Abstract

Magnetic MnFe2O4 nanoparticles were successfully prepared by the rapid combustion method at 500 °C for 2 h with 30 mL absolute ethanol, and were characterized by SEM, TEM, XRD, VSM, and XPS techniques, their average particle size and the saturation magnetization were about 25.3 nm and 79.53 A·m2/kg, respectively. The magnetic MnFe2O4 nanoparticles were employed in a fixed bed experimental system to investigate the adsorption capacity of Hg0 from air. The MnFe2O4 nanoparticles exhibited the large adsorption performance on Hg0 with the adsorption capacity of 16.27 μg/g at the adsorption temperature of 50 °C with the space velocity of 4.8×104 h-1. The VSM and EDS results illustrated that the prepared MnFe2O4 nanoparticles were stable before and after adsorption and successfully adsorbed Hg0. The TG curves demonstrated that the mercury compound formed after adsorption was HgO, and both physical and chemical adsorption processes were observed. Magnetic MnFe2O4 nanoparticles revealed excellent adsorbance of Hg0 in air, which suggested that MnFe2O4 nanoparticles be promising for the removal of Hg0.

1. Introduction

Mercury is harmful to ecosystems because of its long-range transport, persistence, and bioaccumulation [1–3]. Mercury can undergo various stages of transformation to produce methylmercury (MeHg), a highly toxic form of mercury, the ingestion of which can have adverse effects on human health [4]. The increasing concentration of mercury in the environment has attracted the attention of governments and environmental organizations, and has become a worldwide environmental problem. The Minamata Convention on mercury, which entered into force in 2017, emphasizes cost-effective abatement and efficient decontamination of mercury pollution, as well as the sound management and utilization of mercury-rich waste [5]. Coal-fired power plants are reported to be the most significant source of mercury emissions, so in response to this problem, the Emission Standards for Air Pollutants from Power Plants (GB 132232011), published in July 2011, for the first-time limit mercury emission concentrations to no more than 0.03 mg/m3 of mercury and mercury compounds from coal-fired power plants [6].

Mercury in coal combustion flue gas exists in three main forms: elemental mercury (Hg0), oxidized mercury (Hg2+), and particulate bound mercury (Hgp) [7–9]. Hg2+ is water soluble and volatile, can be readily adsorbed and removed via a wet scrubber process. HgP is susceptible to adsorption and charging, it has a short residence time in the atmosphere, and it is easily removed by electric precipitators. Since Hg0 is highly volatile and almost insoluble in water, where it remains in the atmosphere for 0.5–2 years. More importantly, Hg0 is one of the most difficult form to control, and it is challenging to remove mercury from coal-fired flue gases [10].

Catalysis and adsorption methods are the main methods for the removal of elemental mercury [11–14]. In recent years, various catalysts and adsorbents have been reported for mercury removal, such as activated carbon, precious metals, and metal oxides [8, 15, 16]. Among them, magnetic ferrite nanomaterials are a new type of material that offers the advantages of easy separation, recyclability, and environmental friendliness, so they have been widely applied in organic and biological separations. Especially, they are excellent adsorbents due to their large specific surface area, abundant active sites, and interfacial effect [17–19]. Simultaneously, manganese oxides can impact the mercury cycle by adsorbing it, influencing the ambient redox potential and regulating microorganism activity. Therefore, MnFe2O4 is recognized as an excellent adsorbent for removing singlet Hg from coal-fired flue gases. To enhance the removal performance of MnFe2O4 nanoparticles, researchers have proposed several constructive ideas, such as applying organic or inorganic layers to coat the surface of nanomaterials [20–22], modifying the structural composition and morphology parameters [23], and doping transition metals [24].

Various approaches are available for the preparation of magnetic nanomaterials, such as co-precipitation [25], hydrothermal methods [26], rapid combustion methods [27], and so on. The birdnesting and the nonuniformity of composition are the largest problem owing to the accession of precipitant. While, magnetic nanoparticles prepared by hydrothermal method have long cycle time and small yield. The rapid combustion method has a short preparation cycle, low cost, safe, reliable, and environmentally friendly process, it is easy to produce industrially, and it can achieve the purpose of controlling the sizes and properties of magnetic nanoparticles by changing the amount of solvent and calcination temperature [28–30]. And the application of adsorbents prepared by this method for the removal of elemental mercury from coal combustion flue gas has not been reported.

