Highlights

-

•

Development of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against H1N1 HA shows high binding and broad-spectrum neutralizing activity against vaccine strains of H1N1pdm09 viruses.

-

•

Antibody 2B2 has demonstrated effective prevention and treatment outcomes against infections caused by various H1N1 strains in mice models.

-

•

Identification of key escape mutations in the HA under selection pressure of mAbs emphasizes the importance of continuous surveillance and adaptive antibody design.

Keywords: Escape mutant, Hemagglutinin, Influenza, Monoclonal antibody, Neutralization

Abstract

H1N1 influenza virus is a significant global public health concern. Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) targeting specific viral proteins such as hemagglutinin (HA) have become an important therapeutic strategy, offering highly specific targeting to block viral transmission and infection. This study focused on the development of mAbs targeting HA of the A/Victoria/2570/2019 (H1N1pdm09, VIC-19) strain by utilizing hybridoma technology to produce two mAbs with high binding capacity. Notably, mAb 2B2 has demonstrated a strong affinity for HA proteins in recent H1N1 influenza vaccine strains. In vitro assessments showed that both mAbs exhibited broad-spectrum hemagglutination inhibition and potent neutralizing effects against various vaccine strains of H1N1pdm09 viruses. 2B2 was also effective in animal models, offering both preventive and therapeutic protection against infections caused by recent H1N1 strains, highlighting its potential for clinical application. By individually co-cultivating each of the aforementioned mAbs with the virus in chicken embryos, four amino acid substitution sites in HA (H138Q, G140R, A141E/V, and D187E) were identified in escape mutants, three in the antigenic site Ca2, and one in Sb. The identification of such mutations is pivotal, as it compels further investigation into how these alterations could undermine the binding efficacy and neutralization capacity of antibodies, thereby impacting the design and optimization of mAb therapies and influenza vaccines. This research highlights the necessity for continuous exploration into the dynamic interaction between viral evolution and antibody response, which is vital for the formulation of robust therapeutic and preventive strategies against influenza.

1. Introduction

Seasonal influenza is an acute respiratory disease caused by influenza viruses that has triggered widespread pandemics, resulting in significant loss of life (Iuliano et al., 2018). Influenza viruses belong to the Orthomyxoviridae family and have a negative-sense, single-stranded, segmented RNA genome. Different combinations of hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) on the surface of influenza A virus particles define different subtypes (Petrova and Russell, 2018; Tong et al., 2013). The H1N1 influenza virus is a subtype of the influenza A virus that affects humans and animals. The H1N1 influenza virus has historically triggered several widespread flu pandemics, including the 1918 Spanish Flu, which resulted in approximately 50 million deaths (Johnson and Mueller, 2002); and the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, which caused an estimated 123,000 to 203,000 fatalities (Simonsen et al., 2013). The influenza virus undergoes genetic variation through antigenic drift and shift, allowing it to evade recognition by the human immune system, enhancing its potential to cause influenza pandemics (Fitch et al., 1997; Kim et al., 2018). The 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic was caused by a novel strain formed through viral evolution and cross-species transmission between humans, birds, and pigs (Dawood et al., 2009, Garten et al., 2009, Smith et al., 2009, Vijaykrishna et al., 2010).

The HA protein is pivotal for influenza viruses to recognize host cell receptors, enter cells, and facilitate viral invasion, infection, and immune evasion. Therefore, understanding the structure and function of HA proteins is essential for designing effective vaccines and treatment methods. The application of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) has shown great potential in this regard, demonstrating high specificity, sensitivity, and accuracy in the diagnosis and treatment of viral infections (Jin et al., 2017; Tan et al., 2015), as well as playing an important role in exploring antigenic epitopes of the HA protein and understanding its evolutionary mechanisms.

The head region of the H1N1 HA protein contains five major antigenic sites: Ca1, Ca2, Cb, Sa, and Sb (Gerhard et al., 1981; Gerhard and Webster, 1978; Laver et al., 1979). Antigenic epitopes are critical for determining antigen specificity, making the study of key amino acid positions within these epitopes crucial for vaccine design and the development of therapeutic drugs (Liu et al., 2018).

In this study, we prepared two mAbs targeting the H1N1 HA protein and analyzed its antigenic epitopes of H1N1 HA, providing a scientific basis for influenza vaccine research.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Vaccines, viruses and cells

The influenza vaccine and influenza vaccine strains were donated by Zhejiang Tianyuan Bio-Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. The primary vaccine, a split virion inactivated formulation, had a concentration of 140 μg/ml of VIC-19 HA and was stored at 4 °C. The influenza vaccine variants included A/Brisbane/59/2007 (Seasonal H1N1, BR-07), A/California/07/2009 (H1N1pdm09, CA-09), A/Michigan/45/2015 (H1N1pdm09, MIC-15), and A/Guangdong-Maonan/SWL1536/2019 (H1N1pdm09, GD-19) (Yang et al., 2022a). The mouse-adapted strains M-MIC-15 and M-GD-19 were generated by serial passaging of the virus in mouse lungs.

Madin-Darby Canine Kidney (MDCK) cells were maintained in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 100 units/ml penicillin-streptomycin mixture (Pen-Strep), incubated at a temperature of 37 °C. After being infected with influenza virus, MDCK cells were maintained in the virus dilution solution (DMEM supplemented with 1 % bovine serum albumin [BSA], 100 units/ml Pen-Strep, 2 μg/mL TPCK-trypsin).

2.2. Preparation of mAbs

Preparation of mAbs using the hybridoma technology. Initially, BALB/c mice were immunized with split virion VIC-19 HA vaccine mixed with Quick Antibody-Mouse 5 W adjuvant to stimulate an immune response. Following booster injections, splenocytes from immunized mice were harvested and fused with myeloma cells using polyethylene glycol (PEG) (Wang et al., 2022), Hybridoma colonies producing specific mAbs were identified by ELISA (Section 2.3). The selected clones were further isolated by limiting dilution cloning to ensure monoclonality. The mAbs were then purified and stored at –80 °C for future use.

2.3. ELISA

ELISA plates were coated with 20 ng per well HA protein (Sino Biological Inc.) and incubated for 16 h at 4 °C. The plates were then washed with phosphate buffered saline with Tween-20 (PBST), blocked for 2 h at 25 °C, and washed again. Antibodies, diluted from 10.00 to 0.01 μg/mL in PBS, were added in duplicates. Controls included blank (PBS), negative (normal mouse serum), and positive (immunized mouse serum). After incubation for 2 h at 25 ℃, HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (goat origin) was added at 1:6000 in PBST for 1 h. After washing, 3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate was added for 3 min in the dark, the reaction was stopped, and the optical density (OD) was measured at 450 nm. A P/N OD ratio ≥ 2.1 indicated HA protein's presence and immunogenicity.

2.4. Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) assay

SPR was performed using a Biacore instrument (GE Healthcare) (Cao et al., 2020). The mAbs were immobilized onto CM5 chips through direct amine coupling to achieve a target immobilization level of 50 Response Units (RU). The experiment was performed in the Kinetics/Affinity mode, with each HA protein (Sino Biological Inc.) derived from the H1N1pdm09 virus strains CA-09, MIC-15, BR-18, GD-19, VIC-19, and VIC-22 introduced separately as the analyte. Each HA protein was tested at concentration gradients of 0.625, 1.25, 2.5, and 5 μg/mL. The contact phase was set to 180 s, followed by a dissociation phase of 3600 s. The kinetics and affinity parameters, including the association rate (ka), dissociation rate (kd), and affinity constant (kD), were computed using Biacore software.

