Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

To describe the factors affecting critical care capacity and how critical care organizations (CCOs) within academic centers in the U.S. flow-size critical care resources under normal operations, strain, and surge conditions.

DATA SOURCES:

PubMed, federal agency and American Hospital Association reports, and previous CCO survey results were reviewed.

STUDY SELECTION:

Studies and reports of critical care bed capacity and utilization within CCOs and in the United States were selected.

DATA EXTRACTION:

The Academic Leaders in the Critical Care Medicine Task Force established regular conference calls to reach a consensus on the approach of CCOs to “flow-sizing” critical care services.

DATA SYNTHESIS:

The approach of CCOs to “flow-sizing” critical care is outlined. The vertical (relation to institutional resources, e.g., space allocation, equipment, personnel redistribution) and horizontal (interdepartmental, e.g., emergency department, operating room, inpatient floors) integration of critical care delivery (ICUs, rapid response) for healthcare organizations and the methods by which CCOs flow-size critical care during normal operations, strain, and surge conditions are described. The advantages, barriers, and recommendations for the rapid and efficient scaling of critical care operations via a CCO structure are explained. Comprehensive guidance and resources for the development of “flow-sizing” capability by a CCO within a healthcare organization are provided.

CONCLUSIONS:

We identified and summarized the fundamental principles affecting critical care capacity. The taskforce highlighted the advantages of the CCO governance model to achieve rapid and cost-effective “flow-sizing” of critical care services and provide recommendations and resources to facilitate this capability. The relevance of a comprehensive approach to “flow-sizing” has become particularly relevant in the wake of the latest COVID-19 pandemic. In light of the growing risks of another extreme epidemic, planning for adequate capacity to confront the next critical care crisis is urgent.

Keywords: bed capacity, bed utilization, critical care organization, flow-sizing, intensive care unit, pandemic

As part of the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) directive to comprehensibly describe critical care organizations (CCOs) in the United States, the taskforce of Academic Leaders in the Critical Care Medicine (ALCCM) was convened in 2016 to develop a series of consensus articles with toolkits for advancing CCOs (1–6). A CCO is defined as an “integrated” organization with advanced horizontal and vertical governance models, headed by a physician with primary control over the majority, if not all, of the ICUs in the hospital or health system (1). The main objectives of this final consensus article from the ALCCM taskforce are to describe the factors affecting critical care capacity, and how CCOs within academic centers in the U.S. flow-size critical care resources under normal operations, strain, and surge conditions.

Patient flow refers to the movement of patients across all stages of their care; optimal management of this complex process, in conjunction with adequate bed capacity, is essential to mitigate patient flow disruption in any system. This is true not only during normal operations but especially during unexpected surges such as natural disasters or pandemics (7, 8). High demand for critical care services and limited ICU bed availability can adversely affect hospital-wide patient throughput, particularly in emergency departments and post-anesthesia care units. This imbalance can also increase the mortality of critically ill patients due to prolonged wait times for ICU bed assignments (9, 10). During the recent COVID-19 pandemic, countries hardest hit struggled to accommodate the large numbers of patients requiring hospitalization, ICU beds, and mechanical ventilatory support (11).

Determining the number of beds needed for optimal operations is an intricate process and the associated administrative decisions are affected by multiple factors. Among them, national healthcare and state-based Departments of Health policies, costs, available resources, models of care, patient population by age breakdown, population growth trends, and demand forecasting (12).

“Flow-sizing” in critical care refers to the strategic management of critical care resources according to increasing or decreasing patient flow and adapting the resources available to the fluctuating needs (Table 1). Its goal is to match capacity and critical care demands to ensure that all patients receive appropriate care.

TABLE 1.

Cardinal Definitions

| Concept | Definition |

|---|---|

| CCOs | Organizations with advanced governance structure headed by an intensivist physician with primary governance over the majority of ICUs and critical care operations in a hospital or a healthcare system. These organizations provide well-coordinated, multidisciplinary, and effective responses to the critical care needs of the system. CCOs embrace evidence-based practices, continuous quality improvement initiatives, and make effective use of technology. In addition to the CCO’s head, the leadership include ICU medical and nursing directors, administrative and academic program directors working collaboratively to ensure high-quality, patient-centered care, and effective use of the CCOs’ resources. |

| Patient-flow | It is the movement of patients through the various stages of the healthcare system, from their initial point of entry to their eventual discharge or transfer to another facility. Patient flow includes all the steps involved in diagnosing, treating, and managing the patient’s care, including assessments, medical procedures, and administration of medications. |

| Flow-sizing | It refers to the strategic management of critical care resources according to increasing or decreasing patient flow and adapting the resources available to the fluctuating needs. The goal is to match capacity and critical care demands to ensure that all patients receive appropriate care. |

| Total hospital capacity | It refers to the total number of licensed beds, whether staffed or not. |

| Operational capacity (or actual) | It can be defined as the number of beds readily available, equipped, and staffed licensed beds at any given time. Actual capacity can vary from hour to hour or day to day during large oscillations in patients’ volume. |

| Idle capacity (or unused beds) | Hospitals and ICUs may have a large proportion of “phantom” or nonoperational beds (licensed beds that are unstaffed or unavailable for use) at any given time (idle capacity). This situation is common (13), and instead of considering it wasteful, the dormant capacity can be a safety valve to accommodate different types of patient surges during emergencies (e.g., Hurricane Katrina, Tropical Storm Allison) (17–19). |

| Occupancy | Total number of patient beds/total number of available bed hours. |

| ICU capacity | Adequate ability to provide high-quality care for both current and new ICU admissions on a particular day is termed ICU. |

| Strained ICU capacity | A discrepancy between the availability of ICU resources and demand to admit and provide high-quality care for patients with critical illness. |

| Contingency capacity | Adaptations to medical care spaces, staffing constraints, and supply shortages without significant impact on medical care delivery. |

| Crisis capacity | Adaptations that will have a significant impact on routine care delivery and operations. |

CCO = critical care organization.

