Abstract

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disease, and its prevalence is increasing. Currently, no effective therapies for PD exist. Marine-derived natural compounds are considered important resources for the discovery of new drugs due to their distinctive structures and diverse activities. In this study, tetrahydroauroglaucin (TAG), a polyketide isolated from a marine sponge, was found to have notable neuroprotective effects on MPTP/MPP+-induced neurotoxicity. RNA sequencing analysis and metabolomics revealed that TAG significantly improved lipid metabolism disorder in PD models. Further investigation indicated that TAG markedly decreased the accumulation of lipid droplets (LDs), downregulated the expression of RUBCN, and promoted autophagic flux. Moreover, conditional knockdown of Rubcn notably attenuated PD-like symptoms and the accumulation of LDs, accompanied by blockade of the neuroprotective effect of TAG. Collectively, our results first indicated that TAG, a promising PD therapeutic candidate, could suppress the accumulation of LDs through the RUBCN-autophagy pathway, which highlighted a novel and effective strategy for PD treatment.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, compound TAG, lipid metabolism, RUBCN

Introduction

As the second most common neurodegenerative disease in the world, Parkinson’s disease (PD) affects approximately 1% of adults older than 60 years and is pathologically characterized by the progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons [1]. The typical clinical symptoms of PD include motor impairment and nonmotor symptoms, which severely diminish quality of life [2–6]. Although the aetiology of PD has not yet been identified, several factors, including genetics and environmental influences, are strongly related to the pathogenesis of PD, which can cause physiological or pathological events such as mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and apoptosis [7–9]. The currently available clinical drugs can delay disease progression but cannot cure PD and can even cause serious adverse reactions [10]. Thus, novel anti-Parkinson drugs with reliable efficacy and fewer side effects are urgently needed.

Marine natural products, which are among the richest sources for drug development, have attracted increasing interest and widespread attention owing to their wide range of bioactive properties, such as anti-inflammatory, antioxidative, antibacterial, and antitumour effects [11–16]. In particular, numerous studies have verified that these compounds have great potential as candidate drugs for the treatment of PD [17–19]. In our previous experiments, tetrahydroauroglaucin (TAG), a polyketide isolated from marine sponges, was preliminarily found to improve the viability of SH-SY5Y cells exposed to MPP+/H2O2. To date, the antioxidant effect of TAG has only been observed in vitro, and the ameliorative effect of TAG on neurodegenerative diseases, such as PD, has not yet been reported [20].

Lipids, the main components of cell membranes, are essential for signal transduction and energy metabolism [21, 22]. The brain is the second most lipid-rich tissue after adipose tissue. Lipid metabolism in the brain, which highly influences the host’s emotion, perception, and behaviour, plays a key role in the normal physiological function of neurons and the development of brain structures. Increasing evidence suggests that aberrant lipid metabolism is also a fundamental feature of neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Huntington’s disease (HD), and PD [23–25]. However, the mechanism through which lipid metabolism regulates the progression of PD remains to be elucidated.

In this study, the neuroprotective effects of TAG were comprehensively and systematically assessed in cellular and animal models of PD induced by 1-methyl-4-phenyl-pyridinium ion (MPP+)/H2O2 and 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP), respectively. Furthermore, an integrated approach combining RNA sequencing, metabolomics, and bioinformatics was applied to analyse the effect of TAG on lipid metabolism in PD models. Genetic knockdown or overexpression strategies were employed to explore the potential targets of TAG and the involved pathways. Thus, the results contribute to the understanding of the pathogenesis of PD and how TAG ameliorates PD.

Materials and methods

Mice

C57BL/6 mice (male, 10–12 weeks old) and pregnant female mice were obtained from the Laboratory Animal Centre of Nanjing Medical University and were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions. The animals were housed under 12 h light/12 h dark conditions in a controlled-temperature environment and were given free access to food and water. C57BL/6 mice (male, 10–12 weeks old) were used for the MPTP-induced PD mouse model, and time-pregnant female mice (Day 14/15) were used for primary neuron culture. All animal experiments were approved by the Nanjing Medical University Institutional Animal Care and Research Committee (IACUC code, 1903038).

Preparation of primary mouse neurons

As described previously [26, 27], primary neurons were harvested from the ventral mesencephalic tissues of C57BL/6 mice on embryonic day 14/15 (E14/15). Briefly, mesencephalic cells were trypsinized with 0.25% (w/v) trypsin at 37 °C for 10 min, followed by gentle dissociation in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Gibco, 11965092) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS, Sigma, 12003C). The harvested cells were seeded at a density of 600,000/mL in 6-well plates (NEST Biotechnology Co. Ltd., Wuxi, China) coated with poly-L-lysine (Sigma, P8920). Neurons were cultured in neurobasal medium supplemented with 2% B27 (Gibco, 17504044), 0.5 mM L-glutamax, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 until maturity.

Cell culture, treatment, and transfection

Neural SH-SY5Y cells (ATCC, CRL-2266) and PC12 cells (ATCC, CRL-1721) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. After being pretreated with TAG for 1 h, the cells were treated with MPP+ (Sigma‒Aldrich, D0048) or H2O2 (Sinopharm, 10011218) for 24 h. For transfection, the plasmid Rubcn (NCBI gene ID: 9711) was obtained from the Public Protein/Plasmid Library (PPL, Nanjing, China). Gene knockdown was achieved by using small interfering RNA (siRNA) synthesized by Sangon (Shanghai, China) directed against Rubcn. The sequences of the siRNAs targeting Rubcn are shown in Table S1. According to the manufacturer’s instructions, the Rubcn plasmid and siRNA were transfected into SH-SY5Y cells or neurons for 48 h using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, L3000015) and Lipofectamine™ RNAiMAX (Invitrogen, 13778150) reagents, respectively.

Apoptosis assay

The apoptosis of SH-SY5Y cells was detected with Annexin V/PI apoptosis detection kits (Yeasen, 40304ES50, 40305ES50) according to the supplier’s instructions. The collected cells were washed with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and suspended in 100 μL of 1× binding buffer, after which the cells were stained with 5 μL of Annexin-V and PI solution in the dark for 15 min. The stained cells were analysed with a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

Detection of reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and mitochondrial membrane potential

MitoSOX™ Red (Thermo Fisher Scientific, M36008) and JC-1 Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Detection Kits (Thermo Fisher Scientific, M34152) were used to monitor the generation of mitochondrial ROS and the MMP (ΔΨm), respectively. In brief, the cells were incubated with MitoSOX™ Red (5 μM) and the JC-1 probe (10 μg/mL) in the dark for 30 min following the manufacturer’s protocol. The stained cells were analysed by flow cytometry. All of the fluorescence images were obtained by confocal microscopy (Carl Zeiss, LSM710) or an Olympus BX51 epifluorescence microscope.

MPTP-induced PD mouse model and treatments

All male C57BL/6 mice were randomly assigned to receive MPTP (20 mg/kg, s.c., Sigma, M0896) or saline once daily for 5 days. Selegiline (GLPBIO, Montclair, CA, USA, GC19799), a positive control, was dissolved in saline. According to our previous study, low, medium and high doses of TAG (10, 20 and 40 mg/kg, respectively) were prepared with normal saline containing 2% DMSO, 30% PEG 300 and 5% Tween 80. Starting from the first day before MPTP administration, mice in the treatment groups were given TAG (i.p.) or selegiline (10 mg/kg, i.g.) once a day for 9 days [28]. Seven days after the last injection of MPTP, the mice were sacrificed for further investigation.

Behaviour tests

To evaluate the motor function of MPTP-induced PD model mice, we used the open field test, rotarod test and pole test [29]. For the open field test, the mice were placed in an activity monitoring chamber (20 cm× 20 cm× 15 cm) for 15 min before the start of the test to adapt to the environment. The movement and speed in 5 min were measured automatically using open-field software (Clever Sys Inc., VA, USA). For the rotarod test, all mice were pretrained for 3 consecutive days on the rotarod apparatus with an acceleration from 4 to 40 r/min within 5 min to acclimate to the test. The mean duration of three trials on the rotarod was recorded by a rotarod analysis system (Jiliang, Shanghai, China). For the pole test, the mice were placed on the top of a 50-cm wooden pole with a diameter of 1 cm, which was wrapped with bandage gauze. The animals were trained for 3 days before the test. The total time required to reach the base of the pole was recorded as the locomotion activity time.

Immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry

Cells were seeded on coverslips and washed 3 times with PBS, followed by fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 15 min. Subsequently, the cells were permeabilized with PBS containing 0.2% Triton X-100 (PBST) and then blocked with 5% BSA in PBST for 30 min. Mice were transcardially perfused with PBS, and the brains were isolated, fixed in 4% PFA, and then sequentially transferred to 20% and 30% sucrose for cryoprotection at 4 °C. Tissues were then embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound (Sigma Aldrich, USA) and sectioned with a microtome at a thickness of 30 μm (Leica Microsystems, Leica CM1950). The brain sections were washed with PBS, permeabilized with 0.25% PBST, and blocked with 10% normal goat serum for 1 h. After blocking, the cells and sections were incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight, followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific Cat# A-11008) and Alexa Fluor 555-conjugated secondary antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific Cat# A-21422) for immunofluorescence studies. The primary antibodies used in the experiment were as follows: mouse anti-Tubbb3 (Proteintech Cat# 66375-1-Ig), mouse anti-MAP2 (Proteintech Cat# 17490-1-AP), mouse anti-TH (Sigma‒Aldrich Cat# T1299), rabbit anti-RUBCN (Proteintech Cat# 21444-1-AP), rabbit anti-Iba-1 (Wako Fujifilm Cat# 019-19741), mouse anti-GFAP (Millipore Cat# MAB360), and mouse anti-NeuN (Millipore Cat# MAB377). The nuclei were stained with Hoechst (1:1000, Sigma, 14533). For colocalization analyses, after incubation with the specified probe for 24 h, lysosomes were stained with 50 nM LysoTrackerTM Red DND-99 (Thermo Fisher Scientific Cat# L7528) for 1 h. For histological studies, primary neurons or brain sections were incubated with primary antibodies and appropriate secondary antibodies, such as goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody or goat anti-mouse IgM secondary antibody. Immunoreactivity was visualized by diaminobenzidine (DAB) chromogen substrate solution (Dako) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For Nissl staining, sections were stained with Nissl Staining Solution (Solarbio, G1430) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Fluorescence signals were captured with confocal microscopy (Carl Zeiss, LSM710), and the fluorescence images were analysed with Zen software (Carl Zeiss).

Lipid droplet analysis

Intracellular lipid droplets were detected by an Oil Red O kit (Sigma, O0625) and BODIPY 493/503 dye (Invitrogen, D3922). For Oil Red O staining, the fixed cells were washed with water and incubated in 60% isopropanol for 5 min. After incubation, the isopropanol was removed, and the solution was replaced with 0.3% Oil Red O working solution for 5 min. The nuclei were identified by haematoxylin staining for 10 s. For BODIPY 493/503 staining, the cells were washed with PBS and stained with 7.5 μg/mL BODIPY 493/503 in PBS for 5 min. The stained cells were analysed by flow cytometry. All images were captured by an Olympus BX51 epifluorescence microscope or a confocal microscope.

Transmission electron microscopy

Fresh midbrain tissues or SH-SY5Y cells were collected and fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde at 4 °C overnight, followed by postfixation in 1% osmium tetroxide for 2 h. Samples were then dehydrated in a series of ethanol solutions, embedded in Epon 812 epoxy resin (SPI Science, 90529-77-4), and cut into 60 nm-thick sections using a Leica UC7 ultramicrotome (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). The sections were stained with 2% uranyl acetate and 2% lead citrate for 15 min at room temperature, and digital micrographs were acquired with a transmission electron microscope (Hitachi, HT7700).

Real-time qPCR

Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and reverse-transcribed into cDNA with HiScript III-RT SuperMix for qPCR (+gDNA wiper) (Vazyme Biotech Co.,Ltd, R323-01, Q341-02) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. GAPDH and β-actin were used as housekeeping genes. The primer sequences used for RT‒qPCR are shown in Table S2.

RNA sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from primary neurons with TRIzol reagent and quantified with a NanoDrop ND-1000 (NanoDrop, Wilmington, DE, USA). RNA integrity was assessed with a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent, CA, USA). Sequencing libraries were prepared using the NEBNext Ultra RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs) following the manufacturer’s recommendation. The libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq™ 6000 (LC-Bio Technology Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China) using a 2 × 150 paired-end configuration.

To identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between two different groups, the expression level of each transcript was calculated according to the FPKM. The differentially expressed mRNAs were selected by the R package edgeR (https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/edgeR.html) with a fold change >1.5 and adjusted P < 0.05. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA; https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea) was used to identify altered pathways in the samples from different experimental groups. Additionally, GO and KEGG functional enrichment analyses were performed to identify which GO terms and metabolic pathways were significantly enriched in the DEGs at a Bonferroni corrected P < 0.05 compared with the whole transcriptome background.

Western blot analysis

Frozen midbrain tissue or SH-SY5Y cells were homogenized to extract the proteins with RIPA buffer (Sperikon Life Science & Biotechnology co., Ltd), and the total protein concentration was determined by a BCA kit (Beyotime, P0010S). Then, 30 μg of total protein was separated by SDS‒PAGE and subsequently blotted onto a PVDF membrane. The membrane was blocked with TBS-T (TBS with 0.1% Tween 20, pH 7.6) containing 5% skim milk for 2 h at room temperature. The PVDF membrane (Millipore) was then incubated at 4 °C overnight with mouse anti-TH, rabbit anti-RUBCN, mouse anti-GAPDH (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Cat# sc-32233), and mouse anti-β-actin (Thermo Fisher Scientific Cat# MA5-15739) primary antibodies. Later, the PVDF membrane was incubated at room temperature for 1 h with HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (1:3000). Finally, the protein bands were detected with enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL, Thermo Fisher, 32106) and visualized with an LAS4000 Mini Imager. ImageJ Software v1.30 (US National Institutes of Health) was used to calculate the optical density of the gel bands.

Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) datasets

Rubcn mRNA expression in PD patients was determined by examining GEO datasets (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) (GSE7621, GSE6613, GSE20168, and GSE24378). The raw counts were analysed online through GEO2R [30]. Data on the substantia nigra of 9 healthy controls and 16 PD patients were obtained from the GEO dataset GSE7621. The expression of Rubcn in peripheral blood was obtained from the GSE6613 dataset (50 patients with PD and 22 healthy controls). For the analysis of Rubcn expression in the prefrontal cortex, the data were obtained from GSE20168, which included 15 replicates for the controls and 14 replicates for PD patients. With respect to gene expression in the dopaminergic neurons of PD patients, the data were obtained from GSE24378, which included 8 PD patients and 9 control subjects. The Mann‒Whitney U test or Student’s t test was used to analyse the differences between the two groups.

Autophagy analysis

For autophagic flux measurements, SH-SY5Y cells were transfected with stubRFP-sensGFP-LC3 adenoviruses (Hanbio, HB-AP2100001) [31]. After TAG treatment, confocal microscopy was used to observe LC3 puncta in MPP+-treated SH-SY5Y cells.

Stereotaxic injection

The recombinant AAVs 2/9-EGFP were synthesized and packaged by BrainVTA Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). For successful infection, the injected vector titre was prepared at 5 × 1012 viral genomes (vg)/mL. C57BL/6 mice were bilaterally injected with 1 μL of a mixture of AAVs 2/9-DIO-EGFP and AAVs 2/9-TH-Cre (1:1) into the substantia nigra [anteroposterior (AP) = −3.1 mm, mediolateral (ML) = ±1.2 mm, dorsoventral (DV) = −4.3 mm from bregma] at a rate of 0.2 μL/min. After surgery, the recovery of the animals was monitored on the day after injection, and one month later, the infection efficiency was verified by biochemical analysis and immunofluorescence staining.

Statistical analysis

All the data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 9, and statistical significance was determined by one-way or two-way ANOVA combined with Dunnett’s or Tukey’s multiple comparison tests. All the data were analysed by the appropriate statistical methods, and P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

TAG inhibited MPP+-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis in SH-SY5Y cells

In previous studies, the potential neuroprotective effects of 131 kinds of marine-derived compounds were investigated (Fig. S1). After 1 μM administration, the effect of the 131 compounds on cell viability was determined by the CCK-8 method. The results showed that 65 compounds had no obvious cytotoxic effects on SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. S1a). MPP+ (0.5 mM) or H2O2 (100 μM), which are commonly administered to induce a PD-like phenotype, were used to successfully establish the SH-SY5Y cell injury model in this study (Fig. S1b, c). Five compounds significantly improved the viability of the SH-SY5Y cells stimulated with MPP+ or H2O2 (Fig. S1d). In particular, the effect of TAG was most notable, which indicated that TAG might be a potent neuroprotective compound (Fig. S1d, e).