In this paper, magnetic MnFe2O4 nanomaterials were prepared from metal nitrates by a rapid combustion method based on the ability of manganese compounds to oxidize mercury, and the factors (volume of anhydrous ethanol and calcination temperature) affecting their adsorption properties were optimized. The mercury removal performance of the magnetic MnFe2O4 nanomaterials was evaluated in a fixed bed system. Combined with vibrating sample magnetometry (VSM), energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) mapping, and thermogravimetric (TG) curves, the mercury removal process was analyzed.

2. Experiment details

2.1 Preparation and characterization of magnetic MnFe2O4 nanoparticles

Magnetic MnFe2O4 nanoparticles were prepared via the rapid combustion process, typically, Fe(NO3)3·9H2O and Mn(NO3)2·6H2O were dissolved into 30 mL absolute ethanol according to 1:2 molar ratio of them to form a homogeneous solution, ignited and burned until extinguished, and calcinated at 400–800 °C for 2 h with the heating rate of 3 °C/min to obtain magnetic MnFe2O4 nanoparticles. In the rapid combustion process, anhydrous ethanol acted as both a dispersant and a fuel, effectively dispersing the solute while serving as a catalyst for combustion. The product obtained at the end of the combustion of the solution incompletely formed MnFe2O4 crystals in a sol state. Subsequently, the semi-finished product was transferred to the temperature-controlled furnace programmed for high-temperature calcination. The purpose of this process was to provide sufficient heat for inducing the formation of MnFe2O4 nanoparticles and removed impurities such as activated carbon and nitrate.

The microscopic morphology and elemental distribution of MnFe2O4 nanomaterials were characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS). The physical phase and crystallinity were analyzed through X-ray diffractometer (XRD). Vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM) was employed to measure the hysteresis loops of MnFe2O4 nanoparticles before and after adsorption. The formation of the products in the adsorption process was determined by a thermogravimetric curve (TG).

2.2 Elemental mercury adsorption experiments

The actual coal combustion flue gas contains a variety of gases such as N2, CO2, O2, and SO2. The influence of the various gases on the removal of mercury was complex, and considering that most of the flue gas was N2, only N2 was chosen for the experiments (Fig 1). The gas flow rate was controlled by a rotameter and adjusted according to the experimental requirements. Various concentrations of mercury vapors were produced by means of a heated mercury permeation tube. The adsorbent was packed in a U-shaped tube with an inner diameter of 5 mm. To prevent the adsorbent from falling or being blown up by the gas, cotton was inserted at both ends for support and fixation. All experimental piping and connections were made of poly tetra fluoroethylene (PTFE). The tail gas after the reaction is purified with 10% H2SO4-4% KMnO4 absorption solution and discharged. Once adsorbed, the solid nanoparticles were detected by means of DMA-80 mercury analyzer. The experimental data were obtained after three experiments.

Fig 1. Simple diagram of a fixed bed experimental setup.

3. Results and discussion

3.1 Characterization of magnetic MnFe2O4 nanoparticles

Fig 2 showed the SEM morphology, TEM image, XRD pattern, and XPS spectra of the MnFe2O4 nanomaterials calcinated at 500 °C for 2 h with 30 mL absolute ethanol. As shown in Fig 2A (S1 Fig), the morphology of the prepared MnFe2O4 nanomaterials exhibited a granular shape with an average particle size of about 25.3 nm. The TEM image was shown in Fig 2B (S2 Fig), the measured morphology was granular and the average particle size was also around 25.3 nm, which was in general agreement with the observation from SEM morphology. The excellent nano-size made the adsorption capacity extraordinarily large, making it an excellent choice for absorbing Hg0. XRD pattern of MnFe2O4 nanoparticles was shown in Fig 2C (S3 Fig), the characteristic peaks were 29.62°, 34.82°, 43.13°, 62.29°, and 74.34°, corresponding to the (220), (311), (400), (440), and (622) crystalline planes of the MnFe2O4 standard card (JCPDS No. 10–0319), which proved that the MnFe2O4 nanoparticles were prepared successfully [31]. The prepared nanomaterials possessed four components, Mn, Fe, O, and C, as could be seen from the XPS maps (Fig 2D, S4 Fig), which again demonstrated the successful preparation of MnFe2O4 nanoparticles.

