Abstract

Background:

Pediatric asthma is among the most common health conditions and disproportionately impacts Black and Latino children. Gaps in asthma care exist and may contribute to racial and ethnic inequities. The Rhode Island Asthma Integrated Response (RI-AIR) program was developed to address current limitations in care. The aims of the RI-AIR Hybrid Type II effectiveness-implementation trial were to: a) simultaneously evaluate the effectiveness of RI-AIR on individual-level and community-level outcomes; b) evaluate implementation strategies used to increase uptake of RI-AIR. In this manuscript, we outline the design and methods used to implement RI-AIR.

Methods:

School-based areas (polygons) with the highest asthma-related urgent healthcare utilization in Greater Providence, R.I., were identified using geospatial mapping. Families with eligible children (2–12 years) living in one of the polygons received evidence-based school- and/or home-based asthma management interventions, based on asthma control level. School-based interventions included child and caregiver education programs and school staff trainings. Home-based interventions included individualized asthma education, home-environmental assessments, and strategies and supplies for trigger remediation. Implementation strategies included engaging school nurse teachers as champions, tailoring interventions to school preferences, and engaging families for input.

Results:

A total of 6420 children were screened throughout the study period, 811 were identified as eligible, and 433 children were enrolled between November 2018 and December 2021.

Conclusions:

Effective implementation of pediatric asthma interventions is essential to decrease health inequities and improve asthma management. The RI-AIR study serves as an example of a multi-level intervention to improve outcomes and reduce disparities in pediatric chronic disease.

Clinical Trials Registration Number:

Keywords: Pediatric asthma, Community intervention program, Hybrid Type II, Effectiveness and implementation, Home-based intervention, School-based intervention

1. Introduction

Asthma affects 5.8% of U.S. children, with higher rates observed among Black (10.3%) and Latino (6.7%) children [1]. In Greater Providence, Rhode Island (R.I.; the city of Providence and surrounding area), 25% of elementary-school aged children have asthma, with Latino and Black children exhibiting the highest rates of asthma-related urgent healthcare utilization (emergency department [ED] visits, hospitalizations) [2]. Notably, 79% of children in Greater Providence belong to a racially or ethnically minoritized group and 30% live in poverty [2]. While clinical guidelines for asthma management exist, gaps in care remain and contribute to racial and ethnic health inequities [3–5]. Persistent inequities in outcomes call for a comprehensive, coordinated system of assessment and intervention.

Prior research has identified multi-level factors contributing to asthma disparities, including biological (e.g., genetics [6]), environmental (e.g., poverty [7]), individual/family (e.g., medication adherence [8,9]), and healthcare system factors (e.g., lower quality family-provider interaction [4,9]). These stressors interact and challenge asthma management [10] and increase disease morbidity [11]. Providing culturally-tailored interventions can target modifiable processes within families’ control (e.g., asthma management, caregiver burden, family support, medication beliefs, factors relating to environmental context) [12–15].

Prior and ongoing research demonstrates how home- and school-based interventions can improve disease outcomes among youth of racially and ethnically diverse backgrounds (e.g., adherence [16], hospitalizations, ED visits [17]). Bryant-Stephens and colleagues implemented an asthma care plan in West Philadelphia, which included randomly assigning families of children 5–13 years old to a primary care intervention or usual care, and a school intervention or control condition [18]. Additionally, an asthma care program in Virginia randomized, at the school level, families of children 5–11 years old to one of three groups consisting of asthma education, home environmental remediation, school intervention, and/or enhanced standard care [19]. A separate investigation by Naar et al. demonstrated the effectiveness of community-engaged asthma care; adolescents randomly assigned to a Multisystemic Therapy–Health Care condition (i.e., home- and community-based treatment) demonstrated greater improvements in lung function and asthma symptom frequency compared to a control condition [20]. The RI-AIR program is unique in targeting areas of high burden using geospatial mapping and stratifying multi-level (home and school) intervention assignment according to level of asthma control.

Our Community Asthma Programs (CAP) serve families of children with high asthma burden and facilitate services in home, school, social, and medical settings. We developed two programs: Home Asthma Response Program (HARP), a home-based service for asthma management education and environmental control, and Controlling Asthma in Schools Effectively (CASE) program, a school-based asthma management and education program [21,22]. Despite these culturally-tailored approaches, urban penetration, and partnership with the R.I. Department of Health, a multi-method community-based needs assessment identified gaps in asthma care [23–27]. The needs assessment indicated our community interventions and asthma services were operating in isolation, with limited coordination of care and communication across home, school, and medical settings.

The Rhode Island Asthma Integrated Response (RI-AIR) program was developed to address these limitations. Goals of RI-AIR were formulated in coordination with the RI-AIR Community Collaborative: a group of community partners involved in pediatric asthma care in Greater Providence (i.e., state agency representatives, caregivers of children with asthma, physicians and specialists caring for children with asthma).

A central goal throughout RI-AIR implementation was to promote health equity by improving individual and community-level asthma control and improving modifiable factors related to urgent healthcare utilization (ED visits, hospitalizations). The PRECEDE-PROCEED model was used as a theoretical framework [28] for the needs assessment. This model includes the PRECEDE (Predisposing, Reinforcing and Enabling Constructs in Educational Diagnosis and Evaluation) phase assessing social, health and behavioral determinants, and PROCEED (Policy, Regulatory, and Organizational Constructs in Educational and Environmental Development), identifying desired outcomes and program implementation [28]. Ultimately, RI-AIR aimed to provide an integrated system of care, increase communication among sectors of care, and improve the process of identification, screening, and referral based on level of control.

