Abstract

Background:

Medication use during pregnancy has increased in the U.S. despite the lack of safety data for many medications.

Objective:

To inform research priorities by examining trends in medication use during pregnancy and identifying gaps in safety information among the most commonly prescribed medications.

Study Design:

We identified population-based cohorts of commercially (MarketScan 2011–2020) and publicly (MAX/TAF 2011–2018) insured pregnancies ending in livebirth from two healthcare utilization databases. Medication use was based on filled prescriptions between the date of last menstrual period (LMP) through delivery, as well as pre-LMP and during specific trimesters. We also included a cross-sectional representative sample of pregnancies ascertained by the National Health and Nutrition Examination Study (NHANES 2011–2020), with information on prescription medication use during the preceding month obtained through maternal interviews. The Teratogen Information System (TERIS) was used to classify the available evidence on teratogenic risk.

Results:

Among over 3 million pregnancies, the medications most commonly dispensed at any time during pregnancy were analgesics, antibiotics, and antiemetics. The top medications were ondansetron (16.8%), amoxicillin (13.5%) and azithromycin (12.4%) in MarketScan, nitrofurantoin (22.2%), acetaminophen (21.3%; the majority as part of acetaminophen-hydrocodone products), and ondansetron (19.5%) in MAX/TAF, and levothyroxine (5.0%), sertraline (2.9%), and insulin (2.9%) in NHANES. The most commonly dispensed suspected teratogens during the first trimester were antithyroid medications. The use of antidiabetic and psychotropic medications has continued to increase in the U.S. during the last decade, opioids dispensation has decreased by half, and antibiotics and antiemetics continue to be common. For one-quarter of medications, there is insufficient evidence available to characterize their safety profile in pregnancy.

Conclusions:

There is a need for more drug research in pregnant patients. Future research should focus on anti-infectives with high utilization and limited level of evidence on safety for use during pregnancy. While the lack of evidence is not evidence for safety, it is not evidence for risk either. In many instances the benefits outweigh the risks when these medications are used clinically; and some of the medications with no proven safety may be necessary to treat patients.

Keywords: gestation, TERIS, utilization, pharmacoepidemiology, teratogens, perinatal

INTRODUCTION

Medication use during pregnancy has increased over the last decades in the United States (U.S.).1 In previous decades, the most commonly used medications were analgesics, antibiotics, and antiemetics;2–4 although the specific medications changed over time.1 Furthermore, medications for chronic conditions, such as levothyroxine and insulin, have been on the rise in recent years.2,5 Of particular concern with respect to medication use in pregnancy are the potential teratogenic effects when they are used during organogenesis. Studies based on both self-report and prescription claims data consistently found that approximately 50% of pregnant women took at least one medication, excluding vitamins, during the first trimester.1–3,6

By 2007, 63% of medications used in the first trimester had what was considered very limited to fair evidence in quality and quantity regarding teratogenic risk according to the TERIS classification.4 Post Marketing Requirements (PMR) for pregnancy and lactation studies provide an opportunity to better understand the safety of medications used during pregnancy, though only 16% of drugs that may be used in females of reproductive potential have been issued a PMR over the past 15 years.7 While there are several studies on the utilization and safety of medications in the past decades, fewer studies exist for the post 2010 period. As such, with increasing prevalence of chronic diseases that may require initiation and continuation of pharmacologic treatment during pregnancy for optimal maternal health,8 additional research is needed to fill the remaining gaps in knowledge on fetal effects. Among medications lacking safety information, research priorities should target drugs whose potential risks could have the largest clinical and public health impact, which translates to those drugs most commonly used during pregnancy overall and during the first trimester in particular. This study updates trends in utilization and the level of safety evidence available for the most common prescription medications in pregnancy.

METHODS

Study Design and Data Sources

Healthcare utilization databases

The Merative MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database includes the under-65 working population and dependents who receive benefits from over 100 large private employers and health plans in all 50 states.9 The Medicaid Analytic eXtract/Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System (T-MSIS) Analytic Files (MAX/TAF) includes data on publicly insured Medicaid enrollees nationwide.3 These databases include inpatient and outpatient medical claims that are linked to outpatient prescription drug claims and person-level enrollment information.

National Health and Nutrition Examination Study (NHANES)

NHANES is a cross-sectional survey of the non-institutionalized U.S. population. NHANES consists of in-person household interviews and follow up physical examinations, conducted yearly and released publicly in a series of two-year cycles. Pregnancy status is self-reported or confirmed through a urine sample during the physical exam. Past month prescription medication use is assessed through in-person interviews, during which participants are asked to show the medication container so interviewers can record relevant information.

Study Population and Subgroups

We included women aged 12–55 years with delivery-related healthcare claims linked to livebirths from MarketScan (2011 to 2020) and MAX/TAF (2011 to 2018).9–11 We required continuous enrollment with prescription benefits from 90 days prior to the estimated date of last menstrual period (LMP) through delivery. LMP was defined based on a validated algorithm.12 Multiple pregnancies of the same enrollee during the study period were eligible for inclusion. For subgroup analyses, we stratified the population by maternal age at LMP (≤25, >25 and <35, ≥35 years) and LMP year (2011–2013 and 2016–2018 for both databases, and 2019–2020 for MarketScan).

Women in NHANES (2011–2020), aged 20–44 years, who self-reported being pregnant in the questionnaire or had a positive urine pregnancy test were included in our study. We did not define subgroups for NHANES due to small numbers.

Medication Exposures

Medication use was defined as a record of a generic regardless of the number of active ingredients (e.g., exposure to amoxicillin/clavulanate counted as one exposure to amoxicillin and another to clavulanate) and the formulation (e.g., all salts of amoxicillin were considered as amoxicillin). We excluded medications used exclusively topically, locally, or intravenously (IV), but included those used intravaginally. We further excluded vaccines, oxygen, blood-products, and supplements. Medications dispensed at the time of delivery were not included.

In MarketScan and MAX/TAF, medications were identified using generic names corresponding to the national drug codes (NDCs) recorded in pharmacy claims. In NHANES, reported medications were classified using the Cerner Multum’s Lexicon Plus drug database. Medications/classes of particular interest during pregnancy based on clinical expertise and a review of the scientific literature were a priori selected to be included in the analysis regardless of their ranking (Table S1): antiemetics, antidiabetics, psychotropics, analgesics, triptans, and known/suspected teratogens.

