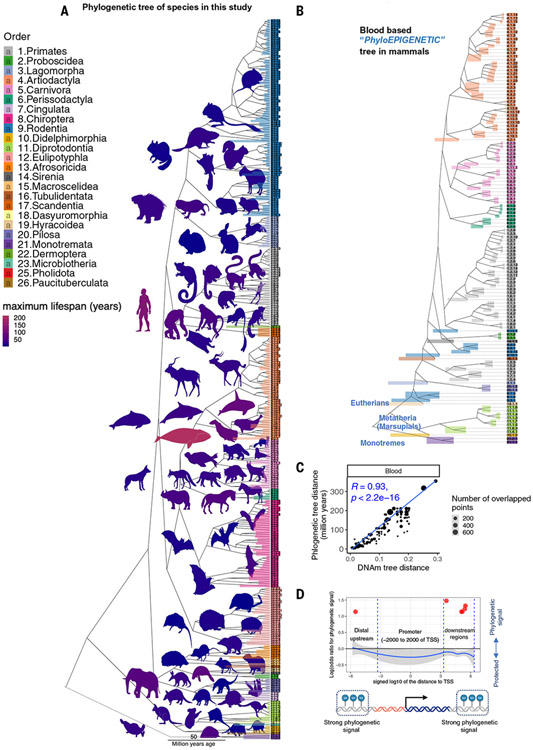

Fig. 1. Phyloepigenetic trees parallel the mammalian evolutionary tree.

(A) The traditional phylogenetic tree from the TimeTree database (44) based on 321 (of 348) species in our study. A full description of the species in our study is reported in table S1. (B) Blood-based phyloepigenetic tree created from hierarchical clustering of DNAm data in this study (for additional analysis, see fig. S3, A and B). We formed the mean value per cytosine across samples for each species. The clustering used 1 minus the Pearson correlation (1-cor) as a pairwise dissimilarity measure and the average linkage method as intergroup dissimilarity. Phyloepigenetic trees for skin and liver can be found in fig. S2. Additional analyses, e.g., involving different choices of CpGs or intergroup dissimilarity measures, are reported in the supplementary materials (fig. S2). The colored bars reflect the branch height. (C) Scatter plot of the distances in blood phyloepigenetic (1-cor) versus the traditional evolutionary tree. (D) Scatter plots displaying the log-odds ratios of regions exhibiting phylogenetic signals relative to the TSS are presented. The phylogenetic signal is determined using Blomberg’s K statistic (32). In this analysis, CpGs were grouped into categories using sliding windows relative to the TSS. To assess enrichment, the Fisher’s exact overlap test was used, focusing on the top 500 CpGs displaying phylogenetic signals within each region. The red dots highlight the regions with the Fisher’s exact P value < 0.05. The results indicate notable enrichment (OR > 3) in certain intergenic and genic regions but not in promoters. For additional analysis, see fig. S4.