Abstract

The present study belonged to an unfunded project, dealing on the systematic description of unprecedented essential oils (EOs), distilled from 12 species of genus Gynoxys Cuatrec. In this very case, the aim was the first chemical and enantiomeric analyses of two volatile fractions, obtained from the leaves of Gynoxys cuicochensis Cuatrec. and Gynoxys sancti-antonii Cuatrec. These EOs were analyzed by GC–MS (qualitatively) and GC–FID (quantitatively), detecting 89 and 60 components from G. cuicochensis and G. sancti-antonii, respectively. Major components for G. cuicochensis EO, on a nonpolar and polar stationary phase, were α-pinene (29.4–29.6%), p-vinylguaiacol (3.3–3.6%), and germacrene D (20.8–19.9%). In G. sancti-antonii EO, the main compounds were α-pinene (3.0–2.9%), β-pinene (12.9–12.1%), γ-curcumene (19.7–18.3%), germacrene D (9.0% on the polar phase), ar-curcumene (5.3% on the polar phase), δ-cadinene (4.1–4.6%), α-muurolol (3.3–2.4%), α-cadinol (3.0% on both columns), and an undetermined compound, of molecular weight 220. In addition to chemical composition, the enantioselective analysis of the main chiral compounds was carried out on two different chiral selectors. In G. cuicochensis EO, (1R,5R)-(+)-α-pinene, (S)-(+)-β-phellandrene, (R)-(−)-piperitone, and (S)-(−)-germacrene D were enantiomerically pure, whereas β-pinene, sabinene, α-phellandrene, limonene, linalool, and terpinen-4-ol were observed as scalemic mixtures. On the other hand, in G. sancti-antonii EO, the pure enantiomers were (1S,5S)-(−)-α-pinene, (1R,5R)-(+)-sabinene, (R)-(−)-β-phellandrene, (S)-(−)-limonene, (1S,2R,6R,7R,8R)-(+)-α-copaene, (R)-(−)-terpinen-4-ol, and (S)-(−)-germacrene D, whereas β-pinene, linalool, and α-terpineol were present as scalemic mixtures. The principal component analysis demonstrated that G. cuicochensis volatile fraction was quite similar to many of the other EOs of the same genus, whereas G. sancti-antonii produced the most dissimilar EO. Furthermore, the enantioselective analyses showed the usual variable enantiomeric distribution, with a greater presence of enantiomerically pure compounds in G. sancti-antonii EO.

1. Introduction

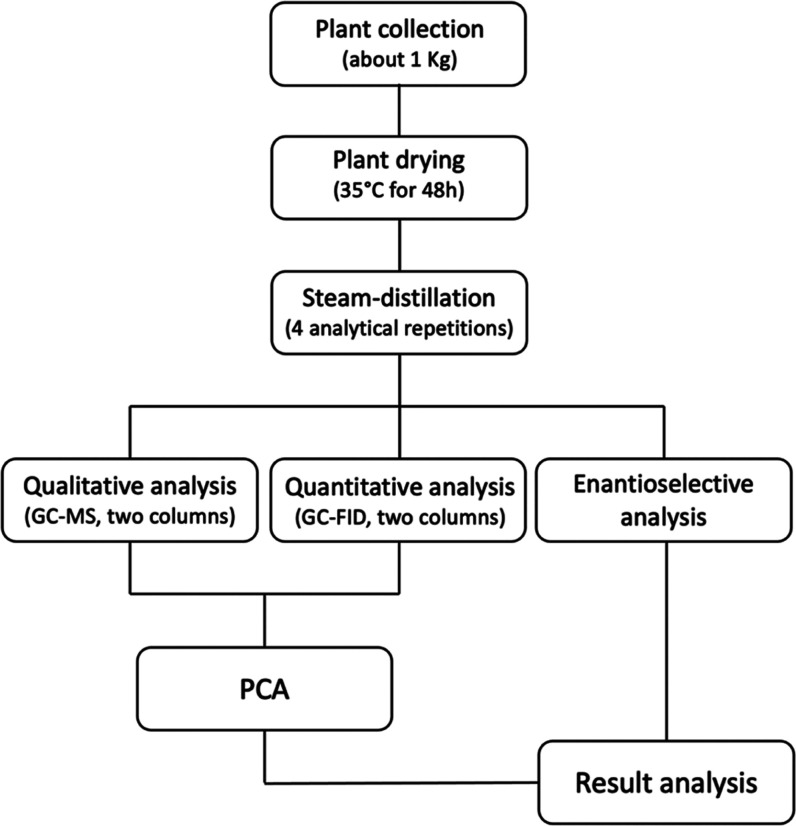

Ecuador is a South American country, crossed by the equatorial line, and characterized by four different climatic regions, whose conditions are almost constantly maintained all year long. Therefore, a great biodiversity evolved in this region, producing an incredible number of so far unprecedented botanical species from a chemical point of view.1,2 This situation led the United Nations to declare Ecuador as one of the 17 “megadiverse” countries in the world.3 For these reasons, our group has been investigating natural products for about 20 years, with the purpose of enhancing and preserving the Ecuadorian flora through the knowledge of its phytochemistry and, possibly, the discovery of pharmacologically interesting metabolites.4,5 During the past few years, we mainly focused on the description of new essential oils (EOs), with emphasis on their chemical and enantiomeric compositions, olfactometric profiles, and biological activities.6−9 Being centered on phytochemistry and chemotaxonomy, high distillation yields, or agricultural availability are not usually leading criteria of plant selection for our research. In this perspective, the present study belonged to un unfunded project, dealing on the systematic description of new EOs from 12 plants of the genus Gynoxys Cuatrec. (Asteraceae) in the province of Loja, Ecuador. So far, the EOs obtained from Gynoxys miniphylla Cuatrec., Gynoxys rugulosa Muschl., Gynoxys buxifolia (Kunth) Cass., and Gynoxys laurifolia (Kunth) Cass. have already been studied and published.10−13 The composition of Gynoxys szyszylowiczii Hieron. volatile fraction is ready to be published, whereas Gynoxys calyculisolvens Hieron., Gynoxys pulchella (Kunth) Cass., Gynoxys reinaldii Cuatrec., Gynoxys hallii Hieron., and Gynoxys azuayensis Cuatrec. are currently under investigation. Finally, Gynoxys cuicochensis Cuatrec. and Gynoxys sancti-antonii Cuatrec. are the object of this report. According to botanical literature, the genus Gynoxys is an Andean endemism, comprising about 120 species diffused from Argentina and Bolivia to Venezuela.14 The diffusion center is Ecuador, where most of these species are endemic or native.15 In this country, G. cuicochensis is an endemic shrub or tree, growing between 2000 and 3500 m above the sea level, in the provinces of Azuay, Cañar, Loja, and Pichincha.16 On the other hand, G. sancti-antonii is a native treelet, growing between 2500 and 3500 m above the sea level in the provinces of Azuay, Cañar, Chimborazo, Loja, and Pichincha.16 No synonyms were reported for G. cuicochensis, whereas G. sancti-antonii var. latifolia Cuatrec. is a synonym of G. sancti-antonii.16 On the one hand, from the chemical point of view, G. cuicochensis is a completely unprecedented species. On the other hand, G. sancti-antonii has been previously studied about its nonvolatile metabolites.17,18 The aim of the present research is the chemical and enantiomeric description of two EOs obtained from G. cuicochensis and G. sancti-antonii leaves that, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, are reported here for the first time. The experimental design is represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Experimental design of the present investigation.