Fig 2. (A) SEM morphology, (B) TEM image, (C) XRD pattern, and (D) XPS spectra of magnetic MnFe2O4 nanoparticles obtained by calcination at 500 °C for 30 mL of absolute ethanol for 2 h.

3.2 Effects of preparation factors for MnFe2O4 nanoparticles on Hg0 adsorption

To understand the effect of MnFe2O4 nanoparticles prepared with different alcohol volumes and calcination temperatures on the performance of the mercury removal, it was investigated by a fixed bed experimental system [32].

Anhydrous ethanol was essential in the rapid combustion process, which not only played a role in distributing to the solute and ignition, but also effectively controlled the duration of combustion. As could be seen from Fig 3A (S1 Table), when experimental conditions were controlled at permeation temperature of 40 °C, space velocity of 4.8×104 h-1, and adsorption temperature of 30 °C, the adsorption capacity of Hg0 increased slowly with the volume of alcohol for the preparation of MnFe2O4 nanoparticles increasing of from 15 mL to 25 mL, and when the absolute alcohol volume rose to 30 mL, a significant increase of the adsorption capacity could be seen. The reason for this phenomenon might be that the large volume of anhydrous ethanol caused the solute to be dispersed excessively in the solvent, resulting in the formation of smaller grain sizes. However, as the volume of anhydrous ethanol increased further, the adsorption capacity tended to decrease. This might be attributed that the large amount of anhydrous ethanol dispersed the solute, while also prolonging the combustion time. As a result, there was a greater degree of sintering, leading to larger grain size and decreases in specific surface area and adsorption capacity [33]. Therefore, 30 mL was chosen as the optimum volume of absolute alcohol.

Fig 3. Adsorption curves of Hg0 by MnFe2O4 nanoparticles prepared at different calcination temperatures (B) with various alcohol volumes (A) under permeation temperature of 40 °C, space velocity of 4.8×104 h-1, and adsorption temperature of 30 °C.

Fig 3B (S2 Table) showed the adsorption capacities of MnFe2O4 nanoparticles prepared at different calcination temperatures for Hg0 under permeation temperature of 40 °C, space velocity of 4.8×104 h-1, and adsorption temperature of 30 °C. As could be seen from the figures, the adsorption capacity increased with the increase of calcination temperature, reached the maximum adsorption capacity of 2.57 μg/g for MnFe2O4 nanoparticles calcinated at 500 °C, and then reduces. From previous experience, it could be seen that the crystallinity of the produced nanoparticle was poor at 400 °C of calcination temperature. And when the calcination temperature was increased to 500 °C, the crystallinity improved greatly and the grain size was relatively small. The growth rate of the grains increased with the increase of the calcination temperature, and the crystallinity and grain size also increased, which in turn led to a decrease of specific surface area and a reduction of adsorption capacity [30]. Therefore, 500 °C was chosen as the optimum calcination temperature. In summary, the MnFe2O4 nanoparticles were prepared with alcohol volume of 30 mL and a calcination temperature of 500 °C for subsequent adsorption experiments.

3.3 Influence of adsorption temperature on the performance of Hg0 removal

As could be seen from Fig 4 (S3 Table), when the permeation temperature and space velocity were controlled at 40 °C and 4.8×104 h-1, respectively, the adsorption capacity of MnFe2O4 nanoparticles for Hg0 increased from 7.68 μg/g to 16.27 μg/g at the adsorption temperature of 30–50 °C. With the further rise of the adsorption temperature, the adsorption capacity of Hg0 began to decline, and the adsorption capacity was only 8.0 μg/g at the adsorption temperature of 120 °C. This could be due to the fact that the adsorption of Hg0 by MnFe2O4 nanoparticles was both physical and chemical adsorption mechanism, and the high temperature would cause the desorption of adsorbed Hg0, and decrease the adsorption capacity, so the high temperature was not conducive to the physical adsorption. Therefore, the temperature of 50 °C was the optimum temperature for adsorption.

