Abstract

People with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are at risk for chronic kidney disease (CKD) due to HIV and antiretroviral therapy (ART) nephrotoxicity. Immediate ART initiation reduces mortality and is now the standard of care, but the long-term impact of prolonged ART exposure on CKD is unknown. To evaluate this, the Strategic Timing of Antiretroviral Treatment (START) trial randomized 4,684 ART-naïve adults with CD4 cell count under 500 cells/mm3 to immediate versus deferred ART. We previously reported a small but statistically significantly greater decline in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) over a median of 2.1 years in participants randomized to deferred versus immediate ART. Here, we compare the incidence of CKD events and changes in eGFR and urine albumin/creatinine ratio (UACR) in participants randomized to immediate versus deferred ART during extended follow-up. Over a median of 9.3 years, eight participants experienced kidney failure or kidney-related death, three in the immediate and five in the deferred ART arms, respectively. Over a median of five years of more comprehensive follow-up, the annual rate of eGFR decline was 1.19 mL/min/1.73m2/year, with no significant difference between treatment arms (difference deferred – immediate arm 0.055; 95% confidence interval −0.106, 0.217 mL/min/1.73m2). Results were similar in models adjusted for baseline covariates associated with CKD, including UACR and APOL1 genotype. Similarly, there was no significant difference between treatment arms in incidence of confirmed UACR 30 mg/g or more (odds ratio 1.13; 95% confidence interval 0.85, 1.51). Thus, our findings provide the most definitive evidence to date in support of the longterm safety of early ART with respect to kidney health.

Keywords: albuminuria, APOL1, chronic kidney disease, glomerular filtration rate, nephrotoxicity

Lay Summary

People with HIV are at increased risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD) due to both HIV infection and antiretroviral therapy (ART). The impact of earlier initiation of ART on kidney health has not been well described. In the extended follow-up of participants in a randomized clinical trial, we observed no significant differences in CKD outcomes, glomerular filtration rate, or albuminuria with immediate versus deferred initiation of antiretroviral therapy. Our results suggest that current practice has a neutral effect on kidney health and that providers should focus on traditional risk factors to reduce the incidence of CKD in people with HIV.

People with HIV (PWH) are at increased risk of acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease (CKD). Factors contributing to the burden of CKD in PWH include traditional CKD risk factors, local and systemic effects of HIV infection, and potential nephrotoxicity of antiretroviral therapy (ART), in particular, regimens including tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) or many HIV protease inhibitors (PI).1 The current treatment paradigm for HIV includes immediate initiation of ART in all PWH, regardless of CD4 cell count or clinical presentation.2 This strategy is supported by the results of 2 randomized clinical trials, START (Strategic Timing of ART) and TEMPRANO (Early Antiretroviral Treatment and/ or Early Isoniazid Prophylaxis Against Tuberculosis in HIV-infected Adults [ANRS 12136 TEMPRANO]), which demonstrated significant reductions in serious AIDS and non-AIDS events with earlier initiation of ART.3,4 Despite clear benefits, this strategy increases cumulative lifetime ART exposure with the potential for increased treatment toxicity, including kidney injury. Because both HIV infection and ART nephrotoxicity contribute to CKD risk, the long-term implications of earlier ART initiation for kidney health are unknown.

We previously reported a small but significantly greater decline in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) over a median follow-up of 2.1 years in START participants randomized to deferred versus immediate ART in START.5 Although those results suggested short-term benefits of earlier ART, the eGFR trajectories appeared to converge with longer follow-up. In addition, data were not available for other important predictors of eGFR decline, including urine albumin:creatinine ratio (UACR) and apolipoprotein-L1 (APOL1) genotype, which is strongly associated with CKD risk in PWH of African descent.6–10 Here, we compare the changes in eGFR in START participants randomized to immediate versus deferred ART over 5.5 years of comprehensive follow-up and describe protocol-defined CKD events occurring over a total of 9.3 years of clinical event follow-up. In a subset of participants enrolled in a genomic substudy, we also evaluated changes in UACR by treatment assignment and the impact of APOL1 genotype on eGFR, UACR, and treatment effect.

METHODS

The design of START has been described.3 Briefly, ART-naïve adults with HIV and CD4 cell count >500 cells/mm3 were randomized to immediate initiation of ART (“immediate ART”) or to deferral of ART until evidence of disease progression as determined by the treating provider or a CD4 cell count <350 cells/mm3 (“deferred ART”). Entry criteria were broad to ensure generalizability; of relevance to the current analyses, individuals on dialysis were excluded, but there were no restrictions based on serum creatinine, creatinine clearance, or eGFR. Initial ART regimens were selected from a list of approved regimens with established efficacy against HIV infection. Clinical guidelines in the United States evolved during enrollment and data collection to recommend ART initiation in all PWH regardless of CD4 cell count. Because the updated guidelines were not evidence-based and clinical guidelines in other participating countries remained consistent with the trial design, the data and safety monitoring board did not recommend early termination or modification of the protocol. At a planned interim analysis, on crossing a prespecified monitoring boundary, data were unblinded by the data and safety monitoring board in May 2015 after a median follow-up of 2.8 years. Participants not yet on ART were encouraged to start ART because of overwhelming evidence of efficacy for preventing the primary composite outcome of a serious AIDS or nonAIDS event or death in the immediate ART arm.3 Trial follow-up continued through December 2021 for clinical outcomes and ART status, and comprehensive laboratory data and stored specimens were collected through December 2017.11