2. Results and Discussion

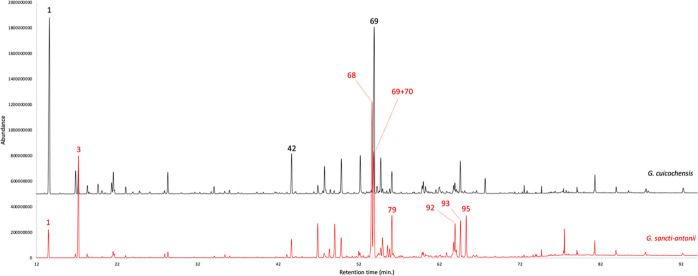

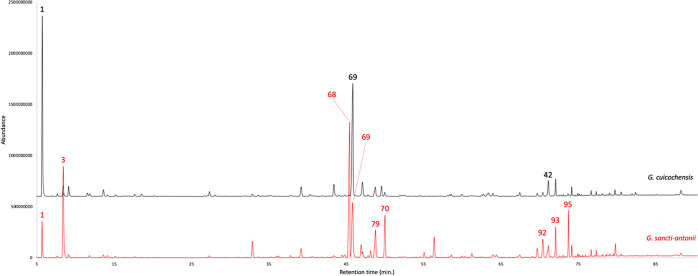

2.1. Chemical Analysis

The dry leaves of G. cuicochensis produced an EO with an analytical yield of 0.08 ± 0.003% by weight. A total of eighty-nine compounds were identified and quantified on at least one of two stationary phases of different polarity. The gas chromatographic (GC) profiles of both essential oils on the nonpolar and polar stationary phases are represented in Figures 2 and 3, whereas the complete qualitative and quantitative analyses are detailed in Table 1. Major components (≥3.0% on at least one column), on the nonpolar and polar stationary phase, respectively, were as follows: α-pinene (29.4–29.6%, peak 1), p-vinylguaiacol (3.3–3.6%, peak 42), and germacrene D (20.8–19.9%, peak 69). Unlike most of the other Gynoxys EOs, the volatile fraction of G. cuicochensis was not dominated by sesquiterpenes, being monoterpene and sesquiterpene fractions almost equal. In fact, monoterpenes and oxygenated monoterpenoids accounted together for 41.6–40.9%, whereas sesquiterpenes and oxygenated sesquiterpenoids corresponded to 41.2–38.7% as a sum. About G. sancti-antonii EO, the distillation yield was 0.08 ± 0.014 by weight. In this volatile fraction, 60 components were identified and quantified on at least one column. Main compounds were as follows: α-pinene (3.0–2.9%, peak 1), β-pinene (12.9–12.1%, peak 3), γ-curcumene (19.7–18.3%, peak 68), germacrene D (9.0% on the polar phase, peak 69), ar-curcumene (5.3% on the polar phase, peak 70), δ-cadinene (4.1–4.6%, peak 79), α-muurolol (3.3–2.4%, peak 92), α-cadinol (3.0% on both columns, peak 93), and an undetermined compound of molecular weight 220 (3.1–4.2%, peak 95). The volatile fraction of G. sancti-antonii was dominated by sesquiterpenes and oxygenated sesquiterpenoids, whose joint fractions corresponded to 64.3–59.3% on the nonpolar and polar stationary phase, respectively. On the other hand, the sum of monoterpenes and oxygenated monoterpenoids corresponded to 18.5–17.3% of the whole oil mass. Interestingly, the characteristic heavy aliphatic fraction, that we could observe in other species of this genus, were not so important in G. cuicochensis and G. sancti-antonii. In fact, despite these compounds were clearly present, their quantitative contribution did not exceed 10% of the entire oil composition in both plants.

Figure 2.

GC–MS profile of G. cuicochensis (black) and G. sancti-antonii (red) EOs on a 5%-phenyl-methylpolysiloxane stationary phase. The peak numbers refer to major compounds (≥3.0% on at least one column) in Table 1.

Figure 3.

GC–MS profile of G. cuicochensis (black) and G. sancti-antonii (red) EOs on a polyethylene glycol stationary phase. The peak numbers refer to major compounds (≥3.0% on at least one column) in Table 1.

Table 1. Qualitative (GC–MS) and Quantitative (GC–FID) Chemical Composition of G. cuicochensis and G. sancti-antonii EO on 5%-Phenyl-methylpolysiloxane and Polyethylene Glycol Stationary Phasesc.

| no. | compounds | 5%-phenyl-methylpolysiloxane |

polyethylene glycol |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LRIa | LRIb |

G. cuicochensis |

G. sancti-antonii |

reference | LRIa | LRIb |

G. cuicochensis |

G. sancti-antonii |

reference | ||||||

| % | σ | % | σ | % | σ | % | σ | ||||||||

| 1 | α-pinene | 933 | 932 | 29.4 | 4.84 | 3.0 | 0.51 | (19) | 1016 | 1016 | 29.6 | 4.26 | 2.9 | 0.24 | (20) |

| 2 | sabinene | 974 | 969 | 1.9 | 0.43 | 0.4 | 0.07 | (19) | 1103 | 1100 | 1.9 | 0.27 | 0.4 | 0.04 | (21) |

| 3 | β-pinene | 979 | 974 | 2.1 | 0.32 | 12.9 | 1.86 | (19) | 1115 | 1116 | 2.0 | 0.29 | 12.1 | 1.21 | (22) |

| 4 | myrcene | 992 | 988 | 0.7 | 0.08 | 0.2 | 0.02 | (19) | 1161 | 1161 | 0.7 | 0.08 | 0.2 | 0.16 | (23) |

| 5 | pentyl furan | 995 | 984 | 0.2 | 0.07 | (19) | 1231 | 1230 | 0.2 | 0.06 | (24) | ||||

| 6 | n-decane | 1000 | 1000 | trace | 1000 | 1000 | 0.2 | 0.02 | |||||||

| 7 | α-phellandrene | 1009 | 1002 | 0.9 | 0.10 | (19) | 1155 | 1153 | 0.7 | 0.08 | (25) | ||||

| 8 | (2E,4E)-heptadienal | 1014 | 1007 | 0.1 | 0.02 | (19) | 1460 | 1461 | 0.2 | 0.02 | (26) | ||||

| 9 | α-terpinene | 1020 | 1014 | 0.4 | 0.03 | (19) | 1171 | 1173 | 0.1 | 0.02 | (27) | ||||

| 10 | p-cymene | 1029 | 1020 | 0.5 | 0.08 | trace | (19) | 1263 | 1264 | 0.6 | 0.07 | 0.1 | 0.01 | (28) | |

| 11 | limonene | 1032 | 1024 | 1.5 | 0.18 | 0.6 | 0.08 | (19) | 1190 | 1190 | 1.5 | 0.16 | 0.3 | 0.21 | (29) |

| 12 | β-phellandrene | 1034 | 1025 | 0.2 | 0.04 | 0.4 | 0.06 | (19) | 1199 | 1198 | trace | 0.4 | 0.04 | (30) | |

| 13 | (E)-β-ocimene | 1051 | 1044 | 0.5 | 0.05 | (19) | 1250 | 1251 | 0.6 | 0.05 | (31) | ||||

| 14 | benzene acetaldehyde | 1061 | 1036 | 0.1 | 0.01 | (19) | 1677 | 1669 | trace | (32) | |||||

| 15 | γ-terpinene | 1062 | 1054 | 0.1 | 0.02 | (19) | 1238 | 1238 | 0.1 | 0.02 | (33) | ||||

| 16 | (2E)-octen-1-al | 1074 | 1049 | 0.2 | 0.02 | (19) | 1422 | 1425 | 0.1 | 0.01 | (34) | ||||

| 17 | trans-linalool oxide (furanoid) | 1082 | 1084 | 0.1 | 0.01 | (19) | 1466 | 1466 | trace | (35) | |||||

| 18 | terpinolene | 1088 | 1086 | 0.1 | 0.01 | (19) | 1274 | 1274 | 0.1 | 0.01 | - | (36) | |||

| 19 | linalool | 1110 | 1113 | 0.3 | 0.03 | 0.5 | 0.04 | (37) | 1553 | 1556 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 0.3 | 0.04 | (38) |

| 20 | nonanal | 1116 | 1100 | 1.4 | 0.11 | (19) | 1390 | 1390 | 1.1 | 0.07 | (39) | ||||

| 21 | (2E)-hexenyl propanoate | 1116 | 1111 | trace | (40) | 1390 | 1392 | 0.3 | 0.04 | (40) | |||||

| 22 | α-campholenal | 1138 | 1122 | trace | (19) | 1478 | 1485 | 0.1 | 0.01 | (41) | |||||

| 23 | (3Z)-hexenyl isobutanoate | 1155 | 1142 | 0.1 | 0.01 | (19) | 1384 | 1385 | 0.3 | 0.03 | (42) | ||||

| 24 | (2E)-nonen-1-al | 1175 | 1157 | 0.1 | 0.01 | (19) | 1527 | 1524 | 0.2 | 0.01 | (35) | ||||

| 25 | safranal | 1178 | 1197 | trace | (19) | 1631 | 1622 | 0.2 | 0.01 | (43) | |||||

| 26 | p-mentha-1,5-dien-8-ol | 1186 | 1166 | 0.2 | 0.02 | (19) | 1723 | 1723 | 0.1 | 0.01 | (44) | ||||

| 27 | terpinen-4-ol | 1191 | 1184 | 0.5 | 0.04 | 0.2 | 0.03 | (45) | 1594 | 1594 | 0.7 | 0.04 | 0.2 | 0.03 | (46) |

| 28 | n-dodecane | 1200 | 1200 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 1200 | 1200 | 0.3 | 0.04 | ||||||

| 29 | p-cymen-8-ol | 1202 | 1179 | trace | (19) | 1845 | 1845 | 0.1 | 0.01 | (31) | |||||

| 30 | myrtenol | 1209 | 1194 | 0.1 | 0.01 | (19) | 1784 | 1786 | trace | (47) | |||||

| 31 | α-terpineol | 1209 | 1207 | - | 0.3 | 0.06 | (39) | 1692 | 1692 | 0.2 | 0.04 | (23) | |||

| 32 | decanal | 1217 | 1214 | 0.2 | 0.01 | trace | (48) | 1494 | 1492 | 0.2 | 0.03 | 0.1 | 0.01 | (49) | |

| 33 | β-cyclocitral | 1232 | 1217 | 0.1 | 0.01 | (19) | 1605 | 1606 | 0.1 | 0.01 | (50) | ||||

| 34 | trans-carveol | 1235 | 1215 | 0.1 | 0.01 | (19) | 1830 | 1830 | trace | (35) | |||||

