Abstract

Euphorbia, one of the largest genera of flowering plants, is well-known for containing many biofuel crops. Euphorbia tirucalli, an evergreen succulent mainly native to the Africa continent but cultivated worldwide, is a promising petroleum plant with high tolerance to drought and salt stress. However, the exploration of such an important plant resource is severely hampered by the lack of a reference genome. Here, we present the chromosome-level genome assembly of E. tirucalli using PacBio HiFi sequencing and Hi-C technology. Its genome size was approximately 745.62 Mb, with a contig N50 of 74.16 Mb. A total of 743.63 Mb (99.73%) of the assembled sequences were anchored to 10 chromosomes with a complete BUSCO score of 97.80%. Genome annotation revealed 26,304 protein-coding genes, and 76.37% of the genome was identified as repeat elements. The high-quality genome provides valuable genetic resources that would be useful for unraveling the genetic mechanisms of biofuel synthesis and evolutionary adaptation of E. tirucalli.

Subject terms: Genome evolution, Biogas

Background & Summary

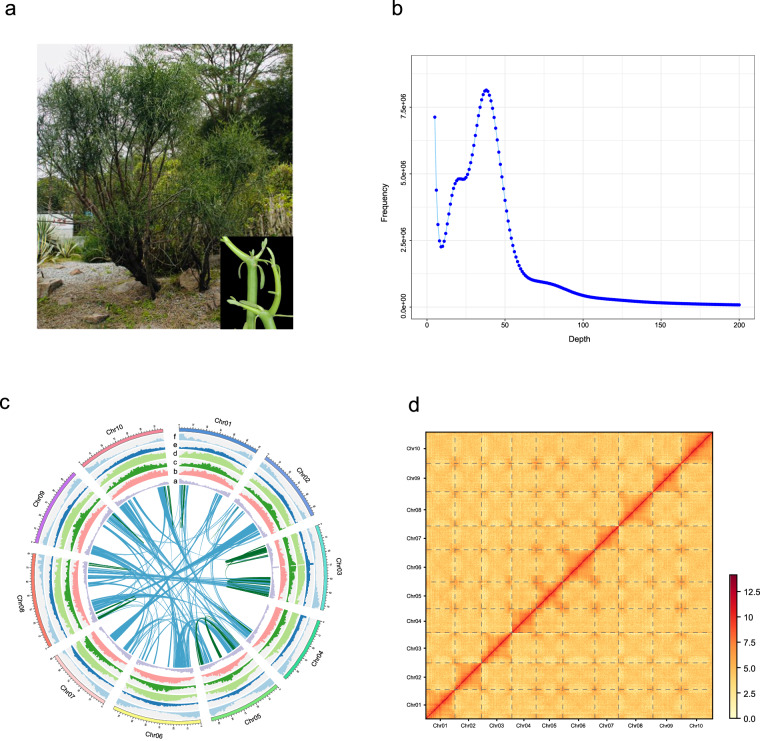

Euphorbia, belonging to the family Euphorbiaceae, comprises about 2000 species and is one of the largest flowering plant genera in the world1. Many fuel plants have been reported in this genus, providing biomass for the production of biocrude, bioethanol and other bioenergy resources2–5. Euphorbia tirucalli (2n = 2x = 20)6, commonly referred to as milk bush, pencil cactus, pencil tree, or naked lady, is an evergreen shrub or small tree with typically succulent branched stems and small non-succulent leaves (Fig. 1a). It is naturally distributed in Indochina, South Africa, East Africa and Madagascar, and has been extensively cultivated as horticultural plant in other tropical or subtropical areas7. As one of the representative oil plants, E. tirucalli has long been considered a promising substitute for traditional energy sources. It exudes a milky latex from the wounded shoots or leaf stems3,8. Recent studies demonstrated that the compounds in the latex exhibit high petrochemical properties5,9,10. In addition, this species has important medicinal value, with its latex being traditionally used for the treatment of cancer, asthma, arthritis, rheumatism and so on11–14.

Fig. 1.

Overview of Euphorbia tirucalli genome assembly and features. (a) The picture of the sequenced E. tirucalli from South China National Botanical Garden (accession number: IBSC0312991). The inset map shows its succulent branched stems and small non-succulent leaves. (b) K-mer (17-mer) frequency distribution curve. (c) Distribution of genomic features of E. tirucalli. Tracks ‘a–f’ represent tandem repeat density, LTR Gypsy density, LTR Copia density, TE density, GC content, and gene density, respectively. (d) Hi-C interaction heat map for E. tirucalli.