2.5. Hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) assay

Successive 2-fold dilutions of mAbs or controls, maintained in 25μL, were prepared in 96-well hemagglutination plates. Controls included negative (normal mouse serum), and positive (immunized mouse serum). Each mAb or control was mixed with 25 μL of virus solution containing 4 hemagglutination units (HAU) and incubated at 25 °C for 30 min. This virus concentration was determined by a standard hemagglutination assay. When specific antibodies bind to HA, they hinder the virus-induced agglutination of chicken red blood cells. The HAI titer refers to the reciprocal of the highest dilution of the antibody that inhibits RBC agglutination (World Health Organization, 2011).

2.6. Microneutralization (MN) assay

MDCK cells were seeded at 2 × 104 cells per well in a 96-well plate and incubated at 37 ºC with 5 % CO2 for 24 h (Chen et al., 2014). Antibodies diluted to 100 μg/mL were serially diluted two-fold from the first to the tenth column of a new plate, each well receiving 50 μL. Subsequently, each well was combined with 50 μL of a 200TCID50 virus solution, ensuring a uniform mixture across the plate. The 11th column was used for virus titration, and within the 12th column, the first four wells served as a positive control, receiving 100 μL of the 100TCID50 virus solution, while the last four wells acted as a negative control, each receiving 100 μL of PBS. The plate was incubated at 35 ℃ with 5 % CO2 for 1 h. After washing the MDCK cells with PBS, the virus-antibody mixture, along with the controls, was removed, and virus dilution solution was added to the cells and incubated for 72 h. The supernatant was then analyzed for viral hemagglutination titers using the Reed-Muench method to determine the neutralizing efficacy of the antibody.

2.7. Immunofluorescence assay (IFA)

MDCK cells were seeded in 48-well plates at a density of 4 × 104 cells/well 24 h before infection to achieve approximately 70 % confluence (Wan et al., 2013). The cells were exposed to various H1N1 strains (BR-07, CA-09, MIC-15, and GD-19), each prepared in virus dilution solution, and administered at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.5. Following a 2 h incubation period, the viral supernatant was removed and the cells were washed twice with PBS before the addition of virus dilution solution. After an further 16 h incubation, the cells were washed with PBS. Fixation was achieved using 4 % paraformaldehyde for 30 min at 25 °C, followed by three PBS washes. The cells were then permeabilized with 0.5 % Triton-X100 for 30 min at 25 ℃, followed by another series of three PBS washes. Blocking involved 3 % BSA solution for 1 h at 25 ℃, after which the solution was discarded. The cells were incubated with mAbs (10 μg/mL) overnight at 4 °C, including an irrelevant isotype antibody, for comparison. Following three PBS washes, cells were treated with a fluorescein (FITC)-conjugated secondary antibody (5 μg/mL) and incubated in the dark at 37 °C for 90 min, then washed thrice with PBS. Fluorescence microscopy was used for cell imaging and analysis.

2.8. Prophylactic and therapeutic evaluation of mAbs in mice infected with influenza A viruses

The mice were infected by intranasal inoculation (Wang et al., 2022). Each mouse was inoculated with a dose equivalent to 25 times the 50 % lethal dose (LD50) of the MIC-15 influenza virus. This study involved a group of eleven 6-week-old, healthy female BALB/c mice. The groups were administered doses of either 10 mg/kg or 30 mg/kg of the mAb through intraperitoneal injection, either 6 h before or 6 h after viral infection. After infection, the body weight of five mice from each group were recorded for 14 days. On the 3rd and 6th days post-infection, three mice from the remaining six mice in each group were selected and euthanized by cervical dislocation under anesthesia, and their lungs were harvested in a sterile environment for histopathological analysis.

For a separate experiment, the infection method was the same, with each mouse receiving an inoculation of 50 μL of the GD-19 influenza virus. This group consisted of ten 6-week-old female BALB/c mice. The doses administered were 1, 3, or 10 mg/kg via intraperitoneal injection, either 24 h before or 24 h after viral infection. Preliminary experiments indicated that mice infected with the GD-19 virus did not exhibit significant symptoms, such as weight loss or noticeable lung lesions; hence, only viral load measurements were conducted for this group. On the 3rd and 6th days post-infection, five mice from each group were selected, and their lungs were harvested in a sterile environment for histopathological analysis.

2.9. Escape mutants selection

The mAbs were individually diluted to 1 μg/mL in a volume of 100 μL. Subsequently, 100 μL of influenza virus was added to each mAb solution. These two components were then mixed together, resulting in a final volume of 200 μL. The mixtures were incubated at 25 °C for 1 h and then used to inoculate 10-day-old SPF chicken embryos, with each mixture being used to inoculate one chicken embryo. After 48 h of incubation at 35 °C, allantoic fluid was collected for hemagglutination assays to identify the presence of the virus. The experiment progressed by systematically increasing antibody concentrations (1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, and 64 μg/mL), mixing these with positive allantoic fluid samples, and repeating the incubation and collection process. The HAI assay was then employed to identify escape mutants, characterized by a significant reduction (≥ 8-fold) in inhibition titers compared to the original strain. The identified mutants were sequenced for further analysis (Yang et al., 2022b).

3. Results

3.1. Antibody generation and analysis

Through four rounds of limiting dilution, two hybridoma cell lines that stably secreted mAbs against H1N1 were obtained. These hybridoma cells were cultured for three days in DMEM without FBS, and the supernatants were collected for the detection of mAb subtypes. Both cell lines produced light chains of the κ type, with heavy chains identified as IgG1 and IgG2a, respectively. The sequencing results for the antibody genes in the hybridoma cells are presented in Table 1.

Table. 1.

Sequencing of hybridoma cells secreting mAb targeting VIC-19 HA.

| mAb | Isotype |

Sequencing |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VH gene | VH CDR3 | VL gene | VL CDR3 | ||

| 2B2 | IgG1, κ | IGHV3–2 | SRSRGYFDV | IGKV6–32 | QQDYSSPYT |

| 2F6 | IgG2a, κ | IGHV1–82 | ARIGDYGGPYETMDY | IGKV10–96 | QQGKTLPNT |

3.2. Antibody affinity evaluation

In this study, the binding affinity of the mAbs was assessed using influenza vaccine strains recommended between 2008 and 2021. The strains evaluated included BR-07, recommended from 2008 to 2009, CA-09 recommended from 2009 to 2017, MIC-15 recommended from 2017 to 2019; A/Brisbane/02/2018 (H1N1pdm09, BR-18), recommended from 2019 to 2020, GD-19 recommended from 2020 to 2021, VIC-19 recommended from to 2021–2023, and A/Victoria/4897/2022 (H1N1pdm09, VIC-22) recommended from 2023 to 2025.