METHODS

Data Sources and Study Selection

We comprehensively reviewed the literature in search for the methodology used to determine ICU size, capacity, strain, and ICU patient-flow management. PubMed, federal agency and American Hospital Association reports, and the results of previous CCO surveys and analyses were reviewed (1–6). Studies and reports of critical care bed capacity and utilization within CCOs and in the United States were selected, as well as the previous CCOs survey conducted by the ALCCM (1).

Data Synthesis

The ALCCM Task Force conducted regular conference calls to discuss the evidence gathered and reach a consensus on the approach of CCOs to “flow-sizing” critical care services. The methodologies and process to regulate ICU size and capacity and factors affecting these determinations were discussed.

Target Audiences

The intended audience for the article encompasses critical care professionals, administrators, healthcare regulatory bodies, hospital architects, and engineers who play a role in determining critical care capacity and the utilization of these resources.

Outcomes

After extensive critical analysis of the identified relevant data, the ALCCM taskforce made recommendations based on the group consensus. The final document was then subjected to external review and revision by subject experts.

RESULTS

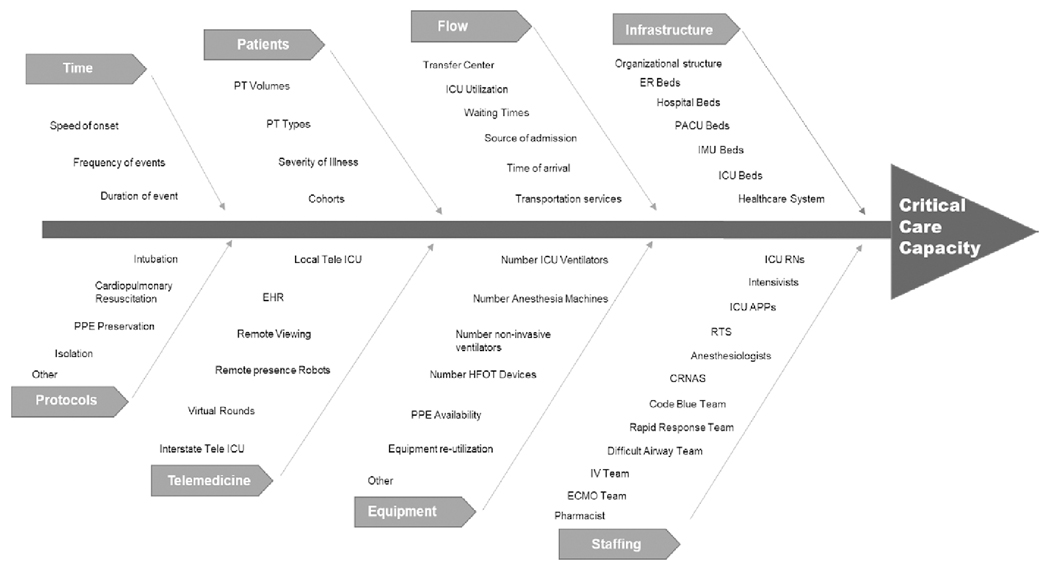

The taskforce identified multiple components to determine the operational versus the licensed critical care capacity including: a) number of ICU beds, b) infrastructure and equipment (e.g., ventilators), and c) staff availability (e.g., nurses, respiratory therapists, intensivists) (12, 17–20). Factors like the efficiency of patient-flow management (e.g., response to bottle necks, after-hours discharge, ICU readmission) and resiliency for unexpected or unplanned high demand (e.g., surges) were found to play an important role in the dynamic capacity of a unit (see definitions in Table 1). Having capacity is important, but it is just part of the overall healthcare delivery equation. In reality, the allocation of ICU resources is also affected by accessibility, affordability, and acceptability (21) as well as ICU patient acuity, readmission rate, census, and after-hours discharge. Capacity may become strained when there is a discrepancy between available ICU resources, ICU bed demand, and the ability to provide high-quality care (13–15) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Factors affecting critical care capacity. APPs = advanced practice providers, CRNAs = certified registered nurse anesthetists, ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, EHR = electronic health record, ER = emergency department, HFOT = high-flow oxygen therapy, IMU = intermediate medical unit, PACU = post-anesthesia care unit, PPE = personal protective equipment, PT = patient, RN = registered nurse, RTs = respiratory therapists.

Main Elements of Operational Capacity

These elements are “fundamental” in “flow-sizing” during normal operations as well as in strain or crisis surges conditions and include:

Unit size (number of ICU beds): Determining the optimal bed number of an ICU is a complex process and depends on multiple variables as noted above, inclusive of the physical space allocated by hospitals for ICU beds and their need for specialty clinical programs. The traditional use of ratios or percentages do not account for the stochastic nature of critical care medicine and requires consideration of specific institutional factors (e.g., length of stay [LOS], staffing patterns, resources, available services, types of surgeries performed, health of the population and demographic trends, space and competing institutional programs). In a recent systematic review of 11 models and five methods for determining the optimal number of beds, the authors were not able to identify a best method or find specific standards for the required number of beds at a hospital or regional level (12). Many other important external factors harder to predict and control were identified (e.g., population changes, seasonal effects, epidemiological factors, political pressures, inter-regional flows and access). The “formulas” and “basic framework” for modeling and determining the unit size are delineated in Table 2 (16, 22–28).

Equipment and infrastructure: The basic structural and equipment needs of an ICU have been well described by European and U.S. critical care society task forces (29, 30). These groups identified the key elements of a unit and provided standards for infection control, team working areas, monitoring, and others. A sudden imbalance in the supply/demand can significantly affect the capability of any unit. The recent COVID-19 pandemic highlighted critical gaps such as insufficient number of hospital-based ventilators to respond to the crisis. Furthermore, the pandemic highlighted the limitations of relying upon the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Strategic National Stockpile (SNS), which had approximately 12,000 old ventilators for the entire country. The SNS was later replenished under the Defense Production Act (31). Additionally, equipment can also be affected by disruption in the supply, as was the case with personal protective equipment (PPE) (e.g., N-95 facemasks, gowns, hand sanitizer). This led to inadequate availability for many of the frontline healthcare workers. Nevertheless, equipment and supplies are useless without the essential trained personnel to operate or use them. A list of different needs of general and specialized ICUs is shown in Table 3.