We used the Teratogen Information System (TERIS) to classify the available evidence on teratogenic risk (https://deohs.washington.edu/teris/). TERIS provides a summary rating of clinical and experimental information for the level of evidence on teratogenic risk for medications generated by the TERIS Advisory Board.13 In this analysis, we considered three combined categories for the level of evidence, None to Fair (i.e., None, None to Limited, Limited, and Limited to Fair), Fair to Good (i.e., Fair, Fair to Good), and Good to Excellent (i.e., Good, Good to Excellent, Excellent) to rate the most common medications used any time during pregnancy and during the first trimester (Text S1).

For medication exposures in MarketScan and MAX/TAF, we defined five periods of interest, with the later three being approximations of gestational trimesters: any time during pregnancy (LMP to delivery), pre-LMP (LMP-90 days to LMP), first trimester (LMP+1 to LMP+90 days), second trimester (LMP+91 days to LMP+180 days), and third trimester (LMP+181 days to delivery). For NHANES, we included medication exposures based on participants responses to the following questions during their interview: “in the past month, have you used or taken medication for which a prescription is needed?” Data were unavailable to determine the trimester of pregnancy.

Statistical Analysis

We used utilization proportions, defined as the number of pregnancies exposed to a certain medication out of all pregnancies, to identify the 15 most commonly dispensed medications any time during pregnancy (MarketScan, MAX/TAF, and NHANES), by period of interest, and by pre-specified subgroups (MarketScan and MAX/TAF). We also used utilization proportions to quantify the use of medications with known/suspected teratogenic effects during pre-LMP and first trimester (MarketScan and MAX/TAF). Additionally, we examined temporal trends for use at any time during pregnancy from 2011 to 2020 for MarketScan and 2011 to 2017 for MAX/TAF (2018 data was not included due to small sample size).

All NHANES analyses were weighted according to the National Center for Health Statistics’ recommendations to represent the U.S. population and to account for its complex design.14 All analyses were conducted in R (version 4.2.2).

Ethics and approvals

The study received ethics board approval from the Mass General Brigham and Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health Institutional Review Boards (Boston, Massachusetts) and data use agreements were in place with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and Merative MarketScan.

RESULTS

The MarketScan cohort included a total of 1,754,125 pregnancies with an average maternal age of 29.8 years while the MAX/TAF cohort included 1,475,321 pregnancies with an average maternal age of 25.6 years. In NHANES, of the 415 pregnant participants, 279 (67.2%) completed the module on prescription medication use in the past month and had an average age of 30.4 years.

Most common medications any time during pregnancy

Antibiotics and analgesics were the most common classes (Table 1). The top medications were ondansetron (16.8%), amoxicillin (13.5%) and azithromycin (12.4%) in MarketScan, nitrofurantoin (22.2%), acetaminophen (21.3%; the majority as part of acetaminophen-hydrocodone products), and ondansetron (19.5%) in MAX/TAF, and levothyroxine (5.0%), sertraline (2.9%), and insulin (2.9%) in NHANES.

Table 1:

Top 15 commonly used prescription medications any time during pregnancy among ages 12–54 years in MarketScan (2011–2020), MAX/TAF (2011–2018), and 20–44 years NHANES (2011–2020)

| MarketScan | MAX/TAF | NHANES1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 1,754,125) | (n = 1,475,321) | (n = 279) | ||||

| Rank | Medication | % | Medication | % | Medication | % |

|

| ||||||

| 1 | Ondansetron | 16.8 | Nitrofurantoin | 22.2 | Levothyroxine | 5.0 |

| 2 | Amoxicillin | 13.5 | Acetaminophen2 | 21.3 | Sertraline | 2.9 |

| 3 | Azithromycin | 12.4 | Ondansetron | 19.5 | Insulin | 2.9 |

| 4 | Nitrofurantoin | 11.3 | Metronidazole | 18.8 | Montelukast | 2.8 |

| 5 | Acetaminophen2 | 9.1 | Amoxicillin | 17.7 | Metformin | 2.7 |

| 6 | Progesterone | 8.3 | Azithromycin | 15.7 | Ondansetron | 2.5 |

| 7 | Promethazine | 7.4 | Cephalexin | 13.4 | Doxylamine/Pyridoxine | 1.9 |

| 8 | Metronidazole | 6.9 | Docusate | 12.9 | Nitrofurantoin | 1.8 |

| 9 | Levothyroxine | 6.3 | Promethazine | 12.4 | Tramadol | 1.5 |

| 10 | Cephalexin | 6.0 | Fluconazole | 9.2 | Levalbuterol | 1.3 |

| 11 | Estradiol | 5.5 | Albuterol | 8.9 | Ethinyl Estradiol | 1.2 |

| 12 | Fluconazole | 5.4 | Hydrocodone | 8.7 | Bupropion | 1.1 |

| 13 | Terconazole | 4.7 | Terconazole | 8.2 | Hydrocodone | 1.1 |

| 14 | Valacyclovir | 4.6 | Codeine | 7.2 | Glyburide | 1.0 |

| 15 | Hydrocodone | 4.4 | Metoclopramide | 6.4 | Amoxicillin | 1.0 |

| Colors (TERIS level of available evidence on teratogenic risk): | None to Limited to Fair | Fair to Good | Good to Excellent | |||

NHANES: National Health and Nutrition Examination Study. NHANES does not include over-the-counter medications even if they were prescribed (e.g., acetaminophen)

Primarily with opioid formulations that require prescription

Medication dispensing across pregnancy periods

Some medications were among the topmost common both pre-LMP and throughout pregnancy in both cohorts (e.g., acetaminophen, amoxicillin), only in MarketScan (levothyroxine and sertraline) or only in MAX/TAF (metronidazole and cephalexin) [Table 2]. Other common medications pre-LMP became less common throughout pregnancy (hydrocodone and ibuprofen) or even disappeared from the top-15 after the first trimester (estradiol, progesterone, and doxycycline in MarketScan; trimethoprim, ciprofloxacin, and oxycodone in MAX/TAF). In both cohorts, ondansetron dispensations peaked during the first trimester but remained high during the second and third; and nitrofurantoin became common during the three trimesters.

Table 2.