This manuscript describes our Hybrid Type II effectiveness-implementation trial [29]. A Hybrid Type II study enables researchers to simultaneously evaluate the effectiveness of a clinical intervention while assessing feasibility and implementation in a community setting [29]. Our ongoing assessment of facilitators and barriers during the trial was informed by the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR [30]; a framework of implementation determinants and constructs across five domains associated with implementation success), and our implementation outcomes were consistent with the RE-AIM model [31], a framework to guide the planning and evaluation of programs according to five key outcomes: Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance. The specific aims of RI-AIR were to evaluate: (1) the effectiveness of RI-AIR on individual-level asthma outcomes (e.g., asthma control), (2) the effectiveness of RI-AIR on community-level outcomes (e.g., urgent healthcare utilization), and (3) implementation in the community. This paper reports the RI-AIR protocol, design decisions, and recruitment efforts.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study setting and design

Our original design proposed recruiting 1500 children with asthma and caregivers from 16 school-based areas (i.e., polygons) with the highest urgent asthma healthcare utilization in Providence, Central Falls, and Pawtucket, R.I. High-burden areas were identified using geospatial mapping of hospital data (i.e., asthma-related ED and inpatient visits from 2010 to 2015). A Stepped Wedge Design (SWD) was used; school-based polygons received the intervention at different time points [32] and the order in which areas received the treatment was randomized.

Data collection began in November 2018 (year 1) in five polygons. We expanded to another high-burden city (Woonsocket) due to recruitment challenges during year 2 and identified four new comparable polygons from our original cities to be randomized to years 2 and 3. In January 2020, we revised our recruitment target to 730 with consultation and approval from our statistician and Data and Safety Monitoring Board due to recruitment barriers (e.g., families’ high level of overall burden, overburdened schools with limited time/resources for research, lower yield from EHR data pulls and participating schools, a higher rate of families that were harder to reach or uninterested in participating). We re-assessed current, urgent healthcare utilization in these areas through geospatial mapping of recent hospital data from 2018, identified 12 additional polygons, and added another high-burden city (Cranston). We received approval for an additional trial year; at this point all remaining schools were re-randomized to years 3 and 4 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

CONSORT diagram on the site level.

This resulted in 4 cohorts of 32 polygons; each had an active year during years 2–5 (see Table 1). All families with eligible children were offered evidence-based asthma management intervention(s) during their school-based polygon’s active trial year. Children with Poorly Controlled (PC) asthma and caregivers were assigned to the home-based intervention program (HARP) and school-based program (CASE); children with Not Well Controlled (NWC) asthma and caregivers were assigned to CASE only.

Table 1.

Stepped wedge design of RI-AIR.

| |

School Allocation | Year of Implementation |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 | Year 5 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Cohort 1 | 5 School-based polygons | Baseline 0 | Active Trial | Follow-Up | ||

| Cohort 2 | 8 School-based polygons | Baseline-1 | Baseline 0 | Active Trial | Follow-Up | |

| Cohort 3 | 13 School-based polygons | Baseline-2 | Baseline-1 | Baseline 0 | Active Trial | Follow-Up |

| Cohort 4 | 6 School-based polygons | Baseline-3 | Baseline-2 | Baseline-1 | Baseline 0 | Active Trial |

Note. This table illustrates the study’s Stepped Wedge Design (SWD). Using geospatial mapping, 32 school-based polygons with the highest levels of urgent asthma healthcare utilization in the Greater Providence area were identified, based on hospital data including asthma-related ED/inpatient visit rates. The SWD utilizes cluster-based randomization, which in this study was conducted on the community-level based on these school-based polygons.

2.2. Participants

Inclusion criteria included children who: (1) were between 2 and 12 years old, (2) lived and/or attended school in an identified polygon, (3) met criteria for physician-diagnosed asthma or probable asthma (for 2–5 year olds), (4) had a caregiver willing to participate who spoke English or Spanish, and (5) had asthma that was considered NWC or PC. Asthma control was determined using an algorithm that included urgent healthcare utilization and caregiver report of symptoms based on national guidelines [33]. NWC asthma was defined by daytime symptoms, quick-relief medication use, or activity limitation greater than twice per week, or any nighttime symptoms in the last 14 days. PC asthma was characterized by daily daytime symptoms, quick-relief medication use, or activity limitation or nighttime symptoms greater than twice per week in the past 14 days, or high urgent healthcare utilization (i.e., ≥ 2 ED visits or 1 inpatient hospitalization in the past year). Exclusion criteria included the diagnosis of complex medical conditions.

2.3. Procedures

Study procedures were approved by the local IRB. Eligibility screening occurred during polygons’ active trial year and throughout the year. Recruitment sites were elementary schools and preschools within these 32 polygons, and the ED, inpatient units, and asthma clinic of Hasbro Children’s Hospital (HCH). Daily referral lists were generated from the HCH electronic health record (EHR) system based on age, asthma-related encounter diagnoses (i.e., ICD-10-CM codes), asthma medication prescription(s), and home address. Participating schools provided lists of potential participants. Referrals could also be received from other avenues (e.g., direct referrals from community providers). Referrals were screened based on home addresses to confirm residence in an active polygon. The RI-AIR Information Data System (IDS) integrated referral lists from the ED, ambulatory clinics, and schools. Staff screened families via phone to determine initial eligibility. Participant intervention assignment was completed in coordination with the RI-AIR IDS that determined children’s level of control (i.e., NWC, PC).

Informed consent procedures and questionnaires were completed during a baseline visit. Staff employed multiple retention strategies (e.g., consistent staff member working with each family) to increase engagement and minimize burden. See Fig. 2 for a timeline of recruitment efforts and Table 2 for information on participant assignment.

Fig. 2.

RI-AIR intervention timeline.

Table 2.

