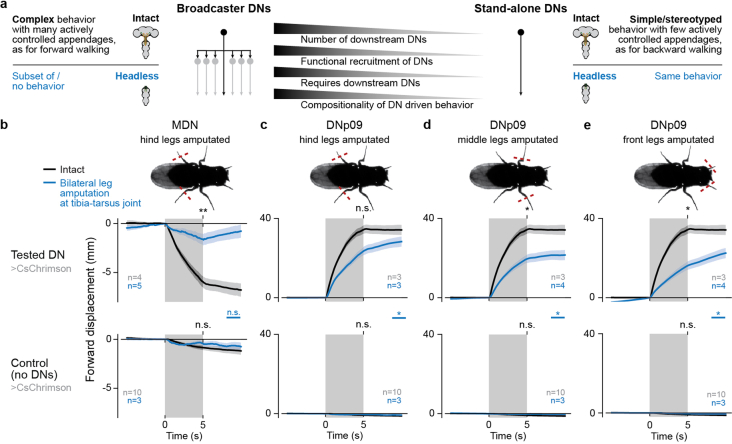

Extended Data Fig. 10. Backward locomotion depends on the active actuation of fewer appendages than forward locomotion.

(a) Illustration of the hypothesis that behavioral complexity/compositionality correlates with underlying DN network size. (b-e, top row) Cartoon schema illustrating legs that were bilaterally amputated at the level of the tibia-tarsus joint. Indicated are optogenetically activated DNs. Shown below is the cumulative fictive forward displacement for tethered flies before, after, and during optogenetic stimulation (gray region) for either optogenetic stimulation of (b-e, middle row) the DN in question, or (b-e, bottom row) a control animal with no GAL4 driver. Data are shown for traces for both amputated (blue) and intact control (black traces) flies. Flies were optogenetically stimulated 10 times. Shaded areas represent the 95% confidence interval of the mean. Shown are two-sided Mann-Whitney U tests comparing the trial-wise mean of intact versus leg amputated animals (black asterisks and ‘n.s.’) as well as the leg amputated DN > GAL4 versus leg amputated control flies (blue asterisks and ‘n.s.’). *** Indicates p < 0.001, ** indicates p < 0.01, * indicates p < 0.05, n.s. indicates p ≥ 0.05; for exact p-values see Supplementary Table 6. (b) Amputation of the hind legs is sufficient to prevent flies from walking backward upon MDN optogenetic stimulation. Residual backward displacement results from struggle-associated noise and is not statistically distinguishable from control animal backward displacement. (c-e) Amputation of either the hind-, mid- or forelegs does not prevent forward walking but only reduces forward walking velocity.