Top 15 commonly used prescription medications throughout pregnancy among ages 12–54 years in MarketScan (2011–2020) and MAX/TAF (2011–2018)

| Rank | Pre-LMP | 1st Trimester | 2nd Trimester | 3rd Trimester | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medication | % | Medication | % | Medication | % | Medication | % | |

|

| ||||||||

| MarketScan | ||||||||

| 1 | Estradiol | 12.9 | Ondansetron | 12.7 | Ondansetron | 6.4 | Levothyroxine | 5.5 |

| 2 | Acetaminophen | 6.0 | Progesterone | 7.7 | Levothyroxine | 5.6 | Azithromycin | 4.9 |

| 3 | Amoxicillin | 5.5 | Amoxicillin | 5.6 | Amoxicillin | 5.1 | Amoxicillin | 4.6 |

| 4 | Azithromycin | 5.2 | Levothyroxine | 5.5 | Azithromycin | 4.7 | Acetaminophen | 4.0 |

| 5 | Levothyroxine | 4.5 | Estradiol | 5.4 | Nitrofurantoin | 4.4 | Nitrofurantoin | 3.7 |

| 6 | Hydrocodone | 4.2 | Promethazine | 5.1 | Acetaminophen | 3.7 | Valacyclovir | 3.5 |

| 7 | Progesterone | 3.5 | Nitrofurantoin | 4.8 | Metronidazole | 2.8 | Ondansetron | 3.3 |

| 8 | Doxycycline | 3.3 | Azithromycin | 4.4 | Promethazine | 2.4 | Fluconazole | 2.5 |

| 9 | Fluconazole | 3.0 | Doxycycline | 3.8 | Cephalexin | 2.1 | Metronidazole | 2.5 |

| 10 | Ibuprofen | 2.8 | Acetaminophen | 3.5 | Albuterol | 1.9 | Cephalexin | 2.2 |

| 11 | Fluticasone | 2.5 | Metronidazole | 2.6 | Doxylamine | 1.9 | Terconazole | 2.2 |

| 12 | Methylprednisolone | 2.5 | Cephalexin | 2.3 | Fluconazole | 1.9 | Sertraline | 1.9 |

| 13 | Prednisone | 2.2 | Fluconazole | 1.9 | Terconazole | 1.9 | Hydrocodone | 1.8 |

| 14 | Sertraline | 2.1 | Hydrocodone | 1.9 | Sertraline | 1.7 | Albuterol | 1.7 |

| 15 | Albuterol | 2.0 | Sertraline | 1.9 | Fluticasone | 1.4 | Nifedipine | 1.7 |

| MAX/TAF | ||||||||

| 1 | Acetaminophen | 12.9 | Ondansetron | 13.9 | Acetaminophen | 9.8 | Acetaminophen | 8.6 |

| 2 | Ibuprofen | 9.9 | Acetaminophen | 10.0 | Nitrofurantoin | 9.2 | Nitrofurantoin | 7.9 |

| 3 | Hydrocodone | 8.2 | Nitrofurantoin | 9.7 | Metronidazole | 8.0 | Metronidazole | 6.8 |

| 4 | Amoxicillin | 6.9 | Promethazine | 8.7 | Ondansetron | 7.8 | Docusate | 6.8 |

| 5 | Metronidazole | 5.1 | Metronidazole | 7.5 | Amoxicillin | 7.1 | Amoxicillin | 6.2 |

| 6 | Azithromycin | 4.9 | Amoxicillin | 7.3 | Azithromycin | 6.3 | Azithromycin | 5.7 |

| 7 | Albuterol | 4.2 | Azithromycin | 6.2 | Docusate | 5.9 | Cephalexin | 5.1 |

| 8 | Fluconazole | 3.7 | Docusate | 5.5 | Cephalexin | 4.9 | Fluconazole | 4.7 |

| 9 | Sulfamethoxazole/Trimethoprim | 3.3 | Cephalexin | 5.3 | Albuterol | 4.5 | Ondansetron | 4.6 |

| 10 | Codeine | 2.9 | Hydrocodone | 4.8 | Promethazine | 4.3 | Terconazole | 4.2 |

| 11 | Naproxen | 2.9 | Metoclopramide | 4.4 | Fluconazole | 3.4 | Ranitidine | 4.2 |

| 12 | Oxycodone | 2.9 | Albuterol | 4.2 | Terconazole | 3.4 | Albuterol | 4.0 |

| 13 | Ciprofloxacin | 2.7 | Ibuprofen | 3.7 | Hydrocodone | 3.4 | Hydrocodone | 3.0 |

| 14 | Cephalexin | 2.6 | Fluconazole | 2.8 | Codeine | 3.0 | Codeine | 2.9 |

| 15 | Estradiol | 0.1 | Estradiol | 0.1 | Ranitidine | 2.6 | Valacyclovir | 2.7 |

|

| ||||||||

| Colors (TERIS level of available evidence on teratogenic risk): | None to Limited to Fair | Fair to Good | Good to Excellent | |||||

Medication dispensing across subgroups

The top medications by age groups were similar to the main results (Table S2). Among those ≥35 years in MarketScan, levothyroxine (10.4%) and methylprednisolone (2.6%) were top medications at any time during pregnancy. The top medications by LMP year groups were also similar to the main results (Table S2). However, the utilization of ondansetron and acetaminophen-hydrocodone products decreased over time in both cohorts.

TERIS Level of Evidence

Among the topmost common medications at any time during pregnancy, approximately one-quarter of medications had none to fair evidence from TERIS (Table 1). Similarly, during the first trimester, 4 of the 15 top medications in MarketScan and 3 of the top 15 medications in MAX/TAF were classified as having none to fair safety evidence (Table 2). Most of these medications were anti-infectives, including antibiotics (e.g., metronidazole, doxycycline, cephalexin), antivirals (e.g., valacyclovir), and antifungals (e.g., fluconazole, terconazole).

Dispensing patterns of medications with teratogenic effects

Twenty known/suspected teratogens were examined during pre-LMP and the first trimester (Table 3). Of the 20, seven had no dispensations in MarketScan or MAX/TAF. The proportion of pregnancies with dispensations was lower during the first trimester than pre-LMP for most; similar for mercaptopurine, and greater for propylthiouracil.

Table 3.