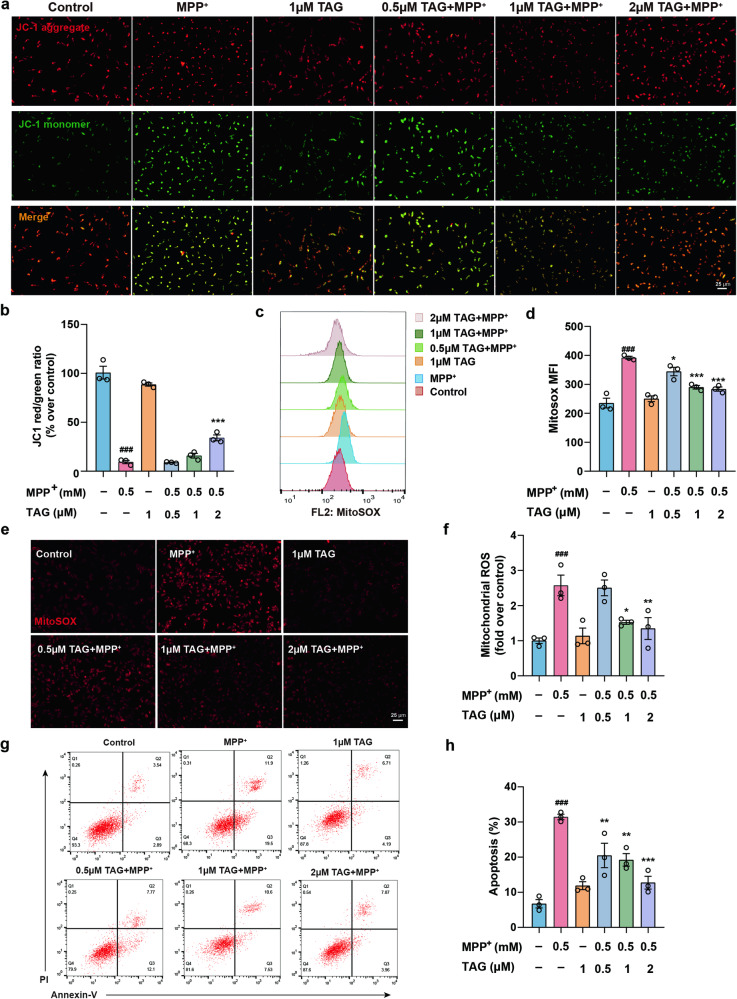

Next, the neuroprotective effect of TAG was further investigated in MPP+-treated SH-SY5Y cells. The IC50 of TAG in SH-SY5Y cells was 25.43 μM (Fig. S2a). Additionally, at concentrations of 1 μM and 2 μM, TAG markedly increased cell viability and decreased LDH leakage, which helped to protect the cells from MPP+-induced cell death (Fig. S2b, c). The mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) and superoxide generation, which reflect the processes of oxidative phosphorylation and electron transport, are key indicators of mitochondrial activity [32]. In the mitochondria of normal cells, JC-1 aggregated and emitted red fluorescence, but in damaged cells with collapsed mitochondria, JC-1 was not able to accumulate in the mitochondria and emitted green fluorescence. The JC-1 red/green ratio and MitoSOX were used to determine the MMP and mitochondrial ROS production, respectively [33]. As expected, exposure to MPP+ significantly increased mitochondrial ROS generation and decreased JC-1 accumulation in SH-SY5Y cells, while TAG markedly abrogated these changes (Fig. 1a–f). Moreover, the proportion of early apoptotic and dead cells significantly increased to 31.43% ± 0.78% in MPP+-treated SH-SY5Y cells, showing that MPP+ notably induced the apoptosis of SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 1g, h). After treatment with 0.5, 1 or 2 μM TAG, the number of apoptotic cells markedly decreased (Fig. 1g, h). These results indicated that TAG could mitigate mitochondrial damage and apoptosis in MPP+-treated SH-SY5Y cells.

Fig. 1. TAG improved mitochondrial dysfunction and reduced apoptosis in MPP+-treated SH-SY5Y cells.

a, b Potential alterations in the mitochondrial membrane were detected by JC-1-specific fluorescence. The Δψm is expressed as the red (JC-1 aggregate)/green (JC-1 monomer) fluorescence intensity. c–f Changes in mitochondrial ROS were detected by incubation with the MitoSOX probe and observation via fluorescence microscopy or analysis via flow cytometry. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity. g, h The percentage of apoptotic MPP+-treated SH-SY5Y cells. The data were analysed by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test. ###P < 0.001 vs. the control group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 vs. the MPP+ group. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

TAG ameliorated neuronal damage and oxidative stress in vitro

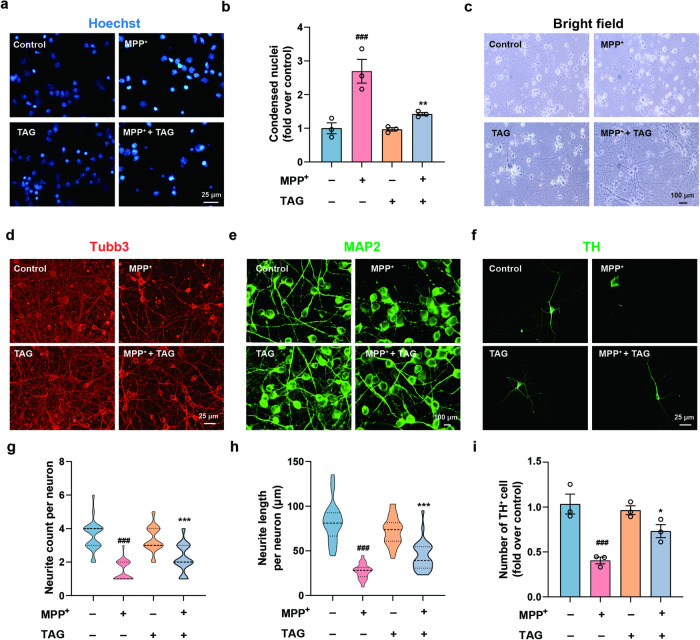

To further evaluate the neuroprotective effect of TAG on MPP+ cytotoxicity, primary neurons were cultured. Based on the results of the CCK-8 assay, 30 µM MPP+ was selected as the optimal concentration for inducing neuronal injury (Fig. S2d). Similarly, preincubation with TAG antagonized the MPP+-induced reduction in the viability of primary neurons, as determined by CCK-8 and LDH assays (Fig. S2e, f). Neuronal apoptosis was assessed by Hoechst 33258 staining, which can visualize apoptotic nuclei. Compared to those in the control group, these neurons underwent apoptosis after MPP+ treatment, while TAG significantly rescued the neurons from MPP+-induced apoptosis (Fig. 2a, b). Furthermore, brightfield and immunofluorescence images showed that primary neurons exhibited soma and axon injury under MPP+ exposure and that TAG treatment attenuated this damage (Fig. 2c–e, g, h). Tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), a specific marker of dopaminergic neurons, was used to investigate the morphological changes in TH-immunopositive neurons following MPP+ treatment in the presence or absence of TAG. We demonstrated that the exposure of primary neurons to MPP+ for 24 h resulted in significant axonal damage in surviving TH-positive cells. However, neuron cultures pretreated with TAG and then subjected to MPP+ maintained normal TH-positive cell morphology (Fig. 2f, i). Thus, TAG could notably prevent MPP+-induced neuropathological responses in vitro.

Fig. 2. Neuroprotective effects of TAG on MPP+-induced primary neurons.

a, b Hoechst staining of primary neurons (blue) and the statistical results of the fluorescence intensity. c Bright-field microscopy images of the morphology of primary cultured neurons after TAG treatment. d Tubb3 staining of primary neurons (red). e, f MAP2 and TH staining of primary neurons (green). g, h Quantification of the number and length of neurites per neuron. Neurites were traced by MAP2 staining (n = 30). i Quantification of the fluorescence intensity in TH+ neurons (n = 3). The data were analysed by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test. ###P < 0.001 vs. the control group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 vs. the MPP+ group. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Cellular oxidative stress is also a hallmark of the pathogenesis of PD [34]. To evaluate the inhibitory effects of TAG on oxidative stress, PC12 cells were treated with H2O2. The IC50 value of TAG in PC12 cells was 22.48 μM (Fig. S2g). Similar to its effect on MPP+-induced SH-SY5Y cells, 2 μM TAG pretreatment markedly decreased LDH release and improved the viability of PC12 cells exposed to H2O2 (Fig. S2h, i). In contrast to those in normal PC12 cells, the mRNA levels of Gpx1, Sod1, Sod3 and Cat were significantly decreased after H2O2 treatment, and the mRNA levels of Nox1 and Nox2 were increased. However, TAG significantly abrogated the changes in the expression of these genes in H2O2-treated PC12 cells (Fig. S3a–f). Furthermore, commercial kits for SOD, CAT, MDA, GSH and GSSG were used to assess the antioxidative effects of TAG. Consistent with the changes in the expression of genes related to oxidative stress, total GSH, the GSH/GSSG ratio, and the activities of SOD and CAT were significantly enhanced, while the level of MDA was notably reduced in H2O2-stimulated PC12 cells after TAG treatment. Remarkably, TAG could protect PC12 cells from H2O2-induced oxidative stress, which indicated that TAG had antioxidative effects (Fig. S3g, k). Taken together, these findings highlighted the neuroprotective effects of TAG in vitro.