The protocol-defined composite kidney disease outcome included kidney failure, defined as receipt of dialysis for at least 3 months (or at least 1 month in a participant who died within 3 months of starting dialysis) or documented kidney transplant, or death attributed to kidney failure. For the current analyses, baseline was defined as the date of randomization, including laboratory results from specimens collected within 60 days before randomization. The eGFR analysis included randomized participants with available data for eGFR at baseline and at least 1 follow-up visit and who had UACR measured at baseline (Supplementary Figure S1). Analyses including APOL1 genotype included participants enrolled in the genomic substudy; because >98% of substudy participants were enrolled at the time of consent to the main trial, treatment comparisons are protected by randomization. The UACR analysis was further restricted to participants with at least 1 follow-up UACR.

Serum creatinine was measured in the enrolling site clinical laboratory at baseline, months 1, 4, and 8, and then annually through December 2017. eGFR was calculated using the 2021 CKD Epidemiology Collaboration creatinine-based equation12 and considered as both a continuous and a categorical variable (≥90, 60–90, <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2). Urine albumin and creatinine were measured centrally in banked urine specimens collected at baseline, months 24 and 48, and additionally at months 1, 8, and 12 for participants in the genomics substudy. Urine assays were performed at the University of Vermont Laboratory for Clinical Biochemistry Research using Cobas C311 and Cobas Integra 400 Plus platforms, respectively (Roche Diagnostics). UACR was considered as both a continuous and a categorical variable (UACR <30, 30–300, ≥300 mg/g). Genotyping was performed by an Affymetrix Axiom single-nucleotide polymorphism array as previously described.13 APOL1 genotype was categorized as high versus low risk (2 vs. 0/1 risk alleles). In sensitivity analyses, we considered a dominant or additive inheritance model with the count of risk alleles as an ordinal variable. Data-collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs (D:A:D) risk scores were used to estimate CKD (full model) and cardiovascular disease risk (simplified model with family history set to zero).14,15

The eGFR analysis compared the annual rate of change in eGFR from baseline (i.e., slopes) between treatment arms using mixed linear regression models with restricted maximum likelihood estimation. Study visit month and intercepts were included as random effects. We accounted for repeated measurements with a spatial power covariance structure. The primary model included treatment arm, baseline eGFR, follow-up time, and a treatment arm by time interaction term (model 1).

Supplemental models were further adjusted for baseline covariates that have been associated with eGFR decline or CKD outcomes, including UACR (model 2), and UACR, covariates in Table 1, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker use, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, and prerandomization plan to include the potentially nephrotoxic agents TDF or a PI, with or without a pharmacoenhancer and with the exception of darunavir,16 in the initial ARTregimen (model 3). Missing values for covariates were categorized as “unknown.” To explore potential mechanisms of any observed treatment differences, models were additionally adjusted for time-updated variables (CD4 cell count, HIV-RNA, and use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) and cumulative exposure TDF oron any PI excluding darunavir (model 4). Cumulative exposure was estimated by dividing follow-up time from randomization into 1-month periods and counting a given month as 1 month of exposure if the individual was on the ARV at the end of the month. Overall ARV exposure was the sum of months with any ARV exposure, censored at the earliest of last eGFR measurement or 60 months. Models included interaction terms for each covariate with time. We explored potential interactions with treatment assignment. In sensitivity analyses, we censored at initiation of medications known to inhibit tubular secretion of creatinine (HIV integrase strand inhibitors, rilpivirine, and cobicistat).17

Table 1 |.

Baseline characteristics by treatment arm, sample for eGFR analysis (n = 4284)

| Variable and level | Total (n = 4284), n (%) | Immediate ART (n = 2115), n (%) | Deferred ART (n = 2169), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age, yr | |||

| <30 | 1193 (27.8) | 578 (27.3) | 615 (28.4) |

| 30 to <45 | 2085 (48.7) | 1054 (49.8) | 1031 (47.5) |

| ≥45 | 1006 (23.5) | 483 (22.8) | 523 (24.1) |

| Sex at birth | |||

| Male | 3134 (73.2) | 1551 (73.3) | 1583 (73.0) |

| Female | 1150 (26.8) | 564 (26.7) | 586 (27.0) |

| Race and ethnicity | |||

| Black | 1304 (30.4) | 642 (30.4) | 662 (30.5) |

| Hispanic | 553 (12.9) | 277 (13.1) | 276 (12.7) |

| Asian | 373 (8.7) | 190 (9.0) | 183 (8.4) |

| White | 1914 (44.7) | 927 (43.8) | 987 (45.5) |

| Other | 140 (3.3) | 79 (3.7) | 61 (2.8) |

| Region of enrollment | |||

| High-income country | 2073 (48.4) | 1020 (48.2) | 1053 (48.5) |

| Low- and middle-income country | 2211 (51.6) | 1095 (51.8) | 1116 (51.5) |

| Mode of infection | |||

| IDU | 61 (1.4) | 35 (1.7) | 26 (1.2) |

| Same sex | 2348 (54.8) | 1174 (55.5) | 1174 (54.1) |

| Opposite sex | 1650 (38.5) | 798 (37.7) | 852 (39.3) |

| Other | 225 (5.3) | 108 (5.1) | 117 (5.4) |

| CD4, cells/mm3, median IQR | 650.5 (583.5–765) | 650.5 (585–764.5) | 650.5 (581.5–765) |

