Abstract

Bfl-1 is overexpressed in both hematological and solid tumors; therefore, inhibitors of Bfl-1 are highly desirable. A DNA-encoded chemical library (DEL) screen against Bfl-1 identified the first known reversible covalent small-molecule ligand for Bfl-1. The binding was validated through biophysical and biochemical techniques, which confirmed the reversible covalent mechanism of action and pointed to binding through Cys55. This represented the first identification of a cyano-acrylamide reversible covalent compound from a DEL screen and highlights further opportunities for covalent drug discovery through DEL screening. A 10-fold improvement in potency was achieved through a systematic SAR exploration of the hit. The more potent analogue compound 13 was successfully cocrystallized in Bfl-1, revealing the binding mode and providing further evidence of a covalent interaction with Cys55.

Keywords: DEL, Bfl-1, cysteine, reversible covalent, cyano-acrylamide, phosphine oxide

Bcl2-related protein A1 (Bfl-1)is a member of the Bcl2 family of anti-apoptotic proteins.1 Like all members of the family it prevents apoptosis by sequestering pro-death Bcl homology 3 (BH3)-only proteins, specifically Bim, Bid, Puma and Noxa, with nanomolar affinity.2−4 Bfl-1 is overexpressed across subsets of hematological and solid tumors and minimally expressed in non-hematopoietic primary tissues.5−8 Furthermore, Bfl-1 overexpression has been shown to confer resistance to venetoclax in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patient samples.9−11 Overexpression of Bfl-1 is thought to disrupt the natural balance between pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins, leading to cell survival and ultimately oncogenesis. In cells where Bfl-1 is overexpressed, inhibition of Bfl-1 should cause increased levels of pro-apoptotic proteins Bim, Bid, Puma and Noxa, ultimately leading to apoptosis. Therefore, inhibitors of Bfl-1 would be highly desirable, first as tools to validate this mechanism, and subsequently as potential therapeutics.12

Bfl-1 is a 175 amino acid protein localized in the cytosol and mitochondria.13 The BH3 binding site is formed by a bundle of α-helix folds and, uniquely among the Bcl2 family, has a cysteine present in this protein–protein interface (PPI).13 This cysteine was first shown to be targetable through the installation of covalent reactive groups on modified pro-apoptotic peptides.14,15 More recently Harvey et al. have shown the potential of targeting Cys55 with covalent compounds, employing the disulfide tethering technique to find compounds that could displace Bim from Bfl-1.16 Acrylamide binders to Cys55 have subsequently been discovered.17 There are also a number of reversible binders to Bfl-1 that have been reported in the literature,18−20 and so, despite knowing about the potential for covalent inhibition, our hit-finding approach was not solely directed toward targeting the Cys55 residue.

DNA-encoded chemical libraries (DELs) are collections of billions of molecules, each individually labeled with a unique combination of DNA identifier tags.21,22 DELs can be screened in a single tube against a target of interest by using affinity-mediated selection to identify novel ligands. Amplification of the concatenated DNA tags of compounds that are enriched during the selection conditions allows for the identification of a set of compounds to make “off-DNA” and test in a downstream cascade to confirm binders. DEL screens have previously delivered hits for PPIs, notably through the use of macrocyclic library design.23 DELs typically consist of reversible compounds, but there is precedent for the identification of reversible covalent inhibitors. For example, Steffek et al. recently reported a series of aldehydes as binders to LC3A.24 However, routine incorporation of reversible covalent chemistries, such as the well-explored cyano-acrylamide group,25−29 into DELs is not generally common practice. A DEL screen was considered as part of our multi-faceted hit-identification campaign against Bfl-1 for two principal reasons: first, as the BH3 binding site is a PPI, it was felt that a numerically large DEL collection would have a good chance of finding suitable hits; second, as we had recently incorporated a library of cyano-acrylamides in our DEL collection, there was an opportunity to identify both reversible non-covalent and reversible covalent ligands. An important note here is that irreversible covalent DEL screens have been reported but require a modified workflow and bespoke DELs, and consequently were not prioritized at this time.30−32 Another important consideration was that related family members Bcl-xl and Mcl-1 could be used as a counter screen to ensure hits were selective for Bfl-1. Herein we describe the results of the DEL screen. Other arms of our hit-finding campaign will be reported in due course.