Staffing: Several task forces have also addressed ICU staffing under normal and crisis conditions (32–34). In addition to the core personnel needs for an ICU, it is important to maintain safe intensivist- and nurse-to-patient ratios, as well as viable tiered staffing models emergency response protocols. In the needs assessment of nursing workforce for capacity calculations it is important to consider: a) number of beds, b) shifts covered per day, c) patient/nursing ratios, d) number of days, e) occupancy rate, f) need for additional personnel during holidays, g) acuity, and h) skillset of redeployed nurses among other criteria (29).

Patient-flow efficiency: Any interruption in the throughput of patients leads to delays in admissions, transfers and suboptimal patient care with increased costs, reduced bed availability, patient and caregiver’s dissatisfaction, need for “diversion” of patients to other hospitals, loss of revenue, and most importantly, creates unsafe conditions. The need for optimization of patient flow management is essential in the current healthcare environment. Many techniques can be used to optimize ICU patient-flow. The same queuing models used to determine ICU capacity can be used to identify the factors (24, 25, 28). However, three modifiable key factors identified by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement include: a) demand, b) capacity/demand, and c) the system (7). Reducing demand (e.g., improving end-of-life care practices, decreasing emergency department visits, decreasing surgical schedule variation, decreasing surgical and medical readmission rates), matching capacity and demand (e.g., using analytics for real-time management of the process and data-driven learning systems for hospital-wide patient-flow), and redesigning the system (e.g., improve efficiency by reducing LOS, improve throughput in the emergency department and operating room, optimize discharge process) are some examples. A list of critical care capacity metrics is shown in Table 4.

Surges: Surge capacity has been defined as “the maximal number of critically ill patients that can receive adequate critical care for as long as required, regardless of patient placement, after recruiting all critical care assets” (35, 36). Despite all the knowledge and experience from previous pandemics, the COVID-19 pandemic found us unprepared on many fronts. A survey of 4,877 ICU clinicians including physicians, nurses, advanced practice providers, respiratory therapists, pharmacists, and other ICU practitioners revealed that 64.5% were concerned with staffing, shortages of beds and supplies (37).

TABLE 2.

Methods to Determine Unit Size

| Method | Description |

|---|---|

| Hill-Burton’s formula: Since the approval of the Hill-Burton Construction Bill known as the Hospital Survey and Construction Act in the 1940s (16), the Hill-Burton formula has been very popular and used for its simplicity and practicality (22). | The formula includes the number of patient admissions annually multiplied by the average LOS in days, which is then divided by 365 d multiplied by the ideal occupancy rate, the product of this equation equals “needs." However, with the increasing complexity of modern healthcare and different systems around the world, numerous models for determining ICU bed requirements have been developed and implemented (23–28). |

| Data-Driven Framework: Modeling using historical data (23–28) | a) Number of beds (e.g., ICU and intermediate units), b) Admission rates/patient volumes, c) Patient types (e.g., medical or surgical, acute or subacute, planned or unplanned admission), d) Patient source (e.g., operating room, emergency department, ward, outside facilities), e) Timing of patient arrivals (e.g., hourly and daily distribution), f) Waiting times (e.g., time from acceptance to be in the bed), g) severity of illness (e.g., affects LOS), h) LOS (e.g., short vs long stay), and i) Utilization rate (e.g., time at optimal 85%, time under and above rate). |

TABLE 3.

Needs of General and Specialized Adult ICUsa

| ICU Type | Special Patient Population | Core Team Composition | Special Treatments | Special Needs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General ICU units (medical/surgical or mixed) | Critically ill patients requiring advanced therapies, intensive monitoring, or use of complex technology. ICU care is also provided in specialty areas as described below in addition to management of the site-specific issues as listed below. |

Multiprofessional team led by an intensivist and including advanced practice providers, nurses, nutritionists, occupational therapists, patient, pharmacists, respiratory therapists, social workers, speech therapists, pastoral care, discharge planners, vascular access team members, and others. | Subspecialty consultants contribute to patient treatment for dialysis, special procedures, ongoing chronic care (e.g., transplanted organ management, neurology, hematology/oncology, palliative care) and acute surgical interventions, among others. Mechanical ventilation, early mobilization, renal replacement therapy, vascular access, are typical. | ICU patients are at high risk of hospital-acquired events such as medication error, injury, infection, or other complications. Consistent use of protocols, safety, and quality measures are needed. Support of departments such as infection control, surgery, radiology, EEG, electrocardiogram, radiology, laboratory medicine, hospice, and others is essential. |

| Cardiovascular medicine or surgery | Provides specialized care of patients post-cardiac arrest, myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, acute heart failure, and procedures such as cardiovascular or vascular surgery, heart transplant, among others. | Specialists in cardiology, cardiac surgery, thoracic surgery, vascular surgery, transplant, and others work with the multiprofessional ICU team. Additional personnel manage sophisticated devices and treatments including perfusionists, transplant specialists, neurodiagnostic technologists, and others. | Manage invasive hemodynamic monitoring and support; intracoronary and other interventional procedures, pacemaker insertion and management, mechanical circulatory assist devices, e.g., heart pump technology, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, ventricular assist device, counterpulsation balloon, and others. | Biomedical engineers must be available for device assessment. External databases are used to measure performance and must have consistent data collection and reporting. |

| Neurologic/neurosurgical | Care of patients with ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, anoxic brain injury, traumatic brain and spinal cord injury, status epilepticus, post-neurosurgical or neurointerventional procedures, neuroinfectious diseases (meningitis, encephalitis, brain abscess), neuromuscular emergencies (myasthenia gravis, Guillain-Barre syndrome). | Neurointensivists, neurosurgeons, interventional neuroradiologists, neurologists, and others work with the multiprofessional ICU team. | Stabilize acute brain injury by minimizing secondary insults; neuroimaging and neuromonitoring; maintenance of adequate cerebral perfusion pressure; management of cerebrospinal fluid diversion (external ventricular drain, lumbar drain); control of seizures, targeted temperature management, and others. | Continuous EEG, intracranial monitoring (intracranial pressure, Pbto2, cerebral blood flow, microdialysis), advanced neuroimaging, transcranial Doppler, intensive monitoring of neurologic status in addition to general ICU monitoring. Facilitate brain death testing and manage organ donation and procurement process. |