| Log10 HIV RNA, copies/ml, median IQR | 4.11 (3.50–4.64) | 4.12 (3.51–4.64) | 4.11 (3.48–4.63) |

| HIV RNA, copies/ml | |||

| 0–399 | 325 (7.6) | 149 (7.0) | 176 (8.1) |

| 400–9999 | 1583 (37.0) | 783 (37.0) | 800 (36.9) |

| ≥10,000 | 2376 (55.5) | 1183 (55.9) | 1193 (55.0) |

| Hepatitis B virus coinfection | |||

| No | 4043 (94.4) | 2006 (94.8) | 2037 (93.9) |

| Yes | 121 (2.8) | 60 (2.8) | 61 (2.8) |

| Unknown | 120 (2.8) | 49 (2.3) | 71 (3.3) |

| Hepatitis C virus coinfection | |||

| No | 3982 (93.0) | 1960 (92.7) | 2022 (93.2) |

| Yes | 204 (4.8) | 111 (5.2) | 93 (4.3) |

| Unknown | 98 (2.3) | 44 (2.1) | 54 (2.5) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | |||

| Underweight | 126 (2.9) | 62 (2.9) | 64 (3.0) |

| Normal weight | 2216 (51.7) | 1094 (51.7) | 1122 (51.7) |

| Overweight | 1231 (28.7) | 604 (28.6) | 627 (28.9) |

| Obese | 711 (16.6) | 355 (16.8) | 356 (16.4) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | |||

| Normal | 3797 (88.6) | 1883 (89.0) | 1914 (88.2) |

| ≥140 | 487 (11.4) | 232 (11.0) | 255 (11.8) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | |||

| Normal | 3829 (89.4) | 1906 (90.1) | 1923 (88.7) |

| ≥90 | 455 (10.6) | 209 (9.9) | 246 (11.3) |

| Hypertension | 835 (19.5) | 402 (19.0) | 433 (20.0) |

| Dyslipidemia | 353 (8.2) | 162 (7.7) | 191 (8.8) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 148 (3.5) | 71 (3.4) | 77 (3.6) |

| CVD | 26 (0.6) | 14 (0.7) | 12 (0.6) |

| Smoking status | |||

| Nonsmoker | 2335 (54.5) | 1154 (54.6) | 1181 (54.4) |

| Current smoker | 1383 (32.3) | 676 (32.0) | 707 (32.6) |

| Former smoker | 566 (13.2) | 285 (13.5) | 281 (13.0) |

| On ACE inhibitor or ARB | 227 (5.3) | 117 (5.5) | 110 (5.1) |

| On any NSAID | 209 (4.9) | 108 (5.1) | 101 (4.7) |

| D:A:D 5-year risk for CKD | |||

| Low (≤0) | 3404 (79.5) | 1679 (79.4) | 1725 (79.5) |

| Moderate (1–4) | 609 (14.2) | 314 (14.8) | 295 (13.6) |

| High (≥5) | 250 (5.8) | 114 (5.4) | 136 (6.3) |

| Unknown | 21 (0.5) | 8 (0.4) | 13 (0.6) |

| D:A:D 5-year risk for CVD | |||

| Low (<1%) | 2656 (62.0) | 1323 (62.6) | 1333 (61.5) |

| Medium (1 to <5%) | 1423 (33.2) | 692 (32.7) | 731 (33.7) |

| High (5 to <10%) | 118 (2.8) | 52 (2.5) | 66 (3.0) |

| Very high (≥10%) | 26 (0.6) | 15 (0.7) | 11 (0.5) |

| Missing/unknown | 61 (1.4) | 33 (1.6) | 28 (1.3) |

| Baseline eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | |||

| ≥90 | 3644 (85.1) | 1802 (85.2) | 1842 (84.9) |

| 60–90 | 619 (14.4) | 305 (14.4) | 314 (14.5) |

| <60 | 21 (0.5) | 8 (0.4) | 13 (0.6) |

| Baseline UACR category, mg/g | |||

| <30 | 3986 (93.0) | 1972 (93.2) | 2014 (92.9) |

| 30 to <300 | 263 (6.1) | 128 (6.1) | 135 (6.2) |

| ≥300 | 35 (0.8) | 15 (0.7) | 20 (0.9) |

| APOL1 risk alleles | |||

| 0 risk alleles | 2126 (49.6) | 1049 (49.6) | 1077 (49.7) |

| 1 risk allele | 230 (5.4) | 116 (5.5) | 114 (5.3) |

| 2 risk alleles | 43 (1.0) | 16 (0.8) | 27 (1.2) |

| Unknown (no genotype information) | 1885 (44.0) | 934 (44.2) | 951 (43.8) |

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; APOL1, apolipoprotein-L1; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ART, antiretroviral therapy; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CKD-EPI, Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration; CVD, cardiovascular disease; D:A:D, Data-collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; IDU, injecting drug use; IQR, interquartile range; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; UACR, urine albumin:creatinine ratio.