DEL Screen

Prior to screening, Bfl-1 was determined to be monomeric by size exclusion chromatography with multi-angle static light scattering (SEC-MALS). Efficient capture was confirmed by immobilized streptavidin (Bfl-1 and Mcl-1) and immobilized Ni2+ (Bfl-1 and Bcl-xl) matrices. All three immobilized targets were shown to bind to a labeled BIM peptide. Affinity-mediated selection was initiated by incubating a deck of 87 DELs, containing billions of molecules, under a range of conditions (Figure S1) including with 8 μM of each protein, with and without 80 μM BIM peptide, with Bfl-1 additionally at 1 μM, using each of the capture methods listed above, and the corresponding no-target (matrix-only) control (NTC) in a model cytosolic buffer. The output of the first round of selection was used as the input for the second round with fresh protein and competitor reagents, and the output of the second round of selection was PCR-amplified and sequenced. Library compounds previously determined to be active against Mcl-1 or Bcl-xl were seen to re-enrich against the same targets, confirming the integrity of the screen.33 After analysis of the selection output data, 65 compounds were ultimately selected for off-DNA synthesis based on having the desired profile (i.e., enrichment vs Bfl-1 and not for the NTC or other Bcl-2 family members, and competitive with the BIM peptide, Figure S2). These represented 52 families from 18 different libraries. The compounds were then tested in a Bfl-1 BIM probe displacement TR-FRET assay to determine binding. Of the compounds synthesized, only one showed activity <100 μM in this assay. Compound (S)-1 had a biochemical potency of 29 μM, a ligand efficiency (LE)34,35 of 0.18 and lipophilic efficiency (LipE)36 of 0.25 and pleasingly did not show inhibition of Mcl-2, Bcl-2 or Bcl-xl (Figure 1A). Despite the moderate potency, we were excited to have discovered a selective hit, and (S)-1 was progressed to further biophysical characterization.

Figure 1.

Biophysical characterization of (S)-1. A) Structure of cyano-acrylamide (S)-1 and Bcl family TR-FRET data. B) MS time-course at different concentrations of (S)-1. C) 1D NMR methyl region of Bfl-1 showing CSPs with 100 μM (S)-1.

Characterization of the DEL Hit Compound

Interestingly, the hit compound came from our cyano-acrylamide library and therefore had a potential reversible covalent motif (Figure 2). This library was constructed through a three-cycle synthesis. The first step was the installation of 688 diverse primary amines at the linker terminus (Cycle A). An amide coupling reaction added 503 FMOC-protected amino acids (Cycle B). FMOC deprotection, followed by a second amide coupling, installed an α-cyano-amide which could then be used in a condensation reaction with 218 aldehydes (Cycle C) and form the cyano-acrylamide reversible covalent warhead giving a total library size of 74.5 million compounds. The hit compound came from a cluster which was defined by the phosphine oxide building block at Cycle C. Further analysis of this cluster revealed no significant preference of any Cycle A building blocks, and so the Cycle B and C building blocks were chosen along with a capped dimethylamide (Figure S3). A combination of low prevalence for any individual building block at Cycle A along with an undesirable increase in MW made it attractive to synthesize the truncate.

Figure 2.

Design of the reversible covalent DEL from which cyano-acrylamide (S)-1 originated.

Knowing that Bfl-1 had a cysteine residue in the peptide binding site, and that cyano-acrylamides have been widely reported as cysteine targeting groups,26 it was hypothesized that compound 1 could be binding through a reversible covalent mechanism. To interrogate this, a mass spectrometry (MS) experiment was performed that showed dose dependent labeling of Bfl-1 in a manner consistent with the proposed reversible covalent mode of action (Figure 1B). From the MS data obtained, the KI of (S)-1 binding to Bfl-1 was determined to be 5.4 μM (Figure S4).37 Binding to Bfl-1 was also confirmed by 1D protein-observed NMR, in which the protein methyl resonances experienced significant chemical shift perturbations (CSPs) upon the addition of (S)-1 (Figure 1C). X-ray crystallography of Bfl-1 with (S)-1 was attempted, but at this point no ligand density could be observed in the BH3 site of Bfl-1 or around Cys55.