| 35 | geraniol | 1265 | 1249 | trace | (19) | 1849 | 1849 | 0.2 | 0.01 | (51) | |||||

| 36 | piperitone | 1272 | 1249 | 0.1 | 0.01 | (19) | 1710 | 1710 | trace | (52) | |||||

| 37 | 2-(E)-decenal | 1276 | 1260 | 0.1 | 0.01 | (19) | 1635 | 1630 | 0.2 | 0.01 | (39) | ||||

| 38 | nonanoic acid | 1297 | 1267 | 0.1 | 0.01 | (19) | |||||||||

| 39 | n-tridecane | 1300 | 1300 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 1300 | 1300 | 0.1 | 0.01 | ||||||

| 40 | cis-pinocarvyl acetate | 1305 | 1311 | 0.1 | 0.01 | (19) | 1639 | 0.1 | 0.01 | § | |||||

| 41 | undecanal | 1318 | 1319 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 0.2 | 0.04 | (53) | 1580 | 1580 | 0.5 | 0.08 | trace | (54) | |

| 42 | p-vinylguaiacol | 1327 | 1324 | 3.3 | 0.19 | 1.8 | 0.42 | (55) | 2189 | 2193 | 3.6 | 0.11 | 2.4 | 0.47 | (56) |

| 43 | (2E,4E)-decadienal | 1335 | 1315 | 0.3 | 0.01 | (19) | 1799 | 1795 | 0.3 | 0.05 | (57) | ||||

| 44 | α-copaene | 1376 | 1374 | 2.8 | 0.61 | (19) | 1474 | 1477 | 2.6 | 0.23 | (58) | ||||

| 45 | α-ylangene | 1377 | 1373 | 0.1 | 0.01 | (19) | 1474 | 1472 | 0.6 | 0.05 | (25) | ||||

| 46 | 2-epi-α-funebrene | 1388 | 1380 | 0.4 | 0.10 | (19) | 1724 | 1.0 | 0.12 | § | |||||

| 47 | β-cubebene | 1389 | 1387 | 0.3 | 0.07 | (19) | 1523 | 1521 | 0.2 | 0.02 | (59) | ||||

| 48 | (Z)-β-damascenone | 1390 | 1361 | 0.3 | 0.06 | (19) | 1806 | 1791 | 0.1 | 0.02 | (60) | ||||

| 49 | geranyl acetate | 1390 | 1379 | 1.4 | 0.14 | (19) | 1756 | 1756 | 1.4 | 0.14 | (61) | ||||

| 50 | n-tetradecane | 1400 | 1400 | 0.2 | 0.01 | 1400 | 1400 | 0.3 | 0.01 | ||||||

| 51 | α-gurjunene | 1407 | 1409 | 0.2 | 0.02 | (19) | 1510 | 1511 | 0.3 | 0.01 | (62) | ||||

| 52 | undetermined (MW: 192) | 1408 | 2.7 | 0.44 | 1882 | 2.4 | 0.21 | ||||||||

| 53 | (E)-β-damascenone | 1418 | 1416 | 0.4 | 0.03 | (19) | |||||||||

| 54 | (E)-β-caryophyllene | 1421 | 1421 | 2.1 | 0.20 | 1.8 | 0.40 | (19) | 1575 | 1575 | 2.4 | 0.24 | 1.6 | 0.18 | (63) |

| 55 | β-copaene | 1432 | 1430 | 0.1 | 0.01 | (19) | 1570 | 1567 | 0.1 | 0.01 | (64) | ||||

| 56 | β-gurjunene | 1432 | 1431 | 0.3 | 0.06 | (19) | 1671 | 1655 | 0.5 | 0.07 | (41) | ||||

| 57 | cis-α-bergamotene | 1434 | 1433 | trace | (65) | 1528 | 1530 | 0.7 | 0.06 | (66) | |||||

| 58 | (Z)-β-farnesene | 1443 | 1440 | 0.2 | 0.04 | (19) | 1633 | 1632 | 0.2 | 0.03 | (67) | ||||

| 59 | myltayl-4(12)-ene | 1447 | 1445 | 0.1 | 0.01 | (19) | |||||||||

| 60 | trans-muurola-3,5-diene | 1448 | 1451 | trace | (19) | 1611 | 0.1 | 0.02 | § | ||||||

| 61 | (E)-β-farnesene | 1456 | 1454 | 0.6 | 0.13 | (19) | 1665 | 1660 | 0.5 | 0.07 | (68) | ||||

| 62 | α-humulene | 1458 | 1452 | 2.6 | 0.21 | 0.5 | 0.10 | (19) | 1647 | 1649 | 2.6 | 0.23 | 0.2 | 0.03 | (69) |

| 63 | cis-cadina-1,(6),4-diene | 1465 | 1461 | 0.2 | 0.05 | (19) | 1689 | 0.2 | 0.02 | § | |||||

| 64 | cis-muurola-4(14),5-diene | 1466 | 1465 | 0.1 | 0.01 | (19) | 1523 | trace | § | ||||||

| 65 | (E)-β-farnesene | 1472 | 1454 | 0.3 | 0.05 | (19) | 1665 | 1664 | 0.1 | 0.01 | (25) | ||||

| 66 | dauca-5,8-diene | 1475 | 1471 | 0.3 | 0.05 | (19) | 1642 | 1654 | 0.2 | 0.04 | (70) | ||||

| 67 | γ-muurolene | 1480 | 1478 | 0.1 | 0.01 | (19) | 1671 | 1676 | 0.2 | 0.01 | (71) | ||||

| 68 | γ-curcumene | 1482 | 1481 | 0.4 | 0.09 | 19.7 | 4.63 | (19) | 1682 | 1689 | 0.3 | 0.10 | 18.3 | 2.11 | (72) |

| 69 | germacrene D | 1486 | 1495 | 20.8 | 2.48 | 14.9 | 3.32 | (19) | 1689 | 1683 | 19.9 | 2.50 | 9.0 | 0.84 | (73) |

| 70 | ar-curcumene | 1487 | 1479 | (19) | 1763 | 1763 | 5.3 | 0.69 | (74) | ||||||

| 71 | (E)-β-ionone | 1492 | 1487 | 1.2 | 0.15 | (19) | 1922 | 1923 | 1.4 | 0.18 | (22) | ||||

| 72 | trans-muurola-4(14),5-diene | 1497 | 1493 | 0.4 | 0.03 | (19) | 1695 | trace | § | ||||||

| 73 | α-zingiberene | 1500 | 1493 | 2.3 | 0.25 | (19) | 1714 | 1713 | 2.2 | 0.22 | (75) | ||||

| 74 | bicyclogermacrene | 1500 | 1500 | 0.8 | 0.18 | 1712 | 1706 | 1.2 | 0.14 | (76) | |||||

| 75 | α-muurolene | 1503 | 1500 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 3.8 | 1.01 | (19) | 1708 | 1700 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 1.9 | 0.22 | (77) |

| 76 | 3-methyl-phenyl ethyl butanoate | 1504 | 1495 | (78) | 1960 | 1964 | 0.4 | 0.05 | (74) | ||||||

| 77 | β-curcumene | 1513 | 1514 | 1.1 | 0.26 | (19) | 1731 | 1733 | 1.0 | 0.12 | (79) | ||||

| 78 | γ-cadinene | 1518 | 1513 | 0.3 | 0.03 | (19) | 1739 | 1738 | trace | (79) | |||||

| 79 | δ-cadinene | 1523 | 1522 | 1.5 | 0.15 | 4.1 | 0.88 | (19) | 1742 | 1744 | 2.2 | 0.19 | 4.6 | 0.54 | (44) |

| 80 | (E)-nerolidol | 1570 | 1561 | 0.2 | 0.03 | (19) | 2042 | 2045 | 0.1 | 0.02 | (80) | ||||

| 81 | germacrene D-4-ol | 1586 | 1583 | 0.5 | 0.11 | 0.8 | 0.37 | (81) | 2034 | 2035 | 0.7 | 0.09 | 0.5 | 0.07 | (82) |

| 82 | spathulenol | 1589 | 1577 | 0.9 | 0.09 | (19) | 2106 | 2106 | 0.9 | 0.08 | (83) | ||||

| 83 | caryophyllene oxide | 1588 | 1588 | 0.9 | 0.10 | 0.6 | 0.15 | (19) | 1967 | 1968 | 0.5 | 0.05 | 0.5 | 0.08 | (35) |

| 84 | n-hexadecane | 1600 | 1600 | 0.1 | 0.03 | 0.2 | 0.04 | 1600 | 1600 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 0.2 | 0.03 | ||

| 85 | salvial-4(14)-en-1-one | 1604 | 1594 | 0.2 | 0.06 | (19) | 1979 | 1995 | 0.1 | 0.01 | (36) | ||||

| 86 | ledol | 1616 | 1616 | 0.7 | 0.07 | 0.1 | 0.02 | (84) | 2005 | 2014 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 0.1 | 0.03 | (85) |

| 87 | humulene epoxide II | 1623 | 1608 | 0.7 | 0.05 | (19) | 2009 | 2011 | 0.2 | 0.02 | (44) | ||||