Euphorbia tirucalli has high salinity and drought tolerance, which enables it to grow under a wide range of adverse conditions without occupying any arable land. Different genotypes exhibit distinct evolutionary adaptation to environmental stress15. In particular, the special photosynthetic system in E. tirucalli, i.e., the combination of C3 metabolism in non-succulent leaves and the Crassulacean Acid Metabolism (CAM) pathway in succulent stems, could efficiently maximize biomass accumulation7,16,17. Specifically, C3 promotes growth under favorable conditions, while non-succulent C3 leaves die quickly and CAM plays a critical role under drought stress, which could prevent damage from water limitation and ensure photosynthetic integrity16.

Due to the global energy crisis with the conventional fossil fuels and the associated environmental degradation18–21, E. tirucalli has received increasing attention in recent years, thanks to its fascinating petrochemical values and high tolerance to extreme habitats4,5,22,23. However, the utilization of such an important plant resource is severely hampered by the unavailability of genomic data. Therefore, a high-quality assembled genome of E. tirucalli is urgently required to uncover the genetic basis of both biodiesel production and stress resistance.

In this study, we performed a de novo chromosome-level genome assembly and annotation of E. tirucalli using PacBio HiFi sequencing and high-throughput chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C) technology. The assembled genome size of E. tirucalli was 745.62 Mb, with a contig N50 of 74.16 Mb. A total of 743.63 Mb (99.73%) of the assembled sequences were anchored to 10 chromosomes with a complete BUSCO score of 97.80%. The genome annotation identified 26,304 protein-coding genes. The high quality genome provides valuable genetic resources for further research on the genetic mechanisms underlying biofuel synthesis and adaptation to harsh conditions in E. tirucalli.

Methods

Sampling and sequencing

Fresh leaves of E. tirucalli were collected for whole genome sequencing from a healthy tree planted in the South China National Botanical Garden (accession number: IBSC0312991) (Fig. 1a). Additionally, tender leaves, mature leaves, young succulent stems, old stems, flowers, and roots were collected for transcriptome sequencing. All samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

Total genomic DNA was extracted using a cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method24. DNA quantity and quality were determined using a Qubit 4.0 fluorometer. Short read sequencing libraries with ~350 bp insert size were constructed and sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform to generate 150 bp read pairs. For PacBio SMRT sequencing, a 15 kb DNA PacBio HiFi library was generated using the SMRTbell Express Template Preparation Kit 2.0. The library was then sequenced on the PacBio Sequel II platform, yielding 41.54 Gb of HiFi data with 53.96 × coverage. The Hi-C libraries were prepared by chromatin crosslinking, restricted enzyme (MboI) digestion, end filling and biotinylation tagging, DNA purification and shearing. All of the prepared DNA fragments were processed into paired-end sequencing libraries. Finally, a total of ~100 Gb of 150 bp paired-end Hi-C reads were obtained from the Illumina platform. For transcriptome sequencing, the RNA-seq libraries were constructed and then sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform with 150 bp paired-end reads, generating about 18.8 Gb of RNA-seq reads.

Genome survey for genome size estimation

A total of 35 Gb of clean data from the Illumina platform was used for the genome survey. Genome size, heterozygosity and repeat content were estimated from the k-mer frequency distribution using GCE25. The 17-mer analyses yielded an estimated genome size of 789.98 Mb, with heterozygosity of 0.80% and repeat content of 74.67% (Fig. 1b).

