Abstract

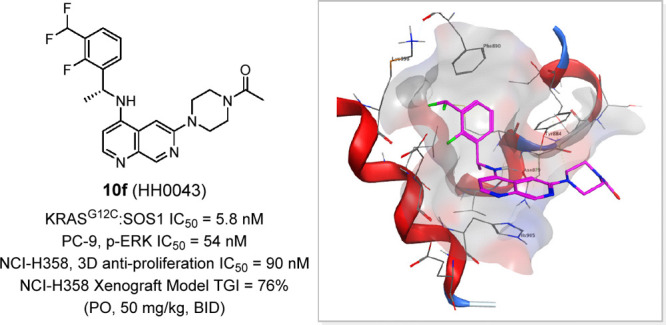

SOS1, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF), plays a critical role in catalyzing the conversion of KRAS from its GDP- to GTP-bound form, regardless of KRAS mutation status, and represents a promising new drug target to treat all KRAS-driven tumors. Herein, we employed a scaffold hopping strategy to design, synthesize, and optimize a series of novel binary ring derivatives as SOS1 inhibitors. Among them, compound 10f (HH0043) displayed potent activities in both biochemical and cellular assays and favorable pharmacokinetic profiles. Oral administration of HH0043 resulted in a significant tumor inhibitory effect in a subcutaneous KRASG12C-mutated NCI-H358 (human lung cancer cell line) xenograft mouse model, and the tumor inhibitory effect of HH0043 was superior to that of BI-3406 at the same dose (total growth inhibition, TGI: 76% vs 49%). On the basis of these results, HH0043, with a novel 1,7-naphthyridine scaffold that is distinct from currently reported SOS1 inhibitors, is nominated as the lead compound for this discovery project.

Keywords: RAS Mutation, KRAS-SOS1 Interaction, SOS1 Inhibitor, Antitumor Efficacy

RAS proteins (KRAS4A, KRAS4B, NRAS, and HRAS) comprise a highly conserved family of small GTPases and transduce upstream growth factor receptors signals to downstream effector pathways, including mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), and RAL guanine nucleotide dissociation stimulator (RAL-GDS).1 RAS proteins are binary on–off molecular switches that cycle between an active GTP-bound state and an inactive GDP-bound state.2 These switches of wild-type RAS are tightly controlled, while the intrinsic GTPase activity of mutated RAS is impaired, which results in constitutively activated state.3 About 25% of human cancers harbor mutations of RAS genes with 98% of the point mutations at amino acids G12, G13, and Q61.4KRAS mutations are the most common oncogene alteration and occur most frequently in solid malignancies, including pancreatic, colorectal and lung cancers.5 Numerous efforts have been conducted to target either KRAS GTP-bound state or KRAS GDP-bound state in the last four decades,6 but only two drugs, sotorasib and adagrasib, which specifically targeted KRASG12C, have been approved by the FDA.7 Unfortunately, intrinsic or acquired resistance to sotorasib or adagrasib in patients has been emerging in clinic,8,9 thereby suggesting the imperative to explore more novel therapeutic strategies for targeting KRAS mutant cancers.

Son of Sevenless (SOS) proteins involving two human isoforms, SOS1 and SOS2, are the most studied guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs), which catalyze the exchange of GDP for GTP on RAS.10 Most studies support that SOS1 plays a dominant functional role in various physiological and pathological contexts over SOS2 to activate KRAS through protein–protein interactions (PPIs).11,12 Small molecule inhibitors binding with the SOS1 protein to disrupt KRAS-SOS1 PPIs would be highly desirable for treating cancers harboring KRAS mutation, in addition to direct KRAS-targeting therapies. Furthermore, combination of SOS1 inhibitor and covalent KRASG12C inhibitor could be an effective strategy to enhance the efficacy and delay intrinsic or acquired resistance compared with KRASG12C inhibitor alone.13−15