TAG protected against MPTP-induced neurodegeneration in vivo

Encouraged by the above in vitro results, an MPTP-induced PD mouse model was subsequently established to further investigate the neuroprotective potential of TAG in vivo (Fig. 3a). The locomotor activity of PD model mice was evaluated by the open-field test (OFT). Rotarod and pole tests were used to assess motor coordination and balance. Following the administration of high-dose TAG (TAG-H, 40 mg/kg), MPTP-induced mice displayed greater locomotor activity in the OFT, increased duration in the rotarod test, and reduced time spent climbing to the bottom of the rod in the pole test, which suggested that TAG significantly ameliorated MPTP-induced motor deficits (Fig. 3b–e). Compared with that in the MPTP group (~46.59% loss), the significant decrease in Nissl-stained neurons in the substantia nigra compacta (SNc) was attenuated after TAG-H treatment (recovered to ~81.08%) (Fig. 3f, g). In addition, TAG treatment increased the number of TH-positive dopaminergic neurons by ~34.30% in MPTP-treated mice, as confirmed by quantification of the relative protein expression of TH (Fig. 3h, i, Fig. S4d, e). Similarly, the decrease in dopamine and dopamine metabolites (DOPAC and HVA) triggered by MPTP was abrogated in the striatum of TAG-treated mice (Fig. S4a–c). Overall, the administration of TAG significantly alleviated PD-like symptoms in vivo, suggesting that TAG might serve as a promising candidate for PD treatment.

Fig. 3. TAG protected against MPTP-induced pathology in vivo.

a Schematic diagram of MPTP-treated mice. b–e Behavioural parameters were measured by the open field test (OFT), rotarod test and pole test after 7 days of MPTP administration. n = 8–10 mice per group for behavioural assays. f–i Representative images and quantification of Nissl and TH staining in the substantia nigra compacta (SNc) of vehicle- and TAG-treated mice in the presence or absence of MPTP treatment. The data were analysed by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test. ##P < 0.01 and ###P < 0.001 vs. the control group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.01 vs. the MPTP group.

TAG improved lipid dysregulation in PD

To further elucidate the potential neuroprotective mechanism of TAG, whole-genome RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) was carried out on primary neurons pretreated with TAG for 1 h and then stimulated with MPP+ for 24 h. Principal component analysis and a heatmap of the RNA-seq data revealed global changes in gene expression in the different groups (Fig. S5a and Fig. 4a). Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) [35], a nonparametric rank-based method, was applied to compare the gene expression of MPP+-induced neurons with/without TAG treatment. Based on the normalized enrichment score (NES), GSEA using hallmark gene sets revealed enrichment of the oestrogen response late, coagulation and fatty acid metabolism pathways in MPP+-induced neurons after TAG treatment (Fig. 4b, c). Moreover, the comprehensive plasma metabolomic profiles of TAG-treated mice were notably distinct from those of the MPTP-treated mice, in which altered metabolites were mainly involved in the glycerophospholipid metabolic pathway (Figs. S6 and S7). Herein, the integrated analysis of RNA-seq and the plasma metabolome indicated that lipid metabolism was an important characteristic of PD and that TAG may treat PD by modulating lipid metabolism.

Fig. 4. TAG ameliorated MPP+/MPTP-induced lipid metabolic disorder in vivo and in vitro.

a Hierarchical clustered heatmap of gene expression profiles in MPP+-induced neurons after TAG treatment. b, c GSEA for “Hallmark” gene sets using unfiltered gene expression data of the MPP++TAG group compared with the MPP+ group. FDR false discovery rate, NES normalized enrichment score. d, f Confocal microscopy images of intracellular LDs in SH-SY5Y cells stained with BODIPY 493/503 dye (green). Scale bar, 5 μm. Fluorescent BODIPY quantification is shown. e, g The effect of TAG on MPP+-mediated LD accumulation was determined by BODIPY 493/503 staining followed by flow cytometry analysis. Representative histograms and mean fluorescence intensities (MFIs) in SH-SY5Y cells are shown. h The deposition of LDs in the MPP+-treated SH-SY5Y cells was evaluated by Oil Red O staining after TAG treatment. Scale bar, 100 μm. i, j The number and size of LDs in SH-SY5Y cells were quantified. All experiments were performed in triplicate. k–m Representative TEM images of LD accumulation in the midbrains of MPTP-induced mice after TAG treatment. The number and size of LDs were quantified. Scale bar, 100 nm. n = 6 mice per group. The data were analysed by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test. ###P < 0.001 vs. the control group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 vs. the MPP+/MPTP group.

Lipid droplets (LDs), which are independent organelles of lipid storage, are largely associated with lipid metabolism, including lipid biosynthesis, metabolite transport, lipid uptake, and signal transduction [36, 37]. To further validate the effect of TAG on lipid metabolism during PD progression, MPP+-induced SH-SY5Y cells were stained with BODIPY or Oil Red O 493/503 to label LDs. TAG significantly reduced the population of BODIPY-positive cells in the MPP+-induced SH-SY5Y cell model (Fig. 4d–g). Compared to cells exposed to MPP+ alone, the number of Oil Red O-stained cells decreased after TAG treatment (Fig. 4h–j). Further electron microscopy analysis of the SNc revealed that the size of LDs was significantly greater in MPTP-induced mice than in control mice, whereas a marked decrease was noted in TAG-treated mice (Fig. 4k–m). Moreover, TAG administration led to a marked reduction in triglyceride (TG) levels in the midbrains of MPTP-treated mice, while cholesterol (CHO) levels did not significantly differ among the different experimental groups (Fig. S5b, c). Together, these data confirmed that TAG could significantly ameliorate lipid metabolism disorder in PD.