Commonly used prescription medications with known/suspected teratogenic effects during pre-LMP and 1st trimester in MarketScan (2011–2020) and MAX/TAF (2011–2018)

| MarketScan | MAX/TAF | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medication | Pre-LMP | 1st Trimester | Pre-LMP | 1st Trimester |

|

| ||||

| Cholestyramine | 395 | 250 | 275 | 159 |

| Colchicine | 140 | 68 | 89 | 60 |

| Cyclophosphamide | <11 | <11 | <11 | <11 |

| Danazol | 17 | <11 | 14 | <10 |

| Isotretinoin | 157 | 28 | 50 | 15 |

| Mercaptopurine | 293 | 236 | 102 | 77 |

| Methimazole | 827 | 653 | 1,121 | 962 |

| Methotrexate | 487 | 115 | 366 | 160 |

| Misoprostol | 10,138 | 501 | 3,283 | 236 |

| Propylthiouracil | 623 | 1,470 | 280 | 1,217 |

| Streptomycin sulfate | <11 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tetracycline | 932 | 264 | 420 | 135 |

| Warfarin | 583 | 311 | 775 | 453 |

Counts > 0 or < 11 suppressed. Know/Suspected teratogens with zero exposed: busulfan, chlorambucil, dactinomycin, doxorubicin, thalidomide, vinblastine, and vincristine

LMP: last menstrual period

Antiemetics

Dispensing of any antiemetic at any time during pregnancy was stable around 24.0% in MarketScan (2011–2020) and 30.0% in MAX/TAF (2011–2017) [Figure 1]. Ondansetron was the most common antiemetic with peak utilizations in 2014 (22.0% in MarketScan and 26.5% in MAX/TAF). Doxylamine/Pyridoxine dispensing increased from <0.1% in 2011 to 5.7% in MarketScan and 2.5% in MAX/TAF by the end of the study period.

Figure 1.

Utilization of antiemetics at any time during pregnancy by LMP year in MarketScan (2011–2020) and MAX/TAF (2011–2017).

LMP: last menstrual period

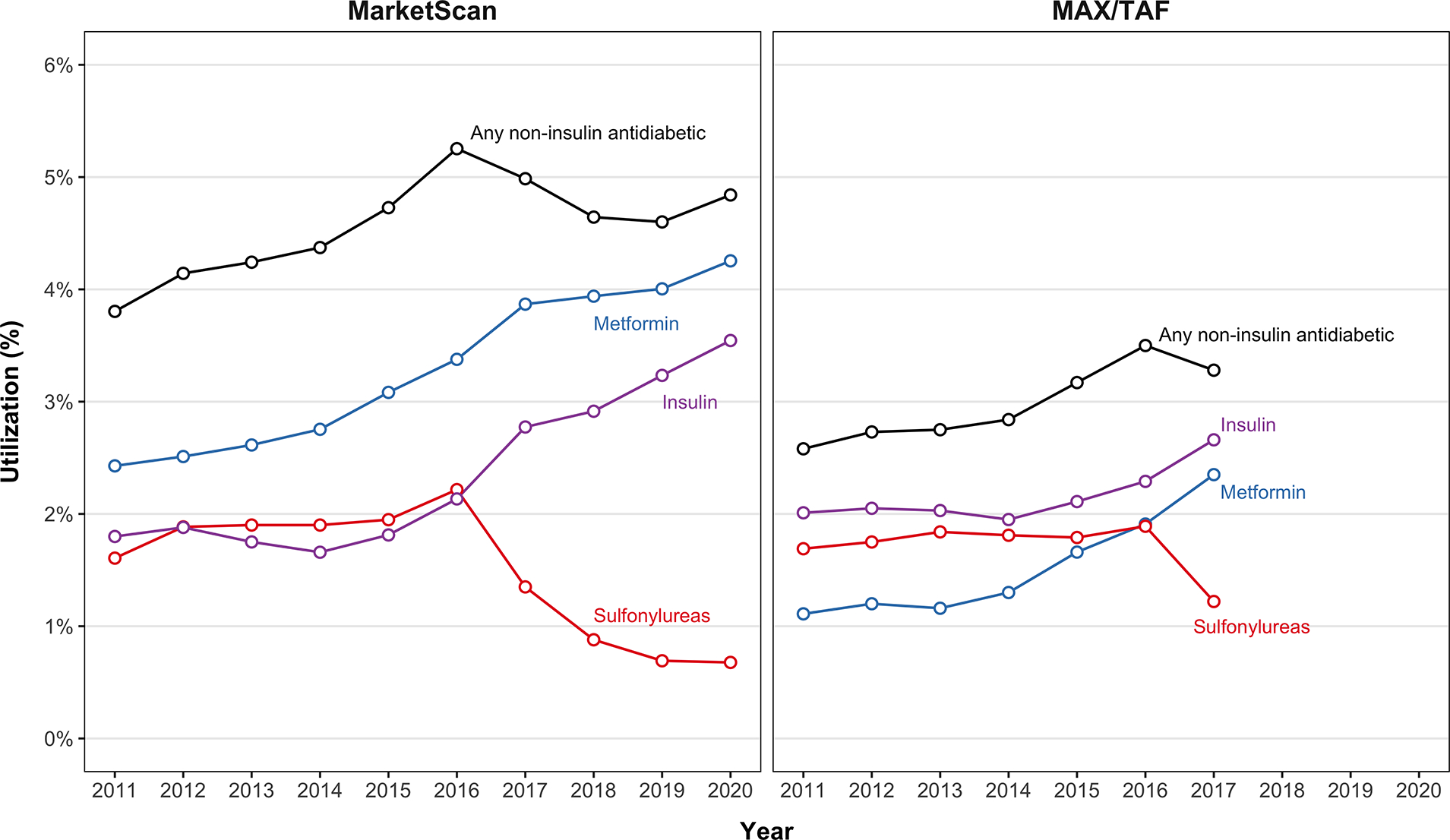

Antidiabetics

Dispensing of any non-insulin antidiabetic increased from 3.8% to 4.8% in MarketScan (2011–2020) and from 2.6% to 3.3% in MAX/TAF (2011–2017) [Figure 2]. This was driven by an increase in metformin utilization (2.4% to 4.3% in MarketScan and 1.1% to 2.4% in MAX/TAF). There was a similar upward trend in insulin dispensing. Sulfonylureas dispensing decreased from a peak of 2.2% in 2016 to 0.7% in 2020 and 1.2% in 2017 in MarketScan and MAX/TAF, respectively.

Figure 2.

Utilization of antidiabetics at any time during pregnancy by LMP year in MarketScan (2011–2020) and MAX/TAF (2011–2017).

LMP: last menstrual period

Antidiabetics with <100 exposures were not included: thiazolidinediones, alpha-glucosidase inhibitors (AGIs), sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP4) inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists, meglitinides, and pramlintide acetate.