The binding affinity of mAbs to HA was evaluated using ELISA. 2B2 demonstrated significant affinity for the HA protein of VIC-19, with an EC50 value of 8.1 ng/mL. It also showed affinity for HA proteins of CA-09, GD-19, and VIC-22, with EC50 values of 16.9 ng/mL, 15.8 ng/mL, and 19.3 ng/mL, respectively. Additionally, 2B2 exhibited lower affinity for MIC-15 and BR-18, with EC50 values of 741 ng/mL and 374 ng/mL, respectively. 2F6 displayed affinity for the HA protein of VIC-19 with an EC50 of 19.2 ng/mL. It also bound to the HA protein of GD-19 with an EC50 of 327 ng/mL. However, 2F6 showed considerably lower affinity for CA-09, BR-18, and VIC-22, with EC50 values of 2412 ng/mL, 3669 ng/mL, and 3420 ng/mL, respectively. Notably, both mAbs lacked affinity for the HA protein of BR-07. These findings indicate that 2B2 has broad-spectrum affinity for HA from vaccine strains of H1N1pdm09 viruses (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Antibody affinity evaluation for H1N1 vaccine strains. (A) The EC50 of mAbs was assessed by ELISA. Plates were incubated sequentially with HA protein, the antibody of interest, and HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody. OD was then measured at 450 nm wavelength. A value of 10,000 ng/mL is considered as no reaction. (B) The kinetics and affinity of 2B2 for HA from different H1N1 strains were evaluated by SPR. mAbs were immobilized onto CM5 chips, and HA proteins were introduced at varying concentrations to assess their interaction kinetics. (C—H) The association and dissociation curve of 2B2 with different H1N1 HA proteins, illustrate the interaction kinetics between the antibody and viral strain. The contact phase was 180 s, followed by a dissociation phase of 3600 s.

Further analysis of the interaction between 2B2 and HA from vaccine strains of H1N1pdm09 viruses was conducted using SPR. This analysis revealed the following affinity constants: CA-09 at 0.9082 nM, MIC-15 at 1.733 nM, BR-18 at 0.1605 nM, GD-19 at 0.466 nM, VIC-19 at 0.4274 nM, and VIC-22 at 0.369 nM (Fig. 1B-1H). These findings demonstrate that 2B2 exhibits a broad and effective affinity for HA across various H1N1 vaccine strains.

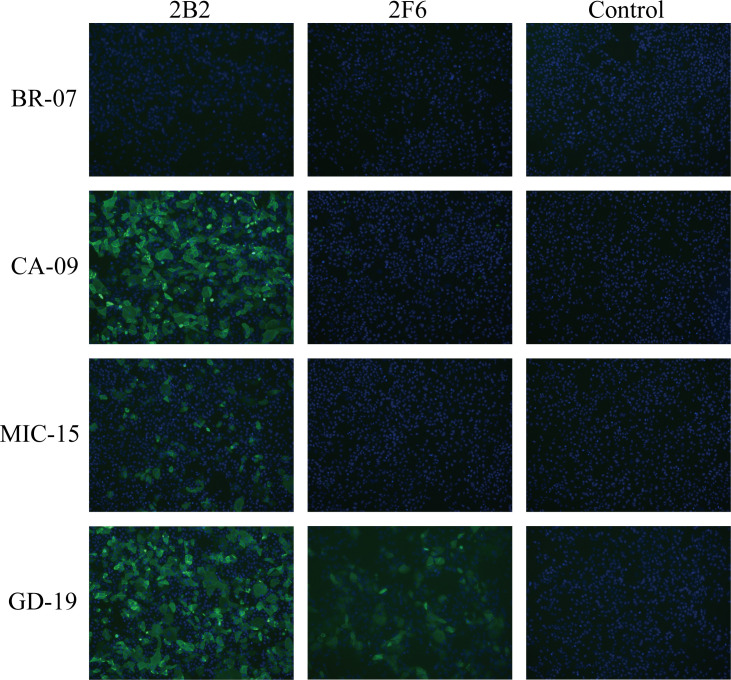

3.3. Specificity of H1N1 antibodies

The specificity of the two mAbs against H1N1 cells was assessed by IFA (Fig. 2). These results indicated that both mAbs were capable of binding to GD-19. However, only 2B2 bound to CA-09 and MIC-15. Neither antibody demonstrated binding affinity for BR-07.

Fig. 2.

The specificity of mAbs binding to various H1N1 influenza strains. IFA was conducted to assess the specificity of mAbs binding to different H1N1 strains. MDCK cells were infected with H1N1 strains (BR-07, CA-09, MIC-15, or GD-19) at an MOI of 0.5. After incubation, cells were fixed, permeabilized, and blocked, followed by the sequential incubation with mAbs and FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies. After washing, cells were stained with DAPI and fluorescent signals were observed using fluorescence microscopy. The images depict viral proteins in green and nuclei in blue.

3.4. HAI efficacy of antibodies

The HAI assay revealed that mAbs 2B2 and 2F6 did not inhibit hemagglutination in the pre-pandemic strain BR-07 (Fig. 3A). However, 2B2 exhibited potent HAI activity against CA-09, MIC-15, and GD-19, with HI titers of 0.01 μg/mL, 0.02 μg/mL, and 0.05 μg/mL, respectively. Similarly, 2F6 demonstrated strong HAI activity against these three strains, with titers of 0.2 μg/mL, 0.1 μg/mL, and 0.1 μg/mL, respectively.

Fig. 3.

In vitro evaluation of mAbs against influenza virus. (A) The HAI assay results for mAbs against H1N1 strains BR-07, CA-09, MIC-15, and GD-19. Serial 2-fold dilutions of mAbs or controls were mixed with virus solution and incubated. Subsequently, chicken RBCs were introduced to observe the agglutination. The HAI titer, defined as the reciprocal of the highest dilution that inhibits RBC agglutination. (B) The in vitro neutralizing activity of mAbs 2B2 and 2F6 against the four H1N1 strains. MDCK cells were treated with serially diluted antibodies and virus solution, followed by a hemagglutination assay to detect virus presence. The MN titer, defined as the reciprocal of the highest dilution preventing viral infection. (A-B) A titer of 50 indicates considered as no reaction.

3.5. In vitro neutralizing activity of antibodies

The MN assays revealed that neither 2B2 nor 2F6 were capable of neutralizing the pre-pandemic strain BR-07 in vitro (Fig. 3B). However, 2B2 exhibited strong neutralizing activity against CA-09, MIC-15, and GD-19, with MN titers of 0.39 μg/mL, 0.01 μg/mL, and 0.05 μg/mL, respectively. Conversely, 2F6 showed strong neutralizing activity against CA-09 and GD-19, with MN titers of 0.39 μg/mL and 0.05 μg/mL, respectively, but demonstrated weaker neutralizing activity against MIC-15, with a MN titer of 6.25 μg/mL.

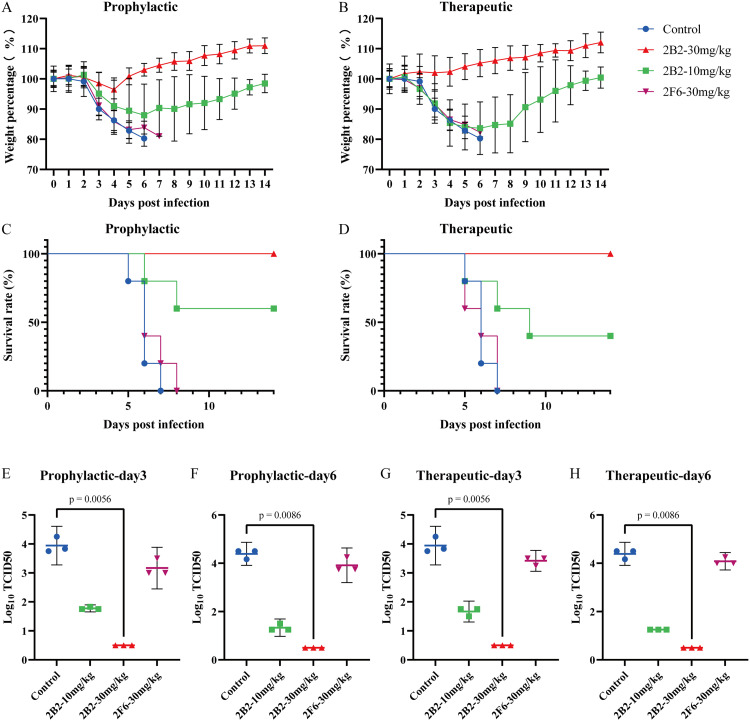

3.6. The prophylactic and therapeutic efficacy of mAbs in mice infected with M-MIC-15

This study assessed the prophylactic and therapeutic protective effects of mAbs in a mouse model of M-MIC-15.