| Burns | Care of patients with burns above 25–40% or other diffuse skin conditions such as toxic dermal necrolysis. | Burn surgeons (either plastic or general surgery), anesthesiologists, wound care specialists, pain management specialists, psychosocial experts (including psychologists, psychiatrists), and others work with the multiprofessional ICU team. | Fluid management, invasive hemodynamic monitoring, wound debridement and management, inhalation injury, physiotherapy, personalized exercise programs, and others. | Wound care, addressing psychologic effect, special social, emotional and rehabilitative intervention. |

| Trauma | Care of patient post traumatic injury (focal or diffuse) from emergency management, through surgical interventions, and wound management. | Trauma surgeons, orthopedic surgeons, anesthesiologist, and others work with the multiprofessional ICU team. | Bleeding management, wound and orthopedic interventions, and others, in addition to the needs of specific organ-system injuries (cardiovascular, neurologic, general surgery, etc.). | Blood bank support for resuscitation. Need to address the high-risk for thrombosis and wound infection to prevent those complications, in addition to those of general ICU patients. |

| Organ transplant | Care of preoperative and postoperative patients for solid-organ transplantation; patients with acute hepatorenal or hepatopulmonary failure and syndromes. | Transplant surgeons and transplant focused cardiologists, pulmonologists, infectious disease specialists among others work with the multiprofessional ICU team. | Manage organ-specific problems as listed for other specialty areas and general ICUs. Manage immunosuppressive medications and infection prevention strategies. | Monitor for organ dysfunction using procedures and devices as described in other ICUs. |

| Hemato-oncologic | Care of post-stem cell transplant patients, hematologic malignancy patients (leukemias, lymphomas, myelomas), patients undergoing experimental and/or immunotherapies. | Oncologists, hematologists, infectious diseases specialists, pheresis specialists. | Certified oncology nurses administer chemotherapy and hazardous medications via infusion ports and other invasive intravascular devices. Need to manage leukapheresis procedures, severe coagulopathies, and advanced interventional procedures. | Intense blood bank support, large amount of blood products and complex immune incompatibilities. |

EEG = electroencephalogram.

While Specialized ICUs (starting In the second row) have very specific roles, they also manage general ICU Issues. In a surge of patients, they must adapt their care to other areas of focus In addition to managing patients In their specialty realm.

TABLE 4.

Critical Care Capacity Metrics

| 1) | Number of acute care hospital beds |

| 2) | Number of ICU beds |

| 3) | Number of intermediate medical unit beds |

| 4) | Number of operating rooms |

| 5) | Number of post-anesthesia care unit beds |

| 6) | Number of functional extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (beds, devices, staffing) |

| 7) | Tele-medicine capabilities |

| 8) | Number of critical care equipment: a) Invasive ventilators b) Number of noninvasive ventilators c) Number of high-flow oxygen delivery systems d) Number of dialysis machines e) Number of IV pumps f) Other devices |

| 9) | Patient types and volumes a) Surgical (type of surgeries performed) b) Medical (type of medical services performed) c) Neurologic/neurosurgical d) Pediatric e) Gynecology/obstetrics f) Burns g) Trauma |

| 10) | Severity of illness a) Acuity b) Case mix index |

| 11) | Admission patterns a) Day/night-daily distribution |

| 12) | Admission sources a) Emergency department b) Clinics c) Other hospitals d) Other |

| 13) | Waiting times from admission to be in hospital bed |

| 14) | Discharge times and variability |

| 15) | Length of stay in the hospital |

| 16) | Length of stay in ICU |

| 17) | Hospital readmission rates |

| 18) | ICU readmission rates |

| 19) | Staffing numbers a) Physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists, other |

| 20) | Staffing ratios a) Physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists, other (e.g., number of shifts) |

| 21) | Utilization rate a) Acute care beds b) ICU beds c) Other |

Crisis level surges lead to saturation of the capability of units to cope with the influx of patients, however, well-defined surge capacity protocols have been developed to respond to such circumstances:

Disasters: Strategies to mitigate the impact of surges caused by natural and other disasters have been well described and range from maintaining larger emergency supplies of essential equipment, having emergency plans to increase surge capacity, to transferring patients out of the ICU or hospital (38). The impact in the healthcare system is frequently short-lived and causes short-term strain. In contrast, sustained events such as major hurricanes or large-scale pandemics, leading to long-term strain, are much more infrequent but require a more systematic and preemptive response (39). Pandemics can create significant global disruption as we have seen with influenza A virus subtypes H1N1 in 1918 and 2009, H2N2 in 1957, and more recently, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 starting in 2019. Recently, experts from the University of Princeton found a high probability that pandemics similar to COVID-19 may double in coming decades, with a 38% probability of experiencing such event in one’s lifetime (40).

Tele-ICU role: Telemedicine is a technological strategy used in the ICU environment and beyond to extend the reach of intensivists and other specialty services. Its utilization has been associated with improved outcomes of reduced ICU mortality, hospital LOS, and hospital mortality (41). Since 2020, the implementation of a variety of telehealth platforms have been used to overcome the sudden healthcare delivery barriers that followed the COVID-19 outbreak and its progression to pandemic status (42). The Department of Health & Human Services provided waivers, relaxed regulations, and billing practices, among others, to ensure the rapid deployment and augmentation of medical care at a time of significant risk for infection (before vaccines were available), with shortages of critical personnel (43). During the surge, capable CCOs were enabled to rapidly and effectively deploy tele-ICU across state lines and health systems (44, 45). In addition to patient care, telemedicine was used more broadly to reduce PPE waste, exposure to infected or potentially infected patients, and to facilitate participation of medical teams located in other facilities further reducing traffic in isolation areas (46).