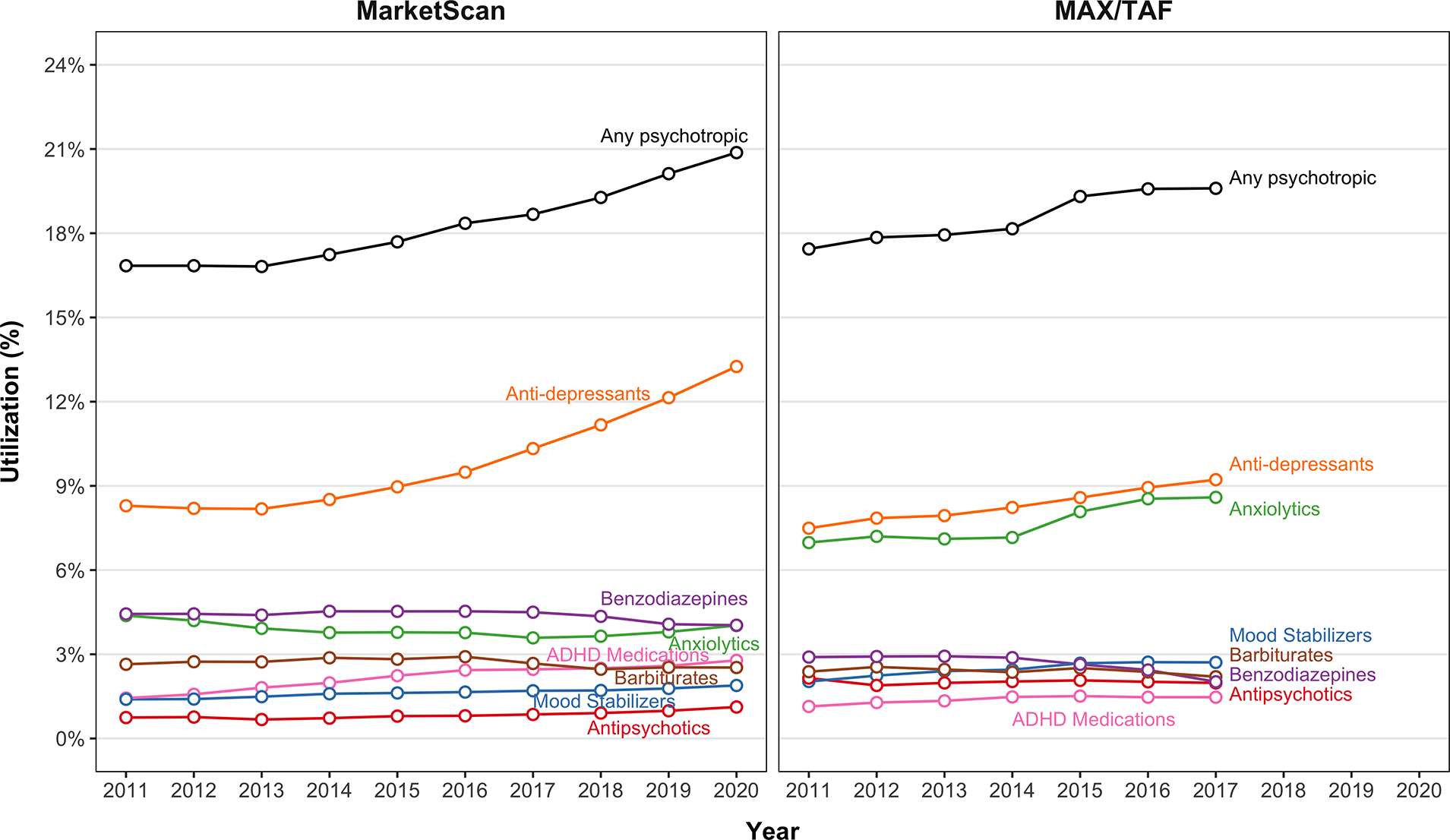

Psychotropics

Dispensing of any psychotropic increased from 16.8% to 20.9% in MarketScan (2011–2020) and from 17.4% to 19.6% in MAX (2011–2017) [Figure 3]. This was driven by an increase in antidepressants utilization. Dispensing of ADHD medications increased in MarketScan and anxiolytics increased in MAX/TAF.

Figure 3.

Utilization of psychotropics at any time during pregnancy by LMP year in MarketScan (2011–2020) and MAX/TAF (2011–2017).