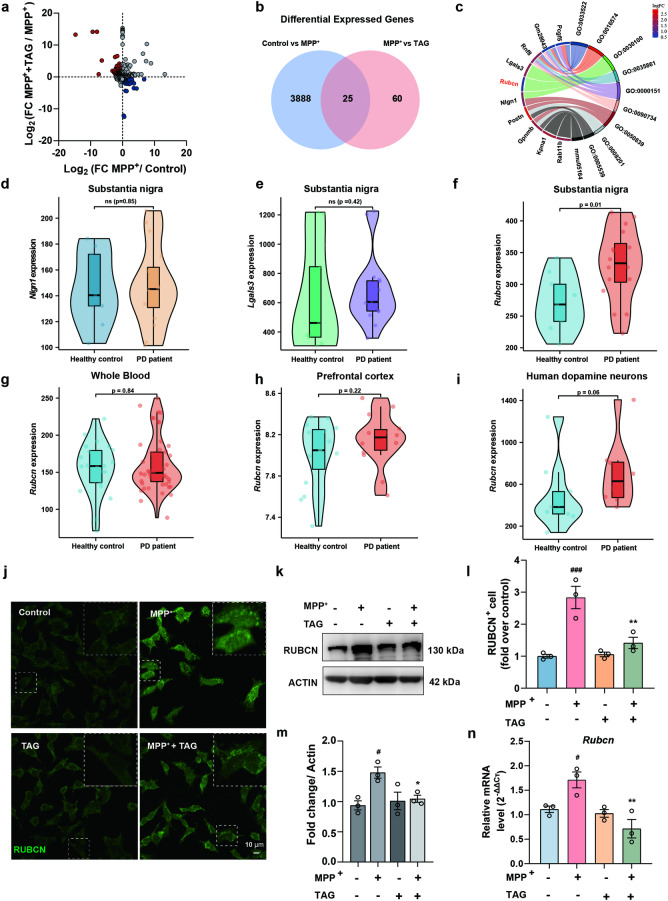

TAG downregulated the expression of RUBCN

The regulatory effect of TAG on lipid metabolism motivated us to further investigate its potential targets. Scatterplots of the results of whole RNA-seq analysis revealed that 71 genes were upregulated and 140 genes were downregulated in the MPP+-treated neurons compared to the control neurons, while TAG markedly reversed the expression of these genes in primary neurons (Fig. 5a). Based on the criteria of |log2FC| > 0.585 and P.adj < 0.05 for identifying DEGs, the Venn diagram indicated that 25 DEGs were shared between the control group vs. MPP+ group and the TAG+ MPP+ group vs. MPP+ group (Fig. 5b). The top three GO biological process terms enriched in the DEGs included GO:0033522, GO:0016574 and GO:0030100, with “endocytosis (GO:0030100)” as the most significantly enriched GO term. Among the DEGs, Lgals3 (P = 0.0002), Rubcn (P = 0.0001) and Nlgn1 (P = 0.0012) were the top three genes closely involved in the “endocytosis” process. Rubcn was the most highly expressed gene and was markedly elevated in MPP+-injured neurons (Fig. 5c). Importantly, the GEO disease database analysis demonstrated that the level of Rubcn was significantly increased in the SNc of PD patients (P = 0.01), while no significant changes were detected in the mRNA levels of Nlgn1 (P = 0.85) and Lgals3 (P = 0.42) between the healthy controls and PD patients (Fig. 5d–f). Consistently, the level of Rubcn was greater in the peripheral blood (P = 0.84), cortex (P = 0.22) and dopaminergic neurons (P = 0.06) of PD patients than in those of healthy controls (Fig. 5g–i). These findings emphasized the fundamental role of Rubcn in PD and inspired us to further explore the regulatory effect of TAG on Rubcn expression. Immunofluorescence, immunoblotting and qPCR experiments showed that the expression of Rubcn significantly decreased in the MPP+-treated SH-SY5Y cell injury model after TAG treatment (Fig. 5j–n). Additionally, analysis of single-cell atlases of multiple mouse tissues revealed that Rubcn was mainly expressed in neurons of the central nervous system (Fig. S8a) [38]. Consistent with these data, interestingly, we discovered that Rubcn was predominantly expressed in the midbrain and neurons (Fig. S8b–e). Overall, these results revealed that Rubcn might be involved in the pathogenesis of PD.

Fig. 5. TAG downregulated the expression of RUBCN.

a The scatter plot underlines the DEGs in the MPP++TAG group compared with those in the MPP+-induced primary neuron group; upregulated genes are coloured red, and downregulated genes are coloured blue. b Venn diagram displaying the DEGs in the MPP+ and MPP++TAG groups (P.adj < 0.05, |log2FC| > 0.585). c Gene Ontology and KEGG enrichment analyses were based on DEGs. d–f The expression of Nlgn1, Lgals3 and Rubcn in the substantia nigra of healthy controls and PD patients was determined (GSE7621). The data were analysed by the Mann‒Whitney U test or Student’s t test. g–i Rubcn expression in peripheral blood, prefrontal cortex and dopamine neurons of healthy controls and PD patients (GSE6613, GSE20168 and GSE24378, respectively). The data were analysed by the Mann‒Whitney U test or Student’s t test. j, l Representative images and quantitative analysis of RUBCN-positive SH-SY5Y cells after MPP+ stimulation in the presence or absence of TAG treatment. k, m Western blot and corresponding quantification of the expression of RUBCN in MPP+-treated SH-SY5Y cells after TAG treatment. n The mRNA levels of Rubcn in MPP+-treated SH-SY5Y cells after TAG treatment were analysed by qPCR. All experiments were performed in triplicate. The data were analysed by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test. #P < 0.05 and ###P < 0.001 vs. the control group; *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.001 vs. the MPP+ group.

Effects of Rubcn knockdown and overexpression on MPP+-mediated neurotoxicity in vitro

To directly investigate the effect of Rubcn on PD pathology, knockdown of Rubcn in SH-SY5Y cells or primary neurons was established by transfection with specific siRNAs targeting Rubcn (KD), and nontargeting (scrambled) siRNAs were used as negative controls (NCs). Transfection efficiencies were validated by qPCR, immunoblotting and immunofluorescence assays. Rubcn siRNAs (hsa-Rubcn-KD#2 and mus-Rubcn-KD#a) were used to transfect SH-SY5Y cells and primary neurons, respectively (Fig. S9a–c, f). As expected, the knockdown of Rubcn markedly enhanced the viability of the MPP+-treated SH-SY5Y cells and restrained LDH release (Fig. S9d, e). Similar results were observed in primary neurons transfected with Rubcn siRNA (Fig. S9g, h). Furthermore, we observed that the knockdown of Rubcn markedly suppressed MPP+-induced apoptosis, mitochondrial ROS generation and neuronal injury. Notably, the transfection of Rubcn siRNA abolished the inhibitory effect of TAG on apoptosis and mitochondrial ROS generation in MPP+-stimulated SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 6a–d). The same conclusion was reached in hsa-Rubcn-KD#3-transfected SH-SY5Y cells, which were used to exclude any off-target effects (Fig. S10a–d, h, i). Likewise, TAG failed to protect primary neurons from MPP+-induced neuronal injury after si-Rubcn transfection (Fig. 6e–h). Furthermore, in vitro-generated SH-SY5Y cells were transfected with Rubcn overexpression plasmids, and the expression levels of Rubcn mRNA and protein were measured to evaluate the transfection efficiency (Fig. S11a–c). The overexpression of Rubcn significantly amplified MPP+-induced cytotoxicity by impairing cell viability and exacerbating apoptosis and mitochondrial dysfunction. However, pretreatment with TAG markedly alleviated the damage caused by Rubcn overexpression in MPP+-treated SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. S11d–i). Thus, the knockdown of Rubcn in SH-SY5Y cells and primary neurons significantly attenuated MPP+-induced neurotoxicity, while the overexpression of Rubcn had the opposite effect. The neuroprotective effects of TAG on SH-SY5Y cells and neurons were abrogated by Rubcn siRNA, which further confirmed that the anti-PD effect of TAG mainly relied on the inhibition of RUBCN expression.

Fig. 6. Knockdown of Rubcn abolished the protective effect of TAG against MPP+-induced toxicity.

a, c Apoptotic SH-SY5Y cells were detected by flow cytometric analysis and stained with Annexin-V/PI. b, d MitoROS in SH-SY5Y cells were evaluated with a MitoSOX fluorescent probe. e Representative images of mesencephalic primary DA neurons stained with TH and counterstained with DAB. g The neurite lengths of TH+ neurons were quantified. f, h Representative images of uninjured neurons stained with MAP2 (red) and RUBCN (green) antibodies and quantification of the fluorescence intensity in MAP2+ neurons. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst (blue). All experiments were performed in triplicate. The data were analysed by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001. ns not significant.