eGFR was calculated using the CKD-EPI 2021 creatinine-based equation. High-income countries included the United States, Europe, Israel, and Australia. Low- and middle-income countries included Latin America, Africa, and Asia. Hepatitis B virus coinfection was defined as surface antigen positive within 1 year of enrollment; hepatitis C virus coinfection was defined as having a positive antibody test; diabetes mellitus was defined by diagnosis, treatment, or 8-hour fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dl; hypertension was defined by antihypertensive medication use, systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg (average of 2 measures), or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg (average of 2 measures); dyslipidemia was defined by lipid-lowering therapy or LDL cholesterol ≥160 mg/dl; pre-existing CVD was defined as prior myocardial infarction, stroke, or coronary revascularization. The analysis dataset was sealed on September 16, 2020.

The UACR analysis compared the annual rate of change in UACR from baseline between treatment arms in mixed linear models with the variance component covariance structure. Because the UACR data were skewed, data were log-transformed before fitting the linear models and subsequently back-transformed for ease of interpretation. The strategy for model building was similar to that for the eGFR analysis. We also considered UACR as a categorical variable in logistic regression models.

Secondary outcomes were based on clinically relevant declines in eGFR (≥30% decrease from baseline, decline to <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 or to < 15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 in participants with baseline above these cutoffs) or changes in UACR (increase to >30 mg/g or to >300 mg/g in participants with baseline below these cutoffs). We considered both transient events and events confirmed on 2 consecutive measures. Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) were calculated to evaluate differences between the treatment arms. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

RESULTS

A total of 4684 participants were randomized between 2009 and 2013. At the time of unblinding in May 2015, a protocol-defined CKD event had occurred in 3 participants, 1 in the immediate and 2 in the deferred ART arm. At the end of 2021 (median follow-up of 9.3 years; interquartile range [IQR]: 8.5–10.4 years), 9 protocol-defined CKD events had occurred in 8 participants, 3 in the immediate and 5 in the deferred ART arm (Table 2). Six of the 8 affected participants had a baseline eGFR between 60 and 90 ml/min per 1.73 m2. One participant in the deferred ART arm had a baseline eGFR of 8 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and died from pre-existing kidney failure before starting dialysis or ART. None of the affected participants in the deferred ART arm received TDF before the event.

Table 2|.

Participants experiencing protocol-defined kidney events

| Treatment arm | Age at baseline, yr | Sex | Race | Baseline eGFR | Baseline UACR | Time to ART initiation | Time on TDF, mo | Time to event, mo | Kidney event | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| 1 | Immediate | 52 | Female | White | 68 | <30 | 14 d | 20 | 136 | Kidney failure |

| 2 | Immediate | 63 | Male | White | 75 | 58 | 20 d | 5 | 99 | Kidney failure |

| 3 | Immediate | 45 | Male | White | 69 | 5296 | 24 d | 18 | 42 92 |

Kidney failure Renal death |

| 4 | Deferred | 29 | Female | Black | 119 | <30 | 39 mo | 0 | 76 | Kidney failure |

| 5 | Deferred | 42 | Male | Asian | 8 | 1523 | No ART | 0 | 18 | Renal death |

| 6 | Deferred | 36 | Female | Black | 46 | 223 | 25 mo | 0 | 87 | Kidney failure |

| 7 | Deferred | 55 | Male | Black | 65 | 1132 | 25 mo | 0 | 33 | Kidney failure |

| 8 | Deferred | 49 | Male | Black | 67 | 1480 | 15 mo | 0 | 37 | Kidney failure |

APOL1, apolipoprotein-L1; ART, antiretroviral therapy; CKD-EPI, Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate in ml/min per 1.73 m2 based on the CKD-EPI 2021 equation; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; UACR, urine albumin:creatinine ratio in mg/g.

Time on TDF reflects the cumulative time prescribed TDF before the event. Only 1 participant (participant 4) was prescribed a protease inhibitor other than darunavir; APOL1 genotype was available for only 1 of the 4 participants who identified their race as black (participant 7, zero risk alleles). The clinical events dataset was sealed in July 2022.

The eGFR analysis included 4284 participants (91.5%, Table 1). The median age at study entry was 36 years, and 30.4% reported their race as Black. The median CD4 cell count was 651 cells/mm3. Pre-existing hypertension and diabetes mellitus were reported by 19.5% and 3.5% of participants, respectively. The median baseline eGFR was 111 ml/ min per 1.73 m2, with 14.4% of participants between 60 and 90 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and 0.5% <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. The baseline UACR was 30–300 mg/g in 6.1% and ≥300 mg/g in 0.8% of participants. Baseline characteristics were well balanced between the treatment arms.