LMP: last menstrual period

ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

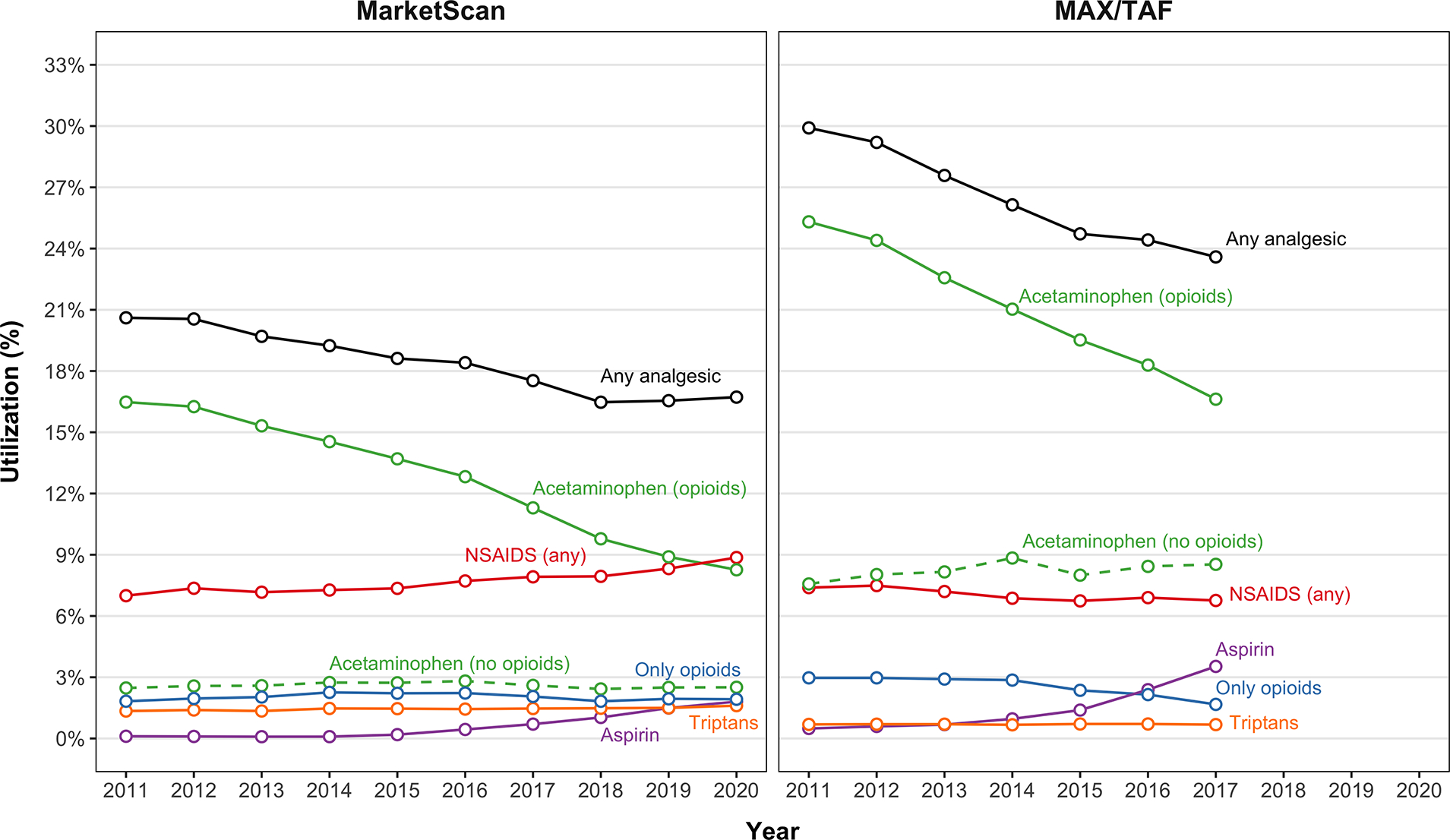

Analgesics and Triptans

Dispensing of any analgesic decreased from 20.6% to 16.7% in MarketScan (2011–2020) and from 29.9% to 23.6% in MAX (2011–2017) [Figure 4]. This was driven by a decrease in dispensing of acetaminophen and opioid combinations (mainly combinations with hydrocodone or codeine). Over the same periods, dispensing trends for acetaminophen without opioids were generally stable for both cohorts and dispensing of opioid only medications were stable in MarketScan while they decreased in MAX. There was an increase in aspirin dispensing in both cohorts starting in 2015. Triptan dispensing did not vary over the study period.

Figure 4.

Utilization of analgesics and antimigraine medications at any time during pregnancy by LMP year in MarketScan (2011–2020) and MAX/TAF (2011–2017).

LMP: last menstrual period

NSAIDs: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

* Opioids exclude antitussives/expectorants.

Levothyroxine

Levothyroxine dispensing increased from 5.5% to 7.6% in MarketScan (2011–2020) and from 1.9% to 2.5% in MAX (2011–2017) [Figure S1].

Comment

Principal findings

This study examined medication use patterns during pregnancy in the U.S. using population-based pharmacy dispensation data from commercially and publicly insured individuals complemented with a nationally representative survey with primary data collection. Antibiotics, analgesics, and antiemetics remain the most commonly dispensed medications at any time during pregnancy. Antidiabetic and psychotropic medications dispensation has increased, and opioid dispensation decreased over the study period. Approximately one-quarter of medications dispensed any time during pregnancy did not have sufficient evidence to assess their safety. Most of these medications were anti-infectives, including antibiotics (metronidazole, doxycycline, cephalexin), antivirals (valacyclovir), and antifungals (fluconazole, terconazole), in addition to montelukast and bupropion. Future studies should focus on evaluating the safety profiles of these medications to inform prescribing.

Results context and implications

Previous studies had shown a steady increase of ondansetron use in pregnancy from close to 0% in 2000 to over 20% in 2014.1,15 However, in our study, ondansetron dispensing decreased by a third from 2014 to 2015, coinciding with litigation and safety concerns regarding use during pregnancy.16 The litigation likely prompted a shift in prescribing practices and patient preferences, leading to increased utilization of alternative antiemetics such as doxylamine/pyridoxine and promethazine. While ondansetron dispensing started to gradually increase again in 2016, utilization was still well below its peak in 2014.

There was a significant increase in antidiabetic medications utilization during the study period. This parallels the notable increase in gestational diabetes in recent years, attributed to increasing maternal age and rising obesity prevalence.17 Specifically, there was a two-fold increase in metformin dispensing, which, among the publicly insured, surpassed the dispensing of sulfonylureas in 2016. Emerging evidence suggesting that sulfonylureas may be associated with suboptimal glucose control compared to insulin as well as increased incidence of maternal hypoglycemia among pregnant individuals with gestational diabetes may have contributed to this apparent trend.18 A 2014 meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials comparing glyburide, metformin, and insulin for the treatment of gestational diabetes concluded that glyburide was inferior compared to the alternatives.19 Changes in guidelines and prescribing preferences have resulted in sharp decreases in sulfonylureas dispensing after 2016. Insulin utilization also substantially increased during the study period, possibly as a result of the decline in sulfonylureas use.

We observed substantial increases in psychotropics dispensing, mainly anti-depressants, anxiolytics, and ADHD medications, that reflect a continuing trend from the previous decade.20,21 Prevalence of mental health conditions has increased prior to and during pregnancy driven by multiple factors including improved awareness, changes in diagnostic criteria, increased screening, and shifting societal attitudes towards mental health.22,23 This may have contributed to higher diagnostic rates, which in turn leads to increased treatment. While the data analyzed in this study is pre-COVID, further increases in psychotropic utilization are possible given the societal effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.24

Opioid utilization decreased by half during the study period both among the commercially and publicly insured, consistent with previously reported trends.25 Notably, dispensing of acetaminophen in combination with an opioid declined substantially, driving the overall decreasing trend. The dispensing of only opioids was relatively low among both groups. When compared with external data from other countries, use was still higher among these U.S.-based cohorts.26 Despite limited evidence on long-term effects, such as child neurodevelopment, opioid use during pregnancy has been associated with several short-term, harmful outcomes.27 While declining trends are promising, additional efforts are needed to bring awareness to the potential risks and help support use of alternatives.28

Levothyroxine use increased during the study period, more among those commercially insured than publicly insured. Several factors may explain the increasing trend. There has been an uptake in the treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism in infertility patients as a result of the increase of in vitro fertilization (IVF)/infertility treatments in the current, older maternal population in the U.S. Additionally, awareness and recognition of the importance of thyroid function during pregnancy has grown in tandem with increasing evidence supporting the benefits of levothyroxine treatment during pregnancy.29 This evidence has influenced clinical guidelines and recommendations, resulting in more diagnosis and treatment of thyroid disorders during pregnancy.30 Levothyroxine has also been used for unapproved indications, including weight loss and improved energy.31 These uses could have contributed to the increased use of levothyroxine. Although there is limited evidence available on the risk of adverse maternal and fetal events associated with levothyroxine use during pregnancy, the teratogenic risk is considered to be “unlikely” given that it is a thyroid hormone.