| 88 | 1-epi-cubenol | 1639 | 1638 | 0.1 | 0.01 | (26) | 2044 | 2035 | 0.4 | 0.02 | (86) | ||||

| 89 | cis-cadin-4-en-7-ol | 1639 | 1635 | 0.2 | 0.04 | (87) | 2044 | 0.3 | 0.03 | § | |||||

| 90 | epi-α-cadinol | 1655 | 1652 | 0.8 | 0.09 | 1.0 | 0.48 | (19) | 2157 | 2154 | 0.7 | 0.07 | 0.1 | 0.01 | (88) |

| 91 | epi-α-muurolol | 1658 | 1640 | 0.8 | 0.10 | (19) | 2173 | 2176 | 0.9 | 0.11 | (25) | ||||

| 92 | α-muurolol | 1660 | 1652 | 0.4 | 0.06 | 3.3 | 0.46 | (89) | 2187 | 2187 | trace | 2.4 | 0.44 | (28) | |

| 93 | α-cadinol | 1670 | 1670 | 2.4 | 0.34 | 3.0 | 0.41 | (90) | 2211 | 2212 | 2.5 | 0.31 | 3.0 | 0.29 | (76) |

| 94 | ar-turmerone | 1679 | 1668 | 0.4 | 0.04 | (19) | 2226 | 0.1 | 0.01 | § | |||||

| 95 | undetermined (FW:220) | 1682 | 3.1 | 0.47 | 2248 | 4.2 | 0.52 | ||||||||

| 96 | n-heptadecane | 1700 | 1700 | 0.2 | 0.03 | 1700 | 1700 | 0.2 | 0.01 | ||||||

| 97 | amorpha-4,9-dien-2-ol | 1706 | 1700 | 0.3 | 0.04 | 0.1 | 0.01 | (19) | 2275 | 0.3 | 0.03 | 0.4 | 0.29 | § | |

| 98 | pentadecanal | 1727 | 1724 | 0.9 | 0.08 | (19) | 2022 | 2024 | 1.3 | 0.09 | (91) | ||||

| 99 | (2Z,6E)-farnesol | 1730 | 1722 | trace | (19) | 2280 | 2291 | 0.2 | 0.21 | (92) | |||||

| 100 | n-octadecane | 1800 | 1800 | 0.1 | 0.02 | 1800 | 1800 | 0.9 | 0.13 | ||||||

| 101 | hexadecanal | 1833 | 1828 | 0.1 | 0.01 | (19) | 2129 | 2132 | 0.2 | 0.02 | (91) | ||||

| 102 | (2E,6E)-farnesyl acetate | 1843 | 1845 | trace | 0.1 | 0.07 | (19) | 2233 | 2234 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 0.4 | 0.17 | (93) | |

| 103 | 6,10,14-trimethyl-2-pentadecanone | 1856 | 1846 | 0.1 | 0.01 | (19) | 2122 | 2125 | 0.1 | 0.02 | (80) | ||||

| 104 | heptadecanal | 1932 | 1932 | 0.2 | 0.04 | 0.2 | 0.02 | (88) | 2238 | 2247 | 0.5 | 0.05 | 0.5 | 0.03 | (88) |

| 105 | 1-eicosene | 1995 | 1993 | 0.7 | 0.07 | (19) | 2047 | 2047 | 1.0 | 0.08 | (94) | ||||

| 106 | n-heneicosane | 2100 | 2100 | 0.1 | 0.02 | 0.1 | 0.02 | 2100 | 2100 | 0.1 | 0.02 | 0.8 | 0.39 | ||

| 107 | 1-octadecanol acetate | 2194 | 2205 | 0.2 | 0.02 | (95) | 2529 | 2521 | 0.1 | 0.03 | (96) | ||||

| 108 | n-docosane | 2200 | 2200 | trace | trace | 2200 | 2200 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 0.3 | 0.14 | ||||

| 109 | 1- tricosene | 2295 | 2292 | 2.1 | 0.26 | (19) | 2356 | 2.0 | 0.13 | § | |||||

| 110 | n-tricosane | 2300 | 2300 | 0.7 | 0.12 | 0.5 | 0.09 | 2300 | 2300 | 0.1 | 0.02 | 0.4 | 0.27 | ||

| 111 | 1-tetracosene | 2400 | 2402 | 1.5 | 0.33 | (97) | 2452 | 2.0 | 0.17 | § | |||||

| 112 | n-tetracosane | 2400 | 2400 | trace | 0.3 | 0.06 | 2400 | 2400 | 0.3 | 0.06 | 0.2 | 0.10 | |||

| 113 | docosanal | 2440 | 2434 | 0.1 | 0.03 | (19) | 2682 | 0.3 | 0.05 | § | |||||

| 114 | n-pentacosane | 2500 | 2500 | 0.2 | 0.05 | 0.2 | 0.03 | 2500 | 2500 | 0.1 | 0.02 | 0.1 | 0.05 | ||

| 115 | 1-pentacosene | 2506 | 2496 | 0.1 | 0.01 | (98) | 2478 | 2488 | 0.1 | 0.03 | (58) | ||||

| 116 | n-hexacosane | 2600 | 2600 | 0.3 | 0.07 | 2600 | 2600 | 0.3 | 0.06 | ||||||

| monoterpene hydrocarbons | 38.4 | 17.5 | 37.9 | 16.5 | |||||||||||

| oxygenated monoterpenes | 3.2 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 0.8 | |||||||||||

| sesquiterpene hydrocarbons | 31.7 | 52.1 | 31.0 | 49.6 | |||||||||||

| oxygenated sesquiterpenes | 9.5 | 12.2 | 7.7 | 12.4 | |||||||||||

| others | 11.7 | 10.8 | 14.2 | 13.7 | |||||||||||

| total | 94.5 | 93.6 | 93.8 | 93.0 | |||||||||||

Calculated linear retention index (LRI).

Reference LRI; % = percent by weight of EO; σ = standard deviation; § = identification by mass spectrometer (MS) only; and trace = <0.01%.

Major components in at least one EO are reported in bold.

The comparison through principal component analysis (PCA) among the main constituents of the EOs from the species G. miniphylla, G. rugulosa, G. buxifolia, G. laurifolia, G. cuicochensis, and G. sancti-antonii (see Figure 4), permitted to determine the relative closeness of the Gynoxys spp. so far studied for their volatile fraction compositions. In this statistical analysis, only major components were considered. On the one hand, G. miniphylla, G. cuicochensis, G. buxifolia, and G. laurifolia appeared to belong for similarity to the same group, whereas G. szyszylowiczii and G. rugulosa generated a different cluster. On the other hand, G. sancti-antonii was quite far from all the other plants of this family. These results were peculiarly counterintuitive since all these taxa, except G. buxifolia, apparently presented a quite similar chemical profile. In this sense, α-pinene and germacrene D were major components in practically all volatile fractions, whereas β-pinene, p-vinylguaiacol, (E)-β-caryophyllene, α-humulene, δ-cadinene, and α-cadinol were constantly present in all EOs, despite not always as major constituents.10−13 Finally, p-vinylguaiacol did not appear in G. buxifolia EO just because it was quantitatively dissolved in the hydrolate.12 Occasionally, a specific metabolite was a major component of a particular EO. This was for instance the case of δ-3-carene and trans-myrtanol acetate for G. miniphylla, and γ-curcumene for G. sancti-antonii. Furthermore, a series of heavy aliphatic compounds (mainly long-chained aldehydes, alkenes, and alkanes) was a characteristic pattern in the final part of many GC profiles.10,11,13 Finally, a special consideration must be given to G. buxifolia EO, whose chemical composition was completely different from all the other species, the major compounds being the very rare furanoeremophilane and bakkenolide A.12

Figure 4.

PCA plot of major components identified in the EOs of G. miniphylla, G. rugulosa, G. buxifolia, G. laurifolia, G. cuicochensis, and G. sancti-antonii.