Intermediate care units (IMCUs) role: Admissions to IMCUs (i.e., progressive, observation, stepdown) have been used to reduce ICU admissions. Similarly, ICU LOS may be reduced by discharging ICU patients to stepdown units or flexing ICU care down in place. Recently, IMCUs have been used to acutely increase ICU capacity and augment critical care services during surges especially if such geographical areas have critical care type infrastructure (38, 47). This type of unit was also used in the previous A/H1N1 pandemic to mitigate ICU workload (48) and during the latest COVID-19 pandemic preventing 61% of the ICU admissions with COVID-19 in one study (49, 50). To date, only the American Hospital Association tracks IMCU bed capacity in the United States (51).

Crisis level surge triage: Under extraordinary circumstances, when all the resources have been maximally used and optimized, difficult resource allocation decisions may be necessary even including ICU ventilator triage (31, 52–54). These decisions are very complex and require broad society support, and even then, may never be implemented as in the case of the ventilator allocation guidelines crafted by the New York State Task Force on Life and the Law (53, 54).

DISCUSSION

The rapid and adequate response to a crisis level surge requires a healthcare system well organized and able to adapt with timely flexibility and expertise. The U.S. healthcare system has the highest acute care hospital capacity in the world, not only of acute care beds but also ICU beds per capita and utilization rates below 85%; however, it is not enough to have beds (55, 56). The most recent pandemic clearly demonstrated that even the most advanced healthcare systems in the world were vulnerable, and some even collapsed when challenged. Systems failed because of multiple reasons; although some failed due to insufficient ICU beds (57). Others failed because of insufficient medical supplies (58), lack of oxygen (59), or personnel protective gear that led to double digit rates of sick healthcare providers (60). The lack of preparedness observed around the world led to calls for fair allocation of the scarce resources, as well as for global health security and universal health coverage (52, 61, 62). The unprecedented capacity strain paired with regional disparities in resource availability (e.g., hospital beds and staff) was associated with significantly increased mortality (55, 58, 63, 64).

In contrast, many CCOs were able to respond with exceptional flexibility (34, 48, 65, 66). Wang et al (65) described the response of the Mount Sinai Health System (over 3,800 beds), and Mount Sinai Hospital in particular, in New York during the pandemic peak in the first week of April 2020. The investigators noted their ability to increase surge capacity by hundreds of beds (from 1,139 to 1,453 beds), increase the number of ICUs (from seven to 11), and double the number of ICU beds by redesigning the rooms to accommodate two patients instead of one (from 104 to 235 beds). Mount Sinai implemented immediate high- and low-tech practices and protocol changes throughout the system to reduce waste of PPE and exposure of their teams as part of their daily operations and establish collaborative tier staffing care delivery models. Barbash et al (44) detailed the urgent deployment of a telemedicine program at New York Presbyterian Hospital with the support and collaboration of two other large health-care systems, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) and Mayo Clinic. This occurred at the same time that UPMC was implementing a system-level ICU pandemic surge staffing plan (65, 67). The use of tele-augmentation is shown graphically in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Tele-ICU and tele-critical care service under normal and surge conditions.

CCOs developed and implemented multiple other strategies to mitigate the strain caused by the latest pandemic. Vranas et al (66) summarized modifications by these organizations in four main areas: a) space—increasing capacity and reducing strain by canceling elective surgeries; b) staff—employing tiered-staffing models and just-in-time training for non-ICU personnel; c) stuff—ensuring adequate supply of needed equipment; and d) system—cohorting COVID-19 patients to improve workflow efficiency. They also described some of the system related challenges and recommended the involvement of frontline clinicians in the decision-making processes to optimize outcomes. A systems framework for catastrophic disaster response has also been published by Institute of Medicine, which could be of additional assistance (68).

More recently, the ALCCM taskforce provided a framework for regionalization of critical care with the goals of increasing operational efficiency and patient outcomes (4). Regionalization includes several components for an adequate response in times of crisis such as: a) prior identification of capable referral centers; b) triage of patients at a centralized access center; c) safe, timely, and effective interhospital transportation; d) metrics for ongoing monitoring of system performance; e) ICU telemedicine, and very importantly; and f) community outreach. This defragmentation of care with an architectural network of concentrated resources is characteristic of successful CCOs; 78% of North American CCOs have regionalized critical care (4). Other key elements of CCOs include their focus on patient care and safety, quality improvement, and research (2). These elements are intertwined with professional development (e.g., leadership, business skills, work/life balance), education (e.g., interprofessional collaboration and respect), innovation, and sustainability. The practical integration of all these components leads to clinician leadership (e.g., creating organizational “change capacity”), effective team development (e.g., team-based care), and change management (e.g., eliminating waste, optimizing inventory) (6). Therefore, it is not surprising that some of these CCOs were able to weather the surges more effectively. The need for further cost reduction and better quality of care, growing application of systems thinking, and expansion of digital technology capabilities in the healthcare system, among others, will accelerate the development of additional CCOs and implementation of regionalized care.

In summary, the known threats of another extreme epidemic and the many examples of less than satisfactory responses to the latest pandemic indicate the need to institute and further develop local/regional/global frameworks incorporating the elements described above. The basic framework should include the CCOs governance model, take in consideration the determinants of ICU size, equipment and infrastructure needs, staffing requirements (during normal, strain, and crisis conditions), patient-flow efficiency, response to surges (e.g., disaster readiness, tele-ICU, IMCUs, crisis level surge triage), and mitigation strategies (space, stuff, staff, system). It should also lean on regionalization strategies (e.g., identifying a priori capable referral centers), and place their focus on quality (patient care, performance improvement, research), professional development of healthcare workers, education, innovation, sustainability and other as discussed.

CONCLUSIONS

This consensus article discussing “flow-sizing” critical care services completes the survey and comprehensive description of U.S. CCOs started by the ALCCM taskforce in 2015. We identified, analyzed, and summarized the key factors to determine capacity, defined the “flow-sizing” process, and discussed the performance of select U.S. healthcare systems with CCOs during the most recent pandemic. Finally, we provide guidance for flow-sizing critical care resources in times of normal operations, surge, and strain conditions. This document highlights the need for each institution within any healthcare system to have mechanisms in place to respond to emergency surges requiring greater critical care capacity.