De novo genome assembly

The PacBio HiFi reads were initially assembled into contigs using hifiasm v0.16.1-r37526 with default parameters. This analysis resulted in an assembly of 745.62 Mb and a N50 length of 74.16 Mb (Table 1). The size of the assembled genome is slightly smaller than our estimates (~760 Mb) by flow cytometry using Oryza sativa ssp. japonica (1 C = 0.43–0.45 pg) as a reference standard (Fig. S1). The completeness of the genome assembly was assessed using Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologues (BUSCO v5.4.3)27 with the embryophyta_odb10, which generated 97.8% of the Plantae BUSCO genes (Table 1). The accuracy of the draft assembly was further evaluated by mapping short reads to the genome assembly using the BWA-MEM v0.7.17-r118828, which yielded a mapping rate and genome coverage of 99.88% and 99.75%, respectively (Table 1). For pseudochromosome construction, Hi-C reads were aligned to the contig-level assembly using Juicer v1.629 with default parameters. We then used the 3D-DNA v201008 pipeline30 to correct mis-joins, anchor, order, and orient the assembled contigs. Manual inspections and adjustments of the draft assembly were performed using Juicebox v1.11.0831. Finally, approximately 743.63 Mb of scaffold was anchored to 10 pseudochromosomes, accounting for 99.73% of the assembled genome size (Fig. 1c,d). To evaluate the continuity of the genome assembly, the long terminal repeat retrotransposons assembly index (LAI), a reference-free genome metric for assessing the assembly of repeat sequences32 was calculated. The LAI value of the genome assembly was 19.05, which was close to the quality standard of a gold genome (LAI > 20) proposed by Ou et al.32. Collectively, these results validated the high completeness and reliability of our E. tirucalli genome assembly.

Table 1.

Statistics of the Euphorbia tirucalli genome assembly and annotation.

| Genome assembly | |

|---|---|

| Total length of assembly (Mb) | 745.62 |

| Number of contigs | 123 |

| Contig N50 (Mb) | 74.16 |

| Pseudochromosome number | 10 |

| Scaffold N50 (Mb) | 75.09 |

| Number of gaps | 43 |

| Anchor rate (%) | 99.73 |

| Mapped Illumina reads (%) | 99.88 |

| BUSCO (%) | 97.80 |

| GC content (%) | 37.20 |

| LAI | 19.05 |

| QV | 67.58 |

| K-mer completeness | 87.71 |

| Genome annotation | |

| Total length of repeats (Mb) | 569.43 |

| Repeats percentage of assembly (%) | 76.37 |

| Number of protein-coding genes | 28,840 |

| Average gene length (bp) | 4,191.84 |

| Average intron length (bp) | 684.30 |

| Average exon length (bp) | 290.86 |

| Functional annotation | |

| SwissProt | 21,030 (72.92%) |

| Nr | 26,252 (91.03%) |

| InterPro | 23,340 (80.93%) |

| Pfam | 21,186 (73.46%) |

| eggNOG | 23,838 (82.66%) |

| Total | 26,304 (91.21%) |

Repeat annotation

Tandem repeats were identified by ab initio prediction using TRF v4.0933. We used both de novo and homology predictions to annotate transposable elements (TEs) throughout the genome. For the homology-based strategy, RepeatMasker34 and RepeatProteinMask34 were used to extract the known repeat sequences. For de novo prediction, long terminal repeat (LTR) elements were first identified with LTR_FINDER v1.0.635, LTRharvest v1.5.1036 and LTR_retriever37. Then, MITE-hunter38 and RepeatModeler39 were used for de novo repeat discovery. The MITE and consensus repeat libraries generated by RepeatModeler were combined and subjected to RepeatMasker for final repeat identification. Overall, 569.43 Mb (76.37%) of the assembly was masked as repeats. Of these, 75.70% were TEs, including long terminal repeat retrotransposons (LTR-RTs) (61.11%), non-LTR-RTs (1.10%), and DNA transposons (6.56%) (Fig. 1c; Table 2).

Table 2.

Statistics of repeat sequences in the Euphorbia tirucalli genome.

| Class | Length (bp) | Percentage in genome (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Class I: Retrotransposon | 463,901,118 | 62.21 |