Intervention assignment based on asthma control.

| For Families of Children Ages 2–5 | For Families of Children Ages 6–12 | School-Level Intervention | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Poorly Controlled | Caregiver receives: HARP Program AND CASE Program | Caregiver receives: HARP Program AND CASE Program Child receives: CASE Program |

School receives: CASE Staff Training AND CASE Environmental Assessment |

| Not Well Controlled | Caregiver receives: CASE Program | Caregiver receives: CASE Program Child receives: CASE Program | |

Note. This table represents the assignment of families of children with asthma in the study to a home-based asthma management education program (HARP) and a school-based asthma education program (CASE). Families were assigned based on their child’s age and asthma symptoms (i.e., Poorly Controlled and Not Well Controlled). Not Well Controlled was defined by daytime symptoms, quick-relief medication use, or activity limitation greater than twice per week, or any nighttime symptoms in the last 14 days. Poorly Controlled was defined by daily daytime symptoms, quick-relief medication use, or activity limitation or nighttime symptoms greater than twice per week in the past 14 days, or high urgent healthcare utilization (i.e., ≥ 2 ED visits or 1 inpatient hospitalization in the past year). All elementary schools in each polygon were assigned to receive CASE staff training and environmental assessment.

2.4. Interventions

2.4.1. Intervention team

The intervention team was comprised of English-speaking and Spanish-English bilingual staff. Liaisons ensured the implementation of approved programs, and facilitated communication between the research/intervention teams, community partners, and school personnel. The recruitment coordinator organized and was primarily responsible for recruitment efforts. Asthma educators provided asthma management education during HARP visits and CASE classes and facilitated coordination of care between healthcare providers and school nurse teachers. Asthma educators who had not yet obtained certification were supervised by a Certified Asthma Educator (AE-C). CHWs collaborated with asthma educators to administer the interventions: conducting home walk-throughs, assisting with obtaining Asthma Action Plans (AAP), and providing resources and referrals for families.

2.4.2. HARP: Home-based program

HARP is an intensive, home-environmental intervention consisting of three home visits occurring over approximately six weeks. HARP included (1) individualized, guidelines-based asthma management education provided to the caregiver, (2) a home-environmental assessment, (3) strategies for trigger remediation, (4) supplies for controlling environmental asthma triggers (e.g., mattress cover, vacuum), and (5) coordinated referrals as needed to local agencies to address social determinants of health.

During the first visit, an Asthma Educator and CHW completed a detailed home environmental walk-through to identify potential asthma triggers. Staff provided asthma education and self-management strategies to caregivers using a structured protocol and low-literacy flipbook in English or Spanish. Families defined problem areas impacting asthma management (e.g., smoking cessation challenges for individuals in the home, financial insecurity affecting ability to obtain medications). Education included information about environmental triggers, asthma symptoms, using an AAP, controller and quick-relief medications, and the importance of communication with the child’s support team (e.g., medical provider, teachers, family, friends). Staff reviewed environmental remediation strategies and offered referrals and advocacy information to address management barriers (e.g., communication with housing authorities about code violations) and other problems identified by families. Supplies for environmental remediation of asthma triggers were provided in the second session. During the third session, approximately one month later, the CHW conducted another home walk-through to assess remaining triggers, review progress on prior goals, address questions, re-assess problem areas, and provide additional referrals, as needed.

2.4.3. CASE: School-based program

The multi-level school-based CASE intervention included groups with (1) school-aged children with PC or NWC asthma, (2) caregivers of these children, and (3) school staff. All educational groups were facilitated by an Asthma Educator and/or CHW, occurred over approximately four weeks, and occurred twice during the school year for each polygon. Program curricula were guidelines-based [34] and families were provided with educational materials (e.g., summaries of topics covered, tip sheets). Asthma knowledge was assessed before and after caregiver, child, and school staff programs, and interviews with school nurse teachers were conducted pre- and post-CASE programs to assess school-level policies and needs, families’ needs within specific school communities, and potential barriers and facilitators to RI-AIR implementation within schools.

Child education program.

Programs for children 6–12 years old consisted of a 60-min presentation, group discussion, and interactive activities administered in the school setting. The curriculum included discussion of asthma management challenges in urban settings, asthma facts and pathophysiology, identifying and responding to asthma symptoms, asthma triggers, medications and their purposes, a demonstration of inhalers and spacers, and strategies for school asthma management.

Caregiver education program.

After-school caregiver education programs included a 60-min presentation and group discussion. Topics included those from the child program and the importance of collaboration with school nurses and clinical providers. Caregivers of preschool-aged children could attend the program at the elementary school closest to their home (within their polygon), as no caregiver education programs were conducted in preschools. Classes were offered in English or Spanish.

School staff training.

All school staff were invited to attend a 30–60-min group training based on national school management guidelines [34]. Programs covered asthma’s impact on learning and physical activity, the importance of identifying children with asthma, supporting the identification and response to symptoms, asthma triggers and medications, medication administration and spacer use, and the importance of collaborations between school staff, nurses, and caregivers for school-based asthma management. See Fig. 3 for more information.

Fig. 3.

Overview of the RI-AIR program.

2.4.4. Communication across sectors of care

Program staff assisted in enhancing communication and coordinating asthma care between caregivers, school nurses, and healthcare providers across interventions. The intervention team notified the child’s healthcare provider and nurse of their study enrollment and provided a report documenting baseline level of asthma control. The child’s AAP was obtained from the healthcare provider and reviewed with the family; if one did not exist, the CHW worked with the provider to develop an AAP. The CHW uploaded the AAP to KIDSNET, R.I.’s confidential, computerized child health information system accessible by healthcare providers and school nurses. The intervention team notified school nurses when AAPs had been uploaded and provided guidance for accessing them. At the end of treatment, letters were sent to healthcare providers and school nurses to summarize children’s symptoms and progress. Following study completion (i.e., at the 12-month follow-up), a final letter documenting the child’s asthma control level was sent to the healthcare provider and school nurse. Updates were provided to medical providers and school nurses at study enrollment, intervention completion, and follow-up and included information about the interventions, AAP, asthma control level, and key findings.