The creation of CCOs leads to many academic, operational, and financial advantages; additionally, the associated know-how, coordination of services, and ability to flow-size services in critical times are examples of the much-sought healthcare integration. Although we believe the CCO model in academic medical centers can be also applicable to community hospitals, we did not survey community hospitals but intend to do so in the future as we transform from a taskforce to a Knowledge and Education Group of SCCM to include members from community hospital settings. In light of the growing risks of another extreme epidemic, planning for adequate capacity to confront the next critical care crisis is an urgent priority for policy makers at all levels of our healthcare system.

Supplementary Material

KEY POINTS.

Question:

How do critical care organizations (CCOs) use ICU beds under normal operations, strain, and surge conditions?

Findings:

We identified and analyzed the key factors to determine capacity, defined the “flow-sizing” process, and discussed the performance of select U.S. healthcare systems with CCOs during the most recent pandemic. Finally, we provide guidance about the resources needed to facilitate this process.

Meanings:

This document highlights the need for each institution within any healthcare system to have mechanisms in place to respond to in times of strain or emergency surges requiring greater critical care capacity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The article was reviewed by Mary Ann Oler, MPA, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

APPENDIX

Academic Leaders in the Critical Care Medicine (ALCCM) Task Force Members: Co-Chairs: Stephen M. Pastores, MD, MACP, FCCP, FCCM (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY); John M. Oropello, MD, FACP, FCCP, FCCM (Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York, NY). ALCCM Task Force Members: Derek C. Angus, MD, MCCM (University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA); Neeraj Badjatia, MD (Maryland Critical Care Network, Baltimore, MD); Andrew Baker, MD (St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, CA); Gregory Beilman, MD, FCCM (University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN); Daniel R. Brown, MD, PhD, FCCM (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN); Timothy S. Buchman, MD, FCCP, MCCM (Emory Critical Care, Atlanta, GA); John W. Christman, MD (The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, OH); J. Perren Cobb, MD, FCCM (University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA); Craig M. Coopersmith, MD, FACS, MCCM (Emory Critical Care, Atlanta, GA); Rhonda D’Agostino, ACNP, FCCM (Orange Regional Medical Center, New York, NY); Jose Diaz-Gomez, MD, FCCM (Texas Heart Institute, Baylor St. Luke’s Medical Center, Houston, TX); Christopher Doig, MD (University of Calgary, Calgary, CA); J. Christopher Farmer, MD, MCCM (Scottsdale, AZ); Samuel M. Galvagno Jr, DO, PhD, MS, FCCM (Maryland Critical Care Network, Baltimore, MD); James Gasperino, MD (The Brooklyn Hospital Center, Brooklyn, NY); Sara R. Gregg, MHA (Emory Critical Care, Atlanta, GA); Neil A. Halpern, MD, FACP, FCCP, MCCM (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY); Daniel L. Herr, MD, FCCM (University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD); Judith Jacobi, PharmD, MCCM (Lebanon, IN); Eric Kaiser, MD (Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH); Roozehra A. Khan, DO, FCCP (Los Angeles, CA); April N. Kapu, ACNP-BC (Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN); Hassan Khouli, MD (Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH); Roopa Kohli-Seth, MD (Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York, NY); Peter Laussen, MD (The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON, Canada); Sharon Leung, MD (Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY); Craig M. Lilly, MD, FCCP, FCCM (University of Massachusetts, Worcester, MA); Jon Marinaro, MD, FCCM (University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM); Henry Masur, MD, MCCM (National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, Bethesda, MD); Gargi Mehta, PA-C, MSHS (Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY); Sheila Melander, PhD, ACNP, FCCM (University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY); Jason Moore, MD (University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA); Joseph L. Nates, MD, MBA, CMQ, MCCM (MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX); Marc Popovich, MD, FCCM (University Hospitals, Cleveland Medical Center, Cleveland, OH); Kristen Price, MD (MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX); Nitin Puri, MD, FCCM (Cooper University Hospital, Camden, NJ); Marjan Rahmanian, MD (Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY); and Curtis Sessler, MD, FCCP, FCCM (Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA).

Footnotes

Dr. Halpern received funding from Werfen and Airstrip Technologies. Dr. Jacobi received funding from La Jolla Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer Hospital Products Division, AcelRx, Society of Critical Care Medicine LEAD and Glycemic Guidelines Co-Chair, BD Voices of Vascular Educational Advisor, Visante, Infusion Nurses Society, and Postgraduate Healthcare Education. Dr. Pastores’ institution received funding from Biomerieux, RevImmune, and Eisai/Global Coalition for Adaptive Research; he received funding from McGraw Hill. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

All authors for the Academic Leaders in Critical Care Task Force of the Society of Critical Care Medicine where all authors accept authorship responsibilities.