2.2. Enantioselective Analysis

The enantioselective analyses permitted to identify four enantiomerically pure compounds in G. cuicochensis EO and seven in G. sancti-antonii volatile fraction. They were (1R,5R)-(+)-α-pinene, (S)-(+)-β-phellandrene, (R)-(−)-piperitone, and (S)-(−)-germacrene D for the first plant, whereas (1S,5S)-(−)-α-pinene, (1R,5R)-(+)-sabinene, (R)-(−)-β-phellandrene, (S)-(−)-limonene, (1S,2R,6R,7R,8R)-(+)-α-copaene, (R)-(−)-terpinen-4-ol, and (S)-(−)-germacrene D were the ones of the second plant. All the other analyzed chiral compounds were present as scalemic mixtures in both EOs. Unlike the chemical compositions, the enantiomeric distributions of all the known Gynoxys EOs did not apparently present a common pattern.10−13 The detailed results of the enantioselective analyses on G. sancti-antonii and G. cuicochensis EOs are shown in Table 2, where two chiral selectors (2,3-diacetyl-6-tert-butyldimethylsilyl-β-cyclodextrin and 2,3-diethyl-6-tert-butyldimethylsilyl-β-cyclodextrin) were used in order to ensure the best enantiomeric separations. As usual, the variable enantiomeric distribution of the same chiral metabolites, within a botanical genus or even the same species, is the result of different biological functions and properties, that two optical isomers can exert in a living organism.99,100

Table 2. Enantioselective Analysis of Some Chiral Terpenes from G. cuicochensis and G. sancti-antonii EOsc.

| enantiomers | LRI |

G. cuicochensis |

G. sancti-antonii |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| distribution (%) | ee (%) | distribution (%) | ee (%) | ||

| (1R,5R)-(+)-α-pinene | 924a | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| (1S,5S)-(−)-α-pinene | 926a | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| (1R,5R)-(+)-β-pinene | 949a | 44.7 | 10.6 | 19.3 | 61.3 |

| (1S,5S)-(−)-β-pinene | 959a | 55.3 | 80.7 | ||

| (1R,5R)-(+)-sabinene | 1008b | 68.2 | 36.4 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| (1S,5S)-(−)-sabinene | 1014b | 31.8 | |||

| (R)-(−)-α-phellandrene | 1019a | 4.7 | 90.7 | ||

| (S)-(+)α-phellandrene | 1022a | 95.3 | |||

| (R)-(−)-β-phellandrene | 1051a | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| (S)-(−)-limonene | 1058a | 97.5 | 95.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| (R)-(+)-limonene | 1074a | 2.5 | |||

| (S)-(+)-β-phellandrene | 1075b | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| (R)-(−)-linalool | 1179a | 56.3 | 12.5 | 47.8 | 4.5 |

| (S)-(+)-linalool | 1189a | 43.7 | 52.2 | ||

| (R)-(−)-piperitone | 1294a | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| (S)-(+)-α-terpineol | 1300a | 84.7 | 69.5 | ||

| (R)-(−)-α-terpineol | 1313a | 15.3 | |||

| (1S,2R,6R,7R,8R)-(+)-α-copaene | 1322a | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

| (R)-(−)-terpinen-4-ol | 1339b | 40.7 | 18.6 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| (S)-(+)-terpinen-4-ol | 1376b | 59.3 | |||

| (S)-(−)-germacrene D | 1465a | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

2,3-diacetyl-6-tert-butyldimethylsilyl-β-cyclodextrin.

2,3-diethyl-6-tert-butyldimethylsilyl-β-cyclodextrin column.

Linear retention indice = calculated LRI; ee = enantiomeric excess.

3. Conclusions

The dry leaves of G. cuicochensis and G. sancti-antonii produced, by steam-distillation, two EOs with the same yield of about 0.08% by weight. The yield was therefore a little higher than the one of most of the other Gynoxys EOs (about 0.02%), but lower than the one of G. buxifolia (about 0.1%). The PCA demonstrated that G. cuicochensis volatile fraction was quite similar to most of the other EOs of the same genus, whereas G. sancti-antonii produced the most dissimilar EO. Furthermore, the heavy aliphatic fraction that characterizes many Gynoxys EOs was much less important in these two species. Finally, the enantioselective analyses showed the usual variable enantiomeric distribution, with a greater presence of enantiomerically pure compounds in G. sancti-antonii EO. A more exhaustive statistical analysis of the chemical compositions and enantiomeric distributions will be conducted once the investigation on the genus is complete. Furthermore, after preparative distillation, this EO is suitable to be evaluated for possible biological activities.

4. Methods

4.1. Plant Material

The leaves of both wild plants were collected on March 6, 2021, from different shrubs of each species located within the radius of about 200 m around two reference points. For G. cuicochensis, the point coordinates were 03°39′57″S and 79°15′15″W, at the altitude of 2950 m above the sea level. For G. sancti-antonii, the collection point was located at 03°34′24″S and 79°11′10″W, whose altitude was 2973 m above the sea level. Both sites corresponded to the Province of Loja, Ecuador. The botanical identification was carried out by one of the authors (N.C.), and it was based on the original specimens conserved at the Missouri Botanical Garden Herbarium (St. Louis, MO, USA), with codes 05035975 (G. cuicochensis) and 2810342 (G. sancti-antonii). A reference botanical voucher for each collected species was also deposited at the herbarium of the Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja (UTPL), with codes 14273 and 14677 for G. cuicochensis and G. sancti-antonii, respectively. The plant materials were submitted to gentle drying the same day of collection, at 35 °C for 48 h, before being stored in a fresh dark place until use. Both investigation and collection were conducted under permission of the Ministry of Environment, Water and Ecological Transition of Ecuador, with MAATE registry number MAE-DNB-CM-2016-0048.

4.2. Distillation and Sample Preparation

The dry leaves of both plants were analytically steam-distilled in a modified Dean–Stark apparatus, as previously described in literature.11 Each species was distilled in four repetitions, for 4 h each. Each distillation was based on 80.6 g of dry plant material for G. cuicochensis, and 81.0 g for G. sancti-antonii. Each time, the volatile fraction was condensed over 2 mL of cyclohexane, containing n-nonane as internal standard (0.7 mg/mL). The obtained EO solutions in cyclohexane were stored at −15 °C and they were directly injectable in GC. Both cyclohexane and n-nonane were analytical grade and they were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

4.3. Qualitative (GC–MS) Chemical Analyses

The qualitative analyses were carried out with a Thermo Fisher Scientific GC, model Trace 1310, coupled to an ISQ 7000 MS from the same provider (Waltham, MA, USA). The instrument was equipped with two capillary columns, both 30 m long, 0.25 mm internal diameter, and 0.25 μm film thickness (Agilent Technology, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The stationary phases were nonpolar (DB-5 ms) and polar (HP-INNOWax) based on 5%-phenyl-methylpolysiloxane and polyethylene glycol, respectively. The injector was operated in the split mode (1 μL sample volume injected at 40:1 split ratio), set at the temperature of 230 °C. Helium was the carrier gas used at the constant flow of 1 mL/min (Indura S.A., Guayaquil, Ecuador). The GC oven was programmed, with both columns, according to the following thermal program: 40 °C for 10 min, a first gradient of 3 °C/min until 100 °C, a second gradient of 5 °C/min until 200 °C, and a third gradient of 10 °C/min until 230 °C, which were maintained for 20 min. The GC–MS transfer line and the electron ionization ion source (70 eV) were set at 230 °C. The MS, equipped with a single quadrupole analyzer, was operated in the SCAN mode and programmed for 40–400 m/z mass range. A mixture of n-alkane C9–C26, purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, was also injected in the same conditions as the EOs. The components of the volatile fractions were identified by comparing the linear retention indices (LRIs), calculated according to Van den Dool and Kratz,101 and mass spectra with data from literature (see Table 1).

4.4. Quantitative (GC–FID) Chemical Analyses

The quantitative chemical analyses were conducted on the same GC, columns, ad instrument configuration, as the qualitative ones, except for the use of a flame ionization detector (FID) instead of MS. The FID temperature was set at 230 °C, whereas the injector was operated at the split ratio of 10:1. All the EO constituents were quantified with external calibration, using n-nonane as internal standard and isopropyl caproate as calibration standard. The internal standard was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, whereas the calibration standard was synthetized in one of the authors’ laboratories and purified to 98.8% (GC–FID purity). A six-point calibration curve was traced for each column, as previously described in literature,102 obtaining a correlation coefficient of 0.997 in both cases. A relative response factor was calculated for each EO component versus isopropyl caproate, according to combustion enthalpy, as described in literature.103,104 The percent results were obtained as a mean value and standard deviation over four repetitions, relating the amount of each compound to the whole mass of the distilled EO, analytically calculated.

4.5. PCA of Some Gynoxys spp. EOs

The PCA was carried out on SIMCA software, purchased from Sartorius (Göttingen, Germany). The analysis was conducted only on major constituents, accounting for at least 1% in at least one EO. The compounds included in the analysis were as follows: α-pinene, β-pinene, δ-3-carene, β-phellandrene, trans-myrtanol acetate, p-vinylguiacol, (E)-β-caryophyllene, α-humulene, γ-curcumene, germacrene D, ar-curcumene, byciclogermacrene, δ-cadinene, α-muurolol, α-cadinol, furanoeremophilane, bakkenolide A, n-heneicosane, 1-docosene, 1-tricosene, n-tricosane, 1-tetracosene, n-pentacosane, 1-hexacosene, and n-heptacosane. The quantitative data submitted to PCA were the mean values of each component on both nonpolar and polar columns. The analysis included data from G. szyszylowiczii that, despite being still unpublished, are currently partially available.