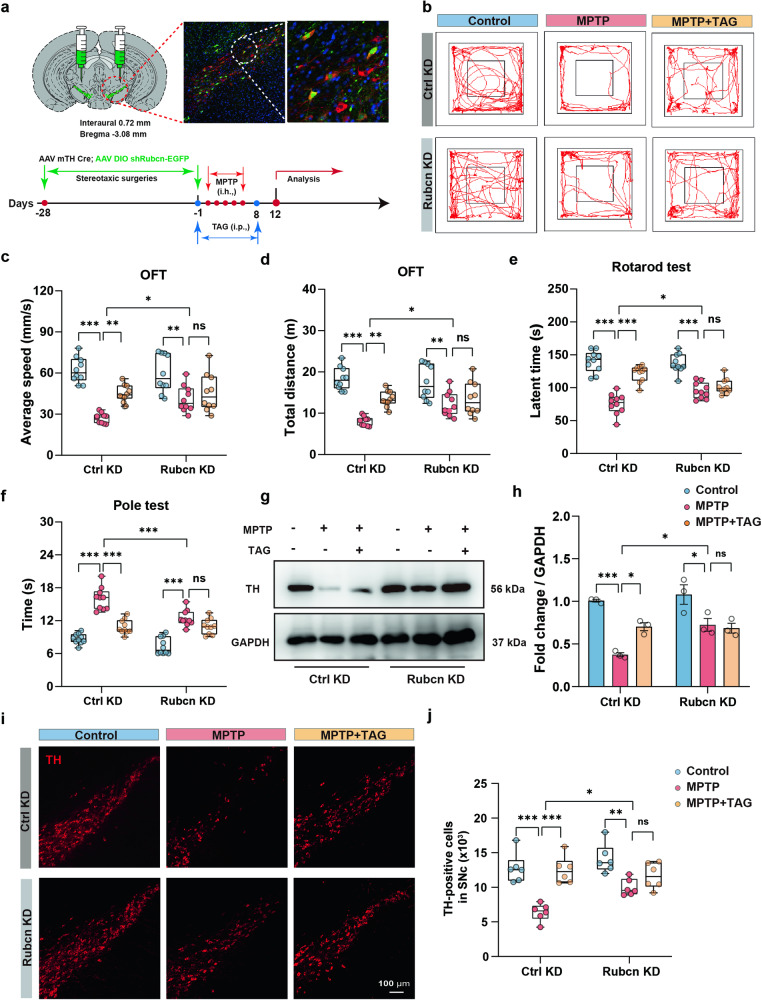

Rubcn depletion attenuated neurodegeneration in MPTP-induced PD model mice

Considering the neuroprotective role of Rubcn siRNA in vitro, a mixture of AAVs 2/9-DIO-shRNA (Rubcn)-EGFP and AAVs 2/9-TH-Cre (at a ratio of 1:1) was stereotaxically injected into the SNc to specifically knockdown Rubcn (Rubcn KD) in dopaminergic neurons in vivo. A mixed solution of AAVs 2/9-DIO-shRNA (scramble)-EGFP and AAVs 2/9-TH-Cre was used as a negative control (Ctrl KD). Colabelling with TH (red) and EGFP (Rubcn) confirmed that Rubcn was expressed in the majority of dopaminergic neurons 28 days after injection (Fig. 7a). The knockdown efficiency was validated by immunoblotting and qPCR analysis (Fig. S12a–c). As expected, the conditional knockdown of Rubcn significantly attenuated MPTP-induced motor impairment in the open-field, rotarod and pole tests (Fig. 7b–f). Compared with the Ctrl KD group, the Rubcn knockdown group exhibited a notably increased number of TH-positive neurons after MPTP treatment (Fig. 7i, j). Increased TH protein levels were also detected in MPTP-treated mice injected with Rubcn shRNA (Fig. 7g, h). On the other hand, after the knockdown of Rubcn, TAG lost its ability to protect against motor defects and the loss of dopaminergic neurons in MPTP-treated mice (Fig. 7b–j). In summary, our in vitro and in vivo data clearly indicated that Rubcn is a potential therapeutic target for PD and that the neuroprotective effect of TAG against PD is Rubcn dependent.

Fig. 7. The effects of TAG on MPTP-induced PD model mice were abrogated after sh-Rubcn transfection.

a Schematic diagram of stereotaxic virus injection procedures. b–f Behavioural parameters were measured by the OFT, rotarod test and pole test. n = 10 mice per group. g, h Representative immunoblot images and quantification of TH in the substantia nigra compacta. i, j Representative TH staining images of substantia nigra compacta in vehicle- and Rubcn-knockdown mice after TAG treatment. n = 6 mice per group. The data were analysed by two-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001. ns not significant.

Modulatory effect of TAG on the accumulation of LDs via the Rubcn-autophagy axis

To investigate the effect of Rubcn on lipid metabolism during PD progression, SH-SY5Y cells were transfected with Rubcn siRNA or plasmids. After the transfection of the Rubcn plasmid, the accumulation of LDs was significantly enhanced, as determined by Oil Red O staining, in MPP+-treated SH-SY5Y cells; however, TAG significantly decreased the accumulation of LDs (Fig. 8a, Fig. S13a, b). In contrast, in the context of MPP+-induced SH-SY5Y cells transfected with Rubcn siRNA, a significant reduction in the number of LDs was observed (Fig. 8b, Figs. S10e–g, j, k and S13c, d). Specifically, pretreatment with TAG was unable to inhibit the accumulation of LDs in MPP+-treated SH-SY5Y cells after Rubcn knockdown. These findings suggested that Rubcn was closely related to lipid metabolism during PD progression and that TAG could restore lipid homeostasis in a RUBCN-dependent manner.

Fig. 8. The inhibitory effect of TAG on the accumulation of LDs was mediated by the Rubcn-autophagy axis.

a Effects of Rubcn overexpression on the accumulation of LDs in the MPP+-treated SH-SY5Y cell model. b Effects of Rubcn knockdown on the accumulation of LDs in the MPP+-treated SH-SY5Y cell model. Representative images of LDs stained with BODIPY. c, d Effects of TAG on autophagy in the MPP+-treated SH-SY5Y cell model. Confocal micrographs of autophagic flux were examined through stubRFP-sensGFP-LC3 adenovirus transduction in SH-SY5Y cells. Electron microscopy analysis revealed autophagic vesicles or autolysosomes. e Effects of Rubcn knockdown on autophagy in SH-SY5Y cells treated with MPP+ with or without TAG. f Representative immunofluorescence images of BODIPY colabelled with LysoTracker in SH-SY5Y cells. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst (blue). Regions within the white-marked boxes are magnified. Scale bars, 2 μm. g Statistical analysis of the colocalization of BODIPY and LysoTracker in SH-SY5Y cells. h Schematic diagram of TAG inhibiting the accumulation of LDs and restoring lipid metabolism homeostasis in PD via the RUBCN-autophagy pathway. The data were analysed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test. ##P < 0.01 vs. the control group; *P < 0.05 vs. the MPP+ group. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Furthermore, GO analysis of MPP+-elicited primary neurons following TAG treatment predicted that Rubcn was involved in cellular endocytosis (Fig. 5c). Recently, because of its core role in the pathogenesis of PD, the participation of macroautophagy in endocytosis has increasingly attracted widespread interest [39, 40]. Consistently, autophagy was detected by visualizing autophagosomes/autolysosomes in MPP+/MPTP-induced PD models after TAG treatment. To monitor autophagic flux, SH-SY5Y cells were infected with adenovirus expressing stubRFP-sensGFP-LC3 via tandem fluorescence. Several studies have demonstrated that GFP fluorescence is sensitive to acidic conditions and is quenched after fusion with lysosomes, making autolysosomes appear as red puncta and autophagosomes appear as yellow puncta [41, 42]. Compared with control cells, SH-SY5Y cells subjected to MPP+ presented more autophagosomes and fewer autolysosomes (Fig. 8c, Fig. S13e, f). Electron microscopy revealed that the number of autophagosomes or autolysosomes significantly decreased in SH-SY5Y cells after exposure to MPP+ (Fig. 8d). However, TAG treatment markedly enhanced autophagic flux in the MPP+-treated SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 8c, d, Fig. S13e, f). Furthermore, the knockdown of Rubcn in MPP+-treated SH-SY5Y cells stimulated autophagic flux by significantly decreasing the number of autophagosomes and markedly increasing the number of autolysosomes (Fig. 8e, Fig. S13g, h). Strikingly, the regulation of autophagic flux by TAG treatment was blunted after the transfection of si-Rubcn into MPP+-induced SH-SY5Y cells. Furthermore, the accumulation of LDs in MPP+-treated SH-SY5Y cells was accompanied by impaired autophagic flux, suggesting that lysosome-based degradation is crucial to lipid homeostasis. As expected, MPP+ stimulation substantially decreased the colocalization of LDs with lysosomes, while TAG treatment increased the colocalization of LDs (Fig. 8f, g). These results indicated that TAG could inhibit LD accumulation through the lysosomal pathway. Collectively, these results confirmed that TAG treatment increased autophagic flux and further decreased the accumulation of LDs by downregulating Rubcn expression, which potentially indicated a plausible mechanism by which TAG impeded lipid metabolism disorder in PD.

Discussion

Brain lipid dysregulation has generally been linked to the aetiology, progression, and severity of neurodegenerative diseases [43, 44]. In this study, the marine-derived compound TAG was found to have a notable neuroprotective effect against MPTP/MPP+-induced neurotoxicity and ameliorate lipid metabolism disorder in PD models. Moreover, Rubcn was first shown to be expressed mainly in neurons, and its downregulation markedly attenuated MPTP/MPP+-mediated dopaminergic neuronal injury. Importantly, our findings provided substantial evidence that TAG could sharply decrease the accumulation of LDs and ameliorate the pathological symptoms of PD via the Rubcn-autophagy axis (Fig. 8h).

In the central nervous system, lipids are mainly divided into glycerol, glycerophospholipids, sphingosine lipids, and sterol lipids [45]. Disruption of brain lipid homeostasis can cause brain damage, oxidative stress and apoptosis, resulting in neural injury and neurodegeneration [46, 47]. In this study, the disorder of fatty acid metabolism and glycerophospholipid metabolism in PD model mice were significantly improved after TAG treatment. These results emphasized the crucial involvement of abnormal lipid metabolism in the pathology of PD, thereby offering promising prospects for the identification of novel diagnostic biomarkers for PD therapy.