The Academic Leaders in the Critical Care Medicine (ALCCM) Task Force Members are listed in the Appendix.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pastores SM, Halpern NA, Oropello JM, et al. : Critical care organizations in academic medical centers in North America. Crit Care Med 2015; 43:2239–2244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moore JE, Oropello JM, Stoltzfus D, et al. ; Academic Leaders in Critical Care Medicine (ALCCM) Task Force of the Society of the Critical Care Medicine: Critical care organizations: Building and integrating academic programs. Crit Care Med 2018; 46:e334–e341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lilly CM, Oropello JM, Pastores SM, et al. ; Academic Leaders in Critical Care Medicine Task Force of the Society of Critical Care Medicine: Workforce, workload, and burnout in critical care organizations: Survey results and research agenda. Crit Care Med 2020; 48:1565–1571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leung S, Pastores SM, Oropello JM, et al. ; Academic Leaders in Critical Care Medicine Task Force of the Society of Critical Care Medicine: Regionalization of critical care in the United States: Current state and proposed framework from the Academic Leaders in Critical Care Medicine Task Force of the Society of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med 2022; 50:37–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pastores SM, Kvetan V, Coopersmith CM, et al. ; Academic Leaders in Critical Care Medicine (ALCCM) Task Force of the Society of the Critical Care Medicine: Workforce, workload, and burnout among intensivists and advanced practice providers: A narrative review. Crit Care Med 2019; 47:550–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leung S, Gregg SR, Coopersmith CM, et al. ; Academic Leaders in Critical Care Medicine Task Force of the Society of the Critical Care Medicine: Critical care organizations: Business of critical care and value/performance building. Crit Care Med 2018; 46:1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rutherford PA, Anderson A, Kotagal UR, et al. : Achieving Hospital-Wide Patient Flow. Second Edition. Boston, MA, Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Douin DJ, Ward MJ, Lindsell CF, et al. : ICU bed utilization during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic in a multistate analysis-March to June 2020. Crit Care Explor 2021; 3:e0361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cardoso LT, Grion CM, Matsuo T, et al. : Impact of delayed admission to intensive care units on mortality of critically ill patients: A cohort study. Crit Care 2011; 15:R28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chalfin DB, Trzeciak S, Likourezos A, et al. ; DELAY-ED study group: Impact of delayed transfer of critically ill patients from the emergency department to the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2007; 35:1477–1483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cobre AF, Böger B, Vilhena RO, et al. : A multivariate analysis of risk factors associated with death by Covid-19 in the USA, Italy, Spain, and Germany. Z Gesundh Wiss 2020; 30:1189–1195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ravaghi H, Alidoost S, Mannion R, et al. : Models and methods for determining the optimal number of beds in hospitals and regions: A systematic scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res 2020; 20:186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halpern SD: ICU capacity strain and the quality and allocation of critical care. Curr Opin Crit Care 2011; 17:648–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rewa OG, Stelfox HT, Ingolfsson A, et al. : Indicators of intensive care unit capacity strain: A systematic review. Crit Care 2018; 22:86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bagshaw SM, Opgenorth D, Potestio M, et al. : Healthcare provider perceptions of causes and consequences of ICU capacity strain in a large publicly funded integrated health region: A qualitative study. Crit Care Med 2017; 45:e347–e356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The Hospital Survey and Construction Act. JAMA 1946; 132:148–149 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phillip PJ, Mullner R, Andes S: Toward a better understanding of hospital occupancy rates. Health Care Financ Rev 1984; 5:53–61 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferrier GD, Leleu H, Valdmanis VG: Hospital capacity in large urban areas: Is there enough in times of need? J Prod Anal 2009; 32:103–117 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nates JL: Combined external and internal hospital disaster: Impact and response in a Houston trauma center intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2004; 32:686–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Green LV: How many hospital beds? Inquiry 2002; 39:400–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Penchansky R, Thomas J: The concept of access: Definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction. Med Care 1981; 19:127–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wild C, Narath M: Evaluating and planning ICUs: Methods and approaches to differentiate between need and demand. Health Policy 2005; 71:289–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mathews KS, Long EF: A conceptual framework for improving critical care patient flow and bed use. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2015; 12:886–894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Costa AX, Ridley SA, Shahani AK, et al. : Mathematical modelling and simulation for planning critical care capacity. Anaesthesia 2003; 58:320–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu Z, Hen BH, Teow KL: Estimating ICU bed capacity using discrete event simulation. Int J Health Care Qual Assur 2012; 25:134–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nguyen JM, Six P, Parisot R, et al. : A universal method for determining intensive care unit bed requirements. Intensive Care Med 2003; 29:849–852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bauer J, Klingelhöfer D, Maier W, et al. : Prediction of hospital visits for the general inpatient care using floating catchment area methods: A reconceptualization of spatial accessibility. Int J Health Geogr 2020; 19:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams E, Szakmany T, Spernaes I, et al. : Discrete-event simulation modeling of critical care flow: New hospital, old challenges. Crit Care Explor 2020; 2:e0174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferdinande P: Recommendations on minimal requirements for intensive care departments. Members of the Task Force of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med 1997; 23:226–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thompson D, Hamilton DK, Cadenhead C, et al. : Guidelines for intensive care unit design. Crit Care Med 2012; 40:1586–1600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ranney ML, Griffeth V, Jha AK: Critical supply shortages – the need for ventilators and personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med 2020; 382:e41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ward NS, Afessa B, Kleinpell R, et al. ; Members of Society of Critical Care Medicine Taskforce on ICU Staffing: Intensivist/patient ratios in closed ICUs: A statement from the Society of Critical Care Medicine Taskforce on ICU Staffing. Crit Care Med 2013; 41:638–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kleinpell R, Ward NS, Kelso LA, et al. : Provider to patient ratios for nurse practitioners and physician assistants in critical care units. Am J Crit Care 2015; 24:e16–e21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harris G, Baldisseri M, Reynolds B, et al. : Design for implementation of a system-level ICU pandemic surge staffing plan. Crit Care Explor 2020; 2:e0136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hick JL, Einav S, Hanfling D, et al. ; Task Force for Mass Critical Care: Surge capacity principles. Care of the critically ill and injured during pandemics and disasters: Chest consensus statement. Chest 2014; 146:e1S–e16S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Einav S, Hick JL, Hanfling D, et al. ; Task Force for Mass Critical Care: Surge capacity logistics. Care of the critically ill and injured during pandemics and disasters: Chest consensus statement. Chest 2014; 146:e17S–e43S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Society of Critical Care Medicine: ICU Readiness Assessment: We Are Not Prepared for COVID-19. 2020. Available at: https://www.sccm.org/getattachment/Blog/April-2020/ICU-Readiness-Assessment-We-Are-Not-Prepared-for/COVID-19-Readiness-Assessment-Survey-SCCM.pdf?lang=en-US. Accessed February 2, 2022 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nates JL, Nunnally M, Kleinpell R, et al. : ICU admission, discharge, and triage guidelines: A framework to enhance clinical operations, development of institutional policies, and further research. Crit Care Med 2016; 44:1553–1602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sprung CL, Zimmerman JL, Christian MD, et al. ; European Society of Intensive Care Medicine Task Force for Intensive Care Unit Triage during an Influenza Epidemic or Mass Disaster: Recommendations for intensive care unit and hospital preparations for an influenza epidemic or mass disaster: Summary report of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine’s Task Force for intensive care unit triage during an influenza epidemic or mass disaster. Intensive Care Med 2010; 36:428–443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marani M, Katul GG, Pan WK, et al. : Intensity and frequency of extreme novel epidemics. PNAS 2021; 118:e2105482118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilcox ME, Adhikari NK: The effect of telemedicine in critically ill patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care 2012; 16:R127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Using Telehealth to Expand Access to Essential Health Services During the COVID-19 Pandemic. 2020. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/telehealth.html. Accessed February 2, 2022