Many efforts aimed at discovering SOS1 inhibitors have recently been implemented (Figure 1). Hillig et al. first reported a series of quinazoline derivatives as SOS1 binders to disrupt the KRAS-SOS1 interaction. This project led to the discovery of BAY-293 (1), which displayed a moderate biochemical activity (IC50 = 21 nM) and a synergistic antiproliferative activity in combination with KRASG12C inhibitor.16 Subsequently another quinazoline compound BI-3406 (2) with an improved activity compared with BAY-293 was disclosed by scientists from Boehringer Ingelheim through a high-throughput screening (HTS) campaign and structure-based drug design and optimization efforts.17 The discovery of compounds 1 and 2 demonstrates the feasibility of SOS1 binder to interrupt KRAS-SOS1 PPIs and initiate a new paradigm to design novel SOS1 inhibitors,18,19 which is illustrated by RMC-0331 (3),20 MRTX-0902 (4),215,22 and 6.23 Differentiating from the classical quinazoline scaffold, MRTX-0902 (4) with a phthalazine core was reported by Mirati Therapeutics and now is in Phase I/II study with indications for solid tumors (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05578092). Although plentiful SOS1 inhibitors have been disclosed,24 few of them have entered into clinical trail, except BI 1701963 (structure was not disclosed) and MRTX-0902. Therefore, diversified and highly potent SOS1 inhibitors with good druglike properties are still needed as a monotherapy or in combination with other drugs targeting the KRAS/MAPK pathway. Herein, we report the discovery of novel naphthyridine derivatives as potent SOS1 inhibitors and the identification of the orally bioavailable 10f as a promising lead compound for the treatment of KRAS-mutated cancers (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Reported SOS1 inhibitor.

Figure 2.

Systematic modification and lead identification

The available cocrystal structure of BI-3406 bound with SOS1 (PDB: 6SCM) revealed that the quinazoline core forms a π–π stacking interaction with His905, which contributes significantly to the binding affinity,17 thereby suggesting that this quinazoline core could possibly be substituted by other bicyclic rings to afford a novel scaffold with differentiated activity and drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics (DMPK) profile (this hypothesis was also confirmed by compound MRTX-090221). Hillig et al. had explored limited biaryl rings from their initial hit compound 7a.16 The SOS1 inhibitory activity of quinoline 7b was slightly reduced compared with 7a (IC50: 2590 vs 320 nM), whereas switching to the isoquinoline analogue 7c was detrimental (IC50: 12 200 nM). The differences in the activity of compounds 7a, 7b, and 7c correlated well with cocrystal structures (PDB: 5OVE) in which the N1 position of 7a facing the solvent region favored a polar atom. We chose the quinoline core as our starting point, and to our delight, simply replaced (R)-1-(naphthalen-1-yl)ethan-1-amine with privileged (R)-1-[3-(difluoromethyl)-2-fluorophenyl]ethan-1-amine25 to afford compound 8 with comparable potency as BI-3406 in biochemical assay (Table 1). Inspired by this finding, we initiated our SAR exploration at the R1 group of 9, which extended from the SOS1 binding pocket to the interaction surface of SOS1 and KRAS.

Table 1. Structures and In Vitro Activities of Quinoline Derivativesa.

The potency of the designed compounds was measured using a homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence (HTRF) biochemical assay and a p-ERK cellular assay in PC-9 cells.

As shown in Table 1, 9a containing a (S)-tetrahydrofuran-3-olyl group, a preferred moiety used in BI-3406, gave a single-digit nanomolar biochemical activity against SOS1 (IC50 = 6.7 nM). Compared with 9a, 9b with a basic (S)-pyrrolidin-3-olyl substitution maintained a similar biochemical activity but was 2-fold weaker in p-ERK inhibition (IC50: 212 vs 497 nM). Introduction of a larger piperidine ring (9c) caused a loss of activity in both biochemical and cellular assays. Furthermore, N-methylation of the pyrrolidine of 9b led to 9d with decreased biochemical activity (IC50 = 15 nM) but slightly better p-ERK inhibition potency (IC50 = 295 nM). While acetylation of the pyrrolidine afforded a potent SOS1 inhibitor 9e with 5-fold improved cellular activity compared with 9b (45 vs 212 nM), no further benefit in p-ERK inhibition capability was observed in both 9f and 9g with a bulkier amide group. Cyclic substituents at R1 (9h to 9l) were all well tolerated for biochemical potency but had variable p-ERK inhibition activities, as N-linked 9k and 9l performed significantly better than the C-linked analogue (34-fold p-ERK inhibition IC50 improvement from 9j to 9k) in cellular assay, which indicated the necessity to have the R1 ring coplanar with the quinoline ring for optimal p-ERK inhibition in cells.