Lipid droplets (LDs), composed of neutral fatty acids such as glycerolipids and sterol esters surrounded by polar lipids such as phospholipids and sterols, are present in the cytoplasm of various cell types involved in lipid metabolism [48]. Recently, more studies have focused on the role of LD deposition and accumulation in inflammation, oxidative stress and ageing in neuroglial cells [49, 50], whereas relatively few studies have investigated the role of neuronal LDs in PD pathology. Our study demonstrated that TAG could notably suppress the accumulation of LDs in PD models both in vitro and in vivo. Intriguingly, plasma metabolomics analysis revealed a high concentration of phosphatidylcholine in TAG-treated mice, which was reported to exert inhibitory effects on LD fusion [51]. This might be explained by the finding that the sizes of LDs were significantly decreased in PD mouse tissues after TAG treatment. Herein, we concluded that TAG could restore lipid homeostasis in PD models.

Despite the exciting advances in characterizing LD accumulation in recent years, the exact underlying mechanisms are still unknown. The findings from the combined analysis of RNA-seq data and clinical data of PD patients obtained from the GEO database revealed that the level of Rubcn was markedly upregulated in PD patients and that the expression of TAG was significantly decreased. The RUBCN protein is composed of multiple functional domains that modulate a variety of intracellular signalling cascades via interactions with its binding partners. Previous studies demonstrated that liver-specific Rubcn knockout could repress liver steatosis in mice fed a high-fat diet and that Rubcn was suppressed in several long-lived worms and calorie-restricted mice [52, 53]. In this context, how Rubcn affects the pathological process of PD is of particular interest. Rubcn can be expressed in most tissues and organs, but the mRNA expression of Rubcn was more abundant in the spleen, testis, cerebral cortex and lymph node than in other tissues according to mRNA sequencing [54]. Notably, our results revealed that Rubcn was highly expressed in neurons and the midbrain. More importantly, the results of this study further showed, for the first time, that the knockdown of Rubcn markedly improved PD-associated phenotypes and inhibited the accumulation of LDs. Moreover, Rubcn knockdown abolished the neuroprotective effect of TAG on PD-like pathology in vivo and in vitro. Furthermore, we conducted a biolayer interferometry (BLI) assay to measure the binding affinities of TAG and RUBCN (Fig. S14). The BLI results showed that the affinity of TAG for RUBCN was very weak, and the binding of TAG to RUBCN (Kd = 23.8 µM) was within the micromolar range, which indicated that TAG and RUBCN were unlikely to interact directly. In general, the levels of RUBCN in PD model mice were significantly increased and were notably reversed by TAG. Collectively, our results demonstrated that Rubcn knockdown contributed to lipid homeostasis and that TAG downregulated the expression of RUBCN, thereby exerting a neuroprotective effect on PD.

Although we confirmed that Rubcn could restore lipid homeostasis during PD progression, the molecular mechanisms underlying this complex regulation remain unclear. Autophagy, a protective cellular process, delivers cytoplasmic proteins and impaired organelles to the lysosome for degradation [55]. As previously reported, autophagy can directly affect lipid homeostasis [56]. Studies have indicated that the reduced activity and expression of phospholipase D1 result in impaired autophagic flux and the accumulation of α-synuclein, consequently increasing the severity of diseases caused by Lewy bodies such as PD [57]. Our data further confirmed that TAG markedly ameliorated autophagy defects by inhibiting the expression of RUBCN and increasing the number of autolysosomes to enhance autophagic flux. Lipophagy is a type of selective autophagy that targets LDs for degradation, but the molecular mechanism of lipophagy is unknown. Considering the roles of TAG in the regulation of autophagy, we further used siRNA-mediated knockdown of lipophagy-specific receptors such as Spartin and Orp8 in MPP+-treated SH-SY5Y cells to analyse the effect of TAG on lipophagy (Fig. S15a). As shown, Spartin or Orp8 knockdown significantly increased the accumulation of LDs (Fig. S15b, c). Knockdown of Spartin or Orp8 also excessively induced the generation of mitochondrial ROS in MPP+-treated SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. S15d–g). In particular, knockdown of Spartin abolished the effects of TAG, which further suggested that TAG is a therapeutic regulator of lipophagy and lipid metabolism in PD (Fig. S15). However, how this occurs is poorly understood and requires further investigation.

In summary, this work indicated that lipid metabolism disorder is closely related to PD progression and could be a promising therapeutic approach for treating neurodegenerative diseases. Rubcn was first found to play a critical role in PD pathogenesis by modulating the accumulation of LDs. Furthermore, the neuroprotective effect of TAG mainly relies on the Rubcn-autophagy axis to restore lipid metabolism homeostasis in PD. Our study provides a novel strategy for the clinical treatment of neurodegenerative diseases, including PD.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81991523, 82003725) and the National Key R&D Programme of China (No. 2021ZD0202901). We thank Prof. RXT from Nanjing University for supplying the marine-derived natural compounds.

Author contributions

GH and RXT conceived and designed the study. The natural compounds were provided by ZWT and RXT. PY, YL, QHH, XHX and SYM performed the experiments and analysed the data. PY and YL wrote the manuscript. JHD provided technical support. GH and ML revised the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Pei Yang, Yang Liu

Contributor Information

Ming Lu, Email: lum@njmu.edu.cn.

Ren-xiang Tan, Email: rxtan@nju.edu.cn.

Gang Hu, Email: neuropha@njmu.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41401-024-01259-y.