Since pregnant patients are rarely enrolled in clinical trials, safety information is therefore generally limited. There is an urgent need to include pregnant patients in future clinical drug studies. Additionally, information on safety of use during pregnancy relies on post-approval observational studies based on real-world health care data, which can help in addressing the need for more drug research in pregnant patients.32 While the lack of evidence is not evidence for safety, it is not evidence for risk either. In many instances the benefits outweigh the risks when these medications are used clinically; and some of the medications with no proven safety may be necessary to treat patients, including treating infections and controlling psychiatric conditions.

Strengths and limitations

Our study provides a decade-long update of medication utilization during pregnancy based on a large sample of commercially and publicly insured pregnancies that are representative of the U.S. pregnant population. While uninsured individuals were not included, uninsured pregnancies constitute a small proportion of all pregnancies in the US.33 We used a validated algorithm to identify LMP with 96% accuracy to determine gestational time for individuals with livebirths.34 Nonetheless, our study has limitations. First, data from NHANES included few pregnant individuals each cycle, preventing us from presenting trends over time, or stratifying by demographic characteristics. Oversampling pregnant individuals stopped in 2007 when NHANES instated changes to the sampling design. While the two healthcare database cohorts provide an estimate for the cumulative incidence of dispensation throughout pregnancy, NHANES reports the prevalence of use during a month, which is a function of incidence of prescriptions and duration of treatment. Therefore, estimates are not directly comparable as sustained treatments are more likely to be captured in NHANES during the one-month window, while transient treatments are more likely to appear when examining many months within a given cohort. Second, our analyses in MAX/TAF and MarketScan rely on dispensing data, which lack information on actual medication intake/adherence and do not capture over-the-counter medications. Additionally, it is worth noting that many individuals, and their prescribing physician, might not have been aware of their pregnancy status, especially in the first trimester, resulting in medications being dispensed but not taken. Nonetheless, dispensing data still provide valuable insights in population-wide studies where other approaches are not feasible. Third, to describe use throughout pregnancy, our cohort did not include pregnancies ending in spontaneous or therapeutic abortion, limiting the generalizability of our findings during pre-LMP and first trimester to the entire population of pregnant individuals as medications associated with abortions are likely underrepresented in the current findings (e.g., terminations after accidental exposure to known teratogens, treatments for indications associated with spontaneous abortions). The inclusion of non-livebirths could lead to some misclassification of exposures by trimester as the gestational age for spontaneous abortions and stillbirth is not as accurate as for livebirths. Additionally, the inclusion of stillbirths would increase the complexity of the analysis (pregnancies with a stillbirth would impact the denominator as they might contribute between 20 to 44 weeks) and the interpretability of the results with minimal impact on the general utilization results given that stillbirths represent about 0.6% of pregnancies.35 As such, the findings could be considered as an underestimate of exposure to teratogens, medications used to induce abortion, and treatments for indications associated with a higher risk of abortions (e.g., infertility) due to terminations/spontaneous abortions not being included. Finally, the results among livebirths would be comparable with the literature since most publications about medication use during pregnancy restricted to livebirths. Finally, utilization of over-the-counter medications, supplements, topicals, IVs, and illicit drugs was outside the scope of this study as it requires alternative study designs and data sources.

Conclusions

This analysis updates the literature on the patterns of prescription medication use during pregnancy over the past decade. Dispensing of certain medications decreased, such as opioids and teratogenic medications while dispensing of other medications increased, such as treatments indicated for diabetes and mental health conditions. Evidence on the safety of around one-quarter of the most common medications remains limited. Specifically, future research efforts should focus on the identified anti-infectives as they are medications with high utilization but with limited level of evidence on safety for use during pregnancy.

Supplementary Material

Tweetable Statement.

One-quarter of the medications used during pregnancy in the US do not have sufficient pregnancy safety information.

AJOG at a Glance.

Why was this study conducted?

To identify gaps in safety evidence among the most commonly prescribed medications, this study examined medication utilization patterns during pregnancy in the U.S. using both i) pharmacy claims data from publicly and commercially insured individuals and ii) a nationally representative survey.

What are the key findings?

Anti-infectives, analgesics, anti-emetics, psychotropics, anti-diabetics, anti-asthmatics, and levothyroxine are the most commonly prescribed medications during pregnancy. Approximately one-quarter of medications dispensed during pregnancy do not have sufficient safety evidence.

What does this study add to what is already known?

Additional research is needed on the safety of specific anti-infectives (antibiotics, antifungals, and antivirals) during pregnancy.

Funding Information

This work was supported by grant R01 HD097778 from the National Institute of Child Health and Development (NICHD). LS was supported by a Training Grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, T32HD040128, which had no role in any aspect of the study or submission.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

KJG reports consulting for BillionToOne, Aetion, and Roche outside the scope of the submitted work. KFH reports being an investigator on grants to her institution from Takeda and UCB for unrelated work. SHD was an investigator for research grants from Takeda to her institution for unrelated products. The remaining authors report no conflict of interest.