2.4.5. Changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic

IRB-approved modifications were instituted due to the COVID-19 pandemic. All paperwork (e.g., consent forms) was converted to a digital format and a HIPAA-compliant video conferencing platform was used for research visits, HARP home walk-throughs, and CASE programs. Curricula were modified to increase engagement for remote delivery. Phone visits were used for follow-up appointments and the delivery of HARP supplies to homes aligned with HCH’s protective measures and policies. Sessions were offered at flexible times given the pandemic’s impact on families’ schedules. Remote CASE programs for children and caregivers were opened to participants across schools. CASE school staff trainings were conducted remotely via live video-conferencing presentation and/or a recorded webinar based on school preference.

2.5. Outcomes and measures

All measures (see Table 3) were administered in English or Spanish.

Table 3.

RI-AIR outcomes and measures.

| Measures and Outcomes | Level | Measure Description | Administration Timepoint |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Asthma Control | Primary-Individual | Test for Respiratory and Asthma Control (2–4 year olds) or Childhood Asthma Control Test (5–12 year olds) [35,36] | Baseline; End of Treatment; 3, 6, 9, and 12 Month Follow Ups |

| Asthma Symptom Free Days | Secondary-Individual | Caregiver report using a standard questionnaire item, Symptom Free Days (SFDs) within previous 30-day period [37] | Baseline; End of Treatment; 3, 6, 9, and 12 Month Follow Ups |

| Asthma Management Efficacy | Secondary-Individual | Caregiver report of the Asthma Management Efficacy Questionnaire [38] | Baseline, End of Treatment, & 12 Month Follow Up |

| Caregiver Quality of Life related to Asthma | Secondary-Individual | Caregiver report using the Pediatric Asthma Caregiver’s Quality of Life Questionnaire [39] | Baseline; End of Treatment; 3, 6, 9, and 12 Month Follow Ups |

| Individual-level Asthma Health Care Utilization | Secondary-Individual | Caregiver report and EHR record of urgent healthcare utilization (ED and inpatient visits) for asthma each active trial year | Baseline & 12 Month Follow Up |

| Individual-level School Absences | Secondary-Individual | Days missed for children from each of the school-based polygons who participated in each active trial year, obtained through school records and caregiver report | Baseline & 12 Month Follow Up |

| Asthma Health Care Utilization | Community | Hospital-based data on urgent healthcare utilization (rates of ED visits and inpatient hospitalizations for asthma) in each school-based polygon | Baseline & 12 Month Follow Up |

| School Absences | Community | School records of children’s school attendance across the academic year (all children in each school) in each school-based polygon (one school per polygon) | End of Each School Year |

| Reach within Polygons | Process Evaluation | RI-AIR IDS was used to monitor recruitment, enrollment, and retention. | Years 2–5 |

| Fidelity of RI-AIR IDS Platform | Process Evaluation | Monitored using dynamic data pulls weekly (beginning of recruitment) and quarterly (each active intervention year). Quality control assessments were incorporated each active year. | Years 2–5 |

| Implementation Fidelity of the Treatment Protocol | Process Evaluation | Assessed by monitoring and evaluating audio recordings of interventions using a standard checklist. Co-Is observed 10% of HARP visits and CASE classes during years 2–4 and provided feedback. Dose delivered was the number of sessions participants received. | Years 2–5 |

| Intervention Completion Rates | Process Evaluation | HARP completion: completion of at least the first 2 inhome intervention sessions. CASE completion: provision of staff training (school level) and caregiver or child CASE programs (family level) | Years 2–5 |

| Changes in Asthma Management Indicators | Process Evaluation |

HARP: Changes in asthma knowledge, asthma management, and exposure to asthma triggers. CHWs assessed whether (1) there was an AAP present in the home, (2) the medications listed on the AAP were in the home, (3) caregiver could demonstrate the correct inhaler technique, and (4) caregiver could use the AAP to describe which medications to use; CASE: Changes in caregiver, child, and school staff asthma knowledge (pre to post CASE programs) and asthma management indicators (whether AAP was uploaded to KIDSNET and viewed by nurse) |

Baseline, End of Treatment |

| Barriers and Facilitators to Implementation | Implementation | Assessed using multiple methods: interviews with school nurses, surveys of school personnel (nurses, principals), ongoing feedback from CHWs, focus groups with caregivers, debrief meetings with CHWs, and medical provider surveys. | Years 2–5 |

| Return on Investment | Implementaton | Return on investment (i.e., the cost of the intervention) will be evaluated by estimating the cost of program implementation (direct and indirect costs) relative to healthcare cost reduction. Healthcare expenses will be derived from claims data (asthma office visits, ED use, inpatient days). |

12 Months Pre- and Post-intervention |

| Demographic Information | Other-Individual | Caregiver report of child age, sex, race, ethnicity, household income, number of adults and children in the household, caregiver education level, and language spoken. | Baseline |

Note. This table illustrates the study’s primary and secondary individual and community level outcomes. Process evaluation and implementation outcomes are also presented. All study visits were home-based or conducted remotely after the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. EHR = electronic health record; ED = emergency department; Co-Is = Co-Investigators.

2.5.1. Effectiveness outcomes

Asthma control level was the primary effectiveness outcome. Individual-level secondary effectiveness outcomes included symptom free days, asthma management efficacy, caregiver quality of life, child urgent healthcare utilization, and child school absences. Community-level secondary effectiveness outcomes included community urgent healthcare utilization and community school absences.

