosing, and ALD considerations.

TABLE 2.

Medications for alcohol use disorder options in alcohol-associated liver diseasea

| Medication | FDA approved? | Dose | Hepatic considerations | Additional considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acamprosate | Yes | 666 mg 3 times daily | Included in study showing the mortality benefit of MAUD in ALD | Dose reduction in renal impairment High pull burden |

| Disulfiram | Yes | 250 mg daily Can increase to 500 mg daily |

Risk of acute hepatitis Generally, avoid in individuals with Child-Pugh Class B and C ALD |

Most supportive data in observed treatment (network therapy)—can partner with a caregiver/companion Avoid in unstable cardiac disease |

| Naltrexone | Yes | 50 mg PO daily OR 380 mg IM monthly |

Safe in most liver disease including cirrhosis (Child-Pugh A and B). Historical concern about hepatotoxicity overestimated. In Child-Pugh C cirrhosis have risk/benefit discussion |

Consider partnering with support person for observed treatment (network therapy) if using the oral formulation Avoid in individuals prescribed opioids |

| Topiramate | No | Start—25 mg daily Goal—200–300 mg daily in divided doses |

Avoid if HE due to potential cognitive impact | Requires slow up-titration Dose reduction in renal impairment |

| Gabapentin | No | Start—300 mg daily Goal—600–900 mg 3 times daily |

Avoid if HE due to potential cognitive impact | Can also be used to treat mild or moderate alcohol withdrawal syndrome and peripheral neuropathy related to alcohol Dose reduction with renal impairment |

| Baclofen | No | Start—5 mg 3 times daily Goal—10 mg 3 times daily |

Avoid if HE due to potential cognitive impact Data not robust but existing positive data specific to ALD |

Life-threatening withdrawal syndrome |

Treatments can be combined, if needed for additional effect.

Abbreviations: ALD, alcohol-associated liver disease; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; HE, hepatic encephalopathy; MAUD, medications for alcohol use disorder.

Naltrexone, available as both a once-daily oral pill and monthly intramuscular injection, is the first-line for the treatment of AUD due to its robust data for reducing the return to drinking, heavy drinking, and drinking days.5 Historically, it has been avoided in people with ALD due to concerns about its hepatic metabolism; however, multiple studies support its safety in ALD, including decompensated ALD.7 For individuals with decompensated ALD (Child-Pugh Class C), the small risk of medication-induced hepatitis should be weighed against the potential benefit of alcohol cessation. Individuals currently prescribed opioid agonists, including those with opioid use disorder who are prescribed methadone or buprenorphine, should not receive naltrexone because naltrexone is an opioid antagonist.

Acamprosate is often considered the first alternative to naltrexone, particularly in those with a goal of alcohol abstinence, and is generally considered safe for liver disease. Its utility is often limited by large pill burden. Large meta-analyses demonstrate its effectiveness for alcohol abstinence,5 and it has shown mortality benefits in people with ALD.8

Disulfiram can be considered as an alternative treatment in carefully selected patients with Child-Pugh Class A ALD, given the risk of medication-induced hepatitis. It is an aversive treatment causing a negative physical reaction to alcohol use. It can be used as monotherapy or in combination with naltrexone or acamprosate for individuals with a goal of abstinence.

Topiramate, while not FDA-approved for AUD, has robust data and is considered the co-first-line treatment in the most recent Veterans Health Administration/Department of Defense guidelines.9 It is safe in both hepatic and renal impairment, but its use in AUD is limited by the need for slow up-titration to an effective dose and potential cognitive side effects. Cognitive side effects can be minimized by starting this medication at night.

Baclofen is one of the few MAUD studied specifically in people with ALD,10 but its use in AUD lacks sufficient supportive data9 and is limited by side effects, including sedation and risk of a life-threatening withdrawal syndrome.

Gabapentin lacks data specifically in the setting of ALD, and sedative effects may limit its use in those with hepatic encephalopathy.

Any of the above medications can be combined, although data are limited on any additive benefit. Any oral therapies may benefit from the addition of adherence monitoring and medication management (components of “network therapy”). Laboratory monitoring of liver and kidney function is generally not needed but can be monitored based on usual care in those with ALD.

Varenicline and prazosin have limited trial data and remain an area for further exploration. Emerging treatments for AUD include fecal transplant, ketamine, psilocybin, and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors.