On the basis of the in vitro potency, 9e and 9l were selected for further in vivo pharmacokinetic evaluations. Compounds 9e and 9l were tested in male CD-1 mice at a single oral dose of 5 mg/kg and single intravenous injection dose of 1 mg/kg. As shown in Table 3, both 9e and 9l exhibited very high clearance (107 and 127 mL/min/kg, respectively) and low oral bioavailability (19% and 5%). We speculated the basic amino quinoline scaffold caused the suboptimal DMPK profile because of its low permeability and inferior metabolic stability. Moreover, preliminary safety profiling of this series showed a trend of strong affinity to the human ether-a-go-go-related gene (hERG) ion channel (data not shown). Considering these liabilities, this quinoline series was deprioritized.

Table 3. In Vivo Pharmacokinetic Properties of Selected Compounds in Male CD-1 Micea.

| po |

iv |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound | Cmax (ng/mL) | AUC (ng h/mL) | F (%) | CL (mL/min/kg) | t1/2 (h) |

| 9e | 77 | 152 | 19 | 107 | 0.45 |

| 9l | 10 | 29 | 5 | 127 | 1.75 |

| 10c | 424 | 578 | 25 | 40 | 0.88 |

| 10e | 136 | 406 | 36 | 67 | 1.18 |

| 10f | 714 | 1953 | 81 | 35 | 1.53 |

All compounds were po dosed at 5 mg/kg and iv dosed at 1 mg/kg in a solution of 5% DMSO + 95% (20% HP-β-CD). Cmax, highest observed plasma concentration; AUC, area under the concentration–time curve. F, bioavailability. CL, elimination rate. t1/2, elimination half-life.

To address metabolic instability and hERG issues, we attempted to lower lipophilicity and basicity of the quinoline core by introducing heteroatoms into the biaryl ring.26 In comparison with quinoline, the 1,7-naphthyridine scaffold met the requirement (−0.6 in cLogP and −1.1 log in pKa) and was selected for the next round of SAR exploration at the C6 position (Table 2). Compound 10a, as a matched pair of 9a, showed 2-fold decreased activity against SOS1, but C-linked cyclic substituents in naphthyridine were much better tolerated compared with those in quinoline scaffold, which is readily explained by better alignment of the R1 group with the naphthyridine ring because of this 7-N atom. Additionally, the N-linked cyclic substituents with various polar functional groups at the 4-position all displayed excellent potency in KRAS/SOS1 binding inhibition and p-ERK inhibition assays except 10i with a slightly larger acetamide group. Compounds 10c, 10e, and 10f, which had the most promising p-ERK inhibition IC50 values in PC-9 cells, were advanced into further characterizations.

Table 2. Structures and In Vitro Activities of 1,7-Naphthyridine Derivatives.

NT: not tested.

With the expectation to mitigate undesired in vivo clearance issues in quinoline series, pharmacokinetic profiles of compounds 10c, 10e, and 10f were first assessed in CD-1 mice (Table 3). Gratifyingly all three compounds achieved much lower CL than 9c/9l, and 10f demonstrated the most balanced pharmacokinetics (PK) profile with moderate systemic clearance (CL = 35 mL/min/kg), high oral exposure (AUC = 1953 ng h/mL), and high bioavailability (F = 81%). Further in vitro characterizations of 10f (Table 4) showed it has moderate unbound free fraction (5% to ∼7%) in plasmas across species (mouse, rat, dog, and human) and exhibits weak inhibition against CYP 1A2, 2D6, and 3A4-M but a moderate inhibition against 2C9 and 2C19 (IC50 = 5.69, 3.16 μM).27 Compound 10f still had certain hERG inhibition liability (IC50 = 2.45 μM) but was qualified as a lead compound to advance into in vivo evaluation.

Table 4. In Vitro Pharmacokinetics Profiles of 10f.