The protective effects of 2B2 were dose dependent. At a dose of 30 mg/kg, 2B2 provided 100 % protection when administered either 6 h before (prophylactically) or 6 h after (therapeutically) infection (Fig. 4A-4D). At the lower dose of 10 mg/kg, 2B2 offered 60 % protection with prophylactic administration and 40 % protection with therapeutic administration at 6 h post-infection.

Fig. 4.

The prophylactic and therapeutic efficacy of mAbs against M-MIC-15 viral challenge in mice. (A-H) Mice were infected with 25 times LD50 of the M-MIC-15 influenza virus intranasally. Groups received 10 mg/kg or 30 mg/kg of the mAb intraperitoneally, either 6 h before or 6 h after infection. Body weights were monitored for 14 days daily. Lung samples were collected on days 3 and 6 post-infection for viral load assessment. (A, B) Body weight changes in (A) prophylactic group and (B) therapeutic group. (C, D) Survival rates in (C) prophylactic group and (D) therapeutic group. (E, F) Viral loads following prophylactic administration on (E) day 3 and (F) day 6 post-infection. (G, H) Viral loads following therapeutic administration on (G) day 3 and (H) day 6 post-infection. (E-H) In viral load assessment, a TCID50 of 10 0.5 indicates no virus detected. Statistical analyses were conducted using the Kruskal-Wallis test, complemented by Dunn's multiple comparison test for post-hoc analysis.

Furthermore, analysis of the viral load in mouse lung tissue indicated that 2B2 significantly reduced viral replication within the lungs at a dose of 30 mg/kg. In the control group, viral titers in the lungs significantly increased at 3 days post-infection and further increased after 6 days. In contrast, both prophylactic and therapeutic administration of 2B2 significantly reduced pulmonary viral titers (Fig. 4E–H).

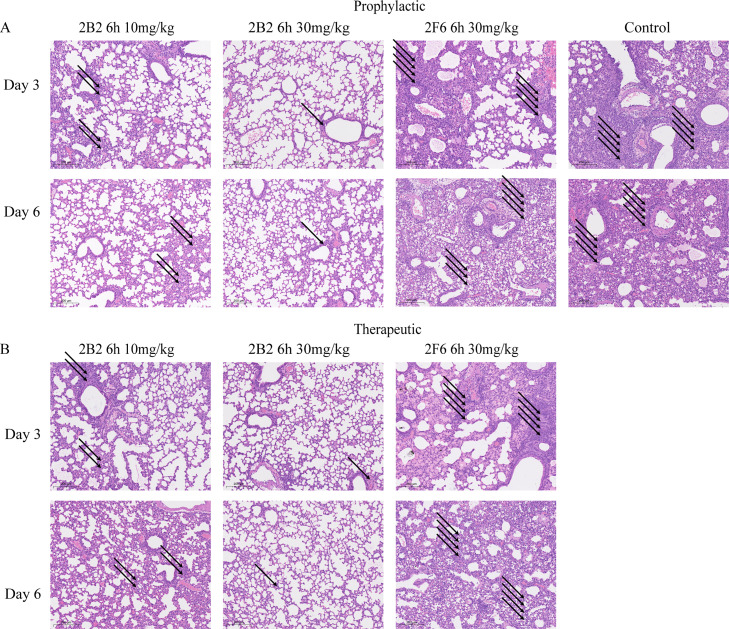

Pathological changes in mouse lung tissues are shown in Fig. 5. In the control group, significant inflammatory cell infiltration and alveolar and interstitial edema were observed in the lung tissues 3 days post-infection. The pathology worsened at 6 days post-infection, with the presence of inflammatory exudates in the alveolar spaces, including inflammatory cells, cellular debris, and other inflammatory products. Both the prophylactic and therapeutic groups exhibited a reduction in lung tissue pathology to some extent, particularly at the 30 mg/kg dose, where lung tissue damage was minimal and was characterized by a slight thickening of the alveolar walls, localized inflammatory cell infiltration, and mild edema.

Fig. 5.

Comparative histological analysis of M-MIC-15 infection and 2B2 treatment on mouse lung tissues. (A-B) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed. Histological sections of mouse lung tissues stained to show the presence of inflammatory cell infiltrations in (A) prophylactic group and (B) therapeutic group. Arrows indicate areas of inflammatory cell infiltration, with the number of arrows reflecting the severity of pulmonary lesions. The scale bar in each image represents 200 μm.

However, regarding the results for 2F6, the outcomes of both prophylactic and therapeutic administration at a dosage of 30 mg/kg showed no significant difference compared to those of the control group, indicating no effect on either the prevention or treatment of the infection. (Fig. 4, Fig. 5).

3.7. The prophylactic and therapeutic efficacy of mAbs in mice infected with M-GD-19

In this study, we assessed the prophylactic and therapeutic effects of 2B2 and 2F6 in a mouse model of M-GD-19 (Fig. 6). Both 2B2 and 2F6 exhibited protective effects against the virus in infected mice. Under the protection of a 10 mg/kg dose, both for prophylaxis (24 h before) and treatment (24 h after), there was a significant reduction in viral titers within the lung tissue of the mice.

Fig. 6.

The prophylactic and therapeutic efficacy of mAbs against M-GD-19 viral challenge in mice. (A-D) The evaluation of mAbs against M-GD-19 virus challenge in mice. The mice were infected with the virus intranasally. The experimental groups were intraperitoneally administered with 1, 3, or 10 mg/kg of 2B2 or 2F6 mAbs respectively, either 24 h before or 24 h after infection. Lung samples were collected on days 3 and 6 post-infection for viral load assessment. The viral loads were qualified following the prophylactic administration of 2B2 and 2F6 on (A) day 3 and (B) day 6 post-infection or therapeutic administration of same mAbs on (C) day 3 and (D) day 6 post-infection. A TCID50 of 10 0.5 indicates no virus detected. Statistical analyses were conducted using the Kruskal-Wallis test, complemented by Dunn's multiple comparison test for post-hoc analysis.