Fig 4. Adsorption capacity of MnFe2O4 nanoparticles for Hg0 at different adsorption temperatures under permeation temperature of 40 °C and space velocity of 4.8×104 h-1.

3.4 Effect of space velocity on the performance of mercury adsorption

In this experiment, the space velocity was varied by adjusting the flow rate of the simulated flue gas and other experimental conditions were kept constants. When the permeation temperature and the adsorption temperature were controlled at 40 °C and 50 °C, respectively, four gas flow rates (30 mL/min, 40 mL/min, 50 mL/min, and 60 mL/min) were set, and four space velocities were obtained by calculating 3.6×104 h-1, 4.8×104 h-1, 6.0×104 h-1, and 7.0×104 h-1 via equation. The adsorption capacities of MnFe2O4 nanoparticles for Hg0 at different space velocities were revealed in Fig 5 (S4 Table). It could be seen from the figure that, when the space velocity was increased from 3.6×104 h-1 to 4.8×104 h-1, a large increase of the adsorption capacity for Hg0 onto MnFe2O4 nanoparticles occurred. A reduction of adsorption capacity began to occur when the space velocity was greater than 4.8×104 h-1, which indicated that the space velocity affected the performance of MnFe2O4 nanoparticles for the removal of mercury. The simulated flue gas would have a reduced contact time with the MnFe2O4 nanoparticles due to the rise in space velocity, and the chances of the MnFe2O4 nanoparticles capturing Hg0 would be reduced, thus leading to a decline of adsorption capacity. Therefore, an airspeed lower than 4.8×104 h-1 was chosen to be more favorable for Hg0 capture by MnFe2O4 nanoparticles.

Fig 5. Effect of the space velocity on the performance of MnFe2O4 nanoparticles for Hg0 removal under permeation temperature of 40 °C and the adsorption temperature of 50 °C.

3.5 Variation in adsorption capacity at different mercury permeation temperatures

Fig 6 (S5 Table) presented a trend of the adsorption capacity of MnFe2O4 nanoparticles for Hg0 at different mercury permeation temperatures under space velocity of 4.8×104 h-1 and adsorption temperature of 50 °C. The MnFe2O4 nanoparticles exhibited a relatively larger adsorption capacity in all three permeation temperature ranges. As the permeation temperature rose, a large increase of adsorption capacity was observed. This was probably attributed to the fact that the increase of the concentration gave the adsorbent an increased opportunity to contact with Hg0, which led to an increase of adsorption capacity. And this trend was also important in the practical application of coal-fired power plants, where the amount of adsorbent could be varied according to the actual needs of the plant.

Fig 6. Effect of permeation temperature on Hg0 removal by MnFe2O4 nanoparticles under space velocity of 4.8×104 h-1 and adsorption temperature of 50 °C.

Compared with the previously reported articles related to mercury adsorption in gases (Table 1), the preparation method of MnFe2O4 nanoparticles proposed in this paper was low cost and easy to operate. In addition, the MnFe2O4 nanoparticles had better adsorption performance and short adsorption time, the biggest advantage was that MnFe2O4 could utilize its own magnetism to realize magnetic separation and recycling after adsorption, which effectively avoided secondary pollution.

Table 1. Comparison of mercury adsorption from gases by as-prepared MnFe2O4 nanoparticles with other reported materials.

| Adsorbing material | Initial Hg0 concentration | Adsorption time (min) | Adsorption performance | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Powdered activated carbon | 500 μg/m3 | / | 0.278 mg/g | [34] |