| LTR Retrotransposon | 455,692,982 | 61.11 |

| Copia | 208,117,659 | 27.91 |

| Gypsy | 242,670,614 | 32.55 |

| Others | 4,904,709 | 0.65 |

| Non- LTR Retrotransposon | 8,208,136 | 1.10 |

| LINE | 8,208,136 | 1.10 |

| Class II: DNA Transposon | 48,899,750 | 6.56 |

| CMC-EnSpm | 1,271,052 | 0.17 |

| MITE | 33,414,101 | 4.48 |

| MULE-MuDR | 6,018,597 | 0.81 |

| PIF-Harbinger | 1,683,188 | 0.23 |

| TcMar-Pogo | 159,571 | 0.02 |

| hAT-Ac | 1,721,574 | 0.23 |

| Helitron | 2,572,374 | 0.35 |

| Unclassified | 51,602,006 | 6.92 |

| Total TE | 564,402,874 | 75.70 |

| Tandem repeat | 5,027,446 | 0.67 |

| Total repetitive sequences | 569,430,320 | 76.37 |

Gene prediction and functional annotation

Gene prediction was performed using a combined strategy of homology-based, ab initio, and RNA-Seq-assisted predictions. In detail, Trinity v2.15.040 was used to de novo assemble the transcriptome for RNA-Seq-assisted prediction. Hisat2 v2.2.141 was utilized to map RNA-seq reads to the genome, and Samtools v1.942 was used to generate BAM file. Then Trinity and StringTie43 were utilized to assemble the genome-guided transcriptomes. The de novo and genome-guided transcriptome assemblies were merged, generating transcript evidence using PASA44. SNAP45, GeneID46, GlimmerHMM47, GeneMark-ET48 and AUGUSTUS49 were used for ab initio prediction with RNA-Seq-based predicted genes as training data. Homologies from five Euphorbiaceae species (E. lathyris, E. peplus, Ricinus communis, Hevea brasiliensis, and Manihot esculenta) and Arabidopsis thaliana were used as protein evidence for predicted gene sets using GeMoMa50. Finally, the results from the above three approaches were integrated using EVidenceModeler51 and further polished using PASA44. A total of 28,840 protein-coding genes were successfully predicted for E. tirucalli, with the average gene, intron and exons lengths of 4191.84 bp, 684.30 bp and 290.86 bp, respectively (Table 1).

For the functional annotation of protein-coding genes, a BLASTP (E-value ≤ 1e−5) search with the best match parameters was performed against publicly available protein databases of SwissProt and NR. Motifs and domains were annotated using InterProScan52 by searching against InterPro and Pfam. Gene ontology (GO) terms of the annotated peptide sequences were obtained using eggNOG-mapper v2.1.553. Finally, 26,304 protein-coding genes were functionally annotated, representing 91.21% of the total predicted genes (Table 1).

Data Records

The raw sequence data (Illumina, PacBio, Hi-C) have been uploaded to NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database with accession number SRR2788584254, SRR2788583455, and SRR2788583556, respectively, under the BioProject accession number PRJNA1070402. The RNA-seq data for different tissues are also available under PRJNA1070402 with accession numbers SRR2788583657, SRR2788583758, SRR2788583859, SRR2788583960, SRR2788584061, SRR2788584162. The final chromosome assembly has been deposited in NCBI GenBank with accession number JAZDXJ00000000063. The genome annotation file has been deposited in the Figshare database64.

Technical Validation

We assessed the quality of the genome assembly in the following aspects: (1) Genome completeness was assessed by BUSCO v5.4.34. The results indicated that 97.8% complete BUSCO genes were identified in the final assembly, of which 95.6% were single-copy, 2.2% were duplicated, and 0.4% were fragmented. (2) Mapping short reads to the genome assembly, which revealed a mapping rate and genome coverage of 99.88% and 99.75%, respectively. (3) The LTR Assembly Index (LAI) of the genome assembly is 19.05, which is close to the quality of a gold genome according to the classification system32. (4) Quality value (QV) and k-mer completeness were estimated using Merqury v1.365, resulting in a QV of 67.58 and completeness of 87.71%. These results indicate that the E. tirucalli genome assembly is of high quality.

Supplementary information

Fig. S1. Fluorescence histograms of flow cytometry for Euphorbia tirucalli.

Acknowledgements

We thank Associate Editor and anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. This work was supported by Guangdong Province Basic Research Flagship Project (2023B0303050001), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31970360), Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2022A1515011293), and Youth Innovation Promotion Association CAS (2021348).

Author contributions

J.W. and M.K. conceived and designed the study. J.W. and X.S. prepared the samples. Z.W., C.F. and J.X. analyzed the data. J.W. and W.Z. wrote the manuscript. M.K. revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Code availability

All software and pipelines used in this study were implemented according to the manuals and protocols provided by the software developers. Versions of the software have been described in Methods. No custom code was used in this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41597-024-03503-w.

References

- 1.Bruyns PV, Mapaya RJ, Hedderson TJJT. A new subgeneric classification for Euphorbia (Euphorbiaceae) in southern Africa based on ITS and psbA-trnH sequence data. Taxon. 2006;55:397–420. doi: 10.2307/25065587. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duke, J. Euphorbia tirucalli L., handbook of energy crops. Purdue University centre for new crops and plant products (1983).