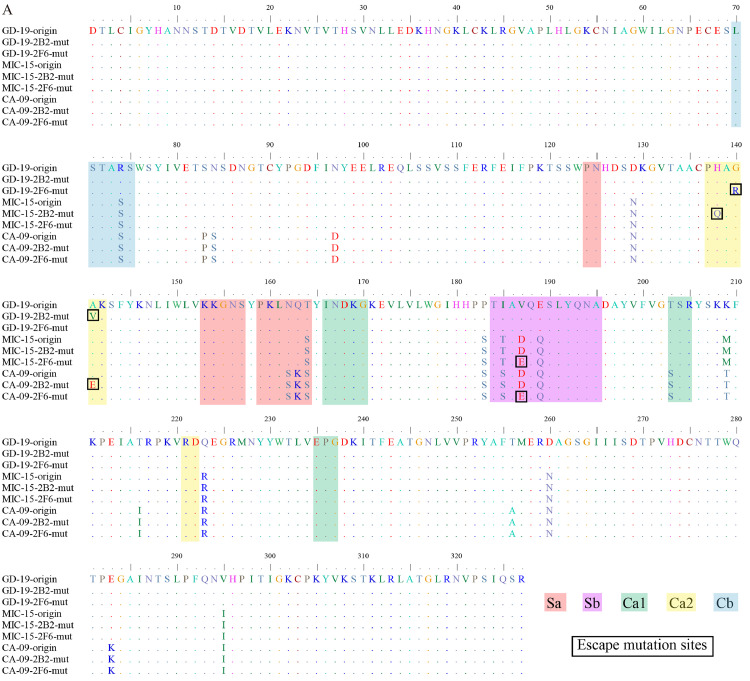

3.8. Antigenic site analysis of H1N1 influenza virus

After separately mixing 2B2 with each of the CA-09 strain, MIC-15 strain, and GD-19 strain, and separately mixing 2F6 with each of the same strains, the mixtures were injected into distinct chicken embryos for co-cultivation. Escape mutant strains containing a single amino acid substitution were identified. Under the selective pressure of 2F6, amino acid substitutions were observed in all three strains. In the CA-09 and MIC-15 strains, the substitution D187E was identified within the Sb antigenic site, which is associated with adaptation to avian species (Matrosovich et al., 2000). Additionally, the GD-19 strain exhibited the amino acid substitution G140R under the selective pressure of 2F6. Furthermore, under the selective pressure of 2B2, the CA-09, MIC-15, and GD-19 strains showed distinct amino acid substitutions: A141E, H138Q, and A141V, respectively (Fig. 7A).

Fig. 7.

The presence of escape mutations on HA protein of H1N1 influenza virus. (A) The comparative analysis of sequencing results for the original strains CA-09, MIC-15, and GD-19, as well as their escape mutant variants. (B-C) Structural Visualization: Top (B) and side (C) views of the CA-09 HA protein structure, highlighting the locations of identified escape mutations within the antigenic sites. These structural representations were generated using Pymol based on the RCSB PDB entry 3LZG. (D) The fold Increase in HAI activity of escape mutants compared to wild-type strain. Escape mutants induced by 2B2 are denoted by triangles (▲), while those induced by m 2F6 are marked with inverted triangles (▼).

The presence of amino acid position D187 was exclusive to strains CA-09 and MIC-15. Conversely, the Ca2 sequence was consistent across strains CA-09, MIC-15, and GD-19. The spatial structural relationships of several amino acid substitution sites were elucidated using Pymol, with a particular focus on the representative strain, CA-09 (Fig. 7B, C).

HAI assay revealed that escape mutants induced by 2B2 or 2F6 significantly reduced the HAI activity of 2B2. Specifically, amino acid substitution A141V in strain MIC-15, induced by mAb 2B2, only slightly diminished the HAI activity of 2F6. Furthermore, the amino acid substitution A141V in strain GD-19, which was also induced by 2B2, did not reduce the HAI activity of 2F6 (Fig. 7D).

Grouping analysis revealed that within the H1N1 influenza virus, the amino acid positions H138 and G140 were highly conserved (Table.2). Additionally, prior to 2009, the A141 site was not conserved, with the 141st amino acid position predominantly comprising E141 and K141. Conversely, in the H1N1pdm09 viruses, A141 exhibited high conservation exceeding 90 %. The conservation of D187 varied over time; it was moderate (greater than 70 %) in strains before 2009 and from 2019 to 2022, and high (greater than 90 %) in strains from 2009 to 2018 and in 2023.

Table. 2.

Polymorphism analysis of amino acid substitution sites.

| Residues |

Percentage of AA in the human H1N1 epidemic strain (%) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −2008 (n = 2283) |

2009–2014 (n = 17,675) |

2015–2018 (n = 20,190) |

2019–2022 (n = 26,193) |

2023 (n = 19,066) |

Total (n = 85,407) |

|

| 138 | H 138 (2252, 98.64 %); Q 138 (0, 0.00 %) Others (31, 0.14 %) |

H 138 (17,282, 97.78 %); Q 138 (160, 0.91 %) Others (233, 1.32 %) |

H 138 (20,015, 99.13 %); Q 138 (29, 0.14 %) Others (146, 0.72 %) |

H 138 (25,903, 98.89 %); Q 138 (154, 0.59 %) Others (136, 0.52 %) |

H 138 (19,036, 99.84 %); Q 138 (13, 0.07 %) Others (17, 0.09%) |

H 138 (84,488, 98.92 %); Q 138 (347, 0.41 %) Others (572, 0.67 %) |

| 140 | G 140 (2265, 99.21 %); R 140 (6, 0.26 %) Others (12, 0.53 %) |

G 140 (17,641, 99.81 %); R 140 (2, 0.01 %) Others (32,0.18 %) |

G 140 (20,180, 99.95 %); R 140 (8, 0.04 %) Others (2, 0.01 %) |

G 140 (26,176, 99.94 %); R 140 (12, 0.05 %) Others (5, 0.02 %) |

G 140 (19,049, 99.91 %); R 140 (8, 0.04 %) Others (9, 0.05%) |

G 140 (85,311, 99.89 %); R 140 (36, 0.04 %) Others (60, 0.07 %) |

| 141 | A 141 (26, 1.14 %); E 141 (1107, 48.49 %) V 141 (1, 0.04 %) K 141 (1099, 48.14 %) Others (50, 2.20%) |

A 141 (17,416, 98.53 %); E 141 (90, 0.51 %) 141 V (9, 0.05 %) Others (160, 0.91 %) |

A 141 (19,943, 98.78 %); E 141 (129, 0.64 %) 141 V (8, 0.04 %) Others (110, 0.54 %) |

A 141 (25,985, 99.21 %); E 141 (0, 0.00 %) 141 V (60, 0.23 %) Others (148, 0.57 %) |

A 141 (18,508, 97.07 %); E 141 (201, 1.05 %) 141 V (209, 1.10 %) Others (148, 0.78 %) |

A 141 (81,878, 95.87 %); E 141 (1527, 1.79 %) 141 V (287, 0.34 %) Others (1715, 2.01 %) |

| 187 | D 187 (1600, 70.08 %); E 187 (61, 2.67 %) Others (622, 27.24 %) |

D 187 (17,539, 99.23 %); E 187 (81, 0.46 %) Others (55, 0.31 %) |

D 187 (20,141, 99.76 %); E 187 (5, 0.02 %) Others (44, 0.22 %) |

D 187 (20,861, 79.64 %); E 187 (2, 0.01 %) Others (5330, 20.35 %) |

D 187 (18,988, 99.59 %); E 187 (0, 0.00 %) Others (78, 0.41%) |

D 187 (79,129, 92.65 %); E 187 (149, 0.17 %) Others (6129, 7.18 %) |

4. Discussion

It is estimated that influenza annually causes the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people worldwide (Iuliano et al., 2018; Simonsen et al., 2013), highlighting the significant public health challenges posed by influenza.