| PPB

(fu, %) |

CYP

IC50 (μM) |

hERG IC50 (μM) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mouse | rat | dog | human | 1A2 | 2C9 | 2C19 | 2D6 | 3A4-M | ||

| 10f | 6.75 | 5.29 | 5.45 | 4.81 | 17.50 | 5.69 | 3.16 | 11.10 | >50 | 2.45 |

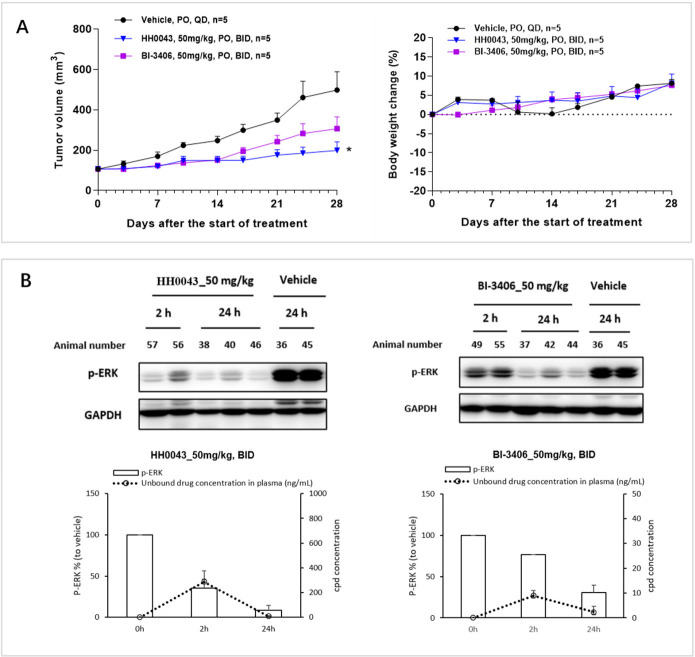

When evaluated in NCI-H358 (human nonsmall lung cancer cell line) cells harboring KRASG12C mutation, compound 10f (HH0043) was demonstrated to be 3–4 times more potent than BI-3406 using 3D proliferative assay (IC50: 90 vs 322 nM). In light of the excellent biochemical and cellular KRASG12C/SOS1 inhibitory activities, favorable DMPK profile, and the in vivo efficacy of HH0043, it was further investigated in a NCI-H358 tumor xenograft mouse model. After a single dose of 50 mg/kg in mouse, an unbound concentration of HH0043 in plasma could be maintained above its antiproliferation IC50 (NCI-H358, 3D assay) for 8 h (see Figure S1). Therefore, 50 mg/kg twice a day via oral gavage was selected to maximize the potential efficacy for this study. After 28 days of treatment, HH0043 showed superior antitumor efficacy (total growth inhibition, TGI = 76%) compared with BI-3406 (TGI = 49%), and no obvious body weight loss was observed (Figure 3A). Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics (PK/PD) study on the 28th day of treatment demonstrated that HH0043 could inhibit p-ERK level in vivo more effectively than BI-3406 at the same dose (Figure 3B). Additionally, HH0043 exhibited a durable p-ERK inhibition in reference to the p-ERK modulation in tumors at 2 and 24 h, and this may be attributed to SOS1 inhibition, which could delay the ERK-dependent negative feedback and, therefore, maintain longer p-ERK inhibition.15

Figure 3.

In vivo antitumor activity and PK/PD relationship of HH0043 in NCI-H358 human nonsmall lung cancer xenograft model harboring KRASG12C mutation. (A) In vivo antitumor efficacy (left panel) and effects on animal body weight (right panel). (B) p-ERK modulation in the NCI-H358 xenograft model on the 28th day of treatment. p-ERK levels of tumor samples were detected at 2 and 24 h after drug treatment, and drug concentrations in plasma were measured at the corresponding time points. Data in (A) and (B, lower panel) represent mean ± SEM; *, P < 0.05 compared with vehicle group on day 28.

The synthetic route to prepare HH0043 as a representative compound is outlined in Scheme 1. Carboxylic acid (11) was converted to a Weinreb amide 12 and then treated with methyl magnesium bromide at 0 °C to afford ketone 13. Cyclization with DMF-DMA (N,N-dimethylformamide dimethyl acetal) followed by cesium carbonate yielded hydroxy naphthyridine 14, which was brominated with POBr3 to provide 15 as a key intermediate. A Buchwald coupling reaction of 15 and the known chiral benzylic amine was conducted to give 16. Displacement of 6-chlorine atom in 16 with piperazine resulted in the production of 17 followed by acetylation with acetic anhydride finally delivered the desired compound HH0043.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Representative Compound HH0043.