SAR Exploration

Having identified (S)-1 as a Bfl-1 inhibitor, we wanted to understand the structure–activity relationship (SAR) and determine the key drivers of potency (Table 1). The phosphine oxide substituent was intriguing—this is a rare group in medicinal chemistry, although it has become more common since the discovery of Brigatinib.38−40 It is known to be a strong H-bond acceptor (HBA). Initially, we opted to remove this group entirely ((S)-2) and unsurprisingly lost potency (IC50 > 100 μM), indicating that this was an important part of the pharmacophore. Moving the phosphine oxide around to the meta ((S)-3) and para ((S)-4) positions on the ring similarly did not improve activity at the concentrations tested. Several phosphine oxide isosteres were then explored. Sulfone (S)-5, sulfonamide (rac)-6 and amide (rac)-7 were all chosen as they could mimic the strong HBA functionality of the phosphine oxide while retaining similar spatial requirements.38 Unfortunately, these all had potencies >100 μM, again showing the importance of the phosphine oxide. At this point, it was hypothesized that the phosphine oxide was making a key interaction with the protein.

Table 1. Investigation of the DEL Cycle D SAR.

Potency data based on n ≥ 2 with SEM within 0.2 log unit, unless otherwise stated.

LogD measured via shake-flask method in octanol and water at pH = 7.4.

LE (kcal mol–1 heavy atom–1) = −0.596(ln(IC50/106))/HAC, where IC50 is expressed in μM, LipE = pIC50 – LogD.