- 3.Loke, J., Mesa, L. A. & Franken, J. Y. Euphorbia tirucalli biology manual: Feedstock production, bioenergy conversion, application, economics Version 2. FACT. (2011).

- 4.Hastilestari BR, et al. Euphorbia tirucalli L.–Comprehensive characterization of a drought tolerant plant with a potential as biofuel source. PLoS one. 2013;8:e63501. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duy Khang NV, Nhi Nguyen T, Quan TL. Potential biofuel exploitation from two common Vietnamese Euphorbia plants (Euphorbiaceae) Biofuel. Bioprod. Biorefin. 2023;17:1315–1327. doi: 10.1002/bbb.2472. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Z, Huang J, Li L. Polyploid induction in Euphorbia tirucalli L. with Colchicine. J Southwest. 2007;29:106–110. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Damme, P. L. Euphorbia tirucalli for high biomass production. In Combating desertification with plants. (Boston, MA: Springer US, 2001).

- 8.Saigo, R. H. & Saigo, B. W. Botany, principles and applications. (Pren-tice-Hall, Englewood CliVs, 1983).

- 9.Calvin M. Petroleum plantations for fuel and materials. Bioscience. 1979;29:533–538. doi: 10.2307/1307721. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calvin M. Fuel oils from euphorbs and other plants. Bot. J. Linnean Soc. 1987;94:97–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8339.1987.tb01040.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Damme P. Het traditioneel gebruik van Euphorbia tirucalli. Afrika Focus. 1989;5:176–193. doi: 10.1163/2031356X-0050304006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aylward, J. H. & Parsons, P. G. Treatment of prostate cancer. (Peplin Research May, US, 2008).

- 13.Kumar, A. Some potential plants for medicine from India. (Ayurvedic medicines, University of Rajasthan, Rajasthan, 1999).

- 14.Schmelzer, G. H. & Gurib-Fakim, A. Medicinal plants. (Plant Resources of Tropical Africa, 2008).

- 15.Abuelsoud, W., Hirschmann, F. & Papenbrock, J. Sulfur metabolism and drought stress tolerance in plants. Vol. 1: Physiology and Biochemistry 227–249 (2016).

- 16.Cushman JC, Borland A. Induction of Crassulacean acid metabolism by water limitation. Plant Cell Environ. 2002;25:295–310. doi: 10.1046/j.0016-8025.2001.00760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janssens MJ, Keutgen N, Pohlan J. The role of bio-productivity on bio-energy yields. J. Agr. Rural Dev. Trop. 2009;110:41–48. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zika M, Erb KH. The global loss of net primary production resulting from human-induced soil degradation in drylands. Ecol. Econ. 2009;69:310–318. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2009.06.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang R, et al. Production and selected fuel properties of biodiesel from promising non-edible oils: Euphorbia lathyris L., Sapium sebiferum L. and Jatropha curcas L. Bioresour. Technol. 2011;102:1194–1199. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.09.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dai A. Increasing drought under global warming in observations and models. Nat. Clim. Change. 2013;3:52–58. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1633. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taparia T, Mvss M, Mehrotra R, Shukla P, Mehrotra S. Developments and challenges in biodiesel production from microalgae: A review. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2016;63:715–726. doi: 10.1002/bab.1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Demirbas A. Competitive liquid biofuels from biomass. Appl. Energy. 2011;88:17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2010.07.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharma R, Wungrampha S, Singh V, Pareek A, Sharma MK. Halophytes as bioenergy crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7:1372. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winnepenninckx B, Backeljau T, De Wachter R. Extraction of high molecular weight DNA from molluscs. Trends Genet. 1993;9:407. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(93)90102-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu, B. et al. Estimation of genomic characteristics by analyzing k-mer frequency in de novo genome projects. arXiv.org, arXiv: 1308.2012 (2013).