4.6. Enantioselective Analyses

The enantioselective analyses were carried out in the same GC–MS instrument as the qualitative ones. Two enantioselective capillary columns were used: one based on a 2,3-diacetyl-6-tert-butyldimethylsilyl-β-cyclodextrin chiral selector and the other one based on a 2,3-diethyl-6-tert-butyldimethylsilyl-β-cyclodextrin stationary phase. The columns were 25 m long, 250 μm internal diameter and 0.25 μm phase thickness, both purchased from MEGA S.r.l. (Legnano, MI, Italy). The enantiomers were identified according to mass spectra and injection of enantiomerically pure standards, that were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The GC oven was programmed according to the following thermal program: 50 °C for 1 min, a thermal gradient of 2 °C/min until 220 °C, finally maintained for 10 min. As usual, the enantiomer identification was limited by standard availability.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja (UTPL) for supporting this investigation and open access publication. We are also grateful to Prof. Carlo Bicchi (University of Turin, Italy) and Dr. Stefano Galli (MEGA S.r.l., Legnano, Italy) for their support with enantioselective columns.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Malagón O.; Ramírez J.; Andrade J.; Morocho V.; Armijos C.; Gilardoni G. Phytochemistry and Ethnopharmacology of the Ecuadorian Flora. A Review. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2016, 11, 1934578X1601100307. 10.1177/1934578X1601100307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armijos C.; Ramírez J.; Salinas M.; Vidari G.; Suárez A. Pharmacology and Phytochemistry of Ecuadorian Medicinal Plants: An Update and Perspectives. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 1145. 10.3390/ph14111145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNEP-WCMC . Megadiverse Countries. https://www.biodiversitya-z.org/content/megadiverse-countries (accessed December 11, 2023).

- Chiriboga X.; Gilardoni G.; Magnaghi I.; Vita Finzi P.; Zanoni G.; Vidari G. New Anthracene Derivatives from Coussarea macrophylla. J. Nat. Prod. 2003, 66, 905–909. 10.1021/np030066i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilardoni G.; Chiriboga X.; Vita Finzi P.; Vidari G. New 3,4-Secocycloartane and 3,4-Secodammarane Triterpenes from the Ecuadorian Plant Coussarea macrophylla. Chem. Biodiversity 2015, 12, 946–954. 10.1002/cbdv.201400182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivanco K.; Montesinos J. V.; Cumbicus N.; Malagón O.; Gilardoni G. The essential oil from leaves of Mauria heterophylla Kunth (Anacardiaceae): chemical and enantioselective analyses. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2023, 35, 563–569. 10.1080/10412905.2023.2266430. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado Y. E.; Malagón O.; Cumbicus N.; Gilardoni G. A new essential oil from the native Ecuadorian species Steiractinia sodiroi (Hieron.) S.F. Blake (Asteraceae): chemical and enantioselective analyses. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 17180. 10.1038/s41598-023-44524-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilardoni G.; Enríquez A. A.; Maldonado Y. E.; Cumbicus N.; Malagón O. A New Essential Oil from the Native Andean Species Nectandra laurel Klotzsch ex Nees of Southern Ecuador: Chemical and Enantioselective Analyses. Plants 2023, 12, 3331. 10.3390/plants12183331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa S.; Bec N.; Larroque C.; Ramírez J.; Sgorbini B.; Bicchi C.; Gilardoni G. Chemical Enantioselective, and Sensory Analysis of a Cholinesterase Inhibitor Essential Oil from Coreopsis triloba S.F. Blake (Asteraceae). Plants 2019, 8, 448. 10.3390/plants8110448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malagón O.; Cartuche P.; Montaño A.; Cumbicus N.; Gilardoni G. A new essential oil from the leaves of the endemic Andean species Gynoxys miniphylla Cuatrec. (Asteraceae): chemical and enantioselective analyses. Plants 2022, 11, 398. 10.3390/plants11030398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado Y. E.; Malagón O.; Cumbicus N.; Gilardoni G. A New Essential Oil from the Leaves of Gynoxys rugulosa Muschl. (Asteraceae) Growing in Southern Ecuador: Chemical and Enantioselective Analyses. Plants 2023, 12, 849. 10.3390/plants12040849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cumbicus C.; Malagón O.; Cumbicus N.; Gilardoni G. The leaf essential oil of Gynoxys buxifolia (Kunth) Cass. (Asteraceae): a good source of furanoeremophilane and bakkenolide A. Plants 2023, 12, 1323. 10.3390/plants12061323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilardoni G.; Lara L. R.; Cumbicus N.; Malagón O. A New Leaf Essential Oil from Endemic Gynoxys laurifolia (Kunth) Cass. of Southern Ecuador: Chemical and Enantioselective Analyses. Plants 2023, 12, 2878. 10.3390/plants12152878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadereit J. W.; Jeffrey C.. Flowering Plants Eudicots. Asterales; Kubitzki K., Ed.; The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2007; Vol. VIII. [Google Scholar]

- Tropicos.Org . Missouri Botanical Garden. https://www.tropicos.org (accessed December 11, 2023).