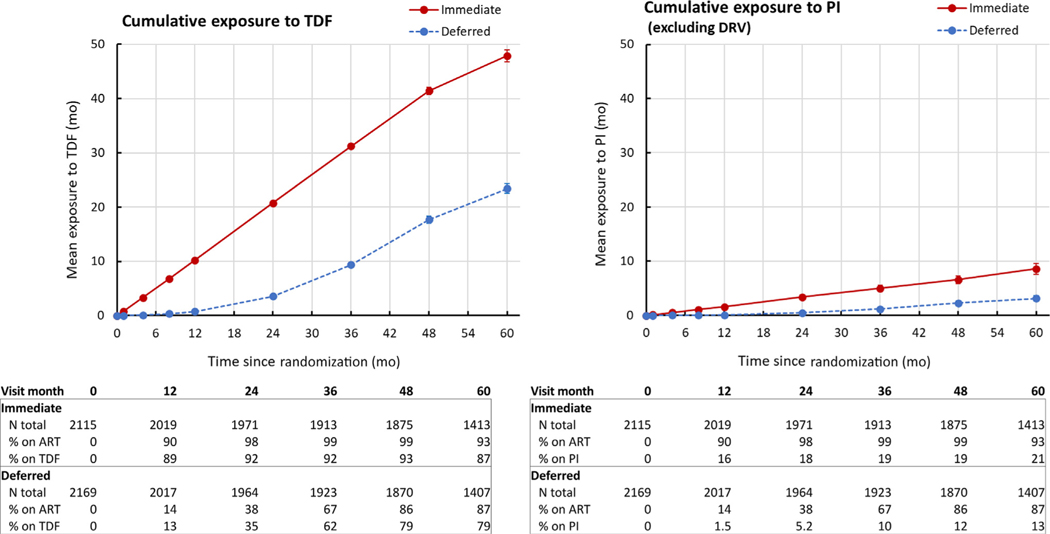

Patterns of ART use were consistent with the study design and with prescribing patterns during the enrollment period (Figure 1, Supplementary Table S1). The time to ART initiation was significantly shorter in participants randomized to immediate (median: 0.23 months; IQR: 0.07–0.53 months) versus deferred ART (median: 28.6 months; IQR: 17.6–40.2 months). Among participants in the analysis dataset, 99.0% of participants in the immediate ART arm and 49.2% of those in the deferred ART arm had initiated ART before unblinding. An additional 42.7% of participants in the deferred ART arm initiated ART between unblinding and the end of the analysis period. The initial regimen included TDF in 85.2% of participants, including 88.1% in the immediate and 82.3% in the deferred ARTarm; among those prescribed TDF, the median cumulative duration of TDF use was 59 and 29 months, respectively. Fewer than 0.2% of participants initiated ARTwith a regimen including tenofovir alafenamide. The initial regimen included a PI other than darunavir in 11.2% and 7.7% of participants in the immediate and deferred ARTarms, respectively. The initial regimen included at least 1 agent known to inhibit tubular creatinine secretion in 8.7% of participants in the immediate arm and 26.5% of those in the deferred arm.

Figure 1 |. Cumulative exposure to potentially nephrotoxic antiretroviral agents.

ART, antiretroviral therapy; DRV, darunavir; PI, protease inhibitor with or without a pharmacoenhancer; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate.

Change in eGFR

Over a median follow-up of 5 years (IQR: 4–6 years), the overall rate of eGFR decline was 1.19 ml/min per 1.73 m2 per year. The annual rate of eGFR decline from baseline was similar between the treatment arms (difference deferred minus immediate 0.055; 95% confidence interval [CI]: −0.106, 0.217 ml/min per 1.73 m2; Figure 2). Results were similar in separate sensitivity analyses censoring at the initiation of medications known to inhibit creatinine secretion and using the 2012 CKD-EPI equation to calculate eGFR.18

Figure 2 |. Change in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) from baseline by treatment arm.

ART, antiretroviral therapy.

Results were also similar in supplemental models adjusting for baseline covariates known to be associated with eGFR decline (Supplementary Table S2). In particular, point estimates for differences between treatment groups did not change substantially after adjustment for baseline UACR (model 2); the number of participants with clinically significant albuminuria at baseline (n = 298, 6.9%) was too small for meaningful subgroup analysis. With additional adjustment for time-updated variables (model 4), the annual rate of decline in eGFR was 0.26 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (95% CI: 0.06, 0.46 ml/min per 1.73 m2) faster in the deferred arm compared with the immediate arm. Cumulative time on TDF was the only significant contributor to differences between the base model and model 4 (Supplementary Table S3).

We identified statistically significant interactions between treatment assignment and age category and between treatment assignment and sex at birth in the fully adjusted supplementary models. In participants aged 45 years or older, the annual rate of eGFR decline was 0.62 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (95% CI: 0.21, 1.04 ml/min per 1.73 m2) faster in the deferred arm versus the immediate arm. In men, the annual rate of eGFR decline was 0.39 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (95% CI: 0.16, 0.63 ml/min per 1.73 m2) faster in the deferred versus the immediate arm.

Secondary eGFR outcomes

Overall, 9.8% of participants experienced a decline in eGFR of 30% or more from baseline, including all 8 participants who experienced a protocol-defined kidney event, with no significant difference between the treatment arms (IRR for deferred vs. immediate arms 1.15; 95% CI: 0.95, 1.38). Confirmed eGFR decline of 30% or more from baseline occurred in 1.9% of participants, with no difference between the groups (IRR: 1.15; 95% CI: 0.76, 1.75). Participants who experienced a confirmed event were more likely to have baseline UACR >30 mg/g and more likely to have a high-risk D:A:D CKD risk score. Incident eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 occurred in 174 participants (3.8%), with no significant difference between treatment groups (IRR: 0.92; 95% CI: 0.68, 1.24). An eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 was confirmed in 33 participants (0.7%) overall and was associated with baseline UACR and D:A:D 5-year CKD risk score.