| Sulfurizing activate carbon | / | 120 | 1227.5μg/g | [35] |

| Se/SiO2 adsorbent | 130 μg/m3 | 14,400 | 101.04 mg/g | [36] |

| Fly ash | 12.58 μg/m3 | 180 | 0.005 mg/g | [37] |

| MnFe2O4 | 1.2 mg/m3 | 60 | 16.27 μg/g | This work |

3.6 Characterization of MnFe2O4 nanoparticles before and after adsorption

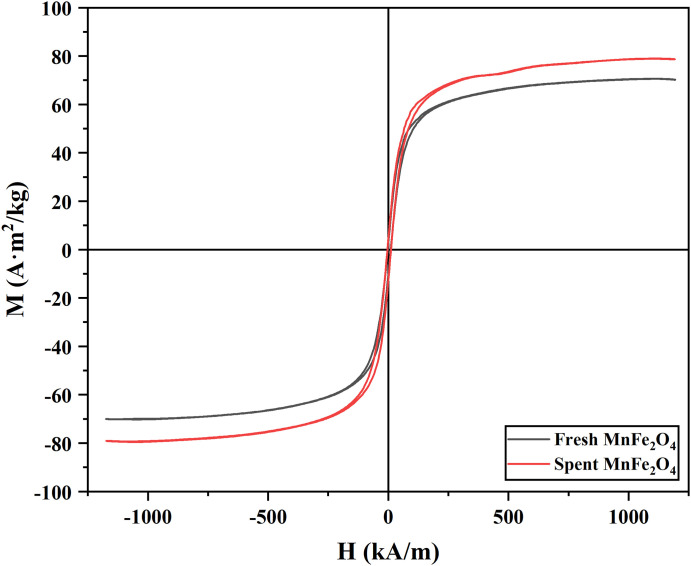

The magnetic properties of the MnFe2O4 nanoparticles before and after adsorption of Hg0 were displayed in Fig 7. Obviously, the saturation magnetization of fresh MnFe2O4 nanoparticles was 79.53 A·m2/kg, after adsorption of Hg0, the saturation magnetization intensity of the MnFe2O4 nanoparticles decreased to 70.21 A·m2/kg. Although the magnetic properties of the MnFe2O4 nanoparticles were slightly reduced, the overall saturation magnetization intensity of the MnFe2O4 nanoparticles was still very superior, and gas-solid separation could be achieved by magnetic separation, which avoided secondary pollution.

Fig 7. Hysteresis loops of MnFe2O4 nanoparticles before and after adsorption.

Fig 8 showed the SEM morphology of the MnFe2O4 nanoparticles after adsorption of Hg0. It could be seen that there was a slight agglomeration of the adsorbed MnFe2O4 nanoparticles with no significant change in the morphology compared with Fig 1A. This demonstrated that the adsorption of Hg0 by MnFe2O4 nanoparticles did not damage the themselves structure of the nanomaterials, which also indicated the possibility of recycling. The EDS plot revealed that the adsorbed materials contained the four elements Mn, Fe, O, and Hg, which demonstrated that Hg0 was successfully adsorbed onto the adsorbent of MnFe2O4 nanoparticles [38].

Fig 8. EDS plot of MnFe2O4 nanoparticles after adsorption.

3.7 TG analyses of MnFe2O4 nanoparticles before and after adsorption

To further investigate the mechanism of Hg0 removal before and after adsorption, TG analyses were performed on fresh and spent MnFe2O4 nanoparticles. As could be seen from Fig 9, the MnFe2O4 nanoparticles have about 1.7% mass loss below 140 °C, which was attributed to the loss of free water. At 140 °C-614 °C, fresh nanoparticles showed a mass loss of 3.7%, which might be caused by the evaporation of bound water in the nanomaterials and the combustion breakdown of part of the carbon skeleton. The mass loss of the spent nanoparticles was more than 1.3% compared with the fresh nanoparticles, which could be due to the desorption of the adsorbed mercury species. When the temperature exceeded 140 °C, the adsorbed Hg0 on the MnFe2O4 nanoparticles was gradually thermally desorbed out, which indicated the presence of physical adsorption in the adsorption process. A significant mass loss was also observed in the range of 400 °C-600 °C, which was due to the decomposition of HgO, demonstrating the chemisorption of Hg0 by the MnFe2O4 nanoparticles [6, 13, 39].

Fig 9. TG curves of the fresh and the spent MnFe2O4 nanoparticles.