Behavioral interventions

Behavioral interventions are valuable components of AUD treatment, though should not be required for individuals to receive MAUD. They can decrease alcohol use and help patients with ALD induce and maintain abstinence (Table 3). They are most effective when combined with MAUD, though it is unclear whether they confer added benefit to standalone MAUD in ALD.11 Of the evidence-based treatments, no behavioral treatments have shown superiority in treating AUD in patients with ALD but may be most effective when combined and offered with comprehensive medical care and MAUD.12 Most behavioral interventions require a professional trained in delivering them, though brief interventions delivered by any member of the inter-professional health care team can be integrated into medical practice.

TABLE 3.

Behavioral interventions

| Intervention | Focus | Outcomes in ALD |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive behavioral therapy | Improve coping skills, identify and modify thought patterns and behaviors that promote alcohol use. Some techniques include urge surfing, decisional delay, use logs, behavioral chain analysis, deep breathing, and daily affirmations | Reduced alcohol use, increased abstinence More efficacious when combined with MAUD and medical care |

| Motivational enhancement therapy | Enhance motivation to stop drinking, often by identifying and relating to personal values | Reduced alcohol use, increased maintenance of abstinence More efficacious when combined with CBT |

| Twelve-step facilitation | Facilitate mutual support group involvement (eg, Alcoholics Anonymous, SMART Recovery) | Increases continuous abstinence Equally efficacious to CBT and MET |

| Mutual support | Self-help organization (eg, Alcoholics Anonymous, SMART Recovery), promote social connectedness, share experience, personal responsibility | Limited data, but highly accessible and widely utilized Promotes social connectedness |

| Peer support | Mentorship and coaching, connection to resources, community building | Promotes social and recreational skills and sense of belonging Facilitates resource connections that can improve patient retention in treatment |

Abbreviations: ALD, alcohol-associated liver disease; CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; MAUD, medications for alcohol use disorder; MET, motivational enhancement therapy; SMART, self-management and recovery training.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is effective in reducing alcohol use and increasing abstinence in patients with ALD. It improves coping skills by helping individuals identify and modify thought patterns and behaviors that facilitate alcohol use. It is especially effective when combined with other therapies and comprehensive medical care.12 Clinicians can deliver brief skills-based CBT interventions such as relaxation strategies, behavioral activation, and return-to-use prevention in their clinics.

MI is a person-centered, collaborative interviewing approach that helps build internal motivation and can be utilized by any clinician. Motivational enhancement therapy builds on MI as an assessment-focused form of treatment. Motivational enhancement therapy has been shown to reduce alcohol use13 and assist with ongoing abstinence for individuals with ALD.12 It may be more effective at inducing abstinence when combined with CBT.12

Twelve-step facilitation is a manualized, step-wise program through which a trained therapist facilitates a person’s active involvement in mutual support groups. It is particularly effective at improving ongoing abstinence and has comparable effectiveness to CBT and motivational enhancement therapy in patients with ALD.14

Mutual support, including but not limited to Alcoholics Anonymous, Self-Management and Recovery Training (SMART), Celebrate Recovery, Refuge Recovery, Women for Sobriety, She Recovers, and others, are the most common form of peer recovery support for AUD. There is limited data on their effectiveness, but their accessibility and promotion of social connectedness make them useful for many individuals engaged in or contemplating recovery from AUD. Other recovery supports include peer recovery support services that work to provide emotional, informational, instrumental, and affiliation support through peer mentoring, skills training, concrete assistance like childcare and transportation, and community building, among others.15

Models of care

Hospitalizations resulting from ALD provide crucial opportunities for diagnosing and initiating treatment for AUD. These opportunities can be significantly enhanced when health care facilities leverage addiction consult services to provide evidence-based treatment of AUD and linkage to subsequent care. The importance of continued care posthospitalization cannot be overstated.

The prevailing outpatient model of care, known as the concomitant care model, involves patients seeking care from specialists such as hepatologists and addiction specialists independently. Regrettably, this approach encounters obstacles such as stigma, transportation difficulties, and uncertainty regarding where to receive treatment, which can impede engagement in treatment.

To enhance patient engagement in AUD treatment, various integrated treatment strategies have been studied. One approach incorporates AUD treatment into primary care settings, yielding positive outcomes such as increased AUD diagnoses and higher use of MAUD.16 This approach also has the potential to improve racial and ethnic disparities in AUD treatment by broadening access to evidence-based care.3 Nevertheless, this approach has not demonstrated significant success in boosting the frequency of addiction-focused primary care visits.16 One potential explanation for this limited success is that primary care clinicians often feel uncomfortable managing AUD on their own. This same discomfort is observed among hepatologists. Consequently, there is a growing need to enhance addiction education for all health care professionals.