Reagents and conditions: (a) N,O-dimethylhydroxylamine hydrochloride, ethyl-3-[3-(dimethylamino)propyl]carbodiimide (EDCI), hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt), diisopropylethylamine (DIEA), DMF, rt, overnight; 51% yield. (b) Methylmagnesium bromide, THF, 0 °C, 2 h; 73% yield. (c) Step 1: DMF-DMA, 1,4-dioxane, 80 °C, overnight. Step 2: Cs2CO3, DMF, 100 °C, 4 h; crude. (d) POBr3, DMF, rt, 4 h; 64% total yield for (c) and (d). (e) (R)-1-(3-(difluoromethyl)-2-fluorophenyl)ethan-1-amine hydrochloride, Pd(OAc)2, racemic-2,2′-bis(diphenylphosphino)-1,1′-binaphthyl (BINAP), t-BuONa, toluene, 100 °C, overnight; 47% yield. (f) Piperazine, DMF, 150 °C, overnight; 43% yield. (g) Acetic anhydride, TEA, DCM, 0 °C to ∼rt, 2 h; 16% yield.

In summary, we designed and synthesized a novel quinoline and naphthyridine series of SOS1 inhibitors by using a scaffold hopping strategy. Preliminary SAR exploration and DMPK evaluation led to the discovery of HH0043, which displayed favorable in vitro biochemical and cellular activity, satisfying pharmacokinetic profiles, and potent antitumor efficacy in NCI-H358 xenograft model. On the basis of these results, HH0043 with a novel 1,7-naphthyridine scaffold, which is distinct from currently reported SOS1 inhibitors, is nominated as the lead compound for this discovery project. However, the unbound Cmax of HH0043 at efficacious dose (50 mg/kg) is calculated to be 1.66 μM, which suggests a limited cardiac safety window when taking its hERG IC50 = 2.45 μM into consideration. Efforts to mitigate the drug–drug interaction and cardiovascular liability of HH0043 are in progress,28 and the preclinical candidate compound will be communicated in due time.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- PDB

Protein Data Bank

- SAR

structure–activity relationship

- hERG

human ether-a-go-go-related gene

- fu

fraction unbound

- EDCI

ethyl-3-[3-(dimethylamino)propyl]carbodiimide

- HOBt

hydroxybenzotriazole

- DIEA

diisopropylethylamine

- DMF

N,N-dimethylformamide

- DMF-DMA

N,N-dimethylformamide dimethyl acetal

- THF

tetrahydrofuran

- TEA

triethylamine

- DCM

dichloromethane

- BINAP

racemic-2,2′-Bis(diphenylphosphino)-1,1′-binaphthyl.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.4c00156.