References

- 1.Samii A, Nutt JG, Ransom BR. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 2004;363:1783–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16305-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balestrino R, Schapira AHV. Parkinson disease. Eur J Neurol. 2020;27:27–42. doi: 10.1111/ene.14108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shulman JM, De Jager PL, Feany MB. Parkinson’s disease: genetics and pathogenesis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:193–222. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moustafa AA, Chakravarthy S, Phillips JR, Gupta A, Keri S, Polner B, et al. Motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease: a unified framework. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;68:727–40. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ko Y-F, Kuo P-H, Wang C-F, Chen Y-J, Chuang P-C, Li S-Z, et al. Quantification analysis of sleep based on smartwatch sensors for Parkinson’s disease. Biosensors. 2022;12:74. doi: 10.3390/bios12020074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schrag A, Horsfall L, Walters K, Noyce A, Petersen I. Prediagnostic presentations of Parkinson’s disease in primary care: a case-control study. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:57–64. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70287-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Day JO, Mullin S. The genetics of Parkinson’s disease and implications for clinical practice. Genes. 2021;12:1006. doi: 10.3390/genes12071006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barreto GE, Iarkov A, Moran VE. Beneficial effects of nicotine, cotinine and its metabolites as potential agents for Parkinson’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:340. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aryal B, Lee Y. Disease model organism for Parkinson disease: Drosophila melanogaster. BMB Rep. 2019;52:250–8. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2019.52.4.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cacabelos R. Parkinson’s disease: from pathogenesis to pharmacogenomics. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:551. doi: 10.3390/ijms18030551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sagar S, Kaur M, Minneman KP. Antiviral lead compounds from marine sponges. Mar Drugs. 2010;8:2619–38. doi: 10.3390/md8102619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang B, Zhang T, Xu J, Lu J, Qiu P, Wang T, et al. Marine sponge-associated Fungi as potential novel bioactive natural product sources for drug discovery: a review. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2020;20:1966–2010. doi: 10.2174/1389557520666200826123248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin Z, Phadke S, Lu Z, Beyhan S, Abdel Aziz MH, Reilly C, et al. Onydecalins, fungal polyketides with anti- Histoplasma and anti-TRP activity. J Nat Prod. 2018;81:2605–11. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.7b01067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah M, Sun C, Sun Z, Zhang G, Che Q, Gu Q, et al. Antibacterial polyketides from Antarctica sponge-derived fungus Penicillium sp. HDN151272. Mar Drugs. 2020;18:71. doi: 10.3390/md18020071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Z, Qiu P, Liu H, Li J, Shao C, Yan T, et al. Identification of anti-inflammatory polyketides from the coral-derived fungus Penicillium sclerotiorin: In vitro approaches and molecular-modeling. Bioorg Chem. 2019;88:102973. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.102973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Q, Su G, Yang Q, Wei Z, Wang J, Zheng L, et al. Round scad-derived octapeptide WCPFSRSF confers neuroprotection by regulating Akt/Nrf2/NFκB signaling. J Agric Food Chem. 2021;69:10606–16. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.1c04774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Catanesi M, Caioni G, Castelli V, Benedetti E, d’Angelo M, Cimini A. Benefits under the sea: the role of marine compounds in neurodegenerative disorders. Mar Drugs. 2021;19:24. doi: 10.3390/md19010024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silva J, Alves C, Pinteus S, Susano P, Simões M, Guedes M, et al. Disclosing the potential of eleganolone for Parkinson’s disease therapeutics: Neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory activities. Pharmacol Res. 2021;168:105589. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kolesnikova SA, Lyakhova EG, Kalinovsky AI, Popov RS, Yurchenko EA, Stonik VA. Oxysterols from a marine sponge inflatella sp. and their action in 6-hydroxydopamine-induced cell model of Parkinson’s disease. Mar Drugs. 2018;16:458. doi: 10.3390/md16110458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Letsiou S, Bakea A, Goff GL, Lopes P, Gardikis K, Weis M, et al. Marine fungus Aspergillus chevalieri TM2-S6 extract protects skin fibroblasts from oxidative stress. Mar Drugs. 2020;18:460. doi: 10.3390/md18090460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stern JH, Rutkowski JM, Scherer PE. Adiponectin, leptin, and fatty acids in the maintenance of metabolic homeostasis through adipose tissue crosstalk. Cell Metab. 2016;23:770–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu J, Huang X. Lipid metabolism at membrane contacts: dynamics and functions beyond lipid homeostasis. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:615856. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.615856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tong Y, Sun Y, Tian X, Zhou T, Wang H, Zhang T, et al. Phospholipid transfer protein (PLTP) deficiency accelerates memory dysfunction through altering amyloid precursor protein (APP) processing in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:5388–403. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galper J, Kim WS, Dzamko N. LRRK2 and lipid pathways: implications for Parkinson’s disease. Biomolecules. 2022;12:1597. doi: 10.3390/biom12111597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Phillips GR, Hancock SE, Brown SHJ, Jenner AM, Kreilaus F, Newell KA, et al. Cholesteryl ester levels are elevated in the caudate and putamen of Huntington’s disease patients. Sci Rep. 2020;10:20314. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-76973-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xie J, Duan L, Qian X, Huang X, Ding J, Hu G. K(ATP) channel openers protect mesencephalic neurons against MPP+-induced cytotoxicity via inhibition of ROS production. J Neurosci Res. 2010;88:428–37. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wei Y, Lu M, Mei M, Wang H, Han Z, Chen M, et al. Pyridoxine induces glutathione synthesis via PKM2-mediated Nrf2 transactivation and confers neuroprotection. Nat Commun. 2020;11:941. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-14788-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ye H, Robak LA, Yu M, Cykowski M, Shulman JM. Genetics and pathogenesis of Parkinson’s syndrome. Annu Rev Pathol. 2023;18:95–121. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathmechdis-031521-034145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nicholatos JW, Francisco AB, Bender CA, Yeh T, Lugay FJ, Salazar JE, et al. Nicotine promotes neuron survival and partially protects from Parkinson’s disease by suppressing SIRT6. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2018;6:120. doi: 10.1186/s40478-018-0625-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davis S, Meltzer PS. GEOquery: a bridge between the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and BioConductor. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1846–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lei Y, Xu X, Liu H, Chen L, Zhou H, Jiang J, et al. HBx induces hepatocellular carcinogenesis through ARRB1-mediated autophagy to drive the G1/S cycle. Autophagy. 2021;17:4423–41. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2021.1917948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma X, McKeen T, Zhang J, Ding W-X. Role and mechanisms of mitophagy in liver diseases. Cells. 2020;9:837. doi: 10.3390/cells9040837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feng Y, Ning X, Wang J, Wen Z, Cao F, You Q, et al. Mace-like plasmonic Au-Pd heterostructures boost near-infrared photoimmunotherapy. Adv Sci. 2023;10:e2204842. doi: 10.1002/advs.202204842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guo J-D, Zhao X, Li Y, Li G-R, Liu X-L. Damage to dopaminergic neurons by oxidative stress in Parkinson’s disease. Int J Mol Med. 2018;41:1817–25. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2018.3406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sewastianik T, Straubhaar JR, Zhao J-J, Samur MK, Adler K, Tanton HE, et al. miR-15a/16-1 deletion in activated B cells promotes plasma cell and mature B-cell neoplasms. Blood. 2021;137:1905–19. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020009088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Castillo-Quan JI, Steinbaugh MJ, Fernández-Cárdenas LP, Pohl NK, Wu Z, Zhu F, et al. An antisteatosis response regulated by oleic acid through lipid droplet-mediated ERAD enhancement. Sci Adv. 2023;9:eadc8917. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adc8917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bezawork-Geleta A, Dimou J, Watt MJ. Lipid droplets and ferroptosis as new players in brain cancer glioblastoma progression and therapeutic resistance. Front Oncol. 2022;12:1085034. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.1085034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Consortium TM. Single-cell transcriptomics of 20 mouse organs creates a Tabula Muris. Nature. 2018;562:367–72. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0590-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wong E, Cuervo AM. Autophagy gone awry in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:805–11. doi: 10.1038/nn.2575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raudenska M, Balvan J, Masarik M. Crosstalk between autophagy inhibitors and endosome-related secretory pathways: a challenge for autophagy-based treatment of solid cancers. Mol Cancer. 2021;20:140. doi: 10.1186/s12943-021-01423-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakamura S, Yoshimori T. New insights into autophagosome-lysosome fusion. J Cell Sci. 2017;130:1209–16. doi: 10.1242/jcs.196352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang X, Zhang X, Chu ESH, Chen X, Kang W, Wu F, et al. Defective lysosomal clearance of autophagosomes and its clinical implications in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. FASEB J. 2018;32:37–51. doi: 10.1096/fj.201601393R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tian X, Zhang G, Shao Y, Yang Z. Towards enhanced metabolomic data analysis of mass spectrometry image: multivariate curve resolution and machine learning. Anal Chim Acta. 2018;1037:211–9. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2018.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Castellanos DB, Martín-Jiménez CA, Rojas-Rodríguez F, Barreto GE, González J. Brain lipidomics as a rising field in neurodegenerative contexts: perspectives with machine learning approaches. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2021;61:100899. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2021.100899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fahy E, Subramaniam S, Brown HA, Glass CK, Merrill AH, Murphy RC, et al. A comprehensive classification system for lipids. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:839–61. doi: 10.1194/jlr.E400004-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Farooqui AA. Lipid mediators in the neural cell nucleus: their metabolism, signaling, and association with neurological disorders. Neuroscientist. 2009;15:392–407. doi: 10.1177/1073858409337035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shamim A, Mahmood T, Ahsan F, Kumar A, Bagga P. Lipids: an insight into the neurodegenerative disorders. Clin Nutr Exp. 2018;20:1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.yclnex.2018.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Farese RV, Walther TC. Lipid droplets finally get a little R-E-S-P-E-C-T. Cell. 2009;139:855–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu L, Zhang K, Sandoval H, Yamamoto S, Jaiswal M, Sanz E, et al. Glial lipid droplets and ROS induced by mitochondrial defects promote neurodegeneration. Cell. 2015;160:177–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marschallinger J, Iram T, Zardeneta M, Lee SE, Lehallier B, Haney MS, et al. Lipid-droplet-accumulating microglia represent a dysfunctional and proinflammatory state in the aging brain. Nat Neurosci. 2020;23:194–208. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0566-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guo Y, Walther TC, Rao M, Stuurman N, Goshima G, Terayama K, et al. Functional genomic screen reveals genes involved in lipid-droplet formation and utilization. Nature. 2008;453:657–61. doi: 10.1038/nature06928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tanaka S, Hikita H, Tatsumi T, Sakamori R, Nozaki Y, Sakane S, et al. Rubicon inhibits autophagy and accelerates hepatocyte apoptosis and lipid accumulation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. Hepatology. 2016;64:1994–2014. doi: 10.1002/hep.28820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nakamura S, Oba M, Suzuki M, Takahashi A, Yamamuro T, Fujiwara M, et al. Suppression of autophagic activity by Rubicon is a signature of aging. Nat Commun. 2019;10:847. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08729-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wong S-W, Sil P, Martinez J. Rubicon: LC3-associated phagocytosis and beyond. FEBS J. 2018;285:1379–88. doi: 10.1111/febs.14354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Parzych KR, Klionsky DJ. An overview of autophagy: morphology, mechanism, and regulation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20:460–73. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Singh R, Kaushik S, Wang Y, Xiang Y, Novak I, Komatsu M, et al. Autophagy regulates lipid metabolism. Nature. 2009;458:1131–5. doi: 10.1038/nature07976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bae EJ, Lee HJ, Jang YH, Michael S, Masliah E, Min DS, et al. Phospholipase D1 regulates autophagic flux and clearance of α-synuclein aggregates. Cell Death Differ. 2014;21:1132–41. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.