HA, a key molecule in the viral life cycle, facilitates viral recognition and entry into the host cells (Chen et al., 1999; Weis et al., 1988). Recurrent infections caused by the human influenza virus are largely attributed to antigenic drift in HA (Petrova and Russell, 2018). The interaction between antibodies and influenza virus surface glycoproteins, especially HA, is crucial for the defense against influenza virus infections (Krammer, 2019).

HA consists of two structurally and functionally distinct domains: a variable immunodominant globular head and a conserved immunosubdominant stem region (Krammer and Palese, 2013). In this study, two mAbs against H1N1 the head region of the generated. Antibodies targeting the HA head region typically exhibit strong neutralizing activity, often including the inhibition of hemagglutination. In contrast, antibodies that target the HA stem region derived from human isolates demonstrate broad viral recognition and binding to various viral isolates and subtypes.

In recent decades, numerous antibodies targeting the HA head region have been developed, including 5J8 and Ab6649 (Hong et al., 2013; Raymond et al., 2018), which show broad neutralizing reactivity against H1N1 influenza viruses. mAb C12H5 is particularly notable for its ability to neutralize a wide range of H1N1 influenza viruses and cross-neutralize H5N1 avian influenza viruses (Li et al., 2022). However, its effectiveness against a newer vaccine strain, GD-19, remains unknown. Additionally, mAbs targeting the HA head region of MIC-15 demonstrate suboptimal neutralization of GD-19 (Wang et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2022b). This study successfully identified mAbs with enhanced broad-spectrum efficacy against H1N1pdm09 viruses using updated vaccine strains for mouse immunization.

2B2 exhibited superior affinity and broad-spectrum activity against various H1N1 strains, as demonstrated by its lower EC50 values in ELISA assays and potent HAI capabilities. For M-MIC-15, 2B2 offered dose-dependent protection, achieving 100 % efficacy at 30 mg/kg and reducing lung viral load and pathology. In contrast, 2F6 showed no protective effect against M-MIC-15. Regarding M-GD-19, both 2B2 and 2F6 reduced viral titers at 10 mg/kg, indicating 2B2′s broad effectiveness and 2F6′s strain-specific protection.

Analysis of the antigenicity of escape mutants, selected for having undergone antigenic changes due to mAb pressure, is a common strategy for mapping HA protein epitopes. This study identified four escape mutation sites resulting in five amino acid changes (H138Q, G140R, A141E/A141V, and D187E) in H1N1 influenza virus strains CA-09, MIC-15, and GD-19. Residue D187 is located within antigenic site Sb and involved in binding to longer polysaccharide chains of sialic acid α2,6-galactose (Ha et al., 2001), and the substitution D187E has been associated with adaptation to avian species. This amino acid substitution leads to a reduction in HAI activity and the affinity of many neutralizing antibodies targeting the HA protein head of H1N1 influenza viruses (Li et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2022a; Yasuhara et al., 2018). Although this site was moderately conserved before 2009, it became highly conserved between 2009 and 2018. Despite prior emphasis on the high conservation of the D187 site in H1N1pdm09 viruses, its conservation decreased to moderate levels after 2019, signifying the need for increased monitoring of this amino acid site.

Amino acid substitutions at positions H138, G140, and A141, located within antigenic site Ca2, interfere with the formation of main chain or side chain hydrogen bonds, thereby impeding the binding of hemagglutinin to mAbs (Hong et al., 2013).

Furthermore, the amino acid substitutions at residue A141 significantly reduced the HAI titer of broadly neutralizing 2B2 against vaccine strains of H1N1pdm09 viruses, including CA-09 and GD-19. Previous studies have demonstrated that the amino acid substitution A141E in the CA-09 strain significantly reduces the HAI titers of multiple neutralizing antibodies targeting the head of H1N1 HA protein, highlighting the critical nature of the residue A141 (Chen et al., 2014; Li et al., 2022). Analysis of all sequences in the NCBI influenza database concluded that the A141 site is moderately conserved, with a conservation level above 70 % (Li et al., 2022). However, because sequences from prior to 2009 constituted less than 10 % of the database, this conclusion may not fully reflect the conservation level of the site. The analysis of sequences grouped by period, sourced from the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID), revealed that the A141 site was not conserved before 2009, but became highly conserved afterward, illustrating the significance of the A141 amino acid site in H1N1pdm09 viruses.

Due to the highly immunogenic nature of the mouse-derived mAbs produced in this study, their clinical utility is limited. Further humanization is necessary before they can be considered for advanced clinical applications (Hwang and Foote, 2005).

Despite significant progress in the use of mAbs to treat viral infections, challenges persist due to the high mutation rates of viruses, particularly RNA viruses. Under the selective pressure exerted by mAbs, viruses can rapidly undergo escape mutations, leading to resistance. For instance, in immunocompetent patients, treatment with the mAb bamlanivimab alone can swiftly select for strains of SARS-CoV-2 that are resistant to this antibody, resulting in increased viral load and exacerbated symptoms (Choudhary et al., 2022). The use of non-competitive mAb cocktails has been shown to slow the emergence of escape mutations in SARS-CoV-2 (Baum et al., 2020; Copin et al., 2021; Ragonnet-Cronin et al., 2023). Inmazeb (REGN-EB3), a cocktail of three antibodies against Ebola virus, can prevent the rapid emergence of escape mutants, a success not mirrored by single-antibody therapies targeting conserved antigenic clusters (Rayaprolu et al., 2023). Future research could first elucidate the precise antigenic epitopes targeted by mAbs 2B2 and 2F6, then assess the synergistic effects of combining these antibodies with other influenza mAbs that target different epitopes.

Moreover, the high cost of mAbs limits their widespread use and global application. The production process can be simplified, and costs can be reduced by expressing antibodies through DNA or RNA technologies. For example, using an adeno-associated virus (AAV) as a vector to deliver the genetic information required for expressing target mAbs within host cells can enable long-term in-body production of these antibodies (Daya and Berns, 2008). The delivery of mAbs via mRNA is currently a research focus, offering advantages, such as rapid protein expression and high clinical safety (Hollevoet and Declerck, 2017; Van Hoecke and Roose, 2019).

In conclusion, this study underscores the critical role of HA-specific mAbs in neutralizing diverse strains of H1N1 influenza virus. The generation and characterization of mAbs 2B2 and 2F6 illustrate the feasibility of targeting HA to achieve broad-spectrum antiviral activity. Importantly, our research identified specific amino acid substitutions at residues H138, G140, A141, and D187 that contribute to viral evasion. This evasion is characterized by a significant reduction in HAI titers of mAbs against these mutant strains, emphasizing the dynamic nature of viral evolution and the challenges posed by mAb therapy. The emergence of escape mutants highlights the need for continuous surveillance of viral mutations and development of combination therapies to mitigate the risk of resistance.

Funding

This research was funded by Grants from the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2022ZFJH003).

Ethical approval

The animal experiment was approved by the First Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University (No. 2022-16).