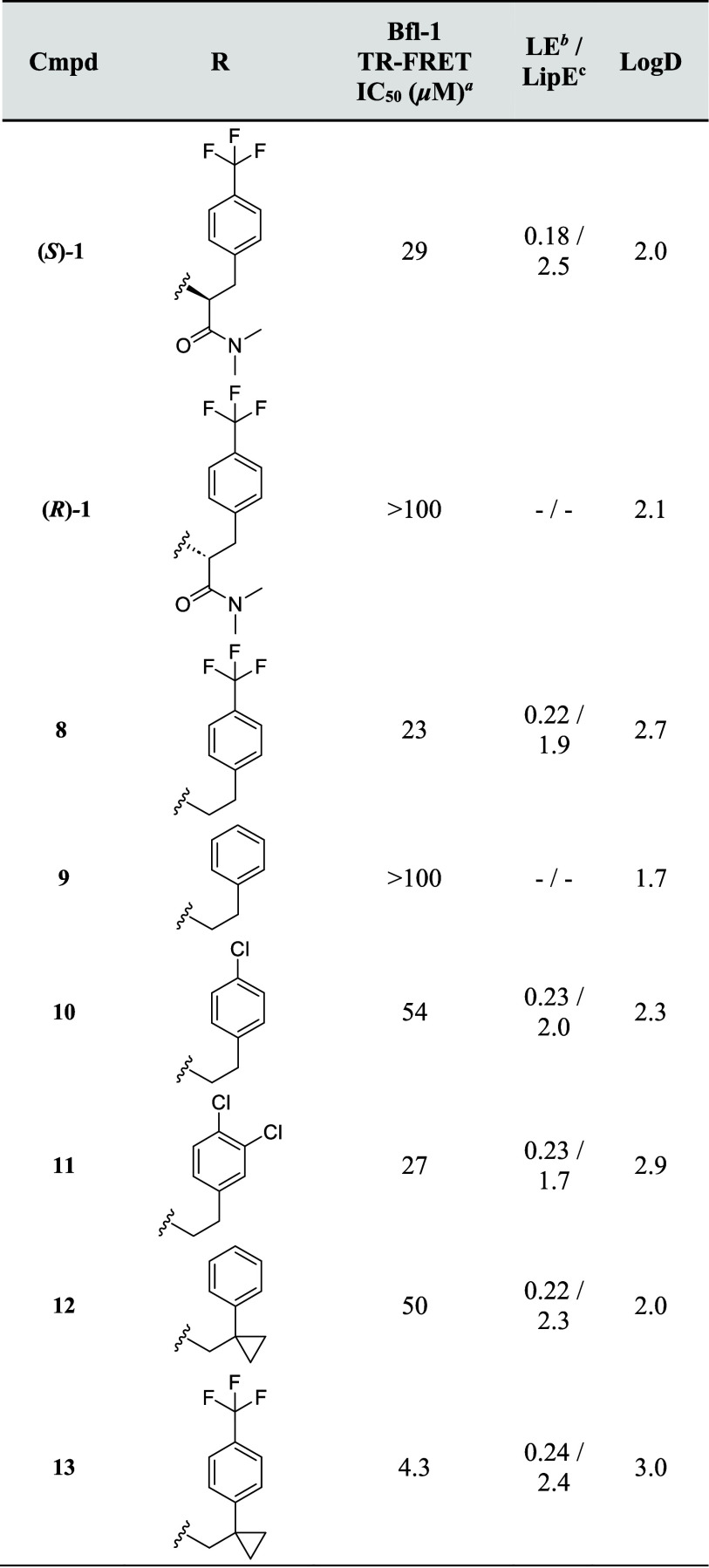

Attention then turned to exploration of the Cycle C substituent (Table 2). First, the (R)-enantiomer of compound 1 was synthesized and tested ((R)-1). Pleasingly, this was inactive, as is often observed with enantiomeric matched pairs. Next, we were interested in seeing whether removal of the amide group altogether would be tolerated. Interestingly, this compound maintained potency with the hit (8, IC50 = 23 μM), albeit with increased LogD and reduced LipE, suggesting that it was likely that (R)-1 clashed with the binding site rather than the (S)-enantiomer, conferring significant additional affinity. Removal of the para-substituent on the benzyl group gave benzyl 9, which was inactive at the concentrations tested.

Table 2. Investigation of the DEL Cycle C SAR.

Potency data based on n ≥ 2 with SEM within 0.2 log unit, unless otherwise stated.

LogD measured via shake-flask method in octanol and water at pH = 7.4.

LE (kcal mol–1 heavy atom–1) = −0.596(ln(IC50/106))/HAC, where IC50 is expressed in μM, LipE = pIC50 – LogD.

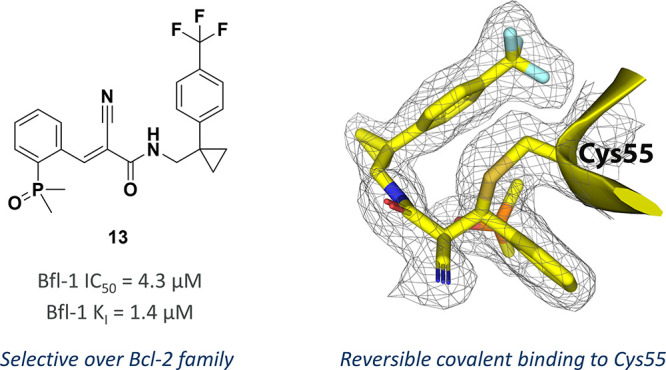

Therefore, other small lipophilic substituents were explored. Chloride 10 was active (IC50 = 54 μM) but weaker than trifluoromethyl 8; however, due to a reduction in LogD, it maintained a comparable LipE. Addition of a second chloride at the meta-position made 11 more potent but less efficient than the monochloride 10. In parallel to this bespoke chemistry optimization, a library of 51 amides was prepared to explore the SAR more thoroughly. Disappointingly, most of these were inactive; however, cyclopropyl 12 was a 50 μM inhibitor of Bfl-1. It was hypothesized that the cyclopropyl group bestowed a conformational restriction on the phenyl ring, helping it to maintain the bioactive conformation,41 and that addition of the trifluoromethyl group at the para-position would deliver a potent inhibitor. Pleasingly, combining these two groups to give cyano-acrylamide 13 delivered the first single-digit micromolar binder from this series. The improved affinity of compound 13 was confirmed by MS where the KI was determined to be 1.4 μM (Figure S5). Furthermore, no inhibition of other Bcl-2 family members was observed (Mcl-1, Bcl-2 and Bcl-xl IC50 values >100 μM). Despite an increase in lipophilicity compared to the initial hit ((S)-1), 13 maintained the LipE, improved ligand efficiency, and constituted an important step forward on the project.

As a 10-fold improvement in potency had been achieved while largely maintaining the physicochemical profile of the hit, X-ray crystallography was again attempted in the hope that it would guide further optimization. Gratifyingly, a 1.8 Å resolution crystal structure of cyano-acrylamide 13 bound to Bfl-1 was solved (Figure 3A–D). The compound was positioned at the end of the BH3 binding site and showed clear density between Cys55 and the cyanoacrylamide motif, providing further evidence of the covalent nature of the interaction. The phosphine-oxide, which has proved critical to binding during our SAR exploration, was involved in a 9-membered intramolecular hydrogen bond with the amide NH. As it has previously been thought that the phosphine oxide would be making a key interaction with Bfl-1, it was therefore curious to discover that this was not the case. Presumably the intramolecular hydrogen bond helps the compound to maintain the bioactive conformation and potentially also increases the electrophilicity of the cyano-acrylamide by pulling electron density away from the carbonyl. It was evident why both the para-substituent and the cyclopropyl groups were important for potency. The para-trifluoromethyl extended to the base of the pocket and helped fulfill the spatial requirements of the binding site, positioned into a lipophilic cleft normally occupied by the BH3 peptide. The cyclopropyl did indeed appear to help the phenyl ring adopt the desired conformation to enter this pocket. Lastly, the structure pointed toward an area for further optimization of this series. Currently, only a small portion of the BH3 binding site is occupied, and therefore future efforts should explore extending the compound in this direction. Potential handles for doing this may include the methylene between the amide NH and cyclopropyl ring or the ortho-position of the aromatic ring.

