Dorothy Porter

Routledge, £16.99, pp 376

ISBN 0 415 20036 9

———————

Rating: ★★★

How boring is the history of public health? As Dorothy Porter notes in her introduction, the subject tends to provoke a big yawn, both from students, who are bored by accounts of bureaucratic and technological reforms, and from historians, who are bored by the usual grand narrative of progress. Because historians don’t write these histories any longer, George Rosen’s A History of Public Health, originally published in 1958, is still widely used and recently reappeared in an updated and expanded version.

But here we are, faced with a new history of public health “from ancient to modern times” written by a modern historian. Porter acknowledges the “contemporary intellectual climate of postmodernist relativism” and apologises for her grand narrative of only the Western tradition in public health but then makes a serious attempt at telling “the history of collective action in relation to the health of populations.” Her history is not only remarkably contemporary but also very international. Its emphasis is on tracing the origins of our current thinking about the role of the state, and it is precisely in this area that the idea of a linear progression towards ever more effective public health action is indeed untenable.

This is clearly illustrated by the recent history of state intervention in the provision of welfare, and is one of the main themes of the book. In most industrial societies state intervention started in the early years of the century and increased until the mid-1970s. A detailed account of the history of welfare provision in Germany, France, Britain, and Sweden shows that, under the surface of widely different political events and ideological discourses, all European countries were moved by the same collectivist tendencies. European states instituted comprehensive welfare systems in the belief that universal welfare provision would turn public protection into citizenship for everyone. After the second world war, the expansion of the welfare state was facilitated by economic growth and by the then widespread belief that welfare provision would stimulate economic growth by making the labour force healthier, better educated, and more mobile.

This progression was interrupted around 1980, as some of the criticisms of the welfare state which had prevented the United States from adopting comprehensive welfare systems became increasingly popular around the world. The economic crisis necessitated cuts in public spending, and the example of Japan suggested that competitive economies were incompatible with large public sectors. Universalism was accused of failing to discriminate in favour of those in greatest need and of creating a culture of dependency. Radical reforms were advocated, but, although some important changes occurred everywhere, there was usually a large gap between political rhetoric and practical policies because of the popularity of the welfare state among the middle classes. The largely unsuccessful attacks by the Thatcher government on the NHS serve as a striking illustration.

This book is far from easy reading, burdened as it is with abstractions and references, with details of political events, and names of protagonists. It does not replace George Rosen’s old fashioned history of technological advances because one will look in vain for a disease-specific account of the achievements of public health. It will even be boring for students, but it is an absolutely fascinating book. The issues raised are timely and unsettling, largely unaddressed as they are by contemporary public health professionals. The rise of the public health profession is closely linked to the process of increased state intervention in all spheres of life, and the implications of the recent changes in dominant ideology for the practice of public health have yet to be thoroughly analysed.

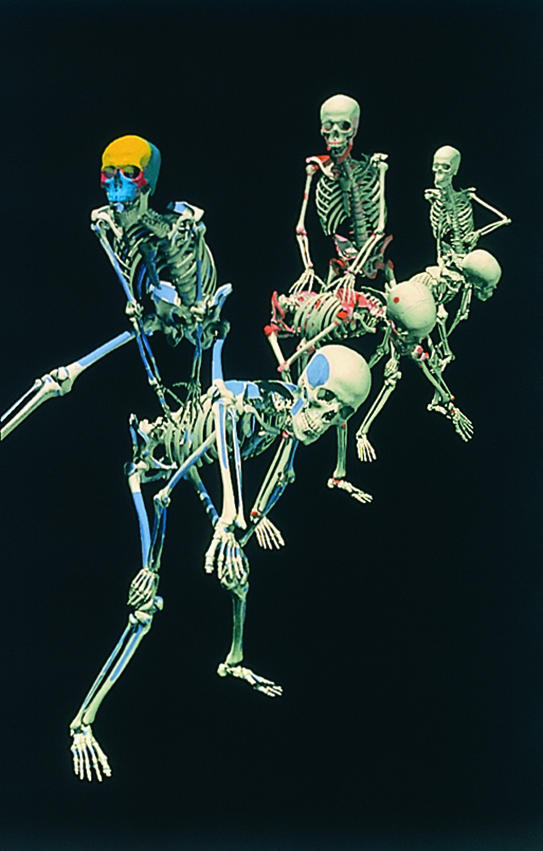

Figure.

The Interactive Skeleton. A 3D screen image on display at The New Anatomists exhibition at the Wellcome Trust’s Two10 Gallery, 210 Euston Road, London NW1 2BE which runs until 16 July