2.5.2. Multi-level process evaluation and primary implementation outcomes

A multi-level process evaluation of RI-AIR during implementation was conducted. Barriers and facilitators to implementation were assessed using multiple methods. Process evaluation determinants included reach within polygons, fidelity of RI-AIR IDS, implementation fidelity of the treatment protocol, intervention completion rates, and changes in asthma management indicators. Implementation outcomes, as guided by the RE-AIM model, were also assessed. Reach was assessed using RI-AIR IDS as an index of penetration to monitor recruitment, enrollment, and retention. Effectiveness was assessed through quantitative outcomes as noted above. Adoption was examined using an index of engagement (i.e., intervention completion rates, number of school staff attending CASE trainings) and implementation was examined by investigating barriers and facilitators to implementation and the return on investment (i.e., cost of program implementation relative to reduction in healthcare cost). Lastly, maintenance and sustainability of effects will be examined at 12-month follow-up sessions and is ongoing.

3. Results

3.1. Recruitment

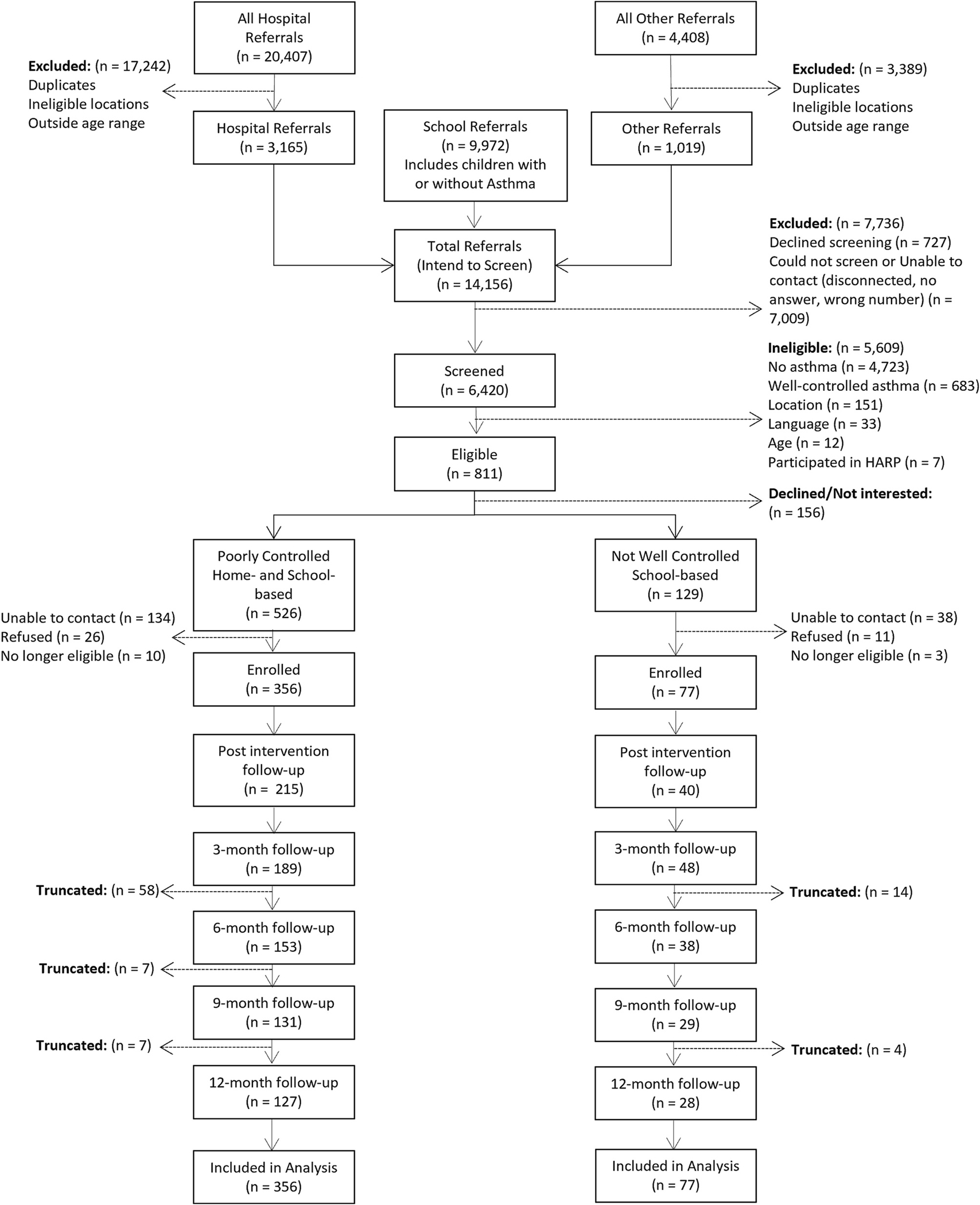

Recruitment occurred between November 2018 and December 2021. The COVID-19 pandemic began in the middle of year 2, and the transition to virtual services began August 2020. HARP and CASE interventions ended February 2022. A total of 433 children were enrolled (13% Black/African American, 19% White, 9% More than one race, 31% Other, 26% Not sure/Did not answer, 74% Hispanic). See Fig. 4 for a CONSORT diagram (participant level). There were no demographic or medical differences between families who enrolled and those who declined or were excluded (i.e., academic grade, asthma control level, age) apart from primary language spoken in the home. Forty-six percent of families who enrolled in RI-AIR reported Spanish as their primary language compared to 28% of those who declined or were excluded (p < .001).

Fig. 4.

CONSORT diagram on the participant level.

3.2. Proposed statistical analyses

Data cleaning and preparation is ongoing. We outline our proposed statistical analyses below.