Figure 3.

X-ray crystal structure of Bfl-1 showing the binding mode of the reversible covalent compound 13 (PDB: 8RPO). A) Surface representation of Bfl-1 (yellow with gray surface) with compound 13 bound overlaid with Bim (blue) peptide from PDB deposition 2VM6.42 B) Bfl-1 pocket is shown in gray surface with the key pocket residues shown in green and compound 13 shown in yellow stick representation. C) Ribbon representation of the pocket with Cys55 highlighted in green. D) 1.8 Å resolution 2Fo – Fc electron density around the ligand contoured at 1σ clearly shows a covalent bond to Cys55.

Conclusion

Herein, we have reported the first known reversible-covalent binders to Cys55 of Bfl-1. To the best of our knowledge, this is also the first reported identification of a cyano-acrylamide reversible covalent binder identified using a DEL screen. Reversible covalent libraries could have an important place in DEL screening as they allow the discovery of covalent compounds without the need for a different workflow or additional irreversible covalent DELs, as is the case for irreversible covalent screens.30 The compounds identified from the screen were then fully characterized using biophysical and biochemical techniques, which fully supported the reversible covalent mechanism of action. The SAR of cyano-acrylamide (S)-1 was explored and a 10-fold improvement in potency was achieved to give a single-digit micromolar compound (13) for further optimization. An X-ray crystal structure was solved which illuminated the binding mode and provided potential strategies for future structure-based design.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Erin Braybrooke and Paul Davey for assistance collecting HRMS data. We thank Benjamin C. Whitehurst for advice during preparation of the manuscript.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- Bcl-2

B-cell lymphoma 2

- Bcl-xl

B-cell lymphoma-extra large

- Bfl-1

Bcl2-related protein A1

- BH3

Bcl homology 3

- CSP

chemical shift perturbation

- DEL

DNA encoded library

- Mcl-1

myeloid cell leukemia 1

- MS

mass spectrometry

- PPI

protein–protein interface

- SEC-MALS

size exclusion chromatography with multi-angle static light scattering

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.4c00113.

Experimental procedures for the DEL screen, biochemical and biophysical techniques, preparation of all compounds, NMR spectra of all compounds, and LCMS purity traces of all compounds (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Special Issue

Published as part of ACS Medicinal Chemistry Lettersvirtual special issue “Exploring Covalent Modulators in Drug Discovery and Chemical Biology”.