Partial results were presented at the 39th Annual Meeting, International Conference on Pharmacoepidemiology & Therapeutic Risk Management (ICPE), Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, August 23–27, 2023

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mitchell AA, Gilboa SM, Werler MM, et al. Medication use during pregnancy, with particular focus on prescription drugs: 1976–2008. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(1):51.e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.02.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haas DM, Marsh DJ, Dang DT, et al. Prescription and Other Medication Use in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(5):789–798. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palmsten K, Hernández-Díaz S, Chambers CD, et al. The Most Commonly Dispensed Prescription Medications Among Pregnant Women Enrolled in the U.S. Medicaid Program. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(3):465–473. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thorpe PG, Gilboa SM, Hernandez-Diaz S, et al. Medications in the first trimester of pregnancy: most common exposures and critical gaps in understanding fetal risk. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22(9):1013–1018. doi: 10.1002/pds.3495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tinker SC, Broussard CS, Frey MT, Gilboa SM. Prevalence of prescription medication use among non-pregnant women of childbearing age and pregnant women in the United States: NHANES, 1999–2006. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19(5):1097–1106. doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1611-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Werler MM, Kerr SM, Ailes EC, et al. Patterns of Prescription Medication Use during the First Trimester of Pregnancy in the United States, 1997–2018. Clin Pharmacol Ther. n/a(n/a). doi: 10.1002/cpt.2981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krastein J, Sahin L, Yao L. A review of pregnancy and lactation postmarketing studies required by the FDA. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2023;32(3):287–297. doi: 10.1002/pds.5572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Admon LK, Winkelman TNA, Moniz MH, Davis MM, Heisler M, Dalton VK. Disparities in Chronic Conditions Among Women Hospitalized for Delivery in the United States, 2005–2014. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(6):1319–1326. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacDonald SC, Cohen JM, Panchaud A, McElrath TF, Huybrechts KF, Hernández-Díaz S. Identifying pregnancies in insurance claims data: Methods and application to retinoid teratogenic surveillance. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2019;28(9):1211–1221. doi: 10.1002/pds.4794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ailes EC, Zhu W, Clark EA, et al. Identification of pregnancies and their outcomes in healthcare claims data, 2008–2019: An algorithm. PloS One. 2023;18(4):e0284893. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0284893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiu YH, Huybrechts KF, Zhu Y, Straub L, Bateman BT, Logan R, Hernández-Díaz S. Internal validation of gestational age estimation algorithms in healthcare databases using pregnancies conceived with fertility procedures. Am J Epidemiol. 2023;In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Margulis AV, Setoguchi S, Mittleman MA, Glynn RJ, Dormuth CR, Hernández-Díaz S. Algorithms to estimate the beginning of pregnancy in administrative databases. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22(1):16–24. doi: 10.1002/pds.3284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adam MP, Polifka JE, Friedman JM. Evolving knowledge of the teratogenicity of medications in human pregnancy. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2011;157C(3):175–182. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data. Published online 2020 2011. Accessed July 18, 2022. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/continuousnhanes/default.aspx?Cycle=2017-2020

- 15.Taylor LG, Bird ST, Sahin L, et al. Antiemetic use among pregnant women in the United States: the escalating use of ondansetron. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26(5):592–596. doi: 10.1002/pds.4185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.In re Zofran (Ondansetron) Prods. Liab. Litig., 541 F. Supp. 3d 164 | Casetext Search + Citator. Accessed June 29, 2023. https://casetext.com/case/in-re-zofran-ondansetron-prods-liab-litig-8 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deputy NP, Kim SY, Conrey EJ, Bullard KM. Prevalence and Changes in Preexisting Diabetes and Gestational Diabetes Among Women Who Had a Live Birth - United States, 2012–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(43):1201–1207. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6743a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Diabetes Association. 14. Management of Diabetes in Pregnancy. In: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2020. Vol 43 (Supplement_1). ; 2020:S183–S19. Accessed June 29, 2023. https://diabetesjournals.org/care/article/43/Supplement_1/S183/30619/14-Management-of-Diabetes-in-Pregnancy-Standards [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balsells M, García-Patterson A, Solà I, Roqué M, Gich I, Corcoy R. Glibenclamide, metformin, and insulin for the treatment of gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2015;350:h102. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toh S, Li Q, Cheetham TC, et al. Prevalence and trends in the use of antipsychotic medications during pregnancy in the U.S., 2001–2007: a population-based study of 585,615 deliveries. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2013;16(2):149–157. doi: 10.1007/s00737-013-0330-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huybrechts KF, Palmsten K, Mogun H, et al. National trends in antidepressant medication treatment among publicly insured pregnant women. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35(3):265–271. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siu AL, US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), Bibbins-Domingo K, et al. Screening for Depression in Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2016;315(4):380–387. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howard LM, Khalifeh H. Perinatal mental health: a review of progress and challenges. World Psychiatry Off J World Psychiatr Assoc WPA. 2020;19(3):313–327. doi: 10.1002/wps.20769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kotlar B, Gerson EM, Petrillo S, Langer A, Tiemeier H. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal health: a scoping review. Reprod Health. 2021;18(1):10. doi: 10.1186/s12978-021-01070-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bateman BT, Hernandez-Diaz S, Rathmell JP, et al. Patterns of opioid utilization in pregnancy in a large cohort of commercial insurance beneficiaries in the United States. Anesthesiology. 2014;120(5):1216–1224. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyer A, LeClair C, McDonald JV. Prescription Opioid Prescribing in Western Europe and the United States. R I Med J 2013. 2020;103(2):45–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tobon AL, Habecker E, Forray A. Opioid Use in Pregnancy. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21(12):118. doi: 10.1007/s11920-019-1110-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yazdy MM, Desai RJ, Brogly SB. Prescription Opioids in Pregnancy and Birth Outcomes: A Review of the Literature. J Pediatr Genet. 2015;4(2):56–70. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1556740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Delitala AP, Capobianco G, Cherchi PL, Dessole S, Delitala G. Thyroid function and thyroid disorders during pregnancy: a review and care pathway. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2019;299(2):327–338. doi: 10.1007/s00404-018-5018-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Korevaar TIM, Medici M, Visser TJ, Peeters RP. Thyroid disease in pregnancy: new insights in diagnosis and clinical management. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2017;13(10):610–622. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2017.93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bernet VJ. Thyroid hormone misuse and abuse. Endocrine. 2019;66(1):79–86. doi: 10.1007/s12020-019-02045-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huybrechts KF, Bateman BT, Hernández-Díaz S. Use of real-world evidence from healthcare utilization data to evaluate drug safety during pregnancy. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2019;28(7):906–922. doi: 10.1002/pds.4789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frost JJ, Zolna MR, Frohwirth LF, et al. Publicly Supported Family Planning Services in the United States: Likely Need, Availability and Impact, 2016. Published online October 21, 2019. doi: 10.1363/2019.30830 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhu Y, Thai TN, Hernandez-Diaz S, et al. Development and Validation of Algorithms to Estimate Live Birth Gestational Age in Medicaid Analytic eXtract Data. Epidemiol Camb Mass. 2023;34(1):69–79. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000001559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities. What is Stillbirth? Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Stillbirth. Published September 29, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/stillbirth/facts.html

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.