Experimental details and compound characterization data for synthetic compounds, biochemical assays, and ADME assays (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Hymowitz S. G.; Malek S. Targeting the MAPK Pathway in RAS Mutant Cancers. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Med. 2018, 8, a031492. 10.1101/cshperspect.a031492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chardin P.; Camonis J. H.; Gale N. W.; van Aelst L.; Schlessinger J.; Wigler M. H.; Bar-Sagi D. Human Sos1: A Guanine Nucleotide Exchange Factor for Ras That Binds to GRB2. Science 1993, 260, 1338–1342. 10.1126/science.8493579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haigis K. M. KRAS Alleles: The Devil Is in the Detail. Trends Cancer 2017, 3, 686–697. 10.1016/j.trecan.2017.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs G. A.; Der C. J.; Rossman K. L. RAS Isoforms and Mutations in Cancer at a Glance. J. Cell Sci. 2016, 129, 1287–1292. 10.1242/jcs.182873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrem J. M.; Shokat K. M. Direct Small-molecule Inhibitors of KRAS: from Structural Insights to Mechanism-based Design. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2016, 15, 771–785. 10.1038/nrd.2016.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore A. R.; Rosenberg S. C.; McCormick F.; Malek S. RAS-targeted Therapies: Is the Undruggable Drugged?. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2020, 19, 533–552. 10.1038/s41573-020-0068-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosell R.; Aguilar A.; Pedraz C.; Chaib m. KRAS Inhibitors, Approved. Nat. Cancer 2021, 2, 1254–1256. 10.1038/s43018-021-00289-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awad M. M.; Liu S.; Rybkin I. I.; Arbour K. C.; Dilly J.; Zhu V. W.; Johnson M. L.; Heist R. S.; Patil T.; Riely G. J.; Jacobson J. O.; Yang X.; Persky N. S.; Root D. E.; Lowder K. E.; Feng H.; Zhang S. S.; Haigis K. M.; Hung Y. P.; Sholl L. M.; Wolpin B. M.; Wiese J.; Christiansen J.; Lee J.; Schrock A. B.; Lim L. P.; Garg K.; Li M.; Engstrom L. D.; Waters L.; Lawson J. D.; Olson P.; Lito P.; Ou S.-H. I.; Christensen J. G.; Jänne P. A.; Aguirre A. J. Acquired Resistance to KRASG12C Inhibition in Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 2382–2393. 10.1056/NEJMoa2105281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Kang R.; Tang D. The KRAS-G12C Inhibitor: Activity and Resistance. Cancer Gene Ther. 2022, 29, 875–887. 10.1038/s41417-021-00383-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigil D.; Cherfils J.; Rossman K. L.; Der C. J. Ras Superfamily GEFs and GAPs: Validated and Tractable Targets for Cancer Therapy?. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2010, 10, 842–857. 10.1038/nrc2960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltanas F. C.; Zarich N.; Rojas-Cabaneros J. M.; Santos E. SOS GEFs in Health and Disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Rev. Cancer 2020, 1874, 188445. 10.1016/j.bbcan.2020.188445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman T. S.; Sondermann H.; Friedland G. D.; Kortemme T.; Bar-Sagi D.; Marqusee S.; Kuriyan J. A Ras-induced Conformational Switch in the Rasactivator Son of Sevenless. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006, 103, 16692–16697. 10.1073/pnas.0608127103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga T.; Suda K.; Fujino T.; Ohara S.; Hamada A.; Nishino M.; Chiba M.; Shimoji M.; Takemoto T.; Arita T.; Gmachl M.; Hofmann M. H.; Soh J.; Mitsudomi T. KRAS Secondary Mutations That Confer Acquired Resistance to KRAS G12C Inhibitors, Sotorasib and Adagrasib, and Overcoming Strategies: Insights From In Vitro Experiments. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2021, 16, 1321–1332. 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Kang R.; Tang D. The KRAS-G12C Inhibitor: Activity and Resistance. Cancer Gene Ther. 2022, 29, 875–878. 10.1038/s41417-021-00383-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singhal A.; Li B. T.; O’Reilly E. M. Targeting KRAS in cancer. Nat. . Med. 2024, 30, 969–983. 10.1038/s41591-024-02903-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillig R. C.; Sautier B.; Schroeder J.; Moosmayer D.; Hilpmann A.; Stegmann C. M.; Werbeck N. D.; Briem H.; Boemer U.; Weiske J.; Badock V.; Mastouri J.; Petersen K.; Siemeister G.; Kahmann J. D.; Wegener D.; Bohnke N.; Eis K.; Graham K.; Wortmann L.; von Nussbaum F.; Bader B. Discovery of Potent SOS1 Inhibitors that Block RAS Activation via Disruption of the RAS-SOS1 Interaction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2019, 116, 2551–2560. 10.1073/pnas.1812963116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann M. H.; Gmachl M.; Ramharter J.; Savarese F.; Gerlach D.; Marszalek J. R.; Sanderson M. P.; Kessler D.; Trapani F.; Arnhof H.; Rumpel K.; Botesteanu D.-A.; Ettmayer P.; Gerstberger T.; Kofink C.; Wunberg T.; Zoephel A.; Fu S.