Supplementary Material

References

- Youle R. J.; Strasser A. The BCL-2 protein family: opposing activities that mediate cell death. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9 (1), 47–59. 10.1038/nrm2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasser A. The role of BH3-only proteins in the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005, 5 (3), 189–200. 10.1038/nri1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L.; Willis S. N.; Wei A.; Smith B. J.; Fletcher J. I.; Hinds M. G.; Colman P. M.; Day C. L.; Adams J. M.; Huang D. C. S. Differential Targeting of Prosurvival Bcl-2 Proteins by Their BH3-Only Ligands Allows Complementary Apoptotic Function. Mol. Cell 2005, 17 (3), 393–403. 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons M. J.; Fan G.; Zong W. X.; Degenhardt K.; White E.; Gélinas C. Bfl-1/A1 functions, similar to Mcl-1, as a selective tBid and Bak antagonist. Oncogene 2008, 27 (10), 1421–1428. 10.1038/sj.onc.1210771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riker A. I.; Enkemann S. A.; Fodstad O.; Liu S.; Ren S.; Morris C.; Xi Y.; Howell P.; Metge B.; Samant R. S.; Shevde L. A.; Li W.; Eschrich S.; Daud A.; Ju J.; Matta J. The gene expression profiles of primary and metastatic melanoma yields a transition point of tumor progression and metastasis. BMC Med. Genet. 2008, 1 (1), 13. 10.1186/1755-8794-1-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon H.-S.; Hong S.-H.; Kang H.-J.; Ko B. K.; Ahn S.-H.; Huh J.-R. Bfl-1 Gene Expression in Breast Cancer: Its Relationship with other Prognostic Factors. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2003, 18 (2), 225–230. 10.3346/jkms.2003.18.2.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X.; Mao Z.; Zhu J.; Liu H.; Chen F. lncRNA PANTR1 Upregulates BCL2A1 Expression to Promote Tumorigenesis and Warburg Effect of Hepatocellular Carcinoma through Restraining miR-587. J. Immunol. Res. 2021, 2021, 1736819 10.1155/2021/1736819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Olsson A.; Norberg M.; ökvist A.; Derkow K.; Choudhury A.; Tobin G.; Celsing F.; österborg A.; Rosenquist R.; Jondal M.; Osorio L. M. Upregulation of bfl-1 is a potential mechanism of chemoresistance in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br. J. Cancer 2007, 97 (6), 769–777. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong F.; Kim K.; Konopleva M. Y. Venetoclax resistance: mechanistic insights and future strategies. Cancer Drug Resist 2022, 5 (2), 380–400. 10.20517/cdr.2021.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H.; Nakauchi Y.; Köhnke T.; Stafford M.; Bottomly D.; Thomas R.; Wilmot B.; McWeeney S. K.; Majeti R.; Tyner J. W. Integrated analysis of patient samples identifies biomarkers for venetoclax efficacy and combination strategies in acute myeloid leukemia. Nat. Cancer 2020, 1 (8), 826–839. 10.1038/s43018-020-0103-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue X.; Chen Q.; He J. Combination strategies to overcome resistance to the BCL2 inhibitor venetoclax in hematologic malignancies. Cancer Cell Int. 2020, 20 (1), 524. 10.1186/s12935-020-01614-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G.; Diepstraten S. T.; Herold M. J. Last but not least: BFL-1 as an emerging target for anti-cancer therapies. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2022, 50 (4), 1119–1128. 10.1042/BST20220153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korshavn K. J.; Wales T. E.; Bird G. H.; Engen J. R.; Walensky L. D. A redox switch regulates the structure and function of anti-apoptotic BFL-1. Nature Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020, 27 (9), 781–789. 10.1038/s41594-020-0458-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N.; Wang D.; Lian C.; Zhao R.; Tu L.; Zhang Y.; Liu J.; Zhu H.; Yu M.; Wan C.; Li D.; Li S.; Yin F.; Li Z. Selective Covalent Targeting of Anti-apoptotic BFL-1 by a Sulfonium-Tethered Peptide. Chembiochem 2021, 22 (2), 340–344. 10.1002/cbic.202000473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huhn A. J.; Guerra R. M.; Harvey E. P.; Bird G. H.; Walensky L. D. Selective Covalent Targeting of Anti-Apoptotic BFL-1 by Cysteine-Reactive Stapled Peptide Inhibitors. Cell Chem. Biol. 2016, 23 (9), 1123–1134. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2016.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey E. P.; Hauseman Z. J.; Cohen D. T.; Rettenmaier T. J.; Lee S.; Huhn A. J.; Wales T. E.; Seo H.-S.; Luccarelli J.; Newman C. E.; Guerra R. M.; Bird G. H.; Dhe-Paganon S.; Engen J. R.; Wells J. A.; Walensky L. D. Identification of a Covalent Molecular Inhibitor of Anti-apoptotic BFL-1 by Disulfide Tethering. Cell Chem. Biol. 2020, 27 (6), 647–656.e6. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2020.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X.; Yan Z.; Zhou F.; Lou J.; Lyu X.; Ren X.; Zeng Z.; Liu C.; Zhang S.; Zhu D.; Huang H.; Yang J.; Zhao Y. Discovery of a selective and covalent small-molecule inhibitor of BFL-1 protein that induces robust apoptosis in cancer cells. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 236, 114327 10.1016/j.ejmech.2022.114327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kump K. J.; Miao L.; Mady A. S. A.; Ansari N. H.; Shrestha U. K.; Yang Y.; Pal M.; Liao C.; Perdih A.; Abulwerdi F. A.; Chinnaswamy K.; Meagher J. L.; Carlson J. M.; Khanna M.; Stuckey J. A.; Nikolovska-Coleska Z. Discovery and Characterization of 2,5-Substituted Benzoic Acid Dual Inhibitors of the Anti-apoptotic Mcl-1 and Bfl-1 Proteins. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63 (5), 2489–2510. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mady A. S. A.; Liao C.; Bajwa N.; Kump K. J.; Abulwerdi F. A.; Lev K. L.; Miao L.; Grigsby S. M.; Perdih A.; Stuckey J. A.; Du Y.; Fu H.; Nikolovska-Coleska Z. Discovery of Mcl-1 inhibitors from integrated high throughput and virtual screening. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8 (1), 10210 10.1038/s41598-018-27899-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu A.-L.; Sperandio O.; Pottiez V.; Balzarin S.; Herlédan A.; Elkaïm J. O.; Fogeron M.-L.; Piveteau C.; Dassonneville S.; Deprez B.; Villoutreix B. O.; Bonnefoy N.; Leroux F. Identification of Small Inhibitory Molecules Targeting the Bfl-1 Anti-Apoptotic Protein That Alleviates Resistance to ABT-737. SLAS Discov 2014, 19 (7), 1035–1046. 10.1177/1087057114534070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gironda-Martínez A.; Donckele E. J.; Samain F.; Neri D. DNA-Encoded Chemical Libraries: A Comprehensive Review with Succesful Stories and Future Challenges. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. 2021, 4 (4), 1265–1279. 10.1021/acsptsci.1c00118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satz A. L.; Brunschweiger A.; Flanagan M. E.; Gloger A.; Hansen N. J. V.; Kuai L.; Kunig V. B. K.; Lu X.; Madsen D.; Marcaurelle L. A.; Mulrooney C.; O’Donovan G.; Sakata S.; Scheuermann J. DNA-encoded chemical libraries. Nat. Rev. Methods Primer 2022, 2 (1), 3. 10.1038/s43586-021-00084-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kunig V. B. K.; Potowski M.; Klika Škopić M.; Brunschweiger A. Scanning Protein Surfaces with DNA-Encoded Libraries. ChemMedChem. 2021, 16 (7), 1048–1062. 10.1002/cmdc.202000869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffek M.; Helgason E.; Popovych N.; Rougé L.; Bruning J. M.; Li K. S.; Burdick D. J.; Cai J.; Crawford T.; Xue J.; Decurtins W.; Fang C.; Grubers F.; Holliday M. J.; Langley A.; Petersen A.; Satz A. L.; Song A.; Stoffler D.; Strebel Q.; Tom J. Y. K.; Skelton N.; Staben S. T.; Wichert M.; Mulvihill M. M.; Dueber E. C. A Multifaceted Hit-Finding Approach Reveals Novel LC3 Family Ligands. Biochemistry 2023, 62 (3), 633–644. 10.1021/acs.biochem.1c00682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan S.; Miller R. M.; Tian B.; Mullins R. D.; Jacobson M. P.; Taunton J. Design of Reversible, Cysteine-Targeted Michael Acceptors Guided by Kinetic and Computational Analysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136 (36), 12624–12630. 10.1021/ja505194w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller R. M.; Paavilainen V. O.; Krishnan S.; Serafimova I. M.; Taunton J. Electrophilic Fragment-Based Design of Reversible Covalent Kinase Inhibitors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135 (14), 5298–5301. 10.1021/ja401221b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw J. M.; McFarland J. M.; Paavilainen V. O.; Bisconte A.; Tam D.; Phan V. T.; Romanov S.; Finkle D.; Shu J.; Patel V.; Ton T.; Li X.; Loughhead D. G.; Nunn P. A.; Karr D. E.; Gerritsen M. E.; Funk J. O.; Owens T. D.; Verner E.; Brameld K. A.; Hill R. J.; Goldstein D. M.; Taunton J. Prolonged and tunable residence time using reversible covalent kinase inhibitors. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2015, 11 (7), 525–531. 10.1038/nchembio.1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serafimova I. M.; Pufall M. A.; Krishnan S.; Duda K.; Cohen M. S.; Maglathlin R. L.; McFarland J. M.; Miller R. M.; Frödin M.; Taunton J. Reversible targeting of noncatalytic cysteines with chemically tuned electrophiles. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2012, 8 (5), 471–476. 10.1038/nchembio.925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu D.; Richters A.; Rauh D. Structure-based design and synthesis of covalent-reversible inhibitors to overcome drug resistance in EGFR. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015, 23 (12), 2767–2780. 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilinger J. P.; Archna A.; Augustin M.; Bergmann A.; Centrella P. A.; Clark M. A.; Cuozzo J. W.; Däther M.; Guié M.-A.; Habeshian S.; Kiefersauer R.; Krapp S.; Lammens A.; Lercher L.; Liu J.; Liu Y.; Maskos K.; Mrosek M.; Pflügler K.; Siegert M.; Thomson H. A.; Tian X.; Zhang Y.; Konz Makino D. L.; Keefe A. D. Novel irreversible covalent BTK inhibitors discovered using DNA-encoded chemistry. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2021, 42, 116223 10.1016/j.bmc.2021.116223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z.; Grady L. C.; Ding Y.; Lind K. E.; Davie C. P.; Phelps C. B.; Evindar G. Development of a Selection Method for Discovering Irreversible (Covalent) Binders from a DNA-Encoded Library. SLAS Discov 2019, 24 (2), 169–174. 10.1177/2472555218808454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas S. C. C.; Blackwell J. H.; Hewitt S. H.; Semple H.; Whitehurst B. C.; Xu H. Covalent hits and where to find them. SLAS Discov 2024, 29, 100142. 10.1016/j.slasd.2024.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannes J. W.; Bates S.; Beigie C.; Belmonte M. A.; Breen J.; Cao S.; Centrella P. A.; Clark M. A.; Cuozzo J. W.; Dumelin C. E.; Ferguson A. D.; Habeshian S.; Hargreaves D.; Joubran C.; Kazmirski S.; Keefe A. D.; Lamb M. L.; Lan H.; Li Y.; Ma H.; Mlynarski S.; Packer M. J.; Rawlins P. B.; Robbins D. W.; Shen H.; Sigel E. A.; Soutter H. H.; Su N.; Troast D. M.; Wang H.; Wickson K. F.; Wu C.; Zhang Y.; Zhao Q.; Zheng X.; Hird A. W. Structure Based Design of Non-Natural Peptidic Macrocyclic Mcl-1 Inhibitors. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 8 (2), 239–244. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.6b00464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abad-Zapatero C.; Metz J. T. Ligand efficiency indices as guideposts for drug discovery. Drug Discovery Today 2005, 10 (7), 464–469. 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03386-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins A. L.; Groom C. R.; Alex A. Ligand efficiency: a useful metric for lead selection. Drug Discovery Today 2004, 9 (10), 430–431. 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson T. W.; Gallego R. A.; Edwards M. P. Lipophilic Efficiency as an Important Metric in Drug Design. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61 (15), 6401–6420. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee P.; Botello-Smith W. M.; Zhang H.; Qian L.; Alsamarah A.; Kent D.; Lacroix J. J.; Baudry M.; Luo Y. Can Relative Binding Free Energy Predict Selectivity of Reversible Covalent Inhibitors?. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139 (49), 17945–17952. 10.1021/jacs.7b08938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkbeiner P.; Hehn J. P.; Gnamm C. Phosphine Oxides from a Medicinal Chemist’s Perspective: Physicochemical and in Vitro Parameters Relevant for Drug Discovery. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63 (13), 7081–7107. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W.-S.; Liu S.; Zou D.; Thomas M.; Wang Y.; Zhou T.; Romero J.; Kohlmann A.; Li F.; Qi J.; Cai L.; Dwight T. A.; Xu Y.; Xu R.; Dodd R.; Toms A.; Parillon L.; Lu X.; Anjum R.; Zhang S.; Wang F.; Keats J.; Wardwell S. D.; Ning Y.; Xu Q.; Moran L. E.; Mohemmad Q. K.; Jang H. G.; Clackson T.; Narasimhan N. I.; Rivera V. M.; Zhu X.; Dalgarno D.; Shakespeare W. C. Discovery of Brigatinib (AP26113), a Phosphine Oxide-Containing, Potent, Orally Active Inhibitor of Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59 (10), 4948–4964. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stambirskyi M. V.; Kostiuk T.; Sirobaba S. I.; Rudnichenko A.; Titikaiev D. L.; Dmytriv Y. V.; Kuznietsova H.; Pishel I.; Borysko P.; Mykhailiuk P. K. Phosphine Oxides (−POMe2) for Medicinal Chemistry: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86 (18), 12783–12801. 10.1021/acs.joc.1c01413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer M. R.; Di Fruscia P.; Lucas S. C. C.; Michaelides I. N.; Nelson J. E.; Storer R. I.; Whitehurst B. C. Put a ring on it: application of small aliphatic rings in medicinal chemistry. RSC Med. Chem. 2021, 12 (4), 448–471. 10.1039/D0MD00370K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman M. D.; Nyman T.; Welin M.; Lehtiö L.; Flodin S.; Trésaugues L.; Kotenyova T.; Flores A.; Nordlund P. Completing the family portrait of the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins: Crystal structure of human Bfl-1 in complex with Bim. FEBS Lett. 2008, 582 (25–26), 3590–3594. 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.