Genomic substudy

Among 2399 participants in the genomic substudy, 43 (1.8%) had 2 APOL1 risk alleles (high-risk genotype) and 230 (9.6%) had a single risk allele. Among participants who self-identified as Black, 8% had 2 risk alleles and 38% had a single risk allele; among African American participants, the prevalence of the high-risk genotype was slightly higher (10.7%; 23 of 216). Participants with 2 risk alleles were more likely to have baseline eGFR <90 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (27.9% vs. 14.9% in those with 0–1 risk alleles) and baseline UACR >30 mg/g (23.3% vs. 6.5%). Under an alternative dominant model of inheritance, the prevalence of baseline eGFR <90 ml/min per 1.73 m2 was highest in participants with 2, intermediate in those with 1, and lowest in participants with zero risk alleles (27.9%, 20.4%, and 14.3%, respectively; P< 0.0001). We observed a similar pattern for baseline UACR ≥30 mg/g (23.3%, 12.1%, and 6.0%, respectively; P < 0.0001). Baseline characteristics were similar to the primary analysis population and were well balanced between the treatment arms (data not shown). There were no significant differences by treatment arm in the annual rate of change in eGFR from baseline (Supplementary Figure S2). Point estimates for the effect of treatment assignment did not change substantially after adjustment for APOL1 genotype. The number of participants with high-risk APOL1 genotype was too small to support subgroup analysis.

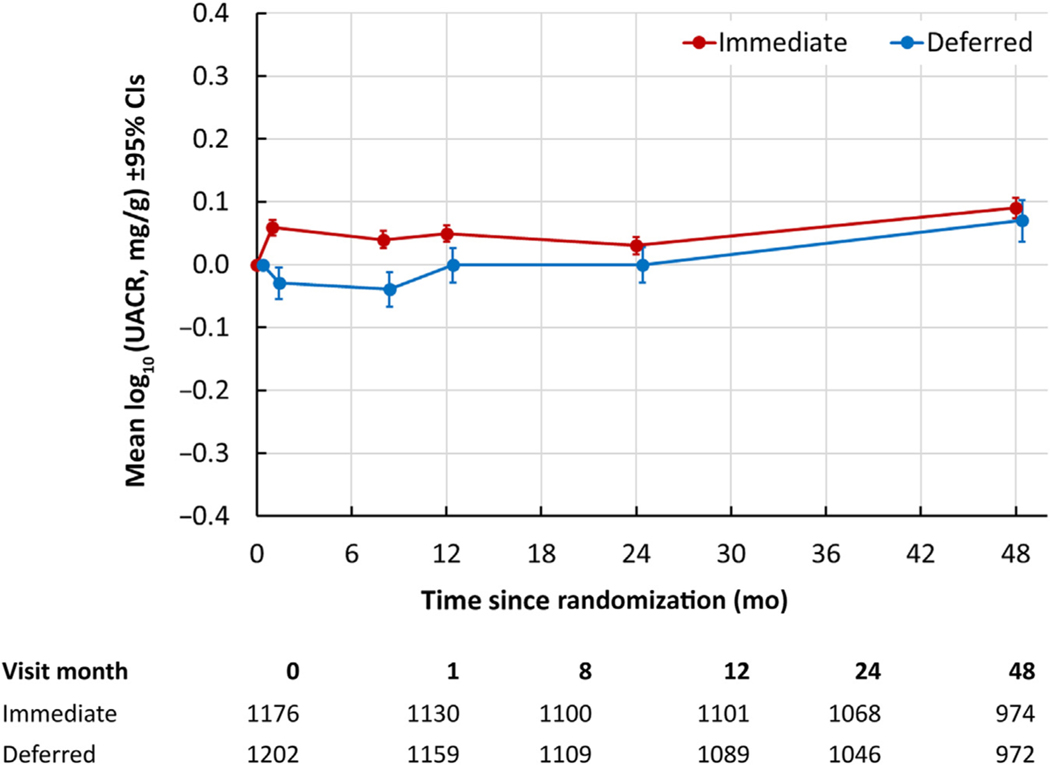

Change in UACR

The UACR analysis was nested in the genomic substudy, ensuring complete APOL1 genotype coverage. After removing 21 participants with no follow-up UACR measures, 2378 participants were included. Data were positively skewed due to a small number of very high values, with a mean baseline UACR of 17.8 mg/g (95% CI: 11.2, 24.5 mg/g) and a median of 2.96 mg/g (IQR: 1.83–6.33 mg/g). In a mixed linear model comparing the change in log10-transformed UACR from baseline (Figure 3), there was a very small but significantly greater increase of approximately 0.011 mg/g per year (95% CI: 0.001, 0.021 mg/g per year) in the deferred arm compared with the immediate arm. When UACR was considered as a categorical variable, there was no significant difference between the treatment arms in the number of participants with at least 2 postbaseline measures of UACR ≥30 mg/g (odds ratio: 1.13; 95% CI: 0.85, 1.51) or UACR ≥300 mg/g (odds ratio: 1.41; 95% CI: 0.56, 3.52).