- Jorgensen P.; León-Yanez S.. Catalogue of the Vascular Plants of Ecuador; Missouri Botanical Garden Press: St. Louis, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bohlmann F.; Grenz M.; Suwita A. Inhaltsstoffe aus Gynoxys- und Pseudogynoxys-arten. Phytochemistry 1977, 16, 774–776. 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)89257-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jakupovic J.; Zdero C.; King R. M. Furanoeremophilanes from Gynoxys Species. Phytochemistry 1995, 40, 1677–1679. 10.1016/0031-9422(95)00543-G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adams R. P.Identification of Essential Oil Components by Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry, 4th ed.; Allured Publishing Corporation: Carol Stream, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Shellie R.; Marriott P.; Zappia G.; Mondello L.; Dugo G. Interactive use of linear retention indices on polar and apolar columns with an MS-Library for reliable characterization of Australian tea tree and other Melaleuca sp. Oils. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2003, 15, 305–312. 10.1080/10412905.2003.9698597. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loayza I.; de Groot W.; Lorenzo D.; Dellacassa E.; Mondello L.; Dugo G. Composition of the essential oil of Porophyllum ruderale (Jacq.) Cass. from Bolivia. Flavour Fragrance J. 1999, 14, 393–398. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cavaleiro C.; Salgueiro L. R.; Miguel M. G.; Proença da Cunha A. Analysis by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry of the volatile components of Teucrium lusitanicum and Teucrium algarbiensis. J. Chromatogr. A 2004, 1033, 187–190. 10.1016/j.chroma.2004.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto E.; Pina-Vaz C.; Salgueiro L.; Gonçalves M. J.; Costa-de-Oliveira S.; Cavaleiro C.; Palmeira A.; Rodrigues A.; Martinez-de-Oliveira J. Antifuncal activity of the essential oil Thymus pulegioides on Candida, Aspergillus and dermatophyte species. J. Med. Microbiol. 2006, 55, 1367–1373. 10.1099/jmm.0.46443-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozo-Bayon M. A.; Ruiz-Rodriguez A.; Pernin K.; Cayot N. Influence of eggs on the aroma composition of a sponge cake and on the aroma release in model studies on flavored sponge cakes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 1418–1426. 10.1021/jf062203y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanciullino A.-L.; Gancel A.-L.; Froelicher Y.; Luro F.; Ollitrault P.; Brillouet J.-M. Effects of Nucleo-cytoplasmic Interactions on Leaf Volatile Compounds from Citrus Somatic Diploid Hybrids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 4517–4523. 10.1021/jf0502855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shellie R.; Mondello L.; Marriott P.; Dugo G. Characterisation of lavender essential oils by using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry with correlation of linear retention indices and comparison with comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2002, 970, 225–234. 10.1016/S0021-9673(02)00653-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möllenbeck S.; König T.; Schreier P.; Schwab W.; Rajaonarivony J.; Ranarivelo L. Chemical composition and analyses of enantiomers of essential oils from Madagascar. Flavour Fragrance J. 1997, 12, 63–69. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brophy J. J.; Goldsack R. J.; Forster P. I. Essential oils of the genus Lophostemon (Myrtaceae). Flavour Fragrance J. 2000, 15, 17–20. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boido E.; Lloret A.; Medina K.; Fariña L.; Carrau F.; Versini G.; Dellacassa E. Aroma composition of Vitis vinifera Cv. tannat: the typical red wine from Uruguay. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 5408–5413. 10.1021/jf030087i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi F.; Cantoni C.; Careri M.; Chiesa L.; Musci M.; Pinna A. Characterization of the aromatic profile for the authentication and differentiation of typical Italian dry-sausages. Talanta 2007, 72, 1552–1563. 10.1016/j.talanta.2007.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flamini G.; Cioni P. L.; Morelli I.; Maccioni S.; Baldini R. Phytochemical typologies in some populations of Myrtus communis L. on Caprione Promontory (East Liguria, Italy). Food Chem. 2004, 85, 599–604. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2003.08.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi F.; Careri M.; Mangia A.; Musci M. Retention indices in the analysis of food aroma volatile compounds in temperature-programmed gas chromatography: Database creation and evaluation of precision and robustness. J. Sep. Sci. 2007, 30, 563–572. 10.1002/jssc.200600393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassole I. H. N.; Ouattara A. S.; Nebie R.; Ouattara C. A. T.; Kabore Z. I.; Traore S. A. Chemical composition and antibacterial activities of the essential oils of Lippia chevalieri and Lippia multiflora from Burkina Faso. Phytochemistry 2003, 62, 209–212. 10.1016/S0031-9422(02)00477-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallier A.; Prost C.; Serot T. Influence in rearing conditions on the volatile compounds of cooked fillets of Silurus glanis (European catfish). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 7204–7211. 10.1021/jf050559o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salgueiro L. R.; Pinto E.; Goncalves M. J.; Costa I.; Palmeira A.; Cavaleiro C.; Pina-Vaz C.; Rodrigues A. G.; Martinez-De-Oliveira J. Antifungal activity of the essential oil of Thymus capitellatus against Candida, Aspergillus and dermatophyte strains. Flavour Fragrance J. 2006, 21, 749–753. 10.1002/ffj.1610. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stashenko E. E.; Cervantes M.; Combariza Y.; Fuentes H.; Martínez J. R. HRGC/FID and HRGC/MSD analysis of the secondary metabolites obtained by different extraction methods from Lepechinia schiedeana, an in vitro evaluation of its antioxidant activity. J. High Resolut. Chromatogr. 1999, 22, 343–349. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahattanatawee K.; Perez-Cacho P. R.; Davenport T.; Rouseff R. Comparison of three lychee cultivar odor profiles using gas chromatography-olfactometry and gas chromatography-sulfur detection. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 1939–1944. 10.1021/jf062925p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundakovic T.; Fokialakis N.; Kovacevic N.; Chinou I. Essential oil composition of Achillea lingulata and A. umbellata. Flavour Fragrance J. 2007, 22, 184–187. 10.1002/ffj.1778. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cho I. H.; Namgung H.-J.; Choi H.-K.; Kim Y.-S. Volatiles and key odorants in the pileus and stipe of pine-mushroom (Tricholoma matsutake Sing.). Food Chem. 2008, 106, 71–76. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.05.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruther J. Retention index database for identification of general green leaf volatiles in plants by coupled capillary gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2000, 890, 313–319. 10.1016/S0021-9673(00)00618-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couladis M.; Chinou I. B.; Tzakou O.; Loukis A. Composition and antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of Ballota pseudodictamnus L. Bentham. Phytother. Res. 2002, 16, 723–726. 10.1002/ptr.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umano K.; Hagi Y.; Nakahara K.; Shoji A.; Shibamoto T. Volatile chemicals identified in extracts from leaves of Japanese mugwort (Artemisia princeps Pamp.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 3463–3469. 10.1021/jf0001738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cozzani S.; Muselli A.; Desjobert J.-M.; Bernardini A.-F.; Tomi F.; Casanova J. Chemical composition of essential oil of Teucrium polium subsp. capitatum (L.) from Corsica. Flavour Fragrance J. 2005, 20, 436–441. 10.1002/ffj.1463. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Riu-Aumatell M.; Lopez-Tamames E.; Buxaderas S. Assessment of the Volatile Composition of Juices of Apricot, Peach, and Pear According to Two Pectolytic Treatments. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 7837–7843. 10.1021/jf051397z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabulal B.; Dan M.; John A.; Kurup R.; Chandrika S. P.; George V. Phenylbutanoid-rich rhizome oil of Zingiber neesanum from Western Ghats, southern India. Flavour Fragrance J. 2007, 22, 521–524. 10.1002/ffj.1834. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saroglou V.; Marin P. D.; Rancic A.; Veljic M.; Skaltsa H. Composition and antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of six Hypericum species from Serbia. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2007, 35, 146–152. 10.1016/j.bse.2006.09.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Werkhoff P.; Güntert M.; Krammer G.; Sommer H.; Kaulen J. Vacuum headspace method in aroma research: flavor chemistry of yellow passion fruits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998, 46, 1076–1093. 10.1021/jf970655s. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano P. R.; Miracle E. R.; Krause A. J.; Drake M.; Cadwallader K. R. Effect of cold storage and packaging material on the major aroma components of sweet cream butter. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 7840–7846. 10.1021/jf071075q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahadevan K.; Farmer L. Key Odor Impact Compounds in Three Yeast Extract Pastes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 7242–7250. 10.1021/jf061102x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto E.; Salgueiro L. R.; Cavaleiro C.; Palmeira A.; Goncalves M. J. In vitro susceptibility of some species of yeasts and filamentous fungi to essential oils of Salvia oficinalis. Ind. Crops Prod. 2007, 26, 135–141. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2007.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J.; Rouseff R. L. Characterization of aroma-impact compounds in cold-pressed grapefruit oil using time-intensity GC-olfactometry and GC-MS. Flavour Fragrance J. 2001, 16, 457–463. 10.1002/ffj.1041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ledauphin J.; Saint-Clair J.-F.; Lablanquie O.; Guichard H.; Founier N.; Guichard E.; Barillier D. Identification of trace volatile compounds in freshly distilled calvados and cognac using preparative separations coupled with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 5124–5134. 10.1021/jf040052y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varlet V.; Knockaert C.; Prost C.; Serot T. Comparison of odor-active volatile compounds of fresh and smoked salmon. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 3391–3401. 10.1021/jf053001p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verzera A.; Trozzi A.; Zappala M.; Condurso C.; Cotroneo A. Essential Oil Composition of Citrus meyerii Y. Tan. and Citrus medica L. cv. Diamante and Their Lemon Hybrids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 4890–4894. 10.1021/jf047879c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klesk K.; Qian M. Aroma extract dilution analysis of Cv. Marion (Rubus spp. hyb) and Cv. Evergreen (R. iaciniatus L.) blackberries. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 3436–3441. 10.1021/jf0262209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vichi S.; Romero A.; Tous J.; Tamames E. L.; Buxaderas S. Determination of volatile phenols in virgin olive oils and their sensory significance. J. Chromatogr. A 2008, 1211, 1–7. 10.1016/j.chroma.2008.09.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brophy J. J.; Goldsack R. J.; Punruckvong A.; Bean A. R.; Forster P. I.; Lepschi B. J.; Doran J. C.; Rozefelds A. C. Leaf essential oils of the genus Leptospermum (Myrtaceae) in eastern Australia. Part 7. Leptospermum petersonii, L. liversidgei and allies. Flavour Fragrance J. 2000, 15, 342–351. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flamini G.; Tebano M.; Cioni P. L.; Bagci Y.; Dural H.; Ertugrul K.; Uysal T.; Savran A. A multivariate statistical approach to Centaurea classification using essential oil composition data of some species from Turkey. Plant Syst. Evol. 2006, 261, 217–228. 10.1007/s00606-006-0448-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolomeazzi R.; Berno P.; Pizzale L.; Conte L. S. Sesquiterpene, Alkene, and Alkane Hydrocarbons in Virgin Olive Oils of Different Varieties and Geographical Origins. J. Agric. Química Alimentaria. 2001, 49, 3278–3283. 10.1021/jf001271w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jirovetz L.; Buchbauer G.; Stoyanova A.; Balinova A.; Guangjiun Z.; Xihan M. Solid phase microextraction/gas chromatographic and olfactory analysis of the scent and fixative properties of the essential oil of Rosa damascena L. from China. Flavour Fragrance J. 2005, 20, 7–12. 10.1002/ffj.1375. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm M. G.; Jell J. A.; Cass D. M. Jr. Characterization of the major odorants found in the peel oil of Citrus reticulata Blanco cv. Clementine using gas chromatography-olfactometry. Flavour Fragrance J. 2003, 18, 275–281. 10.1002/ffj.1188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ollé D.; Baumes R. L.; Bayonove C. L.; Lozano Y. F.; Sznaper C.; Brillouet J.-M. Comparison of free and glycosidically linked volatile components from polyembryonic and monoembryonic mango (Mangifera indica L.) cultivars. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998, 46, 1094–1100. 10.1021/jf9705781. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T. H.; Thuy N. T.; Shin J. H.; Baek H. H.; Lee H. J. Aroma-active compounds of miniature beefsteak plant (Mosla dianthera Maxim). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 2877–2881. 10.1021/jf000219x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan S. S.; Goddik L.; Qian M. C. Aroma Compounds in Sweet Whey Powder. J. Dairy Sci. 2004, 87, 4057–4063. 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(04)73547-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahim Sajjadi S.; Eskandari B. Chemical constituents of the essential oil of Nepeta oxyodonta. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2005, 41, 175–177. 10.1007/s10600-005-0106-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gauvin A.; Ravaomanarivo H.; Smadja J. Comparative analysis by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry of the essential oils from bark and leaves of Cedrelopsis grevei Baill, an aromatic and medicinal plant from Madagascar. J. Chromatogr. A 2004, 1029, 279–282. 10.1016/j.chroma.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjeldsen F.; Christensen L. P.; Edelenbos M. Changes in volatile compounds of carrots (Daucus carota L.) during refrigerated and frozen storage. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 5400–5407. 10.1021/jf030212q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gancel A.-L.; Ollitrault P.; Froelicher Y.; Tomi F.; Jacquemond C.; Luro F.; Brillouet J.-M. Leaf volatile compounds of six citrus somatic allotetraploid hybrids originating from various combinations of lime, lemon, citron, sweet orange, and grapefruit. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 2224–2230. 10.1021/jf048315b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maric S.; Jukic M.; Katalinic V.; Milos M. Comparison of chemical composition and free radical scavenging ability of glycosidically bound and free volatiles from Bosnian pine (Pinus heldreichii Christ. var. leucodermis). Molecules 2007, 12, 283–289. 10.3390/12030283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoni V.; Tomi F.; Casanova J. A daucane-type sesquiterpene from Faucus carota seed oil. Flavour Fragrance J. 1999, 14, 268–272. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Le Quere J.-L.; Latrasse A. Composition of the Essential Oils of Blackcurrant Buds (Ribes nigrum L.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 1990, 38, 3–10. 10.1021/jf00091a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paolini J.; Muselli A.; Bernardini A.-F.; Bighelli A.; Casanova J.; Costa J. Thymol derivatives from essential oil of Doronicum corsicum L. Flavour Fragrance J. 2007, 22, 479–487. 10.1002/ffj.1824. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stevanovic T.; Garneau F.-X.; Jean F.-I.; Gagnon H.; Vilotic D.; Petrovic S.; Ruzic N.; Pichette A. The essential oil composition of Pinus mugo Turra from Serbia. Flavour Fragrance J. 2005, 20, 96–97. 10.1002/ffj.1390. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paolini J.; Costa J.; Bernardini A. F. Analysis of the essential oil from the roots of Eupatorium cannabinum subsp. corsicum (L.) by GC, GC-MS and 13C-NMR. Phytochem. Anal. 2007, 18, 235–244. 10.1002/pca.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stashenko E. E.; Prada N. Q.; Martínez J. R. HRGC/FID/NP and HRGC/MSD study of Colombian Ylang-Ylang (Cananga odorata) oils obtained by different extraction techniques. J. High Resolut. Chromatogr. 1996, 19, 353–358. 10.1002/jhrc.1240190609. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bendiabdellah A.; El Amine Dib M.; Djabou N.; Allali H.; Tabti B.; Muselli A.; Costa J. Biological activities and volatile constituents of Daucus muricatus L. from Algeria. Chem. Cent. J. 2012, 6, 48. 10.1186/1752-153x-6-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabouss A. E.; Charrouf Z.; Faid M.; Garneau F.-X.; Collin G. Composición química y actividad antimicrobiana del aceite esencial de hoja de Argania spinosa L. Skeels. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2002, 14, 147–149. 10.1080/10412905.2002.9699801. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petrakis P. V.; Tsitsimpikou C.; Tzakou O.; Couladis M.; Vagias C.; Roussis V. Needle volatiles from five Pinus species growing in Greece. Flavour Fragrance J. 2001, 16, 249–252. 10.1002/ffj.990. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli J.-F.; Tomi F.; Bernardini A.-F.; Casanova J. Composition and chemical variability of the bark oil of Cedrelopsis grevei H. Baillon from Madagascar. Flavour Fragrance J. 2003, 18, 532–538. 10.1002/ffj.1263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu E. J.; Kim T. H.; Kim K. H.; Lee H. J. Aroma-active compounds of Pinus densiflora (red pine) needles. Flavour Fragrance J. 2004, 19, 532–537. 10.1002/ffj.1337. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mondello L.; Zappia G.; Cotroneo A.; Bonaccorsi I.; Chowdhury J. U.; Yusuf M.; Dugo G. Studies on the essential oil-bearing plants of Bangladesh. Part VIII. Composition of some Ocimum oils O. basilicum L. var. purpurascens; O. sanctum L. green; O. sanctum L. purple; O. americanum L., citral type; O. americanum L., camphor type. Flavour Fragrance J. 2002, 17, 335–340. 10.1002/ffj.1108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paolini J.; Tomi P.; Bernardini A.-F.; Bradesi P.; Casanova J.; Kaloustian J. Detailed analysis of the essential oil from Cistus albidus L. by combination of GC/RI, GC/MS and 13C-NMR spectroscopy. J. Agric. Res. 2008, 22, 1270–1278. 10.1080/14786410701766083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeoka G.; Butter R. G.. Volatile constituents of pineapple (Ananas comosus [L.] Merr.). Flavor Chemistry Trends and Developments; Teranishi R., Buttery R. G., Shahidi F., Eds.; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1989; pp 223–237. [Google Scholar]