Declaration of generative AI in scientific writing

During the preparation of this work authors used ChatGPT in order to improve language and readability. After using this tool/service, authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Xiantian Lin: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Fan Yang: Methodology, Data curation. Sijing Yan: Validation, Formal analysis. Han Wu: Visualization. Ping Wang: Investigation. Yuxi Zhao: Formal analysis. Danrong Shi: Methodology. Hangping Yao: Resources. Haibo Wu: Writing – review & editing, Project administration. Lanjuan Li: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our sincere gratitude to Dr. Yang Liu from Shenzhen Bay Laboratory for his invaluable assistance in enhancing the readability of this paper.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Baum A., Fulton B.O., Wloga E., Copin R., Pascal K.E., Russo V., Giordano S., Lanza K., Negron N., Ni M., Wei Y., Atwal G.S., Murphy A.J., Stahl N., Yancopoulos G.D., Kyratsous C.A. Antibody cocktail to SARS-CoV-2 spike protein prevents rapid mutational escape seen with individual antibodies. Science. 2020;369:1014–1018. doi: 10.1126/science.abd0831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y., Su B., Guo X., Sun W., Deng Y., Bao L., Zhu Q., Zhang X., Zheng Y., Geng C., Chai X., He R., Li X., Lv Q., Zhu H., Deng W., Xu Y., Wang Y., Qiao L., Tan Y., Song L., Wang G., Du X., Gao N., Liu J., Xiao J., Su X.-D., Du Z., Feng Y., Qin Chuan, Qin Chengfeng, Jin R., Xie X.S. Potent neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 identified by high-throughput single-cell sequencing of convalescent patients’ B cells. Cell. 2020;182:73–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.025. e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Skehel J.J., Wiley D.C. N- and C-terminal residues combine in the fusion-pH influenza hemagglutinin HA2 subunit to form an N cap that terminates the triple-stranded coiled coil. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1999;96:8967–8972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.8967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Yan B., Chen Q., Yao Y., Wang Huadong, Liu Q., Zhang S., Wang Hanzhong, Chen Z. Evaluation of neutralizing efficacy of monoclonal antibodies specific for 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza A virus in vitro and in vivo. Arch. Virol. 2014;159:471–483. doi: 10.1007/s00705-013-1852-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary M.C., Chew K.W., Deo R., Flynn J.P., Regan J., Crain C.R., Moser C., Hughes M.D., Ritz J., Ribeiro R.M., Ke R., Dragavon J.A., Javan A.C., Nirula A., Klekotka P., Greninger A.L., Fletcher C.V., Daar E.S., Wohl D.A., Eron J.J., Currier J.S., Parikh U.M., Sieg S.F., Perelson A.S., Coombs R.W., Smith D.M., Li J.Z. Emergence of SARS-CoV-2 escape mutations during Bamlanivimab therapy in a phase II randomized clinical trial. Nat. Microbiol. 2022;7:1906–1917. doi: 10.1038/s41564-022-01254-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copin R., Baum A., Wloga E., Pascal K.E., Giordano S., Fulton B.O., Zhou A., Negron N., Lanza K., Chan N., Coppola A., Chiu J., Ni M., Wei Y., Atwal G.S., Hernandez A.R., Saotome K., Zhou Y., Franklin M.C., Hooper A.T., McCarthy S., Hamon S., Hamilton J.D., Staples H.M., Alfson K., Carrion R., Ali S., Norton T., Somersan-Karakaya S., Sivapalasingam S., Herman G.A., Weinreich D.M., Lipsich L., Stahl N., Murphy A.J., Yancopoulos G.D., Kyratsous C.A. The monoclonal antibody combination REGEN-COV protects against SARS-CoV-2 mutational escape in preclinical and human studies. Cell. 2021;184:3949–3961. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.06.002. e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novel Swine-Origin Influenza A (H1N1) Virus Investigation Team. Dawood F.S., Jain S., Finelli L., Shaw M.W., Lindstrom S., Garten R.J., Gubareva L.V., Xu X., Bridges C.B., Uyeki T.M. Emergence of a novel swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus in humans. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:2605–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0903810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daya S., Berns K.I. Gene therapy using adeno-associated virus vectors. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2008;21:583–593. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00008-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch W.M., Bush R.M., Bender C.A., Cox N.J. Long term trends in the evolution of H(3) HA1 human influenza type A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:7712–7718. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.7712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garten R.J., Davis C.T., Russell C.A., Shu B., Lindstrom S., Balish A., Sessions W.M., Xu X., Skepner E., Deyde V., Okomo-Adhiambo M., Gubareva L., Barnes J., Smith C.B., Emery S.L., Hillman M.J., Rivailler P., Smagala J., de Graaf M., Burke D.F., Fouchier R.A.M., Pappas C., Alpuche-Aranda C.M., López-Gatell H., Olivera H., López I., Myers C.A., Faix D., Blair P.J., Yu C., Keene K.M., Dotson P.D., Boxrud D., Sambol A.R., Abid S.H., St George K., Bannerman T., Moore A.L., Stringer D.J., Blevins P., Demmler-Harrison G.J., Ginsberg M., Kriner P., Waterman S., Smole S., Guevara H.F., Belongia E.A., Clark P.A., Beatrice S.T., Donis R., Katz J., Finelli L., Bridges C.B., Shaw M., Jernigan D.B., Uyeki T.M., Smith D.J., Klimov A.I., Cox N.J. Antigenic and genetic characteristics of swine-origin 2009 A(H1N1) influenza viruses circulating in humans. Science. 2009;325:197–201. doi: 10.1126/science.1176225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhard W., Webster R.G. Antigenic drift in influenza A viruses. I. Selection and characterization of antigenic variants of A/PR/8/34 (HON1) influenza virus with monoclonal antibodies. J. Exp. Med. 1978;148:383–392. doi: 10.1084/jem.148.2.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhard W., Yewdell J., Frankel M.E., Webster R. Antigenic structure of influenza virus haemagglutinin defined by hybridoma antibodies. Nature. 1981;290:713–717. doi: 10.1038/290713a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha Y., Stevens D.J., Skehel J.J., Wiley D.C. X-ray structures of H5 avian and H9 swine influenza virus hemagglutinins bound to avian and human receptor analogs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:11181–11186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201401198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollevoet K., Declerck P.J. State of play and clinical prospects of antibody gene transfer. J. Transl. Med. 2017;15:131. doi: 10.1186/s12967-017-1234-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong M., Lee P.S., Hoffman R.M.B., Zhu X., Krause J.C., Laursen N.S., Yoon S., Song L., Tussey L., Crowe J.E., Ward A.B., Wilson I.A. Antibody recognition of the pandemic H1N1 influenza virus hemagglutinin receptor binding site. J. Virol. 2013;87:12471–12480. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01388-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang W.Y.K., Foote J. Immunogenicity of engineered antibodies. Methods. 2005;36:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iuliano A.D., Roguski K.M., Chang H.H., Muscatello D.J., Palekar R., Tempia S., Cohen C., Gran J.M., Schanzer D., Cowling B.J., Wu P., Kyncl J., Ang L.W., Park M., Redlberger-Fritz M., Yu H., Espenhain L., Krishnan A., Emukule G., van Asten L., Pereira da Silva S., Aungkulanon S., Buchholz U., Widdowson M.-A., Bresee J.S., Global Seasonal Influenza-associated Mortality Collaborator Network Estimates of global seasonal influenza-associated respiratory mortality: a modelling study. Lancet. 2018;391:1285–1300. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33293-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y., Lei C., Hu D., Dimitrov D.S., Ying T. Human monoclonal antibodies as candidate therapeutics against emerging viruses. Front. Med. 2017;11:462–470. doi: 10.1007/s11684-017-0596-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson N.P.A.S., Mueller J. Updating the accounts: global mortality of the 1918–1920 “Spanish” influenza pandemic. Bull. Hist. Med. 2002;76:105–115. doi: 10.1353/bhm.2002.