3.2.1. Sample size and power analyses

Our original projected enrollment was 1500 children nested within 16 polygons; this target was revised to 32 polygons and 730 children. Simulated power analyses assumed that trial year accounts for 1% of total variance, variance of the individual-level random intercept (Interclass Correlations; ICC) = 0.20, variance of catchment area random intercept ICC = 0.10, type-1 error of 0.05 and power 0.80. Simulations indicated that the study is powered to detect a standardized difference of 0.13 (pre vs. 3-month) and 0.14 (pre vs. follow-up).

For community-based outcomes, using ED visits prior to the intervention as the baseline, and assuming an average baseline ED visit rate of 0.07 and the variance of catchment area-level intercept of (ICC) = 0.33 (both estimated from historical records), 32 school-based catchment areas provides power to detect a rate ratio of 0.90 (difference of ~2.9 ED visits using average school enrollment [n = 410] as a denominator for the rate). For hospitalizations, assuming a baseline rate of 0.02, and area-level variance of (ICC) =0.39, we will have power to detect a rate ratio of 0.82 (~1.5 hospitalizations).

3.2.2. Individual-level outcomes

Individual-level outcomes will be analyzed using generalized linear mixed effect models (GLME) with clustering defined by the participant nested within community. Fixed effects will include a treatment contrast (pre-intervention vs. 3-months post intervention), study year (cohort), season, and a categorical covariate indicating the start of COVID-19 (03/16/20). Random effects for participant nested within community will include the intercept. The 3-month outcome will be the primary target; sustainment of effects across 12-months will also be examined. Published cut-offs will be used to classify controlled vs. not-controlled asthma at each assessment, and published MCIDs (cACT = 2-point change, TRACK = 10-point change [40]) will be used to classify participants as improved, maintained, or worsened. This analysis will be performed using a multinomial effect model. Secondary endpoints will be analyzed using similarly structured GLMEs. Link functions and distributions will be matched to the distribution of the outcome with a logit link with binomial distribution used for binary outcomes, log-link with Poisson distribution for count outcomes, and identity link with Gaussian distribution for normally distributed outcomes.

3.2.3. Community-level outcomes

Outcomes (i.e., asthma-related ED/hospitalization rates, school absenteeism) are available for the year prior to the start of the study through 6 months after the end of the last cohort. Pandemic effects on ED visits and hospitalizations are largely unknown; it is unclear when healthcare utilization increased again after reductions observed early in the pandemic. Seasonal influences on allergen exposure are also unknown. Given these uncertainties, we will use generalized additive mixed effect modeling to accommodate data-driven modeling of the temporal trends in ED visits and hospitalizations per month while accounting for nesting of months within polygon. This semi-parametric approach accounts for seasonality and COVID-related changes to ED and hospitalization rates while also providing a test of changes related to intervention period (Active/Post). The model will assume the same temporal pattern across the four step-wedge cohorts. We will fit the model using the r package mgcv version 1.8–40; it will be estimated using Penalized Quasi-Likelihood with a log link function and Poisson distribution. Fixed effects include a categorical covariate of intervention (i.e., pre, active, and post), study year (cohort), and the penalized splines for months since the start of RI-AIR. Random effects for communities will include the intercept for each polygon. Implementation outcomes (reach, treatment implementation fidelity, intervention completion, and changes in asthma management indicators) will be examined by school/cluster/wedge to determine the various impacts of the implementation context on effectiveness.

4. Discussion

Health disparities in pediatric asthma remain a critical public health problem [11,41,42]; however, few studies have examined the implementation of community-based interventions [43]. Development of RI-AIR, a comprehensive system of screening, identification, and intervention for pediatric asthma was informed by multiple sources: a needs assessment, feedback from community partners, statewide asthma-related healthcare utilization data, and results of previous research. The goal of RI-AIR was to evaluate the effectiveness of the HARP and CASE interventions on individual-level and community-level outcomes, and to assess real-world implementation. Balancing the evaluation of effectiveness and implementation facilitates the long-term goal of creating a model of care that can be disseminated to other urban areas to address asthma inequities.

Implementing effective and accessible interventions was critical given asthma health disparities in the Greater Providence area [2] and gaps in care identified by the community-based needs assessment. The home- and school-based services were chosen given prior research demonstrating improvement in health outcomes and appropriateness of risk stratification for intervention assignment (i.e., home-, school-based, or both) depending on the child’s asthma control level [16,17]. Accessibility was also enhanced by offering research and intervention procedures across settings and in both English and Spanish.

Multiple methods were used to increase the effectiveness of the intervention, including the role of the intervention team in coordinating communication between schools, healthcare providers, and families. Care coordination has been associated with decreased frequency of symptoms, lower healthcare utilization, and improved between-provider and patient-provider communication [44,45]. Family participation and support is associated with better health outcomes [46]; hence families’ active role in all procedures was a critical intervention component. In addition to meeting with families in familiar locations (i. e., home and school settings), CHWs and Asthma Educators provided asthma education and delivered the interventions. These staff, often from the local community, may have increased families’ comfort level and encouraged family members to participate actively. Utilization of risk stratification in intervention assignment and the comprehensive data system were additional strengths of RI-AIR.

Despite the strengths of effectiveness-implementation trials, there are challenges and limitations. While barriers and facilitators to implementation were assessed following families’ enrollment, it was challenging to assess why families or schools initially declined participation, or why some school staff did not attend CASE trainings. Additionally, information gathered from healthcare providers was limited given the voluntary nature of their participation and workload demands during a pandemic. Despite numerous retention strategies, some families were lost to follow up and reasons could not always be determined. This is particularly salient during the COVID-19 pandemic, as circumstances may have impacted families’ and schools’ willingness to participate, medical providers’ and school nurses’ response rate, increased participant stress and burden, dynamic living situations, and demands on caregivers’ time (e.g., balancing work, caregiving role[s], supervision of virtual schooling) [47,48]. Although all interventions were adapted to a virtual format, it was not feasible to capture all the ways in which the pandemic impacted the effectiveness and implementation of the interventions. We plan to describe the intervention and implementation adaptations in a separate manuscript. An additional consideration is the decreased sample size, although the planned analyses are still powered to detect changes. Identifying barriers and facilitators to sustainability once the study ends remains an important goal for future implementation.