- Zouari N.; Ayadi I.; Fakhfakh N.; Rebai A.; Zouari S. Variations of chemical composition of essential oils in wild populations of Thymus algeriensis Boiss. et Reut., a North African endemic species. Lipids Health Dis. 2012, 11, 28. 10.1186/1476-511x-11-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chagonda L. S.; Makanda C. D.; Chalchat J.-C. The essential oils of Ocimum canum Sims (basilic camphor) and Ocimum urticifolia Roth from Zimbabwe. Flavour Fragrance J. 2000, 15, 23–26. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh B.; Kumar R.; Bhandari S.; Pathania S.; Lal B. Volatile constituents of natural Boswellia serrata oleo-gum-resin and commercial samples. Flavour Fragrance J. 2007, 22, 145–147. 10.1002/ffj.1772. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mardarowicz M.; Wianowska D.; Dawidowicz A. L.; Sawicki R. Comparison of terpene composition in Engelmann Spruce (Picea engelmanii) using hydrodistillation, SPME and PLE. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung C 2004, 59, 641–648. 10.1515/znc-2004-9-1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H.-S. Headspace analyses of fresh leaves and stems of Angelica gigas Nakai, a Korean medicinal herb. Flavour Fragrance J. 2006, 21, 604–608. 10.1002/ffj.1602. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazawa M.; Kawauchi Y.; Utsumi Y.; Takahashi T. Character impact odorants of wild edible plant - Cacalia hastata L. var. orientalis - used in Japanese traditional food. J. Oleo Sci. 2010, 59, 527–533. 10.5650/jos.59.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabulal B.; Dan M.; Anil J. J.; Kurup R.; Pradeep N. S.; Valsamma R. K.; George V. Caryophyllene-rich rhizome oil of Zingiber nimmonii from South India: Chemical characterization and antimicrobial activity. Phytochemistry 2006, 67, 2469–2473. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flamini G.; Cioni P. L.; Morelli I. Essential oils of Galeopsis pubescens and G. tetrahit from Tuscany (Italy). Flavour Fragrance J. 2004, 19, 327–329. 10.1002/ffj.1307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Minh Tu N. T.; Thanh L. X.; Une A.; Ukeda H.; Sawamura M. Volatile constituents of Vietnamese pummelo, orange, tangerine and lime peel oils. Flavour Fragrance J. 2002, 17, 169–174. 10.1002/ffj.1076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stashenko E. E.; Torres W.; Morales J. R. M. A study of the compositional variation of the essential oil of ylang-ylang (Cananga odorata Hook Fil. et Thomson, forma genuina) during flower development. J. High Resolut. Chromatogr. 1995, 18, 101–104. 10.1002/jhrc.1240180206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shimoda M.; Yoshimura Y.; Yoshimura T.; Noda K.; Osajima Y. Volatile flavor compounds of sweetened condensed milk. J. Food Sci. 2001, 66, 804–807. 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2001.tb15176.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vedernikov D. N.; Roshchin V. I. Extractive compounds of Birch Buds (Betula pendula Roth.): I. Composition of fatty acids, hydrocarbons, and esters. Russ. J. Bioorg. Chem. 2010, 36, 894–898. 10.1134/s1068162010070174. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iscan G.; Kirimer N.; Kurkcuoglu M.; Arabaci T.; Küpeli̇ E.; Can Başer K. H. Biological Activity and Composition of the Essential Oils of Achillea schischkinii Sosn. and Achillea aleppica DC. subsp. aleppica. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 170–173. 10.1021/jf051644z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y.; White E.. Retention Data; NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center, 2008.

- Zaikin V. G.; Borisov R. S. Chromatographic-mass spectrometric analysis of Fischer–Tropsch synthesis products. J. Anal. Chem. 2002, 57, 544–551. 10.1023/A:1015754120136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brenna E.; Fuganti C.; Serra S. Enantioselective Perception of Chiral Odorants. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2003, 14, 1–42. 10.1016/S0957-4166(02)00713-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lis-Balcnin M.; Ochocka R. J.; Deans S. G.; Asztemborska M.; Hart S. Differences in bioactivity between the enantiomers of α-pinene. J. Essent. Oil Res. 1999, 11, 393–397. 10.1080/10412905.1999.9701162. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Dool H.; Kratz P. D. A Generalization of the Retention Index System Including Linear Temperature Programmed Gas—Liquid Partition Chromatography. J. Chromatogr. 1963, 11, 463–471. 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)80947-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilardoni G.; Matute Y.; Ramírez J. Chemical and Enantioselective Analysis of the Leaf Essential Oil from Piper coruscans Kunth (Piperaceae), a Costal and Amazonian Native Species of Ecuador. Plants 2020, 9, 791. 10.3390/plants9060791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Saint Laumer J. Y.; Cicchetti E.; Merle P.; Egger J.; Chaintreau A. Quantification in Gas Chromatography: Prediction of Flame Ionization Detector Response Factors from Combustion Enthalpies and Molecular Structures. Anal. Chem. 2010, 82, 6457–6462. 10.1021/ac1006574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tissot E.; Rochat S.; Debonneville C.; Chaintreau A. Rapid GC–FID quantification technique without authentic samples using predicted response factors. Flavour Fragrance J. 2012, 27, 290–296. 10.1002/ffj.3098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]