An alternative solution that has shown promise is the co-location of addiction specialists with primary care or hepatology. This approach is both feasible and effective and leads to increased abstinence and decreased mortality.17 Where not currently possible, warm handoffs to known and trusted evidence-based addiction care have the potential to improve engagement.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Effective treatment of AUD and ALD includes MAUD and behavioral interventions. Ensuring access to and initiating evidence-based treatment is within the scope of all clinicians and is particularly critical for primary care physicians, gastroenterologists, and hepatologists.

Acknowledgments

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts to report.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AUD, alcohol use disorder; ALD, alcohol-associated liver disease; AFLD, alcohol fatty liver disease; CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; MAUD, medications for alcohol use disorder; MI, motivational interviewing.

Contributor Information

Gordon S. Hill, Email: gordon.hill@yale.edu.

Shawn M. Cohen, Email: shawn.cohen@yale.edu.

Melissa B. Weimer, Email: melissa.weimer@yale.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wong T, Dang K, Ladhani S, Singal AK, Wong RJ. Prevalence of alcoholic fatty liver disease among adults in the United States, 2001-2016. Jama. 2019;321:1723–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jinjuvadia R, Liangpunsakul S. Trends in alcoholic hepatitis-related hospitalizations, financial burden, and mortality in the United States. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49:506–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mulia N, Tam TW, Schmidt LA. Disparities in the use and quality of alcohol treatment services and some proposed solutions to narrow the gap. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65:626–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change, 2nd ed. The Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 5. McPheeters M, O’Connor EA, Riley S, Kennedy SM, Voisin C, Kuznacic K, et al. Pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2023;330:1653–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vannier AGL, Shay JES, Fomin V, Patel SJ, Schaefer E, Goodman RP, et al. Incidence and progression of alcohol-associated liver disease after medical therapy for alcohol use disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2213014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ayyala D, Bottyan T, Tien C, Pimienta M, Yoo J, Stager K, et al. Naltrexone for alcohol use disorder: Hepatic safety in patients with and without liver disease. Hepatol Commun. 2022;6:3433–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rabiee A, Mahmud N, Falker C, Garcia-Tsao G, Taddei T, Kaplan DE. Medications for alcohol use disorder improve survival in patients with hazardous drinking and alcohol-associated cirrhosis. Hepatol Commun. 2023;7:e0093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Perry C, Liberto J, Milliken C, Burden J, Hagedorn H, Atkinson T, et al. The management of substance use disorders: Synopsis of the 2021 U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and U.S. Department of Defense Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175:720–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Addolorato G, Leggio L, Ferrulli A, Cardone S, Vonghia L, Mirijello A, et al. Effectiveness and safety of baclofen for maintenance of alcohol abstinence in alcohol-dependent patients with liver cirrhosis: randomised, double-blind controlled study. Lancet. 2007;370:1915–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rogal S, Youk A, Zhang H, Gellad WF, Fine MJ, Good CB, et al. Impact of alcohol use disorder treatment on clinical outcomes among patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2020;71:2080–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Khan A, Tansel A, White DL, Kayani WT, Bano S, Lindsay J, et al. Efficacy of psychosocial interventions in inducing and maintaining alcohol abstinence in patients with chronic liver disease: A systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:191–202.e1-4; quiz e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Weinrieb RM, Van Horn DH, Lynch KG, Lucey MR. A randomized, controlled study of treatment for alcohol dependence in patients awaiting liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2011;17:539–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kelly JF, Humphreys K, Ferri M. Alcoholics Anonymous and other 12-step programs for alcohol use disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;3:Cd012880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. White WM. Peer-based addiction recovery support: History, theory, practice, and scientific evaluation executive summary. Counselor. 2009;10:54–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee AK, Bobb JF, Richards JE, Achtmeyer CE, Ludman E, Oliver M, et al. Integrating alcohol-related prevention and treatment into primary care: A cluster randomized implementation trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2023;183:319–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Elfeki MA, Abdallah MA, Leggio L, Singal AK. Simultaneous management of alcohol use disorder and liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Addict Med. 2023;17:e119–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]