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H., Webster R.G., Webby R.J. Influenza virus: dealing with a drifting and shifting pathogen. Viral Immunol. 2018;31:174–183. doi: 10.1089/vim.2017.0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krammer F., Palese P. Influenza virus hemagglutinin stalk-based antibodies and vaccines. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2013;3:521–530. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krammer F. The human antibody response to influenza A virus infection and vaccination. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019;19:383–397. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0143-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laver W.G., Gerhard W., Webster R.G., Frankel M.E., Air G.M. Antigenic drift in type A influenza virus: peptide mapping and antigenic analysis of A/PR/8/34 (HON1) variants selected with monoclonal antibodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1979;76:1425–1429. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.3.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T., Chen J., Zheng Q., Xue W., Zhang L., Rong R., Zhang S., Wang Q., Hong M., Zhang Y., Cui L., He M., Lu Z., Zhang Z., Chi X., Li J., Huang Y., Wang H., Tang J., Ying D., Zhou L., Wang Y., Yu H., Zhang J., Gu Y., Chen Y., Li S., Xia N. Identification of a cross-neutralizing antibody that targets the receptor binding site of H1N1 and H5N1 influenza viruses. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:5182. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-32926-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S.T.H., Behzadi M.A., Sun W., Freyn A.W., Liu W.-C., Broecker F., Albrecht R.A., Bouvier N.M., Simon V., Nachbagauer R., Krammer F., Palese P. Antigenic sites in influenza H1 hemagglutinin display species-specific immunodominance. J. Clin. Invest. 2018;128:4992–4996. doi: 10.1172/JCI122895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matrosovich M., Tuzikov A., Bovin N., Gambaryan A., Klimov A., Castrucci M.R., Donatelli I., Kawaoka Y. Early alterations of the receptor-binding properties of H1, H2, and H3 avian influenza virus hemagglutinins after their introduction into mammals. J. Virol. 2000;74:8502–8512. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.18.8502-8512.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrova V.N., Russell C.A. The evolution of seasonal influenza viruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018;16:47–60. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragonnet-Cronin M., Nutalai R., Huo J., Dijokaite-Guraliuc A., Das R., Tuekprakhon A., Supasa P., Liu C., Selvaraj M., Groves N., Hartman H., Ellaby N., Mark Sutton J., Bahar M.W., Zhou D., Fry E., Ren J., Brown C., Klenerman P., Dunachie S.J., Mongkolsapaya J., Hopkins S., Chand M., Stuart D.I., Screaton G.R., Rokadiya S. Generation of SARS-CoV-2 escape mutations by monoclonal antibody therapy. Nat. Commun. 2023;14:3334. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-37826-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayaprolu V., Fulton B.O., Rafique A., Arturo E., Williams D., Hariharan C., Callaway H., Parvate A., Schendel S.L., Parekh D., Hui S., Shaffer K., Pascal K.E., Wloga E., Giordano S., Negron N., Ni M., Copin R., Atwal G.S., Franklin M., Boytz R.M., Donahue C., Davey R., Baum A., Kyratsous C.A., Saphire E.O. Structure of the Inmazeb cocktail and resistance to Ebola virus escape. Cell Host Microbe. 2023;31:260–272. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2023.01.002. e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond D.D., Bajic G., Ferdman J., Suphaphiphat P., Settembre E.C., Moody M.A., Schmidt A.G., Harrison S.C. Conserved epitope on influenza-virus hemagglutinin head defined by a vaccine-induced antibody. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2018;115:168–173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1715471115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonsen L., Spreeuwenberg P., Lustig R., Taylor R.J., Fleming D.M., Kroneman M., Van Kerkhove M.D., Mounts A.W., Paget W.J. Global mortality estimates for the 2009 influenza pandemic from the GLaMOR project: a modeling study. PLoS Med. 2013;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith G.J.D., Vijaykrishna D., Bahl J., Lycett S.J., Worobey M., Pybus O.G., Ma S.K., Cheung C.L., Raghwani J., Bhatt S., Peiris J.S.M., Guan Y., Rambaut A. Origins and evolutionary genomics of the 2009 swine-origin H1N1 influenza A epidemic. Nature. 2009;459:1122–1125. doi: 10.1038/nature08182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan Y., Ng Q., Jia Q., Kwang J., He F. A novel humanized antibody neutralizes H5N1 influenza virus via two different mechanisms. J. Virol. 2015;89:3712–3722. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03014-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong S., Zhu X., Li Y., Shi M., Zhang J., Bourgeois M., Yang H., Chen X., Recuenco S., Gomez J., Chen L.-M., Johnson A., Tao Y., Dreyfus C., Yu W., McBride R., Carney P.J., Gilbert A.T., Chang J., Guo Z., Davis C.T., Paulson J.C., Stevens J., Rupprecht C.E., Holmes E.C., Wilson I.A., Donis R.O. New world bats harbor diverse influenza A viruses. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoecke L., Roose K. How mRNA therapeutics are entering the monoclonal antibody field. J. Transl. Med. 2019;17:54. doi: 10.1186/s12967-019-1804-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijaykrishna D., Poon L.L.M., Zhu H.C., Ma S.K., Li O.T.W., Cheung C.L., Smith G.J.D., Peiris J.S.M., Guan Y. Reassortment of pandemic H1N1/2009 influenza A virus in swine. Science. 2010;328:1529. doi: 10.1126/science.1189132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan H., Gao J., Xu K., Chen H., Couzens L.K., Rivers K.H., Easterbrook J.D., Yang K., Zhong L., Rajabi M., Ye J., Sultana I., Wan X.-F., Liu X., Perez D.R., Taubenberger J.K., Eichelberger M.C. Molecular basis for broad neuraminidase immunity: conserved epitopes in seasonal and pandemic H1N1 as well as H5N1 influenza viruses. J. Virol. 2013;87:9290–9300. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01203-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Yang F., Xiao Y., Chen B., Liu F., Cheng L., Yao H., Wu N., Wu H. Generation, characterization, and protective ability of mouse monoclonal antibodies against the HA of A (H1N1) influenza virus. J. Med. Virol. 2022;94:2558–2567. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis W., Brown J.H., Cusack S., Paulson J.C., Skehel J.J., Wiley D.C. Structure of the influenza virus haemagglutinin complexed with its receptor, sialic acid. Nature. 1988;333:426–431. doi: 10.1038/333426a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Manual for the Laboratory Diagnosis and Virological Surveillance of Influenza. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Yang F., Yan S., Zhu L., Wang F.X.C., Liu F., Cheng L., Yao H., Wu N., Lu R., Wu H. Evaluation of panel of neutralising murine monoclonal antibodies and a humanised bispecific antibody against influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus infection in a mouse model. Antiviral Res. 2022;208 doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2022.105462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F., Zhu L., Liu F., Cheng L., Yao H., Wu N., Wu H., Li L. Generation and characterization of monoclonal antibodies against the hemagglutinin of H3N2 influenza A viruses. Virus Res. 2022;317 doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2022.198815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuhara A., Yamayoshi S., Ito M., Kiso M., Yamada S., Kawaoka Y. Isolation and characterization of human monoclonal antibodies that recognize the influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus hemagglutinin receptor-binding site and rarely yield escape mutant viruses. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.