Accessible and effective asthma interventions are necessary to reduce health inequities. The RI-AIR program could serve as a model for designing home- and school-based interventions for the diverse population of children with asthma. Future work following the completion of RI-AIR data collection will explore outcomes associated with completion of the HARP, CASE, and combined interventions, as well as identify lessons about effective implementation of asthma-related programs to increase community engagement and participation, especially during times of elevated stress and burden. Future work investigating the design and implementation of interventions targeting systemic healthcare factors (e.g., structural racism, insurance and healthcare access factors) are also needed to reduce health inequities.

Funding sources

The research presented was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) under the Award Number U01 HL138677. Coauthor A.R.E. is partially supported by Institutional Development Award Number U54GM115677 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, which funds Advance Clinical and Translational Research (Advance-CTR). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations:

- RI-AIR

Rhode Island Asthma Integrated Response

- PC

Poorly controlled

- NWC

Not well controlled

- CHW

Community health worker

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

No authors have competing interests to disclose.

Dedication

This manuscript is dedicated to the memory of our beloved colleague, Aris Garro, MD.

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- [1].Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Data, Statistics, and Surveillance: Most Recent National Asthma Data, Published May 26. Accessed November 15, 2022, https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_national_asthma_data.htm, 2022.

- [2].Rhode Island KIDS COUNT, Rhode Island Kids Count Factbook. https://www.rikidscount.org/Data-Publications/RI-Kids-Count-Factbook#843238-family-and-community, 2022.