4. Conclusion

In this project, magnetic MnFe2O4 nanoparticles were prepared by the rapid combustion method, and the effects of absolute alcohol volume and calcination temperature on magnetic properties and average grain size were investigated during the preparation process. The adsorption effects of different experimental conditions on Hg0 were examined by a fixed-bed experimental system. The experimental results revealed that the average particle size and the saturation magnetization of MnFe2O4 nanoparticles prepared at the calcination temperature of 500 °C with 30 mL of absolute ethanol were 25.3 nm and 79.53 A·m2/kg, and they exhibited the excellent adsorption capacity of 16.27 μg/g for Hg0 at adsorption temperature of 50 °C and a space velocity of 4.8×104 h-1. The comparison of the saturation magnetization intensity before and after adsorption displayed the magnetic stability of the MnFe2O4 nanoparticles after adsorption, which facilitated the separation and reuse in subsequent experiments. EDS and TG plots demonstrated the successful adsorption of Hg0 onto the MnFe2O4 nanoparticles with the formation of the mercury compound as HgO, and the presence of both physical and chemical adsorption.

Supporting information

(TIF)

(BMP)

(TIF)

(TIF)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting information files.

Funding Statement

Vanadium and Titanium Resource Comprehensive Utilization Key Laboratory of Sichuan Province (Grant No. 2020FTSZ14).