- 43.U.S. Department of Health & Human Services: Telehealth: Delivering Care Safely During COVID-19. 2020. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/telehealth.html. Accessed February 2, 2022 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barbash IJ, Sackrowitz RE, Gajic O, et al. : Rapidly deploying critical care telemedicine across states and health systems during the Covid-19 pandemic. N Eng J Med Catalyst 2020; doi: 10.1056/CAT.20.0301. Available at: https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0301. Accessed June 5, 2023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Igra A, McGuire H, Naldrett I, et al. : Rapid deployment of virtual ICU support during the COVID-19 pandemic. Future Healthc J 2020; 7:181–184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vilendrer S, Patel B, Chadwick W, et al. : Rapid deployment of inpatient telemedicine in response to COVID-19 across three health systems. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2020; 27:1102–1109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Naeem N, Montenegro H: Beyond the intensive care unit: A review of interventions aimed at anticipating and preventing in-hospital cardiopulmonary arrest. Resuscitation 2005; 67:13–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carbonara S, Bruno G, Ciaula GD, et al. : Limiting severe outcomes and impact on intensive care units of moderate-intermediate 2009 pandemic influenza: Role of infectious diseases units. PLoS One 2012; 7:e42940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grosgurin O, Leidi A, Farhoumand PD, et al. : Role of intermediate care unit admission and noninvasive respiratory support during the COVID-19 pandemic: A retrospective cohort study. Respiration 2021; 100:786–793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Agnoletti V, Russo E, Circelli A, et al. : From intensive care to step-down units: Managing patients throughput in response to COVID-19. Int J Qual Health Care 2021; 33:mzaa091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Halpern NA, Tan KS: United States Resource Availability for COVID-19. Critical Connections Blog. 2020. Available at: https://www.sccm.org/Blog/March-2020/United-States-Resource-Availability-for-COVID-19. Accessed February 02, 2022 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sprung CL, Joynt GM, Christian MD, et al. : Adult ICU triage during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: Who will live and who will die? Recommendations to improve survival. Crit Care Med 2020; 48:1196–1202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.New York State Department of Health: Ventilator Allocation Guidelines. 2015. Available at: https://www.health.ny.gov/regulations/task_force/reports_publications/docs/ventilator_guidelines.pdf. Accessed May 31, 2023

- 54.Gutmann Koch V, Han SA: COVID in NYC: What New York did, and should have done. Am J Bioeth 2020; 20:153–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sen-Crowe B, Sutherland M, McKenney M, et al. : A closer look into global hospital beds capacity and resource shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Surg Res 2021; 260:56–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development: Assessing Private Practice in Public Hospitals. 2018. Available at: https://assets.gov.ie/26530/88ebd7ddd9e74b51ac5227a38927d5f9.pdf. Accessed September 10, 2021

- 57.Horowitz J: Italy’s Health Care System Groans Under Coronavirus – A Warning to the World. The New York Times. 2020. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/12/world/europe/12italy-coronavirus-health-care.html. Accessed February 4, 2022 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ji Y, Ma Z, Peppelenbosch MP, et al. : Potential association between COVID-19 mortality and health-care resource availability. Lancet Glob Health 2020; 8:e480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moole J: A Nightmare on Repeat – India Is Running Out of Oxygen Again. 2021. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-56841381. Accessed February 4, 2022 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nugent C: “It’s Like Being a War Medic.” A Madrid Doctor Speaks Out About Grave Shortages in Protective Gear. TIME. 2020. Available at: https://time.com/5813848/spain-coronavirus-outbreak-doctor/. Accessed February 4, 2022 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Emanuel EJ, Persad G, Upshur R, et al. : Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020; 382:2049–2055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lal A, Erondu NA, Heymann DL, et al. : Fragmented health systems in COVID-19: Rectifying the misalignment between global health security and universal health coverage. Lancet 2021; 397:61–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xie L, Yang H, Zheng X, et al. : Medical resources and coronavirus disease (COVID-19) mortality rate: Evidence and implications from Hubei province in China. PLoS One 2021; 16:e0244867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wilcox ME, Rowan KM, Harrison DA, et al. : Does unprecedented ICU capacity strain, as experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic impact patient outcome? Crit Care Med 2022; 50:e548–e556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang J, Leibner E, Hyman JB, et al. ; Mount Sinai Anesthesiology and Critical Care COVID19 Writing Group: The Mount Sinai Hospital Institute for critical care medicine response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Acute Crit Care 2021; 36:201–207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vranas KC, Golden SE, Mathews KS, et al. : The influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on ICU organization, care processes, and frontline clinician experiences: A qualitative study. Chest 2021; 160:1714–1728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chandra S, Hertz C, Khurana H, et al. : Collaboration between tele-ICU programs has the potential to rapidly increase the availability of critical care physicians-our experience was during coronavirus disease 2019 nomenclature. Crit Care Explor 2021; 3:e0363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Institute of Medicine: Committee on Guidance for Establishing Standards of Care for Use in Disaster Situations: Crisis Standards of Care: A Systems Framework for Catastrophic Disaster Response. 2012. Available at: https://www.amr.net/solutions/federal-disaster-response-team/references-and-resources/crisis-standards-of-care-2012-iom-w-core-function.pdf. Accessed February 12, 2023 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.