- [3].Tay TR, Pham J, Hew M, Addressing the impact of ethnicity on asthma care, Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 20 (3) (2020) 274–281, 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Trivedi M, Fung V, Kharbanda EO, et al. , Racial disparities in family-provider interactions for pediatric asthma care, J. Asthma 55 (4) (2018) 424–429, 10.1080/02770903.2017.1337790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kaufmann J, Marino M, Lucas J, et al. , Racial and ethnic disparities in acute care use for pediatric asthma, Ann. Family Med. 20 (2) (2022) 116–122, 10.1370/afm.2771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Pino-Yanes M, Thakur N, Gignoux CR, et al. , Genetic ancestry influences asthma susceptibility and lung function among Latinos, J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 135 (1) (2015) 228–235, 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Koinis-Mitchell D, Kopel SJ, Salcedo L, McCue C, McQuaid EL, Asthma indicators and neighborhood and family stressors related to urban living in children, Am. J. Health Behav. 38 (1) (2014) 22–30, 10.5993/AJHB.38.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].McQuaid EL, Barriers to medication adherence in asthma: the importance of culture and context, Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 121 (1) (2018) 37–42, 10.1016/j.anai.2018.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Tackett AP, Farrow M, Kopel SJ, Coutinho MT, Koinis-Mitchell D, McQuaid EL, Racial/ethnic differences in pediatric asthma management: the importance of asthma knowledge, symptom assessment, and family-provider collaboration, J. Asthma 58 (10) (2021) 1395–1406, 10.1080/02770903.2020.1784191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Coutinho MT, McQuaid EL, Koinis-Mitchell D, Contextual and cultural risks and their association with family asthma management in urban children, J. Child Health Care 17 (2) (2013) 138–152, 10.1177/1367493512456109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Canino G, Garro A, Alvarez MM, et al. , Factors associated with disparities in emergency department use among Latino children with asthma, Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 108 (4) (2012) 266–270, 10.1016/j.anai.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Canino G, Vila D, Normand SLT, et al. , Reducing asthma health disparities in poor Puerto Rican children: the effectiveness of a culturally tailored family intervention, J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 121 (3) (2008) 665–670, 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bellin MH, Land C, Newsome A, et al. , Caregiver perception of asthma management of children in the context of poverty, J. Asthma 54 (2) (2017) 162–172, 10.1080/02770903.2016.1198375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Laster N, Holsey CN, Shendell DG, Mccarty FA, Celano M, Barriers to asthma management among urban families: caregiver and child perspectives, J. Asthma 46 (7) (2009) 731–739, 10.1080/02770900903082571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Prather SL, Foronda CL, Kelley CN, Nadeau C, Prather K, Barriers and facilitators of asthma management as experienced by African American caregivers of children with asthma: an integrative review, J. Pediatr. Nurs. 55 (2020) 40–74, 10.1016/j.pedn.2020.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Fidler A, Sweenie R, Ortega A, Cushing CC, Ramsey R, Fedele D, Meta-analysis of adherence promotion interventions in pediatric asthma, J. Pediatr. Psychol. 46 (10) (2021) 1195–1212, 10.1093/jpepsy/jsab057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Harris K, Kneale D, Lasserson TJ, McDonald VM, Grigg J, Thomas J, School-based self-management interventions for asthma in children and adolescents: a mixed methods systematic review, Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. (2019) 1, 10.1002/14651858.CD011651.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bryant-Stephens T, Williams Y, Kanagasundaram J, Apter A, Kenyon CC, Shults J, The West Philadelphia asthma care implementation study (NHLBI# U01HL138687), Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 24 (2021), 100864, 10.1016/j.conctc.2021.100864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Everhart RS, Mazzeo SE, Corona R, Holder RL, Thacker LR, Schechter MS, A community-based asthma program: study design and methods of RVA breathes, Contemp. Clin. Trials 97 (2020), 106121, 10.1016/j.cct.2020.106121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Naar S, Ellis D, Cunningham P, et al. , Comprehensive community-based intervention and asthma outcomes in African American adolescents, Pediatrics. 142 (4) (2018), e20173737, 10.1542/peds.2017-3737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].DePue JD, McQuaid EL, Koinis-Mitchell D, Camillo C, Alario A, Klein RB, Providence school asthma partnership: school-based asthma program for Inner-City families, J. Asthma 44 (6) (2007) 449–453, 10.1080/02770900701421955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Fedele DA, Koinis-Mitchell D, Kopel S, Lobato D, McQuaid EL, A community-based intervention for Latina mothers of children with asthma: what factors moderate effectiveness? Children’s Health Care 42 (3) (2013) 248–263, 10.1080/02739615.2013.816605. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Koinis-Mitchell D, McQuaid EL, Friedman D, et al. , Latino Caregivers’ beliefs about asthma: causes, symptoms, and practices, J. Asthma 45 (3) (2008) 205–210, 10.1080/02770900801890422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Koinis-Mitchell D, McQuaid EL, Jandasek B, et al. , Identifying individual, cultural and asthma-related risk and protective factors associated with resilient asthma outcomes in urban children and families, J. Pediatr. Psychol. 37 (4) (2012) 424–437, 10.1093/jpepsy/jss002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Koinis-Mitchell D, Sato AF, Kopel SJ, et al. , Immigration and acculturation-related factors and asthma morbidity in Latino children*, J. Pediatr. Psychol. 36 (10) (2011) 1130–1143, 10.1093/jpepsy/jsr041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Jandasek B, Ortega AN, McQuaid EL, et al. , Access to and use of asthma health services among Latino children: the Rhode Island-Puerto Rico asthma center study, Med. Care Res. Rev. 68 (6) (2011) 683–698, 10.1177/1077558711404434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].McQuaid EL, Everhart RS, Seifer R, et al. , Medication adherence among Latino and non-Latino white children with asthma, Pediatrics. 129 (6) (2012) e1404–e1410, 10.1542/peds.2011-1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Green LW, Toward cost-benefit evaluations of health education: some concepts, methods, and examples, Health Educ. Monogr. 2 (1_suppl) (1974) 34–64, 10.1177/10901981740020S106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C, Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact, Med. Care 50 (3) (2012) 217–226, 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC, Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science, Implement. Sci. 4 (1) (2009) 50, 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM, Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework, Am. J. Public Health 89 (9) (1999) 1322–1327, 10.2105/AJPH.89.9.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Copas AJ, Lewis JJ, Thompson JA, Davey C, Baio G, Hargreaves JR, Designing a stepped wedge trial: three main designs, carry-over effects and randomisation approaches, Trials. 16 (1) (2015) 352, 10.1186/s13063-015-0842-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].National Asthma Education and Prevention Program, Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma, US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- [34].National Asthma Education, Prevention Program (National Heart, Lung, & Blood Institute), Managing Asthma: A Guide for Schools, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Education, 2003. Editors. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Liu AH, Zeiger R, Sorkness C, et al. , Development and cross-sectional validation of the childhood asthma control test, J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 119 (4) (2007) 817–825, 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.12.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Murphy KR, Zeiger RS, Kosinski M, et al. , Test for respiratory and asthma control in Kids (TRACK): a caregiver-completed questionnaire for preschool-aged children, J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 123 (4) (2009) 833–839.e9, 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Krishnan JA, Lemanske RF, Canino GJ, et al. , Asthma outcomes: symptoms, J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 129 (3, Supplement) (2012) S124–S135, 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.12.981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Bursch B, Schwankovsky L, Gilbert J, Zeiger R, Construction and validation of four childhood asthma self-management scales: parent barriers, child and parent self-efficacy, and parent belief in treatment efficacy, J. Asthma 36 (1) (1999) 115–128, 10.3109/02770909909065155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Ferrie PJ, Griffith LE, Townsend M, Measuring quality of life in the parents of children with asthma, Qual. Life Res. 5 (1) (1996) 27–34, 10.1007/BF00435966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Dinakar C, Chipps BE, Clinical tools to assess asthma control in children, Pediatrics 139 (1) (2017), e20163438, 10.1542/peds.2016-3438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Bryant-Stephens T, Asthma disparities in urban environments, J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 123 (6) (2009) 1199–1206, 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Crocker D, Brown C, Moolenaar R, et al. , Racial and ethnic disparities in asthma medication usage and health-care utilization: data from the National Asthma Survey, Chest. 136 (4) (2009) 1063–1071, 10.1378/chest.09-0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Chan M, Gray M, Burns C, et al. , Community-based interventions for childhood asthma using comprehensive approaches: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Allergy, Asthma Clin. Immunol. 17 (1) (2021) 19, 10.1186/s13223-021-00522-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Janevic MR, Stoll S, Wilkin M, et al. , Pediatric asthma care coordination in underserved communities: a Quasiexperimental study, Am. J. Public Health 106 (11) (2016) 2012–2018, 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Janevic MR, Baptist AP, Bryant-Stephens T, et al. , Effects of pediatric asthma care coordination in underserved communities on parent perceptions of care and asthma-management confidence, J. Asthma 54 (5) (2017) 514–519, 10.1080/02770903.2016.1242136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Rhee H, Belyea MJ, Brasch J, Family support and asthma outcomes in adolescents: barriers to adherence as a mediator, J. Adolesc. Health 47 (5) (2010) 472–478, 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Browne DT, Wade M, May SS, Jenkins JM, Prime H, COVID-19 disruption gets inside the family: a two-month multilevel study of family stress during the pandemic, Dev. Psychol. 57 (2021) 1681–1692, 10.1037/dev0001237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Hoke AM, Pattison KL, Molinari A, Allen K, Sekhar DL, Insights on COVID-19, school reopening procedures, and mental wellness: pilot interviews with school employees, J. Sch. Health 92 (11) (2022) 1040–1044, 10.1111/josh.13241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.