Figure 3 |. Change in log10-transformed UACR from baseline by treatment arm.

CI, confidence interval; UACR, urine albumin:creatinine ratio.

DISCUSSION

In long-term follow-up of ART-naïve PWH with high baseline CD4 cell counts, serious CKD events were rare and did not differ significantly between participants randomized to immediate versus deferred ART. There was a modest decline in eGFR from baseline in both treatment arms that slightly exceeded the expected age-related physiologic decline, but randomization to immediate versus deferred ART did not significantly impact the annual change in eGFR over a median of 5 years of follow-up. The majority of participants in the deferred arm had initiated ART by the end of 2015, which may have attenuated the treatment differences we observed earlier in follow-up.5 Similar to the effect on eGFR, randomization to immediate versus deferred ART did not have a clinically significant impact on changes in albuminuria. Together, these findings provide the most definitive evidence available to date supporting the safety of early ART initiation with respect to kidney health.

Findings were similar in models adjusted for baseline covariates that are predictive of kidney disease outcomes, including APOL1 genotype. With additional adjustment for time-updated variables, we observed a small but statistically significant difference in eGFR slopes favoring immediate ART. Differences between the adjusted models were largely driven by cumulative exposure to TDF, suggesting that TDF nephrotoxicity may have offset some of the benefits of immediate ART for HIV-related kidney disease. These results should be interpreted with caution as they are no longer protected by randomization.

Among participants enrolled in the genomic substudy, results were similar after adjustment for high-risk APOL1 genotype, a strong predictor of CKD and in particular HIV-associated nephropathy.6–10 The number of participants with high-risk APOL1 genotype (2 risk alleles) was too small for formal subgroup analysis. Notably, participants with a single APOL1 risk allele had lower eGFR and more albuminuria at baseline compared with those with none, consistent with the hypothesis that a single risk allele may promote CKD in the setting of a strong “second hit” such as HIV.7

Strengths of this analysis include the randomized design and standardized long-term follow-up, as well as broad eligibility criteria. Adjusted analyses benefited from the availability of clinical and laboratory data on key covariates that are strongly associated with CKD outcomes, including UACR, APOL1 genotype, and use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Important limitations are related to the estimation of GFR from serum creatinine. Medications known to interfere with tubular secretion of creatinine were included in <9% and 27% of initial ART regimens in the immediate and deferred ART arms, respectively, and results were similar in sensitivity analyses censored at initiation of these agents. Serum creatinine was not measured centrally and was not standardized across laboratories; nonetheless, within-participant changes in eGFR were based on repeated measures in the same site-based clinical laboratory, and the large sample size should minimize the impact of measurement errors. Other inherent limitations of GFR estimates would not be expected to substantially impact the change in eGFR within an individual. We used the updated 2021 CKD-EPI equation, which was derived and validated without a coefficient for race but has not been rigorously evaluated in PWH. Results were similar using the 2012 CKD-EPI equation,18 which has been previously validated in PWH.19 Despite broad eligibility criteria, pre-existing CKD and traditional risk factors were rare in START, making it difficult to directly compare the incidence of advanced CKD with earlier trials in PWH. Adjusted analyses only considered time-updated use of TDF and PI (except for darunavir) because these agents have been linked to CKD risk, and did not consider the potential effects of other specific antiretroviral agents; of note, the most commonly used agents after TDF were emtricitabine and efavirenz, most commonly in a fixed-dose combination pill with TDF, and ritonavir, which was used exclusively with a PI. Finally, the high frequency and long duration of TDF exposure, although consistent with practice patterns at the time of enrollment, may have resulted in an underestimate of the benefit of early ART initiation with respect to kidney health. One could hypothesize that the faster decline in eGFR observed with deferred ART early in follow-up reflects ongoing subclinical HIV-related kidney damage in the deferred arm, while ART-related kidney injury would be expected to occur after more prolonged cumulative exposure. Although the current study design does not allow us to test this hypothesis, it is reassuring that the eGFR slopes appear similar after 5 years of median follow-up.

Overall, these results support the safety of earlier ART initiation with respect to kidney health and dispel concerns that the kidney benefits of virologic suppression and immune reconstitution might be outweighed by prolonged exposure to potentially nephrotoxic ART. Particularly with a shift toward ART regimens with less potential for kidney injury where resources allow, nephrologists and HIV and primary care providers should focus on modifying traditional CKD risk factors to address the increased risk of CKD and CKD progression in PWH.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure S1. Participant selection.

Supplementary Figure S2. Mean change in eGFR by treatment arm (genomics substudy).

Supplementary Table S1. Timing and duration of ART use by treatment arm.

Supplementary Table S2. Change in eGFR from baseline by treatment arm.