-C.; Teh J. L.; Böttcher J.; Pototschnig N.; Schachinger F.; Schipany K.; Lieb S.; Vellano C. P.; O’Connell J. C.; Mendes R. L.; Moll J.; Petronczki M.; Heffernan T. P.; Pearson M.; McConnell D. B.; Kraut N. BI-3406, a Potent and Selective SOS1–KRAS Interaction Inhibitor, Is Effective in KRAS-Driven Cancers Through Combined MEK Inhibition. Cancer Discovery 2021, 11, 142–157. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramharter J.; Kessler D.; Ettmayer P.; Hofmann M. H.; Gerstberger T.; Gmachl M.; Wunberg T.; Kofink C.; Sanderson M.; Arnhof H.; Bader G.; Rumpel K.; Zophel A.; Schnitzer R.; Bottcher J.; O’Connell J. C.; Mendes R. L.; Richard D.; Pototschnig N.; Weiner I.; Hela W.; Hauer K.; Haering D.; Lamarre L.; Wolkerstorfer B.; Salamon C.; Werni P.; Munico-Martinez S.; Meyer R.; Kennedy M. D.; Kraut N.; McConnell D. B. One Atom Makes All the Difference: Getting a Foot in the Door between SOS1 and KRAS. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 6569–6580. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T.; Tang X.; Wang Z.; Feng F.; Xu C.; Zhao Q.; Wu Y.; Sun H.; Chen Y. Inhibition of Son of Sevenless Homologue 1 (SOS1): Promising therapeutic treatment for KRAS-mutant cancers. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 261, 115828. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2023.115828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckl A.; Quintana E.; Lee G. J.; Shifrin N.; Zhong M.; Garrenton L. S.; Montgomery D. C.; Stahlhut C.; Zhao F.; Whalen D. M.; Thompson S. K.; Tambo-ong A.; Gliedt M.; Knox J. E.; Cregg J. J.; Aay N.; Choi J.; Nguyen B.; Tripathi A.; Zhao R.; Saldajeno-Concar M.; Marquez A.; Hsieh D.; McDowell L. L.; Koltun E. S.; Bermingham A.; Wildes D.; Singh M.; Wang Z.; Hansen R.; Smith J. A.; Gill A. L. Discovery of a Potent, Selective, and Orally Bioavailable SOS1 Inhibitor, RMC-023, an in vivo Tool Compound that Blocks RAS Activation via Disruption of the RAS-SOS1 Interaction. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 1273. 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2021-1273. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ketcham J. M.; Haling J.; Khare S.; Bowcut V.; Briere D. M.; Burns A. C.; Gunn R. J.; Ivetac A.; Kuehler J.; Kulyk S.; Laguer J.; Lawson J. D.; Moya K.; Nguyen N.; Rahbaek L.; Saechao B.; Smith C. R.; Sudhakar N.; Thomas N. C.; Vegar L.; Vanderpool D.; Wang X.; Yan L.; Olson P.; Christensen J. G.; Marx M. A. Design and Discovery of MRTX0902, a Potent, Selective, Brain-Penetrant, and Orally Bioavailable Inhibitor of the SOS1:KRAS Protein-Protein Interaction. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 9678–9690. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c00741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He H.; Zhang Y.; Xu J.; Li Y.; Fang H.; Liu Y.; Zhang S. Discovery of Orally Bioavailable SOS1 Inhibitors for Suppressing KRAS-Driven Carcinoma. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 13158–13171. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c00986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M.; Zhou G.; Su W.; Gu Y.; Gao M.; Wang K.; Huo R.; Li Y.; Zhou Z.; Chen K.; Zheng M.; Zhang S.; Xu T. Design, Synthesis, and Bioevaluation of Pyrido[2,3-d]pyrimidin-7-ones as Potent SOS1 Inhibitors. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2023, 14, 183–190. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.2c00490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson S. K.; Buckl A.; Dossetter A. G.; Griffen E.; Gill A. Small molecule Son of Sevenless 1 (SOS1) inhibitors: a review of the patent literature. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2021, 31, 1189–1204. 10.1080/13543776.2021.1952984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramharter J.; Kofink C.; Stadtmueller H.; Wunberg T.; Hofmann M. H.; Baum A.; Gmachl M.; Rudolph D. I.; Savarese F.; Ostermeier M.; Frank M.; Gille A.; Goepper S.; Santagostino M.; Wippich J.. Novel Benzyl Amino Substituted Pyridopyrimidinones and Derivatives as SOS1 Inhibitors. WO 2019/122129 A1, 2019.

- Jamieson C.; Moir E. M.; Rankovic Z.; Wishart G. Medicinal Chemistry of hERG Optimizations: Highlights and Hang-Ups. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 5029–5045. 10.1021/jm060379l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Z.; Caldwell G. W. Metabolism Profiling, and Cytochrome P450 Inhibition & Induction in Drug Discovery. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2001, 1, 403–425. 10.2174/1568026013395001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Q.; Li D.; Jiang S.; Zhu J.; Yu S.; Yang M.; Cai Y.; Liu L.; Yu B.; Tu W.; Zhang Y.; Li L. Discovery and Characterization of HH100937, a potent and selective SOS1 inhibitor demonstrates synergistic efficacy in combination with KRAS/MAPK therapies. Cancer Res. 2024, 84, LB031. 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2024-LB031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.