References

- 1.Pirarath R, Souwaileh AA, Wu JJ, Anandan S. Amino acid-induced exfoliation of MoS2 nanosheets through hydrothermal method for the removal of mercury. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2024; 561: 121855. doi: 10.1016/j.ica.2023.121855 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meng FY, Yang ZQ, Yang JP, Leng LJ, Qu WQ, Wen PZ, et al. Cupric ion stabilized iron sulfide as an efficient trap with hydrophobicity for elemental mercury sequestration from flue gas. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024; 330: 125385. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2023.125385 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Y, Wang Y, Liu YX, Zhao YC. Clean Modification of Carbon-Based Materials Using Hydroxyl Radicals and Preliminary Study on Gaseous Elemental Mercury Removal. Energy Fuels 2023; 37: 5953–5960. doi: 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.2c04172 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang L, Zheng Y, Li GL, Gao JJ, Li R, Yue T. Review on magnetic adsorbents for removal of elemental mercury from coal combustion flue gas. Environ. Res. 2024; 243: 117734. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2023.117734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu HM, Hong QY, Zhang ZY, Cai XL, Fan YR, Liu ZS, et al. SO2-Driven In Situ Formation of Superstable Hg3Se2Cl2 for Effective Flue Gas Mercury Removal. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023; 57: 5424–5432. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.2c09640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang FJ, Tang TH, Zhang RT, Cheng ZH, Wu J, He P, et al. Magnetically recyclable CoS-modified graphitic carbon nitride-based materials for efficient immobilization of gaseous elemental mercury. Fuel 2022; 326: 125117. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2022.125117 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Su JC, Yang JC, Zhang MK, Gao MK, Zhang YQ, Gao MY, et al. Improvement mechanism of Ru species on Hg0 oxidation reactivity over V2O5/TiO2 Catalyst: A density functional theory study. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2023; 274: 118689. doi: 10.1016/j.ces.2023.118689 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang XP, Wei YY, Zhang LH, Wang XX, Zhang N, Bao JJ, et al. Self-template synthesis of CuCo2O4 nanosheet-based nanotube sorbent for efficient Hg0 removal. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023; 313: 123432. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2023.123432 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ding Z, Yang C, Zhang H, Mei J, Wang J, Yang SJ. New utilizations of natural CuFeS2 as the raw material of Cu smelting for recovering Hg0 from Cu smelting flue gas. Fuel 2023; 341: 126997. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2022.126997 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shen FH, He SD, Li JY, Wang PS, Liu H, Xiang KS. Novel insight into elemental mercury removal by cobalt sulfide anchored porous carbon: Phase-dependent interfacial activity and mechanisms. Fuel 2023; 331: 125740. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2022.125740 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong S, Wang JH, Li CQ, Liu H, Gao ZY, Wu CC, et al. Simultaneous catalytic oxidation mechanism of NO and Hg0 over single-atom iron catalyst. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023; 609: 155298. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2022.155298 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zheng W, Zhou XY, Na YY, Yang JP, Hu YC, Guo QJ, et al. Facile fabrication of regenerable spherical La0.8Ce0.2MnO3 pellet via wet-chemistry molding strategy for elemental mercury removal. Chem. Eng. J. 2024; 479: 147659. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2023.147659 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu Q, Yang XJ, Dong YH, Qian Z, Yuan B, Fu D. Microwave-boosted elemental mercury removal using natural low-grade pyrolusite. Chem. Eng. J. 2023; 455: 140700. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2022.140700 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ye D, Gao SJ, Wang YL, Wang XX, Liu X, Liu H, et al. New insights into the morphological effects of MnOx-CeOx binary mixed oxides on Hg0 capture. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023; 613: 156035. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2022.156035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dou ZF, Wang Y, Liu YX, Zhao YC, Huang RK. Enhanced adsorption of gaseous mercury on activated carbon by a novel clean modification method. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023; 308: 122885. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2022.122885 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.You SW, Liao HY, Tsai CY, Wang C, Deng JG, His HC. Using novel gold nanoparticles deposited activated carbon fiber cloth for continuous gaseous mercury recovery by electrothermal swing system. Chem. Eng. J. 2022; 431: 134325. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2021.134325 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou WJ, Liu M, Zhang SS, Su GD, Jin X, Liu RJ. Hg0 chemisorption of magnetic manganese cobalt nano ferrite from simulated flue gas. Phys. Scripta 2024; 99: 035003. doi: 10.1088/1402-4896/ad2248 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silva BFD, Mafra LC, Zanella DSI, Luiz DG, Rhoden BRC. A DFT theoretical and experimental study about tetracycline adsorption onto magnetic graphene oxide. J. Mol. Liq. 2022; 353: 118837. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2022.118837 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weng XL, Chen W, Cai WL, Owens G, Chen ZL. Synthesis of ferroferric oxide@silicon dioxide/cobalt-based zeolitic imidazole frameworks for the removal of doxorubicin hydrochloride from wastewater. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 2022; 624: 108–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2022.05.150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gürbüz MU, Elmacı G, Ertürk AS. In situ deposition of silver nanoparticles on polydopamine-coated manganese ferrite nanoparticles: Synthesis, characterization, and application to the degradation of organic dye pollutants as an efficient magnetically recyclable nanocatalyst. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2021; 35: e6284. doi: 10.1002/aoc.6284 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ertürk AS, Elmacı G, Gürbüz MU. Reductant free green synthesis of magnetically recyclable MnFe2O4@SiO2-Ag core-shell nanocatalyst for the direct reduction of organic dye pollutants. Turk. J. Chem. 2021; 45: 1968–1979. doi: 10.3906/kim-2108-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gürbüz MU, Koca M, Elmacı G, Ertürk AS. In situ green synthesis of MnFe2O4@EP@Ag nanocomposites using Epilobium parviflorum green tea extract: An efficient magnetically recyclable catalyst for the reduction of hazardous organic dyes. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2021; 35: e6230. doi: 10.1002/aoc.6230 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elmacı G, Özgenç G, Kurz P, Zumreoglu-Karan B. Enhanced water oxidation performances of birnessite and magnetic birnessite nanocomposites by transition metal ion doping. Sustain. Energ. Fuels 2020; 4: 3157–3166. doi: 10.1039/D0SE00301H [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elmacı G, Frey CE, Kurz P, Zümreoğlu-Karan B. Water oxidation catalysis by using nano-manganese ferrite supported 1D-(tunnelled), 2D-(layered) and 3D-(spinel) manganese oxides. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016; 4: 8812–8821. doi: 10.1039/C6TA00593D [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dhal JP, Sahoo A, Acharya AN. Flake shaped ZnFe2O4 nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization and visible light induced photocatalytic study. Emerg. Mater. Res. 2023; 12: 1–9. doi: 10.1680/jemmr.22.00184 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nhlapo TA, Msomi JZ, Moyo T. Temperature-dependent magnetic behavior of Mn-Mg spinel ferrites with substituted Co, Ni & Zn, synthesized by hydrothermal method. J. Mol. Struct. 2021; 1245: 131042. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.131042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yue Y, Zhang XJ, Zhao SH, Wang XY, Wang J, Liu RJ. Construction of Label-Free Electrochemical Biosensing System with Magnetic-Induced Self-Assembly for the Detection of EGFR Glycoprotein. Vacuum 2024; 222: 112975. doi: 10.1016/j.vacuum.2024.112975 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang YL, Wang J, Liu M, Ni Y, Yue Y, He DW, et al. Magnetically induced self-assembly electrochemical biosensor with ultra-low detection limit and extended measuring range for sensitive detection of HER2 protein. Bioelectrochemistry 2024; 155: 108592. doi: 10.1016/j.bioelechem.2023.108592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yue Y, Ouyang HZ, Ma MY, Yang YP, Zhang HD, He AL, et al. Cell-free and label-free nucleic acid aptasensor with magnetically induced self-assembly for the accurate detection of EpCAM glycoprotein. Microchim. Acta 2024; 191: 64. doi: 10.1007/s00604-023-06117-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ni Y, Deng P, Yin RT, Zhu ZY, Ling C, Ma MY, et al. Effect and mechanism of paclitaxel loaded on magnetic Fe3O4@mSiO2-NH2-FA nanocomposites to MCF-7 cells. Drug Deliv. 2023; 30: 64–82. doi: 10.1080/10717544.2022.2154411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deivatamil D, John AMM, Thiruneelakandan R, Joseph PJ. Fabrication of MnFe2O4 and Ni: MnFe2O4 nanoparticles for ammonia gas sensor application. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2021; 123: 108355. doi: 10.1016/j.inoche.2020.108355 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ling C, Wang Z, Ni Y, Zhu ZY, Cheng ZH, Liu RJ. Superior adsorption of methyl blue on magnetic Ni-Mg-Co ferrites: Adsorption electrochemical properties and adsorption characteristics. Environ. Prog. Sustain. 2022; 41: e13923. doi: 10.1002/ep.13923 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pan S, Huang W, Yu QM, Liu X, Liu YH, Liu RJ. A rapid combustion process for the preparation of NixCu(1−x)Fe2O4 nanoparticles and their adsorption characteristics of methyl blue. Appl. Phys. A-Mater. 2019; 125: 88. doi: 10.1007/s00339-019-2390-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin HY, Yuan CS, Chen WC, Hung CH. Determination of the adsorption isotherm of vapor-phase mercury chloride on powdered activated carbon using thermogravimetric analysis. J. Air Waste Manage. 2006; 56: 1550–1557. doi: 10.1080/10473289.2006.10464561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu GF, Xu MR, Liu QC, Yang J, Ma DR, Lu CF, et al. Micromechanism of sulfurizing activated carbon and its ability to adsorb mercury. Appl. Phys. A-Mater. 2013; 113: 389–395. doi: 10.1007/s00339-013-7934-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiao RH, Zhang YL, Wei SZ, Chuai X, Cui X, X Z, et al. A high efficiency and high capacity mercury adsorbent based on elemental selenium loaded SiO2 and its application in coal-fired flue gas. Chem. Eng. J. 2023; 453: 139946. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2022.139946 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu WQ, Wang HR, Zhu TY, Kuang JY, Jing PF. Mercury removal from coal combustion flue gas by modified fly ash. J. Environ. Sci. 2013; 25: 393–398. doi: 10.1016/s1001-0742(12)60065-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ma YP, Xu TF, Zhang XJ, Fei ZH, Zhang HZ, Xu HM, et al. Manganese bridge of mercury and oxygen for elemental mercury capture from industrial flue gas in layered Mn/MCM-22 zeolite. Fuel 2021; 283: 118973. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2020.118973 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luo ZF, You L, Wu J, Song YB, Ren SY, Jia T, et al. Selenium ligands doped ZnS for highly efficient immobilization of elemental mercury from coal combustion flue gas. Chem. Eng. J. 2021; 420: 129843. doi: 10.1016/10.1016/j.cej.2021.129843 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(TIF)

(BMP)

(TIF)

(TIF)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting information files.