Supplementary Table S3. Contribution of individual time-updated variables to differences in the annual rate of change in eGFR from baseline by treatment arm.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the START Study participants for their longstanding contribution. The complete list of members of the START study group can be found in the Appendix of Lundgren et al.11

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (UM1 AI 068641, UM1-AI120197, and U01 AI136780); the Department of Bioethics at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center; the National Cancer Institute; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the National Institute of Mental Health; the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Disorders. Financial support for START was also provided by the French Agence Nationale de Recherches sur le Sida et les Hépatites Virales (ANRS); the German Ministry of Education and Research; the European AIDS Treatment Network (NEAT); the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council; and the UK Medical Research Council and National Institute for Health Research. Six pharmaceutical companies (AbbVie, Inc., Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline/ViiV Healthcare, Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, and Merck Sharp and Dohme Corp.) donated antiretroviral drugs to START. The authors were also supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01 DK112258 to CMW).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

AM has received honoraria, travel support, lecture, and consultancy fees unrelated to the present work from ViiV, Gilead Sciences, and Eiland and Bonnin, LLC. GT has received honoraria unrelated to the present study and paid to her institute from Gilead Sciences and grants from EU and National funds, Gilead Sciences, and University College London, all unrelated to the current study and paid to her institution. All the other authors declared no competing interests.

DATA STATEMENT

Primary data from the START trial are available on clinicaltrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT00867048). Additional deidentified data and supporting documentation used in the current analysis, including the trial protocol, statistical analysis plan, informed consent documents, and data dictionary, will be made available to researchers after approval of a proposal for use of the data. Proposals for data use should be submitted by means of the research proposal form on the INSIGHT website (www.insight-trials.org).

REFERENCES

- 1.Swanepoel CR, Atta MG, D’Agati VD, et al. Kidney disease in the setting of HIV infection: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int. 2018;93:545–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents with HIV. Accessed May 13, 2024. https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinicalguidelines-adult-and-adolescent-arv/initiation-antiretroviral-therapy?

- 3.Lundgren JD, Babiker AG, Gordin F, et al. Initiation of antiretroviral therapy in early asymptomatic HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:795–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Danel C, Moh R, Gabillard D, et al. A trial of early antiretrovirals and isoniazid preventive therapy in Africa. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:808–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Achhra AC, Mocroft A, Ross M, et al. Impact of early versus deferred antiretroviral therapy on estimated glomerular filtration rate in HIVpositive individuals in the START trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2017;50: 453–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papeta N, Kiryluk K, Patel A, et al. APOL1 variants increase risk for FSGS and HIVAN but not IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:1991–1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Genovese G, Friedman DJ, Ross MD, et al. Association of trypanolytic ApoL1 variants with kidney disease in African Americans. Science. 2010;329:841–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tzur S, Rosset S, Shemer R, et al. Missense mutations in the APOL1 gene are highly associated with end stage kidney disease risk previously attributed to the MYH9 gene. Hum Genet. 2010;128:345–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kasembeli AN, Duarte R, Ramsay M, et al. APOL1 risk variants are strongly associated with HIV-associated nephropathy in Black South Africans. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:2882–2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kopp JB, Nelson GW, Sampath K, et al. APOL1 genetic variants in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and HIV-associated nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:2129–2137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lundgren JD, Babiker AG, Sharma S, et al. Long-term benefits from early antiretroviral therapy initiation in HIV infection. NEJM Evid. 2023;2. 10.1056/evidoa2200302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inker LA, Eneanya ND, Coresh J, et al. New creatinine- and cystatin Cbased equations to estimate GFR without race. N Engl J Med. 2021;385: 1737–1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sherman BT, Hu X, Singh K, et al. Genome-wide association study of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, D-dimer, and interleukin-6 levels in multiethnic HIVþ cohorts. AIDS. 2021;35:193–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mocroft A, Lundgren JD, Ross M, et al. Development and validation of a risk score for chronic kidney disease in HIV infection using prospective cohort data from the D:A:D study. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friis-Møller N, Ryom L, Smith C, et al. An updated prediction model of the global risk of cardiovascular disease in HIV-positive persons: the Datacollection on Adverse Effects of Anti-HIV Drugs (D:A:D) study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2016;23:214–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ryom L, Dilling Lundgren J, Reiss P, et al. Use of contemporary protease inhibitors and risk of incident chronic kidney disease in persons with human immunodeficiency virus: the Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs (D:A:D) study. J Infect Dis. 2019;220:1629–1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lepist EI, Zhang X, Hao J, et al. Contribution of the organic anion transporter OAT2 to the renal active tubular secretion of creatinine and mechanism for serum creatinine elevations caused by cobicistat. Kidney Int. 2014;86:350–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inker LA, Schmid CH, Tighiouart H, et al. Estimating glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine and cystatin C. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:20–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inker LA, Wyatt C, Creamer R, et al. Performance of creatinine and cystatin C GFR estimating equations in an HIV-positive population on antiretrovirals. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61:302–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure S1. Participant selection.

Supplementary Figure S2. Mean change in eGFR by treatment arm (genomics substudy).

Supplementary Table S1. Timing and duration of ART use by treatment arm.

Supplementary Table S2. Change in eGFR from baseline by treatment arm.

Supplementary Table S3. Contribution of individual time-updated variables to differences in the annual rate of change in eGFR from baseline by treatment arm.

Data Availability Statement

Primary data from the START trial are available on clinicaltrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT00867048). Additional deidentified data and supporting documentation used in the current analysis, including the trial protocol, statistical analysis plan, informed consent documents, and data dictionary, will be made available to researchers after approval of a proposal for use of the data. Proposals for data use should be submitted by means of the research proposal form on the INSIGHT website (www.insight-trials.org).