- 26.Cheng H, Concepcion GT, Feng X, Zhang H, Li H. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nat. Methods. 2021;18:170–175. doi: 10.1038/s41592-020-01056-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simão FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM. BUSCO: Assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3210–3212. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics25, 1754-1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Durand NC, et al. Juicer provides a one-click system for analyzing loop-resolution Hi-C experiments. Cell Syst. 2016;3:95–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dudchenko O, et al. De novo assembly of the Aedes aegypti genome using Hi-C yields chromosome-length scaffolds. Science. 2017;356:92–95. doi: 10.1126/science.aal3327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Durand NC, et al. Juicebox provides a visualization system for Hi-C contact maps with unlimited zoom. Cell Syst. 2016;3:99–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2015.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ou S, Chen J, Jiang N. Assessing genome assembly quality using the LTR Assembly Index (LAI) Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:e126–e126. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:573–580. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen N. Using Repeat Masker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics. 2004;5:4.10.11–14.10.14. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0410s05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu Z, Wang H. LTR_FINDER: an efficient tool for the prediction of full-length LTR retrotransposons. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W265–W268. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ellinghaus D, Kurtz S, Willhoeft U. LTRharvest, an efficient and flexible software for de novo detection of LTR retrotransposons. Bmc. Bioinformatics. 2008;9:1–114. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ou S, Jiang N. LTR_retriever: A highly accurate and sensitive program for identification of long terminal repeat retrotransposons. Plant Physiol. 2018;176:1410–1422. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.01310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Han Y, Wessler SR. MITE-Hunter: a program for discovering miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements from genomic sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e199. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flynn JM, et al. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:9451–9457. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1921046117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grabherr MG, et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:357–360. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li H, et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pertea M, et al. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015;33:290–295. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haas BJ, et al. Improving the Arabidopsis genome annotation using maximal transcript alignment assemblies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:5654–5666. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnson AD, et al. SNAP: a web-based tool for identification and annotation of proxy SNPs using HapMap. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2938–2939. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guigó R, Knudsen S, Drake N, Smith T. Prediction of gene structure. J. Mol. Biol. 1992;226:141–157. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90130-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Majoros WH, Pertea M, Salzberg SL. TigrScan and GlimmerHMM: two open source ab initio eukaryotic gene-finders. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:2878–2879. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lomsadze A, Burns PD, Borodovsky M. Integration of mapped RNA-Seq reads into automatic training of eukaryotic gene finding algorithm. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:e119–e119. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stanke M, et al. AUGUSTUS: ab initio prediction of alternative transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W435–439. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Keilwagen J, Hartung F, Grau J. GeMoMa: homology-based gene prediction utilizing intron position conservation and RNA-seq data. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019;1962:161–177. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9173-0_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haas BJ, et al. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the program to assemble spliced alignments. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R7. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blum M, et al. The InterPro protein families and domains database: 20 years on. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:D344–D354. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cantalapiedra CP, Hernández-Plaza A, Letunic I, Bork P, Huerta-Cepas J. Eggnog-mapper v2: Functional annotation, orthology assignments, and domain prediction at the metagenomic scale. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021;38:5825–5829. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msab293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.2024. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR27885842

- 55.2024. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR27885834

- 56.2024. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR27885835

- 57.2024. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR27885836

- 58.2024. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR27885837

- 59.2024. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR27885838

- 60.2024. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR27885839

- 61.2024. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR27885840

- 62.2024. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR27885841

- 63.2024. NCBI GenBank. JAZDXJ000000000

- 64.Wang J, 2024. Chromosome-level genome assembly of Euphorbia tirucalli (Euphorbiaceae), a highly stress-tolerant oil plant. Figshare. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Rhie A, Walenz BP, Koren S, Phillippy AM. Merqury: reference-free quality, completeness, and phasing assessment for genome assemblies. Genome Biol. 2020;21:1–27. doi: 10.1186/s13059-020-02134-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- 2024. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR27885842

- 2024. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR27885834

- 2024. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR27885835

- 2024. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR27885836

- 2024. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR27885837

- 2024. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR27885838

- 2024. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR27885839

- 2024. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR27885840

- 2024. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRR27885841

- 2024. NCBI GenBank. JAZDXJ000000000

- Wang J, 2024. Chromosome-level genome assembly of Euphorbia tirucalli (Euphorbiaceae), a highly stress-tolerant oil plant. Figshare. [DOI] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Fluorescence histograms of flow cytometry for Euphorbia tirucalli.

Data Availability Statement

All software and pipelines used in this study were implemented according to the manuals and protocols provided by the software developers. Versions of the software have been described in Methods. No custom code was used in this study.